Modern Economy, 2012, 3, 567-577 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/me.2012.35075 Published Online September 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/me) Aid Effectiveness and Capacity Development: Implications for Economic Growth in Developing Countries Prabuddha Sanyal1, Suresh C. Babu2 1Resilience and Regulatory Effects, Organization 6921, Sandia National Laboratory, Albuquerque, USA 2International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Washington DC, USA Email: psanyal@sandia.gov Received May 4, 2012; revised June 10, 2012; accepted June 20, 2012 ABSTRACT In this paper, we present a stylized model for understanding the relationship between capacity strengthening and eco- nomic growth in an endogenous growth framework. Endogenous growth theory provides a novel starting point for combining individual, organizational, and enabling environmental issues as part of attaining the capacity-strengthening goal. Our results indicate that although donors can play an important role in aiding countries to develop their existing capacities or to generate new ones, under certain conditions, the potential also exists for uncoordinated and fragmented donor activities to erode country capacities. From the policy exercises, we demonstrate that improving economy-wide learning unambiguously increases the rate of growth of output, technology, capital stock, and capacity. Moreover, a donor’s intervention has the maximum impact on the above variables when the economy’s capacity is relatively low. In contrast, donor intervention can lead to “crowding-out effects” when the economy’s capacity is moderately high. Under such a situation, the economy never reaches a new steady state. Our results not only lend support to diminishing returns to aid but also to an S model of development aid and country capacity relationship. Keywords: Capacity Strengthening; Development Aid; Economic Growth; Learning 1. Introduction Increased interest in capacity strengthening in recent years is a response to widely acknowledged shortcomings in development assistance over the past 50 years. For exam- ple, the dominant role of donor-led development projects with inadequate attention paid to long-term capacity is- sues is often cited as a critical factor in the slow progress [1]. The 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness em- phasizes the need for significantly enhanced support for country efforts to strengthen capacity and improve devel- opment outcomes. The declaration calls for capacity stre- ngthening to be an explicit objective of national devel- opment and poverty reduction strategies. In Africa, for example, the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) has identified capacity constraints as the main obstacle to economic growth and sustainable development. Although a quarter of donor aid, or more than US$15 bil- lion a year, has gone into “technical cooperation,”1 evalua- tion results confirm that development of sustainable ca- pacity remains one of the most difficult areas of interna- tional development practice. Capacity strengthening has also been one of the least-responsive targets of donor as- sistance, lagging behind other slow areas such as infra- structure development or improving health [2]. The motivation behind this study arises from the con- trast between the increasingly recognized importance of capacity in development outcomes and the difficulty of achieving it. Several broad strategies can be followed, either separately or in combination, to strengthen capac- ity. If a simple deficiency in resources is the root cause of weak capacity, then supplying additional financial and physical resources will be beneficial. One variant of this method would be to assist in improving organizational capabilities so they perform better in terms of obtaining its objectives. This may require providing technical assis- tance or training, assuming the gaps are identified to achieve better performance. A related strategy proposes promoting innovations and providing opportunities for learning and experimentation. Much of this strategy fo- cuses on the promotion of social capital, including col- laboration, civic engagement, and loyalty. These approa- ches aim to encourage individuals and organizations to work better together in order to promote a holistic view of development [3]. 1Estimates of donor-assisted capacity development efforts suggest that more than a quarter of total net official development assistance is spent on technical cooperation. In 2004, the total amount spent by DAC members on technical cooperation with developing countries and mul- tilateral or anizations amounted to US$20.8 billion 2 . Strengthening the overall organizational system for work C opyright © 2012 SciRes. ME  P. SANYAL, S. C. BABU 568 synchronization and execution of complex tasks can enhance preexisting systems to carry out certain key functions [4]. In this approach, organizations are seen as processing systems that change individual and system capacities into organizational results. This approach seeks to improve an organization’s overall performance by bre- aking down its activities, making recommendations about improvements, and then integrating these improvements back into wider organizational performance. The role of institutions is to provide knowledge of and access to “the rules of the game,” thus empowering certain actors to create, alter, and learn from the processes and rules that govern society. However, equating institution building with public sector reforms can be problematic, and reform of entire systems or sectors, such as agriculture, education, and health, is important for capacity strengthening [5]. The systems approach focuses more on transformation change and the best ways to achieve it. In this approach, capacity arises out of interrelationships and interactions among the system’s various elements. An all-inclusive strategy for capacity strengthening should be targeted at multiple levels and actors, and it should include an at- tempt to understand the linkages among them. In this approach, capacity strengthening is a dynamic process whereby complex networks of actors seek to enhance their performance by doing what they do better, both by their own initiatives and through interactions with out- siders [6]. From this perspective, capacity strengthening is achieved through combining individual and collective abilities into a larger overall systems capacity. In this paper, capacity strengthening is defined2 as the process of developing human resources, creating new forms of organizations and institutions, building innova- tive networks, and integrating country ownership in order to improve the efficiency of the learning activities (i.e., technical, organizational, institutional, and policy learn- ing). The efficiency of these learning activities, in turn, depends on the economic and political systems, as well as on the social infrastructure and institutions. The im- provement in learning activities results in better knowl- edge about policy processes and program development, leading to better development outcomes. Our definition is based on two observations: 1) Country ownership is critical to development performance, and this applies to both generic capacities, such as the ability to plan and manage organizational changes and service improvements and specific capacities in critical fields such as health or public sector management and 2) Country ownership of policies and programs is the means to sustained develop- ment effectiveness. Ownership will not begin to emerge in the absence of sufficient local capacity. The rest of this paper is organized as follows: In the next section, we define capacity strengthening and em- phasize its importance in development outcomes. Next, we postulate an endogenous growth model to understand how the relationship between own-country capacity re- sources and donor-supported capacity resources affects economic growth and state a few propositions related to the steady state solutions of the model. In Section 4, we undertake some comparative static exercises and derive some implications of the results. Section 5 concludes em- phasizing how our model lends support to not only di- minishing returns to aid but also an S-model of the rela- tionship between development aid and country capacity. 2. Brief Overview of the Literature Although the concept of capacity strengthening has regai- ned renewed interest among international development pra- ctitioners, adequate national capacity remains a critical fac- tor in the current efforts to meet the Millennium Devel- opment Goals (MDGs). Yet even with increased funding, development efforts will not be able to achieve their goals if attaining sustainable capacity is not given greater and more careful attention [2]. The issue is increasingly being recognized by both donor organizations and developing countries, as emphasized in the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness and Accra High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness held in Accra, Ghana during 2008 [2]3. Capacity strengthening remains a major challenge for many developing countries. At first, it was primarily viewed as a technical assistance process, involving the transfer of knowledge or organizational models from north to south [7]. Technical cooperation and various forms of capacity-strengthening activities have absorbed substantial funds over many decades. Although a few countries have used such funds effectively, donor efforts in many countries have produced little or even negative results in terms of sustainable local capacity [8]. This is particularly relevant for many African economies, where, after investments of millions of dollars to improve the capacity of African governments, donors have begun to question the merits of their policies in building capacity via technical assistance [9]. Simultaneously, evidence suggests that development aid is highly uncoordinated and fragmented [10]. With 56 bilateral donors and more than 230 international organ- izations, there are currently about 60,000 development aid projects. The average number of donors per country 3This declaration rests on five pillars: 1) ownership—developing coun- tries exercise leadership over their development policies and plans; 2) alignment—donors base their support on countries’ development strategies and systems; 3) harmonization—donors coordinate their activities and minimize the cost of delivering aid; 4) managing for results—donors and developing countries orient their activities to achieve the desired results; and 5) mutual accountability—donors and developing countries are accountable to each other for progress in mana in aid better and in achievin develo ment results. 2Although there are various definitions in the literature (for example, [3,7,8]), we chose the above definition as it emphasizes the country ownership and system definition of capacity strengthening. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. ME  P. SANYAL, S. C. BABU 569 almost tripled during the past 50 years—from 12 in the 1960s to 33 in recent years. The proliferation of the number of donors has created chaos in donor practices and has led to inefficient aid-delivery mechanisms [11]. In addition, after several decades of economic crises, developing country governments have adopted wide-ran- ging reform programs, often on the advice of multilateral institutions. The lack of country capacity to implement these programs, however, has been alluded to as a major factor behind the failure of the reform programs [12]. Finally, it is now well accepted that solutions imposed unilaterally by donor agencies from outside the country cannot address the problems and concerns of many dev- eloping country governments. Thus, national governments must be willing to take “ownership” of their programs and control forces that affect the economy and polity [13]. The new consensus, as expressed in the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, sees capacity strength- ening as an endogenous process, strongly led from within a country, with donors playing only a supportive role. According to this idea, capacity strengthening involves much more than enhancing the skills and knowledge of individuals. Rather, it critically depends on the quality of the organizations in which individuals work. In turn, the effectiveness of those organizations is influenced by the “enabling environment” in which they are embedded. Capacity, in this view, is not only about skills and pro- cedures, but also about incentives, organizational effect- tiveness, and governance. Yet, it is not clear how com- bining individual skills, organizational restructuring, and an enabling environment could be enhanced through an endogenous process. In light of the above, several questions remain: What is the optimal level of country capacity strengthening required to achieve specific economic growth targets? What conce- ptual approaches could help us understand the relation- ship between national capacity and economic growth? Un- der what conditions does donor intervention improve or displace country capacity? Currently, little attention is paid to these questions in the economic development literature. The next section presents a stylized model for under- standing the relationship between capacity strengthening and economic growth in an endogenous growth framework. The motivation is that the development literature lacks a theoretical framework for addressing capacity develop- ment issues. Currently, most studies treat human capital as individual skills. At the same time, the literature treats the organizational culture, institutional arrangements, and political processes under which capacity strengthening operates as exogenous. 3. Theoretical Model of the Relationship between Capacity and Economic Growth This section presents a theoretical model for understand- ing the relationship between capacity investments and gro- wth outcomes. The model extends the framework devel- oped by [14] and further extended by [15]. Let the economy comprise two sectors: a goods-pro- ducing sector and a research and development (R&D) sector. The former produces conventional output, while the latter produces new technology, which adds to the existing level of technology. Four factors of production in the economy—namely, capital (K), labor (L), human capital (H), and capacity resources (CK)4—are allocated for use in either the goods or the R&D sector. The capac- ity resources can be conceived of not only as sectoral programs allocated by the government for health, water and sanitation, and irrigation development (to name a few) but also as improved learning that occurs from in- teractions among the system of actors (firms, organizations, government, consumers, etc.) that influence an economy’s innovation performance. Capacity resource devoted to program development is a process through which values and resources are authoritatively allocated for the econ- omy as a whole. It is a process whereby a representative government puts forward measures to accomplish some desired objectives. This process generally involves ex- penditure of resources—whether in terms of extractive, distributive, or other measures. We let aK denote the fraction of capital stock used in the R&D sector; aH denote the fraction of human capital used in the R&D sector; aL denote the fraction of labor used in the R&D sector; aCK denote the fraction of capacity resources used in the R&D sector; This implies the following: 1aK is the fraction of capital stock used in the goods- producing sector; 1aH is the fraction of human capital used in the goods-producing sector; 1 a is the fraction of labor used in the goods-pr- oducing sector; 1a 4Capacity strengthening can also be understood from a production function perspective, in which overall capacity is produced as a func- tion of individual, organizational, and enabling environment. Although this approach can provide some additional insights into the dynamics o capacity formation, we do not consider this approach in the present aper, as our main purpose is to understand how capacity is related to economic growth and under what conditions capacity leads to higher steady-state growth. CK is the fraction of capacity resources used in the goods-producing sector; Technology has the characteristic of being non-rival. Hence, the entire level of technology (A) is used in both sectors. Output in time t is given by Copyright © 2012 SciRes. ME  P. SANYAL, S. C. BABU 570 11 11 tKt H CK tt YK CK A 1 t L t H L (1) with 0 < α < 1, 0 < β < 1, 0 < γ < 1, α + β + γ < 1. In Equation (1), it is not important to know how CK is allocated (although in a more dynamic setting, how CK is allocated can have important implications for economic growth). To the best of our knowledge, the literature has not explicitly considered who allocates ca- pacity resources. This person or entity can be the social planner or even the donor. [16] provided the only model that identifies ways in which policymakers can influence the trajectory of their economies. This mechanism works mainly through choices regarding family size and in- vestment in children. In their model, developing coun- tries that have high levels of political capacity, protect civil liberties, and have low levels of political instability are the ones most likely to develop successfully. The political factors influence development outcomes through demographic transition to a low birth rate and the in- centives to invest in physical capital. We assume Cobb-Douglas technology for analytical tractability. The level of innovation in the economy de- pends not only on the amount of capital, labor, and hu- man capital devoted to the R&D sector but also on the capacity resources necessary to maintain and upgrade the current level of technology5. We assume a generalized Cobb-Douglas production function with increasing re- turns for the R&D sector. ab tKtHtCK cd tLtt BKHCK LA tt (2) with B, a, b, c, d, σ > 0. The savings rate is exogenous and constant, and depre- ciation is assumed to be 0 for simplicity. This implies that sY ttt t LH mH tttt HCK Y (3) with 0 ≤ s ≤ 1 We treat population growth and human capital growth to be constant and exogenous, so that Ln (4) with n, m ≥ 0 The equation for motion of capacity strengthening is given by CK (5) with λ, > 0 We treat as exogenous to the host country’s decision to invest in capacity resources. However, in a more real- istic setting, where the government seeks to maximize a utility function that depends on capital expenditures, the government’s recurrent expenditure, tax and nontax revenues, and various kinds of aid (e.g., project aid, pro- gram aid from all donors, technical assistance, and food aid subject to the government’s budget constraints), will depend on the above factors and will be endogenous (see, for example [17]). It will also depend on the coun- try’s balance of payments situation. We assume away such complexities from the present model, because our main focus is to understand the relationship between ca- pacity resources and economic growth. The rationale for Equation (5) is derived from [18], in which an individual capital investment model is used to study social capital formation. Capacity formation takes long periods, with λ denoting the learning aspects of ca- pacity through formal education, job training, and non- formal education, while denotes a parameter that cap- tures how capacity resources devoted by an external agent (e.g., a donor agency) are utilized by the host country government for improving country capacity over time. The implicit assumption made here is that aid is absorbed and spent by the recipient. In this case, the foreign ex- change is sold by the central bank and absorbed into the economy, and the government spends the associated re- sources. The challenge faced by monetary authorities is to manage the real exchange rate that may result. This assumption is reasonable, unless Dutch disease is a major concern or the return to public expenditure is extremely low [19]. We make this crucial distinction between do- mestic and external capacity resources, because capacity strengthening can be understood as individuals, organiza- tions, and institutions trying to improve capacity without external intervention. However, under the donor mandate, capacity can also be formed over time by utilizing pro- gram aid and technical assistance6. Proposition 1: For the steady-state rate of capacity to maintain or grow over time, there exists a * satisfying 2 , such that if > *, then the economy’s ca- pacity declines, thus affecting the economy’s steady-state rate of growth in the long run. The intuition of Proposition 1 can be understood in the following context: Suppose the economy’s capacity is really low, in that it lacks financial, human capital, and techni- cal resources. In this case, donors can play an important role in aiding countries develop their existing capacities by providing aid, such as program aid and technical as- sistance. The host/recipient country can use the aid to invest in material resources, infrastructure, and human capital resources, such as education and health services. Suppose, on the other hand, that the recipient country has an existing capacity that is moderately high, but donors 5For example, if a significant number of scientists and engineers move out of the country for better job prospects, then capacity re-sources invested in the country can erode over time, and the level of innova- tions may decline. 6We derive the steady state conditions for capital accumulation, tech- nological growth, and capacity. These results can be obtained from the authors upon request. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. ME  P. SANYAL, S. C. BABU 571 still try to control the projects (more project aid) until completion. As the wages and salaries in these projects are paid by donors at much higher rates than what the recipient government can afford, this process can possi- bly lead to “brain drain” away from the public services. If the country is in the midst of a prolonged adverse ex- ternal shock, the recipient country may be forced to re- duce its expenditures further. The combination of grow- ing costs and diminished budgets can result in a gradual erosion of the recipient country’s ability to meet its basic recurrent expenditures. Aid dependence then becomes a strategy for donors to keep projects alive so the recipient government’s recurrent costs are sustained. However, through the control of projects and programs, the donors erode the country’s capacity even further. We also derive the steady-state relationship between the growth rate of capital accumulation and growth rate of capacity and based on this relationship, we have the following proposition: Proposition 2: There exist critical values * and γ* such that if 21 is satisfied, then the economy’s steady-state growth rate of capital stock unambiguously increases, improving the economy’s growth rate in the long run. Proposition 2 states that as long as the elasticity of output with respect to capacity-strengthening resources does not come in conflict with the recipient country’s utilization of aid resources7, then the rate of growth of capital stock will improve in the long run. Next, we examine the steady-state relationship between the growth rate of technology and the growth rate of ca- pacity. Based on this relationship, we have the following proposition: Proposition 3: There exist critical values * and γ* such that if 112 c is satisfied, then the economy’s steady-state growth rate of technol- ogy will improve over time. The steady-state conditions is found by solving two equations with two unknowns—namely, the steady-state relationship between growth rate of capital accumulation and growth rate of capacity (proposition 2) and the steady- state relationship between the growth rate of technology and the growth rate of capacity. This is succinctly stated in proposition 4. Proposition 4: For the steady-state solution to exist8, the critical values of and γ must satisfy the following condition: 4. Policy Exercises In this section, we consider the steady-state effects of three scenarios that could result from different develop- ment policy interventions. The first exercise9 examines what happens if the rate of learning from human capital accumulation increases exogenously, which could result from a country experiencing an increase in the number of new schools or new adult educational programs. In the second exercise, we examine the role of the recipient country in asking for more aid from the donor and dou- bling its commitment to invest in capacity resources ( increasing from 0.8 to 1.6), when the elasticity of output with respect to capacity is low (we assume γ = 0.1). In the final exercise, we consider a similar situation of dou- bling of investment in capacity resources by the recipient country, but with the elasticity of output with respect to capacity being high (we assume γ = 0.35). We show that the predictions are very consistent with our theoretical model. 4.1. Increase in the Rate of Learning in the Economy ** ac c 0 A g 0 0g 1 0g 0g * * 2 12 Consider an exogenous increase in the rate of learning (λ) from greater human capital formation in the economy. From Figure 1, we find that an increase in λ results in decreasing the intercept of the locus; thus, there is a parallel downward shift from A to A. At the same time, an increase in λ results in an upward shift of the K 0 0g 1 0g 0 locus from K to K. Thus, the economy moves from E0 to E1 with the cones- quence that both the steady-state growth of technology and the growth rate of capital also increase, improving the growth rate of capacity. The intuition for this result is as follows: First, an in- crease in learning results in a larger stock of human capital in the economy. Assuming that the share of hu- man capital in the R&D sector remains unchanged, the increase in human capital resulting from an increase in the growth rate of learning leads to an increase in the growth rate of technology, from A 1 to A . The larger growth in human capital also results in an increase in the amount of resources being used in the conventional goods- producing sector. For this sector, the larger growth of the human capital stock that arises from greater learning and from the interactions among individuals and organiza- tions, accompanied with more rapid technological growth from the R&D sector, leads to an increase in the growth 8For the sake of brevity, we do not provide the proofs of the above ropositions. These proofs can be obtained from the authors upon e- quest. 9Throughout the exercises, we assume the following values of the pa- rameters for the hypothetical economy: α = 0.3; β = 0.2; γ = 0.1 and 0.35 in the low- and high-capacity levels, respectively; = 0.8 and 1.6; σ= 0.6; a = 0.25; b = 0.3; c = 0.15; = 0.05 and 0.2; and d = 0.2. 7For example, if the recipient government plans to obtain more project aid and food inflows, this can reduce public investment and govern- ment consumption. If the reduction in public investment outweighs the decline in government consumption, growth rates can fall. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. ME  P. SANYAL, S. C. BABU ME 572 g 0 Copyright © Sci 2012 0 Res. rate of output. The rate of capital accumulation also in- creases with greater output growth, which leads to a shift of the K locus from 1 to 0g . Thus, an exoge- nous increase in learning leads to an increase in the long- term capacity, technology, capital stock, and output. to greater technology absorption, resulting in resources being efficiently used in the goods-producing sector. This shifts the K 4.2. Doubling of Capacity Resources When the Elasticity of Output with Respect to Capacity Is Low In this case, we assume the parameter value of γ to be equal to 0.1. We consider the following experiment of doubling of capacity resources i.e., increasing from 0.8 to 1.6. The capacity of the recipient country is low in this situation. As shown in Figure 2, for the same level of α, an increase in recipient country resources devoted to ca- pacity leads to greater learning and knowledge interact- tions among agents in the economy, which leads to greater human capital accumulation. The increase in human capital accumulation also leads 0 locus from 1 to 0g . For the same level of technology intensity (σ) in the R&D sector, because the domestic level of capacity is low, a signify- cant increase in capacity resources also leads to greater human and physical capital accumulation. Thus, the slope of the A locus becomes flatter, and the economy slowly converges over time from point E0 to E1. As a consequence, there is a significant increase in capacity, capital stock, technology, and output. The impact can also be understood by considering the steady-state condition for the growth rate of capacity10. Because the elasticity of output with respect to capacity (γ) is extremely low, an increase in leads to greater human capital accumulation, higher growth rates of technology, and a higher rate of capital accumulation. All of this contributes to a signify- cant increase in the growth rate of capacity, leading to higher economic growth. A ( = 0) 1 ( =0) 0 E 1 E 0 ( A = 0) 1 A *1 A *0 *0 *1 ( A = 0) 0 Figure 1. Effects of an increase in the rate of learning in the economy. 10This condition can be stated as follows: *** 1 22 2 CKK A mg gn .  P. SANYAL, S. C. BABU 573 ( A =0)0 A ( A =0)1 ( A =0)0 E1 E0 ( A =0)1 A *1 A *0 *0 *1 Figure 2. Donor intervention when capacity of the economy is low. 4.3. Donor Intervention When Elasticity of Output with Respect to Capacity Is High We now consider the final case, in which the elasticity of output with respect to capacity is moderately high, i.e., γ = 0.35. We consider the same experiment as before—of doubling of capacity resources by the recipient country’s government. Because the economy’s capacity is already quite high, the recipient government needs to coordinate the activities in a more effective and efficient way, rather than depending on more donor resources. The following is what happens in this case: Initially, the economy is at point E0. Because the economy is already at quite a high capacity, an increase in donor intervention without any preplanning and coordination leads to a decline in both the human capital stock and the accumulation of tech- nology. This leads to resources being inefficiently used with the consequence that capital stock is depleted sig- nificantly, as shown by the locus in Figure 3. 1 0g 0 K g K At the same time, an increase in donor intervention with multiple projects leads to a decline in the technol- ogy sector. This can be coined as the “crowding-out ef- fect” of donors driving the recipient government out of projects and programs. Although the decline in the tech- nology sector is not as significant as in the commodity sector, it is still negatively sloped and flatter than the 0g 0g locus. In other words, the A locus and the K locus do not intersect, with the consequence that the economy never reaches a new steady state. 4.4. Implications for Donor Agencies As pointed out by [20], the impact of development aid on growth shows a positive but insignificant effect, while Copyright © 2012 SciRes. ME  P. SANYAL, S. C. BABU 574 ( =0) 1 ( =0) 0 A ( A =0) 1 ( A =0) 0 E 0 g g Figure 3. Donor intervention when capacity of the economy is high. studies of the effect on growth that is conditional on ei- ther good policy or development aid itself have shown weak results. For example, [12] noted that “aid is more effective in fostering growth and improving service de- livery in countries with better policies and institutions. It is also more effective when it is aligned with recipients’ priorities, when it reduces transaction costs through har- monized and coordinated donor processes, when it is predictable, and when there is a clear focus on results.” Our result blends the above findings and indirectly implies that development aid should be conditional on a country’s level of capacity for it to be more effective. Under this framework, a country’s level of capacity should be the primary criterion for eligibility for substantial aid. We thus propose an S model of aid effectiveness on the lines of [21], where country ownership and need (high poverty rates) determine the level of development aid. The first segment of Figure 4 covers the pre-reform stage, where country ownership is really low and the state itself may be failing. The level of human resources at this stage is very low in part because a significant portion of the population is illiterate or barely has a primary educa- tion, institutions may be failing, and there are virtually no public or private sector organizations. Under these condi- tions, the recipient country would first need to develop its own strategy, programs, and projects in consultation with both its own constituencies and donor agencies. It would then present its plans to the donors, who would put unrestricted and untied financing into a common pool. The level of aid would be low at this stage and would come mainly in the form of technical assistance, policy advice, or grants [22]. Donors should support the efforts of the recipient countries and actively support reformers and visionary leaders. The first-stage reforms should consist of human re- source development, accompanied with better public sector Copyright © 2012 SciRes. ME  P. SANYAL, S. C. BABU 575 Figure 4. Relationship between aid effectiveness and country capacity. management. These reforms are important, as the recipe- ent country’s monetary need is high, and aid effective- ness is increasing. This learning can be conducive to rais- ing productivity in the public sector. This situation is demonstrated in Figure 2, in which development aid has high and positive marginal returns. Both the donor’s and the country’s own resources can be allocated to high-pr- iority areas to generate higher economic growth and de- velopment effectiveness. The second-stage reforms should emphasize building new institutions and restoring existing ones. At this stage, aid intensity needs to be maintained or even increased, as the effectiveness is very high. In addition, donors can improve on development outcomes by creating effective links between civil society organizations (such as NGOs) and other partners. Because these civil society organiza- tions have links both up and down the ladder of interact- tion, the countries effective capacity can be strengthened. Donors can provide their expertise on public sector man- agement to NGOs in order to facilitate activities and im- prove upon development effectiveness. The final stage (the post-reform period) occurs when a country owns its policies and programs. This stage is demonstrated in Figure 3, in which diminishing marginal returns to aid set in and other sources of investment be- come the dominant form of financing. Because this stage is characterized by an improved organizational structure of public sector institutions, a strong supply of profess- sional and technical personnel, and the presence of strong institutions, donors are better off by letting recipient coun- tries own their own policies and programs. At this stage, donors should develop exit strategies to minimize the disruptions of transition and to smooth the way for new capacity-building initiatives. There will be substantial revamping of the international aid architecture under the above arrangements. Donor agencies (both bilateral and multilateral) will still play a critical role, but their ownership of policies and the pro- grams of recipient countries will be substantially dimin- ished. Donors will learn from their past mistakes and change their ways of managing aid and improving coun- try ownership of policies and programs. They may help organize knowledge management, assist in operation of public sector organizations, and support civil society organizations for improved reforms in judiciary and legal systems. Although development aid can be justified dur- ing the first and second stages of reform for improving country capacity, less aid will be necessary in future stages. The interaction between development aid and learning by recipient countries is important and should be cultivated in a manner that promotes country and institutional ca- pacity building instead of the capacity erosion that is evident in many sub-Saharan African countries at present. 5. Summary and Conclusions Resources devoted to capacity strengthening remain a major challenge in many developing countries, and accounting for them can provide some additional insights about de- velopment processes. This is important because excessive donor interventions in multifarious projects and programs have often been in direct conflict with recipient country policies and objectives. The novelty of this paper is to consider capacity not only as a resource that is used to produce goods and ser- vices and to generate new technologies, but also to em- phasize its role in improving economy wide learning outcomes, which eventually influences the innovation performance of an economy. Although the literature has strongly emphasized how capacity is formed, a theoretic- cal perspective of its role in development outcomes has not yet been demonstrated. We consider capacity to be an endogenous process that is not only generated by country governments, but also strongly related to learning. We Copyright © 2012 SciRes. ME  P. SANYAL, S. C. BABU 576 show that in the steady state, the growth rate of capacity is critically dependent on the learning parameter, the elasticity of output with respect to capacity resources, and how the resources are utilized by the recipient coun- try with the help of donor funds. We demonstrate that for the recipient country’s capacity to be maintained over time, there exists a critical value of utilized resources from donor funds that needs to be de- voted for capacity strengthening. However, if the actual value exceeds this critical value, the country’s capacity will decline over time, affecting the long-run growth rate of the economy. Undertaking some of the policy exercises, we first found that increasing learning capabilities in an economy raises the human capital stock and unambiguously increases the rates of growth of output, technology, capital stock, and capacity. Second, a donor’s intervention is most desirable when country capacity is low. In this case, an increase in resources utilized efficiently by the recipient country has substantial effects on the growth rate of output, technol- ogy, and capacity. Finally, if the country’s domestic capacity is moderately high, excessive donor intervention can actually lead to crowding-out effects, in which the economy never reaches a new steady state. The consequence is that the rate of growth of technology, output, and capacity will continu- ously decline. Under such situations, donor projects will only be relevant if they fit into the recipient countries’ policies and objectives. Our results have indirect implications for donor agen- cies—based on the level and stage of a country’s owner- ship of policies and programs. During the pre-reform stage, when the level of ownership of policies and programs is very low, the level of aid should be low and should come mainly in the form of technical assistance, grants, or pol- icy advice. During the first and second stages of reform, aid should increase to address human resource develop- ment, better public sector and organizational manage- ment, and enhancement of the institutional capacity of the recipient country. However, during the post-reform period, the need for development aid diminishes substan- tially. Donors are better off developing an exit strategy to let recipient countries own their policies and programs. REFERENCES [1] Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), “Capacity Development: Why, What and How,” CIDA Pol- icy Branch, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2000, pp. 1-8. [2] Organization for Economic Cooperation and Develop- ment (OECD), “The Challenge of Capacity Development: Working towards Good Practice (DAC Network on Gov- ernance),” OECD, Paris, 2006. [3] P. Morgan, “Capacity and Capacity Development: Some Strategies,” CIDA Policy Branch, Gatineau, 1998. [4] P. Morgan, “The Idea and Practice of Systems Thinking and Their Relevance for Capacity Development,” Euro- pean Centre for Development Policy Management (ECDPM), 2005. http://lencd.com/data/docs/118-The%20idea%20and%20 pra-tice%20of%20systems%20thinking%20and%20their %20rele.pdf [5] C. Gunnarson, “Capacity Building, Institutional Crisis and the Issue of Recurrent Costs: Synthesis Report,” Almkvist & Wiksell International, Stockholm, 2001. [6] S. Choritz, “Literature Review of Evaluative Evidence on the Three Drivers of Effective Development: Ownership, Policy and Capacity Development,” United Nations De- velopment Programme (UNDP), New York, 2002. [7] E. J. Berg, “Rethinking Technical Cooperation: Reforms for Capacity Building in Africa,” United Nations, New York, 1993. [8] M. S. Grindle and M. Hilderbrand, “Building Sustainable Capacity in the Public Sector: What Can be Done?” Pub- lic Administration and Development, Vol. 15, No. 5, 1995, pp. 441-463. doi:10.1002/pad.4230150502 [9] S. Fukuda-Parr, “UNDP Human Development Report 2003,” Oxford University Press, New York, 2003. [10] J. J. Dethier, “Aid Effectiveness: What Can We Know? What should We Do? What May We Hope?” Paper pre- sented at the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Washington DC, 2008. [11] World Bank, “Global Monitoring Report,” World Bank, Washington DC, 2007. [12] World Bank, “Capacity Building in Africa: An OED Evaluation of World Bank Support,” World Bank, Wash- ington DC, 2005. [13] M. Wubneh, “Building Capacity in Africa: The Impact of Institutional, Policy and Resource Factors,” African De- velopment Review, Vol. 15, No. 2-3, 2003, pp. 165-198. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8268.2003.00070.x [14] P. M. Romer, “Endogenous Technological Change,” Jour- nal of Political Economy, Vol. 98, No. 5, 1990, pp. S71- S102. doi:10.1086/261725 [15] D. H. C. Chen and H. L. Kee, “A Model on Knowledge and Endogenous Growth,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 3539, March 2005. [16] Y. Feng, J. Kugler and P. J. Zak, “The Politics of Fertility and Economic Development,” International Studies Quar- terly, Vol. 44, No. 4, 2000, pp. 667-693. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00176 [17] G. Mavrotas, “Which Types of Aid Have the Most Im- pact,” UNU-WIDER Working Paper No. 2003/85, De- cember 2003. [18] E. L. Glaeser, D. I. Laibson and B. I. Sacerdote, “The Economic Approach to Social Capital,” Economic Jour- nal, Vol. 112, No. 483, 2002, pp. F437-F458. doi:10.1111/1468-0297.00078 [19] M. Nkusu, “Aid and the Dutch Disease in Low-Income Countries: Informed Diagnoses for Prudent Prognoses,” International Monetary Fund (IMF) Working Paper No. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. ME  P. SANYAL, S. C. BABU Copyright © 2012 SciRes. ME 577 04/49, Washington DC, 2004. [20] H. Doucouliagos and M. Paldam, “The Aid Effectiveness Literature: The Sad Result of 40 Years of Research,” Uni- versity of Aarhus Working Paper No. 2005-15, Aarhus, October 2007. [21] B. Abegaz, “Multilateral Development Aid for Africa,” Economic Systems, Vol. 29, No. 4, 2005, pp. 433-454. doi:10.1016/j.ecosys.2005.06.005 [22] S. Devarajan, D. R. Dollar and T. Holmgren, “Aid and Reform in Africa,” World Bank, Washington DC, 2001.

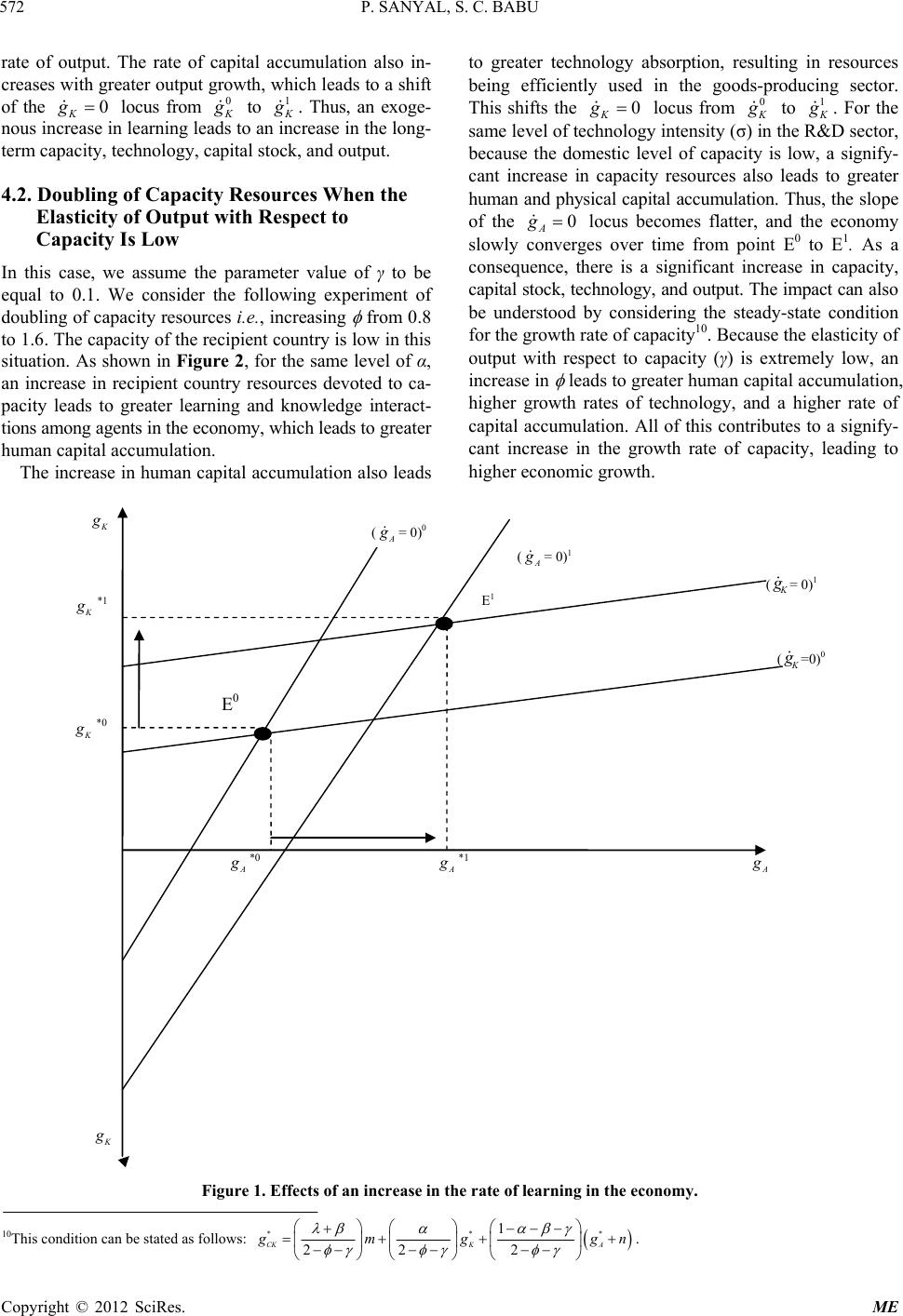

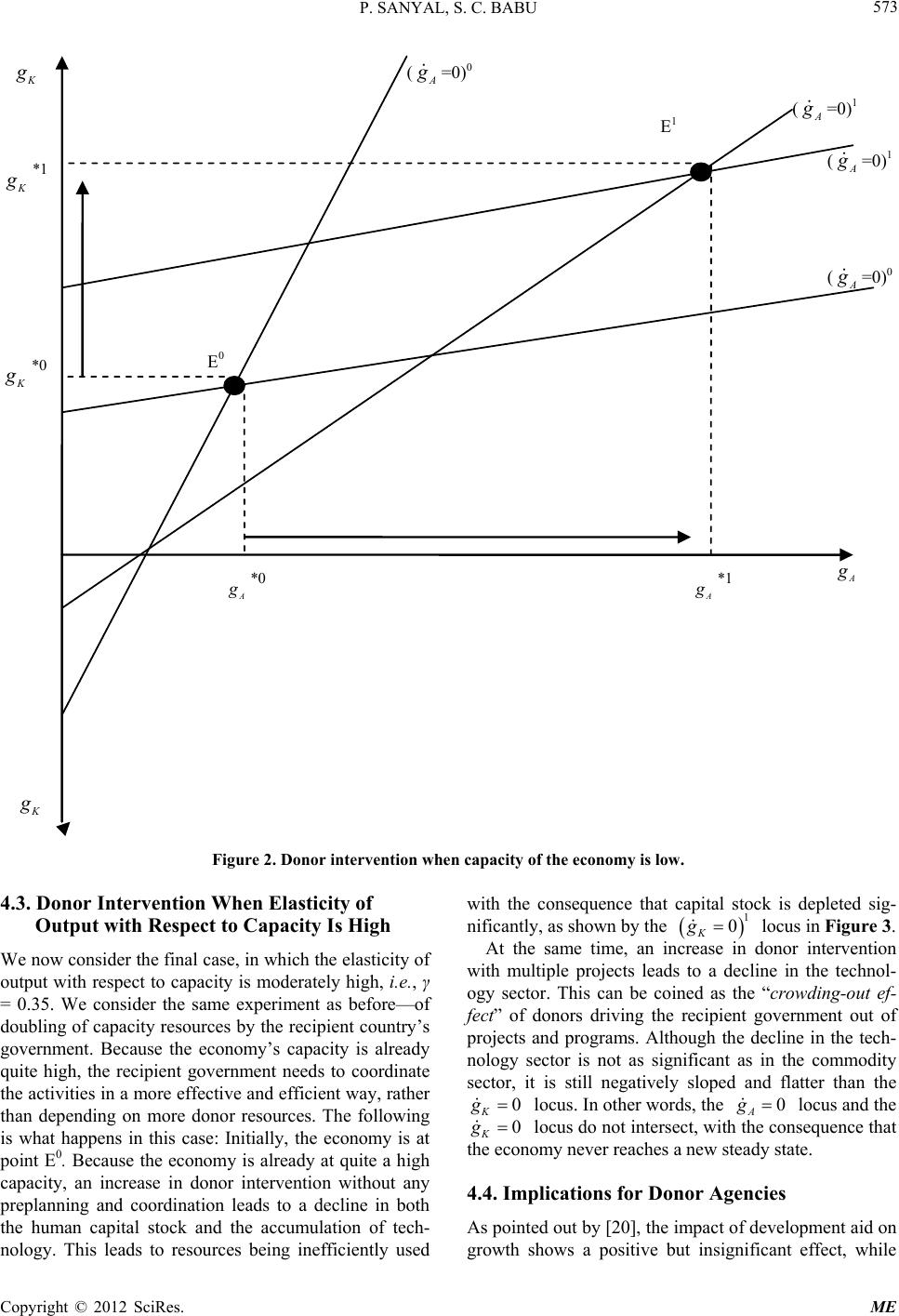

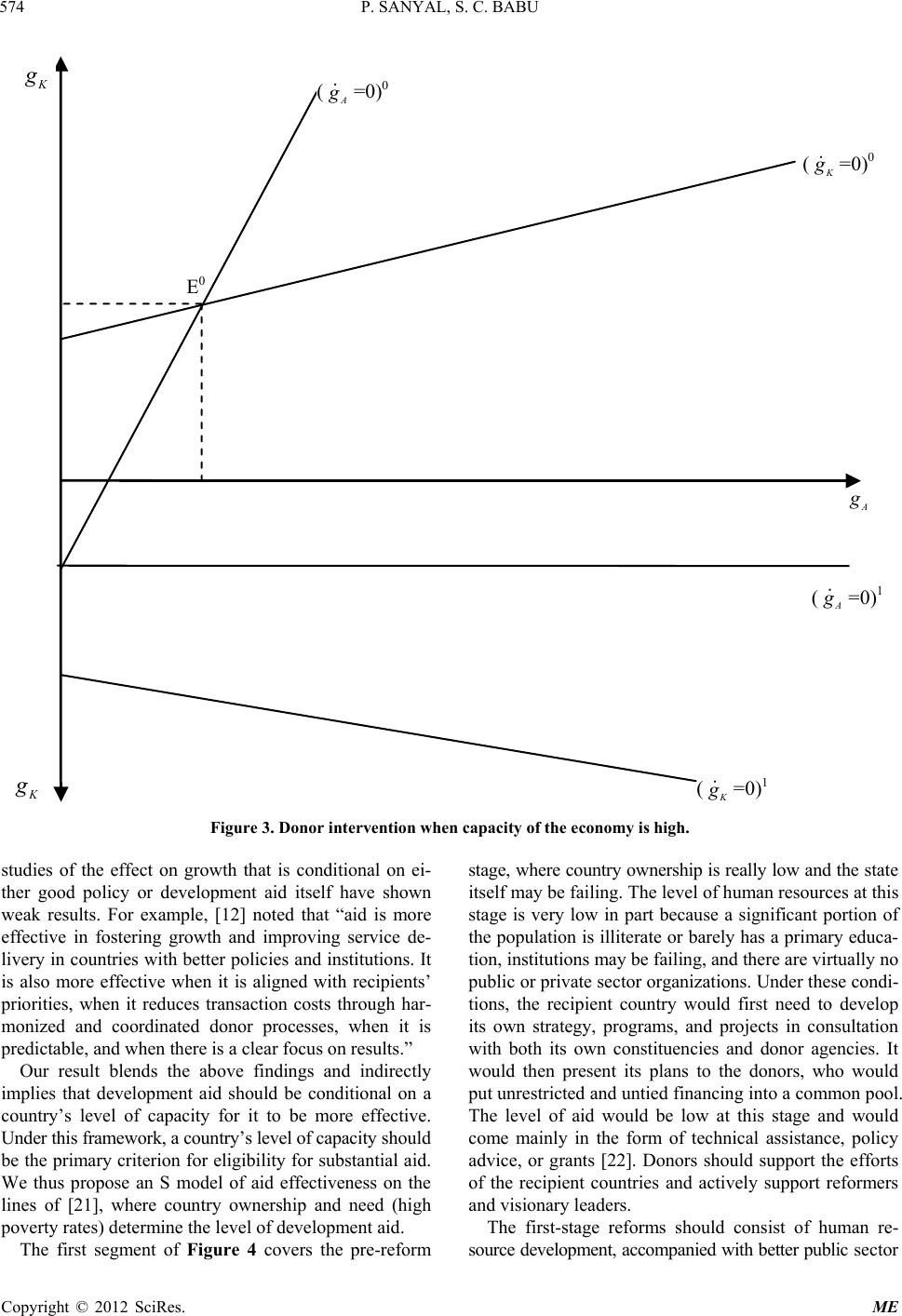

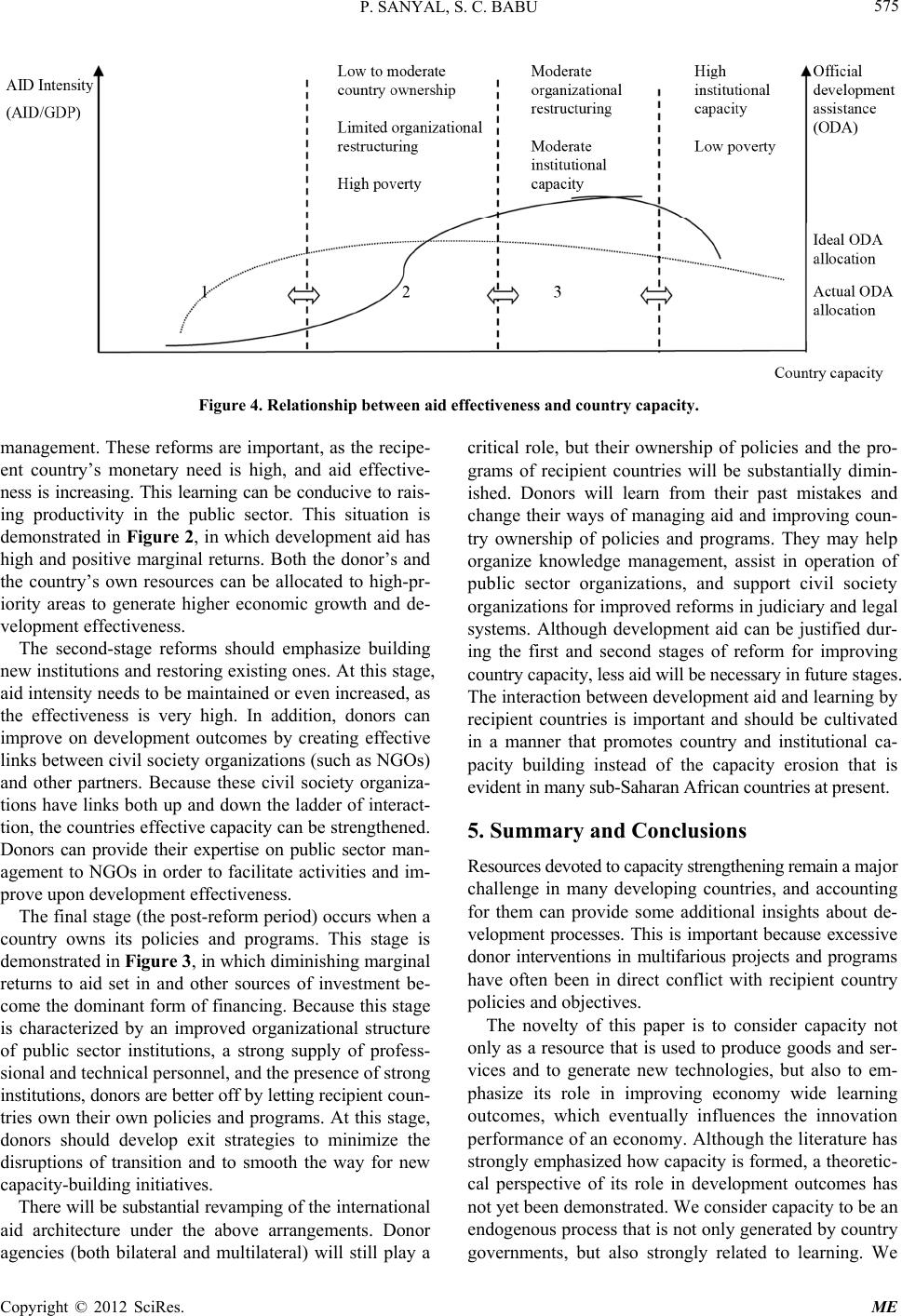

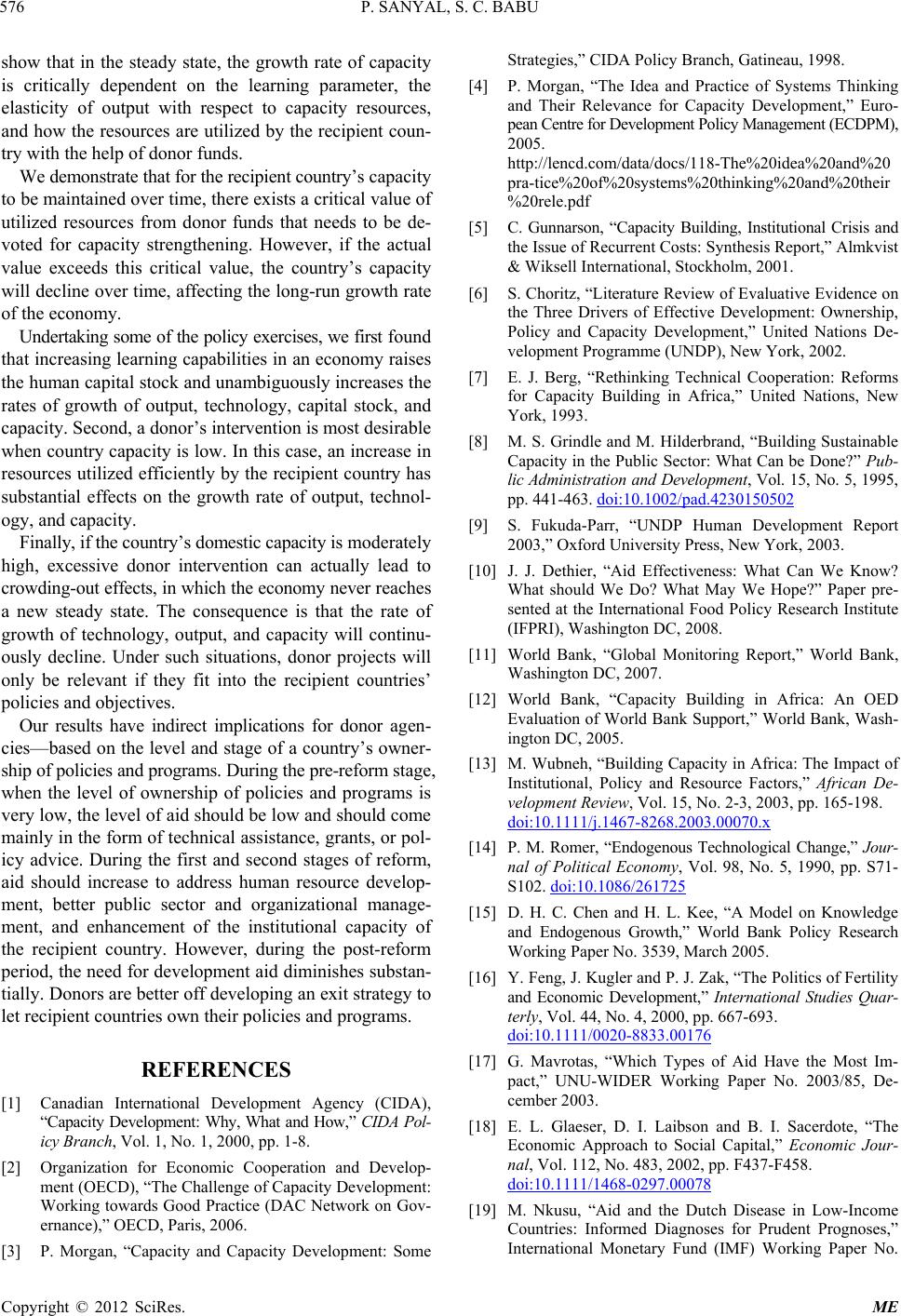

|