Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

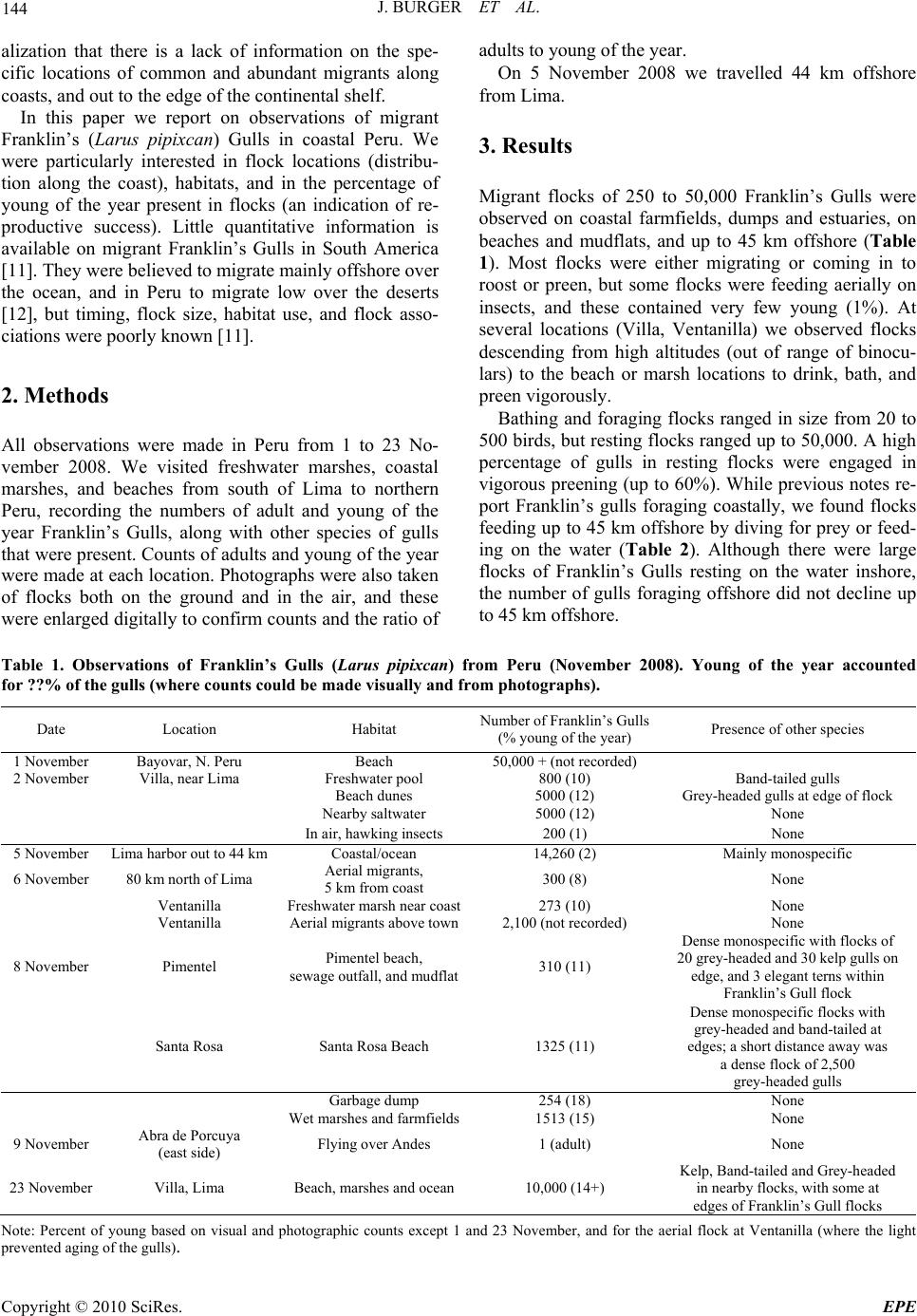

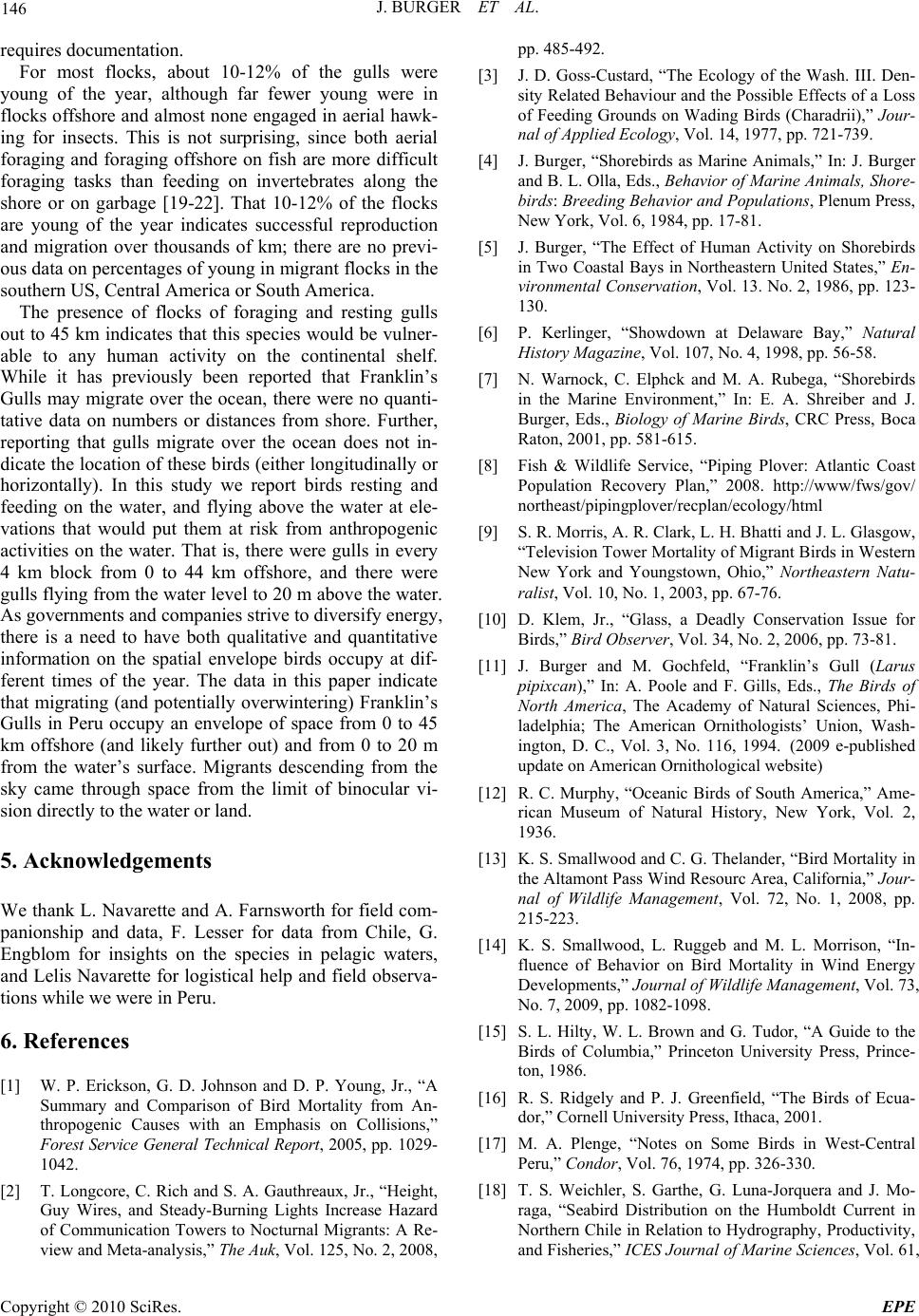

Energy and Power Engineering, 2010, 2, 143-147 doi:10.4236/epe.2010.23021 Published Online August 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/epe) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. EPE Migratory Behavior of Franklin’s Gulls (Larus pipixcan) in Peru Joanna Burger1, Michael Gochfeld2, Robert Ridgely3 1Division of Life Sciences, Rutgers University, Piscataway, USA 2Environmental and Occupational Medicine, UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, Piscataway, USA 3N. Sandwich, New Hampshire, UK E-mail: burger@biology.rutgers.edu, gochfeld@eohsi.rutgers.edu, rrridgely@earthlink.net Received March 29, 2010; revised May 10, 2010; accepted June 20, 2010 Abstract Information on the migratory pathways for birds is essential to the future citing of wind power facilities, par- ticularly in off-shore waters. Yet, relatively little is known about the coastal or offshore migratory behavior of most birds, including Franklin’s gulls (Larus pipixcan), a long-distant migrant. We report observations along the coast of Peru made in November 2008 to determine where birds concentrated. Wind facilities can not avoid regions of high avian activity without knowing where that activity occurs. Migrant flocks of 250 to 50,000 were observed on coastal farmfields, dumps and estuaries, on beaches and mudflats, and up to 45 km offshore. Bathing and foraging flocks ranged in size from 20 to 500 birds, and most flocks were monospeci- fic, with occasional grey-headed (Larus cirrocephalus) and band-tailed (L. belcheri) on the periphery. While previous notes report Franklin’s gulls foraging coastally, we found flocks feeding up to 45 km offshore by diving for prey or feeding on the water. The relative percentage of birds of the year varied in migrant flocks from zero to 14%, with lower numbers of young foraging aerially on insects (only 1%). The percentage of young feeding over the ocean decreased with increasing distance from shore; no young of the year were re- corded at 36-44 km offshore. While there were large flocks of Franklin’s gulls resting on the water inshore, the number of gulls foraging offshore did not decline up to 45 km offshore. The presence of foraging flocks of Franklin’s gulls out to 45 km offshore, and occupying space from 0 to 20 m above the water, suggests that they would be vulnerable to offshore anthropogenic activities, such as offshore drilling and wind facilities. Keywords: Migration, Larus pipixcan, Franklin’s Gulls, Gulls, Migrants, Young of the Year, Habitat Use, Flock Associations, Wind Farms, Offshore Drilling 1. Introduction The siting of wind facilities has become an important topic as governments and industry consider the possibil- ity of large-scale offshore facilities. Yet little is known of the ecology and behavior of species, such as marine mammals, fish, and birds, in offshore regions where wind facilities might be sited. Before siting many such facilities, it is essential to understand whether the loca- tions would impact ecological resources in these sites. The migratory behavior of birds is an important, but often little studied aspect of their life cycle, mainly be- cause long-distance migrants are difficult to study. They often migrate at night, at high altitudes, or at unpredict- able places and times. Further, scientists often focus on the breeding season, or on native species, or on the rare migrants, making information on abundant migrants par- ticularly lacking. Yet, for many species, migration is one of the most risky life stages, because of predation, weather conditions, obstacles (such as buildings or tow- ers [1,2]), or lack of foraging habitats [3-8]. Information on the locations, habitats, and timing of migration is needed to understand both the vulnerability of a species to natural forces, as well as to potential an- thropogenic activities, such as wind facilities. While sci- entists have long recognized the threats to migrants of anthropogenic terrestrial threats, such as buildings and towers [1,9,10], little attention has been devoted to coastal and offshore migrants. With the recent focus on renewable energy, many countries are turning to offshore wind farms, and the question of risk to avian populations that migrate offshore is coming to the fore, with the re-  J. BURGER ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. EPE 144 alization that there is a lack of information on the spe- cific locations of common and abundant migrants along coasts, and out to the edge of the continental shelf. In this paper we report on observations of migrant Franklin’s (Larus pipixcan) Gulls in coastal Peru. We were particularly interested in flock locations (distribu- tion along the coast), habitats, and in the percentage of young of the year present in flocks (an indication of re- productive success). Little quantitative information is available on migrant Franklin’s Gulls in South America [11]. They were believed to migrate mainly offshore over the ocean, and in Peru to migrate low over the deserts [12], but timing, flock size, habitat use, and flock asso- ciations were poorly known [11]. 2. Methods All observations were made in Peru from 1 to 23 No- vember 2008. We visited freshwater marshes, coastal marshes, and beaches from south of Lima to northern Peru, recording the numbers of adult and young of the year Franklin’s Gulls, along with other species of gulls that were present. Counts of adults and young of the year were made at each location. Photographs were also taken of flocks both on the ground and in the air, and these were enlarged digitally to confirm counts and the ratio of adults to young of the year. On 5 November 2008 we travelled 44 km offshore from Lima. 3. Results Migrant flocks of 250 to 50,000 Franklin’s Gulls were observed on coastal farmfields, dumps and estuaries, on beaches and mudflats, and up to 45 km offshore (Table 1). Most flocks were either migrating or coming in to roost or preen, but some flocks were feeding aerially on insects, and these contained very few young (1%). At several locations (Villa, Ventanilla) we observed flocks descending from high altitudes (out of range of binocu- lars) to the beach or marsh locations to drink, bath, and preen vigorously. Bathing and foraging flocks ranged in size from 20 to 500 birds, but resting flocks ranged up to 50,000. A high percentage of gulls in resting flocks were engaged in vigorous preening (up to 60%). While previous notes re- port Franklin’s gulls foraging coastally, we found flocks feeding up to 45 km offshore by diving for prey or feed- ing on the water (Table 2). Although there were large flocks of Franklin’s Gulls resting on the water inshore, the number of gulls foraging offshore did not decline up to 45 km offshore. Table 1. Observations of Franklin’s Gulls (Larus pipixcan) from Peru (November 2008). Young of the year accounted for ??% of the gulls (where counts could be made visually and from photographs). Date Location Habitat Number of Franklin’s Gulls (% young of the year) Presence of other species 1 November Bayovar, N. Peru Beach 50,000 + (not recorded) 2 November Villa, near Lima Freshwater pool 800 (10) Band-tailed gulls Beach dunes 5000 (12) Grey-headed gulls at edge of flock Nearby saltwater 5000 (12) None In air, hawking insects 200 (1) None 5 November Lima harbor out to 44 km Coastal/ocean 14,260 (2) Mainly monospecific 6 November 80 km north of Lima Aerial migrants, 5 km from coast 300 (8) None Ventanilla Freshwater marsh near coast273 (10) None Ventanilla Aerial migrants above town2,100 (not recorded) None 8 November Pimentel Pimentel beach, sewage outfall, and mudflat310 (11) Dense monospecific with flocks of 20 grey-headed and 30 kelp gulls on edge, and 3 elegant terns within Franklin’s Gull flock Santa Rosa Santa Rosa Beach 1325 (11) Dense monospecific flocks with grey-headed and band-tailed at edges; a short distance away was a dense flock of 2,500 grey-headed gulls Garbage dump 254 (18) None Wet marshes and farmfields1513 (15) None 9 November Abra de Porcuya (east side) Flying over Andes 1 (adult) None 23 November Villa, Lima Beach, marshes and ocean 10,000 (14+) Kelp, Band-tailed and Grey-headed in nearby flocks, with some at edges of Franklin’s Gull flocks Note: Percent of young based on visual and photographic counts except 1 and 23 November, and for the aerial flock at Ventanilla (where the light prevented aging of the gulls).  J. BURGER ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. EPE 145 Table 2. Number of Franklin’s Gulls in a coastal transect out to 44 km (Lima, Peru, November 5, 2008). Such information is directly relevant to offshore activities, such as shipping, oil drilling and wind farm construction. Distance from shore (km) Number of Franklin’s Gulls in air (additional gulls rafting on water) Percent of young of the year in flying or feeding flocks 0-4 2316 (4,200) 8 4.1-8 803 (1000) 4 8.1-12 918 (110) 5 12.1-16 74 (210) 0 16.1-20 330 1 20.1-24 300 (156) 0 24.1-28 279 3 28.1-32 804 (408) 0 32.1-36 1028 (76) 2 36.1-40 577 (180) 0 40.1-44 491 0 The relative percentage of birds of the year varied in migrant flocks from zero to 14%, with lower numbers of young foraging aerially on insects (only 1%, Table 1). The percentage of young feeding over the ocean de- creased with increasing distance from shore; no young of the year were recorded at 36-44 km offshore. The gulls we observed were mainly occupying the vertical space from the water to 20 m above the water (although mi- grants were much higher), but were concentrated below 10 m. Most flocks were monospecific, with occasional Grey- headed (Larus cirrocephalus) and Band-tailed (L. belcheri) Gulls on the periphery (Table 1). At some beaches, there were discrete and dense flocks of these two species, along with discrete flocks of kelp gulls (La- rus dominicanus) a few meters or hundreds of meters from the Franklin’s Gulls. Franklin’s Gulls resting or roosting on beaches often stood in very dense flocks, nearly touching one another. Even in dense migrant flocks, Franklin’s Gulls are vulnerable to predators. On 23 November, two Franklin’s Gulls were killed by two different Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus) visible at the same time. In one case an immature Peregrine flew up to a Franklin’s Gull flock swirling over land and flipped upside down to snatch a gull’s breast, riding with it to the ground. Five minutes later, a second immature Peregrine rose higher than a different gull flock, and dove into it in the classic manner. Although the gull flock scattered, the Peregrine pursued one bird until it slammed into the gull, exploding the gull and forcing it to the ground. Two additional observations bear mention: 1) In late October 2007, several flocks of 600-1000 birds flew high overhead (at the limit of binocular vision) at the La Ven- tosa area of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Mexico; other flocks (100-1000) flew low and close to shore moving south and east (A. Farnsworth, pers. comm.). In 2003, Franklin’s gulls had only just begun to reach the northern beaches of Chile (Valparaiso to Astero Lampa Santiago de Pacifica): from 9-10 November fewer than 20 gulls were observed at each of several different beaches, but by 10-12 November the number had built up to 100 at several locations (F. Lesser, pers. comm.). 4. Discussion With the world-wide development of renewable energy resources, such as wind power, it is essential to deter- mine before facilities are built whether there are conflicts with wildlife that would provide an ecological threat that would impact operations. Many of the initial sitings of wind facilities were within migratory or overwintering ranges of birds, and resulted in high avian mortality, and some curtailing of operations [13,14]. This paper pro- vides data that can be used in considering the offshore patterns of migratory gulls, particularly Franklin’s Gulls. The Franklin’s Gulls observed in this report were likely migrants just arriving in Peru, as judged by the large dense flocks engaged in vigorous preening, and their descent in large and continuous flocks from high altitudes. That is, when we scanned the sky with binocu- lars in areas where birds were descending, we could just make out birds at the limit of binocular vision still de- scending. The presence of relatively large flocks of 5,000 to 50,000 birds suggests that they were arriving, and had not spread out along the coast. Like other authors [12,15,16] we found them mainly along the coast, but one was in the Andes. Birds found in the high Andes may well be either lost, or merely on a different migration route. While many different foraging and migratory habitats have been reported for Franklin’s Gulls in North Amer- ica, few have been recorded for South America [11]. Habitats recorded in South America include fishmeal plants, rivers, coasts, and behind trawlers [17,18]. We found them resting, bathing and foraging on beaches, saltwater and freshwater marshes, sewage outfalls, farm- fields, and garbage dumps. While these habitats are not unexpected, given their use of them in North America, it  J. BURGER ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. EPE 146 requires documentation. For most flocks, about 10-12% of the gulls were young of the year, although far fewer young were in flocks offshore and almost none engaged in aerial hawk- ing for insects. This is not surprising, since both aerial foraging and foraging offshore on fish are more difficult foraging tasks than feeding on invertebrates along the shore or on garbage [19-22]. That 10-12% of the flocks are young of the year indicates successful reproduction and migration over thousands of km; there are no previ- ous data on percentages of young in migrant flocks in the southern US, Central America or South America. The presence of flocks of foraging and resting gulls out to 45 km indicates that this species would be vulner- able to any human activity on the continental shelf. While it has previously been reported that Franklin’s Gulls may migrate over the ocean, there were no quanti- tative data on numbers or distances from shore. Further, reporting that gulls migrate over the ocean does not in- dicate the location of these birds (either longitudinally or horizontally). In this study we report birds resting and feeding on the water, and flying above the water at ele- vations that would put them at risk from anthropogenic activities on the water. That is, there were gulls in every 4 km block from 0 to 44 km offshore, and there were gulls flying from the water level to 20 m above the water. As governments and companies strive to diversify energy, there is a need to have both qualitative and quantitative information on the spatial envelope birds occupy at dif- ferent times of the year. The data in this paper indicate that migrating (and potentially overwintering) Franklin’s Gulls in Peru occupy an envelope of space from 0 to 45 km offshore (and likely further out) and from 0 to 20 m from the water’s surface. Migrants descending from the sky came through space from the limit of binocular vi- sion directly to the water or land. 5. Acknowledgements We thank L. Navarette and A. Farnsworth for field com- panionship and data, F. Lesser for data from Chile, G. Engblom for insights on the species in pelagic waters, and Lelis Navarette for logistical help and field observa- tions while we were in Peru. 6. References [1] W. P. Erickson, G. D. Johnson and D. P. Young, Jr., “A Summary and Comparison of Bird Mortality from An- thropogenic Causes with an Emphasis on Collisions,” Forest Service General Technical Report, 2005, pp. 1029- 1042. [2] T. Longcore, C. Rich and S. A. Gauthreaux, Jr., “Height, Guy Wires, and Steady-Burning Lights Increase Hazard of Communication Towers to Nocturnal Migrants: A Re- view and Meta-analysis,” The Auk, Vol. 125, No. 2, 2008, pp. 485-492. [3] J. D. Goss-Custard, “The Ecology of the Wash. III. Den- sity Related Behaviour and the Possible Effects of a Loss of Feeding Grounds on Wading Birds (Charadrii),” Jour- nal of Applied Ecology, Vol. 14, 1977, pp. 721-739. [4] J. Burger, “Shorebirds as Marine Animals,” In: J. Burger and B. L. Olla, Eds., Behavior of Marine Animals, Shore- birds: Breeding Behavior and Populations, Plenum Press, New York, Vol. 6, 1984, pp. 17-81. [5] J. Burger, “The Effect of Human Activity on Shorebirds in Two Coastal Bays in Northeastern United States,” En- vironmental Conservation, Vol. 13. No. 2, 1986, pp. 123- 130. [6] P. Kerlinger, “Showdown at Delaware Bay,” Natural History Magazine, Vol. 107, No. 4, 1998, pp. 56-58. [7] N. Warnock, C. Elphck and M. A. Rubega, “Shorebirds in the Marine Environment,” In: E. A. Shreiber and J. Burger, Eds., Biology of Marine Birds, CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2001, pp. 581-615. [8] Fish & Wildlife Service, “Piping Plover: Atlantic Coast Population Recovery Plan,” 2008. http://www/fws/gov/ northeast/pipingplover/recplan/ecology/html [9] S. R. Morris, A. R. Clark, L. H. Bhatti and J. L. Glasgow, “Television Tower Mortality of Migrant Birds in Western New York and Youngstown, Ohio,” Northeastern Natu- ralist, Vol. 10, No. 1, 2003, pp. 67-76. [10] D. Klem, Jr., “Glass, a Deadly Conservation Issue for Birds,” Bird Observer, Vol. 34, No. 2, 2006, pp. 73-81. [11] J. Burger and M. Gochfeld, “Franklin’s Gull (Larus pipixcan),” In: A. Poole and F. Gills, Eds., The Birds of North America, The Academy of Natural Sciences, Phi- ladelphia; The American Ornithologists’ Union, Wash- ington, D. C., Vol. 3, No. 116, 1994. (2009 e-published update on American Ornithological website) [12] R. C. Murphy, “Oceanic Birds of South America,” Ame- rican Museum of Natural History, New York, Vol. 2, 1936. [13] K. S. Smallwood and C. G. Thelander, “Bird Mortality in the Altamont Pass Wind Resourc Area, California,” Jour- nal of Wildlife Management, Vol. 72, No. 1, 2008, pp. 215-223. [14] K. S. Smallwood, L. Ruggeb and M. L. Morrison, “In- fluence of Behavior on Bird Mortality in Wind Energy Developments,” Journal of Wildlife Management, Vol. 73, No. 7, 2009, pp. 1082-1098. [15] S. L. Hilty, W. L. Brown and G. Tudor, “A Guide to the Birds of Columbia,” Princeton University Press, Prince- ton, 1986. [16] R. S. Ridgely and P. J. Greenfield, “The Birds of Ecua- dor,” Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 2001. [17] M. A. Plenge, “Notes on Some Birds in West-Central Peru,” Condor, Vol. 76, 1974, pp. 326-330. [18] T. S. Weichler, S. Garthe, G. Luna-Jorquera and J. Mo- raga, “Seabird Distribution on the Humboldt Current in Northern Chile in Relation to Hydrography, Productivity, and Fisheries,” ICES Journal of Marine Sciences, Vol. 61,  J. BURGER ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. EPE 147 No. 1, 2004, pp. 148-154. [19] D. C. Duffy, “The Foraging Ecology of Peruvian Sea- birds,” The Auk, Vol. 100, No. 4, 1983, pp. 800-810. [20] J. Burger, “Foraging Efficiency in Gulls: A Congeneric Comparison of Age Differences in Efficiency and Age of Maturity,” Studies in Avian Biology, Vol. 10, No. 225, 1987, pp. 83-89. [21] J. Burger, “Foraging Behavior in Gulls: Differences in Method, Prey, and Habitat,” Colonial Waterbirds, Vol. 11, No. 1, 1988, pp. 9-23. [22] D. A. Shealer, “Foraging Behavior and Food of Sea- birds,” In: E. A. Shreiber and J. Burger, Eds., Biology of Marine Birds, CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2001, pp. 137- 178. |