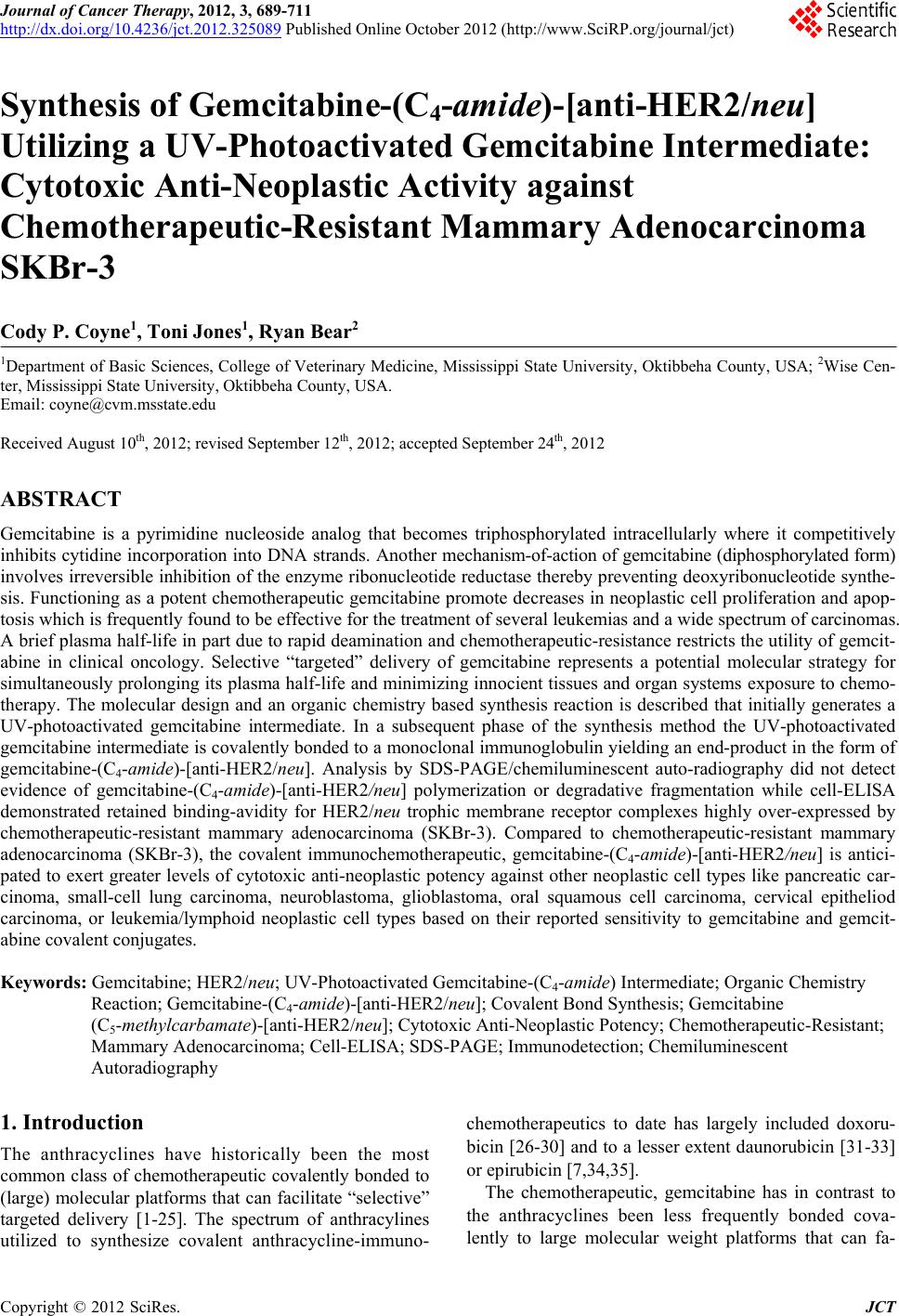

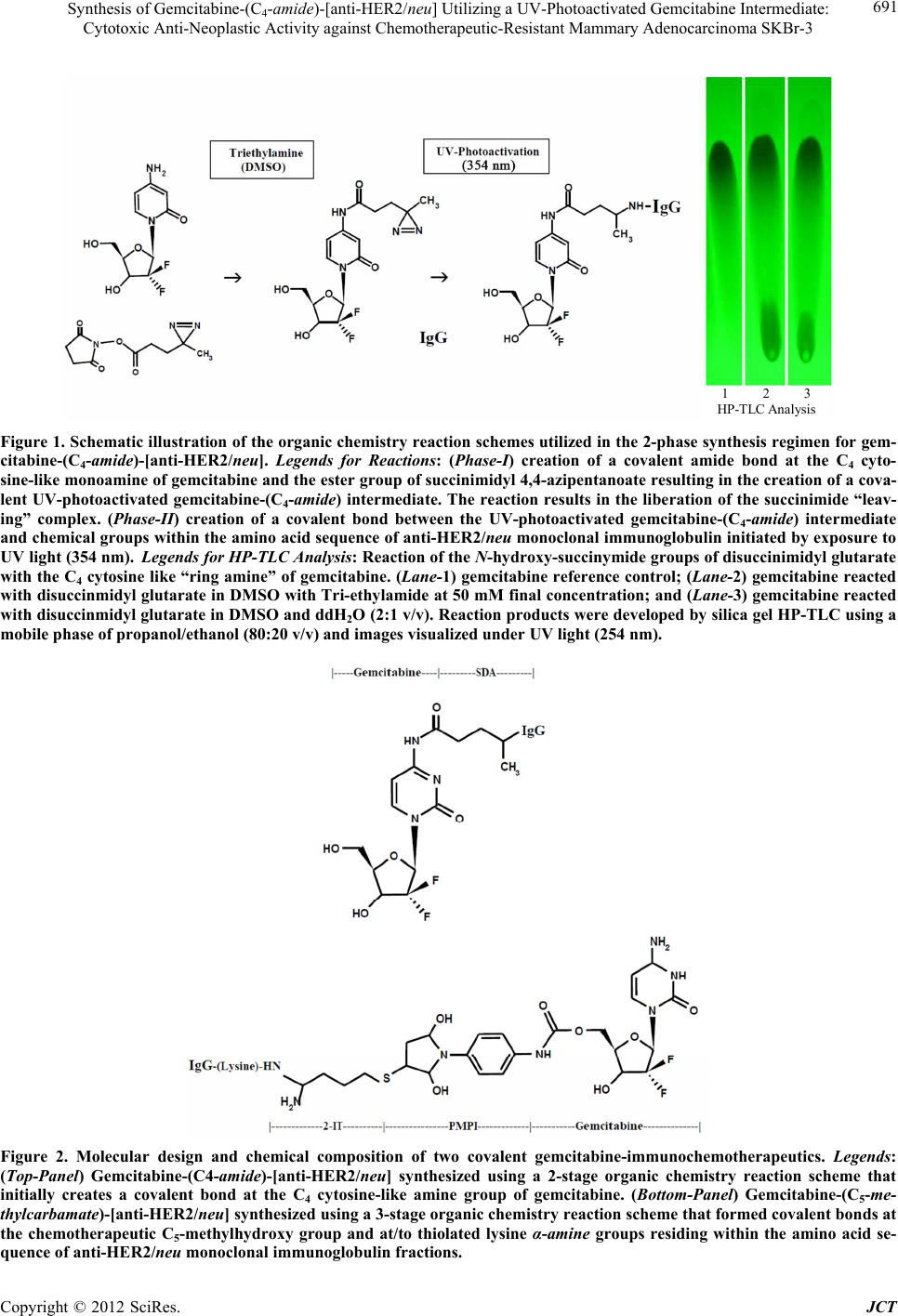

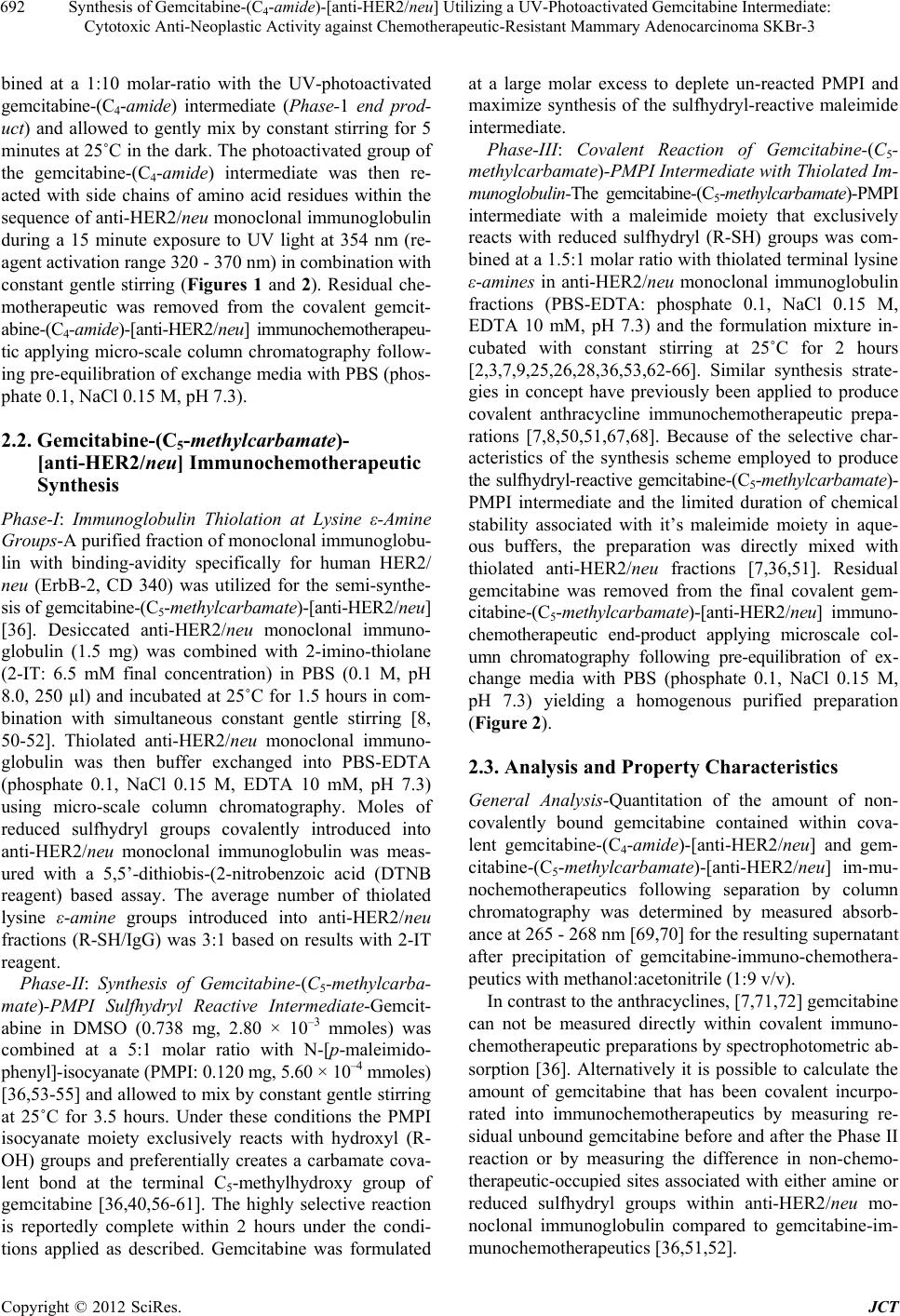

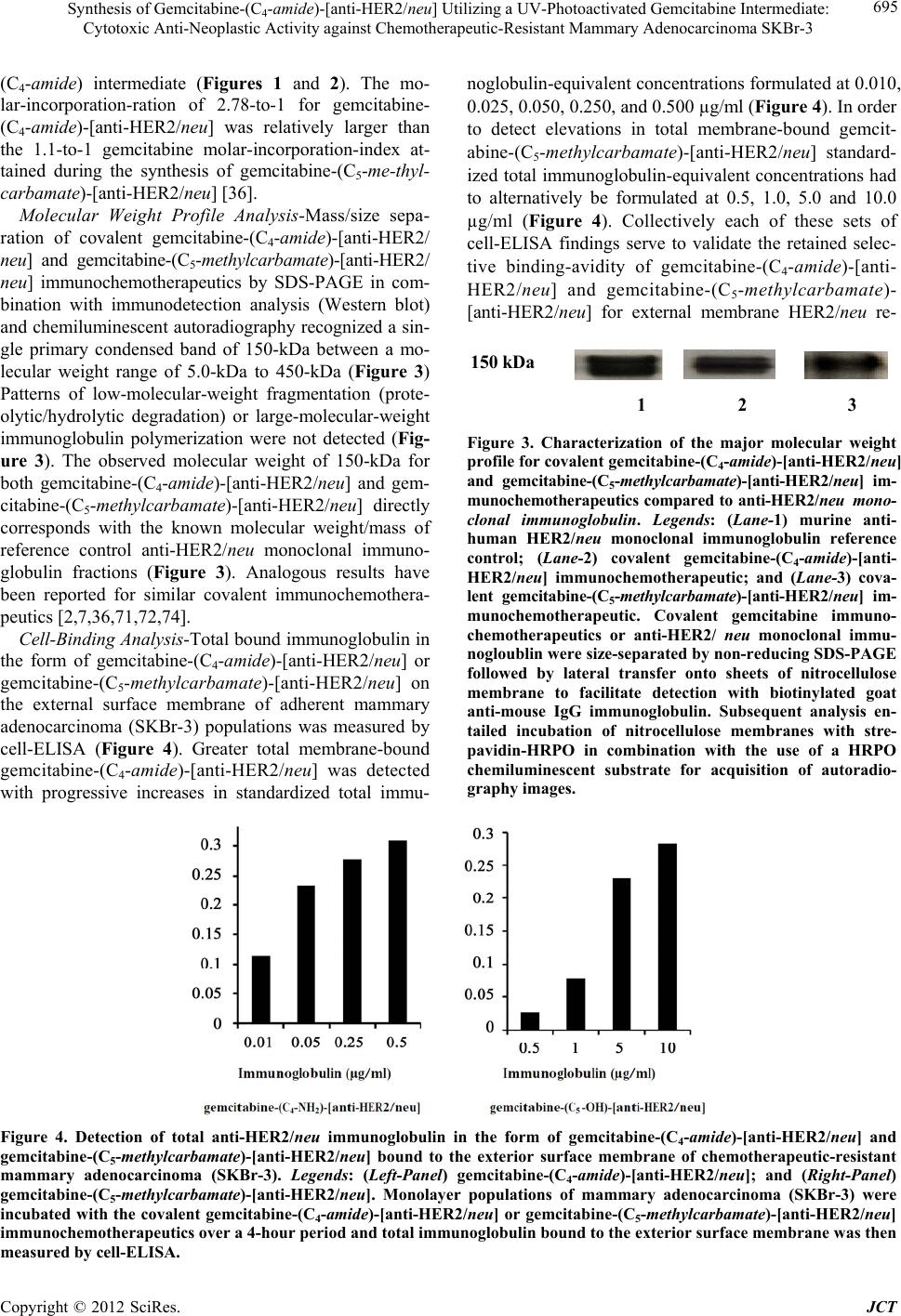

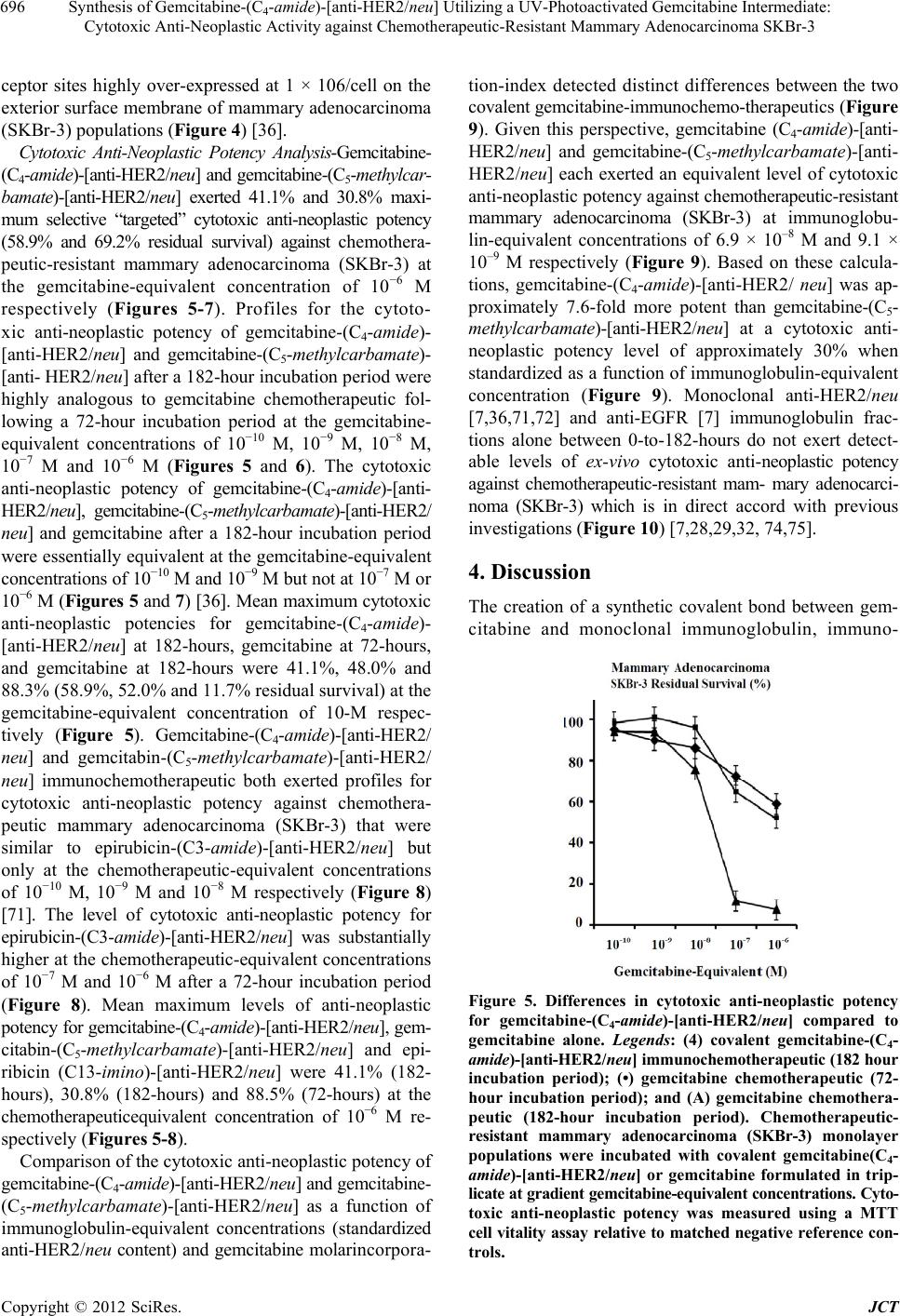

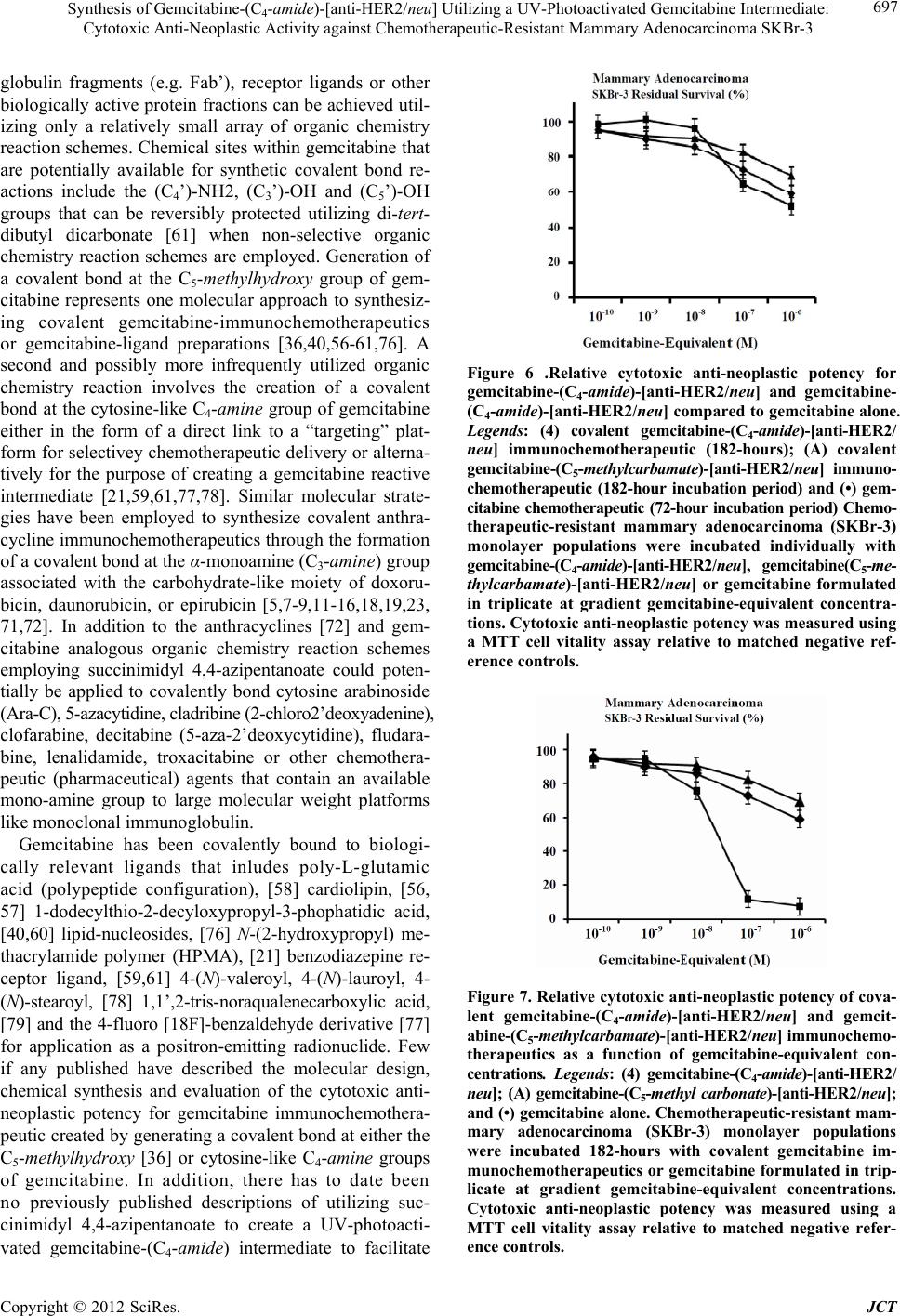

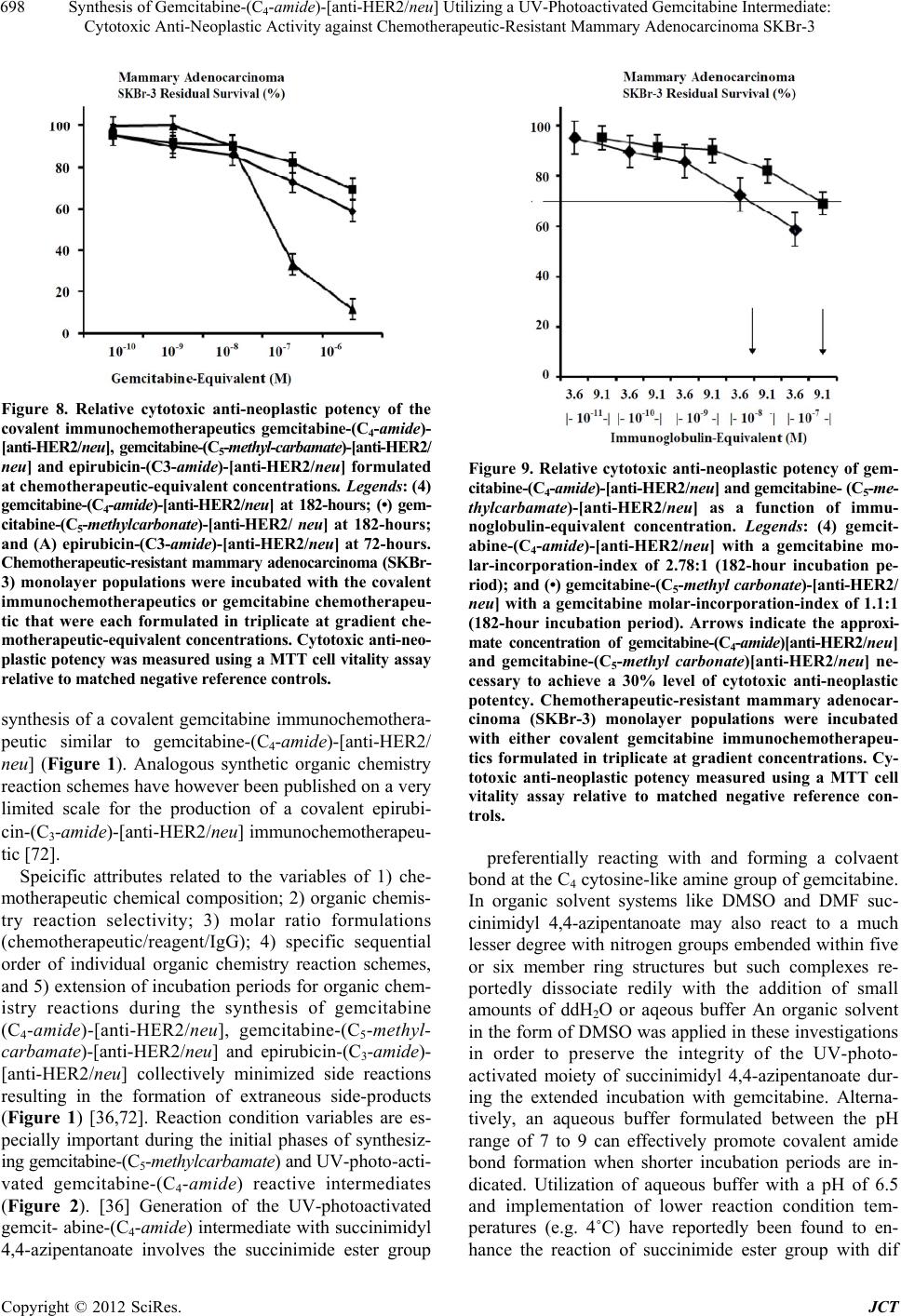

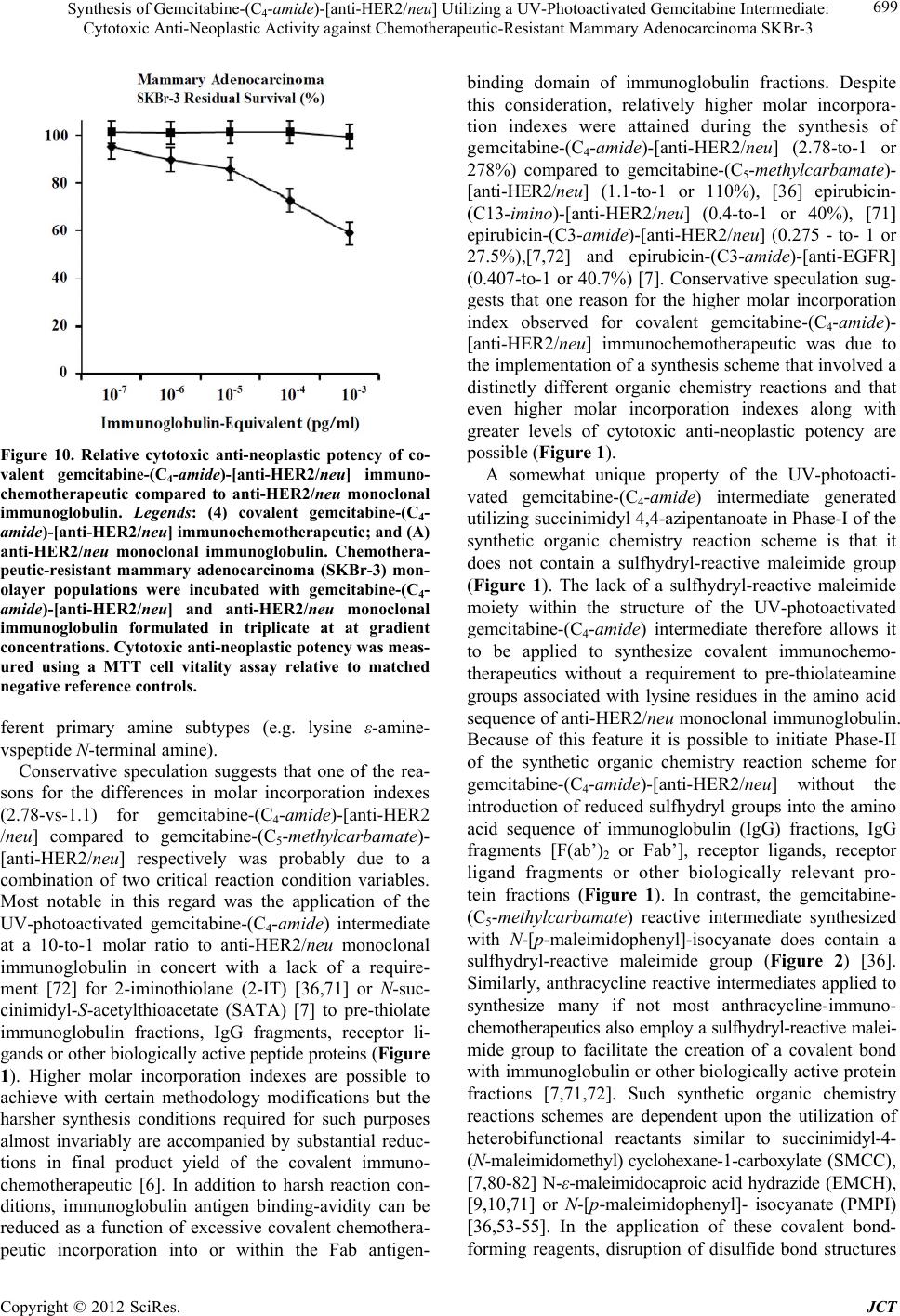

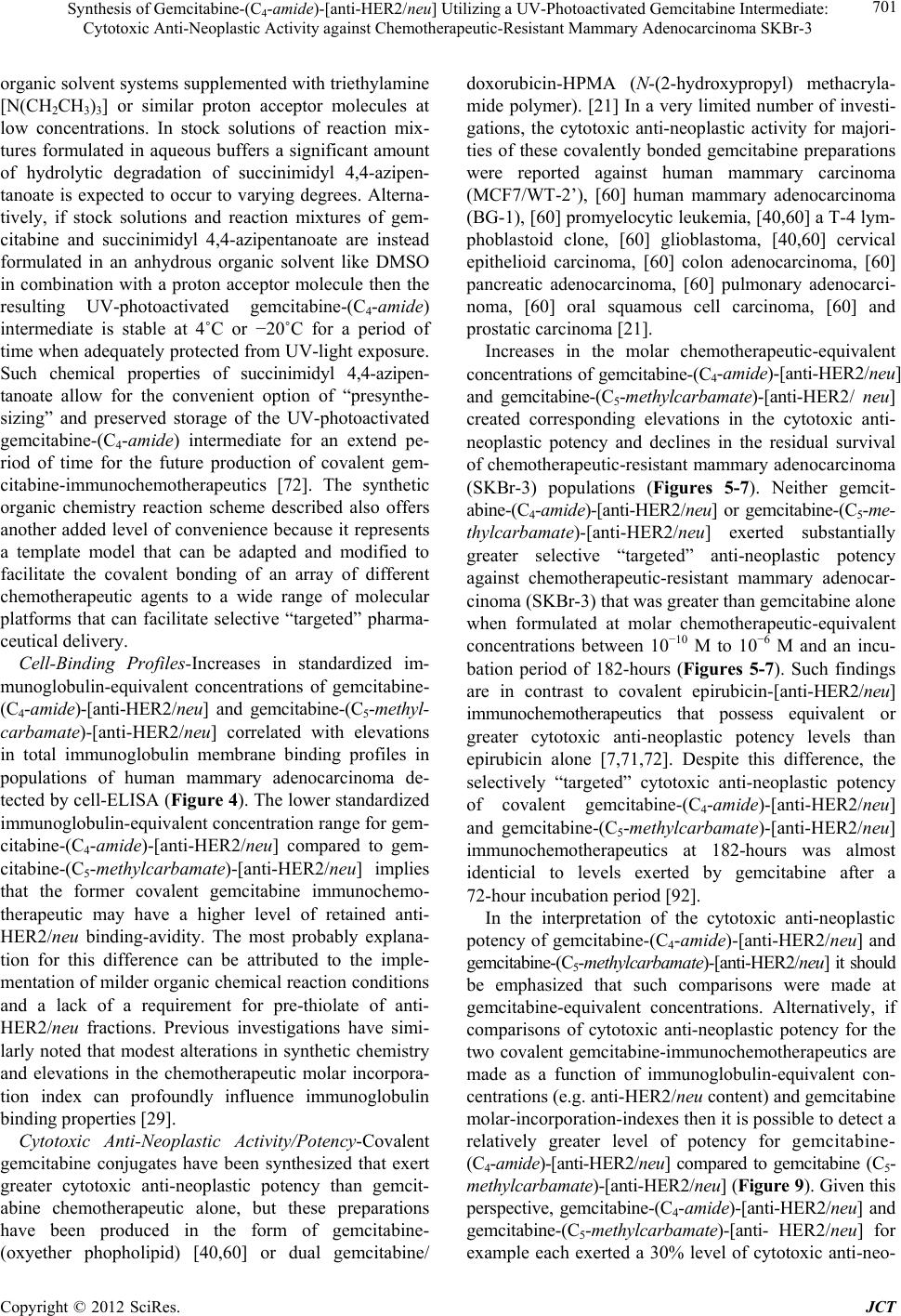

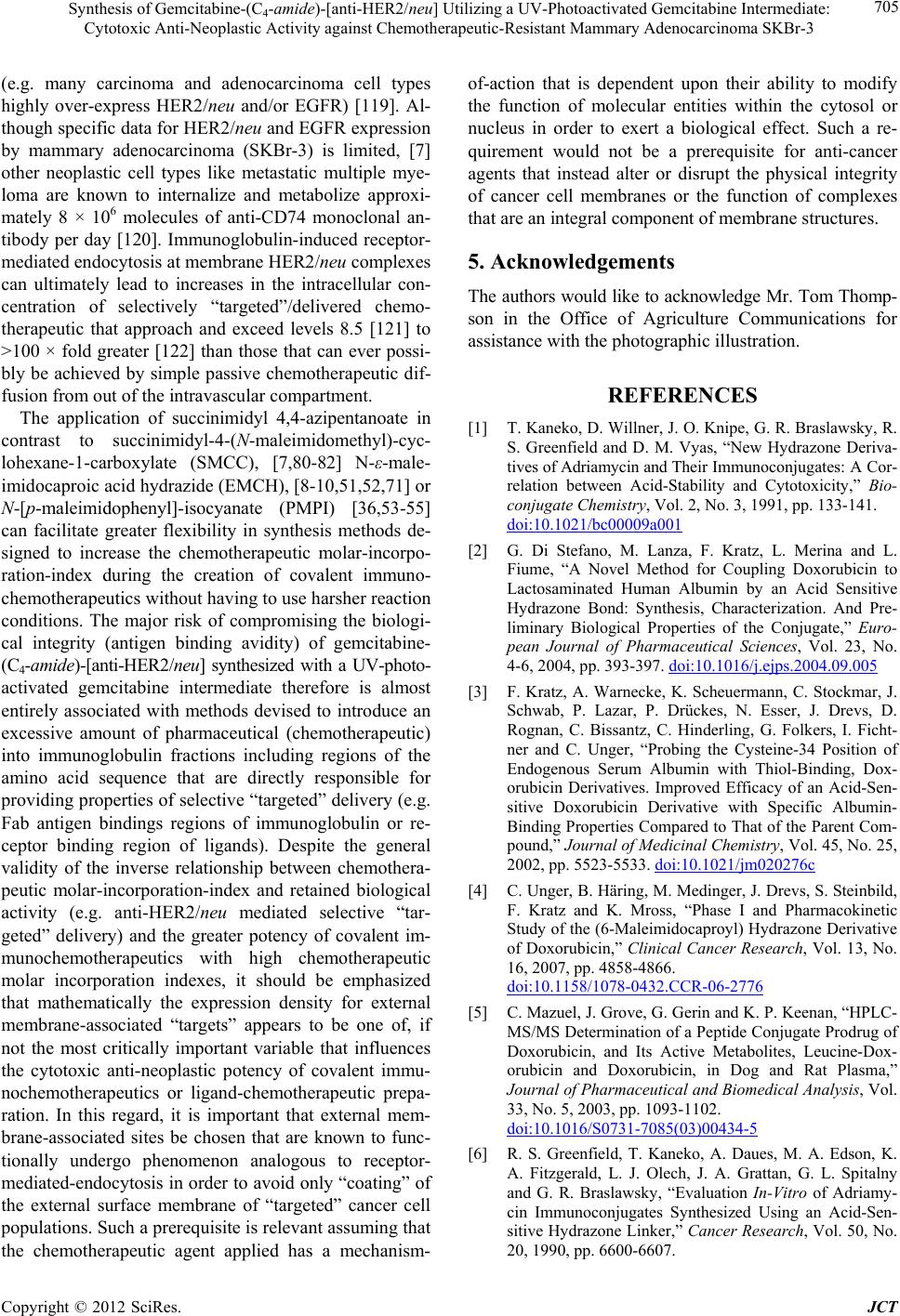

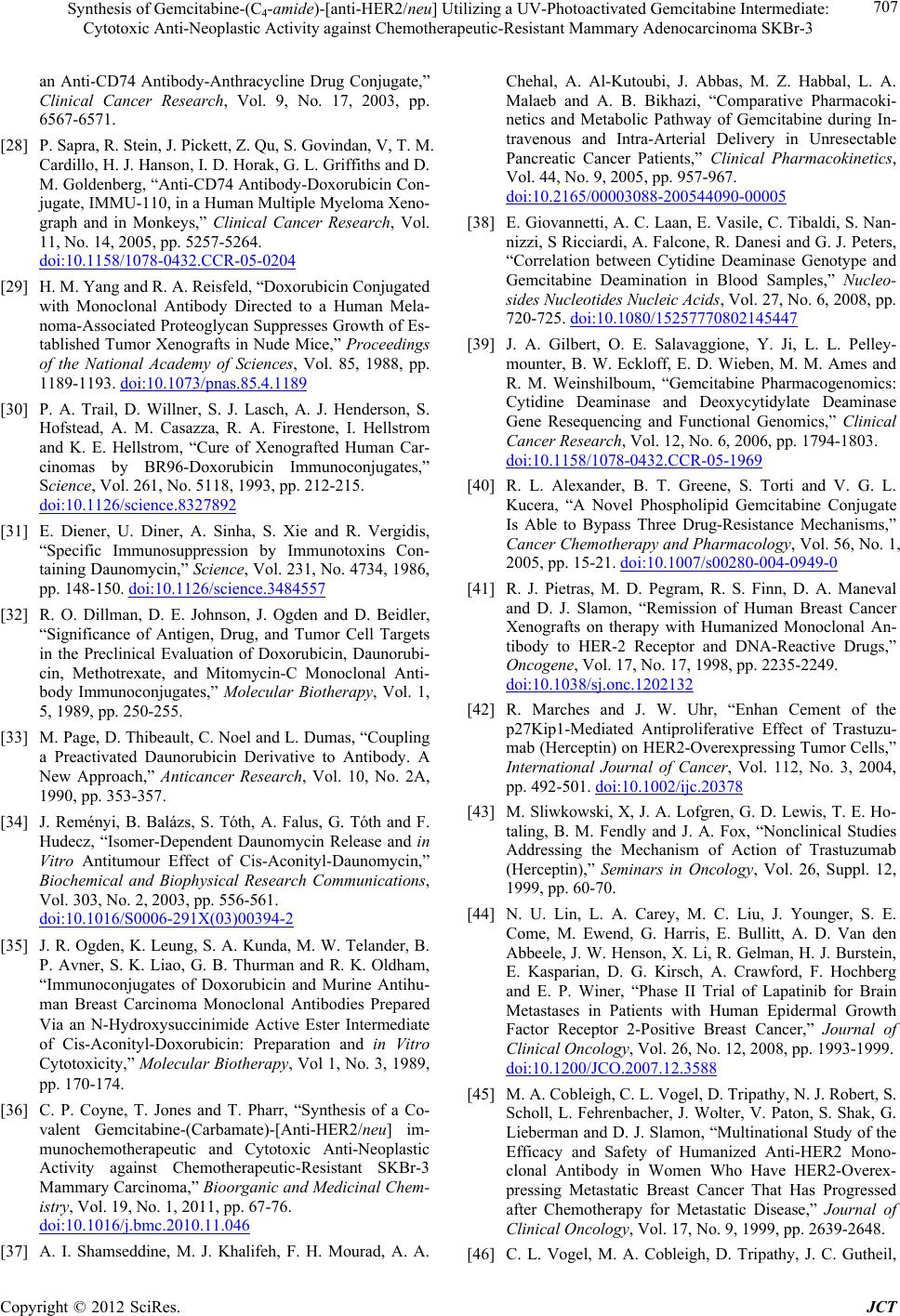

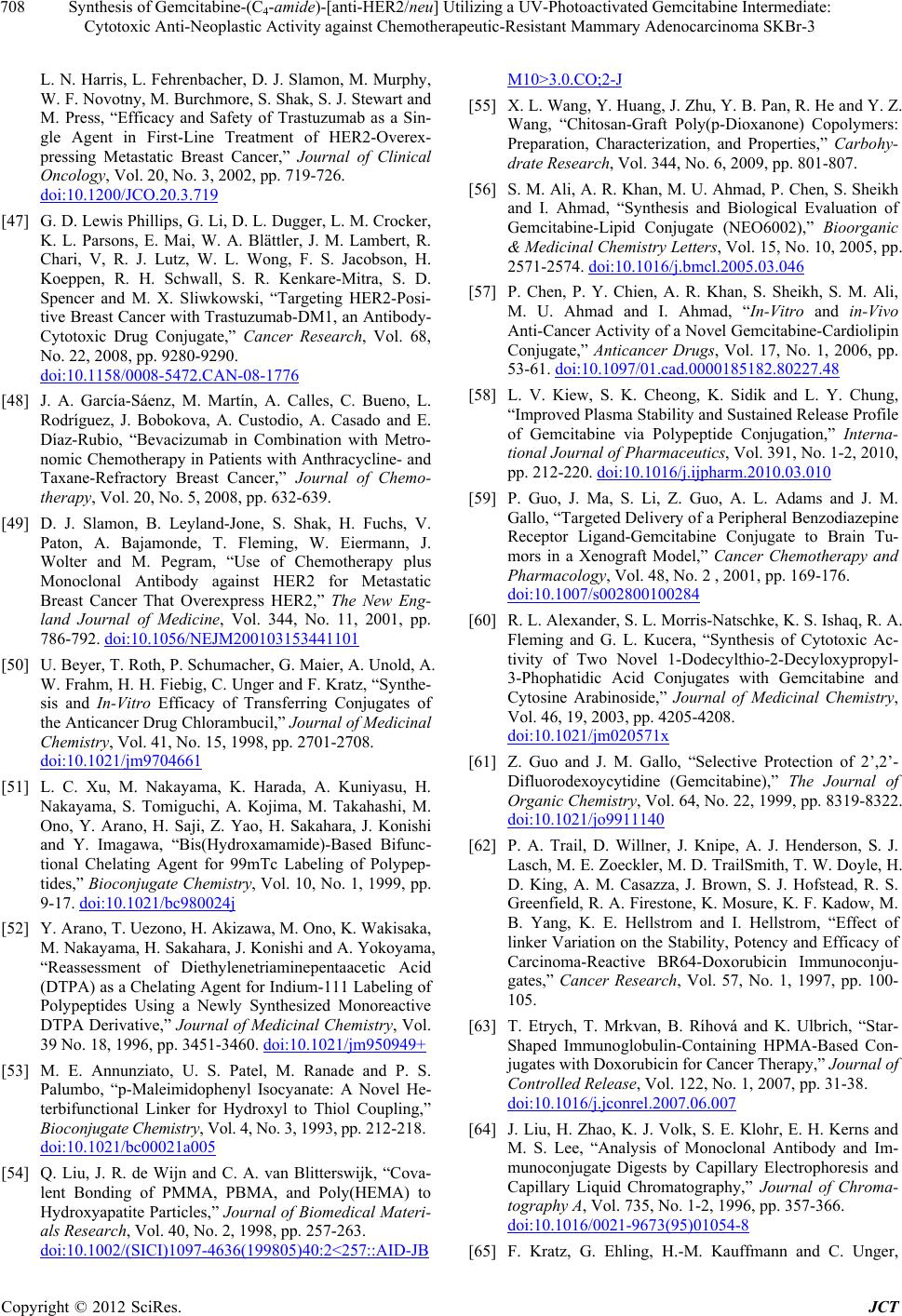

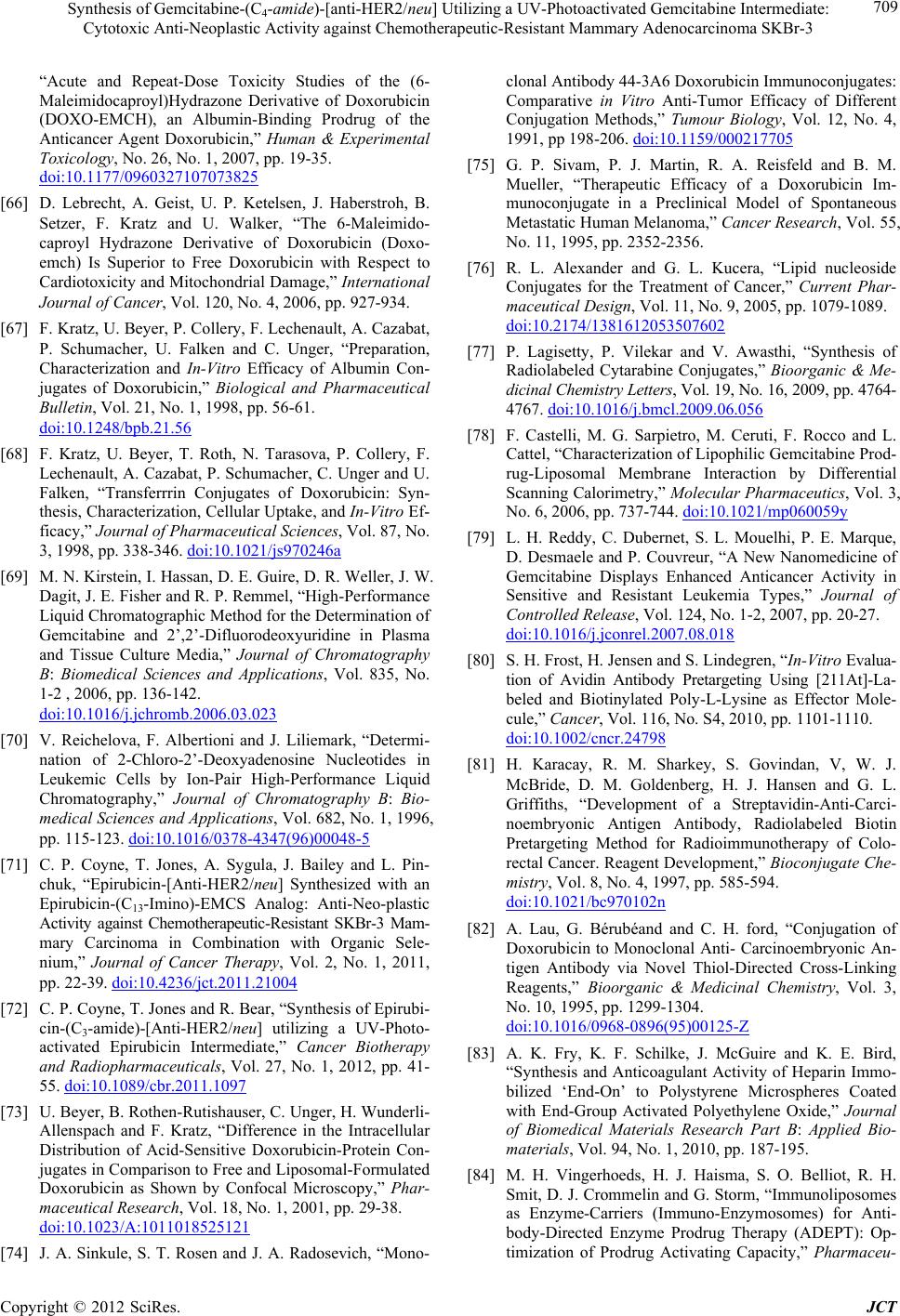

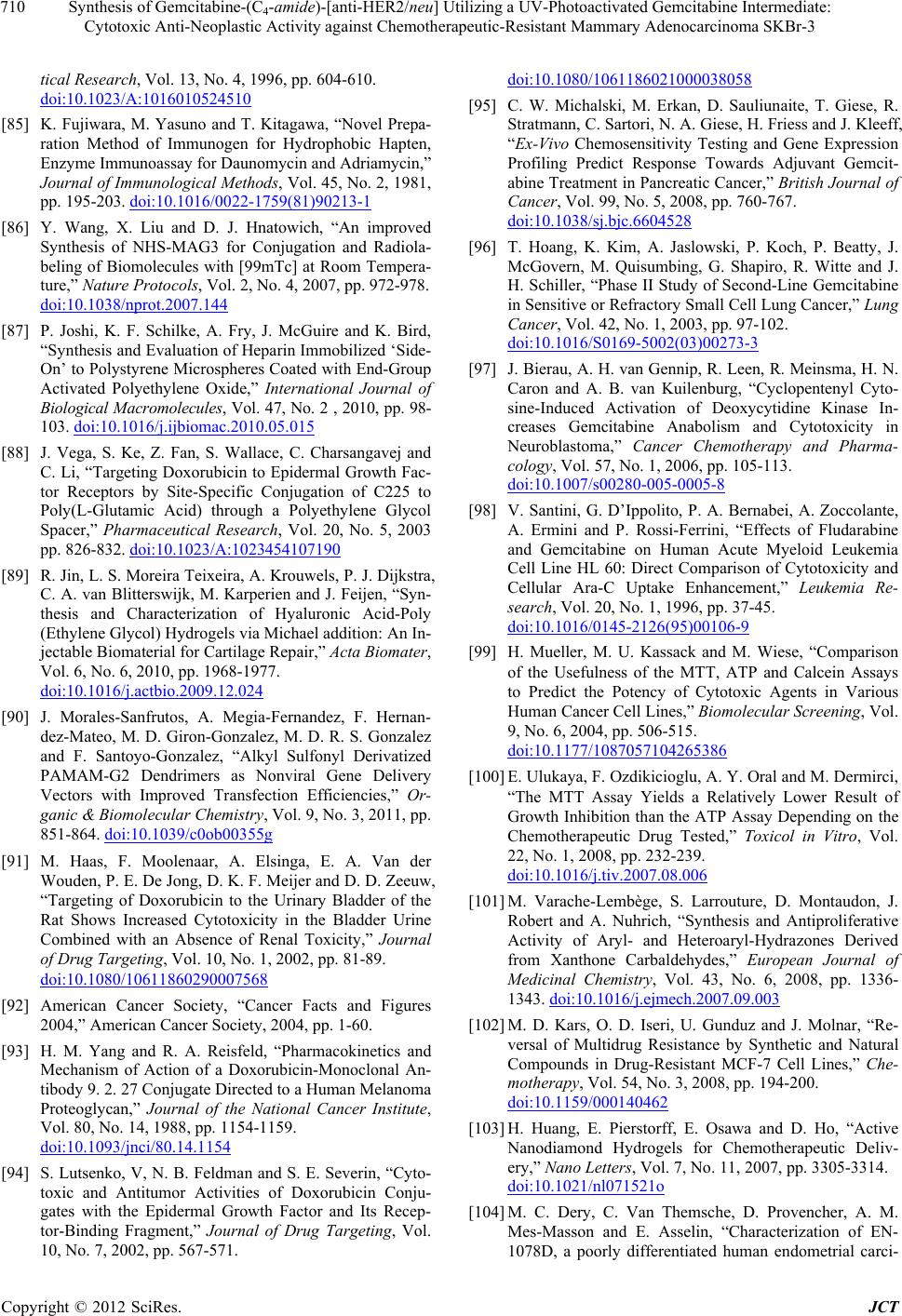

Journal of Cancer Therapy, 2012, 3, 689-711 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jct.2012.325089 Published Online October 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jct) 689 Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 Cody P. Coyne1, Toni Jones1, Ryan Bear2 1Department of Basic Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, Mississippi State University, Oktibbeha County, USA; 2Wise Cen- ter, Mississippi State University, Oktibbeha County, USA. Email: coyne@cvm.msstate.edu Received August 10th, 2012; revised September 12th, 2012; accepted September 24th, 2012 ABSTRACT Gemcitabine is a pyrimidine nucleoside analog that becomes triphosphorylated intracellularly where it competitively inhibits cytidine incorporation into DNA strands. Another mechanism-of-action of gemcitabine (diphosphorylated form) involves irreversible inhibition of the enzyme ribonucleotide reductase thereby preventing deoxyribonucleotide synthe- sis. Functioning as a potent chemotherapeutic gemcitabine promote decreases in neoplastic cell proliferation and apop- tosis which is frequently found to be effective for the treatment of several leukemias and a wide spectrum of carcinomas. A brief plasma half-life in part due to rapid deamination and chemotherapeutic-resistance restricts the utility of gemcit- abine in clinical oncology. Selective “targeted” delivery of gemcitabine represents a potential molecular strategy for simultaneously prolonging its plasma half-life and minimizing innocient tissues and organ systems exposure to chemo- therapy. The molecular design and an organic chemistry based synthesis reaction is described that initially generates a UV-photoactivated gemcitabine intermediate. In a subsequent phase of the synthesis method the UV-photoactivated gemcitabine intermediate is covalently bonded to a monoclonal immunoglobulin yielding an end-product in the form of gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu]. Analysis by SDS-PAGE/chemiluminescent auto-radiography did not detect evidence of gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] polymerization or degradative fragmentation while cell-ELISA demonstrated retained binding-avidity for HER2/neu trophic membrane receptor complexes highly over-expressed by chemotherapeutic-resistant mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3). Compared to chemotherapeutic-resistant mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3), the covalent immunochemotherapeutic, gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] is antici- pated to exert greater levels of cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency against other neoplastic cell types like pancreatic car- cinoma, small-cell lung carcinoma, neuroblastoma, glioblastoma, oral squamous cell carcinoma, cervical epitheliod carcinoma, or leukemia/lymphoid neoplastic cell types based on their reported sensitivity to gemcitabine and gemcit- abine covalent conjugates. Keywords: Gemcitabine; HER2/neu; UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine-(C4-amide) Intermediate; Organic Chemistry Reaction; Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu]; Covalent Bond Synthesis; Gemcitabine (C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu]; Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Potency; Chemotherapeutic-Resistant; Mammary Adenocarcinoma; Cell-ELISA; SDS-PAGE; Immunodetection; Chemiluminescent Autoradiography 1. Introduction The anthracyclines have historically been the most common class of chemotherapeutic covalently bonded to (large) molecular platforms that can facilitate “selective” targeted delivery [1-25]. The spectrum of anthracylines utilized to synthesize covalent anthracycline-immuno- chemotherapeutics to date has largely included doxoru- bicin [26-30] and to a lesser extent daunorubicin [31-33] or epirubicin [7,34,35]. The chemotherapeutic, gemcitabine has in contrast to the anthracyclines been less frequently bonded cova- lently to large molecular weight platforms that can fa- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 690 cilitate selective “targeted” delivery [36]. Gemcitabine is a deoxycytidine nucleotide analog that intracellularly has a chemotherapeutic mechanism-of-action that involveds it being triphosphoralated in a manner that allows it to substitute for cytidine during DNA transcription resulting in incorporation into DNA strands and inhibition of DNA polymerase biochemical activity. A second mechanism- of-action for gemcitabine involves inhibition and inacti- vation of ribonucleotide reductase ultimately resulting in suppression of deoxyribonucleotide synthesis in concert with diminished DNA repair and reduced DNA tran- scription. Each of these mechanisms-of-action collec- tively promotes cellular apoptosis. In clinical oncology, gemcitabine is administered for the treatment certain leukemias and potentially lymphoma conditions in addi- tion to a spectrum of adenocarcinomas and carcinomas affecting the lung (e.g. non-small cell), pancrease, blad- der and esophogus. Gemcitabine has a brief plasma half-life because it is rapidly deaminated to an inactive metabolite that is rapidly eliminated through renal excre- tion into the urine [37-39]. The molecular design and synthesis of a covalent gemcitabine immunochemo- therapeutics provides several attributes that complement their ability to facilitate selective “targeted” delivery, progressive intracellular deposition, and more prolonged plasma pharmacokinetics for the gemcitabine moiety. Attributes in this regard presumably include steric hin- derance phenomenon that accounts for gemcitabine being apparently a much poorer substrate for MDR-1 (multi- drug resistance efflux pump) [40] in addition to the rapid deaminating enzyme systems, cytidine deaminase, and deoxycytidylate deaminase (following gemcitabine pho- sphorylation) when this chemotherapeutic is covalently incorporated into an immunochemotherapeutic. The molecular design, synthetic organic chemistry re- action schemes, and cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency of gemcitabine covalently bonded to large molecular weight delivery platforms has been described on only a limited scale in published reports. Due to the type and relatively low number of chemical groups (sites) available within the structure of gemcitabine there are only a small num- ber of organic chemistry reaction schemes that have been utilized to covalently bond gemcitabine to large molecu- lar weight platforms and very few reports have described the synthesis and cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency of covalent gemcitabine immunochemotherapeutics [36]. The covalent bonding of gemcitabine to immunoglobulin or ligands that have binding-avidity for trophic receptors like HER2/neu and EGFR frequently over-expressed in breast cancer and by many other carcinomas or adeno- carcinomas provides an opportunity to achieve additive or synergistic levels of cytotoxic anti-neoplastic po- tency. Monoclonal anti-HER2/neu and anti-EGFR im- munoglobulin fractions provide a molecular mechanism for achieving both selective “targeted” chemotherapeutic delivery and growth suppression of neoplastic cell types that biologically are heavily dependent on the over-ex- pression of HER2/neu and EGFR when they function as trophic receptor complexes. Unfortunately when applied as a monotherapy, anti-HER2/neu, anti-EGFR and other therapeutic monoclonal immunoglobulin fractions re- portedly have an inability to exert levels of cytotoxic activity sufficient to independently resolve many neo- plastic disease states [41-47] unless they are applied in concert with conventional chemotherapy or other anti- cancer modalities [48,49]. Despite general familiarity with how anti-HER2/neu affects the vitality of cancer cell populations and it’s application in clinical oncology, there has been surprisingly little research devoted to the molecular design, chemical synthesis and potency evalu- ation of covalent gemcitabine immunochemotherapetuics [36]. Even fewer reports exist to date that describe simi- lar aspects for covalent gemcitabine-[anti-HER2/neu] immunochemotherapeutics and their potential to exert selectively “targeted” cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency against chemotherapeutic-resis-tant mammary adenocar- cinoma [36] or other cancer cell types. 2. Materials and Methods 2.1. Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Immunochemotherapeutic Synthesis Phase-I Synthesis Scheme for UV-Photoactivated Gem- citabine-(C4-amide) Intermediates-The cytosine-like C4- amine of gemcitabine (0.738 mg, 2.80 × 10–3 mmoles) was reacted at a 2.5:1 molar-ratio with the amine-reactive N-hydroxysuccinimide ester “leaving” complex of suc- cinimidyl 4,4-azipentanoate (0.252 mg, 1.12 × 10–3 mmoles) in the presence of triethylamine (TEA 50 mM final concentration) utilizing dimethylsulfoxide as an anhydrous organic solvent system (Figures 1 and 2). The reaction mixture formulated from stock solutions of gemcitabine and succinimidyl 4,4-azipentanoate was con- tinually stirred gently at 25˚C over a 4-hour incubation period in the dark and protected from exposure to light. The relatively long incubation period of 4 hours was utilized to maximize degradation of the ester group of any residual succinimidyl 4,4-azipentanoate that may not of reacted in the first 30 to 60 minutes with the C4 cyto- sine-like amine group of gemcitabine. Phase-II Synthesis Scheme for Covalent Gemcit- abine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu ] Immunochemothera- peutic Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine In- termediate-Immunoglobulin fractions of anti-HER2/neu (1.5 mg, 1.0 × 10–5 mmoles) in buffer (PBS: phosphate 0.1, NaCl 0.15 M, EDTA 10 mM, pH 7.3) were com- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT 691 1 2 3 HP-TLC Analysis Figure 1. Schematic illustration of the organic chemistry reaction schemes utilized in the 2-phase synthesis regimen for gem- citabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu]. Legends for Reactions: (Phase-I) creation of a covalent amide bond at the C4 cyto- sine-like monoamine of gemcitabine and the ester group of succinimidyl 4,4-azipentanoate resulting in the creation of a cova- lent UV-photoactivated gemcitabine-(C4-amide) intermediate. The reaction results in the liberation of the succinimide “leav- ing” complex. (Phase-II) creation of a covalent bond between the UV-photoactivated gemcitabine-(C4-amide) intermediate and chemical groups within the amino acid sequence of anti-HER2/neu monoclonal immunoglobulin initiated by exposure to UV light (354 nm). Legends for HP-TLC Analysis: Reaction of the N-hydroxy-succ inymide groups of disuc cinimidyl glutarate with the C4 cytosine like “ring amine” of gemcitabine. (Lane-1) gemcitabine reference control; (Lane-2) gemcitabine reacted with disuccinmidyl glutarate in DMSO with Tri-e thylamide at 50 mM final concentration; and (Lane-3) gemcitabine reacted with disuccinmidyl glutarate in DMSO and ddH2O (2:1 v/v). Reaction products were developed by silic a gel HP-TLC using a mobile phase of propanol/ethanol (80:20 v/v) and images visualized under UV light (254 nm). Figure 2. Molecular design and chemical composition of two covalent gemcitabine-immunochemotherapeutics. Legends: (Top-Panel) Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] synthesized using a 2-stage organic chemistry reaction scheme that initially creates a covalent bond at the C4 cytosine-like amine group of gemcitabine. (Bottom-Panel) Gemcitabine-(C5-me- thylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] synthesized using a 3-stage organic chemistry reaction scheme that formed covalent bonds at the chemotherapeutic C5-methylhydroxy group and at/to thiolated lysine α-amine groups residing within the amino acid se- quence of anti-HER2/neu monoclonal immunoglobulin fractions.  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 692 bined at a 1:10 molar-ratio with the UV-photoactivated gemcitabine-(C4-amide) intermediate (Phase- 1 end prod- uct) and allowed to gently mix by constant stirring for 5 minutes at 25˚C in the dark. The photoactivated group of the gemcitabine-(C4-amide) intermediate was then re- acted with side chains of amino acid residues within the sequence of anti-HER2/neu monoclonal immunoglobulin during a 15 minute exposure to UV light at 354 nm (re- agent activation range 320 - 370 nm) in combination with constant gentle stirring (Figures 1 and 2). Residual che- motherapeutic was removed from the covalent gemcit- abine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] immunochemotherapeu- tic applying micro-scale column chromatography follow- ing pre-equilibration of exchange media with PBS (phos- phate 0.1, NaCl 0.15 M, pH 7.3). 2.2. Gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)- [anti-HER2/neu] Immunochemotherapeutic Synthesis Phase-I: Immunoglobulin Thiolation at Lysine ε-Amine Groups-A purified fraction of monoclonal immunoglobu- lin with binding-avidity specifically for human HER2/ neu (ErbB-2, CD 340) was utilized for the semi-synthe- sis of gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] [36]. Desiccated anti-HER2/neu monoclonal immuno- globulin (1.5 mg) was combined with 2-imino-thiolane (2-IT: 6.5 mM final concentration) in PBS (0.1 M, pH 8.0, 250 µl) and incubated at 25˚C for 1.5 hours in com- bination with simultaneous constant gentle stirring [8, 50-52]. Thiolated anti-HER2/neu monoclonal immuno- globulin was then buffer exchanged into PBS-EDTA (phosphate 0.1, NaCl 0.15 M, EDTA 10 mM, pH 7.3) using micro-scale column chromatography. Moles of reduced sulfhydryl groups covalently introduced into anti-HER2/neu monoclonal immunoglobulin was meas- ured with a 5,5’-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB reagent) based assay. The average number of thiolated lysine ε-amine groups introduced into anti-HER2/neu fractions (R-SH/IgG) was 3:1 based on results with 2-IT reagent. Phase-II: Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarba- mate)-PMPI Sulfhydryl Reactive Intermediate-Gemcit- abine in DMSO (0.738 mg, 2.80 × 10–3 mmoles) was combined at a 5:1 molar ratio with N-[p-maleimido- phenyl]-isocyanate (PMPI: 0.120 mg, 5.60 × 10–4 mmoles) [36,53-55] and allowed to mix by constant gentle stirring at 25˚C for 3.5 hours. Under these conditions the PMPI isocyanate moiety exclusively reacts with hydroxyl (R- OH) groups and preferentially creates a carbamate cova- lent bond at the terminal C5-methylhydroxy group of gemcitabine [36,40,56-61]. The highly selective reaction is reportedly complete within 2 hours under the condi- tions applied as described. Gemcitabine was formulated at a large molar excess to deplete un-reacted PMPI and maximize synthesis of the sulfhydryl-reactive maleimide intermediate. Phase-III: Covalent Reaction of Gemcitabine-(C5- methylcarbamate)-PMPI Intermediate with Thiolated Im- munoglobulin-The gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-PMPI intermediate with a maleimide moiety that exclusively reacts with reduced sulfhydryl (R-SH) groups was com- bined at a 1.5:1 molar ratio with thiolated terminal lysine ε-amines in anti-HER2/neu monoclonal immunoglobulin fractions (PBS-EDTA: phosphate 0.1, NaCl 0.15 M, EDTA 10 mM, pH 7.3) and the formulation mixture in- cubated with constant stirring at 25˚C for 2 hours [2,3,7,9,25,26,28,36,53,62-66]. Similar synthesis strate- gies in concept have previously been applied to produce covalent anthracycline immunochemotherapeutic prepa- rations [7,8,50,51,67,68]. Because of the selective char- acteristics of the synthesis scheme employed to produce the sulfhydryl-reactive gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)- PMPI intermediate and the limited duration of chemical stability associated with it’s maleimide moiety in aque- ous buffers, the preparation was directly mixed with thiolated anti-HER2/neu fractions [7,36,51]. Residual gemcitabine was removed from the final covalent gem- citabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] immuno- chemotherapeutic end-product applying microscale col- umn chromatography following pre-equilibration of ex- change media with PBS (phosphate 0.1, NaCl 0.15 M, pH 7.3) yielding a homogenous purified preparation (Figure 2). 2.3. Analysis and Property Characteristics General Analysis-Quantitation of the amount of non- covalently bound gemcitabine contained within cova- lent gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gem- citabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] im-mu- nochemotherapeutics following separation by column chromatography was determined by measured absorb- ance at 265 - 268 nm [69,70] for the resulting supernatant after precipitation of gemcitabine-immuno-chemothera- peutics with methanol:acetonitrile (1:9 v/v). In contrast to the anthracyclines, [7,71,72] gemcitabine can not be measured directly within covalent immuno- chemotherapeutic preparations by spectrophotometric ab- sorption [36]. Alternatively it is possible to calculate the amount of gemcitabine that has been covalent incurpo- rated into immunochemotherapeutics by measuring re- sidual unbound gemcitabine before and after the Phase II reaction or by measuring the difference in non-chemo- therapeutic-occupied sites associated with either amine or reduced sulfhydryl groups within anti-HER2/neu mo- noclonal immunoglobulin compared to gemcitabine-im- munochemotherapeutics [36,51,52]. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 693 Determination of the gemcitabine molar-incorpora- tion-Index and gemcitabine molar-equivalent-concentra- tions for gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[antiHER2/ neu] were calculated using measurements for the relative difference in moles of reduced sulfhydryl groups (e.g. R-SH: cystine amino acid residues and sulfhydryl groups introduced with Traut’s reagent) contained within thio- lated anti-HER2/neu fractions relative to the covalent gemcitabine-immuno-chemotherapeutic following sepa- ration by column chromatography [36,51,52]. Reduced sulfhydryl groups were measure by combining anti-HER2/ neu or gemcitabine (C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/ neu] in phosphate buffered saline (0.1 M, pH 7.4) with 5,5’-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) formulated in sodium phosphate-EDTA buffer (DTNB: 78 µg/ml with EDTA 1 mM in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer 0.1 M, pH 8.0). Spectrophotometric absorbance of mixtures formulated at 1:1 v/v (e.g. 250 µl each) was measured at 412 nm fol- lowing incubation at 25˚C for 15 minutes. The amount and concentration of sulfhydryl groups was then calcu- lated utilizing a linearized standard curve generated with reference control solutions of cysteine HCl monohy- drate formulated at known concentrations (molar extinc- tion coefficient: 14,150 M–1·cm–1). Determination of the immunoglobulin concentration for covalent gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] im- munochemotherapeutics was determined by measuring spectrophotometric absorbance at 280 nm in combina- tions with utilizing a 235 nm-vs-280 nm standardized reference curve in order to accommodate for any poten- tial absorption profile over-lap at 280 nm between gem- citabine and immunoglobulin. Mass/Size-Dependent Separation of Gemcitabine-Im- munochemotherapeutics by Non-Reducing SDS-PAGE- Covalent gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine (C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] im- munochemotherapeutics in addition to a anti-HER2/neu immunoglobulin reference control fraction were ad- justed to a standardized protein concentration of 60 µg/ml and then combined 50/50 v/v with conventional SDS-PAGE sample preparation buffer (Tris/glycerol/ bromphenyl blue/SDS) formulated without 2-mercap- toethanol or boiling. Each covalent gemcitabine immu- nochemotherapeutic, the reference control immuno- globulin fraction (0.9 µg/well) and a mixture of pre- stained reference control molecular weight markers were then developed by non-reducing SDS-PAGE (11% acry- lamide) performed at 100 V constant voltage at 3˚C for 2.5 hours. Immunodetection Analyses-Covalent gemcitabine-(C4- amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine (C5-methyl- carbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] immunochemo-therapeutics following mass/size-dependent separation by non-re- ducing SDS-PAGE were equilibrated in tank buffer de- void of methanol. Mass/size-separated gemcitabine and anthracycline anti-HER2/neu immunochemotherapeutics contained in acrylamide SDS-PAGE gels were then transferred laterally onto sheets of nitrocellulose mem- brane at 20 volts (constant voltage) for 16 hours at 2˚C to 3˚C with the transfer manifold packed in crushed ice. Nitrocellulose membranes with laterally-transferred immunochemotherapeutics were then equilibrated in Tris- buffered saline (TBS: Tris HCl 0.1 M, NaCl 150 mM, pH 7.5, 40 ml) at 4˚C for 15 minutes followed by incubation in TBS blocking buffer solution (Tris 0.1 M, pH 7.4, 40 ml) containing bovine serum albumin (5%) for 16 hours at 2˚C to 3˚C applied in combination with gentle hori- zontal agitation. Prior to further processing, nitrocellu- lose membranes were vigorously rinsed in Tris buffered saline (Tris 0.1 M, pH 7.4, 40 ml, n = 3x). Rinsed BSA-blocked nitrocellulose membranes de- veloped for immunodetection (Western-blot) analyses were incubated with biotinylated goat anti-murine IgG (1:10,000 dilution) at 4˚C for 18 hours applied in combi- nation with gentle horizontal agitation. Nitrocellulose membranes were then vigorously rinsed in TBS (pH 7.4, 4˚C, 50 ml, n = 3) followed by incubation in blocking buffer (Tris 0.1 M, pH 7.4, with BSA 5%, 40 ml). Blocking buffer was decanted from nitrocellulose mem- brane blots and then rinsed in TBS (pH 7.4, 4˚C, 50 ml, n = 3) before incubation with strepavidin-HRPO (1:100,000 dilution) at 4˚C for 2 hours applied in combi- nation with gentle horizontal agitation. Prior to chemi- luminescent development nitrocellulose membranes were vigorously rinsed in Tris buffered saline (Tris 0.1 M, pH 7.4, 40 ml, n = 3). Development of nitrocellulose mem- branes by chemiluminescent autoradiography following processing with conjugated HRPO-strepavidin required incubation in HRPO chemiluminescent substrate (25˚C, 5 to 10 mins.). Autoradiographic images were acquired by exposing radiographic film (Kodak BioMax XAR) to nitrocellulose membranes sealed in transparent ultraclear re-sealable plastic bags. Mammary Adenocarcinoma Tissue Culture Cell Cul- ture—The chemotherapeutic-resistant (SKBr-3) human mammary adenocarcinoma cell line was utilized as an ex-vivo neoplasia model. Mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) characteristically over-expresses epidermal growth factor receptor 1 (EGFR, ErbB-1, HER1) and highly over-expresses epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (EGFR2, HER2/neu, ErbB-2, CD340, p185) at 2.2 × 105/cell and 1 × 106/cell respectively. Populations of the mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) were propagated in 150-cc2 tissue culture flasks con- taining McCoy’s 5a Modified Medium supplemented Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 694 with fetal bovine serum (10% v/v) and penicillin-strep- tomycin at a temperature of 37˚C under a gas atmosphere of air (95%) and carbon dioxide (5% CO2). Tissue cul- ture media was not supplemented with growth factors, growth hormones or other growth stimulants of any type. Investigations were performed using mammary adeno- carcinoma (SKBr-3) monolayer populations at a >85% level of confluency. Cell-ELISA Total Membrane-Bound Immunoglobulin Assay-Cell suspensions of mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) were seeded into 96-well microtiter plates in aliquots of 2 × 105 cells/well and allowed to form a con- fluence adherent monolayer over a period of 48 hours. The growth media contents of individual wells was then removed manually by pipette and serially rinsed (n = 3) with PBS followed by stabilization of adherent cellular monolayers onto the plastic surface of 96-well plates with paraformaldehyde (4% in PBS, 15 minutes). Stabi- lized mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) monolayers were then incubated with gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti- HER2/neu] or gemcitabine (C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti- HER2/neu] immunoconjugates formulated at gradient concentrations of 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 5.0 and 10 µg/ml in tissue culture growth media (200 µl/well). Direct contact incubation between mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) cellular monolayers and gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti- HER2/neu] or gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti- HER2/neu] at 37˚C was performed over an incubation period of 3-hours using a gas atmosphere of air (95%) and carbon dioxide (5% CO2). Following serial rinsings with PBS (n = 3), development of stabilized mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) monolayers entailed incuba- tion with β-galactosidase conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:500 dilution) for 2 hours at 25˚C with residual unbound immunoglobulin removed by serial rinsing with PBS (n = 3). Final cell ELISA development required serial rinsing (n = 3) of stabilized cellular monolayers with PBS followed by incubation with nitrophenyl-β- D-galactopyranoside substrate (100 µl/well of ONPG formulated fresh at 0.9 mg/ml in PBS pH 7.2 containing MgCl2 10 mM, and 2-mercaptoethanol 0.1 M). Absorb- ance within each individual well was measured at 410 nm (630 nm reference wavelength) after incubation at 37˚C for a period of 15 minutes. Cell Vitality Stain-Based Assay for Measuring Cyto- toxic Anti-Neoplastic Potency-Individual preparations of gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2 /neu] and gem- citabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] were for- mulated in growth media at standardized chemotherapeu- tic-equivalent concentrations of 10–10, 10–9, 10–8, 10–7, and 10–6 M (final concentration). Each chemotherapeu- tic-equivalent concentration of covalent immunochemo- therapeutic was then transferred in triplicate into 96-well microtiter platesm containing mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) monolayers (growth media 200 µl/well). Cova- lent gemcitabine immunochemotherapeutics where then incubated in direct contact with monolayer mammary adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 populations for a period of 182- hours at (37˚C under a gas atmosphere of air (95%) and carbon dioxide/CO2 (5%). Following the initial 72-hour incubation period, mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) populations were replenished with fresh tissue culture media with or without covalent gemcitabine-immuno- chemotherapeutics. Cytotoxic potencies for gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti- HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)[anti- HER2/neu] were measured by removing all contents within the 96-well microtiter plates manually by pipette followed by serial rinsing of monolayers (n = 3) with PBS and incubation with 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl] -2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide vitality stain reagent formulated in RPMI-1640 growth media devoid of pH indicator or bovine fetal calf serum (MTT: 5 mg/ml). During an incubation period of 3 - 4 hours at 37˚C under a gas atmosphere of air (95%) and carbon dioxide (5% CO2) the enzyme mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase was allowed to convert the MTT vitality stain reagent to navy-blue formazone crystals within the cytosol of mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) populations. Con- tents of the 96-well microtiter plate was then removed, followed by serial rinsing with PBS (n = 3). The resulting blue intracellular formzone crystals were dissolved with DMSO (300 µl/well) and then the spectrophotometric absorbance of the blue-colored supernantant measured at 570 nm using a computer integrated microtiter plate reader. 3. Results Molar-Incorporation Index-Size-separation of covalent immunochemotherapeutics like gemcitabine-(C4-amide)- [anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)- [anti-HER2/neu] by micro-scale exchange column chro- matography consistently yields preparations that contain <4.0% of residual chemotherapeutic that is not cova- lently bound to the immunoglobulin fraction [7,36,71,72]. Small residual amounts of non-covalently bound chemo- therapeutic remaining within covalent immunochemo- therapeutic preparations is generally considered to not be available for further removal through any additional se- quential column chromatography separations [73]. The calculated estimate of the molar-incorporation-index for the covalent gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] immunochemotherapeutic was 2.78 utilizing the organic chemistry reaction scheme that forms an amide bond at the C4 cytosine-like amine of gemcitabine resulting in the initial synthesis of the UV-photoactivated gemcitabine- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT 695 (C4-amide) intermediate (Figures 1 and 2). The mo- lar-incorporation-ration of 2.78-to-1 for gemcitabine- (C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] was relatively larger than the 1.1-to-1 gemcitabine molar-incorporation-index at- tained during the synthesis of gemcitabine-(C5-me-thyl- carbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] [36]. noglobulin-equivalent concentrations formulated at 0.010, 0.025, 0.050, 0.250, and 0.500 µg/ml (Figure 4). In order to detect elevations in total membrane-bound gemcit- abine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] standard- ized total immunoglobulin-equivalent concentrations had to alternatively be formulated at 0.5, 1.0, 5.0 and 10.0 µg/ml (Figure 4). Collectively each of these sets of cell-ELISA findings serve to validate the retained selec- tive binding-avidity of gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti- HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)- [anti-HER2/neu] for external membrane HER2/neu re- Molecular Weight Profile Analysis-Mass/size sepa- ration of covalent gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/ neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/ neu] immunochemotherapeutics by SDS-PAGE in com- bination with immunodetection analysis (Western blot) and chemiluminescent autoradiography recognized a sin- gle primary condensed band of 150-kDa between a mo- lecular weight range of 5.0-kDa to 450-kDa (Figure 3) Patterns of low-molecular-weight fragmentation (prote- olytic/hydrolytic degradation) or large-molecular-weight immunoglobulin polymerization were not detected (Fig- ure 3). The observed molecular weight of 150-kDa for both gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gem- citabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] directly corresponds with the known molecular weight/mass of reference control anti-HER2/neu monoclonal immuno- globulin fractions (Figure 3). Analogous results have been reported for similar covalent immunochemothera- peutics [2,7,36,71,72,74]. 150 kDa 1 2 3 Figure 3. Characterization of the major molecular weight profile for covalent gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] im- munochemotherapeutics compared to anti-HER2/neu mono- clonal immunoglobulin. Legends: (Lane-1) murine anti- human HER2/neu monoclonal immunoglobulin reference control; (Lane-2) covalent gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti- HER2/neu] immunochemotherapeutic; and (Lane-3) cova- lent gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-H ER2/ ne u] im- munochemotherapeutic. Covalent gemcitabine immuno- chemotherapeutics or anti-HER2/ neu monoclonal immu- nogloublin were size-separated by non-reducing SDS-PAGE followed by lateral transfer onto sheets of nitrocellulose membrane to facilitate detection with biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG immunoglobulin. Subsequent analysis en- tailed incubation of nitrocellulose membranes with stre- pavidin-HRPO in combination with the use of a HRPO chemiluminescent substrate for acquisition of autoradio- graphy images. Cell-Binding Analysis-Total bound immunoglobulin in the form of gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] or gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] on the external surface membrane of adherent mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) populations was measured by cell-ELISA (Figure 4). Greater total membrane-bound gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] was detected with progressive increases in standardized total immu- Figure 4. Detection of total anti-HER2/neu immunoglobulin in the form of gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] bound to the exterior surface membrane of chemotherapeutic-resistant mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3). Legends: (Left-Panel) gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu]; and (Right-Panel) gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu]. Monolayer populations of mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) were incubated with the covalent gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] or gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] immunochemotherapeutics over a 4-hour pe riod and total immunoglobulin bound to the exterior sur f ace membr a ne w a s then measured by cell-ELISA.  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 696 ceptor sites highly over-expressed at 1 × 106/cell on the exterior surface membrane of mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) populations (Figure 4) [36]. Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Potency Analysis-Gemcitabine- (C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcar- bamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] exerted 41.1% and 30.8% maxi- mum selective “targeted” cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency (58.9% and 69.2% residual survival) against chemothera- peutic-resistant mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) at the gemcitabine-equivalent concentration of 10−6 M respectively (Figures 5-7). Profiles for the cytoto- xic anti-neoplastic potency of gemcitabine-(C4-amide)- [anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)- [anti- HER2/neu] after a 182-hour incubation period were highly analogous to gemcitabine chemotherapeutic fol- lowing a 72-hour incubation period at the gemcitabine- equivalent concentrations of 10−10 M, 10−9 M, 10−8 M, 10−7 M and 10−6 M (Figures 5 and 6). The cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency of gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti- HER2/neu], gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/ neu] and gemcitabine after a 182-hour incubation period were essentially equivalent at the gemcitabine-equivalent concentrations of 10−10 M and 10−9 M but not at 10−7 M or 10−6 M (Figures 5 and 7) [36]. Mean maximum cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potencies for gemcitabine-(C4-amide)- [anti-HER2/neu] at 182-hours, gemcitabine at 72-hours, and gemcitabine at 182-hours were 41.1%, 48.0% and 88.3% (58.9%, 52.0% and 11.7% residual survival) at the gemcitabine-equivalent concentration of 10-M respec- tively (Figure 5). Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/ neu] and gemcitabin-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/ neu] immunochemotherapeutic both exerted profiles for cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency against chemothera- peutic mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) that were similar to epirubicin-(C3-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] but only at the chemotherapeutic-equivalent concentrations of 10−10 M, 10−9 M and 10−8 M respectively (Figure 8) [71]. The level of cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency for epirubicin-(C3-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] was substantially higher at the chemotherapeutic-equivalent concentrations of 10−7 M and 10−6 M after a 72-hour incubation period (Figure 8). Mean maximum levels of anti-neoplastic potency for gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu], gem- citabin-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] and epi- ribicin (C13-imino )-[anti-HER2/neu] were 41.1% (182- hours), 30.8% (182-hours) and 88.5% (72-hours) at the chemotherapeuticequivalent concentration of 10−6 M re- spectively (Figures 5-8). Comparison of the cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency of gemcitabine-( C 4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine- (C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] as a function of immunoglobulin-equivalent concentrations (standardized anti-HER2/neu content) and gemcitabine molarincorpora- tion-index detected distinct differences between the two covalent gemcitabine-immunochemo-therapeutics (Figure 9). Given this perspective, gemcitabine (C4-amide)-[anti- HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti- HER2/neu] each exerted an equivalent level of cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency against chemotherapeutic-resistant mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) at immunoglobu- lin-equivalent concentrations of 6.9 × 10–8 M and 9.1 × 10–9 M respectively (Figure 9). Based on these calcula- tions, gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/ neu] was ap- proximately 7.6-fold more potent than gemcitabine-(C5- methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] at a cytotoxic anti- neoplastic potency level of approximately 30% when standardized as a function of immunoglobulin-equivalent concentration (Figure 9). Monoclonal anti-HER2/neu [7,36,71,72] and anti-EGFR [7] immunoglobulin frac- tions alone between 0-to-182-hours do not exert detect- able levels of ex-vivo cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency against chemotherapeutic-resistant mam- mary adenocarci- noma (SKBr-3) which is in direct accord with previous investigations (Figure 10) [7,28,29,32, 74,75]. 4. Discussion The creation of a synthetic covalent bond between gem- citabine and monoclonal immunoglobulin, immuno- Figure 5. Differences in cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency for gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] compared to gemcitabine alone. Legends: (4) covalent gemcitabine-(C4- amide)-[anti-HER2/neu ] immunochemotherapeutic (182 hour incubation period); (•) gemcitabine chemotherapeutic (72- hour incubation period); and (A) gemcitabine chemothera- peutic (182-hour incubation period). Chemotherapeutic- resistant mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) monolayer populations were incubated with covalent gemcitabine(C4- amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] or gemcitabine formulated in trip- licate at gradient gemcitabine-equivalent concentrations. Cyto- toxic anti-neoplastic potency was measured using a MTT cell vitality assay relative to matched negative reference con- trols. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 697 globulin fragments (e.g. Fab’), receptor ligands or other biologically active protein fractions can be achieved util- izing only a relatively small array of organic chemistry reaction schemes. Chemical sites within gemcitabine that are potentially available for synthetic covalent bond re- actions include the (C4’)-NH2, (C3’)-OH and (C5’)-OH groups that can be reversibly protected utilizing di-tert- dibutyl dicarbonate [61] when non-selective organic chemistry reaction schemes are employed. Generation of a covalent bond at the C5-methylhydroxy group of gem- citabine represents one molecular approach to synthesiz- ing covalent gemcitabine-immunochemotherapeutics or gemcitabine-ligand preparations [36,40,56-61,76]. A second and possibly more infrequently utilized organic chemistry reaction involves the creation of a covalent bond at the cytosine-like C4-amine group of gemcitabine either in the form of a direct link to a “targeting” plat- form for selectivey chemotherapeutic delivery or alterna- tively for the purpose of creating a gemcitabine reactive intermediate [21,59,61,77,78]. Similar molecular strate- gies have been employed to synthesize covalent anthra- cycline immunochemotherapeutics through the formation of a covalent bond at the α-monoamine (C3-amine) group associated with the carbohydrate-like moiety of doxoru- bicin, daunorubicin, or epirubicin [5,7-9,11-16,18,19,23, 71,72].In addition to the anthracyclines [72] and gem- citabine analogous organic chemistry reaction schemes employing succinimidyl 4,4-azipentanoate could poten- tially be applied to covalently bond cytosine arabinoside (Ara-C), 5-azacytidine, cladribine (2-chloro2’deoxyadenine), clofarabine, decitabine (5-aza-2’deoxycytidine), fludara- bine, lenalidamide, troxacitabine or other chemothera- peutic (pharmaceutical) agents that contain an available mono-amine group to large molecular weight platforms like monoclonal immunoglobulin. Gemcitabine has been covalently bound to biologi- cally relevant ligands that inludes poly-L-glutamic acid (polypeptide configuration), [58] cardiolipin, [56, 57] 1-dodecylthio-2-decyloxypropyl-3-phophatidic acid, [40,60] lipid-nucleosides, [76] N-(2-hydroxypropyl) me- thacrylamide polymer (HPMA), [21] benzodiazepine re- ceptor ligand, [59,61] 4-(N)-valeroyl, 4-(N)-lauroyl, 4- (N)-stearoyl, [78] 1,1’,2-tris-noraqualenecarboxylic acid, [79] and the 4-fluoro [18F]-benzaldehyde derivative [77] for application as a positron-emitting radionuclide. Few if any published have described the molecular design, chemical synthesis and evaluation of the cytotoxic anti- neoplastic potency for gemcitabine immunochemothera- peutic created by generating a covalent bond at either the C5-methylhydroxy [36] or cytosine-like C4-amine groups of gemcitabine. In addition, there has to date been no previously published descriptions of utilizing suc- cinimidyl 4,4-azipentanoate to create a UV-photoacti- vated gemcitabine-(C4-amide) intermediate to facilitate Figure 6 .Relative cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency for gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine- (C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] compared to gemcitabine alone. Legends: (4) covalent gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/ neu] immunochemotherapeutic (182-hours); (A) covalent gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] immuno- chemotherapeutic (182-hour incubation period) and (•) gem- citabine chemotherapeutic (72-hour incubation period) Chemo- therapeutic-resistant mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) monolayer populations were incubated individually with gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2 /neu ], gemcitabine(C5-me- thylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] or gemcitabine formulated in triplicate at gradient gemcitabine-equivalent concentra- tions. Cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency w as measur ed using a MTT cell vitality assay relative to matched negative ref- erence controls. Figure 7. Relative cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency of cova- lent gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcit- abine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/ne u] immunoc hemo- therapeutics as a function of gemcitabine-equivalent con- centrations. Legends: (4) gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/ neu]; (A) gemcitabine-(C5-methyl carbonate)-[anti-HER2/neu]; and (•) gemcitabine alone. Chemot herapeutic-resistant mam- mary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) monolayer populations were incubated 182-hours with covalent gemcitabine im- munochemotherapeutics or gemcitabine formulated in trip- licate at gradient gemcitabine-equivalent concentrations. Cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency was measured using a MTT cell vitality assay relative to matched negative refer- ence controls. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 698 Figure 8. Relative cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency of the covalent immunochemotherapeutics gemcitabine-(C4-amide)- [anti-HER2/neu], gemcita bine-(C5-methyl-carbamat e)-[anti-HER2/ neu] and epirubicin-(C3- amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] formulated at chemotherapeutic-equivalent concentrations. Legends: (4) gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] at 182-hours; (•) gem- citabine-(C5-methylcarbonate)- [anti-HER 2/ neu] at 182-hours; and (A) epirubicin-(C3-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] at 72-hours. Chemotherapeutic-resistant mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr- 3) monolayer populations were incubated with the covalent immunochemotherapeutics or gemcitabine chemotherapeu- tic that were each formulated in triplicate at gradient che- motherapeutic -equivale nt concentratio ns. Cytotoxic anti- neo- plastic potency w as measured using a MTT cell vitality assay relative to matched negative reference controls. synthesis of a covalent gemcitabine immunochemothera- peutic similar to gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/ neu] (Figure 1). Analogous synthetic organic chemistry reaction schemes have however been published on a very limited scale for the production of a covalent epirubi- cin-(C3-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] immunochemotherapeu- tic [72]. Speicific attributes related to the variables of 1) che- motherapeutic chemical composition; 2) organic chemis- try reaction selectivity; 3) molar ratio formulations (chemotherapeutic/reagent/IgG); 4) specific sequential order of individual organic chemistry reaction schemes, and 5) extension of incubation periods for organic chem- istry reactions during the synthesis of gemcitabine (C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu], gemcitabine-(C5-methyl- carbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] and epirubicin-(C3-amide)- [anti-HER2/neu] collectively minimized side reactions resulting in the formation of extraneous side-products (Figure 1) [36,72]. Reaction condition variables are es- pecially important during the initial phases of synthesiz- ing gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate) and UV-photo-acti- vated gemcitabine-(C4-amide) reactive intermediates (Figure 2). [36] Generation of the UV-photoactivated gemcit- abine-(C4-amide) intermediate with succinimidyl 4,4-azipentanoate involves the succinimide ester group Figure 9. Relative cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency of gem- citabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] an d ge mci tab i ne- (C 5-me- thylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] as a function of immu- noglobulin-equivalent concentration. Legends: (4) gemcit- abine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] with a gemcitabine mo- lar-incorporation-index of 2.78:1 (182-hour incubation pe- riod); and (•) gemcitabine-(C5-methyl carbonate)-[anti-HER2/ neu] with a gemcitabine molar-incorporation-index of 1.1:1 (182-hour incubation period). Arrows indicate the approxi- mate concentration of gemcitabine-(C4-amide)[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methyl carbonate)[anti-HER2/neu] ne- cessary to achieve a 30% level of cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potentcy. Chemotherapeutic-resistant mammary adenocar- cinoma (SKBr-3) monolayer populations were incubated with either covalent gemcitabine immunochemotherapeu- tics formulated in triplicate at gradient concentrations. Cy- totoxic anti-neoplastic potency measured using a MTT cell vitality assay relative to matched negative reference con- trols. preferentially reacting with and forming a colvaent bond at the C4 cytosine-like amine group of gemcitabine. In organic solvent systems like DMSO and DMF suc- cinimidyl 4,4-azipentanoate may also react to a much lesser degree with nitrogen groups embended within five or six member ring structures but such complexes re- portedly dissociate redily with the addition of small amounts of ddH2O or aqeous buffer An organic solvent in the form of DMSO was applied in these investigations in order to preserve the integrity of the UV-photo- activated moiety of succinimidyl 4,4-azipentanoate dur- ing the extended incubation with gemcitabine. Alterna- tively, an aqueous buffer formulated between the pH range of 7 to 9 can effectively promote covalent amide bond formation when shorter incubation periods are in- dicated. Utilization of aqueous buffer with a pH of 6.5 and implementation of lower reaction condition tem- peratures (e.g. 4˚C) have reportedly been found to en- hance the reaction of succinimide ester group with dif Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 699 Figure 10. Relative cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency of co- valent gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] immuno- chemotherapeutic compared to anti-HER2/neu monoclonal immunoglobulin. Legends: (4) covalent gemcitabine-(C4- amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] immunochemotherapeutic; and (A) anti-HER2/neu monoclonal immunoglobulin. Chemothera- peutic-resistant mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) mon- olayer populations were incubated with gemcitabine-(C4- amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and anti-HER2/neu monoclonal immunoglobulin formulated in triplicate at at gradient concentrations. Cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency was meas- ured using a MTT cell vitality assay relative to matched negative reference controls . ferent primary amine subtypes (e.g. lysine ε-amine- vspeptide N-terminal amine). Conservative speculation suggests that one of the rea- sons for the differences in molar incorporation indexes (2.78-vs-1.1) for gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2 /neu] compared to gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)- [anti-HER2/neu] respectively was probably due to a combination of two critical reaction condition variables. Most notable in this regard was the application of the UV-photoactivated gemcitabine-(C4-amide) intermediate at a 10-to-1 molar ratio to anti-HER2/neu monoclonal immunoglobulin in concert with a lack of a require- ment [72] for 2-iminothiolane (2-IT) [36,71] or N-suc- cinimidyl-S-acetylthioacetate (SATA) [7] to pre-thiolate immunoglobulin fractions, IgG fragments, receptor li- gands or other biologically active peptide proteins (Figure 1). Higher molar incorporation indexes are possible to achieve with certain methodology modifications but the harsher synthesis conditions required for such purposes almost invariably are accompanied by substantial reduc- tions in final product yield of the covalent immuno- chemotherapeutic [6]. In addition to harsh reaction con- ditions, immunoglobulin antigen binding-avidity can be reduced as a function of excessive covalent chemothera- peutic incorporation into or within the Fab antigen- binding domain of immunoglobulin fractions. Despite this consideration, relatively higher molar incorpora- tion indexes were attained during the synthesis of ge m citabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] (2.78-to-1 or 278%) compared to gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)- [anti-HER2/neu] (1.1-to-1 or 110%), [36] epirubicin- (C13-imino )-[anti-HER2/neu] (0.4-to-1 or 40%), [71] epirubicin-(C3-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] (0.275 - to- 1 or 27.5%),[7,72] and epirubicin-(C3-amide)-[anti-EGFR] (0.407-to-1 or 40.7%) [7]. Conservative speculation sug- gests that one reason for the higher molar incorporation index observed for covalent gemcitabine-(C4-amide)- [anti-HER2/neu] immunochemotherapeutic was due to the implementation of a synthesis scheme that involved a distinctly different organic chemistry reactions and that even higher molar incorporation indexes along with greater levels of cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency are possible (Figure 1). A somewhat unique property of the UV-photoacti- vated gemcitabine-(C4-amide) intermediate generated utilizing succinimidyl 4,4-azipentanoate in Phase-I of the synthetic organic chemistry reaction scheme is that it does not contain a sulfhydryl-reactive maleimide group (Figure 1). The lack of a sulfhydryl-reactive maleimide moiety within the structure of the UV-photoactivated gemcitabine-(C4-amide) intermediate therefore allows it to be applied to synthesize covalent immunochemo- therapeutics without a requirement to pre-thiolateamine groups associated with lysine residues in the amino acid sequence of anti-HER2/neu monoclonal immunoglobulin. Because of this feature it is possible to initiate Phase-II of the synthetic organic chemistry reaction scheme for gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] without the introduction of reduced sulfhydryl groups into the amino acid sequence of immunoglobulin (IgG) fractions, IgG fragments [F(ab’)2 or Fab’], receptor ligands, receptor ligand fragments or other biologically relevant pro- tein fractions (Figure 1). In contrast, the gemcitabine- (C5-methylcarbamate) reactive intermediate synthesized with N-[p-maleimidophenyl]-isocyanate does contain a sulfhydryl-reactive maleimide group (Figure 2) [36]. Similarly, anthracycline reactive intermediates applied to synthesize many if not most anthracycline-immuno- chemotherapeutics also employ a sulfhydryl-reactive malei- mide group to facilitate the creation of a covalent bond with immunoglobulin or other biologically active protein fractions [7,71,72]. Such synthetic organic chemistry reactions schemes are dependent upon the utilization of heterobifunctional reactants similar to succinimidyl-4- (N-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane-1-carboxylate (SMCC), [7,80-82] N-ε-maleimidocaproic acid hydrazide (EMCH), [9,10,71] or N-[p-maleimidophenyl]- isocyanate (PMPI) [36,53-55]. In the application of these covalent bond- forming reagents, disruption of disulfide bond structures Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 700 or prethiolation of immunoglobulin or other biological protein fractions is almost invariably required due to the relatively low number of non-sterically hindered sulfhy- dryl groups available within the amino acid sequence of most biologically active proteins in the form of reduced cysteine amino acid residues (e.g. R-SH). Increasing the number of available reduced sulf- hydryl groups can be achieved by the application of 1,4dithiothreitol which reduces intramolecular cystinecystine [26-28] and similar disulfide structures [83] (DTT: R-CH2-S-S-CH2-R—2 R-CH2-SH). The actual synthetic introduction of “new” or additional reduced sulfhydryl groups at the ε-amine of lysine amino acid residues is possible utilizing organic chemistry reaction schemes that employ 2-iminothio- lane (2-IT), [2,6, 36,71,84] mercaptosuccinimide, [85] or N-succinimidylS-acetylthioacetate (SATA) [7,84,86]. Al- ternatively, carboxyl groups on molecules like heparin and hyaluronic acid (HA) can be thiolated with 3,3’di- thiobis (propanoic)hydrazide (DPTH) [83,87] or divinyl- sulfone (DVS), [88, 89] in addition to the hydroxyl groups of molecules with a cholesterol-like core [90]. In the application of DTPH the integral disulfide bond is subsequently reduced with DTT reagent [83,87]. Covalently bonding gemcitabine or other chemothera- peutic agents to biological protein fractions like immu- noglobulin without a requirement to convert existing cystine-cystine disulfide bonds to their reduced form (R1-S-S-R2—R1-SH and R2-SH) or the synthetic intro- duction of reduced sulfhydryl groups provides several disctinct advantages. Specifically, such synthetic organic chemistry reaction schemes entail the implementation of fewer synthetic chemistry reactions, require fewer critical reagents, and maximize final “end-product” yield due in part to at least one less column chromatography separa- tion procedure. The brief duration of the synthetic or- ganic chemistry reaction scheme for gemcitabine- (C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] utilizing succinimidyl 4,4- azipentanoate is realized because of the relatively rapid time course for the Phase-I, but especially the Phase-II organic chemistry reaction. The synthetic organic chem- istry reaction scheme has also been designed so that ad- justment of buffer pH to different levels during the pro- cedure is not necessary in contrast to other techniques [91]. Perhaps one of the most important features of the synthesis methodology is a lack of a requirement for cystinecystine disulfide bond reduction or pre-thiolation that in turn allows by design the application of synthetic chemistry reactions that are highly efficient under rela- tively mild conditions thereby possing a lower risk of protein fragmentation or polymerization (e.g. IgG-IgG) through premature intra-molecular disulfide bond forma- tion [2]. Realized benefits therefore include greater re- tained biological activity (e.g. antigen binding-avidity) and increased total final yield of a function immuno chemotherapeutic end-product. Lastly, lack of a require- ment to either convert existing cystine-cystine disulfide bonds to their reduced form or the introduction of re- duced sulfhydryl groups into immunoglobulin fractions reduces restrictions and limitations on the magnitude of the molar-incorporation-index that can be attained. In contrast, the chemotherapeutic incorporation index for covalent immunochemotherapeutics synthesized utilizing SMCC, [7,80-82] EMCH [9,10,71] or PMPI [36,53-55] is only equivalent to or lower than the extent of pre- thiolation at ε-amine groups associated with the finite number of lysine residues within the amino acid se- quence of protein fractions. In prethiolation dependent synthesis schemes higher epirubicin molar-incorporation- indexes are possible with modifications in methodology but requires the use of harsher synthesis conditions that are frequently accompanied by substantial reductions in total yield of covalent immunochemotherapeutic, [6] and declines in antigen-immubnoglobulin bindingavidity (e.g. cell-ELISA parameters). Presumably the 7.6 fold higher potency of gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] com- pared to gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/ neu] at the cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency level of ap- proximately 30% can be attributed to a combination of a greater degree retained biological activity for anti- HER2/neu (cell-ELISA) and a higher gemcitibin mo- lar-incorporation-index of 2.78-to-1 for gemcitabine-(C4- amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] in contrast to 1.1-to-1 for gem- citabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] (Figure 9). Both of these properties are anticipated to be attribut- able to the application of gentler reaction conditions in part due to a lack of a requirement for anti-HER2/neu prethiolation during Phase-II synthesis reaction sheme for gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti- HER2/neu]. Implementation of succinimidyl 4,4-azipentanoate in the synthesis scheme for gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti- HER1/neu] offers desirable attributes other than a lack of a requirement for pre-thiolation of immu- noglobulin or similar molecular platforms that possess biological activ- ity that affords properties of selective “targeted” delivery. In contrast to SMCC, [7,80-82] EMCH [9,10,71] or PMPI [36,53-55] the synthesis of gemcitabine-(C4-am- ide)-[anti-HER2/neu] utilizing succinimidyl 4,4-azipen- tanoate has the added benefit of not introducing extrane- ous five and six carbon or carbon/nitrogen ring structures into the final covalent immunochemotherapeutic end- product (Figures 1 and 2). Elimination of extraneous ring structures decreases the probability of inducing in-vivo humoral immune response when administered by IV injection that can ultimately result in the formation of neutralizing antibody titers and an increased risk of post-treatment immune hypersensitivity reactions. In addition, the Phase-I synthetic organic chemistry reaction scheme can be performed in either aqueous buffer, or Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 701 organic solvent systems supplemented with triethylamine [N(CH2CH3)3] or similar proton acceptor molecules at low concentrations. In stock solutions of reaction mix- tures formulated in aqueous buffers a significant amount of hydrolytic degradation of succinimidyl 4,4-azipen- tanoate is expected to occur to varying degrees. Alterna- tively, if stock solutions and reaction mixtures of gem- citabine and succinimidyl 4,4-azipentanoate are instead formulated in an anhydrous organic solvent like DMSO in combination with a proton acceptor molecule then the resulting UV-photoactivated gemcitabine-(C4-amide) intermediate is stable at 4˚C or −20˚C for a period of time when adequately protected from UV-light exposure. Such chemical properties of succinimidyl 4,4-azipen- tanoate allow for the convenient option of “presynthe- sizing” and preserved storage of the UV-photoactivated gemcitabine-(C4-amide) intermediate for an extend pe- riod of time for the future production of covalent gem- citabine-immunochemotherapeutics [72]. The synthetic organic chemistry reaction scheme described also offers another added level of convenience because it represents a template model that can be adapted and modified to facilitate the covalent bonding of an array of different chemotherapeutic agents to a wide range of molecular platforms that can facilitate selective “targeted” pharma- ceutical delivery. Cell-Binding Profiles-Increases in standardized im- munoglobulin-equivalent concentrations of gemcitabine- (C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methyl- carbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] correlated with elevations in total immunoglobulin membrane binding profiles in populations of human mammary adenocarcinoma de- tected by cell-ELISA (Figure 4). The lower standardized immunoglobulin-equivalent concentration range for gem- citabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] compared to gem- citabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] implies that the former covalent gemcitabine immunochemo- therapeutic may have a higher level of retained anti- HER2/neu binding-avidity. The most probably explana- tion for this difference can be attributed to the imple- mentation of milder organic chemical reaction conditions and a lack of a requirement for pre-thiolate of anti- HER2/neu fractions. Previous investigations have simi- larly noted that modest alterations in synthetic chemistry and elevations in the chemotherapeutic molar incorpora- tion index can profoundly influence immunoglobulin binding properties [29]. Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity/Potency-Covalent gemcitabine conjugates have been synthesized that exert greater cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency than gemcit- abine chemotherapeutic alone, but these preparations have been produced in the form of gemcitabine- (oxyether phopholipid) [40,60] or dual gemcitabine/ doxorubicin-HPMA (N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacryla- mide polymer). [21] In a very limited number of investi- gations, the cytotoxic anti-neoplastic activity for majori- ties of these covalently bonded gemcitabine preparations were reported against human mammary carcinoma (MCF7/WT-2’), [60] human mammary adenocarcinoma (BG-1), [60] promyelocytic leukemia, [40,60] a T-4 lym- phoblastoid clone, [60] glioblastoma, [40,60] cervical epithelioid carcinoma, [60] colon adenocarcinoma, [60] pancreatic adenocarcinoma, [60] pulmonary adenocarci- noma, [60] oral squamous cell carcinoma, [60] and prostatic carcinoma [21]. Increases in the molar chemotherapeutic-equivalent concentrations of gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/ neu] created corresponding elevations in the cytotoxic anti- neoplastic potency and declines in the residual survival of chemotherapeutic-resistant mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) populations (Figures 5-7). Neither gemcit- abine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2 /neu ] or gemcitabine-(C5-me- thylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] exerted substantially greater selective “targeted” anti-neoplastic potency against chemotherapeutic-resistant mammary adenocar- cinoma (SKBr-3) that was greater than gemcitabine alone when formulated at molar chemotherapeutic-equivalent concentrations between 10−10 M to 10−6 M and an incu- bation period of 182-hours (Figures 5-7). Such findings are in contrast to covalent epirubicin-[anti-HER2/neu] immunochemotherapeutics that possess equivalent or greater cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency levels than epirubicin alone [7,71,72]. Despite this difference, the selectively “targeted” cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency of covalent gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbama te)-[anti-HER2/neu] immunochemotherapeutics at 182-hours was almost identicial to levels exerted by gemcitabine after a 72-hour incubation period [92]. In the interpretation of the cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency of gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] it should be emphasized that such comparisons were made at gemcitabine-equivalent concentrations. Alternatively, if comparisons of cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency for the two covalent gemcitabine-immunochemotherapeutics are made as a function of immunoglobulin-equivalent con- centrations (e.g. anti-HER2/neu content) and gemcitabine molar-incorporation-indexes then it is possible to detect a relatively greater level of potency for gemcitabine- (C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] compared to gemcitabine (C5- methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] (Figure 9). Given this perspective, gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti- HER2/neu] for example each exerted a 30% level of cytotoxic anti-neo- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 702 plastic potency at immunoglobulin-equivalent concentra- tions of 6.9 × 10–8 M and 9.1 × 10–9 M respectively (Figure 9). Based on these calculations, gemcitabine- (C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] was approximately 7.6-fold more potent than gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)- [anti-HER2/neu] when cytotoxic anti-neoplastic activity was standardized as a function of immunoglobulin- equivalent concentration. Presumably this difference in cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency was due to a combina- tion of a greater degree of retained biological activity for anti-HER2/neu (cell-ELISA) and a higher gemcitibin molar-incorporation-index (2.78-to-1) for gemcitabine- (C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] compared to gemcitabine- (C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu]. Both of these properties are likely attributable to the application of gentler reaction conditions again due in part to a lack of a requirement for anti-HER2/neu prethiolation during Phase-II of the organic chemistryreaction scheme applied in the synthesis of gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/ neu]. In contrast to most covalent anthracycline immuno- chemotherapeutics described to date, a longer 182-hour incubation period was applied to access the cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency of gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti- HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti- HER2/neu] in order to optimally evaluate their cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency (Figure 5) [36,71,72]. Longer incubation periods have also been applied to evaluate other synthetic gemcitabine-ligand preparations in order to more accurately access their ex-vivo cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency [21,36,40,59]. Several explana- tions may account for the requirement to use longer in- cubation periods for the ex-vivo evalution of gemcitabine compared to anthracycline-immunochemotherapeutics or anthracycline covalent bound to other molecular plat- forms with properties that afford selective “targeted” delivery (e.g. receptor ligands). Since the covalent im- munochemotherapeutics gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti- HER2/neu], gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/ neu] [36] and several epirubicin-[anti-HER2/ neu] im- munochemotherapeutics [7,71,72] all selectively “target” chemotherapeutic delivery at the same HER2/ neu re- ceptor site highly over-expressed on the external surface membrane of mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3), it is possible that differences in their cytotoxic anti- neoplas- tic activity may be attributable to, 1) differences in the vulnerability of covalent bond structures created during the synthesis of gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2 / neu] to enzyme-mediated degradation or simple hydrolysis within the acidic endosome/lysosome microenvironment; 2) variations in the expression profile for different en- zyme fractions necessary for biochemically liberating gemcitabine versus epirubicin from covalent immuno- chemotherapeutics; 3) variation in the acidic characteris- tics associated with the endosome/lysosome microenvi- ronment necessary for liberating gemcitabine versus epirubicin from covalent immunochemotherapeutics; 4) greater capacity of the anthracycline moiety within intact covalent epirubicin immunochemotherapeutics to exert one or more of the multiple mechanisms-of-action rec- ognized for this class of chemotherapeutic agent; 5) vul- nerability of the gemcitabine moiety in covalent gemcit- abine immunochemotherapeutics to inactivation by deamination. The fact that cytotoxic anti-neoplastic po- tency profiles for gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/ neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/ neu] at the end of a 182-hour incubation period were very similar to those for gemcitabine after a 72-hour in- cubation period implies that cytotoxic anti-neoplastic activity of the gemcitabine immunochemotherapeutics is possibly delayed due to a slow release of the chemo- therapeutic moiety that is apparently longer compared to the rate of anthracycline-release from covalent epirubi- cin-immunochemotherapeutics [7,71,72]. One important implication of this possible explanation is that a delayed and prolonged release or liberation of gemcitabine from covalent gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] could represent a desirable property that can be em- ployed as a molecular strategy to evoke “super-loading” that in turn can facilitate extensive and sustained chemo- therapeutic deposition and release within populations of neoplastic cells. Collective interpretation of results from SDS-PAGE/ immunodection/chemiluminscent autoradiography, cell- ELISA and cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency analyses illustrates how gemcitabine can be covalently bound to a large molecular weight “carrier” (protein) to facilitate selective “targeted” chemotherapeutic delivery and cyto- toxic anti-neoplastic potency. The positive findings di- rectly address one of the major objectives that originally motivated the molecular design and synthesis of gem- citabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu]. Additionally, there was a perceived need for the molecular design of a syn- thesis scheme that was composed of a sequential series of organic chemistry reactions that could facilitate relatively rapid production of gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/ neu] using mild conditions that affored minimal degrada- tive low molecular weight fragmentation or large mo- lecular weight polymerization (e.g. IgG-IgG). Recent investigations describing the methodology employed for the synthesis of epirubicin-(C5-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] through the application of a UV-photoactivated epirubi- cin intermediate revealed that there was a high degree of probability that a similar organic chemistry regimen Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 703 could be adapted as a model with minor modifications for the relatively rapid synthesis of a covalent gemcit- abine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] immunochemothera- peutic [72]. In this context, a set of organic chemistry reactions were implemented to synthesize gemcitabine- (C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] that had not previously been described for the production of a gemcitabine-immuno- chemotherapeutic or covalent gemcitabine-ligand prepa- ration. The organic chemistry synthesis reactions utilized for the production of gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/ neu] also possesses practical utility because it can serve as a model or template for the molecular design and pro- duction of other covalent immunochemotherapeutics. Conceptually there are at least five analytical vari- ables that could have alternatively been modified to achieve substantially higher total levels of cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency for gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti- HER2/neu]. First, incubation times with chemothera- peutic-resistant mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) could have been lengthened to a period > 182-hours [36] there-by allowing greater opportunity for larger amounts of gemcitabine to be internalized by receptor-mediated endocytosis and subsequently liberated intracellularly from gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] or gem- citabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu]. Sup- port for this consideration in based on the observation that there was a simple dose effect for gemcitabine-(C4- amide)-[anti-HER2/neu], and because mammary adeno- carcinoma (SKBr-3) survivability was very similar when challenged with gemcibatine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti- HER2/neu] (182-hours) compared to gemcitabine (72- hours), but increased dramatically for gemcitabine when the incubation period was extended to 182-hours (Fig- ures 5-7).[36] Conservative speculation suggests that incubation of chemotherapeutic-resistant mammary ade- nocarcinoma (SKBr-3) with gemcitabine-(C4-amide)- [anti-HER2/neu] or gemcibatine-(C5-methylcarbamate)- [anti-HER2/neu] for periods greater than 182-hours would have resulted in even higher levels of cytotoxic anti-neoplatic potency since there was no indication that the level of cytotoxic activity achieved against chemo- therapeutic-resistant mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) had reached a “plateau” or maximum level (Figures 5-7). Second, cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency of gemci- batine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5- methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] could have alterna- tively been assessed against a human neoplastic cell type that was not chemotherapeutic-resistant similar to cancer cell types utilized to evaluate majority of the covalent biochemotherapeutics reported in the literature to date. Rare exceptions to this consideration have been the ap- plication of chemotherapeutic-resistant metastatic mela- noma M21 (covalent daunorubicin immunochemothera- peutics synthesized using anti-chondroitin sulfate pro- teoglycan 9.2.27 surface marker), [29,32,93] chemo- therapeutic-resistant mammary carcinoma MCF-7AdrR (covalent anthracycline-ligand chemotherapeutics syn- thesized utilizing epidermal growth factor/EGF or an EGF fragment); [94] and chemotherapeutic-resistant mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) populations (epiru- bicin-anti-HER2/neu, epirubicin-anti-EGFR, gemcitabine- HER2/neu) [7, 36,71,72]. Somewhat analogous to the concept of non-chemo- therapeutic resistant cancer cell types, the cytotoxic anti- neoplatic potency of gemcibatine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/ neu] and gemcitabine-(C5methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/ neu] could also have alternatively been measured against an entirely different neoplastic cell type such as pancre- atic carcinoma, [95] small-cell lung carcinoma, [96] neuroblastoma, [97] or leukemia/lymphoid [60,98] popu- lations due to their relatively higher gemcitabine sensi- tivity. Similarly, human promyelocytic leukemia, [40,60] T-4 lymphoblastoid clones, [60] glioblastoma, [40,60] cervical epitheliod carcinoma, [60] colon adenocarci- noma, [60] pancreatic adenocarcinoma, [60] pulmonary adenocarcinoma, [60] oral squamous cell carcinoma, [60] and prostatic carcinoma [21] have all been found to be sensitive to gemcitabine and gemcitabine-(oxyether phopholipid) covalently bonded chemotherapeutics. Within this array of neoplastic cell types, however, hu- man mammary carcinoma (MCF-7/WT-2’) [60] and mammary adenocarcinoma (BG-1) [60] are known to be relatively more resistant to gemcitabine and gemcit- abine-(oxyether phopholipid) chemotherapeutic conju- gate. Presumably this pattern of diminished gemcitabine sensitivity is directly relevant to the cytotoxic anti-neo- platic potency detected for gemcibatine-(C4-amide)- [anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate) -[anti-HER2/neu] compared to gemcitabine in chemo- therapeutic-resistant mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) populations (Figures 5-7). Third, cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency of gemci- batine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5- methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] could have been evaluated at higher gemcitabine-equivalent concentra- tions. Since gemcitabine in contrast to the anthracyclines has rarely been synthetically incorporated into (cova- lently bonded to) selective “targeted” delivery platforms, [21,36,40,57-60] it is uncertain if this chemotherapeutic can be utilized to consistently create covalent gemcit- abine immunochemotherapeutics that posses signifi- cantly higher levels of cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency than gemcitabine alone (Figures 5-7) [36]. Despite this consideration, the paramount objective that moti- vates the molecular design and synthesis of covalent gemcit- abine immunochemotherapeutics is the opportu- nity to Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 704 create a new anti-cancer modality that affords reduced exposure of healthy tissues and organ systems to the cy- totoxic anti-neoplastic properties of chemothera- peutics. By design, such attributes are facilitated by selectively “targeted” delivery of chemotherapeutic moieties in a manner that produces cytotoxic anti-neoplastic properties that are largely restricted to malignant lesions. Given this perspective and applying basic pharmacology principals, the variable of potency can simply be addressed through adjustment of concentration (dose administered) within the limitations of induced side effects and sequelae. Fourth, anti-neoplastic potency of gemcitabine-(C4- amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcar- bamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] would likely have been sub- stantially greater if cellular proliferation had been as- sessed with either [3H]-thymidine, or an ATP-based as- say method because of their reportedly >10-fold greater sensitivity in detecting early cell injury compared to MTT vitality stain based assay methods [99,100]. De- spite this consideration, MTT vitality stain based assays continue to be extensively applied for the routine as- sessment of true cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency of chemotherapeutics covalently incorporated synthetically into molecular platforms that provide properties of selec- tive “targeted” delivery.[7,40,58,60,101-106] One of the most significant advantages of MTT vitality stain based assays and methods that apply similar reagents is that the ability to measure lethal cytotoxic anti-anti-neoplastic activity is generally considered to be superior to mearly the detection of early-stage and potentially transient cel- lular injury that could ultimately be reversible. Fifth, cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency of gemci- batine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5- methylcarbamate)-[anti-HER2/neu] immunochemothera- peutic could have been delineated in-vivo against human neoplastic xenographs in animal hosts as a model for human cancer. Effectiveness and potency of many if not most covalent immunochemotherapeutics against neo- plastic cell populations (that genuinely do possess prop- erties of selectively “targeted” chemotherapeutic delivery) is frequently higher when evaluated in-vivo compared to results acquired ex-vivo in tissue culture models utilizing the same identical cancer cell type [107-109]. Enhanced levels of covalent immunochemotherapeutic potency measured in-vivo is presumably attributable in part to induced responses by the innate immune system that in- cludes antibody-de-pendent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC) phenomenon in concert with complementedmediated cytolysis initiated or stimulated by the formation of anti- gen-immunoglobulin complexes on the exterior surface membrane of “targeted” neoplastic cell types. During ADCC events immune cell types actively involved in this response release cytotoxic components that are known to additively and synergistically enhance the cytotoxic anti-neoplastic activity of conventional chemotherapeutic agents [110]. The contributions of ADCC and comple- ment-mediated cytolysis to the in-vivo cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency of covalent immunochemothera- peutics would be further enhanced by the additive and synergistic levels of anti-neoplastic potency produced by anti-trophic receptor monoclonal immunoglobulin when applied in dual combination with conventional chemo- therapeutic agents [48,49,83,89,111-118]. Additive or synergistic interactions of this type have been detected between anti-HER2/neu when applied simultaneously in combination with cyclophosphamide [49,111], docetaxel [111], doxorubicin [49,111], etoposide [111], meth- otrexate [111], paclitaxel [49,111], or vinblastine [111]. Sixth, several modifications could have been made in the synthesis strategy for gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti- HER2/neu] and gemcitabine-(C5-methylcarbamate)-[anti- HER2/neu] in order to increase the gemcitabine mo- lar-incorporation-index. Examples in this regard include the application of gemcitabine and the covalent bond forming reagents at higher molar concentrations, imple- mentation of smaller reaction volumes during synthesis procedures, increasing the duration of Phase I and/or Phase II synthesis schemes, and possibly altering the relative gemcitabine-to-covalent bond forming reagent- to-immunoglobulin molar ratios in a manner that forces the organic chemistry reactions in a direction that in- creases final product yield. Unfortunately, such modifi- cations usually also require or impose harsher reaction conditions that necessitate an acceptance for a higher risk of reduced biological activity (e.g. decreased antigen bind- ing avidity) and substantial declines in final/total product yield [6, 108]. Aside from overly harsh synthesis condi- tions, excessively high molar incorporation indexes for any chemotherapeutic agent can reduce the biological integrity of immunoglobulin fractions when the number of pharmaceutical groups introduced into the Fab’ anti- genbinding region becomes excessive. Such modifica- tions can result in only modest declines in immunoreac- tivity (e.g. 86% for a 73:1 ratio) but disproportionately large declines in cytotoxic anti-neoplastic activity in ad- dition to reductions in potency that can decrease to levels substantially lower than those found with non-conjugated “free” chemotherapeutic (e.g. anthracyclines) [108]. The biological integrity of the immunoglobulin com- ponent of covalent immunochemotherapeutics is criti- cally important. It not only serves as a means of facili- tating selectively “targeting” chemotherapeutic delivery, but it also initiates or induces internalization of covalent immunochemotherapeutics by mechanism of receptor- mediated endocytosis assuming an appropriate mem- brane-associated antigen has been selected as a “target” Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 705 (e.g. many carcinoma and adenocarcinoma cell types highly over-express HER2/neu and/or EGFR) [119]. Al- though specific data for HER2/neu and EGFR expression by mammary adenocarcinoma (SKBr-3) is limited, [7] other neoplastic cell types like metastatic multiple mye- loma are known to internalize and metabolize approxi- mately 8 × 106 molecules of anti-CD74 monoclonal an- tibody per day [120]. Immunoglobulin-induced receptor- mediated endocytosis at membrane HER2/neu complexes can ultimately lead to increases in the intracellular con- centration of selectively “targeted”/delivered chemo- therapeutic that approach and exceed levels 8.5 [121] to >100 × fold greater [122] than those that can ever possi- bly be achieved by simple passive chemotherapeutic dif- fusion from out of the intravascular compartment. The application of succinimidyl 4,4-azipentanoate in contrast to succinimidyl-4-(N-maleimidomethyl)-cyc- lohexane-1-carboxylate (SMCC), [7,80-82] N-ε-male- imidocaproic acid hydrazide (EMCH), [8-10,51,52,71] or N-[p-maleimidophenyl]-isocyanate (PMPI) [36,53-55] can facilitate greater flexibility in synthesis methods de- signed to increase the chemotherapeutic molar-incorpo- ration-index during the creation of covalent immuno- chemotherapeutics without having to use harsher reaction conditions. The major risk of compromising the biologi- cal integrity (antigen binding avidity) of gemcitabine- (C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] synthesized with a UV-photo- activated gemcitabine intermediate therefore is almost entirely associated with methods devised to introduce an excessive amount of pharmaceutical (chemotherapeutic) into immunoglobulin fractions including regions of the amino acid sequence that are directly responsible for providing properties of selective “targeted” delivery (e.g. Fab antigen bindings regions of immunoglobulin or re- ceptor binding region of ligands). Despite the general validity of the inverse relationship between chemothera- peutic molar-incorporation-index and retained biological activity (e.g. anti-HER2/neu mediated selective “tar- geted” delivery) and the greater potency of covalent im- munochemotherapeutics with high chemotherapeutic molar incorporation indexes, it should be emphasized that mathematically the expression density for external membrane-associated “targets” appears to be one of, if not the most critically important variable that influences the cytotoxic anti-neoplastic potency of covalent immu- nochemotherapeutics or ligand-chemotherapeutic prepa- ration. In this regard, it is important that external mem- brane-associated sites be chosen that are known to func- tionally undergo phenomenon analogous to receptor- mediated-endocytosis in order to avoid only “coating” of the external surface membrane of “targeted” cancer cell populations. Such a prerequisite is relevant assuming that the chemotherapeutic agent applied has a mechanism- of-action that is dependent upon their ability to modify the function of molecular entities within the cytosol or nucleus in order to exert a biological effect. Such a re- quirement would not be a prerequisite for anti-cancer agents that instead alter or disrupt the physical integrity of cancer cell membranes or the function of complexes that are an integral component of membrane structures. 5. Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge Mr. Tom Thomp- son in the Office of Agriculture Communications for assistance with the photographic illustration. REFERENCES [1] T. Kaneko, D. Willner, J. O. Knipe, G. R. Braslawsky, R. S. Greenfield and D. M. Vyas, “New Hydrazone Deriva- tives of Adriamycin and Their Immunoconjugates: A Cor- relation between Acid-Stability and Cytotoxicity,” Bio- conjugate Chemistry, Vol. 2, No. 3, 1991, pp. 133-141. doi:10.1021/bc00009a001 [2] G. Di Stefano, M. Lanza, F. Kratz, L. Merina and L. Fiume, “A Novel Method for Coupling Doxorubicin to Lactosaminated Human Albumin by an Acid Sensitive Hydrazone Bond: Synthesis, Characterization. And Pre- liminary Biological Properties of the Conjugate,” Euro- pean Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Vol. 23, No. 4-6, 2004, pp. 393-397. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2004.09.005 [3] F. Kratz, A. Warnecke, K. Scheuermann, C. Stockmar, J. Schwab, P. Lazar, P. Drückes, N. Esser, J. Drevs, D. Rognan, C. Bissantz, C. Hinderling, G. Folkers, I. Ficht- ner and C. Unger, “Probing the Cysteine-34 Position of Endogenous Serum Albumin with Thiol-Binding, Dox- orubicin Derivatives. Improved Efficacy of an Acid-Sen- sitive Doxorubicin Derivative with Specific Albumin- Binding Properties Compared to That of the Parent Com- pound,” Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, Vol. 45, No. 25, 2002, pp. 5523-5533. doi:10.1021/jm020276c [4] C. Unger, B. Häring, M. Medinger, J. Drevs, S. Steinbild, F. Kratz and K. Mross, “Phase I and Pharmacokinetic Study of the (6-Maleimidocaproyl) Hydrazone Derivative of Doxorubicin,” Clinical Cancer Research, Vol. 13, No. 16, 2007, pp. 4858-4866. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2776 [5] C. Mazuel, J. Grove, G. Gerin and K. P. Keenan, “HPLC- MS/MS Determination of a Peptide Conjugate Prodrug of Doxorubicin, and Its Active Metabolites, Leucine-Dox- orubicin and Doxorubicin, in Dog and Rat Plasma,” Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, Vol. 33, No. 5, 2003, pp. 1093-1102. doi:10.1016/S0731-7085(03)00434-5 [6] R. S. Greenfield, T. Kaneko, A. Daues, M. A. Edson, K. A. Fitzgerald, L. J. Olech, J. A. Grattan, G. L. Spitalny and G. R. Braslawsky, “Evaluation In-Vitro of Adriamy- cin Immunoconjugates Synthesized Using an Acid-Sen- sitive Hydrazone Linker,” Cancer Research, Vol. 50, No. 20, 1990, pp. 6600-6607. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 706 [7] C. P. Coyne, M. Ross, J. Bailey and T. Jones, “Dual Po- tency Anti-HER2/neu and Anti-EGFR Anthracycline- Immunoconjugates in Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mam- mary Carcinoma Combined with Cyclosporin-A and Verapamil P-Glycoprotein Inhibition,” Journal of Drug Targeting, Vol. 17, No. 6, 2009, pp. 474-489. doi:10.1080/10611860903012802 [8] A. Lau, G. Berube, C. H. J. Ford and M. Gallant, “Novel Doxorubicin-Monoclonal Anti-Carcinoembryonic Anti- gen Antibody Immunoconjugate Activity In-Vivo” Bio- organic and Medicinal Chemistry, Vol. 3, No. 10, 1995, pp. 1305-1312. doi:10.1016/0968-0896(95)00126-2 [9] M. Kruger, U. Beyer, P. Schumacher, C. Unger, H. Zahn and F. Kratz, “Synthesis and Stability of Four Maleimide Derivatives of the Anti-Cancer Drug Doxorubicin for the Preparation of Chemoimmunoconjugates,” Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin, Vol. 45, No. 2, 1997 pp. 399- 401. doi:10.1248/cpb.45.399 [10] D. Y. Furgeson, M. R. Dreher and A. Chilkoti, “Struc- tural Optimization of a ‘Smart’ Doxorubicin-Polypeptide Conjugate for Thermally Targeted Delivery to Solid Tu- mors,” Journal of Controlled Release, Vol 110, No. 2, 2006, pp. 362-369. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.10.006 [11] J. F. Liang and V. C. Yang, “Synthesis of Doxorubi- cin-Peptide Conjugate with Multidrug Resistant Tumor Cell Killing Activity,” Bioorganic and Medicinal Chem- istry Letters, Vol. 15, No. 22, 2005, pp. 5071-5075. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.07.087 [12] M. Sirova, J. Strohalm, V. Subr, D. Plocova, P. Ros- smann, T. Mrkvan, K. Ulbrich and B. Rihova, “Treatment with HPMA Copolymer-Based Doxorubicin Conjugate Containing Human Immunoglobulin Induces Long-Last- ing Systemic Anti-Tumor Immunity in Mice,” Cancer Immunol Immunother, Vol. 56, No. 1, 2007, pp. 35-47. doi:10.1007/s00262-006-0168-0 [13] B. K. Wong, D. Defeo-Jones, R. E. Jones, V. M. Garsky, D. M. Feng, A. Oliff, M. Chiba, J. D. Ellis and J. H. Lin, “PSA-Specific and Non-PSA-Specific Conversion of a PSA-Targeted Peptide Conjugate of Doxorubicin to Its Active Metabolite,” Drug Metabolism and Disposition, Vol. 29, No. 3, 2001, pp. 313-318. [14] G. L. Bidwell, A. N. Davis, I. Fokt, W. Priebe and D. Raucher, “A Thermally Targeted Elastin-Like Polypep- tide-Doxorubicin Conjugate Overcomes Drug Resistance,” Investigational New Drugs, Vol. 25, No. 4, 2007, pp. 313-326. doi:10.1007/s10637-007-9053-8 [15] K. A. Ajaj, R. Graeser, I. Fichtner and F. Kratz, “In-Vitro and In-Vivo Study of an Albumin-Binding Prodrug of Doxorubicin That Is Cleaved by Cathepsin B,” Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology, Vol. 64, No. 2, 2009, pp. 413-418. doi:10.1007/s00280-009-0942-8 [16] C. Ryppa, H. Mann-Steinberg, I. Fichtner, H. Weber, R. Satchi-Fainaro, M. L. Biniossek and F. Kratz, “In-Vitro and In-Vivo Evaluation of Doxorubicin Conjugates with the Divalent Peptide E-[c(RGDfK)2] That Targets In- tegrin aVb3,” Bioconjugate Chemistry, Vol. 19, No. 7, 2008 pp. 1414-1422. doi:10.1021/bc800117r [17] Y. F. Huang, D. Shangguan, H. Liu, J. A. Phillips, X. Zhang, Y. Chen and W. Tan, “Molecular Assembly of an Aptamer-Drug Conjugate for Targeted Drug Delivery to Tumor Cells,” A European Journal of Chemical Biology, Vol. 10, No. 5, 2009, pp. 862-868. doi:10.1002/cbic.200800805 [18] Y. Ren, D. Wei and X. Zhan, “Inhibition of P-Glycopro- tein and Increasing of Drug-Sensitivity of a Human Car- cinoma Cell Line (KB-A-1) by an Anti-Sense Oligode- oxynucleotide-Doxorubicin Conjugate In-Vitro,” Biotech- nology and Applied Biochemistry, Vol. 41, No. 2, 2005, pp. 137-143. doi:10.1042/BA20040058 [19] Y. Ren, X. Zhan, D. Wei and J. Liu, “In-Vitro Reversal MDR of Human Carcinoma Cell Line by an Antisense Oligodeoxynucleotide-Doxorubicin Conjugate,” Biomedi- cine & Pharmacotherapy, Vol. 58. No. 9, 2004, pp. 520- 526. [20] L. Kovar, T. Etrych, M. Kabesova, V. Subr, D. Vetvicka, O. Hovorka, J. Strohalm, J. Sklenar, P. Chytil, K. Ulbrich and B. Rihova, “Doxorubicin Attached to HPMA Co- polymer via Amide Bond Modifies the Glycosylation Pattern of EL4 Cells,” Tumor Biology, Vol. 31. No. 4, 2010, pp 233-242. doi:10.1007/s13277-010-0019-7 [21] T. Lammers, V. Subr, K. Ulbrich, P. Peschke, P. E. Huber, W. E. Hennink and G. Storm, “Simultaneous Delivery of Doxorubicin and Gemcitabine to Tumors in Vivo Using Prototypic Polymeric Drug Carriers,” Biomaterials, Vol. 30, No. 20, 2009, pp. 3466-3475. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.02.040 [22] H. Krakovicova, T. Ethch and K. Ulbrich, “HPMA-Based Polymerconjugates with Drug Combinations,” European Journal of Pharmacology, Vol. 37. No. 3-4, 2009, pp. 4050-4412. [23] N. Cao and S. S. Feng, “Doxorubicin Conjugated to D-Alpha-Tocopheryl Polyethylene Glycol 1000 Succinate (TPGS): Conjugation Chemistry, Characterization, In- Vitro and In-Vivo Evaluation,” Biomaterials, Vol. 29, No. 28, 2008, pp. 3856-3865. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.05.016 [24] P. C. Rodrigues, U. Beyer, P. Schumacher, T. Roth, H. H. Fiebig, C. Unger, L. Messori, P. Orioli, D. H. Paper, R. Mülhaupt and F. Kratz, “Acid-Sensitive Polyethylene Glycol Conjugates of Doxorubicin: Preparation, In-Vitro Efficacy and Intracellular Distribution,” Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry, Vol. 7, No. 11, 1999, pp. 2517- 2524. doi:10.1016/S0968-0896(99)00209-6 [25] F. Kratz, “Albumin as a Drug Carrier: Design of Prodrugs, Drug Conjugates and Nanoparticles,” Journal of Con- trolled Release, Vol. 132, No. 3, 2008, pp. 171-183. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.05.010 [26] K. Inoh, H. Muramatsu, S. Torii, S. Ikematsu, M. Oda, H. Kumai, S. Sakuma, T. Inui, T. Kimura and T. Muramatsu, “Doxorubicin-Conjugated Anti-Midkine Monoclonal An- tibody as a Potential Anti-Tumor Drug,” Japanese Jour- nal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 36, No. 4, 2006, pp. 207-211. doi:10.1093/jjco/hyl004 [27] G. L. Griffiths, M. J. Mattes, R. Stein, S. V. Govindan, I. D. Horak, H. J. Hansen and D. M. Goldenberg, “Cure of SCID Mice Bearing Human B-Lymphoma Xenografts by Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 707 an Anti-CD74 Antibody-Anthracycline Drug Conjugate,” Clinical Cancer Research, Vol. 9, No. 17, 2003, pp. 6567-6571. [28] P. Sapra, R. Stein, J. Pickett, Z. Qu, S. Govindan, V, T. M. Cardillo, H. J. Hanson, I. D. Horak, G. L. Griffiths and D. M. Goldenberg, “Anti-CD74 Antibody-Doxorubicin Con- jugate, IMMU-110, in a Human Multiple Myeloma Xeno- graph and in Monkeys,” Clinical Cancer Research, Vol. 11, No. 14, 2005, pp. 5257-5264. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0204 [29] H. M. Yang and R. A. Reisfeld, “Doxorubicin Conjugated with Monoclonal Antibody Directed to a Human Mela- noma-Associated Proteoglycan Suppresses Growth of Es- tablished Tumor Xenografts in Nude Mice,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 85, 1988, pp. 1189-1193. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.4.1189 [30] P. A. Trail, D. Willner, S. J. Lasch, A. J. Henderson, S. Hofstead, A. M. Casazza, R. A. Firestone, I. Hellstrom and K. E. Hellstrom, “Cure of Xenografted Human Car- cinomas by BR96-Doxorubicin Immunoconjugates,” Science, Vol. 261, No. 5118, 1993, pp. 212-215. doi:10.1126/science.8327892 [31] E. Diener, U. Diner, A. Sinha, S. Xie and R. Vergidis, “Specific Immunosuppression by Immunotoxins Con- taining Daunomycin,” Science, Vol. 231, No. 4734, 1986, pp. 148-150. doi:10.1126/science.3484557 [32] R. O. Dillman, D. E. Johnson, J. Ogden and D. Beidler, “Significance of Antigen, Drug, and Tumor Cell Targets in the Preclinical Evaluation of Doxorubicin, Daunorubi- cin, Methotrexate, and Mitomycin-C Monoclonal Anti- body Immunoconjugates,” Molecular Biotherapy, Vol. 1, 5, 1989, pp. 250-255. [33] M. Page, D. Thibeault, C. Noel and L. Dumas, “Coupling a Preactivated Daunorubicin Derivative to Antibody. A New Approach,” Anticancer Research, Vol. 10, No. 2A, 1990, pp. 353-357. [34] J. Reményi, B. Balázs, S. Tóth, A. Falus, G. Tóth and F. Hudecz, “Isomer-Dependent Daunomycin Release and in Vitro Antitumour Effect of Cis-Aconityl-Daunomycin,” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, Vol. 303, No. 2, 2003, pp. 556-561. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00394-2 [35] J. R. Ogden, K. Leung, S. A. Kunda, M. W. Telander, B. P. Avner, S. K. Liao, G. B. Thurman and R. K. Oldham, “Immunoconjugates of Doxorubicin and Murine Antihu- man Breast Carcinoma Monoclonal Antibodies Prepared Via an N-Hydroxysuccinimide Active Ester Intermediate of Cis-Aconityl-Doxorubicin: Preparation and in Vitro Cytotoxicity,” Molecular Biotherapy, Vol 1, No. 3, 1989, pp. 170-174. [36] C. P. Coyne, T. Jones and T. Pharr, “Synthesis of a Co- valent Gemcitabine-(Carbamate)-[Anti-HER2/neu] im- munochemotherapeutic and Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant SKBr-3 Mammary Carcinoma,” Bioorganic and Medicinal Chem- istry, Vol. 19, No. 1, 2011, pp. 67-76. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2010.11.046 [37] A. I. Shamseddine, M. J. Khalifeh, F. H. Mourad, A. A. Chehal, A. Al-Kutoubi, J. Abbas, M. Z. Habbal, L. A. Malaeb and A. B. Bikhazi, “Comparative Pharmacoki- netics and Metabolic Pathway of Gemcitabine during In- travenous and Intra-Arterial Delivery in Unresectable Pancreatic Cancer Patients,” Clinical Pharmacokinetics, Vol. 44, No. 9, 2005, pp. 957-967. doi:10.2165/00003088-200544090-00005 [38] E. Giovannetti, A. C. Laan, E. Vasile, C. Tibaldi, S. Nan- nizzi, S Ricciardi, A. Falcone, R. Danesi and G. J. Peters, “Correlation between Cytidine Deaminase Genotype and Gemcitabine Deamination in Blood Samples,” Nucleo- sides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids, Vol. 27, No. 6, 2008, pp. 720-725. doi:10.1080/15257770802145447 [39] J. A. Gilbert, O. E. Salavaggione, Y. Ji, L. L. Pelley- mounter, B. W. Eckloff, E. D. Wieben, M. M. Ames and R. M. Weinshilboum, “Gemcitabine Pharmacogenomics: Cytidine Deaminase and Deoxycytidylate Deaminase Gene Resequencing and Functional Genomics,” Clinical Cancer Research, Vol. 12, No. 6, 2006, pp. 1794-1803. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1969 [40] R. L. Alexander, B. T. Greene, S. Torti and V. G. L. Kucera, “A Novel Phospholipid Gemcitabine Conjugate Is Able to Bypass Three Drug-Resistance Mechanisms,” Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology, Vol. 56, No. 1, 2005, pp. 15-21. doi:10.1007/s00280-004-0949-0 [41] R. J. Pietras, M. D. Pegram, R. S. Finn, D. A. Maneval and D. J. Slamon, “Remission of Human Breast Cancer Xenografts on therapy with Humanized Monoclonal An- tibody to HER-2 Receptor and DNA-Reactive Drugs,” Oncogene, Vol. 17, No. 17, 1998, pp. 2235-2249. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202132 [42] R. Marches and J. W. Uhr, “Enhan Cement of the p27Kip1-Mediated Antiproliferative Effect of Trastuzu- mab (Herceptin) on HER2-Overexpressing Tumor Cells,” International Journal of Cancer, Vol. 112, No. 3, 2004, pp. 492-501. doi:10.1002/ijc.20378 [43] M. Sliwkowski, X, J. A. Lofgren, G. D. Lewis, T. E. Ho- taling, B. M. Fendly and J. A. Fox, “Nonclinical Studies Addressing the Mechanism of Action of Trastuzumab (Herceptin),” Seminars in Oncology, Vol. 26, Suppl. 12, 1999, pp. 60-70. [44] N. U. Lin, L. A. Carey, M. C. Liu, J. Younger, S. E. Come, M. Ewend, G. Harris, E. Bullitt, A. D. Van den Abbeele, J. W. Henson, X. Li, R. Gelman, H. J. Burstein, E. Kasparian, D. G. Kirsch, A. Crawford, F. Hochberg and E. P. Winer, “Phase II Trial of Lapatinib for Brain Metastases in Patients with Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Positive Breast Cancer,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 26, No. 12, 2008, pp. 1993-1999. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3588 [45] M. A. Cobleigh, C. L. Vogel, D. Tripathy, N. J. Robert, S. Scholl, L. Fehrenbacher, J. Wolter, V. Paton, S. Shak, G. Lieberman and D. J. Slamon, “Multinational Study of the Efficacy and Safety of Humanized Anti-HER2 Mono- clonal Antibody in Women Who Have HER2-Overex- pressing Metastatic Breast Cancer That Has Progressed after Chemotherapy for Metastatic Disease,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 17, No. 9, 1999, pp. 2639-2648. [46] C. L. Vogel, M. A. Cobleigh, D. Tripathy, J. C. Gutheil, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 708 L. N. Harris, L. Fehrenbacher, D. J. Slamon, M. Murphy, W. F. Novotny, M. Burchmore, S. Shak, S. J. Stewart and M. Press, “Efficacy and Safety of Trastuzumab as a Sin- gle Agent in First-Line Treatment of HER2-Overex- pressing Metastatic Breast Cancer,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 20, No. 3, 2002, pp. 719-726. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.3.719 [47] G. D. Lewis Phillips, G. Li, D. L. Dugger, L. M. Crocker, K. L. Parsons, E. Mai, W. A. Blättler, J. M. Lambert, R. Chari, V, R. J. Lutz, W. L. Wong, F. S. Jacobson, H. Koeppen, R. H. Schwall, S. R. Kenkare-Mitra, S. D. Spencer and M. X. Sliwkowski, “Targeting HER2-Posi- tive Breast Cancer with Trastuzumab-DM1, an Antibody- Cytotoxic Drug Conjugate,” Cancer Research, Vol. 68, No. 22, 2008, pp. 9280-9290. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1776 [48] J. A. García-Sáenz, M. Martín, A. Calles, C. Bueno, L. Rodríguez, J. Bobokova, A. Custodio, A. Casado and E. Díaz-Rubio, “Bevacizumab in Combination with Metro- nomic Chemotherapy in Patients with Anthracycline- and Taxane-Refractory Breast Cancer,” Journal of Chemo- therapy, Vol. 20, No. 5, 2008, pp. 632-639. [49] D. J. Slamon, B. Leyland-Jone, S. Shak, H. Fuchs, V. Paton, A. Bajamonde, T. Fleming, W. Eiermann, J. Wolter and M. Pegram, “Use of Chemotherapy plus Monoclonal Antibody against HER2 for Metastatic Breast Cancer That Overexpress HER2,” The New Eng- land Journal of Medicine, Vol. 344, No. 11, 2001, pp. 786-792. doi:10.1056/NEJM200103153441101 [50] U. Beyer, T. Roth, P. Schumacher, G. Maier, A. Unold, A. W. Frahm, H. H. Fiebig, C. Unger and F. Kratz, “Synthe- sis and In-Vitro Efficacy of Transferring Conjugates of the Anticancer Drug Chlorambucil,” Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, Vol. 41, No. 15, 1998, pp. 2701-2708. doi:10.1021/jm9704661 [51] L. C. Xu, M. Nakayama, K. Harada, A. Kuniyasu, H. Nakayama, S. Tomiguchi, A. Kojima, M. Takahashi, M. Ono, Y. Arano, H. Saji, Z. Yao, H. Sakahara, J. Konishi and Y. Imagawa, “Bis(Hydroxamamide)-Based Bifunc- tional Chelating Agent for 99mTc Labeling of Polypep- tides,” Bioconjugate Chemistry, Vol. 10, No. 1, 1999, pp. 9-17. doi:10.1021/bc980024j [52] Y. Arano, T. Uezono, H. Akizawa, M. Ono, K. Wakisaka, M. Nakayama, H. Sakahara, J. Konishi and A. Yokoyama, “Reassessment of Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic Acid (DTPA) as a Chelating Agent for Indium-111 Labeling of Polypeptides Using a Newly Synthesized Monoreactive DTPA Derivative,” Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, Vol. 39 No. 18, 1996, pp. 3451-3460. doi:10.1021/jm950949+ [53] M. E. Annunziato, U. S. Patel, M. Ranade and P. S. Palumbo, “p-Maleimidophenyl Isocyanate: A Novel He- terbifunctional Linker for Hydroxyl to Thiol Coupling,” Bioconjugate Chemistry, Vol. 4, No. 3, 1993, pp. 212-218. doi:10.1021/bc00021a005 [54] Q. Liu, J. R. de Wijn and C. A. van Blitterswijk, “Cova- lent Bonding of PMMA, PBMA, and Poly(HEMA) to Hydroxyapatite Particles,” Journal of Biomedical Materi- als Research, Vol. 40, No. 2, 1998, pp. 257-263. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199805)40:2<257::AID-JB M10>3.0.CO;2-J [55] X. L. Wang, Y. Huang, J. Zhu, Y. B. Pan, R. He and Y. Z. Wang, “Chitosan-Graft Poly(p-Dioxanone) Copolymers: Preparation, Characterization, and Properties,” Carbohy- drate Research, Vol. 344, No. 6, 2009, pp. 801-807. [56] S. M. Ali, A. R. Khan, M. U. Ahmad, P. Chen, S. Sheikh and I. Ahmad, “Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Gemcitabine-Lipid Conjugate (NEO6002),” Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, Vol. 15, No. 10, 2005, pp. 2571-2574. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.03.046 [57] P. Chen, P. Y. Chien, A. R. Khan, S. Sheikh, S. M. Ali, M. U. Ahmad and I. Ahmad, “In-Vitro and in-Vivo Anti-Cancer Activity of a Novel Gemcitabine-Cardiolipin Conjugate,” Anticancer Drugs, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2006, pp. 53-61. doi:10.1097/01.cad.0000185182.80227.48 [58] L. V. Kiew, S. K. Cheong, K. Sidik and L. Y. Chung, “Improved Plasma Stability and Sustained Release Profile of Gemcitabine via Polypeptide Conjugation,” Interna- tional Journal of Pharmaceutics, Vol. 391, No. 1-2, 2010, pp. 212-220. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.03.010 [59] P. Guo, J. Ma, S. Li, Z. Guo, A. L. Adams and J. M. Gallo, “Targeted Delivery of a Peripheral Benzodiazepine Receptor Ligand-Gemcitabine Conjugate to Brain Tu- mors in a Xenograft Model,” Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology, Vol. 48, No. 2 , 2001, pp. 169-176. doi:10.1007/s002800100284 [60] R. L. Alexander, S. L. Morris-Natschke, K. S. Ishaq, R. A. Fleming and G. L. Kucera, “Synthesis of Cytotoxic Ac- tivity of Two Novel 1-Dodecylthio-2-Decyloxypropyl- 3-Phophatidic Acid Conjugates with Gemcitabine and Cytosine Arabinoside,” Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, Vol. 46, 19, 2003, pp. 4205-4208. doi:10.1021/jm020571x [61] Z. Guo and J. M. Gallo, “Selective Protection of 2’,2’- Difluorodexoycytidine (Gemcitabine),” The Journal of Organic Chemistry, Vol. 64, No. 22, 1999, pp. 8319-8322. doi:10.1021/jo9911140 [62] P. A. Trail, D. Willner, J. Knipe, A. J. Henderson, S. J. Lasch, M. E. Zoeckler, M. D. TrailSmith, T. W. Doyle, H. D. King, A. M. Casazza, J. Brown, S. J. Hofstead, R. S. Greenfield, R. A. Firestone, K. Mosure, K. F. Kadow, M. B. Yang, K. E. Hellstrom and I. Hellstrom, “Effect of linker Variation on the Stability, Potency and Efficacy of Carcinoma-Reactive BR64-Doxorubicin Immunoconju- gates,” Cancer Research, Vol. 57, No. 1, 1997, pp. 100- 105. [63] T. Etrych, T. Mrkvan, B. Ríhová and K. Ulbrich, “Star- Shaped Immunoglobulin-Containing HPMA-Based Con- jugates with Doxorubicin for Cancer Therapy,” Journal of Controlled Release, Vol. 122, No. 1, 2007, pp. 31-38. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.06.007 [64] J. Liu, H. Zhao, K. J. Volk, S. E. Klohr, E. H. Kerns and M. S. Lee, “Analysis of Monoclonal Antibody and Im- munoconjugate Digests by Capillary Electrophoresis and Capillary Liquid Chromatography,” Journal of Chroma- tography A, Vol. 735, No. 1-2, 1996, pp. 357-366. doi:10.1016/0021-9673(95)01054-8 [65] F. Kratz, G. Ehling, H.-M. Kauffmann and C. Unger, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 709 “Acute and Repeat-Dose Toxicity Studies of the (6- Maleimidocaproyl)Hydrazone Derivative of Doxorubicin (DOXO-EMCH), an Albumin-Binding Prodrug of the Anticancer Agent Doxorubicin,” Human & Experimental Toxicology, No. 26, No. 1, 2007, pp. 19-35. doi:10.1177/0960327107073825 [66] D. Lebrecht, A. Geist, U. P. Ketelsen, J. Haberstroh, B. Setzer, F. Kratz and U. Walker, “The 6-Maleimido- caproyl Hydrazone Derivative of Doxorubicin (Doxo- emch) Is Superior to Free Doxorubicin with Respect to Cardiotoxicity and Mitochondrial Damage,” International Journal of Cancer, Vol. 120, No. 4, 2006, pp. 927-934. [67] F. Kratz, U. Beyer, P. Collery, F. Lechenault, A. Cazabat, P. Schumacher, U. Falken and C. Unger, “Preparation, Characterization and In-Vitro Efficacy of Albumin Con- jugates of Doxorubicin,” Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin, Vol. 21, No. 1, 1998, pp. 56-61. doi:10.1248/bpb.21.56 [68] F. Kratz, U. Beyer, T. Roth, N. Tarasova, P. Collery, F. Lechenault, A. Cazabat, P. Schumacher, C. Unger and U. Falken, “Transferrrin Conjugates of Doxorubicin: Syn- thesis, Characterization, Cellular Uptake, and In-Vitro Ef- ficacy,” Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Vol. 87, No. 3, 1998, pp. 338-346. doi:10.1021/js970246a [69] M. N. Kirstein, I. Hassan, D. E. Guire, D. R. Weller, J. W. Dagit, J. E. Fisher and R. P. Remmel, “High-Performance Liquid Chromatographic Method for the Determination of Gemcitabine and 2’,2’-Difluorodeoxyuridine in Plasma and Tissue Culture Media,” Journal of Chromatography B: Biomedical Sciences and Applications, Vol. 835, No. 1-2 , 2006, pp. 136-142. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.03.023 [70] V. Reichelova, F. Albertioni and J. Liliemark, “Determi- nation of 2-Chloro-2’-Deoxyadenosine Nucleotides in Leukemic Cells by Ion-Pair High-Performance Liquid Chromatography,” Journal of Chromatography B: Bio- medical Sciences and Applications, Vol. 682, No. 1, 1996, pp. 115-123. doi:10.1016/0378-4347(96)00048-5 [71] C. P. Coyne, T. Jones, A. Sygula, J. Bailey and L. Pin- chuk, “Epirubicin-[Anti-HER2/neu] Synthesized with an Epirubicin-(C13-Imino)-EMCS Analog: Anti-Neo-plastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant SKBr-3 Mam- mary Carcinoma in Combination with Organic Sele- nium,” Journal of Cancer Therapy, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2011, pp. 22-39. doi:10.4236/jct.2011.21004 [72] C. P. Coyne, T. Jones and R. Bear, “Synthesis of Epirubi- cin-(C3-amide)-[Anti-HER2/neu] utilizing a UV-Photo- activated Epirubicin Intermediate,” Cancer Biotherapy and Radiopharmaceuticals, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2012, pp. 41- 55. doi:10.1089/cbr.2011.1097 [73] U. Beyer, B. Rothen-Rutishauser, C. Unger, H. Wunderli- Allenspach and F. Kratz, “Difference in the Intracellular Distribution of Acid-Sensitive Doxorubicin-Protein Con- jugates in Comparison to Free and Liposomal-Formulated Doxorubicin as Shown by Confocal Microscopy,” Phar- maceutical Research, Vol. 18, No. 1, 2001, pp. 29-38. doi:10.1023/A:1011018525121 [74] J. A. Sinkule, S. T. Rosen and J. A. Radosevich, “Mono- clonal Antibody 44-3A6 Doxorubicin Immunoconjugates: Comparative in Vitro Anti-Tumor Efficacy of Different Conjugation Methods,” Tumour Biology, Vol. 12, No. 4, 1991, pp 198-206. doi:10.1159/000217705 [75] G. P. Sivam, P. J. Martin, R. A. Reisfeld and B. M. Mueller, “Therapeutic Efficacy of a Doxorubicin Im- munoconjugate in a Preclinical Model of Spontaneous Metastatic Human Melanoma,” Cancer Research, Vol. 55, No. 11, 1995, pp. 2352-2356. [76] R. L. Alexander and G. L. Kucera, “Lipid nucleoside Conjugates for the Treatment of Cancer,” Current Phar- maceutical Design, Vol. 11, No. 9, 2005, pp. 1079-1089. doi:10.2174/1381612053507602 [77] P. Lagisetty, P. Vilekar and V. Awasthi, “Synthesis of Radiolabeled Cytarabine Conjugates,” Bioorganic & Me- dicinal Chemistry Letters, Vol. 19, No. 16, 2009, pp. 4764- 4767. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.06.056 [78] F. Castelli, M. G. Sarpietro, M. Ceruti, F. Rocco and L. Cattel, “Characterization of Lipophilic Gemcitabine Prod- rug-Liposomal Membrane Interaction by Differential Scanning Calorimetry,” Molecular Pharmaceutics, Vol. 3, No. 6, 2006, pp. 737-744. doi:10.1021/mp060059y [79] L. H. Reddy, C. Dubernet, S. L. Mouelhi, P. E. Marque, D. Desmaele and P. Couvreur, “A New Nanomedicine of Gemcitabine Displays Enhanced Anticancer Activity in Sensitive and Resistant Leukemia Types,” Journal of Controlled Release, Vol. 124, No. 1-2, 2007, pp. 20-27. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.08.018 [80] S. H. Frost, H. Jensen and S. Lindegren, “In-Vitro Evalua- tion of Avidin Antibody Pretargeting Using [211At]-La- beled and Biotinylated Poly-L-Lysine as Effector Mole- cule,” Cancer, Vol. 116, No. S4, 2010, pp. 1101-1110. doi:10.1002/cncr.24798 [81] H. Karacay, R. M. Sharkey, S. Govindan, V, W. J. McBride, D. M. Goldenberg, H. J. Hansen and G. L. Griffiths, “Development of a Streptavidin-Anti-Carci- noembryonic Antigen Antibody, Radiolabeled Biotin Pretargeting Method for Radioimmunotherapy of Colo- rectal Cancer. Reagent Development,” Bioconjugate Che- mistry, Vol. 8, No. 4, 1997, pp. 585-594. doi:10.1021/bc970102n [82] A. Lau, G. Bérubéand and C. H. ford, “Conjugation of Doxorubicin to Monoclonal Anti- Carcinoembryonic An- tigen Antibody via Novel Thiol-Directed Cross-Linking Reagents,” Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry, Vol. 3, No. 10, 1995, pp. 1299-1304. doi:10.1016/0968-0896(95)00125-Z [83] A. K. Fry, K. F. Schilke, J. McGuire and K. E. Bird, “Synthesis and Anticoagulant Activity of Heparin Immo- bilized ‘End-On’ to Polystyrene Microspheres Coated with End-Group Activated Polyethylene Oxide,” Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Bio- materials, Vol. 94, No. 1, 2010, pp. 187-195. [84] M. H. Vingerhoeds, H. J. Haisma, S. O. Belliot, R. H. Smit, D. J. Crommelin and G. Storm, “Immunoliposomes as Enzyme-Carriers (Immuno-Enzymosomes) for Anti- body-Directed Enzyme Prodrug Therapy (ADEPT): Op- timization of Prodrug Activating Capacity,” Pharmaceu- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 710 tical Research, Vol. 13, No. 4, 1996, pp. 604-610. doi:10.1023/A:1016010524510 [85] K. Fujiwara, M. Yasuno and T. Kitagawa, “Novel Prepa- ration Method of Immunogen for Hydrophobic Hapten, Enzyme Immunoassay for Daunomycin and Adriamycin,” Journal of Immunological Methods, Vol. 45, No. 2, 1981, pp. 195-203. doi:10.1016/0022-1759(81)90213-1 [86] Y. Wang, X. Liu and D. J. Hnatowich, “An improved Synthesis of NHS-MAG3 for Conjugation and Radiola- beling of Biomolecules with [99mTc] at Room Tempera- ture,” Nature Protocols, Vol. 2, No. 4, 2007, pp. 972-978. doi:10.1038/nprot.2007.144 [87] P. Joshi, K. F. Schilke, A. Fry, J. McGuire and K. Bird, “Synthesis and Evaluation of Heparin Immobilized ‘Side- On’ to Polystyrene Microspheres Coated with End-Group Activated Polyethylene Oxide,” International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, Vol. 47, No. 2 , 2010, pp. 98- 103. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2010.05.015 [88] J. Vega, S. Ke, Z. Fan, S. Wallace, C. Charsangavej and C. Li, “Targeting Doxorubicin to Epidermal Growth Fac- tor Receptors by Site-Specific Conjugation of C225 to Poly(L-Glutamic Acid) through a Polyethylene Glycol Spacer,” Pharmaceutical Research, Vol. 20, No. 5, 2003 pp. 826-832. doi:10.1023/A:1023454107190 [89] R. Jin, L. S. Moreira Teixeira, A. Krouwels, P. J. Dijkstra, C. A. van Blitterswijk, M. Karperien and J. Feijen, “Syn- thesis and Characterization of Hyaluronic Acid-Poly (Ethylene Glycol) Hydrogels via Michael addition: An In- jectable Biomaterial for Cartilage Repair,” Acta Biomater, Vol. 6, No. 6, 2010, pp. 1968-1977. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2009.12.024 [90] J. Morales-Sanfrutos, A. Megia-Fernandez, F. Hernan- dez-Mateo, M. D. Giron-Gonzalez, M. D. R. S. Gonzalez and F. Santoyo-Gonzalez, “Alkyl Sulfonyl Derivatized PAMAM-G2 Dendrimers as Nonviral Gene Delivery Vectors with Improved Transfection Efficiencies,” Or- ganic & Biomolecular Chemistry, Vol. 9, No. 3, 2011, pp. 851-864. doi:10.1039/c0ob00355g [91] M. Haas, F. Moolenaar, A. Elsinga, E. A. Van der Wouden, P. E. De Jong, D. K. F. Meijer and D. D. Zeeuw, “Targeting of Doxorubicin to the Urinary Bladder of the Rat Shows Increased Cytotoxicity in the Bladder Urine Combined with an Absence of Renal Toxicity,” Journal of Drug Targeting, Vol. 10, No. 1, 2002, pp. 81-89. doi:10.1080/10611860290007568 [92] American Cancer Society, “Cancer Facts and Figures 2004,” American Cancer Society, 2004, pp. 1-60. [93] H. M. Yang and R. A. Reisfeld, “Pharmacokinetics and Mechanism of Action of a Doxorubicin-Monoclonal An- tibody 9. 2. 27 Conjugate Directed to a Human Melanoma Proteoglycan,” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Vol. 80, No. 14, 1988, pp. 1154-1159. doi:10.1093/jnci/80.14.1154 [94] S. Lutsenko, V, N. B. Feldman and S. E. Severin, “Cyto- toxic and Antitumor Activities of Doxorubicin Conju- gates with the Epidermal Growth Factor and Its Recep- tor-Binding Fragment,” Journal of Drug Targeting, Vol. 10, No. 7, 2002, pp. 567-571. doi:10.1080/1061186021000038058 [95] C. W. Michalski, M. Erkan, D. Sauliunaite, T. Giese, R. Stratmann, C. Sartori, N. A. Giese, H. Friess and J. Kleeff, “Ex-Vivo Chemosensitivity Testing and Gene Expression Profiling Predict Response Towards Adjuvant Gemcit- abine Treatment in Pancreatic Cancer,” British Journal of Cancer, Vol. 99, No. 5, 2008, pp. 760-767. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604528 [96] T. Hoang, K. Kim, A. Jaslowski, P. Koch, P. Beatty, J. McGovern, M. Quisumbing, G. Shapiro, R. Witte and J. H. Schiller, “Phase II Study of Second-Line Gemcitabine in Sensitive or Refractory Small Cell Lung Cancer,” Lung Cancer, Vol. 42, No. 1, 2003, pp. 97-102. doi:10.1016/S0169-5002(03)00273-3 [97] J. Bierau, A. H. van Gennip, R. Leen, R. Meinsma, H. N. Caron and A. B. van Kuilenburg, “Cyclopentenyl Cyto- sine-Induced Activation of Deoxycytidine Kinase In- creases Gemcitabine Anabolism and Cytotoxicity in Neuroblastoma,” Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharma- cology, Vol. 57, No. 1, 2006, pp. 105-113. doi:10.1007/s00280-005-0005-8 [98] V. Santini, G. D’Ippolito, P. A. Bernabei, A. Zoccolante, A. Ermini and P. Rossi-Ferrini, “Effects of Fludarabine and Gemcitabine on Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cell Line HL 60: Direct Comparison of Cytotoxicity and Cellular Ara-C Uptake Enhancement,” Leukemia Re- search, Vol. 20, No. 1, 1996, pp. 37-45. doi:10.1016/0145-2126(95)00106-9 [99] H. Mueller, M. U. Kassack and M. Wiese, “Comparison of the Usefulness of the MTT, ATP and Calcein Assays to Predict the Potency of Cytotoxic Agents in Various Human Cancer Cell Lines,” Biomolecular Screening, Vol. 9, No. 6, 2004, pp. 506-515. doi:10.1177/1087057104265386 [100] E. Ulukaya, F. Ozdikicioglu, A. Y. Oral and M. Dermirci, “The MTT Assay Yields a Relatively Lower Result of Growth Inhibition than the ATP Assay Depending on the Chemotherapeutic Drug Tested,” Toxicol in Vitro, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2008, pp. 232-239. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2007.08.006 [101] M. Varache-Lembège, S. Larrouture, D. Montaudon, J. Robert and A. Nuhrich, “Synthesis and Antiproliferative Activity of Aryl- and Heteroaryl-Hydrazones Derived from Xanthone Carbaldehydes,” European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, Vol. 43, No. 6, 2008, pp. 1336- 1343. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.09.003 [102] M. D. Kars, O. D. Iseri, U. Gunduz and J. Molnar, “Re- versal of Multidrug Resistance by Synthetic and Natural Compounds in Drug-Resistant MCF-7 Cell Lines,” Che- motherapy, Vol. 54, No. 3, 2008, pp. 194-200. doi:10.1159/000140462 [103] H. Huang, E. Pierstorff, E. Osawa and D. Ho, “Active Nanodiamond Hydrogels for Chemotherapeutic Deliv- ery,” Nano Letters, Vol. 7, No. 11, 2007, pp. 3305-3314. doi:10.1021/nl071521o [104] M. C. Dery, C. Van Themsche, D. Provencher, A. M. Mes-Masson and E. Asselin, “Characterization of EN- 1078D, a poorly differentiated human endometrial carci- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Synthesis of Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti-HER2/neu] Utilizing a UV-Photoactivated Gemcitabine Intermediate: Cytotoxic Anti-Neoplastic Activity against Chemotherapeutic-Resistant Mammary Adenocarcinoma SKBr-3 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT 711 noma cell line: A Novel Tool to Study Endometrial Inva- sion In-Vitro,” Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, Vol. 5, 2007, pp. 38-39. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-5-38 [105] B. Spee, M. D. Jonkers, B. Arends, G. R. Rutteman, J. Rothuizen and L. C. Penning, “Specific Down-Regulation of XIAP with RNA Interference Enhances the Sensitivity of Canine Tumor Cell-Lines to Trail and Doxorubicin,” Molecular Cancer, Vol. 5, 2006, p. 34. doi:10.1186/1476-4598-5-34 [106] N. Denora, V. Laquintana, A. Trapani, A. Lopedota, A. Latrofa, J. M. Gallo and G. Trapani, “Translocator Pro- tein (TSPO) Ligand-Ara-C (cytarabine) Conjugates as a Strategy to Deliver Antineoplastic Drugs and to Enhance Drug Clinical Potential,” Molecular Pharmaceutics, Vol. 7, No. 6, 2010, pp. 2255-2269. doi:10.1021/mp100235w [107] W. C. Shen and H. J. Ryser, “Cis-Aconityl Spacer be- tween Daunomycin and Macromolecular Carriers: A Model of pH-Sensitive Linkage Releasing Drug from a Lysosomotrophic Conjugates,” Biochemical and Bio- physical Research Communications, Vol. 102, No. 3, 1981, pp. 1048-1054. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(81)91644-2 [108] Y. Zhang, N. Wang, N. Li, T. Liu and Z. Dong, “The Antitumor Effect of Adriamycin Conjugated with Mono- clonal Antibody against Gastric Cancer In-Vitro and In-Vivo,” Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica, Vol. 27, No. 5, 1992, pp. 325-330. [109] E. Aboud-Pirak, E. Hurwitz, F. Bellot, J. Schlessinger and M. Sela, “Inhibition of Human Tumor Growth in Nude Mice by a Conjugate of Doxorubicin with Monoclonal Antibodies to Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor,” Pro- ceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 86, No. 10, 1989, pp. 3778-3781. doi:10.1073/pnas.86.10.3778 [110] C. P. Coyne, B. W. Fenwick and J. Ainsworth, “Anti- Neoplastic Activity of Chemotherapeutic ‘Loaded’ Neu- trophils against Human Mammary Carcinoma,” Biother- apy, Vol. 10, No. 2, 1997, pp. 145-159. doi:10.1007/BF02678542 [111] M. D. Pegram, A. Lopez, G. Konecny and D. J. Slamon, “Trastuzumab and Chemotherapeutics: Drug Interactions and Synergies,” Seminars in Oncology, Vol. 27, Suppl. 11, 2000, pp. 21-25. [112] D. Slamon and M. Pegram, “Rationale for Trastuzumab (Herceptin) in Adjuvant Breast Cancer Trials,” Seminars in Oncology, Vol. 28, Suppl. 3, 2001, pp. 13-19. doi:10.1053/sonc.2001.22812 [113] E. P. Winer and H. J. Burstein, “New Combinations with Herceptin in Metastatic Breast Cancer,” Oncology, Vol. 61, Suppl. 2, 2001, pp. 50-57. doi:10.1159/000055402 [114] S. Kim, C. N. Prichard, M. N. Younes, Y. D. Yazici, S. A. Jasser, B. N. Bekele and J. N. Myers, “Cetuximab and Ir- inotecan Interact Synergistically to Inhibit the Growth of Orthotopic Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma Xenografts in Nude Mice,” Clinical Cancer Research, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2006, pp. 600-607. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1325 [115] M. Landriscina, F. Maddalena, A. Fabiano, A. Piscazzi, O. La Macchia and M. Cignarelli, “Erlotinib Enhances the Proapoptotic Activity of Cytotoxic Agents and Syner- gizes with Paclitaxel in Poorly-Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma Cells,” Anticancer Research, Vol. 30, No. 2, 2010, pp. 473-480. [116] F. Ciardiello, R. Bianco, V. Damiano, S. De Lorenzo, S. Pepe, S. De Placido, Z. Fan, J. Mendelsohn, A. Bianco and G. Tortora, “Antitumor Activity of Sequential Treat- ment with Topotecan and Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Monoclonal Antibody C225,” Clinical Cancer Research, Vol. 5, No. 4, 1999, pp. 909-916. [117] K. D. Lynn, D. G. Udugamasooriya, C. L. Roland, D. H. Castrillon, T. J. Kodadek and R. A. Brekken, “GU81, a VEGFR2 Antagonist Peptoid, Enhances the Anti-Tumor Activity of Doxorubicin in the Murine MMTV-PyMT Transgenic Model of Breast Cancer,” BMC Cancer, Vol. 10, 2010, p. 397. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-10-397 [118] L. Zhang, D. Yu, D. J. Hicklin, J. A. Hannay, L. M. Ellis and R. E. Pollock, “Combined Anti-Fetal Liver Kinase 1 Monoclonal Antibody (Anti-VEGFR) and Continuous Low-Dose Doxorubicin Inhibits Angiogenesis and Growth of Human Soft Tissue Sarcoma Xenografts by Induction of Endothelial Cell Apoptosis,” Cancer Research, Vol. 62, No. 7, 2002, pp. 2034-2042. [119] L. B. Shih, D. M. Goldenberg, H. Xuan, H. W. Lu, M. J. Mattes and T. C. Hall, “Internalization of an Intact Doxo- rubicin Immunoconjugate,” Cancer Immunology, Immu- notherapy, Vol. 38, No. 2, 1994, pp. 92-98. doi:10.1007/BF01526203 [120] H. J. Hansen, G. L. Ong and H. Diril, “Internalization and Catabolism of Radiolabeled Antibodies to the MHC Class- II Invariant Chain by B-Cell Lymphomas,” Biochemical Journal, Vol. 320, 1996, pp. 293-300. [121] A. C. Stan, D. L. Radu, S. Casares, C. A. Bona and T. D. Brumeanu, “Antineoplastic Efficacy of Doxorubicin En- zymatically Assembled on Galactose Residues of a Mono- clonal Antibody Specific for the Carcinoembryonic Anti- gen,” Cancer Research, Vol. 59, No. 1, 1999, pp. 115- 121. [122] M. Pimm, V, M. A. Paul, T. Ogumuyiwa and R. W. Baldwin, “Biodistribution and Tumour Localization of a Daunomycin-Monoclonal Antibody Conjugate in Nude Mice and Human Tumour Xenografts,” Cancer Immu- nology, Immunotherapy, Vol. 27, No. 3, 1988, pp. 267- 271.