Modern Economy, 2012, 3, 526-533 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/me.2012.35069 Published Online September 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/me) A Simple Trade Model with an Optimal Exchange Rate Motivated by Discussion of a Renminbi Float* Hui Huang1, Yiming Wang2, Joh n Whalley3, Shunming Zhang4 1Faculty of Business Administration, The University of Regina, Regina, Canada 2Department of Finance, School of Economics, Peking University, Beijing, China 3Department of Economics, Social Science Centre, The University of Western Ontario, London, Canada 4China Financial Policy Research Center, School of Finance, Renmin University of China, Beijing, China Email: hui.huang@uregina.ca, wymecon@126.com, jwhalley@uwo.ca, szhang@ruc.edu.cn, shunming.zhang@gmail.com Received March 22, 2012; revised April 25, 2012; accepted May 8, 2012 ABSTRACT We present a model of combined inter-sp atial and inter-temporal trade between countries in which there is a fixed ex- change rate with a surrender requirement for foreign exchange generated by exports. The model incorporates inter- temporal intermediation services, which may or may not be liberlized across countries. We use numerical simulation methods to explore the properties of the model, since it has no closed form solution. In this model, when services re- main unliberalized there is an optimal trade intervention, even in the small open price taking economy case. Given monetary policy and an endogenously determined premium value on foreign exchange, an optimal setting of the ex- change rate can provide the opti mal trade intervention. We suggest th is model may have loose relevance for the current situation in China where services remain unliberalized and tar iff rates are bound in the WTO and a free Renminbi float is under discussion. Keywords: Fixed Exchange Rate; Foreign Exchange Premium; Services; JEL Classification: F00; F02; F31; F32 1. Introduction This paper takes as its point of departure macro literature on the choice of exchange rate regime. While the choice between a fixed and flexible exchange rate regime has long been argued and debated in classical monetarist t erms (that a fixed exchange rate implies accommodating mone- tary policy, and monetary policy determines the floating rate) as in Friedman’s [1] discussion, there is little litera- ture that suggests t hat there may exi st an opt imal exchange rate which dominates a free float1. We use a model of combined inter-spatial and inter- temporal trade between countries in which there is a fix ed exchange rate accompanied by a surrender requirement for foreign ex change g enerated by expor ters. Huang, Whal- ley and Zhang [4] earlier analyzed the merits of trade liberalizatio n i n finan cial services using a related appr oach both with no treatment of the exchange rate require. In their model, in the presen ce of tariffs o n inter-spati al t ra de free trade in services, even for a small open price taking economy, may not be welfare improving, and free trade in goods may not be Pareto optimal if services trade re- mains unliberalized. In the model presented here, under either auctioning of foreign exchange received by the central bank among im- porters, or some non auctioned foreign exchange alloca- tion mechanism with domestic trading in foreign exchange, there will be a premium value on foreign exchange which is endogenously determined and operates akin to a tariff on imports. In simple models where income effects among consumers are assumed away, domestic monetary policy in such a model is non neutral, while trade liberalization (a tariff reduction) merely changes the premium value on foreign exchange, leaving trade unchanged. Since mone- tary policy is n on-neu tral, when services re main unlibe ra l- ized there is an optimal trade intervention, even in the small economy case. This occurs because given monetary 1Such a contention is relevant to current policy debate in China, since with an optimal exchange rate a freely floating rate may be welfare worsening. China has long maintained a fixed exchange rate with tight regulation of domestic banks, and strict limits on entry to the Chinese market for foreign financial institutions. In past, this has reflected a desire for macro stability, but the Chinese banking system also differs sharply from those in OECD countries with small but growing personal banking, and state owned banks acting in part as mechanisms for recapit- alizing loss making state owned enterprises. Thus, much of what is at state in the debate on financial liberalization in China and the choice o exchange rate regime is the form and operation of the Chinese banking system and how this would change with a freely floating fully conve- rt ib le Ren minbi and this goes well beyond the discus sion here (se e Z ha ng and Pan [2] and Chang and S h ao [3]). *This work is supported form National Natural Science Foundation o China (NSFC Grant: 70825003) and National Social Science Found- ation of China (SSFC Grant: 07AJL002). C opyright © 2012 SciRes. ME  H. HUANG ET AL. 527 policy and an endogenously determined premium value on foreign exchange, an optimal setting of the exchange rate can provide the optimal trade intervention. Under a freely floating exchange rate any departure from this optimal rate will typically inflict welfare losses. In a two country model, a retaliatory exchange rate game, related to well known tariff games can be constructed, fo r which a Nash equilibrium in exchange rates can be computed. We present the model, and illustrate possib le outcomes using numerical simulation, and discuss its relevance to the contempor ar y Ch ines e s itua tion wher e serv ice s ar e unl i- beralized and tariffs are bound in the WTO. We would not pretend that th is model realistical ly cap tu res all of th e relevant features of the financial and real sides of the Ch i- nese economy, and hence may only be suggestive in its implications for current policy. Importantly, there is no foreign exchange premium in China since China is cur- rentl y runn ing a trad e surp lus ra ther th an th e balan ced trade our model specifies, and concerns over potential capital flight under a free float are the most important factor in current debates and they are not captured here. But the implication that if services remain largely unliberalized (as in China today) and tariff rates are bound in the WTO a move to a free float may be welfare worsening in our analysis seems both clear and relevant, and should be kep t in mind by those currently advocating a free Renminbi float. 2. A Model of Spatial and Inter-Temporal Trade with a Fixed Exchange Rate and Non-Neutral Monetary Policy We consider a world in which two types of trade are pos- sible. One is inter-spatial trade between countries in com- modities, and the other inter-tempor al trade facilitated by providers of intermediation services. To simplify things, we further assume tha t intermediation serv ices, when t hey are provided, are supplied at zero cost to users of services, and also that such services can only be provided by for- eign service providers. This gross simplification implies that all intertemporal trade implies international trade in intermediation services, but adopting it means that we can consider autarky in services to be a case where no inter- temporal intermediatio n occu rs, and free trade in services to be the case where full inter-temporal intermediation occurs. If services remain unliberalized budget constraints within each period hold when we consider changes in exogenous variable (such as fixed exchange rates) in the model. We do not claim that this is a realistic representa- tion of how service sectors operate in actual economies, but it is a useful analytical si mplification. We assume a fixed exchange rate regime with result- ing monetary non-neutralities. We assume domestic cur- rency is needed to execute domestic transactions while foreign currency is both needed for purchases of imports and yielded by the sale of exports. We only consider the transaction demand for money and in our formulation all foreign exchang e earni ngs of expor ter s are su rrend ere d to the central bank at the fixed exchange rate, while foreign exchange received by the bank is auctioned among im- porters at a premium to the official exchange rate. This premium value is endogenously determined given mone- tary policy, and operates akin to a tariff. (Also see Clarete and Whalley [5]). For simplicity, we consider the 2 period (t = 0, 1), 1 country, 2 good (l = 1, 2) pure exchange international trade case of a small open price taking economy. Adding additional features such as produc tion, or more periods or goods, merely complicates the analysis while the themes remain the same. The model can be presented as follows. The country has a single representative consumer, with endowments of the two goods in each period (l; t = 0, 1, l = 1, 2), and inter-temporal preferences written as t E 1 12 =0 000 111 12 12 1 =, 1 1 =, , 1 ttt t t UuXX uXX uXX t l (1) where ρ is inter-temporal discount factor and de- notes consumption of good l at date t. If a time-additive Cobb-Douglas utility fu nction of the form 12 12 12 ,= tt tttt t uXXX X for t = 0, 1 is used, (1) can be represented more explicitly as 00 11 12 12 00 11 12 12 1 =1 UXXX X t l (2) is the share parameter for good l at date t where 2=1 t t =1 l l For good l in each period t, the exogenous world price is l . We can also consider CES preferences. . We allow the country to impose tariffs at rate l on each imported good l (i.e. if ll t T tt E0T tt , then t l). Tariffs are set to equal zero if good l is exported (i.e. if ll E , then l0 t T ). Internal (gross of tariff) prices for good l at date t are thus =1 ,=0,1,=1,2 tt t lll PTtl 2 =1 =,=0,1 ttttt ll ll l RTXEt t E 2 =1 =,=0,1 tttt ll l IPERt . (3) These are also sellers prices of good l. Tariff revenues collected in period t are (4) where l denotes the initial endowment of good l. In- come in period t is given by . (5) Copyright © 2012 SciRes. ME  H. HUANG ET AL. 528 We consider the case in which both goods are traded, and there is both a fixed exchange rate and rationed for- eign exchange. We assume that the government fixes the exchange rate at et, and requires all foreign exchange earned by exporters to be surrendered to the Central Ba nk at the rate et. It then allocates rights to purchase available foreign exchange to importers at the same rate et. We will assume that exporters comply with this policy and fully meet the surrender requirement, even though there are ob- vious incentives for exporters to conceal foreign exchan ge and attempt to sell it on parallel (black) markets rather than surrender it at the lower fixed rate. The allocation process of foreign exchange among importers assumes that the government auctions (or sells) foreign exchange. In practice, allocation schemes actually followed are mor e complex than this involving priority allocation of various forms, but we abstract from these. But under such a sim- ple auctioning scheme, if desired imports require more foreign exchange than the government offers for sale, th e price of foreign exchange paid by importers will be bid up. This price will thus include a foreign exchange pre- mium above the fixed rate et, which we designate as λt. This premium acts as a surcharge on foreign exchange bought by importers, and adjusts so as to clear the for- eign exchange market. In this formulation the net effect of foreign exchange rationing is similar to a tariff on all imports, since the ex- change rate received by exporters differs from the gross of premium value exchange rate paid by importers. The difference from a tariff is that the premium rate (or tariff equivalent rate) is endogenously determined. Also, under an auctioning scheme, the foreign exchange premium ac- crues to the government, but if rights to purchase foreign exchange at the rate et were instead allocated by the gov- ernment without charge, the premium would instead go directly to importers. The world prices for the 2 goods are given as l t for t = 0, 1 and l = 1, 2. Domestic prices (gross of tariff and gross of the foreign exchange premium for imports) for the 2 goods are again denoted as for t = 0, 1 and l = 1, 2, and are defi ned belo w b y (7). t l P Assuming unitary velocity of circulation and that the only demand for money is for transaction purposes, the demand for domestic currency t at date t is given by the value of domestic demands in domestic currency, i.e. 2 =1 tt Dl l MP =,=0,1 t l Xt t (6) Implicitly, we assume that imports are bought by mid- dle men (imports) using foreign currency, who then im- port costlessly and sell imports at domestic prices. The s up - ply of domestic currency at date t is assumed to be set by the domestic monetary authorities and is given by S . Because of the foreign exchange premium, relative do- mestic prices of the 2 traded goods will now differ from world prices both due to the premium on foreign exchange and the tariff, depending upon whether the good is im- ported or exported. Domestic prices l gross of the for- eign exchange premium are thus now given by t P ,0 =1, >0 ttt t lll t ltttt t lll eifXW PeifXW tt (7) where ll W t denotes the net import of goods l, and λt is the premiu m value over the officia l exchang e rate paid by purchasers of imports. The demand for foreign currency N 2 =1 =,=0,1. tttt Dlll l NXWt t N 2 =1 =,=0,1. tttt Slll l NXWt = tt at date t is given by the value of imports at world prices (8) The supply of foreign currency S at date t is given by the value of exports at world prices (9) We consider two types of equilibrium. One of these is characterized by no provision of intermediation services by foreign services providers, and since we assume them to be the on ly po tent ial se rvic e provid ers, no inte r-te m pora l intermediation. In this equilibrium, period by period b u d g et constraints apply for the economy, and we associate such an equilibrium with autarky in services trade. The other type of equilibrium is characterized by costless interna- tional flows of intermediation services (or free trade in s er - vices), and in this case combined period by period budget constraints hold. The only role for foreign services pro- viders in the model is to costlessly facilitate intermedia- tion within the price taking economy. If there is no trade in intermediation services trade bal- ance holds in each period, which implies that the value of imports goods is equal to the value of export and hence S NN 2 =1 =0. tt t ll l l XW 2 =1 =,=0,1 ttt tt t ll l l ReXW t for t = 0, 1. Trade balance implies that (10) which also implies that total revenues accruing to sellers of rights to purchase foreign exchange at the rate et are (11) These revenues accrue either directly to the household sector as additional income of importers who are given allocations of foreign exchange by the government which they resell on premium markets, or indirectly as recycled government reve nu e s . Be cause anti cipated revenues Lt from rights of access to foreign exchange affect commodity de- mands and are a component of income for at least one of Copyright © 2012 SciRes. ME  H. HUANG ET AL. 529 the agents in the model, market demand functions have to be rewrit ten to reflect this. Bo th Lt and Rt are each e nd og e- nously determined , a nd Lt = Rt only in equilibrium. The budget constraint for the household sector in this case includes initial holdings of money balances, and is given by 2 =1 = ttt llS l IPWM ,=0,1 tt Lt =, =0,1 t I t =,=0,1 t L t =0, tt RL , tt L 0,1;=1,2l 22 ..=, =0,1 ttttttt st P XMPWMLt 2 =1 =0 =0 =0 tttt ll l l ttt t DS eXWand RLandM M = tt (12) 2.1. General Equilibrium with Service Trade Autarky (Period by Period Budget Constraints) When there is service trade autarky no intermed iation ser- vices are provided since by assumption there are no do- mestic service providers2. This means that there is incom- pleteness in the coverage of markets in the sense that in service trade autarky intertemporal markets are missing. This enables us to appeal directly to literature on multi- commodity inter-temporal models of incomplete markets due to Radner [10], Hart [11], Duffie and Shafer [12], Werner [13], Duffie [14], Geanakopolos [15], Magill and Shafer [16], and Magill and Quinzii [17] in analyzing the effects of service liberalization in this model. In services trade autarky there is no inter-temporal trade, while with costless inter-temporal trade in services inter-temporal markets are complete. We use incomplete markets litera- ture without the added complication of uncertainty; most of this literature is concerned with existence issues; our focus here is comparative statics. In the absence of trade in financial intermediation ser- vices the total value of expenditures must satisfy the household budget constraint in each period, i.e., 2 =1 tt t llD l PX M (13) that is, 22 =1 =1 tt ttt t ll DllS ll PX MPWM (14) or 2 =1 =0 ,1 ttttt t ll lDS l eXWMM t (15) A single country equilibrium in this case is given by values of which satisfy the conditions: 1) solves := t l Xt maxU =1 =1 ll Dll S ll (16) 2) For t = 0, 1, trade balance, premium revenue bal- ance, and money demand and supply equalities hold in each period. (17) 2) Implies that S NN for t = 0, 1. 2.2. General Equilibrium with Free Trade in Services (Across Period Budget Constraints) If costlessly provided foreign supplied intermediation ser- vices are allowed in the model, then we can characterize a free trade in services equilibrium as a case where ac ros s period budget constraints hold rather than period by pe- riod budget constraints. In this model form, we assume the interest rate r is endogenously determined on the country capital market to clear demand for and supply of loans. The economy is then only a price taker in goods markets, and foreign financial intermediaries only prov ide their services to the single country. In this case, the demand for foreign currency is 1 =0 =1 t D Dt t N N r . The supply of for eign currency is 1 =0 =1 t S St t N N r = . Trade balance now implies that the value of imports equals the value of exports and S NN , i.e. 12 =0 =1 22 00011 1 =1 =1 1 1 1 ==0. 1 tt t ll l t tl lllll l ll XW r XW XW r 20000 =1 2111 1 =1 = =1 ll D l ll D l PXMFI PXMIr F 22 00 000 00 =1 =1 22 11 111 11 =1 =1 = =1 ll DllS ll ll DllS ll PX MFPW M L PXMPWMLr F (18) With trading now allowed across the 2 periods under liberalized trade in financial intermediation services, the total value of expenditures satisfy the household budget constraint in each period, including borrowing and lend- ing across periods, i.e., (19) where following the literature on incomplete markets F is the amount of credit extended across periods by foreign finance service providers. (19) can be rewritten as (20) 2See the discussion of barriers to trade in intermediation services in ractice in Chen and Schembri [6], Francois and Schuknecht [7], Ka- lirajan, McHuire, Nguyen and Schuele [8], and Mattoo [9]. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. ME  H. HUANG ET AL. 530 or 2 00000 00 =1 2 11111 11 =1 ll lDS l ll lD S l eXWMM eXWMMR 0 1 =0 =1 RLF L rF (21) or 22 0000 1 =1 =1 1 1 =0 lll ll DS eXW e r MM RL 111 ll l XW (22) where 01 1 1 = DD MM r is the value of demands in present value terms for domestic currency, 01 1 1 SS S = MM r is the value of supply in present value terms for domestic currency, 01 1 1 RR R r = are the revenues across periods accruing to sellers of rights to purchase foreign exchange, and 01 1 =1 LL L r are anticipated revenues across periods distributed to con- sumers from auctioned foreign exchange. A simple country equilibrium in this case is given by values of which satisfy the conditions: ,,, tt LFr 0,1;=1,2l 000 11 l S M L LrF 1) solve :=Xt axmU t l 22 00 00 =1 =1 22 11 111 1 =1 =1 .. = = ll Dl ll ll DllS ll st PXMFP W PX MPW M (23) and 2) 12 =0 =1 1=0, 1 =0 =0,1 tttt ll l t tl tt DS eX WR r MM fort =0L and (24) 2) In this case implies 1 =0 1 =1 =0 1 11 tt S t t NN rr t t . In this model, goods flows and intermediation services interact as follows. With liberalized service flows there is intertemporal in- termediation and more specialization in consumption by period and hence more international trade. For given monetary policy and a given fixed exchange rate, liber- alized service flows result in a higher value of and hence more severely distorted goods trade internationally. If al- ternatively, the fixed exchange r ate is r a ised, then there is less distortion of trade but the unliberalized service trade implies that gains from intertemporal intermediation go unrealized. The first best policy combination is for liber- alized services trade and a floating exchange rate. But if services trade remains unliberalized there is an optimal trade intervention even for a small open economy. In the case where per iod by period budget con straints apply, t h er e will be an optimal trade intervention and, for given mone - tary policy, an optimal exchange rate. If instead across period budget constraints apply (with free trade in ser- vices) there will be no optimal exchange rate. The impli- cation is that if tariffs are bound under WTO/GATT and services remain unliberalized (as in China) either mone- tary or exchange rate policy provide instruments for achiev- ing the optimal trade intervention. If monetary policy is given, an optimal exchange rate will exist, and any dep ar- ture from this via a free float will impose welfare losses. The possibility of such outcomes in the model can be ex- plored by numerical simulation in which fixed exchange rates are parametrically varied. 3. Some Numerical Simulation Results Indicating an Optimal Exchange Rate We have used numerical simulation to explore whether in the presence of given monetary policy (money supply fixed in each period), bound tariffs on goods traded in- ternationally (assumed to be zero), and service trade re- maining unliberalized there can be an optimal exchange rate. Depending on where any given exchange rate is r el a- tive to the optimal exchange rate,losses or gains can oc- cur with a move to a free float. If the initial fixed exchange rate is by chance equal to the optimal exchange rate, losses must necessarily occur. The size of the effects involved depend critically on the numerical example chosen, and in Table 1 we pro- vide a sample parameterization for a model with Cobb Douglus in which the combination of fixed exchange r at e s and domestic money supply imply lpremium values on f o r - eign exchange and hence distortion of goods trade, we also consider a case with different preferences across periods, so that gains from intertemporal intermediation will also occur. To simplify, world prices are unity, as are fixed exchange rate. We have used the structure set out in Section 2 to per- form some numerical simulations for a simple economy which show how in the presence of given monetary pol- icy (in the form of a setting of the money supply), WTO bound tariffs on goods flows, and service trade remaining unliberalized, there will be an optimal exchange rate. In such cases depending on the setting of the fixed exchan ge rate, welfare losses may occur with any move to a freely floating exchange rate, raising questions as to the desir- ability of a free Ren minbi float in China. Losses will n ec- essarily occur if the fixed exchange rate equals its opti- mal value. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. ME  H. HUANG ET AL. 531 Table 1. Parameters values used in 1 country 2 period 2 good numerical simulation exploration of optimal exchange rates. 1.1. Model Characteristics Small Open Price Taking Economy 1 Country 2 Per iod 2 Go o d Cobb Douglas Utility Functions within the Period 1.2. Model Parameterization Utility Inter-Temporal Discount Rate =0.10 Share Parameter in Preferences 0 1=0.5 0 2=0.50 1 1=0.6 1 2=0.40 0 1=20W0 2=80W 1 1=25W1 2=75W 0 1=1.00 2=1.00 1=1.01=1.00 01 = =1.50ee 1=200 S M 0 0 Initial Endowments World Prices 0 1 2 Initial Fixed Exchange Rate in Each Period 0 Domestic Money Supply in Each Period 0=160 S M and In the simulations we perform, we assume for simplic- ity Cobb-Douglas preferences and consider a case where period by period budget constraints apply reflecting u nl ib- eralized services trade. The model parameter settings we use in our simulations are given in Table 1. For this pa- rametrization, we take monetary policy as given and then compute equilibrium solutions for alternative settings of the exchange rate to explore the behaviour of the optimal exchange rate. Table 2 presents an equilibrium solution for this model, given the exchange rate and monetary policy in Table 1. For the case where no trading is allowed across peri- ods F = 0, and the equilibrium is given in the first col- umn of Table 2 (the model parametrization set out in Table 1). In this case when such trading is allowed, the foreign exchange premium value is the same in both pe- riods and equals 0.413. Utility increases from 94.641 to 95.125. Imports equals exports in each period and fall from 26.66 to 17.47 in period 0 and increase from 21.66 to 31.62 in period 1. Transactions across the period in- clude borrowing and lending of 13.379. Table 3 reports the optimal exchange rate for this mo d el parameterization, along with the welfare impacts which would follow with a move to a freely floating exchange rate under which the premium value on foreign exchange is eliminated. Utility reaches its maximal value of 96.38 51 when the common exchange rate e0 = e1 = 1.770 is used in both periods. If, instead the exchange rate is only var- ied in period 0, a similar utility gain occurs and utility Table 2. General equilibrium for the model parameteriza- tion set out in Table 1. Period by Period Budget Constraints Across Period Budget Constraints Interest Rate = 0.116r 0=0.143 1=0.714 01 ==0.413 0 1=1.714P0 1= 2.119P 0 2=1.500P0 2=1.500P 1 1=2.571P1 1=2.119P 1 2=1.500P1 2=1.500P 0= 49.889U0= 44.868U 1= 49.227U1= 55.282U = 94.641U= 95.125U 0 1= 46.667X0 1= 37.747X 0 2= 53.333X0 2= 53.333X 1 1=46.667X1 1=56.621X 1 2= 53.333X1 2= 53.333X 0 1= 26.667H0 1=17.747H 1 1=21.667H1 1= 31.621H 0 2= 26.667H0 2= 26.667H 1 2=21.667H1 2=21.667H 0=26.667 D N0=17.747 D N 1= 21.667 D N1= 31.621 D N =46.081 D N 0= 26.667 S N0=26.667 S N 1=21.667 S N1=21.667 S N = 46.081 S N 0=5.714R0=10. 992R 1= 23.214R1=19.585R = 28.541R 0= 320.000I0= 333.379I 1= 400.000I1=385.069I =0.000F=13.379F Exchange Rate Premium Value and Domestic Prices Utility Levels in Each Period, and Across Periods Consumption Imports of Good 1 Exports of Good 2 Foreign Currency Demand Foreign Currency Supply Foreign Exchange Premium Revenues in Each Period Income in Each Period Money Deposit Copyright © 2012 SciRes. ME  H. HUANG ET AL. 532 across the two periods is 96.207. In this case the loss is relative small, but this nonetheless establishes the pres u m p- tion in favour of a fixed over a floating exchange rate in this case when the rate is varied across both periods. Ta- ble 3 reports a utility loss relative to the optimal excha ng e rate in both periods when a freely floating exchange rate occurs. Table 4 reports the relationship between utility and domestic money supply changes, since changed monetary policy provides a substitute instrument for exchange rate policy in this model. Utility reaches its maximal value of 96.418 when the money supply S 0 in period 0 equals 112.000. Results in Table 4 also show the utility loss relative to optimal monetary policy when monetary pol- icy is used to eliminate the foreign exchange premium. In this case once again the difference is relatively small, but clearly present. A difference between Tables 3 and 4 is the impact on results of only allowing optimal policy interventions in one period. In the case of exchange rate policy, optimal intervention generates welfare effects which are smaller than those under a free float, and only with optimal com- mon exchange rates across the two periods is the gain lar - ger than that under free float. In contrast, the gain from optimal monetary policy only in period 1 ex ceeds that f r om optimal policy across the two periods. These outcomes reflect both direct gains from additional intermediation across time and the indirect effects between trade in goods Table 3. Maximum utility under an optimal exchanges rate (across period budget constraint equilibria in all cases). Base Case Optimal Exchange Rate Free Float Optimal Exchange Rate Equilibrium Equilibrium Equilibrium Equilibrium (Same Exchange Rate (S ame Excha nge Rate (Changing On ly Both Periods) Both Periods) Exchange Rate in Period 1) 3.1. Domestic Monetary Supply 0=160 S M 0=160 S M 0=160 S M Table 4. Maximum utility under an optimal monetary policy (across period budget constraint equilibria in all cases). Base CaseOpti mal Monetary Policy Optimal Monetary Policy Monetary Policy Equilibriumin Period 0 in Both Periods Set So as to Eliminate Foreign Exchange Premium 4.1. Domestic Monetary Supply 0=160 S M0=112.000 S M0=135.560 S M0=103.621 S M 1=200 S M1= 200.000 S M1=169.450 S M1= 200.000 S M 0=1.500e0=1.500e0=1.500e0=1.500e 1=1.500e1=1.500e1=1.500e1=1.500e 0=0.413 0= 0.051 0=0.0225 0=0.000 1=0.413 1=0.051 1=0.0225 1=0.000 4.2. Exchange Ra te 4.3. Exchange Rate P r emium Value 4.4. Utility across Periods 95.125 96.418 96.385 96.379 and over time, and which one dominates varies from case to case. These results thus suggest that a fixed exchange rate can dominate a f loating r ate if mo netar y policy is not a v ai l - able as the instrument to achieve the optimal trade inter- vention. 4. Conclusions This paper presents a model of international trade with both inter-temporal and inter-spatial trade motivatedly by current debate on both Renminbi revaluation and a pos- sible Renminbi free float in China. In this model if inter- temporal trade is restricted by service regulation and tar- iff rates are bound in the WTO, even for a small open price taking economy free trade in goods will typically not be the best policy. A fixed exchange rate policy with a surrender requirement on exporters and rationing (or auctioning) of foreign exchange among importers can be a welfare improving intervention compared to a free float- ing exchange rate. This analysis seems relevant to the p re - sent debate in China where services unliberalized until the terms of China’s WTO accession fully apply and tar- iff rates are bound under China’s WTO accession terms. 0=160 S M 1=200 S M 0=1.5000e 1=1.7857e 0=0.1783 1=0.1783 1=200 S M 1=200 S M 1=200 S M 3.2. Exchange Ra te 0=1.500e 0=1.770e 0=1.792e 1=1.500e 1=1.770e 1=1.792e 3.3. Exchange Rate P r emium Value 0=0.413 0=0.023 0=0.000 1=0.413 1=0.023 1=0.000 3.4. Utility Across Periods 95.125 96.385 96.379 96.207 While this analysis may not be fully realistic of the situation in economies such as China under international pressure to liberalize their exchange rate regime, it pro- vides possible intellectual coherence to a position that be st policy may not be to move to a free float prior to full financial services liberalization. In China, unlike in our analysis, there is no foreign exchange premium and Chin a runs a trade surplus in goods trade. However, to the ex- tend that concerns over possible capital flight motivate t he maintainence of the present exchange rate regime which Copyright © 2012 SciRes. ME  H. HUANG ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. ME 533 limits convertability, the broad themes of the analysis sti ll seem relevant. The policy implications thus run counter to accepted international conventional wisdom and point to possible advantag es of not freely floating. REFERENCES [1] M. Friedman, “Essays in Positive Economics,” Chapter on the Case for Flex Exchange Rate, 1956. [2] Z. Pan and F. Zhang, “Determination of China’s Long- Run Nominal Exchange Rate and Official Intervention,” China Economic Review, Vol. 15, No. 3, 2004, pp. 360- 365. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2004.04.002 [3] G. Chang and Q. Shao, “How Much Is the Chinese Cur- rency Undervalued? A Quantitative Estimation,” China Economic Review, Vol. 15, No. 3, 2004, pp. 366-371. [4] H. Huang, J. Whalley and S. Zhang, “Trade Liberaliza- tion in a Joint Spatial Inter-Temporal Trade Model,” Re- search Paper, The University of Western Ontario, 2004. [5] R. Clarete and J. Whalley, “Foreign Exchange Premia and Non-Neutrality of Monetary Policy in General Equilib- rium Models,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 30, No. 1-2, 1991, pp. 153-166. [6] Z. Chen and L. Schembri, “Measuring the Barriers to Trade in Services: Literature and Methodologies,” In: J. M. Curtis and D. C. Ciuriak, Eds., Trade Policy Research, Development of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, 2002. [7] J. Francois and L. Schuknecht, “International Trade in Financial Services, Competition and Growth Perform- ance,” Centre for International Economic Studies, No. 6, 2000. [8] K. Kalirajan, G. McHuire, D. Nguyen-Hong and M. Schuele, “The Price Impact of Restrictions on Banking Services,” In: C. Findlay and T. Warren, Eds., Impedi- ments to trade in Services: Measurement and Policy Im- plications, Routledge, New York, 2001. [9] A. Mattoo, “Financial Services and the WTO: Liberaliza- tion Commitments of the Developing and Transition Economies,” Policy Research Working Paper No. 2184, Developing Research Group, World Bank, Washington DC, 1999. [10] R. Radner, “Existence of Equilibrium of Plans, Prices and Price Expectations in a Sequence of Markets,” Economet- rica, Vol. 40, No. 2, 1972, pp. 289-303. doi:10.2307/1909407 [11] O. D. Hart, “On the Optimality of Equilibrium When the Market Structure Is Incomplete,” Journal of Economic Theory, Vol. 11, No. 3, 1975, pp. 418-443. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(75)90028-9 [12] D. Duffie and W. Shafer, “Equilibrium in Incomplete Markets: I: A Basic Model of Generic Existence,” Jour- nal of Mathematical Economics, Vol. 14, No. 3, 1985, pp. 285-300. [13] J. Werner, “Equilibrium in Economies with Incomplete Financial Markets,” Journal of Economic Theory, Vol. 36, No. 1, 1985, pp. 110-119. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(85)90081-X [14] D. Duffie, “Stochastic Equilibria with Incomplete Finan- cial Markets,” Journal of Economic Theory, Vol. 41, No. 2, 1987, pp. 405-416. [15] J. D. Geanakoplos, “An Introduction to General Equilib- rium with Incomplete Asset Markets,” Journal of Mathe- matical Economics, Vol. 19, No. 1-2, 1990, pp. 1-38. doi:10.1016/0304-4068(90)90034-7 [16] M. Magill and W. Shafer, “Incomplete Markets,” In: W. Hildenbrand and H. Sonnenschein, Eds., Handbook of Mathematical Economics, Vol. 4, Elsevier Science, New York, 1991, pp. 1523-1614. [17] M. Magill and M. Quinzii, “Theory of Incomplete Mar- kets,” MIT Press, Cambridge, 1996.

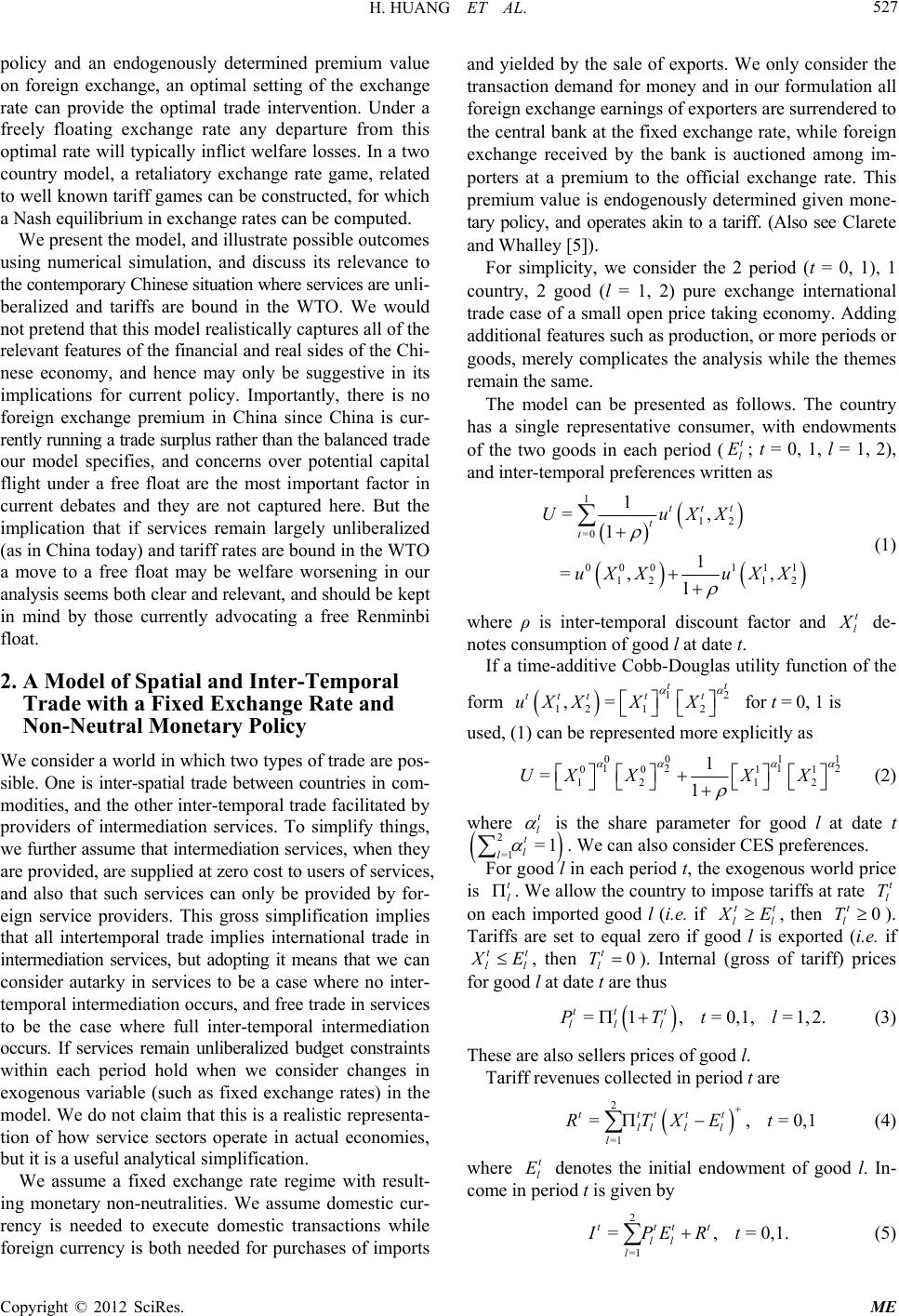

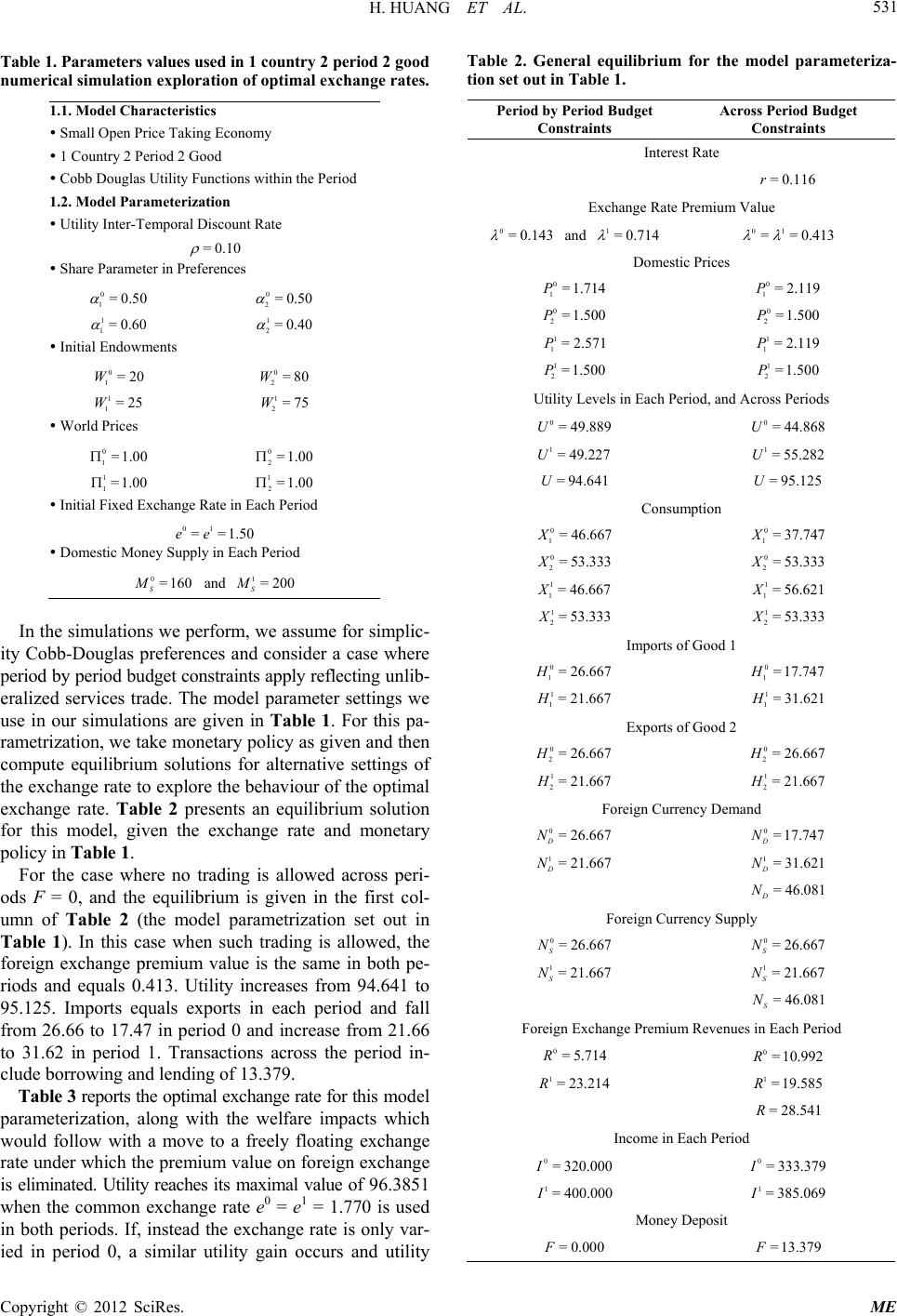

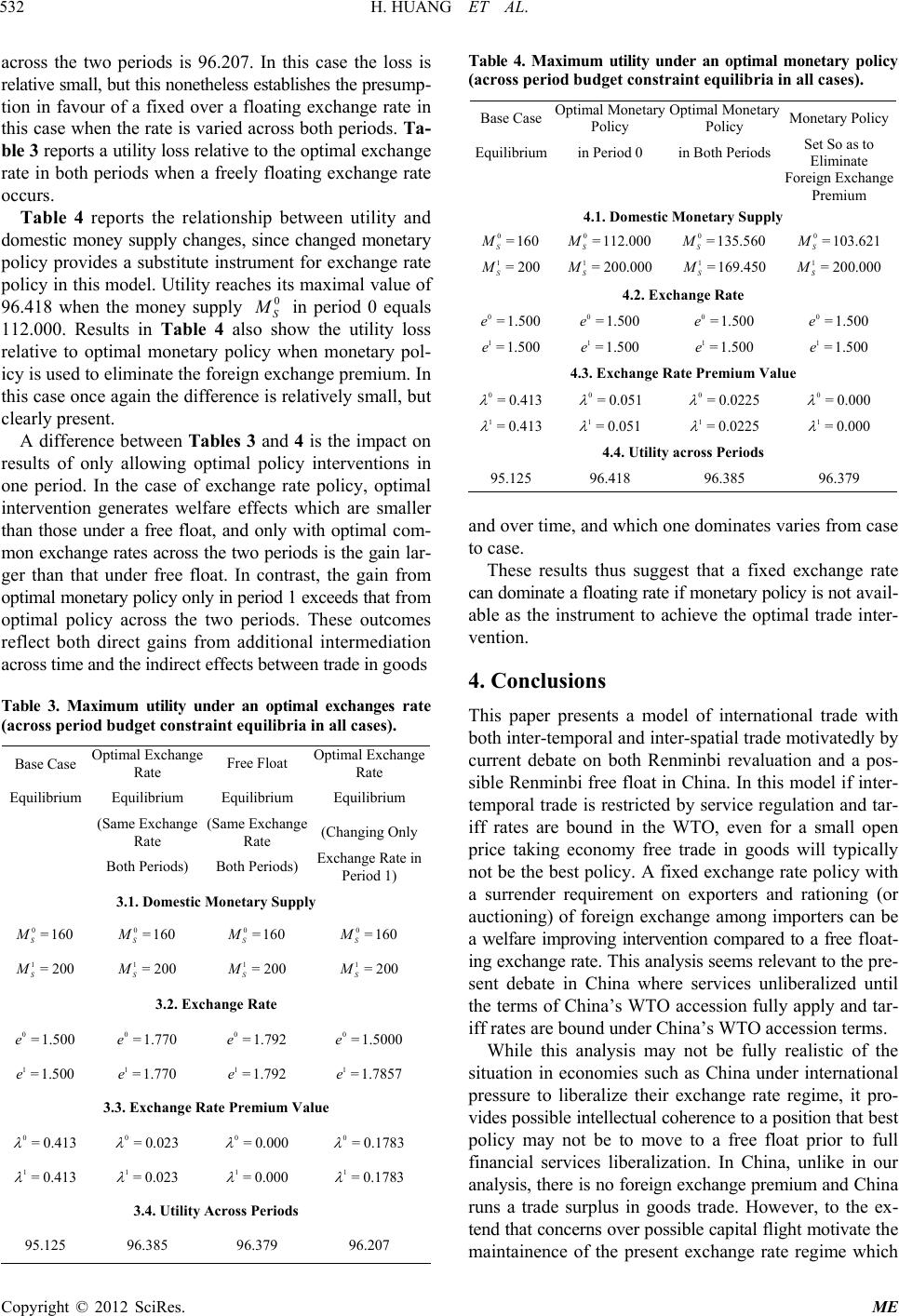

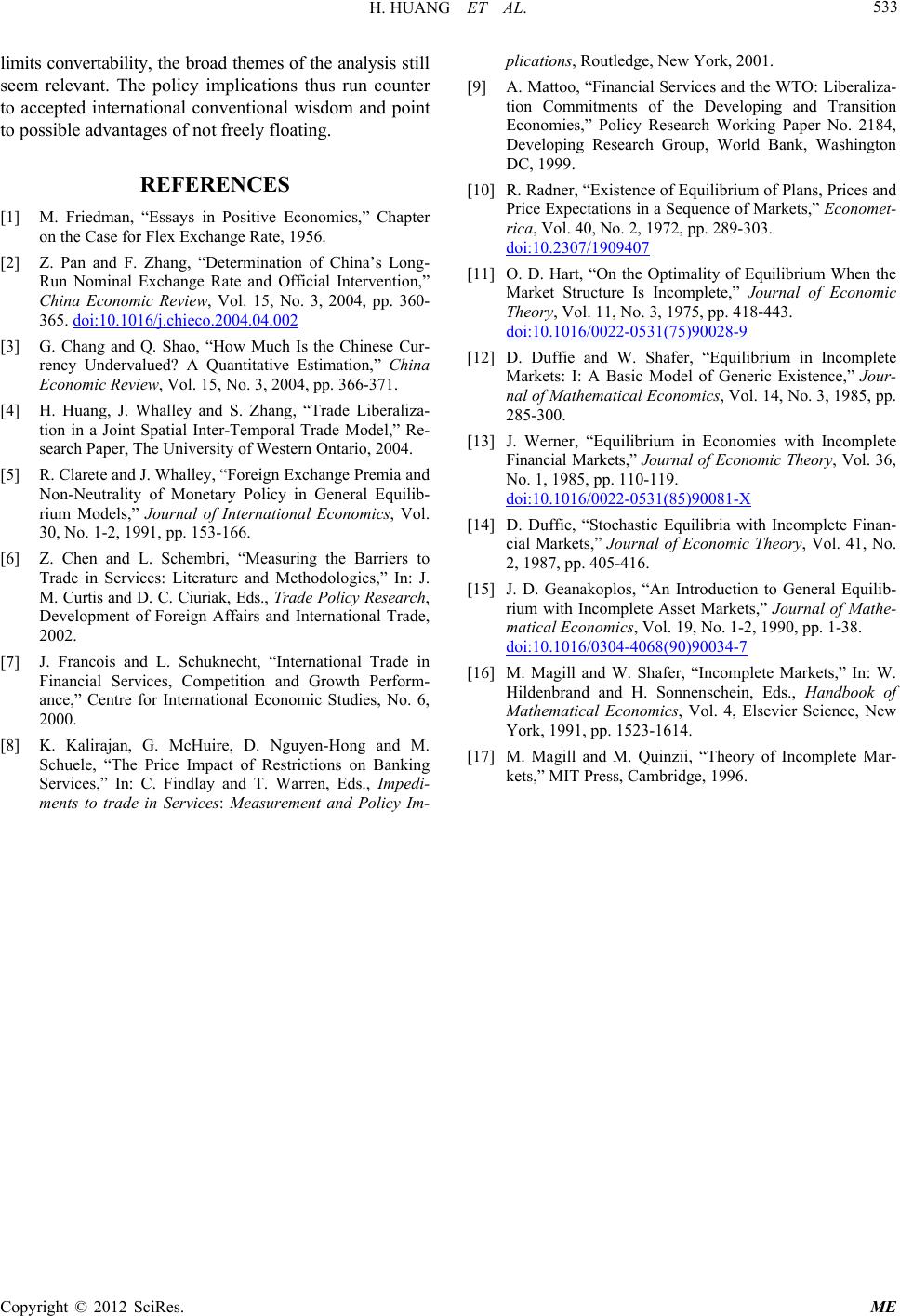

|