Creative Education 2012. Vol.3, Special Issue, 890-895 Published Online October 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.326134 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 890 Designing Relevant and Authentic Scenarios for Learning Clinical Communication in Dentistry Using the Calgary-Cambridge Approach Vicki J. Skinner, Dimitra Lekkas, Tracey A. Winning, Grant C. Townsend School of Dentistry, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia Email: vicki.skinner@adelaide.edu.au Received September 14th, 201 2 ; revised October 17th, 2012; accepted October 25th, 2012 A clinical communication curriculum based on the principles of the Calgary-Cambridge approach was developed during the revision of the 5-year Bachelor of Dental Surgery program (BDS) at The University of Adelaide, Australia. To provide experiential learning opportunities, a simulated patient (SP) program using clinical scenarios was developed. We aimed to design the scenarios to reflect communication de- mands that student clinicians commonly encounter, that integrated process and content, and which stu- dents would perceive as authentic and relevant. Scenarios were based on data from focus groups with re- cent graduates and interviews with clinic tutors. The scenarios combined content (e.g. medical history) and process (e.g. questioning and relationship skills) at a level suitable for junior students. Students evaluated scenario-based materials and SP activities in a survey comprising Likert-scale and open-ended questions. Students rated the materials and SP activities positively; open-ended comments supported the ratings. Scenario-based materials and activities based on student-clinicians’ experiences, were perceived as relevant, realistic, and useful for learning. A curriculum designed on Calgary-Cambridge principles helped address student learning needs at particular stages of their program. Keywords: Clinical Communication Skills; Simulated Patients; Dentistry; Calgary-Cambridge Introduction As part of an overall revision of its five year Bachelor of Dental Surgery (BDS) program, the School of Dentistry, at The University of Adelaide, South Australia is implementing a new clinical communication curriculum in Years 1 - 3. This fits with the recognition of both the importance of patient-centred com- munication in health-care and the need for explicit communica- tion teaching in health-care professions. The immediate and long-term benefits of patient-centred communication include a range of positive outcomes for patients, such as greater satis- faction with care, better diagnosis and treatment, better health outcomes, better adherence to health-care regimens, and fewer patient complaints (Little et al., 2001; Maguire & Pitceathly, 2002; Stewart et al., 1995). Furthermore, patient-centred com- munication is considered a core component of best practice dental education (Sanz et al., 2008). The bodies responsible for quality assurance of dental curricula in Australia and in the UK, the Australian Dental Council (ADC), and the General Dental Council (GDC) respectively, have included communication as a major competence for dental graduates, both in its own right and for underpinning other domains of patient-centred care (ADC 2010; GDC, 2010). Our intent is that the new communi- cation curriculum must use an accepted framework or model for clinical communication skills teaching and learning, it must include evidence-based teaching/learning methods, and it must fit the local curriculum context as well as meeting students’ needs. For this study our goal was to provide authentic and relevant learning activities for Year 2 (junior) dental students. The curriculum required a clear framework; however, the dental education literature lacks accounts of whole-program communication curricula or frameworks. Only a few dental institutions have published accounts of discrete communication modules or courses (Croft et al., 2005; Hannah, Millichamp, & Ayers, 2004). Therefore, frameworks from medical education were considered. The common attribute of most is to link communication skills to the clinical tasks for which they are used (Kalamazoo Consensus Statement, 2001). We selected the Calgary-Cambridge approach because it is evidence-based, well-explicated, and extensive resources for curriculum plan- ning are available (Kurtz, Silverman, & Draper, 2005; Silver- man, Kurtz, & Draper, 2005). We then adopted its three key principles of curriculum design. First, that communication learning ought to occur in a whole curriculum, not as an iso- lated module, and second, that communication learning ought to be programmed vertically so that learners have recurring opportunities to revisit and extend their learning of core skills (Kurtz, Silverman, & Draper, 2005: pp. 213-231). Finally, the Calgary-Cambridge approach addresses communication skills and clinical tasks by explicitly integrating communication proc- ess and clinical content (Kurtz, Silverman, Benson, & Draper, 2003), which met our goal to integrate the students’ clinical learning with requisite communication skills throughout the curriculum. A recent paper in dentistry, by Haak et al. (2008), described the adaptation of the Calgary-Cambridge Observation Guides to design and implement a dental communication mod- ule (Kurtz & Silverman in Haak et al., 2008). Using a random- ised controlled trial pre- and post-test design, the researchers showed that the intervention group exhibited better patient in- terview skills than the control group when both were rated by  V. J. SKINNER ET AL. trained observers. Although the Calgary-Cambridge communi- cation framework has medical education origins, Haak and co-authors (2008) noted its applicability to dentistry due to its inclusion of the patient examination, which is an integral part of all dental encounters. The teaching/learning approaches in the new curriculum in- cluded sessions in Year 2 with simulated patients using forma- tive verbal feedback, video of student performance, and check- lists. Teaching and learning methods for communication skills training can include didactic teaching, observation, role-mod- elling, practice with simulated patients, and video-taped prac- tice with simulated and/or real patients (Carey, Madill, & Manogue, 2010; Maguire & Pitceathly 2002; Rider & Keefer, 2006). However, communication skills learning is best sup- ported by methods requiring active involvement and immediate feedback (Maguire & Pitceathly 2002; Rider & Keefer, 2006), and by assessment methods that are aligned with the intended objectives of the teaching and learning program (Cegala & Broz, 2002). The use of simulated patients is highly recom- mended for undergraduate learning (Croft et al., 2005; Hannah, Millichamp, & Ayer, 2004; Rider & Keefer, 2006) and assess- ment using patient feedback and dentally-relevant checklists is also advocated (Carey, Madill, & Manogue, 2010; Theaker, Kay, & Gill, 2000). Simulated patients used in an English- speaking educational setting are also useful for supporting spe- cific target groups, such as students from diverse backgrounds or students whose primary language is not English (Chur-Hansen & Burg, 2006). The communication curriculum also had to fit the needs of our students and the patients they care for. As noted previously, the communication curriculum was to be embedded throughout the program to match students’ developing needs as they pro- gressed through their degree, and material was to recur verti- cally in different and more demanding contexts to allow stu- dents to consolidate their skills (Kurtz, Silverman, & Draper, 2005: pp. 216-219). In the five-year Adelaide BDS program, students begin clinic experience and provide patient care from Year 1 (refer Table 1). After commencing clinic experience in the second week of their first year of dentistry, students initially provide simple preventive care for each other. In their second year, students progress to providing preventive care for family and friends who elect to attend the student clinic as patients. Then in their third year, students commence caring for patients whom are eligible for publicly funded dental care via the Ade- laide Dental Hospital (ADH), which is part of the South Aus- tralian Dental Service. Year 3, 4 and 5 students, under tutor supervision, provide complete courses of comprehensive care for their patients, some of whom may be in pain or anxious, or who have been on public dental waiting lists for varying peri- ods of time. Therefore, a particular goal of the BDS communication cur- riculum was to complement and augment junior students’ pa- tient care with colleagues, family, and friends to help them prepare for comprehensive hospital patient care in senior year levels. We also aimed to provide a safe setting for junior stu- dents to practise communication in preparation for comprehen- sive patient care. To meet these goals of integrating process and content, and longitudinally embedding and vertically spiralling communication skills into the curriculum, we implemented simulated patient activities in Year 2. The simulated patient activities built on previous clinical communication sessions in Semesters 1 to 3 of the BDS, which had comprised whole class lecture-discussion sessions and application in case-based tuto- rial discussions and in student clinic sessions. The aim of the project described here was to design authentic and relevant, integrated scenarios for use in simulated patient sessions and in teaching videos to support the simulated patient sessions to be implemented with junior students in 2011. The research ques- tions were: 1) What are the communication demands of situations that our student clinicians commonly encounter when treating pa- tients in the dental hospital? 2) What clinical situations are best suited to develop scenar- ios to consolidate and extend students’ learning from Years 1 and 2 to Year 3? 3) Do Year 2 students perceive the scenario-based materials and activities as realistic, relevant, and useful to their develop- ment as clinicians? In the rest of this paper we describe under Methods and Re- sults sections headed “Scenario development” how research questions 1 and 2 were addressed. Under Methods and Results sections headed “Scenario evaluation”, we show how research question 3 was addressed. Methods Scenario Development The scenarios were based on research evidence of communi- cation demands of the clinical situations that BDS students commonly experience during patient encounters in the ADH. Therefore, to address research question 1, a qualitative approach was used. Ethics approval was obtained to gather data through focus groups with recent BDS graduates and semi-structured interviews with clinic tutors. The recent graduates had com- pleted their final examinations two months previously and were at the time working in the ADH as house dentists. Nine house dentists took part in focus group discussions. Each focus group Table 1. Patient care provided by students throughout the Adelaide dental program. Year Semester Clinic patients Care provided 1 - 2 1 - 3 Student colleagues Preventive care of a healthy patien t 2 4 Family & friends Preventive care of patients with early oral health problems 3 5 - 6 ADHa. patien ts Comprehensive simple cour se of care e.g., restorative and periodontal care 4/5 7 - 10 ADH patients Comprehensive, complex course of car e e.g., complex general restorative and peri odontics, fixed and removable prosthodontics, endodon t ics; medically compromised patients N ote: a.ADH: Adelaide Dental Hospital (patients are eligible for publicly funded dental services via the South Australian Dental Service). Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 891  V. J. SKINNER ET AL. took 30 - 45 minutes and was audio-recorded. The clinic tutors were involved in supervising patient care provided by Year 3 - 5 BDS students in the ADH. Sixteen clinic tutors participated. Each interview took 20 - 30 minutes and was audio-recorded. The core question for the focus groups and interviews was: What situations do students commonly encounter in clinics that have presented a communication challenge for them? (i.e. re- search questions 1 and 2). Participants were asked to describe the features of the situations, such as precipitating factors, pa- tient behaviours, and how these situations made the students feel. The data analysis had two objectives: to list and group the situations in order to identify a set of core types of encounters; and to describe some key features of these types of situations that could be used for scripting scenarios. Scenario Evaluation To address research question 3, a survey was used. Partici- pants were Year 2 students in the 2011 cohort. Ethics approval and students’ consent were obtained to match students’ survey responses to the formative assessment data that were also col- lected during the activities (to provide immediate feedback the simulated patients, the tutors and the students all completed checklists about each encounter; students were also given a digital video file of their interaction with the simulated patient). In a class of 79 students, 67 consented to the data-matching (85% response rate). The results of the consenting students’ survey evaluations relating to students’ perceptions of realism, relevance, usefulness, and impact are reported here. The students completed a survey about the clinical commu- nication activities after they had taken part in all the clinical communication activities using the scenarios (in videos or simulated patient role-plays). The survey comprised 15 ques- tions: 13 Likert-scale response items and two open-ended ques- tions. The scale items, which were rated using a 1 to 5 scale, where 1 was “strongly agree” and 5 was “strongly disagree”, addressed elements of program organisation, students’ percep- tions of the scenarios/videos, and students’ perceptions of the impact of the program. The open-ended questions asked stu- dents what aspects of the materials and activities had been most useful for their learning, and what would improve the materials and activities. Results Scenario Development The focus group and interview data presented a range of situations that commonly arose in student clinics and details about the communication demands associated with them. These situations represented differing levels of complexity (from a clinical and a communication perspective) and from them we selected three core situations, which are described in detail below, from which to design the scenarios. To address research question 2, the criteria for selection were that the situation was most likely to be encountered in Year 3, the situation was ap- propriate to introduce in Semester 4 in Year 2, and the range of situations and scenarios would provide comprehensive experi- ence to help Year 2 students prepare for Year 3. These scenar- ios provided the basis for the video scripts and the simulated patient role-play guidelines. The other, more complex situations were reserved for development into scenarios for Year 3 stu- dents. The core situations selected for Year 2 included interact- ing with: 1) a friendly or talkative patient, because this has potential to distract the student from his or her clinical task or 2) an anxious patient, because this is quite common in dentistry, or 3) an annoyed or complaining patient, because this can per- manently damage the dentist-patient relationship. The Year 2 scenarios were based on these core situations and enriched by adding detail from the data about specific aspects of patient dialogue and behaviour. For example, the recent graduates had described how patients who were anxious behaved and inter- acted in a number of different ways. Among these, some pa- tients were quite frank about their dental anxiety and welcomed the opportunity to talk about it with their student clinician, while others attempted to mask their anxiety with humour or bravado. The next step in scenario development was to integrate proc- ess and content according to the Calgary-Cambridge approach (Silverman, Kurtz, & Draper, 2005). For each clinical situation, the aim was to identify clearly the clinical goal, then what clinical content knowledge and skills were required to achieve that goal, and what communication skills would support the accomplishment of the goal. The title of each scenario reflected the overall clinical goal, which was chosen to incorporate both the patient’s and the student’s needs in each type of situation; within the overarching goal we embedded specific clinical skills. The data-based scenarios were titled: “Balancing needs”; “Building confidence”; and “Defusing situations”. “Balancing needs” focuses on student-patient interaction during history-taking with a patient who is very friendly or talkative. It refers to the twin clinical goals of the situation, which are relationship-building via conversation, and focused information-gathering via the history questions. The demand on the novice student is to effectively balance the need of the pa- tient for conversation with their own need as clinician to obtain information in an efficient and timely manner. “Building con- fidence” refers to the essential requirement for the student to be calm and confident when interacting with a patient who is anx- ious, in order to support the patient to be calm and have confi- dence in their student clinician so that treatment can commence. “Defusing situations” addresses the need for the student to have skill at managing their own thoughts and feelings in order to interact effectively with a patient who directs their displeasure at the student clinician. This is also to enable care to proceed. Table 2 summarises the title or core goal of each scenario, and the roles of the student and the patient in each. Table 3 illus- trates the process and content skills embedded in each scenario. Table 4 shows how the materials and activities were used in student activities. Scenario Evaluation A large majority of students gave positive ratings to all items relating to the authenticity, usefulness, and relevance of the pro- gram and scenarios. Responses to items included: “The videos used in class seminars were realistic” 3.8 ± 0.8; “The videos used in class seminars helped my learning” 3.8 ± 0.7; “The simulated patient scenarios were relevant” 4.0 ± 0.5; “The simulated patient program is relevant to my future experience in clinic as a dentist” 4.1 ± 0.7. Figure 1 shows the number of students per rating point for each of these i tems. The majority of students also positively rated the impact of the program on their ability and confidence for clinical communication with patients. This was addressed by items “My ability to communicate effec- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 892  V. J. SKINNER ET AL. Table 2. Summary of the title/core goal and the patient and student roles in each of the three scenarios. Title/goal Summary Simulated patient role Student role Balancing ne eds Medical h is t ory with a patient who is talkative & friendly Talkative, as ks questio ns, e .g. “Why are y ou as king m e that?” “Do you enjoy ...?” Maintaining rapport and staying on track Building confidence An interview with a patient who is anxious Openly anxious OR masks anxiety with humour/bravado or delaying tactics Maintaining rapport & being confident Defusing situations Discussing treatment plans with a patient who is annoyed Complai ns about waiting or the proposed treatment plan e.g. “Why can’t you do all my filling s today?” Maintaining rapport & being calm Table 3. Summary of the process and content s k i lls embedded in each of the three scenarios. Title/goal Process skills Clinical content Balancing needs Patient-centred approach e.g. provid ing cont ext for the questions, giving clear e xpl anat ions Medical history for dentis try knowledge: what questions ar e asked, what follow-up questions are required Building confidence Re lationship-building e.g. acceptance, empathy Applying knowledge of dental anxiety; patient managem ent techniques Defusing situations Relationship-building e.g. acknowledging, conflict management Providing appropriate explana t io ns o f clinical plans Table 4. Student activities using the scenar i o- b a s e d v i de o s a n d s imulated patient sessions: outl i n e p r o v i d e d t o s t u d e n t s . Session type Session title Session outline Class seminar Introduction/Balancing needs Introduce aims, objectives and outcomes of activities Prepare for session 1: v iew and discuss video example scenarios Tutorial 1 Balancing ne eds A talkative patient: Commencing a Hx and interacting with the patient AND staying on track, obtaining required informa t io n Class seminar Building confidence Whole-class discussion of tutorial 1 Preparation for sessi o n 2: view a n d di s cuss video exam p l e scenari os Tutorial 2 Building confidence An anxious patient: Building o ne’s own and patient’s confidence befor e commencing examina t i on Class seminar Defusin g situations Whole-class discussion o f tutorial 2 Preparatio n for session3: view and discuss video example scenarios Tutorial 3 Defusin g situations A patient with a complaint: Managing self and patient in a potential ly unpleasant situation Figure 1. Students’ ratings of realism, usefulnes s, and relevance. tively with patients has improved after participating in the pro- gram” 3.5 ± 0.8, and “I feel more confident communicating with patients after participating in the program” 3.7 ± 0.8. Figure 2 shows the number of students per rating point for each of these items. The students’ open-ended comments enriched and explained the positive ratings (examples of student’s comments are pro- vided in italics). A large number of comments referred to the Figure 2. Students’ ratings of their ability and confidence. videos used as a basis for class discussions in the seminars. Students said they were useful because they gave various illus- trations of dentist-patient encounters in each type of situation. Students also noted that they could use or adapt these examples for their own use. Watching videos of scenarios and discussion with class af- terward—the videos were scripted so you could have a pre- dictable, common situation, to have the 1st exposure to patient Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 893  V. J. SKINNER ET AL. communication. Watching video examples of good patient communication: can learn good phrases & things to avoid. The majority of positive comments related to various aspects of the simulated patient scenarios and/or role plays with simu- lated patients. Students valued the opportunity to work with new and unfamiliar “patients” in addition to their familiar col- leagues, family and friends. Some students also noted that this was a safe environment for communication practice and learn- ing from errors. Getting to interact with a stranger, a very different feeling to interacting with classmate. We got to work with “patients” that were total strangers, definitely prepares us for further years. Having the opportunity to communicate with real patients without the pressure. Being able to make mistakes AND learn from them. Students also wrote about the scenarios and their application in role plays with simulated patients. The benefit of these was two-fold: raising students’ awareness of situations they may encounter in their future clinic, and providing a chance to prac- tice interacting with patients in these situations. Real life interactions with patient Raised up certain issues that we were not aware of and we could discuss and make sug- gestions of possible ways of managing patient. Practicing communicating answers to patient’s con cern: think of reasons to give patients with regards to treatment and pre- pares us for clinical situations. Situations were realistic and helped me learn practical skills, a good thing to do before seeing real patients. Gives an idea of what one can expect to encounter in clinic terms of patient expectations and reactions. Other positive comments related to the small group format. Students noted that in addition to having their own experience, it was useful to observe and learn from colleagues’ interactions. Several students identified feedback from simulated patients, tutors, and colleagues as useful for learning. There were no negative comments about the scenarios, the videos, or the simu- lated patient interactions. Negative comments referred to the organisational aspects of the sessions, such as altering the tim- ing to complement other learning activities. Discussion Our overall goal was to develop a rationale for and then im- plement clinical communication activities for Year 2 dental students that would form part of a coherent communication curriculum in which process and content integrate within ac- tivities and there are recurring opportunities for students to learn (Kurtz, Silverman, & Draper, 2005). In particular, this project sought to develop authentic, relevant scenarios for this component of the communication curriculum, and which were suitable for Year 2 students in preparation for commencing Year 3. The scenarios were used to produce teaching videos that were the basis of class discussions to prepare students for interacting with simulated patients, and to develop guidelines for the simulated patient activities. To develop scenarios, the focus group and interview data with recent graduates and clinic tutors provided rich information about actual clinical encoun- ters and the communication demands of these situations. An obvious advantage of using data from recent graduates and clinic tutors to develop the videos was to ensure the local rele- vance of the scenarios. However, in addition, it was necessary to develop materials that were suitable for the level of the Year 2 students. While there are high quality learning materials available online about dental communication (e.g. University of Michigan open resources at http://open.umich.edu/education/dent), the clinical content is generally too advanced or too specific for junior dental students in the BDS program. The activities based on the scenarios were intended as part of the vertical spiral or helix structure of the curriculum (Kurtz, Silverman, & Draper, 2005: p. 217), and to be realistic and relevant. The preliminary data from the student evaluation of the scenario-based activities show that students perceived that the activities met this curriculum goal. The majority of students were positive about the authenticity and relevance of the sce- narios used in the videos and the simulated patient role-plays, and considered the activities useful preparation for their future clinic role. These active and experiential methods for learning clinical communication were recommended in a recent review of communication skills teaching and learning methods used in UK and US dental schools (Carey, Madill, & Manogue, 2010). The students in the present study commented about the benefit of practising with strangers compared to familiar “patients”, which suggests that the activities enabled them to revisit and consolidate their skills from previous communication and clinic activities in Year 1 and 2. A positive student endorsement of scenario-based video and simulated patient teaching has been reported by other dental educators. Hannah, Millichamp & Ayers (2004) suggested that students evaluated clinical scenar- ios positively because they provided a “realistic and challeng- ing learning task” (p. 975). Other studies have reported that students rate highly the value and relevance of simulated pa- tient scenarios as preparation for their future clinic experiences (Croft et al., 2005; Gorter & Eijkman, 1997). Comments from students in the present study suggest that a major reason for this is that scenario-based videos provided explicit strategies and language that students could adopt or adapt to practice in the role-pays, and then ultimately, in clinic with patients. The ma- jority of students in this study perceived that their ability to communicate with patients had improved and they felt more confident about interacting with patients. Other dental educa- tion studies have shown that students felt better prepared to communicate with patients after taking part in explicit, experi- ential communication skills sessions (Croft et al., 2005; Hannah, Millichamp, & Ayers, 2004; Gorter & Eijkman, 1997). A limitation of the present report for judging the impact of the activities is that it only contains students’ perceptions. An accepted framework for evaluating the impact of educational interventions in health professions has been adapted from the Kirkpatrick system of hierarchical outcomes (Beckman & Cook, 2007). In this hierarchy there are four ascending levels of evi- dence of effectiveness: 1) reaction (satisfaction); 2) learning (attitudes, skills, knowledge); 3) behaviour (impact on clinical practice); and 4) results (impact on patients). The student sur- vey addresses the reaction and students’ perceptions of learning. To adequately understand the impact of the activities, further information about the actual learning outcomes and students’ behaviour in clinic with patients is required. We have data on learning, to be analysed, which includes students’ written self-evaluations and the written feedback from the simulated patients and tutors. We also have written responses to examina- tion questions that address the first two levels on Miller’s (1990) Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 894  V. J. SKINNER ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 895 four-level schematic (“knows”, “knows how”, “shows”, “does”) for assessing clinical skills or competence: the level of knows (knowledge of communication skills) and knows how (compe- tence of how to apply communication skills). To be developed are ways of linking the activities to the outcomes of students’ communication with patients in clinic and any resulting patient oral health improvements, i.e. Kirkpatrick’s levels three and four (Beckman & Cook, 2007), and ways of assessing these at the level of what Miller (1990) called “production”: “shows” and “does”. The materials and activities are being used again in 2012 as part of the communication curriculum, and further data to understand their im pa c t are being collected. Conclusion The Calgary Cambridge approach provided a clear rationale for planning a communication curriculum in dentistry and then for designing activities to suit a particular niche within the cur- riculum. Students considered that simulated patient activities were useful for their learning needs in relation to patient com- munication and the transition from providing care for familiar patients, such as student colleagues, to public hospital patients who were generally strangers, were implemented. Using sce- narios based on local data, students perceived the scenarios to be authentic, relevant, and useful for their learning and prepara- tion for future clinical experiences. Acknowledgements The authors thank: the students and staff of the School of Dentistry; Ms Karen Squires for administrative assistance; Mr Corey Durward of the University Online Development Team for video production; Mr Cory Dean, BDS Hons student, for conducting focus groups and interviews (supported by a Uni- versity of Adelaide Summary Vacation Research Scholarship). The simulated patient program was developed and implemented with a University of Adelaide Implementation Grant for Teach- ing and Learning Enhancement. REFERENCES Australian Dental Council (ADC) (2010). Professional attributes and competencies of the newly qualified dentist. Melbourne, VIC: Aus- tralian Dental Council ( A D C). Beckman, T., & Cook, D. (2007). Developing scholarly projects in edu- cation: A primer for medical teachers. Medical Teacher, 29, 210-218. doi:10.1080/01421590701291469 Carey, J., Madill, A., & Manogue, M. (2010). Communications skills in dental education: A systematic research review. European Journal of Dental Education, 14, 69-78. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0579.2009.00586.x Cegala, D., & Broz, S. (2002). Physician communication skills training: A review of theoretical backgrounds, objectives and skills. Medical Education, 36, 1004-1016. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01331.x Chur-Hansen, A., & Burg, F. (2006). Working with standardised pa- tients for teaching and learning. The Clinical Teacher, 3, 220-224. doi:10.1111/j.1743-498X.2006.00128.x Croft, P., White, A., Wiskin, C., & Allan, T. (2005). Evaluation by dental students of a communication skills course using professional role- players in a UK school of dentistry. European Journal of Dental Education, 9, 2-9. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0579.2004.00349.x General Dental Council (GDC) (2012). Preparing for practice: Dental learning outcomes for registration. London: General Dental Council (GDC). URL (last checked 30 August 2012). http://www.gdc-uk.org Gorter, R., & Eijkman, A. (1997). Communication skills training courses in dental education. European Journal of Dental Education, 1, 143- 147. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0579.1997.tb00025.x Hannah, A., Millichamp, C., & Ayers, K., (2004). A communication skills course for undergraduate dental students. Journal of Dental Education, 68, 970-977. Kalamazoo Consensus Statement (2001). Essential elements of com- munication in medical encounters: The Kalamazoo Consensus State- ment. Academic Medicine, 76, 390-393. Kurtz, S., Silverman, J., Benson, J., & Draper, J. (2003). Marrying content and process in clinical method teaching: Enhancing the Cal- gary-Cambridge guides. Academic Medicine, 78, 802-809. doi:10.1097/00001888-200308000-00011 Kurtz, S., Silverman, J., & Draper, J. (2005). Teaching and learning communication skills in medicine (2nd ed.). Oxford: Radcliffe Pub- lishing. Little, P., Everitt, H., Williamson, I., Warner, G., Moore, M., Gould, C. et al. (2001). Observational study of effect of patient-centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. Brit - is h Medical Journal, 323, 908-911. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7318.908 Miller, G. (1990). The assessment of clinical skills/competence/per- formance. Academic Medicine, 6 5, S63-S67. Rider, E., & Keefer, C. (2006). Communications skills competencies: Definitions and a teaching toolbox. Medical Education, 40, 624-629. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02500.x Sanz, M., Treasure, E., Van Dijk, W., Feldman, C., Groeneveld, H., Kellett, M. et al. (2008). Profile of the dentist in the oral healthcare team in countries with developed economies. European Journal of Dental Education, 12, 101-110. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0579.2007.00492.x Silverman, J., Kurtz, S., & Draper, J. (2005). Skills for communicating with patients (2nd ed.) . Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing. Theaker, E., Kay, E., & Gill, S. (2000). Development and preliminary evaluation of an instrument designed to assess dental students’ com- munication skills. British Dent al Jo ur na l , 18 8 , 40-44.

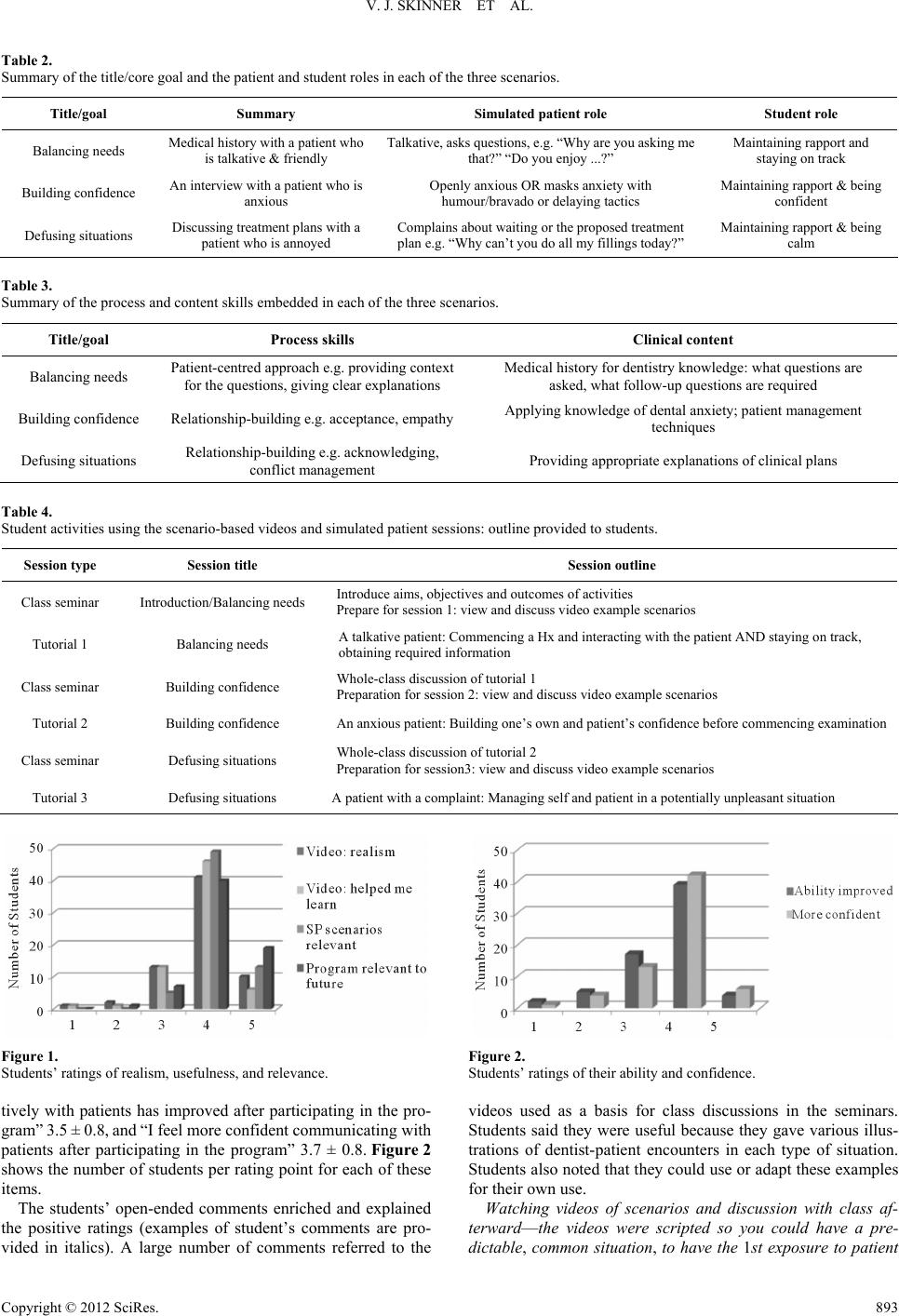

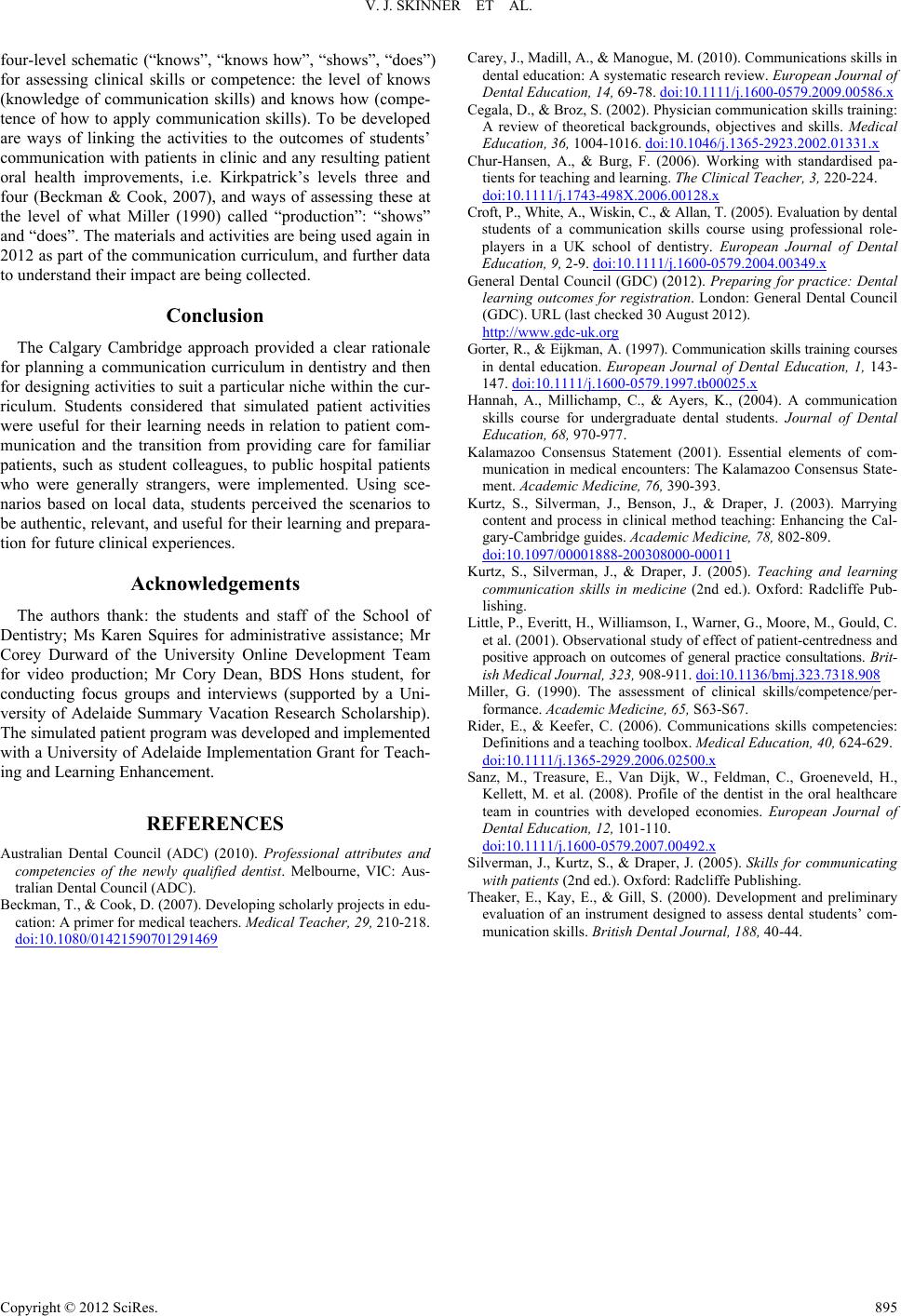

|