Open Journal of Psychiatry, 2012, 2, 272-280 OJPsych http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpsych.2012.24038 Published Online October 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojpsych/) Discontinuation of antidepressant therapy among patients with major depressive disorder Shreya Davé1*, Peter Classi2, Trong Kim Le2, Andrew Maguire1, Susan Ball2,3 1Epidemiology and Database Analytics, United BioSource Corporation, London, UK 2Lilly Research Laboratories, Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, USA 3Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, USA Email: *shreya.dave@unitedbiosource.com Received 27 June 2012; revised 29 July 2012; accepted 9 August 2012 ABSTRACT Objective: Patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) often discontinue antidepressant therapy pre- maturely risking relapse, despite United Kingdom (UK) guidelines recommending therapy for up to at least six months after remission. More information is needed on the patterns of antidepressant discontinua- tion in UK primary care. Objectives of the study were to assess the patterns, incidence and predictors of therapy discontinuation among MDD patients initi- ating treatment with selective serotonin reuptake in- hibitors (SSRIs). Methods: This was a retrospective cohort study using general practices registered with the General Practice Research Database (GPRD). 15,274 patients with MDD receiving a first ever pre- scription (index) for an SSRI between 2006-2008 were identified in GPRD. Discontinuation (including tem- porary gaps) and cessation of antidepressant therapy were examined over follow-up. Predictors of inci- dence of discontinuation in the six months after index were assessed. Results: Incidence of discontinuation of antidepressant therapy over follow-up was 80.05 per 100 person years (95% CI 78.94 - 81.17). At six months after index 42% of patients had discontinued and 33% had ceased therapy altogether. Lower dis- continuation of index SSRI therapy in the first six months after initiation was associated with higher age, higher body mass index (BMI), and comorbid irrita- ble bowel syndrome. Higher discontinuation was as- sociated with paroxetine or fluoxetine at index, and a more recent index calendar year. Conclusions: There is a significant risk of discontinuation of antidepres- sant therapy in the 6 months after initiation of treat- ment for MDD. This finding requires awareness by the general practitioner (GP) to ensure implementa- tion of optimal treatment regimens, and minimization of therap y non-complian ce among MDD patients . Keywords: Anti-Depressive Medications; Serotonin Uptake Inhibitors; Major Depressive Disorder; Medication Adherence; General Practice 1. INTRODUCTION Approximately 13% of general practice attendees in the United Kingdom (UK) suffer major depressive disorder (MDD) [1]. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are recommended as a first-line treatment option due their relatively low cost, good efficacy and safety [2]. Therapy is recommended until depressive symptoms have been managed, and the patient is in remission. However, continuation of therapy is recommended for at least six months after remission to reduce risk of relapse [2], and can be up to two years maintenance treatment if the patient has chronic depression, severe functional im- pairment, or is at risk of severe consequences such as suicide [2]. Premature discontinuation of antidepressant treatment is associated with a high risk of relapse and adverse consequences [3] including rapid re-onset of future depressive episodes, that can be more chronic and severe than if complete remission had been achieved, and moreover this risk is enhanced with untreated re- sidual symptoms following a depressive episode [4,5]. Hence, appropriate clinical management and reliable follow-up of patients suffering a depressive episode are important. Discontinuation of antidepressant treatment can occur for several reasons [6]. Patients in remission from de- pression may discontinue therapy because they believe they can proceed with a non-depressed life without tak- ing drugs. Patients may also discontinue due to an inade- quate response to their initial treatment [7], without im- plementation of appropriate alternative second-step treat- ment strategies [8]. Furthermore, patients may be non- compliant with their medication or discontinue because of adverse side effects [9,10]. If we are to assess the po- tential unmet need in antidepressant treatment, it is per- *Corresponding author. OPEN ACCESS  S. Davé et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 272-280 273 tinent to examine patterns of therapy discontinuation and associated factors. The aim of this study was to assess incidence of discontinuation (including temporary treat- ment gaps) and cessation (discontinuation without sub- sequent therapy resumption) of antidepressant treatment among new initiators of SSRI treatment in UK primary care, and examine predictors of discontinuation in the six months after therapy initiation. 2. METHODS 2.1. Study Design and Data Source This was a retrospective cohort study using data from the General Practice Research Database (GPRD) (www.cprd.com). GPRD is a large primary care database containing anonymised patient level medical and demo- graphic information on approximately 8% of the UK population from 630 general practices. Containing ap- proximately 11 million patients and 67 million patient years of data, the GPRD is a good resource for longitu- dinal epidemiological research, and has been widely used for studies on depression [11-14]. The database contains information on diagnoses, symptoms, prescriptions, spe- cialist referrals, test results, demographics, and adminis- trative information. 2.2. Study Population We extracted a cohort of adult patients who had received a first-time prescription for an SSRI between 01/06/2006 and 31/12/2008; this was the enrolment period and the date of first SSRI prescription was the index date. Pa- tients were followed-up until 25/10/2010, where data were available. Patients had to have registered with the practice at least 12 months before the index date to avoid collecting data from patients recently transferred into a practice who were likely to have historical diagnoses updated to their medical record [15]. Patients with prior prescrip- tions for antidepressants were excluded to ensure only new initiators of MDD therapy were included. In addi- tion, inclusion was limited to patients with an index date after the practice became “up-to standard” (i.e. had good quality computerised data) (www.cprd.com), and those who were deemed “acceptable” according to GPRD’s da- ta quality criteria. Our final study cohort comprised of patients with a specific Read code [16] for MDD or a positive score entry for MDD on a recommended [2] depression screening ques- tionnaire (Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)—cut-off of 10 [17], Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)—cut-off of 11 [18], or the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)—cut-off of 20 [19]) in the period from six months before to three months after the index date. This window allowed inclusion of patients experi- encing a time lag between diagnosis and treatment with SSRIs, and also for general practitioners (GPs) who en- tered a diagnosis after treatment had commenced. The PHQ is the most widely used measure and has been validated in UK primary care, showing high sensitivity (91.7%) and specificity (78.3%) for detection of MDD when compared with a gold-standard diagnostic clinical interview [20]. 2.3. Treatment Outcomes The MDD treatment trajectory (using relevant drug code lists) was tracked among patients from the index date to the end of follow-up. Discontinuation was defined as discontinuation of an antidepressant prescription without receiving another within 60 days of exhausting the sup- ply of the prior prescription. If there were any other ad- jacent (<60 days) therapy outcomes such as a drug switch, dose increase or adjunctive therapy then this was not classified as a discontinuation of the previous medi- cation. Thus, discontinuation represented a gap in the treatment trajectory if the patient subsequently resumed MDD therapy, or was a cessation of therapy if no further antidepressant prescriptions were received up to the end of patient follow-up (to determine this accurately patients were required to have at least six months of follow-up after discontinuing with no prescriptions for antidepres- sants during that period). Persistence on therapy was defined as remaining on antidepressants (not discontinuing as above) in the 12 months after index [21], with allowable gaps of <60 days in treatment. 2.4. Covariates Covariates included patient age at index, gender, and several baseline variables including depression severity, anxiety, alcohol and substance misuse, and chronic pain conditions (including irritable bowel syndrome, diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuropathy, trigeminal neural- gia, lumbar radiculopathy, cervical radiculopathy, com- plex regional pain syndrome, spinal cord injury, fibro- myalgia, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, migraine, chronic low back pain, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthropathy, and interstitial cystitis). These comorbidities were indentified using relevant Read code lists. We cal- culated the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [22], an established measure of general disease burden that has been adapted for use with UK primary care databases [23]. These covariates were selected due to evidence of their association with depression and/or its treatment. For example, the concurrent treatment of pain conditions with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can reduce the efficiency of SSRIs [24]. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  S. Davé et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 272-280 274 2.5. Statistics Descriptive statistics, including frequency distributions, percentages, means (SD) and medians (10th to 90th per- centiles) were used to describe baseline patient charac- teristics. Among patients with at least a year of follow-up data we calculated: 1) Persistence [21] at 12 months on the index SSRI, any SSRI, and any antidepressant; 2) Frequency of patients by duration of index medication; and 3) Median length of index therapy in the year after index. Among all patients, Kaplan Meier methods were used to describe the cumulative failure pattern for: 1) Index SSRI therapy discontinuation; and 2) cessation of any antidepressant therapy. This was assessed from the index date up to the end of follow-up. Incidence of discontin- uation of the index SSRI, any SSRI, and any antide- pressant was calculated using total person-time at risk as a denominator. The bivariate association of each covariate with inci- dence of discontinuation of the index SSRI in the six months after therapy initiation was tested individually using Poisson regression. Associations significant at the p = 0.10 level in the bivariate analysis were tested in an adjusted Poisson regression model to assess independent predictors of incidence of discontinuation of the index SSRI in the six months after therapy initiation. Wald tests aided modeling. This study was reviewed and approved by the Inde- pendent Scientific Advisory Committee (protocol num- ber 10_138). 3. RESULTS 94,932 eligible patients received a first-time SSRI pre- scription in the enrolment period. Of these, 2059 had a recent specific MDD Read code entry, and an additional 13,215 scored above the cut-off for MDD on the PHQ, HADs and/or BDI-II, resulting in a final study cohort of 15,274 patients. 13,927/15,274 (91.2%) patients had at least a year of follow-up data after index. Median length of follow-up was 33.8 months (10th-90th percentiles 14.0 - 48.2), median age was 38.0 years (10th-90th percentiles 21.0 - 63.0), and 59.6% were female (Table 1). Further characteristics are described in Table 1. Persistence (at 12 months) for the index SSRI, for any SSRI and for any antidepressant was 2075/13,927 (14.9%), 3251/13,927 (23.3%) and 3516/13,927 (25.3%) respectively. Median duration of index SSRI therapy in the year after index was 61 days (10th to 90th percentiles 28 to 365, N = 13,927). Figure 1 shows 4744/13,927 (34%) patients remained on the index SSRI for 28 - 30 days. Figure 2 shows Kaplan Meier failure curves for dis- continuation of the index medication, and cessation of all Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics (N = 15,274). Variable Numbers of patients (%)a Follow-up: >1 year 13,927 (91.2%) Median follow-up (percentiles: 10th, 90th) (m onths) 33.8 (14.0 - 48.2) Median age at index (percentiles: 10th, 90th) (years) 38.0 (21.0 - 63.0) Age group at index (years) 18 - 29 4526 (29.6%) 30 - 39 3512 (23.0%) 40 - 49 3087 (20.2%) 50 - 59 2097 (13.7%) 60 - 69 1023 (6.7%) 70 - 79 643 (4.2%) 80+ 386 (2.5%) Gender: Female 9100 (59.6%) Index SSRI Citalopram 7468 (48.9%) Escitalopram 555 (3.6%) Fluoxetine 6477 (42.4%) Paroxetine 161 (1.1%) Sertraline 612 (4.0%) Mean body mass index (index value) 27.7 (SD 6.6) History of depressive disorder 2256 (14.8%) Anxiety disorder in past 12 months 2144 (14.0%) Alcohol and substance abuse in past 12 months 2017 (13.2%) Chronic pain conditions 3278 (21.5%) Irritable bowel syndrome 1040 (6.8%) Charlson comorbidity index: 0 10,758 (70.4%) 1 3271 (21.4%) 2 644 (4.2%) 3 345 (2.3%) 4 130 (0.9%) 5 62 (0.4%) 6+ 64 (0.4%) Median CCI (percentiles: 10th, 90th) (CCI value) 0.0 (0.0 - 1.0) aUnless otherwise specified; Note: Comorbidities included in the table are those associated with discontinuation of antidepressant therapy in the bivariate analysis. antidepressant therapy. At three months after index 25% of patients had discontinued their index drug; at six months this was 42%, at 12 months 57%, at 24 months 64% and by 48 months 67% had discontinued their index medication. Twenty-two percent of patients had treat- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  S. Davé et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 272-280 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 275 05001000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 Numbers of patients 028 56 84 112140 168 196 224 252 280308 336 364 Dur a t ion of inde x t h er apy ( da y s ) Figure 1. Frequency of patients by duration of index therapy in first year after index (N = 13,927). 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1 Proportion failing 0 10 20 30 40 50 Time from index (months) index_discon cessation_the Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier failure curves (hazards) for first event of discontinuation and cessation of antidepressant therapy after index. ment cessation at three months after index, 33% at 6 months, 46% at 12 months, 59% at 24 months, and 69% at 48 months after index. When considering the entire period of follow-up, over- all incidence of discontinuation of the index SSRI was 51.23 per 100 person years (95% CI 50.23 - 52.25); any SSRI was 77.45 per 100 person years (95% CI 76.32 - 78.60); and any antidepressant was 80.05 per 100 per- son years (95% CI 78.94 - 81.17). Incidence of cessation of all antidepressant therapy over the follow-up period was 41.83 per 100 person years (95% CI 40.99 - 42.70). Table 2 shows a multivariable analysis of incidence of index therapy discontinuation in the first six months. Patients prescribed fluoxetine at index were 19% more likely (p ≤ 0.001) to discontinue compared with those starting on citalopram. Patients prescribed paroxetine at OPEN ACCESS  S. Davé et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 272-280 276 Ta bl e 2 . Multivariable analysis of incidence of discontinuation of first SSRI therapy in the six months after therapy initiation (N = 5641). Variable Events, No Person years at riskUnadjusted incidence rate ratio (95% CI) Adjusted incidence rate ratio (95% CI) Index SSRI Citalopram 1086 4602.30 Escitalopram 74 367.75 0.85 (0.67 - 1.08) 0.90 (0.71 - 1.14) Fluoxetine 1103 3999.69 1.17 (1.08 - 1.27)*** 1.19 (1.09 - 1.30)*** Sertraline 24 88.26 1.15 (0.77 - 1.73) 1.06 (0.71 - 1.59) Paroxetine 111 403.59 1.17 (0.96 - 1.42) 1.25 (1.03 - 1.52)* Age at index (years) 2398 9461.58 0.99 (0.98 - 0.99)*** 0.99 (0.99 - 0.99)*** Enrolment year 2006 634 3102.05 2007 980 3907.02 1.23 (1.11 - 1.36)*** 1.21 (1.10 - 1.34)*** 2008 784 2452.51 1.56 (1.41 - 1.74)*** 1.53 (1.38 - 1.70)*** Body mass index (index value) 2398 9461.58 0.99 (0.98 - 0.99)*** 0.99 (0.98 - 0.99)*** Irritable bowel syndrome (yes) 166 757.81 0.85 (0.73 - 1.00)* 0.85 (0.72 - 0.99)* ***p ≤0.001; **p ≤ 0.01; *p ≤ 0.05. index were 25% (p = 0.03) more likely to discontinue compared with patients prescribed citalopram at index. Likelihood of discontinuation declined with increased age (p ≤ 0.001). Discontinuation was more likely among those initiating therapy in more recent years with a 53% (p ≤ 0.001) and 21% (p ≤ 0.001) higher likelihood of discontinuation respectively among those enrolled in 2008 and 2007 compared with those enrolled in 2006. A lower likelihood of discontinuation was associated with a higher BMI (p ≤ 0.001), and presence of IBS (p = 0.04). 4. DISCUSSION This study provides much needed UK data on discon- tinuation of antidepressant therapy among patients with MDD who were new initiators of treatment with SSRIs. Discontinuation was assessed as both temporary gaps in the depression treatment trajectory as well as true cessa- tion of therapy, since gaps in treatment can indicate in- adequate or under-treatment of depression. There are varying definitions of discontinuation of antidepressant therapy in the literature representing cessation (i.e. no further antidepressant prescription refills), and discon- tinuation defined using allowable gaps in prescriptions of <30 days [25,26], <90 days [27], and <180 days [28]. In this study we opted for a 60 day allowable gap in an- tidepressant prescribing after which the patient was deemed to have discontinued. 4.1. Summary of Main Findings Only a quarter of patients persisted on antidepressant medication up to at least one year after initiating MDD treatment, and 15% continued on their index SSRI medi- cation at least up to this time. A high proportion of pa- tients had only approximately a month’s duration for their index therapy, suggesting many patients received a one-off antidepressant prescription. At six months after treatment initiation 42% of patients had discontinued their index drug, and 33% had cessation of therapy with- out subsequent resumption. Discontinuation of the index medication showed an increasing trend in more recent years. Higher discontinuation of the index treatment was associated with an index medication of fluoxetine or paroxetine compared with citalopram. Lower disconti- nuation of index medication was associated with older age, higher BMI, and IBS. 4.2. Study Cohort Only 2059 and 13,215 of the 94,932 patients on SSRIs had a diagnostic Read code entry, and positive depress- sion screening questionnaire score for MDD respectively. Since antidepressants are often used to treat several other disorders (e.g. Anxiety disorders, and eating disorders) this may account for some of the remaining patients who were not identified as MDD patients. The relatively small proportion of the final study cohort defined by a Read code entry for MDD likely reflects evidence of a trend in GPs recording symptom rather than diagnostic depression codes in the UK [29]. However, use of re- commended [2] validated depression screening question- naire scores allowed us to identify a population of MDD patients with high sensitivity and specificity [20]. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  S. Davé et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 272-280 277 4.3. Comparison with Existing Literature Other studies have also shown significant early discon- tinuation of first-time antidepressant therapy, with be- tween 30% - 53% of MDD patients discontinuing treat- ment during the six months after initiation [28,30,31]; these percentages are comparable to those observed in our study. A similar extent of discontinuation (37% - 56%) was observed among those treated for a new epi- sode of depression, but who were not necessarily new initiators of therapy [32-34]. The reasons for discontinuation are manifold. The most common reason for discontinuation given by pa- tients in one study was “feeling better” [30]. Another study showed compliance with antidepressant treatment was twice as high among patients with high levels of polypharmacy compared with those with lower levels of polypharmacy [33]. Therefore, implementation of alter- native strategies for inadequate responders to antide- pressant therapy may enhance compliance and reduce the likelihood of discontinuation. Aikens et al. (2005) [35] found patient skepticism towards antidepressant therapy was a strong predictor of discontinuation. Medication side-effects, the most common of which are headache and nausea [9], have also been shown to be associated with premature discontinuation of antidepressants [9, 31-35]. Our multivariable analysis assessed factors associated with discontinuation of index therapy in the six months after therapy initiation. We chose this time window since it represented early discontinuers, and patients clearly falling short of the recommended six months of antide- pressant maintenance treatment post remission [2]. As in our study, other studies have also found older age to be associated with higher compliance [33] and longer-term [36] antidepressant therapy. Patient beliefs about medication are an important predictor of therapy adherence [37]. Another study by Aikens et al. (2008) [38] on patient beliefs about antidepressants found older pa- tients were more likely to perceive a need for treatment and hence were less likely to discontinue therapy. Fur- thermore, patients with a relatively low comorbidity bur- den were likely to report an attitude of perceived harm- fulness related to antidepressant therapy [38], which may explain our findings of an association between presence of a comorbid condition (IBS) and a lower likelihood of discontinuation. Moreover, a higher comorbidity burden is likely to be associated with more contact with the GP, which may also increase the opportunity for treatment for depression. Higher BMI was associated with a lower likelihood of discontinuation. This may be explained by the fact that patients remaining on SSRI treatment can be likely to suffer weight gain as a side effect [39]. However, there is also evidence that weight gain is associated with lower satisfaction and lower adherence to medication [40] and may indeed be a long-term predictor of discontinuation beyond the six-month window we examined. The results also suggest an increasing trend in discon- tinuation of antidepressant therapy with more recent study enrolment years; this points to the need for imple- mentation of better adherence strategies and improved patient-doctor communication. Another possible expla- nation could be a negative perception about antidepres- sant efficacy resulting from research showing limited difference between antidepressants and placebo [41,42]. Patients prescribed paroxetine or fluoxetine at index were more likely to discontinue in the first six months compared with patients prescribed citalopram. This may suggest relatively higher intolerability and adverse events associated with paroxetine and fluoxetine compared with citalopram [43,44], however there is little substantive evidence for differences in overall intolerability between SSRIs among non-select patients groups [45]. Further- more, since patients were not randomly assigned to treat- ment, differences in unmeasured characteristics between patients prescribed citalopram, fluoxetine and paroxetine may explain the differing discontinuation rates. 4.4. Study Strengths and Limitations 1) It is possible that MDD patients without a diagnos- tic Read code entry or a depression screening question- naire score entry indicating MDD were missed; 2) We were not able to identify possible antidepressant prescriptions received from mental health specialists. However, we would expect a relatively small proportion of patients, mainly those who were treatment-resistant, to have been likely to be under the sole care of a specialist rather than their GP; 3) Reasons for discontinuation were not available in GPRD. Future studies using GPRD may utilize addi- tional free text information which may provide such in- formation; 4) GPRD contains information on drugs prescribed and does not verify whether the medication was dis- pensed or taken by the patient; 5) The results cannot be generalized to MDD patients who are not new initiators of antidepressant therapy, since their treatment course may differ from those on first time antidepressant therapy; 6) It was beyond the scope of the study to examine psychological therapies; future studies may consider this to determine whether patients who discontinue pharma- cological treatment early are likely to be receiving psy- chological therapies instead. 5. CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS There is a significant risk of discontinuation of antide- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  S. Davé et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 272-280 278 pressant therapy in the six months after initiation of treatment for MDD. This requires awareness by the cli- nician both in terms of ensuring an optimal treatment regimen is implemented, and also in helping minimize non-compliance from MDD patients in persisting with their prescribed therapy [31]. GPs should monitor their MDD patients initiating pharmacotherapy for presence of depressive symptoms, and adhere to recommended guidelines by continuing antidepressant therapy for up to at least six months after remission to avoid risk of re- lapse of depression. Moreover, the importance of con- tinuing treatment even if their depressed mood has im- proved should be appropriately communicated to the patient. GPs should aim to minimise discontinuation and optimise adherence to antidepressant therapy by active follow-up of patients suffering potential inadequate or non-response to pharmacotherapy, and those experienc- ing adverse side effects from their antidepressant medi- cation. If such problems are identified, GPs should im- plement alternative treatment strategies such as a dose increase, therapy switch, augmentation or referral to a specialist. REFERENCES [1] King, M., Nazareth, I., Levy, G., Walker, C., Morris, R., Weich, S., Bellon-Saameno, J.A., Moreno, B., Svab, I., Rotar, D., Rifel, J., Maaroos, H.I., Aluoja, A., Kalda, R., Neeleman, J., Geerlings, M.I., Xavier, M., de Almeida, M.C., Correa, B. and Torres-Gonzalez, F. (2008) Preva- lence of common mental disorders in general practice at- tendees across Europe. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 192, 362-367. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.039966 [2] NICE (2009) Depression: The treatment and management of depression in adults (Clinical Guideline 90). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, London. [3] Claxton, A.J., Li, Z. and McKendrick, J. (2000) Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment in the UK: Risk of relapse or recurrence of depression. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 177, 163-168. doi:10.1192/bjp.177.2.163 [4] Judd, L.L., Paulus, M.J., Schettler, P.J., Akiskal, H.S., Endicott, J., Leon, A.C., Maser, J.D., Mueller, T., Solo- mon, D.A. and Keller, M.B. (2000) Does incomplete re- covery from first lifetime major depressive episode herald a chronic course of illness? American Journal of Psy- chiatry, 157, 1501-1504. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.9.1501 [5] Judd, L.L., Akiskal, H.S., Maser, J.D., Zeller, P.J., Endi- cott, J., Coryell, W., Paulus, M.P., Kunovac, J.L., Leon, A.C., Mueller, T.I., Rice, J.A. and Keller, M.B. (1998) Major depressive disorder: A prospective study of resid- ual subthreshold depressive symptoms as predictor of rapid relapse. Journal of Affective Disorders, 50, 97-108. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00138-4 [6] Mitchell, A.J. and Selmes, T. (2007) Why don’t patients take their medicine? Reasons and solutions in psychiatry. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 13, 336-346. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.106.003194 [7] Fortney, J.C., Pyne, J.M., Edlund, M.J., Stecker, T., Mit- tal, D., Robinson, D.E. and Henderson, K.L. (2011) Rea- sons for antidepressant nonadherence among veterans treated in primary care clinics. Journal of Clinical Psy- chiatry, 72, 827-834. doi:10.4088/JCP.09m05528blu [8] Rush, A.J., Trivedi, M.H., Wisniewski, S.R., Nierenberg, A.A., Stewart, J.W., Warden, D., Niederehe, G., Thase, M.E., Lavori, P.W., Lebowitz, B.D., McGrath, P.J., Rosenbaum, J.F., Sackeim, H.A., Kupfer, D.J., Luther, J. and Fava, M. (2006) Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: A STAR*D report. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 1905-1917. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.11.1905 [9] Anderson, H.D., Pace, W.D., Libby, A.M., West, D.R. and Valuck, R.J. (2012) Rates of 5 common antidepres- sant side effects among new adult and adolescent cases of depression: A retrospective US claims study. Clinical Therapeutics, 34, 113-123. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.11.024 [10] Kikuchi, T., Suzuki, T., Uchida, H., Watanabe, K. and Kashima, H. (2011) Subjective recognition of adverse events with antidepressant in people with depression: A prospective study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 135, 347-353. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.07.011 [11] Moore, M., Yuen, H.M., Dunn, N., Mullee, M.A., Mas- kell, J. and Kendrick, T. (2009) Explaining the rise in an- tidepressant prescribing: A descriptive study using the general practice research database. British Medical Jour- nal, 339, b3999. doi:10.1136/bmj.b3999 [12] Wade, A.G., Saragoussi, D., Despiegel, N., Francois, C., Guelfucci, F. and Toumi, M. (2010) Healthcare expendi- ture in severely depressed patients treated with escitalo- pram, generic SSRIs or venlafaxine in the UK. Current Medical Research & Opinion, 26, 1161-1170. doi:10.1185/03007991003738519 [13] Kurd, S.K., Troxel, A.B., Crits-Christoph, P. and Gelfand, J.M. (2010) The risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidal- ity in patients with psoriasis: A population-based cohort study. Archives of Dermatology, 146, 891-895. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.186 [14] Becker, C., Brobert, G.P., Johansson, S., Jick, S.S. and Meier, C.R. (2011) Risk of incident depression in patients with Parkinson disease in the UK. European Journal of Neurology, 18, 448-453. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03176.x [15] Lewis, J.D., Bilker, W.B., Weinstein, R.B. and Strom, B.L. (2005) The relationship between time since registra- tion and measured incidence rates in the General Practice Research Database. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 14, 443-451. doi:10.1002/pds.1115 [16] Chisholm, J. (1990) The Read clinical classification. Bri- tish Medical Journal, 300, 1092. doi:10.1136/bmj.300.6732.1092 [17] Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R.L. and Williams, J.B.W. (2001) The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity meas- ure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 606-613. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  S. Davé et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 272-280 279 [18] Zigmond, A.S. and Snaith, R.P. (1983) The Hospital An- xiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandi- navica, 67, 361-370. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [19] Beck, A.T., Steer, R.A. and Brown, G.K. (1996) Manual for the beck depression inventory-II. Psychological Cor- poration, San Antonio. [20] Gilbody, S., Richards, D., Brealey, S. and Hewitt, C. (2007) Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): A diagnostic meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22, 1596-1602. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0333-y [21] Elliott, W.J., Plauschinat, C.A., Skrepnek, G.H. and Gause, D. (2007) Persistence, adherence, and risk of dis- continuation associated with commonly prescribed anti- hypertensive drug monotherapies. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 20, 72-80. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2007.01.060094 [22] Charlson, M.E., Pompei, P., Ales, K.L. and MacKenzie, C.R. (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic co- morbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and vali- dation. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 40, 373-383. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [23] Khan, N.F., Perera, R., Harper, S. and Rose, P.W. (2010) Ada- ptation and validation of the Charlson Index for Read/ OXMIS coded databases. BMC Famil y Pract ice, 11, 1. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-11-1 [24] Warner-Schmidt, J.L., Vanover, K.E., Chen, E.Y., Mar- shall, J.J. and Greengard, P. (2011) Antidepressant effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are at- tenuated by anti-inflammatory drugs in mice and humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108, 9262-9267. doi:10.1073/pnas.1104836108 [25] Lee, Y.M. and Lee, K.U. (2011) Time to discontinuation among the three second-generation antidepressants in a naturalistic outpatient setting of depression. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 65, 630-637. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02275.x [26] Olfson, M., Marcus, S.C., Tedeschi, M. and Wan, G.J. (2006) Continuity of antidepressant treatment for adults with depression in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 101-108. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.101 [27] Simon, G.E., Von Korff, M., Wagner, E.H. and Barlow, W. (1993) Patterns of antidepressant use in community practice. General Hospital Psychiatry, 15, 399-408. doi:10.1016/0163-8343(93)90009-D [28] Hansen, D.G., Vach, W., Rosholm, J.U., Sondergaard, J., Gram, L.F. and Kragstrup, J. (2004) Early discontinua- tion of antidepressants in general practice: Association with patient and prescriber characteristics. The Journal of Family Practice, 21, 623-629. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmh608 [29] Rait, G., Walters, K., Griffin, M., Buszewicz, M., Peter- sen, I. and Nazareth, I. (2009) Recent trends in the inci- dence of recorded depression in primary care. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 195, 520-524. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.058636 [30] Demyttenaere, K., Enzlin, P., Dewe, W., Boulanger, B., De, B.J., De, T.W. and Mesters, P. (2001) Compliance with antidepressants in a primary care setting, 1: Beyond lack of efficacy and adverse events. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62, 30-33. [31] Lin, E.H., Von, K.M., Katon, W., Bush, T., Simon, G.E., Walker, E. and Robinson, P. (1995) The role of the pri- mary care physician in patients’ adherence to antidepres- sant therapy. Medical Care , 33, 67-74. doi:10.1097/00005650-199501000-00006 [32] Lewis, E., Marcus, S.C., Olfson, M., Druss, B.G. and Pin- cus, H.A. (2004) Patients’ early discontinuation of anti- depressant prescriptions. Psychiatric Services, 55, 494. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.55.5.494 [33] Serna, M.C., Cruz, I., Real, J., Gasco, E. and Galvan, L. (2010) Duration and adherence of antidepressant treat- ment (2003-2007) based on prescription database. Euro- pean Psychiatry, 25, 206-213. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.07.012 [34] Mabotuwana, T., Warren, J., Orr, M., Kenealy, T. and Harrison, J. (2011) Using primary care prescribing data to improve GP awareness of antidepressant adherence issues. Informatics in Primary Care, 19, 7-15. [35] Aikens, J.E., Kroenke, K., Swindle, R.W. and Eckert, G.J. (2005) Nine-month predictors and outcomes of SSRI an- tidepressant continuation in primary care. General Hos- pital Psychiatry, 27, 229-236. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.04.001 [36] Meijer, W.E., Heerdink, E.R., Leufkens, H.G., Herings, R.M., Egberts, A.C. and Nolen, W.A. (2004) Incidence and determinants of long-term use of antidepressants. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 60, 57-61. doi:10.1007/s00228-004-0726-3 [37] Horne, R. (1999) Patients’ beliefs about treatment: The hidden determinant of treatment outcome? Journal of Psy- chosomatic Research, 47, 491-495. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(99)00058-6 [38] Aikens, J.E., Nease Jr., D.E. and Klinkman, M.S. (2008) Explaining patients’ beliefs about the necessity and harm- fulness of antidepressants. The Annals of Family Medi- cine, 6, 23-29. doi:10.1370/afm.759 [39] Hirschfeld, R.M. (2003) Long-term side effects of SSRIs: Sexual dysfunction and weight gain. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64, 20-24. [40] Fakhoury, W.K., Wright, D. and Wallace, M. (2001) Pre- valence and extent of distress of adverse effects of antip- sychotics among callers to a United Kingdom National Mental Health Helpline. International Clinical Psycho- pharmacology, 16, 153-162. doi:10.1097/00004850-200105000-00004 [41] Kirsch, I., Deacon, B.J., Huedo-Medina, T.B., Scoboria, A., Moore, T.J. and Johnson, B.T. (2008) Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: A meta-analysis of data sub- mitted to the Food and Drug Administration. PLOS Me- dicine, 5, e45. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045 [42] Kirsch, I. (2009) Antidepressants and the placebo re- sponse. Epidemiologia e psichiatria sociale, 18, 318-322. [43] Thase, M.E., Ferguson, J.M., Lydiard, R.B. and Wilcox, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  S. Davé et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 272-280 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 280 OPEN ACCESS C.S. (2002) Citalopram treatment of paroxetine-intolerant depressed patients. Depression and Anxiety, 16, 128-133. doi:10.1002/da.10055 [44] Rambelomanana, S., Depont, F., Forest, K., Hebert, G., Blazejewski, S., Fourrier-Reglat, A., Molimard, M. and Moore, N. (2006) Antidepressants: General practitioners’ opinions and clinical practice. Acta Psychiatrica Scandi- navica, 113, 460-467. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00793.x [45] Edwards, J.G. and Anderson, I. (1999) Systematic review and guide to selection of selective serotonin reuptake in- hibitors. Drugs, 57, 507-533. doi:10.2165/00003495-199957040-00005

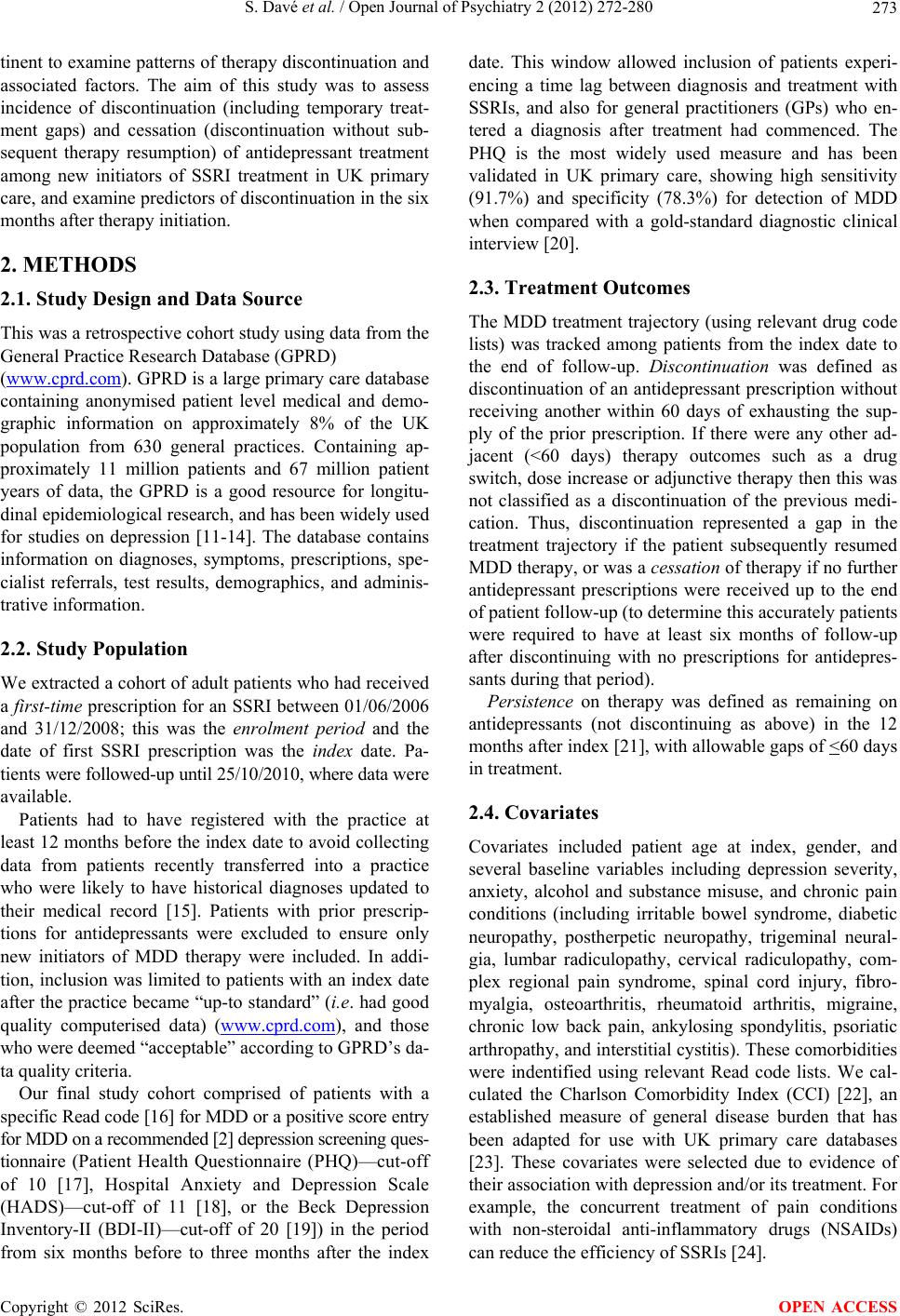

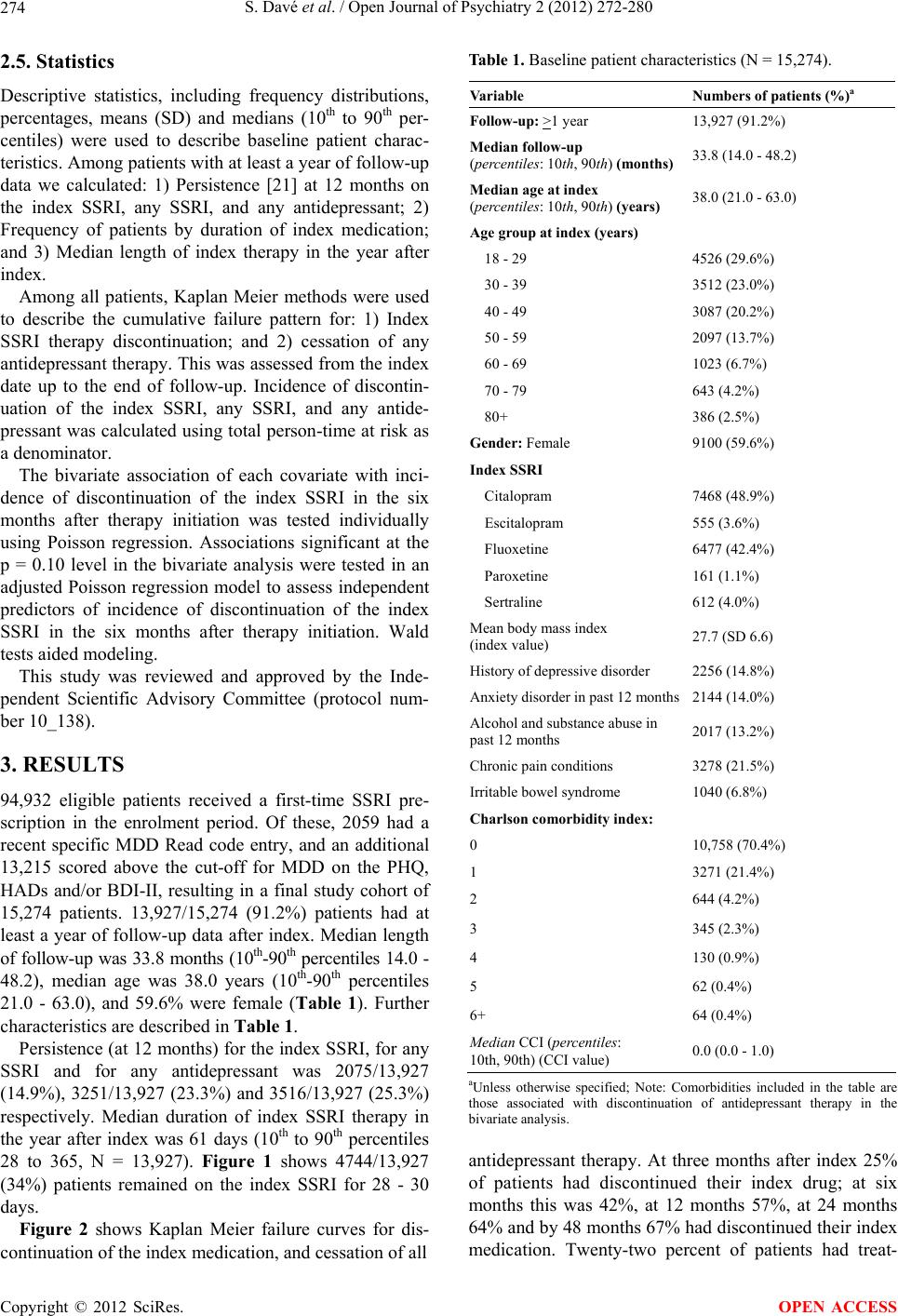

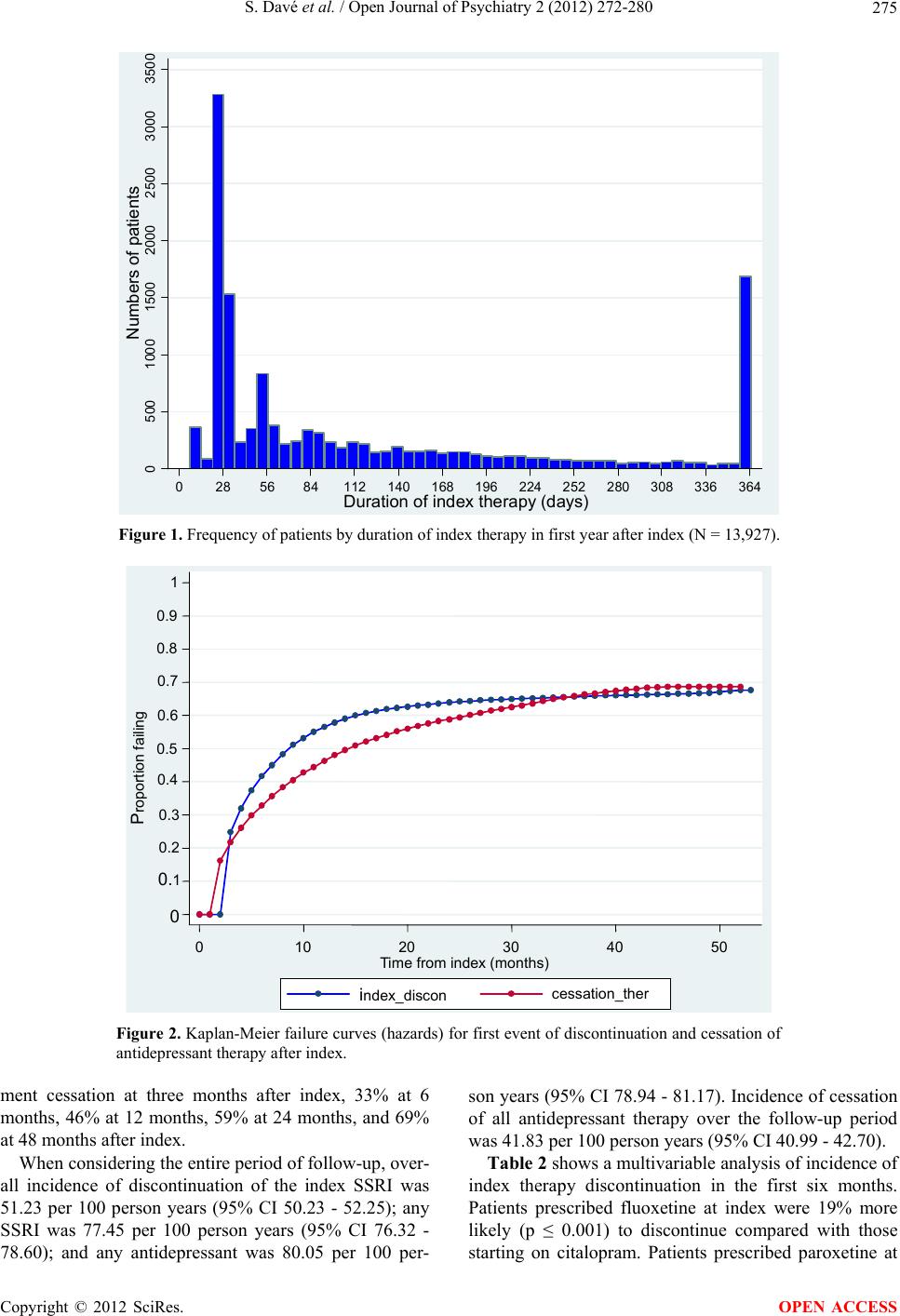

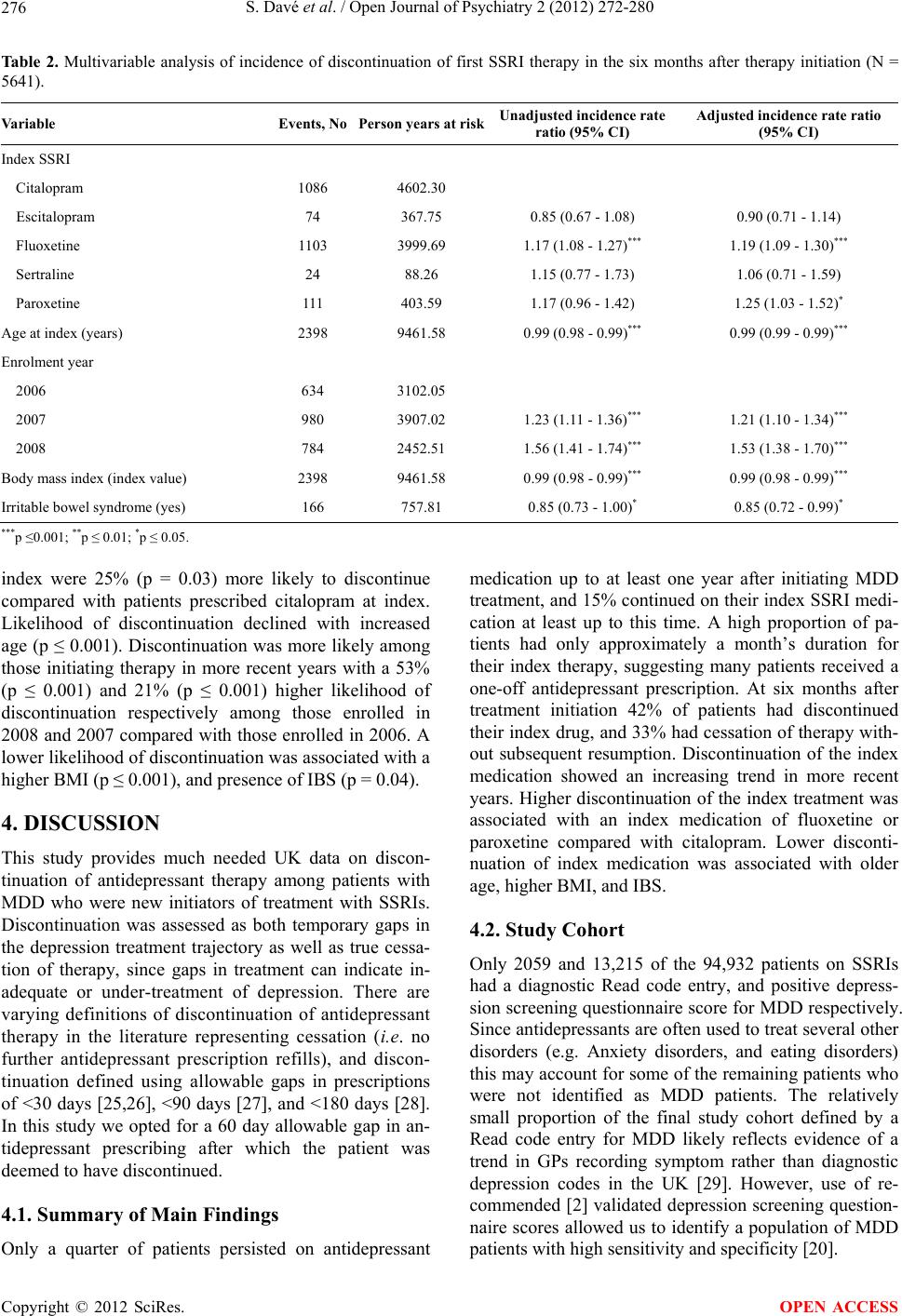

|