Open Journal of Psychiatry, 2012, 2, 253-257 OJPsych http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpsych.2012.24034 Published Online October 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojpsych/) The subgenual cingulate gyrus exhibits lower rates of bifurcation in schizophrenia than in controls, bipolar disorder and depression Matthew R. Williams1,2*, Ronald K. B. Pearce2, Steven R. Hirsch2, Olaf Ansorge3, Maria Thom4, Michael Maier5 1King’s College London, Institute of Psychiatry, De Crespigny Park, London, UK 2Neuropathology Unit, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Division of Neuroscience & Mental Health, Imperial College London, Charing Cross Hospital, London, UK 3Department of Neuropathology, The Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford, UK 4Institute of Neurology, UCL, London, UK 5Trust HQ, West London Mental Health NHS Trust, Middlesex, UK Email: *Matthew.r.williams@imperial.ac.uk Received 23 August 2012; revised 25 September 2012; accepted 5 October 2012 ABSTRACT The subgenual cingulate cortex has been found to be different in structure and function in mood and affec- tive disorders compared to healthy individuals. Im- aging studies have shown a decrease in function of the subgenual region in bipolar disorder and depression, with overall glial number shown to be decreased in these disorders. Decreases in subgenual grey matter in SZ have been observed also. In this neuropatho- logical study upon formalin-fixed coronal brain sec- tions we describe the morphological finding of de- creased frequency of subgenual cingulate crown bi- furcation (p = 0.02) as compared to control, bipolar and depression cases. This suggests that the cingulate cortex in schizophrenia may be morphologically dis- tinct in utero formation, potentially enabling an early identification of high-risk individuals. Keywords: Neuropathology; Schizophrenia; Cortical; Flattening 1. INTRODUCTION The subgenual cingulate cortex (SCC), part of Brodmann area 24a, is a region of interest in schizophrenia (SZ) and bipolar disorder (BPD). The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) lies on the medial surface of the cerebral hemi- sphere, covering the anterior part of the corpus callosum. It is defined as Broadmann area 24a. The ACC extends from the subgenual ventral terminus and continues rostal to the genu of the corpus callosum following the dorsal surface. The ACC has been implicated in regulation of emotional tional states, and in cognitive and attentional processes [1-5]. Projections travel directly from the SCC cortical grey matter to the corpus callosum. DTI studies have demonstrated decreased anisotropy in this cingulum bundle in patients with chronic SZ [6,7]. MRI imaging studies have shown a decrease in SCC grey matter vo- lume with decreased thickness in first episode schizo- phrenic patients [8,9] and in chronic disease and that the extent of thinning is related to illness duration [10-12] and a decrease in overall anterior cingulate volume [13]. Meta-analysis has suggested that the ACC in SZ has slightly decreased overall volume in SZ compared to controls, although there is significant heterogeneity in published articles [14]. Decreased ACC volume has also been observed in BPD in SCC cortical grey and white matter [15,16]. Smaller subgenual volumes have also been reported in unmedicated recurrent depressive dis- order (RDD) [17] and decreased ACC volume has been shown to correlate inversely with good clinical outcome [18]. Whilst stereological examination shows no change in overall volume in frontal cortices in schizophrenia [19, 20], cortical thinning has been observed in area 24a in both SZ and BPD [15,21], and a decrease in the grey mat- ter density in schizophrenia has also been reported in the orbitofrontal, cingulate and supramarginal cortices [22]. Some studies have suggested that in schizophrenia this thinning is more pronounced in the left side of the SCC [23,24], and also a tendency to thicker SCC cortical grey matter in major depression. In addition, there has been reported a decrease anterior cingulate white matter integ- rity in schizophrenia [25,26], suggesting a widespread *Corresponding author. OPEN ACCESS  M. R. Williams et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 253-257 254 issue with the morphology of anterior cingulate in these disorders. In this study we have taken coronal sections through the SCC in cases of SZ, BPD and RDD and control cases to examine the prevalence of cortical bifurcation. The size of the bifurcation within a gyrus means it is not visible by imaging and therefore requires a microscopic methodol- ogy. As the extent of folding of the cortex increases its surface area within a given gyral volume, potentially re- flecting the number of cortical neurons, this pattern of morphology may reflect a smaller cortical volume present from initial neurodevelopment of the cingulate. 2. METHODS A cohort of cases obtained from the Corsellis brain col- lection was used in neuropathological investigation of the cingulate in a series of studies (Williams, 2012). De- tails of the diagnostic groups are shown in Table 1. A total of 68 age and post-mortem interval (PMI) matched cases were used, with 20 control cases with no psychia- tric disorder (NPD), 12 SZ cases, 16 BPD cases and 20 cases of RDD. All cases underwent full neuropsychiatric review and were subject to full neuropathological screening. Cases involving heavy alcohol or drug use and those exhibiting significant pathology such as neurodegenerative disease, cerebral vascular disease, ischemic brain damage, CNS infections and traumatic brain injury were excluded from the study. The majority of samples come from the county of Essex but a smaller number came from national refer- rals [27]. Medical notes were reviewed by a consultant psychiatrist and patients were selected on fulfilment of the ICD-10 criteria for SZ and MDD, for robustness of diagnosis the brains of the three diagnostic groups all suffered from chronic illness. Assessment for any neu- rodegenerative, neurovascular or infectious pathology, including Parkinson’s disease, was undertaken by a consultant neuropathologist and affected patients ex- cluded. Patients with any recorded history of alcohol or drug abuse were also excluded. In SZ selection the presence of first-rank symptoms was a necessity, and cases with onset younger than 20 and older than 30 were excluded. Bilateral SCC and adjacent corpus callosum were dis- sected from formalin-fixed coronal blocks by a consult- ant neuropathologist and immersed in 10% formalin (4% formaldehyde v/v) until processing. Processing involved serial immersion in formalin, alcohols, methanol and xylene overnight. Tissue blocks were then embedded in paraffin wax and stored at 4˚C. Paraffin-embedded blocks were serially sectioned in the coronal plane at 10 µm and mounted on 25 × 75 mm electrostatic glass slides. Slides were blinded by an investigator not involved with the project before measurement. Sections from within 100 μm each case were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) and cresyl-violet (CV) for accurate examination of the anatomy of the structures. Sections for H & E stain were submerged in xylene for 30 minutes and serially placed in troughs of 2 × 100%, 90%, 70% ethanol (EtOH) and pure distilled water, each for 2 minutes. Slides were immersed in Mayer’s haematoxylin stain for 5 minutes and subsequently washed in distilled water. Specimens were placed in differentiating agent acid-alcohol (1% HCl/70% EtOH) for 10 seconds and into distilled water for 2 minutes. Sections were then immersed in 1% eosin stain for 5 minutes and washed in distilled water. Finally, specimens were dehydrated in serial baths of 70%, 90% and 2 × 100% IMS for 2 minutes each and submerged in xylene for 20 minutes before cover slips were fixed using DPX. Sections for CV stain were immersed in xylene for 30 minutes, incubated in 100%, 90% and then 70% al- cohol for 10 minutes each, before immersion in ultra- pure water. Sections were immersed in cresyl-violet stain for 5 minutes before washing in ultra-pure water and differentiation in 95% alcohol/ethanoic acid. After wash- ing in ultra-pure water sections were dehydrated in se- rial alcohols, immersed in xylene and mounted with DPX. Images of both H & E and CV stained coronal sections were taken using an Olympus microscope at 40× total magnification and captured at 2096 × 1536 resolution covering 2200 × 1600 µm area. Image analysis was per- formed using Image Pro Plus software (Media Cybernet- ics, US), calibrated using an optical graticule. In total for regions were measured in each case, both left and right SCC in H & E and CV sections. H & E sections were consulted to define the limits of the SCC grey matter. Measures were taken in CV and H & E stained sections Table 1. Summary group data. NPD—No Psychiatric Disorder; SZ—Schizophrenia; BPD—Bipolar Disorder; RDD—Recurrent Depressive Disorder. Age, PM delay and fixation time shown as means with SEM in brackets. Diagnosis n Age/y Sex ratio M/F PM Delay/h Fixation time/y NPD 20 65.5(2.34) 12/8 44.2(7.38) 10.2(0.52) SZ 12 58(6.44) 6/6 47.8(10.5) 11.1(1.30) BPD 16 56.1(5.21) 7/9 50.5(7.46) 19.4(2.02) RDD 20 47.6(3.12) 6/14 37.3(5.62) 10.4(0.88) Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  M. R. Williams et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 253-257 255 by a scoring of incidence of bifurcation in the SCC from both hemispheres from each case, after comparable mea- sures were taken from adjacent sulci and from the level of the crown. Bifurcation was defined as the existence of a sulcal-type projection into the crown of the primary SCC that were less than 50% the depth of both the cal- losal-cingulate sulcus and the primary cingulate sulcus, shown in Figure 1. Scoring of bifurcation of was taken from both left and right primary SCC in both CV and H & E slides, totalling two measures per hemisphere and four measures per case. Bifurcation had to be present in both CV and H & E slides for inclusion. Measures were performed blind to diagnosis and were unblinded by an investigator not involved with the pro- ject before analysis using Image Pro Plus. Multiple com- parisons of confounding variables were performed using the general linear model univariate analysis using SPSS v16.0 statistical software (SPSS, USA). Direct analysis of the incidence of bifurcation was performed using Pear- sons Chi-Square test (SPSS, USA). 3. RESULTS The MDD group had a significantly lower age of death as compared to controls (p = 0.038, 1-way ANOVA). The MDD group (n = 20) contained 11 confirmed cases of suicide. The other disease groups also showed instances of suicide, which may contribute toward the non-signifi- cant trend downward in age in SZ (1 suicide, n = 12) and BPD (3 suicides, n = 16). The brain tissue of the BPD group was in formalin significantly longer than the other groups (Mean fixation time: NPD 11.3 yr vs. BPD 19.7 yr, p = 0.0004; NPD vs. SZ. 11.6 yr, p = 0.074; NPD vs. RDD. 11.8 yr, p = 0.59, ANOVA). There was no effect of sex, age, PM delay, incidence of suicide, fixation time or hemisphere on the incidence of bifurcation. The incidence of bifurcation was 11/20 NPD cases (55%), 2/12 SZ cases (17%), 9/16 BPD cases (56%) and 11/20 RDD cases (55%), shown in Figure 2. The SZ group showed a significantly lower incidence of bifurcation than the controls or other diagnostic groups (p = 0.02, Pearsons Chi-Square test, SPSS v16.0). 4. DISCUSSION The results suggest that SCC bifurcation is less common in schizophrenia than in either controls, BPD or RDD. Whether this bifurcation is related to changed numbers of neuron or glial cells, or the function of the SCC, are unknown. Future neuropathological studies will be re- quired to elicit further information of the cellular changes associated with altered cortical folding. Due to the nature of neuropathological studies it is not possible to measure total SCC volume using this type of study. The cases of bipolar disorder had a longer mean PM Figure 1. Schematic illustrating the measurement of the primary subgenual cingulate sulcus depth and a bifurca- tion in the SCC in the coronal plane. Percentage incidence of bifurcation 100 50 0 NPD SZ BPD RDD Figure 2. Incidence of bifurcation of the subgenual cingulate cortex as a percentage of cases. NPD—No Psychiatric Disorder; SZ—Schizophrenia; BPD—Bipolar Disorder; RDD—Recur- rent Depressive Disorder. delay than the cases from the other diagnostic groups. This was predominantly due to three male bipolar cases, numbers 32 (89 h), 34 (91 h) and 45 (100 h). The RDD group showed a reduced age of death, which may reflect a higher number of suicides amongst this group. Simi- larly male schizophrenia cases showed a younger age of death than female schizophrenia cases which was likely related to a higher number of suicides. Additionally the BPD cohort has a longer period of fixation, due to the lower number of BPD cases in the tissue bank, requiring tissue from earlier donations to be included. However these variables had no effect on the occurrence of bifur- cation, or previous variables measured in the cingulate of these cases [21,28]. We did not have data on the illness duration. However as a requirement for inclusion was symptom onset between 20 - 30 yr this strongly corre- lated age, which had no effect on incidence of bifurca- tion. Although the measures were collected from slides within 100 μm of one another bifurcation was a gross Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  M. R. Williams et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 253-257 256 anatomical occurrence and was easily visible with the naked eye on the blocks. Ideally the full volume of the SCC could be estimated by many serial sections, but this would require many blocks along the entire structure and this amount of tissue was not available. Also there would be errors involved due to the tissue shrinkage during fixation and processing. If these technical issues could be overcome then a volumetric study would be extremely useful as the measurements could be performed with far greater accuracy than in imaging. Cortical folding changes in length and depth of tem- poral and frontal lobes have been reported in schizophre- nia [29]. These changes been shown to be present before disease onset. Patients with adolescent onset schizo- phrenia have significantly more flattened curvature in the sulci and more steeped or peaked curvature in the gyri [30], and increased cortical folding in the superior frontal cortex and in gyral and sucal folding in temporal lobe of first episode schizophrenia [31,32]. High risk individuals have been observed to have altered cortical folding in the prefrontal cortex [33]. Examination of bifurcation may give additional information of changes in the cortex in schizophrenia between the scales of neuropathological reports of cell density and morphometry and the imaging data showing larger scale trends across cortical regions. As gyral morphology is created in utero during the ini- tial folding of the cortex, this suggests that morphologi- cal changes in schizophrenia may be hardwired early in life. If these can be identified then they may help with the early identification of high-risk individuals. Whilst large-scale changes in gyral folding may only be detect- able in detailed analysis of the whole brain surface this study suggests that by looking at regions of high vulner- ability signs of this change may be measurable at the microscopic level. 5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors are grateful to Prof. Federico Turkheimer for statistical advice. This was supported by funding from the Stanley and Starr foundations, and MRC-UK PET Methodology Programme Grant G1100809/1. This project was conducted under ethical permission granted by the London south west local ethics committee reference WL/02/12 (2002), and amendment WL/02/12/AM01, granted by the Ealing and WLMHT local research ethics committee (2006). REFERENCES [1] Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D. and Damasio, A.R. (1997) Deciding advantageously before knowing the ad- vantageous strategy. Science, 275, 1269-1272. doi:10.1126/science.275.5304.1293 [2] Bush, G., Vogt, B.A., Holmes, J., Dale, A.M., Greve, D. and Rosen, L.A. (2002) Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex: A role in reward-based decision making. PNAS USA, 99, 523-528. doi:10.1073/pnas.012470999 [3] Carter, C.S., MacDonald, A.M., Botvinick, M., Ross, L.L., Stenger, V.A., Noll, D. and Cohen, J.D. (2000) Parsing exe- cutive processes: Strategic vs. evaluative functions of the anterior cingulate cortex. PNAS USA, 97, 1944-1948. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.4.1944 [4] Carter, C.S., Mintun, M., Nichols, T. and Cohen, J.D. (1997) Anterior cingulate gyrus dysfunction and selective attention deficits in schizophrenia: [15O]H2O PET study during single-trial Stroop task performance. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 1670-1675. [5] Devinsky, O., Morrell, M.J. and Vogt, B.A. (1995) Con- tributions of anterior cingulate cortex to behaviour. Brain, 118, 279-306. doi:10.1093/brain/118.1.279 [6] Kubicki, M., Westin, C.F., Nestor, P.G., Wible, C.G., Frumin, M., Maier, S.E., Kikinis, R., Jolesz, F.A., Mc- Carley, R.W. and Shenton, M.E. (2003) Cingulate fas- ciculus integrity disruption in schizophrenia: A magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging study. Biological Psy- chiatry, 54, 1171-1180. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00419-0 [7] Wang, F., Sun, Z., Cui, L., Du, X., Wang, X., Zhang, H., Cong, Z., Hong, N. and Zhang, D. (2004) Anterior cin- gulum abnormalities in male patients with schizophrenia determined through diffusion tensor imaging. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 573-575. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.573 [8] Kasparek, T., Prikryl, R., Mikl, M., Schwarz, D., Ces- kova, E. and Krupa, P. (2006) Prefrontal but not temporal grey matter changes in males with first-episode schizo- phrenia. Pro gress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Bio- logical Psychiatry, 31, 151-157. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.08.011 [9] Koo, M.S., Levitt, J.J., Salisbury, D.F., Nakamura, M., Shenton, M.E. and McCarley, R.W. (2008) A cross-sec- tional and longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study of cingulate gyrus gray matter volume abnormalities in first-episode schizophrenia and first-episode affective psy- chosis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65, 746-760. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.746 [10] Kuperberg, G.R., Broome, M.R., McGuire, P.K., David, A.S., Eddy, M., Ozawa, F., Goff, D., West, W.C., Wil- liams, S.C., van der Kouwe, A.J., Salat, D.H., Dale, A.M. and Fischl, B. (2003) Regionally localized thinning of the cerebral cortex in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 878-888. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.878 [11] Meisenzahl, E.M., Koutsouleris, N., Bottlender, R., Sche- uerecker, J., Jäger, M., Teipel, S.J., Holzinger, S., Frodl, T., Preuss, U., Schmitt, G., Burgermeister, B., Reiser, M., Born, C. and Möller, H.J. (2008) Structural brain altera- tions at different stages of schizophrenia: A voxel-based morphometric study. Schizophrenia Research, 104, 44-60. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2008.06.023 [12] Narr, K.L., Bilder, R.M., Kim, S., Thompson, P.M., Szeszko, P., Robinson, D., Luders, E. and Toga, A.W. (2004) Abnor- mal gyral complexity in first-episode schizophrenia. Bio- logical Psychiatry, 55, 859-867. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.027 [13] Fujiwara, H., Hirao, K., Namiki, C., Yamada, M., Shimizu, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  M. R. Williams et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 253-257 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 257 OPEN ACCESS M., Fukuyama, H., Hayashi, T. and Murai, T. (2007) An- terior cingulate pathology and social cognition in schi- zophrenia: A study of gray matter, white matter and sul- cal morphometry. Neuroimage, 36, 1236-1245. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.068 [14] Baiano, M., David, A., Versace, A., Churchill, R., Bales- trieri, M. and Brambilla, P. (2007) Anterior cingulate vol- umes in schizophrenia: A systematic review and a meta- analysis of MRI studies. Schizophrenia Research, 93, 1-12. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2007.02.012 [15] Bouras, C., Kovari, E., Hof, P.R., Riederer, B.M. and Gian- nakopoulos, P. (2001) Anterior cingulate cortex pathol- ogy in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Acta Neuro- pathologica, 102, 373-379. [16] Nugent, A.C., Milham, M.P., Bain, E.E., Mah, L., Can- non, D.M., Marrett, S., Zarate, C.A., Pine, D.S., Price, J.L. and Drevets, W.C. (2006) Cortical abnormalities in bipo- lar disorder investigated with MRI and voxel-based mor- phometry. Neuroimage, 30, 485-497. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.09.029 [17] Yucel, K., McKinnon, M.C., Chahal, R., Taylor, V.H., Macdonald, K., Joffe, R. and MacQueen, G.M. (2008) An- terior cingulate volumes in never-treated patients with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33, 3157-3163. doi:10.1038/npp.2008.40 [18] Frodl, T., Jäger, M., Born, C., Ritter, S., Kraft, E., Zetz- sche, T., Bottlender, R., Leinsinger, G., Reiser, M., Möl- ler, H.J. and Meisenzahl, E. (2008) Anterior cingulate cortex does not differ between patients with major de- pression and healthy controls, but relatively large anterior cingulate cortex predicts a good clinical course. Psychia- try Research, 163, 76-83. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.04.012 [19] Highley, J.R., Walker, M.A., Esiri, M.M., McDonald, B., Harrison, P.J. and Crow, T.J. (2001) Schizophrenia and the frontal lobes: Post-mortem stereological study of tis- sue volume. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 178, 337- 343. doi:10.1192/bjp.178.4.337 [20] Wright, I.C., Rabe-Hesketh, S., Woodruff, P.W., David, A.S., Murray, R.M. and Bullmore, E.T. (2000) Meta- analysis of regional brain volumes in schizophrenia. Ame- rican Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 16-25. [21] Williams, M.R., Chaudhry, R., Perera, S., Pearce, R.K.B., Hirsch, S.R., Ansorge, O., Thom, M. and Maier, M. (2012) Changes in cortical thickness in the frontal lobes in schizophrenia are a result of thinning of pyramidal cell layers. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, May 19th Epub. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22610045 [22] Heckers, S., Heinsen, H., Heinsen, Y.C. and Beckmann, H. (1990) Limbic structures and lateral ventricle in schi- zophrenia. A quantitative postmortem study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 47, 1016-1022. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810230032006 [23] Coryell, W., Nopoulos, P., Drevets, W., Wilson, T. and An- dreasen, N.C. (2005) Subgenual prefrontal cortex vol- umes in major depressive disorder and schizophrenia: Diagnostic specificity and prognostic implications. Ame- rican Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 1706-1712. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1706 [24] Zetzsche, T., Preuss, U., Frodl, T., Watz, D., Schmitt, G., Koutsouleris, N., Born, C., Reiser, M., Möller, H.J. and Meisenzahl, E.M. (2007) In-vivo topography of structural alterations of the anterior cingulate in patients with schi- zophrenia: New findings and comparison with the litera- ture. Schizophrenia Research, 96, 34-45. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2007.07.027 [25] Fujiwara, H., Namiki, C., Hirao, K., Miyata, J., Shimizu, M., Fukuyama, H., Sawamoto, N., Hayashi, T. and Murai, T. (2007) Anterior and posterior cingulum abnormalities and their association with psychopathology in schizo- phrenia: A diffusion tensor imaging study. Schizophrenia Research, 95, 215-222. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2007.05.044 [26] Sun, Z., Wang, F., Cui, L., Breeze, J., Du, X., Wang, X., Cong, Z., Zhang, H., Li, B., Hong, N. and Zhang, D. (2003) Abnormal anterior cingulum in patients with schi- zophrenia: A diffusion tensor imaging study. Neuroreport, 14, 1833-1836. doi:10.1097/00001756-200310060-00015 [27] Kasper, B.S., Taylor, D.C., Janz, D., Kasper, E.M., Maier, M., Williams, M.R. and Crow, T.J. (2010) Neuropathol- ogy of epilepsy and psychosis: The contributions of J. A. N. Corsellis. Brain, 133, 3795-3805. doi:10.1093/brain/awq235 [28] Williams, M.R., Hampton, T., Pearce, R.K.B., Hirsch, S.R., Ansorge, O., Thom, M. and Maier, M. (2012) As- trocyte decrease in the subgenual cingulate and callosal genu in schizophrenia. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, June 4th Epub. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22660922 [29] Narr, K.L., Thompson, P.M., Sharma, T., Moussai, J., Zoulman, C., Rayman, J. and Toga, A.W. (2001) Three- dimensional mapping of gyral shape and cortical surface asymmetries in Schizophrenia: Gender Effects. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 244-255. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.244 [30] White, T., Andreasen, N.C., Nopoulos, P. and Magnotta, V. (2003) Gyrification abnormalities in childhood- and adolescent-onset schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry, 54, 418-426. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00065-9 [31] Narr, K.L., Toga, A.W., Szeszko, P., Thompson, P.M., Woods, R.P., Robinson, D., Sevy, S., Wang, Y., Schrock, K. and Bilder, R.M. (2005) Cortical thinning in cingulate and occipital cortices in first episode schizophrenia. Bio- logical Psychiatry, 58, 32-40. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.043 [32] Harris, J.M., Yates, S., Miller, P., Best, J.J., Johnstone, E.C. and Lawrie, S.M. (2004) Gyrification in first-epi- sode schizophrenia: A morphometric study. Biological Psy- chiatry, 55, 141-147. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00789-3 [33] Harris, J.M., Whalley, H., Yates, S., Miller, P., Johnstone, E.C. and Lawrie, S.M. (2004) Abnormal cortical folding in high-risk individuals: A predictor of the development of schizophrenia? Biological Ps ychiatry, 56, 182-189. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.04.007

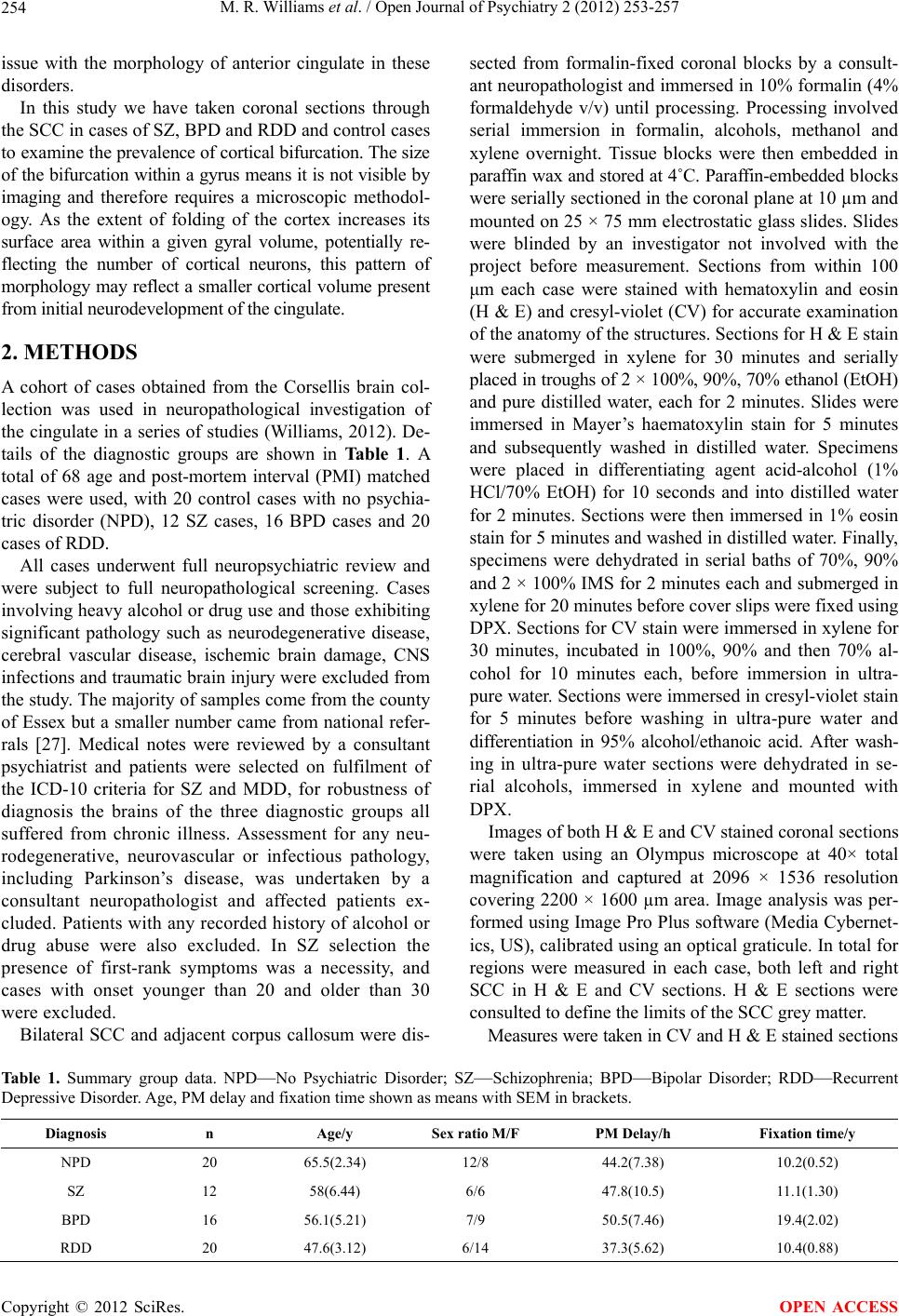

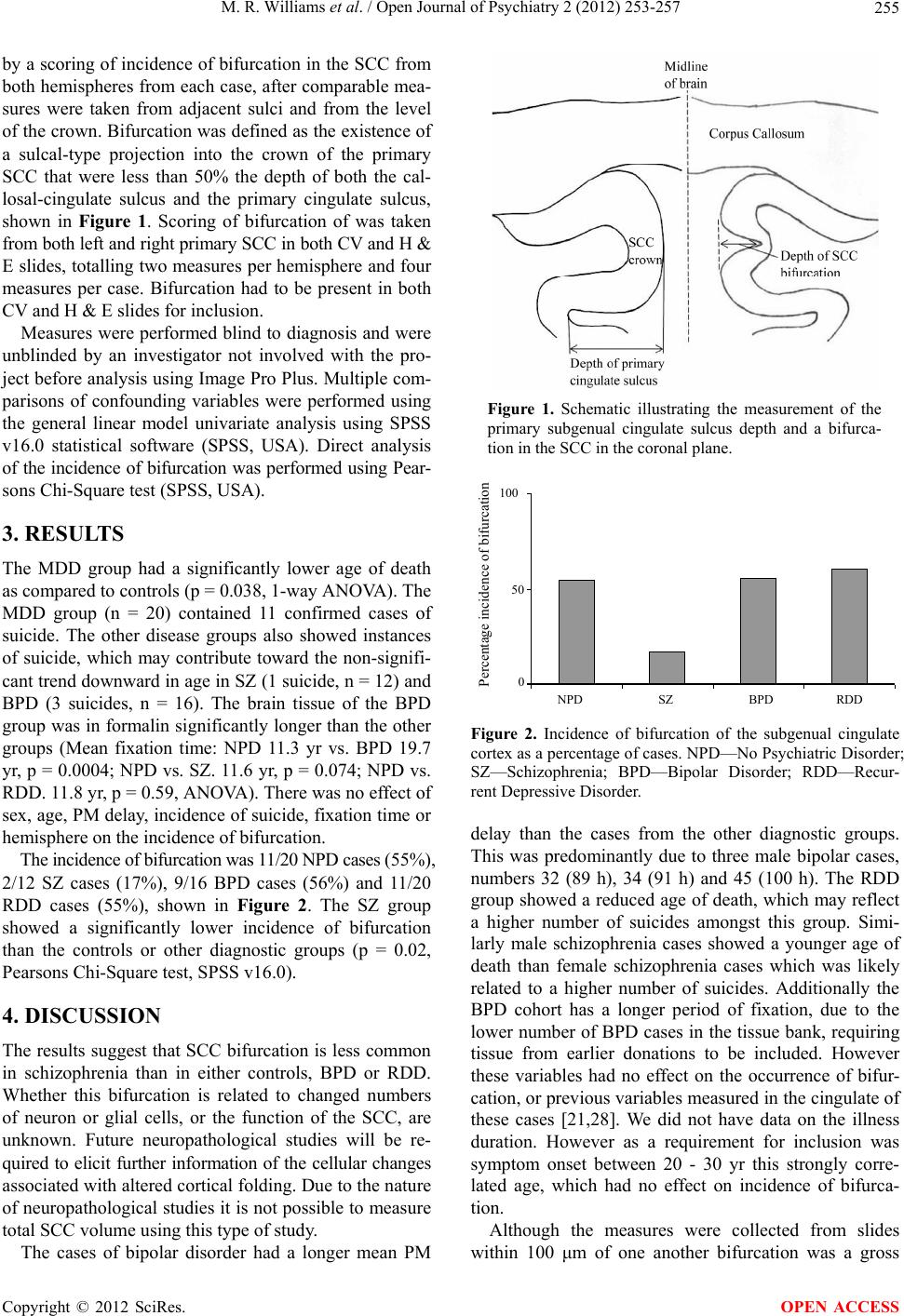

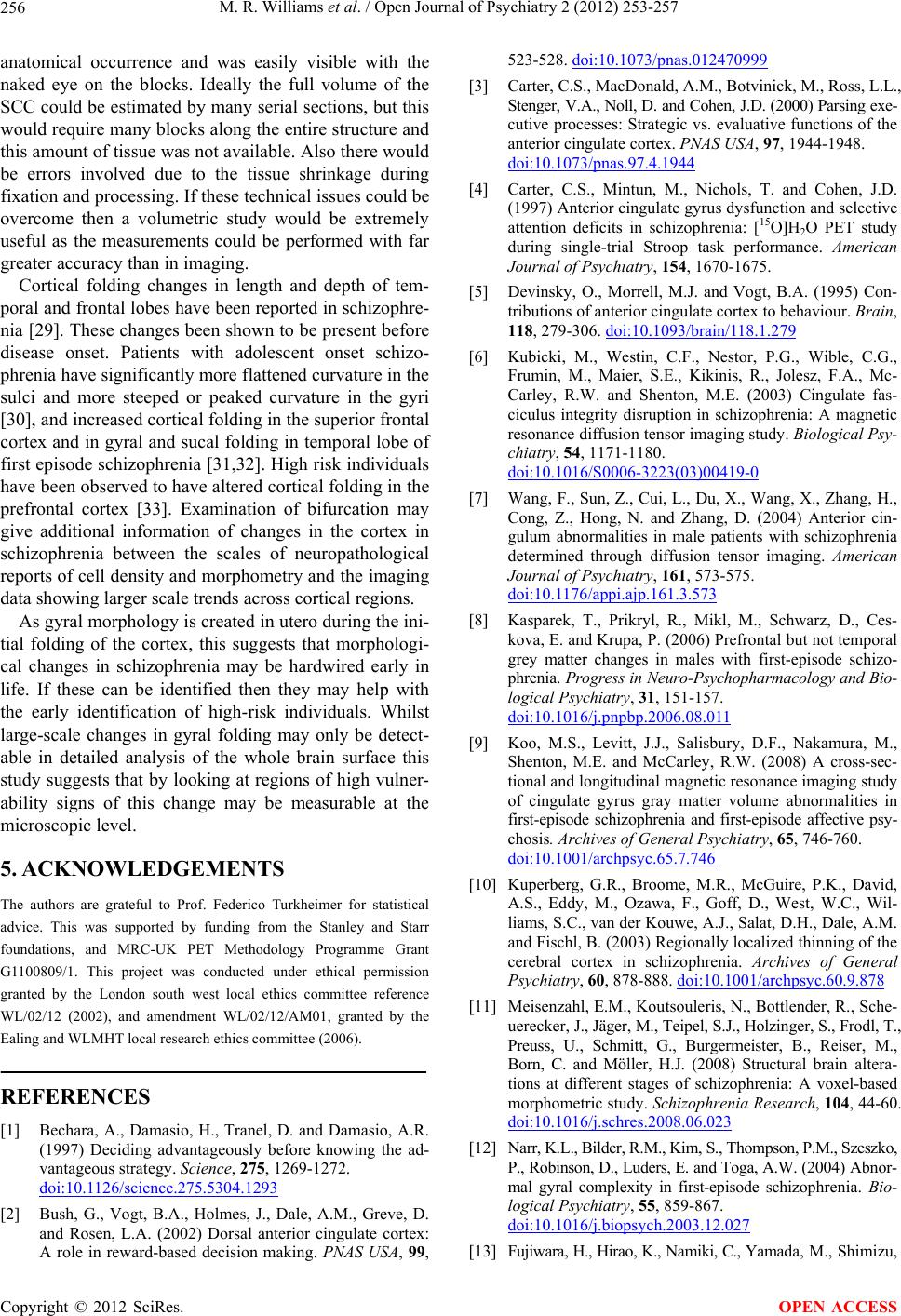

|