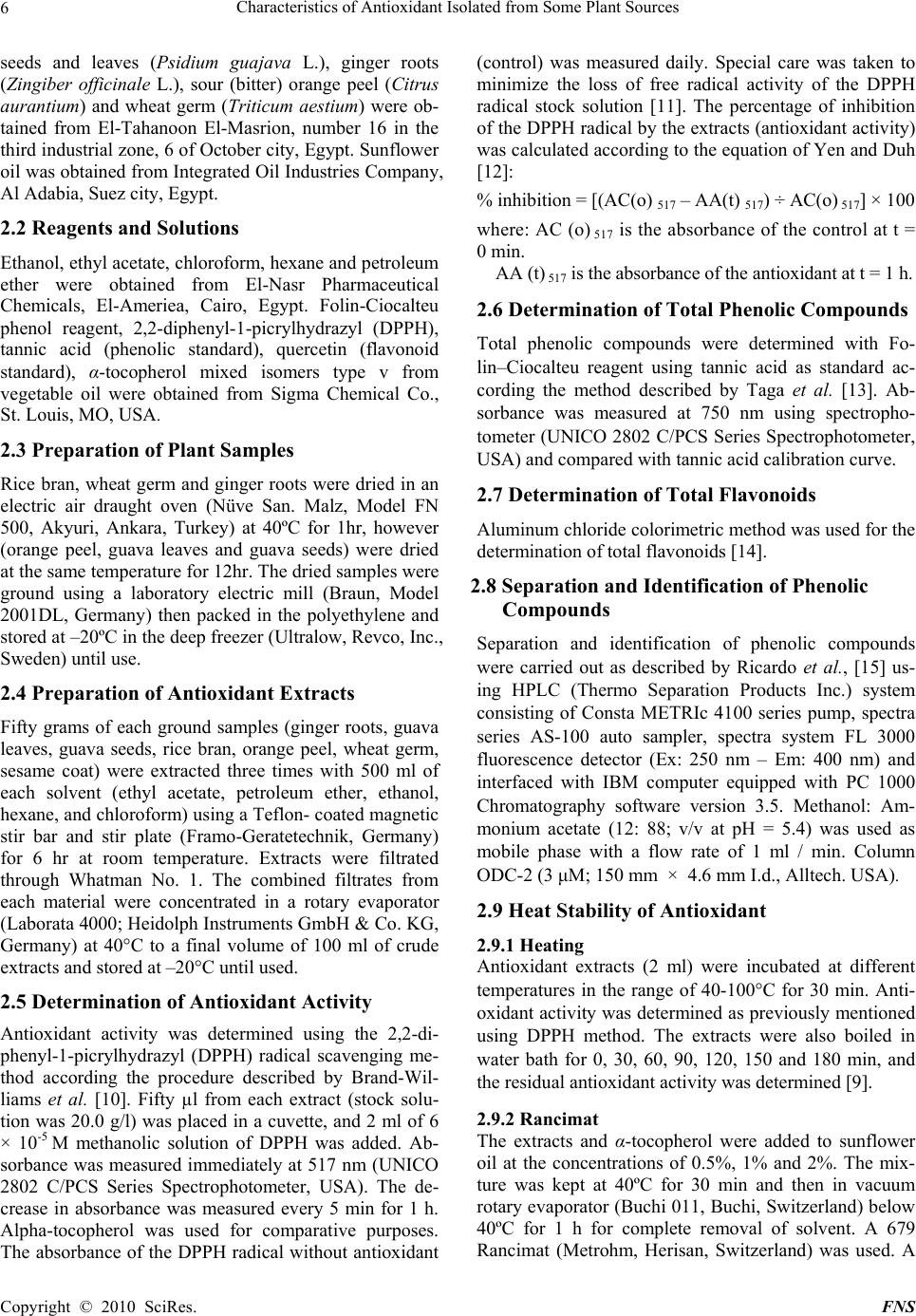

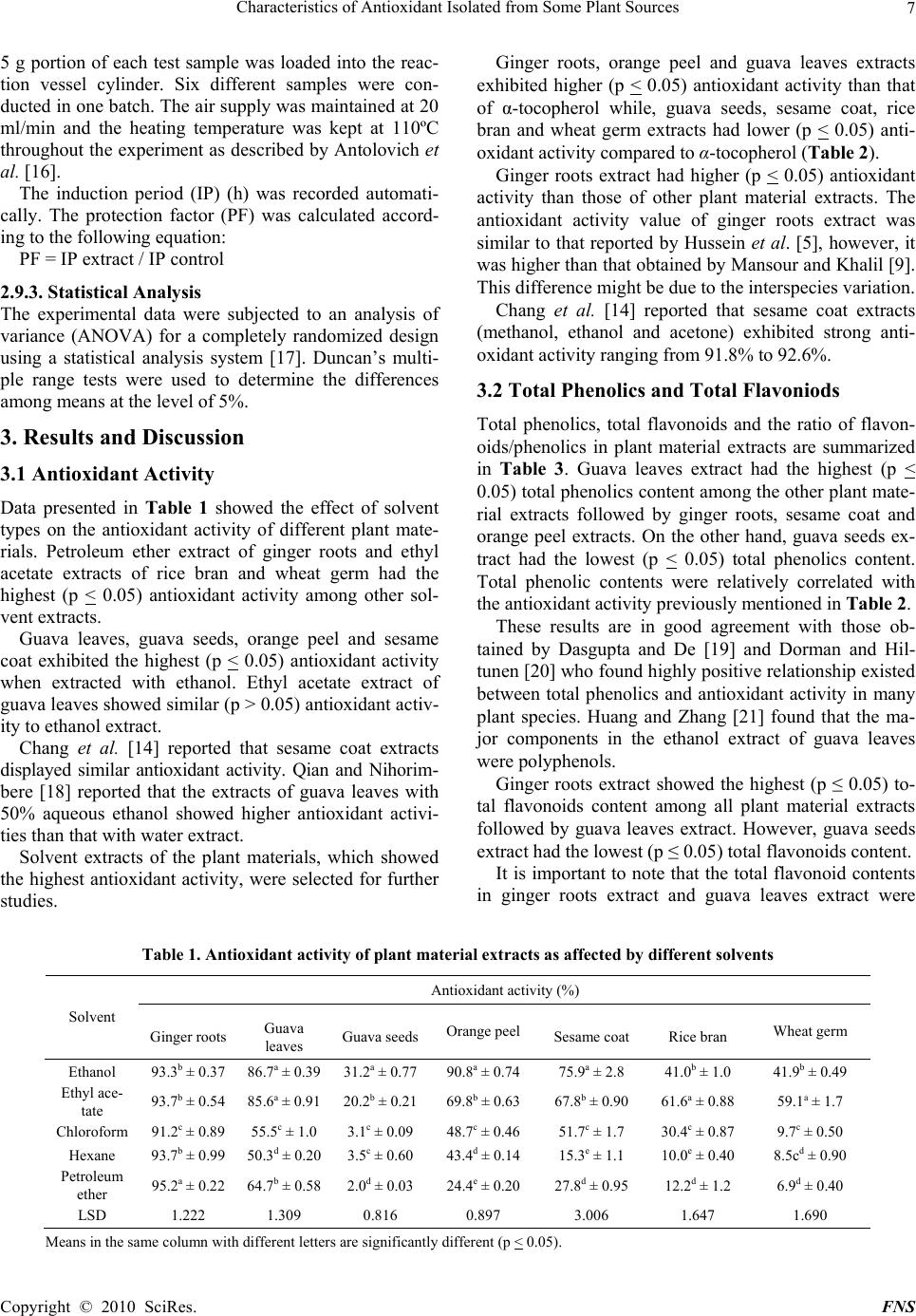

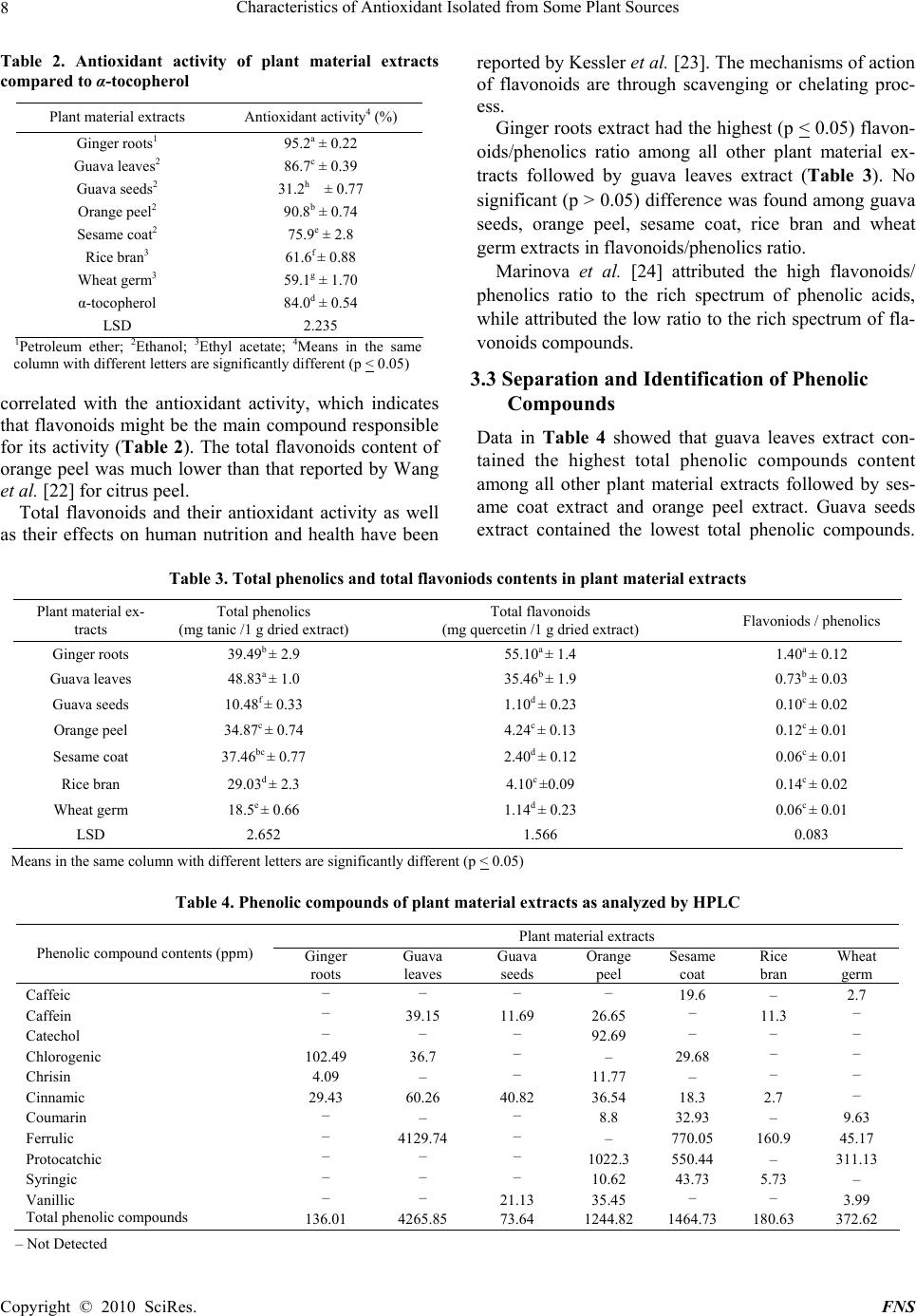

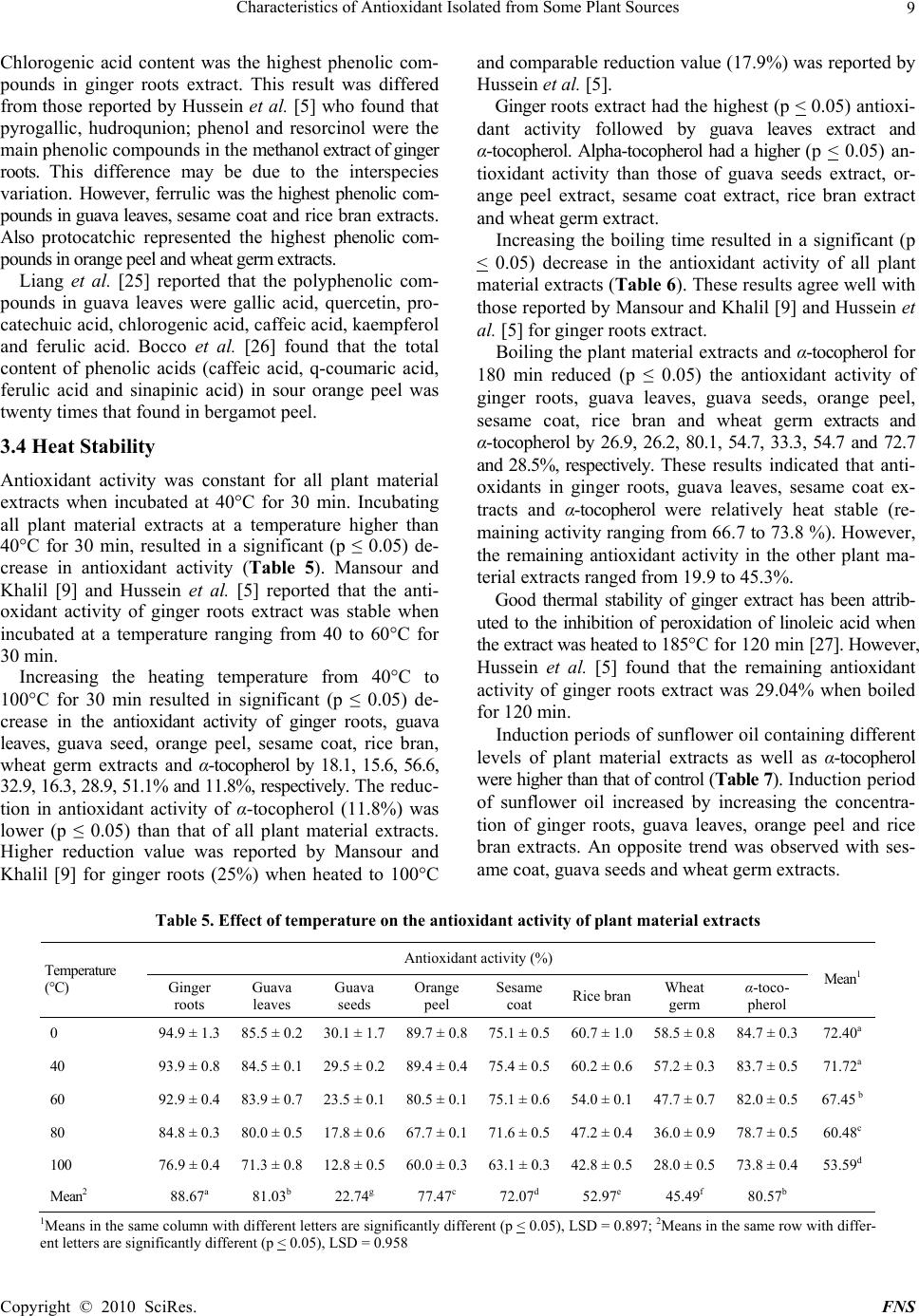

Food and Nutrition Sciences, 2010, 1, 5-12 doi:10.4236/fns.2010.11002 Published Online July 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/fns) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. FNS 5 Characteristics of Antioxidant Isolated from Some Plant Sources A. A. El Bedawey, E. H. Mansour, M. S. Zaky, Amal A. Hassan Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Agriculture, Menufiya University, Shibin El-Kom, Egypt. Email: mansouresam@hotmail.com, a_a_a76@yahoo.com Received April 23rd, 2010; revised May 24th, 2010; accepted May 27th, 2010. ABSTRACT Antioxidant characteristics of ginger roots, guava leaves, guava seeds, orange peel, sesame coat, rice bran and wheat germ as affected by ethanol, ethyl acetate, chloroform, hexane and petroleum ether were evaluated. Petroleum ether extract of ginger roots, ethanol extracts of guava leaves, guava seeds, orange peel and sesame coat and ethyl acetate extracts of rice bran and wheat germ appeared to possess higher antioxidant activity than those from other solvents. Ginger roots, orange peel and guava leaves exhibited higher antioxidant activity than that of α-tocopherol, while guava seeds, sesame coat, rice bran and wheat germ had lower antioxidant activity than that of α-tocopherol. Guava leaves extract had the highest total phenolics content among the other plant material extracts followed by ginger roots, sesame coat and orange peel extracts. However, total flavonoids content was the highest in ginger roots extract followed by guava leaves extract. Ferulic was the highest phenolic compounds in guava leaves and sesame coat extracts. However, chlorogenic acid was the highest phenolic compounds in ginger roots extract. Antioxidants in ginger roots, guava leaves and sesame coat extracts as well as α-tocopherol were heat stable with 73.1, 73.8, 66.7 and 71.6% activity, respectively, after heating at 100°C for 180 min. Induction periods of sunflower oil containing 2% guava leaves and 2% ginger roots extracts were increased by 230.6% and 226.7%, respectively. However, induction period of sunflower oil containing sesame coat was increased by 174.1%, at 0.5% concentration. Similar increment was found for the protection factor. Ginger roots, guava leaves and sesame coat might be promising sources of natural antioxidant to be used in food prod- ucts. Keywords: Antioxidative Activity, Ginger Roots, Guava Leaves, Sesame Coat, Rancimat 1. Introduction The shelf–life of foods is often limited as their stability is restricted due to reactions such as oxidative degradation of lipids. Oxidation of lipids not only produces rancid odours and flavours, but also can decrease the nutritional quality and safety by the formation of secondary prod- ucts in food after cooking and processing [1-3]. Antioxi- dants are used as food additives in order to prevent the oxidative deterioration of fats and oils in processed food. Addition of synthetic antioxidants such as butylated hy- droxyanisole (BHA), butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and tertiary butylhydroquinone (TBHQ) can control lipid oxidation in foods [4,5]. Since some of synthetic anti- oxidants had toxigenic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic ef- fects and some natural antioxidants were effective in enhancing the shelf life of food but less effective than synthetic antioxidants, there is a great demand for the use of new natural antioxidants in food [5,6]. Therefore, there is a strong need for effective antioxidants from natural sources to prevent deterioration of foods. Some components of extracts isolated from oil seeds, spices, fruits and vegetables have been proven in model systems to be as effective antioxidants as synthetic antioxidants [5,7-9]. The present study was conducted to utilize some plant materials such as ginger roots, guava leaves, guava seeds, orange peel, rice bran and wheat germ as natural sources of antioxidants. 2. Materials and Methods 2.1 Materials Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) coat was obtained from El Rashidi El Mizan Company, 6 of October city, second industrial zone, Egypt. Rice bran (Oryza sativa), guava  Characteristics of Antioxidant Isolated from Some Plant Sources 6 seeds and leaves (Psidium guajava L.), ginger roots (Zingiber officinale L.), sour (bitter) orange peel (Citrus aurantium) and wheat germ (Triticum aestium) were ob- tained from El-Tahanoon El-Masrion, number 16 in the third industrial zone, 6 of October city, Egypt. Sunflower oil was obtained from Integrated Oil Industries Company, Al Adabia, Suez city, Egypt. 2.2 Reagents and Solutions Ethanol, ethyl acetate, chloroform, hexane and petroleum ether were obtained from El-Nasr Pharmaceutical Chemicals, El-Ameriea, Cairo, Egypt. Folin-Ciocalteu phenol reagent, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), tannic acid (phenolic standard), quercetin (flavonoid standard), α-tocopherol mixed isomers type v from vegetable oil were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA. 2.3 Preparation of Plant Samples Rice bran, wheat germ and ginger roots were dried in an electric air draught oven (Nüve San. Malz, Model FN 500, Akyuri, Ankara, Turkey) at 40ºC for 1hr, however (orange peel, guava leaves and guava seeds) were dried at the same temperature for 12hr. The dried samples were ground using a laboratory electric mill (Braun, Model 2001DL, Germany) then packed in the polyethylene and stored at –20ºC in the deep freezer (Ultralow, Revco, Inc., Sweden) until use. 2.4 Preparation of Antioxidant Extracts Fifty grams of each ground samples (ginger roots, guava leaves, guava seeds, rice bran, orange peel, wheat germ, sesame coat) were extracted three times with 500 ml of each solvent (ethyl acetate, petroleum ether, ethanol, hexane, and chloroform) using a Teflon- coated magnetic stir bar and stir plate (Framo-Geratetechnik, Germany) for 6 hr at room temperature. Extracts were filtrated through Whatman No. 1. The combined filtrates from each material were concentrated in a rotary evaporator (Laborata 4000; Heidolph Instruments GmbH & Co. KG, Germany) at 40°C to a final volume of 100 ml of crude extracts and stored at –20°C until used. 2.5 Determination of Antioxidant Activity Antioxidant activity was determined using the 2,2-di- phenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging me- thod according the procedure described by Brand-Wil- liams et al. [10]. Fifty µl from each extract (stock solu- tion was 20.0 g/l) was placed in a cuvette, and 2 ml of 6 × 10-5 M methanolic solution of DPPH was added. Ab- sorbance was measured immediately at 517 nm (UNICO 2802 C/PCS Series Spectrophotometer, USA). The de- crease in absorbance was measured every 5 min for 1 h. Alpha-tocopherol was used for comparative purposes. The absorbance of the DPPH radical without antioxidant (control) was measured daily. Special care was taken to minimize the loss of free radical activity of the DPPH radical stock solution [11]. The percentage of inhibition of the DPPH radical by the extracts (antioxidant activity) was calculated according to the equation of Yen and Duh [12]: % inhibition = [(AC(o) 517 – AA(t) 517) ÷ AC(o) 517] × 100 where: AC (o) 517 is the absorbance of the control at t = 0 min. AA (t) 517 is the absorbance of the antioxidant at t = 1 h. 2.6 Determination of Total Phenolic Compounds Total phenolic compounds were determined with Fo- lin–Ciocalteu reagent using tannic acid as standard ac- cording the method described by Taga et al. [13]. Ab- sorbance was measured at 750 nm using spectropho- tometer (UNICO 2802 C/PCS Series Spectrophotometer, USA) and compared with tannic acid calibration curve. 2.7 Determination of Total Flavonoids Aluminum chloride colorimetric method was used for the determination of total flavonoids [14]. 2.8 Separation and Identification of Phenolic Compounds Separation and identification of phenolic compounds were carried out as described by Ricardo et al., [15] us- ing HPLC (Thermo Separation Products Inc.) system consisting of Consta METRIc 4100 series pump, spectra series AS-100 auto sampler, spectra system FL 3000 fluorescence detector (Ex: 250 nm – Em: 400 nm) and interfaced with IBM computer equipped with PC 1000 Chromatography software version 3.5. Methanol: Am- monium acetate (12: 88; v/v at pH = 5.4) was used as mobile phase with a flow rate of 1 ml / min. Column ODC-2 (3 μM; 150 mm × 4.6 mm I.d., Alltech. USA). 2.9 Heat Stability of Antioxidant 2.9.1 Heating Antioxidant extracts (2 ml) were incubated at different temperatures in the range of 40-100°C for 30 min. Anti- oxidant activity was determined as previously mentioned using DPPH method. The extracts were also boiled in water bath for 0, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150 and 180 min, and the residual antioxidant activity was determined [9]. 2.9.2 Rancimat The extracts and α-tocopherol were added to sunflower oil at the concentrations of 0.5%, 1% and 2%. The mix- ture was kept at 40ºC for 30 min and then in vacuum rotary evaporator (Buchi 011, Buchi, Switzerland) below 40ºC for 1 h for complete removal of solvent. A 679 Rancimat (Metrohm, Herisan, Switzerland) was used. A Copyright © 2010 SciRes. FNS  Characteristics of Antioxidant Isolated from Some Plant Sources Copyright © 2010 SciRes. FNS 7 5 g portion of each test sample was loaded into the reac- tion vessel cylinder. Six different samples were con- ducted in one batch. The air supply was maintained at 20 ml/min and the heating temperature was kept at 110ºC throughout the experiment as described by Antolovich et al. [16]. The induction period (IP) (h) was recorded automati- cally. The protection factor (PF) was calculated accord- ing to the following equation: PF = IP extract / IP control 2.9.3. Statistical Analysis The experimental data were subjected to an analysis of variance (ANOVA) for a completely randomized design using a statistical analysis system [17]. Duncan’s multi- ple range tests were used to determine the differences among means at the level of 5%. 3. Results and Discussion 3.1 Antioxidant Activity Data presented in Table 1 showed the effect of solvent types on the antioxidant activity of different plant mate- rials. Petroleum ether extract of ginger roots and ethyl acetate extracts of rice bran and wheat germ had the highest (p < 0.05) antioxidant activity among other sol- vent extracts. Guava leaves, guava seeds, orange peel and sesame coat exhibited the highest (p < 0.05) antioxidant activity when extracted with ethanol. Ethyl acetate extract of guava leaves showed similar (p > 0.05) antioxidant activ- ity to ethanol extract. Chang et al. [14] reported that sesame coat extracts displayed similar antioxidant activity. Qian and Nihorim- bere [18] reported that the extracts of guava leaves with 50% aqueous ethanol showed higher antioxidant activi- ties than that with water extract. Solvent extracts of the plant materials, which showed the highest antioxidant activity, were selected for further studies. Ginger roots, orange peel and guava leaves extracts exhibited higher (p < 0.05) antioxidant activity than that of α-tocopherol while, guava seeds, sesame coat, rice bran and wheat germ extracts had lower (p < 0.05) anti- oxidant activity compared to α-tocopherol (Table 2). Ginger roots extract had higher (p < 0.05) antioxidant activity than those of other plant material extracts. The antioxidant activity value of ginger roots extract was similar to that reported by Hussein et al. [5], however, it was higher than that obtained by Mansour and Khalil [9]. This difference might be due to the interspecies variation. Chang et al. [14] reported that sesame coat extracts (methanol, ethanol and acetone) exhibited strong anti- oxidant activity ranging from 91.8% to 92.6%. 3.2 Total Phenolics and Total Flavoniods Total phenolics, total flavonoids and the ratio of flavon- oids/phenolics in plant material extracts are summarized in Table 3. Guava leaves extract had the highest (p < 0.05) total phenolics content among the other plant mate- rial extracts followed by ginger roots, sesame coat and orange peel extracts. On the other hand, guava seeds ex- tract had the lowest (p < 0.05) total phenolics content. Total phenolic contents were relatively correlated with the antioxidant activity previously mentioned in Table 2. These results are in good agreement with those ob- tained by Dasgupta and De [19] and Dorman and Hil- tunen [20] who found highly positive relationship existed between total phenolics and antioxidant activity in many plant species. Huang and Zhang [21] found that the ma- jor components in the ethanol extract of guava leaves were polyphenols. Ginger roots extract showed the highest (p ≤ 0.05) to- tal flavonoids content among all plant material extracts followed by guava leaves extract. However, guava seeds extract had the lowest (p ≤ 0.05) total flavonoids content. It is important to note that the total flavonoid contents in ginger roots extract and guava leaves extract were Table 1. Antioxidant activity of plant material extracts as affected by different solvents Antioxidant activity (%) Solvent Ginger rootsGuava leaves Guava seedsOrange peel Sesame coat Rice bran Wheat germ Ethanol 93.3b ± 0.3786.7a ± 0.39 31.2a ± 0.7790.8a ± 0.74 75.9a ± 2.8 41.0b ± 1.0 41.9b ± 0.49 Ethyl ace- tate 93.7b ± 0.5485.6a ± 0.91 20.2b ± 0.2169.8b ± 0.63 67.8b ± 0.90 61.6a ± 0.88 59.1a ± 1.7 Chloroform 91.2c ± 0.8955.5c ± 1.0 3.1c ± 0.09 48.7c ± 0.46 51.7c ± 1.7 30.4c ± 0.87 9.7c ± 0.50 Hexane 93.7b ± 0.9950.3d ± 0.20 3.5c ± 0.60 43.4d ± 0.14 15.3e ± 1.1 10.0e ± 0.40 8.5cd ± 0.90 Petroleum ether 95.2a ± 0.2264.7b ± 0.58 2.0d ± 0.03 24.4e ± 0.20 27.8d ± 0.95 12.2d ± 1.2 6.9d ± 0.40 LSD 1.222 1.309 0.816 0.897 3.006 1.647 1.690 Means in the same column with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05).  Characteristics of Antioxidant Isolated from Some Plant Sources 8 Table 2. Antioxidant activity of plant material extracts compared to α-tocopherol Plant material extracts Antioxidant activity4 (%) Ginger roots1 95.2a ± 0.22 Guava leaves2 86.7c ± 0.39 Guava seeds2 31.2h ± 0.77 Orange peel2 90.8b ± 0.74 Sesame coat2 75.9e ± 2.8 Rice bran3 61.6f ± 0.88 Wheat germ3 59.1g ± 1.70 α-tocopherol 84.0d ± 0.54 LSD 2.235 1Petroleum ether; 2Ethanol; 3Ethyl acetate; 4Means in the same column with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05) correlated with the antioxidant activity, which indicates that flavonoids might be the main compound responsible for its activity (Table 2). The total flavonoids content of orange peel was much lower than that reported by Wang et al. [22] for citrus peel. Total flavonoids and their antioxidant activity as well as their effects on human nutrition and health have been reported by Kessler et al. [23]. The mechanisms of action of flavonoids are through scavenging or chelating proc- ess. Ginger roots extract had the highest (p < 0.05) flavon- oids/phenolics ratio among all other plant material ex- tracts followed by guava leaves extract (Table 3). No significant (p > 0.05) difference was found among guava seeds, orange peel, sesame coat, rice bran and wheat germ extracts in flavonoids/phenolics ratio. Marinova et al. [24] attributed the high flavonoids/ phenolics ratio to the rich spectrum of phenolic acids, while attributed the low ratio to the rich spectrum of fla- vonoids compounds. 3.3 Separation and Identification of Phenolic Compounds Data in Table 4 showed that guava leaves extract con- tained the highest total phenolic compounds content among all other plant material extracts followed by ses- ame coat extract and orange peel extract. Guava seeds extract contained the lowest total phenolic compounds. Table 3. Total phenolics and total flavoniods contents in plant material extracts Plant material ex- tracts Total phenolics (mg tanic /1 g dried extract) Total flavonoids (mg quercetin /1 g dried extract) Flavoniods / phenolics Ginger roots 39.49b ± 2.9 55.10a ± 1.4 1.40a ± 0.12 Guava leaves 48.83a ± 1.0 35.46b ± 1.9 0.73b ± 0.03 Guava seeds 10.48f ± 0.33 1.10d ± 0.23 0.10c ± 0.02 Orange peel 34.87c ± 0.74 4.24c ± 0.13 0.12c ± 0.01 Sesame coat 37.46bc ± 0.77 2.40d ± 0.12 0.06c ± 0.01 Rice bran 29.03d ± 2.3 4.10c ±0.09 0.14c ± 0.02 Wheat germ 18.5e ± 0.66 1.14d ± 0.23 0.06c ± 0.01 LSD 2.652 1.566 0.083 Means in the same column with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05) Table 4. Phenolic compounds of plant material e x tr ac ts as analyzed by HPLC Plant material extracts Phenolic compound contents (ppm) Ginger roots Guava leaves Guava seeds Orange peel Sesame coat Rice bran Wheat germ Caffeic – – – – 19.6 – 2.7 Caffein – 39.15 11.69 26.65 – 11.3 – Catechol – – – 92.69 – – – Chlorogenic 102.49 36.7 – – 29.68 – – Chrisin 4.09 – – 11.77 – – – Cinnamic 29.43 60.26 40.82 36.54 18.3 2.7 – Coumarin – – – 8.8 32.93 – 9.63 Ferrulic – 4129.74 – – 770.05 160.9 45.17 Protocatchic – – – 1022.3 550.44 – 311.13 Syringic – – – 10.62 43.73 5.73 – Vanillic – – 21.13 35.45 – – 3.99 Total phenolic compounds 136.01 4265.85 73.64 1244.82 1464.73 180.63 372.62 – Not Detected Copyright © 2010 SciRes. FNS  Characteristics of Antioxidant Isolated from Some Plant Sources 9 Chlorogenic acid content was the highest phenolic com- pounds in ginger roots extract. This result was differed from those reported by Hussein et al. [5] who found that pyrogallic, hudroqunion; phenol and resorcinol were the main phenolic compounds in the methanol extract of ginger roots. This difference may be due to the interspecies variation. However, ferrulic was the highest phenolic com- pounds in guava leaves, sesame coat and rice bran extracts. Also protocatchic represented the highest phenolic com- pounds in orange peel and wheat germ extracts. Liang et al. [25] reported that the polyphenolic com- pounds in guava leaves were gallic acid, quercetin, pro- catechuic acid, chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, kaempferol and ferulic acid. Bocco et al. [26] found that the total content of phenolic acids (caffeic acid, q-coumaric acid, ferulic acid and sinapinic acid) in sour orange peel was twenty times that found in bergamot peel. 3.4 Heat Stability Antioxidant activity was constant for all plant material extracts when incubated at 40°C for 30 min. Incubating all plant material extracts at a temperature higher than 40°C for 30 min, resulted in a significant (p ≤ 0.05) de- crease in antioxidant activity (Table 5). Mansour and Khalil [9] and Hussein et al. [5] reported that the anti- oxidant activity of ginger roots extract was stable when incubated at a temperature ranging from 40 to 60°C for 30 min. Increasing the heating temperature from 40°C to 100°C for 30 min resulted in significant (p ≤ 0.05) de- crease in the antioxidant activity of ginger roots, guava leaves, guava seed, orange peel, sesame coat, rice bran, wheat germ extracts and α-tocopherol by 18.1, 15.6, 56.6, 32.9, 16.3, 28.9, 51.1% and 11.8%, respectively. The reduc- tion in antioxidant activity of α-tocopherol (11.8%) was lower (p ≤ 0.05) than that of all plant material extracts. Higher reduction value was reported by Mansour and Khalil [9] for ginger roots (25%) when heated to 100°C and comparable reduction value (17.9%) was reported by Hussein et al. [5]. Ginger roots extract had the highest (p < 0.05) antioxi- dant activity followed by guava leaves extract and α-tocopherol. Alpha-tocopherol had a higher (p < 0.05) an- tioxidant activity than those of guava seeds extract, or- ange peel extract, sesame coat extract, rice bran extract and wheat germ extract. Increasing the boiling time resulted in a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in the antioxidant activity of all plant material extracts (Table 6). These results agree well with those reported by Mansour and Khalil [9] and Hussein et al. [5] for ginger roots extract. Boiling the plant material extracts and α-tocopherol for 180 min reduced (p ≤ 0.05) the antioxidant activity of ginger roots, guava leaves, guava seeds, orange peel, sesame coat, rice bran and wheat germ extracts and α-tocopherol by 26.9, 26.2, 80.1, 54.7, 33.3, 54.7 and 72.7 and 28.5%, respectively. These results indicated that anti- oxidants in ginger roots, guava leaves, sesame coat ex- tracts and α-tocopherol were relatively heat stable (re- maining activity ranging from 66.7 to 73.8 %). However, the remaining antioxidant activity in the other plant ma- terial extracts ranged from 19.9 to 45.3%. Good thermal stability of ginger extract has been attrib- uted to the inhibition of peroxidation of linoleic acid when the extract was heated to 185°C for 120 min [27]. However, Hussein et al. [5] found that the remaining antioxidant activity of ginger roots extract was 29.04% when boiled for 120 min. Induction periods of sunflower oil containing different levels of plant material extracts as well as α-tocopherol were higher than that of control (Table 7). Induction period of sunflower oil increased by increasing the concentra- tion of ginger roots, guava leaves, orange peel and rice bran extracts. An opposite trend was observed with ses- ame coat, guava seeds and wheat germ extracts. Table 5. Effect of temperature on the antioxidant activity of plant material extracts Antioxidant activity (%) Temperature (°C) Ginger roots Guava leaves Guava seeds Orange peel Sesame coat Rice branWheat germ α-toco- pherol Mean1 0 94.9 ± 1.3 85.5 ± 0.2 30.1 ± 1.789.7 ± 0.875.1 ± 0.560.7 ± 1.058.5 ± 0.8 84.7 ± 0.3 72.40a 40 93.9 ± 0.8 84.5 ± 0.1 29.5 ± 0.289.4 ± 0.475.4 ± 0.560.2 ± 0.657.2 ± 0.3 83.7 ± 0.5 71.72a 60 92.9 ± 0.4 83.9 ± 0.7 23.5 ± 0.180.5 ± 0.175.1 ± 0.654.0 ± 0.147.7 ± 0.7 82.0 ± 0.5 67.45 b 80 84.8 ± 0.3 80.0 ± 0.5 17.8 ± 0.667.7 ± 0.171.6 ± 0.547.2 ± 0.436.0 ± 0.9 78.7 ± 0.5 60.48c 100 76.9 ± 0.4 71.3 ± 0.8 12.8 ± 0.560.0 ± 0.363.1 ± 0.342.8 ± 0.528.0 ± 0.5 73.8 ± 0.4 53.59d Mean2 88.67a 81.03b 22.74g 77.47c 72.07d 52.97e 45.49f 80.57b 1Means in the same column with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05), LSD = 0.897; 2Means in the same row with differ- ent letters are significantly different (p < 0.05), LSD = 0.958 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. FNS  Characteristics of Antioxidant Isolated from Some Plant Sources 10 Table 6. Effect of boiling for different time on the antioxidant activity of plant material extracts Antioxidant activity (%) Time (min) Ginger roots Guava leaves Guava Seeds Orange peelSesame coatRice branWheat germ α-tocopherol Mean1 0 94.9 ± 1.3 85.5 ± 0.2 30.1 ± 1.789.7 ± 0.875.1 ± 0.560.7 ± 1.058.5 ± 0.8 84.7 ± 0.3 72.40a 30 76.9 ± 0.4 71.3 ± 0.8 12.8 ± 0.560.0 ± 0.363.1 ± 0.342.8 ± 0.528.0 ± 0.5 73.8 ± 0.4 53.58b 60 73.1 ± 0.6 68.4 ± 0.9 10.0 ± 0.252.5 ± 0.259.7 ± 0.436.9 ± 0.625.0 ± 0.4 68.0 ± 0.5 49.20c 90 72.0 ± 0.4 67.2 ± 0.8 8.8 ± 0.2 47.9 ± 0.157.5 ± 0.134.0 ± 0.921.6 ± 0.1 64.7 ± 0.4 46.71d 120 71.3 ± 0.2 66.0 ± 0.3 7.8 ± 0.3 44.0 ± 0.755.0 ± 0.530.9 ± 0.818.8 ± 0.2 62.5 ± 0.1 44.53e 150 70.0 ± 0.5 64.3 ± 0.6 6.9 ± 0.8 42.0 ± 0.452.2 ± 0.429.4 ± 0.116.9 ± 0.4 61.5 ± 0.1 42.90f 180 69.4 ± 0.1 63.1 ± 0.5 6.0 ± 0.3 40.6 ± 0.450.1 ± 1.527.5 ± 0.416.0 ± 0.5 60.6 ± 0.6 41.66g Mean2 75.36a 69.40b 11.77h 53.82e 58.96d 37.45f 26.41g 67.96c 1Means in the same column with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05), LSD = 0.720; 2Means in the same row with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05), LSD = 0.883 The highest induction period of sunflower oil was ob- tained by the addition of 2% guava leaves extract fol- lowed by the addition of 2% ginger roots extract. How- ever, the addition of guava seeds extract at 2% level showed the lowest induction period. The induction pe- riod of sunflower oil increased by 230.6 and 226.7% by the addition of 2% guava leaves extracts and 2% ginger roots extract respectively. Alpha-tocopherol had a higher induction period (11.86 h) than all plant material extracts at 1% concentration. In- duction period of sunflower oil containing α-tocopherol was increased by 232.5%. On the other hand sesame coat extract had the highest induction period (8.88 h) at 0.5% concentration. Induction period of sunflower oil contain- ing sesame coat was increased by 174.1%. Elleuch et al., [28] found that raw sesame seed oil had a higher induction period (28.2 h) then followed by de- hulled sesame seed oil (25.7 h). Thus, the dehulling processes decrease the stability of the oils. Data in Table 8 showed the protection factor of sun- flower oil containing plant material extracts and α-toco- pherol. All protection factors of plant material extracts had a positive trend similar to the induction period (Ta- ble 7). The highest protection factor of sunflower oil was obtained by the addition of 2% guava leaves extract fol- lowed by ginger roots and orange peel extracts at the same level. Protection factor of sunflower oil containing guava leaves, ginger roots and orange peel extracts was increased by 231, 227 and 164%, respectively. Similar increment was found for the induction period (Table 7). While, guava seeds, rice bran and wheat germ extracts had lower stabilizing effect than that of α-tocopherol. Garau et al., [29] reported that the average protection factor value for orange peel samples was 1.52. Table 7. Induction period (hr) of sunflower oil containing different levels of plant material extracts and α-tocopherol assessed by rancimat at 100C Level of addition (%) Plant material extracts 0 0.5 1 2 Ginger roots 5.1 6.94 8.54 11.56 Guava leaves 5.1 8.46 9.54 11.76 Guava seeds 5.1 6.36 5.14 5.11 Orange peel 5.1 7.95 8.13 8.36 Sesame coat 5.1 8.88 6.87 6.81 Rice bran 5.1 5.26 5.44 5.98 Wheat germ 5.1 6.30 6.04 5.34 α-tocopherol 5.1 10.00 11.86 11.10 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. FNS  Characteristics of Antioxidant Isolated from Some Plant Sources11 Table 8. Protection factor of sunflower oil containing different levels (%) of plant material extracts and α-tocopherol assessed by rancimat at 100C Level of addition (%) Plant material extracts 0 0.5 1 2 Ginger roots 1 1.36 1.67 2.27 Guava leaves 1 1.66 1.87 2.31 Guava seeds 1 1.25 1.01 1.00 Orange peel 1 1.56 1.59 1.64 Sesame coat 1 1.74 1.35 1.34 Rice bran 1 1.03 1.07 1.17 Wheat germ 1 1.24 1.18 1.05 α-tocopherol 1 1.96 2.33 2.18 Alpha-tocopherol (at 1% concentration) had a higher protection factor than all plant material extracts. On the other hand, sesame coat extract (at 0.5% concentration) had the highest protection factor as compared to the other plant material extracts. From the above results, it could be concluded that the antioxidant activities of ginger roots, guava leaves and sesame coat were comparable to α-tocopherol. Ginger roots, guava leaves and sesame coat showed good thermal stability in comparison with α-tocopherol. Ginger roots, guava leaves and sesame coat might be promising sources of natural antioxidant to be used in food prod- ucts. REFERENCES [1] F. Shahidi, “Natural Antioxidants: Chemistry, Health Effects and Applications,” AOCS Press, Champaign, 1996. [2] J. Loliger and H. J. Wille, “Natural Antioxidant,” Oils and Fats International, Vol. 9, 1993, pp. 18-22. [3] E. N. Frankel, “In Search of Better Methods to Evaluate Natural Antioxidants and Oxidative Stability in Food Lip- ids,” Trends in Food Science and Technology, Vol. 4, No. 7, 1993, pp. 220-225. [4] A. H. Khalil and E. H. Mansour, “Control of Lipid Oxi- dation in Cooked and Uncooked Refrigerated Carp Fillets by Antioxidant and Packaging Combinations,” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, Vol. 46, No. 3, 1998, pp. 1158-1162. [5] E. A. Hussein, E. H. Mansour and A. E. Naglaa, “Anti- oxidant Properties of Solvent Extracts from Some Plant Sources,” Annals of Agricultural Sciences, in press, Ain Shams University, Cairo, 2009. [6] B. Nanditha and P. Prabhasankar, “Antioxidants in Bak- ery Products: A Review,” Critical Reviews in Food Sci- ence and Nutrition, Vol. 49, No. 1, 2009, pp. 1-27. [7] U. Krings and R. G. Berger, “Antioxidant Activity of Some Roasted Foods,” Food Chemistry, Vol. 72, No. 2, 2001, pp. 223-229. [8] Y. R. Lu and L. Y. Foo, “Antioxidant Activities of Poly- phenols from Sage (Salvia Officinalis),” Food Chemistry, Vol. 75, No. 2, 2001, pp. 197-202. [9] E. H. Mansour and A. H. Khalil, “Evaluation of Antioxi- dant Activity of Some Plant Extracts and their Applica- tion to Ground Beef Patties,” Food Chemistry, Vol. 69, No. 2, 2000, pp. 135-141. [10] W. Brand-Williams, M. E. Cuvelier and C. Berset, “Use of a Free Radical Method to Evaluate Antioxidant Activ- ity,” Lebensmittel-Wissenschaft und Technologie, Vol. 28, No. 1, 1995, pp. 25-30. [11] M. S. Blois, “Antioxidant Determination by the Use of a Stable Free Radical,” Nature, Vol. 181, No. 4617, 1958, pp. 1199-1200. [12] G. C. Yen and P. D. Duh, “Scavenging Effect of Metha- nolic Extracts of Peanut Hulls on Free-Radical and Ac- tive-Oxygen Species,” Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, Vol. 42, No. 4, 1994, pp. 629-632. [13] M. S. Taga, E. E. Miller and D. E. Pratt, “Chia Seeds as a Source of Natural Lipid Antioxidants,” Journal of Ameri- can Oil Chemists’ Society, Vol. 61, No. 5, 1984, pp. 928- 931. [14] C. Chang, M. Yang, H. Wen and J. Chern, “Estimation of Total Flavonoid Content in Propolis by Two Comple- mentary Colorimetric Methods,” Journal of Food and Drug Analysis, Vol. 10, No. 3, 2002, pp. 178-182. [15] J. M. Ricardo-da-Silva, O. Laureano and M. L. B. da Costa, “Total Phenol and Proanthocyanidin Evaluation of Lu- pinus Spicies,” Proceedings of the 7th International Lu- pin Conference, Evora, 18-23 April 1993, pp. 250-254. [16] M. Antolovich, P. D. Prenzler, E. Patsalides, S. McDon- ald and K. Robards, “Methods for Testing Antioxidant Activity,” The Analyst, Vol. 127, No. 1, 2002, pp. 183-198. [17] SAS Institute, Inc. “SAS User’s Guide. Statistical Analy- sis System,” 2000 Edition, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, 2000. [18] H. Qian and V. Nihorimbere, “Antioxidant Power of Copyright © 2010 SciRes. FNS  Characteristics of Antioxidant Isolated from Some Plant Sources 12 Phytochemicals from Psidium Guajava Leaf,” Journal of Zhejiang University Science, Vol. 5, No. 6, 2004, pp. 676- 683. [19] N. Dasgupta and B. De, “Antioxidant Activity of Piper Betle L. Leaf Extract in Vitro,” Food Chemistry, Vol. 88, No. 2, 2004, pp. 219-224. [20] H. J. D. Dorman and R. Hiltunen, “Fe (III) Reductive and Free Radical-Scavenging Properties of Summer Savory (Satureja Hortensis L.) Extract and Subtractions,” Food Chemistry, Vol. 88, 2004, pp. 193-199. [21] J. Huang and Z. Zhang, “Gas Chromatographic–Mass Spectroscopic Analysis of the Chemical Components in the Ethanol Extract of Guava Leaves,” Journal of Sun Yat-Sen University: Natural Sciences, Vol. 43, No. 6, 2004, pp. 117-120. [22] Y. C. Wang, Y. C. Chuang and H. W. Hsu, “The Flavon- oid, Carotenoid and Pectin Content in Peels of Citrus Cul- tivated in Taiwan,” Food Chemistry, Vol. 106, No. 1, 2008, pp. 277-284. [23] M. Kessler, G. Ubeaud and L. Jung, “Anti- and Pro-Oxi- dant Activity of Rutin and Quercetin Derivatives,” Jour- nal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, Vol. 55, No. 1, 2003, pp. 131-142. [24] D. Marinova, F. Ribarova and M. Atanassova, “Total Phenolics and Total Flavonoids in Bulgarian Fruits and Vegetables,” Journal of the University of Chemistry and Technological Metallurgy, Vol. 40, No. 3, 2005, pp. 255- 260. [25] Q. Liang, H. Quian and W. Yao, “Identification of Fla- vonoids and their Glycosides by High-Performance Liq- uid Chromatography with Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry and with Diode Array Ultraviolet Detec- tion,” European Journal of Mass Spectrometry, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2005, pp. 93-101. [26] A. Bocco, M. E. Cuvelier, H. Richard and C. Berset, “An- tioxidant Activity and Phenolic Composition of Citrus Peel and Seed Extracts,” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, Vol. 46, No. 6, 1998, pp. 2123-2129. [27] Z. U. Rehman, A. M. Salariya and F. Habib, “Antioxidant Activity of Ginger Extract in Sunflower Oil,” Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, Vol. 83, No. 7, 2003, pp. 624-629. [28] M. A. Elleuch, S. A. Besbes, O. B. Roiseux, C. B. Blecker and A. A. H. Attia, “Quality Characteristics of Sesame Seeds and by-Products,” Food Chemistry, Vol. 103, 2007, pp. 641-650. [29] M. C. Garau, S. Simal, C. Rosselló and A. Femenia, “Ef- fect of Air-Drying Temperature on Physico-Chemical Properties of Dietary Fibre and Antioxidant Capacity of Orange (Citrus aurantium v. Canoneta) by-Products,” Food Chemistry, Vol. 104, No. 3, 2007, pp. 1014-1024. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. FNS

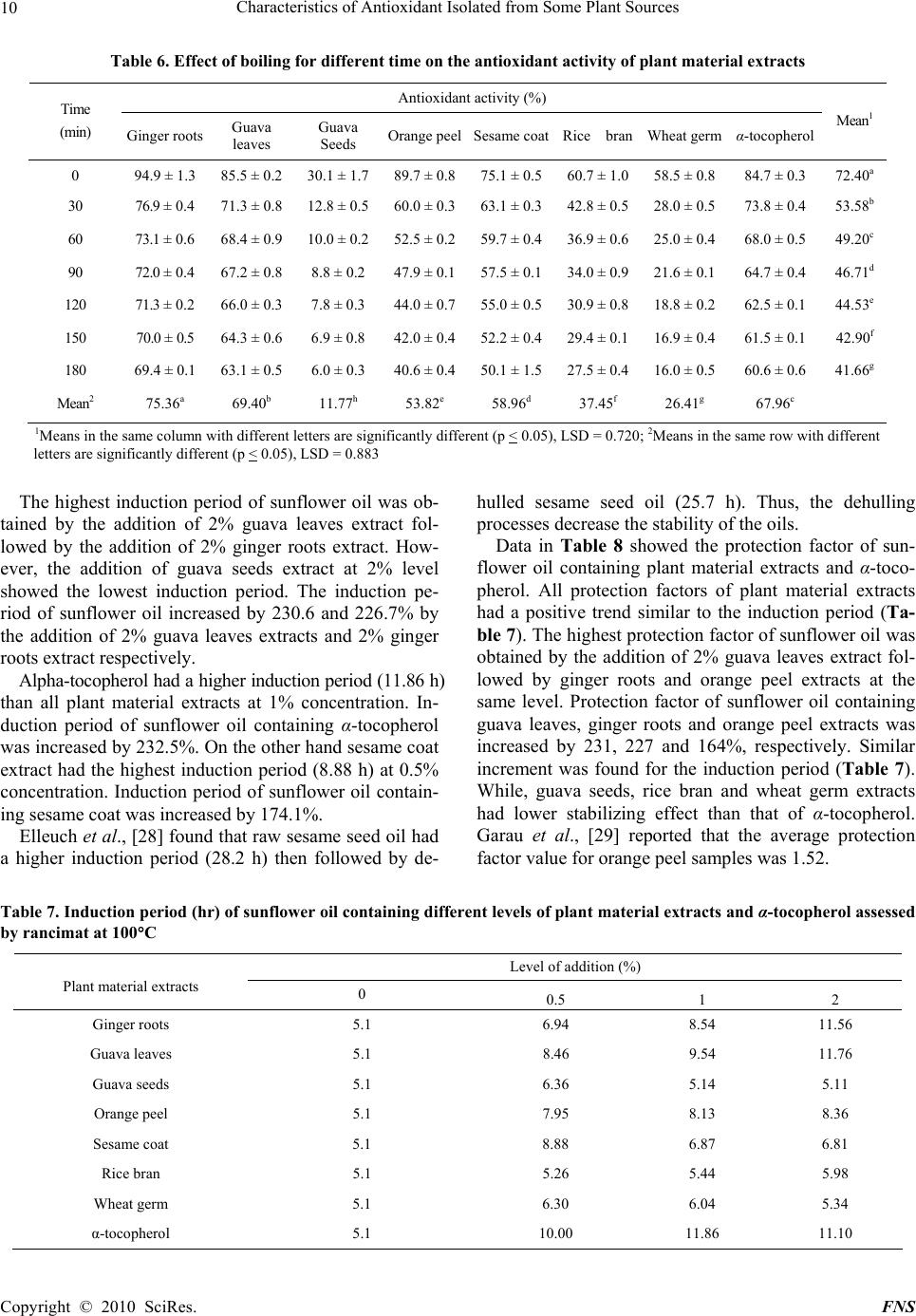

|