Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

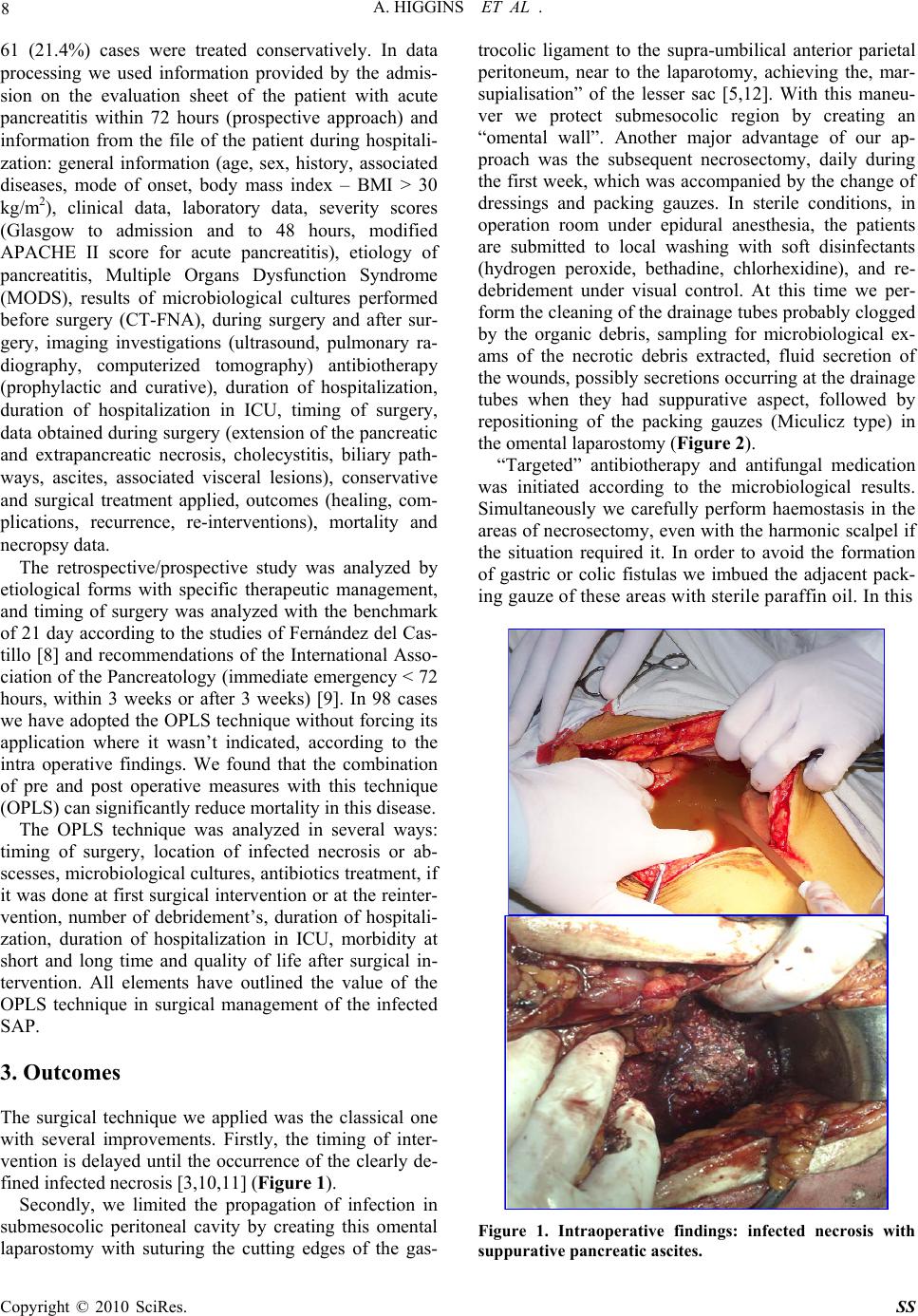

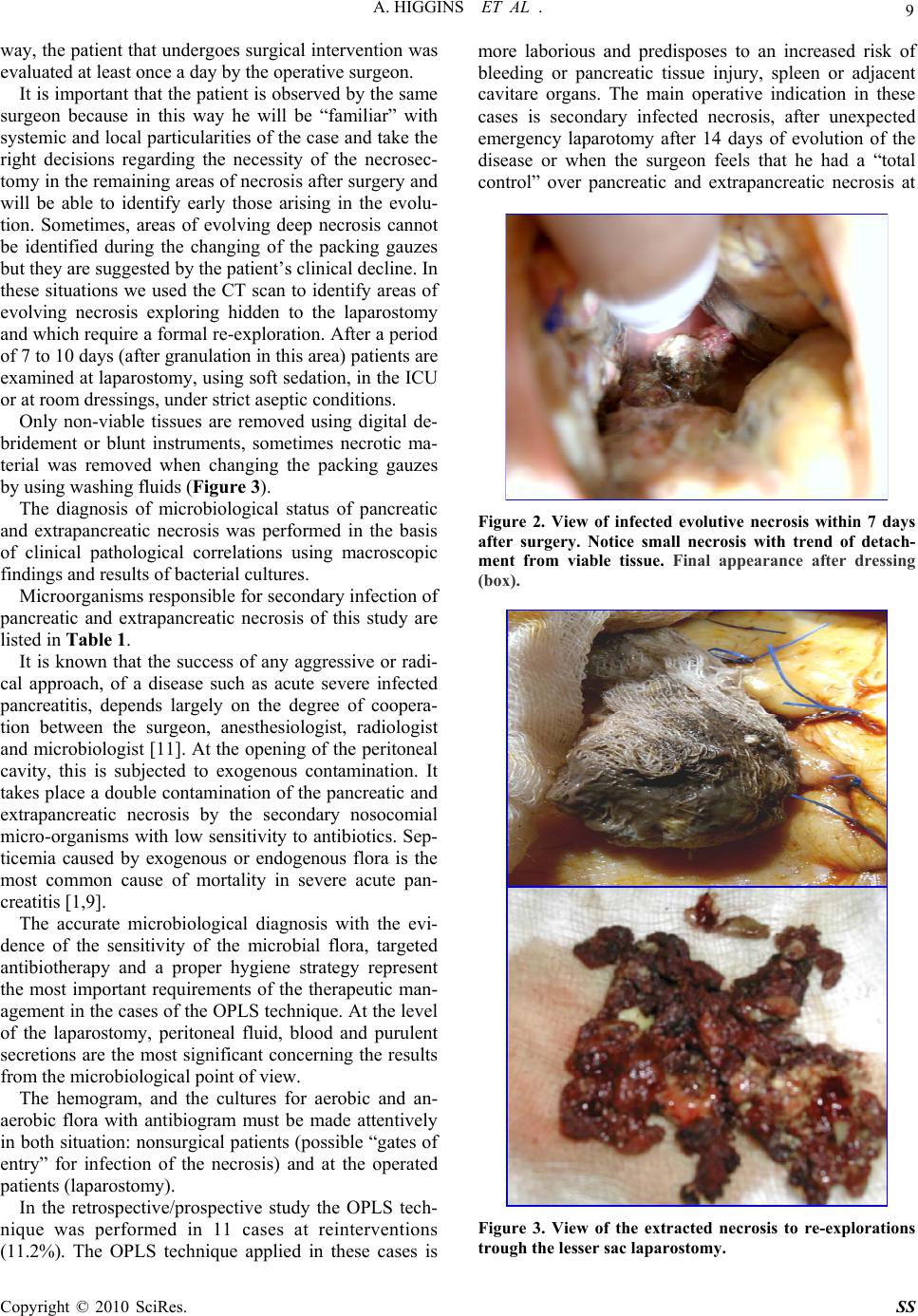

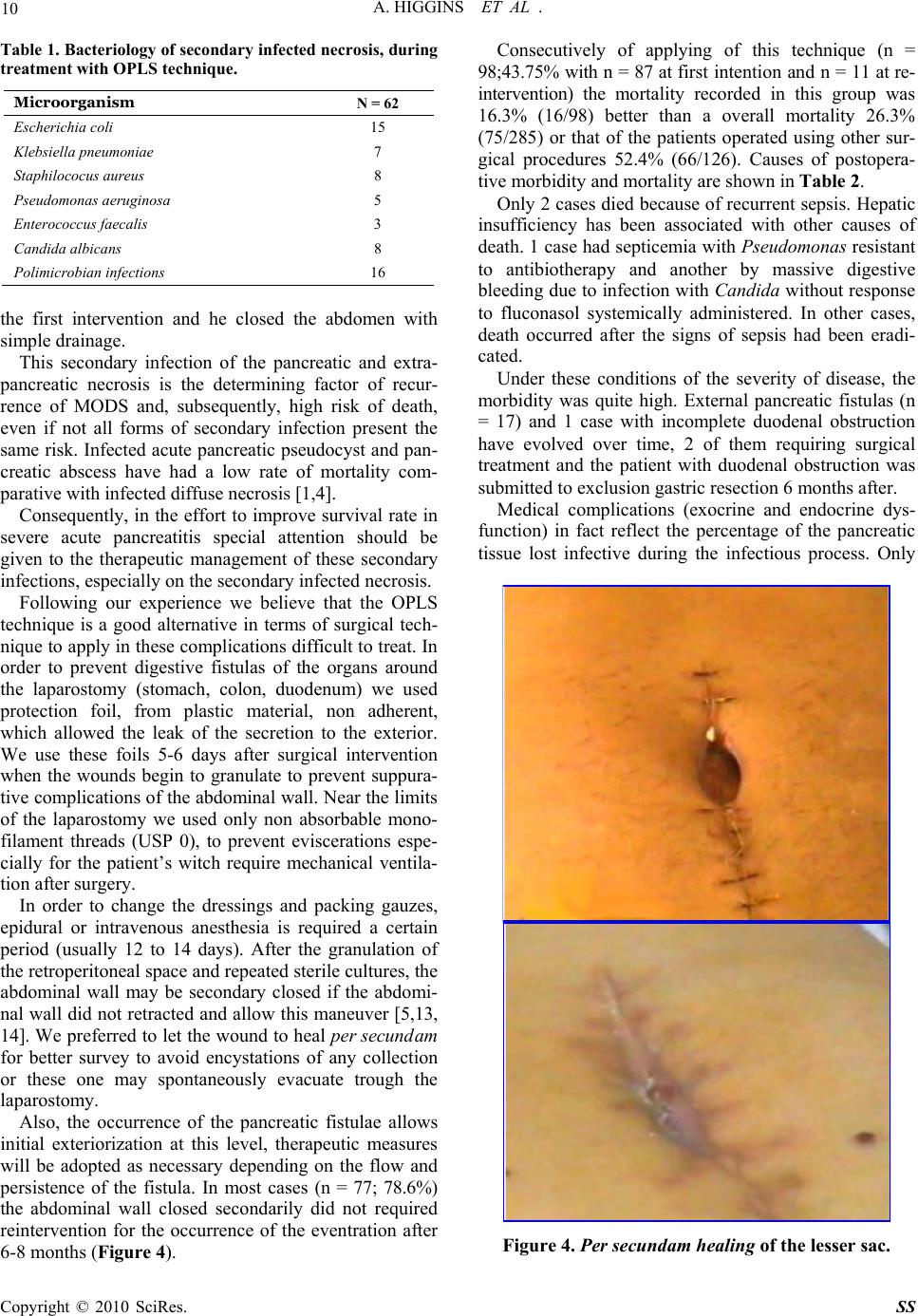

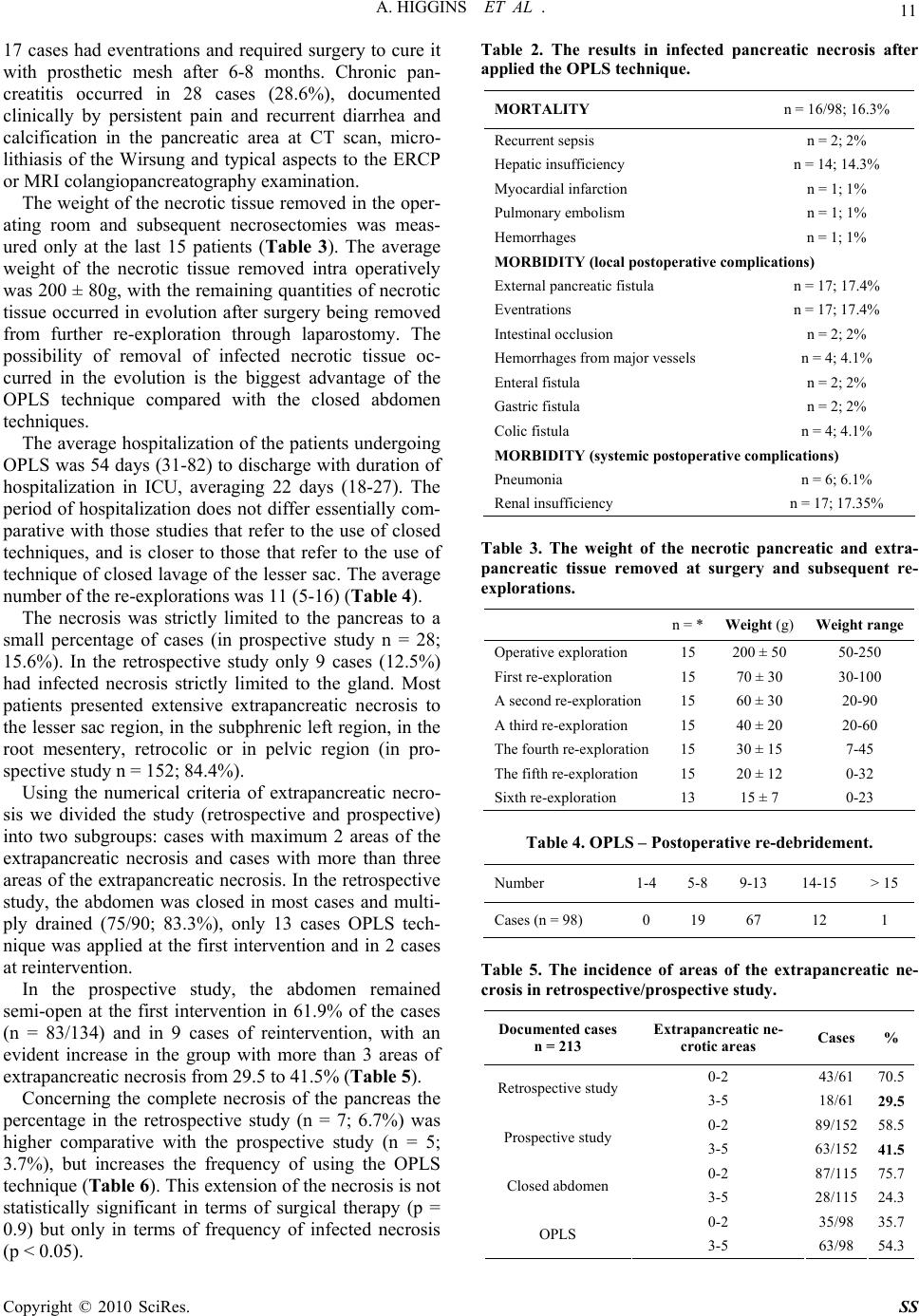

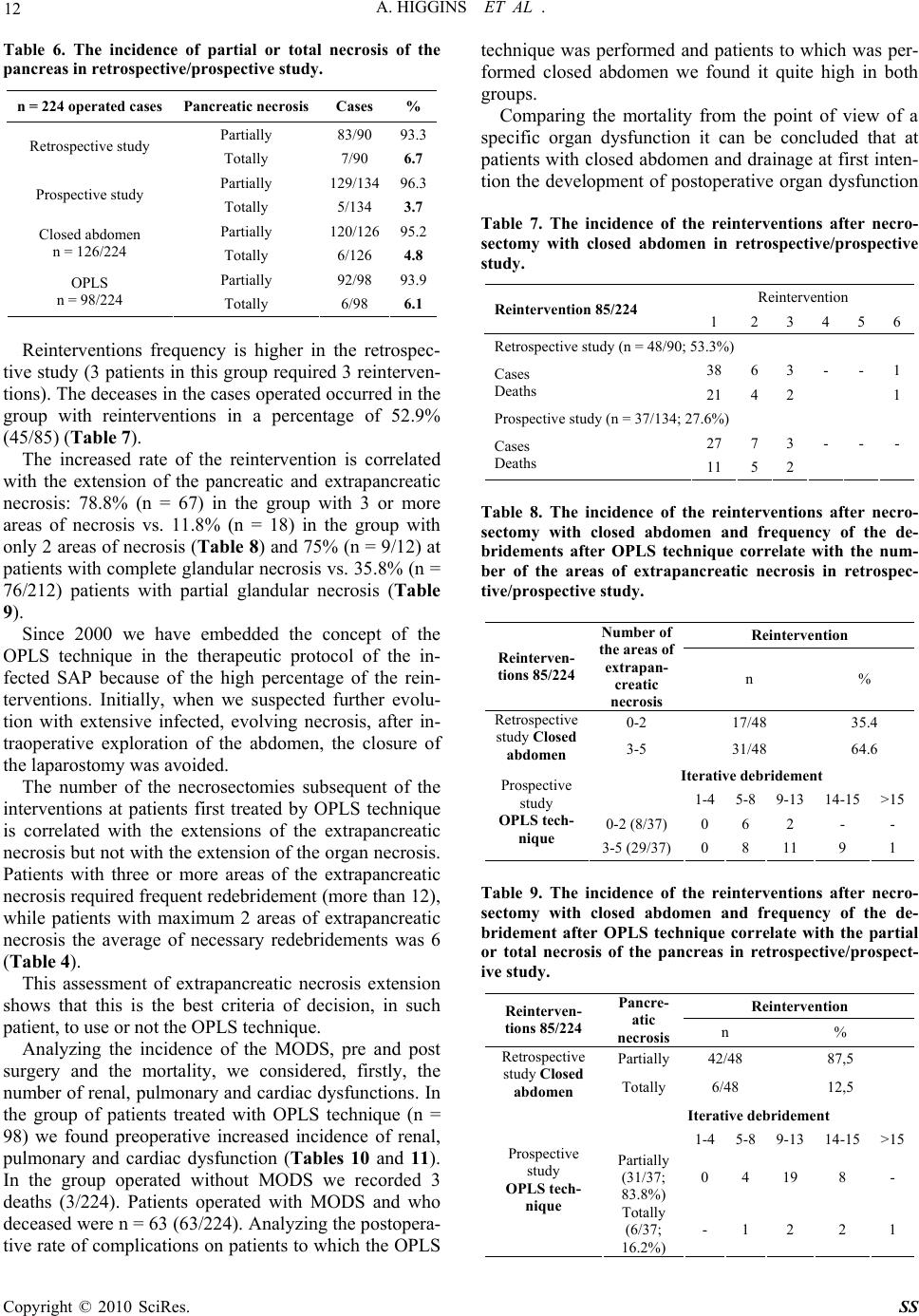

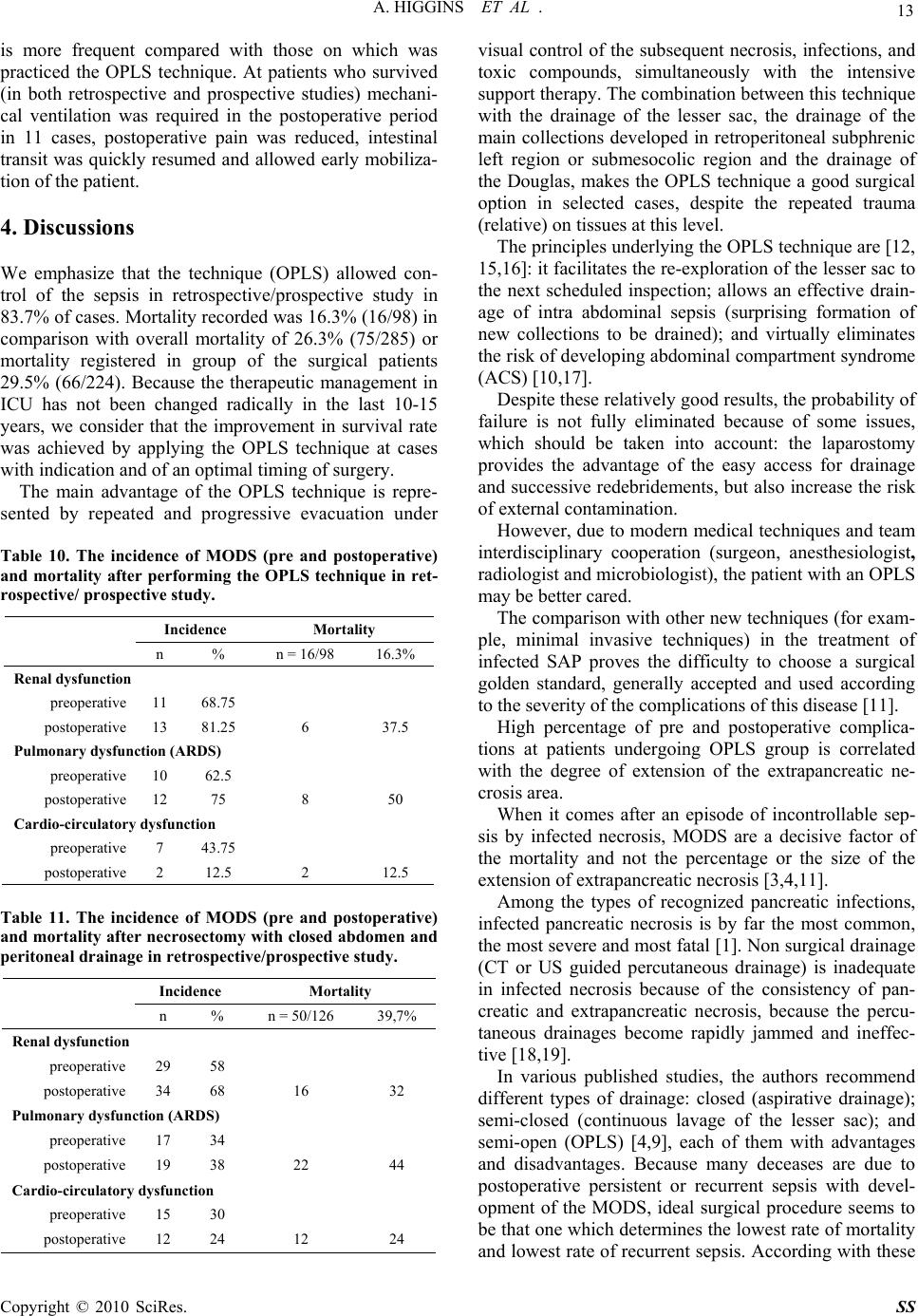

Surgical Science, 2010, 1, 7-14 doi:10.4236/ss.2010.11002 Published Online July 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ss) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. SS The Open Packing of the Lesser Sac Technique in Infected Severe Acute Pancreatitis D. Cochior1 S. Constantinoiu2, D. Peţa1, Mariana Cochior3, Rodica Bîrlă2, L. Pripişi1 1Clinical Hospital CF 2 Bucharest, Department of Surgery, Research Department, Faculty of Medicine of the University Titu Maiorescu, Bucharest, Rumania 2Clinical Hospital, “Santa Maria” Bucharest, Department of General and Esophageal Surgery University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, Bucharest, Rumania 3Emergency Clinic Hospital, Intensive Care Unit, University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, Bucharest, Rumania E-mail: daniel_cochior@yahoo.com Received April 14, 2010; accepted May 11, 2010 Abstract Aim: The goal of this study is to evaluate the open packing of the lesser sac (OPLS) in treatment of infected severe acute pancreatitis Methodology: The study was based on 98 cases in which this technique was ap- plied during the period between 1994-2007, in two departments of surgery (Clinical Hospital CF 2 and Clinical Hospital „Sf. Maria” Bucharest). The technique was applied based on the therapeutically protocol previously established beginning with 2000. The OPLS technique was analyzed relatively to: timing of sur- gery, the localization of the infected necrosis or abscesses, growing germs on the cultures, antibiotics re- ceived, executed primarily or at re-intervention, the number of debridement, hospitalization, morbidity and mortality. The information was statistically processed using SPSS test version 17 for Windows. Results: The OPLS technique improved the control of the local sepsis, in the retrospective/prospective study in 83.7%. Mortality was 16.3% (16/98), with a global mortality of 26.3% (75/285) and a postoperative mortality of 29.5% (66/224). Conclusions: Considering the fact that the intensive care techniques are approximately the same in the last 15 years, we thought that this improvement in the survival rate may be due to the application of OPLS in cases with indication and optimal timing for surgery. Keywords: Open Packing of the Lesser Sac (OPLS), Severe Acute Pancreatitis (SAP), Infected Necrosis, Pancreatic Abscess and Necrosectomy 1. Introduction Surgical intervention in infected SAP has as its main aim to counteract the effects of local septic complications [1]. There are still divergent opinions regarding surgical techniques adopted to be effective in treating pancreatic and extrapancreatic infections [2]. The decision of using a certain surgical technique after necrosectomy is indi- vidual and depends on the evolution of the disease, the timing of surgery, the extension of the pancreatic or ex- trapancreatic necrosis and on the surgeon’s experience [3, 4]. The usage of semi-open abdomen as in infected SAP therapy was first described in 1894 by Korte [5,6]. More recently, Bradley [7] has shown decreased mortality by using semi-open abdomen and subsequent re-explora- tion. 2. Material and Method Due to unsatisfactory results arising from the retrospec- tive analysis (1994-1999) after using pancreatic resection or a necrosectomy followed by multiple peritoneal drainages and closure of the abdominal wall, we adopted the therapeutic protocol based on aggressive intensive care, necrosectomy and semi-open abdomen technique, respectively the open packing of the lesser sac (OPLS) (prospective approach 2000-2007). The analysis includes 947 cases with acute pancreatitis admitted between 1994- 2007, in the 2 clinics (Clinical Hospital, Santa Maria” and Clinical Hospital CF 2 Bucharest) of which 285 cases with severe form (152 cases of male and 133 fe- male, the average age of 53.2 years). Of these 224 (78.6%) cases have undergone surgical intervention and  8 A. HIGGINS ET AL . 61 (21.4%) cases were treated conservatively. In data processing we used information provided by the admis- sion on the evaluation sheet of the patient with acute pancreatitis within 72 hours (prospective approach) and information from the file of the patient during hospitali- zation: general information (age, sex, history, associated diseases, mode of onset, body mass index – BMI > 30 kg/m2), clinical data, laboratory data, severity scores (Glasgow to admission and to 48 hours, modified APACHE II score for acute pancreatitis), etiology of pancreatitis, Multiple Organs Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS), results of microbiological cultures performed before surgery (CT-FNA), during surgery and after sur- gery, imaging investigations (ultrasound, pulmonary ra- diography, computerized tomography) antibiotherapy (prophylactic and curative), duration of hospitalization, duration of hospitalization in ICU, timing of surgery, data obtained during surgery (extension of the pancreatic and extrapancreatic necrosis, cholecystitis, biliary path- ways, ascites, associated visceral lesions), conservative and surgical treatment applied, outcomes (healing, com- plications, recurrence, re-interventions), mortality and necropsy data. The retrospective/prospective study was analyzed by etiological forms with specific therapeutic management, and timing of surgery was analyzed with the benchmark of 21 day according to the studies of Fernández del Cas- tillo [8] and recommendations of the International Asso- ciation of the Pancreatology (immediate emergency < 72 hours, within 3 weeks or after 3 weeks) [9]. In 98 cases we have adopted the OPLS technique without forcing its application where it wasn’t indicated, according to the intra operative findings. We found that the combination of pre and post operative measures with this technique (OPLS) can significantly reduce mortality in this disease. The OPLS technique was analyzed in several ways: timing of surgery, location of infected necrosis or ab- scesses, microbiological cultures, antibiotics treatment, if it was done at first surgical intervention or at the reinter- vention, number of debridement’s, duration of hospitali- zation, duration of hospitalization in ICU, morbidity at short and long time and quality of life after surgical in- tervention. All elements have outlined the value of the OPLS technique in surgical management of the infected SAP. 3. Outcomes The surgical technique we applied was the classical one with several improvements. Firstly, the timing of inter- vention is delayed until the occurrence of the clearly de- fined infected necrosis [3,10,11] (Figure 1). Secondly, we limited the propagation of infection in submesocolic peritoneal cavity by creating this omental laparostomy with suturing the cutting edges of the gas- trocolic ligament to the supra-umbilical anterior parietal peritoneum, near to the laparotomy, achieving the, mar- supialisation” of the lesser sac [5,12]. With this maneu- ver we protect submesocolic region by creating an “omental wall”. Another major advantage of our ap- proach was the subsequent necrosectomy, daily during the first week, which was accompanied by the change of dressings and packing gauzes. In sterile conditions, in operation room under epidural anesthesia, the patients are submitted to local washing with soft disinfectants (hydrogen peroxide, bethadine, chlorhexidine), and re- debridement under visual control. At this time we per- form the cleaning of the drainage tubes probably clogged by the organic debris, sampling for microbiological ex- ams of the necrotic debris extracted, fluid secretion of the wounds, possibly secretions occurring at the drainage tubes when they had suppurative aspect, followed by repositioning of the packing gauzes (Miculicz type) in the omental laparostomy (Figure 2). “Targeted” antibiotherapy and antifungal medication was initiated according to the microbiological results. Simultaneously we carefully perform haemostasis in the areas of necrosectomy, even with the harmonic scalpel if the situation required it. In order to avoid the formation of gastric or colic fistulas we imbued the adjacent pack- ing gauze of these areas with sterile paraffin oil. In this Figure 1. Intraoperative findings: infected necrosis with suppurative pancreatic ascites. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. SS  A. HIGGINS ET AL . 9 way, the patient that undergoes surgical intervention was evaluated at least once a day by the operative surgeon. It is important that the patient is observed by the same surgeon because in this way he will be “familiar” with systemic and local particularities of the case and take the right decisions regarding the necessity of the necrosec- tomy in the remaining areas of necrosis after surgery and will be able to identify early those arising in the evolu- tion. Sometimes, areas of evolving deep necrosis cannot be identified during the changing of the packing gauzes but they are suggested by the patient’s clinical decline. In these situations we used the CT scan to identify areas of evolving necrosis exploring hidden to the laparostomy and which require a formal re-exploration. After a period of 7 to 10 days (after granulation in this area) patients are examined at laparostomy, using soft sedation, in the ICU or at room dressings, under strict aseptic conditions. Only non-viable tissues are removed using digital de- bridement or blunt instruments, sometimes necrotic ma- terial was removed when changing the packing gauzes by using washing fluids (Figure 3). The diagnosis of microbiological status of pancreatic and extrapancreatic necrosis was performed in the basis of clinical pathological correlations using macroscopic findings and results of bacterial cultures. Microorganisms responsible for secondary infection of pancreatic and extrapancreatic necrosis of this study are listed in Table 1. It is known that the success of any aggressive or radi- cal approach, of a disease such as acute severe infected pancreatitis, depends largely on the degree of coopera- tion between the surgeon, anesthesiologist, radiologist and microbiologist [11]. At the opening of the peritoneal cavity, this is subjected to exogenous contamination. It takes place a double contamination of the pancreatic and extrapancreatic necrosis by the secondary nosocomial micro-organisms with low sensitivity to antibiotics. Sep- ticemia caused by exogenous or endogenous flora is the most common cause of mortality in severe acute pan- creatitis [1,9]. The accurate microbiological diagnosis with the evi- dence of the sensitivity of the microbial flora, targeted antibiotherapy and a proper hygiene strategy represent the most important requirements of the therapeutic man- agement in the cases of the OPLS technique. At the level of the laparostomy, peritoneal fluid, blood and purulent secretions are the most significant concerning the results from the microbiological point of view. The hemogram, and the cultures for aerobic and an- aerobic flora with antibiogram must be made attentively in both situation: nonsurgical patients (possible “gates of entry” for infection of the necrosis) and at the operated patients (laparostomy). In the retrospective/prospective study the OPLS tech- nique was performed in 11 cases at reinterventions (11.2%). The OPLS technique applied in these cases is more laborious and predisposes to an increased risk of bleeding or pancreatic tissue injury, spleen or adjacent cavitare organs. The main operative indication in these cases is secondary infected necrosis, after unexpected emergency laparotomy after 14 days of evolution of the disease or when the surgeon feels that he had a “total control” over pancreatic and extrapancreatic necrosis at Figure 2. View of infected evolutive necrosis within 7 days after surgery. Notice small necrosis with trend of detach- ment from viable tissue. Final appearance after dressing (box). Figure 3. View of the extracted necrosis to re-explorations trough the lesser sac laparostomy. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. SS  10 A. HIGGINS ET AL . Table 1. Bacteriology of secondary infected necrosis, during treatment with OPLS technique. Microorganism N = 62 Escherichia coli 15 Klebsiella pneumoniae 7 Staphilococus aureus 8 Pseudomonas aeruginosa 5 Enterococcus faecalis 3 Candida albicans 8 Polimicrobian infections 16 the first intervention and he closed the abdomen with simple drainage. This secondary infection of the pancreatic and extra- pancreatic necrosis is the determining factor of recur- rence of MODS and, subsequently, high risk of death, even if not all forms of secondary infection present the same risk. Infected acute pancreatic pseudocyst and pan- creatic abscess have had a low rate of mortality com- parative with infected diffuse necrosis [1,4]. Consequently, in the effort to improve survival rate in severe acute pancreatitis special attention should be given to the therapeutic management of these secondary infections, especially on the secondary infected necrosis. Following our experience we believe that the OPLS technique is a good alternative in terms of surgical tech- nique to apply in these complications difficult to treat. In order to prevent digestive fistulas of the organs around the laparostomy (stomach, colon, duodenum) we used protection foil, from plastic material, non adherent, which allowed the leak of the secretion to the exterior. We use these foils 5-6 days after surgical intervention when the wounds begin to granulate to prevent suppura- tive complications of the abdominal wall. Near the limits of the laparostomy we used only non absorbable mono- filament threads (USP 0), to prevent eviscerations espe- cially for the patient’s witch require mechanical ventila- tion after surgery. In order to change the dressings and packing gauzes, epidural or intravenous anesthesia is required a certain period (usually 12 to 14 days). After the granulation of the retroperitoneal space and repeated sterile cultures, the abdominal wall may be secondary closed if the abdomi- nal wall did not retracted and allow this maneuver [5,13, 14]. We preferred to let the wound to heal per secundam for better survey to avoid encystations of any collection or these one may spontaneously evacuate trough the laparostomy. Also, the occurrence of the pancreatic fistulae allows initial exteriorization at this level, therapeutic measures will be adopted as necessary depending on the flow and persistence of the fistula. In most cases (n = 77; 78.6%) the abdominal wall closed secondarily did not required reintervention for the occurrence of the eventration after 6-8 months (Figure 4). Consecutively of applying of this technique (n = 98;43.75% with n = 87 at first intention and n = 11 at re- intervention) the mortality recorded in this group was 16.3% (16/98) better than a overall mortality 26.3% (75/285) or that of the patients operated using other sur- gical procedures 52.4% (66/126). Causes of postopera- tive morbidity and mortality are shown in Table 2. Only 2 cases died because of recurrent sepsis. Hepatic insufficiency has been associated with other causes of death. 1 case had septicemia with Pseudomonas resistant to antibiotherapy and another by massive digestive bleeding due to infection with Candida without response to fluconasol systemically administered. In other cases, death occurred after the signs of sepsis had been eradi- cated. Under these conditions of the severity of disease, the morbidity was quite high. External pancreatic fistulas (n = 17) and 1 case with incomplete duodenal obstruction have evolved over time, 2 of them requiring surgical treatment and the patient with duodenal obstruction was submitted to exclusion gastric resection 6 months after. Medical complications (exocrine and endocrine dys- function) in fact reflect the percentage of the pancreatic tissue lost infective during the infectious process. Only Figure 4. Per secundam healing of the lesser sac. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. SS  A. HIGGINS ET AL . 11 17 cases had eventrations and required surgery to cure it with prosthetic mesh after 6-8 months. Chronic pan- creatitis occurred in 28 cases (28.6%), documented clinically by persistent pain and recurrent diarrhea and calcification in the pancreatic area at CT scan, micro- lithiasis of the Wirsung and typical aspects to the ERCP or MRI colangiopancreatography examination. The weight of the necrotic tissue removed in the oper- ating room and subsequent necrosectomies was meas- ured only at the last 15 patients (Table 3). The average weight of the necrotic tissue removed intra operatively was 200 ± 80g, with the remaining quantities of necrotic tissue occurred in evolution after surgery being removed from further re-exploration through laparostomy. The possibility of removal of infected necrotic tissue oc- curred in the evolution is the biggest advantage of the OPLS technique compared with the closed abdomen techniques. The average hospitalization of the patients undergoing OPLS was 54 days (31-82) to discharge with duration of hospitalization in ICU, averaging 22 days (18-27). The period of hospitalization does not differ essentially com- parative with those studies that refer to the use of closed techniques, and is closer to those that refer to the use of technique of closed lavage of the lesser sac. The average number of the re-explorations was 11 (5-16) (Table 4). The necrosis was strictly limited to the pancreas to a small percentage of cases (in prospective study n = 28; 15.6%). In the retrospective study only 9 cases (12.5%) had infected necrosis strictly limited to the gland. Most patients presented extensive extrapancreatic necrosis to the lesser sac region, in the subphrenic left region, in the root mesentery, retrocolic or in pelvic region (in pro- spective study n = 152; 84.4%). Using the numerical criteria of extrapancreatic necro- sis we divided the study (retrospective and prospective) into two subgroups: cases with maximum 2 areas of the extrapancreatic necrosis and cases with more than three areas of the extrapancreatic necrosis. In the retrospective study, the abdomen was closed in most cases and multi- ply drained (75/90; 83.3%), only 13 cases OPLS tech- nique was applied at the first intervention and in 2 cases at reintervention. In the prospective study, the abdomen remained semi-open at the first intervention in 61.9% of the cases (n = 83/134) and in 9 cases of reintervention, with an evident increase in the group with more than 3 areas of extrapancreatic necrosis from 29.5 to 41.5% (Table 5). Concerning the complete necrosis of the pancreas the percentage in the retrospective study (n = 7; 6.7%) was higher comparative with the prospective study (n = 5; 3.7%), but increases the frequency of using the OPLS technique (Table 6). This extension of the necrosis is not statistically significant in terms of surgical therapy (p = 0.9) but only in terms of frequency of infected necrosis (p < 0.05). Table 2. The results in infected pancreatic necrosis after applied the OPLS technique. MORTALITY n = 16/98; 16.3% Recurrent sepsis n = 2; 2% Hepatic insufficiency n = 14; 14.3% Myocardial infarction n = 1; 1% Pulmonary embolism n = 1; 1% Hemorrhages n = 1; 1% MORBIDITY (local postoperative complications) External pancreatic fistula n = 17; 17.4% Eventrations n = 17; 17.4% Intestinal occlusion n = 2; 2% Hemorrhages from major vessels n = 4; 4.1% Enteral fistula n = 2; 2% Gastric fistula n = 2; 2% Colic fistula n = 4; 4.1% MORBIDITY (systemic postoperative complications) Pneumonia n = 6; 6.1% Renal insufficiency n = 17; 17.35% Table 3. The weight of the necrotic pancreatic and extra- pancreatic tissue removed at surgery and subsequent re- explorations. n = * Weight (g) Weight range Operative exploration 15 200 ± 50 50-250 First re-exploration 15 70 ± 30 30-100 A second re-exploration 15 60 ± 30 20-90 A third re-exploration 15 40 ± 20 20-60 The fourth re-exploration15 30 ± 15 7-45 The fifth re-exploration 15 20 ± 12 0-32 Sixth re-exploration 13 15 ± 7 0-23 Table 4. OPLS – Postoperative re-debridement. Number 1-4 5-8 9-13 14-15 > 15 Cases (n = 98) 0 19 67 12 1 Table 5. The incidence of areas of the extrapancreatic ne- crosis in retrospective/prospective study. Documented cases n = 213 Extrapancreatic ne- crotic areas Cases% 0-2 43/6170.5 Retrospective study3-5 18/6129.5 0-2 89/15258.5 Prospective study 3-5 63/15241.5 0-2 87/11575.7 Closed abdomen 3-5 28/11524.3 0-2 35/9835.7 OPLS 3-5 63/9854.3 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. SS  12 A. HIGGINS ET AL . Table 6. The incidence of partial or total necrosis of the pancreas in retrospective/prospective study. n = 224 operated cases Pancreatic necrosis Cases % Partially 83/90 93.3 Retrospective study Totally 7/90 6.7 Partially 129/13496.3 Prospective study Totally 5/134 3.7 Partially 120/12695.2 Closed abdomen n = 126/224 Totally 6/126 4.8 Partially 92/98 93.9 OPLS n = 98/224 Totally 6/98 6.1 Reinterventions frequency is higher in the retrospec- tive study (3 patients in this group required 3 reinterven- tions). The deceases in the cases operated occurred in the group with reinterventions in a percentage of 52.9% (45/85) (Table 7). The increased rate of the reintervention is correlated with the extension of the pancreatic and extrapancreatic necrosis: 78.8% (n = 67) in the group with 3 or more areas of necrosis vs. 11.8% (n = 18) in the group with only 2 areas of necrosis (Table 8) and 75% (n = 9/12) at patients with complete glandular necrosis vs. 35.8% (n = 76/212) patients with partial glandular necrosis (Table 9). Since 2000 we have embedded the concept of the OPLS technique in the therapeutic protocol of the in- fected SAP because of the high percentage of the rein- terventions. Initially, when we suspected further evolu- tion with extensive infected, evolving necrosis, after in- traoperative exploration of the abdomen, the closure of the laparostomy was avoided. The number of the necrosectomies subsequent of the interventions at patients first treated by OPLS technique is correlated with the extensions of the extrapancreatic necrosis but not with the extension of the organ necrosis. Patients with three or more areas of the extrapancreatic necrosis required frequent redebridement (more than 12), while patients with maximum 2 areas of extrapancreatic necrosis the average of necessary redebridements was 6 (Table 4). This assessment of extrapancreatic necrosis extension shows that this is the best criteria of decision, in such patient, to use or not the OPLS technique. Analyzing the incidence of the MODS, pre and post surgery and the mortality, we considered, firstly, the number of renal, pulmonary and cardiac dysfunctions. In the group of patients treated with OPLS technique (n = 98) we found preoperative increased incidence of renal, pulmonary and cardiac dysfunction (Tables 10 and 11). In the group operated without MODS we recorded 3 deaths (3/224). Patients operated with MODS and who deceased were n = 63 (63/224). Analyzing the postopera- tive rate of complications on patients to which the OPLS technique was performed and patients to which was per- formed closed abdomen we found it quite high in both groups. Comparing the mortality from the point of view of a specific organ dysfunction it can be concluded that at patients with closed abdomen and drainage at first inten- tion the development of postoperative organ dysfunction Table 7. The incidence of the reinterventions after necro- sectomy with closed abdomen in retrospective/prospective study. Reintervention Reintervention 85/224 1 2 3 456 Retrospective study (n = 48/90; 53.3%) 38 6 3 - - 1 Cases Deaths 21 4 2 1 Prospective study (n = 37/134; 27.6%) 27 7 3 - -- Cases Deaths 11 5 2 Table 8. The incidence of the reinterventions after necro- sectomy with closed abdomen and frequency of the de- bridements after OPLS technique correlate with the num- ber of the areas of extrapancreatic necrosis in retrospec- tive/prospective study. Reintervention Reinterven- tions 85/224 Number of the areas of extrapan- creatic necrosis n % 0-2 17/48 35.4 Retrospective study Closed abdomen 3-5 31/48 64.6 Iterative debridement 1-4 5-8 9-13 14-15 >15 0-2 (8/37) 0 6 2 - - Prospective study OPLS tech- nique 3-5 (29/37)0 8 11 9 1 Table 9. The incidence of the reinterventions after necro- sectomy with closed abdomen and frequency of the de- bridement after OPLS technique correlate with the partial or total necrosis of the pancreas in retrospective/prospect- ive study. Reintervention Reinterven- tions 85/224 Pancre- atic necrosis n % Partially42/48 87,5 Retrospective study Closed abdomen Totally 6/48 12,5 Iterative debridement 1-4 5-8 9-13 14-15 >15 Partially (31/37; 83.8%) 0 4 19 8 - Prospective study OPLS tech- nique Totally (6/37; 16.2%) - 1 2 2 1 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. SS  A. HIGGINS ET AL . 13 is more frequent compared with those on which was practiced the OPLS technique. At patients who survived (in both retrospective and prospective studies) mechani- cal ventilation was required in the postoperative period in 11 cases, postoperative pain was reduced, intestinal transit was quickly resumed and allowed early mobiliza- tion of the patient. 4. Discussions We emphasize that the technique (OPLS) allowed con- trol of the sepsis in retrospective/prospective study in 83.7% of cases. Mortality recorded was 16.3% (16/98) in comparison with overall mortality of 26.3% (75/285) or mortality registered in group of the surgical patients 29.5% (66/224). Because the therapeutic management in ICU has not been changed radically in the last 10-15 years, we consider that the improvement in survival rate was achieved by applying the OPLS technique at cases with indication and of an optimal timing of surgery. The main advantage of the OPLS technique is repre- sented by repeated and progressive evacuation under Table 10. The incidence of MODS (pre and postoperative) and mortality after performing the OPLS technique in ret- rospective/ prospective study. Incidence Mortality n % n = 16/98 16.3% Renal dysfunction preoperative 11 68.75 postoperative 13 81.25 6 37.5 Pulmonary dysfunction (ARDS) preoperative 10 62.5 postoperative 12 75 8 50 Cardio-circulatory dysfunction preoperative 7 43.75 postoperative 2 12.5 2 12.5 Table 11. The incidence of MODS (pre and postoperative) and mortality after necrosectomy with closed abdomen and peritoneal drainage in retrospective/prospective study. Incidence Mortality n % n = 50/126 39,7% Renal dysfunction preoperative 29 58 postoperative 34 68 16 32 Pulmonary dysfunction (ARDS) preoperative 17 34 postoperative 19 38 22 44 Cardio-circulatory dysfunction preoperative 15 30 postoperative 12 24 12 24 visual control of the subsequent necrosis, infections, and toxic compounds, simultaneously with the intensive support therapy. The combination between this technique with the drainage of the lesser sac, the drainage of the main collections developed in retroperitoneal subphrenic left region or submesocolic region and the drainage of the Douglas, makes the OPLS technique a good surgical option in selected cases, despite the repeated trauma (relative) on tissues at this level. The principles underlying the OPLS technique are [12, 15,16]: it facilitates the re-exploration of the lesser sac to the next scheduled inspection; allows an effective drain- age of intra abdominal sepsis (surprising formation of new collections to be drained); and virtually eliminates the risk of developing abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) [10,17]. Despite these relatively good results, the probability of failure is not fully eliminated because of some issues, which should be taken into account: the laparostomy provides the advantage of the easy access for drainage and successive redebridements, but also increase the risk of external contamination. However, due to modern medical techniques and team interdisciplinary cooperation (surgeon, anesthesiologist, radiologist and microbiologist), the patient with an OPLS may be better cared. The comparison with other new techniques (for exam- ple, minimal invasive techniques) in the treatment of infected SAP proves the difficulty to choose a surgical golden standard, generally accepted and used according to the severity of the complications of this disease [11]. High percentage of pre and postoperative complica- tions at patients undergoing OPLS group is correlated with the degree of extension of the extrapancreatic ne- crosis area. When it comes after an episode of incontrollable sep- sis by infected necrosis, MODS are a decisive factor of the mortality and not the percentage or the size of the extension of extrapancreatic necrosis [3,4,11]. Among the types of recognized pancreatic infections, infected pancreatic necrosis is by far the most common, the most severe and most fatal [1]. Non surgical drainage (CT or US guided percutaneous drainage) is inadequate in infected necrosis because of the consistency of pan- creatic and extrapancreatic necrosis, because the percu- taneous drainages become rapidly jammed and ineffec- tive [18,19]. In various published studies, the authors recommend different types of drainage: closed (aspirative drainage); semi-closed (continuous lavage of the lesser sac); and semi-open (OPLS) [4,9], each of them with advantages and disadvantages. Because many deceases are due to postoperative persistent or recurrent sepsis with devel- opment of the MODS, ideal surgical procedure seems to be that one which determines the lowest rate of mortality and lowest rate of recurrent sepsis. According with these Copyright © 2010 SciRes. SS  A. HIGGINS ET AL . Copyright © 2010 SciRes. SS 14 requirements, choosing the OPLS technique during the management of infected necrotic lesions appears fully justified. In the prospective group was obtained an im- provement of therapeutic results because of the patients with extensive infected necrosis were treated by OPLS technique. Despite the limitation caused by a relatively small number of cases, due to the surgical experience of op- erators, we believe that especially at patients with in- fected extensive extrapancreatic necrosis, which devel- ops mainly at the lesser sac region, necrosectomy with a complete removal of infected necrotic tissue, with lavage and subsequent re-explorations, is better than an inter- vention which close the abdominal wall with continuous lavage, aspirative drainage or planned relaparotomy. 5. References [1] M. W. Büchler, B. Gloor, C. A. Muller, H. Friess, C. A. Seiler and W. Uhl, “Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis: Treatment Strategy According to the Status of Infection,” Annals of Surgery, Vol. 232, No. 5, 2000, pp. 619-626. [2] J. A. Harris, R. P. Jury, J. Catto and J. L. Glover, “Closed Drainage Versus Open Packing of Infected Pancreatic Necrosis”, Annals of Surgery, Vol. 61, No. 7, 1995, pp. 612-618. [3] M. Besselink, T. J. Verwer, E. Schoenmaeckers, E. Buskens, B. U. Ridwan, M. R. Visser, V. B. Nieuwen- huijs and H. G. Gooszen., “Timing of Surgical Interven- tion in Necrotizing Pancreatitis”, Archives of Surgery, Vol. 142, No. 12, 2007, pp. 1194-1201. [4] King NK, Siriwardena AK, “European Survey of Surgical Strategies for the Management of Severe Acute Pan- creatitis,” The American Journal of Gastroenterology, Vol. 99, No. 4, 2004, pp. 719-728. [5] H. W. Waclawiczek, F. Chmelizek, M. Heinerman, W. Pimpl, H. Kaindl, P. Sungler and O. Boeckl, “Laparostoma (Open Packing) in the Treatment Concept of Infected Pancreatic Necroses,” Wien Klin Wochenschr, Vol. 104, No. 15, 1992, pp. 443-447. [6] G. Funariu, V. Binţinţan, R. Seicean and R. Scurtu, “Sur- gical Treatment of Severe Acute Pancreatitis” Chirurgia Bucharest, Vol. 101, No. 6, 1990, pp. 599-607. [7] E. L. Bradley, “A Clinically Based Classification System for Acute Pancreatitis: Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis,” Archives of Surgery, Vol. 128, No. 5, 1993, Atlanta, pp. 586-590. [8] del C. C. Fernandez, D. W. Rattner, M. A. Makary, V. I. A, Mostafa, D. McGrath and A. L. Warshaw, “Debride- ment and Closed Packing for the Treatment of Necrotiz- ing Pancreatitis,” Annals of Surgery, Vol. 228, No. 5, 1998, pp. 676-684. [9] W. Uhl, A. Warshaw and C. Imrie, “IAP Guidelines for the Surgical Management of Acute Pancreatitis,” Pan- creatology, 2002, Vol. 2, No. 6, pp. 565-573. [10] S. Connor and J. P. Neoptolemos, “Surgery for Pancreatic Necrosis: ‘Whom, When and What’,” World Journal of Gastroenterology, Vol. 10, No. 12, 2004, pp. 1697-1698. [11] I. Popescu, “Management of the Severe Acute Pancreati- tis,” Chirurgia, Vol. 101, 2006, pp. 225-228. [12] G. Funariu, M. Suteu, G. Dindelegan, N. Maftei and R. Scurtu, “The Indications for Celiostomy in Acute Ne- crotizing Pancreatitis,” Chirurgia, 1990, Vol. 93, No. 6, pp. 395-400. [13] A. Leppäniemi, “Open Abdomen after Severe Acute Pan- creatitis,” European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery, 2008, Vol. 34, 17-23. [14] G. Farkas, “Pancreatic Head Mass: How can we Treat it? Acute Pancreatitis: Surgical Treatment,” Journal of the Pancreas, Vol. 1, No. 3, 2000, pp. 138-142. [15] L. Edward and E. L. III Bradley, “Open Packing in In- fected Pancreatic Necrosis,” Digestive Surgery, Vol. 997, pp. 77-81. [16] J. Lange, “Therapy of Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis with Open Packing,” Digestive Surgery, 1994, Vol. 11, pp. 257-260. [17] C. Bassi, G. Butturini, M. Falconi, R. Salvia, I. Frigerio, and P. Pederzoli, “Outcome of Open Necrosectomy in Acute Pancreatitis,” Pancreatology, 2003, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 128-132. [18] T. Bruennler, J. Langgartner, S. Lang, C. E. Wrede, F. Klebl, S. Zierhut, S. Siebig, F. Mandraka, F. Rockmann, B. Salzberger, S. Feuerbach, J. Schoelmerich and O.W. Hamer, “Outcome of Patients with Acute, Necrotizing Pancreatitis Requiring Drainage-Does Drainage Size Matter?” World Journal of Gastroenterology, Vol. 14, No. 5, 2008, pp. 725-730. [19] C. R. Carter, C. J. McKay and C. W. Imrie, “Percutane- ous Necrosectomy and Sinus Tract Endoscopy in the Management of Infected Pancreatic Necrosis: An Initial Experience,” Annals of Surgery, Vol. 232, 2000, pp. 175-180. |