Creative Education 2012. Vol.3, Special Issue, 1138-1149 Published Online October 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.326170 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1138 An Experience in the Prevention of HPV by and for Adolescents: A Community Randomized Trial of the Effect of Peer Health Education on Primary Prevention in a 1-Year Follow Up* Elisa Langiano1, Maria Ferrara1, Maria Gabriella Calenda2, Luciano Martufi3, Elisabetta De Vito1 1Department of Humanities, Social and Health Sciences, Campus Folcara, University of Cassino and Southern Lazio, Sant’ Angelo St, Italy 2LHA—Local Health Authority Children’s Clinic, Frosinone, Italy 3LHA—Coordination Centre of Screening Programmes, Frosinone, Italy Email: langiano@unicas.it, m.ferrara@unicas.it, calenda.mgabriella@yahoo.it, l.martufi@libero.it, devito@unicas.it Received August 30th, 2012; revised September 28th, 2012; accepted October 14th, 2012 Background: HPV is the most common sexually transmitted disease in many regions of the world. 15% was found in women aged 15 - 19 years but the highest incidence of infection from HPV can be found in sexually active adolescents: between 50% and 80% of them catch the infection within two to three years from their first sexual relationship. Methods: A community randomized trial regarding HPV infection and HPV vaccination, and sexual health was carried out, in a sample of secondary school students. Peer edu- cation intervention was carried out and 2 follows-up were carried out after the educative intervention to evaluate the effective outcomes in a 1-year follow up of the effect of peer health education on primary prevention knowledge, attitude and behaviour towards HPV. Results: The sample of 900 students, with age of 16.6 ± 1.4 ds, 34.4% of which have sexual relationships. 64.6% of students in the experimental group said that they were aware of HPV, 83.4% were aware of how it is transmitted and 71.1% knew HPV vaccination, 54.7% perceived the level of danger with significant gender-related differences the percentages increased at T1. At T0, 14.1% of females were vaccinated: T1 they were 17.5% and 19.2% at T2. The main factors associated with the students’ propensity to vaccination were: having at least one sis- ter; being in favor of vaccinations in general; knowing that the vaccine is aimed at preventing cervical cancer; and being aware that they could be infected by HPV. Conclusion: The study carried out high- lights important differences between the experimental group and the control group in terms of knowledge but, most importantly, in terms of behaviour and it proves how the application of new educational meth- ods based on the involvement of youngsters right from the initial stages of the project can help them to change their behaviour and maintain it in time. Keywords: HPV; Prevention; Adolescents; Peer Education; Evaluation Efficacy Introduction Background Research Infection from HPV is the most common sexually transmit- ted disease in many regions of the world. The persistent infec- tion with one of the tumorogenic Human Papilloma Viruses (HPV) is recognized as the necessary cause of almost all cases of Cercical Cancer Uteri (CCU). Furthermore, it is also associ- ated with at least half of all of the other forms of cancer of the lower genital tract in women and in men and a lower percent- age, from 2 to 10%, of the so-called head-neck tumours (Vac- carella, 2010; Franco & Harper, 2005; IARC, 2007; Roden, Morris Ling, & Wu, 2004; Schiffman, Castle, Jeronimo, Rod- riguez, & Wacholder, 2007; Syrjänen, 2005). Controls of infec- tion from HPV, carried out in four continents by the Interna- tional Agency for Research on Cancer (Lyon), have proved that the majority of the infection varies substantially from one population to another and ranges from 2% to 50% in women aged between 15 and 64. A higher percentage by 15% was found in women aged between 15 and 19 years of age but the highest percentage and incidence of infection from HPV can be found in sexually active adolescents, in fact between 50% and 80% of them catch the infection within two to three years from their first sexual relationship (Baseman & Koutsky, 2005; Louvanto, Rintala, Syrjänen, Grénman, & Syrjänen, 2011; Pi- ana, Sotgiu, Castiglia et al., 2011; Pieralli, Fallani, Lozza et al., 2011; Vaccarella, 2010). In Italy the vaccination against HPV is offered free of charge and on an active basis to pre-adolescents when they are twelve years of age, as defined in the Agreement between the Ministry of Health and the independent regions/ provinces dated 20th December 2007, in compliance with the indications provided by the World Health Organisation and on the basis of the regulations contained in the Guidelines of sev- eral industrialized countries (Bartolozzi et al., 2007; Friedman, Kahn, & Middleman, 2006; Agreement between the Govern- ment, Regions, Independent Provinces of Trento and Bolzano concerning “Strategies for the active offer of the vaccination *This study was supported by grants from the Italian Ministry ofInstruction University and Research (Anno 2008- prot. 20087YEJ55_002).  L. ELISA ET AL. against infection from HPV in Italy” dated 20th December 2007, World Health Organization, 2006). As far as the cohort of twelve year olds is concerned comply with the strategies of preventive vaccination but they are diversified according to Regions with regards to the other adolescent cohorts and poli- cies of co-payment. The Agreement has left the confrontation open in order to consider the opportunity of extending the offer of vaccination between 13 and 18 years of age and from the start of the campaign between Regions it offers active and free vaccination to a second cohort of over 12 years of age (the Piemonte and Valle d’Aosta Regions to sixteen years olds and Friuli Venezia Giulia to fifteen year olds) and the Basilicata Region to four cohorts (12, 15, 18 and 25 years of age). Subse- quently another 4 Regions (Tuscany in 2009 and Liguria, Marche and Puglia in 2010) extended the offer to a second cohort (Giambi, 2011). Investments in primary prevention will generate its results on a long term basis and, at the moment, it should not interfere with current cytological screening pro- grammes; on the long term, however, the very best strategies of integration of primary and secondary prevention must be as- sessed. Any possible changes in the preventive practices should be shared with health professionals and with the general popu- lations; this is even more valuable in the case of a sensitive topic as sexually transmitted diseases. In this context it is vital that adolescents also investigate into the scientific knowledge of infection from HPV and the methods of prevention. The majority of adolescents, in fact, discover their sexuality with insufficient assistance and information, often provided by in- competent and inadequate sources. Sometimes, even though the information is available it may appear to be authoritarian or it imply an opinion or, even, appear not to be compliant with the values of youngsters, their mentality and their lifestyles. An efficient way of facing this problem is represented by peer education. Since 1990 peer education has been one of the most diffused methods for the implementation of health promotion intervention amongst youngsters. It is based on an innovative course in the information/prevention process aimed at the younger groups of the population, with direct effects on the behavior of the youngsters involved, activating them as creators and protagonists of the programmed action and as witnesses and diffusers within the peer group. The prevention experience carried out during the past years has highlighted the failure of behavior change, according to which direct relations between an increase in knowledge and change in behaviors was hy- pothesized and they have always highlighted the efficiency of the model of self-empowerment that, focusing on the personal involvement of the beneficiaries of the intervention, aims at modifying risky behavior (Spizzichino, 2005). However, peer education has been considered a potentially efficient strategy in order to launch intervention finalized at the prevention of sexu- ally transmitted diseases in youngsters; the influence that youngsters can have on the sexual behavior adopted by their peers has been documented (World Health Organization, 2007; Hoffman, Sussman, Unger, et al., 2006). This represents a channel of communication through which well trained and mo- tivated youngsters undertake educational activities with their peers (Adamchak, 2006; United Nations Population Fund and Family Health International, 2005). Peer education is frequently carried out as it has been designed in a simple and convenient manner to transmit information with a very broad reference target, in a simple and economic manner. In reality, if per- formed correctly, peer education requires attentive planning, coordination, supervision and resources (Adamchak, 2006). Research Significance The positive assessment, not only on a short term but most of all after one year, shows if peer education, an educational method based on the involvement of youngsters’ right from the early stages of the project, can be applied in order to modify their behavior and maintain it in time. Research Framework The main objective of the research is to: evaluate the effec- tive outcomes in a 1-year follow up of a randomised commu- nity test of the effect of peer health education on primary pre- vention knowledge, attitude and behaviours towards HPV among adolescents with reference to previous documents from the same test (Ferrara, Langiano, & De Vito, 2012). Therefore the complete investigation will be presented with the objective of promoting adhesion to the primary and secon- dary prevention programmes and providing information on the characteristics, potentials and limits of the vaccination. The target chosen is represented by secondary school students due to the high percentage of individuals belonging to the adoles- cent age group (Baseman & Koutsky, 2005; Louvanto, Rintala, Syrjänen, Grénman, & Syrjänen, 2011; Piana, Sotgiu, Castiglia et al., 2011; Pieralli, Fallani, Lozza et al., 2011; Vaccarella, 2010) and because, not having participated in the active offer of vaccination through a greater awareness, they may submit themselves spontaneously (Do & Wong, 2012). Method Between September 2010 and June 2012, we carried out in- vestigations into KAB (Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviour) in a sample of secondary school students, on infections from HPV and vaccinations and their sexual habits. Peer education intervention was carried out and 2 follow-ups were carried out after the educative intervention, the first after four months (T1) and the second after one year (T2). Samples The schools involved formed our sample and were chosen on the basis of contacts that the researchers involved have with members of the school boards. Researchers from the Laboratory of Hygiene of the Depart- ment of Human and Social Science and Health from the Uni- versity of Cassino and Southern Lazio (Central-Southern Italy), sent an invitation to participate in the project to members of the Boards of two Technical Colleges and two Secondary Schools in Cassino but only the Secondary School specialising in Clas- sical Studies and the Secondary School specialising in Scien- tific Studies, academic institutions with a long and deep-rooted history of collaboration with the University, in the execution of health promotion activities among adolescents (Ferrara, Gentile, Merzagora et al., 2004; Ferrara, De Vito, Langiano et al., 2006; Ferrara, Langiano, Di Tiene et al., 2010; La Torre, De Vito, Martellucci et al., 2002; La Torre, De Vito, Capelli et al., 2003). In order to guarantee maximum collaboration of teachers in the investigation, researchers contacted the board of directors of each of the two schools before carrying out the educational intervention, illustrating all phases of the project ranging from the objectives, the methods and the execution times. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1139  L. ELISA ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1140 The study was approved by the boards of each of the schools involved as well as by the parent representatives who received information regarding the contents of the programme, the method used and the layout of the study. with more detailed information on research and on how to fill in the form. Procedures Randomization process has been performed according to re- vised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomised trials (Kenneth, Schulz, Altman, et al., 2010). Through a random extraction, a sample of 900 stu- dents was selected, belonging to both of the colleges. The pre-questionnaire was handed out by the peer educators to all of the students in December 2010 (T0) during normal school hours. Educational intervention in the experimental sample was car- ried out between February and May 2011. This sample represents 64.3% of the total students population attending the colleges involved. Between June and November 2011 (T1) the peer educators handed out the post-questionnaire to students belonging to the experimental group and to students belonging to the control group and also belonging to the control group. By using this extraction method based on cluster randomisa- tion, the research team assigned the experimental condition to 323 students, including execution of peer education interven- tion, and the control condition to 577 students (Figure 1). In June 2012 (T2) both groups were given the post intervene- tion questionnaire (1-year follow up). In order to check the efficiency of the intervention of peer education with regards to the change in opinions and beliefs on HPV, questionnaires were distributed before and after the in- tervention by the peer educators (T0 basic, T1 first follow up, T2 1 year follow up) to the experimental group and to the con- trol group. In order to avoid identification of the students and to guaran- tee their anonymity, they were asked not to indicate their names but they had to make up their own nickname. The nickname used had to be the same in the pre-question- naire and in the post-questionnaire; this allowed researchers to proceed with pairing of the three questionnaires. Families of the students were also informed through a pres- entation letter illustrating the objectives of the study and expla- nations related to the questionnaire were provided. Furthermore, it contained contact details of the researchers of the Laboratory of Hygiene of the University of Cassino and of Southern Lazio who were available for any clarifications necessary. The teachers were invited to leave the classroom during compilation of the questionnaire and they were not involved in the distribution and collection of the questionnaires. Questionnaires Informed consent, necessary to participate in the study, was achieved by parents for the students of less than 18 years of age and by the students themselves if 18 years of age or more through the use of a specific form. A four page questionnaire was developed. The majority of the items were structured in a defined set of possible answers or within the control boxes (often/always/sometimes/never or yes/no/don’t know). The questionnaire was made up of 30 closed questions, divided up into different topics and classified Before giving them the questionnaire, students were provided Figure 1. The CONSORT flow diagram on randomization process.  L. ELISA ET AL. in three different sections: 1) Social-demographic section; including age, sex, city of residence, number of brothers/sisters, level of education of parents and their profession. 2) Section related to infection from HPV and its vaccination; necessary for identification of the knowledge possessed with regards to HPV and its vaccination, also extremely important for purposes related to findings of behaviour compared with execution of the vaccination. 3) Section dedicated to the assessment of attitudes and prac- tices with regards to the topic of sexual health. The questionnaires have been tested through the execution of a pilot study carried out on a random sample of adolescents from a secondary school. The pilot study made sure that the questionnaires were perti- nent and acceptable for the participants and that the level of the language was appropriate. Following the pilot study, small variations were made to the layout of the questionnaire. Peer Education Intervention Peer education intervention consists of: 1) Selection and training of 15 Peer Tutors chosen from among the students attending the first year classes of the Teacher’s Training Degree course in Social Politics and Social Services from the University of Cassino and Southern Lazio. 2) A range of meetings for teachers acting as health refer- ences for the schools involved, during which the objectives of the research were explained and discussed; the methods of enlisting of the sample were explained, the experimental group on which intervention was to be carried out and the methods of execution and the expiry date defined. The students that showed greatest interest were invited to take part in training courses as Peer educators including a range of meetings and workshops held by researchers from the Labo- ratory of Hygiene of the University of Cassino and of Southern Lazio, by the doctor in charge of programmes from the Coor- dination Centre of screening and by the doctor in charge of paediatric consultancy at the Local Health Authority (ASL) of the province of Frosinone. Training destined for peer educators was developed, organ- ised and managed by the researchers themselves and was char- acterised by the obligation to attend. In order for a peer educator to be classified as such, he must have knowledge, skills and competence (Adamchak, 2006; United Nations Population Fund and Family Health Interna- tional, 2005; Supporting Community Action on AIDS in De- veloping Countries, 2006; Pellai, Rinaldin, & Tamborini, 2002). The training course was based on topics such as: peer educa- tion, papilloma virus, the methods of transmission of the virus, HPV vaccination, HPV test, Pap test, risky behaviour, safe behaviour, consequences of the infection, symptoms and treat- ment. The course included team work to face topics such as facilitation, communication, basic consultancy, methods of information (presentation, communication and personal devel- opment, empathy and non judgmental attitudes, assertiveness, self-esteem, group dynamics, sensitivity, general topics, so- cial-cultural topics and finally economic trends). The training intervention proposed was divided up into two sessions, each one lasting 2 hours. Activities were coordinated by the research managers who identified the method of intervention in classrooms and they defined the methods and articulation of intervention. Intervention carried out in order to prevent infections from HPV has provided information on the principles that character- ise health education and medical education, focusing on the adoption of risky behaviour by youngsters compared with the problem in question. The topics faced specifically refer to: epidemiologic data re- lated to diffusion of the infection from HPV in Italy and throughout the world; the methods of transmission of the virus; HPV vaccination, HPV test, Pap test, risky behaviour and safe behaviour. At the same time as presentation of the topics mentioned above, the importance of the involvement of adolescents in planning prevention initiatives, with the objective of motivating youngsters to active participation in the subsequent phases, was also highlighted. During the intervention, in fact, the youngsters were offered a whole range of techniques to facilitate communication, circle time and brainstorming, for example, concrete examples on how to handle class discussions, building discussion groups with them (Landi, 2004; Croce & Gemmi, 2003). During im- plementation of the intervention the peer educators, working on the information provided to them, resumed the topics several times, they stimulated adolescents to interact through informal discussions and comments and they replied to the questions asked. The contents of group discussions was guided, providing the peer educators with specific indications on how to pilot the group itself. The teachers that attended the intervention stimu- lated students to participate. The latter took part in a training meeting before the start of the activities included in the project and that provided them with information on their contents and characteristics. Through a whole series of meetings the peer educators inter- acted with the teachers with the objective of monitoring project development, its implementation, the difficulties encountered and assessing efficiency. The surveillance activities and the exchange of experience, as well as the introduction of corrective measures allowed for continuation of the programme in an even more efficient man- ner. Finally, an assessment process was carried out in order to collect quality and quantity information on the learning courses in which the students were involved during the various stages of the intervention, to measure efficiency and effectiveness or to prove the validity of the intervention itself (Barreto, 2005; Derzon, Sale, & Springer, 2005). The final assessment of the intervention was therefore developed through two follow-ups, aimed at checking the permanence of the information that had been transmitted “by the youngsters to the youngsters” through the peer-to-peer channels and, most importantly, the changes in their behaviour (Croce & Gemmi, 2003; Goodstadt et al., 2001). Analysis of Dat a The answers were analysed through the use of descriptive statistics. Continuous data, normally distributed, was described through the use of averages and standard deviations. However category data was described using frequencies and percentages and the groups (mothers vs. fathers among parents; women vs. men among students) were compared according to cases using Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1141  L. ELISA ET AL. χ2 or the Fisher test. All of the analyses are two tail values and the p value equivalent to .05 have been considered as significant. The Odds Ratio (OR) and the intervals of confidence equivalent to 95% (CI) have been calculated to measure asso- ciations between the selected factors, chosen on the basis of revision of the reference literature and the inclination of stu- dents to be subject to vaccination against HPV. The OR’s have been achieved through the use of multiple lo- gistic regression, fixed by: Age, sex and religion of the student; education and presence of the parents; six of their brothers and/or sisters; Average age of the first sexual relationship; the presence of two or more partners; use of a condom. The analyses have been carried out using Epi Info (version 3.5, 2008). Results and Discussion In T0, the sample consisted of 900 students, in T1 650 indi- viduals were interviewed and 617 in T2. The T1 sample con- sisted of: 323 individuals belonging to the experimental group 577 individuals belonging to the control group. The experimental group as well as the control group took part in both of the surveys. During the first follow-up, carried out after 4 months, 250 students had been lost. The reasons for non completion of the study in question were: Withdrawal from school (n = 7) School absence (n = 243). In June 2012 (T2), however the general sample consisted of 617 students (287) from the experimental group and 330 from the control group (5 had withdrawn from school and 28 due to school absence). The rates of withdrawal were similar (p < .05) in the two fol- low-ups and in both groups. Description of the Sample During the basic time (T0) the average age of the sample was 16.6 ± 1.4 SD, with no drastic differences between the individ- ual of the experimental groups and the members of the control groups. Furthermore, within the two groups, no significant differ- ences were found in terms of distribution between sexes (70.8% in girls from the experimental group; 65.7% in the control group). 1.7% of the students that did not indicate their sex were ex- cluded from the gender analysis but included in the analysis related to sexual experience. Social-Demographic Section The demographic data of students, including sex, age, num- ber of brothers/sisters, religion, level and profession of their parents, are indicated in Table 1, from which we can see that the fathers are older than the mothers: respectively 49.3% and 33.2% were ≥50 years of age. The majority of participants of the sample had just one brother/sister (46.4; 55.8% brothers, 59.3% sisters); 39.9% have at least one sister or brother of more than 18 years of age. Table 1. Distribution of students by social-demographic factors. n % Total sample size 900 100 Gender Male 298 33.1 Female 587 65.2 Missing 15 1.7 Means age ± ds 16.6 ± 1.4 ds Religion Catholic 780 86.7 Atheist 94 10.4 Other 5 .6 Missing 21 2.3 Number of siblings 0 387 43 1 418 46.4 2 70 7.8 >3 25 2.8 Educational level of fathers Primary school 7 .8 Junior high school 74 8.2 High school 455 50.5 College Degree 337 37.5 Missing 27 3 Educational level of mothers Primary school 11 1.2 Junior high school 61 6.8 High school 481 53.4 College Degree 332 36.9 Missing 15 1.7 Work activity of fathers White collar worker 263 29.2 Self employed 317 35.2 Other 298 33.1 Missing 22 2.5 Work activity of mothers White collar worker 210 23.3 Housewives 235 26.1 Other 435 48.4 Missing 20 2.2 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1142  L. ELISA ET AL. Personal Knowledge of HPV and Attitude to Vaccination: The Experimental Group This study, carried out on the middle-high class of the popu- lation of a small area of central Italy, highlighted the fact that adolescents still have many gaps with regards to knowledge of infection from HPV and prevention of this infection through vaccination. This can be found in data related to the experi- mental group, with reference to T1, and from data related to the control groups of T0, T1 and T2. In fact, in the basic time, the majority of students of both sexes (64.6%; 95% CI 58.9% - 70.0%) have stated that they are aware of the HPV virus, with statistically significant differ- ences in terms of gender (female 73.6% vs. males 43.0%; p < .01). In the first post-questionnaire statistically significant differences in terms of gender were confirmed, the percentage of males that state that they are aware of HPV (65.0%; p < .01) has increased, as an increase in the percentage of male and female students has been registered (84.4%, 95% CI 79.3% - 88.7%). At T1 the percentage related to knowledge increased drastically (91.3%, 95% CI 87.3% - 95.9%) in both sexes. These results were in line with the results achieved in similar students on a national and international level (Di Giuseppe, Abbate, Liguori et al., 2008) proving the incisiveness of the technique of peer education in the expulsion of information guided by the “peer to peer” channel. Furthermore, our data confirms how the application of new educational methods based on the involvement of youngsters right from the begin- ning of the project may help to change their behaviour and it in time (De Santi, Ranieri Guerra, Morosini et al., 2008). The methods of execution of peer education intervention have maintained a spirit of dynamism and adaptation according to the class context (dispersion or cohesion), favouring a direct and communicative attitude by the peers, mainly based on rela- tional aspects (Nizzoli & Colli, 2004). The peers have therefore acted as facilitators of communica- tion, despite having to handle a spatial and relational context passed down by academic teaching; as far as the children are concerned, they have welcomed with pleasure the possibility of using moving space, therefore allowing themselves to be stimulated by curiosity, spontaneity and spirit of initiative (Boda, 2001; Marmocchi, 2004). Furthermore, 67.4% of students who had already had sex were aware of HPV, without any significant differences in terms of sex and age. There were no significant differences related to sex not even between those who stated that they were aware of HPV with respect to the level of danger perceived (54.7%; 95% CI 48.9% -60.4%; 75.8% females vs. 40.2% males; p < .05) and how the virus is transmitted (83.4%; 95% CI 78.8% - 85.7%; 76.0% females vs. 34.0% males; p < .01). In the post-questionnaires of T1 and T2, the percentage of those who recognised the seriousness of the effects on health caused by infection from HPV increased and reached, respec- tively, 64.8% (95% CI 58.5% - 70.7%) and 72.0% (95% CI 65.5% - 74.9%). An increase in the percentage that stated that sex was the main method of transmission of the virus was also registered (T1; 89.1%, CI 84.6% - 93.7%) and (T2; 96.2%, CI 89.5% - 99.8%) without registering differences due to gender. Only 14.7% of the individuals interviewed were aware of the risk of infection from HPV (95% CI 10.9% - 19.2%) and if this is divided up by gender, the percentage related to the perception of risk is much higher in women (90.7% females vs. 49.3% males; p < .01), as confirmed by the post-questionnaires (T1-24.7%; 95% CI 18.6% - 29.9%; 82.1% females vs. 44.9% males; p < .01; T2-29.8%; 95% CI 22.7% - 34.8%; 83.2% fe- males vs. 46.8% males; p < .01). Therefore a good part of the sample appears to underestimate the possibility of contagion of the virus, consequently, they underestimate the anti HPV vaccination as an important means of prevention. This thought becomes an important indication for future programmes of information and training on the Papilloma Virus that should be developed with the objective of increasing the awareness of using the vaccination against the Papilloma Virus to provide protection against the infection and, therefore, from CCU. In fact, with regards to knowledge related to vaccination, 71.1% (95% CI 64.9% - 77.4%) of students in T0, 83.9% (95% CI 75.6% - 87.8%) of students in T1 and 85.8% (95% CI 79.5% - 91.7%) in T2, were aware of the fact that it also vents CCU; once again, girls (72.4%) were the ones most aware of this compared with boys (47.8%) (p < .01), as can be seen in other studies (Sopracordevole, Cigolot, Lucia et al., 2009). Apart from their families (40.0%; 95% CI 33.2% - 47.1%), youngsters have received information related to HPV from school (21.5%; 95% CI 16% - 27.7%), from friends (19.0%; 95% CI 13.9% - 25.1%) and from the family doctor (17.1%, CI 95% 13.2% - 2.1%). Students state that they need more information on the anti HPV vaccination (86.5%; 95% CI 81.9% - 90.3%); a need that is much higher in girls (75.2%, p < .01). More than half of the individuals interviewed (54.6%; 95% CI 49.0% - 60.1%) would like to receive further information from discussions with experts; in particular this has been stated by girls (69.4%, p < .05). A small, yet still important percent- age of boys (13.5%), do not believe that they need further in- formation as they are not interested in this subject. With the first administration, more than half of the students (52.6%; 95% CI 48.4% - 60.6%), mistakenly believe that the vaccination against HPV also provides protection from other sexually transmitted infections; this belief is even higher in women (33.7%, p < .01). In T1 this percentage is less, equivalent to 32.9% (67.9%; 95% CI 63.4% - 70.8%); while in this regard boys are still in- correctly informed (22.9%, p < .01). One year after the inter- vention (T2) the percentage generally reached 28.9% (95% CI 23.4% - 33.8%). In the pre-questionnaire, 14.1% of the girls stated that they had been subjected to the vaccination; 71.8% of them belonged to the group of girls who had never had sex. The educational intervention carried out has had a positive effect on vaccina- tions; in fact the percentage of people vaccinated increased from 14.1% to 17.5%, as can be seen from the post-question- naire T1 and 19.2% in T2. Significant associations have emerged between being sub- jected to the vaccination and the medium/high level of maternal education (84.6% p < .05) and the presence of a sister aged between 10 and 16 (36.1%, p < .01). Approximately 70.0% of the female students involved in the pre-questionnaires, 82.3% in the post-questionnaires and 89.5% in the final follow-up are aware of the fact that the HPV vacci- nation should be administered before the start of sexual activi- ties; a much lower percentage (55.6%) has been registered in male students in the pre-questionnaires, with a slight increase in Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1143  L. ELISA ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1144 the post-questionnaires (T1 64.6% and T2 69.9%) with signifi- cant differences in terms of sex (p < .01). The fear of contraindications from administration of the vac- cination is one of the main reasons for resistance to the vacci- nation (10.5%, 95% CI 7.5% - 14.5%) followed by the absence of knowledge on the objectives of the vaccination itself (9.0%, 95% CI 6.2% - 12.7%). After the educational intervention these percentages fell (re- spectively 8.0%; 95% CI 5.2% - 11.7% and by 7.7%; 95% CI 5.1% - 11.3%) and confirmed in the final follow-up. From an analysis of the pre-test, 41.6% (95% CI 34.7% - 48.7%) of the girls expressed a desire to administer the vacci- nation against HPV, a percentage that reached 59.7% (95% CI 52.6% - 64.6%) in T1 and 67.6% (95% CI 63.4% - 71.4%) in T2. Prevention of Cervical Cancer has represented the most inci- sive factor on the decision to be subjected to this (at T0 the percentage is 38.6%; 95% CI 33.3% - 44.1%; however, in the post-questionnaires the percentage reaches, respectively, 66.6% (95% CI 52.6% - 64.6%) in T1 and 76.5% (95% CI 71.5% 77.1%) in T2. From the survey carried out, we can see how important it is that information related to prevention of infections from HPV should be supplied during the 10 and 13 age group. With re- gards to this aspect, a percentage difference between the pre-questionnaires and post-questionnaires has been found (re- spectively 39.7%; 95% CI 34.1% - 45.4% and 43.9%; 95% CI 37.5% - 50.3%); furthermore, a statistically significant differ- ence in terms of sex has been found (43.8% females vs. 29.8% males, p < .05). The low percentage of female adolescents that consider themselves to be potentially at risk of contracting HPV should be due to the low perception of the high diffusion of this infection, as previously proved in other studies (Caskey, 2009; Chan et al., 2009). As far as male students are concerned, apart from having identified a lower level of knowledge with regards to the HPV virus, a high diffusion of thought according to which the males believe that the infection does not involve them, has been found. This is not surprising as the Papilloma Virus and the vacci- nation itself have been publicised almost exclusively with re- gards to the prevention of cervical cancer and it is still to be clarified if males should be vaccinated. Not even knowledge represents a sure indicator of behaviour change in health care, however it is an essential and vital pre- supposition to identify the age group that requires the most information (Di Giuseppe, Abbate, Liguori et al., 2008; Piana, Sotgiu, Castiglia et al., 2011; Pieralli, Fallani, Lozza et al., 2011). Table 2 provides the results achieved from an analysis of data related to knowledge, behaviour and attitudes of the stu- dents and the differences found between the two groups (ex- perimental and control) with reference to the pre-questionnaires and post-questionnaires in T0, T1 and T2. This shows that knowledge as well as attitude related to the vaccination in- creases in the follow-up after 4 months and continues to in- crease in the 1-year follow-up. This would lead us to presume that peer intervention has stimulated students to acquire more Table 2. Main differences in the knowledge of and attitude to HPV infection and HPV vaccination between experimental group and comparison group. Intervention group (323) Comparison group (577) T0 (%)T1 (%) T2 (%) T0 (%) T1 (%) T2 (%) *p Knowledges of HPV infection and vacci nation Have you ever heard about HPV? (Yes) 64.6 84.4 91.3 72.6 73.9 74.3 .02 Do you think that HPV could be dangerous? (Yes) 54.7 64.8 72.0 64.5 63.8 62.9 NS How is HPV infection transmitted? (Sexually) 83.4 89.1 96.2 80.3 81.6 82.1 NS Do you think HPV infection might concern you? (Yes) 14.7 24.7 29.8 20.1 19.9 20.3 .05 Have you ever heard of HPV vaccination? (Yes) 71.1 83.9 85.8 72.2 73.7 72.9 .001 Which is the main aim of HPV vaccination? (Prevention of cervical cancer) 52.6 67.9 77.8 49.2 49.9 47.7 .01 When is HPV vaccination recommended? (Before beginning of sexual activity) 68.1 79.2 90.1 73.3 74.6 77.3 .02 Personal attitu des towards HPV vaccination (Only female) (225 = 70.8%) (374 = 65.7%) Have you been vaccinated? (Yes) 14.1 17.5 19.2 11.9 12.1 12.3 .03 Do you want to have HPV vaccination? (Yes) 41.6 59.7 67.6 40.1 40.5 40.9 .001 If you wanted to have HPV vaccination, what would be your reason? (Prevention of CCU) 38.6 66.6 76.5 35.4 36.7 38.3 .03 Note: *Significant differences in knowledge, attitude and behaviour between intervetion and comparison group (p); NS: non significant.  L. ELISA ET AL. information and, in any case, has made them much more sensi- tive to the topic (Barreto, 2005; Derzon, Sale, & Springer, 2005). Table 3, however, illustrates the results of the analyses of logistic regression. From this analysis we can see how the level of education of parents, the religion of the students and the fact that they have a sister are all factors associated with greater inclination to the HPV vaccination. Apart from this a significant association has been found be- tween the level of education of the mother and the fact that they individual has already been vaccinated (medium/high level of maternal education 84.6% (OR = 3.7; 95% CI: 1.9 - 7.1; p < .05). Furthermore, it was established that the students that de- clared a religion other than Catholic or atheist, are less willing to be subjected to the HPV vaccination (OR = 0.6, CI 95% 0.4 - 0.9, p < .05) compared with Catholics. The inclination to be subjected to the HPV vaccination is as- sociated with other factors such as: the sex of brothers/sisters (the presence of at least one sister aged between 10 and 16); 36.1%, OR = 1.6, CI 95% 1.4 - 1.9, p < .05); inclination in general to vaccination (OR = 13.1, 95% CI 9.7 - 17.8, p < .05); and knowing that the HPV vaccination aims at preventing cer- vical cancer (OR = 3.3, CI 95% 2.6 - 4.1, p < .05). Among the students aware of the fact that infection from HPV can affect their own state of health, greater inclination to vaccination against HPV has been registered, regardless of the sex considered: males (OR = 3.2; 95% CI: 2.6 - 4.1; p < .05); females (OR = 2.8; 95 % CI: 1.6 - 3.9; p < .05). Control Group In the control group no substantial differences have been reg- istered with regards to knowledge among T0, T1 and T2. The students included in the control group state that they are aware of HPV in a percentage of 72.6% (95% CI, 67.8% - 77.9%) in T0. The results of T1 are very similar (73.9%, 95% CI, 65.9% - 82.1%) and also of T2 (74.3%, 95% CI, 68.8% - 81.0%). In this case also there is a high percentage of students in the pre-questionnaire (80.3%) and also in the two post-ques- tionnaire (81.6% at T1 and 82.1% at T2) that identify sex as the main method of transmission of the HPV virus. As far as the question regarding the perception of risk is con- cerned, we can see how, in T0, 79.9% (95% CI, 74.6% - 84.8%) of the individuals interviewed do not believe to be at risk of infection from HPV. The situation is almost identical in T1 and in T2; in reality the percentage reaches 80.0% in both of the follow-ups. One aspect that should be underlined is that almost half of the students from the control group (48.6%) were aware of the fact that HPV can be the cause of the onset of cervical cancer, a percentage that almost superimposes the one registered in the T0 experimental group (51.9%). Finally, 11.9% in the pre- questionnaires and 12.1% and 12.3% respectively at first follow up and last follow up have stated that they have been vacci- nated. Sexual Behaviour: The Experimental Group 34.4% (95% CI, 28.9% - 40.3%) of the students stated that Table 3. Associations between selected socio-demographic factors, personal beliefs and attitudes of students to vaccinating themselves against HPV1. Independent variables OR (95% CI) Educational level of mother Mother high/medium level Mother low level (reference group) 3.7 (1.9 - 7.1)* 1 Student’s religion Other Catholicism (reference group) .6 (.4 - .9)* 1 The gender and age of the siblings (at least one sister aged between 10 - 16 years) Yes No (reference group) 1.6 (1.4 - 1.9)* 1 The propensity to vaccinations in general Yes No (reference group) 13.1 (9.7 - 17.8)* 1 Knows that HPV vaccine is aimed at preventing cervical cancer Yes No (reference group) 3.2 (2.6 - 4.1)* 1 Thinks that HPV might concern you? Gender Female Yes No (reference group) Male Yes No (reference group) 3.8 (1.6 - 3.9)* 1 4.0 (2.6 - 4.2)* 1 Note: *p < .05; CI, Confidence Interval; OR = Odds Ratio. 1ORs from multivariate logistic regression models, adjusted for gender and religion of the student, education of the parents and presence, age and gender of their brothers and/or sisters. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1145  L. ELISA ET AL. they were in a relationship (41.4% of females vs. 18.5% of males). 31.0% of the individuals interviewed (95% CI 25.9% - 36.7%) stated that they have had sex (males 73.3% vs. females 26.7%: p < .05), therefore they have been classified as sexually active. Among the students classified as sexually active (93.3%), the presence of a higher level of information on the HPV virus was found compared with students that are not sexually active (84.0%); (p < .01). Knowledge of infection from HPV is much higher in women (80.8%) compared with men (19.2%); (p < .01). Among the sexually active students, 39.0% (95% CI; 29.0% - 49.0%) see themselves as an individual at risk; while, out of the non sexually active students, only 9.0% (95% CI, 5.0%, - 12.0%) believe that they risk contracting infection from HPV. The average age of a first sexual experience has been Regis- tered at around 14.9 ± 1.02 years with statistically significant differences in terms of gender (males 14.6 ± 1.02 years vs. females 15.1 ± 1.03 years; p < .05). Among the students that declared that they are sexually ac- tive, 67.9% stated that they had had just one partner (67.9%, CI 56.8% -77.6%); 16.7% declared that they have had two and 9.5% stated that they have had more than three partners. The males stated that they have had more than three partners (83.3%); however, women stated that they have had just one (43.8%). This leads us to confirm a statistically significant dif- ference between men and women (p < .05). 66.7% (95% CI, 57.7% - 75.9%), declare that they use con- traceptives. The most common form of contraception used is a condom (97.5%, 95% CI, 93.4% - 99.5%). The girls that stated that they rarely or never use condoms would like to be subjected to the vaccination against HPV. Paradoxically, it seems that the girls that have shown the great- est inclination to the HPV vaccination may benefit less from the vaccination. In reality, in light of the proof available on the HPV vaccination, these girls may already be infected by HPV due to their high risk sexual behaviour (Piana, Sotgiu, Castiglia et al., 2011; Pieralli, Fallani, Lozza et al., 2011; Vaccarella, 2010). 67.9% (95% CI, 62.5% - 73.0%) claim that they have spoken about their own sexuality with friends while half of the sample has not discussed this subject with its parents, unless the topic was introduced by the parents themselves (36.5%); (95% CI; 30.8% - 42.5%) or in the case of specific problems (14.2%); (95% CI; 10.3% - 18.9%). The girls that declared that they have had more than 3 part- ners (9.8%, OR = 2.4, CI 95% 1.1 - 4.9, p < .05) were more willing to have the HPV vaccination while the ones that stated that they do not use a condom (36.9%, OR = .5; 95% CI .3 - .6, p < .05) appeared to be less inclined to refuse the HPV vaccine- tion (Table 4). The main factors associated with the inclination of the stu- dents to accept the HPV vaccination were: the presence of at least one sister in the family; being favourable to vaccinations in general; knowing that the objective of the vaccination was to prevent CCU. As highlighted in other studies (Do & Wong, 2012; Bar- tolozzi, Bona, & Ciofi, 2007) there is a positive association between the perception of risk of infection from HPV and the inclination of male and female students to be subjected to the vaccination. Table 4. Association between sexual behaviours and attitudes of students (fe- male) to being vaccinated against HPV1. Independent variables OR (95% CI) Has a boyfriend/girlfriend? Yes No (reference group) .3 (.1 - .6)* 1 Has had sexual inter course? Yes No (reference group) .7 (.4 - .9)* 1 How many persons have you had se x ual intercourse with? 1 partner (reference group) 2 partner ≥3 partner 1 1.7 (.7 - 3.8)* 2.4 (1.1 - 4.9)* Do you use condom? Yes No (reference group) .5 (.3 - .6)* 1 Note: *p < .05; CI, Confidence Interval; OR = Odds Ratio. 1ORs from multivariate logistic regression models, adjusted for gender, mean age of the first sexual inter- course, to have two o more partners, using condoms. This data strengthens the idea that the starting point for the success of the HPV vaccination campaign should be to increase the level of awareness of adolescents on this subject, highlight- ing in particular the aspects related to the frequency of infection from HPV. However, factors such as having a boyfriend or already hav- ing had sex are factors associated with a reduced inclination to vaccination among female students, perhaps because a high percentage of them are aware of the fact that they should have received the vaccination before starting sexual activities (Mas- sini, Marona, Di Pinto et al., 2010). All of this highlights the need for a training programme fo- cused on epidemiology related to infection from HPV in con- nection with different age groups and the associated risk factors so as the prove that the vaccination is useful, even after the start of sexual activities, as long as the individual has not yet been infected (Caskey, 2009). From a general analysis of data, the efficiency of the inter- vention has emerged: the experimental group (and only this one) has changed the perception of casualness in terms of health. At the end of the intervention more than before, health protection has been strictly correlated with behaviour, life styles and per- sonal choices. This finding has been correlated with specific objectives of the intervention; furthermore, peer education has been assessed and compared with the changes expected after the intervention, after four months and after one year, to check if and how much the knowledge, but most importantly, the behaviour had really changed and been maintained in time. Our figures have shown that greater understanding with re- gards to infection from HPV and the possibility of preventing CCU thanks to the vaccination may increase the inclination of youngsters to having the vaccination. Furthermore, information related to the HPV test and information related to the vaccina- tion require the use of efficient communication and constant monitoring activities. This should involve, most of all, women identified as the ones that need information the most and are included in the age group at risk, in which the diffusion of information is vital to Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1146  L. ELISA ET AL. favour aware choices (Baseman & Koutsky, 2005). Our research confirms how friends, in the age group of ado- lescents, have a positive effect on the adoption of lifestyles of friends of their own age. The meetings were very useful to stimulate youngsters to- wards communication among equals with regards to HPV to teach them not to delegate their own health and to create the competence (life skills) that allow them to be directly responsi- ble for their own health, not only the beneficiaries but also the protagonists of the intervention (Marmocchi, Dall’Aglio, & Zannini, 2004; Bertini, Braibanti, & Gagliardi, 2006). Throughout the entire course, the participants showed the ability to work in a group and to be an important part of it, il- lustrating their willingness and enthusiasm, desire to under- stand and learn, desire to collaborate and a sense of responsibi- lity. Situations in order to overcome the generational commu- nication barriers necessary to implement truly efficient preven- tive intervention (De Santi, Ranieri Guerra, Morosini et al., 2008). The style of participation of the meetings also allowed stu- dents to face topics related to adolescent life and relationships with people of the same age and with adults. Group discussions favoured observations on risky behaviour and the underlying reasons, as well as a comparison of prejudices, shared mentali- ties and the social prototypes of the world of youngsters con- nected with this infection, in order to understand how these elements affect the choice of behaviour. On the basis of these considerations and observations illustrated by students and teachers, we can deduce that participation in this experience has strengthened the sense of empowerment in the participants as well as self-trust and the pleasure of being useful to people of their own age and having given them a chance to exchange comments on the topic of HPV (Pellai, Rinaldin, & Tamborini, 2002; De Santi, Ranieri Guerra, Morosini et al., 2008). The limits of this investigation are the ones that can be cross- checked in a randomised and controlled study and they can be compared with representativeness of the sample in terms of the external validity of the study. In reality the controlled random- ised study may result in distorted results if the methodological rigour is missing (Kenneth, Schulz, Altman et al., 2010). Recruitment was limited to one single province and the sam- ple of schools essentially represents the medium-high class of the population. Even though the proportion of individuals interviewed was high and despite the fact that those schools participated, whose headmasters were mainly interested in infection from HPV and the promotion of health, the presence of a bias selection cannot be excluded, due to the different social-demographic character- istics of the schools that participated, compared with the ones that did not take part in the project. Moreover, one can not non consider of the various ages must be made among the individuals aged between 15 and 18 with the other variables such as the cultural models or experience, resulting in the layout of a composite or differential variable research, so much so that the results of the analyses should be interpreted in descriptive terms but with the technique still re- maining the same. Furthermore, if on the one hand the fol- low-up time of one year can wait for the effective permanence of information and the variation in changes, on the other hand it is inclined to being deeply affected by other events or other information channels that, during that specific period of time, could have intervened for/against the knowledge and the global attitudes expressed by the individuals (Kenneth, Schulz, Alt- man et al., 2010). However, the results achieved are coherent with the initial hypothesis of research. Our results highlight that the approach to peer education has been warmly welcomed by students; this can facilitate the fu- ture adoption of similar projects. The results discussed in this study is on the positive evalua- tion of short-term and one year denotes that the positive results persist and even increase in the time. In reality, the long term persistence of the effects produced is a vital aspect. Therefore, another assessment on how this programmes can be carried out using, for example, recall sessions, will be necessary. On the contrary, the greatest strong points of this study are the large dimensions, the availability of information received from students and inclusion in the sample of male and female individuals, but also the assessment of efficiency one year after the intervention. Conclusion It is difficult to come into contact with adolescents especially if discussions refer to the same ones discussed in this document and with regards to which girls/boys do not understand the real risk, as they are too far away; in fact the consequences deriving from the adoption of behaviour considered to be risky can only be seen on the long term (Croce & Gemmi, 2003). For several years the various studies carried out on peer education have come up with substantial changes in knowledge and in the atti- tude between peer educators and those reached by the interven- tion (Massini, Marona, Di Pinto et al., 2010). The representa- tives of youngsters are the youngsters themselves and peer education may be much more efficient in health promotion compared with traditional educational techniques (Pellai & Boncinelli, 2003; Landi, 2004). The first important thing is what one wants to say but the second important thing is how one says it! The means is the message! (Nizzoli & Colli, 2004; Pellai & Boncinelli, 2003). Youngsters listen and believe in youngsters but adults and institutions are the ones that possess the knowl- edge: working together in a combined manner is the best way of helping youngsters to preserve their health. Another important aspect that it is important to remember here refers to the need to carry out an efficiency assessment on long term intervention. The follow-ups, the first one four months and the second one year after the end of the educational intervention illustrate the efficiency of the training intervention through the use of peer education (Barreto, 2005; Derzon, Sale, & Springer, 2005). The study carried out highlights important differences between the experimental group (subject to the intervention) and the control group (not subject to the interven- tion) in terms of knowledge but, most importantly, in behaviour and it proves how the application of new educational methods based on the involvement of youngsters right from the initial stages of the project can help them to change their behaviour and maintain it in time. Finally, by working in this direction it is possible to create social campaigns using languages, methods and images taken from the world of youngsters, with greater probability of achieving this target with greater effectiveness (Pellai, Rinaldin, & Tamborini, 2002). Our research confirms how friends, in the adolescent age group, have a positive influence on the adoption of lifestyles of Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1147  L. ELISA ET AL. their peers. Adolescents live in a transition period, searching for support in their peer group in order to complete their growth stages, as confirmed by our quality figures. The intervention in question therefore appears to have produced positive results: the majority of students would like to have further meetings with their peers (De Santi, Ranieri Guerra, Morosini et al., 2008). Strengthening the resources in each youngster means helping them to make a small step forward towards their future: training through information allows them to acquire a fair overview of the chances available to grow in a healthy and free manner (Goodstadt et al., 2001). In general terms, after a careful examination of the results, we can state that with regards to the topic involved in our re- search, the two samples have come up with significantly dif- ferent averages: the individuals from the experimental group have generally had better levels of performance compared with those from the control group (Barreto, 2005; Derzon, Sale, & Springer, 2005). In the two follow-ups, with regards to correct answers, the youngsters belonging to the experimental group have proved to have greater familiarity of information related to the HPV virus and vaccination and a consolidation of changes in their behaviour. Acknowledgements We are grateful to the peer educa-tors and the schools par- ticipants for their cooperation and assistance. Ethical Approval All procedures were approved by the appropriate academic committees. Conflict of Interest The authors declared that they have no conflict of interests. REFERENCES Adamchak, S. E. (2006). Youth peer education in reproductive health and HIV/AIDS: Progress, process, and programming for the future. URL (last checked 12 August 2012). http://archive.k4health.org/system/files/Peer%20Education%20Over view.pdf Agreement between the Government, the Regions and the Independent Provinces of Trento and Bolzano Concerning (2007). Strategies for active offer of the vaccination against infection from HPV in Italy. URL (last control 12 August 2012). www.statoregioni.it/Documenti/DOC_016696_264%20csr.pdf Barreto, M. L., (2005) Efficacy, effectiveness and evaluation of public health interventions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59, 345-346. doi:10.1136/jech.2004.020784 Bartolozzi, G., Bona, G., Ciofi, M., De Martino, M., Di Pietro, P., Duse, M. et al. (2007). Human papillomavirus vaccination. Consensus Conference in pediatric age. Minerva Pediatrica, 59, 165-182. Baseman, J. G., & Koutsky L. A. (2005). The epidemiology of human papillomavirus infections. Journal of Clinical Virology, 32, S16-S24. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2004.12.008 Bertini, M., Braibanti, P., & Gagliardi, M. P. (2006) Skills for life. Milano: Franco Angeli. Boda, G. (2001). Life Skill e peer education: Strategy for personal and collective efficacy. Milano: R.C.S. Libri SpA. Chan, S. S. C., Yan Ng, B. H., Lo, W. K., Cheung, T. H., & Hung Chung, T. K. (2009) Adolescent girls’ attitudes on human papillo- mavirus vaccination. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 22, 85-90. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2007.12.007 Croce, M., & Gemmi, A. (2003). Peer education: Adolescents as pre- vention actors. Milano: Franco Angeli. De Santi, A., Guerra, R., Morosini, P. et al. (2008). Health promotion at school: Educational objectives and shared skills. Rapporti ISTISAN, 1, 1- 174. Derzon, J. H., Sale, E., Springer, J. F., & Brounstein, P. (2005) Estimating intervention effectiveness: Synthetic projection of field evaluation results. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 26, 321-343. doi:10.1007/s10935-005-5391-5 Di Giuseppe, G., Abbate, R., Liguori, G., Albano, L., & Angelillo, I. F. (2008). Human papillomavirus and vaccination: Knowledge, atti- tudes, and behavioural intention in adolescents and behavioural in- tention in adolescents and young women in Italy. British Journal of Cancer, 99, 225-229. Do, Y. K., & Wong, K. I. (2012). Awareness and acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccine: An application of the instrumental variables bivariate probit model. BMC Public Health, 12, 31. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-31 Ferrara, M., De Vito, E., Langiano, E., Gentile, A., & Ricciardi, G. (2006). By Eros to Thanatos, AIDS and sexually transmitted diseases. Rapporti ISTISAN, 20, 125-129. Ferrara, M., Gentile, A., Merzagora, L., Tucci S., De Vito, E., Langiano, E., & Ricciardi G. (2004). The prevention of synthetic drugs: Survey on knowledge of synthetic drugs in a sample of students from the Secondary School specialising in Scientific Studies, of Cassino. Edu- cazione Sanitaria e Promozione della Salute, 27, 108-117. Ferrara, M., Langiano, E., & De Vito, E. (2012). A school based com- munity randomized trial of the effect of peer health education on primary prevention knowledge, attitude and behaviours towards HPV among adolescents. Italian Journal of Public Health, 9, 20-32. Ferrara, M., Langiano, E., Di Thiene, D., & De Vito, E. (2010). The project “D.E.A.Th. by Eros to Thanatos AIDS and sexually trans- mitted diseases”. A multimedia exhibitions a means of prevention of sexually transmitted infections. Italian Journal of Public Health, 7, 268-276. Franco, E. L., & Harper, D. M. (2005). Vaccination against human papillomavirus infection: A new paradigm in cervical cancer control. Vaccine, 23, 2388-2394. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.01.016 Friedman, L. S., Kahn, J., Middleman, A. B., Rosenthal, S. L., & Zimet G. D. (2006). Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: A position statement of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. Journal of Ado- lescent Health, 39, 620. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.07.013 Giambi, C. (2011). Coverage rates of HPV vaccination in Italy. Italian Journal of Public Health, 8, S23-S27. Goodstadt, M. S. et al. (2001) Evaluation in health promotion: Synthe- sis and recommendations. WHO Regional Publications, European Series, 92, 517-533. Hoffman, B. R., Sussman, S., Unger, J. B., & Valente W. T. (2006). Peer influences on adolescent cigarette smoking: A theoretical review of the literature. Substance Use & Misuse, 41, 103-155. doi:10.1080/10826080500368892 IARC (2007). IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Volume 90: Human papilloma viruses. Lyon: Inter- national Agency for Research on Cancer. Kenneth, F., Schulz, K., F., Altman, D. G., Moher, D., & CONSORT Group (2010). CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Italian Journal of Public Health, 7, 327-332. La Torre, G., De Vito, E., Martellucci, L., Langiano, E., & Ricciardi, G. (2002). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding sexually trans- mitted diseases among students in three high schools in Cassino. Annali di Igiene, 14, 233-242. La Torre, G., De Vito, E., Capelli, G., Langiano, E., Ferrara, M., & Ricciardi, G. (2003). Knowledge and attitudes of principals and school teachers in the province of Frosinone in the health education. Educazione Sanitaria e Promozione della Salute, 26, 290-297. Landi, M. (2004) Peer education. In: E. Dalle Carbonare, E. Ghiottoni, & S. Rosson, Peer educator: Instructions for use. Milano: Franco Angeli. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1148  L. ELISA ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1149 Louvanto, K., Rintala, M. A., Syrjänen, K. J., Grénman, S. E., & Syrjänen, S. M. (2011). Incident cervical infections with high- and low-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infections among mothers in the pro- spective Finnish Family HPV Study. BMC Infectious Diseases, 11, 179. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-11-179 Marmocchi, P., Dall’aglio, C., & Zannini, M. (2004). To educate to the life skills. Trento: Erickson. Massini, S., Marona, R., Di Pinto, G. H., & Saulle, R. (2010) “Facoltà d’Amarsi”: When young people try to change the situation. Youth project as a tool for health communication and STD prevention. Italian Journal of Public Health, 7, 277-291. Nizzoli, U., & Colli, G. (2004) Young people who risk their lives. Understand and treat high-risk behavior in adolescents. New York: McGraw-Hill. Pellai, A., & Boncinelli, S. (2003) Just do it! Risk behaviors in adole- scence. Prevention manual for school and family. Milano: Franco Angeli. Pellai, A., Rinaldin, V., & Tamborini, B. (2002) Peer education. The- oretical and practical manual of Empowerment peer education. Trento: Erickson. Piana, A., Sotgiu, G., Castiglia, P., Pischedda, S., Cocuzza, C., Capo- bianco, G. et al. (2011). Prevalence and type distribution of human papillomavirus infection in women from North Sardinia, Italy. BMC Public Health, 11, 785. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-785 Pieralli, A., Fallani, M. G., Lozza, V., Corioni, S., Longinotti, M., Fambrini, M., & Penna, C. (2011). Age-specific distribution of Hu- man Papilloma Virus (HPV) mucosal infection among young fe- males. Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 1, 104-108. doi:10.4236/ojog.2011.13018 Roden, R. B. S., Morris Ling, B. S., & Wu, T. C. (2004). Vaccination to prevent and treat cervical cancer. Human Pathology, 35, 971-982. Schiffman, M., Castle, P. E., Jeronimo, J., Rodriguez, A. C., & Wa- cholder, S. (2007). Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. The Lancet, 370, 890-907. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61416-0 Sopracordevole, F., Cigolot, F., Lucia, E., & Marchesoni, D. (2009) Knowledge on human papilloma virus (HPV) related genital lesions and vaccination against HPV in a sample of women of north-east Italy. Minerva Ginecologica, 61, 81-87. Spizzichino, L. et al. (2005). Adolescenti e HIV. Adolescents and HIV. Information campaigns by adolescents and for adolescents. Annali Istituto Superiore di Sanità, 41, 113-118. Supporting Community Action on AIDS in Developing Countries (2006). Peer education: Outreach, communication & negotiation. Training Module. URL (last check 12 August 2012). http://www.aidsallianceindia.net/Material_Upload/document/Peer_ed ucation_manual.pdf Syrjänen, S. (2005). Human papillomavirus (HPV) in head and neck cancer. Journal of Clinical Virology, 32, 59-66. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2004.11.017 United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and Family Health Interna- tional (FHI) (2005). Training of trainers manual. Youth peer educa- tion toolkit. New York and Arlington, VA: UNFPA and FHI. URL (last checked 12 August 2012). http://38.121.140.176/c/document_library/get_file?p_l_id=33873&fo lderId=36046&name=DLFE-406.pdf Vaccarella, S. (2010). Epidemiology of HPV infection and cervical cancer. In C. Giorgi (Ed.), HPV infection: From early diagnosis to primary prevention. Rome: Istituto Superiore di Sanità. World Health Organization (2007). Global strategy for the prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections: 2006-2015: Breaking the chain of transmission. URL (last checked 12 August 2012). http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241563475_eng.pdf World Health Organization (2006). Preparing for the introduction of HPV vaccines: Policy and programme guidance for countries. URL (last checked 12 August 2012). http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2006/WHO_RHR_06.11_eng.pdf young

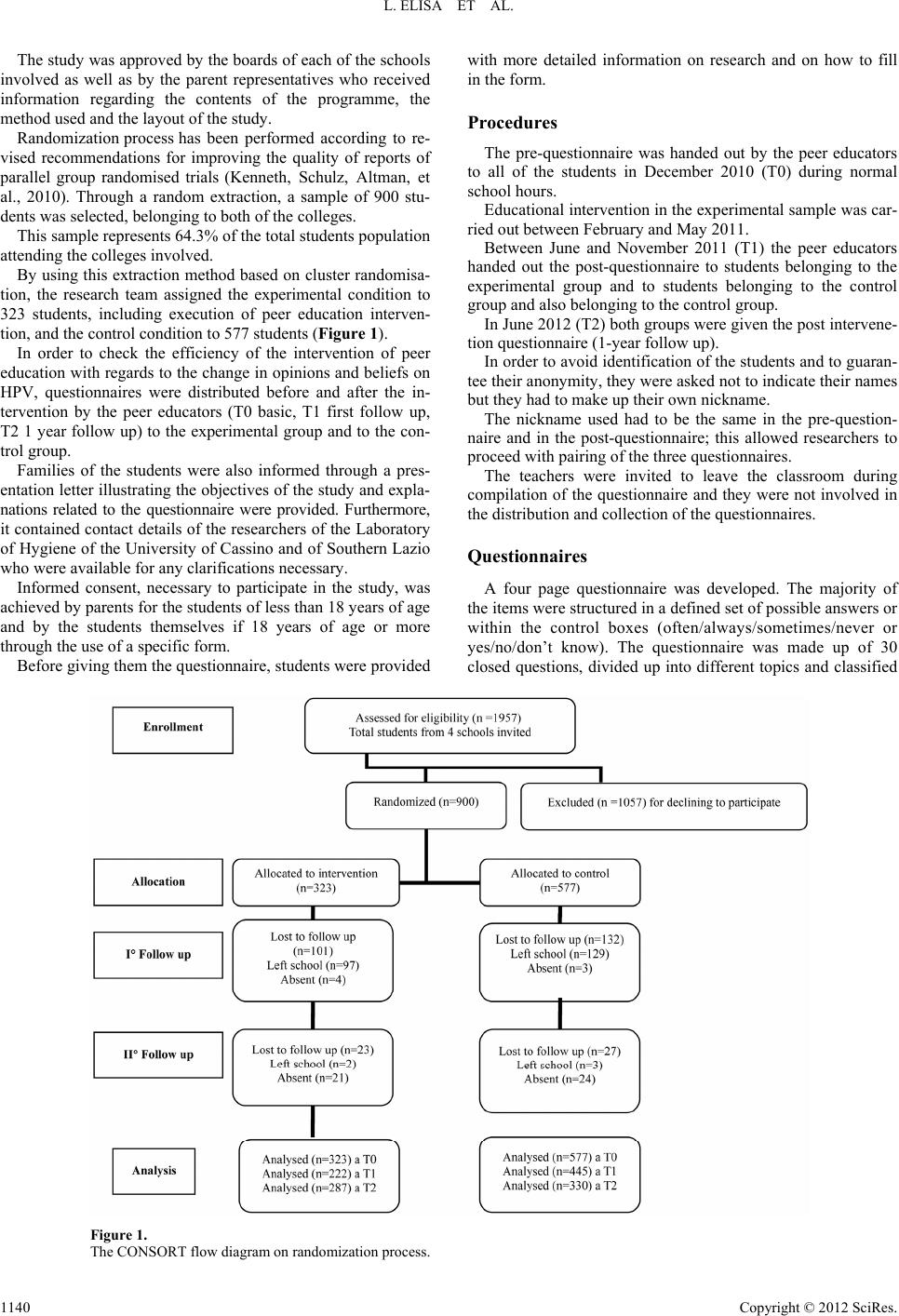

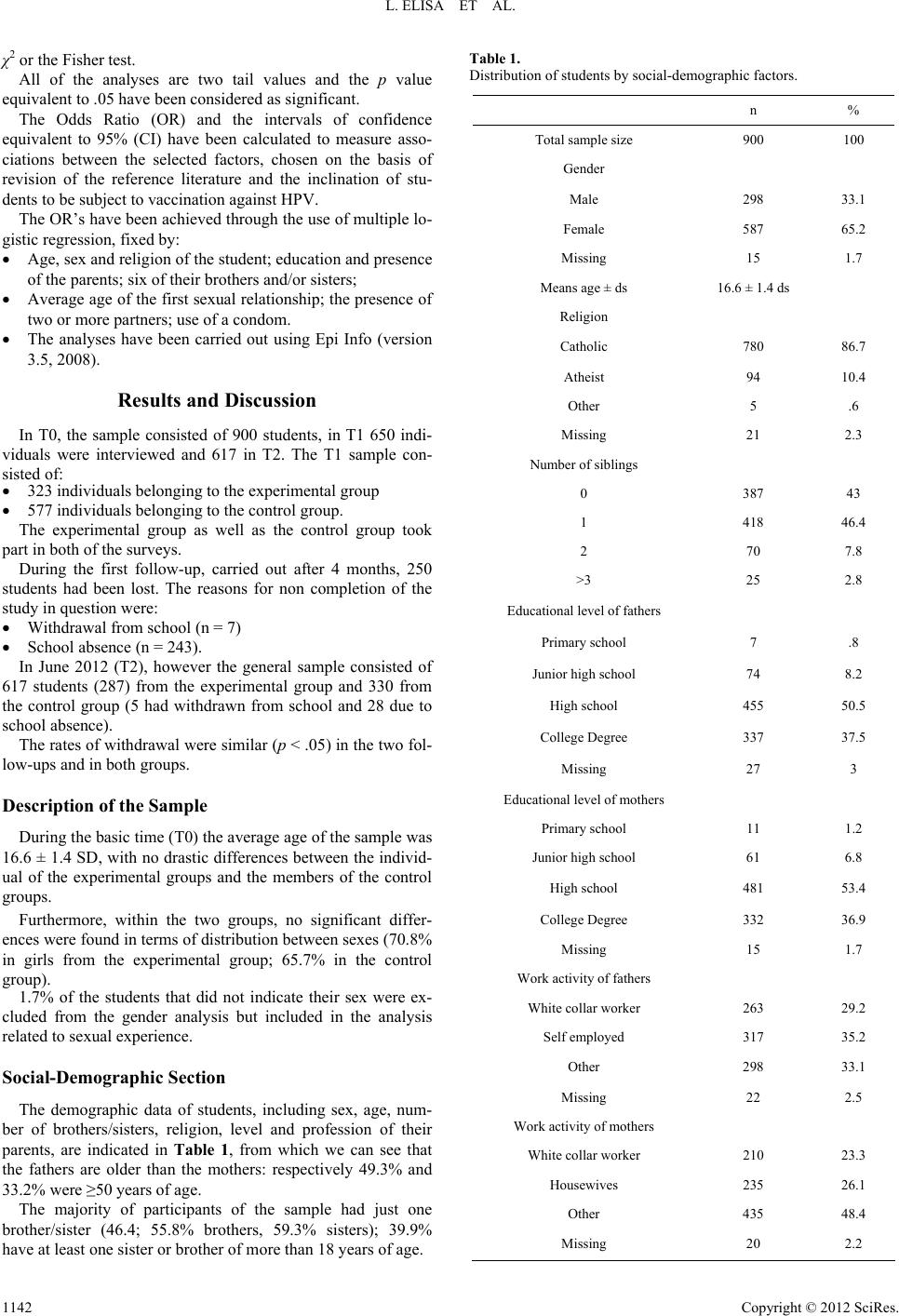

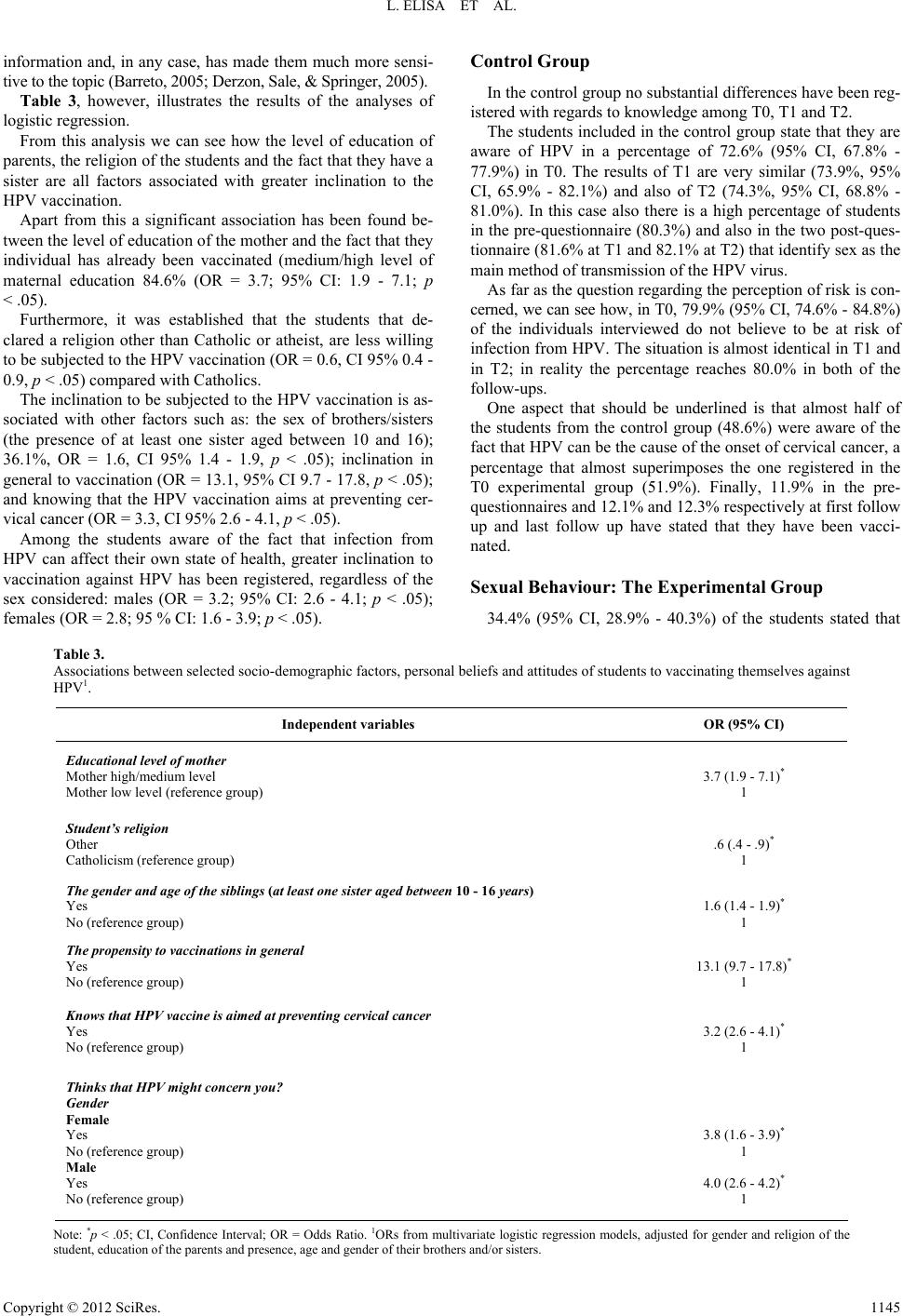

|