American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 2012, 2, 205-216 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2012.24027 Published Online October 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ajibm) 205 The Impact of Organisational Culture on the Implementation of TQM: Empirical Study in the Iranian Oil Company Yadollah Karimi1, Sharifah Latifah Syed Abdul Kadir2 1Faculty of Business & Accountancy, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 2Department of Operation and Management Information System, Faculty of Business & Accountancy, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Email: karimi13812002@yahoo.com, slhadad@um.edu.my Received June 16th, 2012; revised July 16th, 2012; accepted August 13th, 2012 ABSTRACT Purpose of this paper is to investigate the relationship between four construct of organizational culture and two type of TQM as soft and hard in the Iranian oil industry. The method of confirmatory factor analysis was applied to refine cul- ture and TQM scales for empirical analysis in Iranian Oil Industry. The structural equation modeling method was ap- plied to test the theoretical models. This study confirms the results of previous studies that considered culture as a set of practices. It confirms that not all types of culture—considered as a set of practices—has a positive impact on the TQM implementation. Only two components of culture—hierarchal and developmental showed a negative impact on the soft and hard TQM. The findings are useful for business managers in developing countries such as Iran, who want to en- hance business performance through implementing TQM practices in different culture. The study has contributed to develop a measurement system of TQM practices that facilitates more quality management research in developing countries. It has contributed to clarifying the disputed relationship between different culture and TQM practices, and shows empirical evidence in Iran industry to confirm that the culture set deployed by a firm has an impact on Soft and Hard TQM. Keywords: Soft TQM; Hard TQM; Organisational Culture; Oil Company; Iran 1. Introduction Over the past few decades, quality gurus such as [1-5] the primary authorities of total quality management (TQM), developed certain propositions in the field of TQM, which have gained significant acceptance through- out the world. Their insights provide a good understand- ing of the TQM philosophy, principles, and practices. After a careful study of their work, it has been found that these quality gurus have different views about TQM, although some similarities can be found. Worldwide, there are several Quality Awards such as the Deming Prize (1996) in Japan, the European Quality Award (EFQM), (1994) in Europe, and the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (1999) in the United States of America. Also many quality techniques and models such as ISO, Six sigmas, Just-In Time (JIT), are applied in organizations to reach a high level of performance. Award models and current managerial techniques are based on a perceived model of TQM. In the field of TQM implementation much research has already been conducted with different researchers adopting different definitions of TQM. However, the concept is still a sub- ject for debate [6] and still an unclear and hazy concept [7]. So far, TQM has come to mean different things to different people [8]. 2. Problem Statemen ts The Iranian Oil Industry is the biggest company in the Middle East and is also one of the key members in the oil company’s family around the world. This company has a central role in the country’s economy as a leading com- pany. It has instigated many helpful and useful activities in the area of quality management, developing produc- tions quality and economy development in recent dec- ades. Most of the oil companies and petro chemistry ones have the ISO standard and some others have won the prize of EFQM. Some committees have been established as suggestion systems to enhance the TQM processes with the most important goal being to the highest cus- tomers’ satisfaction. After several decades of these ac- tivities, the basic question is that of how successful the company in reaching its goals with quality pre-planned Copyright © 2012 SciRes. AJIBM  The Impact of Organisational Culture on the Implementation of TQM: Empirical Study in the Iranian Oil Company 206 schedules is. The results show that there has been no re- search done in this area. It will be considered an impor- tant goal of this research to answer this question so that it takes a useful step in eliminating weaknesses and short- comings of such problems. Study is needed to see the impact of TQM on quality level, Improvement of pro- duction quality and also oil industry performance espe- cially in terms of operational performance. Moreover, several gaps have been found by reviewing and studying the work of others, which will be talked about briefly. In the TQM field, two types of researches are common; researchers only focusing on organizational culture and its effect on conducting TQM [9] and second various other researchers simply focus on the relationship be- tween TQM and organizational performance [10-13]. So in this study, by making a new model and mixing previous models, TQM has been looked as a mediator, and also it will examine the effect of organizational cul- ture on performance. By developing this model the rela- tionship between Soft and Hard TQM can also be studied, as the mutual relationship between Hard and Soft has not yet been explored [14]. In this research, for the first time, the relationship between these two sets will be taken into account. In addition, by analyzing and studying previous studies, it is seen is that most research in the TQM field is conducted in the US, Europe and Australia, and, gen- erally speaking, in developed countries. Many small studies in TQM have been done in devel- oping countries and especially in the Middle East, and in the context of Iran. Lastly, as a critical issue, total quality management was created some time ago and its concept is very broad. So a lack of in TQM literature particularly in association with culture is still problematic, because results in TQM implementation are slightly different from culture to culture. This may lead to the success or failure of TQM and, consequently, will affect perform- ance. For instance, [15,16] claimed that when TQM is implemented in places that do not contribute to its cul- tural base, differences with the cultural context will support it. This may lead to the success or failure of TQM. 3. Organizational Culture The term “organizational culture” has proved extremely popular with management theorist and managers alike since the publication of In Search of Excellence [17] (Pe- ters and Waterman, 1982). The term “culture” has its theoretical roots within social anthropology and was first used in a holistic way to describe the qualities of a hu- man group that are passed from one generation to the next. [18] described culture when taken in its wide eth- nographic sense, as that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law and man as a member of society. Anthropological understanding of organizational cul- ture is something that results from the interaction and is generated at all levels of the organization suggesting that while managers can influence culture, they cannot actu- ally create or direct it because the generation of organ- izational culture is, by nature, not restricted to the do- main of management. If culture is created on an ongoing basis throughout an organization, then managers lack the total control of the interactive and interpretive processes that would be necessary at all levels of the organization to consciously create and direct an organization’s culture. An anthropological perspective on organizational culture, with its focus on interpretive processes, suggests that managers face difficulty in explicit attempts to change organizational culture because they cannot completely control the complex interactions that produce culture throughout an organization. Organizational culture can influence how people set personal and professional goals, perform tasks and ad- minister resources to achieve them. Organizational cul- ture affects the way in which people consciously and subconsciously is think, make decisions and ultimately the way in which they perceive, feel and act [19,20]. [17,21] have suggested that organizational culture can exert considerable influence in organizations, particularly in areas such as performance and commitment. Researchers on organizational culture have also pro- posed different forms or types of culture. For example, [22] identified four forms of organizational culture (i.e. networked, mercenary, fragmented and communal). [23] viewed organizational culture from three perspectives (i.e. integration, differentiation and fragmentation). [24] sug- gested that there are three main types of organizational culture (i.e. bureaucratic, supportive and innovative). Or- ganizational culture affects the way the employees think, perform and communicate with each other and has been regarded as one of the most influential aspects in an or- ganization. Nevertheless [25] described organizational culture as the way things are done the business. Other definitions state the shared perceptions, patterns of belief, symbols, rites and rituals and myths that evolve over time and function as the glue that keeps the organization together [26]. According to these definitions, it is very clear that the existing culture of an organization provides a cor- porate framework that will lead in guidance on issues such as how work is done, the use of technology, how people think and standards for interaction and commu- nication. A deep understanding on these aspects will result in better communication and interaction among the people outside and inside the organization which may lead its positive progress. These, in turn, affect an individual’s performance and then affect a firm’s per- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. AJIBM  The Impact of Organisational Culture on the Implementation of TQM: Empirical Study in the Iranian Oil Company Copyright © 2012 SciRes. AJIBM 207 framework is able to organize the different patterns of shared values and assumptions that define an organiza- tion’s culture [40]. formance. Previous studies have shown that organizational cul- ture (and various subcultures within the organization) can have a positive effect on competitive advantage, in- creased productivity and a firm’s performance [27]. On the level of the individual, they found organizational culture could affect an employee’s participation and in- volvement. This is important as employees play a major role in constructing an organization. Organizational cul- ture is ultimately manifested, represented and main- tained by sense-making efforts and actions of individu- als [28]. Emphasis should be made on the organiza- tional culture as it has an impact on the firm’s per- formance or productivity. Meanwhile, the organiza- tional culture impacts individuals first, which in turn affects a firm’s overall performance, productivity or com- petitive advantage. The competing values model is characterized by a two-dimensional space that reflects different value ori- entations (see Figure 1).The first dimension in this model, the flexibility-control axis, shows the degree to which the organization emphasizes change or stability. A flexibility orientation reflects flexibility and spontaneity, while a control orientation reflects stability, control, and order. The second dimension in this framework, the in- ternal-external axis, addresses the organization’s choice between focusing on activities occurring within the or- ganization (internal) and those occurring outside, in the external environment. An internal orientation reflects an emphasis on the maintenance and improvement of the existing organization, while an external orientation re- flects an emphasis on competition, adaptation, and inter- action with the external environment. Moreover, many studies have proven how organiza- tional culture or changes in organizational culture can facilitate or hinder business change initiatives such as OP, ERP and TQM [29-34]. Thus, in this study, investigation will be made on how; an organization’s culture influ- ences the business performance when using TQM to im- prove activities. This two-dimensional typology yields four cultural orientations that correspond to four major models in or- ganizational theory. Group culture, which corresponds to the human relations model of organizational theory, em- phasizes flexibility and change and is further character- ized by strong human relations, affiliation, and a focus on the internal organization. Developmental culture, corre- sponding to the open systems model, also emphasizes flexibility but is externally oriented. The center of atten- tion is primarily on growth, resource acquisition, creativ- ity, and adaptation to the external environment. Continu- ing with this model, rational culture, corresponding to the rational goal model, is also externally focused, but it is control-oriented. Such firms emphasize productivity and achievement, with objectives typically well-defined and external competition a primary motivating factor. Competing Value Framework For the purpose of describing the values and beliefs un- derlying an organization’s culture, the Competing Values Framework (CVF) developed by [35] is adopted. It has been widely used to examine organizational culture in the literature [26,36-38]. According to [39] the value orientations in the CVF can be used to explore the deep structures of organizational culture about compliance, motives, leadership, decision making, effectiveness, and organizational forms in the organization. Thus, this Control Internal Externa DEVELOPMENT L RATIONAL GROUP HI Uniqueness Risk-taking Innovation Leadership Entrepreneurship Security Formal rules Control and structure Stability Internal efficiency Coordination Achievement Market leadership Competitiveness Goal accomplishment Results-oriented Aggressiveness Human development Commitment Personal relations Teamwork Loyalty Mentoring Flexibility Figure 1. CVF framework (adapted from Denison and Spreitzer, 1991; Cameron and Quinn, 1999).  The Impact of Organisational Culture on the Implementation of TQM: Empirical Study in the Iranian Oil Company 208 Hierarchical culture, corresponding to the internal pro- cess model, emphasizes stability. However, in contrast to rational culture, the focus is on the internal organization. This orientation is characterized by uniformity, coordina- tion, internal efficiency, and a close adherence to rules and regulations. These cultural orientations have also been referred to as Clan, Adhocracy, Market, and Hier- archy, respectively [41]. Figure 1, which was adapted from prior work by [36,41], provides an illustration of how these idealized orientations fit within the two-di- mensional competing values framework. In each of the four quadrants shown in above figure a representative (although not exhaustive) list of character- istics associated with each cultural orientation are pro- vided. [36] emphasis that the four cultures in their typol- ogy should be viewed as ideal types, meaning that or- ganizations will be characterized by some arrangement of these four cultures—while some types could be more principal than the others—rather than reflecting only one culture. Therefore, as scales have been developed and vali- dated to empirically measure this, the items are permitted to vary separately [40]. As [42] noted in a later study using the CVF, “As such, a high rating on one dimension (e.g. internal orientation) does not eliminate high rating at the other end (e.g. external orientation)”. There is nothing relating to having a strong internal orientation that necessarily prohibits the organization from also having elements associated with external orientation. This model of organizational culture has been employed in quality management research by many researchers [31,43]. In order to clarify understand provide a better understanding of the relationships between organiza- tional culture and performance measurement systems developed for top management teams, [26] found that that top managers of firms reflecting a flexibility domi- nant type tend to use more performance measures and to use best strategy to focus organizational attention, sup- port strategic decision-making and legitimate actions to a greater extent than top managers of firms reflecting a control dominant type. 4. Total Quality Management The TQM literature concurs that its concepts and prac- tices have been shaped by a number of individuals who are recognized as “quality gurus” such as [1-4,20, 32,36,44]. Their definitions are the foundation for under- standing the concept of TQM. These TQM gurus devel- oped their concepts based primarily on their experience in industry. TQM was made famous by Deming in the 1950s in Japan. His suggestion was based on 14 princi- ples that placed emphasis on leadership, management theory, and statistical concepts. These principles stressed the importance that managers had in the process of im- proving organizational performance while enhancing the capabilities of the employees. Therefore, a number of factors need to be taken into account. These include the establishment of the “con- stancy of purpose” in the mission of an organization; As [2] has reminded us of, commitment and support from top organizational leadership; building and enhancing trust, motivation, and serious employee empowerment through genuine participation, job security, and equitable compensation; team works of various structures; training and development of employees and workers; measure- ments of quality through process as well as outcomes; building a “culture of quality” in the organization and rewarding that culture with recognition, respect, and various personnel policies to reinforce that culture and promote both employee and citizen/customer satisfaction and confidence. As there have been many different defi- nitions of TQM the years here are some examples. [45] states that TQM is an approach for improving the com- petitiveness, effectiveness and flexibility of a whole or- ganization. He continues by declaring that: “For an organization to be truly effective, each part of it must work properly to- gether towards the same goals, recognizing that each person and each activity affects and in turn is affected by each other’s. The methods and techniques used in TQM can be applied throughout any organization”. [46] argue that Total Quality Management (TQM) is an evolving system of practices, tools, and training methods for managing companies to provide customer satisfaction in a rapidly changing world. The use of the word “total” when coupled with the term “quality management” pro- vide recognition of the fact that total quality management (TQM) is not an activity or even a philosophy that can be restricted to certain organizational processes. It is essen- tial that TQM is adopted on a holistic basis, if genuine and lasting competitive advantage is to be gained. As [47] has stated; “TQM is the mutual co-operation of everyone in an organization and associated business processes to produce products and services which meet and, hopefully, exceed the needs and expectations of customers. TQM is both a philosophy and a set of guid- ing principles for managing an organization”. [47] Simi- larly [48] define TQM as a management system in con- tinuous change and consisting of values, methodologies and tools, the aim of which is to increase external and internal customer satisfaction with a reduced amount of resources. 5. Relationship between Culture and Total Quality Management Understanding culture as something implicit and gener- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. AJIBM  The Impact of Organisational Culture on the Implementation of TQM: Empirical Study in the Iranian Oil Company 209 ated from interaction at all levels of an organization raises the question as to whether it is advisable for man- agers to enter into quality improvement programmes such as TQM with the expectation that these programmes will result in a positive change in an organization’s cul- ture [49]. There is little support for the idea that TQM influences organizations at deeper levels of culture [49]. If culture is implicit and generated from interaction at all levels of the organization, then managers would benefit more from the careful consideration of cultural factors that are already operating when a quality improvement programme is implemented. Paying more attention to the cultural process of the organization, managers might better understand the in- fluence of these cultural factors, and as a result, will have better success in quality improvement efforts. Rather than assume that the implementation of a quality im- provement strategy such as outcome accountability will result in cultural change towards greater utilization of outcome information in decision making, it would be wiser to focus on the receptiveness of the existing organ- izational culture to such a strategy. Implementation of TQM programmes varies considerably according to the culture of the organizations in which it is being imple- mented [50]. This is consistent with the view that it is not so much management action that determines culture, but rather it is culture that determines management action [49]. [51] recommends that organizational culture is even more important today than it was in the past. Increased competition, globalization, mergers, acquisitions, alli- ances, and various workforce developments have created a greater need for improving efficiency, quality, and speed of designing, manufacturing, and delivering prod- ucts and services, process innovation and the ability to successfully introduce new technologies, such as infor- mation technology , facilitation and support of teamwork. Therefore, focusing on culture in organizations is one of the basic fields in academic research. According to lot of earlier research, it was discovered that organizational culture is an important aspect in the successful implementation of TQM [31,52,53] and in particular, within the context of organizational perform- ance [54]. In addition, other recent studies have exam- ined the relationship between organizational culture and the TQM tools and techniques as per the differentiate approach [55,56]. A common challenge in discussing TQM and culture results from the imperfect boundary between TQM as a set of management practices and TQM as an organizational culture [57-59]. For example, several studies on TQM, such as those by [60,61] con- sider TQM practices such as customer focus and people management as “soft” elements in TQM, implying that they actually represent aspects of TQM culture. This leads to confusion in understanding the substance of TQM: Is it a set of practices, or, is it a specific type of culture, or both? In this regard, [62] strongly argue that organizational culture is “distinguishable” from TQM practices even though the two are closely related to each other. They view TQM practices as behavioural, while organizational culture is more attribute to attitudes, be- liefs, and situational interactions. This argument is con- sistent with those of theorists and scholars in the field of organizational culture. [63] for example, asserts that al- though practice can be a reflection of organizational cul- ture, it can only capture the surface level. He further ar- gues that organizational culture is concerned with some- thing deeper, particularly when considering such ele- ments as mindset, values, and beliefs. This is consistent with definitions of culture as being something an organization has. It is also asking for a change in attitudes and values that lie at the deeper levels, although it is less specific about what these are. It is im- plied that implementing the “hard” aspects of TQM will lead to changes in the deeper levels of organizational culture, and that this interaction produces a number of individual and organizational outcomes [49]. Although it is true that cultures change, it does not necessarily mean that management has the responsibility to do so. The extent to which factors of the TQM interventions typi- cally affect culture, and at what levels, has yet to be em- pirically investigated. In this way, [49] argued that, an understanding of the different levels of culture may assist those managing organizations to identify those aspects of culture that are open to managerial influence. An alterna- tive view is that rather than being affected by quality management practices, it is the culture of the organiza- tion that determines how the nebulous message “that is quality” will be interpreted and enacted. To the extent that the organization is characterized by a series of subcultures, a number of interpretations will be made. Organizations thus define and manage quality from the perspective of existing patterns of shared beliefs, values and assumptions. This view is consistent with definitions of culture as being something an organization is. In this way, [64] argued that, the management of qual- ity does not take place outside cultural influences, but needs to be understood within the context of prevailing shared values, beliefs and taken-for-granted assumptions. This point is made in relation to the management of stra- tegic change. He argues that the interpretation of the various signals the organization faces, and the formulation of actions and responses to those interpretations, is configured within the bounds of the collective values, beliefs and assump- tions held by senior management. Continually, [65] stated that quality as an organizational truth is the out- standing emotive force which can unify everyone within Copyright © 2012 SciRes. AJIBM  The Impact of Organisational Culture on the Implementation of TQM: Empirical Study in the Iranian Oil Company 210 the organization. There is an emphasis on the achieve- ment of common objectives and conflict that is seen as inherently dysfunctional. Management is positioned as a technical and rational process, and the organizational political issues need to be more discussed [66]. The adoption of an “integrationist” perspective to culture pre- cludes consideration of alternative approaches. The “differentiation” and “fragmentation” perspectives (which emphasize the existence of subcultures and of ambiguity respectively), present a significant challenge for TQM theorists. According to [49], while offering insights into cultural change that are not available to those working exclusively from an “integrationist” per- spective, it seems unlikely that TQM in its present form will be able to accommodate them. Given the importance of culture change to TQM, this represents a significant handicap. Further support can be obtained from a study by [10] which promotes the importance of cultural as- pects of TQM. In this study, he discussed that TQM practices had to be implemented within a suitable environment (i.e. cul- ture) that emphasized open communication; something which he believed did not originally belong to TQM, but was essential for its successful implementation. Although the success of TQM programmes has been highlighted by a number of authors [31,52]. It has also been argued that TQM implementation leads to changes in organizational culture. Understanding the dominant culture of an or- ganization is of the utmost importance for the successful implementation of TQM. Environmental changes pro- duce different emphasis within an organization, thus, new approaches for implementation of TQM is very much needed [40,52,63]. In recent years, many authors have tried to explain how organizational culture influences TQM implementa- tion and business performance and its degree success. For instance, [67] conducted a survey of Malaysian ma- nufacturing companies that was already ISO 9000 regis- tered, with a view to examine their status regarding busi- ness performance. The results showed that less than a third of the responding companies claimed to have TQM, but there was a strong minority claiming to have made significant progress towards total quality practices. [68] made a statement on a comparative action-research study of quality management in Malaysia and the UK. They commented particularly on the cultural conflict between traditional Malaysian managers who “are locked into traditional autocratic management styles” and expatriate senior managers, particularly from Japan. Like many countries in South and East Asia, the Malaysian compa- nies studied here perceived TQM techniques as the final goal (Malaysia has many more companies that are ISO 9000 registered). However, there was evidence that Ma- laysian companies made more systematic use of quanti- tative quality management tools to control key processes than the UK companies did [68]. In addition, the Malay- sian companies were assessed by these authors, using an opinion poll, to be more focused on strategic quality ori- entation and continuous improvement. In a similar study [54] studied TQM practices in United Arab Emirates (UAE) manufacturing firms and their impact on quality and business performance. They investigated the relationship between firm culture and TQM implementation. According to this research, busi- ness culture can be divided in to two categories, the first group includes people oriented and competitiveness, while the second one includes outward oriented, inward oriented, task oriented, and competitiveness. It was con- cluded that cultures that are people oriented, and to a lesser degree, competitive, are less common among UAE manufacturing firms. This may be to do with the fact that most respondents were from East Asian countries where national cultures are characterized by large power dis- tance and high uncertainty avoidance [25]. We believe that it would have been better if they had used the Hofstede model since the characteristics of the research area were much closer to that of a multinational company. National culture can prove to be quite stubborn, obstinate and conservative, presenting multinationals, joint ven- tures, consortiums and subsidiaries with formidable ob- stacles to organizational change [69]. In Iran, [70] employed the Hofstede model to deter- mine the force of cultural values on the achievement of TQM performance in the Isfahan University Hospital (IUH). He found that TQM fundamentally requires a new culture. The best TQM results can be achieved when an open, shared and cooperative culture is created by man- agement and supported by organizational learning, team- work, and customer focus (internal/external). Successful implementation of TQM requires a significant change in values, attitudes and the culture of the organization. Tata and Prasad (1998) studied the TQM field to determine why many companies in the USA were not successful in the implementation of TQM. By comparing three com- panies they found that companies that already have a supportive culture and structure made it easier to imple- ment employee involvement, teamwork, benchmarking, customer focus and other aspects of TQM. These organizations first resocialized employees and management to the values and beliefs of a flexible cul- ture and organic structure. In contrast, other companies that lead in control oriented culture and mechanistic structure did not succeed in the implementation of TQM. [71] used this model to find out which dimension was more related to TQM factors. The result showed that a hierarchal culture has a significant relationship with cer- tain factors of TQM. A multicultural environment is a common issue in Copyright © 2012 SciRes. AJIBM  The Impact of Organisational Culture on the Implementation of TQM: Empirical Study in the Iranian Oil Company 211 many companies around the world. [72] shed light on quality management issues regarding the maquiladora’s industry in Mexico. Their study presented evidence of a straight quality system in the maquiladoras based on TQM and strategy planning principles, utilizing the teamwork approach to problem solving, providing train- ing to employees, working with suppliers and striving for quality certifications. In other words, by establishing quality systems, implementing quality principles and techniques and training managers and employees in qual- ity problems, the maquiladoras are playing a significant role in building a quality culture in Mexico’s industry. Also, the result showed that quality culture could be in- strumental in transforming industry into a global power recognized for its world-class manufacturing and excel- lence in quality. In a similar study [14] focused on this area to explore the relationship between the culture (organizational citi- zenship behaviour (OCB)), TQM practice and financial performance of the manquiladora companies. Based on the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (MBNQA, 1995), they selected Soft TQM factors (leadership, peo- ple management, customer focus), and Hard TQM ele- ments (planning, process management, information) as mediator variables. They found that only Soft TQM ele- ments are significantly related to organizational per- formance. As a result and according to [71] it can be concluded that the cultures supporting TQM practices (i.e. group and developmental cultures) are the best and there- fore should be nurtured. At the same time, should hierarchal factors, which underlie TQM3, be suppressed? If so under what conditions? In this research the impact of these factors of organizational culture is will tested to clarify how they are related to TQM and organizational performance. 6. Research Hypotheses Having discussed the nature of the relationship between TQM practices and organizational culture, the following question is explored: what kind of culture would be most suitable for implementing TQM practices in the oil in- dustry? As mentioned earlier this research focus on the computing values framework (CVF), developed by [36] to answer this main question. Studies by [71] have shown that hierarchal and developed culture has a significant impact on TQM. Therefore, the following hypotheses are suggested. H1: Hierarchical culture has a positive impact on Soft TQM. H2: Hierarchical culture has a positive impact on Hard TQM. H3: Developmental culture has positive impact on Soft TQM. H4: Developmental culture has a positive impact on Hard TQM. H5: Rational culture has a positive impact on Soft TQM. H6: Rational culture has a positive impact on Hard TQM. H7: Group culture has a positive impact on Soft TQM. H8: Group culture has a positive impact on Hard TQM. 7. Research Design The National Iranian Oil Company is divided into four main companies: Gas Company, Petrochemical Com- pany, Oil Company, and Refinery & Distribution Com- pany. In this research, a questionnaire will be the method chosen to collect data from the different Companies and departments. There are several reasons for selecting a questionnaire survey in this part. First many respondents work in different geographical statues, and are located in different operational places. Besides, using a question- naire survey allows greater efficiency in collecting data in a rather short period of time and provides the re- searcher a high flexibility to do different kinds of analy- sis based on the data collected. Furthermore, sending questionnaires to the target group is a comparatively a cheaper than reaching the target group one by one as their offices may be located in different places which a resulting in high transportation costs. 8. Data Collection Procedure In the Iranian oil industry many specialist groups work in different units and departments and are involved with quality techniques. In addition, this industry has four main mother companies and a lot of subsidiary compa- nies throughout the country. However, the population of this study will include all employees who are employed in various organizations that are using quality techniques, and have also received ISO certification. Different members of the company will be invited to complete the questionnaire and not just senior managers or directors because different working categories may have a differ- ent opinion of the values of the company. In order to understand the cultural profile and TQM level of a com- pany in a more comprehensive way, data will be col- lected from different locations. Ultimately, 400 managers and other levels of employees are drawn randomly as a final sample from the list of directories using the strati- fied method. 9. Questionnaire Survey In the area of TQM implementation and organizational culture, much research has conducted using questionnaire surveys to collect data [11,15,43,61]. These researchers Copyright © 2012 SciRes. AJIBM  The Impact of Organisational Culture on the Implementation of TQM: Empirical Study in the Iranian Oil Company Copyright © 2012 SciRes. AJIBM 212 tested the effects of TQM implementation on overall business performance using questionnaire surveys. In this study, the questionnaire survey will be used to obtain information about organizational culture, TQM imple- mentation and operational performance. All dimensions will measure by items asking the respondent to assess the level of implementation of each of the factors. These items are derived from prior literature. In addition, before distributing the questionnaire its layout, content, and structure will be tested (validity) through conducting a pilot study of proficient membership companies who are employed in the quality sectors to ensure the accuracy of terminology, content, structure and common understand- ing. 10. Statistical Technique This study employs a structural equation modeling (SEM) as the statistical technique to analyze the hypothesized relationships. All other multivariate techniques are either from a family of dependence or independence statistical techniques. Only SEM has the characteristics of both groups because the foundations of SEM are derived from multiple regression analysis (dependence technique) and factor analysis (independence technique) [73]. What makes SEM a more powerful and popular than other multivariate techniques is that, besides having an attrac- tive graphical modeling interface that makes model in- terpretation an easy task [74] SEM can examine a chain of dependence relationship concurrently. As asserted by [73] “None of the previous techniques except SEM en- able us to assess both measurement properties and test the key theoretical relationships in one technique”. SEM reveals the structure of interrelationships among the studied variables by using a series of equations similar to multiple regression technique and by modeling interac- tions, nonlinearities, correlated independents, measure- ment errors, correlated error terms, and multiple latent independents/dependents all at the same time [74]. 11. Result of Testing Ypotheses In this study eight hypotheses were examined through investigating the path coefficients and the total size effect of the constructs in the final model. Based on the C.R (t), to explain which hypothesis was statistically supported, results of hypotheses testing are summarized and pre- sented in Table s 1. Based on the result in Table 1, it can be concluded that Hierarchical Culture is statistically correlated only to hard TQM, because the paths coefficient of hierarchical culture to hard TQM is 0.11 (t = 8.424), and to soft TQM is 0.01 (t = 0.48), meaning that hierarchical culture has weak positive effect on hard TQM, but it does not pro- vide a significant effect on soft TQM. The third hypothesis states that the developmental culture has a meaningful effect on soft TQM. According to the output model, the path coefficient is 0.39 (t = 17.188). Thus, the hypothesis supported the developed culture, which has a meaningful effect on soft TQM. On the other hand, the path coefficient between this variable and hard TQM is very weak, with a value of 0.009 (t = 0.272), thus, there is no significant relationship between developmental culture and hard TQM, making H4 un- substantiated. According to the analyzing model, the group culture has the significant relationship between both soft and hard TQM. The paths coefficient of this variable to soft and hard TQM is 0.39 and 0.14, and the t-values are 16.289 and 4.470 respectively. Therefore, hypothesis H5 and H6 is supported, and group culture has a meaningful effect of showing the changes in both the soft and hard variance, and it is one of the reasons for forming soft and hard aspects in the company. With a Path coefficient value of 0.21, the relationship between rational culture and soft TQM is considered to Table 1. t-value, significant indexes, and regression weights of path analysis. Exogenous Endogenous Estimate S.E. C.R.(t) P St.value Result of hypothesis H1 Hierarchical → Soft TQM 0.008 0.011 0.695 0.487 0.009 Not supported H2 Hierarchical → Hard TQM 0.098 0.012 80.424 *** 0.114 Supported H3 Development → Soft TQM 0.389 0.023 170.188 *** 0.395 Supported H4 Development → Hard TQM 0.008 0.030 0.272 0.785 0.009 Not supported H5 Group → Soft TQM 0.401 0.025 16.289 *** 0.392 Supported H6 Group → Hard TQM 0.145 0.032 4.470 *** 0.144 Supported H7 Rational → Soft TQM 0.219 0.022 9.976 *** 0.217 Supported H8 Rational Hard TQM 0.392 0.026 15.317 *** 0.394 Supported  The Impact of Organisational Culture on the Implementation of TQM: Empirical Study in the Iranian Oil Company 213 Hairachial Developmental Rational Group Soft TQM Hard TQM 0.22 0.01 0.01 0.14 0.11 0.39 0. 3 9 0.39 Figure 2. Path diagram. be significant (t-value = 9.976). Likewise, the link be- tween rational culture and hard TQM shown in Table 1 has generated a path coefficient value of 0.39 (t-value = 15.317). This means that rational culture can positively affect both soft and hard TQM, supporting hypothesis H7 and H8. 12. Conclusions The results indicate that there is no relationship between “hierarchal developmental Culture” with “soft and Hard TQM”. The findings of previous researchers [71,75] prove that two dimensions of “Group” and “Develop- mental” support TQM. Yet, due to cultural difference and organizational atmosphere in this research, almost all factors of organizational culture have relationship with TQM, except “hierarchal” and “Developmental” cultures that were not effective on “tow aspects of TQM”. In ad- dition, the rational culture and group culture are found to have a significant effect on both soft and hard TQM practices (Figure 2). The rational culture emphasizes productivity and achievement with clearly defined objectives for external competitiveness. Efficiency and profit orientation are conducive to the TQM practices that focus on achieving superior quality and competitiveness [21]. Understanding customer and developing close relationships with them are keys strategies for gaining the competitive advantage that is so ingrained in the rational culture. Gathering and using quality information can also provide the strategic advantage in the external markets that are the focus within a rational culture. This result is similar to research finding done by [75]. Considering the fact that organizational culture is recog- nized as a key and vital agent for the implementation of comprehensive quality management [10,32,52] it was necessary to scrutinize the relationship between different kinds of organizational culture based on CVF model with TQM, and also study the organizational performance in one of the biggest Middle East oil companies (Iran oil industry) with one hundred years experience. This re- search has important practical findings for the managers. Based on the disclosed results, different cultural compo- nents such as, group culture, developmental culture, hi- erarchical culture and rational one have practically had different impacts with other different TQM, namely Hard TQM and Soft TQM. This means that before the imple- mentation of instructions and TQM instruments, the managers require knowing the dominant cultural values on their own organizations very well, so that the imple- mentation of TQM can be done more effectively. Man- agers should carefully evaluate the values and current cultural fields to develop the practical plans and neces- sary policies for the creation of an environment and cul- tural atmosphere of the sponsor, so that they can be sure about the successful implementation of TQM and im- provement of organizational performance. In summary, the first aim of this research is recogni- tion of cultural distinctions in Iran oil industry and the way TQM gets influenced from organizational culture. The findings of previous researchers [71,75] prove that two dimensions of “Group” and “Developmental” sup- port TQM. Yet, due to cultural difference and organiza- tional atmosphere in this research, almost all factors of organizational culture have relationship with TQM, ex- cept “hierarchal” and “Developmental” cultures that were not effective on tow aspects of TQM. The results indicate that there is no relationship between “hierarchal and de- velopmental Culture” with “soft and Hard TQM”. In addition, the rational culture and group culture are found to have a significant effect on both soft and hard TQM practices. The rational culture emphasizes produc- tivity and achievement with clearly defined objectives for external competitiveness. Efficiency and profit orienta- tion are conducive to the TQM practices that focus on achieving superior quality and competitiveness [7]. Un- derstanding customer and developing close relationships with them are keys strategies for gaining the competitive advantage that is so ingrained in the rational culture. Gathering and using quality information can also provide the strategic advantage in the external markets that are the focus within a rational culture. This result is similar to research finding done by [75]. Considering the fact that organizational culture is recognized as a key and vital agent for the implementation of comprehensive quality management [10,32,52] it was necessary to scru- tinize the relationship between different kinds of organ- izational culture based on CVF model with TQM, and also study the organizational performance in one of the biggest Middle East oil companies (Iran oil industry) with one hundred years experience. This research has important practical findings for the managers. Based on the disclosed results, different cul- tural components such as, group culture, developmental Copyright © 2012 SciRes. AJIBM  The Impact of Organisational Culture on the Implementation of TQM: Empirical Study in the Iranian Oil Company 214 culture, hierarchical culture and rational one have practi- cally had different impacts with other different TQM, namely Hard TQM and Soft TQM. This means that be- fore the implementation of instructions and TQM in- struments, the managers require knowing the dominant cultural values on their own organizations very well, so that the implementation of TQM can be done more effec- tively. Managers should carefully evaluate the values and current cultural fields to develop the practical plans and necessary policies for the creation of an environment and cultural atmosphere of the sponsor, so that they can be sure about the successful implementation of TQM and improvement of organizational performance. REFERENCES [1] P. B. Crosby, “Quality is Free,” McGraw-Hill, New York, 1979. [2] W. E. Deming, “Out of Crisis,” Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1986. [3] A. V. Feigenbaum, “Total Quality Control,” 3rd Revised Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1991. [4] K. Ishikawa, “What Is Total Quality Control? The Japa- nese Way,” Prentice-Hall, London, 1985. [5] J. M. Juran and F. M. Gryna, “Quality Analysis and Plan- ning,” 4th Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York, 2001. [6] G. Easton and S. Jarrell, “The Effects of Total Quality Management on Corporate Performance: An Empirical Investigation,” The Journal of Business, Vol. 71, No. 2, 1998, pp. 253-307. doi:10.1086/209744 [7] J. W. Dean JR and D. E. Bowen, “Management Theory and Total Quality: Improving Research and Practice through Theory Development,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 19, No. 3, 1994, pp. 392-418. [8] J. R. Hackman and R. Wageman, “Total Quality Man- agement: Empirical, Conceptual, and Practical Issues,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 40, No. 2, 1995, pp. 309-342. doi:10.2307/2393640 [9] S. Lagrosen, “Exploring the Impact of Culture on Quality Management,” International Journal of Quality & Reli- ability Management, Vol. 20, No. 4, 2003, pp. 473-487. doi:10.1108/02656710310468632 [10] T. C. Powell, “Total Quality Management as Competitive Advantage: A Review and Empirical Study,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 16, No. 1, 1995, pp. 15-27. doi:10.1002/smj.4250160105 [11] D. I. Prajogo and A. S. Sohal, “The Relationship between TQM Practices, Quality Performance and Innovation Performance: An Empirical Examination,” International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management Review, Vol. 20, No. 8, 2003, pp. 901-918. doi:10.1108/02656710310493625. [12] I. Sila, “Examining the Effects of Contextual Factors On TQM and Performance through the Lens of Organizational Theories: An Empirical Study,” Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 25, No. 1, 2007, pp. 83-109. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2006.02.003 [13] M. Terziovski, “Quality Management Practices and the Relationship with Customer Satisfaction and Productivity Improvement,” Management Research News, Vol. 29, No. 7, 2006, pp. 414-424. doi:10.1108/01409170610690871 [14] J. Y. Jung and S. Hong, “Organizational Citizenship Be- haviour (OCB), TQM and Performance at the Maqui- ladora,” International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, Vol. 25, No. 8, 2008, pp. 793-808. doi:10.1108/02656710810898612 [15] T. Y. Choi, and K. Eboch, “The TQM Paradox: Relations among TQM Practices, Plant Performance, and Customer Satisfaction,” Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 17, No. 1, 1998, pp. 59-75. doi:10.1016/S0272-6963(98)00031-X [16] A. Ngowi, “Impact of Culture on the Application of TQM in the Construction Industry in Botswana,” International Journal of Quality & Reli ability Management, Vol. 17, No. 4-5, 2000, pp. 442-452. doi:10.1108/02656710010298517 [17] T. J. Peters and R. H. Waterman, “In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best-Run Companies,” Harper & Row, New York, 1982. [18] E. B. Tylor, “Primitive Cultures: Research into the De- velopment of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Language, Art and Custom,” J. Murray, London, 1903. [19] G. Hansen and B. Wernerfelt, “Determinants of Firm Performance: The Relative Impact of Economic and Or- ganizational Factors,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 10, No. 3, 1989, pp. 399-411. doi:10.1002/smj.4250100502. [20] L. Schein, “The Road to Total Quality: Views of Industry Experts.” The Conference Board, New York, 1990. [21] T. Deal and A. Kennedy, “Corporate Cultures: The Rites and Rituals of Organizational Life,” Addison-Wesley Reading, Boston, 1982. [22] R. Goffee and G. Jones, “The Character of a Corporation,” Harper Business, London, 1998. [23] J. Martin, “Cultures in Organizations—Three Perspec- tives,” Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1992. [24] E. J. Wallach, “Individuals and Organization: The Cultural Match,” Training and Development Journal, Vol. 37, No. 2, 1983, pp. 28-36. [25] G. H. Hofstede, “Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values,” Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, 1984. [26] R. F. Zammuto and J. Y. Krakower, “Quantitative and Qua- litative Studies of Organizational Culture,” Organizational Change and Development, Vol. 5, 1991, pp. 83-114. [27] A. K. Yeung, J. W. Brockbank and D. O. Ulrich, “Organ- izational Culture and Human Resource Practices: An Em- pirical Assessment,” Research in Organizational Change and Development, Vol. 5, 1991, pp. 59-81. [28] S. G. Harris, “Organizational Culture and Individual Sense- Making: A Schema-Based Perspective,” Organization Sci- ence, Vol. 5, No. 3, 1994, pp. 309-321. doi:10.1287/orsc.5.3.309 [29] K. N. Al-Khalifa and E. M. Aspinwall, “Using the Com- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. AJIBM  The Impact of Organisational Culture on the Implementation of TQM: Empirical Study in the Iranian Oil Company 215 peting Values Framework to Identify the Ideal Profile for TQM: A UK Perspective,” International Manufacturing Technology and Management, Vol. 2, No. 1-7, 2000, pp. 1024- 1040. [30] L. M. Bennet and M. A. Kerr, “A Systems Approach to the Implementation of Total Quality Management,” Total Quality Management, Vol. 7, No. 6, 1996, pp. 631-666. doi:10.1080/09544129610531 [31] J. R. Detert, R. G. Schroeder and J. J. Mauriel, “A Framework for Linking Culture and Improvement Initia- tive in Organizations,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 25, No. 4, 2000, pp. 850-863. [32] N. Hoffman and R. Klepper, “Assimilating New Tech- nologies: The Role of Organizational Culture,” Informa- tion System Management, Vol. 17, No. 2, 2000, pp. 36-42. [33] P. S. Kim, W. Pindur and K. Reynolds, “Creating a New Organizational Culture: The Key to Total Quality Man- agement in the Public Sector,” International Journal of Public Administration, Vol. 18, No. 4, 1995, pp. 667-709. doi:10.1080/01900699508525027 [34] A. Wayne, W. Mooney and D. H. Seldon, “Culture Change Empowerment at Sweetheart Cup Company, Inc., Bakery Division,” Hospital Material Management Quar- terly, Vol. 21, No. 1, 1999, pp. 53-58. [35] R. E. Quinn and J. Rohrbaugh, “A Spatial Model of Ef- fectiveness Criteria: Towards a Competing Values Ap- proach to Organizational Analysis,” Management Scie nce , Vol. 29, No. 3, 1983, pp. 363-377. doi:10.1287/mnsc.29.3.363 [36] D. R. Denison and G. M. Spreitzer, “Organizational Cul- ture and Organizational Development: A Competing Va- lues Approach,” Research in Organizational Change and Development, Vol. 5, 1991, pp. 1-21. [37] J. F. Henri, “Organizational Culture and Performance Measurement Systems,” Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 31, No. 1, 2006, pp. 77-103. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2004.10.003. [38] R. E. Quinn, M. R. McGrath, P. J. Frost and L. F. Moore, “The Transformation of Organizational Cultures: A Com- peting Values Perspective,” Beverly Hills: Sage Publica- tions, 1985, pp. 315-334. [39] R. E. Quinn and J. R. Kimberly, “Paradox, Planning, and Perseverance: Guidelines for Managerial Practice,” Man- aging Organizational Transitions, 1984, pp. 295-313. [40] R. E. Quinn and G. M. Spreitzer, “The Sychometrics of the Competing Values Culture Instrument and an Analy- sis of the Impact of Organizational Culture on Quality of Life,” Research in Organizational Change and Develop- ment, Vol. 1, No. 5, 1991, pp. 115-142. [41] K. S. Cameron and R. E. Quinn, “Diagnosing and Chang- ing Organizational Culture: Based on the Competing Values Framework,” Addison-Wesley Publishing, Boston, 1999. [42] C. M. McDermott and G. N. Stock, “Organizational Cul- ture and Advanced Manufacturing Technology Imple- mentation,” Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 17, No. 5, 1999, pp. 521-533. doi:10.1016/S0272-6963(99)00008-X [43] G. N. Stock, K. L. McFadden and C. R. Gowen, “Organ- izational Culture, Critical Success Factors, and the Re- duction of Hospital Errors,” International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 106, No. 2, 2007, pp. 368- 392. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2006.07.005 [44] J. Juran, “Quality Control Handbook,” McGraw Hill, New York, 1988. [45] J. S. Oakland, “Total Quality Management,” Butterworth- Heinemann, Oxford, 1993. [46] S. Shiba, A. Graham and D. Walden, “A New American TQM. Four Practical Revolutions in Management,” Cen- tre for Quality Management, Productivity Press, Portland, 1993. [47] B. G. Dale, “Self-Assessment: Guidelines for Companies, Brussels, European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM),” Blackwell Publishers, Oxford, 1999. [48] U. Hellsten and B. Klefsjö, “TQM as a Management Sys- tem Consisting of Values, Techniques and Tools,” The TQM Magazine, Vol. 12, No. 4, 2000, pp. 238-255. doi:10.1108/09544780010325822 [49] K. Bright and C. L. Cooper, “Organizational Culture and the Management of Quality,” Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 8, No. 6, 1993, pp. 21-27. doi:10.1108/02683949310047437 [50] S. M. Shortell, J. O’Brien, J. Carman, R. Foster, E. Hughes, H. Boerstler and E. O’Connor, “Assessing the Impact of Continuous Quality Improvement/Total Quality Manage- ment: Concept versus Implementation,” Health Services Research, Vol. 30, No. 2, 1995, pp. 377-402. [51] E. H. Schein, “Organizational Culture and leadership,” 2nd Edition, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 1992. [52] M. Beer, “Why Total Quality Management Programs Do Not Persist: The Role of Management Quality and Impli- cations for Leading a TQM Transformation,” Decision Sciences, Vol. 34, No. 4, 2003, pp. 623-642. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5414.2003.02640.x [53] W. G. Edward Jr., “Organizational Culture, TQM, and Business Process Reengineering an Empirical Compari- son,” Team Performance Management, Vol. 5, No. 5, 1999, pp.164-170. doi:10.1108/13527599910288993 [54] N. Jabnoun and K. Sedrani, “TQM, Culture, and Per- formance in UAE Manufacturing Firms,” Quality Man- agement Journal, Vol. 12, No. 4, 2005, pp. 10-16. [55] E. A. Bardoel and S. S. Amrik, “The Role of the Cultural Audit in Implementing Quality Improvement Programs,” International Journal of Quality & Reliability Manage- ment, Vol. 16, No. 3, 1999, pp. 263-277. doi:10.1108/02656719910223755. [56] X. Zu, L. D. Fredendall and T. L. Robbins, “Organiza- tional Culture and Quality Practices in Six Sigma,” De- partment of Information Sciences and Systems Morgan State University, Baltimore, 2006. [57] J. Batten, “A Total Quality Culture,” Management Review, Vol. 83, No. 5, 1993, p. 61. [58] G. K. Kanji, “Total Quality Culture,” Total Quality Mana- gement, Vol. 8, No. 6, 1997, pp. 417-428. doi:10.1080/0954412979424 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. AJIBM  The Impact of Organisational Culture on the Implementation of TQM: Empirical Study in the Iranian Oil Company Copyright © 2012 SciRes. AJIBM 216 [59] A. Strolle, “Creating a Total Quality Management Culture Is Everyone’s Business,” Research Technology Manage- ment, Vol. 34, 1991, pp. 8-9. [60] D. Dow, D. Samson and D. Ford, “Exploring the Myth: Do All Quality Management Practices Contribute to Su- perior Quality Performance,” Production and Operations Management, Vol. 8, No. 1, 1999, pp. 1-27. doi:10.1111/j.1937-5956.1999.tb00058.x [61] M. Terziovski and D. Samson, “The Effect of Company Size on the Relationship between TQM Strategy and Or- ganizational Performance,” The TQM Magazine, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2000, pp. 144-149. doi:10.1108/09544780010318406 [62] G. Zeitz, R. Johannesson and J. E. Ritchie, “Employee Survey Measuring Total Quality Management Practices and Culture,” Group and Organization Management, Vol. 22, No. 4, 1997, pp. 414-444. doi:10.1177/1059601197224002 [63] E. H. Schein, “Organizational Culture and Leadership: A Dynamic View,” Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco, 1985. [64] G. Johnson, “Managing Strategic Change -Strategy, Cul- ture and Action,” Long Range Planning, Vol. 25, No. 1, 1993, pp. 28-36. doi:10.1016/0024-6301(92)90307-N [65] D. M. Lascelles and B. G. Dale, “A Review of the Issues Involved in Quality Improvement,” International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, Vol. 5, No. 5, 1988, pp. 76-94. doi:10.1108/eb002920 [66] A. Wilkinson, P. Allen and E. Snape, “TQM and the Management of Labor,” Em p loyee Rela tions, Vol. 13, No. 1, 1991, pp. 24-31. doi:10.1108/01425459110002349 [67] M. Idris, W. McEwan and N. Belavendram, “The Adop- tion of ISO 9000 and Total Quality Management in Ma- laysia,” The TQM Magazine, Vol. 8, No. 5, 1996, pp. 65-68. doi:10.1108/09544789610146079 [68] M. Kaye and M. Dyason, “East Meets West in the Quality Management Experience,” Quality World, Vol. 23, No. 8, 1997, pp. 648-652. [69] A. Goldman, “The Centrality of ‘Ningensei’ to Japanese Negotiating and Interpersonal Relationships: Implications for US-Japanese Communication,” International Journal of Intercultural Relations, Vol. 18, No. 1, 1994, pp. 29- 54. [70] A. M. M. Rad, “A Survey of Total Quality Management in Iran: Barriers to Successful Implementation in Health Care Organizations,” Leadership in Health Services, Vol. 18, No. 3, 2005, pp. 12-34. doi:10.1108/13660750510611189 [71] D. I. Prajogo and D. M. McDermott, “The Relationship between Total Quality Management Practices and Organ- izational Culture,” International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 25, No. 11, 2005, pp. 1101-1122. doi:10.1108/01443570510626916 [72] J. Tata and J. Prasad, “Cultural and Structural Constraints on Total Quality Management Implementation,” Total Quality Management, Vol. 9, No. 8, 1998, pp. 703-710. doi:10.1080/0954412988172 [73] U. Hellsten and B. Klefsjö, “TQM as a Management Sys- tem Consisting of Values, Techniques and Tools,” The TQM Magazine, Vol. 12, No. 4, 2000, pp. 238-255. doi:10.1108/09544780010325822 [74] S. G. Harris, “Organizational Culture and Individual Sense- Making: A Schema-Based Perspective,” Organization Science, Vol. 5, No. 3, 1994, pp. 309-321. doi:10.1287/orsc.5.3.309 [75] X. Zu, T. L. Robbins and L. D. Fredendall, “Mapping the Critical Links between Organizational Culture and TQM/ Six Sigma Practices,” International Journal of Produc- tion Economi cs, Vol. 123, No. 1, 2010, pp. 86-106. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2009.07.009

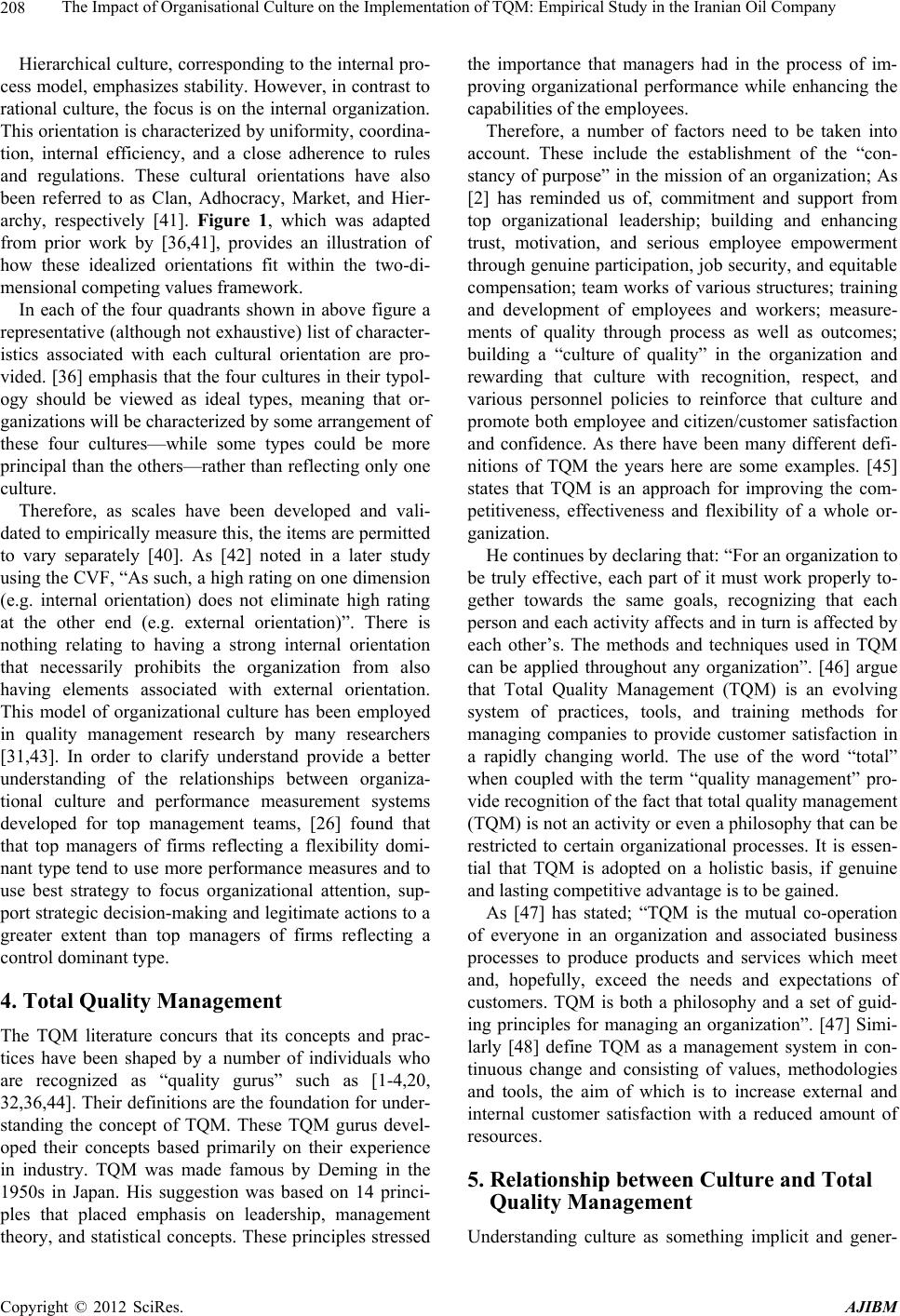

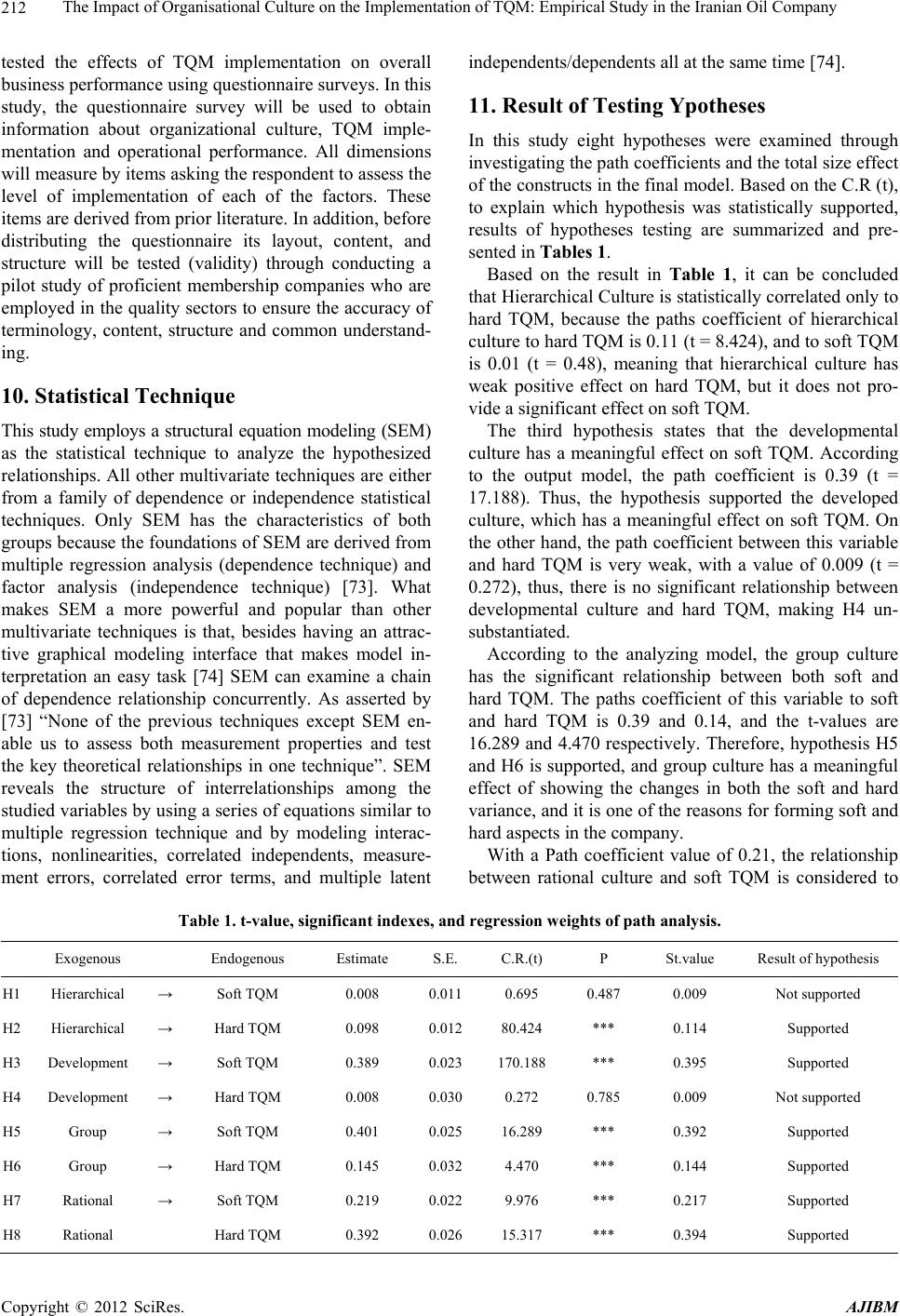

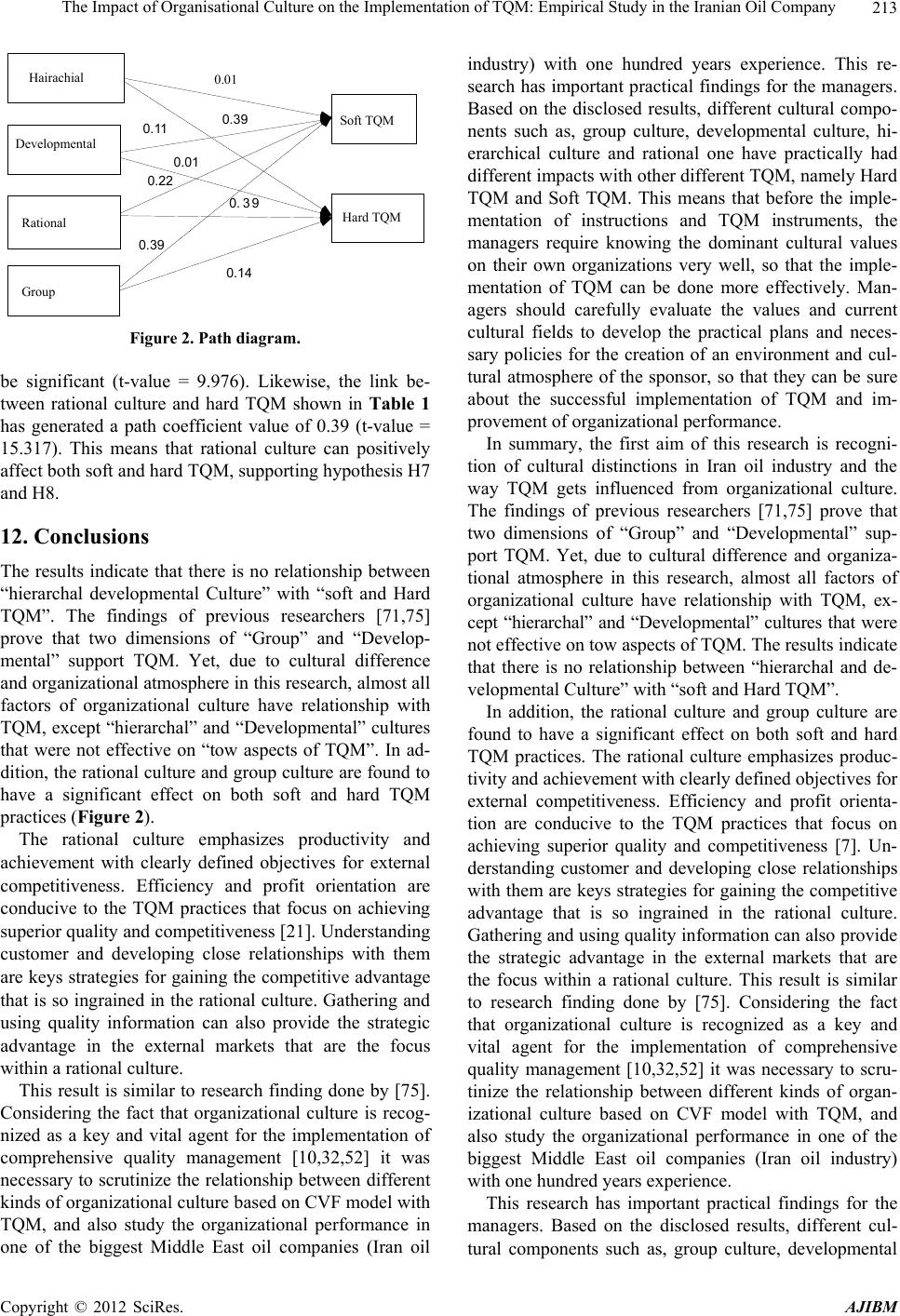

|