Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

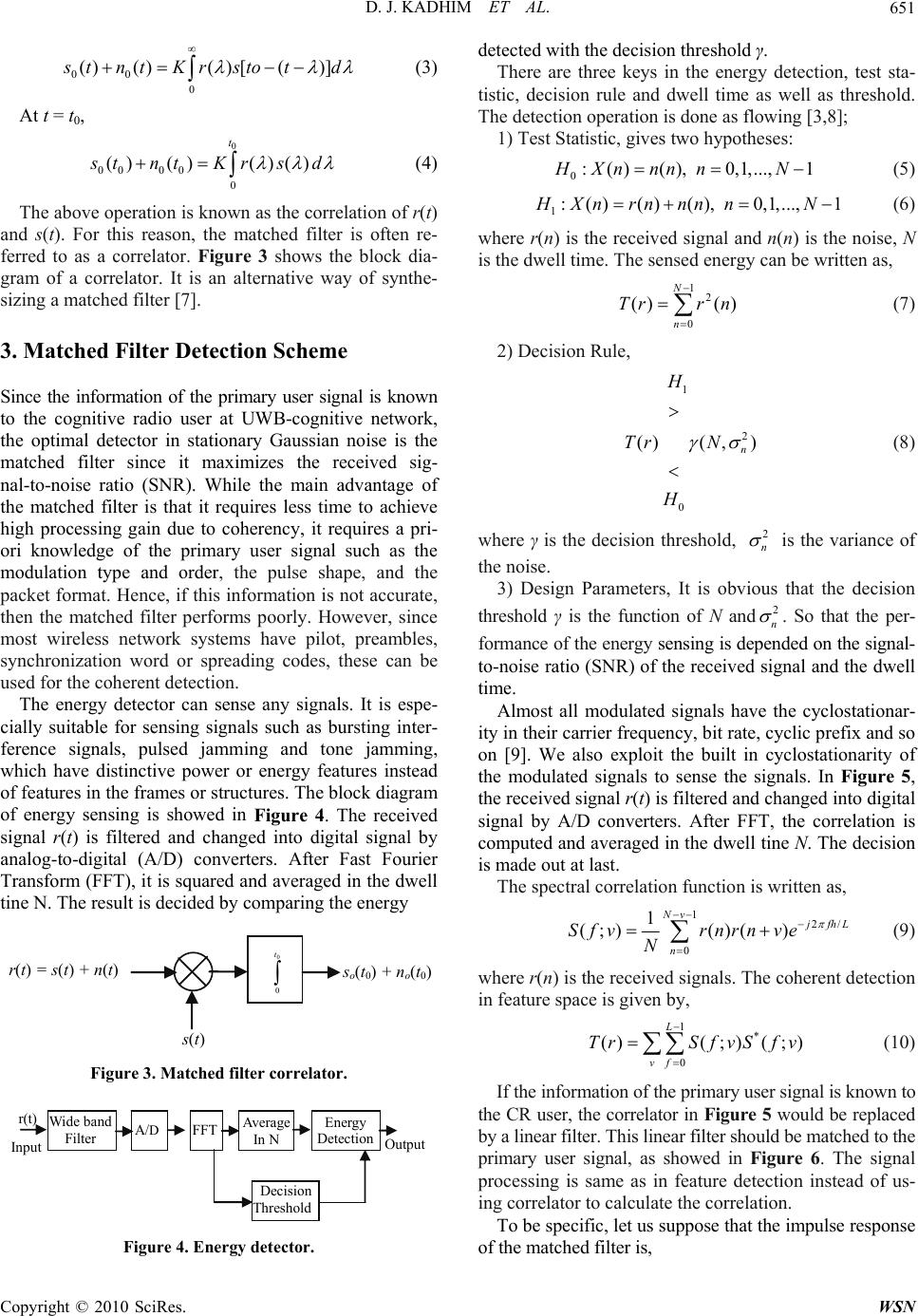

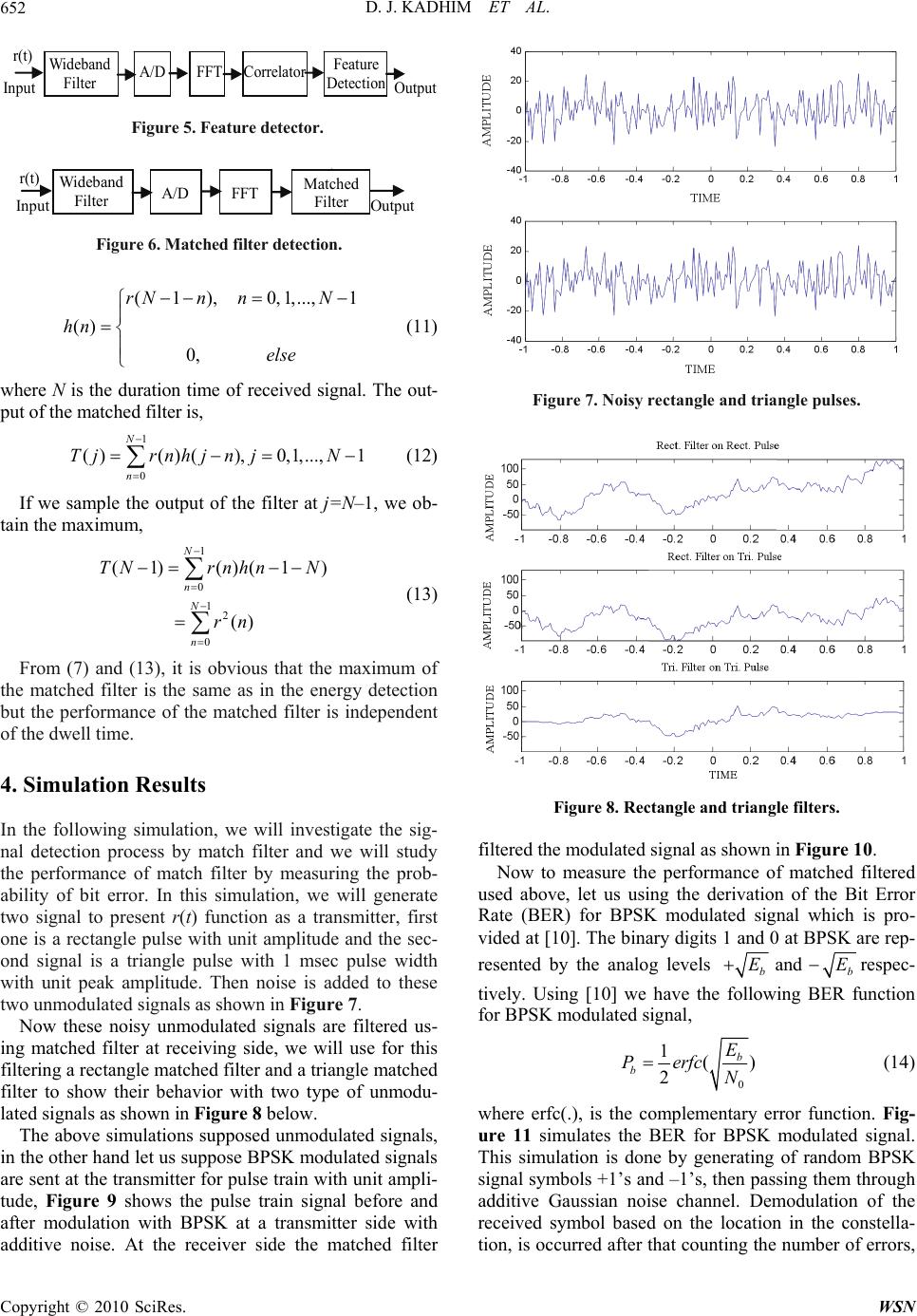

Wireless Sensor Network, 2010, 2, 649-654 doi:10.4236/wsn.2010.28077 Published Online August 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/wsn) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. WSN A Spectrum Sensing Framework for UWB-Cognitive Network Deah J. Kadhim, Saba Q. Jobbar Electrical Engineering Department, College of Engineering University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq E-mail: deya_naw@yahoo.com Received May 30, 2010; revised June 17, 2010; accepted June 28, 2010 Abstract Due to that the Ultra Wide Band (UWB) technology has some attractive features like robustness to multipath fading, high data rate, low cost and low power consumption, it is widely use to implement cognitive radio network. Intuitively, one of the most important tasks required for cognitive network is the spectrum sensing. A framework for implementing spectrum sensing for UWB-Cognitive Network will be presented in this pa- per. Since the information about primary licensed users are known to the cognitive radios then the best spec- trum sensing scheme for UWB-cognitive network is the matched filter detection scheme. Simulation results verified and demonstrated the using of matched filter spectrum sensing in cognitive radio network with UWB and proved that the bit error rate for this detection scheme can be considered acceptable. Keywords: Cognitive Radio, UWB, Spectrum Sensing, Matched Filter 1. Introduction With respect to the FCC regulation, Ultra Wideband (UWB) is a future technology for medium and short scope of wireless networks with a different of throughput choices containing very high data rates. The most im- portant property of UWB is that it can presence in the same temporal, spatial, and spectral domains with li- censed/unlicensed users because it is an underlay system. Other seductive features of UWB include the flexibility of adapting pulse shape, bandwidth, data rate, and trans- mit power. At the head of these characteristics, UWB has low power consumption so the complexity of the trans- ceiver will be reduced and this will lead to form a limited system cost. Note that there is another important feature of UWB represented by providing secure communica- tions as a result detecting UWB transmission will be very hard since the power spectrum will embed into the noise floor. There are two commonly proposed means of im- plementing UWB. These two technologies are the Or- thogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing based UWB (UWB-OFDM) and the impulse radio based UWB (IR-UWB) [1,2]. Most of today's wireless networks are characterized by a fixed spectrum assignment policy. Unfortunately, only few frequency resources are currently available for future applications. Recent measurements indicate that many portions of licensed spectrum are not used for significant periods of time. Cognitive radio is a new technology used to improve the spectrum utilization by allowing secondary users (cognitive radios) to borrow unused ra- dio spectrum from primary users (licensed users) or to share the spectrum with them. A network with a cogni- tive process that observes its environment current condi- tions and learn from these conditions in order to decide and plan then make some adaptations for their work to qualify its communication environment, this network called cognitive radio network [3]. UWB communication systems can be presented as a first example of technology that is coincidence for the implementation of cognitive radio mechanism. UWB systems are preferable because of their large bandwidth, their low-power noise-like signaling, which can be ex- ploited in the transmission over (licensed) bands pro- ducing a controlled level of interference on existing com- munication systems. Thus recent researches has been focused on the investigation of coexistence issues related to the UWB technology, assuming that such systems will operate in an environment characterized by the presence of heterogeneous interfering users. The essential com- ponent of Ultra Wideband-based Cognitive Network (UWB-CN) is the spectrum sensing in which a cognitive radio user can find only an unused band of the spectrum, so it should closely monitor the whole spectrum bands, note their information, and then detect spectrum holes [4,5].  D. J. KADHIM ET AL. 650 In this paper we will focus our work on implementing the spectrum sensing in UWB-CN. Intuitively, we could make a conclusions on using matched filter spectrum sensing scheme to implement the spectrum sensing for UWB-CN. This conclusion is that matched filter requires prior information about the characteristics of primary users’ signals and this information are known for Cogni- tive radios in UWB-CN system so it is the optimal spec- trum sensing scheme for UWB-CN system. Note that matched filter is used for maximizing the signal to noise ratio for a given input signal in presence of additive white Gaussian noise. This paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we describe the framework of spectrum sensing for UWB- Cognitive network. Section 3, gives the description de- tails of implementing matched filter detection. Section 4, shows the presents our computer simulation results. The conclusions are drawn in Section 5. 2. Spectrum Sensing Framework To discover which spectrum sensing schemes is the most efficient and suitable to the UWB-cognitive network system, for this discovering we need to do the following discussion; when the receiver cannot gather sufficient information about primary users, the optimal detector may be the energy detector. However, due to non-coherent processing O(1/SNR2) samples are required to meet a probability of detection constraint. Moreover, energy detectors often generate false alarms announced by un- wanted signals or multiple secondary users because they cannot discriminate signal types. Generally, modulated signals can be defined as the signals which are characterized by a periodic and Cyc- lostationary features. These features can be analyzed and detected by using a spectral correlation function. The attractive property of feature detection scheme is its firmness to uncertainty in noise power. But the main disadvantage of this scheme is the complex calculations and requires great effort and more time. Moreover, it needs additional bandwidth and subject to the radio fre- quency, spectrum loss of strong signals and timing or frequency jitters. When the information of the primary user signal is known to the CR user, the optimal detector in stationary Gaussian noise is the matched filter detection. The main advantage of matched filter is that due to coherency, it requires less time to achieve high processing gain since only O(1/SNR) samples are needed to meet a given probability of detection constraint. However, the matched filter requires a priori knowledge of the characteristics of the primary user signal. On the other hand, matched filter detection requires accurate time and frequency synchro- nization. From what has been discussed above, we may draw the conclusion that the matched filter detection is the optimal spectrum sensing scheme in the UWB-CR because the priori knowledge of the primary user signals in the UWB-CR system is known to the CR user. 2.1. Matched Filter A matched filter is a correlation function between a known signal or template, with an unknown signal to de- tect the presence of the template in the unknown signal and it is equivalent to a convolution function between the unknown signal with a time-reversed version of the tem- plate. It is the optimal linear filter for maximizing the signal to noise ratio (SNR) in the presence of additive stochastic noise. Matched filters are commonly used in radar, in which a signal is sent out, and we measure the reflected signals, looking for something similar to what was sent out [6]. A matched filter is a linear filter designed to maximize the output signal-to-noise ratio for a given input signal. Suppose that a signal s(t) plus additive white Gaussian noise n(t) is input to an linear time-invariant filter fol- lowed by a sampler, as shown in Figure 1 [7]. Figure 2 shows the characteristics of a matched filter. The impulse response of the matched filter h(t) is a de- layed version of the mirror image of s(t). In general, the matched filter is not a physically realizable (causal) fil- ter. 0 ()( )htKst t (1) 2.2. Matched Filter Correlator If r (t) = s(t) + n(t) is the received signal to the input of a causal matched filter, then the output of the filter can be found by convolving the received signal r(t) with the impulse response of the filter. Therefore; 00 0 ()()()*()() () s tnt rthtrhtd (2) Using Equation (2), then we get, Received Signal LTI Filter H(f) s(t) + n(t) s o (t) + n o (t) t = t 0 s o (t 0 ) + n o (t 0 ) Figure 1. Matched filter presentation. s(–t) –t 0 0 s(t) 0 t 0 h(t) = s(t 0 – t) 0 t 0 Figure 2. Matched filter characteristics. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. WSN  D. J. KADHIM ET AL.651 00 0 ()()( )[()] s tnt Krstotd (3) At t = t0, 0 00 00 0 () ()()() t s tnt Krsd (4) The above operation is known as the correlation of r(t) and s(t). For this reason, the matched filter is often re- ferred to as a correlator. Figure 3 shows the block dia- gram of a correlator. It is an alternative way of synthe- sizing a matched filter [7]. 3. Matched Filter Detection Scheme Since the information of the primary user signal is known to the cognitive radio user at UWB-cognitive network, the optimal detector in stationary Gaussian noise is the matched filter since it maximizes the received sig- nal-to-noise ratio (SNR). While the main advantage of the matched filter is that it requires less time to achieve high processing gain due to coherency, it requires a pri- ori knowledge of the primary user signal such as the modulation type and order, the pulse shape, and the packet format. Hence, if this information is not accurate, then the matched filter performs poorly. However, since most wireless network systems have pilot, preambles, synchronization word or spreading codes, these can be used for the coherent detection. The energy detector can sense any signals. It is espe- cially suitable for sensing signals such as bursting inter- ference signals, pulsed jamming and tone jamming, which have distinctive power or energy features instead of features in the frames or structures. The block diagram of energy sensing is showed in Figure 4. The received signal r(t) is filtered and changed into digital signal by analog-to-digital (A/D) converters. After Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), it is squared and averaged in the dwell tine N. The result is decided by comparing the energy 0 0 t s o (t 0 ) + n o (t 0 ) r(t) = s(t) + n(t) s(t) Figure 3. Matched filter correlator. r(t) Input Output Wide band Filter A/ D FFT Average In N Energy Detection Decision Threshold Figure 4. Energy detector. detected with the decision threshold γ. There are three keys in the energy detection, test sta- tistic, decision rule and dwell time as well as threshold. The detection operation is done as flowing [3,8]; 1) Test Statistic, gives two hypotheses: 0:( )( ),0,1,...,1HXn nnnN (5) 1:( )( )( ),0,1,...,1HXnrn nnnN (6) where r(n) is the received signal and n(n) is the noise, N is the dwell time. The sensed energy can be written as, 12 0 () () N n Trrn (7) 2) Decision Rule, 1 2 0 () (,) n H Tr N H (8) where γ is the decision threshold, 2 n is the variance of the noise. 3) Design Parameters, It is obvious that the decision threshold γ is the function of N and2 n . So that the per- formance of the energy sensing is depended on the signal- to-noise ratio (SNR) of the received signal and the dwell time. Almost all modulated signals have the cyclostationar- ity in their carrier frequency, bit rate, cyclic prefix and so on [9]. We also exploit the built in cyclostationarity of the modulated signals to sense the signals. In Figure 5, the received signal r(t) is filtered and changed into digital signal by A/D converters. After FFT, the correlation is computed and averaged in the dwell tine N. The decision is made out at last. The spectral correlation function is written as, 12/ 0 1 (;)()() Nv j fh L n Sfvrnrnve N (9) where r(n) is the received signals. The coherent detection in feature space is given by, 1* 0 ()( ;)( ;) L vf TrS fvSfv (10) If the information of the primary user signal is known to the CR user, the correlator in Figure 5 would be replaced by a linear filter. This linear filter should be matched to the primary user signal, as showed in Figure 6. The signal processing is same as in feature detection instead of us- ing correlator to calculate the correlation. To be specific, let us suppose that the impulse response of the matched filter is, Copyright © 2010 SciRes. WSN  D. J. KADHIM ET AL. 652 r(t) Input Output Wideband Filter A/D FFT Correlator Feature Detection Figure 5. Feature detector. r(t) Input Wideband Filter A/D FFT 3 Matched Filter Output Figure 6. Matched filter detection. (1),0, 1,...,1 () 0, rNn nN hn else (11) where N is the duration time of received signal. The out- put of the matched filter is, 1 0 ()()(),0,1,...,1 N n TjrnhjnjN (12) If we sample the output of the filter at j=N–1, we ob- tain the maximum, 1 0 12 0 (1) ()(1) () N n N n T NrnhnN rn (13) From (7) and (13), it is obvious that the maximum of the matched filter is the same as in the energy detection but the performance of the matched filter is independent of the dwell time. 4. Simulation Results In the following simulation, we will investigate the sig- nal detection process by match filter and we will study the performance of match filter by measuring the prob- ability of bit error. In this simulation, we will generate two signal to present r(t) function as a transmitter, first one is a rectangle pulse with unit amplitude and the sec- ond signal is a triangle pulse with 1 msec pulse width with unit peak amplitude. Then noise is added to these two unmodulated signals as shown in Figure 7. Now these noisy unmodulated signals are filtered us- ing matched filter at receiving side, we will use for this filtering a rectangle matched filter and a triangle matched filter to show their behavior with two type of unmodu- lated signals as shown in Figure 8 below. The above simulations supposed unmodulated signals, in the other hand let us suppose BPSK modulated signals are sent at the transmitter for pulse train with unit ampli- tude, Figure 9 shows the pulse train signal before and after modulation with BPSK at a transmitter side with additive noise. At the receiver side the matched filter Figure 7. Noisy rectangle and triangle pulses. Figure 8. Rectangle and triangle filters. filtered the modulated signal as shown in Figure 10. Now to measure the performance of matched filtered used above, let us using the derivation of the Bit Error Rate (BER) for BPSK modulated signal which is pro- vided at [10]. The binary digits 1 and 0 at BPSK are rep- resented by the analog levels and bb EErespec- tively. Using [10] we have the following BER function for BPSK modulated signal, 0 1( 2 b b E Perfc N ) (14) where erfc(.), is the complementary error function. Fig- ure 11 simulates the BER for BPSK modulated signal. This simulation is done by generating of random BPSK signal symbols +1’s and –1’s, then passing them through additive Gaussian noise channel. Demodulation of the received symbol based on the location in the constella- tion, is occurred after that counting the number of errors, Copyright © 2010 SciRes. WSN  D. J. KADHIM ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. WSN 653 Figure 9. Pulse train before and after modulation in time and frequency domains. Figure 10. Receiver matched filter output in time and frequency domains. then repeating the same procedure for multiple Eb/N0 value. some of the main requirements for implementing cogni- tive radio networks, these features such as avoidance the interference with licensed primary users, dynamically adaptable bandwidth, data rate and transmitted power. The second reason is concerned with the objective issues that can come with implementing UWB technology in cognitive radio networks, these objective issues are such as locating cognitive nodes via UWB, exchanging the sensing information between cognitive nodes using UWB 5. Conclusions UWB technology implementation plays a great role in cognitive radio networks; this conclusion comes from two main reasons. The first reason is the features of UWB which are presented as a good chance to achieve  D. J. KADHIM ET AL. 654 -2 0246810 10 -5 10 -4 10 -3 10 -2 10 -1 Eb/No, dB Bit Error Rate E b /N 0 , dB Figure 11. Bit error probability curve for BFSK modulation. and the receiving sensitivity of the nodes in the network that has an integral role in determining the range and size of communication networks. Simulation results showed that the matched filter de- tection scheme is a suitable for detecting signals through UWB-cognitive radio network especially all information required for sensing primary users are known for cogni- tive radios. However, in the UWB system, the architec- ture of the UWB signals is known, but the band location and occupancy level is unknown. Thus, new techniques are required to measure or estimate the precise locations of primary users at nearby cognitive radios or secondary users. 6. References [1] D. L. Sostanovsky and A. O. Boryssenko, “Experimental UWB Sensing and Communication System,” IEEE Aero- space and Electronic Systems Magazine, Vol. 21, No. 2, February 2006, pp. 27-29. [2] K. Wallace, B. Parr, B. Cho and Z. Ding, “Performance Analysis of A Spectrally Compliant Ultra-Wideband Pulse Design,” IEEE Transactions on Wireless Com- munications, Vol. 4, September 2005, pp. 2172-2181. [3] D. Cabric, S. M. Mishra and R. W. Brodersen, “Impleme- ntation Issues in Spectrum Sensing for Cognitive Radios,” Proceedings of 38th Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems and Computers, Pacific Grove, November 2004, pp. 772-776. [4] H. Arslan and M. E. Sahin, “Ultra Wideband Wireless Communication, ch. Narrowband Interference Issues in Ultrawideband Systems,” Wiley, Hoboken, September 2006. [5] S. Zhang and Z. Bao, “Strategy of Anti-Interference Based on Cognitive Radio in Ultra-Wideband System,” 4th International Conference on Wireless Communi- cations, Dalian, 2008. [6] I. Akyildiz, W. Lee, M. Vuran and S. Mohanty, “Next Generation/Dynamic Spectrum Access/Cognitive Radio Wireless Networks: A Survey,” Computer Networks, Vol. 50, No. 13, September 2006, pp. 2127-2159. [7] I. Akyildiz, W. Lee, M. Vuran and S. Mohanty, “A Survey on Spectrum Management in Cognitive Radio Networks,” IEEE Communications Magazine, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, April 2008. [8] H. Urkowitz, “Energy Detection of Unknown Deterministic Signals,” Proceedings of IEEE, Vol. 55, April 1967, pp. 523-531. [9] J. Lund´en, V. Koivunen, A. Huttunen and V. Poor, “Spectrum Sensing in Cognitive Radios Based on Multiple Cyclic Frequencies,” Signal processing Laboratory, Helsinki Univercity of Technology, Helsinki, July 2007. [10] J. G. Proakis, “Digital Communications,” 4th Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York, 2001. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. WSN |