Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

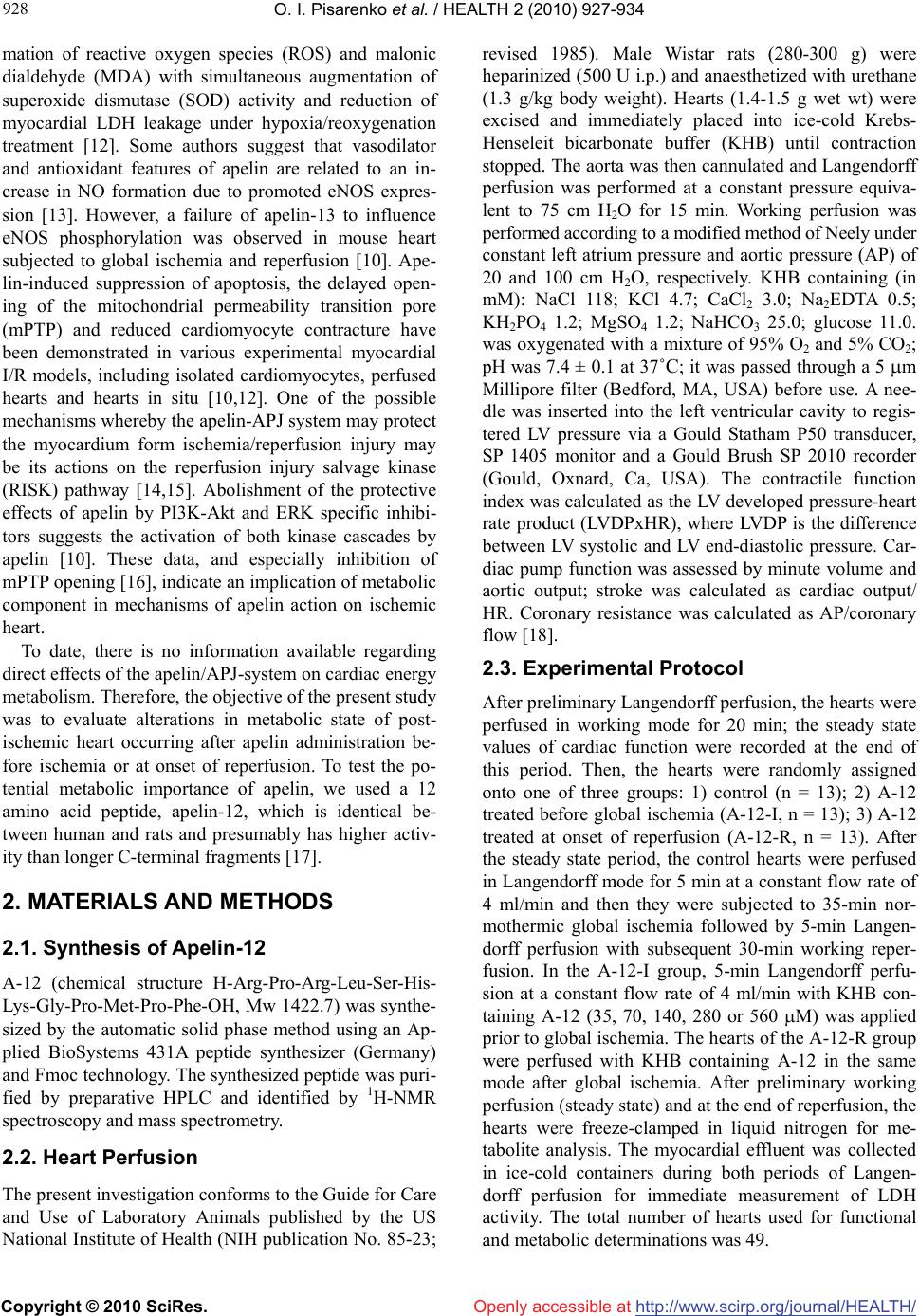

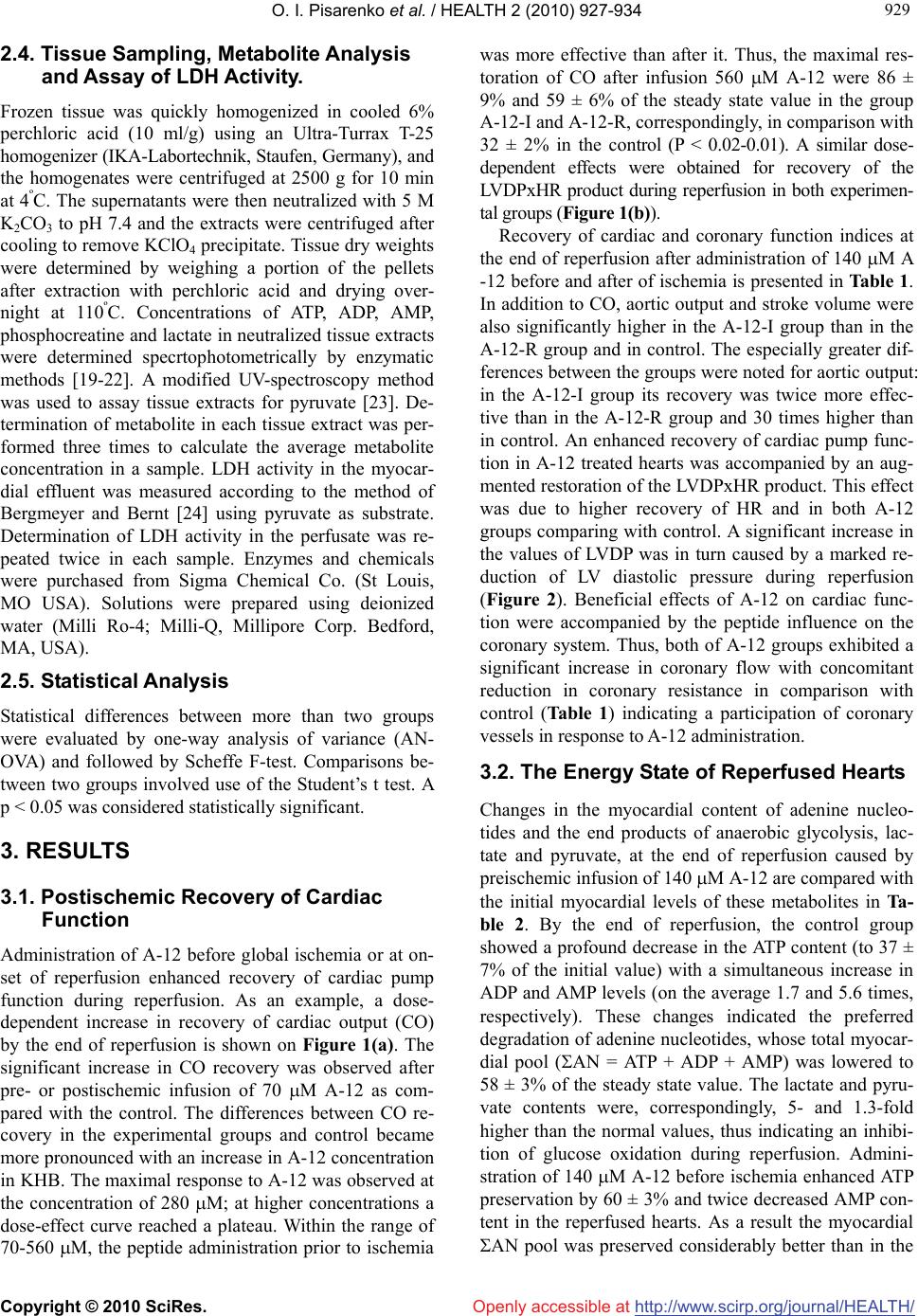

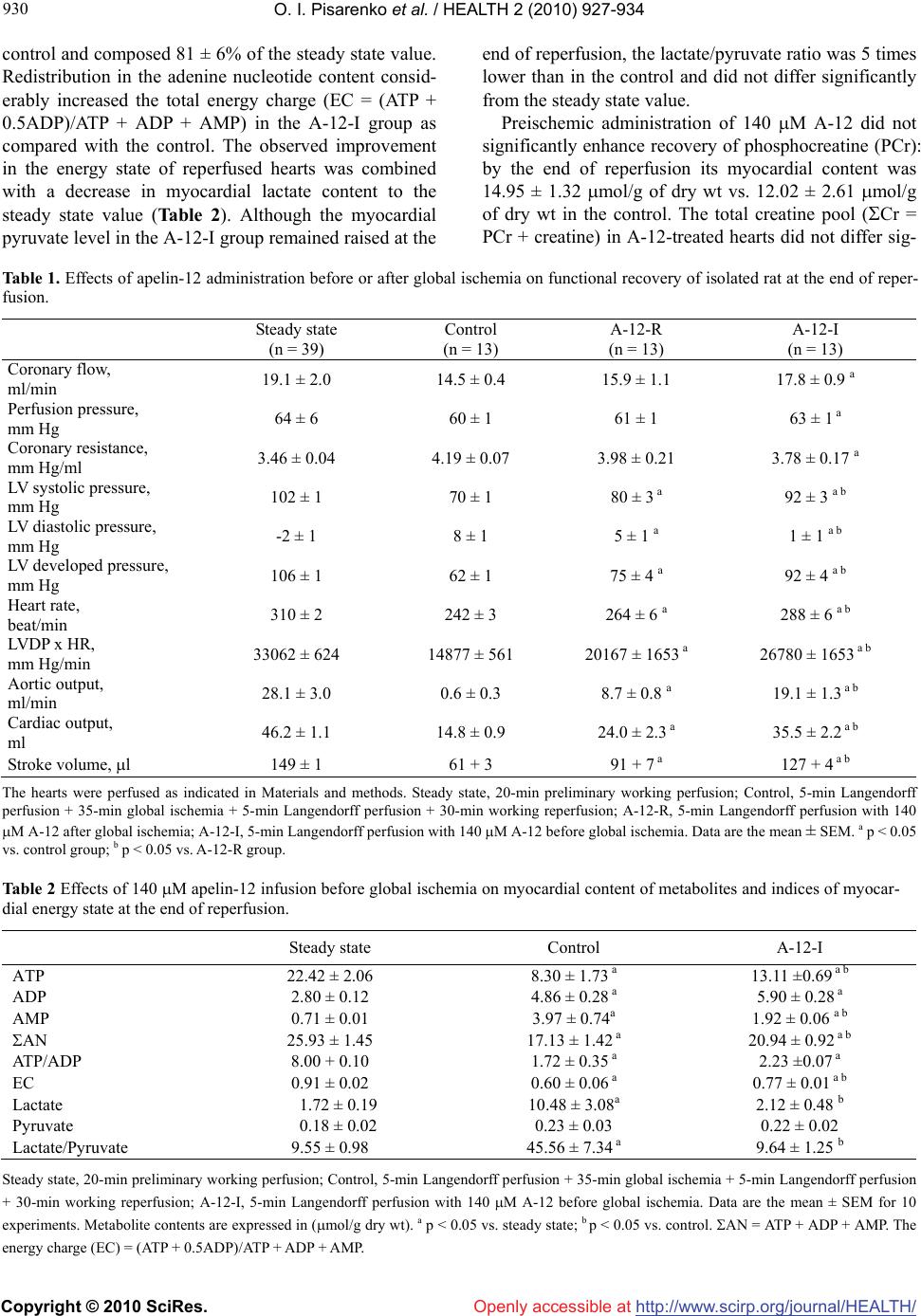

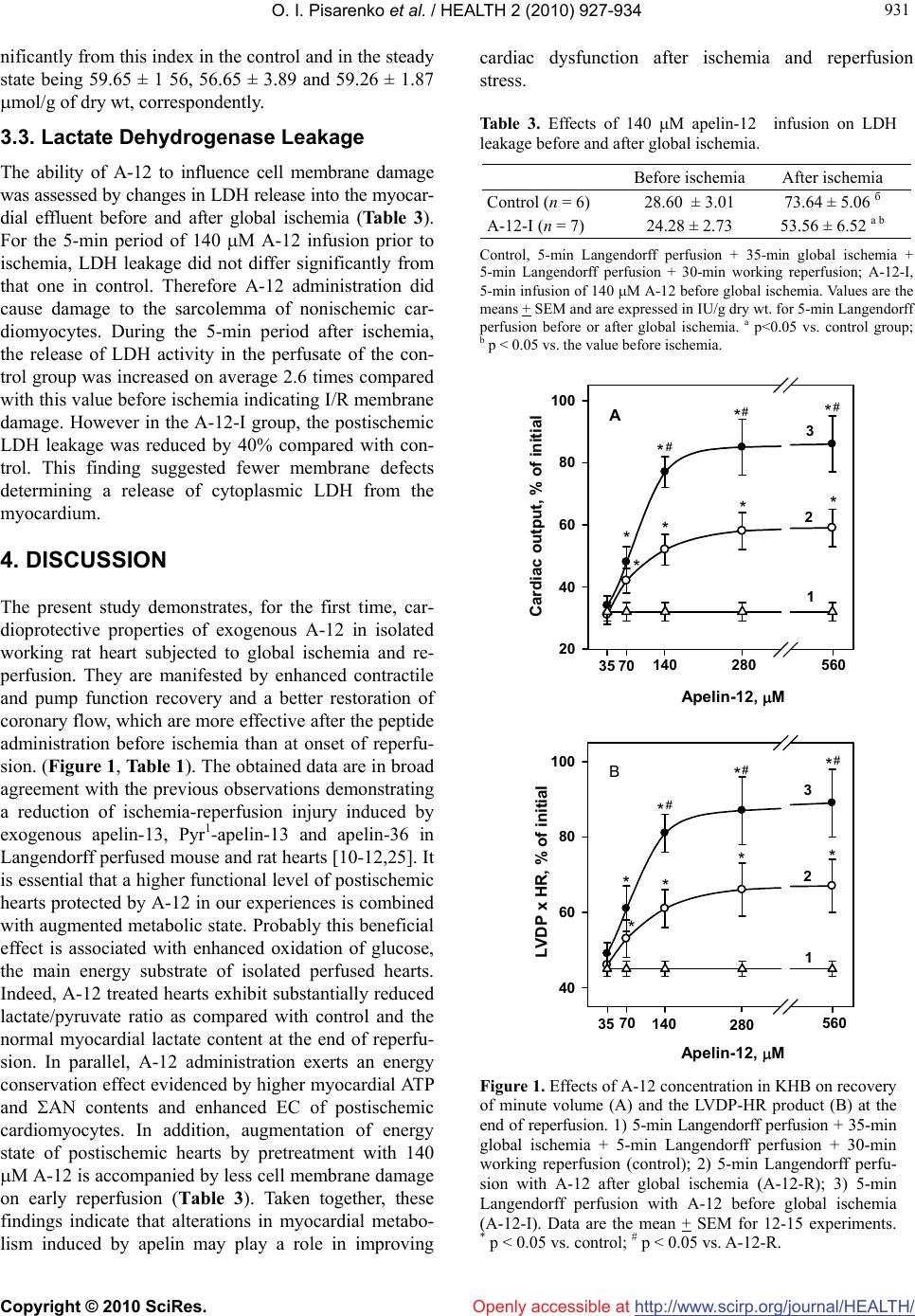

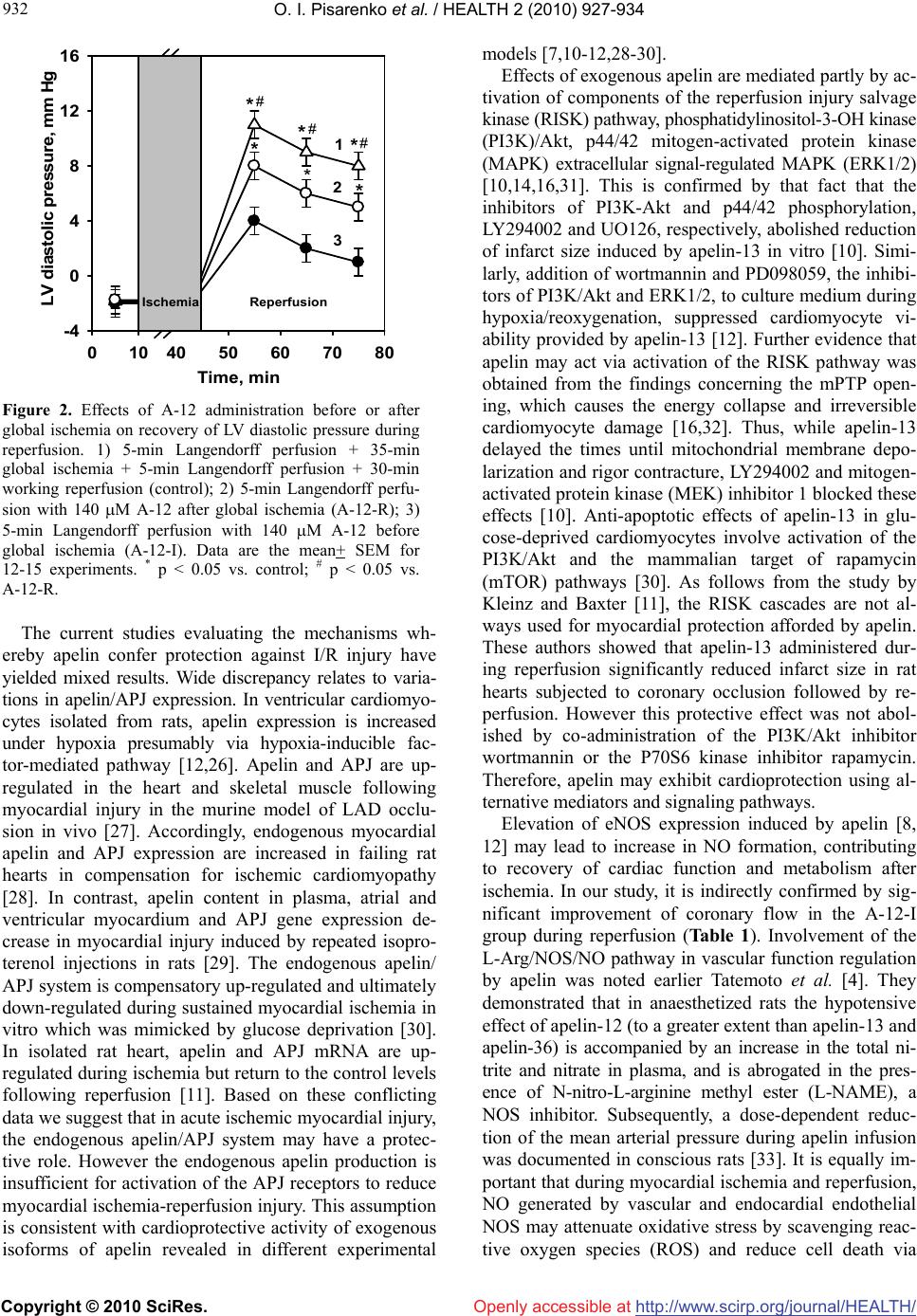

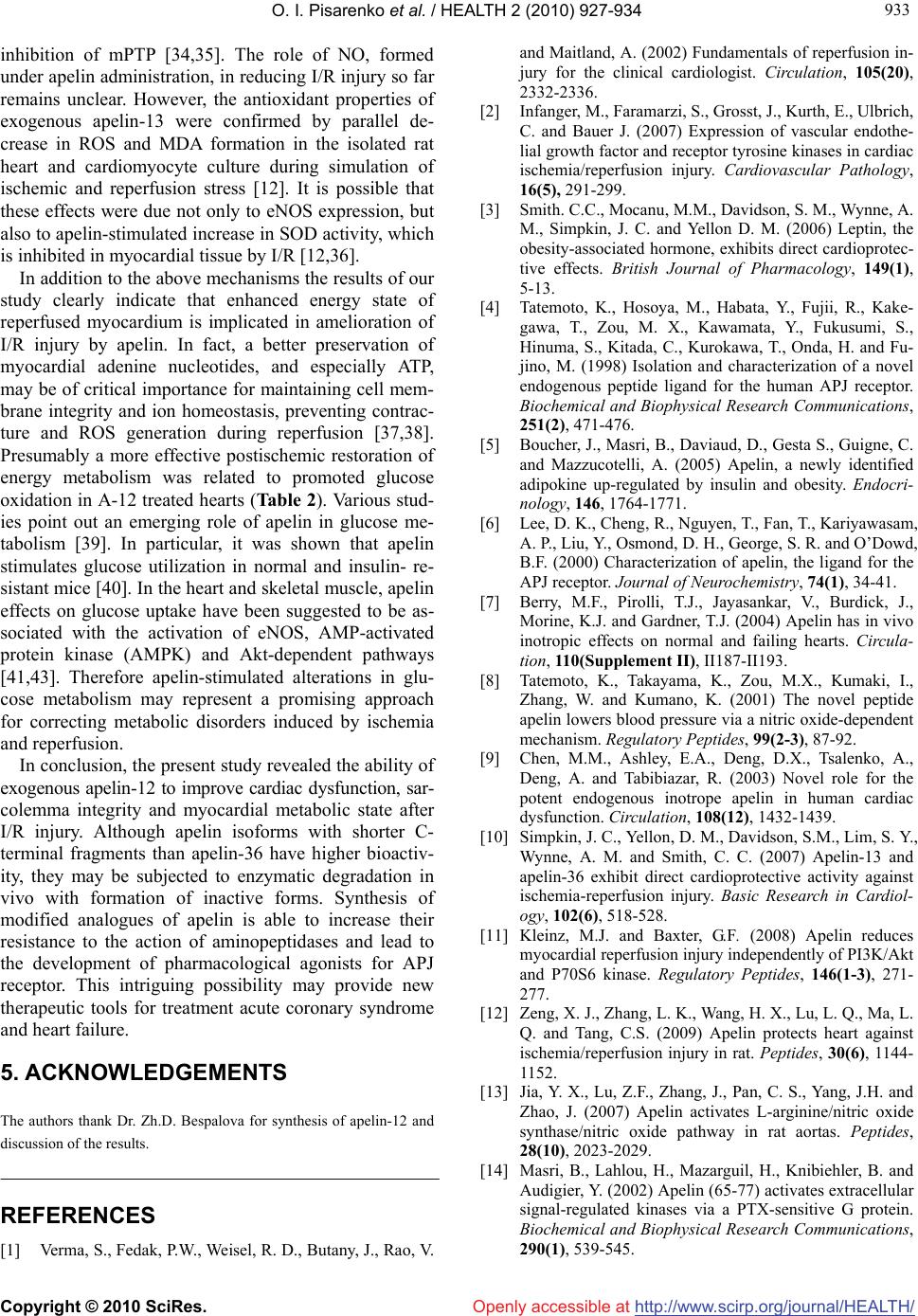

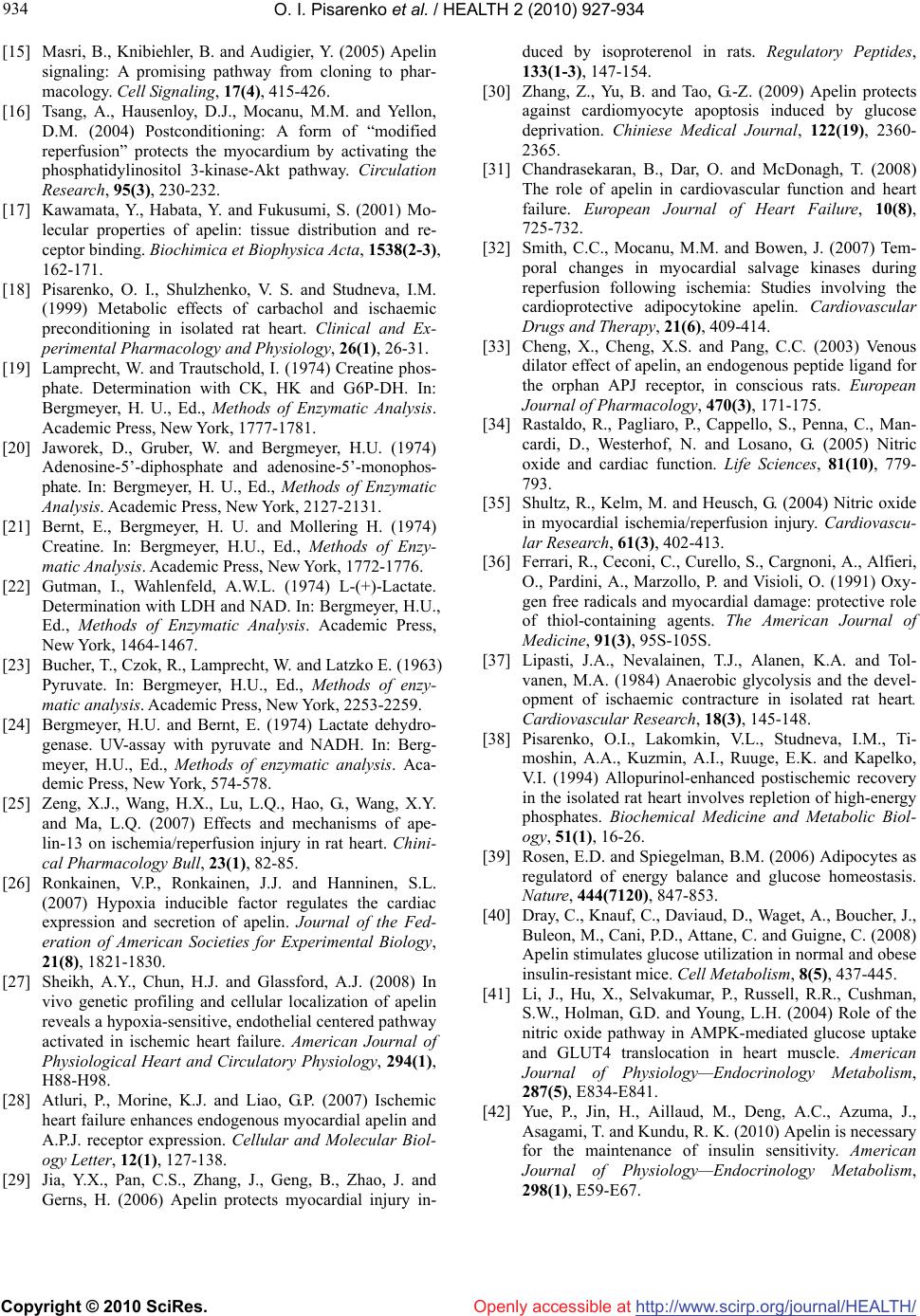

Vol.2, No.8, 927-934 (2010) doi:10.4236/health.2010.28137 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ HEALTH Apelin-12 improves metabolic and functional recovery of rat heart after global ischemia Oleg I. Pisarenko*, Valentin S. Shulzhenko, Yulia A. Pelogeykina, Irina M. Studneva, Denis N. Khatri Russian Cardiology Research-and-Production Complex, Moscow, Russia; *Corresponding Author: olpi@cardio.ru Received 27 March 2010; revised 24 April 2010; accepted 26 April 2010. ABSTRACT This work was designed to explore efficacy of apelin-12 (A-12) as a cardioprotective agent when given before ischemia or at reperfusion using the isolated working heart model. Hearts of male Wistar rats were subjected to 30-min stabilization period followed by 35-min global ischemia and 30-min reperfusion. A short-term infusion of Krebs-Henseleit buffer (KHB) con- taining A-12 (35, 70, 140, 280 or 560 M) was ap- plied prior to ischemia (A-12-I) or at onset of reperfusion (A-12-R). KHB infusion was used as control. A-12 infusions induced a dose-depen- dent increase in recovery of coronary flow, contractile and pump function during reperfu- sion, with the largest augmentation of these indices in the A-12-I group. Both A-12 groups exhibited a significant reduction of LV diastolic pressure rise during reperfusion compared with control. Enhanced functional recovery in the A-12-I group was combined with a decrease in LDH leakage in perfusate on early reperfusion (by 36% vs. control, p < 0.05). Preischemic infu- sion of 140 M A-12 markedly increased myo- cardial ATP content, enhanced preservation of the total adenine nucleotide pool and improved recovery of the energy charge in reperfused hearts. There was a trend towards increase in myocardial phosphocreatine by the end of re- perfusion in the A-12-I group; however this benefit did not reach statistical significance. At the end of reperfusion, myocardial lactate and lactate/pyruvate ratio were on average 5-fold lower in A-12-I treated hearts compared with control ones and did not differ significantly from the initial values. Therefore, improved cardiac dysfunction after I/R injury and less cell mem- brane damage induced by A-12 are associated with maintaining high energy phosphates, par- ticularly ATP, in reperfused myocardium. Changes in energy metabolism may play a role in me- chanisms of cardioprotection afforded by A-12 during I/R stress. Keywords: Apelin-12, Rat Heart; Ischemia/ Reperfusion Injury; Energy Metabolism; Cell Membrane Damage 1. INTRODUCTION Myocardial ischemia and subsequent reperfusion lead to formation of a number of intrinsic factors which mediate the cellular mechanisms of adaptation to altered oxygen and energy supply [1-3]. One of them is adipocytokine apelin, recently isolated from bovine stomach extracts and identified as the endogenous ligand of the human orphan G protein-coupled receptor APJ. Apelin is a 36- amino acid peptide derived from 77-amino acid precur- sor proapelin, for which cDNAs have been cloned from humans, cattle, rats, and mice [4-6]. Apelin and its re- ceptor are widely expressed in mammalian tissues; in the cardiovascular apelin/APJ system was found in the en- dothelial cells of small intramyocardial and pulmonary vessels, in coronary arteries, in endocardial endothelium cells, and in vascular smooth muscle cells [5,7]. Activa- tion of apelin/APJ receptor system triggers cell-signaling mechanisms and induces positive inotropic and hypoten- sive effects in normal and failing myocardium [7-9]. These effects imply an important role of apelin in the regulation of cardiovascular homeostasis, making it an attractive target for heart failure therapy. Only a few studies showed that at least two isoforms of apelin, apelin-13 and the physiologically less potent peptide, apelin-36, are capable to attenuate myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. Thus, administration of either of these peptides reduced infarct size and im- proved contractile function recovery of rat and mouse hearts after regional or global ischemia [10-12]. In cul- tured neonatal cardiomyocytes, apelin-13 decreased for-  O. I. Pisarenko et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 927-934 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 928 mation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and malonic dialdehyde (MDA) with simultaneous augmentation of superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity and reduction of myocardial LDH leakage under hypoxia/reoxygenation treatment [12]. Some authors suggest that vasodilator and antioxidant features of apelin are related to an in- crease in NO formation due to promoted eNOS expres- sion [13]. However, а failure of apelin-13 to influence eNOS phosphorylation was observed in mouse heart subjected to global ischemia and reperfusion [10]. Ape- lin-induced suppression of apoptosis, the delayed open- ing of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) and reduced cardiomyocyte contracture have been demonstrated in various experimental myocardial I/R models, including isolated cardiomyocytes, perfused hearts and hearts in situ [10,12]. One of the possible mechanisms whereby the apelin-APJ system may protect the myocardium form ischemia/reperfusion injury may be its actions on the reperfusion injury salvage kinase (RISK) pathway [14,15]. Abolishment of the protective effects of apelin by PI3K-Akt and ERK specific inhibi- tors suggests the activation of both kinase cascades by apelin [10]. These data, and especially inhibition of mPTP opening [16], indicate an implication of metabolic component in mechanisms of apelin action on ischemic heart. To date, there is no information available regarding direct effects of the apelin/APJ-system on cardiac energy metabolism. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to evaluate alterations in metabolic state of post- ischemic heart occurring after apelin administration be- fore ischemia or at onset of reperfusion. To test the po- tential metabolic importance of apelin, we used a 12 amino acid peptide, apelin-12, which is identical be- tween human and rats and presumably has higher activ- ity than longer C-terminal fragments [17]. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 2.1. Synthesis of Apelin-12 A-12 (chemical structure H-Arg-Pro-Arg-Leu-Ser-His- Lys-Gly-Pro-Met-Pro-Phe-OH, Mw 1422.7) was synthe- sized by the automatic solid phase method using an Ap- plied BioSystems 431A peptide synthesizer (Germany) and Fmoc technology. The synthesized peptide was puri- fied by preparative HPLC and identified by 1H-NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry. 2.2. Heart Perfusion The present investigation conforms to the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institute of Health (NIH publication No. 85-23; revised 1985). Male Wistar rats (280-300 g) were heparinized (500 U i.p.) and anaesthetized with urethane (1.3 g/kg body weight). Hearts (1.4-1.5 g wet wt) were excised and immediately placed into ice-cold Krebs- Henseleit bicarbonate buffer (KHB) until contraction stopped. The aorta was then cannulated and Langendorff perfusion was performed at a constant pressure equiva- lent to 75 cm H2O for 15 min. Working perfusion was performed according to a modified method of Neely under constant left atrium pressure and aortic pressure (AP) of 20 and 100 cm H2O, respectively. KHB containing (in mM): NaCl 118; KCl 4.7; CaCl2 3.0; Na2EDTA 0.5; KH2PO4 1.2; MgSO4 1.2; NaHCO3 25.0; glucose 11.0. was oxygenated with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2; pH was 7.4 ± 0.1 at 37˚C; it was passed through a 5 m Millipore filter (Bedford, MA, USA) before use. A nee- dle was inserted into the left ventricular cavity to regis- tered LV pressure via a Gould Statham P50 transducer, SP 1405 monitor and a Gould Brush SP 2010 recorder (Gould, Oxnard, Ca, USA). The contractile function index was calculated as the LV developed pressure-heart rate product (LVDPxHR), where LVDP is the difference between LV systolic and LV end-diastolic pressure. Car- diac pump function was assessed by minute volume and aortic output; stroke was calculated as cardiac output/ HR. Coronary resistance was calculated as AP/coronary flow [18]. 2.3. Experimental Protocol After preliminary Langendorff perfusion, the hearts were perfused in working mode for 20 min; the steady state values of cardiac function were recorded at the end of this period. Then, the hearts were randomly assigned onto one of three groups: 1) control (n = 13); 2) A-12 treated before global ischemia (A-12-I, n = 13); 3) A-12 treated at onset of reperfusion (A-12-R, n = 13). After the steady state period, the control hearts were perfused in Langendorff mode for 5 min at a constant flow rate of 4 ml/min and then they were subjected to 35-min nor- mothermic global ischemia followed by 5-min Langen- dorff perfusion with subsequent 30-min working reper- fusion. In the A-12-I group, 5-min Langendorff perfu- sion at a constant flow rate of 4 ml/min with KHB con- taining A-12 (35, 70, 140, 280 or 560 M) was applied prior to global ischemia. The hearts of the A-12-R group were perfused with KHB containing A-12 in the same mode after global ischemia. After preliminary working perfusion (steady state) and at the end of reperfusion, the hearts were freeze-clamped in liquid nitrogen for me- tabolite analysis. The myocardial effluent was collected in ice-cold containers during both periods of Langen- dorff perfusion for immediate measurement of LDH activity. The total number of hearts used for functional and metabolic determinations was 49.  O. I. Pisarenko et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 927-934 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 929 929 2.4. Tissue Sampling, Metabolite Analysis and Assay of LDH Activity. Frozen tissue was quickly homogenized in cooled 6% perchloric acid (10 ml/g) using an Ultra-Turrax T-25 homogenizer (IKA-Labortechnik, Staufen, Germany), and the homogenates were centrifuged at 2500 g for 10 min at 4ºC. The supernatants were then neutralized with 5 M K2CO3 to pH 7.4 and the extracts were centrifuged after cooling to remove KClO4 precipitate. Tissue dry weights were determined by weighing a portion of the pellets after extraction with perchloric acid and drying over- night at 110ºC. Concentrations of ATP, ADP, AMP, phosphocreatine and lactate in neutralized tissue extracts were determined specrtophotometrically by enzymatic methods [19-22]. A modified UV-spectroscopy method was used to assay tissue extracts for pyruvate [23]. De- termination of metabolite in each tissue extract was per- formed three times to calculate the average metabolite concentration in a sample. LDH activity in the myocar- dial effluent was measured according to the method of Bergmeyer and Bernt [24] using pyruvate as substrate. Determination of LDH activity in the perfusate was re- peated twice in each sample. Enzymes and chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO USA). Solutions were prepared using deionized water (Milli Ro-4; Milli-Q, Millipore Corp. Bedford, MA, USA). 2.5. Statistical Analysis Statistical differences between more than two groups were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (AN- OVA) and followed by Scheffe F-test. Comparisons be- tween two groups involved use of the Student’s t test. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. 3. RESULTS 3.1. Postischemic Recovery of Cardiac Function Administration of A-12 before global ischemia or at on- set of reperfusion enhanced recovery of cardiac pump function during reperfusion. As an example, a dose- dependent increase in recovery of cardiac output (CO) by the end of reperfusion is shown on Figure 1(a). The significant increase in CO recovery was observed after pre- or postischemic infusion of 70 M A-12 as com- pared with the control. The differences between CO re- covery in the experimental groups and control became more pronounced with an increase in A-12 concentration in KHB. The maximal response to A-12 was observed at the concentration of 280 M; at higher concentrations a dose-effect curve reached a plateau. Within the range of 70-560 M, the peptide administration prior to ischemia was more effective than after it. Thus, the maximal res- toration of CO after infusion 560 M A-12 were 86 ± 9% and 59 ± 6% of the steady state value in the group A-12-I and A-12-R, correspondingly, in comparison with 32 ± 2% in the control (P < 0.02-0.01). А similar dose- dependent effects were obtained for recovery of the LVDPxHR product during reperfusion in both experimen- tal groups (Figure 1(b)). Recovery of cardiac and coronary function indices at the end of reperfusion after administration of 140 M A -12 before and after of ischemia is presented in Table 1. In addition to CO, aortic output and stroke volume were also significantly higher in the A-12-I group than in the A-12-R group and in control. The especially greater dif- ferences between the groups were noted for aortic output: in the A-12-I group its recovery was twice more effec- tive than in the A-12-R group and 30 times higher than in control. An enhanced recovery of cardiac pump func- tion in A-12 treated hearts was accompanied by an aug- mented restoration of the LVDPxHR product. This effect was due to higher recovery of HR and in both A-12 groups comparing with control. A significant increase in the values of LVDP was in turn caused by a marked re- duction of LV diastolic pressure during reperfusion (Figure 2). Beneficial effects of A-12 on cardiac func- tion were accompanied by the peptide influence on the coronary system. Thus, both of A-12 groups exhibited a significant increase in coronary flow with concomitant reduction in coronary resistance in comparison with control (Table 1) indicating a participation of coronary vessels in response to A-12 administration. 3.2. The Energy State of Reperfused Hearts Changes in the myocardial content of adenine nucleo- tides and the end products of anaerobic glycolysis, lac- tate and pyruvate, at the end of reperfusion caused by preischemic infusion of 140 M A-12 are compared with the initial myocardial levels of these metabolites in Ta- ble 2. By the end of reperfusion, the control group showed a profound decrease in the ATP content (to 37 ± 7% of the initial value) with a simultaneous increase in ADP and AMP levels (on the average 1.7 and 5.6 times, respectively). These changes indicated the preferred degradation of adenine nucleotides, whose total myocar- dial pool (AN = ATP + ADP + AMP) was lowered to 58 ± 3% of the steady state value. The lactate and pyru- vate contents were, correspondingly, 5- and 1.3-fold higher than the normal values, thus indicating an inhibi- tion of glucose oxidation during reperfusion. Admini- stration of 140 M A-12 before ischemia enhanced ATP preservation by 60 ± 3% and twice decreased AMP con- tent in the reperfused hearts. As a result the myocardial AN pool was preserved considerably better than in the  O. I. Pisarenko et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 927-934 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 930 control and composed 81 ± 6% of the steady state value. Redistribution in the adenine nucleotide content consid- erably increased the total energy charge (EC = (ATP + 0.5ADP)/ATP + ADP + AMP) in the A-12-I group as compared with the control. The observed improvement in the energy state of reperfused hearts was combined with а decrease in myocardial lactate content to the steady state value (Table 2). Although the myocardial pyruvate level in the A-12-I group remained raised at the end of reperfusion, the lactate/pyruvate ratio was 5 times lower than in the control and did not differ significantly from the steady state value. Preischemic administration of 140 M A-12 did not significantly enhance recovery of phosphocreatine (PCr): by the end of reperfusion its myocardial content was 14.95 ± 1.32 mol/g of dry wt vs. 12.02 ± 2.61 mol/g of dry wt in the control. The total creatine pool (Cr = PCr + creatine) in A-12-treated hearts did not differ sig- Table 1. Effects of apelin-12 administration before or after global ischemia on functional recovery of isolated rat at the end of reper- fusion. Steady state (n = 39) Control (n = 13) A-12-R (n = 13) А-12-I (n = 13) Coronary flow, ml/min 19.1 ± 2.0 14.5 ± 0.4 15.9 ± 1.1 17.8 ± 0.9 a Perfusion pressure, mm Hg 64 ± 6 60 ± 1 61 ± 1 63 ± 1 a Coronary resistance, mm Hg/ml 3.46 ± 0.04 4.19 ± 0.07 3.98 ± 0.21 3.78 ± 0.17 a LV systolic pressure, mm Hg 102 ± 1 70 ± 1 80 ± 3 a 92 ± 3 a b LV diastolic pressure, mm Hg -2 ± 1 8 ± 1 5 ± 1 a 1 ± 1 a b LV developed pressure, mm Hg 106 ± 1 62 ± 1 75 ± 4 a 92 ± 4 a b Heart rate, beat/min 310 ± 2 242 ± 3 264 ± 6 a 288 ± 6 a b LVDP x HR, mm Hg/min 33062 ± 624 14877 ± 561 20167 ± 1653 a 26780 ± 1653 a b Aortic output, ml/min 28.1 ± 3.0 0.6 ± 0.3 8.7 ± 0.8 a 19.1 ± 1.3 a b Cardiac output, ml 46.2 ± 1.1 14.8 ± 0.9 24.0 ± 2.3 a 35.5 ± 2.2 a b Stroke volume, l 149 ± 1 61 + 3 91 + 7 a 127 + 4 a b The hearts were perfused as indicated in Materials and methods. Steady state, 20-min preliminary working perfusion; Control, 5-min Langendorff perfusion + 35-min global ischemia + 5-min Langendorff perfusion + 30-min working reperfusion; A-12-R, 5-min Langendorff perfusion with 140 M A-12 after global ischemia; A-12-I, 5-min Langendorff perfusion with 140 M A-12 before global ischemia. Data are the mean ± SEM. a p < 0.05 vs. control group; b p < 0.05 vs. A-12-R group. Table 2 Effects of 140 M apelin-12 infusion before global ischemia on myocardial content of metabolites and indices of myocar- dial energy state at the end of reperfusion. Steady state Control А-12-I АTP 22.42 ± 2.06 8.30 ± 1.73 а 13.11 ±0.69 а b АDP 2.80 ± 0.12 4.86 ± 0.28 а 5.90 ± 0.28 а АMP 0.71 ± 0.01 3.97 ± 0.74а 1.92 ± 0.06 а b АN 25.93 ± 1.45 17.13 ± 1.42 а 20.94 ± 0.92 а b AT P/ АDP 8.00 + 0.10 1.72 ± 0.35 а 2.23 ±0.07 а EC 0.91 ± 0.02 0.60 ± 0.06 а 0.77 ± 0.01 а b Lactate 1.72 ± 0.19 10.48 ± 3.08а 2.12 ± 0.48 b Pyruvate 0.18 ± 0.02 0.23 ± 0.03 0.22 ± 0.02 Lactate/Pyruvate 9.55 ± 0.98 45.56 ± 7.34 а 9.64 ± 1.25 b Steady state, 20-min preliminary working perfusion; Control, 5-min Langendorff perfusion + 35-min global ischemia + 5-min Langendorff perfusion + 30-min working reperfusion; A-12-I, 5-min Langendorff perfusion with 140 M A-12 before global ischemia. Data are the mean ± SEM for 10 experiments. Metabolite contents are expressed in (mol/g dry wt). a p < 0.05 vs. steady state; b p < 0.05 vs. control. АN = ATP + ADP + AMP. The energy charge (EC) = (ATP + 0.5ADP)ATP + ADP + AMP.  O. I. Pisarenko et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 927-934 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 931 931 Openly accessible at nificantly from this index in the control and in the steady state being 59.65 ± 1 56, 56.65 ± 3.89 and 59.26 ± 1.87 mol/g of dry wt, correspondently. 3.3. Lactate Dehydrogenase Leakage The ability of A-12 to influence cell membrane damage was assessed by changes in LDH release into the myocar- dial effluent before and after global ischemia (Table 3). For the 5-min period of 140 M A-12 infusion prior to ischemia, LDH leakage did not differ significantly from that one in control. Therefore A-12 administration did cause damage to the sarcolemma of nonischemic car- diomyocytes. During the 5-min period after ischemia, the release of LDH activity in the perfusate of the con- trol group was increased on average 2.6 times compared with this value before ischemia indicating I/R membrane damage. However in the A-12-I group, the postischemic LDH leakage was reduced by 40% compared with con- trol. This finding suggested fewer membrane defects determining a release of cytoplasmic LDH from the myocardium. 4. DISCUSSION The present study demonstrates, for the first time, car- dioprotective properties of exogenous A-12 in isolated working rat heart subjected to global ischemia and re- perfusion. They are manifested by enhanced contractile and pump function recovery and a better restoration of coronary flow, which are more effective after the peptide administration before ischemia than at onset of reperfu- sion. (Figure 1, Table 1). The оbtained data are in broad agreement with the previous observations demonstrating a reduction of ischemia-reperfusion injury induced by exogenous apelin-13, Pyr1-apelin-13 and apelin-36 in Langendorff perfused mouse and rat hearts [10-12,25]. It is essential that a higher functional level of postischemic hearts protected by A-12 in our experiences is combined with augmented metabolic state. Probably this beneficial effect is associated with enhanced oxidation of glucose, the main energy substrate of isolated perfused hearts. Indeed, A-12 treated hearts exhibit substantially reduced lactate/pyruvate ratio as compared with control and the normal myocardial lactate content at the end of reperfu- sion. In parallel, A-12 administration exerts an energy conservation effect evidenced by higher myocardial ATP and AN contents and enhanced EC of postischemic cardiomyocytes. In addition, augmentation of energy state of postischemic hearts by pretreatment with 140 M A-12 is accompanied by less cell membrane damage on early reperfusion (Тable 3). Taken together, these findings indicate that alterations in myocardial metabo- lism induced by apelin may play a role in improving cardiac dysfunction after ischemia and reperfusion stress. Table 3. Effects of 140 M apelin-12 infusion on LDH leakage before and after global ischemia. Before ischemia After ischemia Control (n = 6) 28.60 ± 3.01 73.64 ± 5.06 б А-12-I (n = 7) 24.28 ± 2.73 53.56 ± 6.52 а b Control, 5-min Langendorff perfusion + 35-min global ischemia + 5-min Langendorff perfusion + 30-min working reperfusion; A-12-I, 5-min infusion of 140 M A-12 before global ischemia. Values are the means + SEM and are expressed in IU/g dry wt. for 5-min Langendorff perfusion before or after global ischemia. a p<0.05 vs. control group; b p < 0.05 vs. the value before ischemia. 20 40 60 80 100 35 70 140 280 560 Cardiac output, % of initial 1 2 3 40 60 80 100 35 70 140 280 560 3 2 1 Apelin-12, M Apelin-12, M LVDP x HR, % of initial A B * * ** * ** # ## * * * * ** * ** # ## Figure 1. Effects of A-12 concentration in KHB on recovery of minute volume (A) and the LVDP-HR product (B) at the end of reperfusion. 1) 5-min Langendorff perfusion + 35-min global ischemia + 5-min Langendorff perfusion + 30-min working reperfusion (control); 2) 5-min Langendorff perfu- sion with A-12 after global ischemia (A-12-R); 3) 5-min Langendorff perfusion with A-12 before global ischemia (A-12-I). Data are the mean + SEM for 12-15 experiments. * p < 0.05 vs. control; # p < 0.05 vs. A-12-R.  O. I. Pisarenko et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 927-934 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 932 Openly accessible at 0104050607080 -4 0 4 8 12 16 Time, min LV diastolic pressure, mm Hg 1 3 2 Ischemia Reperfusion * ** * ** # # # Figure 2. Effects of A-12 administration before or after global ischemia on recovery of LV diastolic pressure during reperfusion. 1) 5-min Langendorff perfusion + 35-min global ischemia + 5-min Langendorff perfusion + 30-min working reperfusion (control); 2) 5-min Langendorff perfu- sion with 140 M A-12 after global ischemia (A-12-R); 3) 5-min Langendorff perfusion with 140 M A-12 before global ischemia (A-12-I). Data are the mean+ SEM for 12-15 experiments. * p < 0.05 vs. control; # p < 0.05 vs. A-12-R. The current studies evaluating the mechanisms wh- ereby apelin confer protection against I/R injury have yielded mixed results. Wide discrepancy relates to varia- tions in apelin/APJ expression. In ventricular cardiomyo- cytes isolated from rats, apelin expression is increased under hypoxia presumably via hypoxia-inducible fac- tor-mediated pathway [12,26]. Apelin and APJ are up- regulated in the heart and skeletal muscle following myocardial injury in the murine model of LAD occlu- sion in vivo [27]. Accordingly, endogenous myocardial apelin and APJ expression are increased in failing rat hearts in compensation for ischemic cardiomyopathy [28]. In contrast, apelin content in plasma, atrial and ventricular myocardium and APJ gene expression de- crease in myocardial injury induced by repeated isopro- terenol injections in rats [29]. The endogenous apelin/ APJ system is compensatory up-regulated and ultimately down-regulated during sustained myocardial ischemia in vitro which was mimicked by glucose deprivation [30]. In isolated rat heart, apelin and APJ mRNA are up- regulated during ischemia but return to the control levels following reperfusion [11]. Based on these conflicting data we suggest that in acute ischemic myocardial injury, the endogenous apelin/APJ system may have a protec- tive role. However the endogenous apelin production is insufficient for activation of the APJ receptors to reduce myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. This assumption is consistent with cardioprotective activity of exogenous isoforms of apelin revealed in different experimental models [7,10-12,28-30]. Effects of exogenous apelin are mediated partly by ac- tivation of components of the reperfusion injury salvage kinase (RISK) pathway, phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase (PI3K)/Akt, p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) extracellular signal-regulated MAPK (ERK1/2) [10,14,16,31]. This is confirmed by that fact that the inhibitors of PI3K-Akt and p44/42 phosphorylation, LY294002 and UO126, respectively, abolished reduction of infarct size induced by apelin-13 in vitro [10]. Simi- larly, addition of wortmannin and PD098059, the inhibi- tors of PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2, to culture medium during hypoxia/reoxygenation, suppressed cardiomyocyte vi- ability provided by apelin-13 [12]. Further evidence that apelin may act via activation of the RISK pathway was obtained from the findings concerning the mPTP open- ing, which causes the energy collapse and irreversible cardiomyocyte damage [16,32]. Thus, while apelin-13 delayed the times until mitochondrial membrane depo- larization and rigor contracture, LY294002 and mitogen- activated protein kinase (MEK) inhibitor 1 blocked these effects [10]. Anti-apoptotic effects of apelin-13 in glu- cose-deprived cardiomyocytes involve activation of the PI3K/Akt and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways [30]. As follows from the study by Kleinz and Baxter [11], the RISK cascades are not al- ways used for myocardial protection afforded by apelin. These authors showed that apelin-13 administered dur- ing reperfusion significantly reduced infarct size in rat hearts subjected to coronary occlusion followed by re- perfusion. However this protective effect was not abol- ished by co-administration of the PI3K/Akt inhibitor wortmannin or the P70S6 kinase inhibitor rapamycin. Therefore, apelin may exhibit cardioprotection using al- ternative mediators and signaling pathways. Elevation of eNOS expression induced by apelin [8, 12] may lead to increase in NO formation, contributing to recovery of cardiac function and metabolism after ischemia. In our study, it is indirectly confirmed by sig- nificant improvement of coronary flow in the A-12-I group during reperfusion (Table 1). Involvement of the L-Arg/NOS/NO pathway in vascular function regulation by apelin was noted earlier Tatemoto et al. [4]. They demonstrated that in anaesthetized rats the hypotensive effect of apelin-12 (to a greater extent than apelin-13 and apelin-36) is accompanied by an increase in the total ni- trite and nitrate in plasma, and is abrogated in the pres- ence of N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), a NOS inhibitor. Subsequently, a dose-dependent reduc- tion of the mean arterial pressure during apelin infusion was documented in conscious rats [33]. It is equally im- portant that during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion, NO generated by vascular and endocardial endothelial NOS may attenuate oxidative stress by scavenging reac- tive oxygen species (ROS) and reduce cell death via  O. I. Pisarenko et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 927-934 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 933 933 Openly accessible at inhibition of mPTP [34,35]. The role of NO, formed under apelin administration, in reducing I/R injury so far remains unclear. However, the antioxidant properties of exogenous apelin-13 were confirmed by parallel de- crease in ROS and MDA formation in the isolated rat heart and cardiomyocyte culture during simulation of ischemic and reperfusion stress [12]. It is possible that these effects were due not only to eNOS expression, but also to apelin-stimulated increase in SOD activity, which is inhibited in myocardial tissue by I/R [12,36]. In addition to the above mechanisms the results of our study clearly indicate that enhanced energy state of reperfused myocardium is implicated in amelioration of I/R injury by apelin. In fact, a better preservation of myocardial adenine nucleotides, and especially ATP, may be of critical importance for maintaining cell mem- brane integrity and ion homeostasis, preventing contrac- ture and ROS generation during reperfusion [37,38]. Presumably a more effective postischemic restoration of energy metabolism was related to promoted glucose oxidation in A-12 treated hearts (Table 2). Various stud- ies point out an emerging role of apelin in glucose me- tabolism [39]. In particular, it was shown that apelin stimulates glucose utilization in normal and insulin- re- sistant mice [40]. In the heart and skeletal muscle, apelin effects on glucose uptake have been suggested to be as- sociated with the activation of eNOS, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and Akt-dependent pathways [41,43]. Therefore apelin-stimulated alterations in glu- cose metabolism may represent a promising approach for correcting metabolic disorders induced by ischemia and reperfusion. In conclusion, the present study revealed the ability of exogenous apelin-12 to improve cardiac dysfunction, sar- colemma integrity and myocardial metabolic state after I/R injury. Although apelin isoforms with shorter C- terminal fragments than apelin-36 have higher bioactiv- ity, they may be subjected to enzymatic degradation in vivo with formation of inactive forms. Synthesis of modified analogues of apelin is able to increase their resistance to the action of aminopeptidases and lead to the development of pharmacological agonists for APJ receptor. This intriguing possibility may provide new therapeutic tools for treatment acute coronary syndrome and heart failure. 5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors thank Dr. Zh.D. Bespalova for synthesis of apelin-12 and discussion of the results. REFERENCES [1] Verma, S., Fedak, P.W., Weisel, R. D., Butany, J., Rao, V. and Maitland, A. (2002) Fundamentals of reperfusion in- jury for the clinical cardiologist. Circulation, 105(20), 2332-2336. [2] Infanger, M., Faramarzi, S., Grosst, J., Kurth, E., Ulbrich, C. and Bauer J. (2007) Expression of vascular endothe- lial growth factor and receptor tyrosine kinases in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cardiovascular Pathology, 16(5), 291-299. [3] Smith. C.C., Mocanu, M.M., Davidson, S. M., Wynne, A. M., Simpkin, J. C. and Yellon D. M. (2006) Leptin, the obesity-associated hormone, exhibits direct cardioprotec- tive effects. British Journal of Pharmacology, 149(1), 5-13. [4] Tatemoto, K., Hosoya, M., Habata, Y., Fujii, R., Kake- gawa, T., Zou, M. X., Kawamata, Y., Fukusumi, S., Hinuma, S., Kitada, C., Kurokawa, T., Onda, H. and Fu- jino, M. (1998) Isolation and characterization of a novel endogenous peptide ligand for the human APJ receptor. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 251(2), 471-476. [5] Boucher, J., Masri, B., Daviaud, D., Gesta S., Guigne, C. and Mazzucotelli, A. (2005) Apelin, a newly identified adipokine up-regulated by insulin and obesity. Endocri- nology, 146, 1764-1771. [6] Lee, D. K., Cheng, R., Nguyen, T., Fan, T., Kariyawasam, A. P., Liu, Y., Osmond, D. H., George, S. R. and O’Dowd, B.F. (2000) Characterization of apelin, the ligand for the APJ receptor. Journal of Neurochemistry, 74(1), 34-41. [7] Berry, M.F., Pirolli, T.J., Jayasankar, V., Burdick, J., Morine, K.J. and Gardner, T.J. (2004) Apelin has in vivo inotropic effects on normal and failing hearts. Circula- tion, 110(Supplement II), II187-II193. [8] Tatemoto, K., Takayama, K., Zou, M.X., Kumaki, I., Zhang, W. and Kumano, K. (2001) The novel peptide apelin lowers blood pressure via a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Regulatory Peptides, 99(2-3), 87-92. [9] Chen, M.M., Ashley, E.A., Deng, D.X., Tsalenko, A., Deng, A. and Tabibiazar, R. (2003) Novel role for the potent endogenous inotrope apelin in human cardiac dysfunction. Circulation, 108(12), 1432-1439. [10] Simpkin, J. C., Yellon, D. M., Davidson, S.M., Lim, S. Y., Wynne, A. M. and Smith, C. C. (2007) Apelin-13 and apelin-36 exhibit direct cardioprotective activity against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Basic Research in Cardiol- ogy, 102(6), 518-528. [11] Kleinz, M.J. and Baxter, G.F. (2008) Apelin reduces myocardial reperfusion injury independently of PI3K/Akt and P70S6 kinase. Regulatory Peptides, 146(1-3), 271- 277. [12] Zeng, X. J., Zhang, L. K., Wang, H. X., Lu, L. Q., Ma, L. Q. and Tang, C.S. (2009) Apelin protects heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat. Peptides, 30(6), 1144- 1152. [13] Jia, Y. X., Lu, Z.F., Zhang, J., Pan, C. S., Yang, J.H. and Zhao, J. (2007) Apelin activates L-arginine/nitric oxide synthase/nitric oxide pathway in rat aortas. Peptides, 28(10), 2023-2029. [14] Masri, B., Lahlou, H., Mazarguil, H., Knibiehler, B. and Audigier, Y. (2002) Apelin (65-77) activates extracellular signal-regulated kinases via a PTX-sensitive G protein. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 290(1), 539-545.  O. I. Pisarenko et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 927-934 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 934 [15] Masri, B., Knibiehler, B. and Audigier, Y. (2005) Apelin signaling: A promising pathway from cloning to phar- macology. Cell Signaling, 17(4), 415-426. [16] Tsang, A., Hausenloy, D.J., Mocanu, M.M. and Yellon, D.M. (2004) Postconditioning: A form of “modified reperfusion” protects the myocardium by activating the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt pathway. Circulation Research, 95(3), 230-232. [17] Kawamata, Y., Habata, Y. and Fukusumi, S. (2001) Mo- lecular properties of apelin: tissue distribution and re- ceptor binding. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1538(2-3), 162-171. [18] Pisarenko, O. I., Shulzhenko, V. S. and Studneva, I.M. (1999) Metabolic effects of carbachol and ischaemic preconditioning in isolated rat heart. Clinical and Ex- perimental Pharmacology and Physiology, 26(1), 26-31. [19] Lamprecht, W. and Trautschold, I. (1974) Creatine phos- phate. Determination with CK, HK and G6P-DH. In: Bergmeyer, H. U., Ed., Methods of Enzymatic Analysis. Academic Press, New York, 1777-1781. [20] Jaworek, D., Gruber, W. and Bergmeyer, H.U. (1974) Adenosine-5’-diphosphate and adenosine-5’-monophos- phate. In: Bergmeyer, H. U., Ed., Methods of Enzymatic Analysis. Academic Press, New York, 2127-2131. [21] Bernt, E., Bergmeyer, H. U. and Mollering H. (1974) Creatine. In: Bergmeyer, H.U., Ed., Methods of Enzy- matic Analysis. Academic Press, New York, 1772-1776. [22] Gutman, I., Wahlenfeld, A.W.L. (1974) L-(+)-Lactate. Determination with LDH and NAD. In: Bergmeyer, H.U., Ed., Methods of Enzymatic Analysis. Academic Press, New York, 1464-1467. [23] Bucher, T., Czok, R., Lamprecht, W. and Latzko E. (1963) Pyruvate. In: Bergmeyer, H.U., Ed., Methods of enzy- matic analysis. Academic Press, New York, 2253-2259. [24] Bergmeyer, H.U. and Bernt, E. (1974) Lactate dehydro- genase. UV-assay with pyruvate and NADH. In: Berg- meyer, H.U., Ed., Methods of enzymatic analysis. Aca- demic Press, New York, 574-578. [25] Zeng, X.J., Wang, H.X., Lu, L.Q., Hao, G., Wang, X.Y. and Ma, L.Q. (2007) Effects and mechanisms of ape- lin-13 on ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat heart. Chini- cal Pharmacology Bull, 23(1), 82-85. [26] Ronkainen, V.P., Ronkainen, J.J. and Hanninen, S.L. (2007) Hypoxia inducible factor regulates the cardiac expression and secretion of apelin. Journal of the Fed- eration of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 21(8), 1821-1830. [27] Sheikh, A.Y., Chun, H.J. and Glassford, A.J. (2008) In vivo genetic profiling and cellular localization of apelin reveals a hypoxia-sensitive, endothelial centered pathway activated in ischemic heart failure. American Journal of Physiological Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 294(1), H88-H98. [28] Atluri, P., Morine, K.J. and Liao, G.P. (2007) Ischemic heart failure enhances endogenous myocardial apelin and A.P.J. receptor expression. Cellular and Molecular Biol- ogy Letter, 12(1), 127-138. [29] Jia, Y.X., Pan, C.S., Zhang, J., Geng, B., Zhao, J. and Gerns, H. (2006) Apelin protects myocardial injury in- duced by isoproterenol in rats. Regulatory Peptides, 133(1-3), 147-154. [30] Zhang, Z., Yu, B. and Tao, G.-Z. (2009) Apelin protects against cardiomyocyte apoptosis induced by glucose deprivation. Chiniese Medical Journal, 122(19), 2360- 2365. [31] Chandrasekaran, B., Dar, O. and McDonagh, T. (2008) The role of apelin in cardiovascular function and heart failure. European Journal of Heart Failure, 10(8), 725-732. [32] Smith, C.C., Mocanu, M.M. and Bowen, J. (2007) Tem- poral changes in myocardial salvage kinases during reperfusion following ischemia: Studies involving the cardioprotective adipocytokine apelin. Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapy, 21(6), 409-414. [33] Сheng, X., Cheng, X.S. and Pang, C.C. (2003) Venous dilator effect of apelin, an endogenous peptide ligand for the orphan APJ receptor, in conscious rats. European Journal of Pharmacology, 470(3), 171-175. [34] Rastaldo, R., Pagliaro, P., Cappello, S., Penna, C., Man- cardi, D., Westerhof, N. and Losano, G. (2005) Nitric oxide and cardiac function. Life Sciences, 81(10), 779- 793. [35] Shultz, R., Kelm, M. and Heusch, G. (2004) Nitric oxide in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cardiovascu- lar Research, 61(3), 402-413. [36] Ferrari, R., Ceconi, C., Curello, S., Cargnoni, A., Alfieri, O., Pardini, A., Marzollo, P. and Visioli, O. (1991) Oxy- gen free radicals and myocardial damage: protective role of thiol-containing agents. The American Journal of Medicine, 91(3), 95S-105S. [37] Lipasti, J.A., Nevalainen, T.J., Alanen, K.A. and Tol- vanen, M.A. (1984) Anaerobic glycolysis and the devel- opment of ischaemic contracture in isolated rat heart. Cardiovascular Research, 18(3), 145-148. [38] Pisarenko, O.I., Lakomkin, V.L., Studneva, I.M., Ti- moshin, A.A., Kuzmin, A.I., Ruuge, E.K. and Kapelko, V.I. (1994) Allopurinol-enhanced postischemic recovery in the isolated rat heart involves repletion of high-energy phosphates. Biochemical Medicine and Metabolic Biol- ogy, 51(1), 16-26. [39] Rosen, E.D. and Spiegelman, B.M. (2006) Adipocytes as regulatord of energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Nature, 444(7120), 847-853. [40] Dray, C., Knauf, C., Daviaud, D., Waget, A., Boucher, J., Buleon, M., Cani, P.D., Attane, C. and Guigne, C. (2008) Apelin stimulates glucose utilization in normal and obese insulin-resistant mice. Cell Metabolism, 8(5), 437-445. [41] Li, J., Hu, X., Selvakumar, P., Russell, R.R., Cushman, S.W., Holman, G.D. and Young, L.H. (2004) Role of the nitric oxide pathway in AMPK-mediated glucose uptake and GLUT4 translocation in heart muscle. American Journal of Physiology—Endocrinology Metabolism, 287(5), E834-E841. [42] Yue, P., Jin, H., Aillaud, M., Deng, A.C., Azuma, J., Asagami, T. and Kundu, R. K. (2010) Apelin is necessary for the maintenance of insulin sensitivity. American Journal of Physiology—Endocrinology Metabolism, 298(1), E59-E67. |