Journal of Cancer Therapy, 2012, 3, 680-688 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jct.2012.325088 Published Online October 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jct) The Relationship between Workplace Stressors and Job Strain with Psychological Distress among Employed Malaysian Breast Cancer Survivors Heng Weay Yong1, Hashim Zailina1*, Jamil O. Z ubaid ah2, Moin Saidi3 1Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Ser- dang, Malaysia; 2Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, Malaysia; 3Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, Malaysia. Email: *zailina@medic.upm.edu.my Received August 7th, 2012; revised September 10th, 2012; accepted September 22nd, 2012 ABSTRACT Evidence showed occupational factors may contribute distress to breast cancer survivors, however, very few studies focused on the occupational factors and job strain among breast cancer survivors. This study examined the relationship between job strain and workplace stressors with psychological distress among employed breast cancer survivors after the completion of their medical treatment. Study subject were outpatients of 2 hospitals and members of 4 breast cancer support groups. They were requested to fill up the Job Content Questionnaires (JCQ), the Hospital Anxiety and Depres- sion Scale (HADS) and the Distress Thermometer (DT) were filled up by the selected respondents. On simple logistic regression, psychological job demand and job strain were significantly associated with anxiety, distress on HADS-T and DT at (p < 0.001). While, psychological job demand (p < 0.001), social support (p = 0.047) and job strain (p < 0.001) were significantly associated with depression. Results showed survivors with high job strain has 4.74 time the odds of having anxiety (p < 0.001). Survivors with high psychological job demand have 8.08 time the odds of getting depres- sion (p < 0.001). On the other hand, social support served as a protective factor of depression, (p = 0.041). Survivors with high psychological job demand were 4.4 time the odds of having distress (HADS-T) (p = 0.012). As a conclusion, survivors who experienced high psychological job demand, low social support and high job strain were reported with anxiety, depression or psychological distress. Keywords: Breast Cancer Survivors; Workplace Stressors; Job Strain; Psychological Distress 1. Introduction The outcome of job strain is workplace stress which is considered as a health hazard which arises from inter- actions of workers and the work demands [1]. Many em- ployers tend to deny the existence of workplace stress. From the employers’ perception, workplace stress is a personal problem. Some argues that one should be able to cope with it if they are employed as it is voluntary and it comes with the job, thus, not considered as a work- place hazard. Through time, more researchers found job strain to be a significant health hazard [2,3]. It is a seri- ous health and safety hazard with devastated effects causing mental illnesses to the workers. It is mainly due to the poor match between work demand with work abil- ity and one does not have a reasonable control over work. Factors from workplace that lead to stress are called workplace stressors. According to Karasek’s Job Demand Model, there are 4 key principal factors contributing to job strain, such as psychological job demand, decision latitude, social support and job insecurity [4]. Psycho- logical job demand refers to the workload, work re- quirements and organizations’ constraints of the workers, while decision latitude includes two dimensions such as skill discretion and decision authority. Skill discretion is the skill and creativity of workers on the job requirement, while decision authority is the flexibility and possibilities of workers to make own decision. The third key factor of workplace stress in job demand model is social support, which refers to support from co-workers, supervisor or management levels and also the interpersonal hostility. The last factor is job insecurity which depends highly on the market requirement for skills and career possibilities. Strong relationships were found between job strain with emotional distress (anxiety, depression), short term health effects (headache, nausea) and long term health effects (cardiovascular disease, cancer) [5,6]. Previous *Corresponding author. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  The Relationship between Workplace Stressors and Job Strain with Psychological Distress among Employed Malaysian Breast Cancer Survivors 681 findings showed workplace related factors such as high psychological demand, low decision latitude and inter- personal conflict are common predictor of psychological distress such as anxiety and depression, fatigue and some physical illness, while social support served as a protec- tive factors to psychological distress [7,8]. Job strain and its associated effects lead to poor work performance and poor ability to conduct work task but unfortunately, the presence of job strain is unnoticed [9,10]. In Malaysia, a study showed that about 52.3% of the breast cancer cases were below 50 years [11]. Therefore, most of the survi- vors were capable of returning to work after their treat- ment. Many survivors continued employments after di- agnosis and treatment, because they believed that em- ployment was an important measure of recovery [12]. Females had significantly higher job strain than male cancer survivors [13]. Many survivors who return to work experienced difficulties due to physical changes, psychological distress associated with cancer as well as the treatment and inadequate work-related support [14]. There is a substantial evidence that occupational and en- vironmental factors contribute to the burden of distress, however, few studies had focused on employed breast cancer survivors. This study examined the relationship between job strain and workplace stressors with psycho- logical distress level of breast cancer survivors after re- turning to work. 2. Materials and Methods In this study, respondents were made up of breast cancer survivors who were outpatients of 2 hospitals (Hospital Kuala Lumpur and Hospital Seberang Jaya) and mem- bers of 4 breast cancer support groups (Segamat, Johor Bahru, Bangi and Ipoh). The respondents were required to complete the Job Content Questionnaires (JCQ), Hos- pital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and Distress Thermometer (DT). Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) developed by Karasek et al. [7] was used to determine the occupational stress- ors and levels of job strain at the workplace. This ques- tionnaire was developed based on the demand-control model. The 25 items of JCQ consisted of 4 scales. They are the Psychological Job Demand (5 items), Decision Latitude (9 items), Social Support (8 items) and Job In- security (3 items). These scales are determinants of job strain. The demand-control model showed high job strain occurred when Psychological Job Demand was high or Decision Latitude was low whereas Social Support served as the protective factors for job strain. Each item in the scales were given scores on a 4-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, agree and strongly agree; or often, sometimes, rarely and never). The scores were then calculated by using formula for the Job Content In- strument Scale provided in the JCQ. Psychological distress measured by Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and Distress Thermome- ter (DT). HADS is a 14-items scale designed by Zig- mond et al. [15] which is used to measure the depression and anxiety levels. This 14 items questionnaire can be divided into 2 subscales, in which 7 items measure the anxiety level (HADS-A) and depression level (HADS-D) respectively. Each item was scored on a 4-point Likert scale of 0 - 3, giving each anxiety and depression a maxi- mum score of 21 respectively and a total maximum score of 42 for both. Scores of <8 were considered as “non- cases” or normal while scores of ≥8 are considered as cases. A total score of ≥15 indicates psychological dis- tress (HADS-T) [16,17]. Distress Thermometer (DT) with problem checklist is a screening measurement developed by National Com- prehensive Cancer Network [18], assesses and identifies the psychological distress and its contributing factors. Distress thermometer scale consists of 11 points, which ranged from 0 for no distressed to 10 for extreme distress. Respondents were requested to circle the numbers that represent their distress levels in the past week. Respon- dents with score of ≥4 were considered as having dis- tress [19]. The problem checklist consists of 33 items which are distress contributing factors. These 33 items are categorized into 5 categories such as practical (4 items), family (3 items), emotional (8 items), spiritual or religious (3 items) and physical (23 items). 3. Results 3.1. Socio-Demographic Background and Occupational Information of Respondents A total of 150 breast cancer survivors made up of 114 (76.0%) hospital outpatients and 36 (24%) members of breast cancer support group were recruited. The mean age of respondents were 49.1 (7.1) years. They were mainly Malay (50.6%), followed by Chinese (44.7%) and Indian (4.7%). The education levels ranged from no for- mal to tertiary education, the majority with secondary education (52.0%). Most were married (76.0%), diag- nosed with Stage II cancer (57.3%) and more than half did not have family history of breast cancer (56.7%). Majority were employed in the private sector (60.0%) followed by the government sector (24.7%) and self- employed (25.3%). Most respondents have normal work hours (94.0%) and did not use chemical in their work- place (85.3%). They were currently employed for 5.8 (6.4) years and the mean income was RM 2172.8 (1548.4) (Table 1). Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  The Relationship between Workplace Stressors and Job Strain with Psychological Distress among Employed Malaysian Breast Cancer Survivors 682 Table 1. Socio-demographic and occupational information of respondents. Variables No. of subjects (%) Recruitments of respondents Hospital Support group 114 (76) 36 (24) Age (Mean ± std dev.) 49.11 ± 7.10 Ethnicity Malay Chinese Indian 76 (50.7) 67 (44.7) 7 (4.6) Marital status Married Single Widowed Divorced 114 (76.0) 17 (11.3) 13 (8.7) 6 (4.0) Education level No formal education Primary Secondary Tertiary 6 (4.0) 29 (19.3) 78 (52.0) 37 (24.7) Stages of cancer Stage I Stage II 64 (42.7) 86 (57.3) Family history of breast cancer Yes No 65 (43.3) 85 (56.7) Duration of employment (years) (Mean ± std dev.) 19.34 ± 10.32 Employment Private Government Self-employed 90 (60.0) 37 (24.7) 23 (15.3) Shift work Normal hours Shift work 141 (94.0) 9 (6.0) Use of chemical at the workplace No Yes 128 (85.3) 22 (14.7) Current employment (years) (Mean ± std dev.) 5.8 ± 6.4 Salary incomes (RM) (Mean ± std dev.) 2172.8 ± 1548.4 N = 150. 3.2. Prevalence of Work Stressors and Job Strain Most of the respondents reported high psychological job demand (52.7%), high decision latitude (50.7%), high social support (51.3%) and high job insecurity (56.7%). While, only 26.0% reported high job strain (Table 2). 3.3. Psychological Distress Levels Using HADS and DT By using the recommended threshold value of 8 for dis- order caseness (including borderline cases), 23.3% of the respondents were classified as anxious and 19.3% as de- pressed, while 22.0% were distressed (HADS-T ≥ 15) (Table 3). Table 4 shows the distress levels of re- spondents according to the DT and its checklist. The prevalence of distress was 14.7% according to the DT. The frequencies of items checked in the checklist were examined by multiple response analysis. The most com- mon problems associated with distressed (N = 60) were those related to family (70.0%), followed by emotional problems such as sad, lonely, angry , remorse and disap- pointed (65.0%), physical problems and symptoms such as diarrhea, respiratory difficulties, hot flashes, dryness, insomnia and tiredness (60.0%), practical problem such health care, finance, housing and transport (50.0%) and a few on spiritual or religious such as loss hope or direc- tion in life (15.0%). 3.4. Relationship between Work Stressors and Job Strain with Psychological Distress Using Both HADS and DT Tables 5-8 showed the statistics on the influence of Table 2. Distributions of workplace stressors and job strain of respondents. Variables n (%) MedianRange Psychological job demand High Low 79 (52.7) 71 (47.3) 32 18 - 45 Decision latitude High Low 76 (50.7) 74 (49.3) 58 30 - 80 Social support High Low 77 (51.3) 73 (48.7) 24 8 - 32 Job insecurity High Low 85 (56.7) 65 (43.3) 9 6 - 12 Job strain High Low 39 (26.0) 111 (74.0) N = 150. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  The Relationship between Workplace Stressors and Job Strain with Psychological Distress among Employed Malaysian Breast Cancer Survivors 683 Table 3. Distributions of psychological distress levels using HADS. Variables Frequency (n) Percentage (%) HADS Anxiety score Normal (0 - 7) Anxious (≥8) 115 35 76.7 23.3 Depression Normal (0 - 7) Depressed (≥8) 121 29 80.7 19.3 Psychological Distress Normal (0 - 14) Distressed (≥15) 117 33 78.0 22.0 N = 150. Table 4. Prevalence of distress using DT with checklist. Variables Frequency (N) Percentage (%) Psychological distress Normal Distressed 128 22 85.3 14.7 Problem checklist categories (N = 60) Family Emotional Physical Practical Spiritual/religious 42 39 36 30 9 70.0 65.0 60.0 50.0 15.0 Statistical test-multiple response analysis N = 150. selected socio-demographic factors, workplace stressors and job strain on anxiety, depression and distress using both the HADS and DT scales. Simple logistic regression analysis of 2 socio-demographic factors and 5 work- place stressors showed psychological job demand and job strain were significantly associated with anxiety on HADS-A (p < 0.001), distress on HADS-T (p < 0.001) and DT (p < 0.001). While, psychological job demand (p < 0.001), social support (p = 0.047) and job strain (p < 0.001) were significantly associated with depression on HADS-D. No significant association found between an- xiety, depression and distress with job insecurity using both HADS and DT. Statistics showed socio-demogra- phic including employment and stage of cancer were not significantly related to anxiety, depression and distress using both HADS and DT (p > 0.05). Table 5 shows that job strain is the only predictor for anxiety. Results showed that survivors with high job strain have 4.74 times the odds of having anxiety com- pared to those with low job strain (p < 0.001). Table 6 shows survivors with high psychological job demand to have 8.08 times the odds of getting depression (p < 0.001). On the other hand, social support was a protec- tive factor for depression (p = 0.041). Tables 7 and 8 shows psychological job demand was predictor for both distress using HADS-T and DT while job strain is the predictor for distress on DT. Survivors with high psychological job demand were 4.4 times the odds of having distress (HADS-T) (p = 0.012). Table 8 shows that survivors with high psychological job demand were 6.09 times the odds of having distressed (p = 0.032) and survivors with high job strain were 3.17 times the odds of having distressed (p = 0.037) on DT. These re- sults reflected a good overall fitness of the model when Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p > 0.05) and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) were at least 70% in the accuracy discrimination of cases (Tables 5-8). 4. Discussion Psychological morbidity including anxiety, depression and distress are common health issues among cancer survivors and can further lead to the hospitalization of distress patients. Thus, there is a need to identify the causes and psychological morbidity of survivors. This study showed the prevalence of anxiety (7.3%), depress- sion (4.7%) and distress (22%) among respondents using the HADS while 14.7% distressed on DT and this preva- lence were lower than other local studies [20,21] and overseas studies [22,23]. The difference between the prevalence may be due to the difference in the selection of respondents. This study was among patients who had completed all their medical treatments, however, others were among breast cancer patients who were undergoing chemotherapy. Findings showed the breast cancer pa- tients suffered incredible stress during their treatment thus their distress level were higher, whereas those who had completed the active treatment were less stressed [24,25]. Previous study found that the prevalence of anxiety and depression among employed survivors were lower than the unemployed because they felt that they had better chance of improving their social position and securing more social support [26]. Those with anxiety would normally have the coexis- tence of depression [27]. Similar findings occurred among the Malaysian breast cancer survivors as well, where 15.3% of the respondents with anxiety were de- pressed at the same time. However, this prevalence was lower as compared to a data from a National Morbidity Survey which showed that the prevalence of patients with coexistence of depression and anxiety were 51% [27], however, another local study found a prevalence of 12.5% for coexistence of depression and anxiety among cancer patients [21]. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  The Relationship between Workplace Stressors and Job Strain with Psychological Distress among Employed Malaysian Breast Cancer Survivors Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT 684 Table 5. Predictor of anxiety using HADS-A models. SLR1 MLR2 Variables b Crude OR (95% CI)p b Adjusted OR (95% CI) p Employment Government Private Self-employed 0.00 –0.72 –0.31 1 0.49 (0.20, 1.16) 0.74 (0.23, 2.34) - 0.102 0.603 - - - Stage of cancer Stage I Stage II 0.00 0.62 1 1.87 (0.84, 4.16) - 0.128 - - - Psychological Job Demand Low High 0.00 1.41 1 4.09 (1.71, 9.76) - 0.002** - - - Decision Latitude Low High 0.00 0.04 1 1.04 (0.49, 2.22) - 0.918 - - - Social Support Low High 0.00 –0.60 1 0.13 (0.26, 1.19) - 0.550 - - - Job Insecurity Low High 0.00 –0.28 1 0.76 (0.36, 1.62) - 0.476 - - - Job Strain Low High 0.00 1.56 1 4.74 (2.10, 10.70) - <0.001*** 0.00 1.56 1 4.74 (2.10, 10.70) - <0.001*** 1SLR = Simple Logistic Regression; 2MLR = Multiple Logistic Regression; **Significant at p < 0.01;***Significant at p < 0.001; N = 150; Hosmer-Lemeshow test, (p = 0.277), and area under the ROC curve (73.2%) were applied to check the model fitness. Results showed psychological job demand were sig- nificant predictor of depression (OR = 8.08, p < 0.001), distress (OR = 4.4, p = 0.012) using HADS-D and HAD-T respectively as well as DT (OR = 6.09, p = 0.032). High psychological job demand was capable of inducing depression and psychological distress. Similar to other studies which found that psychological job de- mand as an indicator for psychological morbidity dis- orders among workers and significant association found between job demand with psychological distress or men- tal illnesses [8,9,28]. Workers with high psychological job demand tend to get psychological distress, which seemed to also occur among breast cancer survivors [29]. Evidence showed decision latitude was significantly associated with psychological morbidity either with psy- chological job demand or on its own. Although, previous researches showed decision latitude was related with psychological disorders and served as a protective factor for distress [8] however, in this study, decision latitude was not a predictor and was not significantly related to anxiety, depression or distress as found by Bultmann, et al. [30]. Majority of respondents reported high level of social support (51.3%), which meant that there were supports from their co-workers or supervisors. In this study, sig- nificant association was found between social support with depression and it served as a protective factor for depression (OR = 0.39, p = 0.041). Similar to other stud- ies [28,31], who also found that high social support was a protective factor as a buffered effect on psychological distress. Besides, Kawakami et al. [28] showed worksite support was an important factor which would influence job strain and also mental health. Workplace problems are usually related to poor interaction with colleagues and lack of support from co-workers and employers [32]. Positive social support encouraged them to return to work and hence reduced the risk of work disability or distress, as shown in some studies [33]. Those with high social support would have a low distress and better qual- ity of life [34].  The Relationship between Workplace Stressors and Job Strain with Psychological Distress among Employed Malaysian Breast Cancer Survivors 685 Table 6. Predictor of depression using HADS-D models. SLR1 MLR2 Variable b Crude OR (95% CI)p b Adjusted OR (95% CI) p Employment Government Private Self-employed 0.00 –0.70 –0.29 1 0.50 (0.20, 1.25) 0.75 (0.22, 2.56) - 0.138 0.646 - - - Stage of cancer Stage I Stage II 0.00 0.43 1 1.53 (0.66, 3.57) - 0.323 - - - Psychological Job Demand Low High 0.00 2.05 1 7.76 (2.54, 23.64) - <0.001*** 0.00 2.09 1 8.08 (2.62, 24.96) - <0.001*** Decision Latitude Low High 0.00 –0.12 1 0.89 (0.40, 1.99) - 0.774 - - - Social Support Low High 0.00 –0.86 1 0.42 (0.18, 0.99) - 0.047* 0.00 –0.93 1 0.39 (0.16, 0.96) - 0.041* Job Insecurity Low High 0.00 –0.08 1 1.08 (0.48, 2.44) - 0.86 - - - Job Strain Low High 0.00 1.66 1 5.24 (2.22, 12.41) - <0.001*** - - - 1SLR = Simple Logistic Regression, 2MLR = Multiple Logistic Regression, *Significant at p < 0.05, ***Significant at p < 0.001, N = 150, Hos- mer-Lemeshow test, (p = 0.289), and area under the ROC curve (78.5%) were applied to check the model fitness. Table 7. Predictor of psychological distress using HADS-T models. SLR1 MLR2 Variables b Crude OR (95% CI)p b Adjusted OR (95% CI) p Employment Government Private Self-employed 0.00 –0.60 –0.42 1 0.55 (0.23, 1.33) 0.66 (0.20, 2.22) - 0.184 0.498 - - - Stage of cancer Stage I Stage II 0.00 0.51 1 1.66 (0.74, 3.72) - 0.222 - - - Psychological Job Demand Low High 0.00 1.98 1 7.25 (2.62, 20.08) - <0.001*** 0.00 1.48 1 4.40 (1.38, 13.99) - 0.012* Decision Latitude Low High 0.00 0.04 1 1.04 (0.48, 2.26) - 0.912 - - - Social Support Low High 0.00 –0.78 1 0.46 (0.21, 1.02) - 0.054 - - - Job Insecurity Low High 0.00 –0.11 1 0.90 (0.41, 1.95) - 0.781 - - - Job Strain Low High 0.00 1.70 1 5.49 (2.39, 12.61) - <0.001*** - - - 1SLR = Simple Logistic Regression, 2MLR = Multiple Logistic Regression,*Significant at p < 0.05, ***Significant at p < 0.001, N = 150, Hos- mer-Lemeshow test, (p = 0.182), and area under the ROC curve (77.0%) were applied to check the model fitness. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  The Relationship between Workplace Stressors and Job Strain with Psychological Distress among Employed Malaysian Breast Cancer Survivors 686 Table 8. Predictor of distress using DT models. SLR1 MLR2 Variables b Crude OR (95% CI) p b Adjusted OR (95% CI) p Employment Government Private Self-employed 0.00 –0.91 0.01 1 0.40 (0.14, 1.14) 1.01 (0.29, 3.56) - 0.087 0.991 - - - Stage of cancer Stage I Stage II 0.00 0.79 1 2.21 (0.81, 6.01) - 0.12 - - - Psychological Job Demand Low High 0.00 2.46 1 11.70 (2.62, 52.13) - 0.001** 0.00 1.81 1 6.09 (1.17, 31.77) - 0.032* Decision Latitude Low High 0.00 –0.03 1 0.97 (0.39, 2.40) - 0.946 - - - Social Support Low High 0.00 –0.95 1 0.39 (0.15, 1.01) - 0.053 - - - Job Insecurity Low High 0.00 0.12 1 1.12 (0.45, 2.82) - 0.804 - - - Job Strain Low High 0.00 1.98 1 7.21 (2.73, 19.07) - <0.001*** 0.00 1.16 1 3.17 (1.07, 9.05) - 0.037* 1SLR = Simple Logistic Regression, 2MLR = Multiple Logistic Regression, *Significant at p < 0.05, **Significant at p < 0.01, ***Significant at p < 0.001, N = 150, Hosmer-Lemeshow test, (p = 0.833), and area under the ROC curve (84.1%) were applied to check the model fitness. In general population, high job strain was a common contributor to mental disorders such as anxiety, depres- sion or distress [6,7]. However, job strain after returning to work among cancer survivors was not given attention with few studies focused on these. To date, only one study by Gudbergsson et al. [13] was carried out on job strain among primary-treated cancer survivors. The study found job strain was not related with survivorship but with socio-demographic, anxiety and personality trails. Similarly, this study showed 26% of the employed sur- vivors had high job strain which was a significant pre- dictor for anxiety and distress. However, none of the socio-demographic variable or cancer history was related to job strain and psychological distress. Just as other studies which found cancer diagnosis stage not signifi- cantly related to distress or psychiatric morbidity [21]. Little attention was given on job strain and distress by medical practitioners during their treatment follow-up, made it difficult to identify and recognized these prob- lems among the cancer survivors. There might be also be other environmental factors which influenced psycho- logical morbidity such as family and diseases factors. This study had limitations in which the results were based on self-reported measures, thus, method bias, which resulted in shared variance of the measurement attributed to instrument rather than association between constructs might occurred. Sampling bias might also occur because unrandomized sampling. Work-related information on cancer cases are not easily available due to high unem- ployed rate of survivors, Only 150 survivors participated in this study. Besides these, respondents may have high tendency of denial or not being honest about their dis- tress conditions to avoid being treated as mentally ill patients. Improvement over treatment and diagnosis had led more researches to focus on psychological morbidity; however, factors contributing to distress were not em- phasized. Future study should focus the detail aspects of job strain among cancer survivors who return to work after their treatment. An effective intervention and awareness on survivors’ needs so as to overcome their distress level should be recommended to the health care Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  The Relationship between Workplace Stressors and Job Strain with Psychological Distress among Employed Malaysian Breast Cancer Survivors 687 workers, physician or social workers, to reduce the prevalence of distress or workplace stress as well as to encourage more survivors to return to work after cancer diagnosis and treatment, and at the same time increase their quality of life. 5. Conclusion As a conclusion, among all workplace stressors studied, only psychological job demand, social support and job strain were factors that influenced distress among sur- vivors. Survivors who experienced high psychological job demand, low social support and high job strain were reported with psychological distress. Psychological job demand and job strain were significant predictor for anxiety, depression, distress on both HADS-T and DT scales. While, social support served as a protective factor for depression. REFERENCES [1] S. Sauter, L. Murphy, M. Colligan, N. Swanson, J. Hur- rell Jr., F. Scharf Jr., R. Sinclair, P. Grubb, L. Goldenhar, T. Alterman, J. Johnston, A. Hamilton and J. Tisdal, “Stress at Work,” National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Cincinnati, 1999. [2] M. Jarvis, “Teacher Stress: A Critical Review of Recent Findings and Suggestions for Future Research Direc- tions,” 2002. http://www.isma.org.uk/stressnw/teachstress.htm [3] J. P. Seward and R. C. Larsen, “Occupational and Envi- ronmental Medicine,” In: J. Ladou, Ed., Occupational and Environmental Medicine, McGraw Hill, New York, 2000, pp. 579-594. [4] R. Karasek, N. Kawakami, C. Brisson, I Houtman, P. Bongers and B. Amick, “The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): An Instrument for Internationally Comparative Assessment of Psychosocial Job Characteristics,” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, Vol. 3, No. 4, 1998, pp. 322-355. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.3.4.322 [5] L. E. Bourne Jr. and R. A. Yaroush, “Stress and Cogni- tion: A Cognitive Psychological Perspective,” Unpub- lished Manuscript, NASA Grant NAG2-1561, 2003. [6] S. Stansfeld and B. Candy, “Psychosocial Work Envi- ronment and Mental Health—A Meta-Analytic Review,” Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment Health, Vol. 32, No. 6, 2006, pp. 443-462. doi:10.5271/sjweh.1050 [7] R. Karasek and T. Theorell, “Healthy Work: Stress, Pro- ductivity and the Reconstruction of the Working Life,” Basic Books, New York, 1990. [8] S. Stansfeld, “Work, Personality and Mental Health,” British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 181, No. 2, 2002, pp. 96-98. [9] Z. A. Emilia and N. Hassim, “Work-Related Stress and Coping: A Survey on Medical and Surgical Nurses in a Malaysian Teaching Hospital,” Jabatan Kesihatan Mas- yarakat, Vol. 13, No. 1, 2007, pp. 55-66. [10] J. A. Hansen, M. Feuerstein, L. C. Calvio and C. H. Olsen, “Breast Cancer Survivors at Work,” Journal of Occupa- tional and Environmental Medicine, Vol. 50, No. 7, 2008, pp. 777-784. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e318165159e [11] A. M. Rahmat, “Malaysia and Breast Cancer,” 2005. http://www.isnare.com/?aid= 10518&ca=Cancer+Survival [12] A. G. E. M. de Boer, T. Taskila, A. Ojajarvi, F. J. H. van Dijk and J. H. A. M. Verbeek, “Cancer Survivors and Umployment. A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression,” Journal of American Medical Association, Vol. 301, No. 7, 2009, pp. 753-762. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.187 [13] S. B. Gudbergsson, S. D. Fossa, B. Sanne and A. A. Dahl, “A Controlled Study of Job Strain in Primary-Treated Cancer Patients without Metastases,” Acta Oncology, Vol. 46, No. 4, 2007, pp. 534-544. doi:10.1080/02841860601156132 [14] C. J. Bradley, H. L. Bednarek and D. Neumark, “Breast Cancer and Women’s Labor Supply,” Health Services Research Journal, Vol. 37, No. 5, 2002, pp. 1309-1328. [15] A. Zigmond and P. R. Snaith, “The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale,” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, Vol. 67, 6, 1983, pp. 361-370. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [16] M. Cohen, R. G. Hoffman, C. Cromwell, J. Schmeidler, F. Ebrahim, G. Carrera, F. Endorf, C. A. Alfonso and J. M. Jacobson, “The Prevalence of Distress in Persons with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection,” Psychoso- matics, Vol. 43, No. 1, 2002, pp. 10-15. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.43.1.10 [17] E. J. Shim, Y. W. Shin, H. J. Jeon and B. J. Hahm, “Dis- tress and Its Correlates in Korean Cancer Patients: Pilot Use of the Distress Thermometer and the Problem List,” Psycho-Oncology, Vol. 17, No. 6, 2008, pp. 548-555. doi:10.1002/pon.1275 [18] NCCN-National Comprehensive Cancer Network, “Prac- tice Guidelines in Oncology—V. Distress Management: National Comprehensive Cancer Network,” 2002. [19] S. Ransom, P. B. Jacobsen and M. Booth-Jones, “Vali- dation of the Distress Thermometer with Bone Marrow Transplant Patients,” Psycho-Oncology, Vol. 15, No. 7, 2006, pp. 604-612. doi:10.1002/pon.993 [20] H. Zailina, H. W. Yong, M. S. Zalilah and H. Y. Yong, “Psychological Distress among Breast Cancer Survivors,” In: M. S. Zalilah, H. Zailina, M. Kandiah and R. Asmah, Eds., Health and Nutrition of Cancer Survivors in Malay- sia, Universiti Putra Malaysia Press, Serdang, 2011, pp. 88-101. [21] N. Zainal, K. Hui, T. Hang and A. Bustam, “Prevalence of Distress in Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemother- apy,” Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 3, No. 4, 2007, pp. 219-223. [22] L. Grassi, E. Rossi, S. Sabato, G. Cruciani and M. Zambelli, “Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosocial Variables in Breast Cancer,” Psychosomatic, Vol. 45, No. 6, 2004, pp. 483-491. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.45.6.483 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  The Relationship between Workplace Stressors and Job Strain with Psychological Distress among Employed Malaysian Breast Cancer Survivors Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT 688 [23] P. Lueboonthavatchai, “Prevalence and Psychosocial Factors of Anxiety and Depression in Breast Cancer Pa- tients,” Journal of Medical Association of Thailand, Vol. 90, No. 10, 2007, pp. 2164-2174. [24] F. C. Atesci, B. Baltalarli, N. K. Oguzhanoglu, F. Karadag, O. Ozdel and N. Karagoz, “Psychiatric Morbid- ity among Cancer Patients and Awareness of Illness,” Support Care Cancer, Vol. 12, No. 3, 2004, pp. 161-167. doi:10.1007/s00520-003-0585-y [25] J. Y. Yen, C. H. Ko, C. F. Yen, M. J. Yang, C. Y. Wu, C. H. Juan and M. F. Hou, “Quality of Life, Depression and Stress in Breast Cancer Women Outpatients Receiving Active Therapy in Taiwan,” Psychiatry Clinical Neuro- sciences, Vol. 60, No. 2, 2006, pp. 147-153. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01479.x [26] S. Rosensfield, “The Effects of Women’s Employment: Personal Control and Sex Differences in Mental Health,” Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Vol. 30, No. 1, 1989, pp. 77-91. doi:10.2307/2136914 [27] T. A. Grady-Weliky, “Comorbidity and Its Implication on Treatment: Change over the Life Span,” Syllabus and Proceedings Summary, American Psychiatric Association 2002 Annual Meeting, Philadelphia, 2002, p. 295. [28] N. Kawakami and T. Naratani, “Epidemiology of Job Stress and Health in Japan: Review of Current Evidence and Future Direction,” Industrial Health, Vol. 37, No. 2, 1999, pp. 174-186. doi:10.2486/indhealth.37.174 [29] K. Wilkins and M. P. Beaudet, “Work Stress and Health,” Health Reports, Vol. 10, No. 3, 1998, pp. 47-62. [30] U. Bultmann, I. J. Kant, P. A. van den Brandt and S. V. Kasl, “Psychosocial Work Characteristics as Risk Factors for the Onset of Fatigue and Psychological Distress: Pro- spective Results from the Maastricht Cohort Study,” Psychological Medicine, Vol. 32, No. 2, 2002, pp. 333- 345. doi:10.1017/S0033291701005098 [31] R. Karasek, B. Gardell and J. Lindell, “Work and Non- Work Correlated of Illness and Behaviours in Male and Female Swedish White Collar Workers,” Journal of Oc- cupational Behavior, Vol. 8, No. 3, 1987, pp. 187-207. doi:10.1002/job.4030080302 [32] E. Maunsell, C. Brisson, L. Dubois, S. Lauzier and A. Fraser, “Work Problems after Breast Cancer: An Explo- ratory Qualitative Study,” Psycho-Oncology, Vol. 8, No. 6, 1999, pp. 467-473. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199911/12)8:6<467::AID- PON400>3.0.CO;2-P [33] E. Spelten, M. Sprangers and J. Verbek, “Factors Re- ported to Influence The Return to Work of Cancer Survi- vors: A Literature Review,” Psycho-Oncology, Vol. 11, No. 2, 2002, pp. 124-131. doi:10.1002/pon.585 [34] F. Ogce, S. Ozkan and B. Baltalarli, “Psychosocial Stres- sors, Social Support and Socio-Demographic Variables as Determinants of Quality of Life of Turkish Breast Cancer Patients,” Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2007, pp. 77-82.

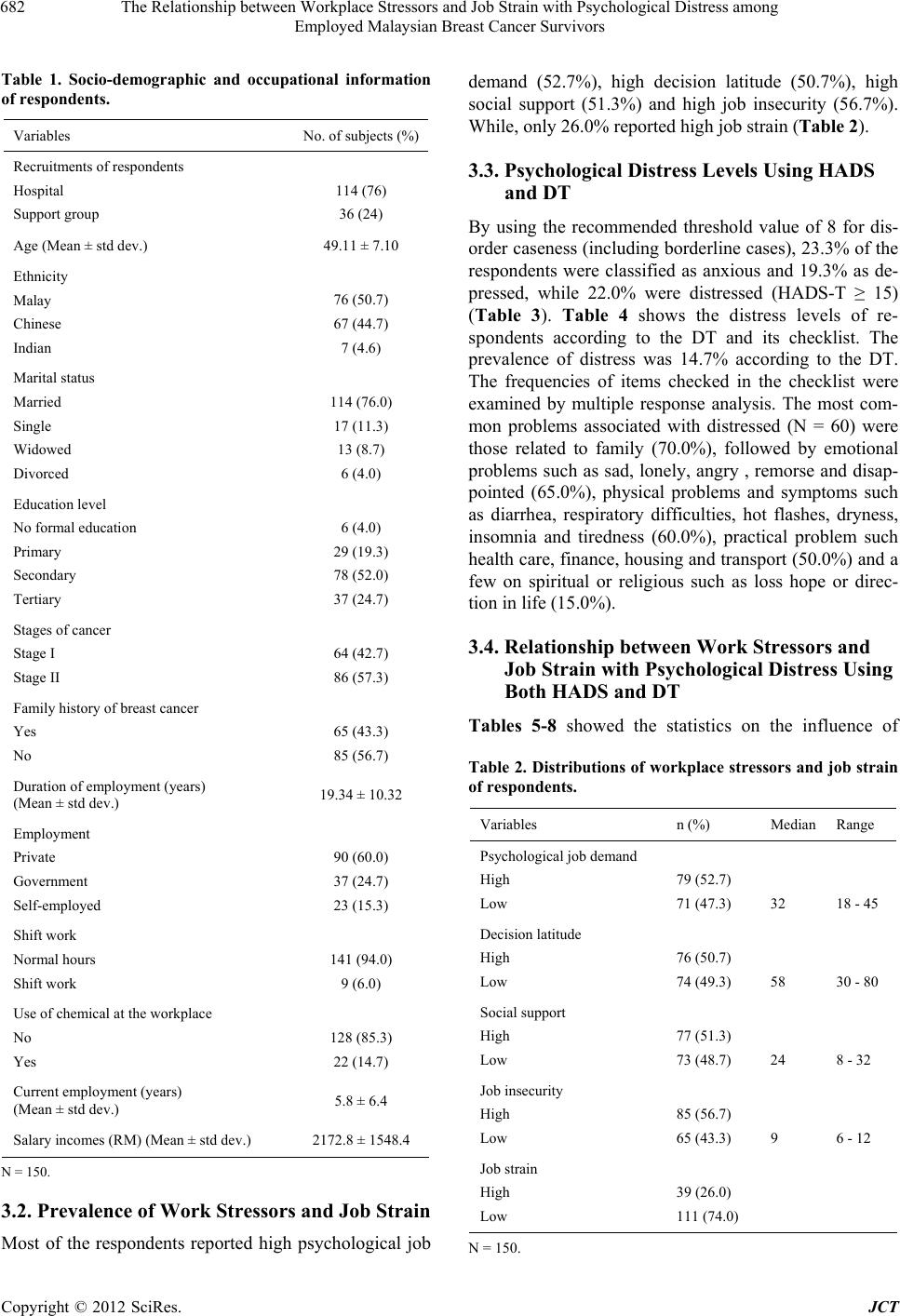

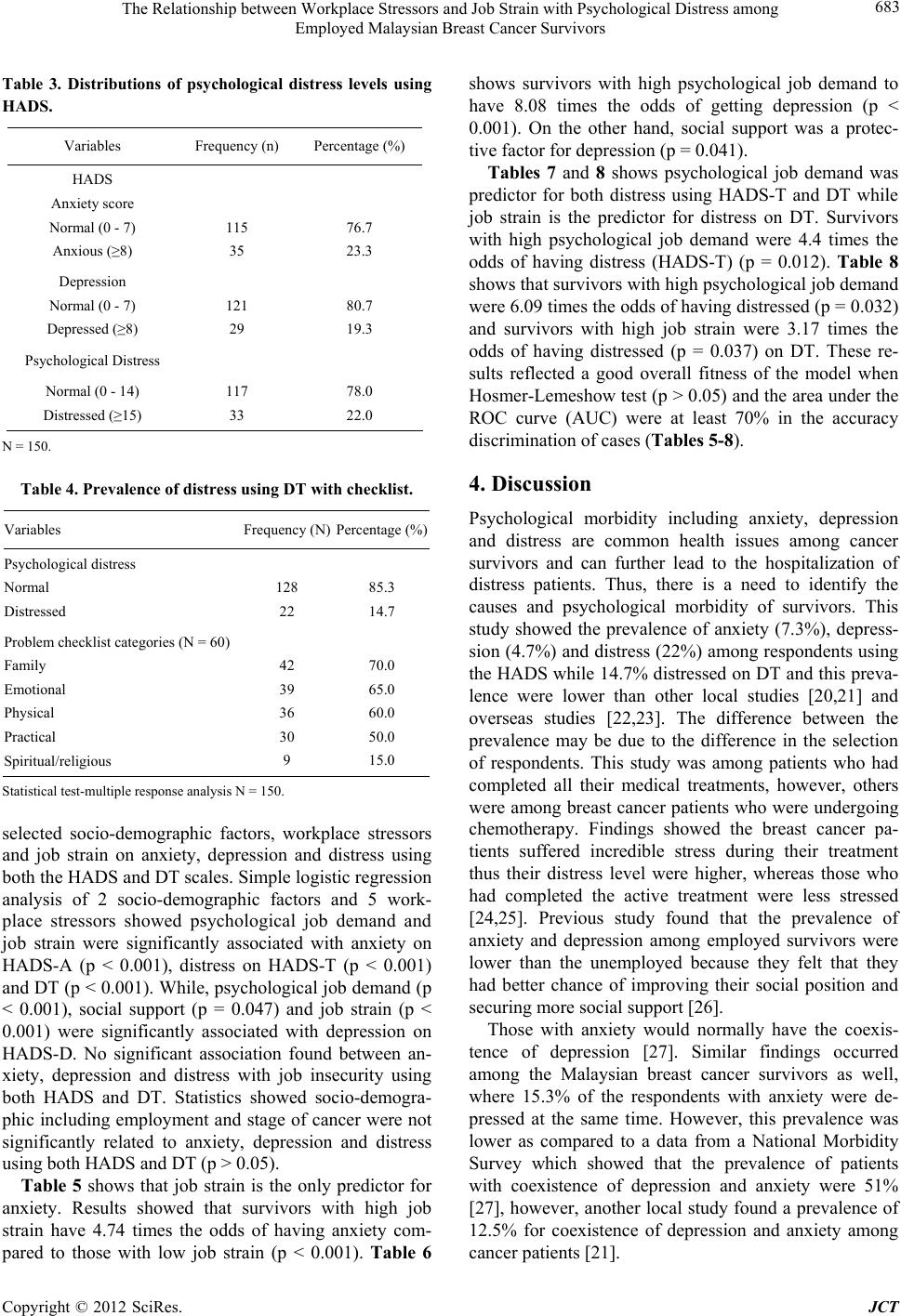

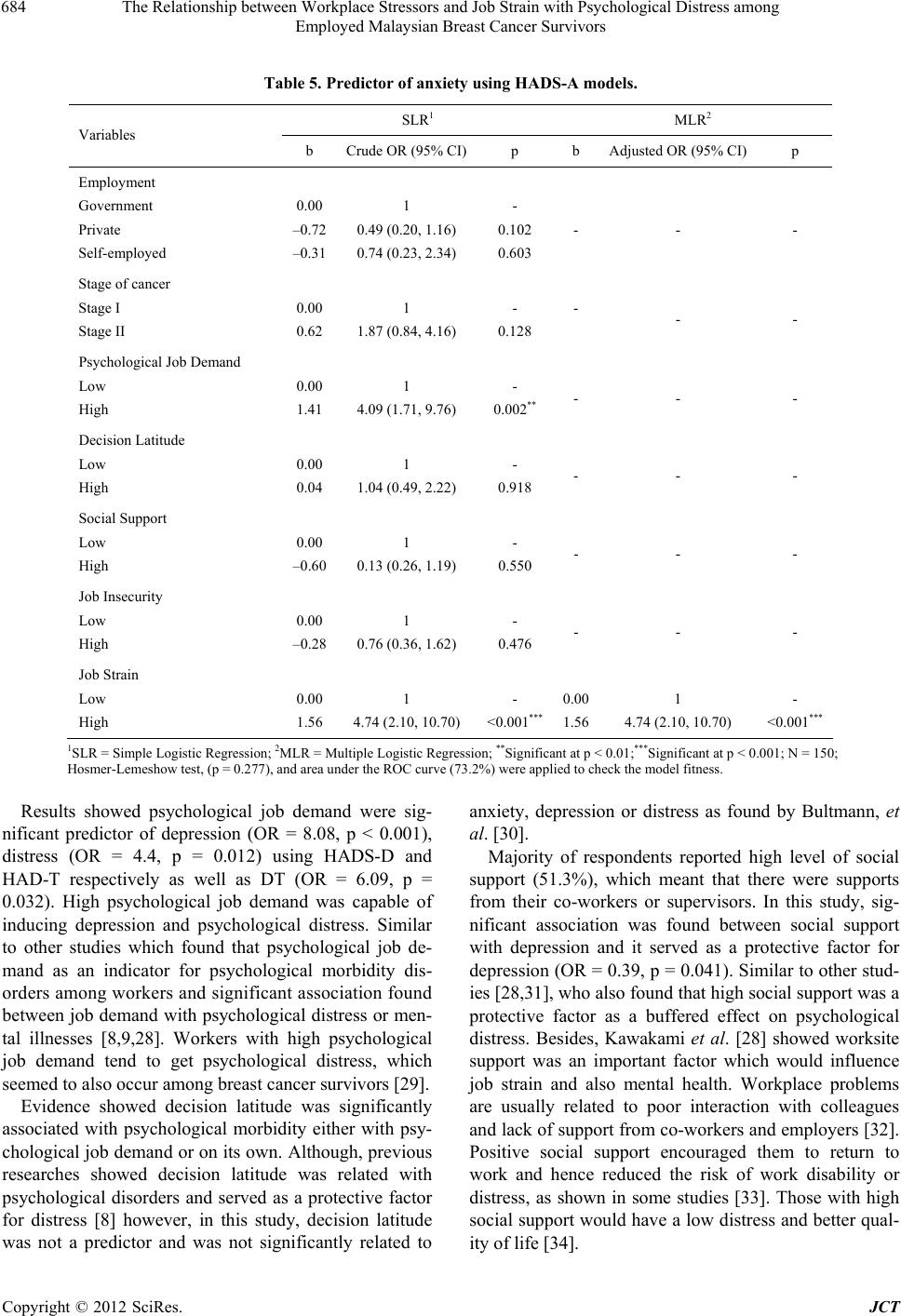

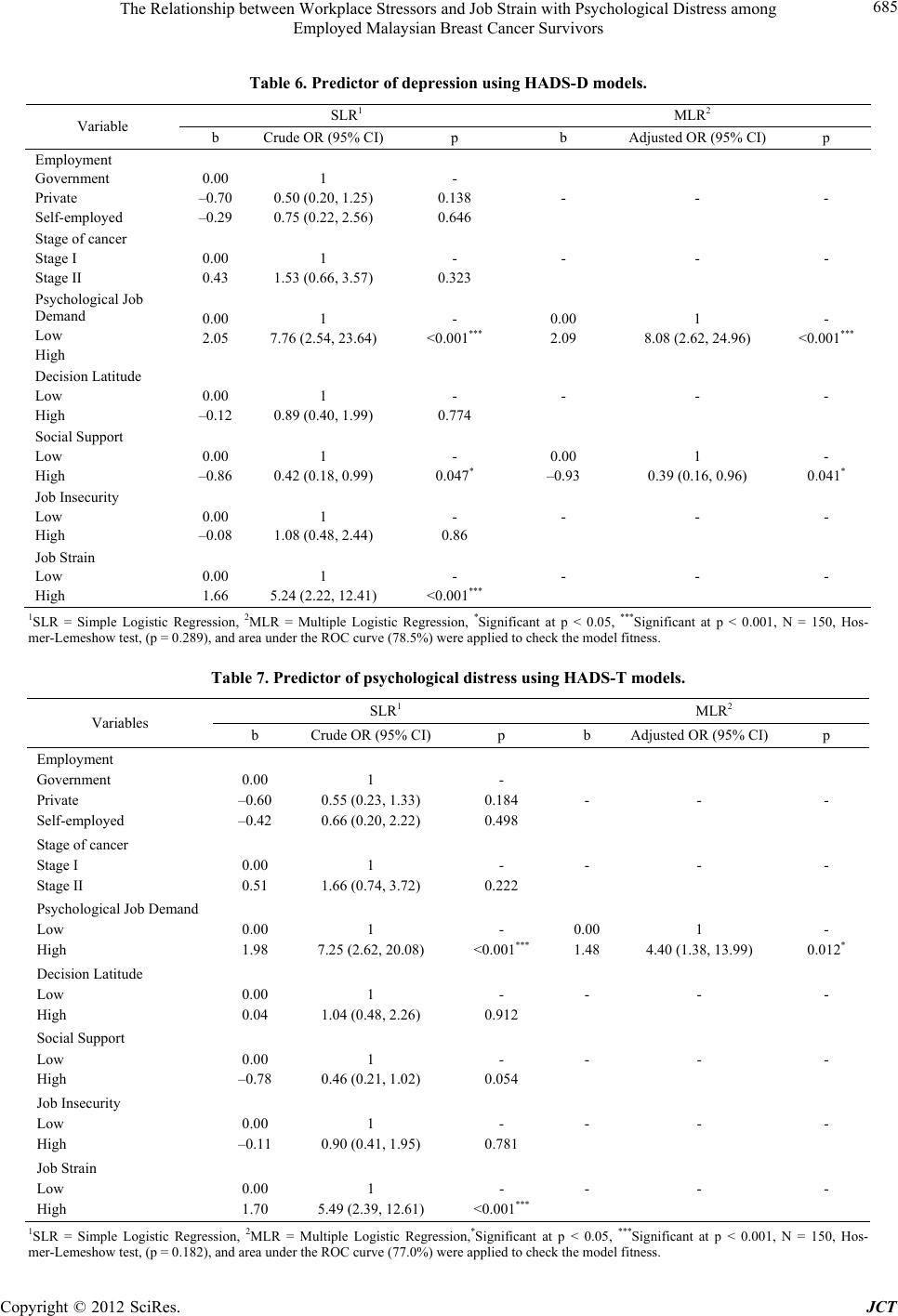

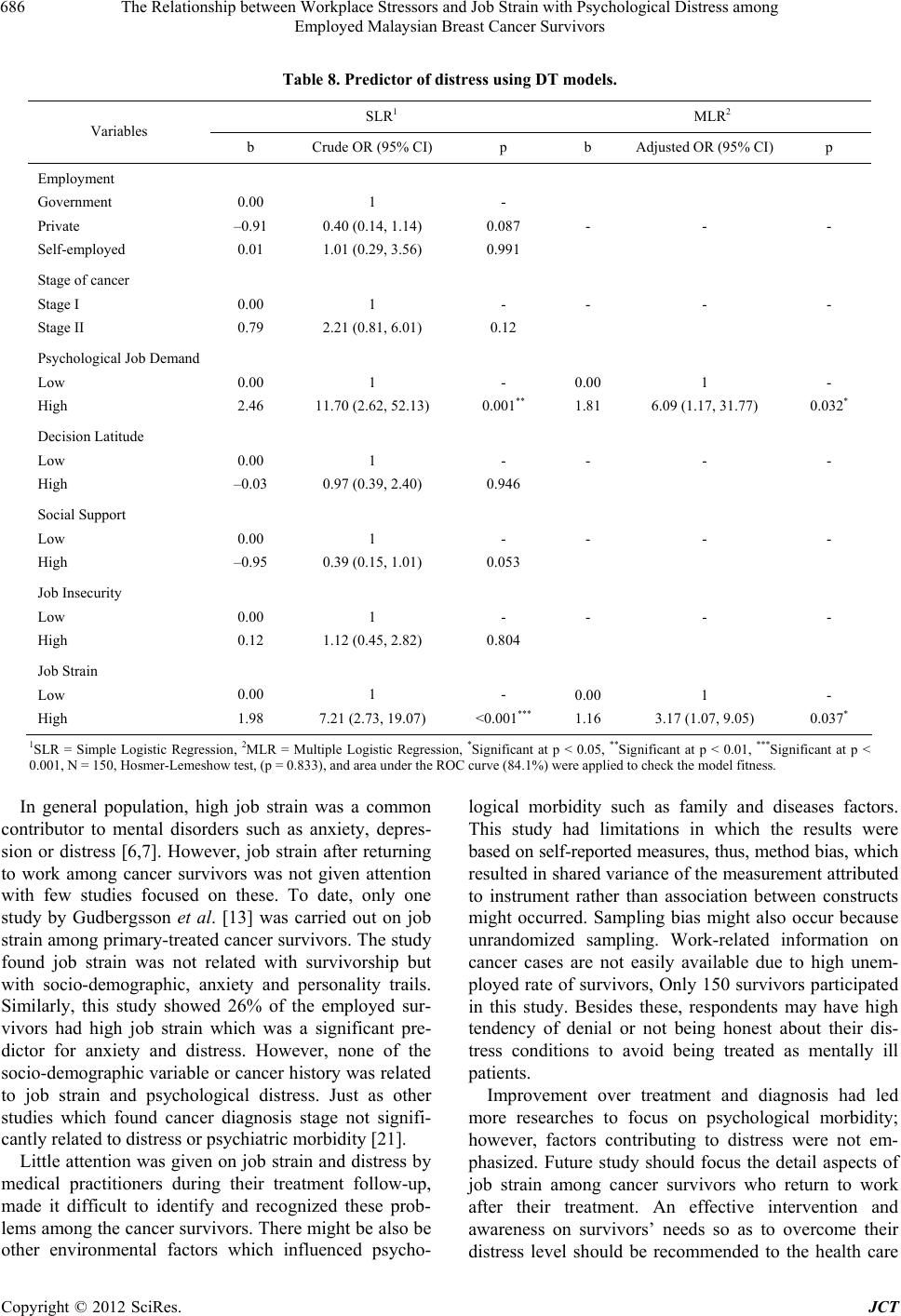

|