Open Journal of Forestry 2012. Vol.2, No.4, 240-251 Published Online October 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojf) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojf.2012.24030 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 240 Power, the Hidden Factor in Development Cooperation. An Example of Community Forestry in Cameroon Mbolo C. Yufanyi Movuh, Carsten Schusser Forest and Nature Conservation Policy, Georg August University Goettingen, Goettingen, Germany Email: cyufani@gwdg.de Received July 23rd, 2012; Revised August 26th, 2012; Accepted September 15th, 2012 This paper is concomitant with our comparative study analysis of the interests and power of the stake- holders involved in Community Forestry (CF) in six countries. The study hypothesises that, “governance processes and outcomes in CF depend mostly on interests of the powerful external stakeholders”. For this paper which is on CF in Cameroon, the study hypothesizes that, “Power is a hidden factor in Develop- ment cooperation”. Based on political theories, the paper uses the “actor-centered power” (ACP) concept of the Community Forestry Working Group (CFWG) in Göttingen, Germany, the post-development the- ory and empirical findings, to back up the assertations made in the study through the analysis of thirteen different CFs in the South West region (SWR) of Cameroon. It analyzes the empirically applicable ACP concept, that consists of three elements: trust, incentives and coercion and at the same time connects these elements with the post-development theory. The elements were derived from the basic assumptions on power made by Max Weber in political sciences and Max Krott in forest policy. The study confirms the existence of powerful internal and external stakeholders that influence CF in Cameroon and aims to em- power important but marginalised communities. It concludes that, CF as a development instrument to al- leviate poverty and increase livelihood while sustainably managing the forest has actually not brought significant or meaningful development to the targeted sector of the society. Keywords: Community Forestry; Devolution; Power; Development; Post-Development; Theory; Trust; Incentive; Coercion Introduction As community forestry (CF) is being recognized as a para- digm shift (La Viña, 1997; Rebugio, 1998; Devkota, 2010) of forest policy in the so-called developing countries,1 it is essen- tial to understand the power processes and its distribution be- hind it. This makes it easier to understand the way power is wielded among stakeholders (Devkota, 2010: p. 6), hence, identifying the different interests and influence. Furthermore, many global funding agencies have bought into the idea of CF and feel that it is a far more ethical way of donating money for the protection of forest and at the same time fulfilling their development agenda. Millions of Euros are being invested in CF programs all over the world with very little success in their implementation, management and monitoring, not achieving the goals of biodiversity protection and increased human well- being as always proclaimed in discourse and rhetoric, in the name of Development. In Cameroon for instance, most of the community forests were established through projects imple- mented by NGOs and drawing on donor support (Mandondo, 2003: p. 17). In implementing CF, the forest condition (sustainable man- agement) is often referred to as a precondition for positive so- cial and economic outcomes. Nonetheless, in many cases, for- ests are devolved to local arenas after they have been severely exploited and are in a degraded condition (Mandondo, 2003: p. 15), while states appear to have initiated the devolution concept to restore degraded forest lands by taking advantage of cheap and voluntary labour (Shackleton et al., 2002; Sarin et al., 2003; Colfer, 2005; Larson, 2005; Contreras, 2003; Edmunds & Wol- lenberg, 2001; Thoms, 2006; Devkota, 2010). Furthermore, in the devolution of some usufruct and to a limited extend partici- pation rights to local communities, institutional arrangements had not been followed by the establishment of more effective institutions (Poffenberger, 2006; Yufanyi Movuh & Krott, 2011). Larson (2005) and Devkota (2010) mention that at times after locals have invested in the protection of these resources and improved their status, the state often re-appropriates these forest resources. For Larson and Ribot (2007: p. 3), forest pol- icy and the implementation “—systematically exclude various groups from forest benefits—and often impoverish and main- tain the poverty of these groups”. Also, the concept of CF in Cameroon has been attributed to colonial heritage and post- colonial entanglement to the former colonial masters (Yufanyi Movuh & Krott, 2011: p. 77), with power and interests of sta- keholders being seen to influence outcomes of CF. With such critical findings, it is but adequate to question the concept of CF (as a pro community policy implementation instrument) and further examine the factors contributing to it not achieving its proclaimed objectives (Devkota, 2010: p. 2). Most often than not, power comes in many forms and is concealed where it is strongest and therefore resists scientific analyses (Krott, 2005: p. 14). Consequently, CF analysis through 1This is regarded as a new forestry paradigm favouring a people-oriented approach generally termed “community forestry” or “participatory for- estry,” rather than the previous top-down forest policies of these countries.  M. C. YUFANYI MOVUH, C. SCHUSSER the power spectrum require a logically and theoretically based concept of power based on social relationships. As an important phenomenon in social relation, power analysis is very necessary in forest policy as well as in other domains. By referring to the classic sociological definition of power by Max Weber (1947: p. 152), Krott (2005: p. 14) relates the issue in forest policy as, “those who utilize or protect forests are forced to subordinate their interests to politically determined programs in the face of conflict”. This, he explains, results from “stakeholders and political players availing themselves of power” (Krott, 2005: p. 14; Devkota, 2010: p. 6), leading to criticism of development as a whole and the CF programs in particular. In criticizing the development theory as a whole2, I chose CF as a case study and show how power and the interest, characteristics and circum- stances (Mayers, 2005) of the powerful stakeholders are exhib- ited in the era of post-development theory. This could be well ostracised in a situation where conservationism, sustainable and participatory forest management for economic benefits are notably tied with the politics of funding, conditioned upon the adoption and mainstreaming of such viewpoints in national policy arenas (Mandondo, 2003: p. 23). The study also sheds light on how and why countries with rich forests, especially African countries like Cameroon, are generally marginalized in international forestry think-tank, decision-making and trend- setting institutions3. The main hypothesis of the interest and power analysis is that, “governance processes and outcomes in CF depend mostly on interests of the powerful external stakeholders”. To test the hypothesis, a comparative research study was carried out on “Stakeholders” Interests and Power as Drivers of Community Forestry”. The comparative research project is conducted in Albania, Cameroon, Germany, Indonesia, Namibia and Nepal, in three different continents. Pertaining to CF in Cameroon, the study hypothesizes that, “Power is a hidden factor in develop- ment assistance”. It uses a simple concept of power suggested by the Community Forestry Working Group (CFWG), the post-development theory and empirical findings, to back up the assertations made in the study, and is strictly reduced to the basics of social interaction. This approach helps understanding the present CF model in Cameroon, by identifying the key ac- tors or stakeholders in the system, and assessing their respective interests in, or influence on, that system (Mayers, 2005: p. 3). CF and its Rationale in Cameroon In the last 3 decades, CF4 has been hailed by researchers, policy makers, governments and Organisations alike (Brown et al., 2007: p. 136; Pulhin & Dressler, 2009) as a successful con- temporary paradigm and implementation mechanism for sus- tainable forest resources management, decentralization and devolution (Ezzine de Blas et al., 2009; Larson & Ribot, 2004; World Bank, 2004; World Bank, 2005; WRI, 2005). Based on its theoretical decentralization and devolution characteristics, it has been promoted by international bi- and multilateral green Organizations, development agencies (Agrawal & Redford, 2006) and western governments, becoming one of the most practiced participatory models5 of forest management as an alternative to previous models (Barry et al., 2003; Sikor, 2006: p. 339), promising and aiming at alleviating poverty of many forest dependent communities while at the same time sustaina- bly managing their forest (Maryudi et al., 2011; Yufanyi Movuh & Krott, 2011; Maryudi, 2011). But the common reality across the globe and Cameroon in particular is that, the governance process of CF has not yet produced expected outcomes (Yufanyi Movuh & Krott, 2011; MINEP, 2004; Devkota, 2010). While McDermott and Schrec- kenberg (2009: p. 158) have elaborated CF as the exercise by local people of power to influence decisions regarding man- agement of forests, including the rules of access and the dispo- sition of products; in Cameroon, the “power shift” rhetoric from the state to the local communities through CF opens a question of power sharing, when these management objectives would really be put into practice. In Cameroon since 1995, a new for- est policy act was enacted (proclaimed in 1994) to accommo- date two approaches: CF and sustainable forest management. Conserving and enhancing biodiversity through rural peoples’ involvement was one of the components of the new forest pol- icy act of 1995 (Sobze, 2003; Yufanyi Movuh, 2007: p. 1). This law lays emphasis on increasing the participation of the local populations in forest conservation and management in order to contribute to raising their living standards6. For the first time in Cameroon’s history, the 1994 forest law and its 1995 decrees of application, provided for a legal instrument for community involvement in forest management (Yufanyi Movuh & Krott, 2011; Oyono, 2005a, 2005b; Mandondo, 2003). Although the implementation of CF differs in different coun- tries7, its concept and formulation goes far back to colonial times (Larson & Ribot, 2007; Oyono, 2004b). Presently, it is being incentivised with development assistance in many, if not all of these formerly colonised countries, from a variety of dif- ferent western or western-backed agencies and organisations, like the World Bank, KfW (German development bank) and GIZ for Cameroon8. After more than 14 years of CF imple- mentation with financial support from international donors, the central government of Cameroon is gaining more control and influence of the forest resources than before, strengthening the top-down approach of forest policy implementation with strong tendencies towards re-centralization, dictated by the practices of bureaucrats and state representatives (Oyono, 2004b), con- trary to the CF aim. This confirms the growing concerns that CF practice in many regions of the world is not attaining its intended objectives (Yufanyi Movuh & Krott, 2011; Oyono, 5Although “Traditional Community Forestry” models have existed long in the local communities before the present introduced models by Western GOs and agencies (Yufanyi Movuh & Krott, 2011; Larson & Ribot, 2007; Sunderlin, 2004: 3; Oyono, 2005b). 6The Forestry Law No 94/01 of 20th January 1994 and its decrees of appli- cation No 95/531/PM du 23 August 1995. 7Cameroon forestry law definition of community forestry: A community forest is “a forest forming part of the non- ermanent forest estate, which is covered by a management agreement between a village community and the Forestry Administration. Management of such forest—which should not exceed 5000 ha—is the responsibility of the village community concerned, with the help or technical assistance of the Forestry Administration.” Source: Article 3(11) of Decree 95/531/PM of 23 August 1995. 8GTZ (German technical service) and DED (German development service) have now merged with InWEnt, to be called GIZ (German Organisation fo international cooperation). 2Development theory is a combination of theories about how desirable change in the so-called third world societies can be best obtained, by fol- lowing the examples of the development processes of the so-called first world societies. These theories are based on a variety of social scientific disciplines and approaches. 3ibid. 4We define “Community Forestry” as “forestry which directly involves local forest users in the common decision making and implementation o forestry activities” (CFWG in Göttingen). Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 241  M. C. YUFANYI MOVUH, C. SCHUSSER 2004b). In Cameroon, CF has been proven to be a leverage for colonial legacy and entanglement (Yufanyi Movuh & Krott, 2011) and an instrument of power against a backdrop of devel- opment assistance reminiscent to colonial times. Just like the 1974 land tenure law that followed the French colonial concep- tion and which is still in place today in Cameroon9, the 1994 forestry law reinforced the colonial conception of the state as the ultimate owner of the national forest domain although it established for the first time in Cameroon the possibility for rural people to gain usufruct rights in the exploitation of forest resources in their neighbourhood. Before, but especially since the inception of a different ap- proach in forest policy in Cameroon through the new forestry law, European development agencies like GTZ, DED (now GIZ), KfW, AFD, (Agence Française de Développement), SNV, etc. have become more influential than ever in controlling the policies of natural resource management in Cameroon. They have become a sine qua non for the formulation and imple- mentation of CF in tandem with their political ideologies of westernisation (Oyono et al., 2005: p. 364; Mbile et al., 2009; Oyono, 2009; Yufanyi Movuh & Krott, 2011). Also, in the last 3 decades, we have experienced a wave of criticism of the un- critical acceptance of development in the form of post-modern critiques against western development schemas (Ahorro n.p.; Matthews, 2004, 2006). These criticisms have been literally boosted or elaborated by contemporary theories like the post- colonial and post-development theories. This paper will proceed by analysing the CF stakeholders’ power network in Cameroon using conceptualisation, theory and empirical data from the research collected from field work in Cameroon. Materials and Methods The CFWG10 definition of CF, includes community based natural resource management through programs emphasizing biodiversity conservation and sustainable forest management involving the local communities. Here, the practice of Council forestry in Cameroon is included as part of the CF. Thirteen communities (see Figure 1, map) were explored in the South West Region (SWR) of Cameroon and the history, status and stakeholders of the CFs were analyzed11. Stakeholders here, refer to those who have interests in and the potential to influ- ence the CF processes. We classify them into two main groups: state and non-state stakeholders. The main state stakeholders relevant for CF are the central Ministry for Forestry and Wild- life (MINFOF) and the regional and local forest administrations. The non-state stakeholders include forest users, forest users’ groups and their federations; donors, forest-based enterprises; environmental and user associations and political parties; uni- versity and research institutions; media and consultants. Such stakeholders may belong to local/regional, national and interna- tional levels, all of which may be of worth in CF processes. For Cameroon and for this study, our identified non-state stake- holders are: GTZ, DED (now GIZ), KfW/GFA, WWF, WCS12, the Common Initiative Groups (CIG) and Village Forest Man- agement Committees (VFMC) of the different communities with community and council forests respectively. Quantitative and qualitative interviews were carried out with CF managers and forestry officers and at times with members of the CIG and VFMC, responsible for the management of these forests; with representatives of MINFOF-SWR, KfW/ GFA representing the main Program (PSMNR-SWR)13, for the facilitation of the implementation of the forestry law, hence CF. Structured questionnaires were used with closed and opened- ended questions. More than seventy interviews were conducted and observations noted, in the course of the research that lasted three years. Documents like the logframe (logical framework) of the PSMNR-SWR, Management Plans (MP) and Technical Notes (NT) of the CFs were also part of the materials collected and analyzed. The selections of the community and council forestry sam- ples were done the map of the PSMNR-SWR (Figure 1) and based on information on recent activities of the communities in the CF process. It is also an area where the researcher has a good existing knowledge. From this population, a simple ran- dom selection was made. Interviews carried out with different stakeholders were in relation to the information given by other stakeholders in their networking (Schnell et al., 2005) and in- terest representation in CF14. All the interviews were recorded for transcription and further analyses. The quantitative network analysis uses the knowledge of the stakeholders to identify the partners of the network while the qualitative analysis goes deeper to describe and evaluate the powerful stakeholders, identified through the quantitative network analysis(see Schu- sser et al., 2012: p. 6). More the qualitative and less the quanti- tative analysis will be used to test our actor-centered power (ACP) and post-development theories through the concept and practice of CF in Cameroon. In employing a critical realistic sequence of quantitative and qualitative research design approach, Schusser et al. (2012) identify stakeholders and their respective influence, providing explanations of activities and power in CF settings. 9In the colonial times, lands were considered “vacant” and without “master” and as such defined as state land. 10The Community Forestry Working Group (CFWG) in Germany, within the Chair for Forest and Nature Conservation Policy of the University in Goettingen. 11The statistical population of the CFs was drawn from the number o Community and Council forest applications received by the Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife (MINFOF) until 2009 in Yaoundé-Cameroon as a whole. This sums up to 451 Community forest and 28 Council Forest applications with a total of 479 CFs, spread out in all the ten Regions of Cameroon. 12MINFOF (national and Regional-SWR), GTZ, DED (now GIZ), KfW/GFA, WWF , WCS are all representing the main Program, PSMNR-SWR. 13Program for the Sustainable Management of Natural Resources in the South West Region. 14This was done through the snowball method. It is a typical way to analyse networks. Definitions and Theoretical Roots Actor-Centered Power (ACP) Despite being the crucial question of political science, the concept of power played an increasingly minor role in the last decades’ forest policy analysis. All the credit for the reintro- duction of a power concept is due to Bas Arts and Jan van Tatenhove who published a conceptual framework on power in 2004 (Schusser, 2012: p. 2; Krott et al., in review). Although we think that powerful actors influence the policy outcomes heavily, we still need to understand the social phenomenon called “power” in the given context of forest policy issues.15 Many political scientists including Weber offered explanations and 15ibid. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 242  M. C. YUFANYI MOVUH, C. SCHUSSER Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 243 Source PSMNR 2010 Figure 1. Community and Council Forestry regions in the PSMNR-SWR: Areas visited are encircled.  M. C. YUFANYI MOVUH, C. SCHUSSER definitions of power but there has been little reference directly linking forest policy analysis and development. To analyze power in forest policy analysis, we need to focus on single ac- tors and their interaction in detail and therefore, the theory should focus on that substance of social behaviour. This paper aims to analyze the empirically applicable con- cept of an ACP that consists of the following power sources (see Box 1): Trust, Incentives and Coercion and at the same- time connect these elements with the post-development theory. The elements were derived from basic assumptions on power made by Weber (1947) and Krott (1990). The elements are clearly defined and described with instruments and empirical findings. To analyze the social relations of forest policy actors in Cameroon, a simple concept that is strictly reduced to the basics of social interaction was suggested. For clarity’s sake, in this text an actor exercising power is called A and an actor re- ceiving power B. Our ACP concept defines power as follows: Power is a social relationship, where an actor A alternates the behavior of actor B without recognizing B’s will. For Weber (1947: p. 152), power is, “the probability that one actor within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will despite resistance, regardless of the basis on which this probability rests”. That is, the chance of a person or of a number of persons to realize their own will in a communal action even against the resistance of others who are participat- ing in the action (Schusser, 2012: p. 2; Krott et al., in review). Note Power can only be verified at the presence of resistance and the use of coercionto break thisresistance (Weber,1972). But even Weber mentionedthe possibility to exercise power as an equivalent to power, with thehelp of the threat of power. This behavioral conceptof power has some inherent weaknesses, as Offe points out: Here, influence cannot be verified. The better power ‘works’ineveryday life as hestates, thefewer powerwould be verifiable (Offe, 1977). Etzioni(1975:333) proposes toexaminethe actor’sresources and instruments. Historicexperiences of a useof these resources andinstruments would allowfor a foresight.B could estimate,on what the threatis basedon. Thus, power potential becomes verifiable beyond its simple exercise which was first mentioned byKrott (1990). On the otherhand, power can be verified also on the behavior of "B". His change in behavior can be verified empirically at his deciding orfailing to decide and the informationhepossesses(Simon,1981). Box 1. ACP concept consists of three elements: Trust, Incentives, and Coer- cion. We define trust as a power element when one stakeholder B, changes behaviour by accepting for example, stakeholder A’s information without check. A might typically achieve this situation by persuasion, prestige and reputation or by with- holding information from B. Trust can be assumed through furnishing or provision of information, checks or a high fre- quency of interaction with a stakeholder. It is B’s confidence to A’s goodwill that makes B behave accordingly. It happens when B has the reasonable expectation that following the guid- ance of A will be beneficial. The second element, incentives, are financial or non-finan- cial factors that alters B’s behaviour by motivation from A, 16 which is most likely to be done by money, luxuries or any other kind of benefit. Here, transfers are likely to occur. In this case, it exists for B when B delegates to A control over good C in which B has an interest. To B, a behaviour according to A’s incentives produces more benefits than a pursuit of A’s former strategy to fulfil B’s objectives. It is important to note, that B’s inherent interests stay the same—just the behaviour changes. And this change was triggered by the benefits. The third element, coercion, on the other hand is the practice of A forcing B to behave in an involuntary manner which can be done by violence or threat of violence. Coercion is force and control. If one cannot control other stakeholders, then there is a coercion problem or there is no coercion. Coercion can go with threat or action as a means of control. It is the application of pressure and that is why it is a top-down approach. As coercion builds resentment and resistance from B, it tends to be the most obvious but least effective form of power because it demands a lot of control. When coercion comes to play, B can do little or nothing about it. Although at times the complex theoretical analysis of the APC only generates face validity and lacks content validity (i.e., not being able to analyze a meaningful range of power) we are going to contentiously and empirically analyse it, pertaining to CF as a development tool in Cameroon. In the last three decades, critical political and social scientists alike have grown interest in analysing the global society, espe- cially areas of the world with weak economies that strive for better social and economic developments. They use critical theories to deconstruct the Development Theory that emerged in the period after World War II (late 1940s). These researchers and theorists have been interested in the role of development in poverty alleviation and stability, in the social systems where development has become the status quo and the notion of pov- erty alleviation obsolete. This interest has grown significantly since the early 1980s, from works of scholars like Sachs ed. (1992), Escobar (1995) and Rahnema & Bawtree (1997), in the field of post-structuralism and post-development. This has been characterized by the continuing changes in the society, trig- gered by the unsatisfactory manifestation of the power relations between stakeholders of development. On the other hand, less has been invested in the role of power in the development and poverty alleviation process of the concerned societies. It is also the objective of this paper to use the post-development theory to explain this role. Post-Development Theory and the Policy Discourse Post-development theory argues that the whole concept of 16As far as technical support changes the behaviour of B (through motiva- tion) it is part of a power process. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 244  M. C. YUFANYI MOVUH, C. SCHUSSER development and practice is influence by Western-Northern hegemonies, with blueprints of their values over the rest of the world. Its theorists call for the rejection of the development concept (Rahnema & Bawtree, 1997; Sachs Ed., 1992; Escobar, 1995), looking beyond it. It began during the 1980s following criticisms of development projects and the development theory justifying them (Matthews, 2004). It hitherto ostracises devel- opment as a tool used by western societies in the post-world war II era, to define development concerns, dominating the power relations arena, with the interests of the so-called devel- opment experts (the World Bank, IMF and other western de- velopment agencies) defining the development priorities, ex- cluding the voices of the people they are supposed to develop, with intrinsically negative consequences. The post-development theory argue that to attempt to overcome this inequality and negative consequences, the stage should be taken over by non-western, non-northern peoples, to represent their priorities and concerns. It differs from other critical approaches to de- velopment (like dependency theory, alternative development theory and human development) in that it hitherto rejects de- velopment in its present form and calls for an alternative to development (Sachs ed., 1992; Escobar, 1995; Rahnema, 1997; Matthews, 2004, 2006), thus, moving beyond development. Post-development theorists do not reject development17 per se but the development that has been a response to the prob- lematization of poverty that occurred in the years following World War II (Klipper, 2010; Matthews, 2004), and label this type of development as being “an historical construct that pro- vides a space in which poor countries are known, specified and intervened upon” (Escobar, 1995: p. 45). Hobley (2007: p. 4) rhetorically asks, “why, if this was so clearly the case thirty years ago, we are still repeating the same mistakes with the same consequences”, echoing poverty alleviation also as being a rationale for the international funding of CF. Foucault de- scribed this as a form of power which, “makes individuals sub- jects; categorises the individual, marks him by his own indi- viduality, attaches him to his own identity, imposes a law of truth on him which he must recognise and which others have to recognise in him” (Foucault, 1983: p. 212), with individual and collective effects. With its roots in post-modern critiques of modernity, one of the main arguments by theorists of post- development against development practices is the well-estab- lished modernist powerful economic, socio-political and eco- logical interests in the pursuit of development. By deconstruct- ing the development practice and theory, they reveal the opera- tions of power and knowledge in development discourse and practices (Kippler, 2010: p. 2). Why the Analysis of ACP and Post-Development in CF Power, although being a core element of social and political sciences, has nevertheless played a less important role in forest policy (Krott et al., in review) and post-development theory analysis. It is understood from many scholars in the field of post-structuralism and post-development studies (Sachs, 1992; Rahnema & Bawtree, 1997; Little & Painter, 1995; Berger, 1995; Escobar, 1995; Crew & Harrison, 1998; Pieterse, 1998; Blaike, 1998; Kiely, 1999; Storey, 2000; Babbington, 2000) that power is neglected in the post-developmentists’ decon- struction of development. Escobar (2000) points out that it might even be suggested that post-development theorists do not understand power since power lies in the material and with the people, not in discourse, stressing livelihood and people’s needs and not theoretical analyses to be of more importance. On the other hand, Rossi (2004: p. 2) argues that, “discourse is a form of power, producing reality, domains of objects and rituals of truth”. We argue that it is not the one or the other. We believe that using the power processes in our concept, we can easily deci- pher and confirm the arguments of the post-development theo- rists in analyzing our hypothesis that power is a hidden factor in development assistance. And because it is hidden and resists scientific analysis, it plays a major role (Offe, 1977; Krott, 2005: p. 14). Furthermore, we do not want to assume that the contact with development and the commodity is to be inter- preted as a desire for development and the commodity on the part of those affected, arguing that such contacts are made pos- sible through the enactment of a cultural politics by develop- ment advocates, in which development and the commodity are prioritized and bestowed upon the subaltern (Escobar, 2000). The only way to explain this is by analyzing the visible and invisible power processes behind these political enactments upon subaltern groups. They willingly or otherwise become actors of a cultural if not hegemonial politics bestowed on them as they struggle to defend their places, existence, ecologies, and cultures. Until recently, only a few African scholars have had some- thing to say about post-development theory although it goes without doubt that the critique of development offered by post-development theory is very important to Africa18. Rela- tively little attempt has been made to relate the post-develop- ment perspective to the continent (Matthews, 2004: p. 374). The fusion of theory with empirical case studies gives the pos- sibility for a better understanding of both our ACP concept and the post-development theory, countering the criticism of post-development theory as being able to offer a critique of development but lacking instrumentality in relation to practice (Kippler, 2010), the same critique that is levied on many theo- ries on power. As Matthews (2004: p. 377) explains further, even those few African scholars who have published work on development, have not taken into account the post-development perspective, be it from anything similar to a post-development perspective or discussions and literature focusing on the ques- tion of development in Africa. The present CF model in Cam- eroon is a practical example in natural resource management where powerful international actors propose, formulate, impose and implement forest policies through development aid or as- sistance. Larson and Ribot (2007: p. 190) point out that forest policy and the implementation―“systematically exclude vari- ous groups from forest benefits―and often impoverish and maintain the poverty of these groups”. Eighteen years after the new forestry law in Cameroon was proclaimed, the present CF model is still to achieve its objective of sustainable forest man- agement and poverty alleviation through the communities by acquiring benefits from CF. Result Evaluation o f Pow er in C om m unity Forestry In all thirteen CFs visited between 2009 and 2011, ten CFs 18it recognises the failure of the post-World War II (also post-colonial) development project which is illustrated by the African experience. 17Development being an improvement or progress in life standards in time. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 245  M. C. YUFANYI MOVUH, C. SCHUSSER had some form of regulated activities perceived to conform with the definition of our CFWG and also MINFOF classifica- tion as a CF. Table 1 shows the different cases of CF analysed, indicating the presence or not, of donor involvement in the form of development assistance to the GoC through MINFOF and the PSMNR-SWR to the CF. Empirical Finding—Resources Through our critical realistic sequence of quantitative and qualitative research design approach (Schusser et al., 2012), two stakeholder blocks were identified from the state and non-state groups as being the most influential. MINFOF [state] and the GDC,19 German Development Cooperation [non-state] were identified as being more powerful than others in all the cases studied, determining most of the outcomes of CF in the region. This is the reason why they are always mentioned in the empirical findings. In 2004, a financial agreement (themed: German Financial Cooperation with Cameroon; Program for the Sustainable Man- agement of Natural Resources in Cameroon South West Region) was signed between the GoC (represented by MINEFI—Min- istry of Economy and Finance, MINFOF and the Autonomous Sinking Fund) and the government of the federal republic of Germany (represent by KfW, GTZ and DED). This financial agreement was a form of development aid from Germany to Cameroon to assist in the sustainable management of the natu- ral resources of the SWR through the PSMNR-SWR and con- tinues until date. In the same year, the sum of seven million EURO under the supervision of the Federal Ministry for Eco- nomic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), with document No.: 2004 65 252, was disbursed after a separate Agreement (by all actors concerned) to the financing Agreement dated December 29, 2004 was signed. Since then, the promotion and support of CF to enhance community participation was a main objective in the PSMNR, against the backdrop of sustainable forest management and poverty alleviation. Notwithstanding this flow of financial, technical and material assistance in CF, results gathered from the field research show less progress in CF being an income generator for the local community who are custodians of the forest. CF, which was supposed to be a form of decentralization of forest resource management and a form of devolution of power to the local communities has instead strengthen the grip of cen- tral MINFOF over the communities with CF. Furthermore, the dependency of the GoC (MINFOF) on financial assistance from Germany and other western countries to run the PSMNR has also increased the influence of these actors over policy and implementation of CF. Without these funds, activities in CF will be almost impossible since certain technical documents and related services have to be paid for by communities who are themselves financially not viable. Empirically, the three ele- ments of power are used to confirm the existence and strong influence of powerful international actors in CF. These ele- ments also confirm the arguments of the post-development theorists, that development, in this case through CF in Camer- oon should be rejected since it is a project premised upon a set of values that are not found or regarded strange in the society in which it is implemented and in the long run cannot succeed and will be reason for its demise. The Power Element Trust Trust as defined in the ACP concept is where an actor B complies without a check of information given by another actor A. As Fisher et al. (2010) put it, trust arises from a judgement of whether to place oneself in a position of potential vulnerabil- ity by granting others discretionary power over one’s interests. At a certain stage, A is trustworthy just to the extent that he attends to B’s interests, values, and collective identities. Seen from B’s point of view, trust suspends the need of control over A (Möllerring, 2005: p. 299). CF in Cameroon came with the objective of enhanced par- ticipation of the communities concerned in managing their for- est resources sustainably and at the same time benefit finan- cially from it, hence, attaining a progressive development. But in most cases that concerns trust in the powerful actors that govern CF (be it to MINFOF or international organisations), a thorough check by the local stakeholders concerned is just too complex, time-consuming and expensive and therefore ineffi- cient for them, so they rely on the unchecked information given to them by the powerful actors. In all the case studies mentioned in Table 1, it was observed that trust was granted to MINFOF and the international organi- sations representing the GDC. While the local actors like the CIGs and VFMCs trust MINFOF and the other government ministries concerned with CF, when they comply without any check of alternatives, MINFOF also trusts the GDC by accept- ing the conditions in the way the PSMNR is going to be man- aged, also without any check of alternatives. It could be ob- served in the field that staff of the GDC were very much trusted by the MINFOF staff without check of Information. It could also be observed that the CIGs, VFMCs and MINFOF respec- tively do not check or are not able to check information from the GDC but use it as a basis for orientation. If they would have the means to check or double-check the information and would hence be able to agree to it voluntarily, there would no power process because here, both parties would have the same inter- ests, but this is not the case. Also, in the past, the GDC has always been supporting as a development goal, the green sector in Cameroon and this is also a reason for trust without checks. In the above mentioned 2004 separate (bilateral) contract between the German Cooperation and the GoC, the GoC accepted the GFA/DFS20, (a decision from KfW) without checking, as the main consultancy partner to manage the PSMNR-SWR with MINFOF. Here, the accep- tance of MINFOF could be interpreted as change of behaviour due to motivations from the GDC but this could not be con- firmed in the research. Officially, the GFA and DFS were se- lected as program consultants (supposedly through an interna- tional bidding process) to assist the program implementation agency, MINFOF, in the coordination of the PSMNR-SWR. However unofficially, they act as a watchdog to MINFOF and monitor the interests of the KfW (personal interview with some PSMNR staff). This again shows that while MINFOF trusts the German partners, it is not reciprocal or mutual, tilting the power element more to the GDC. Nevertheless, there is a fine line between trust to a specific actor and change of behaviour due to motivations initiated by that same actor. This is categorized under incentives. The Power Element Incentives I n an actor-centered perspective, it is the expectation of 19(GIZ, GFA/KfW) 20GFA is an international consultancy firm based in Hamburg, Germany/ DFS-Deutsche Forstservice GmbH. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 246  M. C. YUFANYI MOVUH, C. SCHUSSER Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 247 Table 1. General information of the selected community forests (CFs) in the SWR of Cameroon. Communit(y)ies Forest status Name of management institution Resource status Donor involvement Visited 1 Mundemba Council forest, Reserved Mundemba rural council (Ndian) Rich Yes, GIZ (GTZ) 2009/2011 2 Ikondo Kondo Community forest (not exsting anymore) Mundemba rural council (Ndian) Rich Not anymore but previously GTZ 2009/2011 3 Mosongiseli Community forest, Reserved Mosongiseli Balondo Badiko CIG (MBABCIG) (Ndian) Rich Yes, GIZ (DED) 2009/2011 4 Toko Council forest, (not exsting anymore) Toko rural council (Ndian) Poor Not anymore but previously GTZ 2009/2011 5 Itali Community forest Christian philanthropic Farms and Missions (CPFAM) CIG (Ndian) Rich but no access No 2009/2011 6 Konye Council forest, (not exsting anymore) Konye rural Council (Meme) Poor Not anymore but previously GTZ 2009/2011 7 Nguti Council forest, Reserved Nguti rural council (Kupe-Muanengouba) Rich Yes, GIZ (DED) 2009/2011 8 Manyemen Community forest, Operational REPA-CIG (Kupe-Muanengouba)Rich Not anymore, but previously CA- FECO 2009/2011 9 Akwen Community forest Akwen CF (Manyu) Rich Yes, GIZ (DED) 2009/2011 10 Bakingili Community forest, Reserved Bakingili CF management CIG (Fako) Poor Yes, GIZ (DED) 2009/2011 11 MBACOF Community forest, Reserved MBAAH community forest CIG (Kupe-Muanengouba) nd No 2011 12 Woteva Village Community forest, Reserved Woteva village development CIG (WODCIG) (Fako) nd Yes, GIZ (DED) 2011 13 Bimbia-Bonadikombo Community forest, Operational CF management CIG (Fako) Poor Not anymore but previously MCP 2009/2011 Source: From Author (nd = no data). benefits that encourages actor B to change behaviour through motivation from actor A. Due to incentives from international organisations and agen- cies like the Bretton Woods institution, World bank, and KfW, the GoC was encouraged or otherwise motivated to make changes in its forest policy to suit the goal of these institutions and the 1994 Forestry Law No. 94/01 of 20th January 1994 and its decrees of application No. 95/531/PM of 23 August 1995 were some of the outcomes of this changed behaviour (Mbile et al., 2009; Yufanyi Movuh & Krott, 2011; Bigombé, 2003; Oyono, 2005a: p. 318). Also, the seven million EURO budget made available to the GoC as development assistance for the first phase (2006-2010) of the PSMNR-SWR was identified as motivation or incentive enough to change the behaviour of its ministries like MINFOF. On the other hand, a very good field example is the case of the Community of Ikondo Kondo in the Mundemba municipal- ity. They were resettled from the Korup National Park and promised a CF by the authorities that be. As years went by and although they still had the interest of acquiring a CF which they could manage by themselves, they were lured or otherwise motivated to join the Mundemba CF instead. Here it should also be mentioned that there is also a form of negative incen- tives (disincentives) at play in this case. They accepted to change their behaviour, in accordance with the offer of MIN- FOF, GTZ and DED, else they would have lost everything that would have given them future benefits. Their estimation was that the price they will have to pay for their resistance may be higher than their chance of obtaining a positive outcome, or than the benefit they may gain (Sadan, 1997: p. 48). The Ikondo  M. C. YUFANYI MOVUH, C. SCHUSSER Kondo case shows that although the chief of the community (who works with MINFOF) was well informed about CF and tried to follow up the process for almost ten years, facing a strong incentive (disincentive) structure like MINFOF and the GDC, the Community was driven towards the goals of the pre- sent day GIZ. Motivation in form of financial or non-financial incentives (technical and material) or de-motivation in the form of loss, by MINFOF or the GDC was observed in all the field studies per- formed. 100 per cent of the cases displayed disincentives in form of fear of losing the communal land (e.g. Ikondo Kondo, Mosongiseli, Bakingili, Woteva, Akwen) to GoC, which would then be used for other natural resource management (NRM) purposes. Sometimes it might not be easy to distinguish be- tween disincentive and threat, which we categorized under coercion. The Power Element Coercion In an actor centered perspective, coercion is the practice of forcing actor B to behave in an involuntary manner which can be done by threat of violence or violence from A. In the case of CF in Cameroon, the pre-requisite of a forest inventory and a management plan for the gazettment of CF from MINFOF is a sort of control which can be linked to coer- cion; other stakeholders have to follow them. Some coercive power features for CF are that only MINFOF can decide which CIG or VFMC has fulfilled all the conditions for the gazettment of a particular CF. It also has the physical ability to keep other stakeholders out of the CF management process by using ad- ministrative and implementation limitations, such as signing of legal documents, monopoly of control of the whole CF process, with information and interpretation of legal issues. It also con- trols the administrative procedures required in the process (consultation meetings, forest inventory, boundary demarcation, management plan, management conventions, annual cutting area, quantity and quality of exploitation (in m3 and minimum diameters, respectively), carrying out actions that other stake- holders or actors cannot stop. There are other tenural character- istics and territorial restrictions (the state is the owner of the land) like e.g.: no CF can exceed 5000 ha and CF being just a landlease (for 25 years) issue and bi-product of protected areas and national parks policies, although with Council Forests, a different procedure holds. The coercive power is crowned with the fact that MINFOF staff are also part of the armed forces in Cameroon. MINFOF has its own armed officers and where possible, they could be supported by the police, the para-military or the military offi- cers (in patrols in the forest or on missions). Empirically, there is a fine line when analysing disincentives and the threat of force e.g.: the threat of losing your CF to an- other community if there is no joint management with another community to manage the CF which was previously yours is at the same time an incentive (a disincentive) knowing that if a community does not accept the offer, MINFOF will go ahead and recognise only the other community as the legal custodian for the CF (Ikondo Kondo and Akwen CFs). Important to note is the fact that the state through MINFOF has the overall control of definition and decision making in the process of establishing and management of CFs, while interna- tional organisations like GDC and the World Bank use incen- tives on the one hand and pressure on the other hand, to influ- ence forest policies of the GoC, especially with regard to CF in the name of development. Quoting Mbile et al. (2009: p. 3), “by the mid 1980s, the world economy was in decline, as was Cameroon's and under pressure from the Bretton Woods insti- tutions of the World Bank, the GoC introduced a Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) in 1988 to reduce its debts and to lay the ground for the recovery. From 1988 to 2005, the policy landscape of Cameroon took on a new direction impacting in important ways on forest livelihoods”. Mandondo (2003: p. 9) pointed out that 1994 forest law was, to a significant extent, imposed on the GoC as a condition for financial support under structural reforms funded by the Bretton Woods institutions, particularly the World Bank. Although there was some resis- tance from some politicians, this was overridden by a compliant so-called executive branch of the GoC. Conclusion Power and Development Forest policy throughout Africa originates from European scientific forestry traditions exported during the colonial period (Larson & Ribot, 2007; Yufanyi Movuh & Krott, 2011). The natural resource policy in Cameroon is as old as Cameroon itself, but before the arrival of the first colonial administrators in the late 19th century, natural resources were managed ac- cording to the people’s law or customary law; the village chiefs were the main administrators of resource management (Men- gang Mewondo, 1998; Bigombé, 2003). In the past decades, Cameroon’s rainforests and its conservation for global posterity has attracted much concern among northern “Green” NGOs like WWF, WCS, the international scientific community, the World Bank and bilateral aid agencies like SNV, DFID, GIZ or GDC (just to name a few), and other institutions with an interest in biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. These Organisations and institutions have inherited a rich heritage of colonial expertise and policies which they continue to imple- ment till date. This could be confirmed also by the researcher. Apparently, numerous efforts at rain-forest conservation in Cameroon and elsewhere in Africa, by western development aid agencies and NGOs alike are being made so as to link them with benefits to the rural poor, the custodians of the majority of these forest areas. Today’s, protected areas are being created with the rationale of conservation or premise of mitigating un- sustainable management of forest resources or unsustainable farm practices. The question here is if this is what will lead to sustainability and reduction in poverty. Moreover, the 1994 Forestry law is being implemented in a way which is not bene- fiting the local communities. The current forestry policies and the ways they are selectively implemented continue to repro- duce the double standards and conditions that disadvantage, create and maintain the rural poor (Larson & Ribot, 2007: p. 190). Can a law to foster sustainable forest management, devo- lution of forest resource management to local communities and conservation, externally defined and executed in project modes, be linked to communal approaches? Poverty alleviation, liveli- hood enhancement and economic development; all issues at- tracting contemporary donor funding were components or ob- jectives of the present CF model accrued in the law and at the same time linked to conservation objectives21. One might argue 21The concept of post-development theories can also be used to analyse the intention behind such policies. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 248  M. C. YUFANYI MOVUH, C. SCHUSSER that communities draw economic benefit from the CF, but the state retains de jure ultimate control over the forests and the land on which they grow (Egbe, 1998). For us, the question is also, who are those who benefit economically. Is it the state, the international organisations, the external and internal elites or the rural forest user? Is it the chief and his henchmen who are compliant to the state or the local individual who lives from that forest? The answer through this study is definitely, not positive for the local forest user. Today’s forest policy in Cameroon is still shaped by colonial tradition and dominated by a scientific-cum-bureaucratic para- digm which is deterministic, reductionist, authoritarian and coercive (Murphree, 2004) and bears blueprint of decades of declared colonial heritage, upholding to the underlying concept or principle of colonial land tenure. There are still unresolved land tenure contestations in Cameroon and tenure issues have increasingly stifled the present CF model in achieving its objec- tives. Although the Cameroon Land Ordinance No. 74-1 of July 6, 1974 maintains that the State is the guardian of all lands, traditional authorities continue to exercise de facto rights over land. The resurgence of unresolved historical claims over boundaries and land including the natural resources which are embedded in them has been a stumbling block for CF (e.g.: Itali -CPFAM, Akwen, Ikondo Kondo). The uncertain and colo- nial-like land tenure situation makes the local stakeholders unable to fully embrace participatory forestry. Also, the colo- nial logic of resource accumulation, including building finan- cial capital on forest exploitation (Oyono, 2005b: p. 124), has been replicated, with some modifications by the Cameroonian post-colonial state and propagated by the development aid agencies. This could also be confirmed in all the case studies. The main message here is that the GoC, with financial and technical support from their development cooperation stake- holders like GIZ and KfW, is using their decentralization propaganda to re-centralize power in the forestry sector; i.e., recentralization through decentralization (Ferguson, 1994: 180; Rossi, 2004: p. 3; Devkota, 2010: p. 78). Because the power exerted by the western hegemonies is less visible, it is stronger. The aim at this stage is not to totally reject CF but the present model has failed to produce benefits that can be equated to development after eighteen years. Hence, this model should be reconsidered by policy makers, to suit the needs and demands of the communities concerned. All the areas visited in the re- search displayed rich natural forests but the adjacent communi- ties tend to have high poverty rates. These communities are dependent on their forest resources for a portion of their liveli- hood and none could boost of poverty alleviation through CF or even after acquiring a CF. Instead, they have fallen under the control of the state and its development partners. This study, is to empower these important but marginalised communities, and to improve policies and institutions (Mayers, 2005) in the for- estry sector. From our concept of the ACP, this study has proven that in Cameroon, the state and its international agents use the three elements of power described above to influence and defend their interests in CF. In the study, it was found that at a given situation, all three elements could overlap each other while distinctive processes could be used to analyse each power source separately. Furthermore, testing the post-development theory, it could also be proven that CF, as a development in- strument to alleviate poverty and improve livelihood while sustainably managing the forest has actually not brought sig- nificant or meaningful development to the targeted sector of the society. Millions of Euro or billions of FCFA from international do- nors (with strings attached to them) have been used to steer the popularity and subsequent tradeoffs for programs promoting community participation, especially in CF. Through documents like forest inventories, management plans and conventions between the State and the communities, they keep the commu- nities abbey, exercising far more authority than even before the implementation of the Forestry Law of 1994. With the present CF model, the influence and power of MINFOF and their in- ternational collaborators go up, while the power of the commu- nities to control their forest activities is reduced. Thus, the dif- ferent village committees (CIGs or VFMCs), lacking effective power and sometimes totally cut off from local communities they represent, have become captive to motivations other than the good of the community or the individual forest user. Acknowledgements This research was partly funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft/DFG) and Georg- August-University Goettingen. REFERENCES Agrawal, A., & Redford, K. H. (2006). Poverty, development, and bio- ndiversity conservation: Shooting in the dark? Working paper No. 26. New York: Wildlife Conservation Society. Ahorro, J. (2008). The waves of post-development theory and a con- sideration of the Philippines. Edmonton: University of Alberta. Arts, B., & Van Tatenhove, J. (2004). Policy and power: A conceptual framework between the “old” and “new” policy idioms. Policy sci- ences, 37, 339-356. doi:10.1007/s11077-005-0156-9 Babbington, A. (2000). Re-encountering development: Livelihood tran- sitions and place transformations in the Andes. Annals of the Asso- ciation of American Geographers, 90, 495-520. doi:10.1111/0004-5608.00206 Barry, D., Campbell, J. Y., Fahn, J., Mallee, H., & Pradhan, U. (2003). Achieving significant impact at scale: Reflections on the challenge for global community forestry. URL (last checked 19-23 May 2003). http://www.cifor.org/publications/corporate/cd-roms/bonn-proc/pdfs/ papers/t7_final_barry.pdf Berger, M. (1995). Post-cold war capitalism: Modernization and modes of resistance after the fall. Third World Quarterly, 16, 717- 728. doi:10.1080/01436599550035924 Bigombe´, P. (2003). The decentralized forestry taxation system in Cameroon. In J. Ribot, & D. Conyers (Eds.), Local management and state’s logic. Washington: World Resources Institute. Blaike, P. (1998). Post-modernism and the calling out of development geography. Annual Meeting of the American Association of Geogra- phers, Boston, 25-28 March 1998. Brown, H. C. P., Wolf, S. A., & Lassoie, J. P. (2007). An analytic ap- proach to structuring co-management of community forests in Cam- eroon, Progress in Development Studies, 7, 135-154. doi:10.1177/146499340600700204 Colfer, C. J. P. (2005). The equitable forest: Diversity, community and resource management. Washington: RFF Press. Contreras, A. (2003). Creating space for local forest management—The case of the Philippines. In D. Edmunds, & E. Wollenberg (Eds.), Local forest management: The impacts of devolution policies (pp. 127-149). London: Earthscan. Crew, E., & Harrison, E. (1998). Whose development? An ethnography of aid. London: Zed Books. Devkota, R. (2010). Interests and powers as drivers of community forestry: A case study of Nepal. Göttingen: University Press Göttin- gen. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 249  M. C. YUFANYI MOVUH, C. SCHUSSER Edmunds, D., & Wollenberg, E. (2001). Historical perspectives on forest policy change in Asia: An introduction, Environmental History, 6, 190-212. doi:10.1093/envhis/6.2.190 Egbe, E. S. (1998). The range of possibilities for community forestry permitted within the framework of current Cameroonian legislation. Yaoundé: Ministry of Environment and Forests. Escobar, A. (1995). Encountering development. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Escobar, A. (2000). Beyond the search for a paradigm? post-develop- ment and beyond, Development, 43, 11-14. doi:10.1057/palgrave.development.1110188 Etzioni, A. (1975). A comparative analysis of complex organizations: On power, involvement, and their correl ate s. New York: Free Press. Ezzine de Blas, D., Ruiz Perez, M., Sayer, J. A., Lescuyer, G., Nasi, R., & Karsenty, A. (2009). External influences on and conditions for community logging management in Cameroon. World Development, 37, 445-456. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.03.011 Ferguson, J. (1994). The anti-politics machine: “Development”, depoli- ticization, and bureaucratic power in Lesotho. The Ecologist, 24, 176-181. Fisher, J., van Heerde, J., & Tucker, A. (2010). Does one trust judge- ment fit all? Linking theory and empirics. British Journal of Politics & International Relations, 12, 161-188. doi:10.1111/j.1467-856X.2009.00401.x Foucault, M. (1983). The subject and power. In H. Dreyfus, & P. Rabinow (Eds.), Beyond structuralism and hermeneutics. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Hobley, M. (2007). Forests—The poor man’s overcoat: Foresters as agents of change? Canberra: The Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University. Kiely, R. (1999). The last refuge of the noble savage? A critical as- sessment of post-development theory. The European Journal of De- velopment Research, 11, 30-55. doi:10.1080/09578819908426726 Kippler, C. (2010). Exploring post-development: Politics, the state and emancipation. The question of alternatives. URL(last checked 21 September 2011). http://www.polis.leeds.ac.uk/assets/files/students/student-journal/ug- summer-10/caroline-kippler-summer-10.pdf Krott, M. (1990). Öffentliche verwaltung im umweltschutz, ergebnisse einer behörden-orientierten policy-analyse am beispiel waldschutz. Wien: Braunmüller. Krott, M. (2005). Forest policy a na l ys i s. Dordrecht: Springer. Krott, M., Bader, A., Devkota, R., Schusser, C., Maryudi, A., & Auren- hammer, A. (in review). Identifying driving forces in land use issues by actor-centered power analysis—Example of community forestry. In Review in Land Use Policy. Larson, A. M. (2005). Democratic decentralization in the forestry sector: Lessons learned from Africa, Asia and Latin America. In C. J. Colfer, & D. Capistrano (Eds.), The Politics of decentralization—Forests, power and people (pp. 32-62). London: Earthscan. Larson, A. M., & Ribot, J. C. (2004). Democratic decentralization through a natural resource lens. European Journal of Development Research, 16, 1-25. Larson, A. M., & Ribot, J. C. (2007). The poverty of forestry policy: Double standards on an uneven playing field. Sustainability Science Journal, 2, 189-204. La Viña, A. G. M. (1997). Seeing with clear eyes: The challenge of community-based resource management and the role of academe. In C. Castro, F. B. Pulhin, & L. C. Reyes (Eds.), Community-based re- source management: A paradigm shift in forestry. Los Baños: Uni- versity of the Philippines Los Baños. Little, P., & Painter, M. (1995). Discourse, politics, and the develop- ment process: Reflections on Escobar’s “anthropology and the de- velopment encounter”. American Ethnologist, 22, 602-616. doi:10.1525/ae.1995.22.3.02a00080 Mandondo, A. (2003). Snapshot views of international community forestry networks: Cameroon country study. Center for International Forestry Research. Maryudi, A. (2011). The contesting aspirations in the forests: Actors, interests and power in community forestry in Java, Indonesia. Göttingen: University Press Göttingen. Maryudi, A., Devkota, R., Schusser, C., Yufanyi Movuh, M., Salla, M., Aurenhammer, H., & Krott, M. (2012). Back to basics: Considera- tions in evaluating the outcomes of community forestry. Forest pol- icy an Economics, 14, 1-5. Matthews, S. (2004). Post-development theory and the question of alternatives: A view from Africa. Third World Quarterly, 25, 373- 384. doi:10.1080/0143659042000174860 Matthews, S. (2006). Responding to poverty in the light of the post-development debate: Some insights from the NGO Enda Graf Sahel. Africa developm e nt , 4, 52-72. Mayers, J. (2005). Stakeholder power analysis. London: International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). Mbile, P., Ndzomo-Abanda, G., Essoumba, H., & Misouma, A. (2009). Alternate tenure and enterprise models in Cameroon: Community forests in the context of community rights and forest landscapes. Washington: World Agro forestry Centre and Rights and Resources Initiative. McDermott, M. H., & Schreckenberg, K. (2009). Equity in community forestry: Insights from north and south. International Forestry Re- view, 11, 157-170. doi:10.1505/ifor.11.2.157 Mengang J. M. (1998). Resource use in the tri-national Sangha river region of equatorial Africa: Histories, knowledge forms, and institu- tions. Bulletin, 102, 8-28. MINEP (2004). Etat des lieux de la foresterie communautaire au Cam- eroun. Ministere de l’Environnement et des Forets, Direction des Forêts, Cellule de Foresterie Communautaire. Möllering, G. (2005). The trust/control duality: An integrative perspec- tive on positive expectations of others. International Sociology, 20, 283-305. doi:10.1177/0268580905055478 Murphree, M. (2004). Communal approaches to natural resource management in Africa: From whence and to where? Berkeley: Cen- ter for African Studies. Offe, C. (1977). Einleitung. In P. Bachrach, & M. Baratz (Eds.), Macht und Armut: Eine theoretisch-empirische Untersuchung (pp. 7-34). Frankfurt: Verlag. Oyono, P. R. (2004a). Institutional deficit, representation, and decen- tralized forest management in Cameroon. Washington: Elements of natural resource sociology for social theory and public policy, Envi- ronmental Governance in Africa. Oyono, P. R. (2004b). One step forward, two steps back? Paradoxes of natural resource management decentralization in Cameroon. Journal of Modern African Studies , 42, 91-111. doi:10.1017/S0022278X03004488 Oyono, P. R. (2005a). Profiling local-level outcomes of environmental decentralizations: The case of Cameroon’s forests in the Congo Ba- sin. Journal of Environment and Devel op me nt , 14, 317-337. Oyono, P. R. (2005b). The foundations of the conflit de langage over land and forests in southern Cameroon. African Study Monographs, 26, 115-144. Oyono, P. R. (2009). New niches of community rights to forests in Cameroon: Tenure reform, decentralization category or something else? International Journal of Social Forestry, 2, 1-23. Oyono, P. R., Kouna, C., & Mala, W. (2005). Benefits of forests in Cameroon: Global structure, issues involving access, and decision- making hiccoughs. Forest Policy and Economics, 7, 357-368. doi:10.1016/S1389-9341(03)00072-8 Pieterse, J. N. (1998). My paradigm of yours? Alternative development, post-development, and reflexive development. Development and Change, 29, 343-373. doi:10.1111/1467-7660.00081 Poffenberger, M. (2006). People in the forest: Community forestry experiences from southeast Asia. International Journal of Environ- ment and Sustainable Develo pm e n t, 5, 57-69. Pulhin, J. M., & Dressler, W. H. (2009). People, power and timber: The politics of community—Based forest management. Journal of Envi- ronmental Management, 91, 206-214. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.08.007 Rahnema, M. (1997). Development and the people’s immune system: The story of another variety of AIDS. In M. Rahnema, & V. Bawtree, (Eds.), The post-development reader (pp. 111-129). London: Zed Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 250  M. C. YUFANYI MOVUH, C. SCHUSSER Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 251 Books. Rahnema, M., & Bawtree, V. (Eds.) (1997). The post-development reader. London: Zed Books. Rebugio, L. L. (1998). Paradigm shift: The key to sustainable forestry and environmental resources management. Asian Journal of Sus- tainable Agriculture, 1, 13-24. Rossi, D. (2004). Revisiting foucauldian approaches: Power dynamics in development projects. Journal o f De v el o p me n t S t ud i e s, 4 0, 1-29. doi:10.1080/0022038042000233786 Sachs, W. (Eds.) (1992). The development dictionary. A guide to knowledge as power. London: Zed Books. Sadan, E. (1997). Empowerment and community planning: Theory and practice of people-focused social solutions. Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad. Sarin, M., Singh, N., Sundar, N., & Bhogal, R. (2003). Devolution as a threat to democratic decision-making in forestry? Findings from three states in India. in D. Edmunds, & E. Wollenberg (Eds.), Local forest management: The impacts of devolution policies (pp. 55-126). London: Earthscan. Schnell, R., Hill, P., & Esser, E. (2005). Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung. München: Auflage. Schusser, C. (2012). Who determines biodiversity? An analysis of actors’ power and interests in community forestry in Namibia. Forest Policy and Economics, 21 July 2012. Schusser, C., Krott, M., Devkota, R., Maryudi, A., Salla, M., & Yu- fanyi Movuh, M. C. (2012). Sequence design of quantitative and qualitative surveys for increasing efficiency in forest policy research. Allgemeine Forest und Jagdzeitung, 183, 75-83. Shackleton, S., Campbell, B., Wollenberg, E., & Edmunds, D. (2002). Devolution and community-based natural resource management: Creating space for local people to participate and benefit? Natural Resource Perspectives, 76, 1-6. Sikor, T. (2006). Analyzing community-based forestry: Local, political and agrarian perspectives. Forest Policy and Economics, 8, 339-349 doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2005.08.005 Simon, H. A. (1981). Entscheidungsverhalten in organisationen: Eine Untersuchung von entscheidungsprozessen in management und verwaltung. Landsberg am Lech. Sobze, J. M. (2003). Analysis of implication of forest policy reform on CF in Cameroon: Case study of Lomié. Göttingen: Cuvillier Verlag. Storey, A. (2000). Post-development theory: Romanticism and pontius pilate politics. Development, 43, 4. Sunderlin, D. W. (2004). Community forestry and poverty alleviation in Cambodia, Lao-PDR, and Vietnam: An agenda for research. Jakarta: Center for International Forestry Research. Thoms, C. A. (2006). Conservation success, livelihoods failure? Com- munity forestry in Nepal. Policy Matters, 14, 169-179. Weber, M. (1964). The theory of social and economic organization. New York: Oxford University Press. World Bank (2004). Sustaining forests: A development strategy. Wa- shington: The World Bank. World Bank (2005). World development indicators 2005. Washington: World Bank. World Resources Institute (2005). The wealth of the poor-managing ecosystems to fight poverty. Washington: United Nations Develop- ment Program, United Nations Environment Program, World Bank, World Resources Institute. Yufanyi Movuh, M. C. (2007). Community-based biodiversity conser- vation management: Reaching the goal of biodiversity conservation and community development. Master’s Thesis, München: GRIN Pub- lishing. Yufanyi Movuh, M. C., & Krott, M. (2012). The colonial heritage and post-colonial influence, entanglements and implications of the con- cept of community forestry by the example of Cameroon. Forest Policy and Economics, 15, 70-77. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2011.05.004

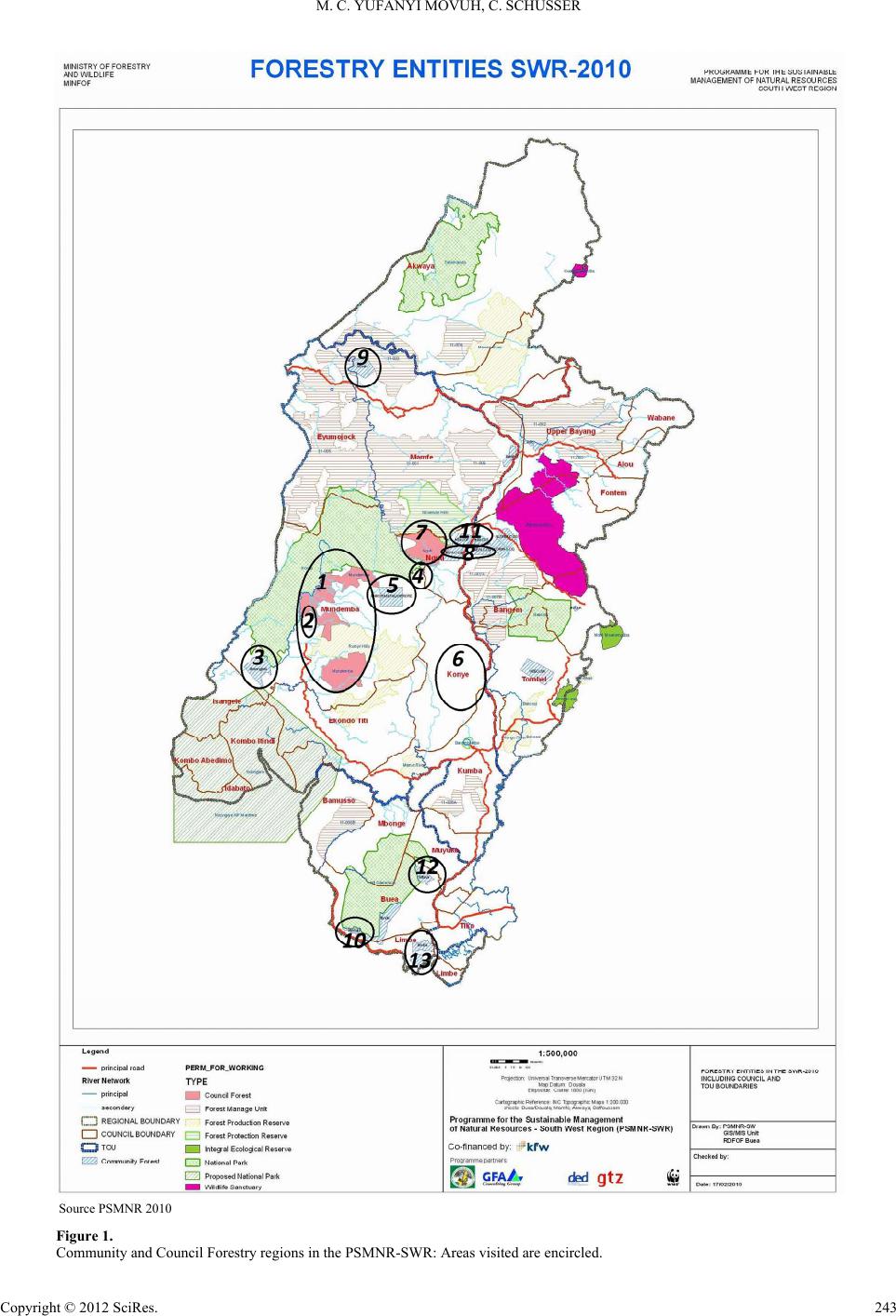

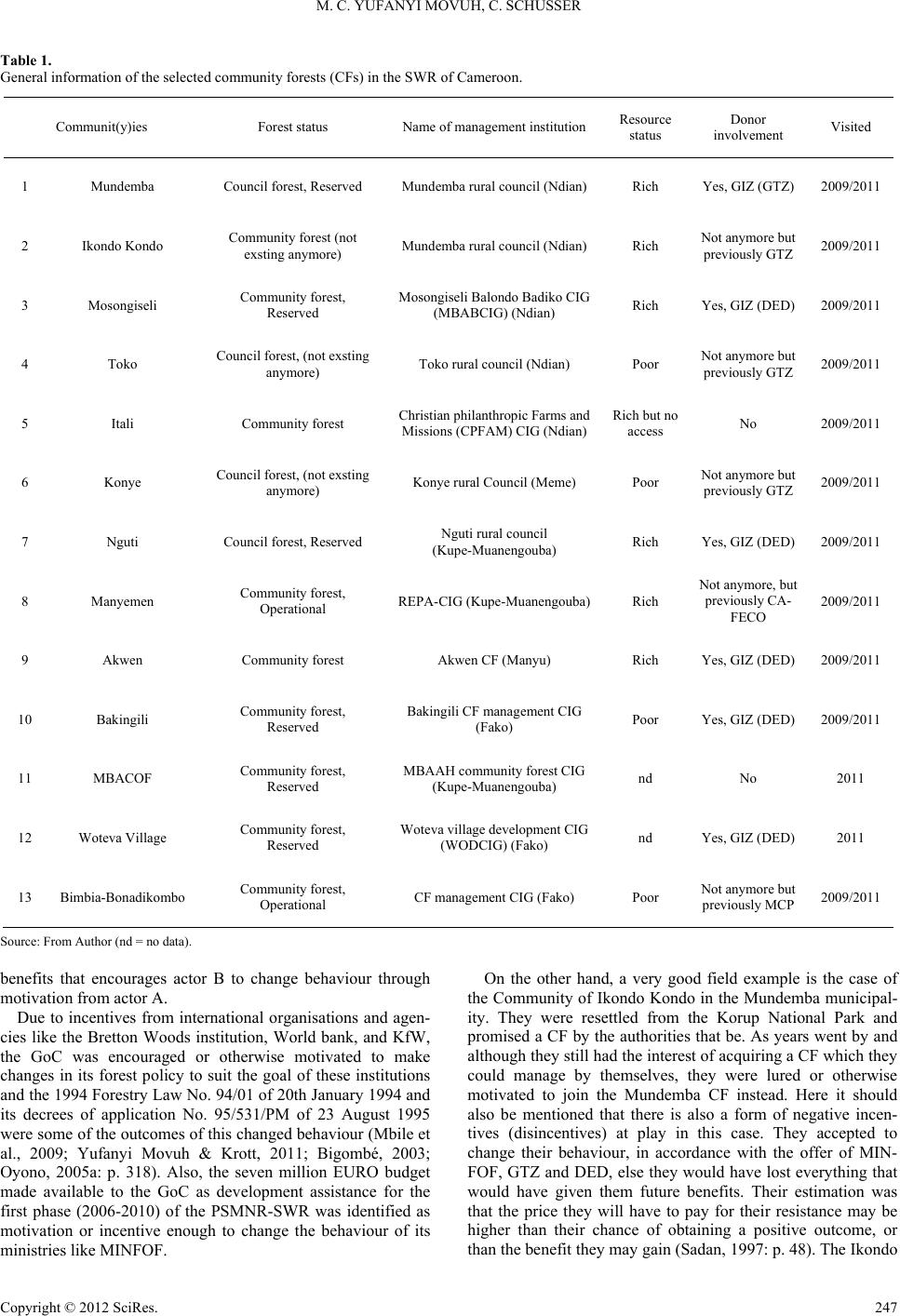

|