Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

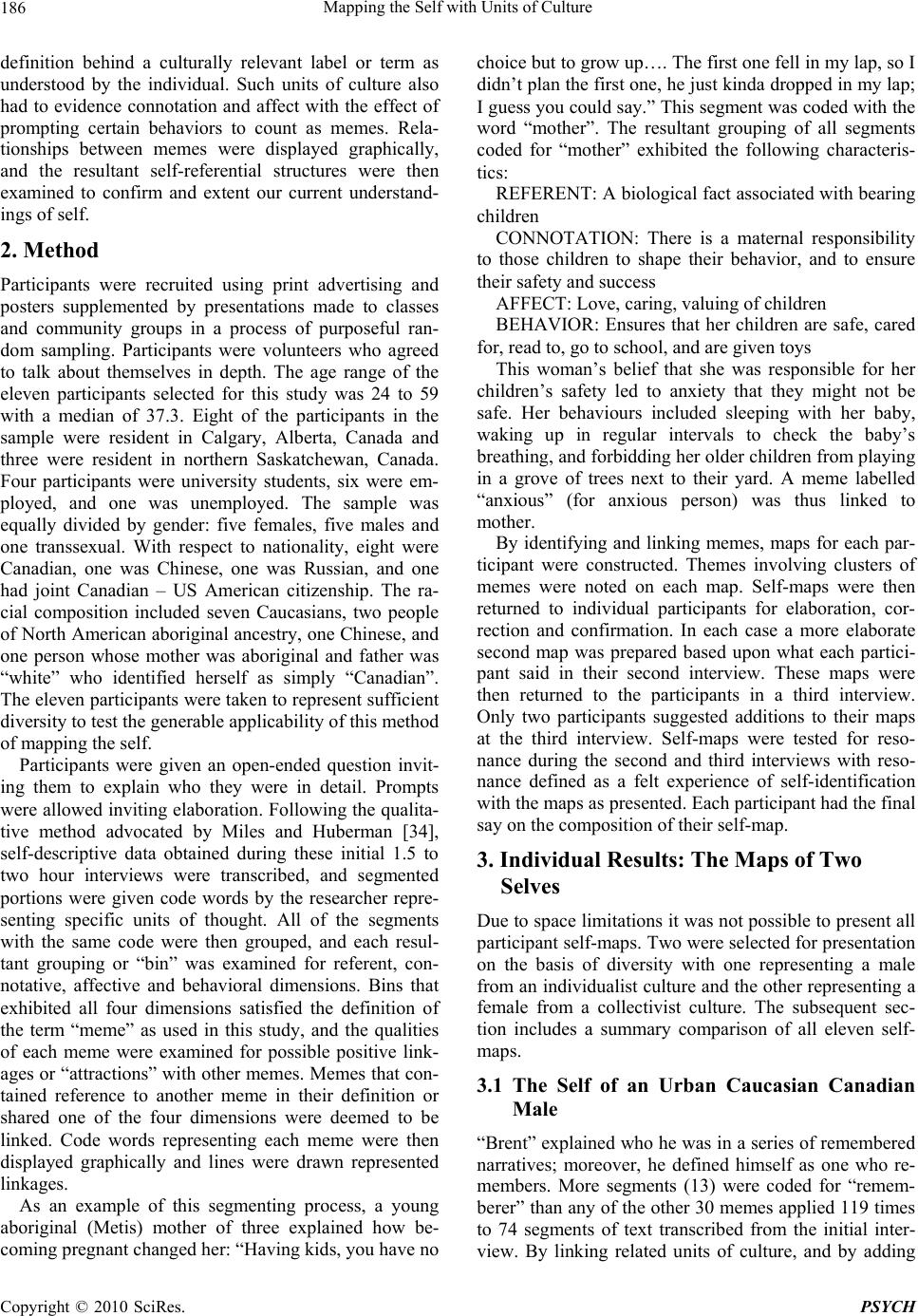

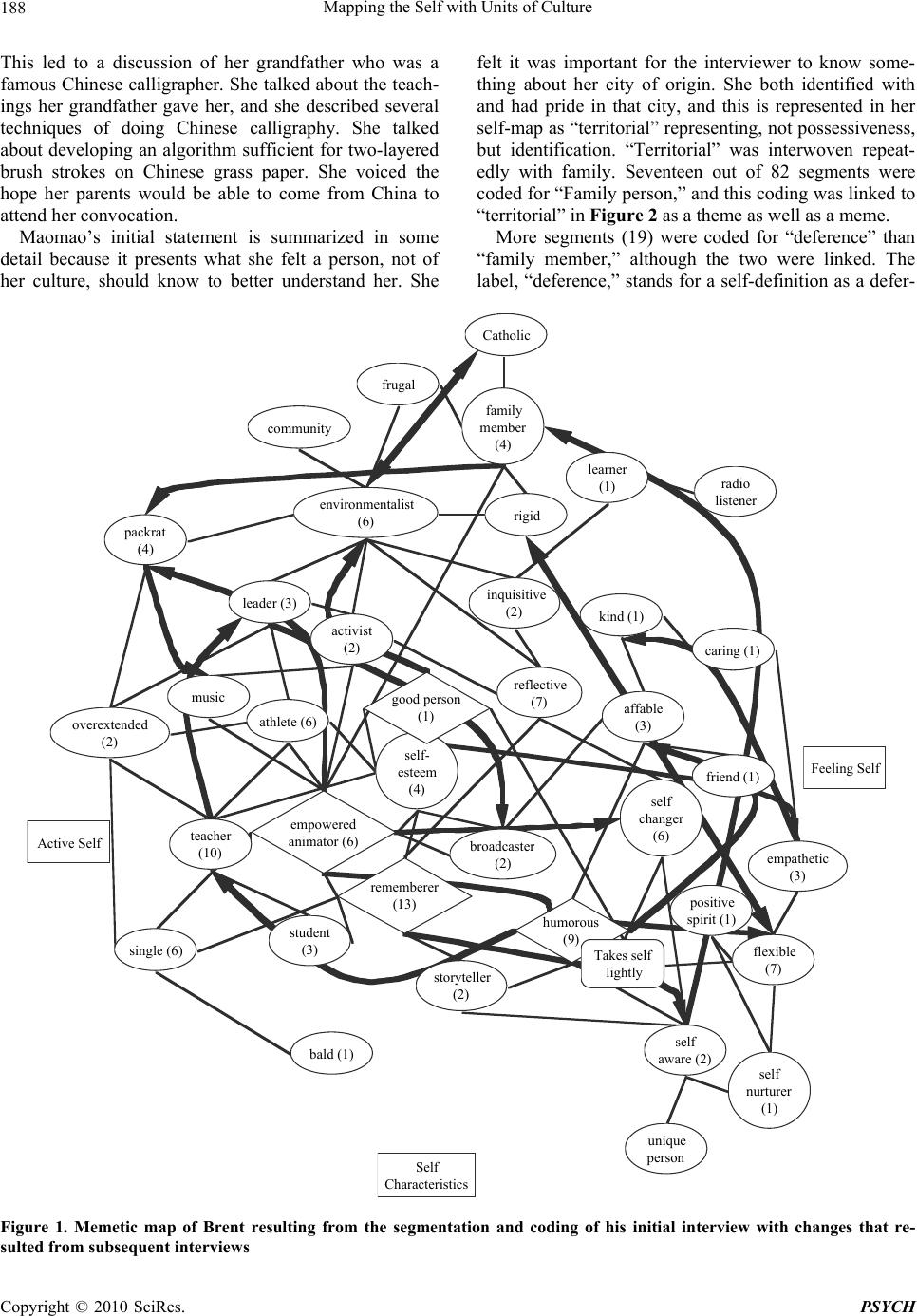

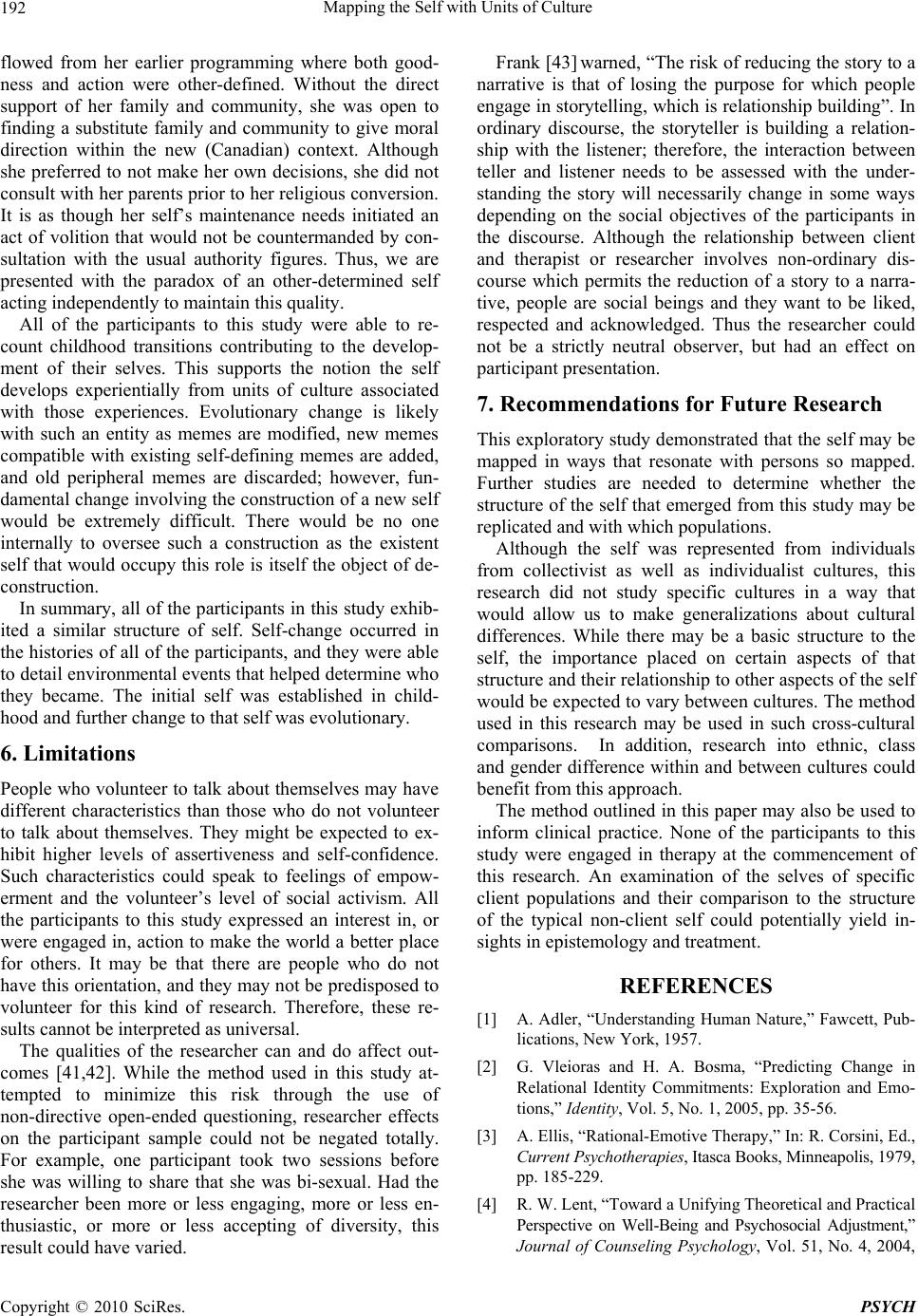

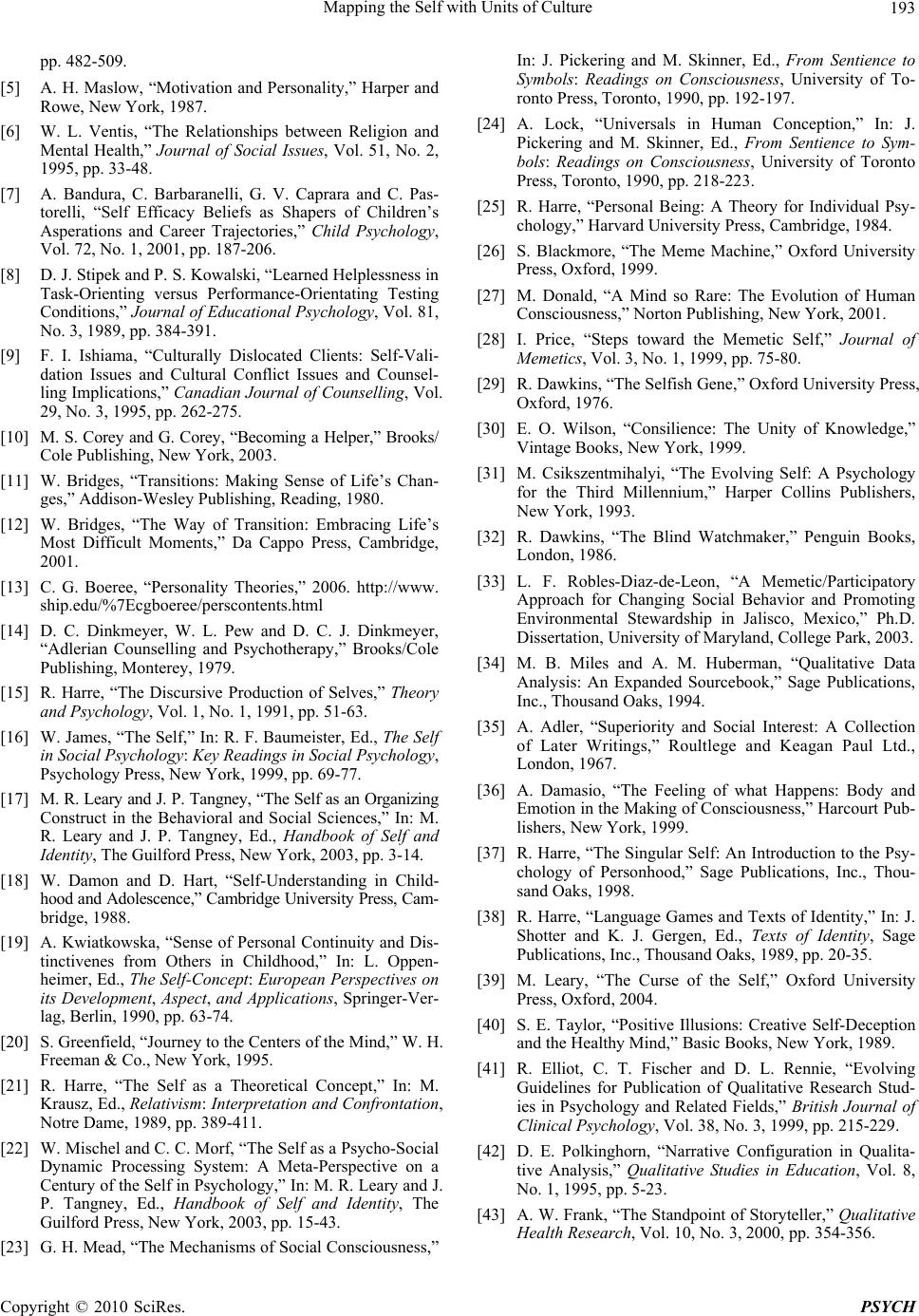

Psychology, 2010, 1: 185-193 doi:10.4236/psych.2010.13025 Published Online August 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 185 Mapping the Self with Units of Culture Lloyd H. Robertson Northlands College, La Ronge, Canada. Email: Lloyd@hawkeyeassociates.ca Received May 10th, 2010; revised June 9th, 2010; accepted June 11th, 2010. ABSTRACT This study explored a method of representing the self graphically using elemental units of culture called memes. A di- verse sample of eleven volunteers participated in the co-construction of individual “self-maps” during a series of inter- views over a nine month period. Two of the resultant maps are presented as exemplars. Commonalities found in all eleven maps lend support to the notion that there are certain structures to the self that are cross-cultural. The use of memes in mapping those structures was consid ered useful but insufficient b ecause emotive elements to the self emerg ed from the research that could not be represented in memetic form. Suggestions are made for future research. Keywords: Culture, Identity, Memes, Self, Self-Structure 1. Introduction Psychologists have discussed many aspects of the self including self-concept [1,2], self-esteem [3,4], self-actu- alization [5,6], self-efficacy [7,8], and self-validation [9]. Eric Erikson said, “The ability to form intimate relation- ships depends largely on having a clear sense of self” [10]. William Bridges [11,12] tied his theory of adult transition to changes in this “self”. Alfred Adler placed the self at the core of “world view” [1], and Adlerians continue to emphasize social interest, intimacy and pro- duction in planning for self-change [13,14] Despite its central importance to psychology, little has been done to empirically detail and map the core concept of self. Rom Harre [15] despaired at the difficulties inherent in such a study: “The self that manages and monitors its own actions and thoughts is never disclosed as such to the person whose Self (sic) it is. It is protected from even the possi- bility of being studied empirically by its very nature. Whenever it tries to catch a glimpse of itself it must be- come invisible to itself, since it is that very self which would have to catch that very glimpse. It is known only through reason. It is never presented in experience.” William James [16] postulated the existence of an ob- jective “me” that included physical, active, social and psychological components coupled with a subjective “I” that included qualities of volition, constancy and dis- tinctness. The Jamesian “I” and “me” were seen to be different sides of a unitary self that could at once observe and be observed, and it has become the basis of much research into the self [17-19]. Since the Jamesian self includes that which may be seen to be me, and that which Harre had difficulty seeing, it remains an encompassing definition. If the self is defined as a cognitive structure [20-22], then it is necessarily a cultural construct [23-25] which could be understood as consisting of units of culture [26-28]. Culture, in this sense, co nsists of all the ways of knowing, interpreting and doing that proliferate within a given society. Dawkins’ [29] coined the term “meme” representing elemental cultural units that exhibit attrac- tive and repellent properties with respect to other such units. Similar terms for such units have been proposed from a variety of disciplines including “mnemotype”, “idene”, “sociogene”, “concept” and “culturgen” [30], but the term “meme” has increasingly come to predomi- nate and is used in this paper. Blackmore [26] suggested that the self is an interlock- ing complex of memes, but she did not attempt to illus- trate how this self may be structured. There has been agreement, however, that memes include cognitive and behavioral dimensions [31-33]. It would be reasonable to infer that affective and connotative meanings associated with each meme as held within the mind of the individual would be the source of Dawkins’ [29] attractive and re- pellent “properties,” which could then result in self- structures that may be displayed graphically. Thus, in this exploratory study the term “meme” re- ferred to an elemental unit of culture that exhibits refer- ent, connotative, affective and behavioral properties. “Referent” refers to the dictionary-like idea, concept or  Mapping the Self with Units of Culture 186 definition behind a culturally relevant label or term as understood by the individual. Such units of culture also had to evidence connotation and affect with the effect of prompting certain behaviors to count as memes. Rela- tionships between memes were displayed graphically, and the resultant self-referential structures were then examined to confirm and extent our current understand- ings of self. 2. Method Participants were recruited using print advertising and posters supplemented by presentations made to classes and community groups in a process of purposeful ran- dom sampling. Participants were volunteers who agreed to talk about themselves in depth. The age range of the eleven participants selected for this study was 24 to 59 with a median of 37.3. Eight of the participants in the sample were resident in Calgary, Alberta, Canada and three were resident in northern Saskatchewan, Canada. Four participants were university students, six were em- ployed, and one was unemployed. The sample was equally divided by gender: five females, five males and one transsexual. With respect to nationality, eight were Canadian, one was Chinese, one was Russian, and one had joint Canadian – US American citizenship. The ra- cial composition included seven Caucasians, two people of North American aboriginal ancestry, one Chinese, and one person whose mother was aboriginal and father was “white” who identified herself as simply “Canadian”. The eleven participants were taken to represent sufficient diversity to test the generable app licability o f th is method of mapping the self. Participants were given an open-ended question invit- ing them to explain who they were in detail. Prompts were allowed inviting elaboration . Following the qualita- tive method advocated by Miles and Huberman [34], self-descriptive data obtained during these initial 1.5 to two hour interviews were transcribed, and segmented portions were given code words by the researcher repre- senting specific units of thought. All of the segments with the same code were then grouped, and each resul- tant grouping or “bin” was examined for referent, con- notative, affective and behavioral dimensions. Bins that exhibited all four dimensions satisfied the definition of the term “meme” as used in this study, and the qualities of each meme were examined for possible positive link- ages or “attractions” with other memes. Memes that con- tained reference to another meme in their definition or shared one of the four dimensions were deemed to be linked. Code words representing each meme were then displayed graphically and lines were drawn represented linkages. As an example of this segmenting process, a young aboriginal (Metis) mother of three explained how be- coming pregnant changed her: “Having kids, you have no choice but to grow up…. The first on e fell in my lap, so I didn’t plan the first one, he just kinda dropped in my lap; I guess you could say.” This segment was coded with the word “mother”. The resultant grouping of all segments coded for “mother” exhibited the following characteris- tics: REFERENT: A biological fact associated with bearing children CONNOTATION: There is a maternal responsibility to those children to shape their behavior, and to ensure their safety and success AFFECT: Love, caring, valuing of children BEHAVIOR: Ensures that her children are safe, cared for, read to, go to school, and are given toys This woman’s belief that she was responsible for her children’s safety led to anxiety that they might not be safe. Her behaviours included sleeping with her baby, waking up in regular intervals to check the baby’s breathing, and forbidding her older children from playing in a grove of trees next to their yard. A meme labelled “anxious” (for anxious person) was thus linked to mother. By identifying and linking memes, maps for each par- ticipant were constructed. Themes involving clusters of memes were noted on each map. Self-maps were then returned to individual participants for elaboration, cor- rection and confirmation. In each case a more elaborate second map was prepared based upon what each partici- pant said in their second interview. These maps were then returned to the participants in a third interview. Only two participants suggested additions to their maps at the third interview. Self-maps were tested for reso- nance during the second and third interviews with reso- nance defined as a felt experience of self-identification with the maps as presented. Each participant had the final say on the composition of their self-map. 3. Individual Results: The Maps of Two Selves Due to space limitations it was not possible to present all participant self-maps. Two were selected for presen tation on the basis of diversity with one representing a male from an individualist culture and the other representing a female from a collectivist culture. The subsequent sec- tion includes a summary comparison of all eleven self- maps. 3.1 The Self of an Urban Caucasian Canadian Male “Brent” explained who he was in a series of remembered narratives; moreover, he defined himself as one who re- members. More segments (13) were coded for “remem- berer” than any of the other 30 memes applied 119 times to 74 segments of text transcribed from the initial inter- view. By linking related units of culture, and by adding Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Mapping the Self with Units of Culture 187 thematic interpretive understandings, the complex struc- ture of interlocking memes illustrated in Figure 1emer- ged with “rememberer” pictured as a diamond so as to highlight its importan ce as a theme in his life. Links were drawn connecting it with “reflective”, “animator”, “stu- dent”, “storyteller” and “self-changer” memes, and a thematic arrowed line was drawn to other aspects of himself on which he reflected including: “self-aware”, “friend”, “caring”, “family member” and “packrat”. The numbers beside the name of each meme in Figure 1 refer to the number of segments coded for that meme during the initial interview. Memes without numbers were added during subsequent interviews. Memes linked to adjoining memes shared some connotative, affective or behavioral quality. For example, “self aware” is linked to “storyteller” because it is through the process of telling stories Brent became more self-aware. In addition to linked memes, themes were generated that linked larger portions of the self-map. Such themes included “humor- ous/takes self lightly”, “empowered animator” and “good person”. Themes emerged from the data and are repre- sented in rectangle form. Broad arrows were drawn from these themes to related memes. For example, Brent dis- played his empowerment through his work as a broad- caster and his capacity for self-change; therefore, an ar- row was drawn connecting these to memes with “em- powerment”. Similarly, the theme of taking himself lightly was woven, behaviourally with self-depreciating humour, into his roles as a student, teacher, friend, leader and broadcaster. Brent defined himself as both “rigid” and “flexible”. Tension between these two memes is displayed with a double headed arrow connecting the two. Similarly, memes for “Catholic” and “environmentalist” were also defined by Brent as in conflict. After reviewing his initial map, Brent suggested that he consisted of three “selves:” “self characteristics” consisting of relatively stable phy- sical and psychological features, a feeling or emotional self, and a self defined through activity. He said that at any given moment, all of these “selves” would likely be operative and that his feelings and emotions would trig- ger other aspects of himself. A map is necessarily a static representation, but the self as experienced by Brent was a changing entity. For example, Brent recounted his attempt to understand the action of a former girlfriend who had ended their rela- tionship af ter she saw his house. He reso lved to deal with some aspects of his “packrat” behaviours that she found off-putting. He saw this as evidence of a new “flexible” self, and this flexibility was subsequently applied to how he judged others. The meme labelled “self-esteem” represents a belief in the value of working on this aspect of the self through positive self-affirmations, recorded and reviewed posi- tive memories and positive think ing. Brent exp lained th at he had not developed the level of self-esteem he needed to pursue his career until he was well into adu lthood, and he attributed his new emphasis on self-esteem to the sus- tained intervention of a significant other who provided him with evidence of previously unrecognized capabili- ties. Brent identified the theme “good person” during our second interview while reflecting on an initial version of his self-map. He said his motivation to understand others flowed from a desire to continue to see himself as a good person, and this was reflected in his “activist”, “envi- ronmentalist”, “positive spirit”, “empathetic”, “friend”, “caring” and “kind” memes. Brent also added “Catholic”, “rigid”, “radio listener” and “music” to his self-map at this interview. Although he was born Catholic, he did not consider himself devout, but he needed a letter from a priest so that he could ob- tain a position as a teacher. He traced his tendency to being rigid and uncompromising to his family of origin which he described as “very oppressive”. Hence, a link was drawn between “rigid” and “family member”. Brent’s third interview resulted in the addition of just one additional meme to his self-map, “frugal”. He said his frugality came from his parents who were “too con- cerned with saving.” Brent saw himself as frugal with both time and money. He said that for 7 years he did not have a television, and he felt good about this decision, but the internet had now replaced the potential television had for unprofitably occupying his time. Signs of Brent’s frugality had (after the initial interview) been interpreted as a function of his environmental concern for the planet, but this new information suggested that his frugality with respect to the purchase of possessions and the expendi- ture of his time constituted an ethic related to his up- bringing. Although compatible with environmental ac- tivism, such frugality could exist independently. Thus, a meme for frugal was added to a third version of Brent’s self-map linked to both “family” and “environmental- ism”. 3.2 A Woman from the Interior of China “Maomao” was a single woman in her twenties who, at the beginning of this study, was a student at a Canadian university. She responded to the invitation to tell the re- searcher about herself by talking about the city in which she was born and raised. She said she was from the mid- dle city of the middle province of China. She mentioned with apparent pride that this city had been the capital of ancient China on thirteen separate occasions, and she described several local historic and cultural attractions. She also talked about her parents, her extended family and each of their occupations. She went into some detail about her elementary, middle years and university educa- tion. She talked about her university thesis involving the application of computer graphics to Chinese calligraphy. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Mapping the Self with Units of Culture Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 188 This led to a discussion of her grandfather who was a famous Chinese calligrapher. She talked about the teach- ings her grandfather gave her, and she described several techniques of doing Chinese calligraphy. She talked about developing an algorithm sufficient for two-layered brush strokes on Chinese grass paper. She voiced the hope her parents would be able to come from China to attend her con vocat ion. Maomao’s initial statement is summarized in some detail because it presents what she felt a person, not of her culture, should know to better understand her. She felt it was important for the interviewer to know some- thing about her city of origin. She both identified with and had pride in that city, and this is represented in her self-map as “territorial” representing, not possessiveness, but identification. “Territorial” was interwoven repeat- edly with family. Seventeen out of 82 segments were coded for “Family person,” and this coding was linked to “territorial” in Figure 2 as a theme as well as a meme. More segments (19) were coded for “deference” than “family member,” although the two were linked. The label, “deference,” stands for a self-definition as a defer- activist (2) reflective (7) affable (3) friend (1) empowered animator (6) athlete (6) humorous (9) inquisitive (2) kind (1) rememberer (13) single (6) leader (3) teacher (10) overextended (2) storyteller (2) self- esteem (4) bald (1) broadcaster (2) caring (1) Takes self lightly empathetic (3) flexible (7) environmentalist (6) packrat (4) family member (4) self changer (6) self aware (2)self nurturer (1) good person (1) learner (1) student (3) Active Self Feeling Self Self Characteristics positive spirit (1) community Catholic radio listener unique person rigid music frugal Figure 1. Memetic map of Brent resulting from the segmentation and coding of his initial interview with changes that re- sulted from subsequent interviews  Mapping the Self with Units of Culture 189 Love of, pride in parents and dog, background (including home city) is a constant that will never change angry (5) deferent (19) self- centered (4) self- critical (4) animator (4) caring (1)pet lover (12) daughter (14) family person (17) student (14) only child (3) territorial (6) friend (3) rememberer (7) reflective (2) metaphor maker (2) self aware (1) self change (5) dreamer (1) environmentally driven (2) story teller (1) inquisitive (2) traveler (2) unique experiencer (1) Active Self Passive Self worker Christian Figure 2. Memetic map of Maomao resulting from the segmentation and coding of her initial interview with revisions from subsequent interviews ent person, someone who submits to the decisions of significant others. Maomao said even small decisions, such as what to wear, were made by her parents prior to her leaving home. She did not like th e subject they chose for her to study at un iversity, but she complied. Maomao panicked during her first two days in Canada because she had no ready access to her parents, but with the help of her landlord she obtained a cell phone and a computer, and the parental contact was re-established. She reported, “I still cannot make decision, so found like before, I want to listen to the command.” When the decision of a sig- nificant other differs from her wishes, she feels sadness, but when peers enforce a decision she does not like, she feels anger. Paradoxically, Maomao reported an ability to make independent decisions. As an undergraduate student in Beijing she bought a dog. Added significance accrued to Maomao’s first recalled independent act because her fa- ther was not fond of dogs. None-the-less, she was able to convince her parents to accept the dog when she returned from Beijing, and when she left for Canada she entrusted them with the dog’s care. Maomao displayed a tendency to be self-critical by blaming herself for the death of her dog even though she was not in the country at the time. She also derided herself for her difficulty in making de- cisions, for displaying anger, and for being impatient. Maomao displayed volition by devising a plan to go back to her old university in China before letting her parents know that she was returning. With this ruse, her parents would not have an opportunity to insist that she spend all her time in her home city. She explained, “The thing is, I cannot ask my parents exactly what I want Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Mapping the Self with Units of Culture 190 because they would not allow me to do something, and I am old enough, I think.” Maomao’s account suggested potential conflict be- tween her “animator” and “deferent” memes. This ten- sion was pictured in Figure 2 by a double-headed arrow representing repulsion. A similar tension line is pictured between “friend” and “self-centered,” and between “self change” and “environmentally driven.” These lines of tension display a conflict between her passive and active selves. On reviewing the self-map created from her first inter- view, Maomao said her passive self was far more promi- nent than her active self, and she referred to herself as a “robot”. She suggested that the meme “environmentally driven” should be represented centrally in her map. The animator meme remained imbedded in Maomao’s self- definition as she reported a capacity to act independ- ently under certain circumstances, and she resented her desire for direction. The possibility that such resent- ment was a cross-cultural effect was explored, but she said she also had this robot-like feeling before coming to Canada. By the second interview, Maomao was working and had her own apartment. She had complained, during the first interview, that the Canadian family with which she had stayed drank alcohol too much, but she had made some “church friends” who did not drink. Maomao said she now considered herself to be a Christian. The “church people” taught her to pray, and she said she found prayer to be helpful when stressed. As a result of this information, a new meme for “Christian” was added to her map linked to “self-changer” and “caring”. Maomao reviewed her revised memetic self-map ap- proximately two months after her second interview. She said she felt comfortable in a passive role, but she can, with effort, be self-activated. Although she realized that she can make decisions on her own, she said she prefers not to do so. Being deferent allows her to do other things because she does not have to take the time to gather all the information she needs to make good decisions. 4. Collective Results Self-maps for each of the eleven participants were pre- pared and refined using the method described. Seven participants said the maps reflected who they were at a feeling level on the second interview. Th is point of reso- nance was reported by ten participants by the third inter- view. All eleven self-maps included elements of volition, constancy, distinctness, and feeling. In addition, two as- pects of the Jamesian objective self, “active” and “psy- chological” were found in the maps of all of the partici- pants. All participants agreed that their self changed over time, and all related self-change to transitional events. Three of the participants said they undertook planned self-transitions during the course of this study. All of the participants voiced narratives as to how they overcame adversity in becoming who they were. They also recalled initiating developmental changes to them- selves. For example, eight reported changing their reli- gious beliefs motivated by a desire to become better peo- ple in some ways. Six of these rejected Christianity with three becoming atheists, two embracing Aboriginal Spirituality and one becoming a theist without attach- ment to a recognized religion. One participant (Maomao) was raised as an atheist but subsequently became Chris- tian. The remaining individual (Brent) rejected Catholi- cism, but then made a personal accommodation with it related to obtaining employment. The remaining three participants who did not change religious belief told sto- ries of how they had initiated change to become better parents and/or spouses. Despite a propensity toward self-change, all partici- pants reported a feeling that they were the same person over time, although two noted that this feeling of con- stancy could be illusory. Every participant was able to narrate childhood experiences helping to determine who they became, and those memories contributed to the feeling of constancy. For example, one aboriginal par- ticipant explained that regardless of future changes, his memories would remind him that he is the same person who grew up in an underprivileged neighbourhood of a small Saskatchewan city. Nine other participants also presented with the act of remembering developed into either a meme or theme, and all participants engaged in the act of remembering when explaining who they were. The Alderian [35] self-components of work, love and social interest were found in all self-maps. Every par- ticipant named aspects of themselves related to work or production, and love or intimacy. All eleven participants engaged in activities satisfying Adler’s notion of social interest, and six of these related their activities to a tran- scendental purpose – the need to serve a purpose or cause greater than themselves. Four of these six identified themselves as theists and two identified themselves as atheists. The self-maps of ten participants contained memes associated with family, and six of these contained memes indicating a connection with community. Those that in- corporated identification with a community in their self maps identified a formal community, as Maomo did in identifying with a Chinese Christian community. Others, such as a bi-sexual female whose friendship group in- cluded males, lesbians and other bi-sexuals, created their own informal supportive community of friends not iden- tified as communities on their self-maps. One person failed to incorporate eith er family or community into her self-map, but she said that the support she had received from her local Unitarian Church was important in her acceptance of her transsexuality. Although a meme for Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Mapping the Self with Units of Culture 191 “Unitarian” could have been developed, this was not how she identified herself; however, as with o ther participants, she had found a community of people who accep ted her. All of the participants said there was some quality or qualities essential to be being human, with emotions be- ing the most often mentioned such quality. Seven par- ticipants had human feelings or emotions represented at the base of their self-maps, and one of these labelled this base “the feeling of me”. The remaining four had feel- ings represented in their self-maps as themes. One of these (Brent) identified a group of memes he described as his “feeling self”, but he explained that emotions perme- ated his entire being. 5. Discussion Memes were used to illustrate relationships between cul- ture and interconnected units of self that comprised the self-definitions of participants. Participant insistence on including recognition of emotion in their self-maps, be- yond the emotive component of individual memes, was unanticipated. Thus, memes may be a necessary but in- sufficient component in mapping the self. It may be that a feeling of self, with its origins in the organism mapping its body states, drives the creation of an autobiographical self [36]. On the other hand, many organisms are capable of reactive feelings based on their body states without ever achieving self-consciousness. Therefore, the possi- bility that the self is a culturally learned construct that generates concomitant feelings additional to thos e gener- ated by body states should be considered, as in the ex- ample of Brent’s “feeling self”. If we view the self to be a theory we construct based on our personal experience, then such constructions are necessarily limited to the scope of that experience and the interpretive possibilities available to the individual. When we attempt to examine that which is doing the constructing, we are presented with a self-referencing feedback loop leading to Harre’s [15] conclusion that such a self must necessarily become invisible when it attempts self-examination. Yet, possession of a self al- lows one to situate one’s being in relation to others and in relation to past events and future possibilities – prac- tices that imply a certain level of awareness. Therefore, the felt illusion of an unseen homunculus, existing mo- mentarily outside of oneself to conduct this self-exami- nation, is generated. Feelings of volition, uniqueness and constancy may also be generated from the logic of having a self. It is difficult to imagine volition without an element of dis- tinctness or individuation implying that a person, sepa- rate from others, is carrying out a particular act. None of the participants in this study were able to point an aspect of their selves that exercised this volitio n and attempts to name that which was unique or constant were met with responses like, “the combination (of self-characteristics) is unique”, or “I will always be good-hearted and driven to learn”. The sense from the participants is th at they had a feeling that they were volitional, unique and constant, and they sought examples from the objective record that affirmed those feelings. Harre [37,38] said we teach children to have selves as part of the process of languaging, especially with respect to the teaching of indexical pronouns. This understanding would support a relativistic view that self-attributes like volition and uniqueness are culturally dependent. This study gave voice to the example of Maomao who was raised, culturally, to deny a volitional self. She reported that she preferred to not act volitionally, but she dis- played volition in certain contexts. Her example supports the notion that feelings of volition, uniqueness and con- stancy are consequences of having a self, and that while cultures may attempt to repress these attributes they cannot be eliminated en tirely. The fact that each participant recalled childhood and adult transitions involving relationships with other peo- ple is not surprising if we view the self to be cultural creation [23,24,39]. Such a cultural construct would be linked to family, community and societal networks, and a self so constructed would be dependent on those encom- passing networks for self-validation. We know we exist because the community surrounding us supports that ex- istence, and our memories, encoded in cultural units pro- vided by community and society, translate our choices and lived experience into an objectifiable record. This reinforces a sense of self-constancy that may resist bene- ficial change. In the example of Brent, a “poor learner” self-definition was maintained well into adulthood and changed only with extra-ordinary intervention. On the other hand, the fact that a majority of participants (8) changed their religious beliefs seems to contradict this assumption of self-constancy. This, in turn, may be a function of the Canadian multicultural context that, in effect, allows people to change their communities to re- flect and support desired belief systems. All participants reported feedback from others led to changes in themselves with six reporting that their memories served to preserve their sense of constancy amidst change. If we view the self to be a theory of who we are, then sufficient accumulative evidence will result in revisions to our self-theory. Volition allows us to ex- amine and thus improve our selves, and is evidenced by memes showing us as animators in action. Thus, Brent defined himself as an “empowered animator”, an active doer in specific roles as a teacher, athlete, broadcaster and self-changer. On the other hand, while all partici- pants were able to point to examples of their own voli- tion, self-efficacy may be, in Shelly Taylor’s [40] words, “a positive self-enhancing illusio n”. Maomao’s self-depi- ction as a programmed robo t fits with this latter interpre- tation. Her decision to become a Christian could have Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Mapping the Self with Units of Culture 192 flowed from her earlier programming where both good- ness and action were other-defined. Without the direct support of her family and community, she was open to finding a substitute family and community to give moral direction within the new (Canadian) context. Although she preferred to not make her own decisions, she did not consult with her parents prior to her religious conv ersion. It is as though her self’s maintenance needs initiated an act of volition that would not be countermanded by con- sultation with the usual authority figures. Thus, we are presented with the paradox of an other-determined self acting independently to maintain this quality. All of the participants to this study were able to re- count childhood transitions contributing to the develop- ment of their selves. This supports the notion the self develops experientially from units of culture associated with those experiences. Evolutionary change is likely with such an entity as memes are modified, new memes compatible with existing self-defining memes are added, and old peripheral memes are discarded; however, fun- damental change involving the construction of a new self would be extremely difficult. There would be no one internally to oversee such a construction as the existent self that would occupy this role is itself the object of de- construction. In summary, all of the participants in this study exhib- ited a similar structure of self. Self-change occurred in the histories of all of the participants, and they were able to detail environmental even ts that helped determine wh o they became. The initial self was established in child- hood and further change to that self was evolution ary. 6. Limitations People who volunteer to talk about themselves may have different characteristics than those who do not volunteer to talk about themselves. They might be expected to ex- hibit higher levels of assertiveness and self-confidence. Such characteristics could speak to feelings of empow- erment and the volunteer’s level of social activism. All the participants to this study expressed an interest in, or were engaged in, action to make the world a better place for others. It may be that there are people who do not have this orientation, and they may not be predisposed to volunteer for this kind of research. Therefore, these re- sults cannot be interpreted as universal. The qualities of the researcher can and do affect out- comes [41,42]. While the method used in this study at- tempted to minimize this risk through the use of non-directive open-ended questioning, researcher effects on the participant sample could not be negated totally. For example, one participant took two sessions before she was willing to share that she was bi-sexual. Had the researcher been more or less engaging, more or less en- thusiastic, or more or less accepting of diversity, this result could have varied. Frank [43] warned, “The risk of reducing the story to a narrative is that of losing the purpose for which people engage in storytelling, wh ich is relationship building”. In ordinary discourse, the storyteller is building a relation- ship with the listener; therefore, the interaction between teller and listener needs to be assessed with the under- standing the story will necessarily change in some ways depending on the social objectives of the participants in the discourse. Although the relationship between client and therapist or researcher involves non-ordinary dis- course which permits the reduction of a story to a narra- tive, people are social beings and they want to be liked, respected and acknowledged. Thus the researcher could not be a strictly neutral observer, but had an effect on participant presentatio n. 7. Recommendations for Future Research This exploratory study demons trated that the self may be mapped in ways that resonate with persons so mapped. Further studies are needed to determine whether the structure of the self that emerged from this study may be replicated and wi t h whi ch populations. Although the self was represented from individuals from collectivist as well as individualist cultures, this research did not study specific cultures in a way that would allow us to make generalizations about cultural differences. While there may be a basic structure to the self, the importance placed on certain aspects of that structure and their relationship to other aspects of the self would be expected to vary between cultures. The method used in this research may be used in such cross-cultural comparisons. In addition, research into ethnic, class and gender difference within and between cultures could benefit from this approach. The method outlined in this paper may also be used to inform clinical practice. None of the participants to this study were engaged in therapy at the commencement of this research. An examination of the selves of specific client populations and their comparison to the structure of the typical non-client self could potentially yield in- sights in epistemology and treatment. REFERENCES [1] A. Adler, “Understanding Human Nature,” Fawcett, Pub- lications, New York, 1957. [2] G. Vleioras and H. A. Bosma, “Predicting Change in Relational Identity Commitments: Exploration and Emo- tions,” Identity, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2005, pp. 35-56. [3] A. Ellis, “Rational-Emotive Therapy,” In: R. Corsini, Ed., Current Psychotherapies, Itasca Books, Minneapolis, 1979, pp. 185-229. [4] R. W. Lent, “Toward a Unifying Theoretical and Practical Perspective on Well-Being and Psychosocial Adjustment,” Journal of Counseling Psychology, Vol. 51, No. 4, 2004, Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Mapping the Self with Units of Culture Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 193 pp. 482-509. [5] A. H. Maslow, “Motivation and Personality,” Harper and Rowe, New York, 1987. [6] W. L. Ventis, “The Relationships between Religion and Mental Health,” Journal of Social Issues, Vol. 51, No. 2, 1995, pp. 33-48. [7] A. Bandura, C. Barbaranelli, G. V. Caprara and C. Pas- torelli, “Self Efficacy Beliefs as Shapers of Children’s Asperations and Career Trajectories,” Child Psychology, Vol. 72, No. 1, 2001, pp. 187-206. [8] D. J. Stipek and P. S. Kowalski, “Learned Helplessness in Task-Orienting versus Performance-Orientating Testing Conditions,” Journal of Educational Psychology, Vol. 81, No. 3, 1989, pp. 384-391. [9] F. I. Ishiama, “Culturally Dislocated Clients: Self-Vali- dation Issues and Cultural Conflict Issues and Counsel- ling Implications,” Canadian Journal of Counselling, Vol. 29, No. 3, 1995, pp. 262-275. [10] M. S. Corey and G. Corey, “Becoming a Helper,” Brooks/ Cole Publishing, New York, 2003. [11] W. Bridges, “Transitions: Making Sense of Life’s Chan- ges,” Addison-Wesley Publishing, Reading, 1980. [12] W. Bridges, “The Way of Transition: Embracing Life’s Most Difficult Moments,” Da Cappo Press, Cambridge, 2001. [13] C. G. Boeree, “Personality Theories,” 2006. http://www. ship.edu/%7Ecgboeree/perscontents.html [14] D. C. Dinkmeyer, W. L. Pew and D. C. J. Dinkmeyer, “Adlerian Counselling and Psychotherapy,” Brooks/Cole Publishing, Monterey, 1979. [15] R. Harre, “The Discursive Production of Selves,” Theory and Psychology, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1991, pp. 51-63. [16] W. James, “The Self,” In: R. F. Baumeister, Ed., The Self in Social Psychology: Key Readings in Social Psychology, Psychology Press, New York, 1999, pp. 69-77. [17] M. R. Leary and J. P. Tangney , “The Self as an Orga nizing Construct in the Behavioral and Social Sciences,” In: M. R. Leary and J. P. Tangney, Ed., Handbook of Self and Identity, The Guilford Press, New York, 2003, pp. 3-14. [18] W. Damon and D. Hart, “Self-Understanding in Child- hood and Adolescence,” Cambridge University Press, Ca m- bridge, 1988. [19] A. Kwiatkowska, “Sense of Personal Continuity and Dis- tinctivenes from Others in Childhood,” In: L. Oppen- heimer, Ed., The Self-Concept: European Perspectives on its Development, Aspect, and Applications, Springer-Ver- lag, Berlin, 1990, pp. 63-74. [20] S. Greenfield, “Journey to the Centers of the Mind,” W. H. Freeman & Co., New York, 1995. [21] R. Harre, “The Self as a Theoretical Concept,” In: M. Krausz, Ed., Relativism: Interpretation and Confrontation, Notre Dame, 1989, pp. 389-411. [22] W. Mischel and C. C. Morf, “The Self as a Psycho-Social Dynamic Processing System: A Meta-Perspective on a Century of the Self in Psychology,” In: M. R. Leary and J. P. Tangney, Ed., Handbook of Self and Identity, The Guilford Press, New York, 2003, pp. 15-43. [23] G. H. Mead, “The Mechanisms of Social Consciousness,” In: J. Pickering and M. Skinner, Ed., From Sentience to Symbols: Readings on Consciousness, University of To- ronto Press, Toronto, 1990, pp. 192-197. [24] A. Lock, “Universals in Human Conception,” In: J. Pickering and M. Skinner, Ed., From Sentience to Sym- bols: Readings on Consciousness, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1990, pp. 218-223. [25] R. Harre, “Personal Being: A Theory for Individual Psy- chology,” Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1984. [26] S. Blackmore, “The Meme Machine,” Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999. [27] M. Donald, “A Mind so Rare: The Evolution of Human Consciousness,” Norton Publishing, New York, 2001. [28] I. Price, “Steps toward the Memetic Self,” Journal of Memetics, Vol. 3, No. 1, 1999, pp. 75-80. [29] R. Dawkins, “The Selfish Gene,” Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1976. [30] E. O. Wilson, “Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge,” Vintage Books, New York, 1999. [31] M. Csikszentmihalyi, “The Evolving Self: A Psychology for the Third Millennium,” Harper Collins Publishers, New York, 1993. [32] R. Dawkins, “The Blind Watchmaker,” Penguin Books, London, 1986. [33] L. F. Robles-Diaz-de-Leon, “A Memetic/Participatory Approach for Changing Social Behavior and Promoting Environmental Stewardship in Jalisco, Mexico,” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Maryland, College Park, 2003. [34] M. B. Miles and A. M. Huberman, “Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook,” Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, 1994. [35] A. Adler, “Superiority and Social Interest: A Collection of Later Writings,” Roultlege and Keagan Paul Ltd., London, 1967. [36] A. Damasio, “The Feeling of what Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness,” Harcourt Pub- lishers, New York, 1999. [37] R. Harre, “The Singular Self: An Introduction to the Psy- chology of Personhood,” Sage Publications, Inc., Thou- sand Oaks, 1998. [38] R. Harre, “Language Games and Texts of Identity,” In: J. Shotter and K. J. Gergen, Ed., Texts of Identity, Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, 1989, pp. 20-35. [39] M. Leary, “The Curse of the Self,” Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2004. [40] S. E. Taylor, “Positive Illusions: Creative Self-Deception and the Healthy Mind,” Basic Books, New York, 1989. [41] R. Elliot, C. T. Fischer and D. L. Rennie, “Evolving Guidelines for Publication of Qualitative Research Stud- ies in Psychology and Related Fields,” British Journal of Clinical Psychology, Vol. 38, No. 3, 1999, pp. 215-229. [42] D. E. Polkinghorn, “Narrative Configuration in Qualita- tive Analysis,” Qualitative Studies in Education, Vol. 8, No. 1, 1995, pp. 5-23. [43] A. W. Frank, “The Standpoint of Storyteller,” Qualitative Health Research, Vol. 10, No. 3, 2000, pp. 354-356. |