Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

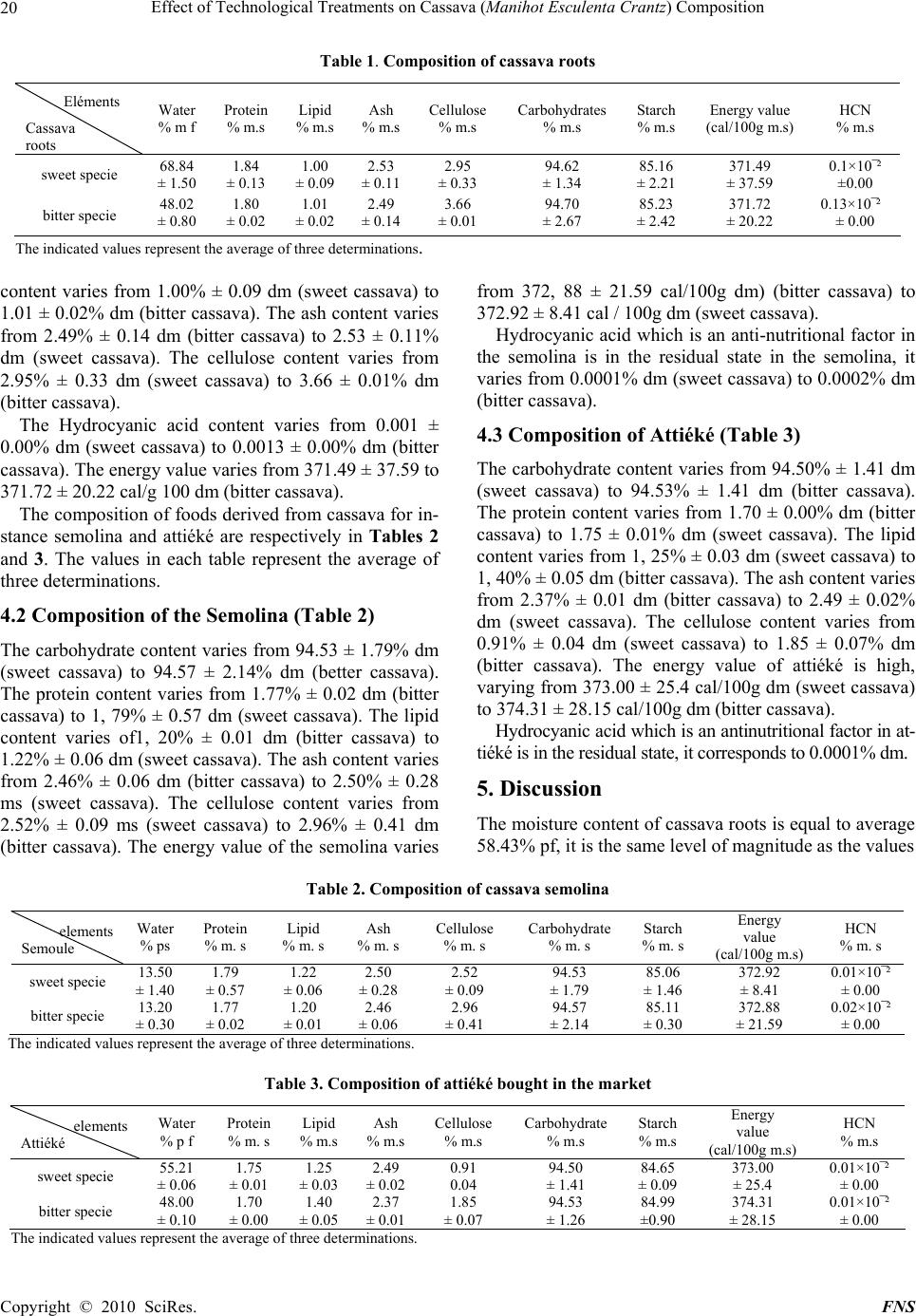

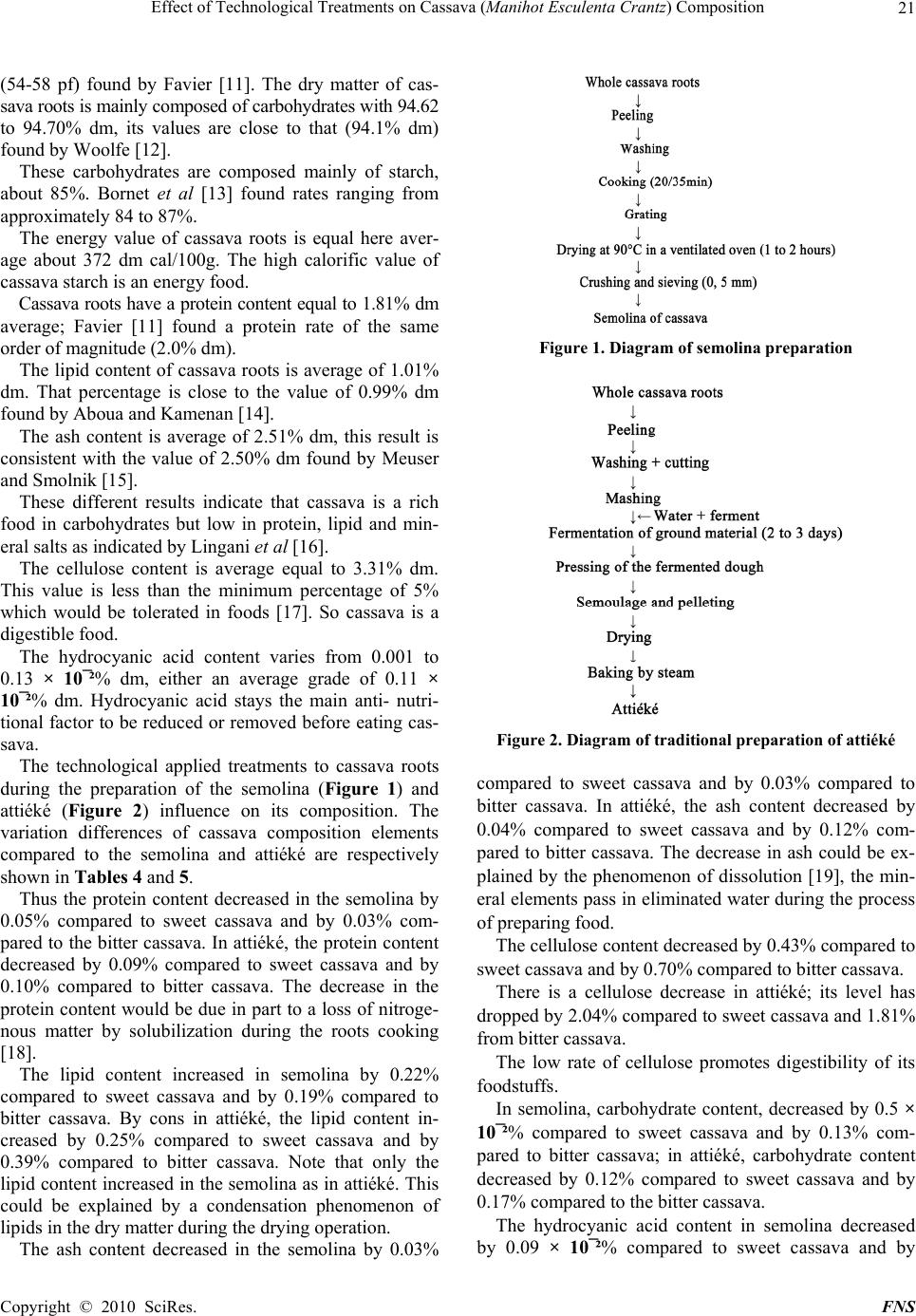

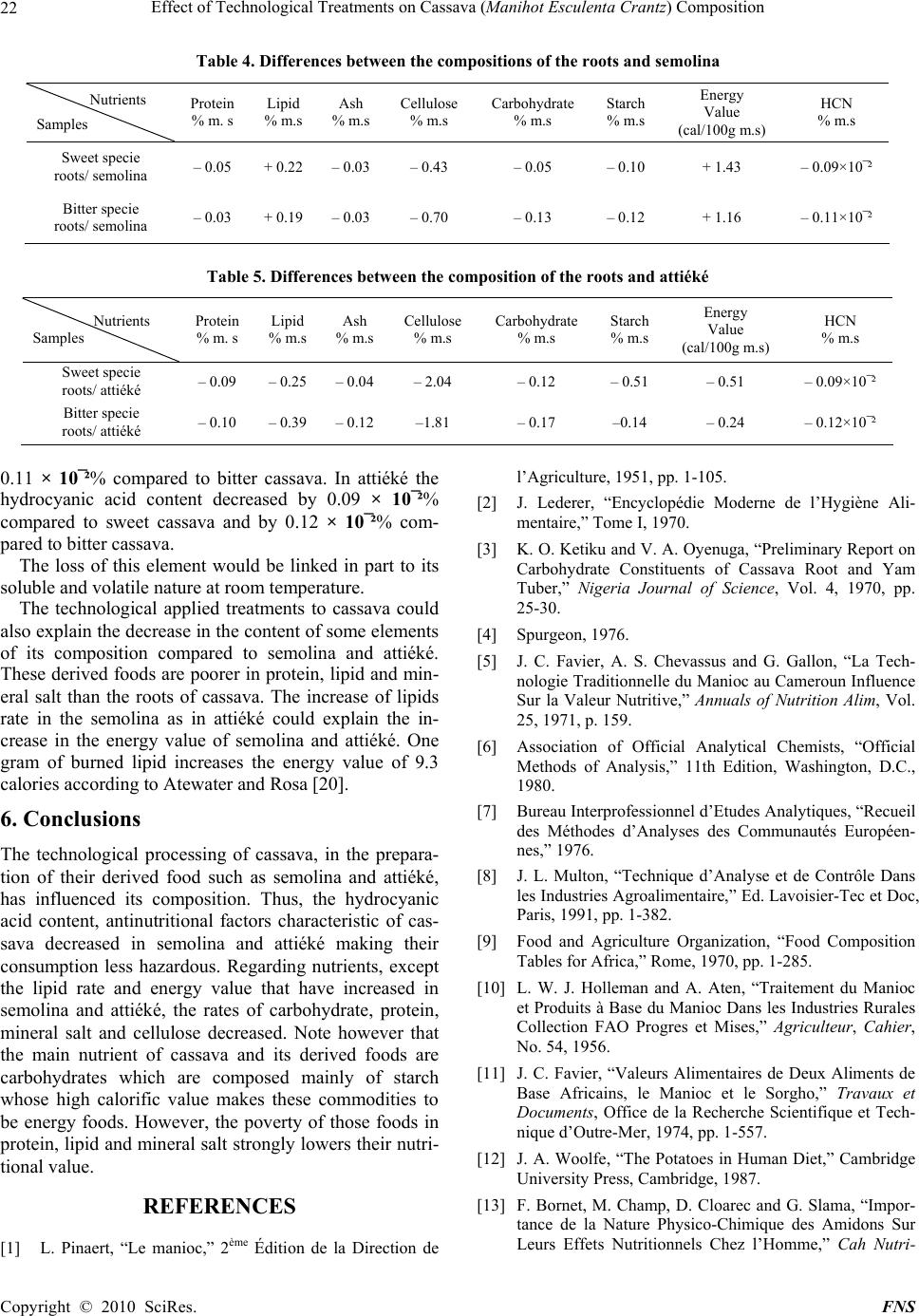

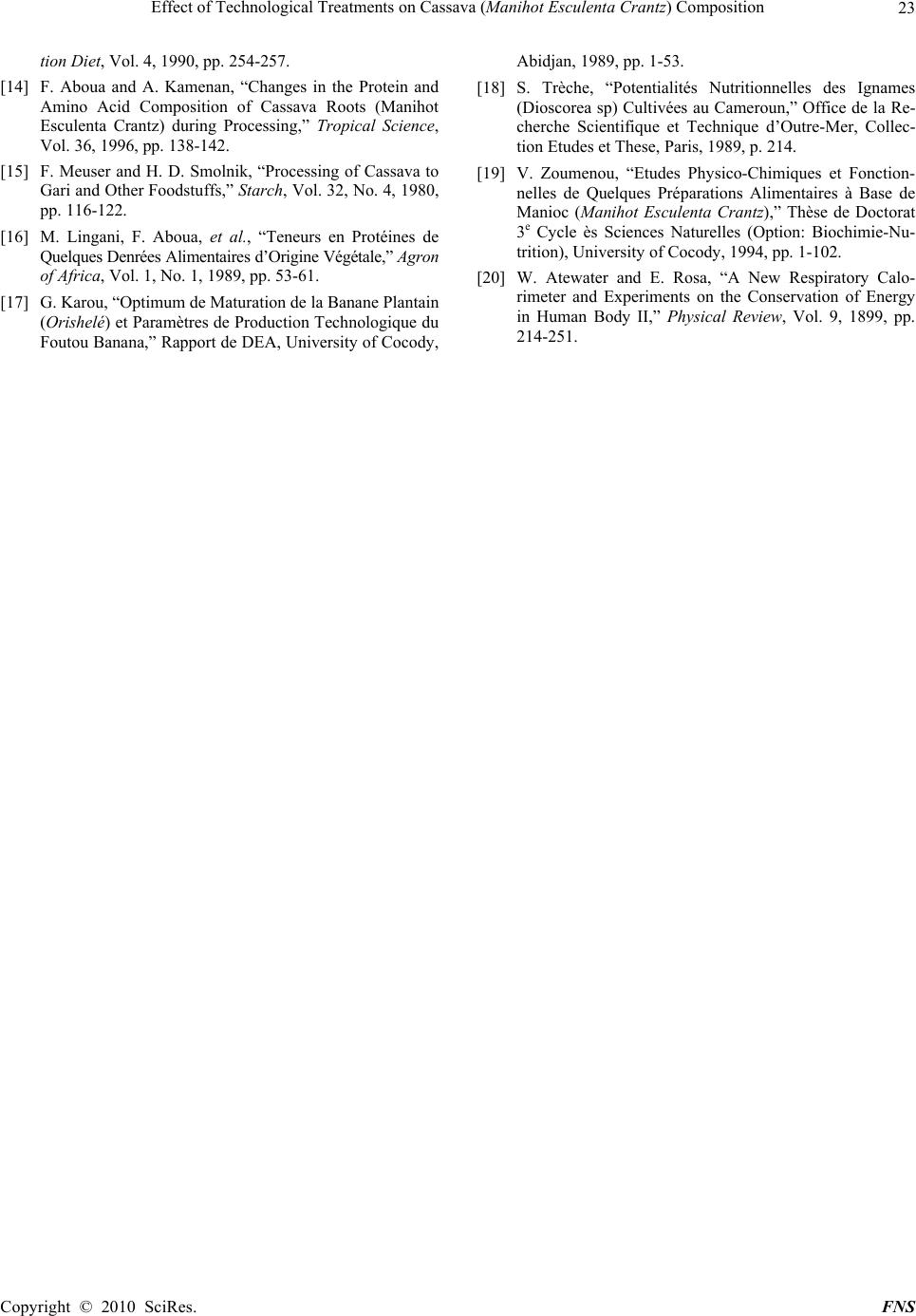

Food and Nutrition Sciences, 2010, 1, 19-23 doi:10.4236/fns.2010.11004 Published Online July 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/fns) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. FNS 19 Effect of Technological Treatments on Cassava (Manihot Esculenta Crantz) Composition Sahoré Drogba Alexis*, Nemlin Gnopo Jean UFR des Sciences et Technologies des Aliments, Université d’Abobo-Adjamé, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. Email: alexissahore@yahoo.fr Received March 30th, 2010; revised June 26th, 2010; accepted July 8th, 2010. ABSTRACT The composition of cassa va roots and those of its derived food (attiéké and semolina), were determined. The compara- tive study of the cassava roots composition with those of the semolina and attiéké has shown that the technological ap- plied treatments in the preparation of cassava meal and attiéké influenced its composition. Thus, apart from the lipids content and energy values which slightly increased, all the components (protein, ash, cellulose, carbohydrates, starch and hydrocyanic acid ) decreased in food derived from cassava. Keywords: Cassava, Semolina, Attiéké, Composition, Technological Treatment 1. Introduction Cassava has been widespread in all tropical regions of the globe, because of the ease of its culture [1]. However on the nutritional point of view that plant is toxic in all its parts [2]. Indeed the crude cassava roots contain some cyanogenic glycosides. These glycosides are conv er ted in prussic acid (hydrogen cyanide, HCN) when the cells of cassava roots are ruptured. Good methods of preparation and cooking reduce the levels of cyanide and acute poi- soning occurs very rarely. Contrariwise, a chronic toxic- ity due to cyanide appears in case of a high consumption of cassava. Especially when the consumption of iodine and/or proteins is very low [1]. Cassava roots are rich in energy and contain mainly starch and soluble carbohydrates [3]. Although they are low in protein, it is a staple food for about 200 to 300 million people worldwide [4]. Cassava is consumed in various forms [5]. The aim of our work is to study the roots composition of two varieties of cassava and to show the influence of technology on the cassava food value compared to two derived food, semolina and at- tiéké. 2. Material and Methods For this study we used as plant material two varieties of cassava roots, a bitter variety “bouanga Koutouan” and a sweet variety “Bonoua red” and also samples of foods derived from cassava : Attiéké bought in Abidjan market and semolina prepared from studied cassava roots. 3. Chemical Analysis Water content determined by drying at 105°C with con- stant weight [6], the protein content determined by the method of Kjeldahl with 6.25 as conversion factor, the lipid con tent determined by So xhlet extraction with ether, and the ash content determined by incineration at 650°C in muffle furnace [7]; the cellulose content determined by the method of Weender [8], the carbohydrate content determined by difference; the starch content calculated by multiplying the carbohydrate content by the conver- sion factor 0.9, the energy value calculated by equation (4 × protein content) + (9.75 × lipid content) + (4.03 × glucids content) [9]; hydrocyanic acid (HCN) content determined by alkaline titration [10]. 4. Results 4.1 The Composition of Cassava Roots is Given in Table 1 The indicated values represent the average of three de- terminations. The water content varies from 48.02 ± 0.80% (bitter cassava) to 68.84 ± 1.50% (sweet cassav a). The carbohydrate content varies from 94.62% ± 1.34 dm (sweet cassava) to 94.70 ± 2.67% dm (cassava). The starch is the dominant fraction of carbohydrates; it repre- sents 85.16 ± 2.21 - 85.23 ± 2.42% of these carbohydrates. The protein content varies from 1.80% ± 0.02 dm (bitter cassava) to 1.84% ± 0.13 dm (sweet cassava). The lipid  Effect of Technological Treatments on Cassava (Manihot Esculenta Crantz) Composition 20 Table 1. Composition of cassava roots Eléments Cassava roots Water % m f Protein % m.s Lipid % m.s Ash % m.sCellulose % m.s Carbohydrates % m.s Starch % m.sEnergy value (cal/100g m.s) HCN % m.s sweet specie 68.84 ± 1.50 1.84 ± 0.13 1.00 ± 0.09 2.53 ± 0.112.95 ± 0.33 94.62 ± 1.34 85.16 ± 2.21371.49 ± 37.59 0.1×10¯² ±0.00 bitter specie 48.02 ± 0.80 1.80 ± 0.02 1.01 ± 0.02 2.49 ± 0.143.66 ± 0.01 94.70 ± 2.67 85.23 ± 2.42371.72 ± 20.22 0.13×10¯² ± 0.00 The indicated values represent the average of three determinations. content varies from 1.00% ± 0.09 dm (sweet cassava) to 1.01 ± 0.02% dm (bitter cassava). The ash content varies from 2.49% ± 0.14 dm (bitter cassava) to 2.53 ± 0.11% dm (sweet cassava). The cellulose content varies from 2.95% ± 0.33 dm (sweet cassava) to 3.66 ± 0.01% dm (bitter cassava). The Hydrocyanic acid content varies from 0.001 ± 0.00% dm (sweet cassava) to 0.0013 ± 0.00% dm (bitter cassava). The energy value varies from 371.49 ± 37.59 to 371.72 ± 20.22 cal/g 100 dm (bitter cassava). The composition o f foods derived from cassava for in- stance semolina and attiéké are respectively in Tables 2 and 3. The values in each table represent the average of three determinations. 4.2 Composition of the Semolina (Table 2) The carbohydrate content varies from 94.53 ± 1.79% dm (sweet cassava) to 94.57 ± 2.14% dm (better cassava). The protein content varies from 1.77% ± 0.02 dm (bitter cassava) to 1, 79% ± 0.57 dm (sweet cassava). The lipid content varies of1, 20% ± 0.01 dm (bitter cassava) to 1.22% ± 0.06 dm (sweet cassava). The ash content varies from 2.46% ± 0.06 dm (bitter cassava) to 2.50% ± 0.28 ms (sweet cassava). The cellulose content varies from 2.52% ± 0.09 ms (sweet cassava) to 2.96% ± 0.41 dm (bitter cassava). The energy value of the semolina varies from 372, 88 ± 21.59 cal/100g dm) (bitter cassava) to 372.92 ± 8.41 cal / 100g dm (sweet cassava). Hydrocyanic acid which is an anti-nutritional factor in the semolina is in the residual state in the semolina, it varies from 0.0001% dm (sweet cassava) to 0.0002% dm (bitter cassava). 4.3 Composition of Attiéké (Table 3) The carbohydrate content varies from 94.50% ± 1.41 dm (sweet cassava) to 94.53% ± 1.41 dm (bitter cassava). The protein content varies from 1.70 ± 0.00% dm (bitter cassava) to 1.75 ± 0.01% dm (sweet cassava). The lipid content varies from 1, 25% ± 0.03 dm (sweet cassava) to 1, 40% ± 0.05 dm (bitter cassava). The ash content varies from 2.37% ± 0.01 dm (bitter cassava) to 2.49 ± 0.02% dm (sweet cassava). The cellulose content varies from 0.91% ± 0.04 dm (sweet cassava) to 1.85 ± 0.07% dm (bitter cassava). The energy value of attiéké is high, varying from 373.00 ± 25.4 cal/100g dm (sweet cassava) to 374.31 ± 28.1 5 cal/100g dm (bitter cassava). Hydrocyanic acid which is an antinutritional factor in at- tiéké is in the residual state, it corresponds to 0.0001% dm. 5. Discussion The moisture content o f cassava roots is equal to average 58.43% pf, it is the same level of magnitude as the values Table 2. Composition of cassava semolina elements Semoule Water % ps Protein % m. s Lipid % m. s Ash % m. s Cellulose % m. s Carbohydrate % m. s Starch % m. s Energy value (cal/100g m.s) HCN % m. s sweet specie 13.50 ± 1.40 1.79 ± 0.57 1.22 ± 0.06 2.50 ± 0.28 2.52 ± 0.09 94.53 ± 1.79 85.06 ± 1.46 372.92 ± 8.41 0.01×10¯² ± 0.00 bitter specie 13.20 ± 0.30 1.77 ± 0.02 1.20 ± 0.01 2.46 ± 0.06 2.96 ± 0.41 94.57 ± 2.14 85.11 ± 0.30 372.88 ± 21.59 0.02×10¯² ± 0.00 The indicated values represent the average of three determinations. Table 3. Composition of attiéké bought in the market elements Attiéké Water % p f Protein % m. s Lipid % m.s Ash % m.sCellulose % m.s Carbohydrate % m.s Starch % m.s Energy value (cal/100g m.s) HCN % m.s sweet specie 55.21 ± 0.06 1.75 ± 0.01 1.25 ± 0.03 2.49 ± 0.020.91 0.04 94.50 ± 1.41 84.65 ± 0.09373.00 ± 25.4 0.01×10¯² ± 0.00 bitter specie 48.00 ± 0.10 1.70 ± 0.00 1.40 ± 0.05 2.37 ± 0.011.85 ± 0.07 94.53 ± 1.26 84.99 ±0.90 374.31 ± 28.15 0.01×10¯² ± 0.00 The indicated values represent the average of three determinations. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. FNS  Effect of Technological Treatments on Cassava (Manihot Esculenta Crantz) Composition21 (54-58 pf) found by Favier [11]. The dry matter of cas- sava roots is mainly composed of carbohydrates with 94.62 to 94.70% dm, its values are close to that (94.1% dm) found by Woolfe [12]. These carbohydrates are composed mainly of starch, about 85%. Bornet et al [13] found rates ranging from approximately 84 to 87%. The energy value of cassava roots is equal here aver- age about 372 dm cal/100g. The high calorific value of cassava starch is an energy food. Cassava roots have a protein content equal to 1.81% dm average; Favier [11] found a protein rate of the same order of magnitude (2.0% dm). The lipid content of cassava roots is average of 1.01% dm. That percentage is close to the value of 0.99% dm found by Abou a and Kamenan [14]. The ash content is average of 2.51% dm, this result is consistent with the value of 2.50% dm found by Meuser and Smolnik [15]. These different results indicate that cassava is a rich food in carbohydrates but low in protein, lipid and min- eral salts as indicated by Lingani et al [16]. The cellulose content is average equal to 3.31% dm. This value is less than the minimum percentage of 5% which would be tolerated in foods [17]. So cassava is a digestible food. The hydrocyanic acid content varies from 0.001 to 0.13 × 10¯²% dm, either an average grade of 0.11 × 10¯²% dm. Hydrocyanic acid stays the main anti- nutri- tional factor to be reduced or removed before eating cas- sava. The technological applied treatments to cassava roots during the preparation of the semolina (Figure 1) and attiéké (Figure 2) influence on its composition. The variation differences of cassava composition elements compared to the semolina and attiéké are respectively shown in Tables 4 and 5. Thus the protein content decreased in the semolina by 0.05% compared to sweet cassava and by 0.03% com- pared to the bitter cassava. In attiéké, the protein content decreased by 0.09% compared to sweet cassava and by 0.10% compared to bitter cassava. The decrease in the protein content would be due in part to a loss of nitroge- nous matter by solubilization during the roots cooking [18]. The lipid content increased in semolina by 0.22% compared to sweet cassava and by 0.19% compared to bitter cassava. By cons in attiéké, the lipid content in- creased by 0.25% compared to sweet cassava and by 0.39% compared to bitter cassava. Note that only the lipid content increased in the semolina as in attiéké. Th is could be explained by a condensation phenomenon of lipids in the dry matter during the drying operation. The ash content decreased in the semolina by 0.03% Figure 1. Diagram of semolina preparation Figure 2. Diagram of traditional preparation of attiéké compared to sweet cassava and by 0.03% compared to bitter cassava. In attiéké, the ash content decreased by 0.04% compared to sweet cassava and by 0.12% com- pared to bitter cassava. The decrease in ash could be ex- plained by the phenomenon of dissolution [19], the min- eral elements pass in eliminated water during the process of preparing food. The cellulose content decreased by 0.43% compared to sweet cassava and by 0.70% compared to bitter cassava. There is a cellulose decrease in attiéké; its level has dropped by 2.04% compared to sweet cassava and 1.81% from bitter cassava. The low rate of cellulose promotes digestibility of its foodstuffs. In semolina, carbohydrate content, decreased by 0.5 × 10¯²% compared to sweet cassava and by 0.13% com- pared to bitter cassava; in attiéké, carbohydrate content decreased by 0.12% compared to sweet cassava and by 0.17% compared to the bitter cassava. The hydrocyanic acid content in semolina decreased by 0.09 × 10¯²% compared to sweet cassava and by Copyright © 2010 SciRes. FNS  Effect of Technological Treatments on Cassava (Manihot Esculenta Crantz) Composition 22 Table 4. Differences between the compositions of the roots and semolina Nutrients Samples Protein % m. s Lipid % m.s Ash % m.sCellulose % m.s Carbohydrate % m.s Starch % m.s Energy Value (cal/100g m.s) HCN % m.s Sweet specie roots/ semolina – 0.05 + 0.22 – 0.03– 0.43 – 0.05 – 0.10 + 1.43 – 0.09×10¯² Bitter specie roots/ semolina – 0.03 + 0.19 – 0.03– 0.70 – 0.13 – 0.12 + 1.16 – 0.11×10¯² Table 5. Differences between the composition of the roots and attiéké Nutrients Samples Protein % m. s Lipid % m.s Ash % m.sCellulose % m.s Carbohydrate % m.s Starch % m.s Energy Value (cal/100g m.s) HCN % m.s Sweet specie roots/ attiéké – 0.09 – 0.25 – 0.04– 2.04 – 0.12 – 0.51 – 0.51 – 0.09×10¯² Bitter specie roots/ attiéké – 0.10 – 0.39 – 0.12–1.81 – 0.17 –0.14 – 0.24 – 0.12×10¯² 0.11 × 10¯²% compared to bitter cassava. In attiéké the hydrocyanic acid content decreased by 0.09 × 10¯²% compared to sweet cassava and by 0.12 × 10¯²% com- pared to bitter cassava. The loss of this element would be linked in part to its soluble and volatile nature at room temperature. The technological applied treatments to cassava could also explain the decrease in the content of some elements of its composition compared to semolina and attiéké. These derived foods are poorer in protein, lipid and min- eral salt than the roots of cassava. The increase of lipids rate in the semolina as in attiéké could explain the in- crease in the energy value of semolina and attiéké. One gram of burned lipid increases the energy value of 9.3 calories according to Atewater and Rosa [20]. 6. Conclusions The technological processing of cassava, in the prepara- tion of their derived food such as semolina and attiéké, has influenced its composition. Thus, the hydrocyanic acid content, antinutritional factors characteristic of cas- sava decreased in semolina and attiéké making their consumption less hazardous. Regarding nutrients, except the lipid rate and energy value that have increased in semolina and attiéké, the rates of carbohydrate, protein, mineral salt and cellulose decreased. Note however that the main nutrient of cassava and its derived foods are carbohydrates which are composed mainly of starch whose high calorific value makes these commodities to be energy foods. However, the poverty of those foods in protein, lipid and mineral salt strongly lowers their nutri- tional value. REFERENCES [1] L. Pinaert, “Le manioc,” 2ème Édition de la Direction de l’Agriculture, 1951, pp. 1-105. [2] J. Lederer, “Encyclopédie Moderne de l’Hygiène Ali- mentaire,” Tome I, 1970. [3] K. O. Ketiku and V. A. Oyenuga, “Preliminary Report on Carbohydrate Constituents of Cassava Root and Yam Tuber,” Nigeria Journal of Science, Vol. 4, 1970, pp. 25-30. [4] Spurgeon, 1976. [5] J. C. Favier, A. S. Chevassus and G. Gallon, “La Tech- nologie Traditionnelle du Manioc au Cameroun Influence Sur la Valeur Nutritive,” Annuals of Nutrition Alim, Vol. 25, 1971, p. 159. [6] Association of Official Analytical Chemists, “Official Methods of Analysis,” 11th Edition, Washington, D.C., 1980. [7] Bureau Interprofessionnel d’Etudes Analytiques, “Recueil des Méthodes d’Analyses des Communautés Européen- nes,” 1976. [8] J. L. Multon, “Technique d’Analyse et de Contrôle Dans les Industries Agroalimentaire,” Ed. Lavoisier-Tec et Doc, Paris, 1991, pp. 1-382. [9] Food and Agriculture Organization, “Food Composition Tables for Africa,” Rome, 1970, pp. 1-285. [10] L. W. J. Holleman and A. Aten, “Traitement du Manioc et Produits à Base du Manioc Dans les Industries Rurales Collection FAO Progres et Mises,” Agriculteur, Cahier, No. 54, 1956. [11] J. C. Favier, “Valeurs Alimentaires de Deux Aliments de Base Africains, le Manioc et le Sorgho,” Travaux et Documents, Office de la Recherche Scientifique et Tech- nique d’Outre-Mer, 1974, pp. 1-557. [12] J. A. Woolfe, “The Potatoes in Human Diet,” Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1987. [13] F. Bornet, M. Champ, D. Cloarec and G. Slama, “Impor- tance de la Nature Physico-Chimique des Amidons Sur Leurs Effets Nutritionnels Chez l’Homme,” Cah Nutri- Copyright © 2010 SciRes. FNS  Effect of Technological Treatments on Cassava (Manihot Esculenta Crantz) Composition23 tion Diet, Vol. 4, 1990, pp. 254-257. [14] F. Aboua and A. Kamenan, “Changes in the Protein and Amino Acid Composition of Cassava Roots (Manihot Esculenta Crantz) during Processing,” Tropical Science, Vol. 36, 1996, pp. 138-142. [15] F. Meuser and H. D. Smolnik, “Processing of Cassava to Gari and Other Foodstuffs,” Starch, Vol. 32, No. 4, 1980, pp. 116-122. [16] M. Lingani, F. Aboua, et al., “Teneurs en Protéines de Quelques Denrées Alimentaires d’Origine Végétale,” Ag ron of Africa, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1989, pp. 53-61. [17] G. Karou, “Optimum de Maturation de la Banane Plantain (Orishelé) et Paramètres de Production Technologique du Foutou Banana,” Rapport de DEA, University of Cocody, Abidjan, 1989, pp. 1-53. [18] S. Trèche, “Potentialités Nutritionnelles des Ignames (Dioscorea sp) Cultivées au Cameroun,” Office de la Re- cherche Scientifique et Technique d’Outre-Mer, Collec- tion Etudes et These, Paris, 1989, p. 214. [19] V. Zoumenou, “Etudes Physico-Chimiques et Fonction- nelles de Quelques Préparations Alimentaires à Base de Manioc (Manihot Esculenta Crantz),” Thèse de Doctorat 3e Cycle ès Sciences Naturelles (Option: Biochimie-Nu- trition), University of Cocody, 1994, pp. 1-102. [20] W. Atewater and E. Rosa, “A New Respiratory Calo- rimeter and Experiments on the Conservation of Energy in Human Body II,” Physical Review, Vol. 9, 1899, pp. 214-251. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. FNS |