Creative Education 2012. Vol.3, Special Issue, 996-1005 Published Online October 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.326151 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 996 East Jerusalem Students’ Attitudes towards the Acquisition of Hebrew as a Second or Foreign Language in the Arab Educational System of East Jerusalem and Society’s Support Salman Ilaiyan Academic Arab College for Education in Israel, Haifa, Israel Email: salman@macam.ac.il Received August 14th, 2012; revised September 12th, 2012; accepted September 27th, 2012 This is a pioneering study examining the eighth grade students’ attitudes in the Arab Education System in East Jerusalem towards learning Hebrew as a foreign/second language: their readiness to communicate in it, and the extent of the community support to learning it. The study is based on Schuman’s (1978) social theories regarding acquiring foreign/second language. The extent of the learner’s social integration in the community of the foreign/second language determines the extent of his success in acquiring the language. The study sample included 643 eighth grade students from East Jerusalem schools who are learning He- brew as an elective subject. The study questionnaire included three parts: 1) Attitudes towards learning a foreign/second language; 2) Readiness to communicate in a foreign/second language; 3) The social sup- port. The study findings indicate statistically significant positive correlation between all the measures of the following variables: 1) Attitudes towards a foreign/second language and readiness to communicate in it; 2) Attitudes towards Hebrew as a school subject got a higher positive score than attitudes towards the speakers of the language; 3) Family support (father/mother) got a higher positive score than the friends’ support, and this is following the instrumental issue. The main conclusion of the study is that there is a need to formulate a systemic and unique work plan accompanied with an addition of suitable position and budget to handle the problem of teaching Hebrew as a foreign/second language. Keywords: Social Support; Language Acquisition; Foreign Language; Motivation; Family Support; Social Support; Readiness to Communicate; Integration; Social Factors; Gender East Jerusalem and the Status of Teaching Hebrew East Jerusalem has a population of about 863,900 inhabitants. About 265,600 Palestinian Arabs with permanent residency status comprising 1/3 of the city residents. This population is characterized by life below the poverty line (over 50% of the families), high unemployment rate, a high birthrate (4.5 chil- dren in the family), a high divorce rate reaching 30% in some neighborhoods, a high rate of illiteracy among parents, and more (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2008). The Arab population in the Palestinian East Jerusalem has a unique legal status because, until 1967 they lived under the Jordanian legal system. After the Six Day War, a change took place: the civil society of the city was ruled by the Military Directorate of the West Bank. Later, it was annexed and placed under the municipal jurisdiction of the Jerusalem municipality. Residents of East Jerusalem were awarded permanent residency status and the Israeli law1 was applied on them (Vergen, 2006). This situation affects the population in most aspects of life and whenever a particular aspect was examined in the context of the East Jerusalem Arab population, it demanded attention to two areas: 1) The city’s position politically. 2) The status of the residents and how they see themselves. The city of Jerusalem and the residency status of its popula- tion was the focus of several studies. The city attracted so many descriptions by the people who visited the Holy Land, the cen- ter of attraction of the three religions. Many writers of travel literature devoted to the Holy Land a considerable part of their writing to describe the city and its population. Also spoken Arabic in Jerusalem has been addressed and the Jerusalem dia- lect of Arabic was covered in several studies2. In addition, in Jerusalem Jews and Arabs lived for centuries, and it is natural that the daily speech of the inhabitants was mutually influenced by Arabic and Hebrew. East Jerusalem education system includes about 100 schools, half of which belong to the State Education System and the rest are private schools. A small number of schools belong to the Palestinian Authority (Eir Amim Association, 2005). The dropout phenomenon is alarming and has reached 45%; the percentage of eligible high school graduates for the Towjihi (equivalent to the Bagrouth certificate in Israel) reaches only 20%. Construction of the separation wall in Jerusalem and around it poses additional obstacles to access to education of Palestinian children in Jerusalem (Eir Amim and the Associa- tion for Civil Rights, 2010). As a result of the Oslo agreements, the Jordanian law was 1The application of Israeli law on Jerusalem see Knesset Statements, 2006; “B’Tselem”—The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories (Statistical Abstracts, 2003). 2The Spoken Arabic dialect of the city of Jerusalem was the focus of research; see Levine, A. (1995). Grammar of Arab dialect of Jerusalem and bibliography presented there, Jerusalem.  S. ILAIYAN canceled, and Arab students in East Jerusalem adopted the Pal- estinian plan (Vergen, Research and Information Center Report, 2006). This took place despite the enactment of a special law in 1969, which made these institutions subject to the Israeli super- vision (Hassona, 1998). Out of respect and understanding of the residents’ desire (and perhaps the reality dictated this), the Israeli authorities and the public schools of East Jerusalem from the Jordanian period agreed to implement a learning method that would meet the requirements of both parties—that is, government schools were given the opportunity to continue to teach according to the Jor- danian plan, and the students were allowed to take their exams in it, but two subjects were added to the program without the requirement of external examination: Hebrew Language and Civics (Ilaiyan & Arayeda, 2008). Following conversations with Soheila Abu Ghosh, Deputy Director of the Arab sector and Municipal Commissioner of Education in the education directorate of Jerusalem, we learned that learning Hebrew in urban schools in the public school sys- tem in East Jerusalem takes place from the third through the eighth grades, but teaching Hebrew is negligible and is not “equivalent in value and status” to the English language, and therefore, Hebrew was not included in the Towjihi (Bagrouth) examinations. Soheila noted that Hebrew is the second foreign language, while English is the first. Another aspect of reference that points out the not in-depth treatment of Hebrew is that the subject teachers in the State schools in East Jerusalem are mainly students lacking training in teaching Hebrew. Most of them are graduates of different subjects or students in higher education institutions in Jerusa- lem. Most of these individuals come from the Arab sector in Israel. It is important to point out that Hebrew is an elective subject in most public schools of East Jerusalem and the student is not obligated to be tested in it. Private schools, which constitute approximately 70% of all schools, hardly teach Hebrew (Has- sona, 1998). In these schools, few students learn Hebrew. The question is: Can we say that Hebrew is a foreign language for the population of students? The answer is that due to the expo- sure of the population and students to Hebrew in their daily life (market, banks, post offices, municipality, and other official institutions), Hebrew becomes the first foreign language for them. East Jerusalem Arab population speaks Arabic with the Je- rusalem dialect and is exposed to Hebrew intensively in every- day life due to the topographical situation of the city. Much of the Hebrew language learning is done by daily contact and involvement with the Jewish population. Therefore, Hebrew has an instrumental role in the life of the Jerusalem population: primarily because it is the language of the establishment, academy, business and administrative life in the city. Theoretical Background In the socio-linguistic literature, a distinction is made be- tween foreign language acquisition and second language acqui- sition. According to Brosh (1988), a second language is taught and used by the individual in its immediate vicinity, while a foreign language is taught as a language that is used across the national territorial borders. In other words, a second language is used in the environment surrounding the individual, while in a foreign language is not. A second language is different from a foreign language be- cause it is used intensively in the daily life; and the speaker is exposed to it actively in terms of use. A foreign language, however, is generally used on special occasions or at meetings with its native speakers. A foreign language has great weight in the issue of speech, while a second language is important in both speech and writing. Teachers and educators emphasize the significance of speech and hearing of a foreign language. Ader (1965) emphasizes the point that when teaching another language to children, there is special significance to a number of factors such as: the age of the child, his level of cognitive and emotional development, his attitudes towards language that prevails in his immediate vicinity, the degree of control over the first language and the nature of communication with him in the target language. There is another language that is predomi- nant in the learner's environment, to which he is also exposed all the time, mostly in informal learning environment. This is similar to the situation of learning Hebrew by the immigrants living in Israel. A foreign language is taught in a formal setting and, unlike a second language, it has no support for contextual learner’s environment (Nevo, 2005). According to Olstein (1997), the process of acquiring a sec- ond language takes place from the place of the child in his na- tive language. The child is aware that language has structures which meet certain laws, and he is able to apply schemes from his first language to the one being taught (even if the result is sometimes incorrect). He does not need to find out what the language is, but the essence of the new language (Olstein, 1998). One of the important goals of learning a second or a foreign language is to allow better communication, dialogue and under- standing among people who come from differing cultural back- grounds and speak different languages (Yashima, Zenuk-Ni- shide, & Shimize, 2004). It should be noted that bilingual education can be a tool to empower minority’s language, creating equality between ma- jorities and minorities, collaboration, contact and interaction, and thus can help to resolve conflicts between groups and en- courage a change of negative attitudes within the group (Beker- man & Horenczyk, 2004). Over the years, changes in curricula have taken place and were adapted, in part, to the Arab learner’s needs. However, there is no reference in these plans, as well as textbooks, to the treatment of interruptions caused by interference of the mother tongue, or with respect to increasing motivation for learning Hebrew among Arab students. Social Factors and Second Language Acquisition Different variables affect the acquisition of a foreign/second language such as social variables, due to their great importance and influence on attitudes and motivation (Bassal, 2007). Schumann (1978) argues that the degree of social and psycho- logical integration of the learner in community of the foreign/ second language determines the degree of success in acquiring the language. According to this argument, social variables may affect learning in several ways: they can help or hinder the creation of information between the two linguistic groups; they affect the extent to which the learner is ready to integrate into the target language, and willingness to integrate into society; and they affect the language skills that the learner is capable of reaching. Spolsky (1989) maintains a similar argument by stat- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 997  S. ILAIYAN ing that the social context dictates the quality of the conduct of the learning process. The gap between the target language population and the mi- nority group (“social gap”) is particularly significant, because the larger the social distance between two groups is, the lower the degree of success in acquiring the target language is. Not only the real social distance between the two groups affects the study of language, but also the social distance as perceived by the learner based on social, cultural and political experience (Bechor, 1992; Schumann, 1978). Moreover, language acquisi- tion is related to the existing relationship between the learner’s social group and the social group of the target language. These relationships may vary in different environments from political and other viewpoints; and so is the preparedness for language acquisition (Zeevi, 1995; Ellis, 1994; Giles & Byrne, 1982). The findings of a study by Tahar (2005) reflect the impor- tance of the impact of the living environment and society on the social attitudes and willingness to communicate in a foreign/ second language, especially the friends’ support, which was found to affect these variables more than the parents’ support. Note that the group of friends in adolescence affects the ado- lescent’s behavior more than the parents. The adolescent tries to dissociate himself from his parents’ positions in order to em- phasize his independence, and this is reflected in part in ado- lescent attitudes toward foreign/second language. Attitudes and Additional Language Acquisition Attitudes, whether positive or negative, are emotions directed towards the other and to various social situations: If the emo- tion is positive, it will affect positively the learning situation, and vice versa (Abu-Rabia, 1999). According to Gardner (1980), the learner’s attitudes towards the language are acquired as a result of experience in a socio-cultural environment, from family and community atti- tudes that are acceptable in the learners’ surrounding, which form the interest in acquiring the target language. Studies that examined the association between attitudes to- wards a language and the willingness to communicate in it found that a positive correlation between these variables and positive attitudes towards the language and its native speakers leads to communicative behavior in such foreign language (Yashima et al., 2004). Motivation for learning the language constitutes significant factor in learning a foreign language; and it has a more signifi- cant role in this context than the relationship of native language acquisition (Clement, Dornyei, & Noels, 1994; McIntyre, Baker, Clement, & Donovan, 2003). High motivation to learn a foreign/second language and posi- tive attitudes towards the language and its speakers are vari- ables that affect the willingness to communicate in the language. In studies conducted in different ethno-linguistic situations, the willingness to communicate in a foreign/second language was found to be a predictor of the frequency and amount of com- munication. Motivation for learning a language was found to predict the willingness to communicate and the frequency of communication in such foreign/second language (Dornyei, 2003; McIntyre et al., 2001; Yashima et al., 2004). Findings in the study of Inbar, Donitsa-Schmidt & Shohamy (2001) suggest that learning a foreign/second language in a school context increases the motivation of students towards the language being taught and the culture of the target language. This finding stems from a comparison of two groups who stud- ied Arabic with two groups who did not study Arabic: the best predicting variables of the students’ motivation to learn Arabic in the future were: learning the culture of native speakers, the instrumental trend, environmental stimuli, expectations of par- ents and politics. The findings of Tahar’s study (2005) indicate a positive and significant relationship between attitudes towards the foreign language and the willingness to communicate in this language inside and outside the classroom. Also, significant differences were found between Jewish and Arab students: attitudes of the Arab students were more positive than the Jewish counterparts in all these dimensions. As for willingness to communicate in the foreign language, the Arab students showed greater will- ingness to communicate in Hebrew inside and outside the classroom, compared to Jewish students, who are less willing to communicate in Arabic. Other studies found an association between attitudes and mo- tivation and the process of acquisition of foreign/second lan- guage relevant to the acquisition of the French language by English-speakers in Canada (Gardner & Lambert, 1972; Gard- ner, 1979; Gardner, 1980; Genesse, Rogers, & Holobow, 1983). Similar findings were reached in the acquisition of English by French speakers—a similar situation to that of the Arab resi- dents of East Jerusalem. The main conclusion of the study of Taylor and others (1977) was that the learner’s motivation and attitudes towards the language and its speakers play a signifi- cant role in the acquisition of such foreign/second language. Some researchers consider the attitudes and motivation vari- ables more important than other variables such as intelligence and linguistic ability. They believe that attitudes and motivation direct the orientation of the individual to invest efforts in learn- ing the language in formal or informal contexts, and even affect the degree of utilization of these relationships (Spolsky, 1969; Gardner, 1979; Krashen, 1981). In this context, Oller (1981)) argues that motivation and atti- tudes of the learner to learn the foreign/second language may be affected also by his perception of the attitudes and relation of the language native speakers with him as a member of another community and having a different culture. The study of Genesse et al. (1982) supports this claim. The attitudes of Arab students in Israel towards Hebrew as a second language were the focus of several studies. In Bdair’s study (1990), which was conducted during the first Intifada, he reported a significant association between attitudes towards the language and achievements in learning it. In her study in (1999), Attili found a significant positive correlation between the sub- jects’ general attitudes (Arab students) to the Hebrew language and their achievements in that language. Another finding re- garding the subjects’ attitudes toward the Hebrew language was more positive than that towards the people who speak the lan- guage—the Jews. That is, the learner’s attitudes towards the language have more effect on his achievement than his attitudes towards the speakers of the language being taught. In Ilaiyan (2011), research which dealt with the attitudes of non-Jewish Golan Heights pupils in the subject of acquisition of Hebrew as a second language, findings indicate positive significant corre- lations between the attitude of pupils and their willingness to communicate in the target language. Importantly, in addition to the social environment, there is also an effect of the learning situation. Hebrew status among the Arabs of East Jerusalem is similar to a great extent to the Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 998  S. ILAIYAN status of Arabic in the Jewish sector, who learn Arabic as a foreign language and as an elective. Hebrew has the same status among Arabs in East Jerusalem; it is taught as an elective until the eighth grade without the requirement of taking an exam (Spolsky & Shohamy, 1999). Gender and Second Language Acquisition Influence of gender on language acquisition and attitudes of the two sexes have been tested in several places around the world for decades. First, differences were detected in spoken languages in closed societies, where women’s status differs from that of men; the differences were very pronounced leading to the formation of a “language of women”. Following the es- tablishment of feminist movements in the West, they began to explore these differences in the early seventies, mainly in the United States and Great Britain. The first studies conducted in the English language assumed that also in the West there is discrimination against women and the woman’s social status is inferior to that of man. Because the social differences should be expressed in language too, they hypothesized that there may be language differences between the sexes. The studies of Lakoff (1972, 1975), Spender (1980), Kra- marae, Schulz & O’Barr (1984), concentrated not only on the speakers, but also the languages themselves, feeling that men who created the languages and their grammars, and therefore, they are not suitable for women. The tests revealed a stereo- typical view of gender roles, which is also reflected in the lan- guage. Regarding Arabic and Hebrew, some studies focused on the differences between women and men: Mutchnik (1992) studied the differences in language between men and women in the Hebrew press; Rosenhouse (1998) studied the speech of women and linguistic diversity in the Arabic dialects; Dbiat (2004) tested the use of the masculine rather than feminine by Ara- bic-speaking women in the Galilee and the Triangle. It is not clear whether the differences are physiological fac- tors or socio-cultural reasons or both, but it is likely that the reason for the difference lies in the social dependence. The psycho-social approach that was dominant in the re- search background in this field until the eighties pointed to the prejudices about the power relations between men and women, allegedly causing major linguistic differences. The claims raised by this approach proved not to be always true, and they led to disagreements among researchers. Later, the approach changed, and instead of investigating stereotypes and the feel- ing of discrimination, studies began to concentrate on the fac- tors leading to lack of communication between the sexes (Maltz & Borker, 1982; Tannen, 1990, 1993). This approach is called cultural-anthropological or “the two cultures approach”; it con- centrates on the various differences in the ways of thinking, which are reflected in differences in linguistic behavior. Bilingual studies show differences in the way men and women relate to the language. Tannen (1990) notes that men need to see language as an instrumental need, whereas women see it as a communicative-social need. A major cause of pre- serving the original language better in women is probably the link between the generations; that is educating the younger generation and conserving the links with the older generation. This may also explain why among the second generation immi- grants, women become bilingual, whereas men tend to adopt the new language and to abandon their original language. Coates (1986) indicates that out of many studies, the acquisi- tion of language among girls is better and faster than that among boys. Nevertheless, some studies point out the differ- ences between men and women in the phonological perform- ance of certain sounds. Xin’s (2008) study of learning English as a Foreign Lan- guage in China, she pointed out several factors that affect learners in acquiring the language. Among the factors, she lists the learner’s own personality from which the motivation for language acquisition is derived. She notes that the effect of gender on language acquisition has not attracted the interest of researchers, especially the gender differences. Therefore, it was not possible to understand the differences between men and women in foreign language acquisition. Findings indicated that girls like to learn English as a foreign language more than boys, and they expressed interest in learn- ing it. The girls explained that they learn English as a foreign language as a hobby or just for acquiring knowledge; some of them indicated that they liked the language; others explained that it is an attempt to improve their abilities to communicate with the second language speakers and to improve their social status. In addition, most of the boys expressed their lack of interest in acquiring English as a foreign language and only few of them admitted that English is important for them and that they liked it. The analysis found that girls have higher motivation than boys in acquiring English as a foreign language and they showed interest in learning it. Summary Language acquisition from a socio-political view is a com- plex issue. This study focuses on the question of relationship of the Arab population in East Jerusalem to the Hebrew language. In fact, it attempts to clarify the attitude of the Arab population towards acquisitions of Hebrew as a foreign/second language. On the one hand, Hebrew is seen as the language of the con- queror and the language of confrontation; on the other hand, it is the means through which the population can advance and develop their everyday life. In our opinion, it is important to examine the attitudes of the Arab population in East Jerusalem towards the Hebrew lan- guage acquisition because this issue has various political, social and cultural implications and indications. This study focuses on the student population of eighth graders who start studying Hebrew from third grade to the eighth grade, who constitute an important part of the young Arab population in Jerusalem and they will form the future society. The objective of this study is to examine the attitudes and motivation (integrative and instrumental) of eighth grade Arab students in East Jerusalem towards learning Hebrew as a for- eign/second language, their willingness to communicate in this language and the social support in learning the target language. The study is based on Schumann’s social theories of foreign/ second language acquisition. The significance of this study lies in its being a pioneer study that conducted among the Arab students of East Jerusalem. Research Questions 1) What are the attitudes of the Arab students of East Jerusa- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 999  S. ILAIYAN lem (boys and girls) toward the Hebrew language as a foreign/ second language? 2) What is the relationship between the students’ attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign language, and willingness to com- municate in this language? 3) Does the community support affect the students’ attitudes towards learning Hebrew as a foreign/second language and the willingness to communicate in it? Hypotheses 1) There is a positive correlation between students’ attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign/second language and willingness to communicate in it. 2) There is gender variability between attitudes towards He- brew as a foreign/second language. 3) There is a positive correlation between the community support and the students’ attitudes toward learning Hebrew as a foreign/second language and the willingness to communicate in it. Methodology The Study Population and Sample The study population includes the eighth graders at the State Junior Highs Schools in East Jerusalem. It should be noted that there are seven middle schools and 15 schools in the old format from first to eighth grades (called preparatory schools) and 12 private schools in East Jerusalem, which teach Hebrew as a foreign language to eighth grade. A random sample of 643 eighth grade students was selected from those who came to school during the selection days: 257 boys and 359 girls (27 students did not respond). Students of this age already have attitudes towards the acqui- sition of Hebrew as a foreign\second language, following sev- eral years of experience learning Hebrew. Research Tools The research tool is a questionnaire of attitude and willing- ness to communicate in the foreign/second language, which consists of four parts. The questionnaire was translated into Arabic and has undergone a process of validation by experts; the translation was verified by the Ministry of Education (Tahar, 2005). Part I—Background information about the student, gender, grade and school. Part II—Attitudes Questionnaire: This questionnaire was developed by the researchers inspired by a number of studies that have examined the issues relevant to this study. The ques- tionnaire underwent a process of review and editing by experts (Brosh, 1988; Abu-Rabia, 1999). Attitudes questionnaire includes 23 statements and students were asked to address them and mark their agreement with each statement within 5 degrees of agreement from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree) based on Likert scale. Part III—Social Support Questionnaire: The items were constructed by the researchers inspired by the research of McIntyre et al. (2001). It included three Yes/No questions to examine the student's perception of social support of family and society, and the communication in the foreign/second language. Statements were reviewed by the researchers of foreign/second language and were adapted to the residents of East Jerusalem and checked by experts. Part IV—Willingness and desire to communicate in a for- eign/second language (WTS): Questionnaire items were con- structed by the researchers inspired by previous studies (Tahar, 2005; Yashima et al., 2004; McIntyre et al., 2001), processed with relevance to the Arabs of East Jerusalem and checked by experts. This section included statements that test the degree of will- ingness to communicate in a foreign/second language (Hebrew) orally in and outside the classroom. Statements were rated from 1 (almost always do not want) to 5 (almost always want). The questionnaire addressed two factors to communicate in a foreign/second language (Hebrew): 1) Willingness to communicate in Hebrew in the classroom: during the lesson, with the teacher, requesting an explanation in class, answer a question in class and more. 2) Willingness to communicate in Hebrew outside of class- room: at the market, by phone, with friends after school and others. 3) Attitudes that reflect motivation for learning a language. As stated, the scale of responses ranged from 1 to 5. Vari- ables were constructed by calculating the weighted average of the statements relating to each factor. The higher score suggests that the cause is perceived more positively. Research Procedure Data were collected in late January 2008, after getting a per- mit from the education directorate of the Jerusalem Municipal- ity (JED). Meetings were held between the researchers and the State school administrators of East Jerusalem that teach the Hebrew language to explain the research goals. In a meeting with students in the classroom, the researchers explained the research goals, anonymity of the questionnaire, as well as the lack of effect on grades in the subject. Completing the ques- tionnaire in each class lasts about 45 minutes (duration of les- son). In some cases it took about 10 additional minutes to fill the questionnaire. Findings The First Research Hypothesis In careful examination of Table 1 there is a positive correla- tion between students’ attitudes toward Hebrew as a foreign/ second language and willingness to communicate in it. This hypothesis deals with the attitudes of Arab students in East Jerusalem towards the Hebrew language as a foreign/sec- ond language, its speakers and their culture, and willingness to communicate in it. First, the calculated averages and standard deviations for these variables, and means range from 2.63 to 3.73 on a five-degree scale. To examine the existence of a posi- tive relationship between students’ attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign/second language and willingness to communicate in it, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated and found significant positive correlation (P < 0.01). The more positive students’ attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign language is the higher their willingness to communicate in this language is. Table 2 indicates significant positive correlations between the dimensions of attitudes and dimensions of willingness to communicate in and outside the classroom. We found that as attitudes towards the language as a school subject, attitudes Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1000  S. ILAIYAN Table 1. Means and standard deviations of the study variables. Factor N Mean*S.D. Attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign/second language 637 3.08 .82 Attitudes towards the language as a school subject 637 3.73 .79 Attitudes towards speakers of the language 637 2.63 1.16 Attitudes that reflect motivation for learning the language 637 3.71 .712 General attitudes 637 3.39 .58 Willingness to communicate in class 634 2.78 .85 Willingness to communicate outside of class 634 2.74 .96 General willingness 634 2.76 .81 Note: *Means on 1 - 5 degree scale. Table 2. Pearson correlation: the relationship between attitudes towards Hebrew and willingness to communicate in it (N = 616). Factors Willingness to communicate in class Willingness to communicate outside General willingness Attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign/second language 0.07 −0.10 −0.1 Attitudes towards the language as a school subject 0.45** 0.36** 0.45** Attitudes towards speakers of the language 0.32** 0.53** 0.46** Attitudes that reflect motivation for learning the language 0.44** 0.41** 0.47** General attitudes 0.48** 0.45** 0.51** Note: **P < 0.01. towards its speakers and attitudes that reflect motivation to language are more positive, the willingness of students to communicate in and outside the classroom will be higher. But neither positive nor significant correlations were found between attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign/second language and the willingness to communicate in or outside the classroom. The Second Research Hypothesis There is gender variability between attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign/second language. To examine the difference in the attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign/second language by gender, t test of independent sam- ples was used (Table 3). Table 3 indicates significant differences between boys and girls in the attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign/second lan- guage, attitudes reflecting the language learning motivation, and general attitudes. The girls’ attitudes were more positive than the boys’. Table 3. Results of t test of independent samples to examine the difference be- tween attitudes towards the Hebrew language by gender. Attitude dimensions Mean and (S.D.) Males Females (N = 257) (N = 359) S.D. Attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign/second language 2.99 )0.76( 3.16 )0.86( ** 2.57− Attitudes towards the language as a school subject 3.67 )0.81( 3.76 )0.74( 1.42− Attitudes towards speakers of the language 2.55 )1.21( 2.67 )1.12( 1.213− Attitudes that reflect motivation for learning the language 3.63 )0.76( 3.76 )0.68( * 2.124− General Attitudes 3.31 )0.58( 3.44 )0.58( ** 2.643− Note: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. The Third Research Hypothesis There is a positive correlation between the community sup- port and the students’ attitudes towards learning Hebrew as a foreign/second language and the willingness to communicate in it. An examination of Tables 4 and 5 shows average support of the community and family (mother, father and friends) to learn the foreign/second language, as perceived by the students in this study (Table 4). To examine the correlation between the community support as perceived by the respondents, their attitudes towards the foreign language and their willingness to communicate in it, Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated and positive correlations were detected between community support and the attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign/second language and willingness to communicate in it (Table 5). Regression analysis in Table 6 indicates that the attitudes towards the Hebrew language can be explained by the dimen- sions of the mothers’ and friends support (F (3609) = 54.23, P < 0.001); the predicting variables explained 21% of the vari- ance of attitudes towards Hebrew language. Regression analysis also indicates that it is possible to explain attitudes towards Hebrew as a school subject by the support of friends (F (3609) = 2.80, P < 0.05). The predicting variable explains 0.09% of the variance of attitudes towards Hebrew as a school subject (Table 5). Discussion First, we stress that in relation to the Arab residents of East Jerusalem, the Hebrew language has two dimensions: The first refers to communication with the Jewish residents, making contact with government and municipal institutions and commercial practices and employment of residents. In this re- spect, Hebrew can be defined as a second language for all pur- poses. The second dimension refers to Arab students of East Jeru- salem studying Hebrew as a foreign language, because it is not included in the Towjihi examinations (Bagrouth). Moreover, Hebrew is considered as a second foreign language, for the first foreign language is English (from conversations with Ms. So- heila Abu-Ghosh, Deputy Director of the Arab sector in the Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1001  S. ILAIYAN Table 4. Breakdown of social support as perceived by students. Support Social support Yes No Father 298 (46.5%) 318 (49.6%) Mother 315 (49.0%) 303 (47.1%) Friends 270 (42.0%) 345 (53.7%) Table 5. Spearman correlation coefficients between community support and the attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign/second language and willingness to communicate in it. Factor\Support Father N = 616 Mother N = 616 Friends Attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign/second language ** 0.40− ** 0.45− ** 0.35− Attitudes towards the language as a school subject −0.03 −0.05 0.04 Attitudes towards speakers of the language * 0.16 ** 0.17 ** 0.11 Attitudes that reflect motivation for learning the language * 0.19− ** 0.23− ** 0.14− General attitudes ** 0.16− ** 0.19− ** 0.11− Willingness to communicate in class 0.02− 0.07− 0.02 Willingness to communicate outside of class * 0.12 ** 0.11 0.08 Note: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Education Directorate of Jerusalem: since before the Oslo agreement in East Jerusalem, Arab students learned according to the Jordanian education law; and after the agreement, they adopted studying according to the plan of the Palestinian Au- thority (Hassona, 1998). Therefore, in our discussion we shall refer to Hebrew as a foreign/second language. The first hypothesis discusses the relationship between atti- tudes towards Hebrew as a foreign/second language and the willingness to communicate in it. The study findings indicate statistically significant positive correlations between the dimensions of attitudes towards He- brew and the dimensions of willingness to communicate in it, except the dimension “attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign/ second language”. This seems to be reasonable, that students are ready, apparently, to learn the language and communicate in it due to instrumental and necessary thing to learn that language in order to communicate on a commercial basis, but at the same time they express less positive attitude towards the Hebrew language. Positive correlations between the attitudes and will- ingness dimensions indicate that the higher students’ attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign/second language are—the higher the level of willingness to communicate in this language. Attitudes towards Hebrew as a school subject scored more positive than attitudes towards speakers of the language. This finding may be explained by the conflict situation between the Palestinian people and the State of Israel; thus students’ hostil- ity is directed more towards the people of Israel than for the language. In fact, there are minorities who study the language only for useful purposes. For example, Arabs in Israel acquire the language, generally, in non-formal education, for work or to communicate with Israeli in everyday life. Unlike the immi- grants, they do not identify with the Jewish people, but they are loyal to the Palestinian people and feel complete solidarity with the Arabic language; and they are not interested in the language, Jewish and Israeli culture, but because they see learning He- brew as a practical value (Spolsky & Cooper, 1991). The findings confirm the work of the Brosh (1988) and re- sults of other studies that show that attitudes towards language acquisition have an effect on willingness to communicate in a foreign language (McIntyre et al., 2003; Yashima et al., 2004). It is likely that the context of the socio-political and social situation in which foreign/second language is taught (which is actually the language of conflict—Abu Rabia, 1999) has an effect on attitudes of acquiring and use of a foreign/second language. It also reflected in the image of the conflict in which the State of Israel is involved with the Arab countries, in gen- eral, and Palestinians in particular. The positive score of general attitudes towards the Hebrew as a foreign/second language is due to the fact that the student was exposed to the Hebrew language on daily basis when he comes into contact with the Jewish population. In employment, gain- ing control of the target language has an instrumental signifi- cance. Avoiding acquisition of the target language or settling for a little control may reduce the employment opportunities of the individual (Menachem & Geist, 1999). Element of exposure is found in the study of Bdair (1990) as a dominant variable in learning Hebrew, and is associated with informal situations of interaction with speakers of foreign/second language. The relatively high score of the attitudes dimension reflects motivation to learn Hebrew as a foreign/second language. Such attitudes towards a language and its speakers constitute an im- portant role in language acquisition, and have a direct impact on the achievement scores in the foreign/second language. Motivation is a significant component of learning a foreign/ second language and positive attitudes towards the target lan- guage have a positive effect on motivation to acquire the for- eign/second language. This is consistent with the findings of Clement, Dornyei, & Noels (1994); McIntyre, Baker, Clement, & Donovan (2003) who indicate that the motivation for learn- ing the language is an important factor in learning a foreign/ second language. It has more pronounced effect in this context than in the context of mother tongue acquisition. This points to the instrumental motive for language acquisition, and supports the work of Bdair (1990), Abu-Rabia (1999), Ilaiyan & Ara- yeda (2008) and Ilaiyan (2011). The findings contradict those of Bchor (1992), Brosh & Ben Rafael (1994) and Dunitz-Schmidt (2004), and they indicate that the attitudes of the Arab students in East Jerusalem towards Hebrew as a foreign/second language are more positive than their willingness to communicate in Hebrew, whether inside or outside the classroom. The findings reinforce the findings of Tahar (2005) about Jewish students’ attitudes towards Arabic as a foreign language. At the same time, the findings of this study contradict other findings in her study that reported a statistically significant positive correlation between the attitudes of the Arab students within the State of Israel and their willingness to communicate in Hebrew. This is due to their different sociopolitical status of the East Jerusalem Arabs (who efuse to recognize Israel as a r Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1002  S. ILAIYAN Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1003 Table 6. Multiple regression to predict attitudes and willingness to communicate on social support (N = 616). Dependent variable Predicting support variable B β t R2 Father 0.09− 0.06− 0.83− Mother 0.53− 0.33− ** 4.74− Attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign/second language Friends 0.19− 0.11− * 2.42− 0.211 Father 0.004− 0.002− 0.03− Mother 0.21− 0.14− 1.76− Attitudes towards the language as a school subject Friends 0.20 0.13 * 2.47 0.014 Father 0.15 0.07 0.87 Mother 0.28 0.12 1.59 Attitudes towards speakers of the language Friends 0.01− 0.006− 0.11− 0.032 Father 0.003− 0.09 0.04− Mother 0.23− 0.09 2.59− Attitudes that reflect motivation for learning the language Friends 0.01 0.06 0.22 0.052 Father 0.20 0.12 1.55 Mother 0.31− 0.19− 2.40− Willingness to communicate in class Friends 0.04 0.02 0.43 0.01 Father 0.15 0.08 1.02 Mother 0.09 0.05 0.61 Willingness to communicate outside of class Friends 0.003− 0.002− 0.03− 0.004 *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. sovereign state) and the Arabs in Israel (who accept and recog- nize their Israeli citizenship). These findings contradict the findings of Ilaiyan & Arayeda (2008) for the non-Jewish residents of the Golan Heights, who have a higher willingness to communicate in Hebrew as a for- eign/second language, although their sociopolitical situation is similar to that of the Arabs of East Jerusalem. The Second Research Hypothesis Relationship between the language and its speakers’ gender gained consideration around the world. In recent decades, sev- eral studies that have examined this relationship in different languages appeared in the literature. Researchers are trying to determine “Is there a relationship between gender and lan- guage?” Or “Is there a connection between gender and lan- guage acquisition?” In other words, does gender affect lan- guage acquisition, or create different attitudes toward the ac- quisition? This research hypothesis dealt with differences in attitudes to the Hebrew language as a foreign/second language on the basis of gender. It should be noted that statistically significant dif- ferences were found between boys and girls in the following dimensions: 1) attitudes toward Hebrew as a Foreign Language, 2) attitudes that reflect motivation for learning the Hebrew language, and 3) general attitudes—attitudes of the girls were more positive than among boys. This finding can be explained by the fact that the girls are generally more conformist, more disciplined and at this age are exposed less than boys to political identification, and less af- fected by the street than boys, due to religious beliefs, and so- cial-traditional-conservative mentality. One may assume that girls do not link the situation to the subject of conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, but con- sider language acquisition as an act of learning another foreign language alone. This is consistent with the findings of Xin (2008), who indicates that girls like to learn English and have expressed interest in learning English as a foreign language. They argued that girls learn the foreign language as a hobby, or acquisition of knowledge—some of them noted, “We love the language.” Others explained it as an effort to improve their abilities to communicate with the community of foreign lan- guage or improve their social status. Whereas boys’ attitudes to acquire a foreign language stem from other motives; Tannen (1990) notes that men see the language as an instrumental need, while women see it as a need for social communication. Our research findings differ from those of Bdair (1990), who pointed out the difference between the attitudes of boys and girls in the Arab society in Israel toward Hebrew as a foreign/ second language and towards the people speaking the language. More positive attitudes were found among boys than among girls. The special status of East Jerusalem Arabs could explain this difference. Presumably, the argument of Coates (1986) that language  S. ILAIYAN acquisition among girls better and faster than that of boys also expressed positive attitudes of girls (compared with boys) to the acquisition of Hebrew as a foreign language. The third hypothesis is related to the correlation between the community support and attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign/ second language and willingness of students to communicate in it. The results show moderate support of society and the family (father, mother) to learn Hebrew as a foreign/second language, as it is perceived by the students in this study. Family support is stronger than the community support. This can be explained by the family tendency to think for the long term about the benefits of knowing foreign/second language, which may contribute to the development of their children, and open more opportunities for employment. This is consistent with the findings of Spolsky & Cooper (1991). “Arabs in East Jerusalem study the language for employment or for ‘knowl- edge of the enemy’ to manage their daily life with the Jews. They need only the spoken Hebrew on the labor market; and that they gain usually without much difficulty” (Spolsky & Cooper, 1991). Friends’ effect is especially evident among members of the same age group, and plays a major role and even more important in adolescence. After all, the socialization processes direct the perceptions and behavior of teens and re- quire them to adapt to the social structure of the family. This process has an important element in to be learned. Notably, the negative relationship between students' attitudes towards Hebrew as a school subject and family and social sup- port for their children to study Hebrew as a second language is because the students perceive Hebrew as equivalent to the rest of the other subjects; based on this, they deal with it. Attitudes can be acquired by imitation and identification with social attitudes; as over time, these attitudes become an integral part of the children’s value systems (Shapira & Ben Eliezer, 1986). This finding is also reflected in the study of Easton & Dennis (1973), which points out the considerable influence of adolescent peers; teenagers adopt the common norms of the group and act accordingly. The findings show that the peers influence in adolescence is significant and influence of parents, on the other hand, is re- duced when the adolescent develops an independent identity and looks for independent sociopolitical opinions in the family and society. Summary and Recommendations for Further Research The purpose of this study was to examine the attitudes of eighth grade Arab students of East Jerusalem towards learning Hebrew as a foreign/second language and their willingness to communicate in this language, and the social support for learn- ing the target language. The study was based on social theories of Schumann (1978). Our results show a positive relationship between the stu- dents’ attitudes towards Hebrew as a foreign/second language and the willingness to communicate in this language, which is surprising. The findings found more positive attitudes among girls than boys including the attitudes that reflect motivation to learn the language. In addition, a positive average correlation was detected between the community support as perceived by the respondents and attitudes towards Hebrew and willingness to communicate it. Finally, it is recommended to examine the different strata of the Arab population in East Jerusalem, such as: academics, independent teachers, merchants and women and their relation to Hebrew as a foreign/second language, with a comparison between the different groups, since the uniqueness of the group of students of this study limits somewhat the possibility of gen- eralization of the findings to the entire Arab population in East Jerusalem. REFERENCES Abu-Rabia, S. (1999). Towards a second-language model of learning in problematic social contexts: The case of Arabs learning Hebrew in Israel. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 2, 109-125. doi:10.1080/1361332990020108 Ader, Z. (1965). Humanity subjects in secondary education. Or Yehuda: Davir. [Hebrew] Attili, L. (1999). Relationship between attitudes toward the Hebrew language, its speakers their culture, and the Middle East peace process and the achievements in Hebrew in Arab high schools in Is- rael. Master Thesis, Tel Aviv: University of Tel Aviv. Bassal, A. (2007). Teaching Hebrew as a second language among Arab students: mother tongue involvement and contribution of compara- tive grammar. In S. Ilaiyan, Y. Avishur, N. Kassem, & M. Hugirat (Eds.), Attribution book for Dr. Najib Nabwani: Studies in philoso- phy, education and science. Haifa: Arabic College for Education— Haifa. Bchor, D. (1992). Attitudes and achievement in written Arabic in sixth graders attending mixed and unmixed classes. Master Thesis, Tel Aviv: University of Tel Aviv. Bdair, Z. (1990). Attitudes and exposure to target language and the relation to success in learning a second language. Master Thesis, Tel Aviv: University of Tel Aviv. Bekerman, Z., & Horenczyk, G. (2004). Arab-Jewish bilingual coedu- cation in Israel: A long-term approach to intergroup conflict resolu- tion. Journal of Social Issues, 60, 389-403. doi:10.1111/j.0022-4537.2004.00120.x Brosh, H. (1988). Impact of learning spoken Arabic in elementary school on achievements in literary Arabic in the seventh grade of the middle school. Doctoral Dissertation, Tel Aviv: University of Tel Aviv. [Hebrew] Brosh, H., & Ben Rafael, A. (1994). Language policy against social reality: Arabic in the Hebrew school. Eyonim Bahenokh, 59-60, 335-350. Central Bureau of Statistics (2008). Statistical Abstract of Israel, No. 59. Jerusalem: CBS. Clement, R., Dornyei, Z., & Noles, K. (1994). Motivation, self confi- dence, and group cohesion in the foreign language classroom. Lan- guage Learning, 44, 411-448. doi:10.1111/j.1467-1770.1994.tb01113.x Coates, J. (1986). Women, men and language: A sociolinguistic account of sex differences in language. London & New York: Longman. Dbiat, N. (2004). Use of the masculine rather than feminine voice by Arabic-speaking women in the Galilee and the Triangle. Master The- sis, Tel Aviv: University of Tel Aviv. Donitsa-Schmidt, S. (2004). If only I know English: Attitudes toward English among Russian federation newcomers. Education and about, 26, 167-177. doi:10.1111/j.0026-7902.2004.00226.x Dornyei, Z. (2003). Attitudes, orientation, and motivations in language learning: Advances in theory, research, and applications. Language Learning, 53, 3-32. doi:10.1111/1467-9922.53222 Easton, D., & Dennis, J. (1973). Apolitical theory of political socializa- tion. In J. Debbesm (Ed.), Socialization to Politics (pp. 32-55). New York: Wiley. Eir Amim Association (2005). Shortage and a barrier: A report on denial of right to education of Palestinians in East-Jerusalem. Jeru- salem: Eir Amim. Ellis, R. (1994). The study of second language acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Gardner, R. C. (1979). Social psychological aspects of second language Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1004  S. ILAIYAN Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1005 acquisition. In H. Gillis, & S. T. Clair (Eds.), Language and social psychology. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Gardner, R. C. (1980). On the validity of affective variables in second language acquisition. Conceptual, contextual and statistical consid- eration. Language Learning, 30, 255-270. doi:10.1111/j.1467-1770.1980.tb00318.x Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second language learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House Publishers. Genesse, F., Rogers, P., & Holobow, N. (1983). The social psychology of second language learning: Another point of view. Language Learning, 33, 224-309. Genesse, F., Rogers, P., & Holobow, N. (1982). Psychology of second language learning: Another point of view, Tesol paper (Abstract). Montreal, PQ: McGill University. Giles, H., & Byrne, J. L. (1982) An intergroup approach to second language acquisition. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural De- velopment, 3, 17-40. doi:10.1080/01434632.1982.9994069 Hassona, Z. (1998). The Jordanian-Palestinian relations in the field of education. Nablus: Palestinian Research Center. Ilaiyan, S. (2011). Attitudes towards acquiring Hebrew as a second language among the Golan Heights students following the Six Day War in 1967 and the Golan annexation to Israel in 1981. IiCCOSEC, 18, 61-87. Ilaiyan, S., & Arayeda, A. (2008). Attitudes towards the acquisition of Hebrew as a second language among students of the Golan in the shadow annexation. Madarat, 2, 489-526. Inbar, O., Donitsa-Schmidt, S., & Shohamy, E. (2001). Students’ moti- vation as a function of language learning: The teaching of Arabic in Israel. In Z. Dornyei, & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and second language acquistion. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. Kramarae, C., Schulz, M., & O’Barr, W. M. (Eds.) (1984). Language and Power. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Krashen, S. D. (1981). Second language acquisition and second lan- guage learning. Oxford: Pergamon Press. Lakoff, R. (1975). Language and woman’s place. New York: Harper Colophon Books. Lakoff, R. (1972). Language in context. Language, 48, 907-927. doi:10.2307/411994 Maltz, D., & Borker, R. (1982). A Cultural approach to male-female miscommunication. In J. J. Gumperz (Ed.), Language and social identity. New York: Cambridge University Press. McIntyre, P. D., Baker, S. C., Clement, R., & Conrod, S. (2001). Will- ingness to communicate, social support and language learning orien- tations of immersion students. Studies in Second Language Acquisi- tion, 23, 369-388. doi:10.1017/S0272263101003035 McIntyre, P. D., Baker, S. C., Clement, R., & Donovan, L. A. (2003). Talking in order to learn: Willingness to communicate and intensive language programs. Canadian Modern Language Review, 59, 589- 607. doi:10.3138/cmlr.59.4.589 Menachem, G., & Geist, A. (1999). Language, employment and con- nection to Israel among immigrants from the Russian federation in the ’90s. Magamot, 1, 131-148. Mutchnik, M. (1992). Language differences between men and women in the Hebrew press. Doctoral Dissertation, Tel Aviv: Bar Ilan Uni- versity. Nevo, N. (2005). Teaching Hebrew as a second language to children and youth, teaching Hebrew as an additional language in preschool in the Diaspora: Study program “Nitsanim”. Hed Haolpan Hahadash, 88, 1-16. Oller, J. W. (1981). Research on the measurement of affective variables: Some remaining questions. In Language Acquisition Research (pp. 14-27). Rowley, MA: Newbury House. Olstein, A. (1997). Study of second language acquisition and teaching of language—What have we learned so far? Hed Haolpan Hahadash, 73, 53-57. Olstein, A. (1998). Additional language in early childhood. Hed Hagan, 62, 392-395. Eir Amim and the Association for Civil Rights (2010). The Palestinian Arab education system in East Jerusalem. Jerusalem: Eir Amim. Rosenhouse, J. (1998). Women’s speech and language variation in Arabic dialects. Al-‘Arabiyya, Journal of the American Association of Teachers of Arabic, 31, 123-152. Schumann, J. H. (1978). The pidginization process: A model for second language acquisition. Rowley Mass: Newbury House. Shapira, J., & Ben Eliezer, A. (1986). Foundations of sociology. Tel Aviv: -‘Am Oved. Spender, D. (1980). Man made language. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Spolsky, B. (1989). Conditions for second language learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Spolsky, B. (1969). Attitudinal aspects of second language. Language Learning, 19, 271-283. doi:10.1111/j.1467-1770.1969.tb00468.x Spolsky, B., & Cooper, R. (1991). The language of Jerusalem. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Spolsky, B., & Shohamy, E. (1999). The languages of Israel: Policy, ideology and practice. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. Tahar, L. (2005). Attitudes towards foreign language (Arabic/ Hebrew) and readiness to communicate in this language among Jewish and Arab students in Israel, attending regular schools and the bilingual school in Neve Shalom. Master Thesis, Tel Aviv: University of Tel Aviv. Tannen, D. (1990). You just don’t understand: Women and men in conversation. New York: Ballantine Books. Tannen, D. (1993). Gender and conversational interaction. New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press. Taylor, O. M., Meynard, R., & Rhenolt, E. (1977). Thereat to ethnic identity and second language learning. In H. Giles (Ed.), Language ethnicity and intergroup relations. London: Academic Press. Vergen, Y. (2006). Education in East Jerusalem. Jerusalem: The Knesset Research and Information Center. Xin, X. (2008). On gender differences in language acquisition. Sino-US English Teaching, 5, 6-10. Yashima, T., Zenuk-Nishide, L., & Shimize, K. (2004). The influence of attitudes and affect on willingness to communicate and second language communication. Language Learning, 54, 119-152. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9922.2004.00250.x Zeevi, A. (1995). Comparison of motivation and attitudes of students toward school subjects: English, Arabic and French. Master Thesis, Tel Aviv: University of Tel Aviv.

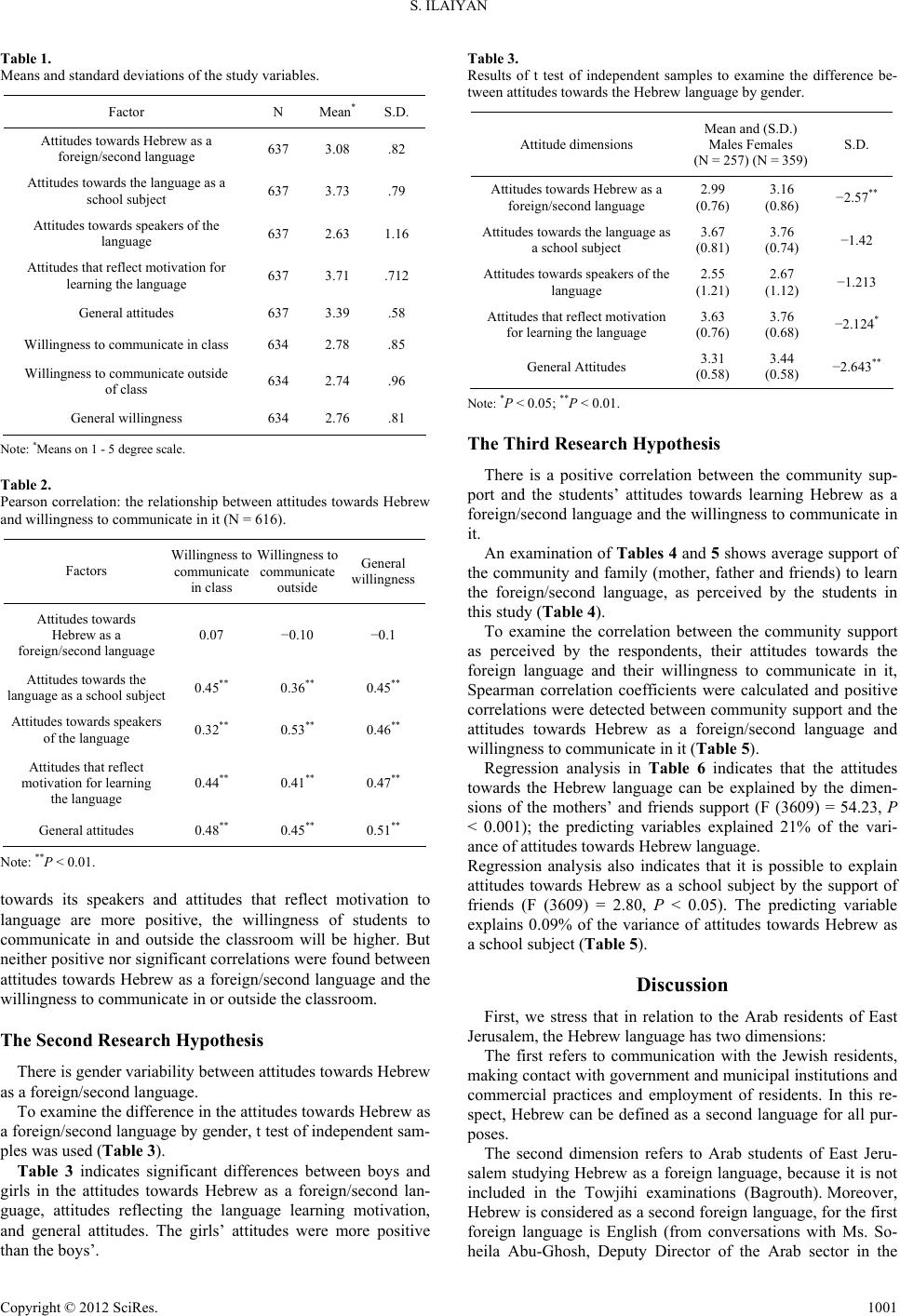

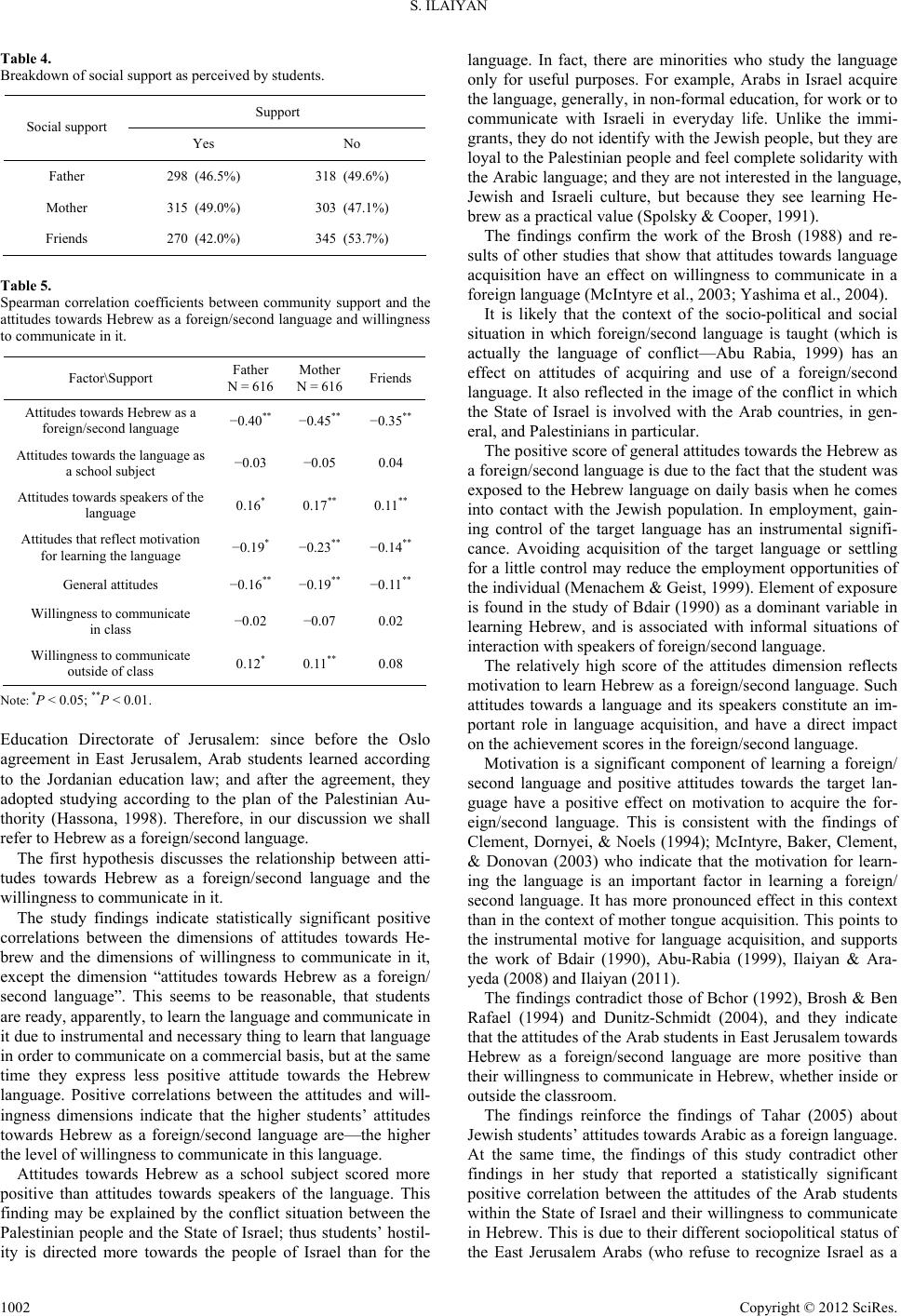

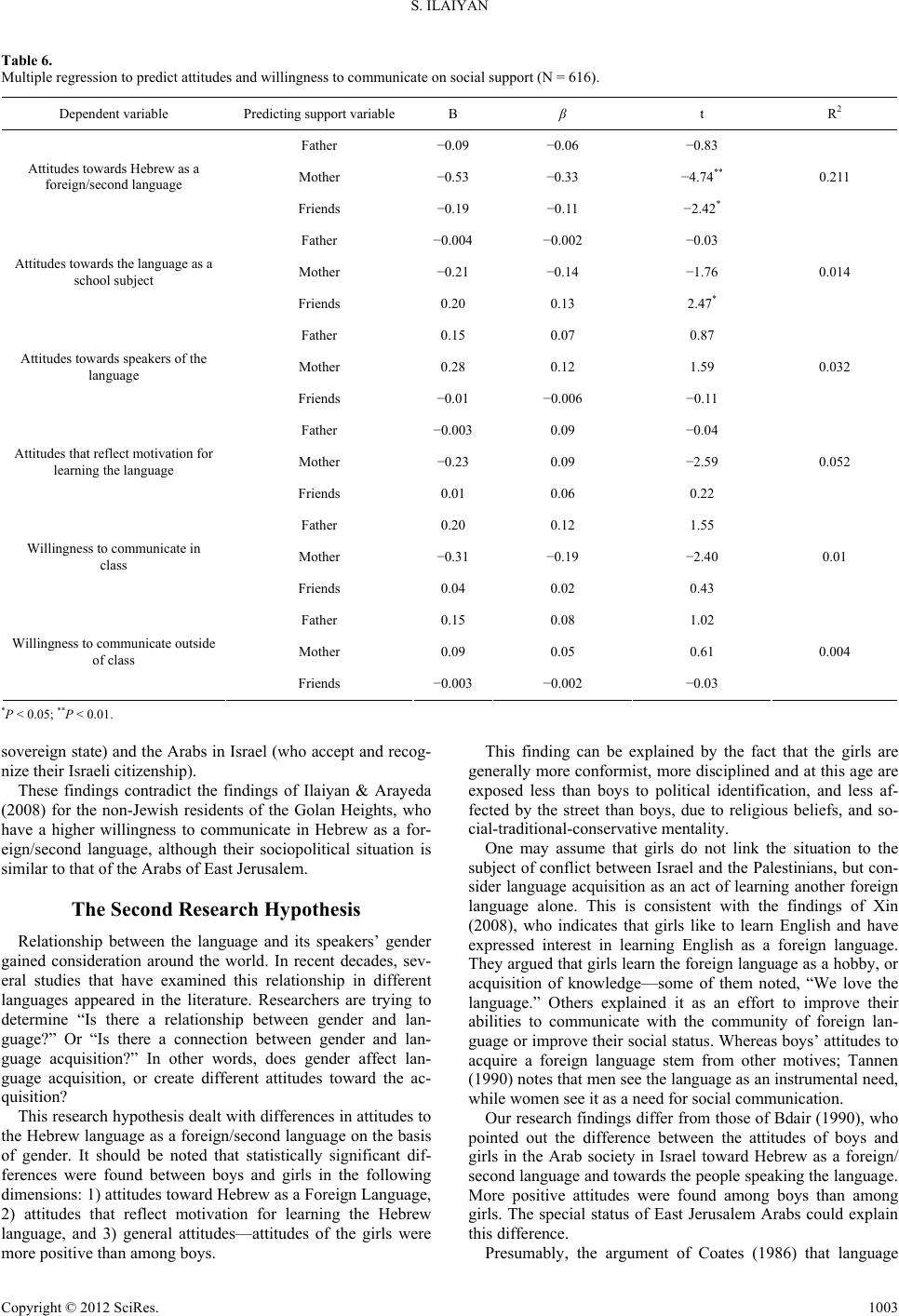

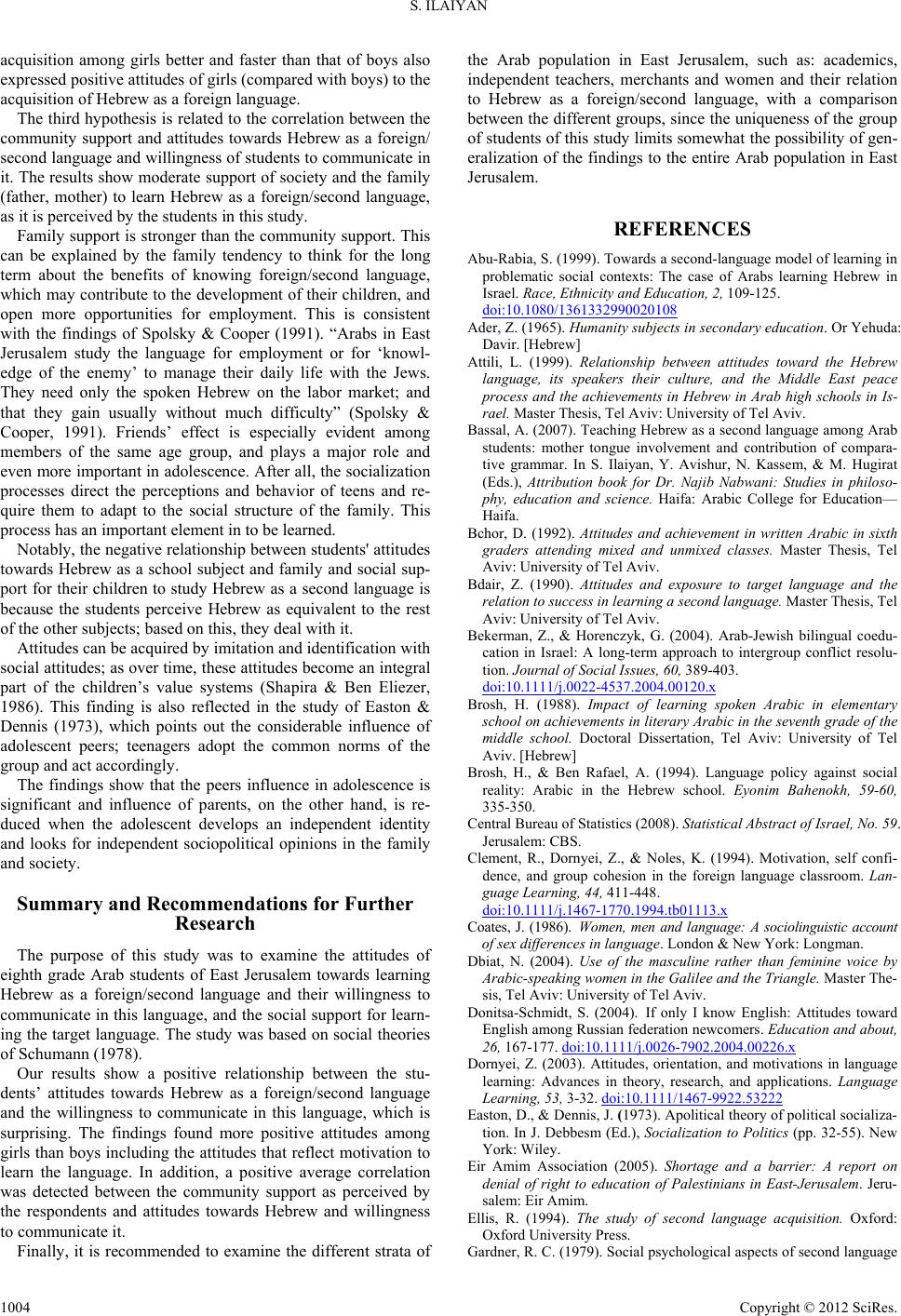

|