Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

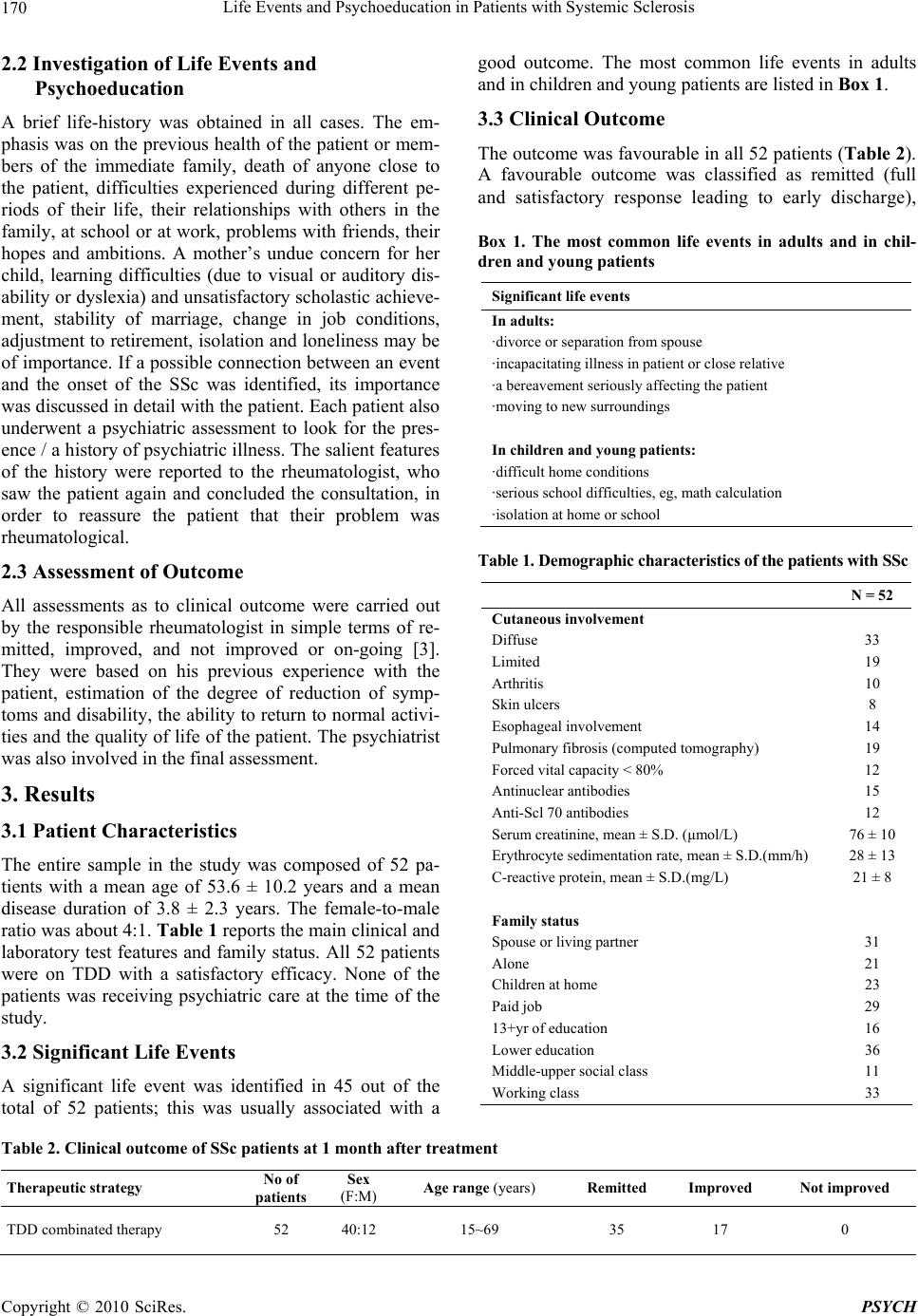

Psychology, 2010, 1: 169-172 doi:10.4236/psych.2010.13022 Published Online August 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 169 Life Events and Psychoeducation in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis Yue Chen1*, Ji-Zhong Huang2, Yu Qiang2, Mao-Mao Han1, Shi-Chao Liu1, Chun-Lan Cui1 1Department of Geriatrics, the First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China; 2Departmecnt of Rheumatology, Hangzhou Tongji Hospital, Hangzhou, China. Email: lxling@mail.hz.zj.cn Received April 8th, 2010; revised June 9th, 2010; accepted June 11th, 2010. ABSTRACT Objective: The purpose of this study was to assess the impact of psychological/psychoeducational assessment in pa- tients with systemic sclerosis (SSc). Methods: A diagnostic interview was undertaken in order to investigate any tem- poral connection between an adverse life event and the first appearance of SSc. Following this, the rheumatologist's assessment of subsequent changes in the SSc were noted. The psychoeducation we did, as an adjunct to conventional thoracic duct lymphatic drainage therapy (TDD), started in Dec. 2002, and the primary end point was an improvement in clinical outcome at 1 month after entry. Results: The patients with SSc in the study showed higher percentages of lower education (69.2%) and working class (63.5%), and reported that the most common life event in adults was di- vorce or separatio n from spou se, while in ado lescent was difficu lt home cond itions. A favourab le respon se was noted in all patients who participated in the study; Remission was achieved in 35, while 17 showed some improvement. Conclu- sions: We conclude that life events were causally related to the onset of SSc and psychoeducation combinated with conventiona l TDD led to a remission in the majority of patients. Keywords: Psychosomatic Medicine, Syste mic Sclerosis (SSc), Life Events, Psychoeducation 1. Introduction Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a systemic connective tissue disease and a chronic and potentially life threatening condition characterized by vascular abnormalities and fibrosis of the skin and multiple organs [1]. Many factors, such as environmental factors, can lead to immunologic system disturbances and vascular changes. It has been reported on our previous research that social and psy- chological stresses may trigger these disturbances and changes [2], and conventional thoracic duct lymphatic drainage therapy (TDD) for the SSc patients has been proven effective [3]. Few data relating to a precise psy- chological event or events underlying the onset of SSc are available, and this study was set up to determine whether life events had been causally related to the onset of SSc and to determine whether psychoeducation com- binated with TDD had led to an improvement in the SSc. 2. Patients and Methods 2.1 Patients A total of 52 patients with SSc (mean age 53.6 ± 10.2 years, mean disease duration 3.8 ± 2.3 years), includ- ing 33 with diffuse cutaneous scleroderma and 19 with limited cutaneous scleroderma, were included in the study. Patients were admitted to the Department of In- ternal Medicine in the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University Medical School, Hangzhou, China, between December 2002 and October 2009 for a routine fol- low-up evaluation of SSc. Their diagnoses of SSc met the American College of Rheumatology criteria [4]. For these patients, the following epidemiological data were recorded: age, disease duration, previous psychopa- thology, current treatments, and socioeconomic status. Scleroderma was further categorized as diffuse or limited scleroderma as defined by LeRoy et al. [5]. Goldthorpe and Hope’s [6] occupational classification was used to distribute the patients into two categories (middle-upper social class and working class), and their education levels also were evaluated [7]. The psychoeducation we did, as an adjunct to conventional TDD, started in Dec. 2002, and all 52 patients who signed informed consent form, were on TDD with a satisfactory efficacy.  Life Events and Psychoeducation in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis 170 2.2 Investigation of Life Events and Psychoeducation A brief life-history was obtained in all cases. The em- phasis was on the previous health of the patient or mem- bers of the immediate family, death of anyone close to the patient, difficulties experienced during different pe- riods of their life, their relationships with others in the family, at school or at work, problems with friends, their hopes and ambitions. A mother’s undue concern for her child, learning difficulties (due to visual or auditory dis- ability or dyslexia) and unsatisfactory scholastic achieve- ment, stability of marriage, change in job conditions, adjustment to retirement, isolation and loneliness may be of importance. If a possible connection between an event and the onset of the SSc was identified, its importance was discussed in detail with the patient. Each patient also underwent a psychiatric assessment to look for the pres- ence / a history of psychiatric illness. The salient features of the history were reported to the rheumatologist, who saw the patient again and concluded the consultation, in order to reassure the patient that their problem was rheumatological. 2.3 Assessment of Outcome All assessments as to clinical outcome were carried out by the responsible rheumatologist in simple terms of re- mitted, improved, and not improved or on-going [3]. They were based on his previous experience with the patient, estimation of the degree of reduction of symp- toms and disability, the ability to return to normal activi- ties and the quality of life of the patient. The psychiatrist was also involved in the final assessment. 3. Results 3.1 Patient Characteristics The entire sample in the study was composed of 52 pa- tients with a mean age of 53.6 ± 10.2 years and a mean disease duration of 3.8 ± 2.3 years. The female-to-male ratio was about 4:1. Table 1 reports the main clinical and laboratory test features and family status. All 52 patients were on TDD with a satisfactory efficacy. None of the patients was receiving psychiatric care at the time of the study. 3.2 Significant Life Events A significant life event was identified in 45 out of the total of 52 patients; this was usually associated with a good outcome. The most common life events in adults and in children and young patients are listed in Box 1. 3.3 Clinical Outcome The outcome was favourable in all 52 patients (Ta ble 2 ). A favourable outcome was classified as remitted (full and satisfactory response leading to early discharge), Box 1. The most common life events in adults and in chil- dren and young patients Significant life events In adults: ·divorce or separation from spouse ·incapacitating illness in patient or close relative ·a bereavement seriously affecting the patient ·moving to new surroundings In children and young patients: ·difficult home conditions ·serious school difficulties, eg, math calculation ·isolation at home or school Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the patients with SSc N = 52 Cutaneous involvement Diffuse 33 Limited 19 Arthritis 10 Skin ulcers 8 Esophageal involvement 14 Pulmonary fibrosis (computed tomography) 19 Forced vital capacity < 80% 12 Antinuclear antibodies 15 Anti-Scl 70 antibodies 12 Serum creatinine, mean ± S.D. (μmol/L) 76 ± 10 Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, mean ± S.D.(mm/h) 28 ± 13 C-reactive protein, mean ± S.D.(mg/L) 21 ± 8 Family status Spouse or living partner 31 Alone 21 Children at home 23 Paid job 29 13+yr of education 16 Lower education 36 Middle-upper social class 11 Working class 33 Table 2. Clinical outcome of SSc patients at 1 month after treatment Therapeutic strategy No of patients Sex (F:M) Age range (years) Remitted Improved Not improved TDD combinated therapy 52 40:12 15~69 35 17 0 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Life Events and Psychoeducation in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis 171 improved (condition improved but discharge without supervision not possible), or not improved [3]. These patients tended to respond favourably to psychoeducation combinated with TDD (35/52 patients), indicating the TDD plus psychoeducational intervention being a better solution to SSc. 3.4 Psychological Diagnosis Psychological diagnoses [8] (Table 3) showed the usual range of disorders seen in a group of patients, with the largest number being in the minor depressive and anxiety category (17 patients). However, no psychological diag- nosis was evident in 11 patients. Psychoses were found in four patients. Psychological diagnoses were scattered among the various subtypes of SSc without any particu- lar pattern. No relationship was identified between the psychological diagnosis and clinical types of SSc. 4. Discussion Although what causes SSc still is not very clear yet, many now agree that the disease may occur when the immune system becomes disordered, attacking the mye- lin surrounding nerve fibers. Focusing on biology, re- searchers suspect these attacks may initially be triggered by infection with a virus, perhaps picked up early in life. However, social and psychological factors are well- documented to play a role in the causation of immune disorders, and there might be a connection of stress to SSc as well [2]. An adverse life event may be important in understanding the mode of onset of SSc. Such an event may be one that the individual has construed as being threatening, damaging, or even dangerous, and for which there appears to be no solution. This experience of an adverse life event may result in distress and /or conflict leading to mental or physical change or a combination of the two. In the latter instance it has become customary to speak of a psychosomatic disorder [9]. Emotional reactions to the significant life events(box1) are inevitable, and they often have serious effects on the patient and his family. In many cases they may be re- sponsible for the onset of SSc in terms of suffering that is greater than that caused by the physical effects of SSc [10]. Emotional disturbance may be particularly severe and prolonged if the patient fails to receive adequate counselling and support. The emotional and relationship problems associated with SSc have not always been fully appreciated by the medical profession, which has tended to concentrate on the physical effects of this disease [11]. Yet the psychological problems of SSc often cause more suffering than the physical effects. We recommend that more attention should be paid to this aspect of the disease in terms of both clinical care and research [2]. In the study, most of the SSc patients tended to re- spond favourably to our psychoeducational intervention (35 patients), which served as an adjunct to conventional TDD therapy. In the patients showing a good response, a new optimism emerged rapidly and they were both satis- fied and confident. Inquiry from a relative or friend con- firmed this impression. The possible factors contributing to the improvements are listed in Box 2. By increased insight we mean enhanced self-knowledge and a better understanding by the patient of circumstances prevailing at the time of the onset of the SSc. The conclusion that emerges from this study is that an adverse life event had continued to affect the emotional state of nearly four-fifths of the patients with SSc and this in turn played a major role in the progress of the dis- order and its resistance to treatment. However, no rela- tionship was identified between the psychological diag- nosis and clinical types of SSc. Such a psychological intervention could usefully be included in the normal SSc assessment, as it should both improve patient care and be cost effective [12]. To our knowledge this is the first re- search yet in China from a rheumatology-psychiatry li- aison team [13]. The procedure described above has a simplicity and commonality which may recommend it for further consideration and research. 5. Acknowledgements This study was supported by grant No. B340406052 from the Science and Technology Foundation of Shanghai Railway Bureau (Hangzhou, China) to Drs. Huang and Chen. Table 3. Psychological diagnosis Diagnosis n Psychosis: Major depressive disorder 3 Delusional disorder 1 Minor depressive or anxiety disorder 17 Bereavement 6 Psychosocial problems 9 Clinical disorder (ie, psychological concern over a medical illness) 5 No diagnosis 11 Box 2. The possible factors con tributing to th e improvements Factors contributing to improvements ·increased insight ·opportunity to talk and ask question ·evidence of emotional reaction during interview ·attention received ·the power of suggestion ·placebo effect Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Life Events and Psychoeducation in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis 172 We are grateful to Dr. Qie Hong-li for her helpful comments on the paper. REFERENCES [1] V. D. Steen and T. A. Medsger, “Severe Organ Involve- ment in systemic Sclerosis with Diffuse Scleroderma,” Arthritis & Rheumatism, Vol. 43, No. 11, 2000, pp. 2437- 2444. [2] Y. Chen, J. Z. Huang, Y. Qiang, J. Wang and M. M. Han, “Investigation of Stressful Life Events in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis,” Journal of Zhejiang University Sci- ence B, Vol. 9, No. 11, 2008, pp. 853-856. [3] J. Z. Huang and J. Zhu, “Thoracic Duct Drainage Ther- apy,” Chinese Publishing House of International Broad- cast, Beijing, 1991, pp. 217-223. [4] A. T. Masi, G. P. Rodnan and T. A. Medsger, “Prelimi- nary Criteria for the Classification of Systemic Sclerosis (Scleroderma),” Arthritis & Rheumatism, Vol. 23, No. 5, 1980, pp. 581-590. [5] E. C. LeRoy, C. Black and R. Fleischmajer, “Scleroderma (Systemic Sclerosis): Classification, Subsets, and Patho- genesis,” Journal of Rheumatology, Vol. 15, No. 2, 1988, pp. 202-205. [6] J. H. Goldthorpe and K. Hope, “The Social Grading of Occupations,” Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1974, pp. 235-238. [7] B. Archenholtz, E. Nordborg and T. Bremell, “Lower Level of Education in Young Adults with Arthritis Start- ing in the Early Adulthood,” Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology, Vol. 30, No. 6, 2001, pp. 353-355. [8] American Psychiatric Association, “Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV),” APA, Washington, D.C., 1994. [9] C. C. Chen, A. S. David and H. Nunnerly, “Adverse Life Events and Breast Cancer: Case Control Study,” British Medical Journal, Vol. 311, No. 7019, 1995, pp. 1527- 1530. [10] S. R. Dube, D. Fairweather, W. S. Pearson, V. J. Felitti, R. F. Anda and J. B. Croft, “Cumulative Childhood Stress and Autoimmune Diseases in Adults,” Psychosomatic Med- icine, Vol. 71, No. 2, 2009, pp. 243-250. [11] U. M. Anderberg, I. Marteinsdottir, T. von Theorell and L. Knorring, “The Impact of Life Events in Female Patients with Fibromyalgia and in Female Healthy Controls,” Eu- ropean Psychiatry, Vol. 15, No. 5, 2000, pp. 295-301. [12] T. N. Hyphantis, N. Tsifetaki, C. Pappa, P. V. Voulgari, V. Siafaka and M. Bai, “Clinical Features and Personality Traits Associated with Psychological Distress in Systemic Sclerosis Patients,” Journal of Psychosomatic Research, Vol. 62, No. 1, 2007, pp. 47-56. [13] K. Mulligan and S. Newman, “Psychoeducational Inter- ventions in Rheumatic Diseases: A Review of Papers Published from September 2001 to August 2002,” Cur- rent Opinion in Rheumatology, Vol. 15, No. 2, 2003, pp. 156-159. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH |