Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

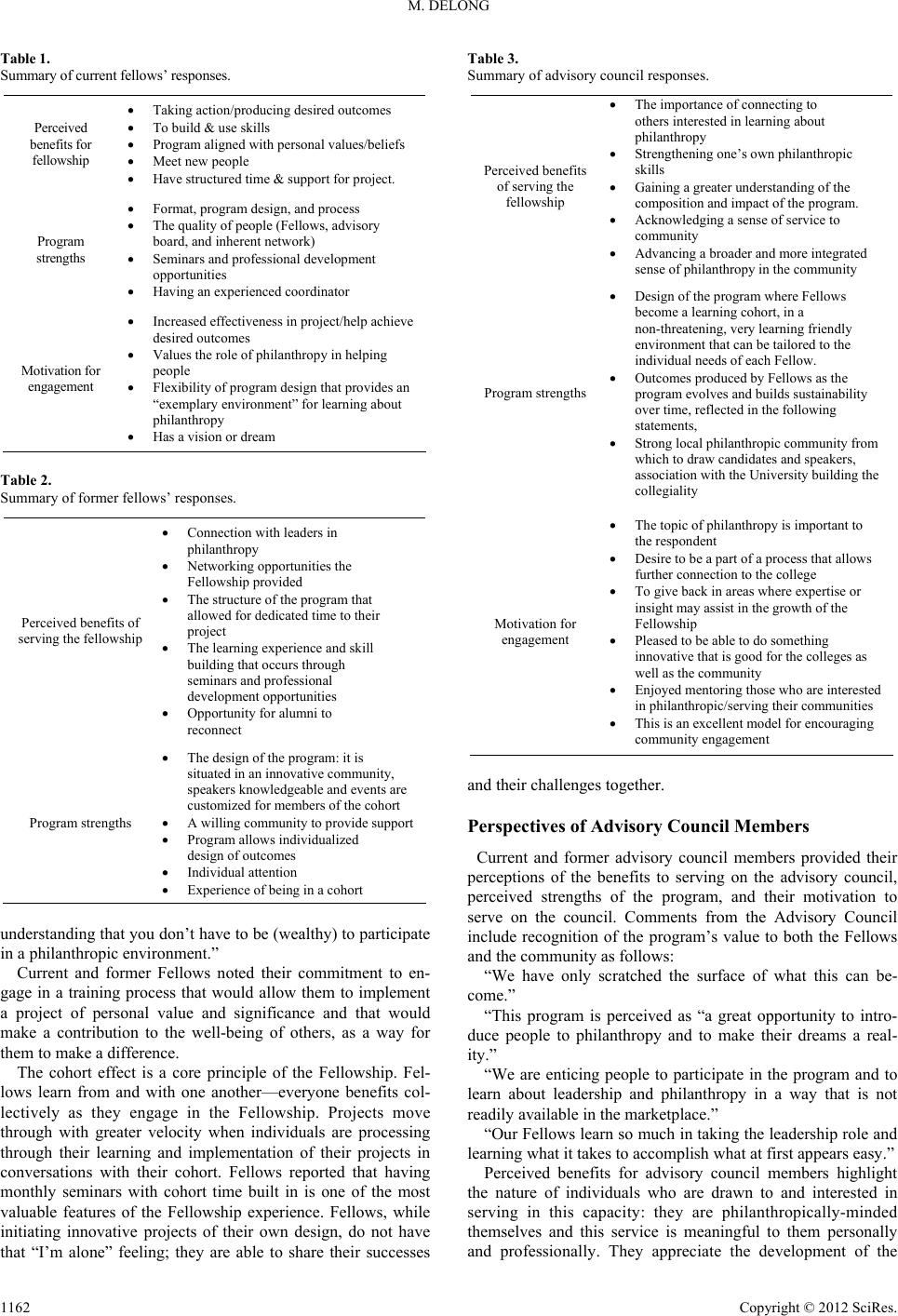

Creative Education 2012. Vol.3, Special Issue, 1158-116 3 Published Online October 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.326172 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1158 Emerging Leaders in Philanthropy—Making a Difference through the Buckman Fellowship Marilyn DeLong1, Colleen Kahn1, Jane Newell2 1College of Design, University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, USA 2College of Education & Human Development, University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, USA Email: mdelong@umn.edu Received July 3rd, 2012; revised Aug ust 5th, 2012; accepted August 20th, 2012 Fostering an attitude of giving back is a useful exercise to consider within the academic community. There are many curricula that include leadership or philanthropy, but few that provide opportunities for individuals whose academic focus is neither exclusively philanthropy nor leadership. The Buckman Fel- lowship offers a unique program for innovative, creative, and motivated university faculty, staff, graduate students, and alumni to gain leadership and philanthropic skills needed to implement projects of their own design and powered by their own passion. Housed within a university, the program cultivates emerging philanthropic leaders, with a formal evaluation of stakeholders to refine its objectives and continually im- prove its outcomes. Keywords: Philanthropy; University Setting; Leadership; Fellowship Introduction All of us experience moments, people, or events that prompt us to take action to help others. But how do we harness this energy and desire to create social impact, given our constraints of time, money and expertise? In her recent book, Giving 2.0, Arrillaga-Andreessen (2012) explains that we must find ways to harness the generosity and passions of budding philanthropists. Andreessen defines a philanthropist broadly, as anyone giving time, money, experience, skills or networks to create a better world. With this more expansive concept of philanthropy comes the notion that we all have the potential to become more philanthropic. Philanthropy should not be viewed as full time fund-raising and courting donors to write out the check with no expectation of further involvement, but instead as a way of engaging people’s expertise and passions for changing the world. The Buckman Fellowship for Emerging Leaders in Philan- thropy has just such a goal, with its year-long program of mon- thly seminars that educate a small and select cohort of “Fel- lows” in numerous aspects of philanthropy. Receiving training and networking opportunities in pertinent areas of philanthropic leadership, each Fellow engages in a philanthropic project that he or she chooses to focus on throughout the year. These pro- jects vary in topic and scope depending upon the goals of the participants, who come with a diverse range of interests and expertise in design, education and human services. Since its inception the Buckman Fellowship has been a work in progress, and now is in its eighth year of offering Fellow- ships to philanthropically minded academics. This research focuses on evaluating the structure, function, philosophic and pedagogic underpinnings of this philanthropic program. From our perspective, the social constructivist framework of the program is essential and effective because it allows for a wide range of Fellows with disparate and diverse life, academic, and project experience to grow together on a yearlong journey into the world of philanthropic leadership. Social constructivist methodology allows for and supports autonomous growth within a group of people. Fellows are selected not only for the probability of successful implementation of a project of social significance to them and their community, but also because of their commitment to obtaining leadership and philanthropic skills within a cohort of divergent learners. These kinds of outcomes are possible because of the envi- ronment created through the interaction and development of each cohort of participants over their year together. The Fel- lows work independently to design, develop, and implement their projects outside of their monthly meeting time. However when they come together they engage with one another to share their trials and errors, their ideas and questions, as well as their successes and breakthroughs. Through this process, their pro- jects evolve and begin to take form, sometimes taking a com- pletely different direction than what they first imagined. These changes over time, resulting from group process and social construction, are often noted by the Fellows as being significant learning experiences they would not likely have discovered on their own. Examples of projects highlight this process of phil- anthropic leadership development and demonstrate the com- mitment and passion of Fellows to make a difference in that part of the world that is important to them. Project Examples Buckman Fellows vary widely in their interests, academic pursuits, affiliation with the University, and leadership goals. Encompassing the fields of design, social science and applied sciences, projects also vary widely in scope, mission, and in- tended impact. The following project examples are typical of each Buckman cohort, reaching internal, local, national, and international stakeholders. All projects are initiated by specific interests with some projects a one-time event ending at a speci- fied time, while others launch a new professional pathway.  M. DELONG Connecting Children After a successful career in the apparel design field, includ- ing work in major US and Asian cities, Di sought a humanitar- ian project. She began by hosting benefit fashion shows where proceeds from sales were distributed to international adoption organizations in multiple countries. By the time she entered the Fellowship program, Di had expanded the number of organiza- tions and countries to twelve, with each organization doing philanthropic work on behalf of children. During her time as a Buckma n Fellow, Di attended a number of seminars addressing the “nuts and bolts” of philanthropic fund raising, management, and leadership, and she discovered that she could start her own 501(c)3 nonprofit corporation. Her nonprofit corporation now connects American children with children from other countries as pen pals, friends, and helpers. Di’s philanthropic reach has not only gone global, it’s been globally acknowledged as well: CNN featured Di’s work and organization the year following her Buckman Fellowship. Dignity & Humanity Roz, a social scientist, had a son who went to prison for a crime he committed. However, the inequality in the criminal justice system left her stunned and angry, and she decided, as a Buckman Fellow, she could do something about it. Roz started a foundation to help inmates learn to work through their issues and solve their own problems through a re-entry process that starts while the individual is still in prison. Her newly formed foundation distributes a newspaper free to prisons around the US. Through the paper, Roz stresses that all choices, whether good, bad, or indifferent, have consequences, while inspiring readers to make positive choices for themselves and their families. Evidence from inmate testimonials, coun- selor comments, and reduced recidivism speak to the effective- ness of the paper and the program. Trying to affect legislation that will change how people are treated when returning home, Roz sees many opportunities to help men and women succeed at living outside of prison, enabling them to complete the parole process and finding a job within 30 days. International Symposia Legacy Drew and Steve entered the Fellowship together in their joint commitment to launch an international consortium on rural design. After months of dedicated work on their vision, they held the first International Symposium on Rural Design, posi- tioning their center as a world leader in this area according to feedback from symposium attendees. Their success fulfilled one of Drew’s central goals of leaving a legac y af ter 35 years as a center director in higher education. He wanted to give back, to share with emerging leaders in his field the knowledge and wisdom he had gained throughout his career, and to empower new leadership in rural design throughout the world. Following Drew’s first seminar with the Fellowship, he commented that “what was going on here was remarkable and should be hap- pening all over the university.” His follow up evaluations con- firmed this positive view of the Fellowship. Program Structure Each year a committee selects up to ten Fellows from appli- cations of faculty, staff, graduate students, and alumni from three colleges within the University of Minnesota related to design, education and human services. The applications, solic- ited and reviewed in the spring for the following year, include a resume, a statement of interest, and a brief outline of a philan- thropic project of significance. Applicants hear about the pro- gram through newsletters, electronic announcements, but espe- cially through word of mouth from faculty members of the three colleges, and current and former Fellows who become passionate about the possibilities of the Fellowship for imple- menting long-dreamed-about projects. Many Fellows share their experiences with others they believe would benefit from participation in the interdisciplinary, philanthropically-focused leadership development program. Administrative Structure The Buckman Fellowship is a nine-month, non-credit col- laboration among multiple colleges and departments within the university. With ongoing support from the three college deans and multiple department heads, as well as directors of graduate programs within the colleges, the program generates engaged participation. Management The program director, housed and supervised within the gov- erning structure of one college, facilitates the Fellowship pro- gram, including monthly seminars, marketing and outreach, and public events. Interdisciplinary and collaborative skills are re- quired to work with multiple colleges and to respond to each Fellow throughout the implementation of their individual pro- jects, including keeping the cohort up to date with relevant information concerning events and training opportunities. Financial Resources The program is funded by an endowed gift from a former faculty member to encourage the development of philanthropic skills and leadership in students. Interest from the endowment provides revenue to spend on administration, guest speaker honoraria, public lectures, and a recognition ceremony. A sig- nificant portion of the annual budget goes to the Fellows, who are provided with a stipend to spend on initial project expenses or professional development and training opportunities, such as attending conferences, membership in the local association of nonprofits, or pursuing webinar content focused on grant writ- ing, organizational planning, strategic vision, or others. Advisory Council The Fellowship has been guided by an advisory council of community experts in philanthropy and nonprofits, Fellowship alumni, and the respective academic colleges. These volunteers meet regularly to provide input on the curriculum, recruit ap- plicants, create strategy for growth, provide contact names for seminars, and suggest or become mentors. Examples of men- toring include a council member who worked with a Fellow to establish the direction of her nonprofit. Another mentor pro- vided project direction for a Fellow to fundraise on sustainable communities. Monthly Seminars Guest presenters are engaged who are expert in the funda- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1159  M. DELONG mentals of fundraising, proposal writing, constructing case statements, as well as areas of specific interest to each cohort group. One year a number of Fellows held positions of leader- ship that required them to fundraise so one of the academic development directors responded to the specific issues of fund- raising in an academic setting. Matching cohort interests with seminar topics demonstrates social constructivist pedagogy where methods match knowledge needs of each cohort. After each seminar, Fellows have time for reflection and application of the information. Through these fundamental topics, Fellows share learning and transition into a cohort group. Group Processes The second half of each monthly seminar provides an oppor- tunity for Fellows to report on their progress, challenges, ideas and questions. Frequently, Fellows exchange information and resources and occasionally one Fellow who shares an interest in a peer’s vision will volunteer time to work on another Fellow’s project. Each monthly session includes some form of feedback loop for on-going assessment of progress toward their goals. Each Fellowship year begins with an exercise that helps Fel- lows clarify the values they hold and how these values can help guide their project. When Fellows get stuck in logistical diffi- culties, returning to the values that matter most to them can inspire continued leadership development. One Fellow recalled her precise values selected during an introductory exercise sev- eral years after her Fellowship. The one presentation that struck me the most was the (values exercise). I don’t remember all the words, but these were the ones I chose. We had to choose 10 words, and (from those 10 words) these were my final three: faith, because it’s very im- portant to me, compassion, and a balanced life. This highlights just how important the identification of these values was to the Fellow, and the impact they had on her sub- sequent efforts. Project Implementation Fellows work toward project implementation between month- ly scheduled seminars. Often Fellows need time to become comfortable deciding just how to proceed with their project. In the early part of the year their work is research-oriented, dis- covering who else is doing similar work, creating mission and case statements, deciding on funding strategies, and learning about best practices. This work is foundational for the later steps such as locating partners, and establishing communication and media requirements. Fellows often follow a common path- way, starting with a personal and theoretical project, and mov- ing towards greater visibility with measurable community im- pact. Course Website To support and facilitate on-going knowledge building a mong Fellows, an internet site was established for the cohort, separate from the informational web page. This site represents an appli- cation of the model for knowledge building (Scardamalia & Bereiter, 2006), with many students contributing to the devel- opment of one project. While Fellows do not have a single joint project, they do share their separate projects on the website and ask for critique from their cohort. In this way, Fellows contrib- ute to the knowledge generation of their own and their cohorts’ projects. Public Lecture After five years, the program expanded to include sponsor- ship of a Public Lecture for general university audiences as well as the non-profit and philanthropic communities. This affords a networking opportunity for Fellows as well as the opportunity to inform and educate the non-profit and philanthropic commu- nity about the Buckman Fellowship. Programs have included the president of a national foundation, a panel of local philan- thropic leaders to address critical issues, and a workshop with a nationally recognized expert on how to work effectively across multiple generations. The public lecture is combined with the presentation of an acknowledged demonstration of philanthropy, followed by an annual Fellowship Alumni Reunion. For one Fellow, the lecture became a momentous event: “It’s interesting, the first time that the Buckman sponsored the lecture a couple years ago, we happened to have an object that was being donated (to the university museum) at the same time. We made it a corresponding demonstration of actual phi- lanthropy that was occurring along with the lecture on philan- thropy. It was an interesting demonstration to be able to say ‘What is philanthropy? What does philanthropy look like?’” The reflections of this Fellow capture a perspective that com- bines both the theoretical and practical applications from the Fellowship experience. Her thoughts about the nature of donat- ing are further deepened by the concurrence of philosophical discussion and real-time action. Annual Recognition Ceremony Each year all Fellows from the current cohort, incoming newly selected Fellows, administration and staff for the Fel- lowship program, as well as deans, department heads, and the advisory council gather for a recognition celebration and dinner. Graduating Fellows present their projects during an informal reception period, where incoming Fellows, council members, and guests interact and ask questions. Social Constructivist Framework Social constructivist pedagogy provides the theoretical framework that undergirds the curriculum development and delivery processes of the Buckman Fellowship. At the heart of social constructivist pedagogy is the notion that we construct knowledge in groups. Ideal for the goals of the Fellowship pro- gram, this theoretical framework enables faculty, staff, graduate students, and alumni to build philanthropic skills collectively through the implementation of a self-designed project. Accord- ing to Scardamalia & Bereiter (2006) there has been an evolu- tion of thoughts about learning and how knowledge advances, suggesting that our civilization is a knowledge-creating civili- zation where the advancement of knowledge is seen as “essen- tial for social progress of all kinds and for the solution of so- cietal problems” (Scardemalia & Bereiter, 2006: p. 97). Buckman Fellows engage in a process of creating knowledge together with their cohort because they hope to find solutions to societal problems. Scardemalia & Bereiter (2006) propose a set of themes to bring about a “shift from treating students as learners and inquirers to treating them as members of a knowl- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1160  M. DELONG edge building community” (Scardemalia & Bereiter, 2006: p. 99). These themes are: Knowledge advancement as a community rather than indi- vidual achievement. Knowledge advancement as idea improvement rather than as progress toward true or warranted belief. Knowledge of, in contrast to knowledge about. Discourse as collaborative problem solving rather than as argumentation. Constructive use of authoritative information. Understanding as emergent. These themes capture the goals of a socially constructed, knowledge-building environment and provide a philosophical perspective, advocated by the faculty member who oversees the Fellowship program for each cohort of Fellows. Discussing constructivist pedagogy in the university setting, Tenenbaum et al. (2001) emphasize approaches with the objec- tive of maximizing student’s construction of their own knowl- edge and control of their own learning. Pedagogy that allows for diversity of learning and application of knowledge, while supporting and creating the context for knowledge generation is imperative. Tenenbaum et al. (2001) make a curious discovery in their examination of courses said to be operating from the social constructivist pedagogy, namely that “integrating con- structivist principals...seems to be a harder task than that of establishing and theorizing these principals” (Tenenbaum et al., 2001: p. 108). An assessment tool may be used as a benchmark for examining constructivist practices and principles in teaching and learning: 1) Ethos/environment is learner-centered; 2) Au- thenticity of content is realistic/real world versus theoretical; 3) Learner’s personal experiences are sought or offered and util- ized; 4) Learner—learner interaction is encouraged; 5) Learner “thinking aloud” is encouraged; 6) Feedback on contributions is positive and encouraged; 7) Development of thinking skills and understanding is dominant; 8) Learner contributions to tutorials is publicly valued (Tenenbaum et al., 2001: p. 96). To accomplish these goals in a typically designed classroom can be challenging and attempts to do so have often been met with a lack of evidence that students have actually engaged in constructivist practices. The Buckman Fellowship program does not involve a typical classroom setting, nor are the Fel- lows “typical” students. Each of the Fellows is highly engaged in their area of scholarship (or emerging scholarship) within the university, and each applies for acceptance into the Fellowship program for an opportunity to further develop needed skills. Buckman Fellows are highly motivated to implement a self- designed project that is important to them, and this demands pedagogy where the learner is, as outlined above, clearly at the center of the learning experience. All eight identified indices above are achievable through the environment created by the Buckman Fellowship program. The environment is intention- ally designed to facilitate a Fellow-centered ethos—this is ac- complished by individualized projects created by each of the Fellows that are then supported to implementation through consecutive seminar sessions and stimulated by on-going co- hort discussion. Subject matter derived by individual and cohort problem-solving and applied to real world problems is what guides the entire learning process, as the Fellows themselves design and execute their projects over their time while in the Fellowship (and beyond) to address emerging issues and social concerns. Ongoing interaction of each unique cohort is further facilit a te d by the structure of the seminars and group processes designed to engage Fellows with one another. Consistently, with each successive seminar, Fellows are encouraged to “think aloud” by a check-in and update to their cohort on progress made toward the completion of their projects. Emphasis is placed on what they are learning about themselves and their project in their learning process, while leadership skills are developed over the Fellowship year. The design and nature of the program encour- ages, even necessitates, Fellows’ development of critical think- ing skills and understanding as they attempt to implement their initial plans for their project. By so doing, leadership skills are further developed and shared with others through a public presentation of their Fellowship exper ience. Program Assessment & Evaluation Assessment is on-going for the program to continue to provide a relevant and meaningful experience. The program director engages with Fellows on an individual basis prior to acceptance into the program, within the first month of starting the program, mid-way through the program, and at the end of the Fellowship year. The primary forms of annual assessment include: Seminar evaluation. Fellows evaluate each session to assess the value and relevance of the seminar presenter’s material for their needs. Self-assessment. Fellows also complete a self-assessment at the beginning of their year-long Fellowship, refer to this as- sessment at mid-year check-in, and conduct a post self-assess- ment at the end of their Fellowship year to determine their growth and development. End of year evaluation. Fellows assess the overall value of the Fellowship for the advancement of their individual philan- thropic plan. Assessment of the overall program was conducted seven years after inception with the intention of evaluating effective- ness. Brief questionnaires were sent to those various stake- holders affiliated with the Fellowship: current and former Fel- lows; current and former advisory council members; deans and department heads. All stakeholders were asked the same ques- tions and responded through a qualitative, narrative response format about the perceived benefits, program strengths and motivation for engagement. The following summary highlights responses from each of the stakeholders polled. Refer to Tables 1-4. Perspectives of Fellows and Former Fellows Some Fellows recognized the opportunity to change their ho- rizons in the following comments: “It changes how you think about what’s possible.” “The experience gave me the confidence to try something new, because I had already done it (try out new things) while a Fel- low at the Buckman. The Fellowship allowed me to see that new things weren’t scary, and I could try something out. Even if it didn’t work out in the end, it was the trying that mattered.” Former Fellows named many of the same benefits as current Fellows. Several former fellows made clear declarations su ch as: “I want to invite others to pursue their passions” “I want to be effective at influencing change” “(I’m interested in) how as individuals we can take a role in helping to facilitate philanthropy, both through helping others to achieve philanthropic acts or by modeling that so there is an Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1161  M. DELONG Table 1. Summary of current fellows’ responses. Perceived benefits for fellowship Taking action/producing desired outcom es To build & use skills Program aligned with personal values/beliefs Meet ne w people Have structured time & support for project . Program strengths Format, program des ign, and pr o cess The quality of people (Fello ws, advisory board, and i nh erent network) Seminars and professional development opportunities Having an experienced coordinator Motivation for engagement Increased effectiveness in project/help achieve desired outcomes Values the role of phila nthropy in helping people Flexibilit y of progra m design tha t p rovides an “exemplary environment” for learning about philanthropy Has a vision or dream Table 2. Summary of former fellows’ responses. Perceive d b enefits of serving the fellowship Connection with leaders in philanthropy Networking opportu nitie s the Fellowship pr ovi de d The structure of the program that allowed for dedicated time to their project The learning experience and skill building that occurs t hrough seminars and professional development opport un ities Opportunity for alumni to reconnect Program strengths The design of the program: it is situated in an innovative community, speakers knowledgeable and events are customized for members of the coh ort A willing community to provide support Program a llows individualized design of outcomes Individual attention Experience of being in a cohort understanding that you don’t have to be (wealthy) to participate in a philanthropic environment.” Current and former Fellows noted their commitment to en- gage in a training process that would allow them to implement a project of personal value and significance and that would make a contribution to the well-being of others, as a way for them to make a difference. The cohort effect is a core principle of the Fellowship. Fel- lows learn from and with one another—everyone benefits col- lectively as they engage in the Fellowship. Projects move through with greater velocity when individuals are processing through their learning and implementation of their projects in conversations with their cohort. Fellows reported that having monthly seminars with cohort time built in is one of the most valuable features of the Fellowship experience. Fellows, while initiating innovative projects of their own design, do not have that “I’m alone” feeling; they are able to share their successes Table 3. Summary of advisory council responses. Perceive d b enefits of serving the fellowship The importance of connecting to others interested in learning a bout philanthropy Strengthening one’s own philanthropic skills Gaining a greater understandi n g of the composition and imp act of the p rogram. Acknowledging a sense of service to community Advancing a broader and more integrated sense of philanthropy in the community Program strengths Design of the program where Fellows become a learning cohort, in a non-threatening, very lea r n in g f ri endly environm ent that can be tailored t o t h e individual needs of each Fellow. Outcomes produced by Fellows as the program evolves and builds susta inability over time, reflected in the following statements, Strong local philanthropic community from which to draw candidates and speakers, association with the University building the collegiality Motivation for engagement The topic of philanthropy is important to the respondent Desire to b e a part of a process that allows further connection to the college To give back in areas where expertise or insight may assist in the growth of the Fellowship Pleased to be able to do some thi ng innovative tha t is good for the colleges as well as the community Enjoyed mentoring those who a re interested in philanthropic/serving their communities This is an excellent model for encouragi n g community engageme n t and their challenges together. Perspectives of Advisory Council Members Current and former advisory council members provided their perceptions of the benefits to serving on the advisory council, perceived strengths of the program, and their motivation to serve on the council. Comments from the Advisory Council include recognition of the program’s value to both the Fellows and the communit y as follows: “We have only scratched the surface of what this can be- come.” “This program is perceived as “a great opportunity to intro- duce people to philanthropy and to make their dreams a real- ity.” “We are enticing people to participate in the program and to learn about leadership and philanthropy in a way that is not readily available in the marketplace.” “Our Fellows learn so much in taking the leadership role and learning what it takes to accomplish what at first appears easy.” Perceived benefits for advisory council members highlight the nature of individuals who are drawn to and interested in serving in this capacity: they are philanthropically-minded themselves and this service is meaningful to them personally and professionally. They appreciate the development of the Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1162  M. DELONG Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1163 Table 4. University administrator s’ summary of responses. Perceived benefits of fellowship I believe this i s an outstanding p rogram that brings a sense of ethics and caring. Personally, it t ruly warms m y heart to see people involve d in the progra m. The benefit to me (as dept. head) i s that the participants seem to have a stronger connection to the college/program because I perceive the Buckman experience to be such a positive professional devel opment activity for them. It can be a transformative experience that offers incredi ble opportunities for Fellows. Program strengths Opportunity and mentoring Devote stru ctured time to projects The projects seem to reach a higher level than they would have otherwise because of the investment of the partici pants in this program. Provides a structure that lets Fellows pursue their interests in a community of peers, while giving them chances to learn what it will take to realize their goals Motivation for engagement Nurtures an innate caring for m ankind Seeds are planted and this program nurtures them to grow The results seen of past participants It can be a transformative experience that offers incredi ble opportunities for Fellows next generation of leaders, and acknowledge the challenges and commitment it takes to become a philanthropic leader. Perspectives of Deans and Department Heads To gauge perspectives of deans and department heads in three colleges and multiple departments, our evaluation invited participants to describe the perceived benefits and strengths of the program, as well as motivations for constituent participa- tion. Significance of the program to deans and department heads is seen in the ability of the Fellowship to provide a context inside which incoming Fellows are supported to design a project that is uniquely and specifically their own creation. Those individu- als who take on such a level of commitment not only impact their communities but impact their academic departments and the university as a whole through their advanced leadership skills. Conclusion Stakeholders offered many positive comments and thoughts about the future that were unique to their point of view. These responses indicate evidence of a holistic transformational lead- ership experience that is inspiring, not just for the Fellows, but for stakeholders who know them and are committed to their success: everyone benefits from an individual empowered to envision, design, and implement their unique projects. The Fellowship has been effective in fulfilling its stated goals of developing philanthropic leaders. This objective has been carefully cultivated in the socially constructed environ- ment dedicated to creating a safe place for learning where Fel- lows are free to talk through ideas and share wisdom from other perspectives. Across the board, stakeholders saw the program’s strengths in the opportunities it provided the Fellows for struc- tured training and time to devote to a project or leadership de- velopment goal. The cohort of Fellows provided an opportunity to brainstorm, discuss, analyze and decide upon options for projects. More than that, the cohort of members helped each Fellow work through unforeseen difficulties, making deep and meaningful relationships one of the most important aspects of the Fellowship. Recommendations for the longevity of this program include the following: consider expanding the program to more people/ departments within the university, as well as building strategic partnerships within and without the university with local phil- anthropic partners; highlight success stories of former Fellows to draw more awareness to the program and as a networking opportunity. Programmatic recommendations include securing stakeholders within the university, securing funding to expand the program, as well as time and money to fine tune the re- cruitment process to attract and provide programming for a competitive group of applicants. Opportunities to be explored include expanding the program beyond its current audience. For example, one administrator suggested “the Fellowship reaches a small cohort of individuals annually; can this information be more broadly disseminated to enhance a wider number of grass-roots organizations?” Build- ing long-term-growth partners and strengthening communica- tion with not-for-profit constituents in the local area was noted. Other possible opportunities include considering increased access such as through webinar delivery to reach larger groups of interested professionals. REFERENCES Arrillaga-Andreessen, L. (2012). Giving 2.0. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (2006). Knowledge building: Theory, pedagogy, and technology. In K. Sawyer (Ed.), Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 97-118). New York: Cambridge Uni- versity Press. Tenenbaum, G., Nadiu, S., Jegede, O., & Austin, J. (2001). Construc- tivist pedagogy in conventional on-campus and distance learning practice: An exploratory investigation. Learning and Instruction, 11, 87-111. |