Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

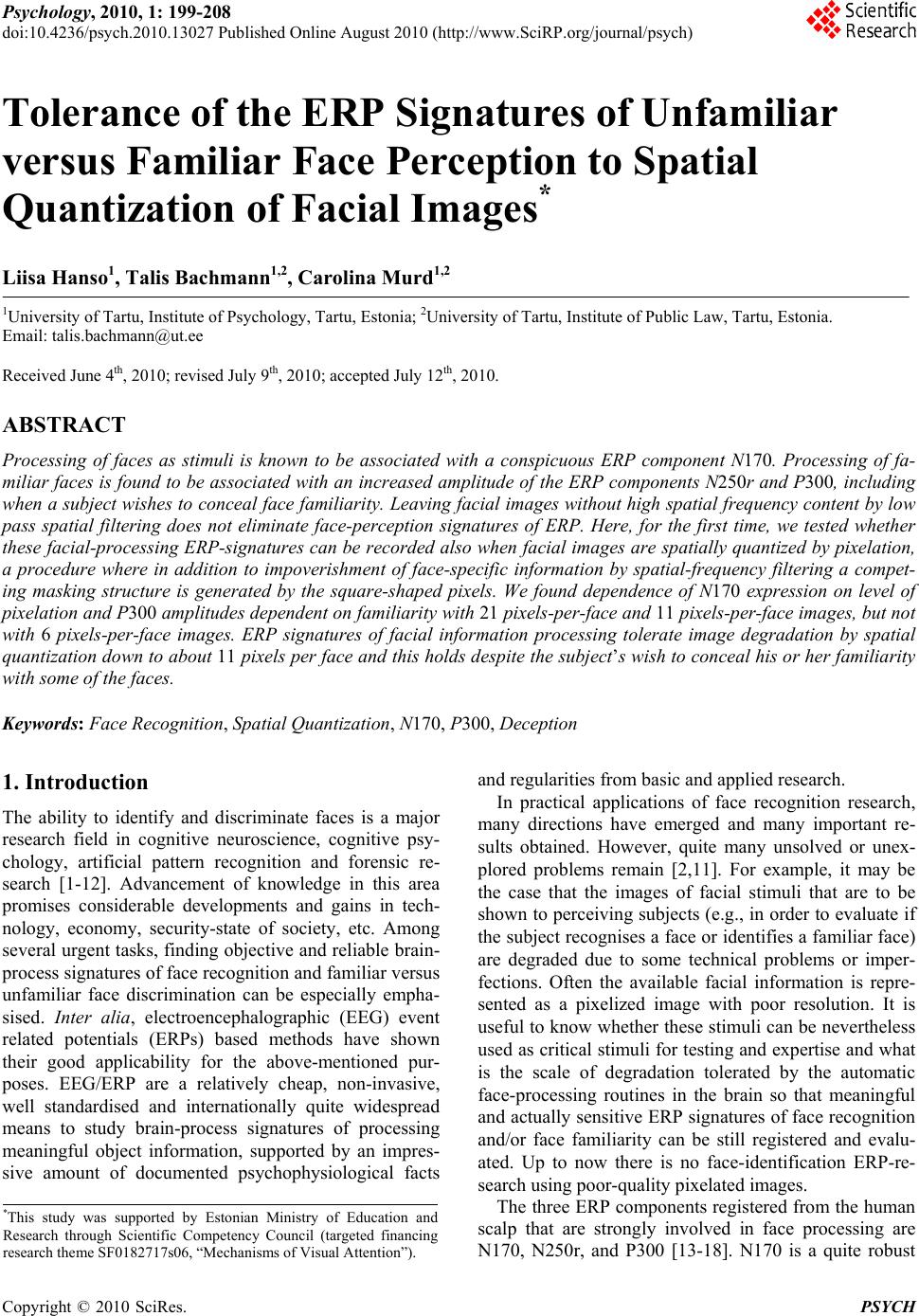

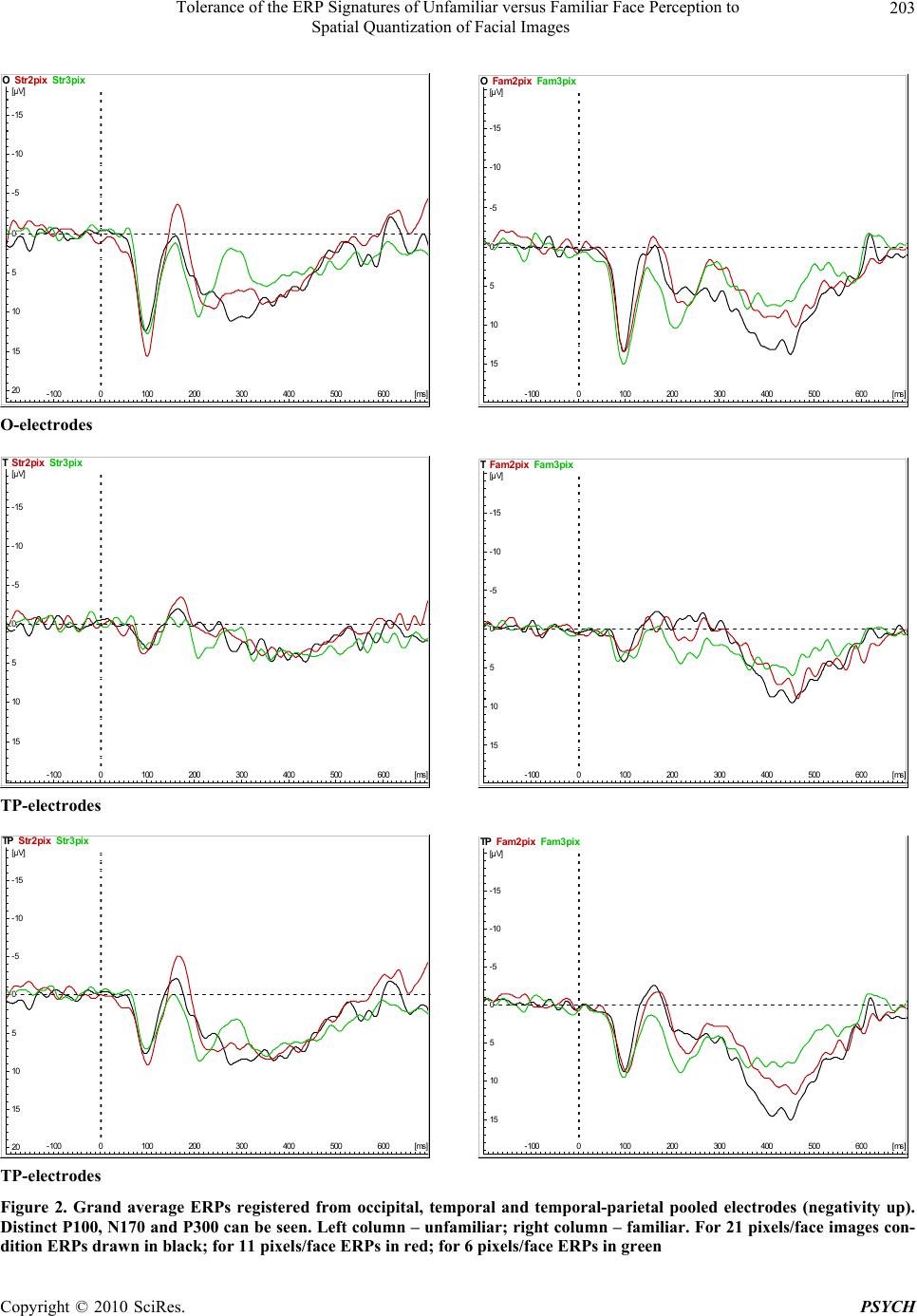

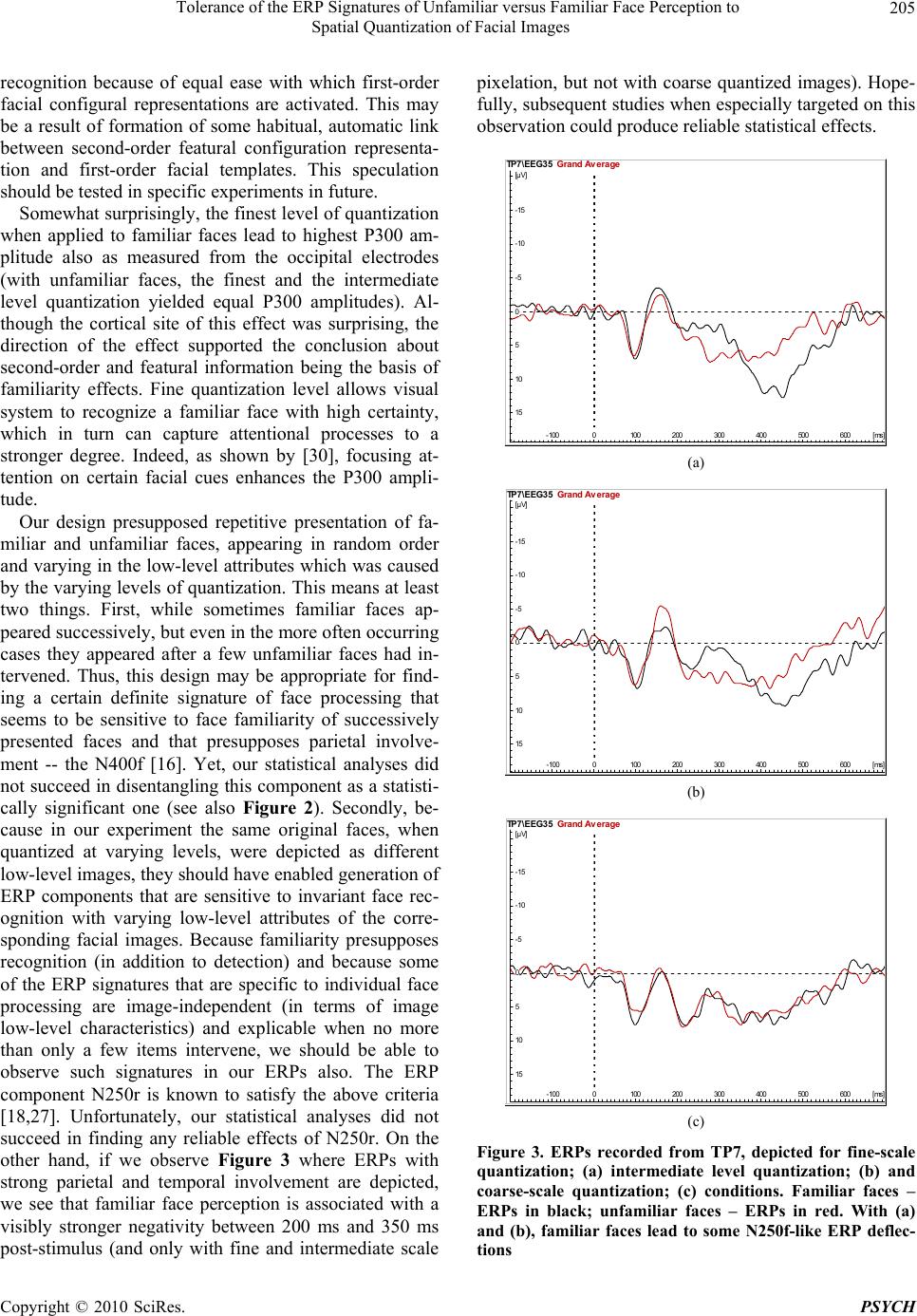

Psychology, 2010, 1: 199-208 doi:10.4236/psych.2010.13027 Published Online August 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 199 Tolerance of the ERP Signatures of Unfamiliar versus Familiar Face Perception to Spatial Quantization of Facial Images* Liisa Hanso1, Talis Bachmann1,2, Carolina Murd1,2 1University of Tartu, Institute of Psychology, Tartu, Estonia; 2University of Tartu, Institute of Public Law, Tartu, Estonia. Email: talis.bachmann@ut.ee Received June 4th, 2010; revised July 9th, 2010; accepted July 12th, 2010. ABSTRACT Processing of faces as stimuli is known to be associated with a conspicuous ERP component N170. Processing of fa- miliar faces is found to be associated with an increased amplitude of the ERP components N250r and P300, including when a subject wishes to conceal face familiarity. Leaving facial images without high spatial frequency content by low pass spatial filtering does not eliminate face-perception signatures of ERP. Here, for the first time, we tested whether these facial-processing ERP-signatures can be recorded also when facial images are spatially quantized by pixelation, a procedure where in addition to impoverishment of face-specific information by spatial-frequency filtering a compet- ing masking structure is generated by the square-shaped pixels. We found dependence of N170 expression on level of pixelation and P300 amplitudes dependent on familiarity with 21 pixels-per-face and 11 pixels-per-face images, but not with 6 pixels-per-face images. ERP signatures of facial information processing tolerate image degradation by spatial quantization do wn to abou t 11 pixels per face and this holds despite th e subject’s wish to concea l his or her familiarity with some of the faces. Keywords: Face Recognition, Spatial Quantization, N170, P300, Deception 1. Introduction The ability to identify and discriminate faces is a major research field in cognitive neuroscience, cognitive psy- chology, artificial pattern recognition and forensic re- search [1-12]. Advancement of knowledge in this area promises considerable developments and gains in tech- nology, economy, security-state of society, etc. Among several urgent tasks, finding objective and reliable brain- process signatures of face recogn ition and fa miliar versus unfamiliar face discrimination can be especially empha- sised. Inter alia, electroencephalographic (EEG) event related potentials (ERPs) based methods have shown their good applicability for the above-mentioned pur- poses. EEG/ERP are a relatively cheap, non-invasive, well standardised and internationally quite widespread means to study brain-process signatures of processing meaningful object information, supported by an impres- sive amount of documented psychophysiological facts and regularities from basic and applied research. In practical applications of face recognition research, many directions have emerged and many important re- sults obtained. However, quite many unsolved or unex- plored problems remain [2,11]. For example, it may be the case that the images of facial stimuli that are to be shown to perceiving subjects (e.g., in order to evaluate if the subject recognises a face or identifies a familiar face) are degraded due to some technical problems or imper- fections. Often the available facial information is repre- sented as a pixelized image with poor resolution. It is useful to know whether these stimuli can be nevertheless used as critical stimuli for testing and expertise and what is the scale of degradation tolerated by the automatic face-processing routines in the brain so that meaningful and actually sensitive ERP sig natures of face recognition and/or face familiarity can be still registered and evalu- ated. Up to now there is no face-identification ERP-re- search using poor-quality pixelated images. The three ERP components registered from the human scalp that are strongly involved in face processing are N170, N250r, and P300 [13-18]. N170 is a quite robust *This study was supported by Estonian Ministry of Education and Research through Scientific Competency Council (targeted financing research theme SF0182717s06, “Mechanisms of Visual Attention”).  Tolerance of the ERP Signatures of Unfamiliar versus Familiar Face Perception to Spatial Quantization of Facial Images Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 200 signature of facial image processing found in many stud- ies and under a wide variety of facial stimuli, spectral contents of face-images and perceptual tasks [13,16,17, 19-23]. It is a negative potential deflection appearing about 130-200 ms after presentation of a facial stimulus, peaking at about 170 ms. N170 can be best registered from the occipito-temporal, temporal and temporal-pa- rietal electrodes [15,19,24]. It appears that face familiar- ity does not influence N170 [16,25,26]. N250r is a nega- tive-polarity ERP component that has been related to image-independent representations of familiar faces aid- ing person recognition [27]. P300 as a positive-polarity potential that appears about 300-500 ms after stimulus presentation is widely accepted as a signature of work- ing-memory analysis involving categorical cognitive processing and comparisons, context updating, resource allocation and meaningfulness evaluation [28,29]. A va- riety of P300 called P3b which is a signature of cate- gorical, memory dependent processing is best expressed over parietal and temporal-parietal areas. Importantly, the amplitude of the late positive ERP components may be significantly increased when familiar, relevant or at- tended stimuli (e.g., faces) as opposed to unfamiliar or nonrelevant stimuli are presented [18,30-33]. Because there are many brain sites that increase breadth and am- plitude of activity in reponse to highly meaningful or attention-demanding faces as opposed to less significant faces [34] it is not unanimously agreed upon what are the exact brain sites maximally contributing to the increase in the brain responses to significant faces. Importantly, the increased brain response to more highly meaningful stimuli occurs even when a subject tries to conceal fa- miliarity of a particular stimulus item that reliably has a capacity to lead to an enhanced response such as the P300 amplitude [33]. With familiar faces, P300 may be transformed so that a face-specific negative deflection, N400f precedes typical positivity at about 300-500 ms post stimulus [16]. As mentioned above, it is important to know whether and to what extent ERPs that are sen sitive to faces and facial familiarity can be present when facial information is degraded. Some studies have manipulated facial stimulus-images by filtering out detailed (facial) information by spatial low-pass filtering and then measured subjects’ ERP re- sponses [17,20,21,35]. It appears that if only coarse-scale face related spatial information is present, ERPs still dif- ferentiate between faces and non-faces and/or between different categorization tasks, with coarse-scale informa- tion sometimes leading to relatively better expressed N170 compared to fine-scale faces [20,21,35,36]. How- ever, simple spatial filtering may bring in confounds be- tween image spatial frequency components and lower level features such as luminance and contrast (see, e.g., [37,38] on how to circumvent these problems]. It is therefore important for new studies to use experimental controls over these fac t ors (see our text below). In practice, security surveillance recordings also often produce facial images that are impoverished, degraded and/or distorted, which makes obstacles for high-quality and reliable evidence-gathering and eyewitness reports [2,11,31]. However, a typical degradation of such images involves not only and not so much spatial low-pass fil- tering per se, but also often these images are spatially quantized (pixelized) so that in addition to the filtering out of higher spatial frequencies of image content (its fine detail), the mosaic-like structure of the squares pro- duced by the image-processing algorithms that are used in producing pixelised images represents an additional image structure besides the authentic facial low-frequ- ency content [39-43]. This extra image content (squares with vertical and horizontal sharp edges and orthogonal corners; see, e.g., Figure 1) provides a competing struc- ture for the perceptual systems of image feature extrac- tion, figure-ground discrimination and visual-categorical interpretation. In a sense, this procedure, in addition to filtering out virtually all of the useful fine-scale informa- tion does also something else – it adds also a newly formed masking structure. It is important to know whether brain systems of facial information processing can be immune to this kind of complication or not. Equally important, it would be useful to know whether spatial quantization could change an image in a way that different cues of diag nosticity become to be used , but the ERP signatures of face processing, by using these new cues, may show sensitivity to categorical facial differ- ences (e.g., familiarity). Hypothetically, this may lead to increased categorical sensitivity o f ERPs compared to the absence of this kind of sensitivity which has been the case when unquantized, but otherwise filtered face-im- ages have been used [16,25,26]. The existing research literature does not provide an answer to these questions. Most of the studies of spatially quantised image rec- ognition have been strictly psychophysical – e.g., [39-42]. Up to our knowledge, the only psychophysiological study where spatially quantized images of faces were used was that by Ward [44], but because monkeys were used as perceivers and because only very coarse quan- tized images with 8 pixels/face or less were used, her findings showing that discrimination between quantized face and nonface stimuli was not possible cannot be strongly ge neralized. Coincidentally, spatial manipulation by quantization is free of the methodological problem that accompanies the traditional standard spatial filtering where selectively filtering out certain frequencies may also lead to filtering out luminance and/or local contrast information to a dif- ferent extent. Because spatial pixelation is based on cal- culating average luminances within precisely defined  Tolerance of the ERP Signatures of Unfamiliar versus Familiar Face Perception to Spatial Quantization of Facial Images Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 201 square-shaped areas of the original image, spatially quantized images do not bring in artefacts of unequal luminance filtering. Face-sensitive bioelectrical signatures of processing heavily rely on configural attributes of facial images, with three main types of configural cues involved [6]: 1) first-order relational processing allowing to specify a stimulus as a face as such, 2) holistic (Gestalt-) process- ing leading to a mutually supportive, integrated structural set of features, 3) second-order relational processing that uses metric information about spacing of facial features and thus enables discrimination of individual faces. By spatially quantizing faces, and beginning from a rela- tively coarse level of quantization, we eliminate local featural information and seriously disturb second-order configural processing, at the same time introducing rela- tively less distortions into first-order and into holistic processing. If it would happen that in termediate level (or even coarse level) spatial quantization does not eliminate face-sensitive ERP signatures and maybe even does not eliminate EEG-sensitivity to the familiarity of faces, then we would show that coarse-scale configural information in the conditions where it is presented within the context of a competing and conflicting structural cues is proc- essed to the extent that allows one to carry out instru- mental procedures of detecting (familiar) face detection and discri minat i on with quantized images. The present study has two main ai ms. First, it is to test if spatially quantized images of faces can carry percep- tual information sufficient for brain processes to dis- criminate different classes of facial images and if the answer to this question is positive – to see what is the approximate spatial scale of pixelation coarseness that allows to carry this information. Th e second ai m is to test whether spatially quantized facial images when they can help lead to ERP signatures of face discrimination enable to differentiate familiar face image processing and unfa- miliar face image processing in the conditions where the perceiver tries to conceal his/her familiarity with some of the faces. We put forward three general hypotheses. 1. Spatially quantized images of faces as stimuli carry con- figural information that can be used by brain processes to generate ERP signatures typical for facial image proc- essing (e.g., N170) and can therefore lead to reliable ERP differences as a function of the scale of spatial quantiza- tion. 2. Spatially quantized images of faces lead to ERP signatures that are sensitive to face familiarity (e.g., P300) despite that local featural information is filtered out, sec- ond-order configural information is distorted and masked and despite that subjects try to conceal their familiarity with some of the stimuli faces. 3. There is a critical level of coarseness of spatial quantization beyond which ERP signatures of processing facial images do not anymore discriminate between familiar and unfamiliar faces. 2. Methods 2.1 Participants Six female subjects (age range 20-25 years) who were naïve about the research hypotheses of the present study participated. All had normal or corrected-to-normal vi- sion. The subject sample was selected opportunistically from the pool of bachelor-level students of Tallinn Uni- versity. 2.2 Experimental Setup and Procedure Frontal images of human faces were used as the visual stimuli. Each subject was presented repeatedly with 6 versions of the facial images of the 2 persons well famil- iar to them and repeatedly with 30 versions of the facial images of 10 unfamiliar persons. The images subtended 3.8° × 5.7°. All images were achromatic gray scale im- ages. They varied between three levels of spatial quanti- zation (pixelation by a mosaic transform): 8 × 8 screen- pixels (corresponding to about 21 pixels per face width within the image), 16 × 16 screen-pixels (about 11 pixels per face width), and 32 × 32 screen-pixels (about 6 pixels per face width (Figure 1). (The intermediate level quan- tization value at 11 pixels/face which is an approximate equivalent of 5.5 cycles/face was chosen to be slightly lower than the 8 cycles/face spatial low-pass filtering used in [20,21] as a border value between high- and low spatial frequency filtered facial images.) The space-av- erage luminances of all stimuli images were set equal at about 40 cd/m2. Stimuli were presented on EIZO Flex- Scan T550 monitor (85 Hz refresh rate). Stimuli were presented on a computer monitor con- (a) (b) (c) Figure 1. Examples of stimuli: (a) pixel size 8 × 8 (approxi- mately 21 pixels/face); (b) pixel size 16 × 16 (approximately 11 pixels/face); (c) pixel size 32 × 32 (approximately 6 pix- els/face). In (a), all three basic varieties of configural infor- mation (first-order, holistic, second-order) are kept present; in (b), local featural information is filtered our, sec- ond-order configural information is strongly distorted, but holistic information kept present; in (c), first-order con- figural information is considerably degraded, holistic in- formation is severely degraded, and second-order con- figural information is maximally degraded if not elimi- nated  Tolerance of the ERP Signatures of Unfamiliar versus Familiar Face Perception to Spatial Quantization of Facial Images Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 202 trolled by a custom made VB program at a viewing dis- tance equal to 150 cm. The program and computer regi- men allowed necessary synchronization so that no split- ting of facial images ocurred. Synchronized with face presentation, a trigger signal was sent to the EEG re- cording system to mark the time each stimulus face was presented. All stimuli were presented in random order, each of them 10 times. (The fact that the probability of seeing a particular familiar face is different from the probability of seeing an unfamiliar face is acceptable because ERP signatures showing tuning to meaningful stimuli are not sensitive to the probability of a stimulus, but are sensitive to the pro bability of the stimulus class – [28].) Duration of the stimuli was set at 480 ms. There were 360 trials per subject. (As it is known that face-sensitive responses may decrease with stimuli repe- tition, our design can be acceptable provided that facial stimuli that have different significance and/or meaning for the subject are all similarly susceptible to this de- crease. Research based on fMRI and MEG methods has shown this to be the case – [45,46].) Subjects were in- structed to “play a game”, meaning that they knew that experimenters tried to use brain EEG-imaging to see whether they can catch if a familiar face was seen, but subjects had to conceal any possible signs of familiarity. Thus subjects were also forced to respond to each face by saying “unfamiliar”. The experiment was run in a doub le blind protocol so that experimenters who were standing by during the experiment did not know whether a famil- iar or unfamiliar face was shown at each particular trial. 2.3 EEG Recording EEG was registered by the Nexstim eXimia equipment, with EEG signals’ sampling rate 1450 Hz. For registra- tion of ERPs we used electrodes placed at Oz, O1, O2, P3, P4, T3, T4, TP7, and TP8 (international 10-10 sys- tem), with common reference at the foreh ead; in addition, EOG was registered. 2.4 Data Analysis For EEG data processing, Brain Vision Analyzer 1.05 was used. For processing the raw EEG data for ERPs, a high-cutoff 30-Hz filter was used. To obtain ERPs, EEG signal was segmented according to 900 ms peristimulus epochs (from -200 ms pre-stimulus to +700 ms post- stimulus). Eye-movement artefacts were eliminated using Brain Vision Analyzer custom Gratton and Coles algo- rithm. The EEG data for obtaining ERPs was pooled for selected regional electrodes and thus 3 conditional re- gional ERPs were computed: O (pooled electrodes O1, O2, Oz), T (electrodes T3, T4), and TP (electrodes TP7, TP8, P3, P4). ERP s were b aseline corrected (–100-0 ms). In the analysis, we concentrated on ERP components N170 and P300. 2.5 Statistical Analysis ERP components’ mean amplitude data gathered from different subjects and different experimental conditions was subjected to ANOVA, with factors spatial quantiza- tion (3 levels) and familiarity (2 levels). Main effects as well as interactions were tested for sign ifi cance. 3. Results There are no behavioral results to be reported separately from ERP results because subjects equally and system- atically answered “No” to each of the presented quan- tized faces and tried not to display any signs of possible familiarity with some of the faces. Figure 2 depicts grand average ERPs obtained from generalized regions O, T, and TP as a function of level of pixelation; ERPs are shown separately for unfamiliar faces (ERP functions on the left) and for familiar faces (ERP functions on the right). As seen from Figure 2, distinct ERP components P100, N170 and P300 are produced for quantized faces as the visual stimuli. 3.1 N170 Amplitude ERPs from all recording sites showed distinctive N170 in responses to faces. However, there were only few statis- tically significant effects involving our experimental factors. Measured from the occipital electrodes, the effect of level of pixelation proved to be significant [F(2, 34) = 6.674, P = 0.014]. The coarsest quantized facial images (6 pixels/face) were associated with the lowest N170 amplitude. The intermediate level quantized facial im- ages (11 pixels/face) were associated with at least as hight N170 amplitude as the finest level quantized facial images (21 pixels/face). Brain systems that process facial information and participate in occipital N170 generation tolerate spatial quantization of facial images up to about 11 pixels per face (along the horizontal dimension). Measured from the temporal-parietal electrodes, the ef- fect of level of pixelation on N170 was highly significant [F(2, 46) = 7.12, P = 0.006], showing that intermediate and fine quantized facial images are associated with lar- ger N170 amplitude than coarse quantized images. Inter- estingly, there was a highly significant interaction be- tween level of quantization and familiarity [F(2, 46) = 7.105, P = 0.004]. With unfamiliar faces the intermedi- ate-level quantized images lead to highest N170 ampli- tude while with familiar faces this trend was reversed. The effect of familiarity depends on pixelation level and cannot be considered as a simple additive effect. (When measured from the temporal electrodes, there were no significant main effects of pixelation or familiarity on N170 or significant interaction effects. Fo r level of pixe- lation, F(2, 22) = 2.895; for familiarity, F(1, 11) = 0.87, P = 0.371; interaction F(2, 22) = 1.274, P = 0.298.  Tolerance of the ERP Signatures of Unfamiliar versus Familiar Face Perception to Spatial Quantization of Facial Images Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 203 20 15 10 5 0 -5 -10 -15 [µV] -100 0100 200 300 400 500600[ms] OStr2pix Str3pix 15 10 5 0 -5 -10 -15 [µV] -100 0100 200 300 400500600 [ms] OFam2pix Fam3pix O-electrodes 15 10 5 0 -5 -10 -15 [µV] -100 0100 200300 400 500 600[ms] TStr2pix Str3pix 15 10 5 0 -5 -10 -15 [µV] -100 0100 200300400 500600 [ms] TFam2pix Fam3p ix TP-electrodes 20 15 10 5 0 -5 -10 -15 [µV] -100 0100 200 300 400 500600[ms] TP Str2pixStr3pix 15 10 5 0 -5 -10 -15 [µV] -100 0100 200 300 400500600 [ms] TP Fam2pix Fam3pix TP-electrodes Figure 2. Grand average ERPs registered from occipital, temporal and temporal-parietal pooled electrodes (negativity up). Distinct P100, N170 and P300 can be seen. Left column – unfamiliar; right column – familiar. For 21 pixels/face images con- dition ERPs drawn in black; for 11 pixels/face ERPs in red; for 6 pixels/face ERPs in green  Tolerance of the ERP Signatures of Unfamiliar versus Familiar Face Perception to Spatial Quantization of Facial Images Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 204 3.2 P300 Amplitude As measured from occipital electrodes, the effect of pix- elation level on P300 amplitude was highly significant [F(2, 34) = 10.644 , P = 0.002] while the effect of famili- arity was expressed as a trend [F(1, 17) = 3.871, P = 0.066]. Familiar faces lead to higher P300 amplitude. There was a highly significant interaction between level of pixelation and familiarity [F(2, 46) = 10.366, P < 0.001. With familiar faces, the finest level of pixelation lead to P300 amplitude that was distinctly larger than amplitudes for intermediate level and coarse level quan- tized images; with unfamiliar faces the finest scale and intermediate scale quantized images lead to relatively similar amplitudes of P300 whereas the P300 amplitude value stood apart from the other two quantization levels. As measured from temporal-parietal electrodes, the ef- fects were significant or highly significant: level of pixe- lation [F(2, 46) = 6.687, P = 0.006], familiarity [F(1, 23) = 6.923, P < 0.15], interaction between pixelation and familiarity [F(2, 46) = 10.366, P < 0.001]. All three lev- els of pixelation lead to mutually distinctive amplitudes of P300, with the value of amplitude being the largest, the less coarse the pixelation, but this effect was ex- pressed only with familiar faces. The P300 amplitude had a comparable magnitude for all levels of pixelation with unfamiliar faces (see also Figure 2). As measured from temporal electrodes, no significant effects of any of the factors, nor significant interaction, were found (for pixe- lation, F(2, 22) = 0.199, P = 0.773; for familiarity, F(1, 11) = 1.789, P = 0.208; interaction, F(2, 22) = 1.641, P = 0.218). 4. Discussion Our results support our hypotheses: 1) Spatially quan- tized images of faces do carry configural information which is used by brain processes to generate ERP signa- tures typical for facial image processing (e.g., N170). The coarseness range of spatial quantization capable of communicating facial configuration includes 11 pix- els/face images (an equivalent of 5.5 cycles/face) or finer. 2) Spatially quantised images of faces lead to ERP sig- natures that are sensitive to face familiarity (e.g., P300); this is despite that local featural information is filtered out, second-order configural information is distorted and that subjects try to conceal their familiarity with some of the stimuli-faces. However, the familiarity effect is relia- bly expressed when measured from the temporal-parietal electrode locations, but could not be easily obtained from the occipital and temporal electrodes. 3) There is a criti- cal level of coarseness of spatial quantization beyond which ERP signatures of processing facial images do not anymore discriminate between familiar and unfamiliar faces. The familiarity effect does not tolerate coarseness of quantization set at less than 11 pixels/face. If the square-shaped pixel size in our images was 8 × 8 screen-pixels, this amounted to about 21 pixels per face quantization (an equivalent of about 10.5 cycles/face). With this level of image detail, all three basic varieties of configural information (first-order, holistic, second-order – [6]) are kept present. (See also Figure 1.) If the pixel size was 16 × 16 screen pixels, this corresponded to about 11 pixels per face quantization (roughly 5.5 cy- cles/face). According to our evaluation, this is sufficient in order to filter out local featural information, appropri- ate for strong distortion of second-order configural in- formation, but allowing holistic information to remain present in the image. If pixel size of 32 × 32 screen pix- els was used, a quantized face image with about 6 pixels per face was created (roughly 3 cycles/face). In that case, first-order configural information is considerably de- graded, holistic information is severely degraded, and second-order configural information is maximally de- graded if not eliminated. Becaus e familiarity effects were obtained with 21- and 11- pixels-per-face images and not with 6- pixels-per-face images and because there was an interaction between ERP P300 amplitudes and familiarity, we can conclude that facial familiarity information was carried primarily by second-order configural cues. Whereas it is likely that a face is categorized as belong- ing to the class of familiar faces only after the cues that allow face individuation had been discriminated, the de- pendence of the familiarity effect on second-order con- figural processing is a viable theoretical conclusion. On the other hand, the absence of main effects of familiarity on N170 together with the sensitivity of N170 to the change of spatial quantization between 11 pixels/face and 6 pixels/face levels altogether indicate that this ERP- component is especially sensitive to the first-order con- figural cues. Some other works have supported both of these ideas [6,16,25]. It has been usually accepted that N170 is insensitive to face familiarity [16,25,26]. Our results are consistent with this in general terms. One minor exception to this rule can be noticed when we remember that there was a significant interaction between familiarity and pixelation level with temporal-parietal electrodes. Unfamiliar faces produced expected effects, showing higher N170 ampli- tude with systematically finer facial stimuli. This can be explained as better detection of facial first-order con- figural cues and also holistic templates when image de- tail gets finer and the competing structure of the square-shaped pixels’ mosaic gradually loses its distract- ing power. However, with familiar faces the finest quan- tization did not lead to a highest N170 peak amplitude. One possible explanation could assume that 11 pix- els/face and 21 pixels/face quantization levels in case of familiar faces are equally efficient for individual face  Tolerance of the ERP Signatures of Unfamiliar versus Familiar Face Perception to Spatial Quantization of Facial Images Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 205 recognition because of equal ease with which first-order facial configural representations are activated. This may be a result of formation of some habitual, automatic link between second-order featural configuration representa- tion and first-order facial templates. This speculation should be tested in specific experiments in future. Somewhat surprisingly, the finest lev el of quantization when applied to familiar faces lead to highest P300 am- plitude also as measured from the occipital electrodes (with unfamiliar faces, the finest and the intermediate level quantization yielded equal P300 amplitudes). Al- though the cortical site of this effect was surprising, the direction of the effect supported the conclusion about second-order and featural information being the basis of familiarity effects. Fine quantization level allows visual system to recognize a familiar face with high certainty, which in turn can capture attentional processes to a stronger degree. Indeed, as shown by [30], focusing at- tention on certain facial cues enhances the P300 ampli- tude. Our design presupposed repetitive presentation of fa- miliar and unfamiliar faces, appearing in random order and varying in the low-level attributes which was caused by the varying levels of quantization. This means at least two things. First, while sometimes familiar faces ap- peared successively, but even in the more often occurring cases they appeared after a few unfamiliar faces had in- tervened. Thus, this design may be appropriate for find- ing a certain definite signature of face processing that seems to be sensitive to face familiarity of successively presented faces and that presupposes parietal involve- ment -- the N400f [16]. Yet, our statistical analyses did not succeed in disentangling this component as a statisti- cally significant one (see also Figure 2). Secondly, be- cause in our experiment the same original faces, when quantized at varying levels, were depicted as different low-level images, they should have enabled generation of ERP components that are sensitive to invariant face rec- ognition with varying low-level attributes of the corre- sponding facial images. Because familiarity presupposes recognition (in addition to detection) and because some of the ERP signatures that are specific to individual face processing are image-independent (in terms of image low-level characteristics) and explicable when no more than only a few items intervene, we should be able to observe such signatures in our ERPs also. The ERP component N250r is known to satisfy the above criteria [18,27]. Unfortunately, our statistical analyses did not succeed in finding any reliable effects of N250r. On the other hand, if we observe Figure 3 where ERPs with strong parietal and temporal involvement are depicted, we see that familiar face perception is associated with a visibly stronger negativity between 200 ms and 350 ms post-stimulus (and only with fine and intermediate scale pixelation, but not with coarse quantized images). Hope- fully, subsequent studies when especially targeted on this observation could produce reliable statistical effects. 15 10 5 0 -5 -10 -15 [µV] -100 0100 200 300 400 500 600 [ms] TP7\EEG35Grand Average (a) 15 10 5 0 -5 -10 -15 [µV] -100 0100 200300 400500600 [ms] TP7\EEG35 Grand Average (b) 15 10 5 0 -5 -10 -15 [µV] -100 0100 200300 400500600 [ms] TP7\EEG35 Grand Average (c) Figure 3. ERPs recorded from TP7, depicted for fine-scale quantization; (a) intermediate level quantization; (b) and coarse-scale quantization; (c) conditions. Familiar faces – ERPs in black; unfamiliar faces – ERPs in red. With (a) and (b), familiar faces lead to some N250f-like ERP deflec- tions  Tolerance of the ERP Signatures of Unfamiliar versus Familiar Face Perception to Spatial Quantization of Facial Images Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 206 The ERPs that discriminated between familiar and un- familiar faces were found with face-image pixelation at 11 pixels/face and above, but not with 6 pixels/face im- ages. This specific value of difference when it sets the images with above 10 pixels/face quantization apart from the rest approximately corresponds to the critical pixela- tion values found in behavioural studies of face identifi- cation [39,40]. This may mean that processing familiar facial information from the spatially quantized images requires that subjects can explicitly discriminate these quantised images in terms of their facial identity. On the other hand, when gathering introspective reports from the subjects after they completed the experiment, it appeared that some of the actually familiar faces, when quantized at the intermediate level were not recognized as familiar. It should be important to carry out further studies in or- der to ascertain if ERPs could reflect face familiarity even with explicitly unreco gnized facial images. In addi- tion to theoretical significance of this question it may be valuable to solve it also for applied purposes. For exam- ple, a need may emerge to test whether a person is famil- iar with some individuals whose low-quality pho tographs are available and where, therefore, this person has no explicit awareness of what is depicted in the picture. An- other applied aspect related to our results is ev en simpler: we have shown that spatially quantized (pixelated) im- ages can be used for registration and analysis of face- sensitive ERPs. This in itself is encouraging. 5. Conclusions As was stated in the introductory part, spatial quantiza- tion is an image transform with effects ranging beyond simple spatial-frequency filtering. The structure of the square-shaped pixels with their square-corners, square- edges and formal aspects of the mosaic of square-shapes provides a visual structure that 1) masks facial configural cues and 2) sets visual system at the competing demands of image interpretation – a face versus a mosaic. In these circumstances there are no strong a priori foundations to expect an inevitable capability of the visual processing system to extract face-specific information sufficient for generation of known face-specific and/or face-sensitive ERP signatures on the face of the pixelised masking structure. Our study showed that spatial quantization does not make an obstacle for the emergence of ERP- signs of facial processing, including the ones sen sitive to face familiarity. However, this sensitivity has its limits so that with pixelation coarseness approaching 6 pixels per face, familiarity effects on ERP disappear. 6. Acknowledgements We are grateful to Jaan Aru for his substantial help dur- ing preparation of this report. REFERENCES [1] V. Bruce and A. Young, “In the Eye of the Beholder: The Science of Face Perception,” Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1998. [2] A. M. Burton, S. Wilson, M. Cowan and V. Bruce, “Face Recognition in Poor-Quality Video,” Psychological Sci- ence, Vol. 10, No. 3, 1999, pp. 243-248. [3] T. A. Busey and G. R. Loftus, “Cognitive Science and the Law,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Vol. 11, No. 3, 2007, pp. 111-117. [4] C. G. Gross, “Processing the Facial Image: A Brief His- tory,” American Psychologist, Vol. 60, No. 8, 2005, pp. 755-763. [5] S. Z. Li and A. K. Jain, “Handbook of Face Recognition,” Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 2005. [6] D. Maurer, R. Le Grand and C. J. Mondloch, “The Many Faces of Configural Processing,” Trends in Cognitive Sci- ences, Vol. 6, No. 6, 2002, pp. 255-260. [7] C. Peacock, A. Goode and A. Brett, “Automatic Forensic Face Recognition from Digital Images,” Science and Jus- tice, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2004, pp. 29-34. [8] P. Quintiliano and A. Rosa, “Face Recognition Applied to Computer Forensics,” International Journal of Forensic Computer Science, Vol. 1, 2006, pp. 19-27. [9] S. S. Rakover and B. Cahlon, “Face Recognition: Cogni- tive and Computational Processes,” John Benjamins Pub- lishing, Amsterdam, 2001. [10] A. Schwaninger, C. Wallraven, D. W. Cunningham and S. D. Chiller-Glaus, “Processing of Facial Identity and Ex- pression: A Psychophysical, Physiological and Computa- tional Perspective,” Progress in Brain Research, Vol. 156, 2006, pp. 321-343. [11] P. Sinha, “Recognizing Complex Patterns,” Nature Neuro- science Supplement, Vol. 5, 2002, pp. 1093-1097. [12] M.-H. Yang, D. J. Kriegman and N. Ahuja, “Detecting Faces in Images: A Survey,” IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, Vol. 24, No. 1, 2002, pp. 34-58. [13] T. H. Allison, G. Ginter, A. C. McCarthy, A. Nobre, M. Puce, D. Luby and D. D. Spencer, “Face Recognition in Human Extrastriate Cortex,” Journal of Neurophysiology, Vol. 71, No. 2, 1994, pp. 821-825. [14] S. G. Boehm and W. Sommer, “Neural Correlates of In- tentional and Incidental Recognition of Famous Faces,” Cognitive Brain Research, Vol. 23, No. 2-3, 2 005, pp. 153- 163. [15] M. Eimer and R. A. McCarthy , “Prosopagnosia and Struc- tural Encoding of Faces: Evidence from Event-Related Potentials,” NeuroReport, Vol. 10, No. 2, 1999, pp. 255- 259. [16] M. Eimer, “Event-Realted Brain Potentials Distinguish Processing Stages Involved in Face Perception and Rec- ognition,” Clinical Neuropysiology, Vol. 111, No. 4, 2000,  Tolerance of the ERP Signatures of Unfamiliar versus Familiar Face Perception to Spatial Quantization of Facial Images Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 207 pp. 694-705. [17] A. Holmes, J. S. Winston and M. Eimer, “The Role of Spatial Frequency Information for ERP Components Sen- sitive to Faces and Emotional Facial Expression,” Cogni- tive B rain Research , Vol. 25, No. 2, 2005, pp. 508-520. [18] S. R. Schweinberger, E. C. Pickering, I. Jentzsch, A. M. Burton and J. M. Kaufmann, “Event Related Potential Evidence for a Response of Interior Temporal Cortex to Familiar Face Repetitions,” Cognitive Brain Research, Vol. 14, 2002, pp. 398-409. [19] S. Bentin, T. Allison, A. Puce, E. Perez and G. McCarthy, “Electrophysiological Studies of Face Perception in Hu- mans,” Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, Vol. 8, No. 6, 1996, pp. 551-565. [20] V. Goffaux, I. Gauthier and B. Rossion, “Spatial Scale Contribution to Early Visual Differences between Face and Object Processing,” Cognitive Brain Research, Vol. 16, No. 3, 2003, pp. 416-424. [21] V. Goffaux, B. Jemel, C. Jacques, B. Rossion and P. G. Schyns, “ERP Evidence for Task Modulations on Face Perceptual Processing at Different Spatial Scales,” Cogni- tive Science, Vol. 27, No. 2, 2003, pp. 313-325. [22] B. Rossion, I. Gauthier, M. J. Tarr, P. A. Despland, R. Bruyer, S. Linotte and M. Crommelinck, “The N170 Oc- cipito-Temporal Component is Enhanced and Delayed to Inverted Faces but not to Inverted Objects: An Electro- physiological Account of Face-Specific Processes in the Human Brain,” Neuroreport, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2000, pp. 69-74. [23] G. A. Rousselet, M. J. Macé and M. Fabre-Thrope, “Ani- mal and Human Faces in Natural Scenes: How Specific to Human Faces is the N170 ERP Component?” Journal of Vision, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2004, pp. 13-21. [24] J. M. Kaufmann and S. R. Schweinberger, “Distortions in the Brain? ERP Effects of Caricaturing Familiar and Un- familiar Faces,” Brain Research, Vol. 1228, 2008, pp. 177-188. [25] S. Bentin and S. Y. Deouell, “Structural Encoding and Identification in Face Processing: ERP Evidence for Separate Mechanisms,” Cognitive Neuropsychology, Vol. 17, No. 1-3, 2000, pp. 35-54. [26] B. Rossion, S. Campanella, C. M. Gomez, A. Delinte, D. Debatisse, L. Liard, S. Dubois, R. Bruyer, M. Crom- melinck and J.-M. Guérit, “Task Modulation of Brain Ac- tivity Related to Familiar and Unfamiliar Face Processing: An ERP Study,” Clinical Neurophysiology, Vol. 110, No. 3, 1999, pp. 449-462. [27] M. Bindemann, A. M. Burton, H. Leuthold and S. R. Schweinberger, “Brain Potential Correlates of Face Rec- ognition: Geometric Distortions and the N250r Brain Re- sponse to Stimulus Repetitions,” Psychophysiology, Vol. 45, No. 4, 2008, pp. 535-544. [28] S. J. Luck, “An Introduction to the Event-Related Poten- tial Technique,” MIT Press, Cambridge, 2005. [29] J. Polich and J. R. Criado, “Neuropsychology and Neu- ropharmacology of P3a and P3b,” International Journal of Psychophysiology, Vol. 60, No. 2, 2006, pp. 172-185. [30] R. N. Henson, Y. Goshen-Gottstein, T. Ganel, L. J. Otten, A. Quayle and M. D. Rugg, “Electrophysiological and Haemodynamic Correlates of Face Perception, Recogni- tion and Priming,” Cerebral Cortex, Vol. 13, No. 7, 2003, pp. 793-805. [31] E. Mercure, F. Dick and M. H. Johnson, “Featural and Configural Face Processing Differentially Modulate ERP Components,” Brain Research, Vol. 1239, 2008, pp. 162- 170. [32] E. I. Olivares and J. Iglesias, “Brain Potentials and Inte- gration of External and Internal Features into Face Rep- resentations,” International Journal of Psychophysiology, Vol. 68, No. 1, 2008, pp. 59-69. [33] J. P. Rosenfeld, J. R. Biroschak and J. J. Furedy, “P300- Based Detection of Concealed Autobiographical versus In- cidentally Acquired Information in Target and Non-Tar- get Paradigms,” International Journal of Psychophysiol- ogy, Vol. 60, No. 3, 2006, pp. 251-259. [34] A. Ishai, C. F. Schmidt and P. Boesiger, “Face Perception is Mediated by a Distributed Cortical Network,” Brain Research Bulletin, Vol. 67, No. 1-2, 2005, pp. 87-93. [35] H. Halit, M. de Haan, P. G. Schyns and M. H. Johnson, “Is High-Spatial Frequency Information Used in the Early Stages of Face Detection?” Brain Research, Vol. 1117, No. 1, 2006, pp. 154-161. [36] A. V. Flevaris, L. C. Robertson and S. Bentin, “Using Spatial Frequency Scales for Processing Face Features and Face Configuration: An ERP Analysis,” Brain Re- search, Vol. 1194, 2008, pp. 100-109. [37] T. Nakashima, K. Kaneko, Y. Goto, T. Abe, T. Mitsudo, K. Ogata, A. Makinouchi and S. Tobimatsu, “Early ERP Components Differentially Extract Facial Features: Evi- dence for Spatial Frequency-and-Contrast Detectors,” Neu- roscience Research, Vol. 62, No. 4, 2008, pp. 225-235. [38] G. A. Rousselet, J. S. Husk, P. J. Bennett and A. B. Se- kuler, “Time Course and Robustness of ERP Object and Face Differences,” Journal of Visi on, Vol. 8, No. 12, 2008, pp. 1-18. [39] T. Bachmann, “Identification of Spatially Quantised Tach- istoscopic Images of Faces: How Many Pixels does it Take to Carry Identity?” European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, Vol. 3, No. 1, 1991, pp. 87-103. [40] S. K. Bhatia, V. Lakshminarayanan, A. Samal and G. V. Welland, “Human Face Perception in Degraded Images,” Journal of Visual Communication and Image Represen- tation, Vol. 6, No. 3, 1995, pp. 280-295. [41] N. P. Costen, D. M. Parker and I. Craw, “Spatial Content and Spatial Quantisation Effects in Face Recognition,” Perception, Vol. 23, No. 2, 1994, pp. 129-146. [42] L. D. Harmon and B. Julesz, “Masking in Visual Reco- gnition: Effects of Two-Dimensional Filtered Noise,” Science, Vol. 180, No. 4091, 1973, pp. 1194-1197.  Tolerance of the ERP Signatures of Unfamiliar versus Familiar Face Perception to Spatial Quantization of Facial Images Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 208 [43] K. Lander, V. Bruce and H. Hill, “Evaluating the Effec- tiveness of Pixelation and Blurring on Masking the Iden- tity of Familiar Faces,” Applied Cognitive Psychology, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2001, pp. 101-116. [44] E. J. Ward, “Effects of Two-Dimensional Noise and Fea- ture Configuration on the Recognition of Faces in Capu- chin Monkeys (Cebus apella),” Biological Foundations of Behavior: 490 Honors Thesis, Franklin & Marshall Col- lege, Lancaster, 2007. [45] H. Fischer, C. I. Wright, P. J. Whalen, S. C. McInerney, L. M. Shin and S. L. Rauch, “Brain Habituation during Re- peated Exposure to Fearful and Neutral Faces: A Func- tional MRI Study,” Brain Research Bulletin, Vol. 59, No. 5, 2003, pp. 387-392. [46] A. Ishai, P. C. Bikle and L. G. Ungerleider, “Temporal Dynamics of Face Repetition Suppression,” Brain Re- search Bulletin, Vol. 70, No. 4-6, 2006, pp. 289-295. |