Journal of Cancer Therapy, 2012, 3, 755-767 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jct.2012.325095 Published Online October 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jct) 755 The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Mammary Neoplasms: A Brief Review Leonardo Della Salda, Mariarita Romanucci Department of Comparative Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Teramo, Italy. Email: ldellasalda@unite.it Received July 13th, 2012; revised August 15th, 2012; accepted August 26th, 2012 ABSTRACT Research into heat shock proteins (HSPs) for the clinical management of tumours has intensified as new evidence shows they can be used as biomarkers in carcinogenesis and are related to poor prognosis in some cancer types. Mem- bers of small HSP, HSP70 and HSP90 families have been studied extensively in breast cancer. This article reviews cur- rent understanding of the role of HSP and HSF-1 (Heat shock factor 1) expression in human breast cancer and looks at its potential diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic value. The exciting progress that has been made using HSP 90 in- hibitors in breast cancer treatment is examined and the results of preliminary studies on the expression of stress proteins in the animal model canine mammary tumours are also presented. Keywords: Cancer; Stress Proteins; Stress Response; Mammary Tumour; Heat Shock Proteins 1. Introduction Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are a highly conserved class of proteins normally expressed at low levels by all known eukaryote and prokaryote cells [1]. Their induction is mainly dependent on the activation of heat shock factor 1 (HSF-1) and its interaction with heat-shock regulatory elements (HSEs) present in the promoters of all HSP genes. HSPs are classified into several families accord- ing to their approximate molecular weight although a new nomenclature has recently been proposed [2,3]. HSPs often act in concert, in large multiprotein complexes known as molecular chaperones guiding the normal fold- ing, intracellular disposition and proteolytic turnover of many of the key regulators of cell growth, differentiation and survival [4]. However, these functions are altered in oncogenesis allowing malignant transformation [5] with upregulation of stress-related genes and increased syn- thesis of intracellular and extracellular HSPs [6]. This results in HSPs being tumour-protective through mecha- nisms such as anti-oxidative processes, the prevention of protein denaturation, anti-apoptotic activity, and possibly the direct suppression of the immune system [7]. It has also been shown that stress proteins, including HSP70, participate in the folding of numerous protooncogene and oncogene products [8]. Small HSP, HSP70 and HSP90 families are involved in the regulation of oestrogen receptors (ER) and hence have been extensively studied in human breast cancer where they play a role in tumour cell proliferation, dif- ferentiation, invasion, metastasis, cell death and tumour immune response [9,10]. In particular, HSP27 and HSP70 have been shown to exert a pro-malignant effect in breast cancer, by blocking programmed cell death and se- nescence, while HSP 90 fosters the accumulation of mutated or overexpressed oncoproteins. Elevated expres- sion of HSPs has also been observed in canine mammary tumours [11,12] and given that these tumours share many of the epidemiological, clinical-pathological and biochemical features of human breast cancer, study of the canine model may prove useful in understanding the mo- lecular mechanisms involved in mammary carcinogene- sis [13,14]. 2. The Role of HSPs in Mammary Tumour Cell Proliferation As mentioned earlier, recent data have shown that chap- erones facilitate the malignant transformation of mam- mary cells at a molecular level and their altered utiliza- tion during oncogenesis is critical in the development of human breast cancer [15]. The expression of HSPs in breast cancer is correlated with increased cell prolifera- tion and it has been shown that selective depletion of several HSPs results in activation of the apoptotic event [16]. Multi-protein complexes containing isoforms of HSP70 and HSP90 and other HSPs or molecular cofac- tors such as CDC37, P23, CHIP, Tah1, Pih1p and im- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Mammary Neoplasms: A Brief Review 756 munophilins [17,18], have been shown to play an impor- tant role in the regulation of the cell cycle, controlling the activity of several signalling proteins [19], especially cyclins [20] and retinoblastoma protein (pRb), by bind- ing to these clients and regulating their stability and function [21]. This interaction is transient in nature and driven by rounds of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) hy- drolysis [22]. The high expression of the HSP72/73 in nucleus of canine mammary tumour cells characterised by intense proliferation activity and in mitotic cells cor- roborates the roles exerted by these chaperones in cell cycle control and in regulating the assembly of mitotic apparatus [12]. HSP90 client proteins include known substrates that are key components of the cellular apop- totic and signal transduction pathways involved in breast tumour (Wnt, ErbB and Notch), such as mutated p53, Bcr-Abl, HER2/Neu (ErbB2) and HIF-1α [23] steroid hormone receptors, Raf-1, Wee-1 and serine/threonine and tyrosine protein kinases (e.g. Akt kinases), which are critically dependent on HSPs for their maturation and conformational maintenance [24,25] (Figure 1(a)). HSP27 and heat shock transcription factor 1 (HSF-1) have been shown to specifically interact with betacatenin, a pivotal member of molecular pathways involved in tumour cell survival [26]. HSF-1 plays a key role in the development of tumours associated with activation of Ras or inactiva- tion of p53 and is also critical in the proliferation of HER2-expressing breast cancer cells, probably because it maintains the levels of HSPs (HSP72 and HSP27 in par- ticular), which in turn control regulators of senescence p21 and survivin [27]. HSPs inhibit apoptosis by func- tioning at multiple points in the apoptotic signalling pathways, modulating both intrinsic and extrinsic path- ways [28-30]. HSP27 binds to cytocrome c [31] whilst HSP70 and HSP90 bind to Apaf-1 preventing caspase 9 maturation [32]. In contrast, HSP60 and HSP10 promote the direct proteolytic maturation of caspase 3 (proapop- totic function). HSP27 inhibits the Daxx apoptotic path- way [33], while HSP70 binds to JNK1 resulting in inhi- bition of JNK activation. HSP90 interacts with RIP 1 kinase and AKT [34,35] resulting, in both cases, in the promotion of NF-κB mediated inhibition of apoptosis. A similar pattern of change in HSP70, HSP90 and caspases 3 and 8 or other apoptosis-associated proteins, such as Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, Bax, in both human and canine mam- mary tumours has also been demonstrated [11]. A direct relation between HSPs and BRCA1 (BReast-CAncer susceptibility gene 1) was also highlighted when a DU- 145 cell culture expressing exogenous wild-type BRCA1 (wtBRCA1) showed two to four-fold increased expres- sion of the HSP27 [36]. Breast cancer metastasis sup- pressor 1 (BRMS1), a protein that suppresses metastasis in multiple systems without blocking tumour genesis, is stabilized by the HSP40, -70, and -90 chaperone complex [37]. 3. Diagnostic and Prognostic Implications of HSP Expression in Mammary Cancer HSP expression in breast cancer has been analyzed in relation to the histopathological characteristics of tumour tissues e.g. tumour type, grade of differentiation, degree of proliferation and patient parameters [38-43] but this has not proved to be particularly informative on a diag- nostic level and cannot be relied upon for the recognition of a specific tumour histological type also in canine mammary tumors [12]. HSP27 expression has been extensively studied given its relationship with a cytosolic oestrogen receptor-asso- ciated protein, its physiological role in the assembly and trafficking of steroid receptors and correlation with oes- trogen receptor levels [44,45]. However this protein has not been associated with progesteron receptor in female cancers or with ERα in male breast carcinomas [46,47]. In addition, other findings indicate that not all ER-posi- tive breast tumours express HSP27 [44]. It has been re- ported by some authors that there is no significant or marginal correlation between HSP27 expression and his- tological grade or with the proliferation marker ki-67 [48] in well differentiated tumours, however other au- thors have reported that HSP27 can be directly correlated to the grade of differentiation both in human and canine breast tumour [12, 49,50]. In breast cancer the increased expression of HSP27, apart from the transcriptional acti- vation via HSF-1, is directly and indirectly (via inter- action with the oestrogen receptor) activated by Brn-3b POU transcription factor [51], which is responsible for an increased growth rate and higher proliferative activity in mammary cancer cells [52]. Clinical-pathological studies have shown that the in- ducible form of the HSP70 family (HSP72) is associated with poor differentiation and the presence of mutated p53 in breast cancers [53], and its nuclear staining pattern has been reported to be correlated to tumour size [54]. A strict correlation between HSP70 levels and increased oestrogen receptors has also been detected [53]. Signifi- cant increases in HSP27 and HSP70 in its inducible form have also been observed in canine mammary tumour, particularly in the more invasive neoplastic cells, there- fore these proteins (and HSP90) play a meaningful role in the multiple processes leading to malignant transfor- mation and tumour progression in the canine mammary gland [12]. Over-expression of the glucose-regulated stress gene GRP78 has been observed in most of the more aggressive ER-tumours but not in benign human breast lesions [55]. HSP90 is a fundamental component of the steroid re- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Mammary Neoplasms: A Brief Review 757 ceptor complex and is positively related to ER and c-erbB-2 and appears to be expressed more in poorly differentiated carcinomas [56], while a significantly de- creased HSP90 expression has been observed in tri- ple-negative tumours and seems not to be triggered in precursor and pre-invasive lesions [57]. This HSP also seems to be involved in the prolifera- tion of human breast cancer as levels of HSP90α, appear to be positively correlated to cyclin D1 expression in this type of tumour [20]. HSP27 cannot be considered a useful prognostic factor in breast cancer [58] as numerous studies have produced conflicting results. In fact, even though the positive link with ER suggests a correlation between high levels of HSP27 and a better prognosis, an association between HSP27 over-expression and more aggressive tumours has also been detected, particularly in the early stages of breast cancer [41]. HSP27 levels have been correlated to different bio- logical features in early and advanced breast cancer, be- ing linked with short disease-free survival (DFS) in node-negative patients but with prolonged survival from first recurrence [38,45,48]. In fact high expression of HSP27 gene has been found to be associated with in- creased anchorage-independent growth, invasion, metas- tasis and resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs [51,59]. A similar correlation between HSP27 expression and tu- mour invasiveness, in association with reduced overall survival (OS) has also been observed in malignant canine mammary neoplasms [12], supporting the theory that HSP27 overexpression may influence the invasive and metastatic potential of both canine and human breast cancer cells [14]. It was thought that high levels of HSP27 in advanced cancer were indicative of long sur- vival because of the link with hormone response; how- ever, the biological explanation for the switch from HSP27 being a bad to good prognostic factor in early and advanced breast cancer remains to be defined. Moreover, HSP27 seems to sort out cases with a better prognosis from the ER negative group of patients, with a poor prognosis [60]. Nevertheless, subsequent other studies have failed to detect a correlation between HSP27 ex- pression and response to hormone therapy or with DFS or OS [61]. High expression of Hsp 27 and HSP70 in breast cancer correlates with lymph node involvement [48,62-65]. The surface expression of HSPs differ- entially regulates metastasis; murine breast carcinoma cells sorted for high HSP25 (the murine homologue of human HSP27) surface expression metastasized to the lungs more aggressively than wild-type HSP25 cells and HSP72 positive cells [6]. αß-crystallin (small HSP family) expression is also closely tied to lymph node involvement, and increased intensity has been correlated to shorter survival [66]. High stress-inducible HSP70 (HSP72) expression is correlated to poor prognosis in breast cancer [54,62,67], in particular with nuclear non- cytoplasmatic localization [68]. This is consistent with the association of HSP70 with some of the diagnostic parameters of malignancy (poor differentiation, lymph node metastasis, increased cell proliferation, block of apoptosis, and higher clinical stage) [64]. Investigations into the genetic polymorphism of HSP genes indicate that homozygosity for HSP70-2 genes is significantly associated with increased OS but not with DFS in breast carcinoma [67,69]. HSP90 expression in breast cancer tissues [20] and the presence of auto-antibodies to HSP90 have been correlated with poor prognosis in breast cancer [70,71]. In canine malignant mammary tumours, HSP70 and HSP90 do not appear to be of sig- nificant prognostic value but the high levels of HSP90 expression detected in neoplastic tissues, independently of tumour histological type or aggressiveness, suggest that this protein plays a fundamental role in malignant transformation and tumour progression in the canine mammary gland [12]. 4. Predictive and Therapeutic Implications of HSP Expression in Mammary Cancer A growing body of evidence suggests that high intracel- lular HSP27 and HSP70-family expression may render mammary tumours resistant to a number of chemothera- peutic agents [72,73] which is of relevance in treatment management. However it should not be forgotten that chemotherapeutic drugs can also induce their expression as part of the cellular stress response, thus potentially increasing cancer cell resistance by up-regulating anti- apoptotic factors [74]. Although the expression of HSP27 has been correlated to ERalpha in breast cancer, its de- tection does not predict response to Tamoxifen. Over- expression of HSP27 has been correlated to shorter DFS in advanced breast cancer patients who received neoad- juvant chemotherapy [68]. In contrast, HSP70 is emerg- ing as a predictor of resistance to chemotherapy in breast cancer [62], but, like HSP27, it has not shown predictive value for Tamoxifen administration [61]. Moreover, high HSP70 levels have been correlated to lower response of breast cancers to radiation and hyper- thermia [75]. The use of HSPs in the treatment of breast cancer represents a new and very promising approach. Treat- ment of tumour cells with a synthetic inhibitor of HSP27 phosphorylation [30,76], as well as knocking down using transfection with short interference RNA [76,77], has been found to block tumour cell migration. Many studies have tried to establish whether HSP90-binding drugs can effectively destabilize and reduce oestrogen receptor levels, which are a prominent target for the treatment of Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Mammary Neoplasms: A Brief Review Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT 758 hormone-dependent cancer which has become refractory to classical hormonal therapy with anti-oestrogen agents [21,78]. Agents such as geldanamycin (GA) or the GA analogous 17-allylamino, 17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG) have been shown to inhibit HSP90. 17-AAG is an aminoquinone macrocyclic compound; it shares the same ability of geldanamycin to bind to HSP90 and GRP94. These drugs target the nucleotide-binding site in the N-terminal domain of HSP90, disrupt p23 containing HSP90 complexes preventing it from binding to client proteins [34], like the inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) Survivin [79]. Other products such as herbimycin A, purine-scaffold derivatives, the peptidomimetic shep- herdin (specifically designed to block the interaction between HSP 90 and Survivin) and the natural macrolide radicicol inhibit HSP90 function by binding to the same pocket [80,81]. Novobiocin, a cumarin-type antibiotic acts in vivo and in vitro in a similar but unique manner: it binds the C-terminal domain of HSP90 [82] and disrupts both HSP90-HSP70-p60hop and HSP90-p50-p23 com- plexes [83]. When GA binds to HSP90 it locks the chap- erone in an alternative conformation that prevents normal cycling and the formation of mature chaperone com- plexes. The HSP90 client ER accumulates in an interme- diate complex that recruits E3 ubiquitin ligase and drives proteasome-mediated degradation of the protein, thereby dramatically lowering cellular levels of the receptor and disrupting its function (Figure 1(b)). 17-AAG has a Figure 1. (a) Even though it is still not completely understood how HSP90 chaperone complexes recognize their substrates or affect their conformation, a widely accepted model for a steroid hormone receptors is shown (in this case oestrogen receptor). The current understanding of this complex indicate that generally the HSP90 complex holds the receptor (CBP: client bound protein) in an intermediate state until the cognate hormone (L) enters the cell, but oestrogen receptor does not require con- tinuous interaction with the Hsp90-based chaperone machinery to maintain a high affinity hormone binding conformation. The client protein initially interacts with the “open” state of the HSP90 dimer and other co-chaperones, then, ATP binding leads to conformational changes of HSP90, which includes the transient dimerisation of the N-terminal domains and the re- placement of HOP by p23 and immunophillins, converting the chaperone complex into a mature state. Upon hormone bind- ing and ATP hydrolysis, the hormone receptor is released from the HSP90 complex and the hormone is translocated into the nucleus, where it binds specific DNA elements and activates transcription. CyP-40: cyclophilin of 40kDa; HIP: HSP70-bind- ing cochaperone; Hop: HSP-organizing protein; (b) Inhibition of ATP binding to HSP90 prevents the formation of the ma- ture state and results in the proteasome-dependent degradation of associated client protein. This can occur by the recruit- ment of E3-Ubiquitin ligase, CHIP (carboxy -terminus of HSP70-interacting protein), which is a protein able to interact with both HSP70 and HSP90. Geldanamycin and its derivatives exert their anti-tumour effect by binding to the N-terminal AT- Pase domain of HSP90 to inhibit its chaperone function; other molecules interact with the N or C-terminal domain of HSP90 with similar effects.  The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Mammary Neoplasms: A Brief Review 759 100-times higher affinity towards the tumour-specific HSP90 complexed by a large number of co-chaperones than to the HSP90 dimer, which is the predominant form of this chaperone in normal cells [84]. However prefer- ential GA binding has been questioned by a more recent study that also indicated time-dependency for GA bind- ing [85]. Chaperone-based inhibitors offer the advantage of diminishing the level of many protein targets in parallel. 17-AAG, by simultaneously and durably inhibiting multiple signalling activators including ErbB and Src kinases, does not permit the re-activation of signalling pathways by one or more redundant upstream activators (“oncogene switching”) and results in a more prolonged and robust inhibition of downstream signalling path- ways in breast cancer cells than do individual tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as gefitinib, which appear to lose the ability to modulate ErbB-driven signalling pathways over time [86]. It has also proved of use in the treatment of trastuzumab-resistant ErbB2-overexpressing tumours [87]. The anti-pro-liferative effect of 17-AAG posi- tively correlated with phosphorylation and downregula- tion of ErbB2 with a marked increase in apoptosis, al- though, necrosis was also present especially at higher doses [88]. A second more soluble and less hepatotoxic generation analogue of GA is 17-(dimethylaminoethy- lamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-DMAG) [89]. In vivo and in vitro, 17-DMAG exerts anti-angiogenic activity interfering with HSP90 chaperone performance on VEGF induced expression in endothelial cells, and regulating HIF-1α activation [90]. Clinical development of the geldanamycin derivatives 17-AAG and 17-DMAG was discontinued some time ago [15,91-97]. In phase I trials, 17-DMAG [98,99] exhibited an unfavourable toxicity profile. Clinical trials have been done with an optimized 17-AAG formulation KOS-953 (Tanespimy- cin) being used alone and in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents [100]. The wide array of HSP90 inhibitors and their clinical applications have been re- viewed extensively elsewhere [97,101-106], and a sum- mary of trials currently in progress provided by the US National Cancer Institute is available at the web page http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=hsp90+inhibito r&pg=1. It would appear that combination therapies, using low doses of HSP90 inhibitors together with conventional chemotherapeutic agents (such as Taxol), are an effective means of targeting some cancers [96,107-116]. How- ever at this stage it is difficult to predict which patients could benefit from anti HSP90 therapy. In vivo testing of HSP90-targeted cancer therapy is essential as potential contraindications have arisen: 17-AAG appears to en- hance bone metastasis of a human breast cancer cell line following intracardiac inoculation in the nude mouse [117] and paradoxically it may also cause the transcript- tional activation of HSF-1 by disrupting HSP/HSF-1 complexes and thus an increase in the overall amounts of HSP 40, HSP70 and HSP90 [35]. Small synthetic HSP90 inhibitors based on a purine scaffold have been developed which interact with the N-terminal ATP pocket, and produce biological effects similar to geldanamycin. Some of them are under ad- vanced preclinical investigation and CNF-2024, a 9- benzyl purine derivative, has entered Phase I clinical trials in advanced breast cancer [118]. Another novel small-molecule inhibitor of HSP90 based on the 4,5-diarylisoxazole scaffold (NVP-AUY922) in- hibits HSP90 in vitro and exhibits potent anti-tumour activity at tolerated doses in an ER- and ErbB2-posi- tive human breast cancer model [119]. A summary of the HSP90 inhibitors clinical trials currently in prog- ress is provided by the US National Cancer Institute (http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=hsp90+inhibitor &pg=1). A different approach to inhibiting HSP90 function is disrupting its interaction with co-chaperones, such as HOP (HSP organizing protein) [120] or AHA1 (activator of HSP90 ATPase) [121]. Treatment of human breast cancer cell lines with these compounds results in a drop in—the levels of the HSP90- dependent client protein HER2, or in an increase in sen- sitivity to 17-AAG with consequent cell death. Treatment with hydroxamic acid analogue pan-HDAC inhibitors (HA-HDI) induces HSP90 hyperacetylation, this inhibits its chaperone function decreasing its binding to ERalpha, and sensitizes ERalpha-positive breast cancer cells to Ta- moxifen [122]. Inhibition of cell-surface HSP90 with antibodies or cell-impermeable HSP90 inhibitors blocks cell motility and invasion in vitro and cancer metastasis in vivo [123]. HSF-1, HSP27, HSP70, and GRP78 are also the tar- gets of antisense oligonucleotide therapies [10]. All ele- ments of the HSF-1 activation and down regulation cas- cade and Ralbinding protein 1, tubulin and p23 are of great interest as potential drug targets [35]. Chemical inhibitors of HSF-1 activation (genistein, KNK437 and Triptolide) are in a very early stage of development but their effective- ness in breast cancer treatment has yet to be proven [106,124]. When located in the extracellular space or on the plasma membrane, HSPs may provide a target for im- munotherapy protocols because they are able to chaper- one tumour antigens and act as biological adjuvants to break immune tolerance to tumour antigens causing tu- mour regression [125,126]. The immunoregulatory func- tions of HSPs are represented by the ability of such chaperones to bind to several tumour-associated pep- tides/proteins. These complexes can be recognized by Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Mammary Neoplasms: A Brief Review 760 specific receptors on the surfaces of antigen presenting cells confirmed to be CD40 or CD91 (also known as a2-macroglobulin receptors which act as global receptors for HSPs) and cell processed. The purpose is to elicit a specific immune response against its own tumour using tumour-derived HSPs (mainly gp96, HSP70, HSP90 and calreticulin) covalently binding to specific tumour pep- tides—i.e. tumour antigen mucin (MUC1) derived pep- tides [127]—as natural adjuvants that present to the im- mune system the molecules that have shielded the poten- tial epitopes from immune recognition [30,128]. Pre- clinical studies have been conducted to design a variety of novel HSP-based tumour vaccines with improved therapeutic potential: a reproducible anti-tumour re- sponse has been reported in approximately 50% of sub- jects studied [129,130]. These approaches include de- velopment of HSP fusion proteins and genetic vaccines using plasmid DNA and adenoviruses [126]. This topic has been reviewed in detail [126,131,132]. Studies have demonstrated that such active-specific immunotherapy has potential for controlling mammary tumour progress- sion. BALB/c female mice vaccinated with a repeat beta-hCG C-terminal peptide carried by mycobacterial HSP65 induced high avidity antibodyies and effectively inhibited the growth of EMT6 mammary tumour cells injected subcutaneously [125]. Smith et al. (2008) [130] have recently demonstrated that perioperative vaccina- tion with an ex vivo HSP-loaded dendritic cell vaccine abrogated recurrent tumour growth in an in vivo model of breast-conserving surgery for breast cancer (BALB/c mice). Finally, the differing expression of HSPs in mammary carcinomas and conflicting results may be the result of the complex array of genetic (derepression/repression of specific genes) and epigenetic (methylation of genes) alterations that characterizes the process of carcinogene- sis and its intrinsic genetic instability. Recent studies have implicated HSP90 in transcriptional regulation de- monstrating an important role for it in buffering genetic and epigenetic variation leading to altered phenol-types. It cooperates with Trithorax (a TrxG chromatin protein) maintaining the active expression state of targets like the Hox genes [133]. Aberrant expression of Hox genes is related to the development of breast cancer and the ma- lignant behaviour of cancer cells, and the expression of HoxC5 is lower in cancerous tissues with mutated-type p53 than in normal and cancerous tissues with wild-type p53 [134,135]. Pharmacological inhibition of HSP90 results in degradation of Trx and a concomitant down- regulation of homeotic gene expression [133]. 5. Conclusions Studies on this subject clearly indicate that intracellular and extracellular HSPs play a significant role in the bio- logical and clinical aspects of mammary cancer. Al- though of no particular significance on a diagnostic level, HSP27 and HSP70 are, however, useful biomarkers for carcinogenesis and can predict response to some anti- cancer therapies. HSP90, on the other hand, represents a promising target for the treatment of breast cancer. Major advances have been made in recent years in understand- ing the complex structural and functional relationship between HSPs and their co-chaperones, and identifying client proteins in breast cancer. Currently the potential of HSP90 inhibitors, that have proven to be effective in killing cancer cells, lies in pro- longed disease stabilization. Further study will help iden- tify novel HSP90 N- terminal-ATPase inhibitors or more sophisticated drugs capable of taking advantage of the immunogenic properties of extracellular HSPs. 6. Acknowledgements We would like to thank Tania Bastow for the linguistic review of the manuscript. REFERENCES [1] W. J. Welch, “Mammalian Stress Response: Cell Physi- ology, Structure/Function of Stress Proteins, and Implica- tions for Medicine and Disease,” Physiological Reviews, Vol. 72, No. 4, 1992, pp. 1063-1081. [2] H. H. Kampinga, J. Hageman, M. J. Vos, H. Kubota, R. M. Tanguay, E. A. Bruford, M. E. Cheetham, B. Chen and L. E. Hightower, “Guidelines for the Nomenclature of the Human Heat Shock Proteins,” Cell Stress & Chap- erones, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2009, pp. 105-111. doi:10.1007/s12192-008-0068-7 [3] D. Whitley, S. P. Goldberg and W. D. Jordan, “Heat Shock Proteins: A Review of the Molecular Chaperones,” Journal of Vascular Surgery, Vol. 29, No. 4, 1999, pp. 748-751. doi:10.1016/S0741-5214(99)70329-0 [4] K. Helmbrecht, E. Zeise and L. Reinsing, “Chaperones in Cell Cycle Regulation and Mitogenic Signal Transduction: A Review,” Cell Proliferation, Vol. 33, No. 6, 2000, pp. 341-365. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2184.2000.00189.x [5] H. M. Beere, “Death versus Survival: Functional Interac- tion between the Apoptotic and Stress-Inducible Heat Shock Protein Pathways,” Journal of Clinical Investiga- tion, Vol. 115, No. 10, 2005, pp. 2633-2639. doi:10.1172/JCI26471 [6] M. A. Bausero, D. T. Page, E. Osinaga and A. Asea, “Surface Expression of HSP 25 and HSP72 Differentially Regulates Tumor Growth and Metastasis,” Tumour Biol- ogy, Vol. 25, No. 5-6, 2004, pp. 243-251. doi:10.1159/000081387 [7] K. Laudanski and D. Wyczechowska, “The Distinctive Role of Small Heat Shock Proteins in Oncogenesis,” Ar- chivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis (Warsz), Vol. 54, No. 2, 2006, pp. 103-111. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Mammary Neoplasms: A Brief Review 761 doi:10.1007/s00005-006-0013-3 [8] C. Soti and P. Csermely, “Molecular Chaperones in the Etiology and Therapy of Cancer,” Pathology Oncology Research, Vol. 4, No. 4, 1998, pp. 316-321. doi:10.1007/BF02905225 [9] S. E. Conroy and D. S. Latchman, “Do Heat Shock Pro- teins Have a Role in Breast Cancer?” British Journal of Cancer, Vol. 74, No. 5, 1996, pp. 717-721. doi:10.1038/bjc.1996.427 [10] D. R. Ciocca and S. K. Calderwood, “Heat Shock Pro- teins in Cancer: Diagnostic, Prognostic, Predictive, and Treatment Implications,” Cell Stress & Chaperones, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2005, pp. 86-103. doi:10.1379/CSC-99r.1 [11] R. Kumaraguruparan, D. Karunagaran, C. Balachandran, B. M. Manohar and S. Nagini, “Of Human and Canines: A Comparative Evaluation of Heat Shock and Apoptosis- Associated Proteins in Mammary Tumours,” Clinica Chi- mica Acta, Vol. 365, No. 1-2, 2006, pp. 168-176. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2005.08.018 [12] M. Romanucci, A. Marinelli, G. Sarli and L. Della Salda, “Heat Shock Proteins Expression in Canine Malignant Mammary Tumours,” BMC Cancer, Vol. 6, 2006, p. 171. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-6-171 [13] E. Antuofermo, M. A. Miller, S. Pirino, J. Xie, S. Badve and S. I. Mohammed, “Spontaneous Mammary Intraepi- thelial Lesions in Dogs. A Model of Breast Cancer,” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, Vol. 16, No. 11, 2007, pp. 2247-2256. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0932 [14] M. Romanucci, T. Bastow and L. Della Salda, “Heat Shock Proteins in Animal Neoplasms and Human Tumours—A Comparison,” Cell Stress & Chaperones, Vol. 13, No. 3, 2008, pp. 253-262. doi:10.1007/s12192-008-0030-8 [15] R. Bagatell and L. Whitesell, “Altered HSP90 Function in Cancer: A Unique Therapeutic Opportunity,” Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, Vol. 3, No. 8, 2004, pp. 1021-1030. [16] J. Nylandsted, K. Brand and M. Jaattela, “Heat Shock Protein 70 Is Required for the Survival of Cancer Cells,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Vol. 926, 2000, pp. 122-125. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05605.x [17] J. Buchner, “HSP90 & Co.—A Holding for Folding,” Trends in Biochemical Sciences, Vol. 24, No. 4, 1999, pp. 136-141. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01373-0 [18] R. Zhao, M. Davey, Y. C. Hsu, P. Kaplanek, A. Tong, A. B. Parsons, N. Krogan, G. Cagney, D. Mai, J. Greenblatt, C. Boone, A. Emili and W. A. Houry, “Navigating the Chaperone Network: An Integrative Map of Physical and Genetic Interactions Mediated by the HSP90 Chaperone,” Cell, Vol. 120, No. 5, 2005, pp. 715-727. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.024 [19] A. J. McClellan, Y. Xia, A. M. Deutschbauer, R. W. Davis, M. Gerstein and J. Frydman, “Diverse Cellular Functions of the HSP90 Molecular Chaperone Uncovered Using Systems Approaches,” Cell, Vol. 131, No. 1, 2007, pp. 121-135. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.036 [20] M. Yano, Z. Naito, M. Yokoyama, Y. Shiraki, T. Ishiwata, M. Inokuchi and G. Asano, “Expression of HSP90 and Cyclin D1 in Human Breast Cancer,” Cancer Letters, Vol. 137, No. 1, 1999, pp. 45-51. doi:10.1016/S0304-3835(98)00338-3 [21] J. Beliakoff and L. Whitesell, “HSP90: An Emerging Target for Breast Cancer Therapy,” Anticancer Drugs Vol. 15, No. 7, 2004, pp. 651-662. doi:10.1097/01.cad.0000136876.11928.be [22] K. Nadeau, A. Das and C. T. Walsh, “HSP90 Chaperon- ins Possess ATPase Activity and Bind Heat Shock Tran- scription Factors and Peptidyl Prolyl Isomerases,” Jour- nal of Biological Chemistry, Vol. 268, No. 2, 1993, pp. 1479-1487. [23] S. Tsutsumi and L. Neckers, “Extracellular Heat Shock Protein 90: A Role for a Molecular Chaperone in Cell Motility and Cancer Metastasis,” Cancer Science, Vol. 98, No. 10, 2007, pp. 1536-1539. doi:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00561.x [24] J. C. Young, I. Moarefi and F. U. Hartl, “HSP90: A Spe- cialized But Essential Protein-Folding Tool,” Journal of Cell Biology, Vol. 154, No. 2, 2001, pp. 267-273. doi:10.1083/jcb.200104079 [25] D. R. Ciocca, F. E. Gago, M. A. Fanelli and S. K. Cal- derwood, “Co-Expression of Steroid Receptors (Estrogen Receptor Alpha and/or Progesterone Receptors) and Her-2/Neu: Clinical Implications,” Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Vol. 102, No. 1-5, 2006, pp. 32-40. [26] M. A. Fanelli, M. Montt-Guevara, A. M. Diblasi, F. E. Gago, O. Tello, F. D. Cuello-Carrión, E. Callegari, M. A. Bausero and D. R. Ciocca, “P-Cadherin and Beta-Catenin Are Useful Prognostic Markers in Breast Cancer Patients; Beta-Catenin Interacts with Heat Shock Protein HSP27,” Cell Stress & Chaperones, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2008, pp. 207- 220. doi:10.1007/s12192-007-0007-z [27] L. Meng, V. L. Gabai and M. Y. Sherman, “Heat-Shock Transcription Factor HSF1 Has a Critical Role in Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-2-Induced Cellular Transformation and Tumorigenesis,” Oncogene, Vol. 29, No. 37, 2010, pp. 5204-5213. doi:10.1038/onc.2010.277 [28] C. Garrido, M. Brunet, C. Didelot, Y. Zermati, E. Schmitt and G. Kroemer, “Heat Shock Proteins 27 and 70. Anti- Apoptotic Proteins with Tumorigenic Properties,” Cell Cycle, Vol. 5, No. 22, 2006, pp. 2592-2601. doi:10.4161/cc.5.22.3448 [29] C. Didelot, E. Schmitt, M. Brunet, L. Maingret, A. Par- cellier and C. Garrido, “Heat Shock Proteins: Endogenous Modulators of Apoptotic Cell Death,” Handbook of Ex- perimental Pharmacology, Vol. 172, 2006, pp. 171-198. doi:10.1007/3-540-29717-0_8 [30] E. Schmitt, M. Gehrmann, M. Brunet, G. Multhoff and C. Garrido, “Intracellular and Extracellular Functions of Heat Shock Proteins: Repercussions in Cancer Therapy,” Journal of Leukocyte Biology, Vol. 81, No. 1, 2007, pp. 15-27. doi:10.1189/jlb.0306167 [31] C. Paul, F. Manero, S. Gonin, C. Kretz-Remy, S. Virot and A. P. Arrigo, “HSP27 as a Negative Regulator of Cy- Tochrome c Release,” Molecular and Cellular Biology, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Mammary Neoplasms: A Brief Review 762 Vol. 22, No. 3, 2002, pp. 816-834. doi:10.1128/MCB.22.3.816-834.2002 [32] H. M. Beere, B. B. Wolf, K. Cain, D. D. Mosser, A. Ma- hboubi, T. Kuwana, P. Tailor, R. I. Morimoto, G. M. Cohen and D. R. Green, “Heat-Shock Protein 70 Inhibits Apoptosis by Preventing Recruitment of Procaspase-9 to the Apaf-1 Apoptosome,” Nature Cell Biology, Vol. 2, No. 8, 2000, pp. 469-475. doi:10.1038/35019501 [33] S. J. Charette, J. N. Lavoie, H. Lambert and J. Landry, “Inhibition of Daxx-Mediated Apoptosis by Heat Shock Protein 27,” Molecular and Cellular Biology, Vol. 20, No. 20, 2000, pp. 7602-7612. doi:10.1128/MCB.20.20.7602-7612.2000 [34] P. Workman, “Combinatorial Attack On Multistep On- cogenesis by Inhibiting the HSP90 Molecular Chaper- one,” Cancer Letters, Vol. 206, No. 2, 2004, pp. 149-157. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2003.08.032 [35] C. Sõti, E. Nagy, Z. Giricz, L. Vígh, P. Csermely and P. Ferdinandy, “Heat Shock Proteins as Emerging Thera- peutic Targets,” British Journal of Pharmacology, Vol. 146, No. 6, 2005, pp. 769-780. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706396 [36] Y. Xian Ma, S. Fan, J. Xiong, R. Q. Yuan, Q. Meng, M. Gao, I. D. Goldberg, S. A. Fuqua, R. G. Pestell and E. M. Rosen, “Role of BRCA1 in Heat Shock Response,” On- cogene, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2003, pp. 10-27. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1206061 [37] D. R. Hurst, A. Mehta, B. P. Moore, P. A. Phadke, W. J. Meehan, M. A. Accavitti, L. A. Shevde, J. E. Hopper, Y. Xie, D. R. Welch and R. S. Samant, “Breast Cancer Me- tastasis Suppressor 1 (BRMS1) Is Stabilized by the HSP90 Chaperone,” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Com- munications, Vol. 348, No. 4, 2006, pp. 1429-1435. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.005 [38] A. Thor, C. Benz, D. Moore 2nd, E. Goldman, S. Edger- ton, J. Landry, L. Schwartz, B. Mayall, E. Hickey and L. A. Weber, “Stress Response Protein (Srp-27) Determina- tion in Primary Human Breast Carcinomas: Clinical, His- tologic, and Prognostic Correlations,” Journal of the Na- tional Cancer Institute, Vol. 83, No. 3, 1991, pp. 170-178. doi:10.1093/jnci/83.3.170 [39] F. K. Storm, K. W. Gilchrist, T. F. Warner and D. M. Mahvi, “Distribution of HSP27 and Her-2/Neu in in Situ and Invasive Ductal Breast Carcinomas,” Annals of Sur- gical Oncology, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1995, pp. 43-48. doi:10.1007/BF02303701 [40] M. Yano, Z. Naito, S. Tanaka and G. Asano, “Expression and Roles of Heat Shock Proteins in Human Breast Can- cer,” Japanese Journal of Cancer Research, Vol. 87, No. 9, 1996, pp. 908-915. doi:10.1111/j.1349-7006.1996.tb02119.x [41] L. M. Vargas-Roig, M. A. Fanelli, L. A. López, F. E. Gago, O. Tello, J. C. Aznar and D. R. Ciocca, “Heat Shock Proteins and Cell Proliferation in Human Breast Cancer Biopsy Samples,” Cancer Detection and Preven- tion, Vol. 21, No. 5, 1997, pp. 441-451. [42] A. Ch. Lazaris, E. B. Chatzigianni, D. Panoussopoulos, G. N. Tzimas, P. S. Davaris and B. C. Golematis, “Prolifer- ating Cell Nuclear Antigen and Heat Shock Protein 70 Immunolocalization in Invasive Ductal Breast Cancer Not Otherwise Specified,” Breast Cancer Research and Treat- ment, Vol. 43, No. 1, 1997, pp. 43-51. doi:10.1023/A:1005706110275 [43] P. A. Townsend, E. Dublin, I. R. Hart, R. H. Kao, A. M. Hanby, R. I. Cutress, R. Poulsom, K. Ryder, D. M. Bar- nes and G. Packham, “BAG-I Expression in Human Breast Cancer: Interrelationships Between BAG-1 RNA, Protein, HSC70 Expression and Clinico-Pathological Data,” Journal of Pathology, Vol. 197, No. 1, 2002, pp. 51-59. doi:10.1002/path.1081 [44] S. Takahashi, E. Narimatsu, H. Asanuma, M. Okazaki, A. Okazaki, K. Hirata, M. Mori, T. Chiba, N. Sato and K. Kikuchi, “Immunohistochemical Detection of Estrogen Receptor in Invasive Human Breast Cancer: Correlation with Heat Shock Proteins, pS2 and Oncogene Products,” Oncology, Vol. 52, No. 5, 1995, pp. 371-375. [45] P. A. O'Neill, A. M. Shaaban, C. R. West, A. Dodson, C. Jarvis, P. Moore, M. P. Davies, D. R. Sibson and C. S. Foster, “Increased Risk of Malignant Progression in Be- nign Proliferating Breast Lesions Defined by Expression of Heat Shock Protein 27,” British Journal of Cancer, Vol. 90, No. 1, 2004, pp. 182-188. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601449 [46] D. R. Ciocca and E. H. Luque, “Immunological Evidence for the Identity between the HSP 27 Estrogen-Regulated Heat Shock Protein and the p29 Estrogen Recetor-Asso- ciated Protein in Breast and Endometrial Cancer,” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, Vol. 20, No. 1, 1991, pp. 33-42. doi:10.1007/BF01833355 [47] M. Muňoz de Toro and E. H. Luque, “Lack of Relation- ship between the Expression Of HSP27 Heat Shock Es- trogen Receptor-Associated Protein and Estrogen Recep- tor or Progesterone Receptor Status in Male Breast Car- cinoma,” Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Vol. 60, No. 5-6, 1997, pp. 277-284. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(96)00221-X [48] F. Thanner, M. W. Sütterlin, M. Kapp, L. Rieger, A. K. Morr, P. Kristen, J. Dietl, A. M. Gassel and T. Müller, “Heat Shock Protein 27 Is Associated with Decreased Survival in Node-Negative Breast Cancer Patients,” Anti- cancer Research, Vol. 25, No. 3A, 2005, pp. 1649-1653. [49] B. Têtu, J. Brisson, J. Landry and J. Huot, “Prognostic Significance of Heat-Shock Protein-27 in Node-Positve Breast Carcinoma: An Immunohistochemical Study,” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, Vol. 36, No. 1, 1995, pp. 93-97. doi:10.1007/BF00690189 [50] E. Ioachim, E. Tsanou, E. Briasoulis, Ch. Batsis, V. Karavasilis, A. Charchanti, N. Pavlidis and N. J. Agnantis, “Clinicopathological Study of the Expression of HSP27, pS2, Cathepsin D and Metallothionein in Primary Inva- sive Breast Cancer,” Breast, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2003, pp. 111-119. doi:10.1016/S0960-9776(02)00290-4 [51] S. A. Lee, D. Ndisang, C. Patel, J. H. Dennis, D. J. Faul- kes, C. D’Arrigo, L. Samady, S. Farooqui-Kabir, R. J. Heads, D. S. Latchman and V. S. Budhram-Mahadeo, “Expression of the Brn-3b Transcription Factor Correlates with Expression of HSP-27 in Breast Cancer Biopsies and Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Mammary Neoplasms: A Brief Review 763 Is Required for Maximal Activation of the HSP-27 Pro- moter,” Cancer Research, Vol. 65, No. 8, 2005, pp. 3072- 3080. [52] J. H. Dennis, V. Budhram-Mahadeo and D. S. Latchman, “The Brn-3b POU Family Transcription Factor Regulates the Cellular Growth, Proliferation, and Anchorage De- pendence of MCF7 Human Breast Cancer Cells,” Onco- gene, Vol. 20, No. 36, 2001, pp. 4961-4971. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204491 [53] S. Takahashi, T. Mikami, Y. Watanabe, M. Okazaki, Y. Okazaki, A. Okazaki, T. Sato, K. Asaishi, K. Hirata, E. Narimatsu, et al., “Correlation of Heat Shock Protein 70 Expression with Estrogen Receptor Levels in Invasive Human Breast Cancer,” American Journal of Clinical Pathology, Vol. 101, No. 4, 1994, pp. 519-525. [54] F. Thanner, M. W. Sütterlin, M. Kapp, L. Rieger, P. Kristen, J. Dietl, A. M. Gassel and T. Müller, “Heat- Shock Protein 70 as a Prognostic Marker in Node-Nega- tive Breast Cancer,” Anticancer Research, Vol. 23, No. 2A, 2003, pp. 1057-1062. [55] P. M. Fernandez, S. O. Tabbara, L. K. Jacobs, F. C. Man- ning, T. N. Tsangaris, A. M. Schwartz, K. A. Kennedy and S. R. Patierno, “Overexpression of the glucose- Regulated Stress Gene GRP78 in Malignant but Not Be- nign Human Breast Lesions,” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, Vol. 59, No. 1, 2000, pp. 15-26. doi:10.1023/A:1006332011207 [56] G. Shyamala, M. Schweitzer and S. J. Ullrich, “Relation- ship between 90-kilodalton Heat Shock Protein, Estrogen Receptor, and Progesterone Receptor in Human Mam- mary Tumors,” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, Vol. 26, No. 1, 1993, pp. 95-100. doi:10.1007/BF00682704 [57] F. Zagouri, T. N. Sergentanis, A. Nonni, C. A. Pa- padimitriou, N. V. Michalopoulos, P. Domeyer, G. Theodoropoulos, A. Lazaris, E. Patsouris, E. Zogafos, A. Pazaiti and G. C. Zografos, “HSP90 in the Continuum of Breast Ductal Carcinogenesis: Evaluation in Precursors, Preinvasive and Ductal Carcinoma Lesions,” BMC Can- cer, Vol. 10, 2010, p. 353. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-10-353 [58] S. Oesterreich, S. G. Hilsenbeck, D. R. Ciocca, D. C. Allred, G. M. Clark, G. C. Chamness, C. K. Osborne and S. A. Fuqua, “The Small Heat Shock Protein HSP27 Is Not an Independent Prognostic Marker in Axillary Lymph Node-Negative Breast Cancer Patients,” Clinical Cancer Research, Vol. 2, No. 7, 1996, pp. 1199-1206. [59] P. Lemieux, S. Oesterreich, J. A. Lawrence, P. S. Steeg, S. G. Hilsenbeck, J. M. Harvey and S. A. Fuqua, “The Small Heat Shock Protein HSP27 Increases Invasiveness but Decreases Motility of Breast Cancer Cells,” Invasion Metastasis, Vol. 17, No. 3, 1997, pp. 113-123. [60] J. Hurlimann, S. Gebhard and F. Gomez, “Oestrogen Receptor, Progesterone Receptor, pS2, ERD5, HSP27 and Cathepsin D in Invasive Ductal Breast Carcinomas,” Histopathology, Vol. 23, No. 3, 1993, pp. 239-248. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.1993.tb01196.x [61] D. R. Ciocca, S. Green, R. M. Elledge, G. M. Clark, R. Pugh, P. Ravdin, D. Lew, S. Martino and C. K. Osborne, “Heat Shock Proteins HSP27 and HSP70: Lack of Corre- lation with Response to Tamoxifen and Clinical Course of Disease in Estrogen Receptor-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer (a Southwest Oncology Group Study),” Clinical Cancer Research, Vol. 4, No. 5, 1998, pp. 1263-1266. [62] D. R. Ciocca, G. M. Clark, A. K. Tandon, S. A. Fuqua, W. J. Welch and W. L. McGuire, “Heat Shock Protein HSP70 in Patients with Axillary Lymph Node-Negative Breast Cancer: Prognostic Implications,” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Vol. 85, No. 7, 1993, pp. 570- 574. doi:10.1093/jnci/85.7.570 [63] H. M. Kluger, D. Chelouche Lev, Y. Kluger, M. M. McCarthy, G. Kiriakova, R. L. Camp, D. L. Rimm and J. E. Price, “Using a Xenograft Model of Human Breast Cancer Metastasis to Find Genes Associated with Clini- cally Aggressive Disease,” Cancer Research, Vol. 65, No. 13, 2005, pp. 5578-5587. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0108 [64] C. Torronteguy, A. Frasson, F. Zerwes, E. Winnikov, V. D. da Silva, A. Ménoret and C. Bonorino, “Inducible Heat Shock Protein 70 Expression as a Potential Predic- tive Marker of Metastasis in Breast Tumors,” Cell Stress & Chaperones, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2006, pp. 34-43. doi:10.1379/CSC-159R.1 [65] S. Liebhardt, N. Ditsch, R. Nieuwland, A. Rank, U. Jeschke, F. Von Koch, K. Friese and B. Toth, “CEA-, Her2/Neu-, BCRP- and HSP27-Positive Microparticles in Breast Cancer Patients,” Anticancer Research, Vol. 30, No. 5, 2010, pp. 1707-1712. [66] D. Chelouche-Lev, H. M. Kluger, A. J. Berger, D. L. Rimm and J. E. Price, “AlphaB-Crystallin as a Marker of Lymph Node Involvement in Breast Carcinoma,” Cancer, Vol. 100, No. 12, 2004, pp. 2543-2548. doi:10.1002/cncr.20304 [67] S. Mestiri, N. Bouaouina, S. B. Ahmed, A. Khedhaier, B. B. Jrad, S. Remadi and L. Chouchane, “Genetic Variation in the Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Promoter Region and in the Stress Protein HSP70-2: Susceptibility and Prognostic Implications in Breast Carcinoma,” Cancer, Vol. 91, No. 4, 2001, pp. 672-678. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(20010215)91:4<672::AID-CNCR 1050>3.0.CO;2-J [68] L. M. Vargas-Roig, F. E. Gago, O. Tello, J. C. Aznar and D. R. Ciocca, “Heat Shock Protein Expression and Drug Resistance in Breast Cancer Patients Treated with Induc- tion Chemotherapy,” International Journal of Cancer, Vol. 79, No. 5, 1998, pp. 468-475. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19981023)79:5<468::AID- IJC4>3.0.CO;2-Z [69] L. Chouchane, S. B. Ahmed, S. Baccouche and S. Re- madi, “Polymorphism in the Tumor Necrosis Factor-Al- pha Promotor Region and in the Heat Shock Protein 70 Genes Associated with Malignant Tumors,” Cancer, Vol. 80, No. 8, 1997, pp. 1489-1496. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19971015)80:8<1489::AID -CNCR17>3.0.CO;2-1 [70] S. E. Conroy, P. D. Sasieni, I. Fentiman and D. S. Latch- man, “Autoantibodies to the 90kDa Heat Shock Protein and Poor Survival in Breast Cancer Patients,” European Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Mammary Neoplasms: A Brief Review 764 Journal of Cancer, Vol. 34, No. 6, 1998, pp. 942-943. [71] E. Pick, Y. Kluger, J. M. Giltnane, C. Moeder, R. L. Camp, D. L. Rimm and H. M. Kluger, “High HSP90 Ex- pression Is Associated with Decreased Survival in Breast Cancer,” Cancer Research, Vol. 67, No. 7, 2007, pp. 2932-2937. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4511 [72] S. A. Fuqua, S. Oesterreich, S. G. Hilsenbeck, D. D. Von Hoff, J. Eckardt and C. K. Osborne, “Heat Shock Proteins and Drug Resistance,” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, Vol. 32, No. 1, 1994, pp. 67-71. doi:10.1007/BF00666207 [73] J. Gómez-Navarro, W. Arafat and J. Xiang, “Gene Ther- apy for Carcinoma of the Breast. Pro-Apoptotic Gene Therapy,” Breast Cancer Research, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2000, pp. 32-44. doi:10.1186/bcr27 [74] E. Tiligada, “Chemotherapy: Induction of Stress Re- sponses,” Endocrine-Related Cancer, Vol. 13, No. 1, 2006, pp. S115-24. doi:10.1677/erc.1.01272 [75] F. F. Liu, N. Miller, W. Levin, B. Zanke, B. Cooper, M. Henry, M. D. Sherar, M. Pintilie, J. W. Hunt and R. P. Hill, “The Potential Role of HSP70 as an Indicator of Response to Radiation and Hyperthermia Treatments for Recurrent Breast Cancer,” International Journal of Hy- perthermia, Vol. 12, No. 2, 1996, pp. 197-208. doi:10.3109/02656739609022508 [76] K. D. Shin, M. Y. Lee, D. S. Shin, S. Lee, K. H. Son, S. Koh, Y. K. Paik, B. M. Kwon and D. C. Han, “Blocking Tumor Cell Migration and Invasion with Biphenyl Isoxazole Derivative KRIBB3, a Synthetic Molecule That Inhibits HSP27 Phosphorylation,” Journal of Biological Chemistry, Vol. 280, No. 50, 2005, pp. 41439-41448. doi:10.1074/jbc.M507209200 [77] M. A. Bausero, A. Bharti, D. T. Page, K. D. Perez, J. W. Eng, S. L. Ordonez, E. E. Asea, C. Jantschitsch, I. Kin- das-Muegge, D. Ciocca and A. Asea, “Silencing the HSP25 Gene Eliminates Migration Capability of the Highly Metastatic Murine 4T1 Breast Adenocarcinoma Cell,” Tumour Biology, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2006, pp. 17-26. doi:10.1159/000090152 [78] S. Di Cosimo and J. Baselga, “Targeted Therapies in Breast Cancer: Where Are We Now?” European Journal of Cancer, Vol. 44, No. 18, 2008, pp. 2781-2790. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.09.026 [79] A. Ferrario, N. Rucker, S. Wong, M. Luna and C. J. Gomer, “Survivin, a Member of the Inhibitor of Apop- tosis Family, Is Induced by Photodynamic Therapy and Is a Target for Improving Treatment Response,” Cancer Research, Vol. 67, No. 10, 2007, pp. 4989-4995. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4785 [80] J. Kurebayashi, T. Otsuki, M. Kurosumi, S. Soga, S. Ak- inaga and H. Sonoo, “A Radicicol Derivative, KF58333, Inhibits Expression of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor, Angiogenesis and Growth of Human Breast Cancer Xenografts,” Japanese Journal of Cancer Research, Vol. 92, No. 12, 2001, pp. 1342-1351. doi:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2001.tb02159.x [81] L. Xiao, X. Lu and D. M. Ruden, “Effectivenes of HSP90 Inhibitors as Anti-Cancer Drugs,” Mini Reviews in Me- dicinal Chemistry, Vol. 6, No. 10, 2006, pp. 1137-1143. doi:10.2174/138955706778560166 [82] M. G. Marcu and L. M. Neckers, “The C-Terminal Half of Heat Shock Protein 90 Represents a Second Site for Pharmacologic Intervention in Chaperone Function,” Current Cancer Drug Targets, Vol. 3, No. 5, 2003, pp. 343-347. doi:10.2174/1568009033481804 [83] M. G. Marcu, A. Chadli, I. Bouhouche, M. Catelli and L. M. Neckers, “The Heat Shock Protein 90 Antagonist No- vobiocin Interacts with a Previously Unrecognized ATP- Binding Domain in the Carboxyl Terminus of the Chap- erone,” Journal of Biological Chemistry, Vol. 275, No. 47, 2000, pp. 37181-37186. doi:10.1074/jbc.M003701200 [84] A. Kamal, L. Thao, J. Sensintaffar, L. Zhang, M. F. Boehm, L. C. Fritz and F. J. Burrows, “A High-Affinity Conformation of HSP90 Confers Tumour Selectivity on HSP90 inhibitors,” Nature, Vol. 425, No. 6956, 2003, pp. 407-410. doi:10.1038/nature01913 [85] L. T. Gooljarsingh, C. Fernandes, K. Yan, H. Zhang, M. Grooms, K. Johanson, R. H. Sinnamon, R. B. Kirkpatrick, J. Kerrigan, T. Lewis, M. Arnone, A. J. King, Z. Lai, R. A. Copeland and P. J. Tummino, “A Biochemical Ration- ale for the Anticancer Effects of HSP90 Inhibitors: Slow, Tight Binding Inhibition by Geldanamycin and Its Ana- logues,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sci- ences of the United States of America, Vol. 103, No. 20, 2006, pp. 7625-7630. doi:10.1073/pnas.0602650103 [86] I. Pashtan, S. Tsutsumi, S. Wang, W. Xu and L. Neckers, “Targeting HSP90 Prevents Escape of Breast Cancer Cells from Tyrosine Kinase Inhibition,” Cell Cycle, Vol. 7, No. 18, 2008, pp. 2936-2941. doi:10.4161/cc.7.18.6701 [87] K. Hatake, N. Tokudome and Y. Ito, “Next Generation Molecular Targeted Agents for Breast Cancer: Focus on EGFR and VEGFR Pathways,” Breast Cancer, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2007, pp. 132-149. doi:10.2325/jbcs.977 [88] B. Zsebik, A. Citri, J. Isola, Y. Yarden, J. Szöllosi and G. Vereb, “HSP90 Inhibitor 17-AAG Reduces ErbB2 Levels and Inhibits Proliferation of the Trastuzumab Resistant Breast Tumor Cell Line JIMT-1,” Immunology Letters, Vol. 104, No. 1-2, 2006, pp. 146-155. doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2005.11.018 [89] A. I. Robles, M. H. Wright, B. Gandhi, S. S. Feis, C. L. Hanigan, A. Wiestner and L. Varticovski, “Sched- ule-Dependent Synergy between the Heat Shock Protein 90 Inhibitor 17-(Dimethylaminoethylamino)-17-Demeth- oxygeldanamicin and Doxorubicin Restores Apoptosis to p53-Mutant Lymphoma Cell Lines,” Clinical Cancer Re- search, Vol. 12, No. 21, 2006, pp. 6547-6556. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1178 [90] G. Kaur, D. Belotti, A. M. Burger, K. Fisher-Nielson, P. Borsotti, E. Riccardi, J. Thillainathan, M. Hollingshead, E. A. Sausville and R. Giavazzi, “Antiangiogenic Properties of 17-(Dimethylaminoethylamino)-17-Demethoxygelda- namycin: An Orally Bioavailable Heat Shock Protein 90 Modulator,” Clinical Cancer Research, Vol. 10, No. 14, 2004, pp. 4813-4821. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0795 [91] D. B. Solit, A. D. Basso, A. B. Olshen, H. I. Scher and N. Rosen, “Inhibition of Heat Shock Protein 90 Function Down-Regulates Akt Kinase and Sensitizes Tumors to Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Mammary Neoplasms: A Brief Review 765 Taxol,” Cancer Research, Vol. 63, No. 9, 2003, pp. 2139- 2144. [92] U. Banerji, A. O’Donnell, M. Scurr, S. Pacey, S. Staple- ton, Y. Asad, L. Simmons, A. Maloney, F. Raynaud, M. Campbell, M. Walton, S. Lakhani, S. Kaye, P. Workman and I. Judson, “Phase I Pharmacokinetic and Pharmaco- dynamic Study of 17-Allylamino, 17-Demethoxygelda- namycin in Patients with Advanced Malignancies,” Jour- nal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 23, No. 18, 2005, pp. 4152- 4161. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.00.612 [93] M. P. Goetz, D. Toft, J. Reid, M. Ames, B. Stensgard, S. Safgren, A. A. Adjei, J. Sloan, P. Atherton, V. Vasile, S. Salazaar, A. Adjei, G. Croghan and C. Erlichman, “Phase I Trial of 17-Allylamino-17-Demethoxygeldanamycin in Patients with Advanced Cancer,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 23, No. 6, 2005, pp. 1078-1087. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.09.119 [94] J. L. Grem, G. Morrison, X. D. Guo, E. Agnew, C. H. Takimoto, R. Thomas, E. Szabo, L. Grochow, F. Groll- man, J. M. Hamilton, L. Neckers and R. H. Wilson, “Phase I and Pharmacologic Study of 17-(Allylamino)- 17-Demethoxygeldanamycin in Adult Patients with Solid Tumors,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 23, No. 9, 2005, pp. 1885-1893. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.12.085 [95] R. K. Ramanathan, D. L. Trump, J. L. Eiseman, C. P. Belani, S. S. Agarwala, E. G. Zuhowski, J. Lan, D. M. Potter, S. P. Ivy, S. Ramalingam, A. M. Brufsky, M. K. Wong, S. Tutchko and M. J. Egorin, “Phase I Pharma- cokinetic-Pharmacodynamic Study of 17-(Allylamino)- 17-Demethoxygeldanamycin (17AAG, NSC 330507), a Novel Inhibitor of Heat Shock Protein 90, in Patients with Refractory Advanced Cancers,” Clinical Cancer Research, Vol. 11, No. 9, 2005, pp. 3385-3391. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2322 [96] L. Neckers and K. Neckers, “Heat-Shock Protein 90 In- hibitors as Novel Cancer Chemotherapeutics—An Up- date,” Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs, Vol. 10, No. 1, 2005, pp. 137-149. doi:10.1517/14728214.10.1.137 [97] G. S. Nowakowski, A. K. McCollum, M. M. Ames, S. J. Mandrekar, J. M. Reid, A. A. Adjei, D. O. Toft, S. L. Safgren and C. Erlichman, “A Phase I Trial of Twice- Weekly 17-Allylamino-Demethoxy-Geldanamycin in Pa- tients with Advanced Cancer,” Clinical Cancer Research, Vol. 12, No. 20, 2006, pp. 6087-6093. [98] F. N. Shadad and R. K. Ramanathan, “17-Dimethylami- noethylamino-17-Demethoxygeldanamycin in Patients with Advanced-Stage Solid Tumors and Lymphoma: A Phase I Study,” Clinical Lymphoma & Myeloma, Vol. 6, No. 6, 2006, pp. 500-501. doi:10.3816/CLM.2006.n.034 [99] S. Sharp and P. Workman, “Inhibitors of the HSP90 Mo- lecular Chaperone: Current Status,” Advances in Cancer Research, Vol. 95, 2006, pp. 323-348. doi:10.1016/S0065-230X(06)95009-X [100] S. Modi, A. T. Stopeck, M. S. Gordon, D. Mendelson, D. B. Solit, R. Bagatell, W. Ma, J. Wheler, N. Rosen, L. Norton, G. F. Cropp, R. G. Johnson, A. L. Hannah and C. A. Hudis, “Combination of Trastuzumab and Tanespimy- cin (17-AAG, KOS-953) Is Safe and Active in Trastuzu- mab-Refractory HER-2 Overexpressing Breast Cancer: A Phase I Dose-Escalation Study,” Journal of Clinical On- cology, Vol. 25, No. 34, 2007, pp. 5410-5417. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.11.7960 [101] S. Pacey, U. Banerji, I. Judson and P. Workman, “HSP90 Inhibitors in the Clinic,” Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, Vol. 172, 2006, pp. 331-358. doi:10.1007/3-540-29717-0_14 [102] S. Messaoudi, J. F. Peyrat, J. D. Brion and M. Alami, “Recent Advances in HSP90 Inhibitors as Antitumor Agents,” Anticancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry, Vol. 8, No. 7, 2008, pp. 761-782. [103] D. B. Solit and G. Chiosis, “Development and Applica- tion of HSP90 Inhibitors,” Drug Discovery Today, Vol. 13, No. 1-2, 2008, pp. 38-43. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2007.10.007 [104] Y. Li, T. Zhang, S. J. Schwartz and D. Sun, “New De- velopments in HSP90 Inhibitors as Anti-Cancer Thera- peutics: Mechanisms, Clinical Perspective and More Po- tential,” Drug Resistance Updates, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2009, pp. 17-27. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2008.12.002 [105] Y. Fukuyo, C. R. Hunt and N. Horikoshi, “Geldanamycin and Its Anti-Cancer Activities,” Cancer Letters, Vol. 290, No. 1, 2010, pp. 24-35. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2009.07.010 [106] S. T. Calderwood, “Heat Shock Protein in Breast Cancer Progression—A Suitable Case for Treatment?” Interna- tional Journal of Hyperthermia, Vol. 26, No. 7, 2010, pp. 681-685. doi:10.3109/02656736.2010.490254 [107] D. M. Nguyen, D. Lorang, G. A. Chen, J. H. Stewart 4th, E. Tabibi and D. S. Schrump, “Enhancement of Pacli- taxel-Mediated Cytotoxicity in Lung Cancer Cells by 17- Allylamino Geldanamycin: In Vitro and in Vivo Analy- sis,” Annals of Thoracic Surgery, Vol. 72, No. 2, 2001, pp. 371-379. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(01)02787-4 [108] M. Rahmani, C. Yu, Y. Dai, E. Reese, W. Ahmed, P. Dent and S. Grant, “Coadministration of the Heat Shock Protein 90 Antagonist 17—Allylamino-17-Demethoxy- geldanamycin with Suberoylanilide Hydroxamic Acid or Sodium Butyrate Synergistically Induces Apoptosis in Human Leukemia Cells,” Cancer Research, Vol. 63, No. 23, 2003, pp. 8420-8427. [109] P. George, P. Bali, P. Cohen, J. Tao, F. Guo, C. Sigua, A. Vishvanath, W. Fiskus, A. Scuto, S. Annavarapu, L. Mo- scinski and K. Bhalla, “Cotreatment with 17-Allylamino- Demethoxygeldanamycin and FLT-3 Kinase Inhibitor PKC412 Is Highly Effective against Human Acute Mye- logenous Leukemia Cells with Mutant FLT-3,” Cancer Research, Vol. 64, No. 10, 2004, pp. 3645-3652. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0006 [110] P. George, P. Bali, S. Annavarapu, A. Scuto, W. Fiskus, F. Guo, C. Sigua, G. Sondarva, L. Moscinski, P. Atadja and K. Bhalla, “Combination of the Histone Deacetylase In- hibitor LBH589 and the HSP90 Inhibitor 17-AAG Is Highly Active against Human CML-BC Cells and AML Cells with Activating Mutation of FLT-3,” Blood, Vol. 105, No. 4, 2005, pp. 1768-1776. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-09-3413 [111] R. A. Mesa, D. Loegering, H. L. Powell, K. Flatten, S. J. Arlander, N. T. Dai, M. P. Heldebrant, B. T. Vroman, B. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Mammary Neoplasms: A Brief Review 766 D . Smith, J. E. Karp, C. J. Eyck, C. Erlichman, S. H. Kaufmann and L. M. Karnitz, “Heat Shock Protein 90 In- hibition Sensitizes Acute Myelogenous Leukemia Cells to Cytarabine,” Blood, Vol. 106, No. 1, 2005, pp. 318-327. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-09-3523 [112] I. A. Vasilevskaya and P. J. O’Dwyer, “17-Allylamino- 17-Demethoxygeldanamycin Overcomes Trail Resistance in Colon Cancer Cell Lines,” Biochemical Pharmacology, Vol. 70, No. 4, 2005, pp. 580-589. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2005.05.018 [113] C. R. Barker, A. V. McNamara, S. A. Rackstraw, D. E. Nelson, M. R. White, A. J. Watson and J. R. Jenkins, “In- hibition of HSP90 Acts Synergistically with Topoisom- erase II Poisons to Increase the Apoptotic Killing of Cells Due to an Increase in Topoisomerase II Mediated DNA Damage,” Nucleic Acids Research, Vol. 34, No. 4, 2006, pp. 1148-1157. doi:10.1093/nar/gkj516 [114] N. Sain, B. Krishnan, M. G. Ormerod, A. De Rienzo, W. M. Liu, S. B. Kaye, P. Workman and A. L. Jackman, “Potentiation of Paclitaxel Activity by the HSP90 Inhibi- tor17-Allylamino-17-Demethoxygeldanamycin in Human Ovarian Carcinoma Cell Lines with High Levels of Acti- vated AKT,” Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, Vol. 5, No. 5, 2006, pp. 1197-1208. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0445 [115] D. R. Premkumar, B. Arnold and I. F. Pollack, “Coopera- tive Inhibitory Effect of ZD1839 (Iressa) in Combination with 17-AAG on Glioma Cell Growth,” Molecular Car- cinogenesis, Vol. 45, No. 5, 2006, pp. 288-301. doi:10.1002/mc.20141 [116] S. S. Ramalingam, M. J. Egorin, R. K. Ramanathan, S. C. Remick, R. P. Sikorski, T. F. Lagattuta, G. S. Chatta, D. M. Friedland, R. G. Stoller, D. M. Potter, S. P. Ivy and C. P. Belani, “A Phase I Study of 17-Allylamino-17-De- methoxygeldanamycin Combined with Paclitaxel in Pa- tients with Advanced Solid Malignancies,” Clinical Can- cer Research, Vol. 14, No. 11, 2008, pp. 3456-3461. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5088 [117] J. T. Price, J. M. Quinn, N. A. Sims, J. Vieusseux, K. Waldeck, S. E. Docherty, D. Myers, A. Nakamura, M. C. Waltham, M. T. Gillespie and E. W. Thompson, “The Heat Shock Protein 90 Inhibitor, 17-Allylamino-17-De- methoxygeldanamicin, Enhances Osteoclast Formation and Potentiates Bone Metastasis of a Human Breast Can- cer Cell Line,” Cancer Research, Vol. 65, No. 11, 2005, pp. 4929-4938. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4458 [118] G. Chiosis, “Discovery and Development of Purine- Scaffold HSP90 Inhibitors,” Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry, Vol. 6, No. 11, 2006, pp. 1183-1191. doi:10.2174/156802606777812013 [119] M. R. Jensen, J. Schoepfer, T. Radimerski, A. Massey, C. T. Guy, J. Brueggen, C. Quadt, A. Buckler, R. Cozens, M. J. Drysdale, C. Garcia-Echeverria and P. Chène, “NVP- AUY922: A Small Molecule HSP90 Inhibitor with Potent Antitumor Activity in Preclinical Breast Cancer Models,” Breast Cancer Research, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2008, p. R33. doi:10.1186/bcr1996 [120] F. Yi and L. Regan, “A Novel Class of Small Molecule Inhibitors of HSP90,” ACS Chemical Biology, Vol. 3, No. 10, 2008, pp. 645-654. doi:10.1021/cb800162x [121] J. L. Holmes, S. Y. Sharp, S. Hobbs and P. Workman, “Silencing of HSP90 Cochaperone AHA1 Expression Decreases Client Protein Activation and Increases Cellu- lar Sensitivity to the HSP90 Inhibitor 17-Allylamino-17- Demethoxygeldanamycin,” Cancer Research, Vol. 68, No. 4, 2008, pp. 1188-1197. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3268 [122] W. Fiskus, Y. Ren, A. Mohapatra, P. Bali, A. Mandawat, R. Rao, B. Herger, Y. Yang, P. Atadja, J. Wu and K. Bhalla, “Hydroxamic Acid Analogue Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors Attenuate Estrogen Receptor-Alpha Levels and Transcriptional Activity: A Result of Hyperacetylation and Inhibition of Chaperone Function of Heat Shock Pro- tein 90,” Clinical Cancer Research, Vol. 13, No. 16, 2007, pp. 4882-4890. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3093 [123] S. Tsutsumi, B. Scroggins, F. Koga, M. J. Lee, J. Trepel, S. Felts, C. Carreras and L. Neckers, “Small Molecule Cell-Impermeant HSP90 Antagonist Inhibits Tumor Cell Motility and Invasion,” Oncogene, Vol. 27, No. 17, 2008, pp. 2478-2487. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1210897 [124] S. K. Calderwood and J. Gong, “Molecular Chaperones in Mammary Cancer Growth and Breast Tumor Therapy,” Journal of Cellular Biochemistry, Vol. 113, No. 4, 2012, pp. 1096-1103. doi:10.1002/jcb.23461 [125] H. Yi, Y. Rong, Z. Yankai, L. Wentao, Z. Hongxia, W. Jie, C. Rongyue, L. Taiming and L. Jingjing, “Improved Efficacy of DNA Vaccination against Breast Cancer by Boosting with the Repeat Beta-hCG C-Terminal Peptide Carried by Mycobacterial Heat-Shock Protein HSP65,” Vaccine, Vol. 24, No. 14, 2006, pp. 2575-2584. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.12.030 [126] Y. Takakura, S. Takemoto and M. Nishikawa, “HSP- Based Tumor Vaccines: State-of-the-Art and Future Di- rections,” Current Opinion in Molecular Therapeutics, Vol. 9, No. 4, 2007, pp. 385-391. [127] J. Schreiber, R. Stahn, J. A. Schenk, U. Karsten and G. Pecher, “Binding of Tumor Antigen Mucin (MUC1) De- rived Peptides to the Heat Shock Protein DnaK,” Anti- cancer Research, Vol. 20, No. 5A, 2000, pp. 3093-3098. [128] P. Srivastava, “Interaction of Heat Shock Proteins with Peptides and Antigen Presenting Cells: Chaperoning of the Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses,” Annual Re- view of Immunology, Vol. 20, 2002, pp. 395-425. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064801 [129] V. Mazzaferro, J. Coppa, M. G. Carrabba, L. Rivoltini, M. Schiavo, E. Regalia, L. Mariani, T. Camerini, A. Marchianò, S. Andreola, R. Camerini, M. Corsi, J. J. Lewis, P. K. Srivastava and G. Parmiani, “Vaccination with Autolo- gous Tumor-Derived Heat-Shock Protein gp96 after Liver Resection for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer,” Clinical Cancer Research, Vol. 9, No. 9, 2003, pp. 3235-3245. [130] M. J. Smith, A. C. Culhane, S. Killeen, M. A. Kelly, J. H. Wang, T. G. Cotter and H. P. Redmond, “Mechanisms Driving Local Breast Cancer Recurrence in a Model of Breast-Conserving Surgery,” Annals of Surgical Oncol- ogy, Vol. 15, No. 10, 2008, pp. 2954-2964. doi:10.1245/s10434-008-0037-5 [131] K. P. Lee, L. E. Raez and E. R. Podack, “Heat Shock Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Mammary Neoplasms: A Brief Review Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT 767 Protein-Based Cancer Vaccines,” Hematology Oncology Clinics of North America, Vol. 20, No. 3, 2006, pp. 637- 659. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2006.02.007 [132] A. Murshid, J. Gong and S. K. Calderwood, “Heat-Shock Proteins in Cancer Vaccines: Agents of Antigen Cross- Presentation,” Expert Review of Vaccines, Vol. 7, No. 7, 2008, pp. 1019-1030. doi:10.1586/14760584.7.7.1019 [133] M. Tariq, U. Nussbaumer, Y. Chen, C. Beisel and R. Paro, “Trithorax Requires HSP90 for Maintenance of Active Chromatin at Sites of Gene Expression,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Vol. 106, No. 4, 2009, pp. 1157-1162. doi:10.1073/pnas.0809669106 [134] K. Makiyama, J. Hamada, M. Takada, K. Murakawa, Y. Takahashi, M. Tada, E. Tamoto, G. Shindo, A. Matsu- naga, K. Teramoto, K. Komuro, S. Kondo, H. Katoh, T. Koike and T. Moriuchi, “Aberrant Expression of HOX Genes in Human Invasive Breast Carcinoma,” Oncology Reports, Vol. 13, No. 4, 2005, pp. 673-679. [135] O. Boucherat, F. Guillou, J. Aubin and L. Jeannotte, “Hoxa5: A Master Gene with Multifaceted Roles,” Médecine Sciences (Paris), Vol. 25, No. 1, 2009, pp. 77-82. doi:10.1051/medsci/200925177

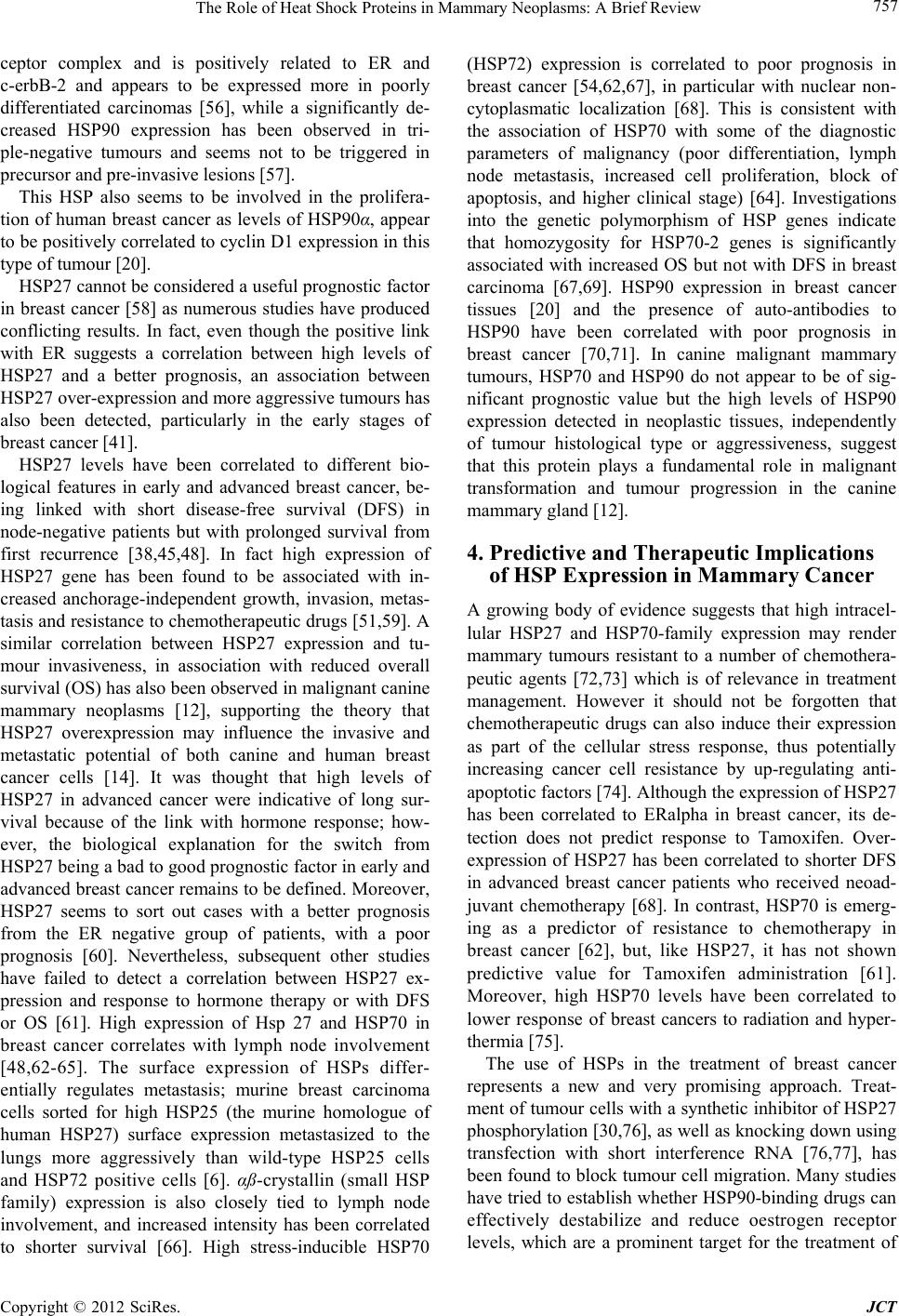

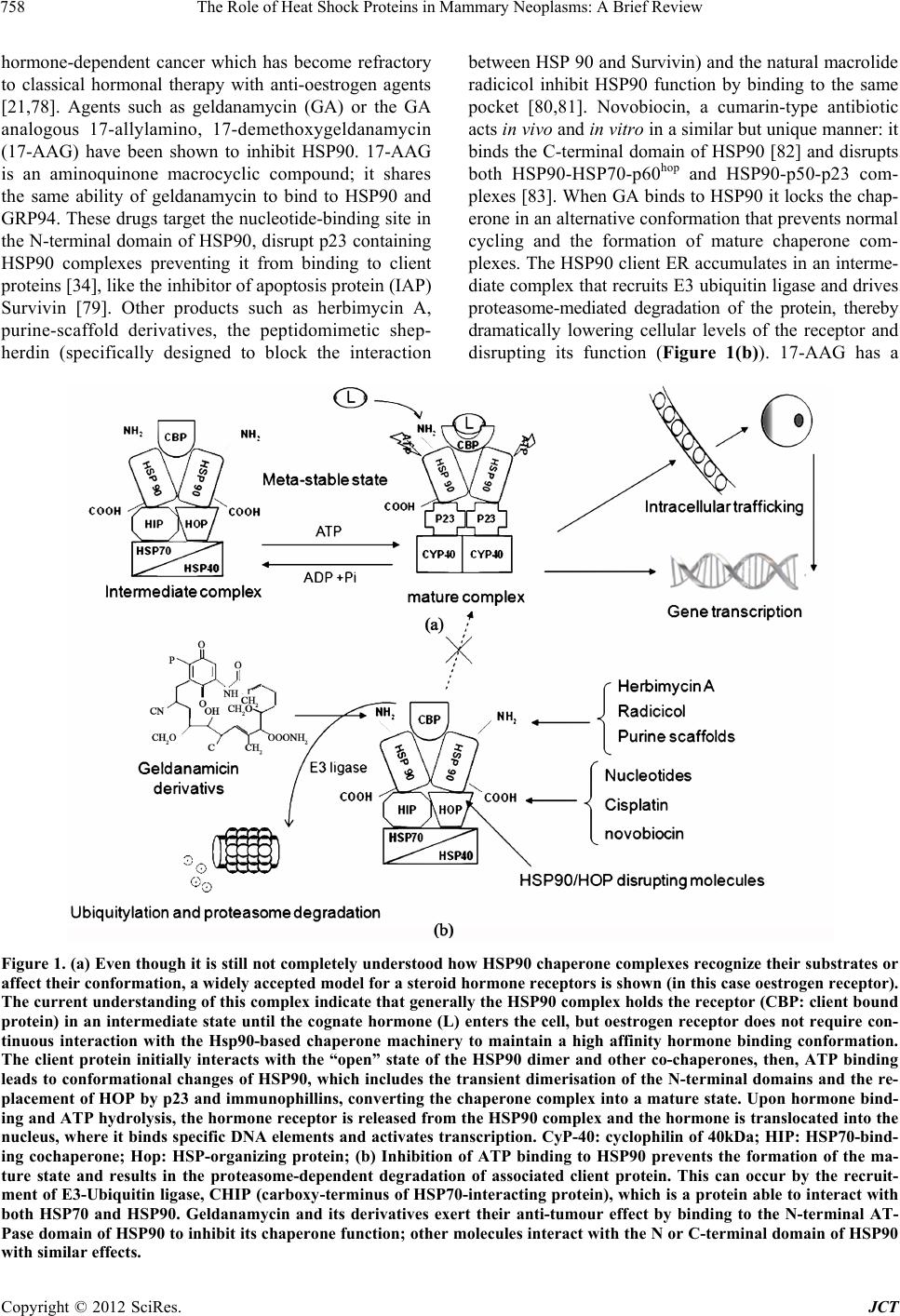

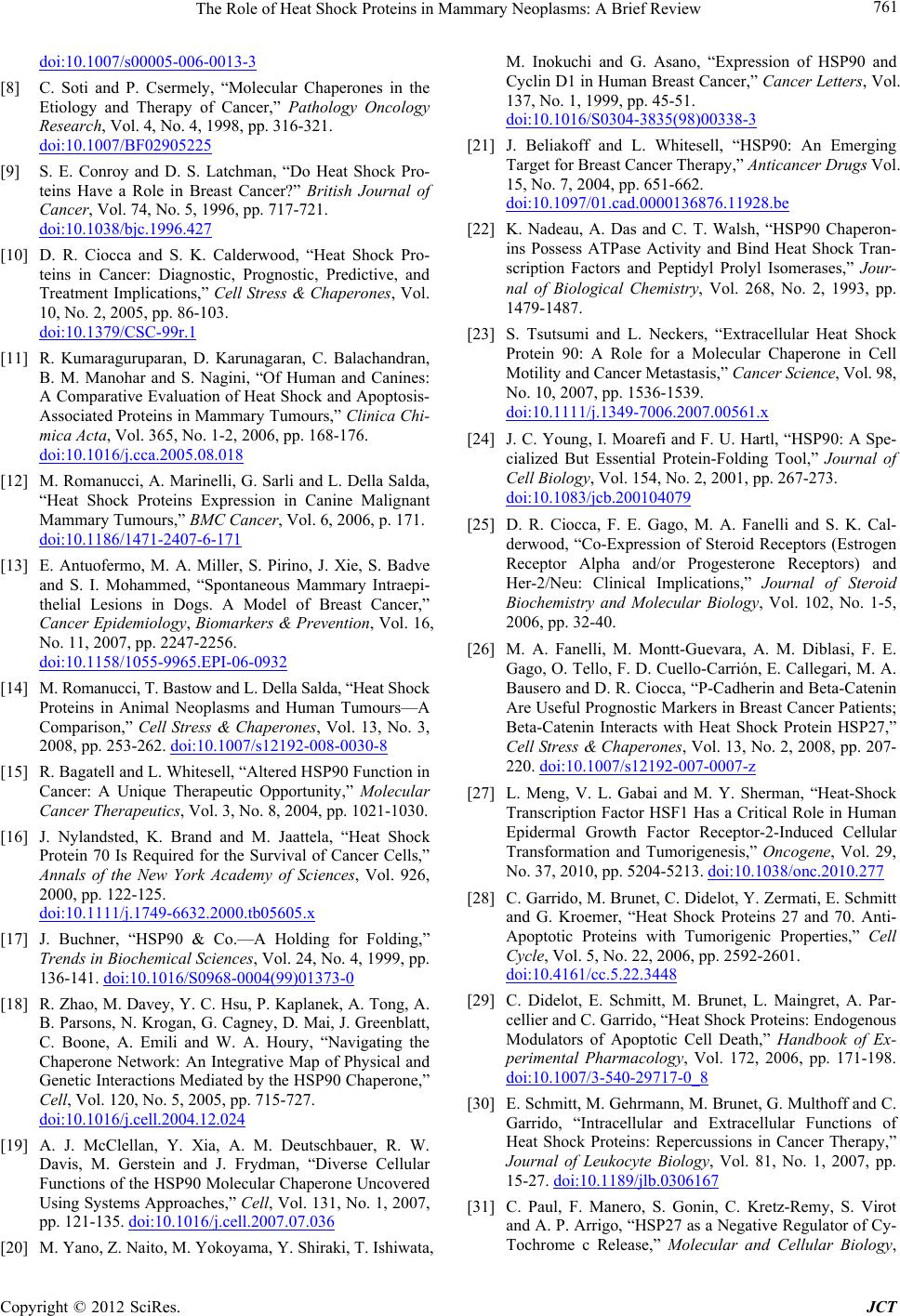

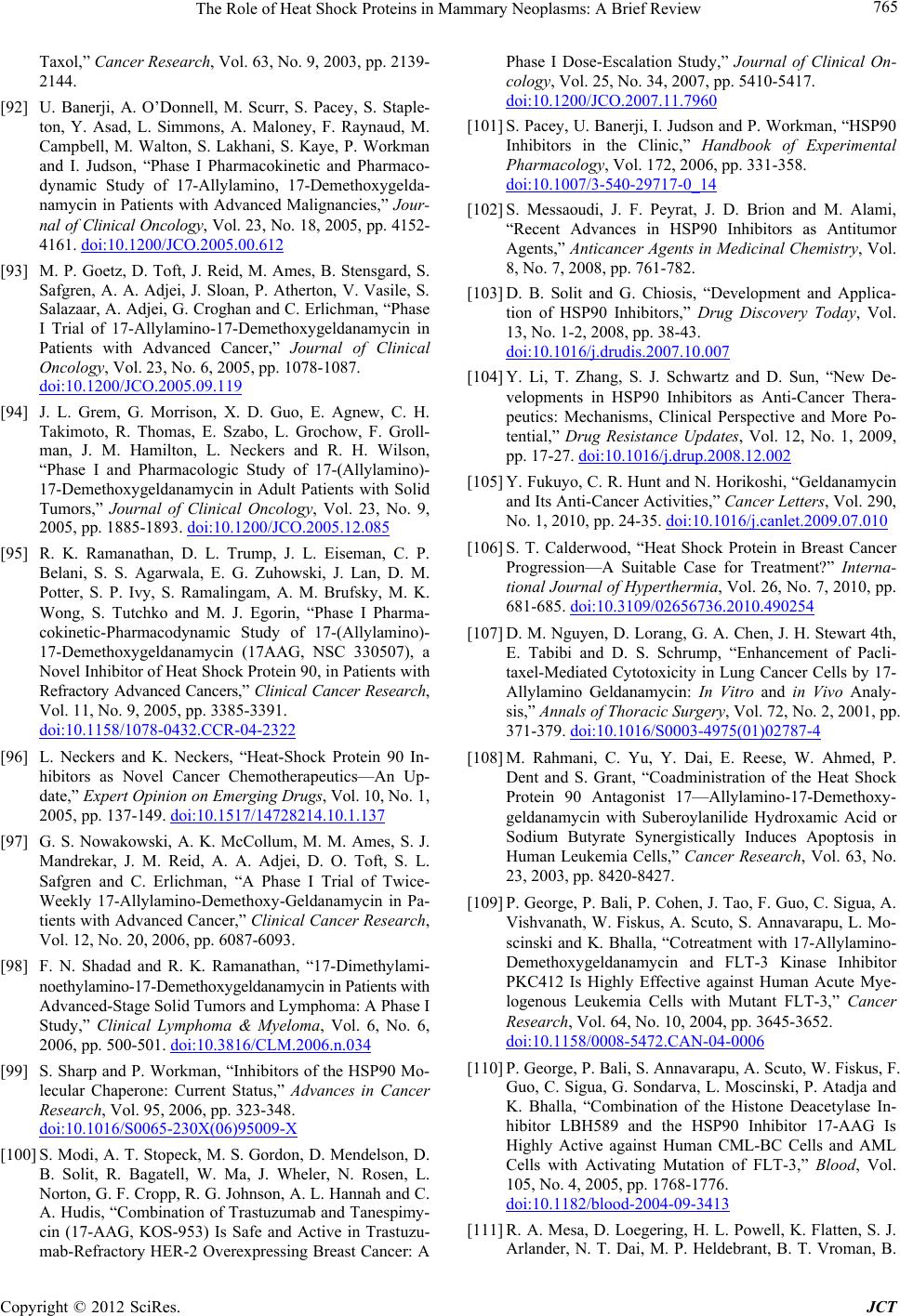

|