Advances in Physical Education 2012. Vol.2, No.4, 163-168 Published Online November 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ape) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ape.2012.24028 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 163 The Choices Made by Adolescents in High School Physical Education Classes: Effects of Grade, Age, and Gender on the Type of Activity Antonio Sabino da Silva Filho, Go Tani, Walter Roberto Correia, Umberto Cesar Corrêa Escola de Educação Física e Esporte, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil Email: umbertoc@usp.br Received June 13th, 2012; revised July 15th, 2012; accepted July 30th, 2012 The comprehension of the adolescent student’s choices might help teachers to select content and to de- velop strategies, since they show what in fact motivates the adolescent and how. This study investigated the choices made by adolescents in different high school physical education classes in relation to grade, age, and gender. The participants included 271 high school students enrolled in 10th, 11th, and 12th grade mixed classes (boys and girls). The design involved three programs in which a type of activity was de- veloped: walking, running, and futsal. Each program comprised five classes in relation to social, competi- tion, game-like, and fitness themes, from which the students chose. The dependent variable was the theme chosen, and trend analyses and multiple comparisons were performed. The results revealed that girls chose more walking activities with a social theme, and boys’ choices were related to competition and game-like themes. The fitness theme was the least popular for both girls and boys. Activities for girls that include a social focus might have a greater appeal, while competition and game-like activities would likely have greater acceptance among male students. No tendency related to the grades and ages progres- sions was observed. Keywords: Adolescent; Choice; Physical Education; Motivation; High School; Type of Activity Introduction In the past few decades, researchers have increasingly recog- nized the importance of understanding the relationship between adolescence and physical activity. On the one hand, for exam- ple, adolescence has been considered a critical period of deve- lopment in which individuals can begin to adopt certain health- related behaviors such as the regular practice of physical activi- ty (Aaron, Storti, Robertson, Kriska, & Laporte, 2002; Lubans, Morgan, & McCormack, 2011; Naul, Nupponen, Rychtecky, & Vuolle, 2002; Tammelin, Laitinen, & Nayha, 2004). Yet, on the other, studies have shown that the number of adolescents with health problems related to sedentary behavior or physical inac- tivity (i.e., obesity and cardiovascular diseases) has increased significantly (Alpert & Wilmore, 1994; Bar-Or, 2003; Bar-Or & Malina, 1995; Irwin Jr. & Millstein, 1986; Kohl & Hobbs, 1998; Sallis & Patrick, 1994). In fact, it has been consistently demonstrated that the highest rate of drop out in physical activ- ity programs occurs between the ages of 12 and 18 years (Cas- persen, Pereira, & Curran, 2000; Prusak & Darst, 2002; Telama & Yang, 2000). The promotion of physical activity in the adolescence, in- cluding in the school physical education programs, has also been a major focus of researchers (CDC, 1997; Cale, 2000; Fleming et al., 1998; Hultsman, 1999; Lawson, 1998; Mckenzie, 1999; Nahas, Barros, & Oliveira, 2005; Sallis & Patrick, 1994; Ward, Everhart, Dunaway, Fisher, & Coates, 1998; Welk, 1999). The role and potential of school-based physical educa- tion programs in promoting and stimulating students to acquire behaviors and knowledge related to adopting active life styles (Nahas, Oliveira, & Barros, 2005; Rink, 2009) has justified this research emphasis. The main locus of research concerns has been the adoles- cent’s motivation to participate in physical activities, and the choices he or she makes during physical education classes (Couturier, Chepko, & Coughin, 2005; Epstein, 1988, 1989; Fleming, Mitchell, Gorecki, & Coleman, 1999; Garn, Cothran, & Jenkins, 2011; Ishee, 2004; Johnson, 2008; Kovar, Kathy, Mehrhof, & Napper-Owen, 2001; Pagnano & Griffin, 2001; Prusak & Darst, 2002; Prusak et al., 2004; Ty-Ann & Oslin, 2003). It has been hypothesized that giving opportunities to adoles- cents to make choices during physical education classes will increase his/her intrinsic motivation, and, consequently, in- volvement, enjoyment, and participation (Kovar, Kathy, Me- hrhof, & Napper-Owen, 2001; Lonsdale, Sabiston, Raedeke, Ha, & Sum, 2009). It is thought that decision-making opportunities contribute to student’s sense of autonomy, independence, and freedom (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 1987) which are important de- velopmental characteristics of the adolescent (Bycura & Darst, 2001; Corrêa & Silva Filho, 2008). For example, Prusak and colleagues (Prusak & Darst, 2002; Prusak et al., 2004; Ward et al., 2008) investigated the choices of adolescent girls in 7th and 8th grade physical education classes. Specifically, Prusak and Darst (2002) examined the choices of adolescent girls who were offered an opportunity to choose between different walking activities. Walking was cho- sen because it is less likely to be associated with pre-existing attitudes about physical education, does not depend on skill level, offers a greater degree of experimental control, and is in  A. S. DA S. FILHO ET AL. line with US recommendations of participation in physical ac- tivity in adulthood and old age. In this study, girls had to choose among walking activities with social, exercise/fitness, game-like, or competition themes. The results showed that so- cial walking activities, in which the girls could interact with the colleagues, were considered the most attractive ones. Prusak’s later studies investigated the effect of choice on motivation (Prusak et al., 2004), and on self-determination and physical activity levels (Ward et al., 2008). They revealed that the girls who had freedom of choice were more intrinsically motivated than those without opportunities of choice, but no effects were observed in the level of physical activity. In another study (Corrêa & Silva Filho, 2008), the adoles- cents’ choices were investigated with both boys and girls in mixed physical education classes. It was observed that adoles- cents, even in mixed classes, chose walking activities with so- cial emphases. The girls chose social walking more than boys, who more often chose walking activities with competition themes. The exercise/fitness walking theme was the least cho- sen. In sum, previous researches have suggested that giving op- portunities to adolescents to make choices during physical edu- cation classes will increase his/her intrinsic motivation, and, consequently, involvement, enjoyment, and participation. It has been hypothesized that decision-making opportunities contri- bute to student’s sense of autonomy, independence, and free- dom, which are important developmental characteristics of the adolescent. These findings have implications not only in pro- viding a better understanding of the adolescent student’s moti- vations, but also in helping teachers to select content and to develop strategies, since they show what in fact motivates the adolescent and how. In the present study, we extended the pre-existing knowledge by investigating the choices made by adolescent students of both genders in relation to the following educational level (high school). In previous studies (Corrêa & Silva Filho, 2008; Pru- sak & Darst, 2002; Prusak et al., 2004), adolescents were in the 7th and 8th grades, with an average age of 11 years. However, adolescence is a long period of development that extends to approximately 20 years (Lerner & Galambos, 1998; Race, 1995). In this period, the important and fast-paced physical, psychological, and social changes take place together with the transition from secondary/middle school to high school (Shaffer, 2005). Furthermore, these changes are accompanied by an in- creasing in the diversity of interests of the adolescent, including those related to the type of physical activity (Lubans, Morgan, & McCormack, 2011; Tammelin et al., 2004; Fleming et al., 1998; Hultsman, 1999; Lawson, 1998; Ward et al., 2008). The current study, therefore, sought to understand the nature of choices made by adolescents in physical education classes rela- tive to high school grade level, age, gender, and type of activity. Method Participants The participants included 271 high school students enrolled in 10th, 11th, and 12th grade mixed classes (boys and girls), and who were between the ages of 15 and 23 years (Table 1). Importantly, the relationship between age and educational level was not linear because many students had retention. All stu- dents participated voluntarily and parents’ consent was ob- Table 1. Characteristics of the students in high school physical education classes in relation to grade (10th, 11th, 12th), gender (boys [♂] and girls [♀]) , age (mean and standard deviation), and number of students (n). Grade Gender Age n ♂ 16.0 (0.8) 69 10th ♀ 15.7 (0.6) 42 ♂ 16.8 (0.7) 39 11th ♀ 17.0 (0.8) 39 ♂ 17.8 (0.4) 32 12th ♀ 18.2 (1.0) 50 tained through the high schools’ administrators. This study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board of the Uni- versity of São Paulo. Procedures This study was conducted during physical education classes, by the teacher, as part of the planned curriculum. Three pro- grams were developed in a counterbalanced way involving the following activities: walking, running and futsal (indoor soc- cer). In each program, during the first class, it was contextualized with explanations about the benefits of the activity. In the fol- lowing three consecutive classes, students were asked to choose from four different practice schedules, with the following themes: social, game-like, competition, and fitness. For the walking activity these themes were: Social—Friends, music and fun: Students walked during 20 minutes. They could interact with each other and bring sound equipment or CDs to be played on equipment sup- plied by the school. Game-like—Treasure hunt: Students were divided into groups according to the number of participants in the activity and carried out the walking for 20 minutes. Every 4 minutes they received a card with a clue about anything to be dis- covered (a famous sportsman, the name of a sport, etc.). When they received a new card, the clues will become easier. Won the team at the end of the time discovered first.Competition—Basketball Tournament: Students were divided into teams and performed the activity during 20 mi- nutes, around the basketball court. When they passed through the baskets, a student with ball possession per- formed a throw. The team that converted more points won. Fitness—Circuit Exercise: Students walked for 20 minutes. Every four minutes they stopped and performed a different exercise (handstand with feet on the wall); 20 abs; Crab (4 supports in the supine position); 20 dorsals; push-ups. Concerning the running activity the themes above cited were: Social—Basic running: during 20 minutes the students ran around the outdoor volleyball court, at a pace that did not prevent them from interacting with colleagues, without los- ing focus on the activity. Game-like—Summing points: the game was performed individually. Students ran for 20 minutes. Along the way, there were numbered cards scattered faces down on a table. Every 4 minutes, they should draw a card (without delay). Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 164  A. S. DA S. FILHO ET AL. At the end, the students added up their cards. One who ob- tained the highest score won. It was not allowed to pick more than one card at a time. Competition—Cross-Country: In groups, students ran in a specific space of the block containing some obstacles. When finalizing a certain amount of turns, each student re- ceived a letter numbered related to its order of arrival. At the end, the groups added their letters and one with more points won. Fitness—Running with variations: the students ran during 20 minutes around the volleyball court. Cones placed every five meters showed a different form of running: elevating the heels, knees, leg stretched out in front, running back, and sliding as if on roller skates. And, regarding the futsal the following activities were pro- vided for the student’s choices: Social—Touching the ball in groups: during 20 minutes the students traveled a certain space, holding hands in a circle, with two or more balls inside. During the journey, they could not let the balls get out of the circle. If that happened, they re-started the activity, without prejudice. Game-like—Taking care of the ball: individually, students should drive with your feet a futsal ball freely around the court for 20 minutes. They should protect their ball while trying to kick the ball from another colleague. Won the student who remained more time with his ball. Competition—Championship of mini-goal: the students were divided into teams and competed in 4 rounds of mini-soccer court with mini-goals, so teams are faced throughout the 20 minutes. Won the team with more goals in four minutes. Every four minutes the teams changed their opponent. At the end of 20 minutes the team that won more matches. Fitness—Circuit of Exercises: Students performed passes in pairs moving around the court for 20 minutes. Every four minutes they performed a different exercise: pass with the head in pairs; abdominal passing the ball with the head while elevate the trunk, passing the ball into double, carry- ing the ball to mate running back and forth. The students were allowed to change practice schedules on each of three days, at their own discretion. At the beginning of each class, all practice schedules were offered to the students, along with accompanying explanations and instructions. During the fifth class (the last), the students were asked to discuss their experiences and activities, and to explain their motivations and choices, which were collected as data. The physical education classes were held twice per week, with duration of 50 minutes, on an indoor sports court and an outdoor volleyball court. Data Analysis The dependent variable was the choice of theme in each ac- tivity: social, competition, game-like and fitness. The results were analyzed to identify main effects of choices in relation to 1) grade and gender; and 2) age and gender interactions in each type of activity. These analyses were conducted using Trend Module (Trend Analysis and Multiple Comparisons) of PEPI software (Gahlinger & Abramson, 2005; Cattuzzo, Basso, Hen- ry, & Oliveira, 2010). For all analyses the level of significance was p < .05 Results Walking Grade and gender. Statistical analyses revealed effects for all grades in relation to both males and females (Table 2). With regard to the 10th graders, the results revealed that the boys chose more walking activities with game-like and competition themes than those that were considered social or related to fit- ness (p < .01). The girls chose those that were considered social more than any other type of walking activity (p < .01). Regarding the 11th graders, the boys chose more walking ac- tivities with game-like and competition themes than of a fitness theme (p < .05), the girls chose the social theme most fre- quently, and the fitness theme least frequently (p < .01). Finally, with regard to the 12th graders, the results indicated that the boys chose more walking activities with game-like and competition themes than for fitness (p < .01), and they chose the competition theme more often than the social theme (p < .01). The girls chose the social walking activity with greater frequencies than for the remaining themes (p < .01). Age and gender. Statistical analyses did not reveal significant differences for boys aged 19 years and older (Table 3). The 15-year-old boys more frequently chose walking activities with a competition theme than one of fitness (p < .05). The girls picked the social walking activity most frequently (p < .01). For the 16-year-old students, the boys more often chose walking activities with game-like and competition themes than with a social theme (p < .01), and the competition walking ac- tivity was the most popular (p < .01). The girls most frequently chose the social walking activity (p < .01). The 17-year-old boys chose the walking activity with a fit- ness theme least frequently (p < .01). The 17-year-old girls preferred the social walking activity over the other types (p < .01), and preferred the competition theme to the fitness theme (p < .05). The 18-year-old boys most frequently chose game-like and competition themes over the fitness theme (p < .01), and they chose the game-like walking theme over the social theme (p < .05). The girls most frequently chose the social theme (p < .01), and preferred the walking activity with a competition theme over the fitness theme (p < .05). For the 19-year-olds, differences were found only for the girls, who most frequently chose the social theme, and least Table 2. Results of the trend analysis and multiple comparisons conduced for boys (♂) and girls’ (♀) choices of all school grades (10th, 11th, 12th). (Degrees of freedom = 3 for all comparisons) Grade Gender Walking Running Futsal ♂ 2 = 38.60, p < .01 2 = 35.43, p < .01 2 = 30.58, p < .00 10th ♀ 2 = 150.05, p < .01 2 = 59.30, p < .01 2 = 7.32, p > .05 ♂ 2 = 11.07, p < .01 2 = 5.23, p < .05 2 = 21.31, p < .01 11th ♀ 2 = 61.03, p < .01 2 = 34.77, p < .01 2 = 11.34, p < .01 ♂ 2 = 33.05, p < .01 2 = 21.00, p < .01 2 = 25.44, p < .01 12th ♀ 2 = 34.31, p < .05 2 = 41.64, p < .05 2 = 5.58, p > .05 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 165  A. S. DA S. FILHO ET AL. Table 3. Results of the trend analysis and multiple comparisons conduced for boys (♂) and girls’ (♀) choices of all ages (15, 16, 17, 18 and 19 years or more) (Degrees of freedom = 3 for all comparisons). Age Gender Walking Running Futsal ♂ 2 = 09.19, p < .05 2 = 12.74, p < .01 2 = 26.96 p < .01 15 ♀ 2 = 88.95, p < .01 2 = 31.43, p < .01 2 = 1.37, p > .05 ♂ 2 = 27.96, p < .01 2 = 24.92, p < .01 2 = 27.09, p < .01 16 ♀ 2 = 51.70, p < .01 2 = 18.07, p < .01 2 = 21.48 p < .01 ♂ 2 = 25.78, p < .01 2 = 8.20, p < .05 2 = 5.63 p > .05 17 ♀ 2 = 44.81, p < .01 2 = 43.56, p < .01 2 = 6.12, p > .05 ♂ 2 = 21.44, p < .01 2 = 23.44, p < .01 2 = 18.33, p < .01 18 ♀ 2 = 36.59, p < .01 2 = 29.12, p < .01 2 = 9.97, p < .01 ♂ 2 = 5.24, p > .05 2 = 0.98, p > .05 2 = 10.22, p < .05 19+ ♀ 2 = 12.74, p < .01 2 = 16.30, p < .01 2 = 1.48, p > .05 frequently chose the fitness theme (p < .05). Running Grade and gender. Statistical analyses did not revealed sig- nificant differences for the boys in the 11th grade (Table 2). With regard to the 10th grade, the boys chose the running activ- ity with a fitness theme least frequently (p < .01), and the girls chose the social running activity with greater frequencies than for the remaining themes (p < .01), and more running activities with game-like and competition themes than a fitness theme (p < .05). The girls in the 11th grade chose those that were considered social more than any other type of running activity (p < .01). Finally, with regard to the 12th graders, the results indicated that the boys chose more running activities with game-like and competition themes than for fitness (p < .01), and the girls chose the social running activity with greater frequencies than for the remaining themes (p < .01) and preferred the game like theme to the fitness theme (p < .05). Age and gender. Statistical analyses did not reveal significant differences just for boys aged 19 years and older (Table 3). For the 15-year-old boys, the game like and competition themes were preferred to the fitness theme (p < .05), and the girls picked the social running activity most frequently (p < .01). The 16-year-old boys chose the running activity with a fit- ness theme least frequently (p < .01), and the girls chose more running activities with game-like and social themes than of a fitness theme (p < .05). Regarding to the 17-year-old boys, they most frequently chose running activity with competition theme over the fitness theme (p < .05), and the 17 year-old girls preferred the social running activity over the other types (p < .01). The 18-year-old boys most frequently chose game-like and competition themes over the fitness theme (p < .01), and the 18 year-old girls preferred the social running activity over the other types (p < .01). For the 19-year olds, differences were found only for the girls, who most frequently chose the social theme, over the game-like, competition and fitness themes (p < .05). Futsal Grade and gender. Statistical analyses revealed effects for all grades in relation to the boys. To the girls was revealed just in the 11th grade (Table 2). With regard to the 10th and 11th graders, the results revealed that the boys chose more futsal activities with game-like and competition themes than that was considered social (p < .01). In the 10th grade the boys chose more futsal activity with game-like theme than of a futsal fit- ness theme (p < .01), and in the 11th grade chose more futsal activity with competition theme than of a fitness theme (p < .05). The girls in the 11th grade chose more the futsal activity with social theme to the futsal activity with a game-like theme (p < .01). Finally, with regard to the 12th grade, the results indicated that the boys chose more futsal activities with game-like and com- petition themes than of a social theme (p < .05), and chose more futsal activity with competition theme than for fitness theme (p < .01). Age and gender. Statistical analyses did not reveal significant differences for boys aged 17 years and the girls aged 15, 17 and 19 years old (Table 3). The results revealed that the 15-year- old boys chose more futsal activities with game-like and com- petition themes than those were considered social or related to fitness (p < .05). For the 16-year-old students, the boys more often chose fut- sal activities with competition and game-like themes than with a social theme (p < .01) and chose more futsal activity with game-like theme than for fitness (p < .05). The 16 years-old- girls preferred the social futsal activity over the other types (p < .05) The 18-year-old boys most frequently chose futsal activity with competition theme over the fitness and the social themes (p < .01). The 18 years-old girls preferred the futsal activity with a social theme over the game-like theme (p < .05). Finally, the 19-year-old boys frequently chose the competi- tion theme over the social theme (p < .05). Discussion This study investigated the choices made by adolescents during walking, running, and futsal physical education high school classes in relation to grade, age, and gender. The results showed the following general tendencies of choices, or prefe- rences: 1) social for girls; 2) competition and game-like for boys; and 3) fitness least frequently chosen by both girls and boys. The girls’ choices were similar to those observed in the study of Pruzak and Darst (2002) in which walking activities with a strong social component were more attractive for adolescent girls than other themes because they provide possibilities for peer interaction. These authors observed that girls who have the opportunity to interact with their peers, do so, and they openly demonstrate satisfaction. Payne and Barnett (2006) suggested that adolescents are increasingly dependent on friends to meet many of their basic needs for social acceptance, and that some activities are undertaken by groups of friends. It appears that the social component is highly important to Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 166  A. S. DA S. FILHO ET AL. adolescent development. Cole and Cole (2004) observed that in the adolescent, significant changes in the biological system are associated with equally significant changes in the way they interact with families and peers. The social development of the adolescent, claimed Race (1995), takes place in three main phases: 1) at first, there is a tendency for the adolescent to in- teract with peers of the same gender; 2) later, there is a ten- dency for adolescents to increase their interactions with groups of a different gender; and 3) thirdly, there occurs a trend called disintegration, in which loving relationships evolve. In this stage, individual relationships are more important than group relationships. Importantly, although the friends were reported as the most important reasons for boys and girls students select activities (Lubans, Morgan, & McCormack, 2011), our results indicate that the tendency in choosing the social theme is specific to the girls. Instead, the boys most often chose practice schedule that are related to competition and are game-like. These results are similar to those found in a previous study on younger adoles- cents (Corrêa & Silva Filho, 2008). According to these authors, the competition and game-like choice tendencies could be re- lated to the developmental characteristics of the boys. Some claim that, for boys, participation and quality of performance are important for status reasons (McCabe, Roberts, & Morris, 1991). However, there appears to be an effect of activity speci- ficity on the boys’ choices. Results revealed that boys did not prefer the competition theme during the running program. It is possible that the competitive running has demanded higher physical conditioning to obtain success in comparing to the other activities. For example, the running has been preferred by individuals more physically active than walking (Greiwe & Kohrt, 2000). Our results suggest that changes in high school peer groups—the result of age and grade transitions—which can influence students’ interests and expectations about physical activity, did not affect the choices they made. Although some variations have been observed, the results did not show any general tendency of change of focus of choice, as grades and ages progressed. Based on this one could say that the social preference for girls and the competition and game-like for boys follow together with the grade and age changes in adolescence. A particularly interesting finding is that the fitness theme was the least popular of all choices, both for boys and girls. It has been observed that fitness-type activities fit the desires and expectations of younger and older adults more than for adoles- cents (Corbin, 2001). But, why, then, don’t adolescents like fitness activities? One possible explanation could be related to the nature of the activities. Fitness can be viewed as a subset of physical activity that is planned, structured, and repetitive (Caspersen, Pereira, & Curran, 2000). Perhaps it is these cha- racteristics—structured and repetitive—that don’t appeal to adolescents. Exception was observed with regarding the girls’ choices in the futsal activity. Results showed that the social preference was accompanied by that related to the fitness theme. One pos- sible reason for these differences may be related to the social and cultural influences. That is, although the sport of futsal is known and practiced worldwide (Corrêa, Alegre, Freudenheim, Santos, & Tani, 2012) some students reported that it was not a feminine activity. They also said they feared the possibility of physical contact with stronger guys. Similar reports can be found in the study of Hill and Cleven (2005), pointing to lack of models for girls in team sports. In conclusion, the findings of the present study revealed that the high school girls more frequently chose an activity with a social theme; boys’ choices were related to competition and game-like themes. The fitness theme was the least popular for both girls and boys. The practical implications are that high school teachers might use these findings to increase student participation in walking, running, and futsal activities programs. Activities for girls that include a social focus might have a greater appeal, while competition and game-like activities would likely have greater acceptance among male students. Since different emphases were investigated within three spe- cific activities, further research should analyze adolescents’ choices in other types of physical activity. REFERENCES Aaron, D. J., Storti, K. L., Robertson, R. J., Kriska, A. M., & Laporte, R. E. (2002). Longitudinal study of the number and choice of leisure time physical activities from mid to late adolescence: Implications for school curricula and community recreation programs. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 11, 1075-1080. doi:10.1001/archpedi.156.11.1075 Alpert, B. S., & Wilmore, J. H. (1994). Physical activity and blood pressure in adolescents. Pediatric Exercise Science, 6, 361. Bar-Or, O., & Malina, R. M. (1995). Activity, fitness, and health of children and adolescents. In L. W. Y. Cheung, & J. B. Richmond (Eds.), Child health, nutrition, and physical activity (pp. 79-123). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Bycura, D., & Darst, P. W. (2001). Motivating middle school students: A health-club approach. The Journal of Physical Education, Recrea- tion & Dance, 72, 24-26. Cale, L. (2000). Physical activity promotion in secondary schools. European Physical Education Review, 6, 71-90. doi: 10.1177/1356336X000061006 Caspersen, C. J., Pereira, M. A., & Curran, K. M. (2000). Changes in physical activity patterns in the United States, by sex and cross-sec- tional age. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 32, 1601- 1609. Cattuzzo, M. T., Basso, L., Henrique, R. S., & Oliveira, J. S. P. (2010). Desempenho em uma tarefa de timing coincidente e velocidade do estímulo: O uso de índices de acertos. Revista Brasileira de Cinean- tropometria & Desempenho Humano, 12, 127-133. Center for Disease Control (CDC) (1997). Guidelines for school and community programs to promote lifelong physical activity among young people. Journal o f S c hool Health, 67, 202-219. Cole, M., & Cole, S. R. (2004). O desenvolvimento da criança e do adolescente. Porto Alegre, RS: Artmed. Corbin, C. B. (2001). The “untracking”of sedentary living: A call for action. Pediatric Exercise Sc ie nc e , 13, 347-356. Corrêa, U. C., Alegre, F. A. M., Freudenheim, A. M., Santos, S., & Tani, G. (2012). The game of futsal as an adaptive process. Nonlin- ear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences , 16, 185-204. Corrêa, U. C., & Silva, F. A. S. (2008). As escolhas de adolescentes em relação a atividades de caminhada em aulas de educação física. Revista Brasileira de Ed u c ação Física e Esport e , 22, 149-159. Couturier, L. E., Chepko, S., & Coughlin, M. A. (2005). Student voices? What middle and high school students have to say about physical education. The Physical Educator, 62, 114-122. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-de- termination in human behavi or . New York: Plenum. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1987). The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 1024-1037. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.53.6.1024 Epstein, J. (1988). Effective schools or effective students? Dealing with diversity. In R. Hawkins, & B. Macrae (Eds.), Policies for Ame- rica’s public schools (pp. 89-126). Norwood: Ablex. Epstein, J. (1989). Family structure and students motivation: A devel- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 167  A. S. DA S. FILHO ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 168 opment perspective. In C. Ames & R. Ames (Eds.), Research on mo- tivation in educati on (pp. 259-295). New York: Academic Press. Fleming, D. S., Mitchell, M., Gorecki, J. J., & Coleman, M. M. (1998). Students change and so do good programs: Addressing the interests of multicultural secondary students. The Journal of Physical Educa- tion, Recreation & Dance, 70, 79-83. Gahlinger, P. M., & Abramson, J. H. (2005). Computer programs for epidemiologic Analysis—Pepi (Version 2.05). Georgia: USD Inc. Garn, A. C., Cothran, D. J., & Jenkins, J. M. (2011). A qualitative analysis of individual interest in middle school physical education: Perspectives of early-adolescents. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 16, 223-236. doi:10.1080/17408989.2010.532783 Greiwe, J. S., & Kohrt, W. M. (2000). Energy expenditure during walking and jogging. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fit- ness, 40, 297-302. Hill, G., & Cleven, B. (2005). A comparison of 9th grade male and female physical education activities preferences and support for co- educational groupings. The Physical Educator, 62, 187-197. Hultsman, W. Z. (1999). Promoting physical activity through parks and recreation: A focus on youth and adolescence. The Journal of Physi- cal Education, Recreatio n & Dance, 70, 1-5. Irwin, J. C. E., & Millstein, S. G. (1986). Biopsychosocial correlates of risk-taking behaviors during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence Health and Care, 7, 825-965. Ishee, J. H. (2005). The effect of choice on motivation. The Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 75, 8. Johnson, D. A. (2008). The effect of choice on motivation. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 76, 8. Kohl, H. W., & Hobbs, K. E. (1998). Development of physical activity behaviors among children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 101, 549-554. Kovar, S. K., Ermler, K. L., Mehrhof, J. H., & Napper-Owen, G. E. (2001). Choosing activity units to promote maximum participation: Creative physical education curricula. The Physical Educator, 58, 114-122. Lawson, H. A. (1998). Rejuvenating, reconstituting, and transforming physical education to meet the needs of vulnerable children, youth, and families. Jo u r na l o f T e a c hi n g in Physical Education, 18, 2-25. Lerner, R. M., & Galambos, N. L. (1998). Adolescent development: Challenges and opportunities for research, programs and policies. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 413-446. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.413 Lonsdale, C., Sabiston, C. M., Raedeke, T. D., Ha, A. S., & Sum, R. K. (2009). Self-determined motivation and students’ physical activity during structured physical education lessons and free choice periods. Preventive Medicine, 48, 69-73. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.09.013 Lubans, D. R., Morgan, P. J., & McCormack, A. (2011). Adolescents and school sport: The relationship between beliefs, social support and physical self-perception. Physical Education and Sport Peda- gogy, 16, 237-250. doi:10.1080/17408989.2010.532784 McCabe, A. E., Roberts, B. T., & Morris, T. E. (1991). Athletic activity, body image, and adolescent identity. In L. Diamant (Ed.), Mind-body maturity: Psychological approaches to sports, exercise and fitness (pp. 91-103). New York: Hemisphere. Mckenzie, T. L. (1999). School health-related physical activity pro- grams: What do the data say? The Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 70, 16-19. Nahas, M. V., Barros, M. V. G., & Oliveira, E. S. (2005). Promoção da saúde na adolescência: O papel da educação física. Revista Brasileira de Atividade Física & Saúde, 10, 13-24. Naul, R., Nupponen, N., Rychtecky, A., & Vuolle, P. (2002). Physical fitness, sporting lifestyles and Olympic ideals: Cross cultural studies on youth sport in Europe. Schorndorf: Verlag Karl Hofmann. Pagnano, K., & Griffin, L. (2001). Making intentional choices in physical education. The Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 72, 38-46. Payne, L. L., & Barnett, L. A. (2006). Leisure and recreation across the life span. In H. Kinetics (Ed.), Introduction to recreation and leisure. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Prusak, K. A., & Darst, P. W. (2002). Effects of types of walking ac- tivities on actual choices by adolescent female physical education students. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 21, 230-241. Prusak, K. A., Treasure, D. C., Darst, P. W., & Pangrazi, R. P. (2004). The effects of choice on the motivation of adolescent girls in physi- cal education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 23, 19-29. Rink, J. (2009). Designing the physical education curriculum: Promot- ing active lifestyles. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. Sallis, J. F., & Patrick, K. (1994). Physical activity guidelines for ado- lescents: Consensus statement. Pediatric Exercise Science, 6, 302- 314. Shaffer, D. R. (2005). Psicologia do desenvolvimento: Infância e adolescência. São Paulo: Pioneira Thomson Learning. Tammelin, T., Laitinen, J., & Nayha, S. (2004). Change in the level of physical activity from adolescence into adulthood and obesity at the age of 31 years. International Journal of Obesity, 28, 775-782. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0802622 Telama, R., & Yang, X. (2000). Decline of physical activity from youth to young adulthood in Finland. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 32, 1617-1622. Ty-Ann, G., & Oslin, J. (2003). Primary school students? Choices for a healthy active lifestyle. The Journal of Physical Education, Recrea- tion & Dance, 74, 52-57. Ward, B., Everhart, B., Dunaway, D., Fisher, S., & Coates, T. (1998). Emphasizing fitness objectives in secondary physical education. The Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 69, 33-35. Ward, J., Wilkinson, C., Graser, S. V., & Prusak K. A. (2008). Effects of choice on student motivation and physical activity behavior in physical education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 27, 385-398. Welk, G. J. (1999). The youth physical activity promotion model: A conceptual bridge between theory and practice. Quest, 51, 5-23.

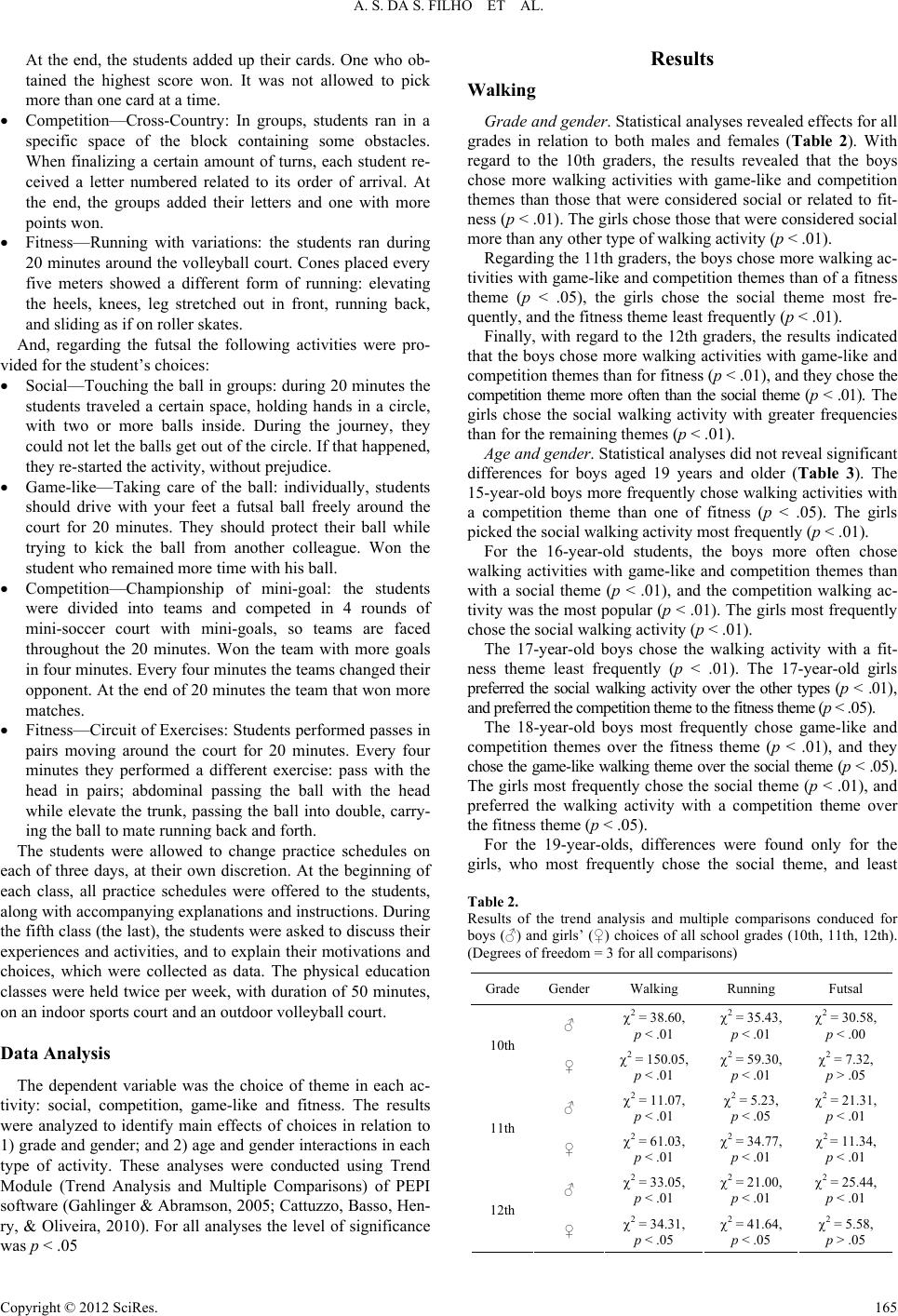

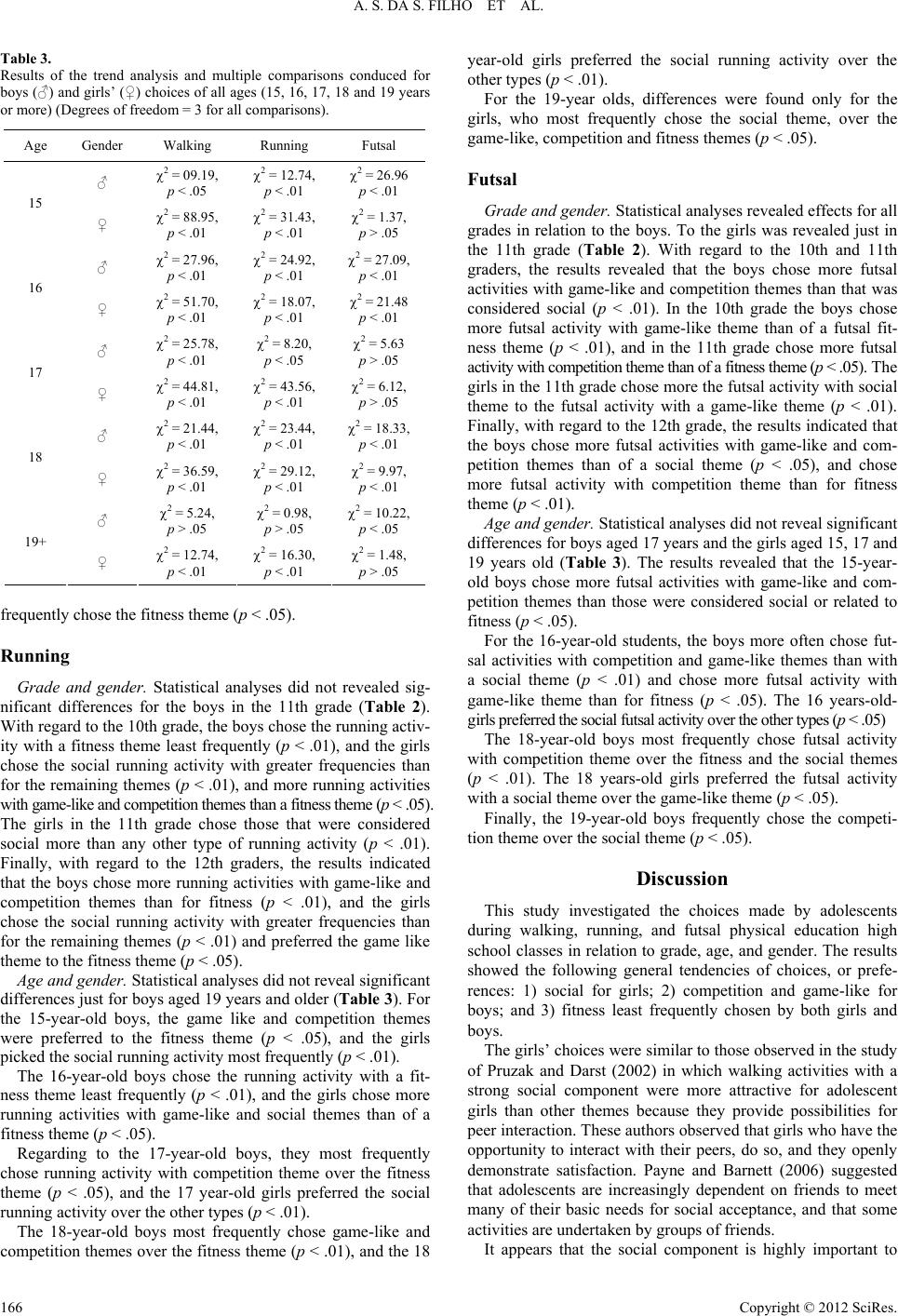

|