The Impact of Clinical Pharmacist Interventions on Drug and Antibiotic Prescribing in a Teaching Hospital in Cairo

460

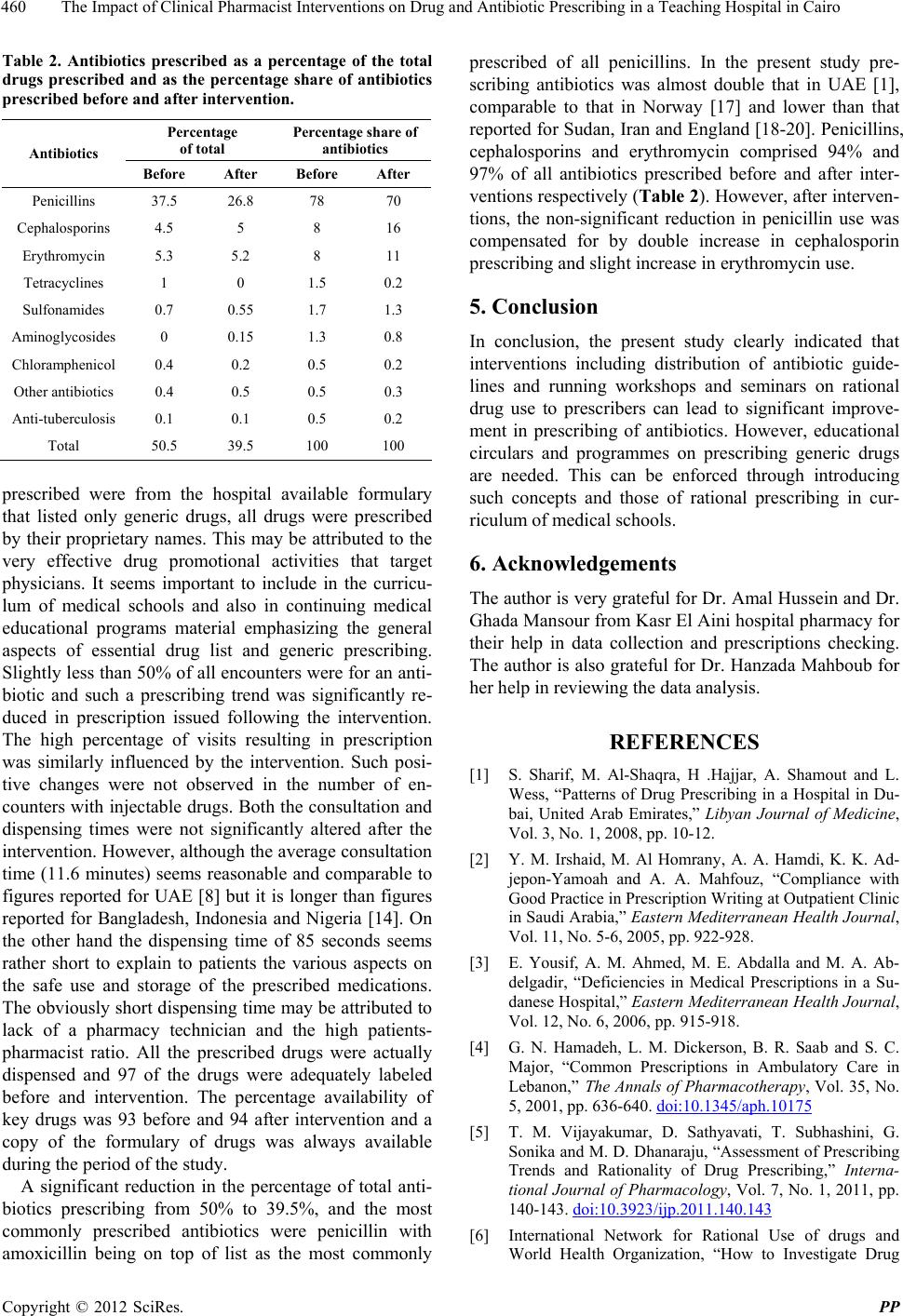

Table 2. Antibiotics prescribed as a percentage of the total

drugs prescribed and as the percentage share of antibiotics

prescribed before and after intervention.

Percentage

of total Percentage share of

antibiotics

Antibiotics

Before After Before After

Penicillins 37.5 26.8 78 70

Cephalosporins 4.5 5 8 16

Erythromycin 5.3 5.2 8 11

Tetracyclines 1 0 1.5 0.2

Sulfonamides 0.7 0.55 1.7 1.3

Aminoglycosides 0 0.15 1.3 0.8

Chloramphenicol 0.4 0.2 0.5 0.2

Other antibiotics 0.4 0.5 0.5 0.3

Anti-tuberculosis 0.1 0.1 0.5 0.2

Total 50.5 39.5 100 100

prescribed were from the hospital available formulary

that listed only generic drugs, all drugs were prescribed

by their proprietary names. This may be attributed to the

very effective drug promotional activities that target

physicians. It seems important to include in the curricu-

lum of medical schools and also in continuing medical

educational programs material emphasizing the general

aspects of essential drug list and generic prescribing.

Slightly less than 50% of all encounters were for an an ti-

biotic and such a prescribing trend was significantly re-

duced in prescription issued following the intervention.

The high percentage of visits resulting in prescription

was similarly influenced by the intervention. Such posi-

tive changes were not observed in the number of en-

counters with injectable drugs. Both th e consultation and

dispensing times were not significantly altered after the

intervention. Howev er, although the average co nsultation

time (11.6 minutes) seems reasonable and comparable to

figures reported for UAE [8] but it is longer than figures

reported for Bangladesh, Indonesia and Nigeria [14]. On

the other hand the dispensing time of 85 seconds seems

rather short to explain to patients the various aspects on

the safe use and storage of the prescribed medications.

The obviously short dispensing time may be attributed to

lack of a pharmacy technician and the high patients-

pharmacist ratio. All the prescribed drugs were actually

dispensed and 97 of the drugs were adequately labeled

before and intervention. The percentage availability of

key drugs was 93 before and 94 after intervention and a

copy of the formulary of drugs was always available

during the period of the study.

A significant reduction in the percentage of total anti-

biotics prescribing from 50% to 39.5%, and the most

commonly prescribed antibiotics were penicillin with

amoxicillin being on top of list as the most commonly

prescribed of all penicillins. In the present study pre-

scribing antibiotics was almost double that in UAE [1],

comparable to that in Norway [17] and lower than that

reported for Sud an, Iran and England [18-20]. Penicillins,

cephalosporins and erythromycin comprised 94% and

97% of all antibiotics prescribed before and after inter-

ventions resp ectively ( Table 2). Howev er, after interven-

tions, the non-significant reduction in penicillin use was

compensated for by double increase in cephalosporin

prescribing and slight increase in erythromycin use.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study clearly indicated that

interventions including distribution of antibiotic guide-

lines and running workshops and seminars on rational

drug use to prescribers can lead to significant improve-

ment in prescribing of antibiotics. However, educational

circulars and programmes on prescribing generic drugs

are needed. This can be enforced through introducing

such concepts and those of rational prescribing in cur-

riculum of medical schools.

6. Acknowledgements

The author is very grateful for Dr. Amal Hussein and Dr.

Ghada Mans our from Kasr El Aini hospital ph armacy for

their help in data collection and prescriptions checking.

The author is also grateful for Dr. Hanzada Mahboub for

her help in reviewing the data analysis.

REFERENCES

[1] S. Sharif, M. Al-Shaqra, H .Hajjar, A. Shamout and L.

Wess, “Patterns of Drug Prescribing in a Hospital in Du-

bai, United Arab Emirates,” Libyan Journal of Medicine,

Vol. 3, No. 1, 2008, pp. 10-12.

[2] Y. M. Irshaid, M. Al Homrany, A. A. Hamdi, K. K. Ad-

jepon-Yamoah and A. A. Mahfouz, “Compliance with

Good Practice in Prescription Writing at Outpatient Clinic

in Saudi Arabia,” Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal,

Vol. 11, No. 5-6, 2005, pp. 922-928.

[3] E. Yousif, A. M. Ahmed, M. E. Abdalla and M. A. Ab-

delgadir, “Deficiencies in Medical Prescriptions in a Su-

danese Hospital,” Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal,

Vol. 12, No. 6, 2006, pp. 915-918.

[4] G. N. Hamadeh, L. M. Dickerson, B. R. Saab and S. C.

Major, “Common Prescriptions in Ambulatory Care in

Lebanon,” The Annals of Pharmacotherapy, Vol. 35, No.

5, 2001, pp. 636-640. doi:10.1345/aph.10175

[5] T. M. Vijayakumar, D. Sathyavati, T. Subhashini, G.

Sonika and M. D. Dhanaraju, “Assessment of Prescribing

Trends and Rationality of Drug Prescribing,” Interna-

tional Journal of Pharmacology, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2011, pp.

140-143. doi:10.3923/ijp.2011.140.143

[6] International Network for Rational Use of drugs and

World Health Organization, “How to Investigate Drug

Copyright © 2012 SciRes. PP