Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

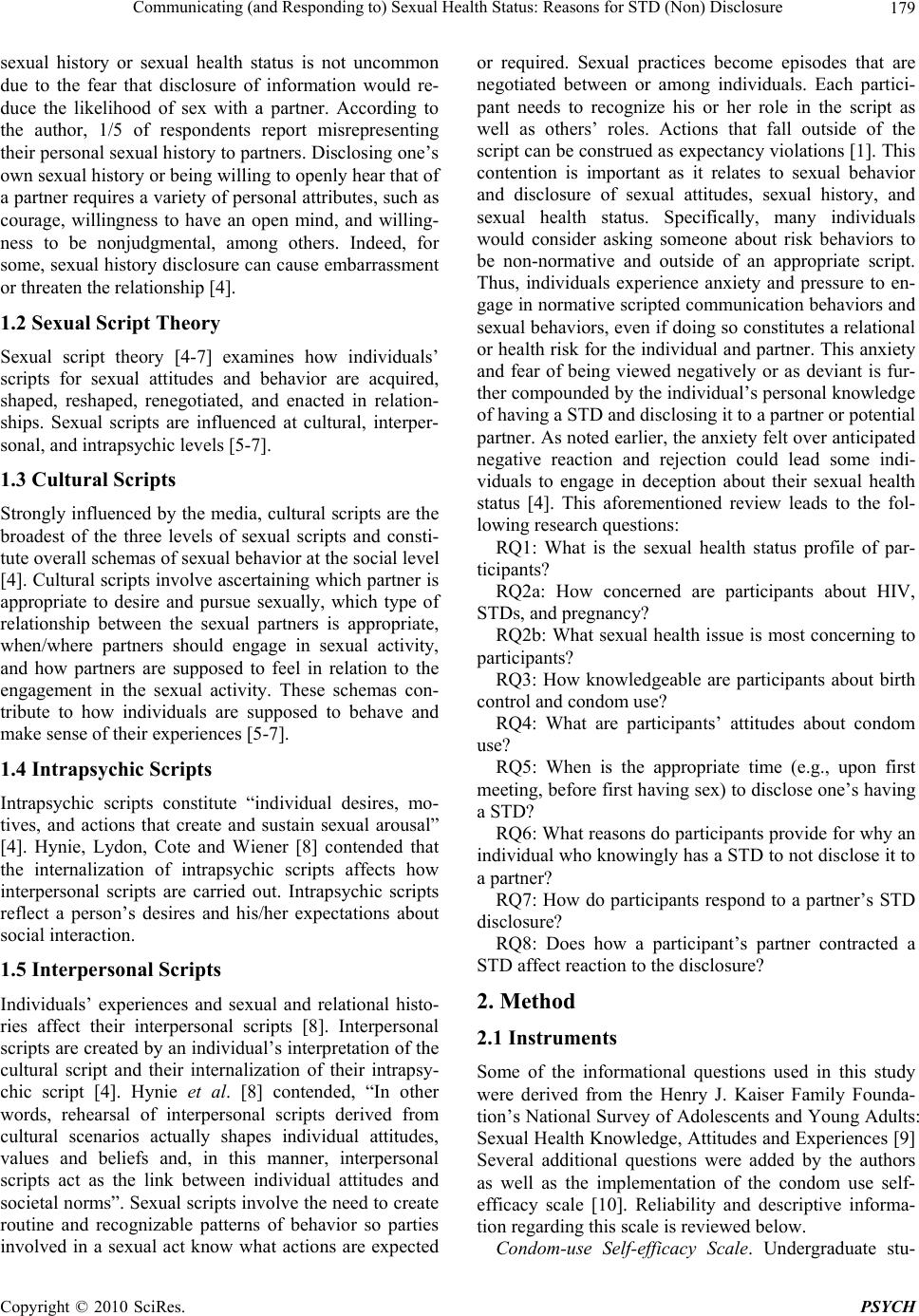

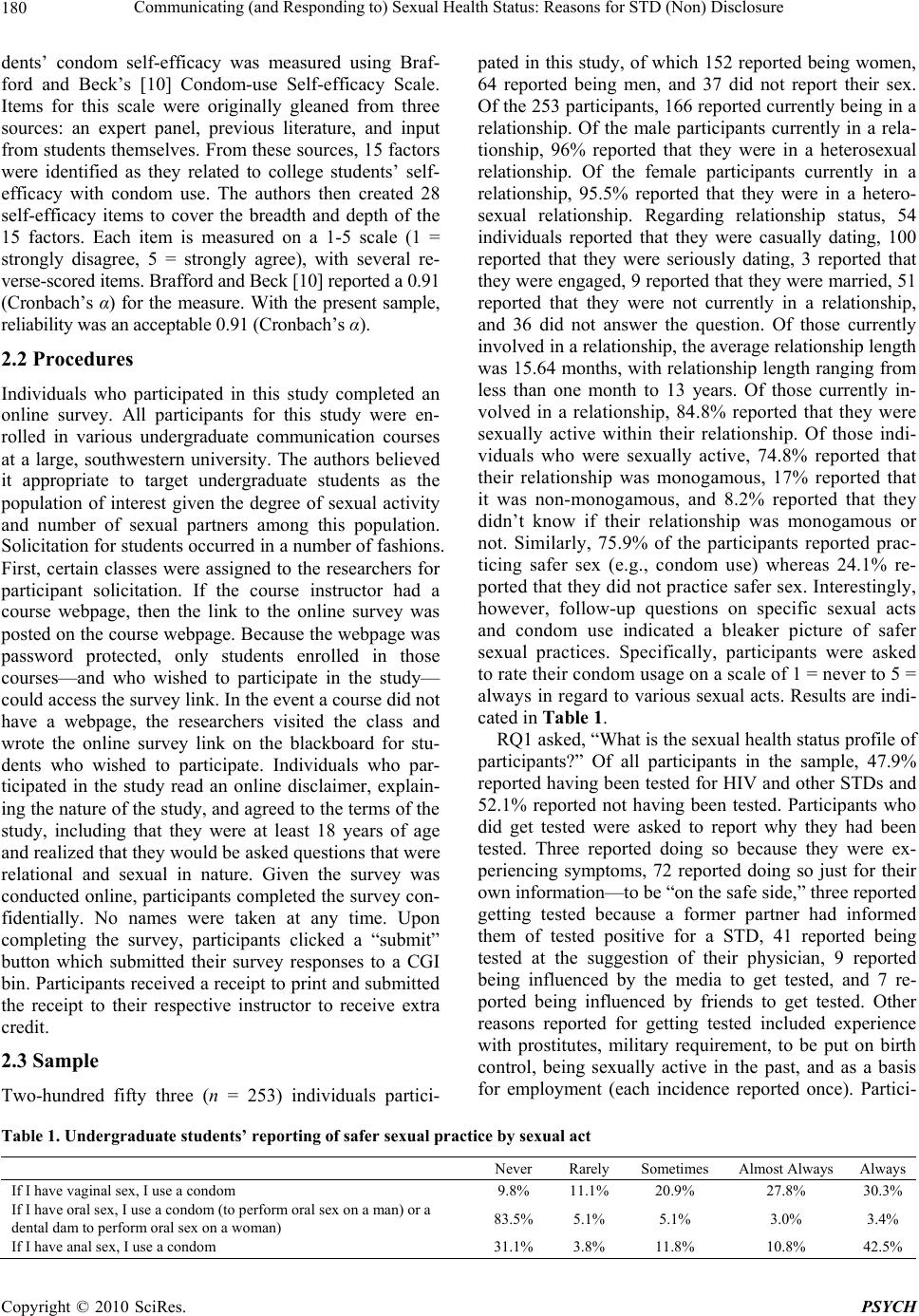

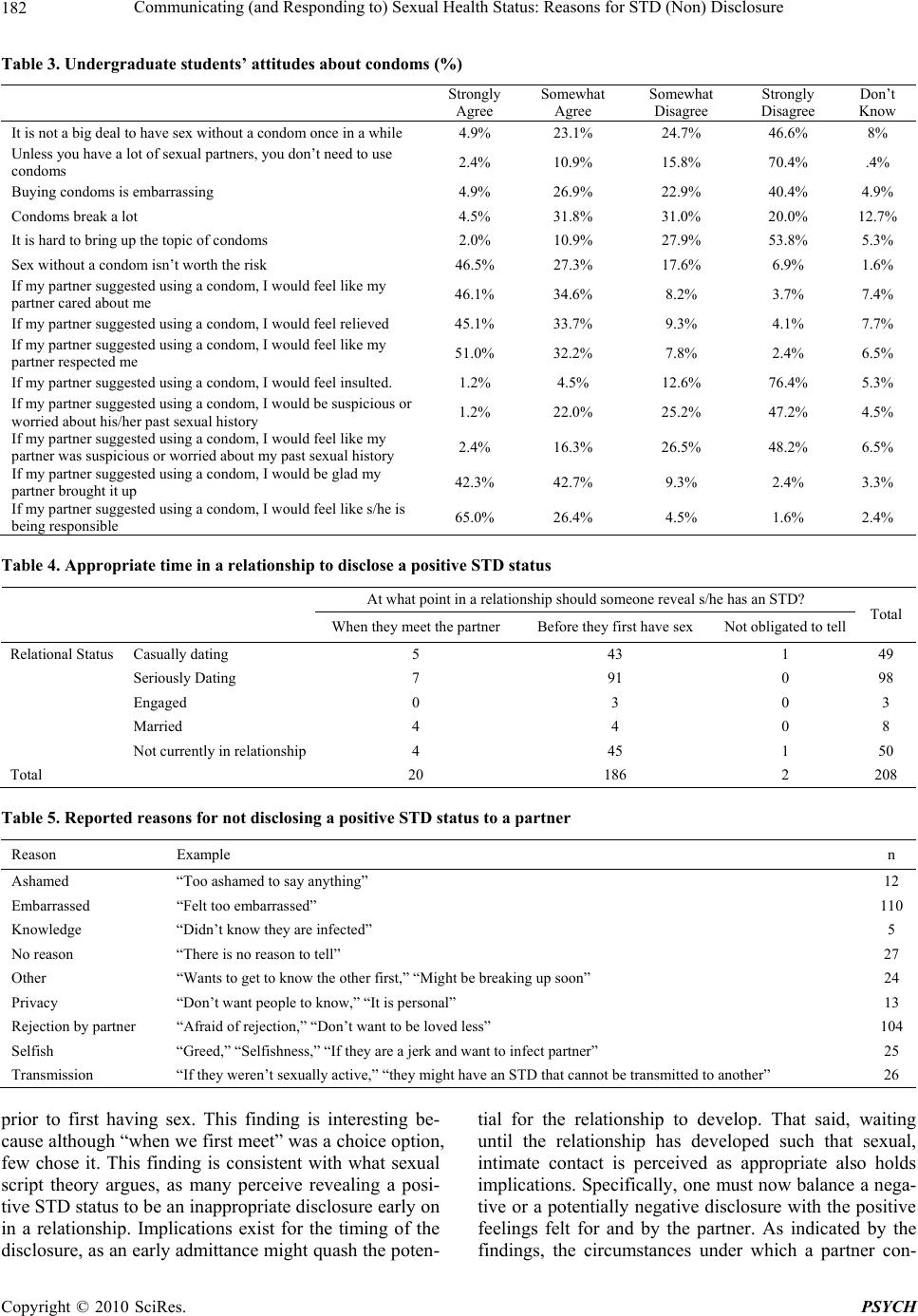

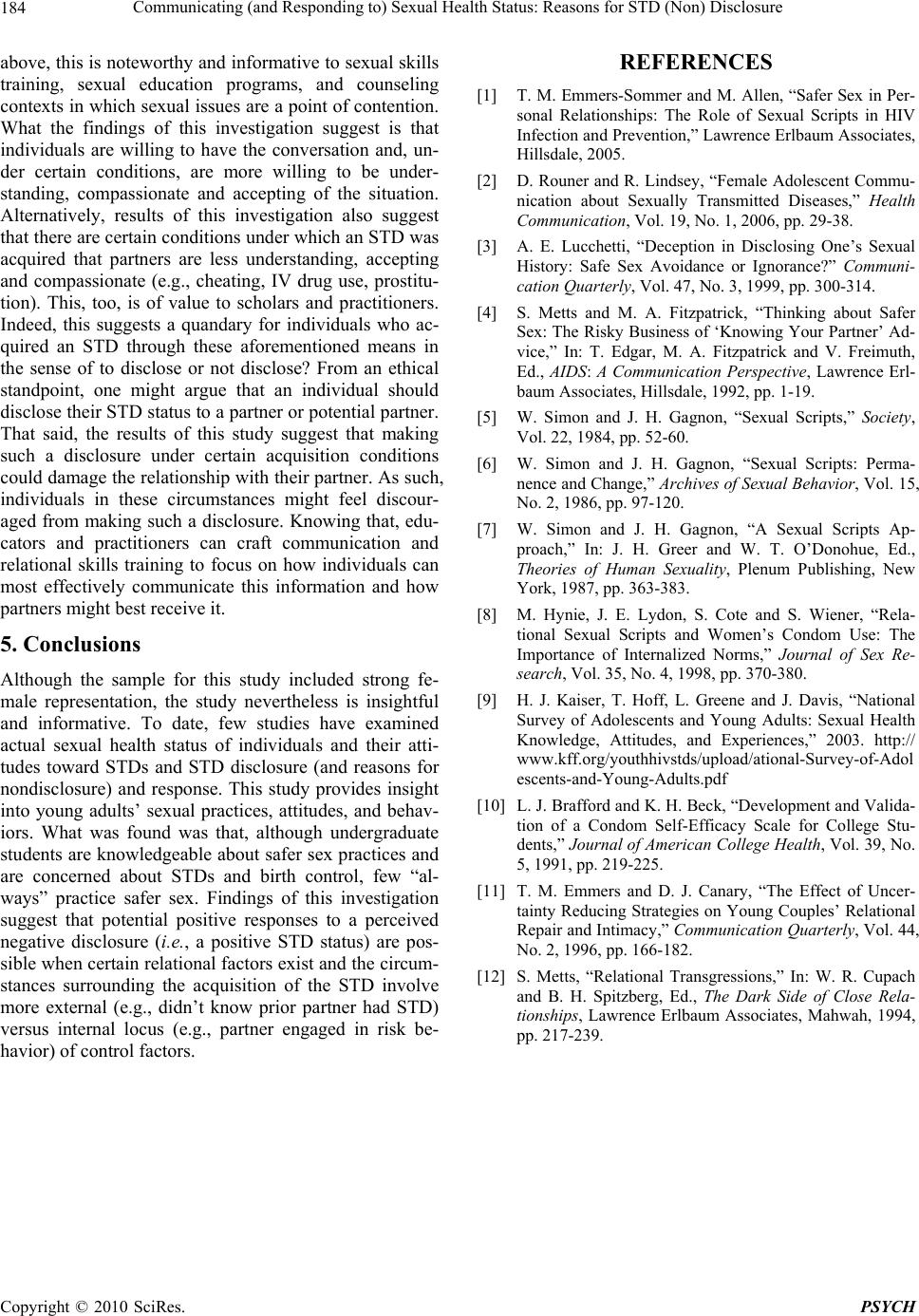

Psychology, 2010, 1: 178-184 doi:10.4236/psych.2010.13024 Published Online August 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH Communicating (and Responding to) Sexual Health Status: Reasons for STD (Non) Disclosure Tara M. Emmers-Sommer1, Kathleen M. Warber2, Stacey Passalacqua3, Angela Luciano3 1Department of Communication Studies, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, USA; 2Wittenberg University, Springfield, USA; 3Department of Communication, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA. Email: tara.emmerssommer@unlv.edu Received May 18th, 2010; revised July 3rd, 2010; accepted July 6th, 2010. ABSTRACT This investigation examines the sexual health status of individuals and their attitudes toward STDs and STD disclosure (and reasons for nondisclosure) and response. In doing so, this study provides insight into young adults’ sexual prac- tices, attitudes, and behaviors. Two-hundred fifty-three adults of varying relational status participated in an online study about sexual health status, sexual health knowledge, sexual behaviors, relational factors, responses to STD dis- closure, reasons for nondisclosure, and if circumstances under which a STD was acquired affected partners’ reaction to the disclosure. Results indicated that, although undergraduate students are knowledgeable about safer sex practices and are concerned about STDs and birth control, few “always” practice safer sex. When considering relational status, STD status and disclosure of that status becomes complicated. However, findings of this investigation suggest that po- tential positive responses to a perceived negative disclosure (i.e., a positive STD status) are possible when certain rela- tional factors exist and the circumstances surrounding the acquisition of the STD involve more external (e.g., didn’t know prior partner had STD) versus internal locus (e.g., partner engaged in risk behavior) of control factors. Keywords: STDs, Self-Disclosure, Sexual Health, Condom Use, Safer Sex 1. Introduction Much research exists on HIV and AIDS [1]. Similarly, much research exists on actual versus perceived knowl- edge about STDs [2]. Within the extant communication literature, little research exists regarding individuals communicating reasons for (not) disclosing a positive STD status and the reception of such a disclosure. Clearly, communicating about one’s sexual health status and feeling comfortable doing so are of value as such communication adds to our repertoire of knowledge about safer sex, safer sexual communication as well as the safety of the self and others. According to Emmers-Sommer and Allen [1], “safer sex is “any action a person takes to diminish the level of risk for HIV infection”. This definition can also be ap- plied to reducing the risk of STD infection. Safer sex is most often used to describe condom use during sexual behavior to prevent contact with bodily fluids. Other sexual behaviors exist that are deemed “safer” than oth- ers. For example, engagement in mutual masturbation vs. anal sex or engagement in oral sex (which does carry some degree of risk) vs. engagement in vaginal sex are both considered to be safer sex practices. One can also reduce his or her STD or HIV risk by reducing the num- ber of sexual partners and engaging in sexual behavior with partners who don’t carry increased risk factors (e.g., IV drug use, multiple partners, prostitution). Understand- ing a partner’s risk factors, however, necessitates that in- dividuals engage in candid discussions with the partner as well as be open and honest about their own sexual health. 1.1 Barriers to Disclosure of Sexual Health Status Unfortunately, many individuals perceive candid sexual discussions as inappropriate and telling or asking about such information as “nobody’s business”. Engagement in such discussions is deemed taboo by many and as an expectancy violation. Asking about another’s sexual practices and health might be deemed offensive. Simi- larly, engagement in such disclosures about the self might arouse suspicions in a potential partner. According to Lucchetti [3], deceptive disclosure practices about  Communicating (and Responding to) Sexual Health Status: Reasons for STD (Non) Disclosure179 sexual history or sexual health status is not uncommon due to the fear that disclosure of information would re- duce the likelihood of sex with a partner. According to the author, 1/5 of respondents report misrepresenting their personal sexual history to partners. Disclosing one’s own sexual histo ry or being willing to openly hear th at of a partner requires a variety of personal attributes, such as courage, willingness to have an open mind, and willing- ness to be nonjudgmental, among others. Indeed, for some, sexual history disclosure can cause embarrassment or threaten the relationship [4]. 1.2 Sexual Script Theory Sexual script theory [4-7] examines how individuals’ scripts for sexual attitudes and behavior are acquired, shaped, reshaped, renegotiated, and enacted in relation- ships. Sexual scripts are influenced at cultural, interper- sonal, and intrapsych ic levels [5-7]. 1.3 Cultural Scripts Strongly influenced by the media, cultural scripts are the broadest of the three levels of sexual scripts and consti- tute overall schemas of sexual behavior at the social level [4]. Cultural scripts involve ascertaining which partner is appropriate to desire and pursue sexually, which type of relationship between the sexual partners is appropriate, when/where partners should engage in sexual activity, and how partners are supposed to feel in relation to the engagement in the sexual activity. These schemas con- tribute to how individuals are supposed to behave and make sense of their experiences [5-7]. 1.4 Intrapsychic Scripts Intrapsychic scripts constitute “individual desires, mo- tives, and actions that create and sustain sexual arousal” [4]. Hynie, Lydon, Cote and Wiener [8] contended that the internalization of intrapsychic scripts affects how interpersonal scripts are carried out. Intrapsychic scripts reflect a person’s desires and his/her expectations about social interaction. 1.5 Interpersonal Scripts Individuals’ experiences and sexual and relational histo- ries affect their interpersonal scripts [8]. Interpersonal scripts are created by an individual’s interpretation of the cultural script and their internalization of their intrapsy- chic script [4]. Hynie et al. [8] contended, “In other words, rehearsal of interpersonal scripts derived from cultural scenarios actually shapes individual attitudes, values and beliefs and, in this manner, interpersonal scripts act as the link between individual attitudes and societal norms”. Sexual scripts involve the need to create routine and recognizable patterns of behavior so parties involved in a sexual act know what actions are expected or required. Sexual practices become episodes that are negotiated between or among individuals. Each partici- pant needs to recognize his or her role in the script as well as others’ roles. Actions that fall outside of the script can be construed as expectancy violations [1]. This contention is important as it relates to sexual behavior and disclosure of sexual attitudes, sexual history, and sexual health status. Specifically, many individuals would consider asking someone about risk behaviors to be non-normative and outside of an appropriate script. Thus, individuals experience anxiety and pressure to en- gage in normative scripted communication behaviors and sexual behaviors, even if do ing so constitutes a relational or health risk for the individual and partner. This anxiety and fear of being viewed negatively or as deviant is fur- ther compounded by the individu al’s person al knowledge of having a STD and disclosing it to a partner or potential partner. As noted earlier, the anxiety felt over anticipated negative reaction and rejection could lead some indi- viduals to engage in deception about their sexual health status [4]. This aforementioned review leads to the fol- lowing research questions : RQ1: What is the sexual health status profile of par- ticipants? RQ2a: How concerned are participants about HIV, STDs, and pregnancy? RQ2b: What sexual h ealth issue is most concerning to participants? RQ3: How knowledgeable are participants about birth control and condom use? RQ4: What are participants’ attitudes about condom use? RQ5: When is the appropriate time (e.g., upon first meeting, before first having sex) to disclose one’s having a STD? RQ6: What reasons do participants provide for why an individual who knowingly has a STD to not disclose it to a partner? RQ7: How do participants respond to a partner’s STD disclosure? RQ8: Does how a participant’s partner contracted a STD affect reaction to the disclosure? 2. Method 2.1 Instruments Some of the informational questions used in this study were derived from the Henry J. Kaiser Family Founda- tion’s National Survey of Adolescents and Youn g Adults: Sexual Health Knowledge, Attitudes and Experiences [9] Several additional questions were added by the authors as well as the implementation of the condom use self- efficacy scale [10]. Reliability and descriptive informa- tion regarding this scale is reviewed below. Condom-use Self-efficacy Scale. Undergraduate stu- Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Communicating (and Responding to) Sexual Health Status: Reasons for STD (Non) Disclosure Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 180 dents’ condom self-efficacy was measured using Braf- ford and Beck’s [10] Condom-use Self-efficacy Scale. Items for this scale were originally gleaned from three sources: an expert panel, previous literature, and input from students themselves. From these sources, 15 factors were identified as they related to college students’ self- efficacy with condom use. The authors then created 28 self-efficacy items to cover the breadth and depth of the 15 factors. Each item is measured on a 1-5 scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), with several re- verse-scored items. Brafford and Beck [10] reported a 0.91 (Cronbach’s α) for the measure. With the present sample, reliability was an acceptable 0.91 (Cronbach’s α). 2.2 Procedures Individuals who participated in this study completed an online survey. All participants for this study were en- rolled in various undergraduate communication courses at a large, southwestern university. The authors believed it appropriate to target undergraduate students as the population of interest given the degree of sexual activity and number of sexual partners among this population. Solicitation for students occurred in a number of fashions. First, certain classes were assigned to the researchers for participant solicitation. If the course instructor had a course webpage, then the link to the online survey was posted on the course webpage. Because the webpage was password protected, only students enrolled in those courses—and who wished to participate in the study— could access the survey link. In the event a course did not have a webpage, the researchers visited the class and wrote the online survey link on the blackboard for stu- dents who wished to participate. Individuals who par- ticipated in the study read an online disclaimer, explain- ing the nature of the study, and agreed to the terms of the study, including that they were at least 18 years of age and realized that they would be asked questions that were relational and sexual in nature. Given the survey was conducted online, participants completed the survey con- fidentially. No names were taken at any time. Upon completing the survey, participants clicked a “submit” button which submitted their survey responses to a CGI bin. Participants received a receipt to print and submitted the receipt to their respective instructor to receive extra credit. 2.3 Sample Two-hundred fifty three (n = 253) individuals partici- pated in this study, of which 152 reported being women, 64 reported being men, and 37 did not report their sex. Of the 253 participants, 166 reported currently being in a relationship. Of the male participants currently in a rela- tionship, 96% reported that they were in a heterosexual relationship. Of the female participants currently in a relationship, 95.5% reported that they were in a hetero- sexual relationship. Regarding relationship status, 54 individuals reported that they were casually dating, 100 reported that they were seriously dating, 3 reported that they were engaged, 9 reported that they were married, 51 reported that they were not currently in a relationship, and 36 did not answer the question. Of those currently involved in a relationsh ip, the av erage relation ship leng th was 15.64 months, with relationship length ranging from less than one month to 13 years. Of those currently in- volved in a relationship, 84.8% reported that they were sexually active within their relationship. Of those indi- viduals who were sexually active, 74.8% reported that their relationship was monogamous, 17% reported that it was non-monogamous, and 8.2% reported that they didn’t know if their relationship was monogamous or not. Similarly, 75.9% of the participants reported prac- ticing safer sex (e.g., condom use) whereas 24.1% re- ported that they did not practice safer sex. Interestingly, however, follow-up questions on specific sexual acts and condom use indicated a bleaker picture of safer sexual practices. Specifically, participants were asked to rate their condom usage on a scale of 1 = never to 5 = alwa ys in regar d to various sexual acts. Results are indi- cated in Table 1. RQ1 asked, “What is the sexual health status profile of participants?” Of all participants in the sample, 47.9% reported having been tested for HIV and other STDs and 52.1% reported not having been tested. Participants who did get tested were asked to report why they had been tested. Three reported doing so because they were ex- periencing symptoms, 72 reported doing so just for their own information—to be “on the safe side,” three reported getting tested because a former partner had informed them of tested positive for a STD, 41 reported being tested at the suggestion of their physician, 9 reported being influenced by the media to get tested, and 7 re- ported being influenced by friends to get tested. Other reasons reported for getting tested included experience with prostitutes, military requirement, to be put on birth control, being sexually active in the past, and as a basis for employment (each incidence reported once). Partici- Table 1. Undergraduate students’ r e por ting of safer sexual practice by sexual act Never Rarely Somet imes Almost AlwaysAlways If I have vaginal sex , I use a condom 9.8% 11.1% 20.9% 27.8% 30.3% If I have oral sex, I use a condom (t o perform oral sex on a man) or a dental dam to perform oral sex on a woman) 83.5% 5.1% 5.1% 3.0% 3.4% If I have anal sex, I use a condom 31.1% 3.8% 11.8% 10.8% 42.5%  Communicating (and Responding to) Sexual Health Status: Reasons for STD (Non) Disclosure181 pants were asked if they had ever had an STD and 7.8% reported “yes,” 81.6% reported “no,” and 10.6% reported “don’t know”. Two participants reported having herpes, 2 reported having gonorrhea, 4 reported having chlamy- dia, 9 reported HPV, and one reported having HPV- genital warts. Participants were asked if their current relational partner had an STD. Of those participants cur- rently in a relationship, 3% reported that their partner had an STD, 83.4% reported that their partner did not have an STD, 12.8% reported that they didn’t know if their part- ner had an STD or not, 4 reported that it was a “non- issue,” and 2 did not answer the question. All participants were asked to report if any past partner, to their knowl- edge, had an STD. Of those answering the question, 5.6% reported “yes,” 73.5% reported “no,” 20.9% re- ported that they “didn’t know” and 38 participan ts didn’t answer the question. RQ2a and b asked, “How concerned are participants about HIV, STDs, and pregnancy” and “What sexual health issue is most concerning to participants?” For those answering the questions, 75.9% reported that HIV, STDs, and pregnancy were “A very big concern,” 15.3% reported that it was “A somewhat big concern,” 6.9% reported that it was “Not much of a concern,” 1.4% re- ported that it was “Not a concern at all,” and 0.5% re- ported “Don’t know”. Participants most often reported that HIV was most concerning to them (48.6%), followed by pregnancy (34.4%), and 17% reported that they were most concerned by STDs (gonorrhea, syphilis, genital warts, chlamydia, herpes). RQ3 asked, “How knowledgeable are participants about birth control and condom use?” Results are re- ported in Table 2. RQ4 asked, “What are participants’ attitudes about condom use?” Results are reported in Table 3. RQ5 asked, “When is the appropriate time (e.g., upon first meeting, before first having sex) to disclose one’s having a STD?” Results are reported in Table 4. For RQs 6-8, a coder coded all of the responses. Using procedures similar to Emmers and Canary [11]), re- sponses were placed into categories derived by theme. When a response did not fit a category, a new category was formed. A second coder served as a reliability check for a random 20% of the responses for each question. Re- liability for RQ6-RQ8 were 0.88, 0.96, and 0.96 (Cohen ’s kappa), respectively. RQ6 asked, “What reasons do participants provide for why an individual who knowingly has a STD to not dis- close it to a partner? Results are reported in Table 5. RQ7 asked, “How do participants respond to a part- ner’s STD disclosure?” Results are reported in Table 6. RQ8 asked, “Does how the participant’s partner con- tracted a STD affect reaction to the disclosure?” Results are reported in Table 7. 3. Discussion The purpose of this investigation was to examine sexual health status, concerns, and reasons to disclose (and not disclose) STD status and response to such disclosures. Results of this investigation indicate that undergraduate students are, indeed, concerned about STDs and HIV, have positive attitudes about condom use, and are knowledgeable about HIV and STD transmission. Nev- ertheless, only 30% report “always” wearing a condom during vaginal sex. And, despite the fact that HIV can be transmitted via anal or oral sex, only 3.4% report using a condom or dental dam when having oral sex and 42.5% report using a condom when having anal sex. This find- ing is not uncommon as many individuals, while knowl- edgeable about HIV, AIDS and other STDs, often do not practice safer sex. Often, individuals believe that they are not vulnerable to STD or HIV acquisition and this im- pression grows as the relationship does. Specifically, as relationships develop and trust increases, condoms are often abandoned for alternative forms of birth control. This finding is consisten t with Metts and Fitzp atrick’s [4] contention that as relationships develop individuals seek out alternative forms of birth control. A strong contribution of this investigation is that it examined students’ perceptions of when it was the ap- propriate time to disclose a positive STD status to a partner, reasons for not doing so, how one might react to the disclosure, and if the circumstances under which the STD was contracted affected reaction to the disclosure. Findings indicated that most individuals felt it was ap- propriate to inform the partner of a positive STD status Table 2. Undergraduate students’ knowledge about birth control and condom use (%) Very Effective Somewhat Effective Not too Effective Not at all Effective Don’t Know How effective are birth control pills in preventing pregna nc y ? 56.2% 39.6% .9% 0% 3.2% How effective are birth control pills at preven t ing HIV/AIDS? 9% 1.8% 3.7% 90.4% 3.2% How effective are birth control pills at preventing other STDs (gonorrhea, syphilis, genital warts, chlamydia, herpes)? .5% 2.8% 2.3% 90.4% 4.1% How effective are condoms at prev en ti n g pregnancy? 32.1% 64.2% .9% 1.4% 1.4% How effective are condoms at preventing HIV/AIDS? 28.1% 47.5% 12.4% 7.8% 4.1% How effective are condoms at preventing other STDs (gonorrhea, syphilis, genital warts, chlamy dia, herpes)? 19.3% 53.2% 16.1% 6.9% 4.6% Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Communicating (and Responding to) Sexual Health Status: Reasons for STD (Non) Disclosure 182 Table 3. Undergraduate students’ attitude s about c o ndoms (%) Strongly Agree Somewhat Agree Somewhat Disagree Strongly Disagree Don’t Know It is not a big deal to have sex without a condom once in a while 4.9% 23.1% 24.7% 46.6% 8% Unless you have a lot of sexual partne rs, you don’t need to use condoms 2.4% 10.9% 15.8% 70.4% .4% Buying condoms is embarrassing 4.9% 26.9% 22.9% 40.4% 4.9% Condoms break a l o t 4.5% 31.8% 31.0% 20.0% 12.7% It is hard to bring up the topic of condoms 2.0% 10.9% 27.9% 53.8% 5.3% Sex without a condom isn’t worth the ris k 46.5% 27.3% 17.6% 6.9% 1.6% If my partner suggested using a condom, I would feel like my partner care d a b o u t me 46.1% 34.6% 8.2% 3.7% 7.4% If my partner su ggested using a condom, I would feel relieved 45.1% 33.7% 9.3% 4.1% 7.7% If my partner suggested using a condom, I would feel like my partner respected me 51.0% 32.2% 7.8% 2.4% 6.5% If my partner su ggested using a condom, I would feel in sulted. 1. 2% 4.5 % 12.6% 76.4% 5.3% If my partner suggested using a condom, I would be suspi c i o u s o r worried about his/her past s ex u al h i st ory 1.2% 22.0% 25.2% 47.2% 4.5% If my partner suggested using a condom, I would feel like my partner was suspicious or worried about my past sexual history 2.4% 16.3% 26.5% 48.2% 6.5% If my partner su ggested using a condom, I would be gla d my partner brought it up 42.3% 42.7% 9.3% 2.4% 3.3% If my partner suggested using a condom, I would feel like s/he is being responsible 65.0% 26.4% 4.5% 1.6% 2.4% Table 4. Appropriate time in a relationship to disclose a positive STD status At what point in a relationship should someone reveal s/he has an S TD? When they meet the partnerBefore they first have sex Not obligated to tellTotal Relational Status Casually dating 5 43 1 49 Seriously Dating 7 91 0 98 Engaged 0 3 0 3 Married 4 4 0 8 Not currently in relationship 4 45 1 50 Total 20 186 2 208 Table 5. Reported reasons for not disclosi ng a positive STD status to a part ne r Reason Example n Ashamed “Too ashamed to say anything” 12 Embarrassed “Felt too emb a rrassed” 110 Knowledge “Didn’t know they are infected” 5 No reason “There is no reason to tell” 27 Other “Wants to get to know the other f irst,” “Might be breaking up soon” 24 Privacy “Don’t want people to know,” “ It is personal” 13 Rejection by partner “Afraid of rejection,” “Don’t want to be lo ved l ess ” 104 Selfish “Greed,” “Selfishness,” “If they are a jerk and want to infect partner” 25 Transmission “If they weren’t sexually active,” “they might have an STD that cannot be transm it te d to an other” 26 prior to first having sex. This finding is interesting be- cause although “when we first meet” was a ch oice option, few chose it. This finding is consistent with what sexual script theory argues, as many perceive revealing a posi- tive STD status to be an in appropriate disclosure early on in a relationship. Implications exist for the timing of the disclosure, as an early ad mittance might quash the poten- tial for the relationship to develop. That said, waiting until the relationship has developed such that sexual, intimate contact is perceived as appropriate also holds implications. Specifically, one must now balance a nega- tive or a potentially negative disclosure with the positive feelings felt for and by the partner. As indicated by the findings, the circumstances under which a partner con- Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Communicating (and Responding to) Sexual Health Status: Reasons for STD (Non) Disclosure183 tracted an STD mattered to many participants. Specifi- cally, if the STD was contracted via behaviors that are perceived as risky or irresponsible (e.g., IV drug use, prostitution, cheating), individuals were less tolerant of those infection conditions. Results indicate, however, that if the partner contracted the STD unknowingly (e.g., an infected partner in his/her past did not inform him/her) or as the result of a past, serious relationship, then indi- viduals might accept the STD disclosure more compas- sionately or acceptingly. Th is is important information as it assists in our understanding about the potential effect of health status disclosures on partners and that certain conditions surro unding the nature of the disclosure co uld possibly am el iorat e negative feelings . Participants provided many reasons for why individu- als might not want to disclose a positive STD status, with the two most prominent reasons being “embarrassment” and “fear of rejection”. This information is important for a variety of reasons. First, results of this investigation indicate that individuals want to know their partner’s STD status prior to having sex. Yet, the participants were also able to provide over 300 reasons why someone might not want to disclose that information. What is suggested by the findings is that if individuals felt that they could disclose their positive STD status in a safe and understanding relational environment such that the likelihood of feeling embarrassment or rejection was reduced, the likelihood of disclosure could increase. Timing of the disclosure is complicated. From a sexual script theory perspective, mentioning this type of infor- mation early in a relationship is more frowned upon than in more advanced relationships as “sex talk” is consid- ered to be inappropriate and deviant in a relationship’s infancy. Yet, making a STD disclosure in an advanced relationship can also be perceived negatively for a vari- ety of reasons. For one, if an individual entered into a relationship knowing s/he had a STD, his/her partner would have likely expected this information to have been part of past discussion in a close, co mmitted relatio nship. Further, if a partner acquired the STD after the relation- ship had been established, it is again perceived as a transgression, as it suggests engagement in risk behavior (e.g., infidelity, IV drug use). Both circumstances sug- gest a transgression took place [12], but in different fashions. 4. Implications Numerous positive implications exist from the results of this investigation; information that holds practical impli- cations for sexual communication skills training, sexual education programs, and counseling. Indeed, safer sexual communication skills training and sexual education are valuable and essential from a preventative standpoint. And, in a best case scenario, individuals would engage in safer sexual communication and safer sexual practices with their partner. However, we recognize that this is often not the case for myriad reasons. For example, part- ners could use poor judgment, deception, or “let things get out of hand”. Even with the best of intentions, part- ners could be unaware of their STD status or experience condom failure (e.g., breakage, leaking). It is important to consider individuals who might be experiencing a sense of hopelessness due to mistakes, poor judgment, or lack of information. Indeed, as indicated by these results, it is not uncommon for someone with a positive STD status to feel like “damaged goods” and fear disclosing their status to a partner or potential partner out of fear of rejection or embarrassment. Valuably, this study demon- strates that a partner or potential partner might be more receptive, understanding and compassionate than an in- dividual might have anticipated when receiving a disclo- sure about a positive partner STD status. As mentioned Table 6. Responses to a partner’s STD disc losur e Response n Shocked/surprised 34 Negative emotions (angry, sad, upset) 69 Glad s/he told me/respect honesty/be supportive 26 Stop having sex 29 Get tested/see a doctor 24 Be sure to use protection 19 Break up/leave partner 32 Stay/feel the same about partner 18 Learn more/ask more questions 43 Depends on the STD/how the partner contracted it 18 Depends on how much I like the person 18 Not sure 22 Other 14 Table 7. Circumstances in which STD was acquired and tolerability Circumstance Tolerability Yes No Unsuren If the partner got it from che atin g X 22 If the partner got it from gay sex X 7 If the partner got it from promiscu- ous/careless behavior X 30 If the partner was lied to/situation was not their fault X 16 If the person got it from drugs/prostitution X 9 If the person got from a serious relationship X 7 How long they’ve known they had it/if they had slept with me already X 5 Other X 14 How s/he got it/from whom X 16 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Communicating (and Responding to) Sexual Health Status: Reasons for STD (Non) Disclosure Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 184 above, this is notewo rthy and informative to sexual skills training, sexual education programs, and counseling contexts in which sexual issues are a point of contention. What the findings of this investigation suggest is that individuals are willing to have the conversation and, un- der certain conditions, are more willing to be under- standing, compassionate and accepting of the situation. Alternatively, results of this investigation also suggest that there are certain conditions under which an STD was acquired that partners are less understanding, accepting and compassionate (e.g., cheating, IV drug use, prostitu- tion). This, too, is of value to scholars and practitioners. Indeed, this suggests a quandary for individuals who ac- quired an STD through these aforementioned means in the sense of to disclose or not disclose? From an ethical standpoint, one might argue that an individual should disclose their STD status to a partner or potential partner. That said, the results of this study suggest that making such a disclosure under certain acquisition conditions could damage the relationship with their partner. As such, individuals in these circumstances might feel discour- aged from making such a disclosure. Knowing that, edu- cators and practitioners can craft communication and relational skills training to focus on how individuals can most effectively communicate this information and how partners might best receive it. 5. Conclusions Although the sample for this study included strong fe- male representation, the study nevertheless is insightful and informative. To date, few studies have examined actual sexual health status of individuals and their atti- tudes toward STDs and STD disclosure (and reasons for nondisclosure) and response. This study provides insight into young adults’ sexual practices, attitudes, and behav- iors. What was found was that, although undergraduate students are knowledgeable about safer sex practices and are concerned about STDs and birth control, few “al- ways” practice safer sex. Findings of this investigation suggest that potential positive responses to a perceived negative disclosure (i.e., a positive STD status) are pos- sible when certain relational factors exist and the circum- stances surrounding the acquisition of the STD involve more external (e.g., didn’t know prior partner had STD) versus internal locus (e.g., partner engaged in risk be- havior) of control factors. REFERENCES [1] T. M. Emmers-Sommer and M. Allen, “Safer Sex in Per- sonal Relationships: The Role of Sexual Scripts in HIV Infection and Prevention,” Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, 2005. [2] D. Rouner and R. Lindsey, “Female Adolescent Commu- nication about Sexually Transmitted Diseases,” Health Communication, Vol. 19, No. 1, 2006, pp. 29-38. [3] A. E. Lucchetti, “Deception in Disclosing One’s Sexual History: Safe Sex Avoidance or Ignorance?” Communi- cation Quarterly, Vol. 47, No. 3, 1999, pp. 300-314. [4] S. Metts and M. A. Fitzpatrick, “Thinking about Safer Sex: The Risky Business of ‘Knowing Your Partner’ Ad- vice,” In: T. Edgar, M. A. Fitzpatrick and V. Freimuth, Ed., AIDS: A Communication Perspective, Lawrence Erl- baum Associates, Hillsdale, 1992, pp. 1-19. [5] W. Simon and J. H. Gagnon, “Sexual Scripts,” Society, Vol. 22, 1984, pp. 52-60. [6] W. Simon and J. H. Gagnon, “Sexual Scripts: Perma- nence and Change,” Archives of Sexual Behavior, Vol. 15, No. 2, 1986, pp. 97-120. [7] W. Simon and J. H. Gagnon, “A Sexual Scripts Ap- proach,” In: J. H. Greer and W. T. O’Donohue, Ed., Theories of Human Sexuality, Plenum Publishing, New York, 1987, pp. 363-383. [8] M. Hynie, J. E. Lydon, S. Cote and S. Wiener, “Rela- tional Sexual Scripts and Women’s Condom Use: The Importance of Internalized Norms,” Journal of Sex Re- search, Vol. 35, No. 4, 1998, pp. 370-380. [9] H. J. Kaiser, T. Hoff, L. Greene and J. Davis, “National Survey of Adolescents and Young Adults: Sexual Health Knowledge, Attitudes, and Experiences,” 2003. http:// www.kff.org/youthhivstds/upload/ational-Survey-of-Adol escents-and-Young-Adults.pdf [10] L. J. Brafford and K. H. Beck, “Development and Valida- tion of a Condom Self-Efficacy Scale for College Stu- dents,” Journal of American College Health, Vol. 39, No. 5, 1991, pp. 219-225. [11] T. M. Emmers and D. J. Canary, “The Effect of Uncer- tainty Reducing Strategies on Young Couples’ Relational Repair and Intimacy,” Communication Quarterly, Vol. 44, No. 2, 1996, pp. 166-182. [12] S. Metts, “Relational Transgressions,” In: W. R. Cupach and B. H. Spitzberg, Ed., The Dark Side of Close Rela- tionships, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, 1994, pp. 217-239. |