Journal of Software Engineering and Applications, 2012, 5, 743-751 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jsea.2012.510087 Published Online October 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jsea) 743 User Experience Design and Agile Development: From Theory to Practice Tiago Silva da Silva1*, Milene Selbach Silveira2, Frank Maurer3, Theodore Hellmann3 1ICMC, Universidade de São Paulo, Campus de São Carlos, São Carlos, Brazil; 2FACIN, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil; 3CPSC, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada. Email: *tiago.silva@icmc.usp.br Received June 30th, 2012; revised July 31st, 2012; accepted August 11th, 2012 ABSTRACT We used existing studies on the integration of user experience design and agile methods as a basis to develop a frame- work for integrating UX and Agile. We performed a field study in an ongoing project of a medium-sized company in order to check if the prop osed framework fits in the real world, and how some aspects of the integration of UX and Ag- ile work in a real project. This led us to some conclu sions situating contribu tions from pr actice to theo ry and back again. The framework is briefly described in this paper and consists of a set of practices, artifacts, and techniques derived from the literature. By combinin g theory and practice we were able to conf irm some thoughts and id entify some gaps—both in the company process and in our proposed framework—and drive our attention to new issues that need to be ad- dressed. We believe that the most important issues in our case study are: UX designers cannot collaborate closely with developers becau se UX d esign ers are work ing on multiple p rojects an d that UX designers canno t work up front because they are too busy with too many projects at the same time. Keywords: Agile; User Experience; Integration; Framework; Field Study 1. Introduction Agile development has become a mainstream regarding software development processes. At the same time, an increasing understanding of the importance of good UX came along and the need to integrate these two areas emerged. Agile methods as well as User Experience (UX) design methods aim to build quality software, but desp ite this common concern, each approaches development f rom a different perspective [1]. According to the authors, while Agile methods mainly describe activities addr essing code creation or project management, UX design methods des- cribe activities for designing the product’s interactions and/or interface with a user. These two methodologies traditionally use different ap- proaches for resource allocation in a project [2]. Agile methods strive to deliver small sets of software features to customers as quickly as possible in short iterations while, on the other hand, User-Centered Design (UCD) advocated spending considerable effort on research and analysis before development begins. Up until a few years ago, little attention had been giv- en to the integration of UX and Agile. This could be due to historical issues su ch as no t unders tanding th e n eed for a good user experience and by not knowing Agile meth- ods in detail, or just by thinking that they could no t work together due to their differences in focus. However, now- adays there are a reasonable number of studies address- ing this integration, as can be seen in [3]. Thus, our aim in this paper is to create a better under- standing of Agile and UX design in theory and practice. In this paper, we present similarities and differences be- tween the findings from a previous theoretical study [3] and a framework proposed for integrating UX and Agile development that emerged from that theoretical study. We also describe in detail the work involved in integrat- ing UX design and Agile development in a in a world leading technology company that develops and manu- factures collaboration products. 1As the result, we will be able to see the theory in practice and the contributions from the practice to the theory. This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents some related work regarding this topic; Section 3 briefly presents the proposed framework; Section 4 describes the case study and its findings; Section 5 presents a discus- sion and Section 6 presents some conclusions and up- coming steps for this research. 1This is the description provided by the company’s research facilitator. The name of the company and the projects were omitted due to confi- dentiality constraints. *Corresponding autho . Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JSEA  User Experience Design and Agile Development: From Theory to Practice 744 2. UX and Agile Integration In the following section, we will summarize the existing literature regarding UX and Agile integration. Most of the work is based on case studies and leads to similar conclu- sions—which w e use as the ba sis of the pr oposed fram ework. Chamberlain et al. [4] present a framework for use by teams trying to integrate UCD practices with Agile de- velopment. They present so me similarities between UCD and Agile based on the literature and an observational study too. Based on their results, they suggest five prin- ciples for integrating User-Centered Design and agile de- velopment, such as: 1) The user should be involved in the development process; 2) Designers and developers must be willing to communicate and work together extremely closely; 3) Designers must be willing to feed the devel- oper with prototypes and user feedback; 4) UCD practi- tioners must be given ample time in order to discover the basic users’ needs before any code; 5) Agile/UCD inte- gration must exist within a cohesive project management framework. Ferreira et al. [5] state that the integration of UI design and agile development is not well understood and report a qualitative grounded theory study of Agile projects in- volving significant UI design. Some results of their study were that using iterative development—an Agile practice— facilitates usability testing, allows software developers to incorporate results of those tests into subsequent itera- tions, and can significantly improve the quality of the re- lationship between UI designers and software developers. Mcinerney and Maurer [6] performed a set of intervi- ews with UCD designers involved with Agile projects and concluded that all of the UCD practitioners’ reports were positive. These authors also report that the current literature indicates that improving our understanding of how to coordinate and integrate the work of UX design- ers and Agile developers helps bridge the gap between the Software Engineering and HCI. Still, according to Ferreira et al. [1], the problem of having both Agile developers and UX designers contrib- uting their skills to a software development project has typically been characterized as a problem of merging one method with another. For example, Patton [7] explains how Usage-Centered Design can be combined with ex- treme Programming; Obendorf and Finck [8] explain how Scenario-Based Usability Engineering was combined w ith extreme Programming; and Miller [9] explains how User - Centered Design techniques were integrated with an Ag- ile process that was a combination of Adaptive Software Development and extreme Programming. Sy [10] describes the adaptations at her company, whic h includes adjusting timing and granularity of usability investigations and the way that usability findings were reported. She also concluded that the new Agile UCD methods produce better-designed products than versions designed using a waterfall approach. Also, Singh [11] pro- poses a process, U-Scrum, which adapts Scrum to pro- mote usability. Beyer [12] presents a proc ess proposal in which he describes the need for UX designers to under- stand Agile principles and presents best practices for this integration. Another indication of the importance of the integration of these two techniques is the number of studies addressing UX and Agile found in the literature over the last ten years. More details and deeper analysis on the existing literature can be found at [3]. 3. Proposed Framework Jokela and Abrahamsson [13] and Sohaib and Khan [14] commented that Interaction Design and Agile methods fit well, and that the challenge is not to make Agile less agile but in adaptin g the methods of UCD so they can be “light” and efficient at the same time. Hussain et al. [15] pointed out some beneficial simi- larities between UCD and Agile, e.g., having the client on-site, continued testing and iterative development. Mo- reover, as noted in [16], the two methods have much to offer when they share iterations because the iterations used in Agile facilitate usability testing and allow deve- lopers to incorporate results of these tests in subsequent iterations. However, [17] commented that improving the usability of a product does not come without costs or risks even when the methods are rationaliz ed. In order to integrate Agile and UX Design and at the same time minimize these costs and risks, the proposed framework suggests the use of usab ility artifacts and pra- ctices in a condensed form. This is indicated by Agile principles and we expect that it will improv e the u sab ility of products while at the same time minimally impacting the activities of normal Agile development. The structure of our framework is similar to the proc- esses described by [5,10,18]. The difference is that we propose a combination of the most common practices, artifacts and processes identified in the systematic review [3] previously cited, i.e. our framework is more concrete in its recommendation s th an previous work. The flexibility and adaptability offered by Agile me- thods are widely discussed, so the intent of our frame- work is not to stiffen these methods, but, as suggested by [14], to adapt usability practices to an Agile setting in order to improve the usability of products developed us- ing these methods. The framework we propose is presented at a high level in Figure 1 and it is organized according to the activities of the Interaction Design lifecycle mode l [19], as follows: User Research, (Re)Design, and Evaluation. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JSEA  User Experience Design and Agile Development: From Theory to Practice Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JSEA 745 Figure 1. High-level representation of the proposed framework. 3.1. User Research methods, the Interaction Designers should focus on a small number of tasks at a time instead of on trying to design the entire product at the beginning of the project. One of the major concepts in Agile is LDUF (Little De- sign up Front2); that is, it is recommended to perform only a little (but not all) d esign work before implementa- tion begins. We propose the adoption of Sprint 0: an it- eration that takes place before the start of implementation or even before the official kick off of the project. It is important to include Interaction Designers in Sprint 0 due to their skills in gathering and analyzing data from UX because, according to [20], developers tend to listen to what customers want instead of looking at what they do. Contextual investigatio n, task analysis, user interv iews, prototyping, and prototype validation could be performed during each iteration. To facilitate the process, the Inter- action Design team should work on user research one sprint ahead of the development team. This allows the results of the user research to be fed into the iteration plan in form of user stories on time for the development team to start implementing the design. Sprint 0 encompasses activities such as context re- search (Contextual Inquiry [21]), Observations, Task Analysis, and Interviews. Such activities shou ld generate paper prototypes and/or Design Cards3 that will help to define the User Stories. To facilitate LDUF, activities related to requirements gathering and analysis must be performed throughout the development process in order to avoid concentrating these tasks towards the beginning of the project. The result of this should be just-in-time design. In other words, as with the developers using Agile Once User Stories have been defined, the Interaction Design team should design the user interface and validate these stories, adding usability aspects as acceptance cri- teria for each User Story. The Interaction Design team should deliver the Story Cards to the development team. These activities sho uld b e d one b efo re the plan ning g ame, so they can be discussed during that activity. 3Upcoming designs are represented on the planning boards as design cards, which are blue to differentiate them from feature cards, and have no implementation time estimates [10]. This is a way of communicating to plan. 2In this specific context, we mean User Research by Design.  User Experience Design and Agile Development: From Theory to Practice 746 3.2. (Re)Design Prototypes, Feature Cards4, Design Cards, and Issue C ar d s5 could be used to report both designs and evaluation re- sults to guide the redesign of the interface. It is important to mention that we do not want to suggest specific types of prototypes because each team or product has its par- ticularities regarding prototypes and diagrams. A light way of reporting such issues is very important in an Agile context. Using simple artifacts helps in com- munication between all stakeholders and adds value to the development process. We recommend the use of a User Experience Board for maintaining a shared vision where possible. We can use prototypes and/or Design Cards for com- munication between UX Designers and developers. When delivering designs to the development team, it may also help to make use of Feature Cards and prototypes—both low and high fidelity—this will depend on the teams’ cha- racteristics. Problems and/or modifications can be reported in daily meetings using Oral Storytelling6 and Issue Cards. This can help the development team incorporate design im- provements into their work. 3.3. Evaluation We suggest evaluating the entire implementation one sprint after development. This is because evaluating the implementation of the current sprint would require the development team to deliver before the end of the sprint. This would reduce staff time for development and leave them idle while the Interaction Design team conducts evaluations. Usability evaluations should be performed regularly. Performing user testing during the sprints is hard given the time required to prepare, schedule, conduct, and ana- lyze this type of test. So, while it may not be possible to do these evaluations for each sprint, we recommend that they be done, at the least, before the delivery of the re- lease. It is worthwhile to mention that these tests should be conducted with real users. An alternative is the in- clusion of activities related to data capture and usability when performing acceptanc e tests. The UX Team should work closely with the develop- ment team to support them in terms of designing and conducting insp ection evaluations on the implementation of the current sprint and provide feedback. This needs to be done without blocking the development team. How- ever, the UX Team must analyze the problems they iden- tify and determine if there is time to fix these issues in the same sprint or if they should be documented and car- ried over into the next sprint. 4. Case Description We performed a field study in an ongoing project of a medium-sized company in order to evaluate if the pro- posed framework fits in a real project and how some as- pects of the integration of UX and Agile work in the real world. We begin by describing our field study in terms of the people, the project, the research site, how we collected the data and performed the data analysis. We then relate our findings to the aspects highlighted by our proposed framework. A study of UX designers and their in teractions with an Agile team working on the same project was carried out over three iterations—45 days. In the following section, we describe the team, their project and their organization setting then we discuss how we collected and analyzed the data. 4.1. The People Our study involved seven members of an Agile team and one UX designer. The developers were part of the De- velopment Team and the designer was part of the UX Team. The developers had been developi ng soft ware using Scrum for approximately two years. Although they are called developers, individuals in the team have their own role according to their background and skills. The roles were Project Manager/Scrum Master, Product Owner, De- veloper, Technical Leader and Tester as can be seen at Table 1. Information architects, graphic designers, and interac- tion designers compose the UX team. Each project has one UX designer, but a UX designer usually works on more than one development team at a time. The same goes for Project Managers. Interestingly, Project Manag- ers are known as Scrum Masters in this organization. Table 1. The roles and the number of individuals for the Development Team. Role Individuals Project manager/Scrum master 1 Product owner 1 Technical leader 1 Developer 2 Tester 2 4Describes the acceptance criteria that determine when that feature is complete, and also includ es a time estimate for completion [10]. 5Physical cards used to communicate information from observations and interviews with users. This is a way of communicating to persuade [10]. 6It is a technique that can take rational ideas and bring them more fully into the world by giving them a human context to affect people. So one of the best things about stories is that th ey inspire other stories [29]. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JSEA  User Experience Design and Agile Development: From Theory to Practice 747 It is worthwhile to mention that despite we observed one team and one UX Designer, as presented in Table 1, we interviewed three UX Designers of the company. 4.2. The Project Due to confidentiality constraints, we cannot provide much information about the projects. As already men- tioned, we observed two projects that we will refer to as Project X and Project Y: Project X: development of new features for an exist- ing product of the company; Project Y: development of an existing product of the company for a mobile/tablet device. The UX member’s role in Project X was to help soft- ware engineers envision new features for the product. In Project Y, the UX members’ roles were to prototype and design the User Interface and the User Interaction flow for the product. 4.3. The Research Site The developers and designers were part of a technology company that develops and manufactures collaboration products, as already mentioned. The team of developers was one of several Scrum teams in the company working on software development. The developers and designers were seated in an open- plan office space located in the same b uildin g. Howev er, they were not seated together. They were spread in the building, although the UX team members were seated close to each other. The researcher was seated with a UX member that was observing these projects. 4.4. Data Collection We used two first-degree data collection techniques: ob- servations and interviews. Regarding observations, due to the characteristics of invoking the least amount of interference in the work environment and the least expensive method to imple- ment and, most importantly, because the company did not permit video or audio recording of the meetings, we choose to manually record our observations of the meet- ings described below. We shadowed a UX person during his activities for three iterations—45 days—and observed meetings in which he was involved, such as meetings of the UX Team and meetings for the two different projects: Project X: two requirements7 meetings, one retrosp- ective meeting; Project Y: one demo meeting, three planning meet- ings, three retrospective meetings and two user testing sessions; UX group meetings: four meetings. For our interviews, we interviewed three members of the UX group that work in different projects and one project manager. The Project Manager was interviewed in order to bet- ter understand which Agile methods the company uses and how this integration of UX and Agile is or is not successful from his point of view. The UX people were interviewed in order to understand UX work on the dif- ferent projects of the company. 4.5. Data Analysis We performed Open and Focused Coding [22] to analyze the data. Initial memos were extracted by the researcher from the field notes produced during the observations and from the interviews performed with members of the teams. After generating memos, Open Coding was performed in order to generate new insights and themes. Focused Coding was also performed and this coding consisted of linking the memos gen erated to the key asp ects identified in the systematic review [3]. Also, some new aspects emerged from the analysis of the observations and inter- views. Later, some integrative memos were also written in order to relate the field notes, the key aspects, and these new codes. We classified our findings according to the key aspects used for Focu sed Coding. W e also presented our findings to the company in order to validate these insig hts and the teams’ members confir med them. In the following sectio n, we relate our find ings in te rms of the activities we observed and place these activities in the proposed framework context, establishing a relation- ship between theory and practice. 4.6. Findings Here we take a deeper look at the work of the UX de- signers and Agile developers and how they coordinated their work on a day-to-day basis. The work of interest during our observations and in terviews was all th e activi- ties, tools, and artifacts used from requirements elicita- tion to the product evaluation. In this section, we link between the memos extracted from field notes and inter- views and the codes—key aspects—that emerged in the Systematic Review. Little Design Up Front —There is no design up fr ont. —There is no collaboration between the UX team and the Marketing Team. We noticed that the company does not perform any design up front. We also noticed that there is no collabo- ration between the UX Team and the Marketing Team, 7The company used to perform requirements meetings previously of the roject’s kickoff in order to g ain a project’s big picture. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JSEA  User Experience Design and Agile Development: From Theory to Practice 748 based on comments like: “Some User Research is per- formed by the Marketing Team. In general, the Market- ing Team knows what they say they need, not what they really need. It’s a not a target effort to gather what the user need… It’s a sell visit.”—UX18. Additionally, UX3 remarked that “We absolutely are not close to the Mar- keting Team.” The accomplishment of LDUF by the UX Team is compromised because the Marketing Team does not have the background to perform real user studies. Consequently, the results from their studies are not that good for design. Only some information comes from the Marketing to the UX team. Since there is almost no User Research before the project is launched, the UX Team has to try to think from the user’s point of view. But we observed that in some projects there is an effort from the UX Team to participate of the Requirements Meetings to better understand the needs of the Customer; however, it is worthwhile to remember that the Customer is not al- ways the User. Thus, we notice that the UX Team under- stands the concept of LDUF (“We don’t need to design everything up front.”—UX3) although they do not make use of it. Prototyping —UX Team makes reall y good use of prototypes. —The use of a certain type of prototype depends on the UX Designer’s background. We noticed that the UX Team makes really good use of prototypes. Depending on the situation they use, e.g. “Paper prototypes, high fidelity prototypes, the produ ct… sometimes prototyping tools, sometimes high-fi prototyp- es, sometimes low-fi.”—UX1. Some members of the UX Team cannot design/draw interfaces and they complain about that, as follows: “We UX people all can do some stuff, for example, User Testing and finding usability iss- ues… but not everyone can be designers, for example” —UX1. “It’s tricky for UX people to code.”—UX2. The term “code” here is not about being a developer, but is about creating a UI using HTML, for instance. There is an issue because some of team members are UX Design- ers and not Graphic Designers. 9We also noticed that since the members of the UX Team have different back- grounds, some of them can code some functional—high- fidelity—prototypes and some of them cannot. User Testing —User Tests with real users are rarely performed even when the project is in its final stages. —User Tests used to be performed with internal us- ers. This led to problems after the product release. When they perform some User Testing with real users, the pro- bability of a product being released with fewer problems increases. User Testing used to be performed with inter- nal users based on the justification that there are always new and old employees with different profiles and back- grounds: “[For] internal studies… [we use] new people and old people from inside the Company...”—UX2. User Stories —There are not User Stories specific to UX. —There is no standard on reporting UX issues. Sometimes when UX User Stories are written, these stories are then brok en into smaller stories with technical development criteria. Hence, in general, User Stories do not have usability issues as acceptance criteria as sug- gested by the literature, e.g. [11]. We also notice that sometimes User Stories are used to report usability issues identified during usability tests: “Sometimes we add new user stories based on the resu lts of the User Testing. But it depends on the problem. We can also put them as a bug.”—UX2. The different ways that teams and UX mem- bers use User Stories lead to another observation: a lack of standard on how to report UX issues . Usability Inspection —UX Team performs peer reviews on the UI de- sign. —Peer reviews work well for them. We observed that the UX Team performs some insp- ection evaluations, e.g. a member of the UX Team de- signs a prototype and then another member perform so me evaluations (“We perform some experts evaluations, peer review.”—UX1). Even though they do not follow a spe- cific method of inspection evalu ation, e.g. Heuristic Eva- luation [23], it seems to work very well for them. This peer review is a practice like pair programming, and it seems to provide the necessary feedback to the teams. One Sprint Ahead —UX Team does not work one sprint ahead. —UX Designers work on more than one project at the same time. It is clear that the UX Team does not work one sprint ahead from the development team as suggested by the literature. Although the UX Team knows the benefits of designing one sprint ahead, it is not possible for now because they did not find the time yet (“We should work at least one sprint ahead the development team.”—UX3). One of the problems is that the UX Team members do not have time to design one sprint ahead of the develop- ment team, probably because they are busy with other projects. It is consistent with the fact that there is not 9Interaction Designer defines the beha vior of artifacts, environmen ts, an d systems or products whereas Graphic Designer is a professional within the graphic design and graphic arts industry who assembles together images, typography or motion graphics to create a piece of design. 8UX# means UX Team member interviewed and PM means Project Manager. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JSEA  User Experience Design and Agile Development: From Theory to Practice 749 only One Team as Agile principles suggest. We observe that the UX is almost outsourced. Even if there is a UX Team within the company, UX members are not full mem- bers of the development team, they are always working on many projects at the same time: “We used to work on multiple projects, but it’s really easier to work on only one product. It is so much easier to get involved, you know what’s going on. Your attention is right di- rected.”—UX2. UX people cannot have the same level of inclusion in all the projects they are involved con- comitantly (“I’m working on 7 to 10 projects at the same time. With different levels of inclusion.”—UX3). We suggest that UX members should be dedicated to one team or a very small number of teams in order to avoid issues. This might be related to the issues with LDUF discussed above in that if no research or design is carried out up front, the UX Team member does not know what do in the current sprint based on the upcoming sprints. Close Collaboration —There is no close connection/collaboration between UX and Marketing. —UX Designers cannot be deeper involved in a project because they are working on too many pro- jects. We observed that there is no collaboration between the UX and the Marketing Team, but there is a good com- munication between the UX Team and the Development Team. However, as already mentioned, sometimes UX members block the Development Team because they are working on other projects. Sometimes even the daily meetings block the UX member, because since they are working in many projects, they have a lot of meetings to attend. For example: “UX people should be Pigs10.”—PM. UX people should be more committed to the projects. But it is not that they do not want to, they just cannot because they have too many commitments. (“Sometimes, the member of the team doesn’t know who to answer to, to the Project Manager or to the Function Man- ager.”—PM.) This last quote seems to be a problem due to a confusion of roles inside the company, which com- pounds an already difficult situation, described below. We could observe that the company uses an adapted Scrum. In Scrum by the book, there are: Product Owner, Scrum Master and Team. In the company observed there are: Project Manager, Product Manager, Function Man- ager and Team. Each team member has a Function Man- ager based on her skills as well as a Project Manager based on the pr oject(s) she is assigned to. A project team consists of team members with different skills reporting to their Function Manager. The Product Manager acts more like the Product Owner. The Project Manager acts more like the Scrum Master in terms of being a facilitator, because he is not a developer and he also manages more than one project. The Function Manager is in charge of the teams’ members’ time. For example, the UX Team has a Function Manager who defines which project has to be prioritized. That is why we said that UX is almost outsourced: the UX member is not always available to the rest of the team. It is extremely important to note that all of the observations and findings are related to new projects or new products. We notice that for products that are being developed for a long time, the UX members that work for a long time in the same project already have some standards that they follow. But these stan- dards are too specific to be used in another product or by another member of the UX Team. Big Picture —UX Designers have no problem to maintain the project Big Picture. We did not observe problems about the maintenance of the Big Picture of the company’s projects. However, we heard some complaints from the UX Team members about how to communicate their ideas or design deci- sions to higher levels of management in the company. They said that sometimes Directors, for instance, do not understand their concepts and prototypes are not enough. We performed a thematic analysis of the data from the observations and interviews in order to identify patterns or themes. Then we relate the findings to the th ree activi- ties that compose interaction d esign [19]: User Research, Design, and Evaluation. 5. Discussion Our thematic analysis led us to some conclusions situat- ing contributions from practice to theory and from theory to practice. They are briefly presented as follows. 5.1. User Research Regarding User Research, we notice that the UX Team does not perform any—at least in the projects observed. The Marketing Team performs some studies, e.g., some observations in context, however this is not always the case. Based on the literature, we recommend the use of techniques such as Contextual Inquiry in order to benefit from User Research because it is important that there is some design up front, but not all. 5.2. (Re)Design While the UX team made good use of prototypes, we notice that these artifacts were not used for the commu- nication between the UX Team and the Development team. Based on the lit erature, low-fi delit y prototy pes could 10This is a fable told by Scrum practitioners about a pig and a chicken who considered starting a restaurant. “We could serve ham and eggs,” said the chicken. “I don’t think that would work,” said the pig. “I’d be committed, but you’d only be involved.” Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JSEA  User Experience Design and Agile Development: From Theory to Practice 750 be used to facilitate communication between UX and development teams and presentations of these prototypes and concepts could be used to facilitate the communica- tion between UX teams and Management/Stakeholders in the early stages. The use of these practices would not require significant chang es to the compa ny’s proc ess and could result in stron g benefit s . 5.3. Evaluation The use of peer review evaluations and validations by members of the Development Team and other UX Team members was perceived by team members to be a quick way to get feedback about their work. However, we ma- intain some reservations about the effectiveness of this practice—especially given that our investigation uncov- ered that issues were likely to be found earlier in an ap- plication if evaluations using real users were performed. 6. Conclusions The theory on which we based this work—the results from a Systematic Literature Review—led us to a frame- work for integrating UX and Agile development. This framework briefly described in this paper consists of a set of practices, artifacts, and techniques derived from the literature. The practice on which we based this work—a field study carried out in a company that tries to combine UX and Agile—showed us some aspects that work and some that do not work in this specific real-world environment. By combining theory and practice we were able to confirm some thoughts and identify some gaps—both in the compan y process and in our proposed fr amewor k —a n d drive our attention to new issues that need to be ad- dressed. We believe that the most important issues in our case study are: UX Designers cannot collaborate closely with Developers because UX Designers are working on mul- tiple projects and that UX Designers cannot work up front because they are too busy with too many projects at the same time. According to our observations, this is translated to a cycle. Once a UX Designer is working on more than one project at the same time, he is busy all the time and he cannot perform research or a little design up front. With- out any research or design up front, he does not know what to design afterwards. Consequently, the UX De- signer is always working at the same iteration of the De- velopment Team, or even worse, he is working one sprint behind them. The issue is that the UX people do not have the information needed to make informed decisions about UX design at a point when they can easily impact the development effort. This study carried out inside this company is part of a larger Action Research initiative that we are performing within this company. So, we are constantly an alyzing the data and refining the framework. As we could notice in the literature, Mcinerney and Maurer [24] reported results of interviews with UX De- signers, just mentioning the necessity of adding UX De- sign into Agile development without a specific proposal. Chamberlain et al. [25] presented general principles for the integration of UX and Agile that should guide UX Designers on how to take advantag e of the Agile process structure. Hussain et al. [26] present some of the artifacts most used by UX Designers working on Agile teams, whereas Adikari et al. [27] introduce the concept of Lit- tle Design Up Front. Sy [28] reports experiences on inte- grating UX Design and Agile development, suggesting adaptations of the UCD (User-Centered Design) in terms of tasks granularity, reporting and timing. As can be noticed, a lot of studies have been under- taken, however each of them addresses different aspects of the integration. Moreover, in general, the studies pro- vide experience reports or propose an approach without any kind of verification or validation. The framework proposed aims at addressing different aspects of this in- tegration, providing alternatives to the UX Designer in- serted in the Agile context. One of our next steps is to perform field studies in other companies with ongoing projects, instead of new ones. We are aiming at refining our framework and mak- ing it suitable to different stages of projects and to dif- ferent companies. REFERENCES [1] J. Ferreira, H. Sharp and H. Robinson, “User Experience Design and Agile Development: Managing Cooperation through Articulation Work,” Software Practice Experi- ment, Vol. 41, No. 9, 2011, pp. 963-974. [2] D. Fox, J. Sillito and F. Maurer, “Agile Methods and User-Centered Design: How These Two Methodologies Are Being Successfully Integrated in Industry,” Proceed- ings of the Agile, Washington, 4-8 August 2008, pp. 63- 72. [3] T. S. da Silva, A. Martin, F. Maurer and M. Silveira, “User-Centered Design and Agile Methods: A Systematic Review,” Agile Conference, Salt Lake City, 7-13 August 2011, pp. 77-86. [4] S. Chamberlain, H. Sharp and N. Maiden, “Towards a Framework for Integrating Agile Development and User-Centred Design,” Proceedings of Extreme Pro- gramming and Agile Processes in Software Engineering: 7th International Conference, Oulu, 17-22 June 2006, pp. 143-153. [5] J. Ferreira, J. Noble and R. Biddle, “Agile Development Iterations and UI Design,” Proceedings of the AGILE, Washington, August 2007, pp. 50-58. [6] P. Mcinerney and F. Maurer, “UCD in Agile Projects: Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JSEA  User Experience Design and Agile Development: From Theory to Practice Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JSEA 751 Dream Team or Odd Couple?” Interactions, Vol. 12, No. 6, 2005, pp. 19-23. doi:10.1145/1096554.1096556 [7] J. Patton, “Designing Requirements: Incorporating Us- age-Centered Design into an Agile SW Development Process,” Extreme Programming and Agile Methods— XP/Agile Universe, Vol. 2418, No. 2002, 2002, pp. 95- 102. [8] H. Obendorf and M. Finck, “Scenario-Based Usability Engineering Techniques in Agile Development Proc- esses,” Proceedings CHI EA’08 CHI’08, New York, April 2008, pp. 2159-2166. [9] L. Miller, “Case Study of Customer Input for a Successful Product,” Proceedings of the Agile Development Confer- ence, Washington, July 2005, pp. 225-234. [10] D. Sy, “Adapting Usability Investigations for Agile User- Centered Design,” Journal of Usability Studies, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2007, pp. 112-132. [11] M. Singh, “U-SCRUM: An Agile Methodology for Pro- moting Usability,” Agile, Toronto, 4-8 August 2008, pp. 555-560. [12] H. Beyer, “User-Centered Agile Methods,” Morgan & Claypool Publishers, Pennsylvania, 2010. [13] T. Jokela and P. Abrahamsson, “Usability Assessment of an Extreme Programming Project: Close Co-Operation with the Customer Does Not Equal to Good Usability,” Lec- ture Notes in Computer Science—Product Focused Soft- ware Process Improvement, Vol. 3009, No. 2004, 2004, pp. 393-407. [14] O. Sohaib and K. Khan, “Integrating Usability Engineer- ing and Agile Software Development: A Literature Re- view,” International Conference on Computer Design and Applications (ICCDA), Qinhuangdao, 25-27 June 2010, pp. V2-V32. [15] Z. Hussain, et al., “Agile User-Centered Design Applied to a Mobile Multimedia Streaming Application,” HCI and Usability for Education and Work, Vol. 5298, No. 2008, 2008, pp. 313-330. [16] H. Williams and A. Ferguson, “The UCD Perspective: Be- fore and after Agile,” Agile 2007, Washington DC, 2007, pp. 285-290. [17] L. L. Constantine and L. A. D. Lockwood, “Usa ge-Centered Engineering for Web Applications,” Journal IEEE Soft- ware Archive, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2002, pp. 42-50. doi:10.1109/52.991331 [18] D. Fox, J. Sillito and F. Maurer, “Agile Methods and User-Centered Design: How These Two Methodologies Are Being Successfully Integrated in Industry,” Proceed- ings of the Agile, Washington, 4-8 August 2008, pp. 63- 72. doi:10.1109/Agile.2008.78 [19] H. Sharp, Y. Roger and J. Preece, “Interaction Design: Beyond Human-Computer Interaction,” 2nd Edition, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, 2007. [20] C. S. A. Peixoto and A. E. A. da Silva, “A Conceptual Knowledge Base Representation for Agile Design of Human-Computer Interface,” Proceedings of the 3rd In- ternational Conference on Intelligent Information Tech- nology Application, Nanchang, November 2009, pp. 156- 160. [21] K. Holtzblatt and H. R. Beyer, “Contextual Design,” In: M. Soegaard and R. F. Dam, Eds., Encyclopedia of Hu- man-Computer Interaction, The Interaction-Design.org Foundation, Aarhus, 2004, pp. 50-59. [22] R. M. Emerson, R. I. Fretz and L. L. Shaw, “Writing Ethnographic Field Notes,” 2nd Edition, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2011. [23] J. Nielsen and R. L. Mack, “Usability Inspection Meth- ods,” John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1994. [24] P. Mcinerney and F. Maurer, “UCD in Agile Projects: Dream Team or Odd Couple?” Interactions, Vol. 12, No. 6, 2005, pp. 19-23. doi:10.1145/1096554.1096556 [25] S. Chamberlain, H. Sharp and N. Maiden, “Towards a Framework for Integrating Agile Development and User- Centred Design,” Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Extreme Programming and Agile Proc- esses in Software Engineering, London, June 2006, pp. 143-153. [26] Z. Hussain, W. Slany and A. Holzinger, “Current State of Agile User-Centered Design: A Survey,” Proceedings of the 5th Symposium of the Workgroup Human-Computer Interaction and Usability Engineering of the Austrian Computer Society on HCI and Usability for E-Inclusion, Berlin, November 2009, pp. 416-427. [27] S. Adikari, C. McDonald and J. Campbell, “Little Design Up-Front: A Design Science Approach to Integrating Usability into Agile Requirements Engineering,” Hu- man-Computer Interaction—HCII 2009, Berlin, July 2009, pp. 549-558. [28] D. Sy, “Adapting Usability Investigations for Agile User- Centered Design,” Journal of Usability Studies, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2007, pp. 112-132. [29] W. Quesenbery and K. Brooks, “Storytelling for User Experience: Crafting Stories for Better Design,” Rosenfeld Media, Louis Rosenfeld, 2011.

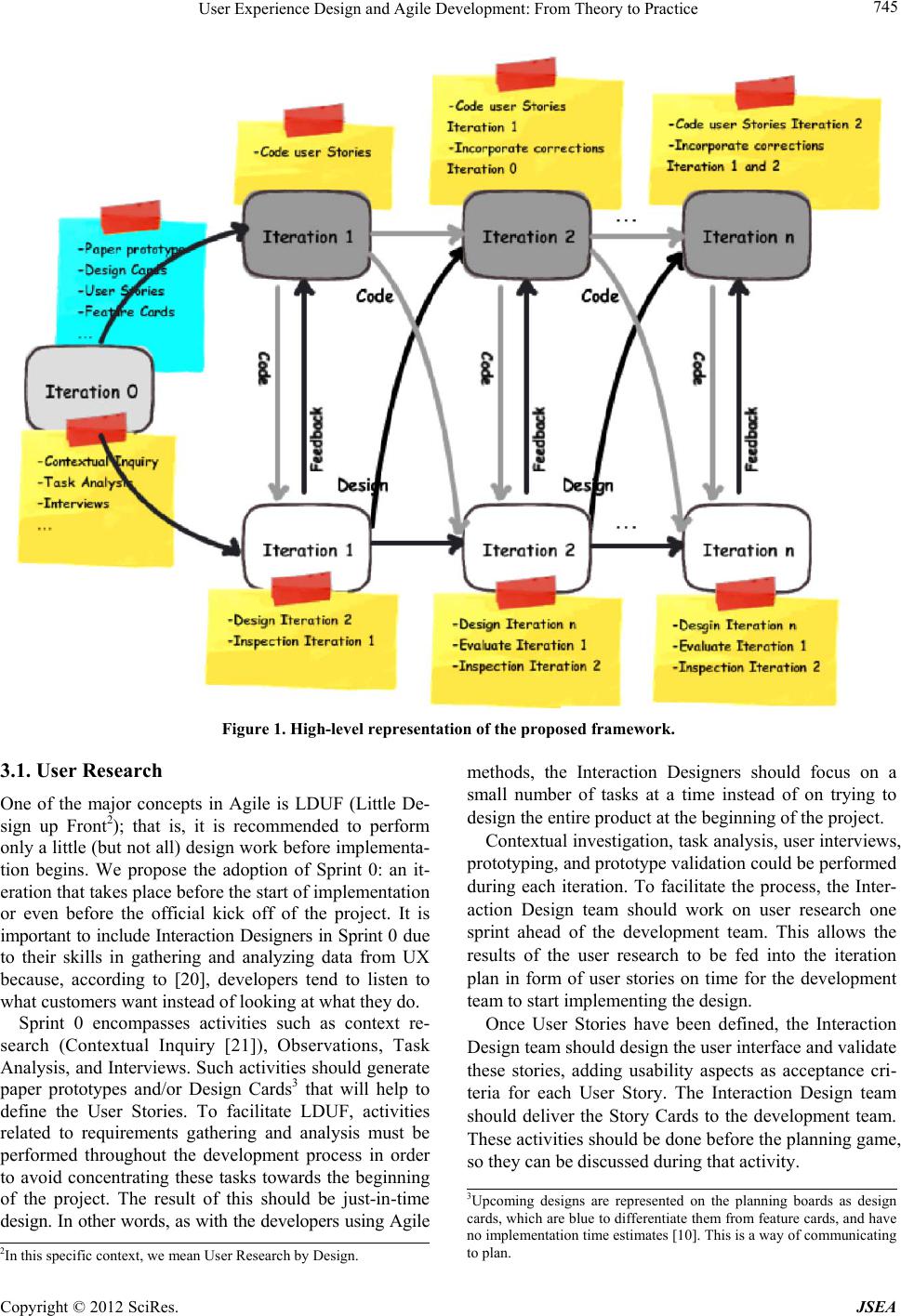

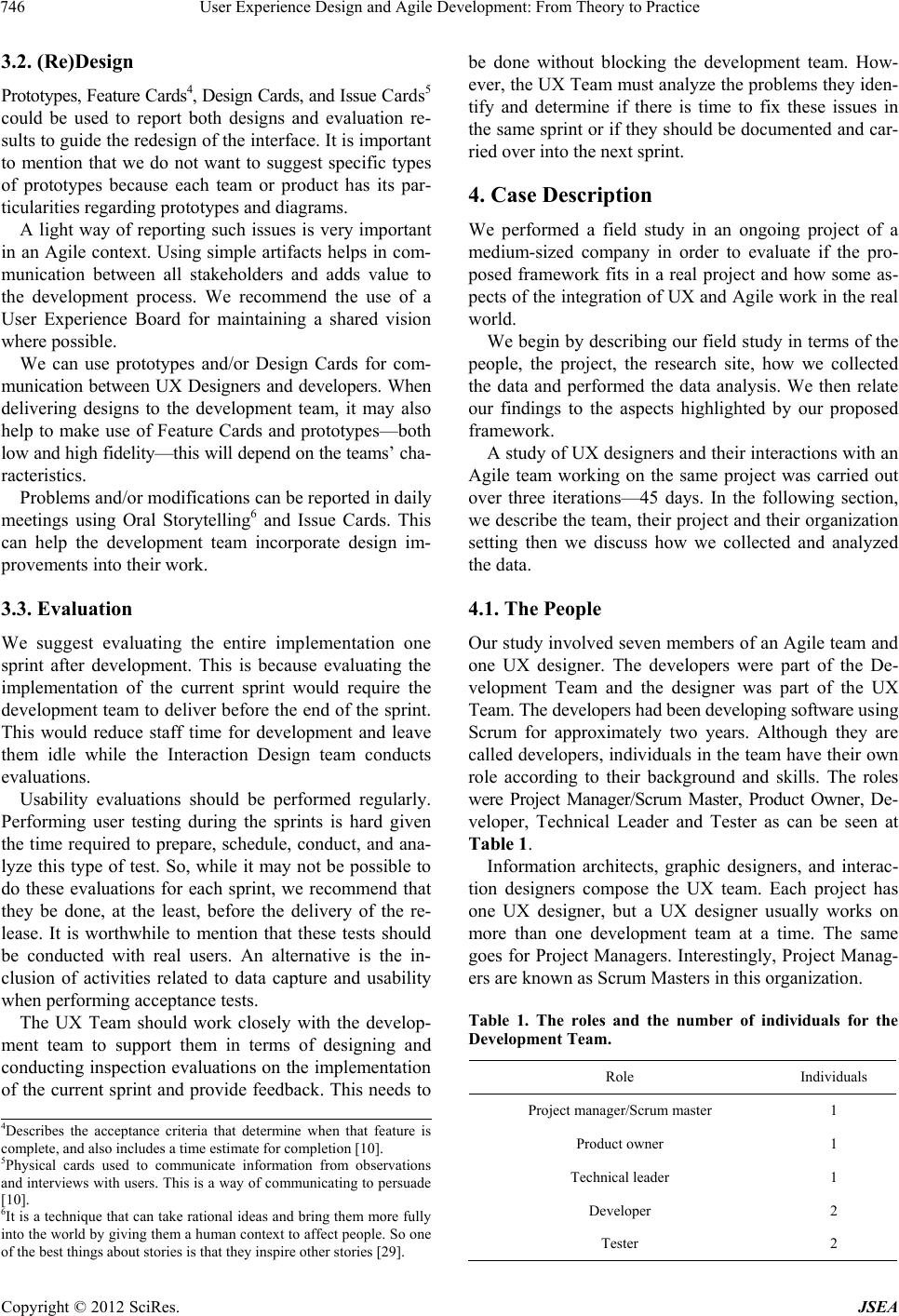

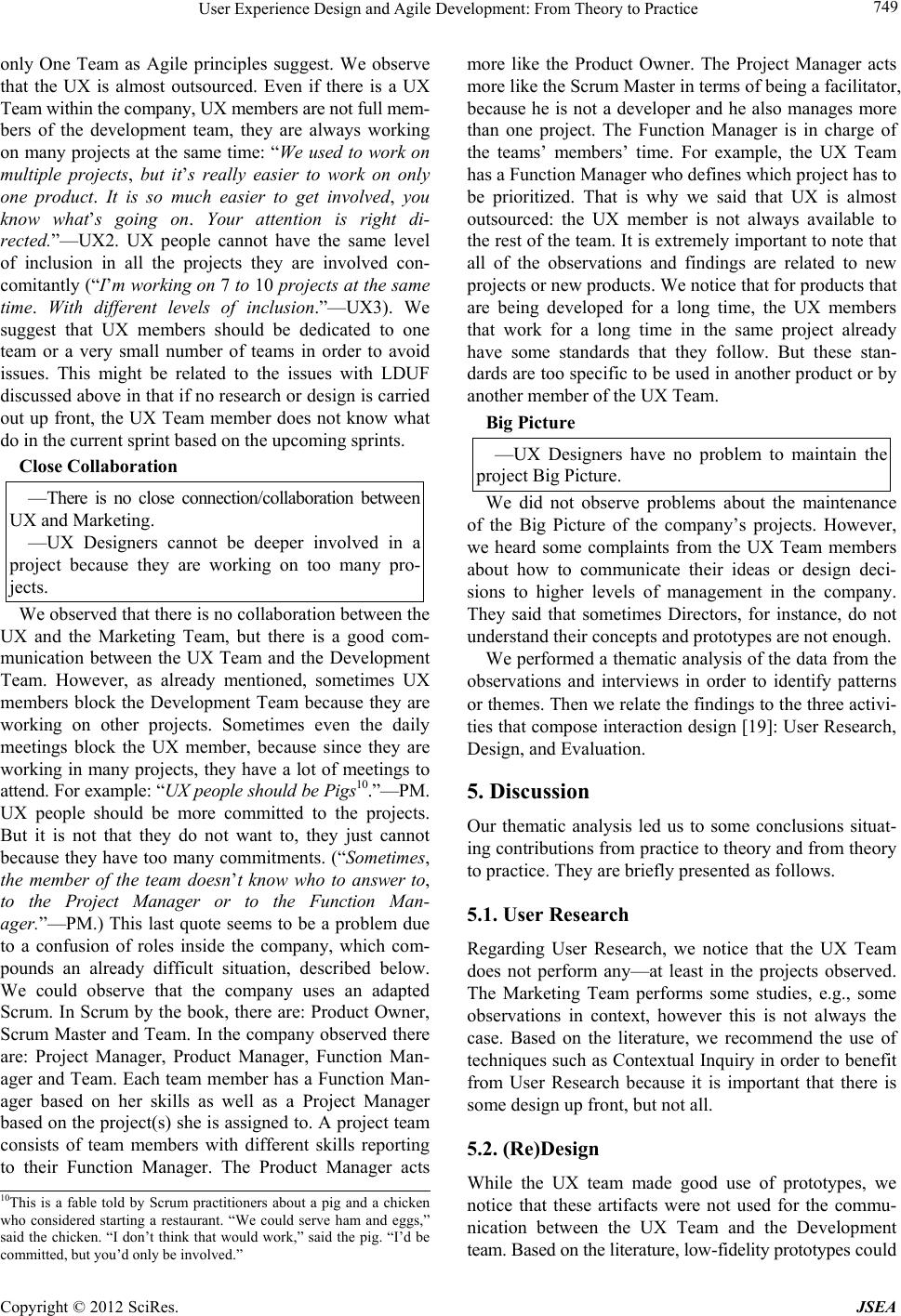

|