Open Journal of Political Science 2012. Vol.2, No.3, 32-44 Published Online October 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojps) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojps.2012.23005 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 32 Advocacy and Policy Change in the Multilevel System of the European Union: A Case Study within Health Policy Nadia Carboni National Research Counc il of Italy, Bologna , Italy Email: nadia.carboni@irsig.cnr.it Received June 20th, 2012; revised July 10th, 2012; accep te d S ep tember 26th, 2012 Health policy is basically Member States’ competence. However, the European Union has recently raised a number of key questions facing both (pharmaceutical) industries and public health interests. By apply- ing the Advocacy Coalition Framework, the paper sheds light on policy change within the European multileve l system. The analysis is based on a case-study strategy. Two processes in the pharmaceutical policy are taken into account: the “Pharma Forum” and the “Pharma Package”. They both concern “information to patient”—a controversial policy issue at the crossroad of competing pressures. Keywords: Advocacy Coalition Framework; European Union; Policy Change; Lobbying; Pharmaceutical Policy Introduction The main goal of this study is to give evidence of the policy change process within EU multilevel system1 by empirical ac- counts of lobbying in health care related issues. By applying the Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) as a theoretical basis for understanding both EU policy-making process and intergo- vernmental relations2 within health policy field, this paper ana- lyzes the policy subsystem-wide dynamics with multiple actors who structure their relationship into advocacy coalitions moved by policy beliefs, and try to influence policy by multiple re- sources and venues. The ACF is often used to explain stake- holders’ behaviour and policy outcomes in conflicting political contexts, with two or more coalitions pursuing different policy objectives (Sabatier and Weible, 2005). This is the case of EU health policy making, where divergent interests stand in oppo- sition, public health and health-care on the one hand, and in- dustrial policy on the other. The paper is structured as follows: first, we outline the con- ceptual framework (ACF) and methodology for the analysis; second, we define the boundary of the policy field (EU health policy), within which the case-study is carried out; third, we apply the ACF by sketching out the main actors and their re- spective roles, the resources involved, the venues of influences, the patterns of interaction in EU health policy making process; finally, we draw some conclusions about the theoretical and empirical contributions of this study. Theoretical Framework The ACF (Jenkins-Smith and Sabatier, 1993, 1999; Sabatier, 1998) views the policy process as a competition between coalitions of actors who advocate beliefs about policy problems and solutions. This competition takes place within policy sub- systems, defined as the set of actors who are actively concerned with an issue and regularly seek to influence public policy re- lated to it. Actors in a policy subsystem include local and state government officials, advocacy groups, non-governmental or- ganizations, community groups, researchers and academics, me- dia, etc. Following works in cognitive and social psychology, the ACF argues that actors perceive the world and process informa- tion according to a variety of cognitive biases which provide heuristic guidance in complex situations. In the case of public policies, such guidance is provided by belief systems about how a given public problem is structured, and how it should be dealt with. The belief system is what makes coalitions hold together and builds the basis for their coo rdination and internal organization. Jenkins-Smith and Sabatier (1993) distinguish three levels of beliefs in the belief system of a coalition: Deep Core: normative and ontological axioms that define a vision of the individual, society and the world; Policy Core: causal perceptions and policy positions for achieving deep core beliefs in a given policy subsystem; Secondary Aspects: empirical beliefs on how to implement the policy core. Coalitions, the ACF argues, form around beliefs, and par- ticularly around policy core beliefs. In order to realize the goals generated by their beliefs, advocacy coalitions try to make gov- ernmental institutions behave in accordance with their policy cores. In this, they are assumed to be instrumentally rational, for instance using venues provided by the constitutional struc- ture through which they can exert influence in an efficient way. Based on these premises, the ACF perceives policy change as a transformation of a hegemonic belief system within a policy subsystem3, whereas policy learning as a process which is most likely to concern only secondary aspects of a belief system, leaving the policy core of a coalition intact, and bringing to minor policy changes (Sabatier, 1998). Minor policy changes4 1The focus of the analysis is on EU level policy-making, activities at the Member States level are not included. 2Studies involving both the horizontal and vertical relations between sub- national, national and/or supranational governments may all be categorized under the field of IGR. Some of these studies might well be conceptualized as (and this i s the case) European Multi-Level Governance.  N. CARBONI are the result of two processes: learning within and learning across coalitions. The second case is where policy brokers may intervene. When two or more coalitions are in conflict and it is difficult to have a dialogue between them, policy brokers me- diate the conflicting belief systems looking for some reasonable compromise which will reduce conflict intensity. For that, po- licy brokers have to be able to relativisized the beliefs and pre- ferences of the competing coalitions to facilitate policy solution. In addition, they must be linked to decision makers or have ac- cess to decision-making points. Within the ACF, we refer to the components of the approach more useful for our analysis: a) the role of information and knowledge; b) the role of policy broker; c) the factors of success necessary to produce policy change. Finally, we aim to look for more insights about the role of policy broker and the definition of policy change at the EU level. Studies applying the ACF outside the United States con- firm it has wide applicability. While most of these studies focus on the descriptive validity of the ACF, more work is needed to both critically examine its assumptions about policy change in various institutional contexts. The ACF seems not to explain several important aspects of policy change, neither does the model provide a precise framework to examine in detail how policy brokers accomplish their tasks (Smith, 2000). Methodology. The ACF approach is tested by using a qua- litative research strategy-namely a case study design. Two pro- cesses, the “Pharma Forum” and the “Pharma Package”, have been selected since they both involve diverging interests (public health and social protection vs. industrial interests). A certain level of conflict is necessary in order to study the interplay be- tween multiple actors in the policy-making process. Moreover, they both concern information to patient, a controversial policy issue at the crossroad of competing pressures. The fieldwork has relied mostly on documents analysis, semi-structured interviews, and personal observation. The main sources were governmental documents: Commission commu- nications, speeches, minutes of the plenary meetings of the European Parliament and minutes of Council working groups meeting, positions papers by interest groups, national govern- ments publications and press releases, etc. The information collected by documents was combined with semi-structured interviews, which were carried out during April-June 2009. The sample of interviewees was made of the key actors we iden- tified by both relevant documents and the snowball technique. Starting with suggestions from preliminary interviews, a snow- ball-sampling technique5 generated a list of stakeholders (n = 30). This method suits the case of health policy, since it allows us to catch one specific network of interconnected people. By snowball method we managed to cover all the different types of actors involved in the process: consumers and patients groups, umbrella organizations, individual companies, pharmaceutical industries and civil society groups, policy officers from the European Commission, members of the European Parliament, Health attachés from the Permanent Representations in Brussels (Table 1). Finally, visiting the European Social Observatory (OSE asbl) in Brussels for three months has allowed us to take part to events and conferences about the research topic. The EU Health Policy within the Pharmaceutical Sector Health policy is generally not considered as a policy area of the Community, because there is no legal Union competence for that (Lamping, 2005: p. 19). This is basically due to the successful resistance of national governments to transfer sub- stantial health policy competencies to the supranational level. In detail, the European Union did not have policy mandate in the field of public health until 1999, when the public health article was amended and renumbered by the Treaty of Amster- dam as the current Article 152 (Mossialos et al., 2009). Treaty Article 152 defines the role of the EU as complementing na- tional policies, sets out procedures by which the EU institutions may act in the health field, and delineates the types of measures that may be enacted, but explicitly bars the use of harmoniza- tion: “Community action in the field of public health shall fully respect the responsibilities of the Member States for the or- ganization and delivery of health services and medical care” (Art. 152, No. 5). Thus, the EU is limited to establishing public health programmes and incentives in the health policy field. Moreover, after the health sector’s exclusion from the EU Ser- vices Directive6, which aims to break down barriers to cross- border trade in services between EU Member States, health and long-term care were formally added to the Open Method of Coordination (OMC)7 procedures conducted by the Social Pro- tection Committee (SPC) in 2005. One of the most controversial aspects related to health gover- nance in Europe is properly the clash between the suprana- tional free movement rules and national healthcare policy competencies. This is especially relevant to pharmaceutical sector. Although pharmaceuticals represent a policy domain where outcomes are mainly related to market and industrial policy goals, they must also achieve healthcare interests-such as eeping healthcare costs down and ensuring the safety, efficacy k 5Snowball sampling may simply be defined as “a technique for finding research subjects. One subject gives the researcher the name of another subject, who in turn provides the name of a third, and so on” (Vogt, 1999 ) . 6A wide vari et y o f heal t h related lobbyi ng groups oppos ed th e application o the Serv ices Di rective b y clai ming t hat heal th car e serv ices ar e ‘un ique’ and should not be treated as any other commercial service; and that Member States would have difficulty managing their health systems with the addi- tional EU oversight. 7The EU’s relatively new “open method of coordination” is characterized by an intergovernmental form of policy-making. Under this open method, Member States co-operate with each other on legislating reforms by estab- lishing common timetables, indicators and policies, with greater emphasis on consensus and mutual learning among Member States. Under the tradi- tional, so-called “community method” of EU governance, more power was held by bodies such as the European Commission and the European Court of Justice than by the Member States. 3The ACF takes into account also the influence of exogenousvariables on the policy subsystem. Two sets of external factors frame and constrain the activities of advocacy groups, the one quite stable, the other more dynamic. Stable parameters include the basic constitutional structure, socio-cultural values, and natural resources of a political system; dynamic influences in- clude external changes or events in global socioeconomic conditions (Sa- batier, 199 8 ). 4The ACF defines minor policy change as a modification of specific beliefs about causal connections and stakes of the world that have bearing in the olicy issu e area (chang es in second ary aspects of the pol icy subsyst em); in contrast, the ACF defines major policy change as an alteration of the policy core beliefs. Policy learning rarely results in major policy change, as it is secondary aspects which tend to be modified by endogenous learning whereas it is wholesale shifts in dominant policy core belief which are associated w ith major policy change (Sm ith, 2000). Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 33  N. CARBONI Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 34 Table 1. Sample of interviewed organizations (N. interviews = 30). Consumer s/patients organizations The European Consumers’ Organisation (BEUC); The Euro pean Patients’ Forum (EPF ) Health prof essiona l a nd provider organiza t ions The European Federation of Nurses Associations (EFN); The Standing Committee of European Doctors (CPME); The Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union (PGEU); The European Hospital and Healthcare Federation (HOPE) Pharmaceutical industry associations The Europ ean Generic Med icines Ass ociation (EGA); The Eur opean Feder ation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA); The European medical technology industry association (EUCOMED); The European Self-Medication In- dustry (AESGP); The European Association of pharmaceutical full-line wholes al- ers (GIRP); The representation offices in Brussels of “Merck Sharp & Dohme” and of “Novartis” companies Health and social protection organizations European Public Health Alliance (EPHA); Asso ciation I nternational de la mutualitè (AIM); European Social Insurance Platform (ESIP); European Regional and Local Health Authorities (EUREGHA) Institutions European Parliament: Committee on Industry, Research and Energy; Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Sa fety. European Commission: The Directorate General for Health & Consumers (DG Sanco); The Directorate General for Enterprise (DG Enterprise); The Internal Market and Services Directorate General; (DG MARKT) Council: Permanent representations of Italy and of Czech Republic to Europe, Czech Republic EU Presidency Note: Source : author’s elaboration. However, only limited attention has been focused on the and quality of medicines, and the Commission has only com- petence over the former (Mossialos and Permanand, 2005b). While the Commission can, for instance, promote the cross- border movement of medicines by pushing harmonization, ac- cording to the Single European Market; the Member States have the power to decide their own healthcare policy priorities, under the principle of subsidiarity. It means that the Commis- sion must balance industrial and public health concerns, and reconcile wider social and political interests within the context of market harmonization. As a consequence, EU pharmaceuti- cal policy has reached something of a deadlock “stemming primarily from a dissonance between the principle of subsidia- rity and the free movement goals of the Single Market—under which medicines are treated as an industrial good” (Mossialos and Permanand, 2005b: p. 49). Nevertheless, the Commission has been able, for instance, by employing soft law mechanisms such as the OMC-to establish a wide-ranging Community re- gulatory framework8, even if a single medicines market remains a faraway goal. process of health policy making at the EU level, missing the dynamics and the interactions among different governmental and private actors (Mossialos and Permanand, 2005a). In the following paragraphs we will focus on two different processes both part of the pharmaceutical policy. The first ex- amines the High Level Pharmaceutical Forum, a three years process of stakeholders’ consultation about health care related issues. The second concentrates on a series of measures re- cently proposed by the European Commission impacting the pharmaceutical industry (“the Pharma Package”). Although it dates back to several Commission attempts to review pharma- ceutical legislation in order to increase competitiveness of the EU pharmaceutical industries vis-à-vis US industry, it has not yet been concluded. Reaching agreement on this issue is diffi- cult, because it involves conflicting interests among public health and social protection groups on the one side and Indus- tries on the other side. In other terms, it refers to the clash between Member States social protection and public health policy objec- tives and the Commission industry policy goals. Finally, although any harmonisation of the laws and regula- tions on health policy in the Member States is excluded, the impact of the EU upon health matters is increasing (Leibfried and Pierson, 2000): The High Level Pharmaceutical Forum The official aim of the Pharmaceutical Forum was to im- prove the competitiveness of the pharmaceutical industry and its contribution to social and public health objectives. By ex- changing best practices and examining efficiency gains within a European high level platform, it intended to contribute to en- suring patients’ access to medicines within a sustainable health- “Health policy is a challenging example of how to make a formal non topic one of the Union’s major future policy fields- despite the treaty” (Lamping, 2005: p. 21). 8For a chronological overview of the development of EU pharmaceutical policy see: Mossialos a n d Permanand, 2005b: pp. 50-53.  N. CARBONI care budget, and to discuss the competitiveness of the European pharmaceutical industry and related public health considera- tions. The Forum was set up as a follow-up to the “G10 Medi- cines”9 which discussed the balance of health objectives and industry competitiveness in Europe. Compared to the G10, the High Level Pharmaceutical involved a higher number of stake- holders. It was composed by at least 40 members, more than half of which were Member State representatives ( Table 2). Out of the 10 non-governmental participants, five represent phar- maceutical and biotech businesses, and five represent non- business interests. However, these other organisations include the European Patients Forum, whose legitimacy has been ques- tioned because of its close ties with industry and its lack of transparency. The Pharma Forum was based on three main issues: 1) rela- tive effectiveness: increasing the quality and quantity of avail- able data and analysing current assessment processes; 2) pric- ing and reimbursement: developing solutions for access, and trade-problems, to ensure timely and equitable access to phar- maceuticals for patients, to enable control of pharmaceuticals expenditure by Member States and to reward valuable innova- tion that also encourages research & development; 3) informa- tion to patients: improving the quality of information to patients about diseases and treatment options. Three working groups focusing on the above topics formed in 2006, and the first full Forum met and adopted a progress report in September 2006. In spring 2007, the Commission organised a public consultation on the work of the Pharma Forum’s Information to Patient Working Group. A second meeting of the Forum took place in June 2007 and another progress report was adopted. The third and final meeting was held in October 2008, when a set of conclusions and recommendations were adopted. The consultation lasted three years and it was depicted as not an easy process by our interviewees: “During the first year we established common perspectives and shared best practices; the second year was very critical: dealing with different interests on the same board was very painful. At the end we tried to identify common interests and a balanced approach. But you know, we have the shortcoming that we could not legislate about those topics. Given that, the results were ‘wea k’. However weak is better than nothing” (Policy officer, DG Enterprise). “It was a very difficult process. The idea was to have a con- sensus based process. However, you work with different stake- holders, but first with individuals having conflicting interests. It is sometimes not clear to identify who is behind the interest group” (Policy officer, DG Sanco). “Consensus and support on certain issues by both industries and patients groups were very hard. We all start from a com- mon perspective on the problem, but then everybody shows different positions. The role of the Commission was very im- portant in finding a compromise among different positions” (Lobbyist, Pharmaceutical company). There has also been strong criticism of the composition of some of the individual working groups, especially the working group on information to patients. During a public consultation in spring 2007, several organisations such as the European consumer organisation (BEUC) and Health Action International (HAI) strongly criticized the methods and outcomes of the In- formation to Patients Working Group (Table 3 resumes suc- cess and failure factors of the Pharma Forum according to the samp le of interviewees). BEUC said there were major flaws in the structure of the group, that it was the wrong type of forum for such a project, and that the methods were “not appropri- ate, do not bring added value and are not the way to develop information for patients... It was appointed in a selective manner without transparency or clear criteria, and with a Table 2. Composition of the Pharma Forum. Governmental participants -Two Comm iss ioners: Enterpri s e & Industry, Health & Consumer Protection; -Ministers from each of the 27 Member States were invited ; -Three Members of Europe an Parliament (ALDE, EPP, PSE). Non-governmental participan ts -Five representing business: EFPIA (European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries & Associations), AESGP (E uropean Self-Medication I ndustry), EGA (European Generic medicines Association), EuropaBio (European A s sociation for Bio-industries), GIRP (E uropean Association of Full-Line Wholesalers) -Five patients and health groups: European Patients Forum (NGO funded by industry), PGEU (Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union representin g community pharmacists) CPME (Standing Committee of European Doctors representing all medical doctors in the EU), AIM (Association Internationale de la Mutualité), ESIP (European Social Insurance Platform) Note: Source : author’s elaboration. 9The High Level Group on Innovation and Provision of Medicines—The G10 Medicines Group—was set up following a symposium on Pharmaceutical Industry Competi- tiveness held in December 2000. The objective of the Group was to review the extent to which current pharmaceutical, health and enterprise policies could achieve the twin goals of both encourag ing innovation and competitivenes s and ensurin g satisfactory deliv ery of public heal th and social imperati ves. The membership of the Group consisted of representation at the highest level from different administrations and organisations: from the Member States, the Swedish Minister of Industry, together wi th the French, German, British and Portuguese Ministers of Health; from the industries, EFPIA, EGA, AESGP; from health organizations, AIM and a patient representative from the Picker Institute. It was evident the overrepresentation of the pharmaceutical industry. The G10 recommended the need for a workable distinction between adver- tising and information. Furthermore a collaborative public-private partnership involving a range of interested parties should have been established. (http://ec.europ a.eu/health/ph_o verview/Docu ments/key08_en .pdf) Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 35  N. CARBONI Table 3. Pharma Forum: success and failure factors. + – -“all stakeho lders together for the first time” (Lobbyst, Heal th professional organization) -“understanding other points of view” (Lobbyst, Patient Organi- zation) -“all the interests were represented and had the chance to raise their own voice” (Lobbyst, Pharmaceutical Company) -“spreading knowledge” (Policy officer, DG Sanco) -“exchange of best practices” (Policy Officer, DG Enterprise) -“Member States a nd stakeholders working together” (Lobbyst, Pharmaceutical Company) -“the Pharma Forum was very well orga nized. Moreover, the role of the Commission was really hel pf u l in favouring the exchange of practices”. (Lo bb yst, Pharmaceutical Industry Ass o ciation) -painful proce ss : the more pe op le you have around the table the more difficult is to achieve consensus (Policy officer, DG Sanco) -outcome not transparent: “the process was not at all transparent. Com mission synthesized the results of the meetings without making clear who contributed to what” (Lobbyist, Health org anization ) -“it was ve ry time consum ing proce s s” (Lobbyst, Pharmaceutical Industry Asso ciation) -criteria for selecting participants were not cl ear: “We did not understand why some key stakeholders were not invited to the forum” (L obbyist, Health profession al organizatio n) -the process was driven by the Commission: “Commissi on did not m ake circulate our point of view among the other stakeholders. It decided what or what not to include i n t h e results ” (Lobbyist, S o cial Protection organization) -“It was the mountain which has given birth to the mickey mouse” (Health attaché, Italian Permanent Representation) -“The Pharma Forum was a way for industries to lobby the Commission” (Health attaché, Czech Republ ic Permanent Representation) Note: Source : author’s elaboration. composition that was bound to politicize the issues under discussion”. A policy officer from DG Sanco replied to our question about the criteria for inviting advocacy groups to join the Pharma Forum, as follows: “We usually invite stakeholders who have expertise in the topic we discuss. As far as the Pharma Forum we invited 10 stakeholders—half from the private sector, half from the civil society—whom we think they have expertise in that topic. BEUC, for example, was not very active on that issue at that time. Expertise in lobbying is a moving process. Stakeholders are invited to join policy making process according to the topic and the expertise they have” (Policy Officer, DG Sanco). A policy officer from DG Enterprise added: “We tried to cover all the different interests, but it was clear for us that in inviting stakeholders we did not want people shut- ting at the table” (Policy Officer, DG Enterpise). In June 2007, the Association Internationale de la Mutualité (AIM) and the European Social Insurance Platform (ESIP) issued a position statement expressing their dissatisfaction with the Pharma Forum way of working and substance. They ob- jected to the use of the word “partnership” to describe the pro- cedures followed so far in the working group. It read: “ESIP and AIM still have concerns about the lack of transparency of the processes, procedure and methodologies in the Forum, in particular the Working Group on information to patients.” The statement also indicated that suggestions put forward by ESIP and AIM were not being taken into consideration in the infor- mation process and debated: “ESIP and AIM strongly regret that their constructive proposals made during this process, in par- ticular the request for a survey for existing patient infor- mation practices and the use of an EU quality label to identify high quality information, have not been taken up for further discus- sion”10. A major contentious issue in the Information to Patients Working Group was a proposal to weaken the ban on direct- to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs11. BEUC, HAI, AIM and ESIP objected that their concerns over the conflicts of interest for pharmaceutical companies providing information for patients between independent information and product marketing were not taken seriously. They argued that public health interests should not be mixed or even over-ridden by commercial interests—i.e. information to patients should not come directly from those who produce medicines because the main goal of pharmaceutical companies is to maximise sales. Similarly, the Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union (PGEU) stated that health professionals, including pharmacists and doctors, should remain the primary source of easily acces- sible and reliable information about medicines, and that the pharmaceutical industry should not be given more scope to “push” information to patients. In the final conclusions, the Pharmaceutical Forum recom- mended retaining the ban on advertising prescription medicines to the general public, but at the same time also recommended that “all the relevant players, including national competent authorities, the Commission, public health stakeholders and 10 ESIP&AIM Joint Statement: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/phabiocom/docs/pf_20070626_esip_aim_joint statement.pdf; all contributions to the consultation: http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_overview/other_policies/pharmaceutical/result s_consultation_en.htm; an overview of comments regarding information to patients can be found here: http://www.haiweb.org/28102007/ManyConcerns.pdf. 11In the EU advertising of drugs is regulated by Directive 92/28/EEC ban- ning advertising of prescription-only drugs to the general public. In 2001 the Commission proposed a partial lifting of the ban giving manufactures the chance to inform patients on their medical products for HIV/AIDS, diabetes and asthma . 12Commission synthesized the results of three years consultation process in an 11 pages report. A footnote explains that AIM expressed some reserves concerning the involvement of industry in providing informatio n to patients: http://ec.europa.eu/pharmaforum/docs/final_conclusions_en.pdf. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 36  N. CARBONI industry, should ensure high quality information”12. To recap, the reactions from the non-industry stakeholders in the Pharma Forum show that, although the overall composition of the Forum was not significantly biased in favour of industry, crucial areas such as information to patients were dominated by industry interests. While the final recommendations keep the current ban in place, they also propose allowing the industry to act as a source of information for patients. This creates a loop- hole which finds its way into the Commission’s draft “Pharma- ceutical Package”, allowing industry to publish written infor- mation about prescription medicines in newspapers and maga- zines and on the internet, weakening the advertising ban. It was only because of strong resistance from public health campaign- ers (and Member States) that some degree of protection against advertising of prescription medicines was inserted into the pharmaceutic al p ack age. The Pharmaceutical Package The “Pharma Package”, is the popular name for a series of measures proposed by the European Commission impacting the pharmaceutical industry. It contains three important initiatives plus a Commission communication: a proposal for a directive on how to modernize pharmacovigilance in order to improve safety of medicines; a proposal to improve patient safety by reducing the infiltration of counterfeit medicines into the supply chain (fighting counterfeits); and a directive on the future direc- tion of the supply of health information to patients (the in- formed patient). Among the three legislative proposals, our analysis will especially focus on the information to patients. This proposal was a very controversial issue as it emerged in the Pharma Forum, and which dates back to the Commission’s attempts to review the EU pharmaceutical legislation (Table 4 for a chronological overview). In 200113 the Commission’s Directorate Ge neral Enterprise14 proposed a five-year trial relating to article 88 of Directive 2001/83/EC during which the pharmaceutical industry could direct to a limited extent information to the general public about medicinal products used for the treatment of aids, asthma and diabetes (“Review of the EU Pharmaceutical Legislation”). The European Parliament and Council rejected the proposal. In its report of 9 October 2002 the Parliament objected to direct- to-consumer advertising and considered that the Commission’s proposal would lead to that. Member States were against the proposal as well. Loosening the ban would influence national healthcare systems, since demand is stimulated for those medi- cines that are most advertised. The Parliament was also worried about the circumstance that patients would obtain information about medicinal products but not about other treatments. Therefore, through the same Direc- tive, the Commission was called upon by the EP to analyze the different processes in European countries and to draft proposals, in order to define useful strategies to get good quality, reliable and non promotional information. In the end, the pilot study was rejected and replaced by the request for a report. Parallel to the preparation stage of the review process, the Commission was pursuing also alternative routes for discussion to ensure that the topic remained on the agenda. As we outlined in the previous paragraph, in 2001 the Commission set up the G10 High Level Group on innovation and the provision of medicines, which recommended a public-private partnership on patients information; in 2005 then it established the Pharma- ceutical Forum which again covered the information to patients’ issue. Furthermore, the Commission increased pressure through various public consultations plus impact assessment. Two general web-based public consultations were carried out respectively in 2007 and 2008. The first formal public consulta- tion was about a Draft report on practices with regard to the provision of information to patients on medicinal products, summarising the current state of play without presenting yet any political orientations or proposals; the second public con- sultation specifically addressed the key ideas of the forth-com- ing legal proposal on information to patients. The first part of the consultation received 73 responses, the second one 185 Table 4. Chronological overview o f the Commission’s po lic y proposal on Information to Patients. Date Policy development 2001 Commission’s proposal for loosening ban on d irect-to-consum er advertising of prescr iption drugs 2001-2002 Commission set up the G10 High Level Group on innovation and the provi sion of m edicines 2002 EP and Council re jected the Commission’s proposal 2005-2008 Commission established the High Level Pharmaceutical Forum 2007-2008 Public consu ltations + Impact assessment 2008 Commission legislative proposal on information to patients inclu ded in the Pharma Pa ckage Note: Source : author’s elaboration. 13 The pressure from pharmac eutical industry to promote direct informa ti on to patients actually d ated from t h e mid 1990s. 14DG Enterprise is responsible for drafting pharmaceutical legisla tion. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 37  N. CARBONI Table 5. Overview of the public consultation responses regarding pharmaceutical industry as an information provider about prescription-only medicines. Yes No Mixed No comment Healthcare professi onals and organisations 7 70 15 8 Patient organisations 25 50 10 15 Consumer organization 0 56 44 0 Pharmaceutical industry organisations and companies 96 0 0 4 Regulators 11 46 29 14 Media and patient infor mation organizat i ons 72 14 0 14 Social insurance organisations 0 100 0 0 Research and others 20 30 0 50 Total 26 48 14 12 Note:“Yes” refers to opinions that highlighted the role of a pharmaceutical company as an information provider, because, for example, nobody knows the product better than its producer; “No” refers to opinions that declined the role of a pharmaceutical company as an information provider, because, for example, the information that comes from the producer can not be n eutral; “Mixed” refers to res ponses that accused that there is a l a ck o f a coh e rent d ist in ct ion between advertising and info rmation ; “No com- ment ” refers to responses that did not take out this issue; Source: Summary of the respons es to public cons ultation on th e key elements of a l egal propos al on information to patients was l aunched by the Commission on 5 February, 2008. Source: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/pharmaceuticals/patients/docs/summary_publ_ cons_220508.pdf contributions from the range of relevant stakeholder groups (Table 5). DG Enterprise did pressure until it finally managed to move from High Level discussions requiring consensus to a draft legal proposal on patient information, which was released in December 2008, within the “Pharmaceutical Package”. Through- out all the process DG Enterprise had a clear agenda: allowing the pharmaceutical industry to communicate information to patients. “The Commission doesn’t set out an information strategy but it just provides the pharmaceutical industries greater flexibility to provide information directly to the public on prescription medicines” (Lobbyist, Consumer organization). “We are very much concerned by the Commission legal pro- posal. It gives priority to industrial commercial interests rather than to public health concerns and consumer protection in- terests” (Lobbyist, Health Organization). Before the Pharma Package was released, twenty organiza- tions in the field of health representing patients, consumers, health professionals and social health insurers sent a joint-let- ter15 to both the Health Commissioner Vassiliou and the Presi- dent of the EU Commission Barroso, to express their fears about the draft proposal relating the pharmaceutical package, in particular the role it would have given to the pharmaceutical industry concerning information to patients on prescription- only medicines. “The proposed changes to the existing legislation will have a substantial impact on European patients, consumers and na- tional health care systems. Any attempts to alter the current legislative framework should be guided by and based on an in- depth assessment of patients’ and consumers’ needs… The sig- natories of this letter ask you to continue to lead in defending patients and consumer in the pharmaceutical package and to ensure that public health considerations supersede industrial interests” (Joint Letter to EC President Manuel Barroso, No- vember 2008)16. Member States did not totally welcome the Commission’s proposal as well. Many ministers expressed their concerns over the regulation and directive on the provision of information on medicines by marketing authorisation holders. On 9 June, dur- ing a Health Council meeting in Luxembourg, it became clear that over 20 Member States do not see the proposal as a solid base for negotiations: “While agreeing that there is a need to improve the infor- mation to the general public on prescription-only medicinal products, many delegations fear that the suggested system could be overly burdensome for competent authorities without leading to significant improvements in the quality of the infor- mation provided to patients. In addition, many delegations hold that the distinction between ‘information’ and ‘advertising’ was not sufficiently clear. So they fear that the proposals will not 15Joint open letter to Commissioner Vassiliou on the pharmaceutical package: http://www.epha.org/IMG/pdf/Open_joint_letter_Commissioner_Vassiliou_ 9_November_2008.pdf Letter to EC President Barroso on Pharmaceutical Package November 2008: http:/ /www.age-pl atform.or g/EN/IMG/pd f_phar maceutical_ package.p df 16In the joint letter sent to EC President Barroso, there was also a claim for shifting competence on medicines from DG Enterprise to DG Sanco: “Fi- nally, in order to better ensure that public health considerations are put before i ndustrial i nterests , we call for competence on medicin es to be t rans- ferred from DG ENTERPRISE to DG SANCO, and to become a responsi- bility of the EU Health Commissioner”. Letter to President Barroso on Pharmaceutical Pa ckage November 2008. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 38  N. CARBONI provide adequate guarantees, and that the prohibition of ad- vertising of prescription-only medicinal products to the gen- eral public will be circumvented” (Council Meeting, June 2009)17. This is a controversial issue, as the EP’s information to pa- tients rapporteur says, because: “Many Member States believe that they have the perfect system and they think that more in- formation will drive up health care costs… the Member States are afraid of the costs of the enforcement of the legislation [cfr. the ex-ante checking of the medicine information by health authorities]” (Europolitics, 2009)18. The Committee of the Regions (CoR) was on the same criti- cal wave, blaming that the information to patients proposal was “biased in favour of pharmaceutical companies and would put consumers at risk” (Europolitics, 2009)19. According to CoR rapporteur Susanna Haby (EPP-ED, Sweden), the fact that the package was drafted by Directorate-General Enterprise and Industry and not by DG Health “tells you all you need to know about who is likely to benefit from them” (ibidem). Moreover, she emphasised that the Commission neglected the role of in- dependent local health care professionals when it comes to information to patients on prescribed medicines; in its proposal, the Commission allows pharmaceutical companies to take the lead on patient’s information, but the CoR suggests that this should be done by independent local health care professionals. Coming back to the advocacy groups’ actions, the most of them hardly criticized the not transparent process by which Commission was preparing the legislative proposal about in- formation to patients. It seemed that the Commission had used “soft instruments” (Greer and Vanhercke, 2009), such as con- sultation platforms, to divert public interest advocacy groups’ attention away from the legal proposal drafting process: “It was very bad. Commission was preparing the package while we were engaged in the Pharma Forum. Therefore, it was not very clear who contributed to it. Only one result of the Pharma Forum—the quality criteria—was partially included in the package” (Lobbyst, Health organization). There was actually no link between the topics discussed in the Pharma Forum (relative effectiveness; pricing and reimbur- sement; information to patients) and the legislative policy is- sues proposed in the Pharma Package (pharma-covigilance, fake medicines, information to patients). Only the info to pa- tient issue was partially recalled in the Commission legislative proposals. When we asked the Commission policy officers involved in the process the reasons why the Pharma Forum and the Pharma Package were not linked to each others, and especially why the Pharma Forum was not used to discuss the upcoming Commis- sion legislative proposals, the common answer was that “The Pharma Forum and the Pharma Package were moved by dif- ferent political mandates. Commission is a very fragmented policy house: each DG has its own political mandate and com- munication is not very easy among different Units”. That is to say that the two DGs involved in the policy making process— DG Enterprise and DG Sanco-had respectively their own policy agenda. Moreover, within each DG there are different units and each unit has its own mandate as well. Finally, most of interviewees claimed that “The Pharma Pac- kage was clearly the result of a very strong lobbying, espe- cially from industries. The Commission made the draft proposal circulating before it became official, therefore lobbying started very early in the process.” As a member of the DG Enterprise Cabinet commented, Commission is like “a house of glass. Proposals go out too easily”. The closer you are to the DG responsible for drafting policy proposal, the more chance you have to influence EU policy making process. The Policy Subsystem: Actors, Beliefs, Resources Advocacy Coalitions and Policy Core Beliefs The ACF assumes that stakeholders are primarily motivated to convert their beliefs into policy and then seek allies to form advocacy coalitions to pursue the identified policy objectives. Advocacy coalitions include actors of similar core beliefs who engage in a nontrivial degree of coordination (Jenkins-Smith and Sabatier, 1999: p. 120). Looking at the advocacy groups’ policy positions on the press releases and on the organisations’ website, we can broadly identify20 two main coalitions in our case study. For instance, Table 5, which gathers the results of the public consultation about info to patients carried out by the Commission in 2008, shows at least two coalitions. Coalition A consists of affiliations with pro-industry beliefs (pharmaceutical industry as an information provider), including pharmaceutical industry associations and companies, media and patient infor- mation organisations. Opposing the pro-industry coalition is Coalition B, clearly supporting public health/social protection interests21, that includes healthcare professionals and organisa- tions, patients and consumers groups, regulators, social insu- rance organizations. Among anti-industry affiliations, the strong- est alliance is between health professional and social insurance organizations and consumers groups. Research and patient or- ganizations do not show so clear-cut percentages opposing the role of industry as info provider. As patient groups are funded somehow by pharmaceutical industries, they cannot be totally in opposition with it. Advocac y Coalitions and Usable Resources The pro-industry coalition controls a sizable amount of re- sources. First, coalition A affiliations could count on the finan- cial resources provided mainly by pharmaceutical Industries. Among coalition A members, there are considerable multina- tional pharmaceutical companies able to do effective lobbying on their own. The pro-industry coalition’s beliefs system is also supported by the Directorate Enterprise and Industry of the Commission, which clearly aims to increase European pharma- ceutical industry competitiveness vis-à-vis US industry and harmonize pharmaceutical market in Europe22. In having access to legal authority, Coalition A can offer two relevant resources: 20We decide to polarize advocacy groups in their preferences in order to simplif y the analysis. Howev er, we are aware that more than two coalitions could be identified according to the different degree of convergence/diver- gence between actors’ policy preferences. 21Its policy core belief is “that public health considerations supersede indus- trial interests”, as it was stated in the joint letter about the “Pharma Pack- age” to bo th th e Euro p ean Co mmiss ion er f or Heal th and the Pr esid ent of th e EU Commission Barroso. 17http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/NewsWord/en/lsa/108380.doc 18http://europolitics.abccom.cyberscope.fr/social/council-should-start-discus sing-full-pharma-package-artb252293-26.html 19http://www.europolitics.info/social/cor-considers-executive-s-proposals-bi ased-art2421 80 - 26.htm l Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 39  N. CARBONI skilful leadership and information. Within Coalition A there are advocacy groups driven by charismatic lobbyists, which have been able to build longstanding collaborative and trust-based relationship with the Commission. Commission needs technical information and pharmaceutical industry associations/compa- nies have the resources to provide EU institutions with data, reports, policy analyses and especially evidence-based argu- ments. Compared to Coalition A, Coalition B controls fewer re- sources. At the individual level, coalition B members engage in lobbying activities with varying degrees of financial support. They globally have fewer financial resources than their coun- terparts, but many of them usually get grants and funds from Commission and EU projects. Coalition B has also access to mobilizable members from the health community and Member States. As we have seen in the Pharma Package case study, twenty health organizations sent a joint letter to Commissioner Androulla Vassiliou; the letter was intended to encourage the Commissioner to stand firm with her position towards the Information to Patients part of the Pharma- ceutical Package. Following this, EPHA, working with several EPHA members and other partner organisations, co-signed and sent another letter related to the launch of the Pharmaceutical Package to the President of the European Commission Barroso and the press. The letter warned the College of Commissioners that various parts of the Pharmaceutical Package (Counterfeit Medicines, Pharmacovigilance and Information to Patients) should be reconsidered. It called for the different parts of the Pharmaceutical Package to be unbundled, as the separate parts should be considered individually given that they deal with different issues. More than financial and informational resources, coalition B affiliations base their strength on public and health community support to apply political leverage to the process. Advocacy Coali t i ons and Accessibl e Ven ues Coalition A and Coalition B have been active in several routes. Members of both coalitions were pursuing all the avail- able venues-Commission, EP, Council, but each one seems to have its own preferred channel according to policy preferences, resources, relationship pattern, etc. Whereas industry and some patient groups had good access to DG Enterprise, public health and consumer organizations were considered stakeholders of DG Sanco. Thus, Coalition A and Coalition B have been re- spectively oriented to Directorate of Enterprise and Industry (DG Enterprise) and Directorate for Health & Consumers (DG Sanco). Bearing in mind that the proposals were developed by DG Enterprise, Coalition A had a privileged access to the pro- cess. DG Sanco was not completely able to counterbalance the industry-oriented proposals of DG Enterprise. It was only cre- ated in 1999 with a very limited mandate and without a strong culture compared to the experienced DG Enterprise. Then, pro-industry advocacy coalition was lobbying the Commission more than the EP; conversely anti-industry coal- ition members were pressing MEPs more than Commission’s policy officers. Council is still an undiscovered land for both coalitions, since advocacy groups are still in the stage of learning how to approach this institution (Carboni, 2009). In sum, Coalition A has a comparative advantage in terms of organisational capacity, financial resources and expertise. The position of industries is strengthened by their ability to lobby at all levels of the EU institutional system and by their close rela- tionship to the Commission, who plays a central and strategic role in the policy making process as we see in the next section. Policy Broker and Policy Change The pharmaceutical policy subsystem is polarized between a pro-industry advocacy coalition and an anti-industry advocacy coalition. These coalitions are mainly divided in their policy preferences: Coalition A aims to increase and protect pharma- ceutical industry interests, while Coalition B cares that public health considerations supersede industrial interests. The conflict is mainly driven by normative beliefs, making policy change extremely difficult. As far as now, neither advocacy coalition is totally getting what it really wants. It is just too early in the process to assess whether stakeholders have exhausted all the available venues and resources23. The best option for both coa- litions is a consensus-based approach. In the case examined here, policy learning is observed, as it is predicted by the ACF. Policy learning within and between coalitions is an important aspect of policy change. In this policy subsystem, policy learning globally consists of the widespread of knowledge, scientific and technical information, relationship building, willingness and capacity to compromise. Learning process is most likely to concern only secondary aspects of a belief system, leaving the policy core of a coalition intact, and bringing to minor policy changes (Sabatier, 1998). Minor policy changes are the result of two processes: learning within and learning across coalitions. The second is more interest- ing in this case as it is where policy broker may intervene. Pol- icy brokers play a crucial role within consensual decision-mak- ing systems: they mediate between conflicting interests during political negotiations, control information, and translate diver- gent opinions into co mpromise s. This was mai nly the role play ed by the Commission in this case study: “Commission has played an important role in achieving consensus among different interests. Commission is aware it needs to involve more and more stakeholders in the process. While it is true that everybody has its own interest and it is not neutral (Commission included), the more inclusive the EU process becomes, the more objective it will get” (Lobbyist, Pharmaceutical Industry). 23The legal basis of the info to patients proposal is Article 85 (internal mar- ket) of the Treaty and the procedure is co-decision. Therefore, it requires qualified majority in Council and all the drafts are now at first-reading. The votes on the EP reports are expected in April 2010. While we are writing down all th e i s sues raised here, a si g nificant change occu rs: the new Barros o Commission is planning to move competence for Pharmaceutical policy from the En terp ris e and I ndus try Direct or ate in to t he Healt h an d Con sumers directorate-general. DG Sanco will take charge of drafting pharmaceutical legislation and of decision-making on questions such as product autho- risation. It will also take on responsibility for the European Medicines Agency, as well as for some aspects of biotechnology and pesticides that are to be transferred from the environment department. This institutional change will probably transform “t he rules of the game”. 22“This Communication outlines the Commission’s vision to ensure that European citizens will benefit from a competitive industry that generates safe, innovative and accessible medicines… The pharmaceutical industry contributes to the well-being of citizens through the availability of medi- cines, economic growth and employment. Europe has been losing ground in harmaceutical innovation. It is important to slow down or even reverse this trend” (Commission Communication on the Pharmaceutical Sector, 2008). http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/pharmaceuticals/pharmacos/pharmpack_12_2 008/communication/citizens_summary_communication.pdf Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 40  N. CARBONI The position of broker in policy negotiations depends on the features of the political system and on specific context factors: the higher the degree of consensus required, the more norms of compromise create incentives for broker’s action across coali- tions. In the EU context, the policy making process combines aspects of intergovernmental negotiations and supranational centralisation. The Commission draws up the proposal and a decision has to be taken by Member States in the Council, and in the case of co-decision with the EP. The Commission has to search for consensus, trying to avoid decisions that violate Member States interests. Policy proposals without consensus can be blocked by intergovernmental haggling (Scharpf, 2000). Commission has to strategically pursue all the venues and re- sources available in order to avoid deadlock. By favouring the exchange of information and opinions among stakeholders, building supportive networks, promoting public consultations, it can indirectly influence the policy direction of Member States. In addition, by attending all the meetings in the Council and in the EP, Commission knows the bottom lines of the actors in- volved in the process: the formal and informal institutional avenues leave room for strategic behaviour. Commission as policy broker, therefore, takes an important position, where it can channel information among advocacy groups and influence the final output, behaving as a strategic actor. The role of the policy broker can rest on a continuum ranging from brokerage to advocacy and actors performing this function may inter- mittently switch towards more advocacy oriented-behaviour (Jenkins-Smith and Sabatier, 1993: p. 27). Furthermore, the Commission not only has played the role of broker in the process, but it has also confirmed to be able of being both a policy entrepreneur (Cram, 1997; Laffan, 1997) and a purposeful opportunist (Cram, 1993). The role of the Commission as a policy entrepreneur should not be ignored. In the case of information to patients, the Commission has been able to frame and keep the policy issue on the EU agenda for almost 10 years. Although the Commis- sion’s proposal was initially unsuccessful, the Commission has managed to find a way out of the political impasse (the EP and Council rejection to Commission proposal) by using alternative routes (i.e. the G10 and the Pharma Forum) as a platform to keep issues that were not agreed upon in the review on the po- litical agenda. Despite lack of substantial competences, health has been emerging as a European policy field through many creative avenues (Greer, 2006). This case study shows how EU integra- tion can result from the ability of institutions-especially the European Commission—to use the “material constitution”24 to influence the structure of politics. Even though the Member States provided the EU with limited health competences, ex- cluding harmonization of their laws and establishing the sub- sidiarity principle for health services and medical care, it does have numerous responsibilities relevant to health. Commission as a purposeful opportunist sometimes succeeds in legislating on issues that do not necessarily fall within its mandate. This case-study is clearly the example of how the Commission is able to shape advocacy groups’ strategies and to exploit stake- holders’ resources and critical junctures among institutions. To sum up, plans for reform pharmaceutical legislation had started to take shape inside the Commission already in 2002, following the reject by the EP and the Council. The Commis- sion Directorate General—DG Enterprise initiated and fostered EU high level debates between experts, professionals and Member State governments on patient information. The not transparent approach in inviting stakeholders resulted in an overrepresentation of industrial interests. Furthermore, various and simultaneous routes pursued by the Commission and over- lapping consultations created confusion. It was clear that DG Enterprise had its own agenda-giving patients’ information by industry and successfully lobbied for that. By creating and fos- tering high level debates, the Commission not only favored policy learning, such as sharing experiences, exchange of knowledge, but also managed to create commitment for its goal as building of supporting coalitions. In many policy areas the Commission generally tries to build trust through the creation of supportive and consultative networks with advocacy groups or through increasing (sometimes apparently) the level of transparency and legitimacy by public consultation procedures (Cram, 1997; Héritier, 2007). In conclusion, the key to understand the EU policy change dynamics in health care seems to be the relevant role played by the European Commission throughout all the policy process. Commission as policy broker has favoured policy learning and as part of the advocacy coalition has exerted pressure for policy change as well. Beside the role of policy broker in influencing policy change, the ACF allows us to get some interesting insights about the factors that increase the chances to get policy change within the multilevel system of the EU. Bearing in mind that EU policy making is a consensus-based process, which first of all requires agreement between the institutional players (Commission, EP, Council and Member States), the policy analysis suggests that policy change at the EU level is especially fostered by the fol- lowing factors25 (Figure 1). 1) Accessible venues The institutional setting26 with the Commission, the EP and the Council, each playing a specific role in the legislative proc- ess, offers advocacy groups access points differentiated ac- cording to organizational and informational cost of lobbying (Carboni, 2009). By facilitating or conversely hindering some courses of actions, institutions define opportunities and con- straints for actors’ involvement, influencing the success or fail- ure of the political game. This study shows the central role played by Commission as both policy broker and policy entre- preneur in the policy-making process. Access to policy broker is a strategic venue especially when it takes authority position. However, Commission results in a very fragmented body. Each DG represents a world with its own language and network. It means each DG comes with different treaty bases, different cultures, different stakeholders and consequently different in- terests to push on the policy agenda. In our case, the fact that DG Enterprise controlled pharmaceutical policy instead of DG Sanco resulted in an industry oriented agenda and an easy ac- cess to policy making for pro-industry coalition. 2) Available resources 25We take into account the influence of endogenous variables, controlling for external factors. 26Despite of the increasing role of the ECJ in EU health policy development, we have not included it in the analysis since it has not played a relevant role in the selected case-studies. 24The constitution in the material sense must be distinguished from the constitution in the formal sense, namely a document called “constitution”, which, as written constitution, may contain not only norms regulating the creation of general norms, but also norms concerning other politically im- portant subjects. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 41  N. CARBONI Coalition A Coalition B Polic y Broker Institutions Policy Change Policy bel iefs, resources, venues of influ ence Figure 1. Framework for policy change. Source: Adaptat ion from S a b atier (199 8 ) . Advocacy coalitions’ resources are important elements in shaping and developing EU health policy. The financial re- sources, information, public support, leadership skills, which interest groups have at their disposal, they all influence to some extent the strategies and the chance of success in achieving policy change (Carboni, 2009; Weible, 2007). Above all, inter- est groups’ expertise and capacity to generate knowledge play an important role at the EU level. The analysis has clearly shown the favouring of certain types of knowledge over others: while it is difficult to determine the exact impact of knowledge on the policy change process, the case-study demonstrates that different types and uses of knowledge are essential to achieve policy change outcomes. It is evident that the key to successful lobbying is strongly based on reputation of providing reliable information and knowledge-based arguments according to in- stitutions demands, more than emotional issues. 3) Belief System This analysis shows that industrial interests prevailed over the interests of others. This case makes clear how much Euro- pean Commission controls legislation. The European agenda for pharmaceuticals is a DG Enterprise agenda. The policy core beliefs of DG Enterprise and of the pharmaceutical industry both had a strong focus on creating a competitive European pharmaceutical industry vis-à-vis US industry. Since individu- als’ identities are closely tied to their beliefs, they tend to filter or ignore dissenting information or events that challenge their belief and readily accept information that bolsters their beliefs. The DG with the competence to draft legislation selectively offered access to advocacy groups whose policy preferences were in line with those of the DG. In both the two analysed processes, DG Enterprise gave access and listened to pharma- ceutical companies and associations, more than to public health and consumer groups. The Commission pursued its own agenda without taking into account all the interests. It invested in net- work building and creating alliances with like-minded advo- cacy groups. In other terms, the case study illustrates that the political ide- ology of the institutions influence the receptivity towards the knowledge and evidence brought in the process by advocacy coalitions (Bryant, 2002). In the end, Commission was willing mainly to knowledge and evidence supporting its ideological perspective. Such findings have serious implications for all policy fields. Advocacy groups/coalitions should be aware of the current dominant policy paradigm and the barriers to change that it may present. As our analysis shows, it may be difficult to persuade decision makers of the value of public health interests in developing policy, when the dominant para- digm in health care policy is industries competitiveness. The dominant advocacy coalition in the health policy community, such as pharmaceutical industries, benefit from Commission’s legal proposal to review pharmaceutical legislation and have the ears of government. Similarly pro-industry governments will not be totally receptive to knowledge concerning the social determinants of health policy, whatever the empirical evidence could be. Conclusion This study has attempted to contribute to both theoretical and empirical dimensions concerning EU policy change process, by the application of the advocacy coalition framework developed by Jenkins-Smith and Sabatier to interest representation in health care. On the one hand, the research shows that a public policy ap- proach is useful to analyze in a more dynamic and process- oriented way EU integration. The ACF confirms to be a policy analysis tool, guiding the analyst toward a systematic evalua- tion of the different categorizations of stakeholders’ policy core beliefs, coalition membership, usable resources and accessible avenues. The advocacy coalition approach is conducive to gain insights into the way resource distribution creates dependencies between actors and shapes power relations; it enables the re- searcher to understand how coalitions take shape throughout the process and how resources and venues contribute to coalition activities and policy change. Moreover, it takes us beyond the usual EU-neoliberal approach (Anderson, 2009). ACF allows identifying the nature, extent, and impact of a structural liberal bias in EU health policy-making in a way that neither institu- tions nor multiple streams can, because they tend to hide dif- ferent power resources. Within the ACF, we then add insights about some of the un- derdeveloped components of this theoretical approach, such as policy broker’s role and policy change definition. First, the policy analysis demonstrates that in a consensus-based policy making process—such as the EU joint-decision making system-, where different policy objectives are in competition and a mul- titude of stakeholders interact, a small number of specific actors who facilitate communication and evaluate the different opin- ions in the network are necessary and important. These actors are the policy brokers. Whereas policy brokers take a relevant position controlling over the information and the critical junc- tures of the political subsystem, they do not only mediate among different actors, but they could also behave as strategic actors who pursue their own policy objective. It means that policy brokers not only can favor policy learning, but they can also promote policy change. Second, within the broad definition Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 42  N. CARBONI of policy change, we identify different types of policy change at the EU level: a) policy change as poli cy learning; b) policy change as change of the state of the policy issue; c) policy change as change of the structure of politics. The latter is especially relevant to the theoretical develop- ment of EU integration studies. It is evident from the policy analysis how the “material constitution” gives the chance to EU actors, especially Commission, to change the structure of poli- tics in the long run. In this case, the Commission has been able to bypa ss formal leg islative veto poi nts by using informal aven ues or practises (stakeholders’ consultation processes, public de- bates, informational platforms, etc.). This is a manner to further EU integration process, expanding the EU’s role in fields of Member States’ authority by “ways of doing” rather than “hard law” (Vanhercke, 2009; Greer and Vanhercke, 2009). On the other hand, the study presents a rich picture of the in- tergovernmental praxis in EU health policy landscape. While the findings of the study cannot simply be generalized to all the policy areas, this research presents a detailed account of the nature and way policy-making takes shape at the EU level in a significant policy field. Above all, the empirical analysis illus- trates how relevant is advocacy in producing policy change at the EU level. Lobbying in the multilevel system of the EU is a strategic activity concerning not only the traditional advocacy groups, but even institutions. It is evident from this study that lobbying is a two-way street relationship, a relationship of give and take, a relationship which can be a mutually-beneficial for both sides. Advocacy groups seek to influence outcome in the policy making process by persuading decision makers to sup- port or even champion their cause that would not have done so otherwise. But governmental actors want something from lob- byists too. In order to be successful, you need to lobby institu- tions giving them what they need. They need expertise and technical information for policy development; they press advo- cacy groups to do campaign contributions for them. They ask lobbyists for assistance in attracting support from other institu- tions, from the public or others. These are all cases that emerge from our study. The Commission especially relies on stake- holders’ resources and strategies to exert pressure on national governments and expand its competences in policy fields, such as health, traditionally under Member States subsidiary princi- ple (Mossialos and Permanand, 2005a). Moreover, in this case the Commission has been able to act as “successful lobbyist” in promoting its own policy interest. It has effectively lobbied not only public health and business interest groups, but also the European Parliament and the Council (and Member States) to different degrees. Since almost 10 years from its failed attempt to review EU pharmaceutical legislation, the Commission has managed to bring its policy proposal back in the EU legislative agenda. To conclude, lobbying results in a “successful” way to get policy change in the multilevel system of the EU, where the European Commission plays a pivot role in making a national policy issue th e cen tral core of a European ba ttle. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Scott Greer, Rita Baeten, Liborio Mat- tina and Giliberto Capano who kindly read the preliminary draft of this paper and gave to me precious suggestions and com- ments, and the European Social Observatory (OSE asbl) in Brussels for its support to this research. REFERENCES Anderson, P. (2009) . The new old world. London: Verso. Bryant, T. (2002). Role of knowledge in public health and health pro- motion policy change. Health Promotion Inte rnational, 17, 89-98. doi:10.1093/heapro/17.1.89 Carboni, N. (2009). Advocacy groups in the multilevel system of the EU: A case study in health policy-making. OSE Paper Series, Re- search Paper, 1, 1-35. Cram, L. (1993). Calling the tune without paying the piper: Social policy regulation: The role of the commission in European Union so- cial policy. Policy and Politics, 21, 135-146. doi:10.1332/030557393782453899 Cram, L. (1997). Policy-making and the integration process implica- tions for integration theory. London: Routledge. European Public Health Alliance (2008). Pharmaceutical package: Better but far from perfect. Brussels: European Public Health Alli- ance Press Release. Greer, S. (2006). Uninvited europeanization: Neofunctionalism and the EU in health policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 13, 134-152. doi:10.1080/13501760500380783 Greer, S., & Vanhercke, B. (2009). Healthcare and the EU: The hard politics of soft law. In E. Mossialos, R. Baeten, & T. Hervey (Eds.), Health system governance in Europe: The role of EU law and policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Héritier, A. (2007). Explaining institutional change in Europe. Oxford, OH: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199298129.001.0001 Jenkins-Smith, H. C., & Sabatier, P. (1993). Policy change and learn- ing. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Jenkins-Smith, H. C., & Sabatier, P. (1999). The advocacy coalition framework: An assessment. In P. Sabatier (Ed.), Theories of the pol- icy process (pp. 117-166). B ould er, CO: Westview Press. Laffan, B. (1997). From policy entrepreneur to policy manager: The challenge facing the European Commission. Journal of European Public Policy, 4, 422-438. doi:10.1080/13501769780000081 Lamping, W. (2005). European integration and health policy: A pecu- liar relationship. In M. Steffen (Ed.), Health governance in Europe: Issues, challenges, and theorie (pp. 18-48). London: Routledge. Leibfried, S., & Pierson, P. (2000). Social policy. Left to courts and markets? In H. Wallace and W. Wall ace (Eds.), Policy-making in the European Union (pp. 273-293). Oxford, OH: Oxford University Press. Mossialos, E., Permanand, G., Baeten, R., & Harvey, T. (2009). Health systems governance in Europe: The role of EU law and policy. Cam- bridge, MA: Cam bridge University Press. Mossialos, E., & Permanand, G. (2005a). Constitutional asymmetry and pharmaceutical policy-making in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 12, 687-609. doi:10.1080/13501760500160607 Mossialos, E., & Permanand, G. (2005b). The europeanization of regu- latory policy in the EU pharmaceutical sector. In M. Steffen (Ed.), Health governance in Europe: Issues, challenges and theories (pp. 49-80). London an d Ne w Y ork: Routledge. Sabatier, P. (1998). The advocacy coalition framework: Revisions and relevance for Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 5, 98-130. doi:10.1080/13501768880000051 Sabatier, P. A., & Weible, C. M. (2005). Comparing policy networks: Marine protected areas in California. Policy Studies Journal, 33, 161-180. Scharpf, F. (2000). Institutions in comparative policy research. Com- parative Political Studies, 33, 762-790. doi:10.1177/001041400003300604 Smith, A. (2000). Policy networks and advocacy coalitions: Explaining policy change and continuity in UK industrial pollution policy? Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 43  N. CARBONI Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 44 Brighton and Hove: Uni ve rsity of Sussex. Vanhercke, B. (2009). Against the odds. The open method of coordina- tion as a selective amplifier for reforming Belgian pension policies. In S. Kröger (Ed.), What we have learnt: Advances, pitfalls and re- maining questions in OMC research (pp. 1-18). European Integration online Papers. http://eiop.or.at/eiop/texte/2009-016a.htm Vogt, W. (1999). Dictionary of statistics and methodology: A nontech- nical guide for the social sciences. L ondon: Sage . Weible, C. M. (2007). An advocacy coalition framework approach to stakeholder analysis: Understanding the political context of Califor- nia marine protected area policy. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 17, 95-117.

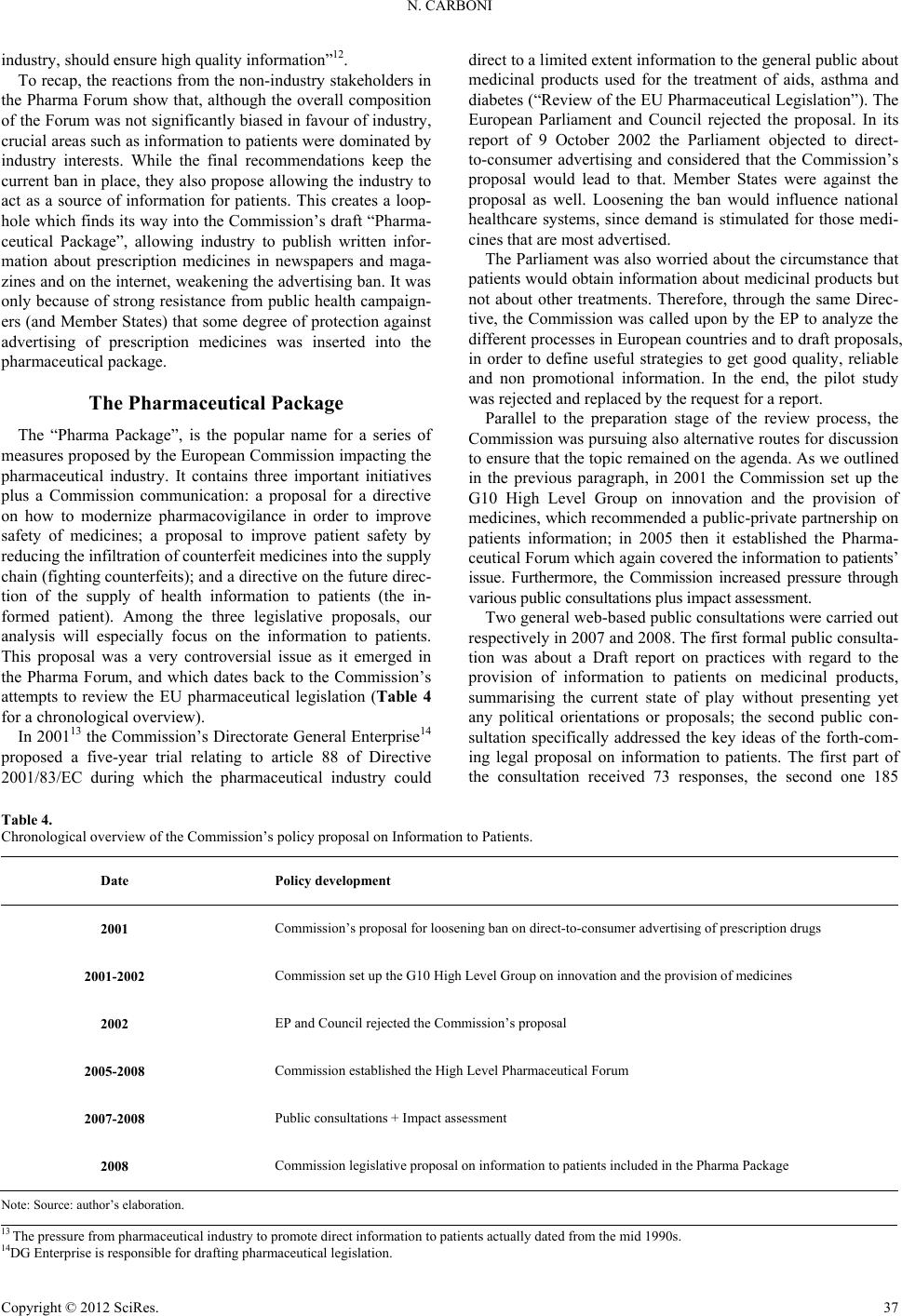

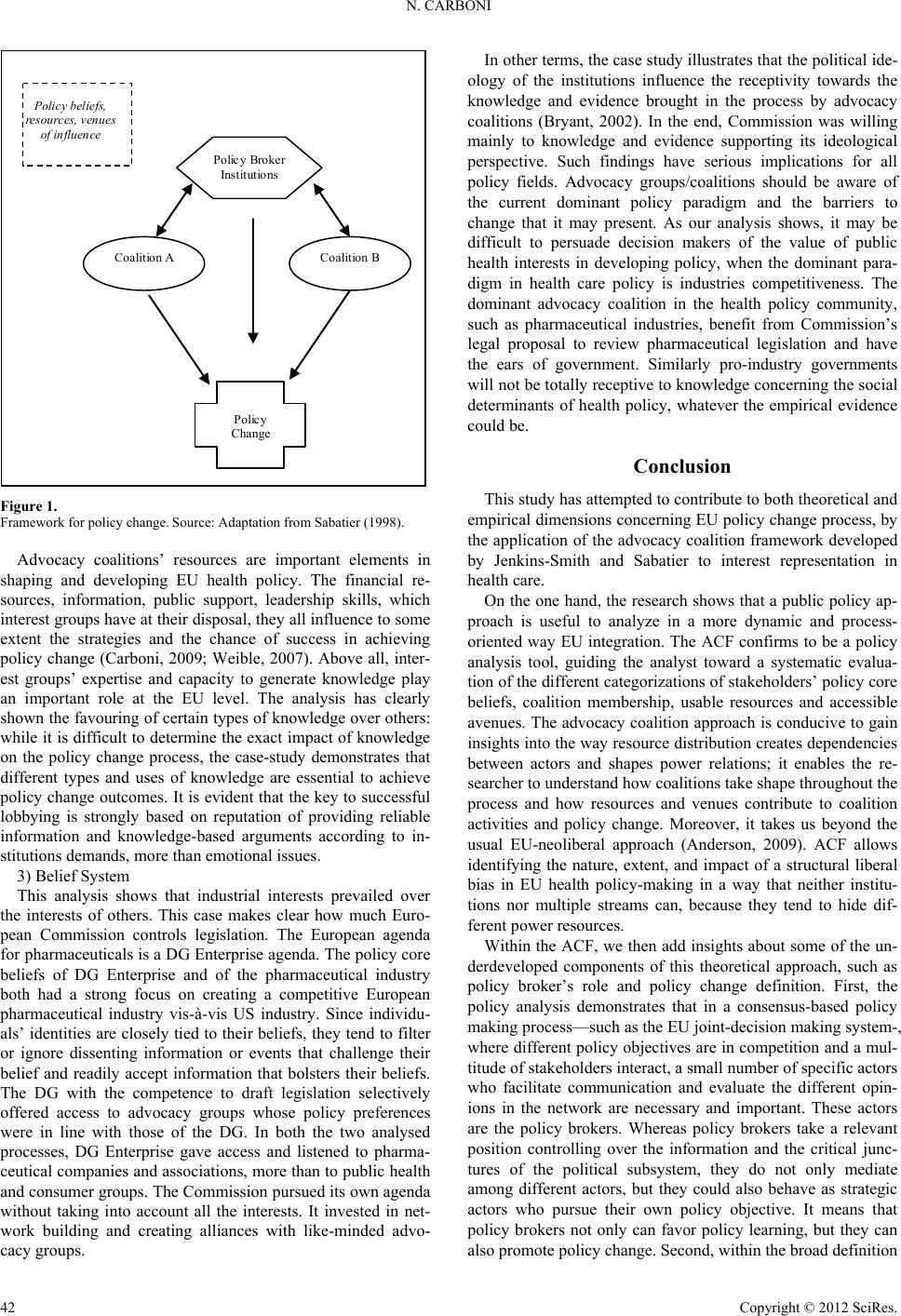

|