Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

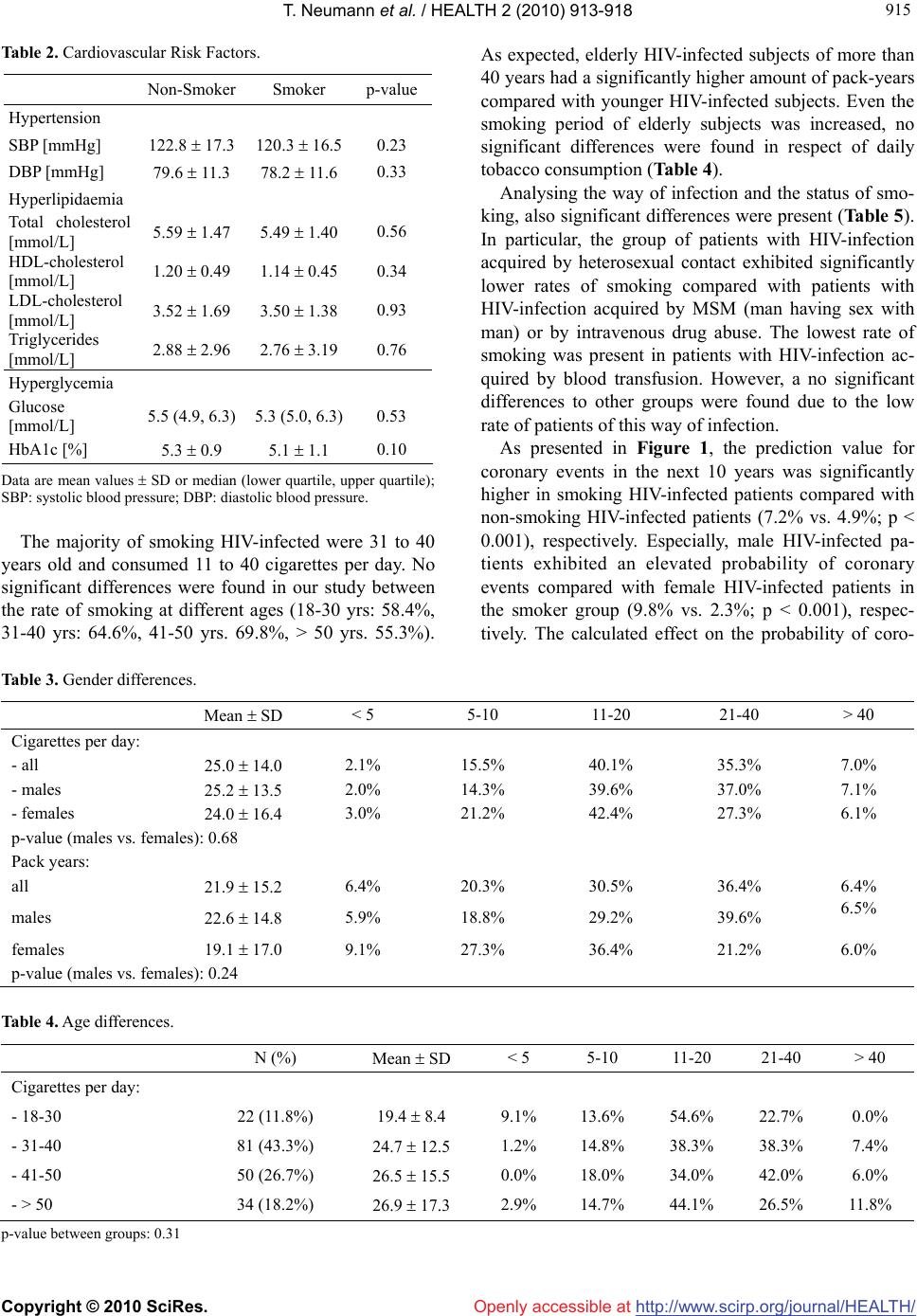

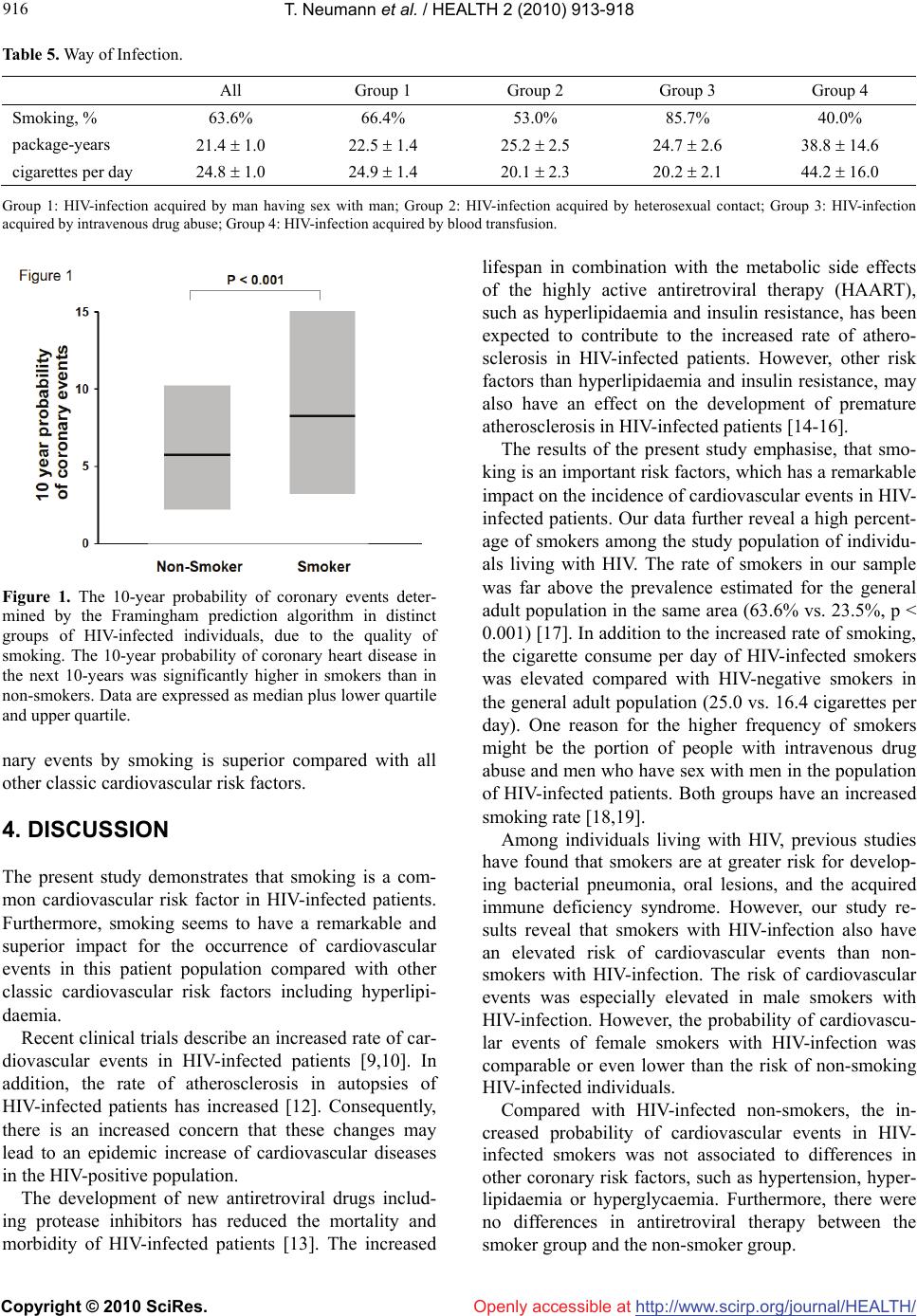

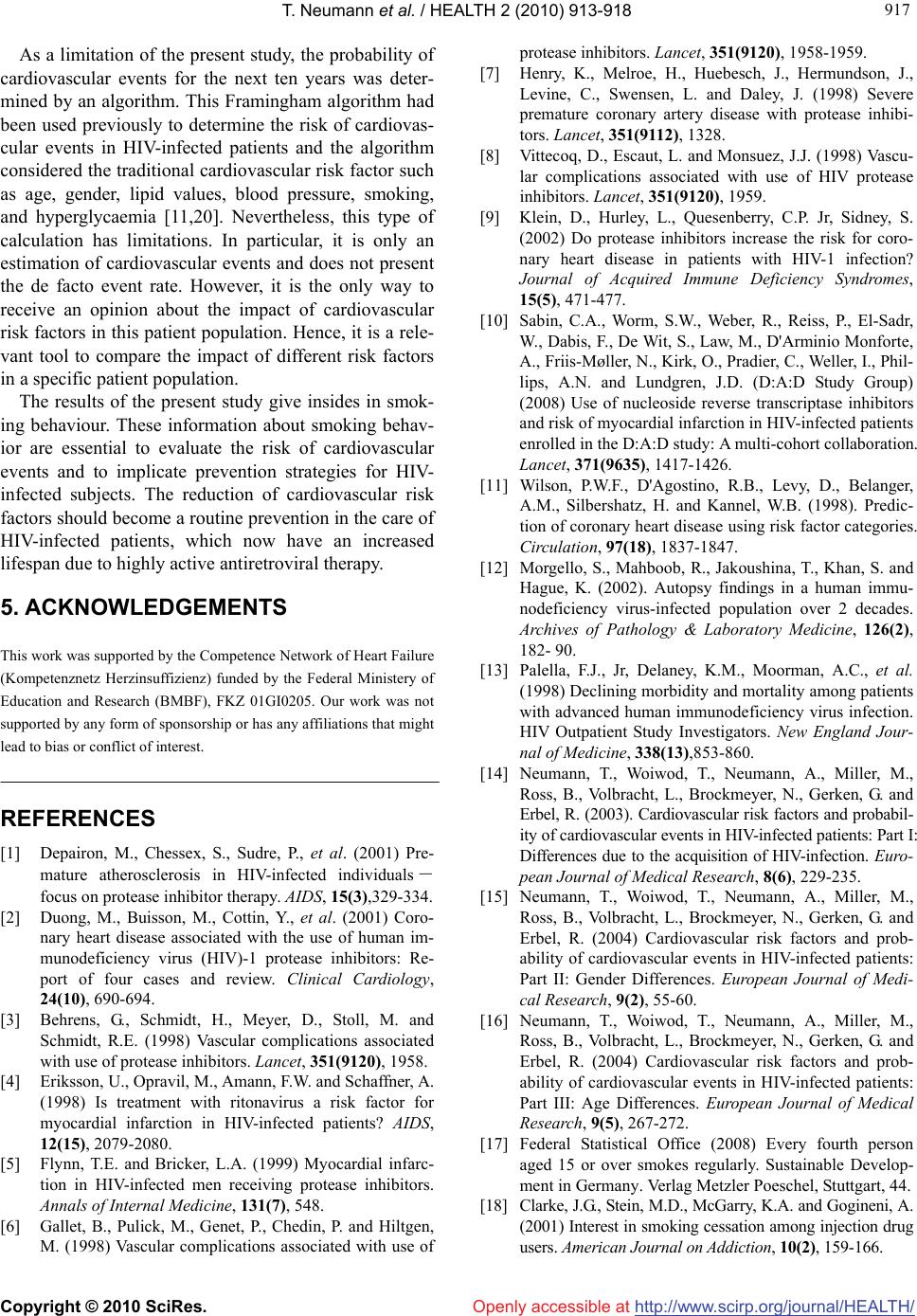

Vol.2, No.8, 913-918 (2010) doi:10.4236/health.2010.28135 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ HEALTH Openly accessible at Smoking behavior of HIV-infected patients Till Neumann1*, Nico Reinsch1, Stefan Esser2, Peter Krings1, Thomas Konorza1, Tanja Woiwoid1, Michael Miller3, Norbert Brockmeyer4, Raimund Erbel1 1Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Essen University, Medical School, Essen, Germany; *Corresponding Author: till.neumann@uni-essen.de 2Department of HIV-Medicine & Dermatology, Medical School, Essen University, Essen, Germany 3Department of Gastroenterology, Medical School, Essen University, Essen, Germany 4Department of Dermatology, Medical School, Bochum University, Bochum, Germany Received 10 March 2010; revised 2 April 2010; accepted 5 April 2010. ABSTRACT Recent reports describe an increased rate of cardiovascular events in smoking HIV-infected subjects. However, a lot is still unknown about smoking in this patient population. The purpose of the study was to analyze smoking behavior in HIV-infected subjects as a risk factor of coro- nary atherosclerosis and determine its effect on the probability of coronary events. We analyzed the cardiovascular risk factors of 294 HIV-infected adults (age: 42.1 10.1 years; 77% males). An elevated tobacco abuse was observed in 63.6% of the HIV-infected patients. Tobacco use was much more common in HIV-infected males than in females (67.8% vs. 49.2%; p < 0.01). Even elderly HIV-infected subjects had elevated rates of pack-years, the daily tobacco consumption does not seem to change at different ages (p > 0.2). Analysing the way of infection and the status of smoking, patients with HIV-infection acquired by heterosexual contact exhibited sig- nificantly lower rates of smoking compared with patients with HIV-infection acquired by MSM (man having sex with man) or by intravenous drug abuse (52.7% vs. 67.4%/82.1%, p < 0.01). The effect of smoking on the 10yrs. probability of coronary events determined by Framingham- equation was superior compared with all other classic cardiovascular risk factors. HIV-infected patients exhibited an increased tobacco use. Knowledge about smoking behavior in this pa- tient population is essential to evaluate the risk of cardiovascular events and to implicate pre- vention strategies for HIV-infected subjects. Keywords: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; Atherosclerosis; Smoking; Tobacco Consumption 1. INTRODUCTION Since the development of effective antiretroviral therapy concepts, the replication of the human immunodefi- ciency virus (HIV) could be decreased and its coincident deleterious effects on the immune system be diminished. Therefore, the HIV-infection has become a chronic dis- ease with a potential for long-term survival. However, the spectrum of HIV-related diseases has shifted from opportunistic infections towards long-term complications of HIV-infection and the antiretroviral therapy. Based on an increased rate of coronary events in HIV-infected patients, a variety of investigators are cur- rently focusing on metabolic disorders as a long-term effect of the highly antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and their risk for premature atherosclerosis [1,2]. In particu- lar, a rising number of case reports on myocardial infarc- tion in HIV-infected patients in recent years implicated an association between HAART and coronary heart dis- ease [3-8]. However, the results of register analyses of coronary heart disease in HIV-infected patients, which display a correlation between an increased rate of car- diovascular events and antiretroviral therapy, are still controversially discussed [9,10]. Therefore, in HIV-infected subjects further patho- physiological mechanisms may participate to premature atherosclerosis. In particular, classic cardiovascular risk factors, including smoking, are suspected to play a rele- vant role in the development coronary events. The pre- sent study was performed to assess smoking behavior as a cardiovascular risk factors in HIV-infected subjects and to determine its effects on the probability of coro- nary heart disease. 2. METHODS Patient population: All HIV-infected patients being  T. Neumann et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 913-918 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 914 treated in the Internal Medicine HIV-out patient depart- ment over a time period of 5 years were included into analysis. Of these 294 HIV-infected patients one hun- dred seventy three (58.9%) acquired HIV-infection by homosexual contact of man having sex with man, 83 (28.2%) by heterosexual contact, 28 (9.5%) by intrave- nous drug abuse and 10 (3.4%) by blood transfusion. A medical history was taken and a physical examina- tion performed by a physician. Of each patient, demo- graphic data, state of infection, antiretroviral medication and cardiovascular risk factors including personal history, lipid disorders, and smoking behaviors were analysed. If subjects were smokers, further information including the amount of cigarettes per day as well as the frequency and the time period of smoking-resulting in pack years data -were recorded and analysed. Resting systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured by oscillometric sphygmo-manometry. A total of 28 patients (9%) were on lipid-lowering therapy. Of these patients the lipid values were included before the start of the lipid-lowering therapy. The study was in agreement with the Local Council on Human Research and the Declaration of Helsinki. Calculation of the probability of coronary events: The prediction of coronary events was determined by the Framingham algorithm [11]. As major cardiovascular risk factors age, gender, total cholesterol, LDL choles- terol, blood pressure, smoking and diabetes were fea- tured into the calculation. The result of the Framingham prediction algorithm determines the 10-year probability of coronary events and gives information about the im- pact of each cardiovascular risk factor. Statistical Analysis: Variables that described demo- graphic data and data of smoking behavior were ex- pressed as mean values SD. The comparison of these variables was performed between distinct groups by one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni test. Nominal vari- ables were expressed as frequencies and comparisons performed by using Fishers exact test. Skewed variables such as variables describing the probability of coronary events were expressed as median and comparisons were done by Wilcoxon rank sum test and Dunn´s test (indis- tinct groups were compared by Wilcoxon signed rank for paired observations adjusted according to Bonferroni- Holm). A p < 0.05 was considered significant. 3. RESULTS Overall, HIV-infected patients exhibited an increased tobacco use. Of all 294 HIV-infected patients in the pre- sent study, 187 (63.6%) were regular smokers, nearly all of them consuming cigarettes (only one patient smoked pipe). The demographic data of smokers and non- smokers are presented in Table 1. There were no sig- nificant differences between smoking and non-smoking HIV-infected subjects concerning age, height, weight or body mass index in our analyses. Moreover, there was no significant difference in HIV-RNA concentration, CD4-count and antiretroviral therapy. In both groups, about one third of patients were in stage A, B and C of the disease, without significant dif- ferences due to the rate of smoking (smokers: 31.7%/ 33.3%/35.0%; non-smokers: 33.7%/26.9%/39.4%, res- pectively). Further cardiovascular risk factors, including systolic and diastolic blood pressure and elevated lipid or glucose concentration did not differ significantly be- tween the two groups (Table 2). Tobacco use was much more common in HIV-infected males than in females. While more than two thirds of HIV-infected males were smokers, the smoking rate in HIV-infected females was less than 50 percent (67.8% vs. 49.2%; p = 0.008). Even gender differences in HIV- infected patients were particularly assessed concerning the rate of smoking, no significant difference were pre- sent between these two groups in the time interval of smoking and the amount of cigarettes consumed includ- ing pack-years and cigarettes per day). Only 2.0% of HIV-infected males and 3.0% of females showed a daily cigarette consumption that was less than 5 cigarettes. In contrast, 44.1% of males and 33.4% of females smoked each day more than 20 cigarettes (Table 3). Table 1. Demographics and Antiretroviral Therapy. Non-Smoker Smoker p-value Demographics N (male/female)107 (73/34) 187 (154/33) Age [y] 42.9 11.6 41.7 10.9 0.38 Height [cm] 174.0 9.9 175.7 8.3 0.11 Weight [kg] 70.6 11.6 70.313.5 0.84 BMI [kg/m²] 23.4 3.7 22.7 3.7 0.11 HIV-RNA [copies/ml] 70 (50, 7000) 200 (50, 10500) 0.22 CD4 [cells/µl] 438 247 466 304 0.42 Antiretroviral Therapy NRTIs 91 (85.0%) 160 (85.6%)1.00 NNRTIs 48 (44.9%) 69 (36.9%) 0.22 PIs 49 (45.8%) 89 (47.6%) 0.81 Demographics data are presented as mean values SD, Antiretroviral therapy in percentage; NRTIs: nucleosidal reverse transcriptase inhibi- tors; NNRTIs: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; PIs: protease inhibitors  T. Neumann et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 913-918 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 915 915 Table 2. Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Non-SmokerSmoker p-value Hypertension SBP [mmHg] 122.8 17.3120.3 16.5 0.23 DBP [mmHg] 79.6 11.3 78.2 11.6 0.33 Hyperlipidaemia Total cholesterol [mmol/L] 5.59 1.47 5.49 1.40 0.56 HDL-cholesterol [mmol/L] 1.20 0.49 1.14 0.45 0.34 LDL-cholesterol [mmol/L] 3.52 1.69 3.50 1.38 0.93 Triglycerides [mmol/L] 2.88 2.96 2.76 3.19 0.76 Hyperglycemia Glucose [mmol/L] 5.5 (4.9, 6.3)5.3 (5.0, 6.3) 0.53 HbA1c [%] 5.3 0.9 5.1 1.1 0.10 Data are mean values SD or median (lower quartile, upper quartile); SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure. The majority of smoking HIV-infected were 31 to 40 years old and consumed 11 to 40 cigarettes per day. No significant differences were found in our study between the rate of smoking at different ages (18-30 yrs: 58.4%, 31-40 yrs: 64.6%, 41-50 yrs. 69.8%, > 50 yrs. 55.3%). As expected, elderly HIV-infected subjects of more than 40 years had a significantly higher amount of pack-years compared with younger HIV-infected subjects. Even the smoking period of elderly subjects was increased, no significant differences were found in respect of daily tobacco consumption (Table 4). Analysing the way of infection and the status of smo- king, also significant differences were present (Table 5). In particular, the group of patients with HIV-infection acquired by heterosexual contact exhibited significantly lower rates of smoking compared with patients with HIV-infection acquired by MSM (man having sex with man) or by intravenous drug abuse. The lowest rate of smoking was present in patients with HIV-infection ac- quired by blood transfusion. However, a no significant differences to other groups were found due to the low rate of patients of this way of infection. As presented in Figure 1, the prediction value for coronary events in the next 10 years was significantly higher in smoking HIV-infected patients compared with non-smoking HIV-infected patients (7.2% vs. 4.9%; p < 0.001), respectively. Especially, male HIV-infected pa- tients exhibited an elevated probability of coronary events compared with female HIV-infected patients in the smoker group (9.8% vs. 2.3%; p < 0.001), respec- tively. The calculated effect on the probability of coro- Table 3. Gender differences. Mean SD < 5 5-10 11-20 21-40 > 40 Cigarettes per day: - all 25.0 14.0 2.1% 15.5% 40.1% 35.3% 7.0% - males 25.2 13.5 2.0% 14.3% 39.6% 37.0% 7.1% - females 24.0 16.4 3.0% 21.2% 42.4% 27.3% 6.1% p-value (males vs. females): 0.68 Pack years: all 21.9 15.2 6.4% 20.3% 30.5% 36.4% 6.4% males 22.6 14.8 5.9% 18.8% 29.2% 39.6% 6.5% females 19.1 17.0 9.1% 27.3% 36.4% 21.2% 6.0% p-value (males vs. females): 0.24 Table 4. Age differences. N (%) Mean SD < 5 5-10 11-20 21-40 > 40 Cigarettes per day: - 18-30 22 (11.8%) 19.4 8.4 9.1% 13.6% 54.6% 22.7% 0.0% - 31-40 81 (43.3%) 24.7 12.5 1.2% 14.8% 38.3% 38.3% 7.4% - 41-50 50 (26.7%) 26.5 15.5 0.0% 18.0% 34.0% 42.0% 6.0% - > 50 34 (18.2%) 26.9 17.3 2.9% 14.7% 44.1% 26.5% 11.8% p-value between groups: 0.31  T. Neumann et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 913-918 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 916 Openly accessible at Table 5. Way of Infection. All Group 1 Group 2 Group 3 Group 4 Smoking, % 63.6% 66.4% 53.0% 85.7% 40.0% package-years 21.4 1.0 22.5 1.4 25.2 2.5 24.7 2.6 38.8 14.6 cigarettes per day 24.8 1.0 24.9 1.4 20.1 2.3 20.2 2.1 44.2 16.0 Group 1: HIV-infection acquired by man having sex with man; Group 2: HIV-infection acquired by heterosexual contact; Group 3: HIV-infection acquired by intravenous drug abuse; Group 4: HIV-infection acquired by blood transfusion. Figure 1. The 10-year probability of coronary events deter- mined by the Framingham prediction algorithm in distinct groups of HIV-infected individuals, due to the quality of smoking. The 10-year probability of coronary heart disease in the next 10-years was significantly higher in smokers than in non-smokers. Data are expressed as median plus lower quartile and upper quartile. nary events by smoking is superior compared with all other classic cardiovascular risk factors. 4. DISCUSSION The present study demonstrates that smoking is a com- mon cardiovascular risk factor in HIV-infected patients. Furthermore, smoking seems to have a remarkable and superior impact for the occurrence of cardiovascular events in this patient population compared with other classic cardiovascular risk factors including hyperlipi- daemia. Recent clinical trials describe an increased rate of car- diovascular events in HIV-infected patients [9,10]. In addition, the rate of atherosclerosis in autopsies of HIV-infected patients has increased [12]. Consequently, there is an increased concern that these changes may lead to an epidemic increase of cardiovascular diseases in the HIV-positive population. The development of new antiretroviral drugs includ- ing protease inhibitors has reduced the mortality and morbidity of HIV-infected patients [13]. The increased lifespan in combination with the metabolic side effects of the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), such as hyperlipidaemia and insulin resistance, has been expected to contribute to the increased rate of athero- sclerosis in HIV-infected patients. However, other risk factors than hyperlipidaemia and insulin resistance, may also have an effect on the development of premature atherosclerosis in HIV-infected patients [14-16]. The results of the present study emphasise, that smo- king is an important risk factors, which has a remarkable impact on the incidence of cardiovascular events in HIV- infected patients. Our data further reveal a high percent- age of smokers among the study population of individu- als living with HIV. The rate of smokers in our sample was far above the prevalence estimated for the general adult population in the same area (63.6% vs. 23.5%, p < 0.001) [17]. In addition to the increased rate of smoking, the cigarette consume per day of HIV-infected smokers was elevated compared with HIV-negative smokers in the general adult population (25.0 vs. 16.4 cigarettes per day). One reason for the higher frequency of smokers might be the portion of people with intravenous drug abuse and men who have sex with men in the population of HIV-infected patients. Both groups have an increased smoking rate [18,19]. Among individuals living with HIV, previous studies have found that smokers are at greater risk for develop- ing bacterial pneumonia, oral lesions, and the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. However, our study re- sults reveal that smokers with HIV-infection also have an elevated risk of cardiovascular events than non- smokers with HIV-infection. The risk of cardiovascular events was especially elevated in male smokers with HIV-infection. However, the probability of cardiovascu- lar events of female smokers with HIV-infection was comparable or even lower than the risk of non-smoking HIV-infected individuals. Compared with HIV-infected non-smokers, the in- creased probability of cardiovascular events in HIV- infected smokers was not associated to differences in other coronary risk factors, such as hypertension, hyper- lipidaemia or hyperglycaemia. Furthermore, there were no differences in antiretroviral therapy between the smoker group and the non-smoker group.  T. Neumann et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 913-918 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 917 917 Openly accessible at As a limitation of the present study, the probability of cardiovascular events for the next ten years was deter- mined by an algorithm. This Framingham algorithm had been used previously to determine the risk of cardiovas- cular events in HIV-infected patients and the algorithm considered the traditional cardiovascular risk factor such as age, gender, lipid values, blood pressure, smoking, and hyperglycaemia [11,20]. Nevertheless, this type of calculation has limitations. In particular, it is only an estimation of cardiovascular events and does not present the de facto event rate. However, it is the only way to receive an opinion about the impact of cardiovascular risk factors in this patient population. Hence, it is a rele- vant tool to compare the impact of different risk factors in a specific patient population. The results of the present study give insides in smok- ing behaviour. These information about smoking behav- ior are essential to evaluate the risk of cardiovascular events and to implicate prevention strategies for HIV- infected subjects. The reduction of cardiovascular risk factors should become a routine prevention in the care of HIV-infected patients, which now have an increased lifespan due to highly active antiretroviral therapy. 5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was supported by the Competence Network of Heart Failure (Kompetenznetz Herzinsuffizienz) funded by the Federal Ministery of Education and Research (BMBF), FKZ 01GI0205. Our work was not supported by any form of sponsorship or has any affiliations that might lead to bias or conflict of interest. REFERENCES [1] Depairon, M., Chessex, S., Sudre, P., et al. (2001) Pre- mature atherosclerosis in HIV-infected individuals- focus on protease inhibitor therapy. AIDS, 15(3),329-334. [2] Duong, M., Buisson, M., Cottin, Y., et al. (2001) Coro- nary heart disease associated with the use of human im- munodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 protease inhibitors: Re- port of four cases and review. Clinical Cardiology, 24(10), 690-694. [3] Behrens, G., Schmidt, H., Meyer, D., Stoll, M. and Schmidt, R.E. (1998) Vascular complications associated with use of protease inhibitors. Lancet, 351(9120), 1958. [4] Eriksson, U., Opravil, M., Amann, F.W. and Schaffner, A. (1998) Is treatment with ritonavirus a risk factor for myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients? AIDS, 12(15), 2079-2080. [5] Flynn, T.E. and Bricker, L.A. (1999) Myocardial infarc- tion in HIV-infected men receiving protease inhibitors. Annals of Internal Medicine, 131(7), 548. [6] Gallet, B., Pulick, M., Genet, P., Chedin, P. and Hiltgen, M. (1998) Vascular complications associated with use of protease inhibitors. Lancet, 351(9120), 1958-1959. [7] Henry, K., Melroe, H., Huebesch, J., Hermundson, J., Levine, C., Swensen, L. and Daley, J. (1998) Severe premature coronary artery disease with protease inhibi- tors. Lancet, 351(9112), 1328. [8] Vittecoq, D., Escaut, L. and Monsuez, J.J. (1998) Vascu- lar complications associated with use of HIV protease inhibitors. Lancet, 351(9120), 1959. [9] Klein, D., Hurley, L., Quesenberry, C.P. Jr, Sidney, S. (2002) Do protease inhibitors increase the risk for coro- nary heart disease in patients with HIV-1 infection? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 15(5), 471-477. [10] Sabin, C.A., Worm, S.W., Weber, R., Reiss, P., El-Sadr, W., Dabis, F., De Wit, S., Law, M., D'Arminio Monforte, A., Friis-Møller, N., Kirk, O., Pradier, C., Weller, I., Phil- lips, A.N. and Lundgren, J.D. (D:A:D Study Group) (2008) Use of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients enrolled in the D:A:D study: A multi-cohort collaboration. Lancet, 371(9635), 1417-1426. [11] Wilson, P.W.F., D'Agostino, R.B., Levy, D., Belanger, A.M., Silbershatz, H. and Kannel, W.B. (1998). Predic- tion of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation, 97(18), 1837-1847. [12] Morgello, S., Mahboob, R., Jakoushina, T., Khan, S. and Hague, K. (2002). Autopsy findings in a human immu- nodeficiency virus-infected population over 2 decades. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, 126(2), 182- 90. [13] Palella, F.J., Jr, Delaney, K.M., Moorman, A.C., et al. (1998) Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. New England Jour- nal of Medicine, 338(13),853-860. [14] Neumann, T., Woiwod, T., Neumann, A., Miller, M., Ross, B., Volbracht, L., Brockmeyer, N., Gerken, G. and Erbel, R. (2003). Cardiovascular risk factors and probabil- ity of cardiovascular events in HIV-infected patients: Part I: Differences due to the acquisition of HIV-infection. Euro- pean Journal of Medical Research, 8(6), 229-235. [15] Neumann, T., Woiwod, T., Neumann, A., Miller, M., Ross, B., Volbracht, L., Brockmeyer, N., Gerken, G. and Erbel, R. (2004) Cardiovascular risk factors and prob- ability of cardiovascular events in HIV-infected patients: Part II: Gender Differences. European Journal of Medi- cal Research, 9(2), 55-60. [16] Neumann, T., Woiwod, T., Neumann, A., Miller, M., Ross, B., Volbracht, L., Brockmeyer, N., Gerken, G. and Erbel, R. (2004) Cardiovascular risk factors and prob- ability of cardiovascular events in HIV-infected patients: Part III: Age Differences. European Journal of Medical Research, 9(5), 267-272. [17] Federal Statistical Office (2008) Every fourth person aged 15 or over smokes regularly. Sustainable Develop- ment in Germany. Verlag Metzler Poeschel, Stuttgart, 44. [18] Clarke, J.G., Stein, M.D., McGarry, K.A. and Gogineni, A. (2001) Interest in smoking cessation among injection drug users. American Journal on Addiction, 10(2), 159-166.  T. Neumann et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 913-918 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 918 [19] Stall, R.D., Greenwood, G.L., Acree, M., Paul, J. and Coates, T.J. (1999) Cigarette smoking among gay and bisexual men. American Journal of Public Health, 89(12), 1875-1878. [20] Hadigan, C., Meigs, J.B., Wilson, P.W., et al. (2003) Prediction of coronary heart disease risk in HIV-infected patients with fat redistribution. Clinical Infectious Dis- eases, 36(7), 909-916. |