Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

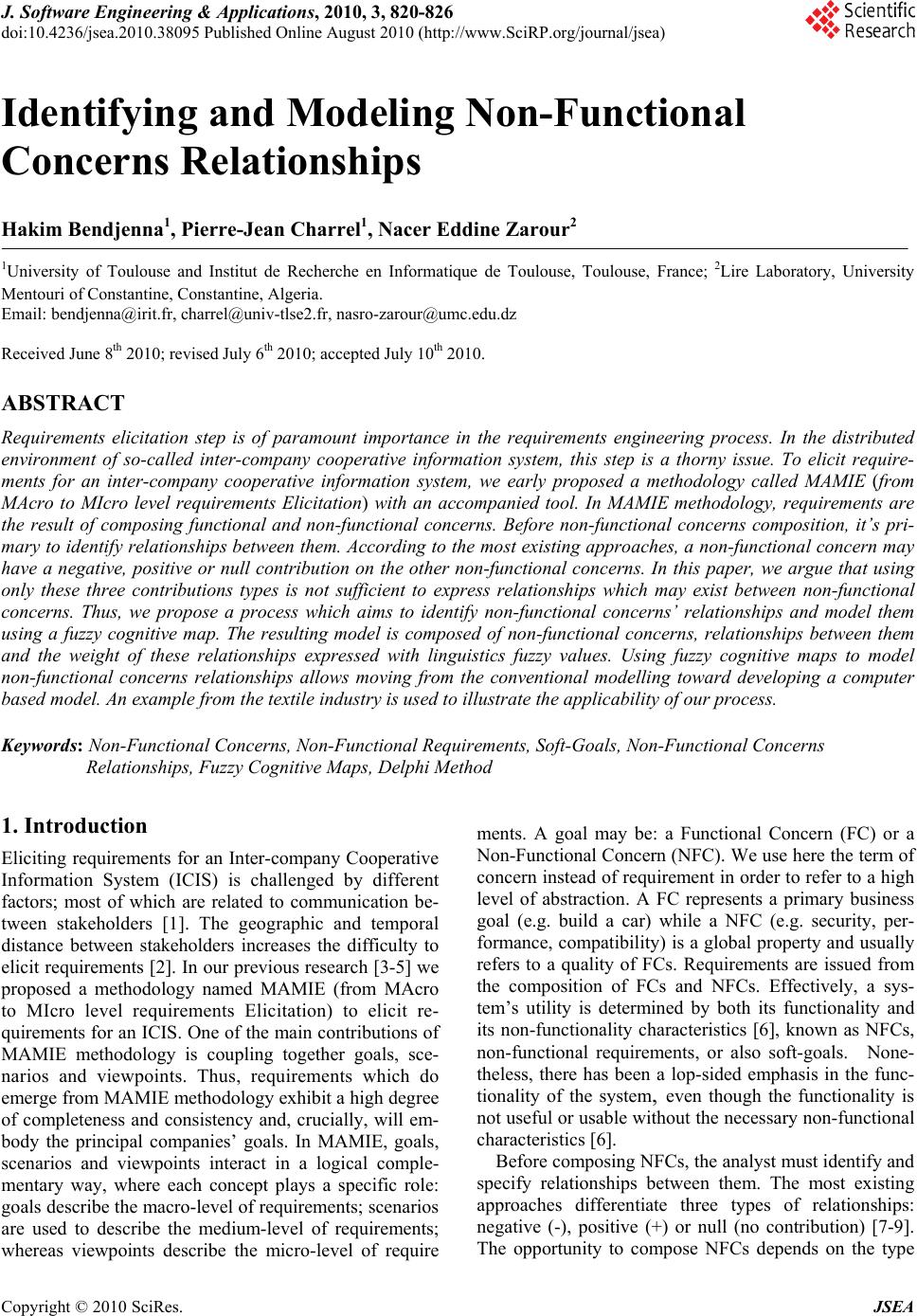

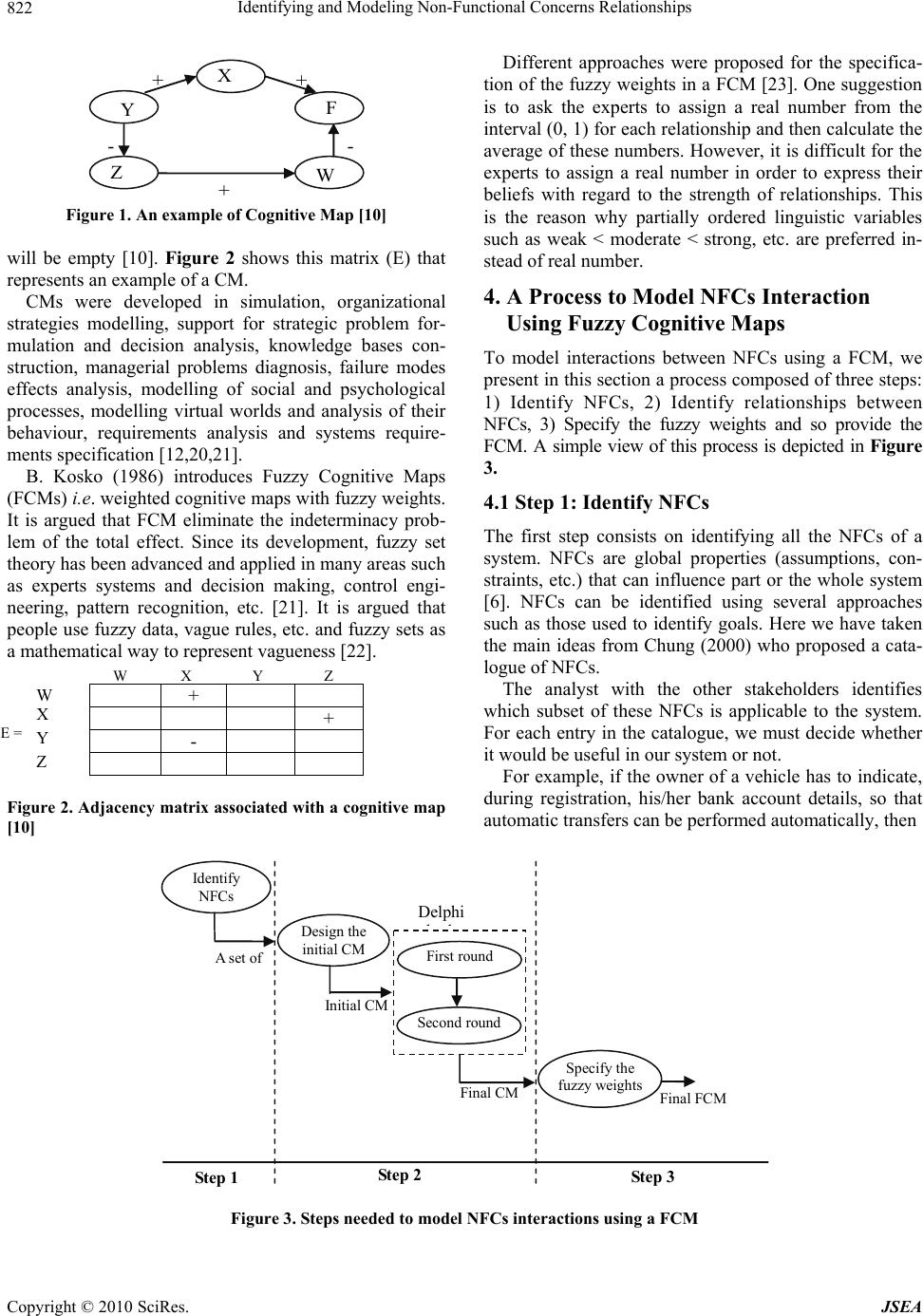

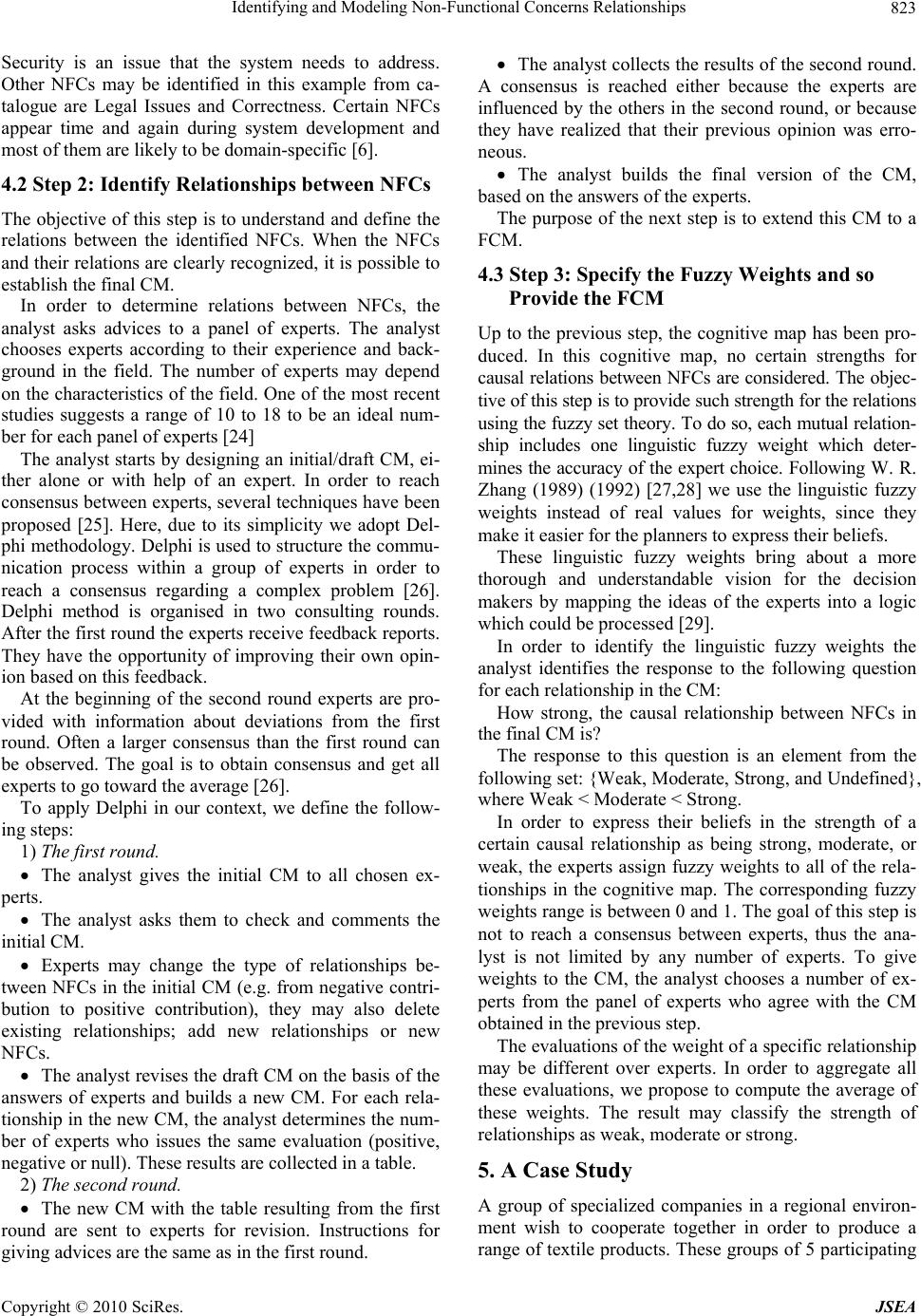

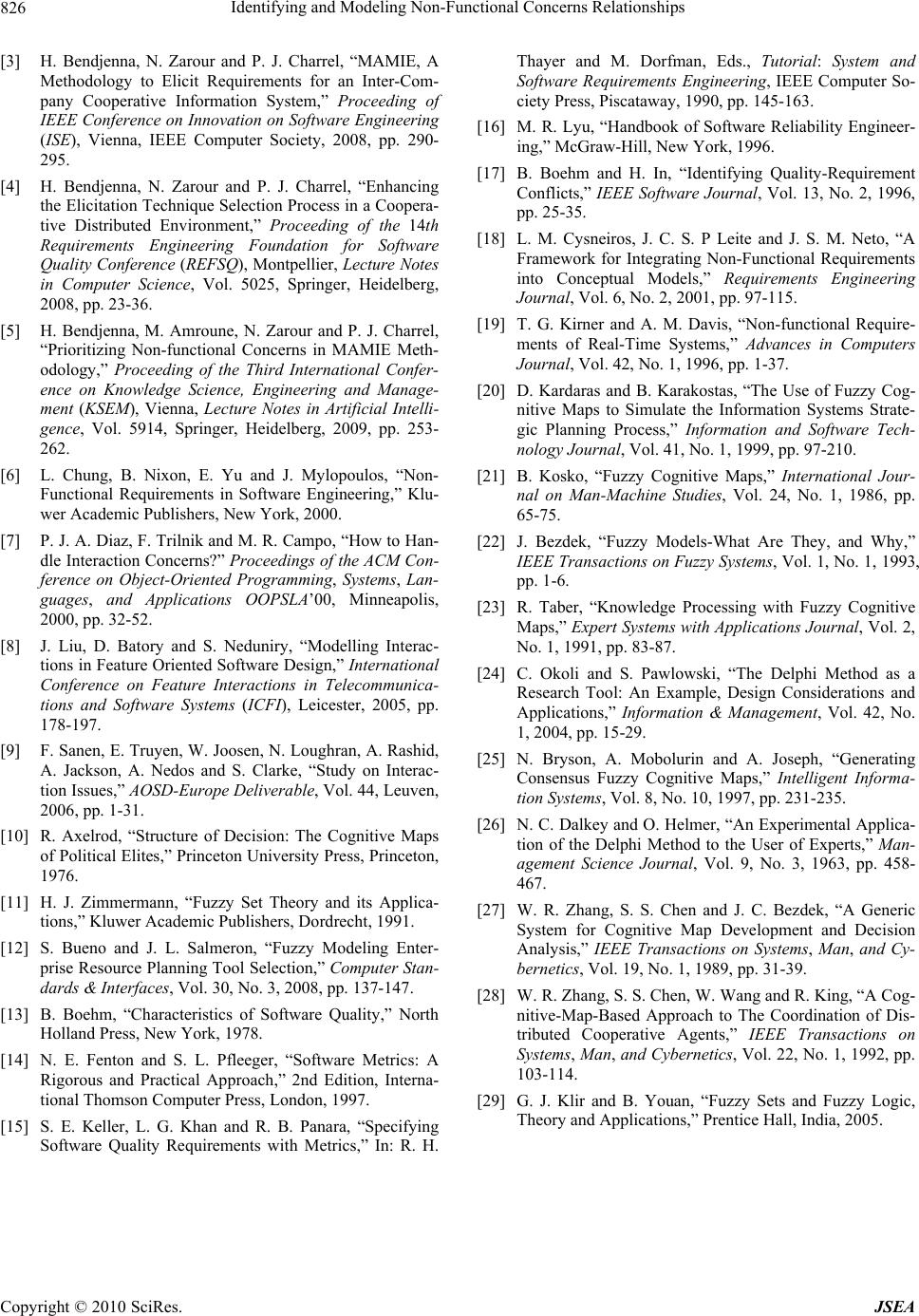

J. Software Engineering & Applications, 2010, 3, 820-826 doi:10.4236/jsea.2010.38095 Published Online August 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jsea) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA Identifying and Modeling Non-Functional Concerns Relationships Hakim Bendjenna1, Pierre-Jean Charrel1, Nacer Eddine Zarour2 1University of Toulouse and Institut de Recherche en Informatique de Toulouse, Toulouse, France; 2Lire Laboratory, University Mentouri of Constantine, Constantine, Algeria. Email: bendjenna@irit.fr, charrel@univ-tlse2.fr, nasro-zarour@umc.edu.dz Received June 8th 2010; revised July 6th 2010; accepted July 10th 2010. ABSTRACT Requirements elicitation step is of paramount importance in the requirements engineering process. In the distributed environment of so-called inter-company cooperative information system, this step is a thorny issue. To elicit require- ments for an inter-company cooperative information system, we early proposed a methodology called MAMIE (from MAcro to MIcro level requirements Elicitation) with an accompanied tool. In MAMIE methodology, requirements are the result of composing functional and non-functional concerns. Before non-functional concerns composition, it’s pri- mary to identify relationships between them. According to the most existing approaches, a non-functional concern may have a negative, positive or null contribution on the other non-functional concerns. In this paper, we argue that using only these three contributions types is not sufficient to express relationships which may exist between non-functional concerns. Thus, we propose a process which aims to identify non-functional concerns’ relationships and model them using a fuzzy cognitive map. The resulting model is composed of non-functional concerns, relationships between them and the weight of these relationships expressed with linguistics fuzzy values. Using fuzzy cognitive maps to model non-functional concerns relationships allows moving from the conventional modelling toward developing a computer based model. An example from the textile industry is used to illustrate the applicability of our process. Keywords: Non-Functional Concerns, Non-Functional Requirements, Soft-Goals, Non-Functional Concerns Relationships, Fuzzy Cognitive Maps, Delphi Method 1. Introduction Eliciting requirements for an Inter-company Cooperative Information System (ICIS) is challenged by different factors; most of which are related to communication be- tween stakeholders [1]. The geographic and temporal distance between stakeholders increases the difficulty to elicit requirements [2]. In our previous research [3-5] we proposed a methodology named MAMIE (from MAcro to MIcro level requirements Elicitation) to elicit re- quirements for an ICIS. One of the main contributions of MAMIE methodology is coupling together goals, sce- narios and viewpoints. Thus, requirements which do emerge from MAMIE methodology exhibit a high degree of completeness and consistency and, crucially, will em- body the principal companies’ goals. In MAMIE, goals, scenarios and viewpoints interact in a logical comple- mentary way, where each concept plays a specific role: goals describe the macro-level of requirements; scenarios are used to describe the medium-level of requirements; whereas viewpoints describe the micro-level of require ments. A goal may be: a Functional Concern (FC) or a Non-Functional Concern (NFC). We use here the term of concern instead of requirement in order to refer to a high level of abstraction. A FC represents a primary business goal (e.g. build a car) while a NFC (e.g. security, per- formance, compatibility) is a global property and usually refers to a quality of FCs. Requirements are issued from the composition of FCs and NFCs. Effectively, a sys- tem’s utility is determined by both its functionality and its non-functionality characteristics [6], known as NFCs, non-functional requirements, or also soft-goals. None- theless, there has been a lop-sided emphasis in the func- tionality of the system, even though the functionality is not useful or usable without the necessary non-functional characteristics [6]. Before composing NFCs, the analyst must identify and specify relationships between them. The most existing approaches differentiate three types of relationships: negative (-), positive (+) or null (no contribution) [7-9]. The opportunity to compose NFCs depends on the type  Identifying and Modeling Non-Functional Concerns Relationships Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 821 of these relationships. For example, when two NFCs which contribute negatively to each other are composed, then one NFC will influence negatively the correct working of the other. Based on relationships types among NFCs, the analyst may decide if the composition is or not. The interactions between NFCs need to prioritize NFCs and then to define the degree of contribution of a NFC to another NFC: two or more NFCs may not con- tribute with the same degree to a specific NFC. For ex- ample, Functionality and Aesthetics are two NFCs that contribute positively to the NFC Service quality. How- ever, Functionality ensures Service quality more accu- rately than Aesthetics. Thus, defining explicit knowledge about NFCs interactions may help to improve the com- position process and then the requirements elicitation process. This paper uses fuzzy cognitive maps [10,11] to model interactions between NFCs. This formalism is known to be used in ill-structured problems solving. It allows observing the significance of each factor and its influence on other factors and the final decision [12]. In our context, a fuzzy cognitive map is composed of (1) NFCs, (2) the type of relationships between them, and (3) the weights of these relationships which indicate their importance. The rest of this paper is structured as follows. In Sec- tion 2 we discuss related works. In Section 3 we give the main features of fuzzy cognitive maps. In Section 4 we present the three steps of a process to build a FCM which identify and model NFCs and their relationships using a fuzzy cognitive map. Section 5 shows the application of this process to a case study. Finally, concluding remarks are provided as well as future research issues. 2. Related Works Most of the early work on NFCs focused on measuring how much a software system is in accordance with the set of NFCs that it should satisfy, using some form of quantitative analysis [13-16], offering predefined metrics to assess the degree to which a given software object meets a particular NFC. Recently, a number of works proposed to use ap- proaches which explicitly deal with NFCs before metrics are applicable [11,17-19]. These works propose the use of techniques to justify design decisions on the inclusion or exclusion of requirements which will impact on the software design. Unlike the metrics approaches, these latter approaches are concerned about making NFCs a relevant and important part of the software development process. Boehm and In (1996) propose a knowledge base where NFCs are prioritized through stakeholders’ perspectives, dealing with NFCs at a high level of abstraction. Kirner (1996) describe properties for six NFCs from the real-time system domain: performance, reliability, safety, security, maintainability and usability. This work pro- vides heuristics on how to apply the identified properties to meet the NFCs and later measure these NFCs. A significant advance was introduced when NFCs where treated as competing goals that are extensively refined and traded off among each other in an attempt to arrive at acceptable solutions. The non-functional re- quirements Framework is one of the few works to deal with non-functional requirements starting from the early stages of software development through a broader per- spective. The non-functional requirements Framework [6] views non-functional requirements as goals that might conflict among each other and must be represented as soft-goals to be satisficed. The soft-goal concept was introduced to cope with the abstract and informal nature of non-functional requirements. 4 types of contribution have been proposed to describe relationships among non-functional requirements: make (++), help (+), hurt (-), break (--). However, as important as getting a well-formed and as-complete-as-possible set of contribu- tion types, we need to understand how to identify and model these relationships. None of the above work tack- les this problem. 3. Fuzzy Cognitive Maps: A Brief Description In this section, we describe some features of fuzzy cogni- tive maps. Cognitive Maps (CMs) were proposed by R. Axelrod (1976) in order to solve ill-structured problems. A CM is a signed digraph designed to capture the causal assertions of a person with respect to a certain domain and then uses them in order to analyze the effects of al- ternative, e.g. policies, business decisions, etc. upon cer- tain goals. A cognitive map is based on two notions: The concept which is represented by a variable. The causal belief which defines a relationship among variables. These relationships link variables to each other and they can be either positive or negative. Variables that cause a change are called cause vari- ables while those that undergo the effect of the change in the cause variable are called effect variables. If the rela- tionship is positive, an increase or decrease in a cause variable causes the effect variable(s) to change in the same direction. If the relationship is negative, then the change which the effect variable undergoes is in the op- posite direction. Figure 1 is a graphical representation of a cognitive map, where variables (X, Y, Z, F, W) are represented as nodes, and causal relationships as directed arrows between variables, thus constructing a signed digraph. Another way of representing a cognitive map is possi- ble through an adjacency matrix where one can clearly observe the sign of the relationship, while keeping in mind that in case of there being an absence of relation- ship between these two factors, the corresponding entry  Identifying and Modeling Non-Functional Concerns Relationships Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 822 X Y F W Z + -- + + Figure 1. An example of Cognitive Map [10] will be empty [10]. Figure 2 shows this matrix (E) that represents an example of a CM. CMs were developed in simulation, organizational strategies modelling, support for strategic problem for- mulation and decision analysis, knowledge bases con- struction, managerial problems diagnosis, failure modes effects analysis, modelling of social and psychological processes, modelling virtual worlds and analysis of their behaviour, requirements analysis and systems require- ments specification [12,20,21]. B. Kosko (1986) introduces Fuzzy Cognitive Maps (FCMs) i.e. weighted cognitive maps with fuzzy weights. It is argued that FCM eliminate the indeterminacy prob- lem of the total effect. Since its development, fuzzy set theory has been advanced and applied in many areas such as experts systems and decision making, control engi- neering, pattern recognition, etc. [21]. It is argued that people use fuzzy data, vague rules, etc. and fuzzy sets as a mathematical way to represent vagueness [22]. + + - Figure 2. Adjacency matrix associated with a cognitive map [10] Different approaches were proposed for the specifica- tion of the fuzzy weights in a FCM [23]. One suggestion is to ask the experts to assign a real number from the interval (0, 1) for each relationship and then calculate the average of these numbers. However, it is difficult for the experts to assign a real number in order to express their beliefs with regard to the strength of relationships. This is the reason why partially ordered linguistic variables such as weak < moderate < strong, etc. are preferred in- stead of real number. 4. A Process to Model NFCs Interaction Using Fuzzy Cognitive Maps To model interactions between NFCs using a FCM, we present in this section a process composed of three steps: 1) Identify NFCs, 2) Identify relationships between NFCs, 3) Specify the fuzzy weights and so provide the FCM. A simple view of this process is depicted in Figure 3. 4.1 Step 1: Identify NFCs The first step consists on identifying all the NFCs of a system. NFCs are global properties (assumptions, con- straints, etc.) that can influence part or the whole system [6]. NFCs can be identified using several approaches such as those used to identify goals. Here we have taken the main ideas from Chung (2000) who proposed a cata- logue of NFCs. The analyst with the other stakeholders identifies which subset of these NFCs is applicable to the system. For each entry in the catalogue, we must decide whether it would be useful in our system or not. For example, if the owner of a vehicle has to indicate, during registration, his/her bank account details, so that automatic transfers can be performed automatically, then Step 3 Step 2 Step 1 First round Identify NFCs Design the initial CM Second round Final CM Initial CM Specify the fuzzy weightsFinal FCM Delphi hd A set of Figure 3. Steps needed to model NFCs interactions using a FCM E = W X Y Z W X Y Z  Identifying and Modeling Non-Functional Concerns Relationships Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 823 Security is an issue that the system needs to address. Other NFCs may be identified in this example from ca- talogue are Legal Issues and Correctness. Certain NFCs appear time and again during system development and most of them are likely to be domain-specific [6]. 4.2 Step 2: Identify Relationships between NFCs The objective of this step is to understand and define the relations between the identified NFCs. When the NFCs and their relations are clearly recognized, it is possible to establish the final CM. In order to determine relations between NFCs, the analyst asks advices to a panel of experts. The analyst chooses experts according to their experience and back- ground in the field. The number of experts may depend on the characteristics of the field. One of the most recent studies suggests a range of 10 to 18 to be an ideal num- ber for each panel of experts [24] The analyst starts by designing an initial/draft CM, ei- ther alone or with help of an expert. In order to reach consensus between experts, several techniques have been proposed [25]. Here, due to its simplicity we adopt Del- phi methodology. Delphi is used to structure the commu- nication process within a group of experts in order to reach a consensus regarding a complex problem [26]. Delphi method is organised in two consulting rounds. After the first round the experts receive feedback reports. They have the opportunity of improving their own opin- ion based on this feedback. At the beginning of the second round experts are pro- vided with information about deviations from the first round. Often a larger consensus than the first round can be observed. The goal is to obtain consensus and get all experts to go toward the average [26]. To apply Delphi in our context, we define the follow- ing steps: 1) The first round. The analyst gives the initial CM to all chosen ex- perts. The analyst asks them to check and comments the initial CM. Experts may change the type of relationships be- tween NFCs in the initial CM (e.g. from negative contri- bution to positive contribution), they may also delete existing relationships; add new relationships or new NFCs. The analyst revises the draft CM on the basis of the answers of experts and builds a new CM. For each rela- tionship in the new CM, the analyst determines the num- ber of experts who issues the same evaluation (positive, negative or null). These results are collected in a table. 2) The second round. The new CM with the table resulting from the first round are sent to experts for revision. Instructions for giving advices are the same as in the first round. The analyst collects the results of the second round. A consensus is reached either because the experts are influenced by the others in the second round, or because they have realized that their previous opinion was erro- neous. The analyst builds the final version of the CM, based on the answers of the experts. The purpose of the next step is to extend this CM to a FCM. 4.3 Step 3: Specify the Fuzzy Weights and so Provide the FCM Up to the previous step, the cognitive map has been pro- duced. In this cognitive map, no certain strengths for causal relations between NFCs are considered. The objec- tive of this step is to provide such strength for the relations using the fuzzy set theory. To do so, each mutual relation- ship includes one linguistic fuzzy weight which deter- mines the accuracy of the expert choice. Following W. R. Zhang (1989) (1992) [27,28] we use the linguistic fuzzy weights instead of real values for weights, since they make it easier for the planners to express their beliefs. These linguistic fuzzy weights bring about a more thorough and understandable vision for the decision makers by mapping the ideas of the experts into a logic which could be processed [29]. In order to identify the linguistic fuzzy weights the analyst identifies the response to the following question for each relationship in the CM: How strong, the causal relationship between NFCs in the final CM is? The response to this question is an element from the following set: {Weak, Moderate, Strong, and Undefined}, where Weak < Moderate < Strong. In order to express their beliefs in the strength of a certain causal relationship as being strong, moderate, or weak, the experts assign fuzzy weights to all of the rela- tionships in the cognitive map. The corresponding fuzzy weights range is between 0 and 1. The goal of this step is not to reach a consensus between experts, thus the ana- lyst is not limited by any number of experts. To give weights to the CM, the analyst chooses a number of ex- perts from the panel of experts who agree with the CM obtained in the previous step. The evaluations of the weight of a specific relationship may be different over experts. In order to aggregate all these evaluations, we propose to compute the average of these weights. The result may classify the strength of relationships as weak, moderate or strong. 5. A Case Study A group of specialized companies in a regional environ- ment wish to cooperate together in order to produce a range of textile products. These groups of 5 participating  Identifying and Modeling Non-Functional Concerns Relationships Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 824 companies with their locations are the following: The fiber producer company (Morocco). The knitting mills and weaver company (France). The dyer and finisher company (France). The designer company (Spain). And the manufacturer company (Italy). The analyst who is in France applies MAMIE method- ology to elicit requirements for the future system. In this paper, we present the result of applying the process pre- sented to identify and model relationships between NFCs. 5.1 Step 1: Identify NFCs The analyst with the other stakeholders has identified the following set of NFCs: Product quality (NFC1), Func- tionality (NFC2), Product cost (NFC3) and Competitive- ness (NFC4). 5.2 Step 2: Identify Relationships between NFCs The result of this step is a final CM. To obtain it, the analyst chooses 10 experts. S/he starts by building an initial CM with one expert. Figure 4 depicts the result of this sub-step. In order to obtain the final CM, the analyst applies Delphi method. Table 1 summarises the advices of the experts on the initial CM: for each relationship between NFCs, the table collects the number of experts who agree with its type (positive, negative or null). We may remark that: The experts reach a consensus for almost all the re- lationships, i.e. in most cases they have responded in the same way. Product aesthetics (NFC5) is a new NFC added by 6 experts. They estimate that it has a positive relation with Product quality NFC (NFC1) According to the consequences of the first round of Del- Functionality (NFC 2 ) Product Quality ( NFC 1 ) Product Cost (NFC 3 ) - + Competitiveness (NFC 4 ) + Figure 4. The initial CM Table 1. First round: distribution of the experts’ responses Relation- ships Positive relationship Negative Relationship No relationship NFC2-NFC1 10 0 0 NFC1-NFC4 9 1 0 NFC3-NFC4 3 6 1 NFC5-NFC1 6 0 4 phi methodology, the initial cognitive map needs some improvements and corrections. After applying these revisions, the second round starts up. The revised cognitive map with the frequency of re- sponses obtained at the end of the first round is sent to the experts. The analyst asks them to explore the rela- tions in the new cognitive map and insert their opinions. The results of the second round are collected in Table 2. We observe that the experts have made some compro- mises. Figure 5 depicts the final CM. 5.3 Specify the Fuzzy Weights and so Provide the FCM In order to determine the weights of the relations identi- fied in the previous step, the analyst asks the following question to the experts: How strong, do you believe, the causal relationship between NFCs in the final CM is? The experts express their beliefs in the strength of a certain causal relationship, by assigning a fuzzy weight ranging between 0 and 1 where, we consider that: 0 < Low < 0.25; 0.25 <= Moderate < 0.75; 0.75 <= Strong <= 1. Table 3 summarizes the results where Ei denotes the Table 2. Second round: distribution of the experts’ re- sponses Relationships Positive relationship Negative relationship No relationship NFC2-NFC1 10 0 0 NFC1-NFC4 9 1 0 NFC3-NFC4 1 8 1 NFC5-NFC1 10 0 0 Figure 5. The final CM Table 3. Experts’ evaluations for relationships fuzzy wei- ghts RelationshipsE1 E2 E3 E4 E5 E6 E7 NFC2-NFC10.80 0.850.90 1,00 0.80 0.950.90 NFC1-NFC40.85 0.900.80 0.90 1,00 0.920.87 NFC3-NFC40.30 0.280.40 0.45 0.50 0.400.35 NFC5-NFC10.40 0.350.45 0.50 0.48 0.550.60 + Product aesthetics (NFC5) + + - Competitiveness (NFC4) Product Cost (NFC3) Product Quality (NFC1) Functionality ( NFC2 )  Identifying and Modeling Non-Functional Concerns Relationships Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 825 i-th expert and i=1,..,7, i.e. 7 experts participate to this step. The weight of each relationship is the average of the experts’ evaluation for this relationship. The value re- turned by this function allows attributing a linguistic fuzzy weight. Table 4 shows the results. The final FCM is the labelled CM with its fuzzy lin- guistic weights depicted by Figure 6. Figure 7 depicts a screen-dump of MAMIE-Tool when NFCs are identified and specified with their rela- tionships. The managers and planners can use this FCM to in- crease the competitiveness and to improve the product quality by analyzing different choices; such as decreasing the product cost. Thus, using a FCM to model relation- ships between NFCs provides a way to identify how to reach goals Table 4. Linguistics weights of relationships between NFCs Relationships Average value Weights of rela- tionships NFC2-NFC1 0.88 Strong NFC1-NFC4 0.89 Strong NFC3-NFC4 0.38 Moderate NFC5-NFC1 0.47 Moderate Product Cost ( NFC 3 ) + moderate Product aesthetics (NFC 5 ) +strong + strong - moderate Competitiveness (NFC 4 ) Functionality (NFC 2 ) Product Quality (NFC 1 ) Figure 6. The final FCM Figure 7. MAMIE-Tool interface-NFCs’ relationships 6. Conclusion and Future Works This paper presents a process to identify and model rela- tionships between non-functional concerns. To do so, we chose fuzzy cognitive maps which have been introduced to model ill-structured complex systems. Building a fuzzy cognitive map follows an approach similar to hu- man reasoning and the human decision-making process. They can successfully represent knowledge and human experience; introduce concepts to represent the essential elements and the cause and effect relationships among the concepts to model the behaviour of any system. It is a very convenient, simple, and powerful tool, which is used in numerous fields. The process presented in this paper starts by identify- ing non-functional concerns. Then, the analyst builds an initial cognitive map for the identified non-functional concerns. In order to obtain consensus for a final cogni- tive map between experts, Delphi method is used. A fuzzy linguistic value for a specific relationship is ob- tained by calculates the average of all the evaluations values given by experts. Then s/he classifies it as weak, moderate or strong. Using fuzzy linguistics labels makes the fuzzy cognitive map more sensible. In addition, the presented process enables the experts to simulate idea from various viewpoints. We believe that using a fuzzy cognitive map to model non-functional concerns relationships proves useful and looks promising for a move from the conventional mod- elling toward developing computer based model. Thus, further works will concentrate on two objec- tives: Design an expert system based on fuzzy cognitive maps. Study the use of the presented process in the context of Aspect Oriented Requirements Engineering (AORE) area to handle interactions between aspects. AORE aims at addressing crosscutting concerns by means of aspects to provide their identification, separation, representation and composition. 7. Acknowledgements This research is partially supported by the PHC TASSILI project under the number 10MDU817. We thank the anonymous reviewers for providing valuable comments. REFERENCES [1] F. P. Brooks, “No Silver Bullet: Essence and Accidents of Software Engineering,” IEEE Computer Journal, Vol. 20, No. 1, 1987, pp. 10-19. [2] B. H. C. Cheng and J. M. Atlee, “Research Directions in Requirements Engineering,” Proceedings of the Future of Software Engineering Conference, Minneapolis, IEEE Computer Society, 2007, pp. 285-303. Relationship between Product cost and Competitiveness NFCs  Identifying and Modeling Non-Functional Concerns Relationships Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 826 [3] H. Bendjenna, N. Zarour and P. J. Charrel, “MAMIE, A Methodology to Elicit Requirements for an Inter-Com- pany Cooperative Information System,” Proceeding of IEEE Conference on Innovation on Software Engineering (ISE), Vienna, IEEE Computer Society, 2008, pp. 290- 295. [4] H. Bendjenna, N. Zarour and P. J. Charrel, “Enhancing the Elicitation Technique Selection Process in a Coopera- tive Distributed Environment,” Proceeding of the 14th Requirements Engineering Foundation for Software Quality Conference (REFSQ), Montpellier, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol. 5025, Springer, Heidelberg, 2008, pp. 23-36. [5] H. Bendjenna, M. Amroune, N. Zarour and P. J. Charrel, “Prioritizing Non-functional Concerns in MAMIE Meth- odology,” Proceeding of the Third International Confer- ence on Knowledge Science, Engineering and Manage- ment (KSEM), Vienna, Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelli- gence, Vol. 5914, Springer, Heidelberg, 2009, pp. 253- 262. [6] L. Chung, B. Nixon, E. Yu and J. Mylopoulos, “Non- Functional Requirements in Software Engineering,” Klu- wer Academic Publishers, New York, 2000. [7] P. J. A. Diaz, F. Trilnik and M. R. Campo, “How to Han- dle Interaction Concerns?” Proceedings of the ACM Con- ference on Object-Oriented Programming, Systems, Lan- guages, and Applications OOPSLA’00, Minneapolis, 2000, pp. 32-52. [8] J. Liu, D. Batory and S. Neduniry, “Modelling Interac- tions in Feature Oriented Software Design,” International Conference on Feature Interactions in Telecommunica- tions and Software Systems (ICFI), Leicester, 2005, pp. 178-197. [9] F. Sanen, E. Truyen, W. Joosen, N. Loughran, A. Rashid, A. Jackson, A. Nedos and S. Clarke, “Study on Interac- tion Issues,” AOSD-Europe Deliverable, Vol. 44, Leuven, 2006, pp. 1-31. [10] R. Axelrod, “Structure of Decision: The Cognitive Maps of Political Elites,” Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1976. [11] H. J. Zimmermann, “Fuzzy Set Theory and its Applica- tions,” Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1991. [12] S. Bueno and J. L. Salmeron, “Fuzzy Modeling Enter- prise Resource Planning Tool Selection,” Computer Stan- dards & Interfaces, Vol. 30, No. 3, 2008, pp. 137-147. [13] B. Boehm, “Characteristics of Software Quality,” North Holland Press, New York, 1978. [14] N. E. Fenton and S. L. Pfleeger, “Software Metrics: A Rigorous and Practical Approach,” 2nd Edition, Interna- tional Thomson Computer Press, London, 1997. [15] S. E. Keller, L. G. Khan and R. B. Panara, “Specifying Software Quality Requirements with Metrics,” In: R. H. Thayer and M. Dorfman, Eds., Tutorial: System and Software Requirements Engineering, IEEE Computer So- ciety Press, Piscataway, 1990, pp. 145-163. [16] M. R. Lyu, “Handbook of Software Reliability Engineer- ing,” McGraw-Hill, New York, 1996. [17] B. Boehm and H. In, “Identifying Quality-Requirement Conflicts,” IEEE Software Journal, Vol. 13, No. 2, 1996, pp. 25-35. [18] L. M. Cysneiros, J. C. S. P Leite and J. S. M. Neto, “A Framework for Integrating Non-Functional Requirements into Conceptual Models,” Requirements Engineering Journal, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2001, pp. 97-115. [19] T. G. Kirner and A. M. Davis, “Non-functional Require- ments of Real-Time Systems,” Advances in Computers Journal, Vol. 42, No. 1, 1996, pp. 1-37. [20] D. Kardaras and B. Karakostas, “The Use of Fuzzy Cog- nitive Maps to Simulate the Information Systems Strate- gic Planning Process,” Information and Software Tech- nology Journal, Vol. 41, No. 1, 1999, pp. 97-210. [21] B. Kosko, “Fuzzy Cognitive Maps,” International Jour- nal on Man-Machine Studies, Vol. 24, No. 1, 1986, pp. 65-75. [22] J. Bezdek, “Fuzzy Models-What Are They, and Why,” IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1993, pp. 1-6. [23] R. Taber, “Knowledge Processing with Fuzzy Cognitive Maps,” Expert Systems with Applications Journal, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1991, pp. 83-87. [24] C. Okoli and S. Pawlowski, “The Delphi Method as a Research Tool: An Example, Design Considerations and Applications,” Information & Management, Vol. 42, No. 1, 2004, pp. 15-29. [25] N. Bryson, A. Mobolurin and A. Joseph, “Generating Consensus Fuzzy Cognitive Maps,” Intelligent Informa- tion Systems, Vol. 8, No. 10, 1997, pp. 231-235. [26] N. C. Dalkey and O. Helmer, “An Experimental Applica- tion of the Delphi Method to the User of Experts,” Man- agement Science Journal, Vol. 9, No. 3, 1963, pp. 458- 467. [27] W. R. Zhang, S. S. Chen and J. C. Bezdek, “A Generic System for Cognitive Map Development and Decision Analysis,” IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cy- bernetics, Vol. 19, No. 1, 1989, pp. 31-39. [28] W. R. Zhang, S. S. Chen, W. Wang and R. King, “A Cog- nitive-Map-Based Approach to The Coordination of Dis- tributed Cooperative Agents,” IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Vol. 22, No. 1, 1992, pp. 103-114. [29] G. J. Klir and B. Youan, “Fuzzy Sets and Fuzzy Logic, Theory and Applications,” Prentice Hall, India, 2005. |