Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

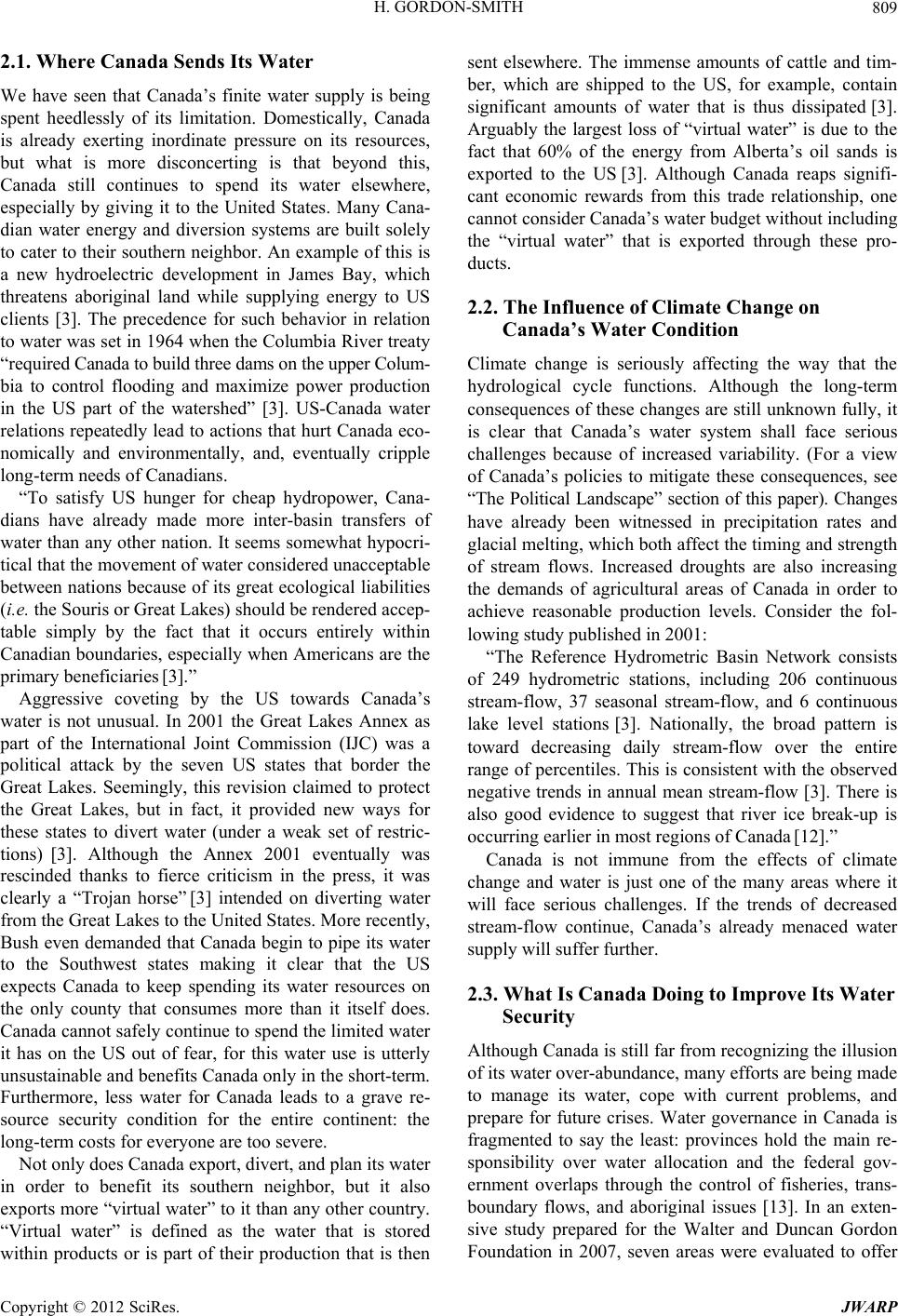

Journal of Water Resource and Protection, 2012, 4, 807-811 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jwarp.2012.410093 Published Online October 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jwarp) Water Myths: The Illusion of Canada’s Endless Water Supply Henry Gordon-Smith The Earth Institute, Columbia University, New York, USA Email: info@henrygordonsmith.com Received August 3, 2012; revised September 5, 2012; accepted October 4, 2012 ABSTRACT This paper explores the common misconception that Canada has an infinite supply of freshwater. The true amount of water availability in Canada is explored, and the location of the majority of Canada’s water supply is described. As a consequence of a more precise assessment of Canada’s actual hydrologic situation the paper seeks to dash the danger- ous myth of Canada’s water inexhaustibility, which is straining the country’s precious resource increasingly. Finally, this paper discusses the major threats to Canada’s water supply, which are from both external factors as well as its in- ternal sociopolitical weakn ess. A solution to these problems is considered. Keywords: Canadian Wat er Supply; Hydr o l ogy ; Water Security; Canadian Water Polic i es; Ca nadian Gover nmental Fragmentation; US-Canadian Political Relations; Water Wars 1. Introduction Canada is perceived by environmentalists and laymen alike to be an exceedingly resource-rich country. This is arguably true, in comparison to the majority of other countries. However, an in-depth scrutiny of Canada’s resources and the factors that affect them presents a view that most would find surprising; this is especially the case with Canada’s water assets, which are perceived by many as being so copious that they are often regarded as infinite. The myth of Canada’s inexhaustible water capi- tal ought to be debunked, for not only does Canada not possess as much water as unilaterally thought—both do- mestically and abroad—but some dangerously over- looked factors make its accessibility troublesome. That most Canadians believe they have such an excess of wa- ter is too onerous a belief, because it inevitably leads them to consume it at an alarming and unsustainable rate. It is essential that Canadian s be aware of the finite nature of their water resources. This paper seeks to outline the condition of Canada’s true water circumstances, its major issues, and recommendations for improvement. Canada indeed does have significant water resources, but a lack of awareness as well as Canada’s government’s perpetual political fragmentation place the country’s water security in peril. It has been argued that in less than 10 years, half the world’s population will be living in water scarcity [1]. Many countries are already experiencing severe, annual water shortages, because their hydrological resources cannot sustain the demands placed upon it by their demo- gr aphy. Even the United States has experienced an alarm- ing increase of instances of water scarcity and droughts [2]. Effective water management is a major challenge for most nations and thus a highly necessary investment —and one that Canada must take more seriously. Water assets can be separated into three distinct cate- gories: stock, supply, and availability. Stock refers to the fresh water that is stored in lakes; it is a non-renewable resource that can only be used once before needing re- filling by an external source. Water stock is not a sus- tainable source of fresh water and is therefore not to be considered a true reflection of a state’s water capital. Canada’s examples of this water category are the Great Lakes, which hold 20% of the world’s fresh water stock [3]. In fact, Canada has the largest amount of stock stored in lakes of any sin gle coun try though “many naively con - sider the Great Lakes to be nearly inexhaustible sources of freshwater” [3]. Many actually conceive of these large bodies of water as the trophies of Canada’s privileged water situation. Misconceptions of this sort are responsi- ble for the risky creation of Canada’s water myth. The truth, in fact, is that the stock in the great lakes is equal to 2 years of runoff from the entire world’s rivers [4,5]: that would take 100 - 300 years to refill them. Supply is fresh water, which is renewed annually as part of the hydrological cycle. This type of water comes fro m pre cipita tion, snowfall, and aquifer discharges [4,5]; it moves through rivers and underground sources and is renewable; but it is not unlimited, and must be used ap- C opyright © 2012 SciRes. JWARP  H. GORDON-SMITH 808 propriately, otherwise, the balance in its function within the water system could be impaired. Water shortages often occur when supply is consumed unsustainably. Canada holds about 6.5% of the world’s supply [4,5]. Canada’s supply is generally held as being an overabun- dant surplus, because of Canada’s relatively small popu- lation. However, when one considers availability and supply, the picture beco mes increasing ly less optimistic. Availability refers to the amount of supply that is available to be harnessed by the human population; it depends on water flows, population distribution—the location of supply. For example, even though the US and Canada have very similar amounts of supply, 60% of Canada’s water flows northward [4,5], thus reducing its availability dramatically. This is of particular concern, since 85% of the Canadian population lives within 250 km of the US border [6], and, most of the fresh water flowing northward is still inaccessible today, which leaves only the remaining 40% of supply for the majority of Canadians. Because of their inability to access water, the actual percentage of supply for Canadians is reduced from an abundant 6.5% to 2.6% of the global supply [6]. Despite this drastic reduction in availability, Canada’s position as a water resource-holder is still hardy com- pared to other nations; but as this paper shall outline, much of this water is mismanaged, diverted, and ex- ploited. 2. How Canada Is Utilizing Its Available Water Now that we have a more accurate picture of the water capital in Canada, we shall examine how Canada deploys its hydrological resources. Data from 2006 shows that Canadians withdrew approximately 5700 million cubic meters of water and consumed 1300 of it [7]. The rest was “returned back to the system internally, displaced externally to another watershed or polluted and returned”. Municipalities use in total an average of 638 liters per day per capita [6]. According to these figures, “Cana- dians consume more water per capita than do people of any other country, oth er than the United States” [8 ]. This leads to significant water shortages, especially in the southern part of the country, which has limited water re- sources. Canadians’ over consumption of water resulted, for example, that in 1999 a quarter of municipalities reported having water distribution problems [8]. This datum is shocking in itself if we realize that 10% - 50% of potable water in municipalities is lost to leaks in the distribution system [9]. The consumption on the muni- cipal level is only part of the problem as the chart below illustrates. As Figure 1 illustrates, thermal power generation ab- sorbs 63% of Canada’s hydraulic resources. Although thi s percentage is very high, we need not condemn it her e, because it is generally sustainable and better than most energy alternatives. The large quantity of water used for hydroelectric purposes does however lead to consider that if such large quantities of water are being used for energy, water use in Canada as a whole ought to be managed with greater care: the use of water for energy obviously further increases its value to Canada. Manufacturing is a necessary part of a modern nation’s economy; in the case of Canada, industry consumes much of Canada’s fresh water supply. The Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River are the world’s single largest source of freshwater; they supply drinking water to 45 million people [3]. Furthermore, the watershed of this area is home to most of Canada’s manufacturing and a quarter of its agriculture [3]. The fresh water in the Great-Lake area is under enormous pressure from both Canada and the US: massive urban growth and industry, as a result of rapidly rising immigration, increases both the consumption of fresh water in the area as well as the pollution of the remaining water. The oil industry in Al- berta also poses immense water spending by Canada, as each year over 200 billion liters of water are used to pump oil from wells; but unfortunately, much of that water comes from aquifers that do not have adequate replenishment rates because of low precipitation [9]. An- other significant source of consumption is the pulp and paper industry, which also—in turn—releases haz- ardous chemicals into the water system. Thus, in the name of economic progress Canada is seriously worsen- ing its water security and condition. In the West, significant growth is occurring in urban areas and the surrounding agricultural land is being overused. These areas have minimal precipitation and depend highly on the Rocky Mountains for flowing fresh water [3]. To ad d to the prob lem, once again, ru no ff fro m farms often pollutes much of the limited ground water and rivers that do exist. In the prairies of Alberta a large network of agriculture is in place and significant amounts of water are needed to irrigate this semi-arid area. It has already been demonstrated that existing water supplies in Alberta are “at, or near, full allocation and competing demands and large irrigated agricultural water extractions have now been recognized as reaching a critical limit” [10]. Similar problems are occurring in the Okanagan Basin region of British Columbia where 70% of the wa- ter licensed for consumptive use is allocated [11]. Figure 1. Principal water uses in Canada, 2000. Source: en- vironment Canada. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JWARP  H. GORDON-SMITH 809 2.1. Where Canada Sends Its Water pply is being eap hydropower, Cana- di the US towards Canada’s w ts water in 2.2. The Influence of Climate Change on Climg the way that the asin Network consists of limate ch 2.3. What Is Canada Doing to Improve Its Water Altha is still far from recognizing the illusion We have seen that Canada’s finite water su spent heedlessly of its limitation. Domestically, Canada is already exerting inordinate pressure on its resources, but what is more disconcerting is that beyond this, Canada still continues to spend its water elsewhere, especially by giving it to the United States. Many Cana- dian water energy and diversion systems are built solely to cater to their southern neighbor. An example of this is a new hydroelectric development in James Bay, which threatens aboriginal land while supplying energy to US clients [3]. The precedence for such behavior in relation to water was set in 1964 when th e Columbia River treaty “requ ired Canada to build three dams on the upper Colum- bia to control flooding and maximize power production in the US part of the watershed” [3]. US-Canada water relations repeatedly lead to actions that hurt Canada eco- nomically and environmentally, and, eventually cripple long-term needs of Canadians. “To satisfy US hunger for ch ans have already made more inter-basin transfers of water than any other nation. It seems somewhat hypocri- tical that the movement of water considered unacceptable between nations because of its great ecological liabilities (i.e. the Souris or Great Lakes) should be rendered accep- table simply by the fact that it occurs entirely within Canadian boundaries, especially when Americans are the primary beneficiaries [3].” Aggressive coveting by ater is not unusual. In 2001 the Great Lakes Annex as part of the International Joint Commission (IJC) was a political attack by the seven US states that border the Great Lakes. Seemingly, this revision claimed to protect the Great Lakes, but in fact, it provided new ways for these states to divert water (under a weak set of restric- tions) [3]. Although the Annex 2001 eventually was rescinded thanks to fierce criticism in the press, it was clearly a “Trojan horse” [3] intended on diverting water from the Great Lakes to the United States. More recently, Bush even demanded that Canada begin to pipe its water to the Southwest states making it clear that the US expects Canada to keep spending its water resources on the only county that consumes more than it itself does. Canada cannot safely continue to spend the limited water it has on the US out of fear, for this water use is utterly unsustainable and benefits Canada only in th e short-term. Furthermore, less water for Canada leads to a grave re- source security condition for the entire continent: the long-term costs for everyone are too severe. Not only does Canada export, divert, and plan i order to benefit its southern neighbor, but it also exports more “virtual water” to it than an y other country. “Virtual water” is defined as the water that is stored within products or is part of their production that is then sent elsewhere. The immense amounts of cattle and tim- ber, which are shipped to the US, for example, contain significant amounts of water that is thus dissipated [3]. Arguably the largest loss of “virtual water” is due to the fact that 60% of the energy from Alberta’s oil sands is exported to the US [3]. Although Canada reaps signifi- cant economic rewards from this trade relationship, one cannot consider Canada’s water budget without including the “virtual water” that is exported through these pro- ducts. Canada’s Water Condition ate change is seriously affectin hydrological cycle functions. Although the long-term consequences of these changes are still unkn own fully, it is clear that Canada’s water system shall face serious challenges because of increased variability. (For a view of Canada’s policies to mitigate these consequences, see “The Political Landscape” section of this paper). Changes have already been witnessed in precipitation rates and glacial melting, which both affect th e timing and strength of stream flows. Increased droughts are also increasing the demands of agricultural areas of Canada in order to achieve reasonable production levels. Consider the fol- lowing study published in 2001: “The Reference Hydrometric B 249 hydrometric stations, including 206 continuous stream-flow, 37 seasonal stream-flow, and 6 continuous lake level stations [3]. Nationally, the broad pattern is toward decreasing daily stream-flow over the entire range of percentiles. This is consisten t with the observed negative trends in annual mean stream-flow [3]. There is also good evidence to suggest that river ice break-up is occurring earlier in most regions of Canada [12].” Canada is not immune from the effects of c ange and water is just one of the many areas where it will face serious challenges. If the trends of decreased stream-flow continue, Canada’s already menaced water supply will suffer further. Security ough Canad of its water over-abundance, many efforts are being made to manage its water, cope with current problems, and prepare for future crises. Water governance in Canada is fragmented to say the least: provinces hold the main re- sponsibility over water allocation and the federal gov- ernment overlaps through the control of fisheries, trans- boundary flows, and aboriginal issues [13]. In an exten- sive study prepared for the Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundation in 2007, seven areas were evaluated to offer Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JWARP  H. GORDON-SMITH 810 a clear representation of the current state of water secu- rity action in Canada. The seven areas studied were: 1) Ecosystem protection; 2) Economic production; 3) Eq- uity and participatio n; 4) Integration; 5) Water conserva- tion; 6) Climate variability and change; and 7) Trans- boundary sensitivity. As is clear in the assessment, Can- ada has made some progress on water security matters but is still “missing a strong national understanding of options and approaches” [14]. 3. The Political Landscape disjointed federalism been cited within this an nu a is facing a severe water security crisis in the fu 4. Conclusions uivocally Canada does not have as kker makes five recommendations for impr- ov and the pro- a national water strategy based on sustain- learned platform so that stakeholders ld investigate making water re of great value and if implemented, co er resources Canada’s political structure—its —is often cited as a main source of the multifarious pro- blems the country faces. Once again, this time through water security, it becomes clear that the inarticulate separation of power b etween the federal govern ment and the provinces is a major roadblock against real progress. As mentioned earlier, the provinces have jurisdiction over their resources while Ottawa can only get involved if it somehow relates to foreign relations, fisheries, abo- riginal issues and trans-boundary flows. All of these ar- eas have played a significant role in Canada’s water se- curity history, so it may be said that the federal govern- ment has some power in the matter. The fragmented poli- tics between the provinces and Ottawa, however, have been a source of policy clumsiness, which prevented Canada from formulating a strong and implementable water strategy: provinces are on their own, competing with internal and external corporate interests and the ag- gressive resource-consuming southern state. Canada’s frayed political system will continue to be a hindrance to the progress for water security as well as other complex national interest concerns. US-Canada relations haved vinces. Develop merous other papers as a main source of concern for Canada’s water security; Canada’s weakness in dealing with the water issue has led to further aggression towards the precious resource by US corporations and political actors. Perhaps th e Canadian leadership is still convinced of the “water myth” and is not realizing its inaccuracy. But the US will always aggressively pursue whatever resources it needs—whether it be through economic, po- litical, or military means—thus leaving Ottawa vacillat- ing over its conduct. That the US has a track record of military aggression in order to obtain resource security ought not to be forgotten: it would be unwise to assume that water will be an exception. As Canada’s economy depends on the US it has understandably chosen repeat- edly to submit to their requests; but at some point US demands will be too much for Canada. That is the reason why finding solutions to this relationship is increasingly urgent. Canad ture: it is consuming unsustainably, and in add ition, US interests are exploiting it. This is occurring in conjunct- tion to the myriad of challenges that climate change pose, as well as the increasing problem of population growth. In 2005 North American leaders backed by corporate interests signed the Security and Prosperity Partnership (SPP) [5]. The SPP was an ambitious program that inte- grated the economies, resources, and security of the United States, Canada, and Mexico. Partly as a response to terrorism, it was also devised against market volatility and resource depletion. The SPP was proscribed in 2009 because of severe criticism by the Canadian press and the general public. Nevertheless, the interest to streamline North American natural resources is a threat that is still with us. Even though uneq much water as is perceived, unfortunately, the general conception is still that Canada has inexhaustible re- sources in the North that will someday be accessible. The illusion of Canada’s water surplus is also a matter of na- tional security, as Canada cannot afford to be stripped of its natural resources d ue to a false understanding of their plenty-fullness or availability. As it is only a matter of time before Canadian water resources will be part of one North American resource pool, it is even more urgent that Canada develops effective national water manage- ment plans. Karren Ba ing Canadian attitude toward water policies [4]. These are valuable directives for water management programs: Revise Canada’s federal water policy. Improve cooperation between Ottawa able solutions. Create a lessons can share best practices. Federal government shou a human right. All her points a uld solve the looming dangers of water supply in Can- ada. Although not mentioned explicitly, many of her poi- nts are also designed to improve the Canadian political fragmentation, which, as was evinced in our overview, is the marrow of Canada’s challenge to improve its water security. The effect on external relations (another major challenge) would also arguably be improved, as Can- ada’s stance could be firmer against US aggression on water issues. At the moment, the powerful political and corporate actors in the US are able to engage the prov- inces to play against each other; this gives them an ad- vantage that shoul d not be u n derest i mated. After this brief study of the state of the wat Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JWARP  H. GORDON-SMITH Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JWARP 811 an REFERENCES [1] C. Amodeo, “g,” Geographical . Pierce, T. P. Barnetta, M d A. M. Hurley, “Rising Tensions: da’s My th of Wa- r, “On Guard for Thee? Water enge,” l Uses,” 2012. n&n=8 urces Cananda, “Water Consumption,” 2012. nd T. Clarke, “Blue Gold: The Battle against ins, “Canadian Agriculture Demand, “Okanagan Basin . D. Harvey, W. D. Hogg and T. R. Yuzyk, ts Interface,” Loë, J. Varghese, C. Ferrey ra and R. D. Kreutz- d policies in Canada, the “myth of water abundance” ought to be discredited: half of the water supply that Canada does have is largely inaccessible by the majority of its population; and mismanagement, poor infrastruc- ture, and a wasteful mentality cause the rest of Canada’s renewable water to be severely overused. In addition, Canada is losing much of its water through virtual means as well as being increasingly threatened by climate change. Finally, as we have seen, Canada’s water supply is being coveted by the United States, and Canada is clearly unable to defend itself politically, economically, or militarily. But Canada, as a relatively young nation with significant resources per capita and the power to decide its own fate—without, in the end, outside inter- ferences—has a unique opportunity to protect itself by acting decisively to manage its resources independently. Clearly, what is needed is a judicious, self-interested national water program, which, implemented at the local level, shall educate citizens and dismantle the dangerous myth of Canada’s water abundance. Water Fight Is Loomin, . “ Vol. 74, No. 4, 2002, p. 10. [2] D. R. Cayan, T. Das, D. W Tyree and A. Gershunov, “Future Dryness in the South- west US and the Hydrology of the Early 21st Century Drought,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sci- ences United States of America, Vol. 107, No. 50, 2010, pp. 21271-21276. [3] D. W. Schindler an Canada/US Cross-Border Water Issues in the 21st Cen- tury,” Notes for Remarks Presented at the Centre for Global Studies Conference on Canada/US Relations at the University of Victoria, Victoria, 2004. [4] J. B. Sprague, “Great Wet North? Ca na ter Abundance,” In: K. Bakker, Ed., Eau Canada, UBC Press, Vancouver, 2007. [5] D. Shrubsole and D. Drape (Ab) Uses and Management in Canada,” In: K. Bakker, Ed., Eau Canada, UBC Press, Vancouver, 2007. [6] M. C. Rook, “Canada’s Freshwater: Our New Chall Canadian Forces College, 2010. [7] Environment Canada, “Withdrawa http://www.ec.gc.ca/eau-water/default.asp?lang=E 51B096C-1 [8] Natural Reso http://atlas.nrcan.gc.ca/site/english/maps/freshwater/cons umption/1 [9] B. Maude a Corporate Theft of the World’s Water,” McClelland & Stewart Ltd., Toronto, 2002. [10] D. R. Corkal and P. E. Adk and Water,” 13th IWRA World Water Congress, Montpel- lier, 1-4 September 2008. [11] Okanagan Water Supply & Water Supply and Demand Analysis, Phase 2 Prospec- tus,” 2007. [12] X. Zhang, K Trends in Canadian Streamflow,” Water Resources Re- search, Vol. 37, No. 4, 2001, pp. 987-998. [13] S. Hodgson, “Land and Water—The Righ Uni t e d Nations Food and Agriculture Organiza t i o n, R o me , 2004. [14] R. C. De wiser, “Water Allocation and Water Security in Canada: Initiating a Policy Dialogue for the 21st Century,” Report Prepared for the Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundation, Guelph Water Management Group, University of Guelph, Guelph, 2007. |