Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

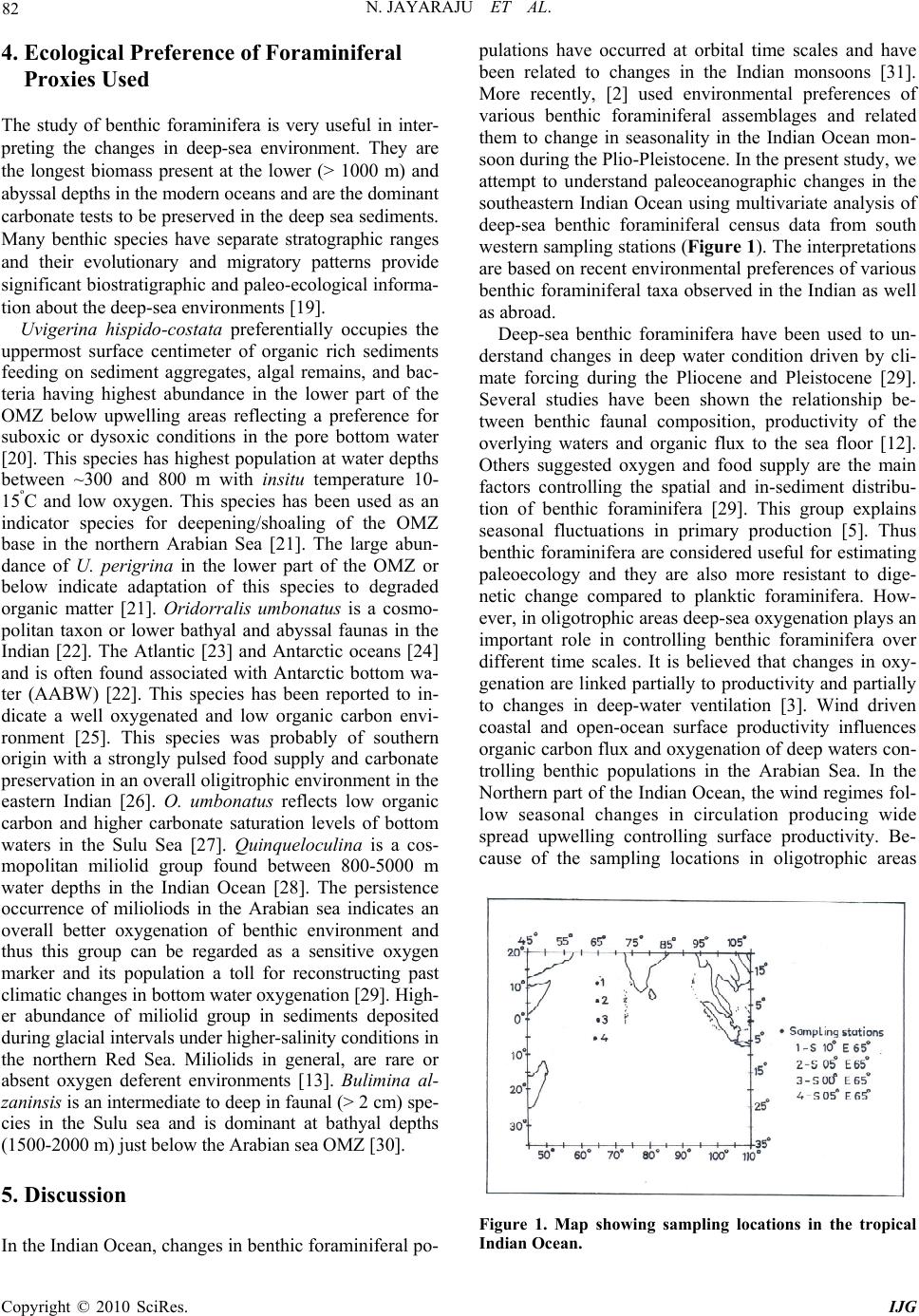

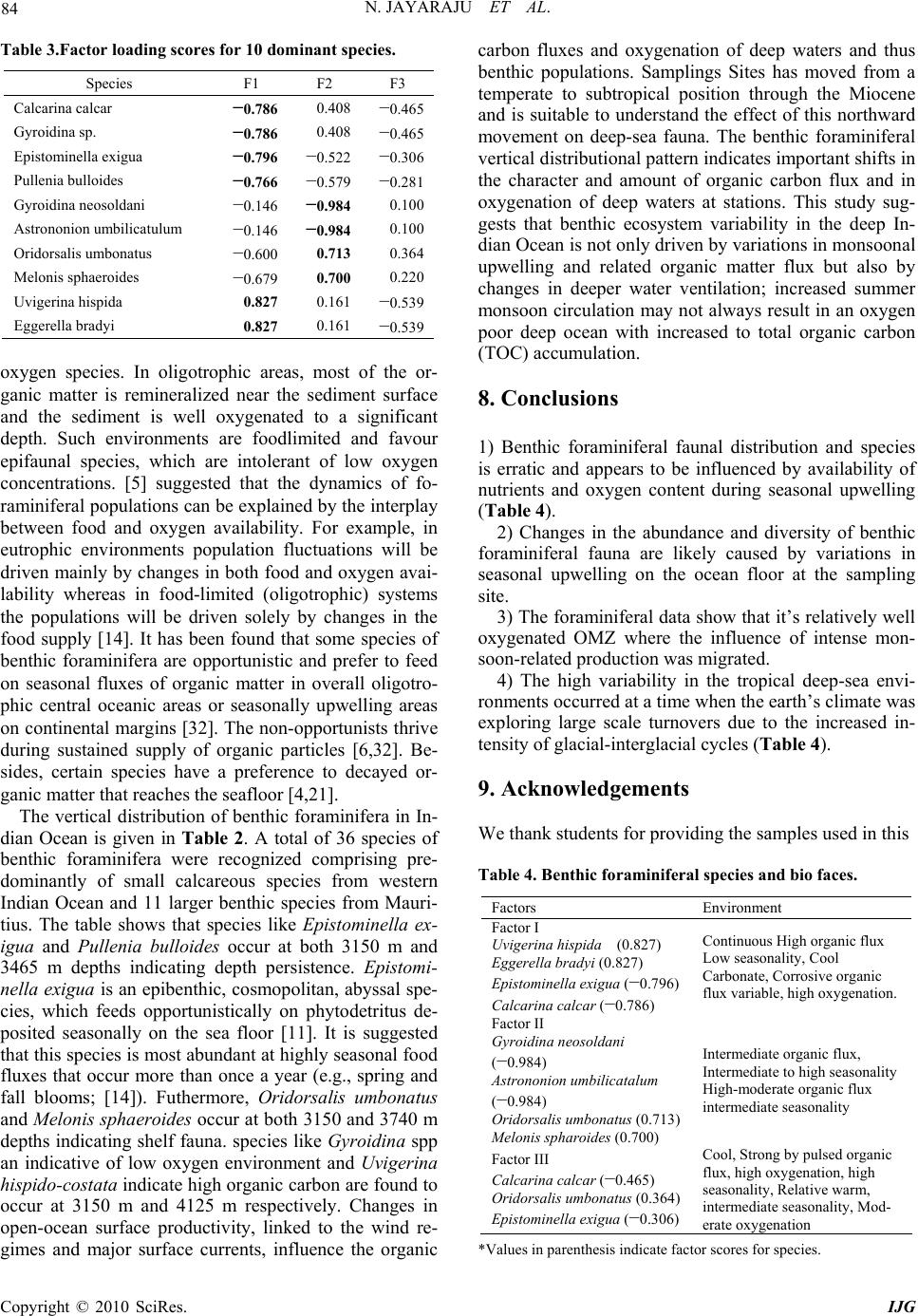

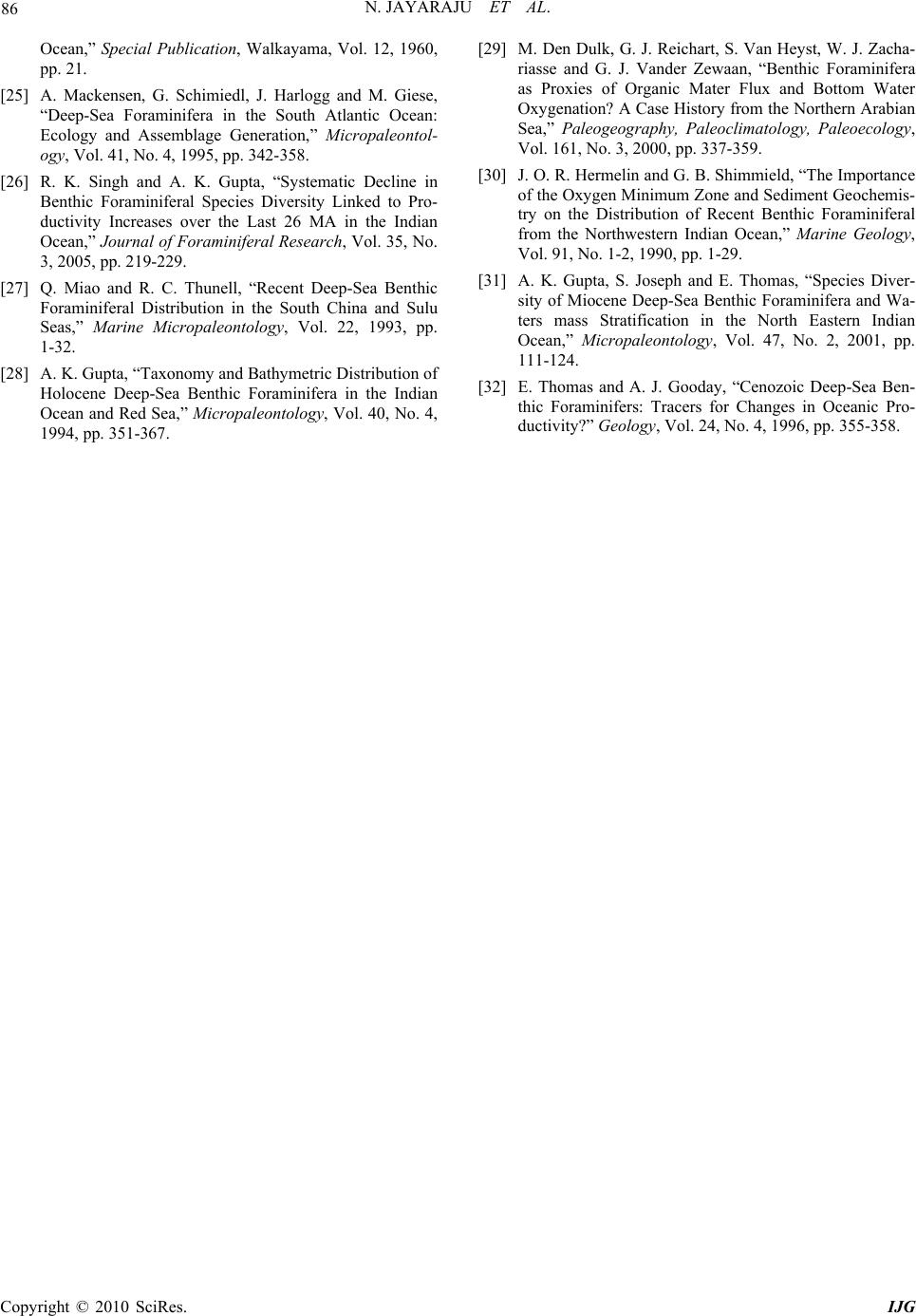

International Journal of Geosciences, 2010, 1, 79-86 doi:10.4236/ijg.2010.12011 Published Online August 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ijg) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG Deep-Sea Benthic Foraminiferal Distribution in South West Indian Ocean: Implications to Paleoecology Nadimikeri Jayaraju1, Balam Chinnapolla Sundara Raja Reddy2, Kambham Reddeppa Reddy2, Addula Nallappa Reddy3 1Department of Geology & Geoinformatics, Yogi Vemana University, Kadapa, India 2Department of Geology, Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati, India 3ONGC Regional Geoscience laboratory, Chennai, India E-mail: nadimikeri@gmail.com Received May 14, 2010; revised June 13, 2010; accepted July 11, 2010 Abstract Five grab samples from the southwestern part of the Indian ocean were collected by ORV Sagar Kanya dur- ing the third expedition to the southern Indian ocean in June 2009. The sediment samples have been analyzed and recorded 36 benthic foraminiferal species belonging to 21 genera and 3 suborders. All the species were taxonomically identified, SEM photographed and illustrated. Deep sea-benthic foraminiferal species at dif- ferent locations of South of West India Ocean (3150-4125 m water depth) is examined in terms of number of species (n) and diversity (d). The observed depth ranges of benthic foraminifera have been documented to recognize their bathymetric distribution. The valves of these parameters reached their maximum at 3190 m water depth. Productivity continued in the Indo-Pacific Ocean (the biogenic boom) and the Oxygen mini- mum zone (OMZ) intensified over large parts of Indian Ocean continually. The diversity values show more abrupt trend as depth increases. Species like Epistominella exigua and Pullenia bulloides occur at both 3150 m & 3465 m depths indicating depth persistence. Further, Oridorsalis umbonatus and Melonis sphaeroides occur at both 3150 m & 3465 m depths. Species like Gyroidina sp an indicate of low oxygen environment and Uvigerina hispida-costata indicative of high organic carbon are found to occur at 3150 m & 3740 m re- spectively. Factor analysis and Pearson correlation matrix was performed on foraminiferal census data of 10 highest ranked species which are present in at least one sample. 3 factors were obtained accounting for 72.81% of the total variance. Thus the study suggests that fluctuations in species diversity at the locations of the present study were related to changes in productivity during the geological past. Further, the faunal data do indicate the early Holocene Indian Ocean was influenced by increased ventilation perhaps by North At- lantic deep water and or circumpolar deep waters. Keywords: Paleoecology, Benthicforaminifera, Holocene, Indian Ocean 1. Introduction Considerable amount of work has been done to under- stand Paleoecology, Paleoclimatic and Paleoocenogra- phic evolution of the Indian Ocean during Pleistocene and Holocene using faunal data [1,2]. Benthic foraminif- era have substantial scope in paleoecological studies be- cause of their wide distribution in all marine environ- ments and the high fossilization potential of their tests. During the last three decades, several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the distribution patterns and ecologic preferences of this group. For instance, benthic foraminifera have been used extensively to reconstruct the past variability in deep water properties in different ocean basins explained the relationship of various taxa with different levels of deep-sea oxygenation, whereas other studies have related benthic assemblages to the intensity of deep sea currents and ventilation [3]. The fact that benthic foraminifera occupy both epifaunal and infaunal microhabitats led some workers to suggest that sediment and pore water properties may be more impor- tant than bottom water conditions in controlling benthic foraminiferal distribution [4,5]. Other studies indicate that benthic foraminiferal assemblages are strongly cor-  N. JAYARAJU ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG 80 related with productivity of the overlying surface waters and the flux of organic matter to the seafloor. Faunal proxy data suggests major changes in the Cenozoic Earths climate forms relatively warm and equable cli- mate in the Paleocene to cold conditions with nearly frizzing temperatures at the poles in the Pliocene [6]. Other changes during this time include those in ocean circulation and productivity and opening and closing of different seaways, including the closure of Tethyan Sea- ways, including the closure of the Panamanian sea way in the Pliocene [7]. The changes in Antarctic climate during the middle Miocene brought significant changes in ocean surface productivity and oxygenation of deep waters as well [8], which had an impact on the oceans faunal regime. Productivity has increased significantly in all oceans since the late middle Miocene (~ 13 Ma). The increased glaciations on Antarctica may have intensified wind regimes, loading to widespread open-ocean as well as coastal upwelling over large parts of the Indian, Pa- cific and Atlantic oceans during the middle Miocene [8]. These productivity events are believed to have triggered the “biogenic bloom” and expansion of the oxygen mini- mum zone in large parts of the intermediate water of the Indian and Pacific Oceans in the late middle Miocene, about 15 Ma [9]. With these climatic and oceanic changes, deep-sea faunal diversity changed considerably [10]. Availability of nutrients, heterogeneity of the habitat and predation are factors controlling diversity patterns in the deep-sea fauna [10]. It’s also observed, low values of species diversity during intervals of environmental insta- bility in the South Indian Ocean in the middle – late Miocene. The high productivity and subsequent micro- bial decay of organic matter, as well as biotic respiration and other oceanographic factors, lead to extremely low oxygen concentrations in the water column, forming a pronounced oxygen minimum zone (OMZ). Underlying sediments thus contain a geological record of changes in the SW monsoon and OMZ variability [11]. Benthic fo- raminifera dominate modern ocean floor meiobenthic communities, and in many deep-sea areas, constitute a substantial proportion of the eukaryotic biomass [6]. Due to their high fossilization potential they area very useful in paleooceanograpgic studies. The factors controlling their distribution and abundance are complex and con- troversial [12], but it appears that two usually inversely related parameters, the flux of organic particulate matter to the sea floor and oxygen concentrations of bottom wa- ter and pore waters, are major controlling variables [5]. Other factors which have been suggested (and some of which are not independent of these two) include the type of food supply, bathymetry, sediment type, chemistry of bottom waters current flow intensity and hydrostatic pressure [13]. The supply of organic matter from the euphotic zone to the ocean floor exerts a strong influence on the abundance and biomass of deep-sea benthic fo- raminifera [12] as on other deep-sea organisms. The composition of benthic foraminiferal assemblages is closely related to the amount and quality of organic matter. Assemblages dominated by the in faunal species Bolivina, Bulimina, Melonis and Uvigerina commonly occur in areas with high, continuous fluxes of organic matter to the sea floor, often associated with reduced bottom water oxygen concentrations. It has been shown, however, that Uvigerina spp are correlated to organic flux and not to low oxygen conditions. To understand the distribution and diversity of benthic foraminifera at dif- ferent bathymetric levels, the present study was carried out. Benthic foraminiferal species used in the faunal study include, Uvigerina hispida-costata which was dominant during times of high productivity and /or low oxygen and Oridorsalis umbonatus and Quinqueloculina parkeri characteristic of well oxygenated, oligotrophic conditions. Changes in organic flux to the sea floor due to variations in surface productivity modulate deep-sea faunal composition [3]. The amount of organic flux to the sea floor not only depends on surface production but also on the nature of deep-sea column. Well oxygenated deep-sea circulation may cause remineralization of or- ganic carbon resulting in little organic material reaching the sea floor [14]. To understand if the changes in the surface and deep-water column of the tropical condition ocean driven by the Indian ocean climate (monsoon) and deep-sea circulation, an attempt has been made to ana- lyze deep-sea benthic foraminifera from varying depths from (3150 m, 3465 m and 4125 m) (Figure 1). The in- vestigations of benthic foraminifera from south west In- dian Ocean provided data on the species distribution and species-specific relations for different depths and areas. These data were later used to distinguish faunistive provinces with the implication to paleoecology. The study presented is aimed at the description of the bio- geography and ecology of foraminifera communities based on the data about the dominant species in the tropical Indian Ocean and their occurrences in other ar- eas of the world Ocean. 2. Materials and Methods The study sites are located at different depths of 3150 m (N 10º E 65º ); 3465 m (N 5º E 65º); 3790m (N 0º E 65º ) and 4125 m (N 5º E 65º) in the South West Indian Ocean. The samples were collected from ORV Sagar Kanya during the third expedition to the southern Indian Ocean by National Center for Antarctica and Ocean Research, (NCAOR) Goa, India, in June, 2009. Sediment samples were transferred into plastic bags and frozen until analy- sis was carried out. The sediment samples were first washed over a sieve which is an average opening of 0.625 mm. This process helps to wash the sample free of sea water, fixatives, and the fine silt and clay size parti-  N. JAYARAJU ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG 81 cles. Then a sample was air dried and a suitable sample weighing about 100 grams was obtained by coning and quartering. Samples were spilt using a micro splitter and all benthic foraminifera were picked and identified [15]. Quantitatively, foraminifera could not be separated easily with washing carbon tetra chloride only, so a mixture of Bromoform (specific gravity 2.8) and Acetone (specific gravity 2.4) were used to obtain about 15% crop from the sediment [16]. The residue was examined under a stereo binocular microscope for any left out fauna. Such tests were handpicked by a very fine pointed long haired welted Windsor Newton sable hair brush (“0”). The fauna thus obtained was sorted, counted and identified under a stereo binocular microscope using medium to high magnifications (6.3 × 2.5; 6.3 × 4.0). The sampling procedures especially sieving and drying reduce the number of the most fragile arenaceous foraminifera (Ta- ble 2). Statistical analysis was done by multivariate analysis, correlation analysis was applied to compare and correlate the data generated based on bathymetry [17]. Details of the hydrography, primary productivity and upper ocean mixed layer dynamics are given earlier [18]. To day, the depth of site 4125 m (S 10º E 65º) is close to the calcite Lysocline which, in this part of the Indian Ocean, has been considered to lie between 4000-4200 m and approaches calcite composition depth (CCD). This area was selected because it is a relatively flat area, far from continental shelf to the east and the mid-ocean ridge to the west and so is unlikely to be influenced by strong down slopes or adjective process. Recent sedi- ments in the study area are calcareous oozes with rich biogenic carbonate with CaCO3. In this study, the abso- lute abundance and species diversity of fauna in the sediment fraction of > 63 µm in weight % of total sedi- ment. In addition, the state of preservation of foraminif- eral tests was noted in the samples. Benthic foraminiferal species Uvigerina hispida-costata, Oridorsalis umbona- tus and Quinqueloculina spp to understand changes in deep-sea organic carbon and oxygen content. Approxi- mately 100-300 specimens of benthic foraminifera were picked from a suitable sample and their diversity and distribution were calculated (Table 1). 3. General Setting Sampling stations are, at present located in subtropical waters. In the present-day locations, is bathed by low- oxygen and relatively productive deep waters of the northern Indian origin deep-sea benthic foraminife ra- provides useful information on the influence of various deep-water masses in the region. The physico-chemical properties of the surface waters in the western Indian Ocean are strongly influenced by African through flow water because of substantial export of freshwater and heat from the Pacific into the Indian Ocean through the Indian seas. At present, the area is influenced by the summer monsoon winds producing major divergence and an open-ocean upwelling. In the present-day ocean, the in situ primary production in the surface waters is be- tween 200 and 300 mg during the summer monsoon, which is reduced during the winter monsoon. Table 1. Benthic foraminiferal species number with depth (m). Depth (m) S.No.Species 3150 3465 3790 4125 1 Marginopora vertibralis 164 2 Sorites marginalis 131 3 Borelis schlumbergeri 152 4 Heterostegina depressa 140 5 Elphidium crispum 131 6 Ammonia tepida 129 7 Quinqueloculina parkeri 153 8 Spirillina decorata 146 9 Textularia sagittula 133 10 Eponides repandus 136 11 Calcarina calcar 166 12 Gyroidina sp. 156 13 Pyrgo murrhina 145 14 Bulimina alazanensis 135 15 Pullenia subcarinata 148 16 Discopulvinulina bertheloti 164 17 Epistominella exigua 281 292 18 Pullenia bulloides 136 156 19 Gyroidina neosoldani 145 20 Astrononion umbilica- tulum 142 21 Planulina wuellerstorfi 132 22 Oolina apiculata 163 23 Oolina desophora 155 24 Laticarinina pauperata 145 25 Fissurina sp. 165 26 Fissurina alveolata 148 27 Nummoloculina sp. 156 28 Pullenia quinqueloba 148 29 Lagena stelligera 158 30 Oridorsalis umbonatus 286 278 31 Melonis sphaeroides 279 214 32 Chilostomella ovoidea 153 33 Uvigerina hispida 289 34 Uvigerina his- pido-costata 163 35 Eggerella bradyi 180 36 Karreriella bradyi 163  N. JAYARAJU ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG 82 4. Ecological Preference of Foraminiferal Proxies Used The study of benthic foraminifera is very useful in inter- preting the changes in deep-sea environment. They are the longest biomass present at the lower (> 1000 m) and abyssal depths in the modern oceans and are the dominant carbonate tests to be preserved in the deep sea sediments. Many benthic species have separate stratographic ranges and their evolutionary and migratory patterns provide significant biostratigraphic and paleo-ecological informa- tion about the deep-sea environments [19]. Uvigerina hispido-costata preferentially occupies the uppermost surface centimeter of organic rich sediments feeding on sediment aggregates, algal remains, and bac- teria having highest abundance in the lower part of the OMZ below upwelling areas reflecting a preference for suboxic or dysoxic conditions in the pore bottom water [20]. This species has highest population at water depths between ~300 and 800 m with insitu temperature 10- 15ºC and low oxygen. This species has been used as an indicator species for deepening/shoaling of the OMZ base in the northern Arabian Sea [21]. The large abun- dance of U. perigrina in the lower part of the OMZ or below indicate adaptation of this species to degraded organic matter [21]. Oridorralis umbonatus is a cosmo- politan taxon or lower bathyal and abyssal faunas in the Indian [22]. The Atlantic [23] and Antarctic oceans [24] and is often found associated with Antarctic bottom wa- ter (AABW) [22]. This species has been reported to in- dicate a well oxygenated and low organic carbon envi- ronment [25]. This species was probably of southern origin with a strongly pulsed food supply and carbonate preservation in an overall oligitrophic environment in the eastern Indian [26]. O. umbonatus reflects low organic carbon and higher carbonate saturation levels of bottom waters in the Sulu Sea [27]. Quinqueloculina is a cos- mopolitan miliolid group found between 800-5000 m water depths in the Indian Ocean [28]. The persistence occurrence of milioliods in the Arabian sea indicates an overall better oxygenation of benthic environment and thus this group can be regarded as a sensitive oxygen marker and its population a toll for reconstructing past climatic changes in bottom water oxygenation [29]. High- er abundance of miliolid group in sediments deposited during glacial intervals under higher-salinity conditions in the northern Red Sea. Miliolids in general, are rare or absent oxygen deferent environments [13]. Bulimina al- zaninsis is an intermediate to deep in faunal (> 2 cm) spe- cies in the Sulu sea and is dominant at bathyal depths (1500-2000 m) just below the Arabian sea OMZ [30]. 5. Discussion In the Indian Ocean, changes in benthic foraminiferal po- pulations have occurred at orbital time scales and have been related to changes in the Indian monsoons [31]. More recently, [2] used environmental preferences of various benthic foraminiferal assemblages and related them to change in seasonality in the Indian Ocean mon- soon during the Plio-Pleistocene. In the present study, we attempt to understand paleoceanographic changes in the southeastern Indian Ocean using multivariate analysis of deep-sea benthic foraminiferal census data from south western sampling stations (Figure 1). The interpretations are based on recent environmental preferences of various benthic foraminiferal taxa observed in the Indian as well as abroad. Deep-sea benthic foraminifera have been used to un- derstand changes in deep water condition driven by cli- mate forcing during the Pliocene and Pleistocene [29]. Several studies have been shown the relationship be- tween benthic faunal composition, productivity of the overlying waters and organic flux to the sea floor [12]. Others suggested oxygen and food supply are the main factors controlling the spatial and in-sediment distribu- tion of benthic foraminifera [29]. This group explains seasonal fluctuations in primary production [5]. Thus benthic foraminifera are considered useful for estimating paleoecology and they are also more resistant to dige- netic change compared to planktic foraminifera. How- ever, in oligotrophic areas deep-sea oxygenation plays an important role in controlling benthic foraminifera over different time scales. It is believed that changes in oxy- genation are linked partially to productivity and partially to changes in deep-water ventilation [3]. Wind driven coastal and open-ocean surface productivity influences organic carbon flux and oxygenation of deep waters con- trolling benthic populations in the Arabian Sea. In the Northern part of the Indian Ocean, the wind regimes fol- low seasonal changes in circulation producing wide spread upwelling controlling surface productivity. Be- cause of the sampling locations in oligotrophic areas Figure 1. Map showing sampling locations in the tropical Indian Ocean.  N. JAYARAJU ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG 83 with high dissolved oxygen content during the studies period, the changes in benthic foraminiferal population might have been linked to the supply of organic food. 6. Results The absolute abundances (number of specimens per gram bulk sediment) of benthic foraminifera fluctuate largely. A total of 36 species of benthic foraminifera were recog- nized comprising predominantly of small calcareous species. In the samples (3150 m, 3465 m, 3790 m and 4125 m water depth) used in the benthic foraminiferal distribution, the abundant species occur in sample 3150 m are Gyroidina sp, Pyrgo murrhina, Bulimina alazanensis Pullenia subcarinata, Discopulvinulina bertheloti, Epis- tominella exigua and Pullenie bulloides; at sample 3465 m depth are Epistominella exigua, Pullenia bulloides, Gyroidina neosoldani and Astrononion umbilicatalum; at sample 3790 m depth are Planulina wullerstorfi, Oolina apiculata, Oolina desophora, Laticarinina pauperata, Fissurina alveolata, Nummoloculina sp, Pullenia quin- queloba, Lagena stelligera, Oridorsalis umbonatus, Melonis sphaeroides and Chilostomella ovoidea at sam- ple 4125 m water depths are Uvigerina hispido-costata, Eggerella bradyi and Karreriella bradyi. 7. Factor Analysis The foraminiferal data census of 10 species was sub- jected to the factor analysis. The analysis yield three factors namely Factor 1 (37.11%), Factor 2 (25.87%) and Factor 3 (10.83%) accounting for 72.81% (Table 3). Factor 1 Factor 1 represented by Uvigerina hispida (0.827), Eggerella bradyi (0.827), Epistominella exigua (−0.796) and Pullenia bulloides (0.766). Uvigerina hispida relates continuous, high organic flux, low seasonality. Eggerella bradyi reflects cool, carbonate corrosive organic flux, variable and high oxygenation [8]. Factor 2 Factor 2 is dominated by Gyroidina neosoldani (− 0.984), Astrononion umbilicatulum (−0.984); Oridorsalis umbonatus (0.713) and Melonis sphaeroides (0.700). This factor indicates intermediate organic flux, interme- diate to high seasonality, high-moderate organic flux, intermediate high seasonality, refractory organic matter. However, Oridorsalis umbonatus tend to reflect rela- tively warm intermediate organic flux, intermediate sea- sonality, and moderate oxygenation [8]. Factor 3 Factor 3 comprises of Calcarina calcar (−0.465), Ori- dorsalis umbonatus (0.364) and are Epistominella exigua (−0.306). Three species indicate cool strongly pulsed, low to intermediate organic flux, high seasonality. In addition, relatively warm intermediate organic flux, intermediate seasonality, moderate oxygenation is also reflected. A cross plot of Factors 1 & 2 and Factors 1& 3 gives district information of faunal assemblages a set clustered similar factor. Pearson correlation matrix of dominated species (Table 2) shows the distinct positive and nega- tive correlation with a specific species. Calcarina calcar and Gyroidina sp shows high positive relation with Melonis sphaeroides (0.717), Oridorsalis umbonatus (0.594), Epistominella exigua (0.555). Epistominella exigua and Pullenia bulloides correlated positively with Pullenia bulloides (0.998), Gyroidina neosoldani (0.599) and Astrononion umbilicatulum (0.599). Where as Gy- roidina neosoldani, Astrononion umbilicatulum, Oridor- salis umbonatus, Melonis sphaeroides shows negative correlation with other species (Table 2). The vertical distribution of living benthic foraminifera within the sediment is controlled largely by a combination of oxy- gen content and organic carbon levels [4,13]. In eutro- phic regions, oxygen decreases close to the sediment surface and becomes a limiting factor, favouring low- Table 2. Pearson correlation matrix of 10 dominant species. Variables Calcarina calcar Gyroid- ina sp. Epistominella exigua Pullenia bulloides Gyroidina neosoldani Astrononion umbilicatulum Oridorsalis umbonatus Melonis sphaeroides Uvigerina hispida Eggerella bradyi Calcarina calcar 1 Gyroidina sp. 1.000 1 Epistominella exigua 0.555 0.5551 Pullenia bulloides 0.496 0.4960.998 1 Gyroidina neo- soldani −0.333 −0.333 0.599 0.653 1 Astrononion umbilicatulum −0.333 −0.333 0.599 0.653 1.000 1 Oridorsalis um- bonatus 0.594 0.594−0.005 −0.055 −0.577 −0.577 1 Melonis sphaer- oides 0.717 0.7170.108 0.053 −0.568 −0.568 0.987 1 Uvigerina hispida −0.333 −0.333 −0.577 −0.575 −0.333 −0.333 −0.577 −0.568 1 Eggerella bradyi −0.333 −0.333 −0.577 −0.575 −0.333 −0.333 −0.577 −0.568 1.000 1  N. JAYARAJU ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG 84 Table 3.Factor loading scores for 10 dominant species. Species F1 F2 F3 Calcarina calcar −0.786 0.408 −0.465 Gyroidina sp. −0.786 0.408 −0.465 Epistominella exigua −0.796 −0.522 −0.306 Pullenia bulloides −0.766 −0.579 −0.281 Gyroidina neosoldani −0.146 −0.984 0.100 Astrononion umbilicatulum −0.146 −0.984 0.100 Oridorsalis umbonatus −0.600 0.713 0.364 Melonis sphaeroides −0.679 0.700 0.220 Uvigerina hispida 0.827 0.161 −0.539 Eggerella bradyi 0.827 0.161 −0.539 oxygen species. In oligotrophic areas, most of the or- ganic matter is remineralized near the sediment surface and the sediment is well oxygenated to a significant depth. Such environments are foodlimited and favour epifaunal species, which are intolerant of low oxygen concentrations. [5] suggested that the dynamics of fo- raminiferal populations can be explained by the interplay between food and oxygen availability. For example, in eutrophic environments population fluctuations will be driven mainly by changes in both food and oxygen avai- lability whereas in food-limited (oligotrophic) systems the populations will be driven solely by changes in the food supply [14]. It has been found that some species of benthic foraminifera are opportunistic and prefer to feed on seasonal fluxes of organic matter in overall oligotro- phic central oceanic areas or seasonally upwelling areas on continental margins [32]. The non-opportunists thrive during sustained supply of organic particles [6,32]. Be- sides, certain species have a preference to decayed or- ganic matter that reaches the seafloor [4,21]. The vertical distribution of benthic foraminifera in In- dian Ocean is given in Table 2. A total of 36 species of benthic foraminifera were recognized comprising pre- dominantly of small calcareous species from western Indian Ocean and 11 larger benthic species from Mauri- tius. The table shows that species like Epistominella ex- igua and Pullenia bulloides occur at both 3150 m and 3465 m depths indicating depth persistence. Epistomi- nella exigua is an epibenthic, cosmopolitan, abyssal spe- cies, which feeds opportunistically on phytodetritus de- posited seasonally on the sea floor [11]. It is suggested that this species is most abundant at highly seasonal food fluxes that occur more than once a year (e.g., spring and fall blooms; [14]). Futhermore, Oridorsalis umbonatus and Melonis sphaeroides occur at both 3150 and 3740 m depths indicating shelf fauna. species like Gyroidina spp an indicative of low oxygen environment and Uvigerina hispido-costata indicate high organic carbon are found to occur at 3150 m and 4125 m respectively. Changes in open-ocean surface productivity, linked to the wind re- gimes and major surface currents, influence the organic carbon fluxes and oxygenation of deep waters and thus benthic populations. Samplings Sites has moved from a temperate to subtropical position through the Miocene and is suitable to understand the effect of this northward movement on deep-sea fauna. The benthic foraminiferal vertical distributional pattern indicates important shifts in the character and amount of organic carbon flux and in oxygenation of deep waters at stations. This study sug- gests that benthic ecosystem variability in the deep In- dian Ocean is not only driven by variations in monsoonal upwelling and related organic matter flux but also by changes in deeper water ventilation; increased summer monsoon circulation may not always result in an oxygen poor deep ocean with increased to total organic carbon (TOC) accumulation. 8. Conclusions 1) Benthic foraminiferal faunal distribution and species is erratic and appears to be influenced by availability of nutrients and oxygen content during seasonal upwelling (Table 4). 2) Changes in the abundance and diversity of benthic foraminiferal fauna are likely caused by variations in seasonal upwelling on the ocean floor at the sampling site. 3) The foraminiferal data show that it’s relatively well oxygenated OMZ where the influence of intense mon- soon-related production was migrated. 4) The high variability in the tropical deep-sea envi- ronments occurred at a time when the earth’s climate was exploring large scale turnovers due to the increased in- tensity of glacial-interglacial cycles (Table 4). 9. Acknowledgements We thank students for providing the samples used in this Table 4. Benthic foraminiferal species and bio faces. Factors Environment Factor I Uvigerina hispida (0.827) Eggerella bradyi (0.827) Epistominella exigua (−0.796) Calcarina calcar (−0.786) Continuous High organic flux Low seasonality, Cool Carbonate, Corrosive organic flux variable, high oxygenation. Factor II Gyroidina neosoldani (−0.984) Astrononion umbilicatalum (−0.984) Oridorsalis umbonatus (0.713) Melonis spharoides (0.700) Intermediate organic flux, Intermediate to high seasonality High-moderate organic flux intermediate seasonality Factor III Calcarina calcar (−0.465) Oridorsalis umbonatus (0.364) Epistominella exigua (−0.306) Cool, Strong by pulsed organic flux, high oxygenation, high seasonality, Relative warm, intermediate seasonality, Mod- erate oxygenation *Values in parenthesis indicate factor scores for species.  N. JAYARAJU ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG 85 study, collected from Indian Ocean expedition organized by National Center for Antarctica and Ocean Research (NCAOR), in Sagar Kanya, 2009. The very useful com- ments of the anonymous reviewers significantly im- proved the manuscript and are grateful acknowledged. SEM microphotographs are taken at Oil Natural Gas Corporation, Regional Labs, Chennai, India. Thanks are due to Prof A. R. Reddy, Vice-Chancellor, Yogi Vemana University, Kadapa for encouragement. 10. References [1] D. Kroon, T. N. F. Steens and S. R. Froelstra, “Onset of Monsoonal Related Upwelling in the Western Arabian Sea as Revealed by Plantonic Foraminifera,” In: W. L. Prell, N. Niitsuma, et al., Eds., Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, College Station, Texas, Vol. 117, 1991, pp. 257-264. [2] A. K. Gupta, D. M. Anderson and T. J. Overpeck, “Abrupt Changes in the Asian South West Monsoon dur- ing the Holocene and their Links to the North Atlantic Ocean,” Nature, Vol. 421, No. 6921, 2003, pp. 354-356. [3] A. K. Gupta and E. Thomas, “Latest Miocene through Pleistocene Paleoceanography, Evolution of the NW Indian Ocean (DSDP Site 21); Global and Regional Factors,” Pa- leooceanography, Vol. 14, No. 1, 1999, pp. 111-124. [4] B. H. Corliss, “Recent Deep-Sea Benthic Foraminiferal Distribution in the South Eastern Indian Ocean: Inferred Bottom Water Recites and Ecological Implications,” Ma- rine Geology, Vol. 31, No. 1-2, 1979, pp. 115-138. [5] A. J. Gooday, “Ephifaunal and Shallow Infaunal Fo- raminiferal Communities at Three Abyssal NE Atlantic Sites Subject to Differing Phytodetritus Input Regimes,” Deep-Sea Research, Vol. 43, No. 9, 1996, pp. 1395-1421. [6] J. Zachos, M. Pagni, L. Sloan, E. Thomas and K. Bilheps, “Trends, Rhythms and Abbreviations in Global Climate 65 Ma to Present,” Science , Vol. 292, No. 5517, 2001, pp. 686-693. [7] G. H. Hang and R. Tidemanm, “Effect of the Formation of the Isthmus of Panama on Atlantic Ocean Therohaline Circulation,” Nature, Vol. 393, No. 6686, 1998, pp. 673-676. [8] A. K. Gupta, R. K. Singh, S. Joseph and E. Thomas, “In- dian Ocean High Productivity Event (10-8 Ma): Linked to a Global Cooling or to the Incitation of the Indian Monsoons?” Geology, Vol. 32, No. 9, 2004, pp. 753-756. [9] C. S. Hernoylion and R. M. Owen, “Late Miocene-Early Pliocene Biogenic Bloom: Evidence from Low-Produc- tivity Regions of the Indian and Atlantic Oceans,” Pa- leogeography, Vol. 16, No. 1, 2001, pp. 95-100. [10] E. Thomas and A. J. Gooday, “Cenozoic Deep-Sea Ben- thic Foraminifers: Tracers for Changes in Oceanic Pro- ductivity,” Geology, Vol. 24, No. 4, 1996, pp. 355-358. [11] A. K. Gupta, M. Sundar Raj, K. Mohan and D. Soma, “A Major Change in Monsoon – Driven Productivity in the Tropical Indian Ocean during Ca 1.2-0.9 Mys: Fora- miniferal Faunal and Stable Isotope Data,” Paleogeo- graphy, Paleoclimatology, Paleoecology, Vol. 261, No. 3-4, 2008, pp. 234-245. [12] C. W. Smart, E. Thomas and A. T. S. Ramsay, “Mid- dle-Late Miocene Benthic Foraminifera in a Western Equatorial Indian Ocean Depth Transect: Paleooceno- graphic Implications,” Paleogeography, Paleoclimatol- ogy, Paleoecology, Vol. 247, No. 3-4, 2007, pp. 402-420. [13] F. J. Jorissen, H. C. Destigter and J. Widemark, “A Con- ceptual Model Explaining Benthic Foraminiferal Micro- habitats,” Marine Micropaleontology, Vol. 26, No. 1, 1995, pp. 3-15. [14] G. Schmiedl and A. Mackensen, “Multi Species Stable Isotopes of Benthic Foraminifers Revels Past Changes of Organic Matter Decomposition and Deep Water Oxy- genation in the Arabian Sea,” Paleooceangraphy, Vol. 21. 2006, p. 11. [15] A. R. Loeblich and H. Tappan, “Foraminiferal Genera and their Classification,” Van Nostrand Rinhold Camp, New York, 1987. [16] T. G. Gibson and W. M. Walker, “Floatation Methods for Obtaining the Foraminifera from Sediment Samples,” Jour au Paléo, Vol. 41. No. 5. 1967, pp. 1294-1297. [17] N. Jayaraju, B. C. Sudara Raja Reddy and K. R. Reddy, “Anthropogenic Impact on Andaman Coast Monitoring with Benthic Foraminifera, Andaman Sea, India,” Envi- ronmental Earth Science, Vol. 183, 2010, pp. 1049-1052. [18] R. K. Singh, and A. K. Gupta, “Systematic Decline in Benthic Foraminiferal Species Diversity Linked to Pro- ductivity Increases over the Last 26 MA in the Indian Ocean,” Journal of Foraminiferal Research, Vol. 35, No. 3, 2005, pp. 219-229. [19] K. R. Ajay and M. S. Srinivasan, “Pleistocene Oceano- graphic Changes Indicated by Deep-Sea Benthic Fo- raminifera in the Northern Indian Ocean,” Proceedings of Indian Academic Sciences, Vol. 103, No. 4, 1995, pp. 499-517. [20] G. Schmiedl and D. C. Lenschrer, “Oxygenation Changes in the Deep Western Arabian Sea during the Last 190,000 Years: Productivity versus Deep-Water Circulation,” Pa- leoocenography, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2005, pp. 1-14. [21] N. T. Jannik, W. J. Zachariasse and G. J. Van Deer Zwaan, “Living (Rose Bengal Stained) Benthic Fo- raminifera from the Pakistan Continental Margin (North- ern Arabian Sea),” Deep-Sea Research, Vol. 45, No. 9, 1998, pp. 1483-1513. [22] B. H. Corliss, “Recent Deep-Sea Benthic Foraminiferal Distribution in the South Eastern Indian Ocean: Inferred Bottom Water Recites and Ecological Implications,” Ma- rine Geology, Vol. 31, No. 1-2, 1979, pp. 115-138. [23] S. S. Streeter and N. J. Shackleton, “Paleocirculation of the Deep North Atlantic: 150,000 Year Record of Benthic Foraminifera and Oxygen-18,” Science, Vol. 203, No. 4376, 1979, pp. 168-171. [24] T. Uchio, “Biological Results of the Japanese Antarctic Expedition, Benthonic Foraminifera of the Antarctic  N. JAYARAJU ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG 86 Ocean,” Special Publication, Walkayama, Vol. 12, 1960, pp. 21. [25] A. Mackensen, G. Schimiedl, J. Harlogg and M. Giese, “Deep-Sea Foraminifera in the South Atlantic Ocean: Ecology and Assemblage Generation,” Micropaleontol- ogy, Vol. 41, No. 4, 1995, pp. 342-358. [26] R. K. Singh and A. K. Gupta, “Systematic Decline in Benthic Foraminiferal Species Diversity Linked to Pro- ductivity Increases over the Last 26 MA in the Indian Ocean,” Journal of Foraminiferal Research, Vol. 35, No. 3, 2005, pp. 219-229. [27] Q. Miao and R. C. Thunell, “Recent Deep-Sea Benthic Foraminiferal Distribution in the South China and Sulu Seas,” Marine Micropaleontology, Vol. 22, 1993, pp. 1-32. [28] A. K. Gupta, “Taxonomy and Bathymetric Distribution of Holocene Deep-Sea Benthic Foraminifera in the Indian Ocean and Red Sea,” Micropaleontology, Vol. 40, No. 4, 1994, pp. 351-367. [29] M. Den Dulk, G. J. Reichart, S. Van Heyst, W. J. Zacha- riasse and G. J. Vander Zewaan, “Benthic Foraminifera as Proxies of Organic Mater Flux and Bottom Water Oxygenation? A Case History from the Northern Arabian Sea,” Paleogeography, Paleoclimatology, Paleoecology, Vol. 161, No. 3, 2000, pp. 337-359. [30] J. O. R. Hermelin and G. B. Shimmield, “The Importance of the Oxygen Minimum Zone and Sediment Geochemis- try on the Distribution of Recent Benthic Foraminiferal from the Northwestern Indian Ocean,” Marine Geology, Vol. 91, No. 1-2, 1990, pp. 1-29. [31] A. K. Gupta, S. Joseph and E. Thomas, “Species Diver- sity of Miocene Deep-Sea Benthic Foraminifera and Wa- ters mass Stratification in the North Eastern Indian Ocean,” Micropaleontology, Vol. 47, No. 2, 2001, pp. 111-124. [32] E. Thomas and A. J. Gooday, “Cenozoic Deep-Sea Ben- thic Foraminifers: Tracers for Changes in Oceanic Pro- ductivity?” Geology, Vol. 24, No. 4, 1996, pp. 355-358. |