Open Journal of Urology, 2012, 2, 157-163 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/oju.2012.223030 Published Online October 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/oju) Clinical Evaluation of Efficacy and Safety of a Herbal Formulation in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: A Single Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study* Ramanathan Jeyaraman1, Pralhad S. Patki2# 1Department of Urology, Madras Medical College, Chennai, India 2The Himalaya Drug Company, Bangalore, India Email: #dr.patki@himalayahealthcare.com Received July 4, 2012; revised August 6, 2012; accepted August 26, 2012 ABSTRACT Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a condition intimately related to ageing. Currently available treatment options for the management of BPH have various limitations and associated adverse effects. A polyherbal formulation is claimed to be beneficial in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. This single blind, placebo-controlled study evaluated the clinical efficacy and safety of polyherbal formulation in BPH. Material and Methods: A total of 60 patients who were diagnosed as BPH and who were willing to give informed consent were included in the study. At the randomization visit, a detailed medical history was obtained and the patients underwent a thorough systemic examination and digital rectal examination. Routine blood analysis, urinalysis and serum levels of prostate specific antigen were carried out. Abdominal pelvic ultrasonography was done at entry and after completing the study. The severity of the urinary pa- rameters was evaluated using American Urological Association symptom score. All the patients were randomized using random table into either polyherbal group (n = 30) or placebo (n = 30). Each patient received either polyherbal formula- tion or placebo in a dose of 2 capsules twice a day with meals for two months. All adverse events reported by the pa- tients or observed by investigators were recorded. Statistical analysis was done according to the intention-to-treat prin- ciples. Analysis was performed between the groups using Fisher’s exact test or unpaired “t” test (Independent t-test). Results: Fifty-six patients completed the study. There was a significant improvement in the mean AUA symptom score, PVR urine volume urinary hesitancy, intermittent flow, straining during urination, sense of incomplete micturition and frequency of night-time urination, in the polyherbal formulation group. Four patients from the placebo group withdrew from the study due to lack of benefit to the treatment. Conclusion: The beneficial clinical efficacy of polyherbal for- mulation observed in this study in the management of BPH could be due to the synergistic actions of its potent herbs. This polyherbal formulation was well tolerated and safe. Keywords: Phytotherapy; Ayurveda; Clinical Evaluation 1. Introduction The prostate is about the size of a walnut in men younger than 30 years [1], situated at the base of the bladder, deep in the male pelvis, and surrounds the proximal portion of the urethra. Prostate size increases gradually leading to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) in most men older than 60 years [2]. Benign prostatic hyperplasia is a non- malignant enlargement of the prostate that is due to ex- cessive cellular growth of both the glandular and the stromal elements of the gland in the periurethral zone of the prostate [3]. BPH is nearly universal result of the aging process in men. The principal hypothesis for the hypertrophic reaction of prostate tissue is steroid mediated cellular proliferation and inflammatory response to local infection. Also inef- ficiency of apoptotic machinery and aberrant stromal- epithelial interactions are also suggested to probably contribute to the abnormal growth of prostate [4]. As men age, the level of circulating testosterone de- creases, while the number of androgen receptors in- creases, causing the overgrowth of the prostate [5]. The result is an enlarged prostate gland that causes bladder outflow obstruction. Because the enlarged gland ob- structs the prostatic urethra, the patient strains during urination to overcome the obstruction. Over time, strain- ing to urinate causes the detrusor muscle of the bladder to thicken and diverticula to form in the bladder. When the detrusor muscle can no longer generate sufficient *Financial support: The Himalaya Drug Company, Makali, Bangalore- 562 123 (India). #Corres ondin autho . C opyright © 2012 SciRes. OJU  R. JEYARAMAN, P. S. PATKI 158 pressure to overcome the urethral obstruction, the blad- der fails and retains urine. Destruction of striated and smooth muscles results in urinary incontinence [6]. Symptoms of BPH can be either irritative or obstruc- tive. Obstructive symptoms include straining, hesitancy, weak stream, intermittency, and sense of incomplete bladder emptying and irritative symptoms include ur- gency, frequency, and nocturia [7]. Based on the American Urological Association (AUA) symptom score prostate can be classified as mild, moder- ate and severe. Symptoms are measured on a scale of 1 to 35. A score of 1 to 7 is classified as mild symptoms, 8 to 19 signify moderate symptoms, and a score from 20 to 35 signifies severe symptoms [8]. The AUA recommends routine urinalysis for the di- agnosis of BPH. Urinalysis can reveal pyuria and bacte- riuria suggesting infection, hematuria suggesting inflam- mation or urothelial malignancy, or active urinary sedi- ment suggesting postobstructive nephropathy. Optional studies include serum creatinine and prostate specific antigen (PSA) [9]. The PSA is a strong predictor of prostate volume in BPH [10] and level increases at ad- vanced stage of the disease and helpful in monitoring at later stage for clinical management [11]. Although most of the patients seek medical care for the symptoms of BPH, urinary tract obstruction due to longstanding BPH can cause some major health problems such as bleeding from the prostate, recurrent infections, bladder stones, inability to urinate, and renal insuffi- ciency. The goal of therapy is to reduce or alleviate lower uri- nary tract symptoms, to prevent complications, and to minimize the adverse effects of treatment [12]. Watchful waiting is the preferred management strategy for patients with mild symptoms and also an appropriate option for men with moderate to severe symptoms who have not yet developed complications of BPH. Currently available drugs for treatment of BPH are α1-adrenergic antagonists (tamsulosin, alfuzosin, doxa- zosin and terazosin) and 5α-reductase inhibitors (finas- teride and dutasteride). These medications act on dy- namic and static components of bladder outlet obstruc- tion [13,14]. α1-Adrenergic antagonists act on the dy- namic component of bladder outlet obstruction are the initial choice of medical treatment in most men with BPH. In men with large prostate glands (>40 mL), higher PSA levels, and moderate to severe symptoms, treatment with 5α-reductase inhibitors or combination therapy is considered [15]. Open surgical removal of prostatic adenoma remained the gold standard treatment of BPH for many decades. The conversion from open to transurethral surgery oc- curred gradually [16]. Minimally invasive procedures are performed in more advanced degrees of outlet obstruc- tion. In patients in whom medical and minimally invasive options for BPH have been unsuccessful, more invasive treatment are considered like transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). Both selective and less-selective α-blockers may be associated with dizziness, asthenia, and postural hypoten- sion, limiting therapy. Decreased libido and impotence are more common in men taking finasteride [17]. Al- though, transurethral resection is an effective treatment for symptomatic BPH, approximately 15% to 25% of pa- tients who undergo surgery do not have satisfactory long- term outcomes [18]. Because of these problems and the desire of patients to avoid surgery whenever possible, there has been much interest in alternative treatments. In the present study, a polyherbal formulation is evaluated for its efficacy and safety. Good agricultural and collec- tion practice (GACP) was followed during the collection and manufacture of this Ayurvedic formulation. Botani- cal identification and desired quality were in accordance with the guidelines of Pharmacopoeial Standards of an Ayurvedic formulations and were carried out by a quail- fied chemist approved by the Food and Drug Administra- tion. The formulation was finalised by a team of Ay- urvedic Scientists after scanning Ayurvedic and contem- porary scientific literatures. This formulation has been approved by regulatory authorities in India as an Ay- urvedic formulation and is available for clinical practice. The principal herbs of this polyherbal formulation in- clude extracts of Curculigo orchioides, Lactuca scariola, Asteracantha longifolia, Mucuna pruriens, Parmelia per- lata, Argyreia speciosa, Tribulus terrestris and Leptade- nia reticulat (Table 1). The stability of this formulation was tested by accelerated study (upto 6 months) and real time study (upto 3 years). Table 1. Composition of polyherbal formulation: each capsules contains. Plant Name Quantity Mushali ( Curculigo orchioides ) 32 mg Vanya kahu ( Lactuca scariola ) 8 mg Kokilaksha ( Asteracantha longifolia ) 16 mg Kapikachchu ( Mucuna pruriens ) 20 mg Shaileyam ( Parmelia perlata ) 32 mg Vriddhadaru ( Argyreia speciosa ) 64 mg Gokshura ( Tribulus terrestris ) 64 mg Extracts * of: Jeevanti ( Leptadenia reticulata ) 64 mg * Herbs in the above formula are cleaned and reduced to a coarse powder in a pulverizer individually and blended in the ratio mentioned above. This herbal blend is extracted with demineralized water, filtered and concentrated. The extract is then granulated and reduced to required mesh size, blended and filled into capsules. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJU  R. JEYARAMAN, P. S. PATKI 159 2. Aim of the Study This study was planned to evaluate the clinical efficacy and safety of a polyherbal formulation in the manage- ment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. 3. Materials and Methods 3.1. Study Design This was a single blind, randomized and placebo-con- trolled clinical study conducted at Bharathi Raja Multis- peciality Hospital, Chennai, India, as per WHO opera- tional guidance to support clinical trials of herbal product [19]. Patients were unaware of the treatment assigned to them. The study protocol, case report forms, regulatory clearance documents, product related information and informed consent form were submitted to the “Institut- ional Ethics Committee” and were approved by the same. 3.2. Sample Size Calculation Sample size was calculated based on the Nomogram for standardized difference of 0.83 with 90% power to detect the difference with a two-tailed p value of 0.05 [20]. Bas- ed on this calculation, the sample size is approximately 58: i.e., 29 participants required for each arm of the study. The total sample size for this study was rounded off to 60 patients. 3.3. Randomization Sixty patients were randomized into two groups of 30 in each of placebo and drug group. Randomization was car- ried out by sequential opening of sealed opaque enve- lopes (prepared by Dr. PS Patki) containing the random group allocation previously generated using random table and opened in numerical order as the subject entered the study by the chief investigator (Dr. R. Jeyaraman). Pa- tients were free to withdraw from the study, if they so de- sired, without assigning any reason. Effectiveness of sin- gle blinding was checked by the chief investigator by questioning the patients during the course of the clinical trial. 3.4. Inclusion Criteria A total of 60 patients, aged between 30 and 65 years, who were diagnosed as suffering from BPH and who were willing to give informed consent were included in the study. The patients were categorized by the “AUA sym- ptom score index” as either mild (0 - 7 points), moderate (8 - 19 points) or severe (20 - 35 points) cases of BPH. 3.5. Exclusion Criteria Patients with diabetes mellitus, prostatic carcinoma, pro- statitis, carcinoma bladder, neurogenic bladder, stricture urethra, vesical calculus and those patients who were not willing to give informed consent were excluded from the study. Similarly patients with raised prostate surface an- tigen (≥3.9 ng/ml) were excluded from the study. 3.6. Study Procedure At the initial randomization visit, a detailed medical his- tory, with special emphasis on history of urinary symp- toms (hesitancy, straining, intermittency, frequency, noc- turia, poor flow and sensation of incomplete voiding) was obtained from all the patients. All the patients un- derwent a thorough systemic examination and digital rectal examination (DRE). Routine blood analysis, uri- nalysis and serum levels of PSA were done for all the patients. In addition, abdominal pelvic ultrasonography was done at entry and after completing the study to esti- mate the approximate prostate weight and size and to measure the post-void residual (PVR) volume. The se- verity of the urinary parameters was evaluated using AUA symptom score. All the patients were randomized arbitrarily using random table into either polyherbal group (n = 30) or placebo (n = 30). Each patient received either a polyherbal formulation or placebo in a dose of 2 capsules, twice a day with meals for two months. The outcome of each group was assessed by comparing uri- nary hesitancy, intermittency, straining during micturi- tion, urine flow, sense of incomplete micturition, fre- quency of nocturnal micturition, AUA symptom scores and PVR volume. 3.7. Primary and Secondary Endpoints The predefined primary efficacy endpoints were, evalua- tion of AUA score, PVR urine, urinary flow rate and qua- lity of life. The predefined secondary safety endpoints were evaluation of clinical and biochemical safety pro- file. 3.8. Follow-Up Patients underwent the same evaluations after treatment as were performed at baseline, regardless of their treat- ment received and outcome. Compliance to drug therapy was evaluated by asking the patients to return back the investigational product container and counting the num- ber of the remaining capsules. 3.9. Adverse Events All adverse events, either reported or observed by pa- tients, were recorded with information about severity, date of onset, duration, and action taken regarding the study drug. Relation of adverse events to the study medi- cation was predefined as “Unrelated” (follows a reason- able temporal sequence from the administration of the Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJU  R. JEYARAMAN, P. S. PATKI Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJU 160 drug), “Possible” (follows a known response pattern to the suspected drug, but could have been produced by the patient’s clinical state or other modes of therapy admin- istered to the patient), and “Probable” (follows a known response pattern to the suspected drug that could not be reasonably explained by the known characteristics of the patient’s clinical state). Patients were allowed to voluntarily withdraw from the study, if they so desired without assigning reasons. For patients withdrawing from the study, efforts were made to ascertain the reason for dropout. Non compli- ance (defined as failure to take less than 80% of the medication) was not regarded as treatment failure, and reasons for non compliance were noted. 3.10. Statistical Analysis Statistical analysis was done according to the intention- to-treat principles using GraphPad Prism version 4.03, for windows (GraphPad software, San Diego, California USA). The analysis included all randomized subjects in the groups to which they were allocated and the missing responses was evaluated using the last observation carry forward method (LOCF). Changes in various parameters were assessed for statistical evaluation using between the group analysis at entry and at the end of the study. Fisher’s exact test was used for urinary symptoms and unpaired “t” test (Independent t-test) for AUA symptom score, prostate weight and postvoid residual volume. Minimum level of significance was fixed at 95% confi- dence limit and two-sided p < 0.05 was considered sig- nificant. 4. Results Sixty consecutive patients were enrolled into the trial between December 2007 and March 2009 were randomly divided into two groups of 30 each. Mean age was 47.00 ± 10.80 years in polyherbal group and 50.30 ± 6.50 years in placebo group. In polyherbal formulation group, 12 patients were smokers, 6 were alcoholics and 17 patients were vegetarians. In placebo group, 11 patients were smokers, 8 were alcoholics and 22 patients were vege- tarians. There was no statistical difference between the polyherbal formulation and placebo groups (Table 2). Data of the 56 patients was available for analysis as four patients from the placebo group withdrew from the study due to lack of benefit to the treatment (the missing responses were evaluated using the LOCF method). The baseline values (on entry) for various parameters in the placebo and polyherbal treatment groups were not sig- nificant. There was significant reduction in the presence of urinary hesitancy in the polyherbal treatment group (8/19 patients) as compared to placebo (14/17 patients) (p < 0.01) at the end of treatment and reduction in inter- mittent urinary flow in the polyherbal treatment group (7/16 patients) as compared to placebo (19/21 patients) (p < 0.003). Polyherbal treatment group showed signifi- cant improvement in parameters such as straining during urination (p < 0.001), poor flow (p < 0.005) and sense of incomplete micturition (p < 0.02) as compared to the placebo group (Table 3). Table 2. Demographic data of patients on entry (n = 60). Parameters Polyherbal formulation Placebo No. of patients on entry 30 30 No. of patients withdrawn 0 4 Mean age (years) (Mean ± SD)47.00 ± 10.80 50.30 ± 6.50 Smokers (No. of patients) 12 11 Alcohol (No. of patients) 6 8 Diet (veg.) 17 22 Table 3. Effect of polyherbal formulation and placebo on urinary symptoms in patients with BPH. No. of patients showing symptoms on entry No. of patients showing symptoms at the end of treatment Symptoms Polyherbal formulationPlacebo p value Polyherbal formulation Placebo p value Hesitancy of urination 19 17 NS 08 14 0.01 Intermittent flow 16 21 NS 07 19 0.003 Straining during urination 26 22 NS 19 22 0.0001 Poor flow 17 15 NS 06 13 0.005 Sense of incomplete micturition 24 20 NS 13 18 0.02 Nocturia 23 25 NS 14 22 0.013 NS: Not significant; Statistical analysis: Fisher’s exact test.  R. JEYARAMAN, P. S. PATKI 161 In polyherbal formulation group, nocturia (frequency of night-time urination) was significantly reduced in com- parison to placebo group (Table 3, p < 0.013). AUA symptom score and PVR volume showed sig- nificant reductions in the polyherbal treatment group as compared to placebo at the end of treatment (p < 0.0001). Also prostate weight was reduced after treatment with polyherbal formulation as compared to placebo, though it was not statistically significant (Table 4). Assessment of questionnaires revealed an improve- ment in the QOL observed in Prostacare group as com- pared to placebo group. This was further supported by the findings which included AUA score, frequency of urination and nocturia (Tables 3 and 4). No adverse effects were reported with polyherbal for- mulation during the entire study period except slight to notable hot flushes reported by 2 patients during poly- herbal formulation therapy, which subsided at the end of the study period and did not necessitate the withdrawal of the polyherbal formulation. 5. Discussion Benign prostatic hyperplasia refers to an anatomic diag- nosis, in practice it is typically diagnosed clinically on the basis of lower urinary tract symptoms and prostatic enlargement detected on manual rectal examination or transrectal ultrasonograph [21]. Blocking androgen re- ceptor activity is a common therapeutic course for BPH [22]. This approach however, results in several side ef- fects, and most notably erectile dysfunction [23,24]. The risks and complications associated with TURP include post-operative hemorrhage, TUR-syndrome, urinary tract infection, retrograde ejaculation, bladder neck contrac- tures and urethral strictures. In the present study, polyherbal formulation was evaluated for the beneficial actions on the prostate. Cur- culigo orchioides is effective mainly on the urinary sys- tem and it is given in dysuria, and in poluria. It has 5α-reductase inhibitor activity that helps to manage prostatic enlargement [25]. Lactuca scariola exhibits antibacterial activity that may be helpful in preventing the chronic urinary infection as seen in BPH [26]. As- teracantha longifolia has antimicrobial activity that may be helpful in infections caused due to stasis of urination along with infection in the hyperplasic prostatic mass in BPH [27]. Mucuna pruriens roots are used for diseases of renal and prostatic affections [28]. It also possesses anti-in- flammatory activity that may be helpful in providing symptomatic relief in BPH [29]. On administration of Mucuna pruriens extract improvement in serum creatin- ine and urea, showing potent nephroprotective activity have been observed [30]. Parmellia perlata is active against common pathogens [31]. It contain acidic sub- stance that has been used as an antimicrobial agent espe- cially against Salmonella aureus that is implicated in mixed infections and has shown high level of resistance to the commonly marketed antibiotics. This activity stands may be helpful in providing symptomatic relief from symptoms of infections in prostatic mass, urinary bladder, and kidney due to susceptible organism [32]. Argyreia speciosa root has diuretic and aphrodisiac activities. Also it is effective in infection caused by common pathogens due to its antimicrobial activity and may be beneficial in management of BPH [33]. A. spe- ciosa possesses anti-inflammatory activity and support the rationale behind the traditional use of these plants in inflammatory conditions and may be useful in BPH [34]. Tribulus terrestris exerts strong anti-inflammatory ac- tivity, and provide beneficial effect in BPH [35]. The fruits are regarded as diuretic, tonic, and are used in painful micturition, calculus affections, and urinary dis- orders [36]. Serum luteinizing hormone may play a role in control of luteinizing hormone (LH) as in some inves- tigation, it is found with low LH in cases of BPH [37]. Tribulus terrestris shows potential increase in LH and may play role in controlling prostatic hyperplasia in BPH [38]. Leptadenia reticulata herb is used as stimulant and restorative. It is also used in dysuria, which may be helpful in BPH [39,40]. This herb has bacteriocidal acti- vity and used in inflammatory conditions of prostate [41]. Herbal formulations like Saw Palmetto blend have been used to evaluate their safety and efficacy [42]. An Table 4. Effect of polyherbal formulation and placebo on AUA symptom score, ultrasonography and uroflowmetry parameters. On entry At the end of treatment Parameters Polyherbal formulationPlacebo p value Polyherbal formulation Placebo p value AUA symptom score 14.60 ± 3.20 13.80 ± 4.60NS 9.2 ± 2.60 12.90 ± 3.800.0001 Prostate weight (gms) 34.60 ± 8.70 32.60 ± 8.30NS 32.60 ± 9.40 34.50 ± 6.60NS Post-void residual (PVR) volume (ml)85.30 ± 20.20 86.20 ± 18.20NS 52.10 ± 23.10 89.70 ± 28.300.0001 NS: Not significant; Values are indicated in Mean ± SD; Statistical analysis: unpaired “t” test (independent t-test). Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJU  R. JEYARAMAN, P. S. PATKI 162 analysis has also been carried out to evaluate costs of alternate treatments for benign prostate hypertrophy [43]. Herbal therapy has been a favored therapy for their safety. The beneficial actions observed in this study in the management of BPH could be due to the synergistic ac- tions of the potent herbs of polyherbal formulation which include 5α-reductase inhibitor activity of Curculigo or- chioides, bacteriocidal and antimicrobial activity of Lac- tuca scariola, Asteracantha longifolia, Argyreia speciosa and Parmellia perlata, anti-inflammatory activity of Mucuna prurien, Argyreia speciosa, Tribulus terrestris and Leptadenia reticulata, LH enhancing activity of Tribulus terrestris and nephroprotective activity of Mu- cuna pruriens. The study outcome was found to be beneficial in the management of moderate BPH, however, it has some limitations, like a need for larger multicentric trials to further confirm these findings. 6. Conclusion This study was planned to evaluate the clinical efficacy and safety of polyherbal formulation in BPH. Present study observed a significant reduction in the mean AUA symptom score, PVR volume and significant reduction in urinary hesitancy, intermittent flow, straining during uri- nation, poor flow, sense of incomplete micturition and frequency of night-time urination, in the polyherbal for- mulation group, which indicate clinically beneficial ef- fects of polyherbal formulation in BPH. Polyherbal for- mulation was well tolerated and safe. The beneficial clinical efficacy of polyherbal formulation in the man- agement of BPH could be due to the synergistic actions of its potent herbs. Therefore, it may be concluded that use of polyherbal formulation is clinically effective and safe in the management of BPH. However, a larger study is needed to confirm these findings. We also warn that raised PSA levels need to be ruled out before starting this drug therapy. 7. Acknowledgements Authors thank Dr. Rangesh Paramesh. MD (Ayur) for his help in this study. REFERENCES [1] H. M. Arrighi, E. J. Metter, H. A. Guess and J. L. Fozzard, “Natural History of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia and Risk of Prostatectomy: The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging,” Urology, Vol. 38, No. 1, 1991, pp. 4-8. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(91)80191-9 [2] S. J. Berry, D. S. Coffey, P. C. Walsh and L. L. Ewing, “The Development of Human Benign Prostatic Hyperpla- sia with Age,” Journal of Urology, Vol. 132, 1984, pp. 474-479. [3] J. E. Oesterling, “Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia—Medical and Minimally Invasive Treatment Options,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 332, 1995, pp. 99-110. doi:10.1056/NEJM199501123320207 [4] J. D. McConnell, “The Pathophysiology of Benign Pro- static Hyperplasia,” Journal of Anthology, Vol. 12, 1991, pp. 356-363. [5] M. H. Minsley and S. Wrenn, “Long-Term Care of the Tracheostomy Patient from an Outpatient Perspective,” ORL—Head and Neck Nursing, Vol. 14, No. 4, 1996, pp. 18-22. [6] N. K. Roberts, “The Selective Approach to Successful Stomal Management at Home,” ORL—Head and Neck Nursing, Vol. 13, No. 4, 1995, pp. 12-16. [7] T. J. Beckman and L. A. Mynderse, “Evaluation and Medical Management of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, Vol. 80, No. 10, 2005, pp. 1356-1362. doi:10.4065/80.10.1356 [8] M. T. Rosenberg, D. R. Staskin, S. A. Kaplan, S. A. MacDiarmid, D. K. Newman and D. A. Ohl, “A Practical Guide to the Evaluation and Treatment of Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in the Primary Care Setting,” International Journal of Clinical Practice, Vol. 61, 2007, pp. 1535-1546. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01491.x [9] AUA Practice Guidelines Committee, “AUA Guideline on Management of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Diag- nosis and Treatment Recommendations,” Chapter 1, 2003, pp. 1-11. http://professional.medtronic.com [10] C. G. Roehrborn, “The Potential of Serum Prostate-Spe- cific Antigen as a Predictor of Clinical Response in Pa- tients with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia,” British Journal of Urology Inter- national, Vol. 93, 2004, pp. 21-26. [11] J. A. Schalken, “Molecular and Cellular Prostate Biology: Origin of Prostate-Specific Antigen Expression and Im- plications for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia,” British Jour- nal of Urology International, Vol. 93, 2004, pp. 5-9. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2003.04633.x [12] M. J. Barry and C. G. Roehrborn, “Benign Prostatic Hy- perplasia,” British Medical Journal, Vol. 323, 2001, pp. 1042-1046. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7320.1042 [13] C. R. Chapple, “Pharmacological Therapy of Benign Pro- static Hyperplasia/Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: An Overview for the Practising Clinician,” British Journal of Urology International, Vol. 94, 2004, pp. 738-744. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05022.x [14] C. L. Eaton, “Aetiology and Pathogenesis of Benign Pro- static Hyperplasia,” Current Opinion in Urology, Vol. 13, 2003, pp. 7-10. doi:10.1097/00042307-200301000-00002 [15] T. J. Beckman and L. A. Mynderse, “Evaluation and Me- dical Management of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia,” Ma- yo Clinic Proceedings, Vol. 80, No. 10, 2005, pp. 1356- 1362. doi:10.4065/80.10.1356 [16] A. Tubaro and C. D. Nunzio, “The Current Role of Open Surgery in BPH,” EAU-EBU Update Series, Vol. 4, 2006, pp. 191-201. doi:10.1016/j.eeus.2006.07.002 [17] G. Maria, G. Brisinda, I. M. Civello, A. R. Bentivoglio, G. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJU  R. JEYARAMAN, P. S. PATKI 163 Sganga and A. Albanese, “Relief by Botulinum Toxin of Voiding Dysfunction Due to Benign Prostatic Hyperpla- sia: Results of a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study Giorgio,” Urology, Vol. 62, No. 2, 2003, pp. 259-265. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(03)00477-1 [18] G. L. Lu-Yao, M. J. Barry, C. H. Chang, et al., “For the Prostate Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): Tran- surethral Resection of the Prostate among Medicare Beneficiaries in the United States: Time Trends and Out- comes,” Urology, Vol. 44, 1994, pp. 692-698. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(94)80208-4 [19] Operational Guidance, “Information Needed to Support Clinical Trials of Herbal Products,” World Health Orga- nization on Behalf of the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases, 2005, TDR/GEN/Guid- ance/05.1. [20] E. Whitley and J. Ball, “Statistics Review 4: Sample Size Calculations,” Critical Care, Vol. 6, 2002, pp. 335-341. doi:10.1186/cc1521 [21] J. D. McConnell, M. J. Barry and R. C. Bruskewitz, “Be- nign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Diagnosis and Treatment (Clinical Practice Guideline No. 8),” In: M. D. Rockville, Ed., Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1994. [22] J. D. McConnell, “Androgen Ablation and Blockade in the Treatment of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia,” Urologic Clinics of North America, Vol. 17, 1990, pp. 661-670. [23] E. Stoner, “The Clinical Development of a 5 Alpha-Re- ductase Inhibitor, Finasteride,” The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Vol. 37, 1990, pp. 375-378. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(90)90487-6 [24] G. Bartsch, R. S. Rittmaster and H. Klocker, “Dihydro- testosterone and the Concept of 5Alpha-Reductase Inhibi- tion in Human Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia,” World Journal of Urology, Vol. 19, 2002, pp. 413-425. [25] R. N. Biswas and S. O. Temburnikar, “Safed Musali (Chlorophytum Species)—A Wonder Drug in the Tropi- cal Zone,” XIth World Foresty Conference, Canada, 2003. [26] R. N. Yadava and J. Jharbade, “New Antibacterial Triter- penoid Saponin from Lactuca scariola,” Fitoterapia, Vol. 79, No. 4, 2008, pp. 245-249. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2007.11.028 [27] R. P. Samy, “Antimicrobial Activity of Some Medicinal Plants from India,” Fitoterapia, Vol. 76, No. 7-8, 2005, pp. 697-699. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2005.06.011 [28] S. N. Yoganarasimhan, “Mucuna pruriens. Medicinal Plants of India. Tamil Nadu,” Bangalore, Vol. 2, 2000, p. 366. [29] V. N. Pandey, “Pharmacological investigations of Certain Medicinal Plants & Compound Formulations Used in Ayurveda & Siddha,” CCRAS, Department of ISM & H. Government of India, New Delhi, 1996, pp. 69-72. [30] G. K. A. Adepoju and O. O. Oduben, “Effect of Mucuna pruriens on Some Hematological and Biochemical Pa- rameters,” Journal of Medicinal Plants Research, Vol. 3, No. 2, 2009, pp. 73-76. [31] C. P. Khare, “Parmelia perlata. Encyclopedia of Indian Medicinal Plants,” Springer, Berlin, 2004, pp. 352-353. [32] M. A. Momoh and M. U. Adikwu, “Evaluation of the Effect of Colloidal Silver on the Antibacterial Activity of Ethanolic Extract of Lichen Parmelia perlata,” African Journal of Pharmacy Pharmacology, Vol. 2, No. 6, 2008, pp. 106-109. [33] L. V. Asolkar, K. K. Kakkar and O. J. Chakre, “Argyreia speciosa. Second Supplement to Glossary of Indian Me- dicinal Plants with Active Principles,” CSIR, Government of India, New Delhi, 1992, p. 87. [34] A. B. Gokhale, A. S. Damre, K. R. Kulkami and M. N. Saraf, “Preliminary Evaluation of Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Arthritic Activity of S. lappa, A. speciosa and A. aspera,” Phytomedicine, Vol. 9, No. 5, 2002, pp. 433-437. doi:10.1078/09447110260571689 [35] C. H. Hong, S. K. Hur, O. J. Oh, S. S. Kim, K. A. Nam and S. K. Lee, “Evaluation of Natural Products on Inhibi- tion of Inducible Cyclooxygenase (COX-2) and Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS) in Cultured Mouse Macrophage Cells,” Journal of Ethnopharmacology, Vol. 83, No. 1-2, 2002, pp. 153-159. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(02)00205-2 [36] R. N. Chopra, I. C. Chopra, K. L. Handa and L. D. Kapur, “Tribulus terrestris. Chopra’s Indigenous Drugs of In- dia,” U N Dhur & Sons Private Limited, Kolkata, 1958, p. 430. [37] G. L. Hammond, O. Lukkarinen, P. Vihko, M. Kontturi and R. Vihko, “The Hormonal Status of Patients with Be- nign Prostatis Hypertrophy: FSH, LH, TSH and Prolactin Responses to Releasing Hormones,” Clinical Endocri- nology, Vol. 10, No. 6, 1979, pp. 545-552. [38] M. L. Kuhut, et al., “Ingestion of a Dietary Supplement Containing Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and An- drostenedione Has Minimal Effect on Immune Function in Middle-Aged Men,” Journal of the American College of Nutrition, Vol. 22, No. 5, 2003, pp. 363-371. [39] C. P. Khare, “Leptadenia reticulata. Indian Medicinal Plants: Illustrated Dictionary,” Springer, Berlin, 2007, p. 371. [40] S. N. Yoganarasimhan, “Leptadenia reticulata. Medicinal Plants,” Vol. 2, Tamil Nadu, Bangalore, 2000, p. 322. [41] F. M. Parabia, et al., “Effect of Plant Growth Regulators on in Vitro Morphogenesis of Leptadenia reticulata (Retz.) W. and A. from Nodal Explants,” Current Sciences, Vol. 92, No. 9, 2007, pp. 1290-1293. [42] L. S. Marks, et al., “Effects of a Saw Palmetto Herbal Blend in Men with Symptomatic Benign Prostatic Hyper- plasia,” Journal of Urology, Vol. 163, 2000, pp. 1451- 1456. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)67641-0 [43] J. A. Vale, et al., “An Analysis of the Costs of Alternative Treatments for Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy,” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, Vol. 88, No. 11, 1995, pp. 644-648. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJU

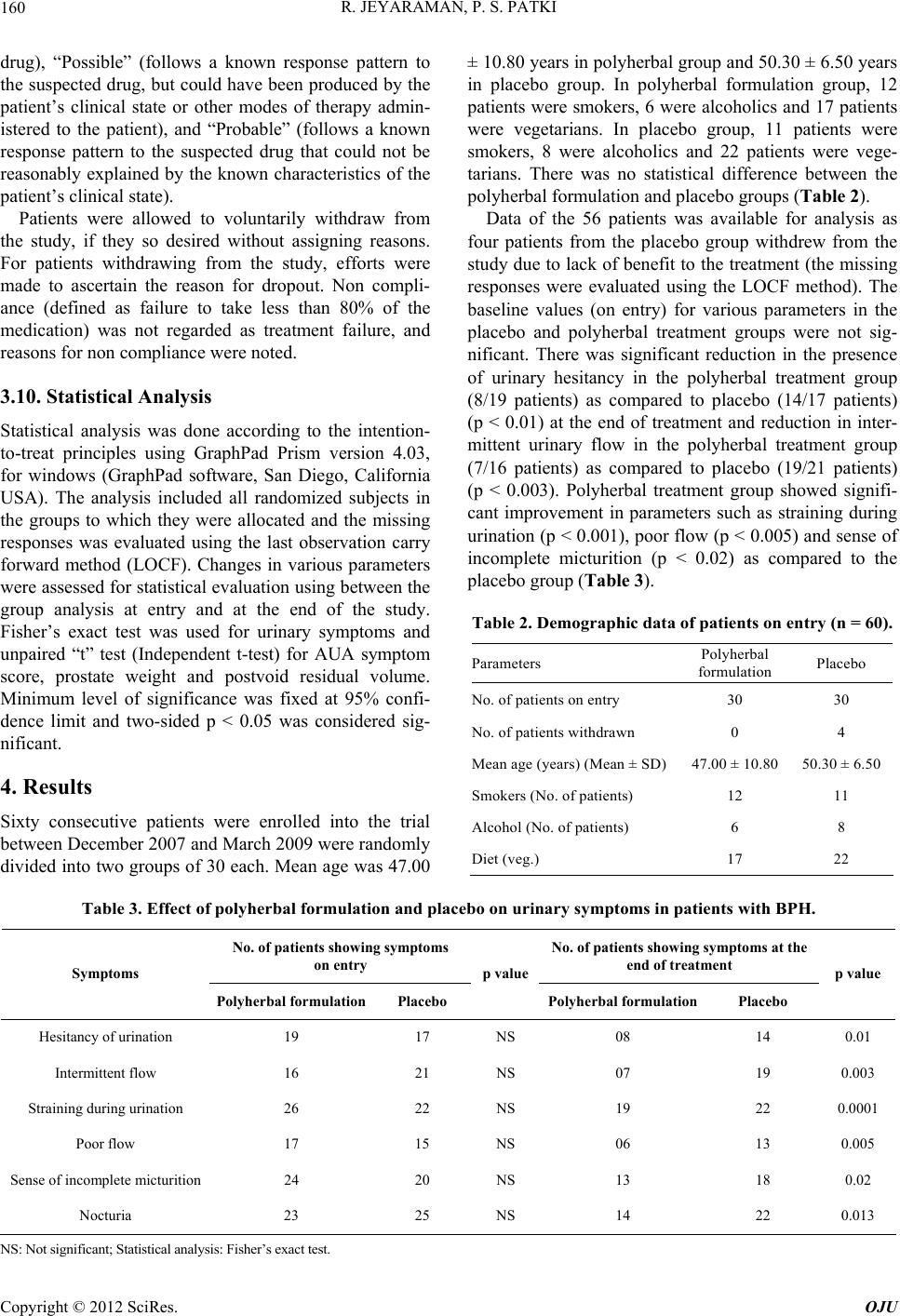

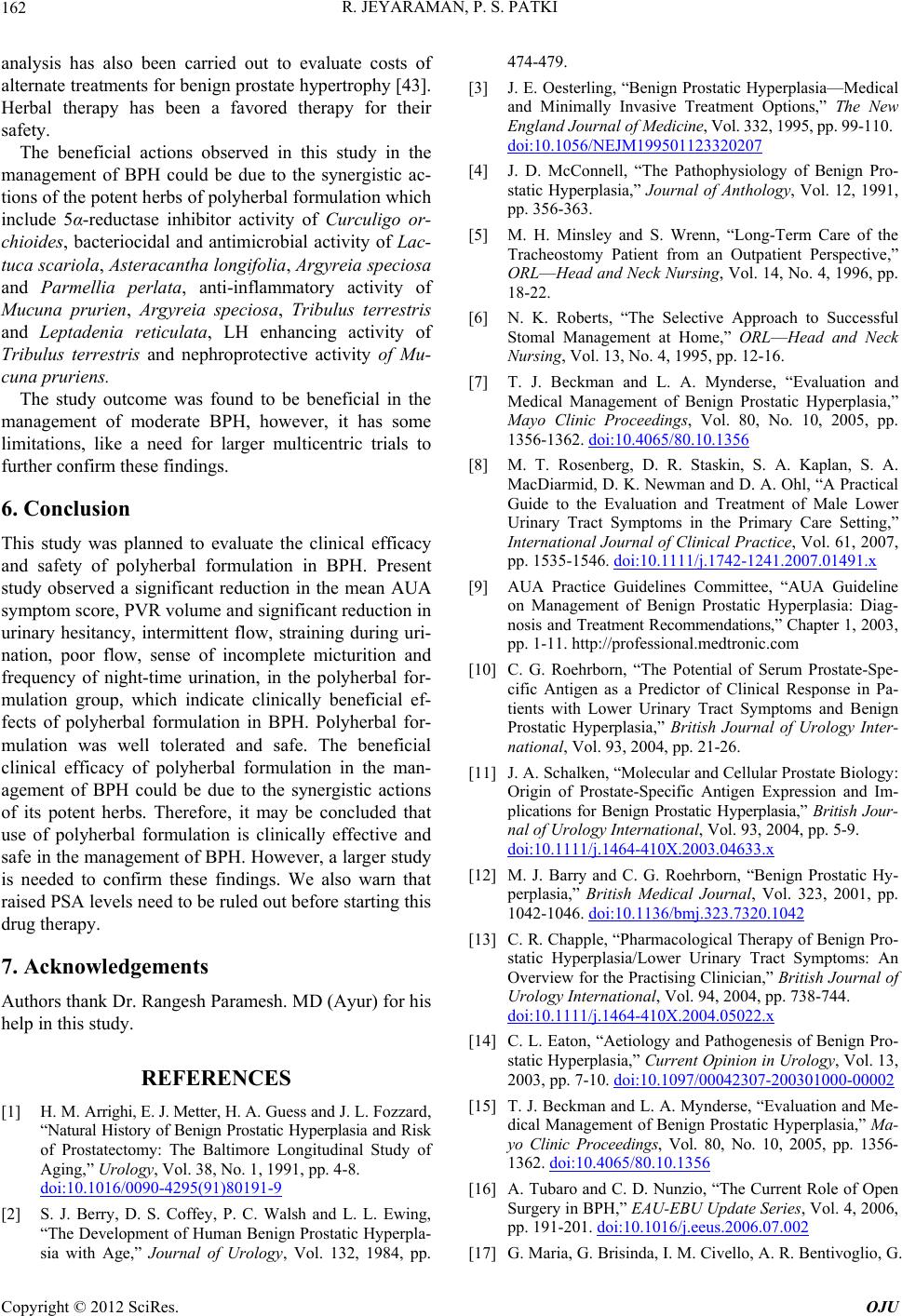

|