iBusiness, 2012, 4, 265-278 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ib.2012.43034 Published Online September 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ib) 265 Economies of Scale in Local Government: General Government Spending Lawrence Southwick School of Management University at Buffalo, Amherst, NY, USA. Email: ls5@buffalo.edu Received March 6th, 2012; revised April 11th, 2012; accepted June 18th, 2012 ABSTRACT The purpose of this paper is to determine whether larger or smaller municipalities are more efficient in their levels of overhead costs. The operative measure is per capita annual costs for these services. In addition, the issue of market structure as a factor in these costs is also to be studied. It is not for the purpose of considering costs for specific services but rather the general overhead items that are required of all local governments. The method of study will be to use the cities and towns of New York State over a number of years. This will ensure that the study group is relatively homoge- neous over applicable state laws as well as giving a wide variation in the population levels studied. The per capita ex- penditures will be regressed against population and market power variables using several equation forms. The results will be tested for significance in scale effects and market power effects. Optimal population sizes will be calculated where possible. The outline of the paper is as follows: 1) Introduction; 2) Background issues; 3) The study design; 4) Data; 5) Results; and 6) Conclusions. Keywords: Local Government; Economies of Scale; Market Power 1. Introduction Should municipalities merge in order to take advantage of having fewer mayors/city managers/department heads, etc.? Would there be meaningful savings for the taxpay- ers if they did so? Are there reasons why such mergers would not be cost saving? This paper is written to look at these questions from the relatively narrow perspective of overhead costs. Other issues could also be considered but this is one that all governments have in common. Further, quality issues in this area are generally less important to the constituents than are costs; the public wants these functions performed but the quality of that performance is either difficult to measure or matters little to the citi- zenry. This paper aims to consider the question of operating economies of scale. A larger municipality may have eco- nomies of scale because of the possibility of greater spe- cialization for its personnel. On the other hand, a smaller organization may be more flexible in responding to chang- ing conditions. The larger municipality may be able to achieve economies in purchasing. The smaller munici- pality may be able to better control “inventory evapora- tion”. The larger municipality may be able to afford bet- ter personnel. The smaller municipality may be better able to control the behavior of the employees. These and other factors may well enter into scale issues. There is also the question of the effect of market pow- er on the costs of government. It could be that the larger municipality could, through a greater dominance of the market, exploit its position and could extract extra re- muneration for its employees. On the other hand, the smaller municipality may be less aware and possibly less able to control such agency costs. This factor may enter into the resulting cost and needs to be considered along with operating scale effects. This paper is written with the intention of testing em- pirically whether there are or are not economies of scale and whether market power plays a role in costs. The par- ticular function to be considered here will be the over- head costs of local governments, measured on a per cap- ita basis. Other costs are more choice oriented, as, for example, in policing where choices on the amounts of policing may be made, taking into account the tradeoff between the cost of such services and the amount of crime tolerated1. 2. Background Issues Start with some background theories. First is Tiebout’s [1] theory that people vote with their feet. To the extent they are able, they choose municipalities that best fit their 1See, for example, Southwick [41]. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB  Economies of Scale in Local Government: General Government Spending 266 choice of services and taxes. It is certainly easier to move from one brand of beer to another than to change one’s residence, especially if the residence is owned. Then, there is a cost to selling a house as well as a cost to find- ing another house and buying it. Even if the residence is rented, there is a cost to moving one’s belongings and settling in a new community. This is likely to be the rea- son that people who are moving into an area from some other area of the country are so selective in making the initial choice; they don’t want to have to incur those costs a second time. It follows, for current residents, that the local government may be able to move away from the consumer’s preferred position up to the point where the disutility of moving just equals the loss due to staying; that is, the difference between the net utility given by a potential competitive community and the net utility in the current location. The fewer the competitors in the rele- vant region or the smaller the differences between them, the less likely a move will be advantageous to the con- sumer. Thus, the possible exploitation of the consumer is limited by these differences as well as by the costs of moving. Epple, et al. [2] argue that both migration costs and voting costs are important determinants of consumer decisions. Percy, et al. [3] provide further support. Most migration between municipalities in a region is through outflows from an overpriced (relative to service value) community where those leaving move elsewhere in the nation and those moving to the area choosing a different community in which to settle. Since at least the 1950s, the City of Buffalo, NY, has been losing popula- tion while its suburbs have gained. Most out-migration, however, is through death or moves to retirement com- munities in other parts of the US while neighboring communities like Amherst, NY, have been able to attract those who move to the area through more attractive ser- vice and tax policies. Amherst has been steadily increas- ing its population during the same half century. Over the 50 year period from 1950 to 2000, Buffalo decreased from 580,132 to 292,648 or an average decrease of 1.37 percent per year. Over the same period, Amherst in- creased from 33,744 to 116,510 or an average increase of 2.48 percent per year. It will be noted that this is a rela- tively long time frame relative to consumer changes for many other products. The depreciation rate for housing tends to be lower than for cars, for example. For this reason, while moves from one municipality to another in the same region do happen, such moves are generally a smaller portion of the moves affecting population levels. It is also the case that tastes differ. Some people prefer higher levels of government services and accept the needed increases in taxes that are likely to go along with the higher services. Since people will tend to sort them- selves by choosing where they live, this is likely to result in clusters of people with similar preferences. As an ex- ample, public primary and secondary education is one of the major attractions to some people as well as being the largest reason for local taxes. Persons who have no chil- dren are less likely to choose to live in a community with high school taxes and excellent schools than are people with school-age children2. The result of having more municipalities from which to choose is that the differences between them will be less pronounced for a given overall population size than will be the case with fewer municipalities3. This further implies that people will be better able to choose a mu- nicipality that is more closely consonant with their pref- erences. It should be expected that more effort will be placed on affecting elections the more varied in prefer- ences the electorate in a community is. Consequently, having more municipalities available in a geographic area may well result in lower political effort as people are sorted into communities according to their prefer- ences. If this sorting is more difficult or expensive, it will be necessary to achieve one’s desired levels of spending and taxes by political means rather than by moving to a more congenial community. Individual preferences, expressed both through voting and migration will increase the variances in spending but may not affect the overall average level of spending; higher spending levels in some communities may be ba- lanced out by lower spending levels in other communi- ties. People are likely to be more varied in their prefer- ences across communities if it is easy to migrate. A second important effect is that of Leviathan. Levia- than is a theory that government acts to maximize its spending (see Brennan & Buchanan [4]). It is argued that the managers in a government benefit by having more spending. This can be promoted by having greater market power. Presumably, the government personnel are able to obtain greater salaries if their budgets are larger. Typi- cally, the argument for higher salaries goes through the following process: 1) Salaries should reflect responsibil- ity; 2) Larger departments in either numbers of personnel or in budgets have greater responsibility; 3) Therefore, the managers in these larger departments deserve greater remuneration; 4) Due to the resulting incentive, salaries and numbers of personnel are both pushed upward. This is in contrast to private firms where managers are more likely to be compensated in accord with the profitability 2Considering the issue, the author recently decided to vote in favor o continuing an added tax for schools even though he has no relatives in the area because the added attractiveness of the community with the better schools appeared likely to keep property values sufficiently above what they would otherwise be, even including the negative effect of the tax. 3The author was a Councilman in Amherst, NY and helped promote the idea of aiming at a particular market segment. This was the upper mid- dle income segment which wanted more municipal services and had the capability of paying and willingness to pay for those services. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB  Economies of Scale in Local Government: General Government Spending 267 they generate. Thus, private sector managers have less incentive to hire beyond the optimum number of work- ers. In any organization, budget-maximizing bureaucrats could be a source of inefficiency. First is the likely result that more resources will be devoted to the activity than is optimal from the point of view of the consumers. This, of course, assumes that the bureaucrats exercise some choice in their budgeting. Second is the issue that money will be wasted on a level of activity that may be optimal but is conducted in a wasteful way. In this case, the mix of labor and capital may be skewed toward labor in order to gain more votes. That will be the case for elected offi- cials. A skew toward capital beyond the optimal mix may be the result for a particular bureaucrat. Third is simple waste where output is less than it might be, given the input levels. Private sector firms, as well as governments, may have these characteristics but private firms have a greater incentive to operate efficiently to maximize prof- its. This is particularly the case where a lack of efficiency may result in the demise of the firm but not of the gov- ernment. Agency costs such as the preceding occur in both large and small organizations. However, it is probable that they will be less controllable in a larger organization where monitoring is less easy than it is in a smaller or- ganization. Particularly with regard to shirking, the ease of hiding is probably greater the larger the organization. It is also likely that governments can more readily hide such costs than can private firms where profitability will be adversely affected. It is often possible for a government to contract either with another government or with a private supplier to produce some service that the government wishes to sup- ply to its citizens. It is to be hoped that a municipality would do so when the cost of providing the service that way would be lower than the cost of producing it in- house. Of course, because the contractor will be willing to undertake such a contract only if it expects to receive net benefits as well, such contracting may be expected to happen only when both parties gain. The Town of Am- herst, NY, as one example, provides emergency fire dis- patch to some other municipalities as well as to its own citizens. At the same time, it contracts with a private firm for garbage collection and with a multi-county govern- ment authority to provide potable water and water pipe maintenance services. The opposite, contracting with a smaller organization, does not seem to happen as often. However, it may be the case that a smaller private firm may have lower costs than does the larger municipality simply because private firms tend to be more efficient due to their better incentives. With a smaller municipality that has lower costs, the contracting to provide services to a larger municipality is unlikely because it would raise their costs due to diseconomies of scale. In the case of the overhead costs, there seems to be little contracting in- volved. In the case of overhead costs, contracting out is not generally used by local governments, although in some cases this may be feasible. For example, Amherst, NY, has contracted with a private firm to do property apprais- als. However, it is still the responsibility of the Assessor to actually make the actual assessment of each property. In some other cases, it is not necessary for a municipality to hire full-time employees for such overhead activities. For example, a Town Clerk may be part-time and may even rent a room in his/her house to the town for the Clerk’s office. The Town of Portland, NY, has a part- time Building Inspector as well as a part-time Assessor. If a business survives over time, it would seem to im- ply that it is doing at least enough right so as to continue. It is not losing its customers through overpricing that further implies that it is producing at a low enough cost to be able to continue to compete. For a government, such survival may not imply as much. It has earlier been seen that Buffalo has lost more than half its population over a half-century yet it continues in existence. The in- dication is thus that the period during which the munici- pality may continue is prolonged because of its ability to extract revenues from its customers by compulsion. Ul- timately, of course, when the service value is less than the tax cost by more than the value of the property is when the municipality will cease to exist. Frequently, this period is prolonged by subsidies provided by the State government. That is, the rest of the citizens of the State subsidize the badly performing local government. It could be argued that the quality of the personnel may vary across municipalities with the larger able to better afford the better qualified personnel. Generally, it would be expected that higher salaries would attract the more capable persons. Of course, a municipality should not pay more for a person than that person returns in productivity. A more capable person would presumably be able to command a higher salary due to competition between municipalities than would a less capable person. Only if the amount of work accomplished in a smaller municipality by a person is of more value than the amount that he or she can accomplish in a larger munici- pality will that person be hired by the smaller municipal- ity. Does this give a cost advantage to the larger or to the smaller municipality? There is no necessary reason for one or the other. Since, in a competitive market for peo- ple, the worker will capture most of the gains due to his or her competitive advantage, there won’t be much left for the taxpayers. Further, because of competition be- tween public and private entities, there would be a great- er assurance that a person is paid at least his or her mar- ginal product. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB  Economies of Scale in Local Government: General Government Spending 268 However, it may be that reducing the number of possi- ble competitors by mergers will allow municipalities to obtain monopsony gains in hiring. Since, for the best people, the relevant market is likely to be more than local, perhaps even national, that argument is unlikely to have validity. In addition, the gains to the very well qualified people who may have monopoly gains through fewer competitors may more than offset any monopsony gains. Possibly, the gains available through the monopoly pow- er will attract better people who will then share the bene- fits of their abilities with the customers/taxpayers, par- tially offsetting the losses due to the market power. It is an empirical question as to how this effect, if it exists, may work out in practice. The original location of a city was usually determined because it had location related advantages over alterna- tive sites. Because it typically still has those advantages, it should be able to compete well with any surrounding communities4. However, if it is exploiting those resulting monopoly rents for the advantage of the government functionaries, it may be advantageous for a new city to start up in competition. The customers will then gain the benefits of that competition5. The issue of whether the suburbs harm the city is sometimes raised from the point of view that it takes re- sources away from the city and thus makes the city worse off. Hawkins and Ihrke [5] reviewed numerous studies on this. A preponderance of these found either that there was no effect or that fragmentation decreased costs. Of course, the resources under consideration belong to the consumers, not to the city. The argument, in effect, is the same as that the Berlin Wall which prevented people leaving was useful because the people belonged to East Germany. Staley [6] argues that the cities actually exploit the suburbs. A simple analysis shows that, because resi- dences do not pay their full costs in taxes while busi- nesses and industries pay more than their full costs, sub- urbs which are primarily residential take more of the cost burden while leaving cities with more of the tax base. Filer and Kenny [7] find that city/county consolidation is primarily a way for the poorer city residents to exploit wealthier suburbanites. The next argument, also much used, is that there are economies of scale. This, often without empirical evi- dence that there are such economies, is asserted to re- quire that mergers of municipalities take place in order to save the taxpayers money. This is the issue to be studied in this paper. In many cases, if such economies existed, they could be achieved by contracting out the function either to private industry or to another government. The “Lakewood Plan” is such intergovernmental contracting where Lakewood CA chose to actually produce almost no services while still providing them (see Ostrom, Tie- bout and Warren [8] for a discussion of this). Why the elected officials would not choose to do such contracting if it were that beneficial is not generally asked. It is sim- ply asserted as a reason that the local officials would lose power and perks. On the other side of the issue is the argument that mergers would result in fewer choices on the level of services for the consumers. Nelson [9] argues that con- sumers prefer more choice. Falcone and Lan [10] argue that the more local the government, the better it knows the consumers’ preferences and the better it can adjust to local conditions. Olson [11] also argues for variations in services. The author, while in local elective office, made successful efforts for his local government to aim for a specific market segment, adjusting the levels of services and the consequent taxes to appeal to that particular market. There is a loss accruing to consumers who have heterogeneous preferences when they are forced into a common mold (Procrustes was not a good guy.) The magnitude of this loss in the case of metropolitanization will depend on the degree of these differences in prefer- ence. Another argument against metropolitanization is that the governments will be able to exploit their increased market power to extract gains from the taxpayers. Lynk [12] as well as Vita and Sacher [13] find that mergers of hospitals result in price increases. Abelson [14] and Di- Lorenzo [15] argue for this exploitation hypothesis. Kne- ebone [16] finds that decentralization would reduce costs. Wagner and Weber [17] also find that governments, when able, act as monopolists. To date, however, the em- pirical work has been spotty in this area. Again, this issue will be explored in this paper. 4Buffalo, NY, has lost its port advantage because of the construction o the St. Lawrence Seaway in Canada that allows ships to bypass (and eliminates offloading in) Buffalo. However, it still retains the advan- tages of higher ground, existing infrastructure, and access to the water- front. It ought to be able to compete well with suburbs that are located in swamps or in places where it is otherwise difficult to build. 5There are also some other arguments made as to why local govern- ments should be merged. One is the purported existence of externalities If the smoke from a factory in one municipality blows into a neighbor- ing municipality, the latter suffers uncompensated harm. Shoup [42] made essentially this argument. However, it isn’t the municipality that is harmed but the property owner receiving the smoke. If both the emitter of smoke and the receiver of it are in the same municipality, there is no reason to believe that the decision made by that municipality will be any better than the decision made between the two municipali- ties. If the property rights are well-defined and are enforced, bargaining can take place and will yield the optimal result as per Coase [43]. Numerous papers have been written in regard to whe- ther there are or are not economies of scale in local gov- ernment. The first issue was whether large cities spend more or less per capita than smaller cities. Gabler [18], Zax [19] and Joulfaian and Marlow [20] found that they spend more. Deller [21] reviewed several studies that found that costs increased after consolidation. Rodden [22] found that decentralization decreased costs. Couch, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB  Economies of Scale in Local Government: General Government Spending 269 et al. [23] found for several government activities that there are diseconomies of scale. What about diseconomies of scale? Brempong [24] and Gyapong and Brempong [25] found diseconomies of scale in policing. Ostrom and Whittaker [26] found less satisfaction with police in larger cities. Sjoquist and Walker [27] found economies of scale in property as- sessment. Brynes and Dollery [28] review a number of studies and find that there is no evidence of economies of scale. The next issue was efficiency; residents of larger cities might simply have a preference for a higher level of ser- vices to account for their higher spending. Are larger cities more efficient? Hirsch [29] did not find that con- solidation increased efficiency. Lockwood [30] finds de- centralized government to be more efficient. Oliver [31] finds that citizens monitor larger governments less which could lead to less efficiency. Bardhan [32] also found that devolution of services to local governments resulted in greater efficiency. There are also a number of papers that find U shaped average cost curves. This implies that there is an optimal size for governments. Loehman and Emerson [33], Sha- piro [34] Drake and Simper [35], and Southwick [36] all effectively find such cost curves. This implies econo- mies of scale for smaller municipalities and disecono- mies for larger municipalities. Most past studies assumed that there were either economies or diseconomies over the entire range and used empirical methods that did not allow for the finding of a U shaped cost curve. 3. The Study Design This study will explicitly allow for economies of scale, diseconomies of scale, and a possible U shaped average cost curve. Another important issue to be explicitly con- sidered is whether local governments actually are able to use any market power they may have to exploit their cus- tomers. Both of these issues remain controversial and need careful empirical work. The study, as stated above, will focus on overhead costs. These overhead costs, which are also referred to as general government costs, include all costs of the local government less the following: Education Police Fire Other public safety Health Transportation (highways and mass transit, generally) Economic assistance (public welfare payments) Culture & recreation Utilities (sewers, drainage, water) Other home & community services Each of these excluded costs has more choice embed- ded in it than do the overhead costs. Consequently, it would be necessary to include the amounts (quantities per capita) of those services as well as their costs in terms of the local decisions made. There is much less choice involved in the area of the overhead items. Therefore, there tends to be much less variation in the level of services provided across munici- palities. Major components of these costs include: Assessment/tax collection Zoning/planning Building code enforcement Legal Clerical Legislative/executive Financial/fiscal management In regard to these particular services, it will be pre- sumed that the residents desire mainly to achieve the lowest feasible cost. Because the quality does not differ appreciably (except in the minds of the providers), the lowest cost delivers the lowest tax effects and therefore the highest utility. Of course, if mistakes or errors are made by the providers, that may result in citizen dis- pleasure. However, that is much less likely for these ac- tivities than is concern over the services (excluded here) that provide direct utility to the users/citizenry. It is true, of course, that decisions made by the legisla- tive body may not be optimal according to some of the citizenry. However, the issue there is not generally the cost but rather the choices made by the elected officials. For example, the legislators may approve of some re- zoning which is opposed by some of the people. While some of the citizens would like to replace some of the elected officials after such decisions, typically decisions are made by the elected officials with the idea in mind of maximizing the proportion of the voters who will ap- prove the decision6. Overhead costs and the associated costs are generally desired to be minimized since there is no constituency for increasing them as there is for rec- reational service, for example. It will be supposed that there is an average cost per capita, AC, function for the overhead services that in- cludes the population of the municipality and the market power of the government of the municipality. Let that function be: ACfPop, HH, X (1) where Pop is the population, HH is a measure of the market power, and X is other variables. The first deriva- tive with respect to population of the function chosen should have the capability of being of one sign at one 6In politics, of course, “friends come and go while enemies accumu- late”. Thus, even accuracy in choosing decisions according to pleasing the electorate may result in eventually losing elections. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB  Economies of Scale in Local Government: General Government Spending 270 population level and of another sign at another popula- tion level. Two functions that have this capability are: ACabPopc1 PopdHHeX (2) ln ACab*ln Popc*ln Popln Pop d*ln HHe*HH (3) The derivative of Equation (2) with respect to Pop is; 2 ACPopbc1 Pop (2a) If Pop is large, the value of the derivative approaches b, which can be either positive or negative, implying either diseconomies or economies of scale, respectively. At a lower value of Pop, the value approaches b – c, which will be positive if b > 0 and c < 0 and will be negative if b < 0 and c > 0. If b and c are both positive or are both negative, the issue of economies or diseconomies will depend on the relative absolute magnitudes. Thus, a vari- ety of alternatives can be accommodated. Suppose that both b and c are positive in Equation (2). Then, there exists an optimum population size to mini- mize AC. That population is: 0.5 Popcb (2b) With the translog function, Equation (3), the derivative with respect to Pop is: ACPopb2clnPopPop (3a) If b > 0 and c > 0, the result is diseconomies of scale and, if b < 0 and c < 0, the result is economies of scale. At relatively (compared to b/c) small values for Pop, diseconomies result from b > 0 and economies result from b < 0. At large values for Pop relative to b/c, dis- economies result from c > 0 and economies result from c < 0. Again, a variety of alternative outcomes can be accom- modated. Suppose that Equation (3) is estimated and that b < 0 while c > 0. Then the optimal population (minimum AC) becomes; Popexpb 2c (3b) Now for the variables denoted as X. One is a dummy variable for City. In New York State, Towns and Cities have mutually exclusive territories and, in the aggregate, include all lands in the state. Cities have different laws applicable to them than do Towns; thus, the variable to control for that difference. One interesting difference might be the proportion of power vested in district coun- cilmen that is generally higher in cities since most coun- cilmen are elected at-large in towns7. Another issue is presented by the various years. The data are for a number of years. They are adjusted for Consumer Price Index (CPI) levels for the various years to be in 2004 dollars. Nonetheless, there may be other differences to be accounted for over the different years. Thus, dummy variables for the years may need to be in- cluded to account for these differences8. 4. Data The towns and cities in New York State will comprise the data set. The governments involved are the truly local governments, towns and cities9. If one lives in New York State, one lives in either a city or in a town. New York City will be left out of the data set because it is so sub- stantially different as would skew any results10. The rea- son for using a single state is to ensure that all of the mu- nicipalities operate under a single legal system and state- imposed set of constraints. Each observation is for a sin- gle town or city in a particular year11. As an example of how the set is consistent is that New York State allows (essentially requires) all the municipalities to have their employees be represented by unions. How they deal with the unions is then controlled by State regulations that are relatively uniform across the state. There are approximately 932 towns and 61 cities in New York outside of New York City. This includes all of the land area of the state, again not including New York City. This follows from the design of the governments in New York where every parcel of land is in either a city or a town. There are also villages, but these are each in- cluded in one or more towns and therefore are not truly separate governments12. The years for which these data are readily available include 1977 through 2004. The source is various (on- line) years of “Financial Data for Local Governments” from the New York State Comptroller’s Office. Because the original source is reports from the Towns and Cities themselves, there are occasional missing data where a municipality was late in reporting or did not report. Po- tentially, there may be up to 26,811 observations. In practice, because of missing observations and missing 8The values for these estimated coefficients will not be reported since they are not of interest here. 9In New York State, as in most northern and eastern states, townships (towns) are the most local municipalities while in the western and southern states, the county is the most local. 10Over 42 percent of the population of New York State resided in New York City in 2004 (see US Statistical Abstract 2006, p.21 and p.34). Further, the total spending per capita in NYC in 2004 was over $7900 while for the rest of the local governments, the total spending per cap- ita was just under $4,000 or about half as much. 11There are also villages in New York. These overlap or are included in towns. Generally, they provide services not provided or provided at a lower level by the overlapping town(s). 12It might even be argued that homeowners’ associations act as gov- ernments, providing services and levying taxes (fees) on members. 7It has been shown by Southwick [41] that greater power for ward councilmen results in higher spending levels. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB  Economies of Scale in Local Government: General Government Spending 271 items in some reports, there are fewer13. New York City, as noted above, is not included in the data set. The population figures are only available accurately for the census reports every 10 years. In order to compute the population figures for each community in the other years, it was necessary to interpolate between the census figures. For the years after the 2000 census, the popula- tion for each community was computed using the as- sumption that it had continued to change at the same an- nual amount it had changed from 1990 to 2000. Market power is defined as the Herfindahl-Hirschman (HH) Index with the county as the market area. The population in each Town and City in that county as a pro- portion of the total county population is squared and multiplied by 10,000 to give the HH value for that mu- nicipality. The total of these HH values across the Towns and Cities in that county gives the relevant HH number for the county and measures the market power for the communities in that county. It is thus assumed that peo- ple have a choice of communities only within their coun- ty14. All the financial data were adjusted by the CPI to 2004 values. Thus, the per capita financial values were ad- justed as well. The characteristics of each of these variables are given in Table 1. The dependent variable, either LNRGP or RGGPOP, has the fewest observations and so will determine the number of observations used in the regressions. The largest city (not including NYC) in the census of 2000 was Buffalo with 292,648 people and the largest town was Hempstead with 755,924. The smallest city was Sherrill with 3147 and the smallest town was Red House with 38. The median city was Plattsburgh with 18,816 and the median town was between Caroline at 2910 and Pamelia at 2897. The average city size in 2000 was 37,146 and the average town was 9326. Table 2 gives the correlations among the variables used. The only substantial concern is the high correlation be- tween LNPOP and LNPLNP since both are to be used as independent variables in a regression. However, with POP and POP1 essentially uncorrelated in the corre- sponding quadratic (non-translog) regression, this con- cern should be alleviated. Further, correlation among in- dependent variables has the effect of increasing the stan- dard errors and so should only have the effect of reduc- ing the likelihood of finding the effect which is looked for. Also, note that the correlation between City and Pop is only 0.18 so the larger population municipalities are not necessarily cities. Note that the HH Index is not highly correlated with municipality size. This suggests that a higher population for one municipality generally tends to show up with other municipalities in the county also having higher po- pulations15. That would be consistent with municipali- ties responding to market forces by seeking market ni- ches within their counties. 5. Results The following three Tables 3(a)-(c), are the results of the regressions using the Average Cost per Capita of the lo- cal governments over the 28-year time period as the de- pendent variable. As noted earlier, all of the financial variables have been adjusted by the CPI to 2004 dollars. Table 3(a) is OLS, Table 3(b) uses Year dummies (the coefficients of which are not reported), and Table 3(c) computes a frontier result16. These are all done using LIMDEP [37]. Also included at the bottom of each table is the im- plied population for the lowest average cost municipality for that regression, where such a computation is possible. The number of observations with complete data in each of the above regressions is 27,509. Thus, there is a large number for degrees of freedom in each case. The very substantial t-statistics that show that each of the variables is highly significant in each equation is partly the result of the large number of observations. Still, the significance of the results tends to lead to the conclusion that these equations truly are meaningful in the attempt to explain the variation in the average cost data. Further, the average cost regressions do appear to explain a substantial part of that variation. The estimated lowest cost populations appear to be somewhere between 17,000 and 21,000. The frontier regressions are interesting because, unlike the other regressions, they are estimates of the minimum possible costs. The fact that each of the coefficients in these regressions is significant gives a good deal of con- fidence in the results. Further, the result that the mini- mum cost population estimates are very like the other minimum cost population estimates from the OLS and panel regressions gives more support to the U-shape of the cost function and the level of the true optimum popu- lation. 13There are also fewer observations because there were only 930 Towns at the beginning of the period while there were 932 at the end of the eriod. 14Of course, some people do commute across county lines. In a similar fashion, some people buy office supplies from other than the big three ox stores, Office Max, Office Depot, and Staples. However, as a boundary must be set somewhere, as the FTC did with the big three, so this paper will use the county which had its boundaries set for effi- ciency some time ago. It can be inferred with some confidence that very small 15The correlation between the population of the county and the HH Index is 0.4. 16The distribution is assumed to be half-normal. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB  Economies of Scale in Local Government: General Government Spending Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB 272 Table 1. Variable characteristics. Name Variable Mean Std. Dev. Minimum Maximum Cases Pop Population 10,795 37,096 1 768,052 27775 Pop1 1/Population 6.11E−04 7.05E−03 1.30E−06 1 27775 HH HH Index 1214.8 580.0 565.2 3986.6 27799 RGGPop Real Gen. Gov. Exp/Pop 99.13 101.14 13.70 2,475.97 27509 LnRGP ln(RGGPOp) 4.3610 0.6170 2.6171 7.8144 27509 LnPop ln(POp) 8.2030 1.2728 0 13.5516 27775 LnPLNP ln(POp)*ln(POp) 68.9088 21.9661 0 183.6462 27775 LNH ln(HH) 7.0078 0.4206 6.3372 8.2907 27799 Year Year 1990.5 8.1 1977.0 2004.0 27799 CPI CPI 130.23 36.99 60.60 188.90 27799 City City = 1, Town = 0 6.14E−02 0.2401 0 1 27799 Table 2. Correlations among variables. Pop Pop1 HH RGGPopLnRGP LnPop LnPLNP LNH Pop 1.00 −0.13 0.32 0.05 0.08 0.56 0.63 0.25 Pop1 −0.13 1.00 −0.10 0.43 0.32 −0.58 −0.51 −0.09 HH 0.32 −0.10 1.00 0.04 0.05 0.30 0.32 0.97 RGGPop 0.05 0.43 0.04 1.00 0.84 −0.13 −0.08 0.04 LnRGP 0.08 0.32 0.05 0.84 1.00 −0.08 −0.03 0.04 LnPop 0.56 −0.58 0.30 −0.13 −0.08 1.00 0.99 0.26 LnPLNP 0.63 −0.51 0.32 −0.08 −0.03 0.99 1.00 0.28 LNH 0.25 −0.09 0.97 0.04 0.04 0.26 0.28 1.00 Year 0.01 −0.04 −0.06 0.14 0.22 0.05 0.05 −0.08 CPI 0.02 −0.04 −0.06 0.14 0.22 0.05 0.05 −0.07 City 0.18 −0.12 0.05 0.21 0.31 0.36 0.37 0.04 communities have higher average costs because of their size and that larger communities have higher average costs because of their size. While the mean population is only about half the optimal size for this function, advo- cacy of mergers for many communities is not necessarily warranted17. Next, the results for the estimated translog cost func- tions are reported in Tables 4(a)-(c). These are the OLS, panel with dummies for the years, and frontier regres- sions as above. The number of complete observations is 27,509. All of the estimated coefficients are highly significant, except for the ln(HH Index) in Tables 4(a) and (c) where City is not included. The optimal population here is found to be somewhere between 6300 and 11,000. In every one of the above 27 regressions, the result is a U-shaped curve, implying that there exists an optimal sized population to minimize the average per capita cost. It can also be concluded that greater market power does result in higher costs, thus suggesting that local governments do seek to exploit their market power to extract rents from the public. Mergers that would in- crease such market power would result in increased ex- ploitation even if the resulting population were to remain near the optimal. Further, the results show that the market power, as measured by the county HH Index, is a significant factor increasing the average cost. Apparently the market power 17Optimal populations for other municipal functions would also be relevant.  Economies of Scale in Local Government: General Government Spending 273 Table 3. (a) OLS regressions dependent variable real Per Capita Gen. Gov. Exp. t-statistics below coefficients; (b) Pa- nel regressions dependent variable real Per Capita Gen. Gov. Exp. t-statistics below coefficients; (c) Frontier regres- sions dependent variable real Per Capita Gen. Gov. Exp. t-statistics below coefficien ts . (a) Population 2.91E−04 1.63E−04 2.47E−04 1.15E−04 19.6 11.2 15.8 7.6 1/Population 43,038 45,591 43,372 45,954 79.3 87.1 79.8 87.8 City 109.62 109.92 49.0 49.2 HH Index 9.32E−03 9.93E−03 9.3 10.3 Constant 72.456 65.657 61.430 53.888 110.7 102.1 45.4 41.3 Adjusted R2 0.188 0.253 0.191 0.256 Min Cost Pop 12,157 16,723 13,256 19,958 (b) Population 2.91E−04 1.62E−04 2.37E−04 1.05E−04 19.9 11.4 15.4 7.0 1/Population 43,497 46,058 43,920 46,513 81.3 89.5 82.1 90.4 City 109.85 110.22 49.9 50.2 HH Index 1.14E−02 1.20E−02 11.5 12.7 Adjusted R2 0.213 0.279 0.217 0.283 Min Cost Pop 12,230 16,844 13,624 21,074 (c) Population 1.41E−04 1.34E−04 9.62E−05 1.07E−04 40.1 28.3 20.7 18.5 1/Population 43,036 45,590 43,372 45,953 445.3 442.6 468.1 453.6 City 96.093 96.310 67.4 68.8 HH Index 9.74E−03 5.63E−03 13.0 7.5 Constant −3.82 −7.44 −14.99 −13.98 −7.6 −13.8 −14.8 −13.8 Min cost Pop 17,457 18,466 21,237 20,730 effect does decrease with increasing population, but not very substantially so. Market power still operates to in- crease costs at every population level. It is again the case that there is a U-shaped average cost curve for both the OLS and panel regressions and for the frontier regression. Again, the population optima as calculated are very similar across the methods. The next analytical test was to adjust the relevant es- timated coefficients by two standard errors and to re- compute the optimal populations. This, in effect, yields the approximate 95 percent confidence interval for the optimal population for each equation18. The purpose is a sensitivity test to see how sensitive the optimal popula- tion measures are to the estimated coefficient. The results are shown in Table 5. These results in Table 5 yield the important conclu- sion with respect to general government expenditures (overhead) that there is consistently to be found an opti- mal population size. Further, that optimal population is estimated to be somewhere between 4600 and 25,200 people. Mergers that result in a population of over 25,200 people will generally lead to increases in cost. It will depend on whether greater confidence is placed in the translog or in the quadratic cost function as to whether the efficient size is toward the lower end or the higher end of these ranges. A graph of the average and efficient size, based on the translog equation with only population and city variables, is given in Figure 1 for the average municipality. Note that the HH Index, measuring market power, has been left out of the equation creating this graph. That is because greater market power does not require higher costs; it simply allows the municipality to get away with more exploitation of its customers. It appears that the potential minimum costs are substantially lower than the actual average costs. That suggests, at least from the point of view of the consumers, a substantial level of inefficiency for the average municipality. Of course, the efficient frontier, because it uses the best results in the sample, will always look better than the average. How- ever, if some municipalities have lower costs, it can cer- tainly be reasonably inferred that such results are possi- ble. The major result shown in Figure 1 is that both the average and the efficient frontier show declining average costs out to a particular population level and rising aver- age costs for larger communities. This should not be sur- prising because the same result is found repeatedly in the private sector as well. In fact, it should be found there if there are more than a few firms in the industry because otherwise they would not all have been able to survive. 18While only one of the estimated equations in each regression set is tested in this way, it will make little difference if more were to be treated in the same way. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB  Economies of Scale in Local Government: General Government Spending Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB 274 Table 4. (a) Translog regressions (OLS) dependent variable ln(Real Per Capita Gen. Gov. Exp.) t-statistics below coefficients; (b) Translog regressions (Panel) dependent variable ln(Real Per Capita Gen. Gov. Exp.) t-statistics below coefficients; (c) Translog regressions (Frontier) dependent variable ln(Real Per Capita Gen. Gov. Exp.) t-statistics below coefficients. (a) ln(Pop) −1.6275 −1.5174 −1.6237 −1.5004 −0.8099 −71.4 −70.8 −70.8 −69.6 −22.1 ln(Pop)*ln(Pop) 0.0929 0.0828 0.0926 0.0815 0.0980 70.5 66.5 69.6 64.8 68.2 City 0.8947 0.9029 0.8537 62.0 62.4 59.0 ln(HH Index) 0.0129 0.0546 1.1998 1.5 6.8 24.0 ln(Pop)*ln(HH) −0.1360 −23.2 Constant 11.3144 11.0515 11.2128 10.6186 3.6238 116.1 120.9 94.7 95.5 11.3 Adjusted R2 0.157 0.260 0.157 0.261 0.276 Min Cost Pop 6398 9581 6441 9994 8019 (b) ln(Pop) −1.6497 −1.5392 −1.6377 −1.5133 −0.8018 −75.2 −75.2 −74.3 −73.6 −23.0 ln(Pop)*ln(Pop) 0.0940 0.0838 0.0930 0.0818 0.0989 74.1 70.5 72.7 68.2 72.3 City 0.9003 0.9132 0.8625 65.3 66.2 62.5 ln(HH Index) 0.0421 0.0850 1.2655 5.1 11.1 26.6 ln(Pop)*ln(HH) −0.1401 −25.1 Adjusted R2 0.220 0.325 0.221 0.328 0.343 Min Cost Pop 6494 9720 6638 10,385 8240 (c) ln(Pop) −1.3968 −1.3792 −1.3916 −1.3690 −0.9267 −99.1 −99.8 −93.7 −95.9 −34.7 ln(Pop)*ln(Pop) 0.0778 0.0744 0.0774 0.0736 0.0877 103.7 98.8 95.6 93.1 76.2 City 0.9804 0.9835 0.9452 72.3 73.1 66.2 ln(HH Index) 0.0146 0.0339 0.8263 1.9 4.8 20.3 ln(Pop)*ln(HH) −0.0951 −19.6 Constant 9.8172 9.9013 9.6994 9.6355 4.9795 148.6 156.7 99.7 108.6 19.8 Min Cost Pop 7887 10,608 7979 10,943 8842  Economies of Scale in Local Government: General Government Spending 275 Table 5. Range of optimal populations adjusting coefficients by 2 Std. err or s. From Table Maximum Minimum 3a 23,516 11,433 3b 25,194 11,513 3c 22,392 17,000 4a 13,411 4648 4b 13,392 4932 4c 13,751 5551 Average 18,609 9180 $0 $10 $20 $30 $40 $50 $60 $70 $80 $90 $100 05,00010,000 15,000 20,000 25,000 30,000 35,000 40,000 45,000 50,000 Average Cost Per Capita Population Average Frontier Figure 1. Translog-ln(Pop), ln(Pop)*ln(Pop), city. In the public sector, on the other hand, inefficiency is not always followed by the demise of the firm because it can simply raise taxes. Now, look at the difference between the average of the average cost results and the lowest of the average cost results. This data is derived from the same data as Figure 1. In percentage terms, this result is shown in Figure 2. This is a rather dramatic result, showing that the pro- portion of inefficiency increases for larger communities as well as does the level of cost. While this result is partly driven by the use of the same general form of equation for both equations estimated, that is by no means the only driver. The graph in Figure 2 could be declining over the entire range or it could be increasing over the entire range using the same basic formula; all that would have been required is for the estimates to be somewhat different19. The actual minimum inefficiency is at a population level below the population where the 75% 80% 85% 90% 95% 100% 05,00010,000 15,000 20,00025,000 30,000 35,000 40,000 45,00050,000 Percentage Excess Spending Population Figure 2. Average percent above efficient. minimum of the average cost curve is achieved. Increas- ing relative inefficiency as population increases is the average result. Partly, of course, this may be due to the market power effect; greater inefficiency may be due to the exploitation of the consumers. 6. Conclusions For the major issue in the introduction, mergers, it would be appropriately inferred here, as well as in the quadratic tests, that mergers are generally contraindicated. In fact, because the computed optimal populations in the translog tests is less than in the quadratic tests, the appropriate sizes of communities where mergers may be cost-reduc- ing is smaller. The conclusion reached in regard to the market power effect is still operative; even if the sizes appear appropriate for merger consideration, the ex- ploitative results of a merger for all the communities in a county may well imply that a merger is socially undesir- able. The bottom line in all of this appears to be that, for a very wide population range as seen in New York State, the average cost curves for the core municipal functions are U-shaped. Further, the population level at which the cost is minimized is relatively small. Therefore, it can be confidently determined that it follows that mergers of municipalities of over 25,000 population should be dis- couraged. Further, it appears that the merger of two mu- nicipalities each of 12,500 population would also not be cost effective using any of the estimates. The existing average population size of 10,795 is fairly close to the minimum cost estimate with either the quad- ratic or the translog formulation. This would seem to imply that the answer to our initial question is, that gen- erally, mergers will not reduce overhead costs. In fact, it would seem that many of the municipalities have grown to such an extent that division into two or more might be 19An artificial example was created in which the Averages and the Frontier were U-shaped and the Percent Inefficiency increased over the range at least up to 200,000 population by tweaking the estimated coefficient values just to see if this was possible. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB  Economies of Scale in Local Government: General Government Spending 276 warranted. Savas [38] finds that many of the services covered in the above are becoming privatized. These included accounting, financial & legal, human resources administration, information technology, risk management, planning & building, and building maintenance. This ef- fect is another way of lowering costs where municipali- ties are too large. In addition, the more market power that municipalities in a county have, the higher will be the costs per capita. Any mergers would have the effect of increasing the HH Index. Using the average HH Index of 1215, the ap- proximate implied percentages of population in each mu- nicipality if all were equal would be 12.5 percent. Merg- ing any two of these would increase the HH Index by 313, or 25 percent. This would increase average costs accord- ing to the estimates in Table 3 by about $3.10 or more than 3 percent. From the point of view of the consumer, although not necessarily of the municipal employee, this is pure waste. It is an extra exploitation of the consumer, enabled by the extra market power. It wouldn’t be as bad if there were 10 communities each with 10 percent of the population and two merged. Then, the increase would be only about $2.00. The Federal Trade Commission promulgated rules in 1992 [39] pertaining to mergers in the private sector and again referred to these in 2006 [40]. Essentially, these were that 1) in industries with HH Indexes under 1000 after the merger there would be no challenge; 2) in in- dustries with HH Indexes between 1000 and 1800, chal- lenges would be made to mergers which increased the HH Index by more than 100; and 3) in industries with HH Indexes over 1800, challenges would result if the HH Index would be increased by more than 5020. In the above examples, this would imply that, were these muni- cipalities in the private sector, the mergers given would be challenged as injurious to the consumers. It needs to be noted that mergers that raise the HH In- dex would increase the market power for all of the firms or, in this case, municipalities in the relevant market, here the county. That is, a merger of two municipalities, as in the first example, which raises the per capita cost by $3.10 does so not only for the merging municipalities but also for the rest of the municipalities in that county. Thus, the taxpayers in any of the municipalities have an interest in opposing the merger of any of the other municipalities in their county. Another meaningful difference is whether the munici- pality is a City or a Town. The efficient frontier increases for Cities by $90 per capita or by about 140 percent, de- pending on the equation form used. Further, the average result increases by about $110 or 167 percent. Thus, the City not only has an intrinsically higher cost, but it also adds to the level of exploitation of the customers. This is undoubtedly due to differing N.Y. State laws regulating Towns and Cities. It may also be affected by cities being more likely to have legislative bodies from districts than do towns (see Southwick, [41]). For future research, the economies of scale of the ex- cluded municipal functions need to be individually stud- ied. Because the quantity levels of other functions are more subject to the desires of the voters and because their quality may also vary substantially, it will require simultaneous equations analysis for these. Further, where contracting out exists, some different method of handling this will be needed as well. It is interesting to speculate, given the above results, on the question of whether state and national govern- ments, due to their greater sizes, may be even less effi- cient than are the local governments. That possibility should be studied before deciding to have these larger governments take on the responsibilities usually associ- ated with more local governments. REFERENCES [1] C. M. Tiebout, “A Pure Theory of Local Public Expendi- tures,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 64, No. 5, 1960, pp. 416-424. doi:10.1086/257839 [2] D. Epple, T. Romer and H. Sieg, “Interjurisdictional Sort- ing and Majority Rule: An Empirical Analysis,” Eco- nometrica, Vol. 69, No. 6, 2001, pp. 1437-1465. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2692263 [3] S. L. Percy, B. W. Hawkins and P. E. Maier, “Revisiting Tiebout: Moving Rationales and Interjurisdictional Relo- cation,” Publius, Vol. 25, No. 4, 1995, pp. 1-17. [4] G. Brennan and J. M. Buchanan, “Towards a Tax Consti- tution for Leviathan,” Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 8, No. 3, 1977, pp. 255-273. doi:10.1016/0047-2727(77)90001-9 [5] B. W. Hawkins and D. M. Ihrke, “Reexamining the Sub- urban Exploitation Thesis in American Metropolitan Ar- eas,” Publius, Vol. 29, No. 3, 1999, pp. 109-121. [6] S. Staley, “Policy Fax Essay: Fatal Flaws in David Rusk’s Cities without Suburbs,” Indiana Policy Review Founda- tion, 5 April 1996. [7] J. E. Filer and L. W. Kenny, “Voter Reaction to City- County Consolidation Referenda,” Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 23, No. 1, 1980, pp. 179-190. doi:10.1086/466958 [8] V. Ostrom, C. M. Tiebout and R. Warren, “The Organiza- tion of Government in Metropolitan Areas: A Theoretical Inquiry,” The American Political Science Review, Vol. 55, No. 4, 1961, pp. 831-842. doi:10.2307/1952530 [9] M. A. Nelson, “Decentralization of the Subnational Pub- lic Sector: An Empirical Analysis of the Determinants of Local Government Structure in Metropolitan Areas in the 20These still remain as guidelines, albeit with somewhat less rigidity. See also the FTC and DOJ “Commentary on the Horizontal Merger Guidelines”, March 2006 [40]. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB  Economies of Scale in Local Government: General Government Spending 277 US,” Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 57, No. 2, 1990, pp. 443-457. [10] S. Falcone and Z. Y. Lan, “Intergovernmental Relations and Productivity,” Public Administration Review, Vol. 57, No. 4, 1997, pp. 319-322. [11] M. Olson, “Toward a More General Theory of Govern- mental Structure,” The American Economic Review, Vol. 76, No. 2, 1986, pp. 120-125. [12] W. J. Lynk, “Nonprofit Hospital Mergers and the Exer- cise of Market Power,” Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 38, No. 2, 1995, pp. 437-461. doi:10.1086/467338 [13] M. G. Vita and S. Sacher, “The Competitive Effects of Not-for-Profit Hospital Mergers: A Case Study,” The Jour- nal of Industrial Economics, Vol. 49, No. 1, 2001, pp. 63-84. doi:10.1111/1467-6451.00138 [14] P. W. Abelson, “Some Benefits of Small Local Govern- ment Areas,” Pu blius, Vol. 11, No. 1, 1981, pp. 129-140. [15] T. J. DiLorenzo, “George Stigler and the Myth of Effi- cient Government,” Journal of Libertarian Studies, Vol. 16, No. 4, 2002, pp. 55-73. [16] D. D. Kneebone, “Centralization and the Size of Govern- ment in Canada,” Applied Economics, Vol. 24, No. 12, 1992, pp. 1293-1298. [17] R. E. Wagner and W. E. Weber, “Competition, Monopoly, and the Organization of Government in Metropolitan Ar- eas,” Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 18, No. 3, 1975, pp. 661-684. [18] L. R. Gabler, “Population Size as a Determinant of City Expenditures and Employment: Some Further Evidence,” Land Economics, Vol. 47, No. 2, 1971, pp. 130-138. doi:10.2307/3145454 [19] J. S. Zax, “Is There a Leviathan in Your Neighborhood?” The American Economic Review, Vol. 79, No. 3, 1989, pp. 560-567. [20] D. Joulfaian and M. L. Marlow, “Government Size and Decentralization: Evidence from Disaggregated Data,” Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 56, No. 4, 1990, pp. 1094-1102. doi:10.2307/1059894 [21] S. C. Deller, “Local Government Structure, Devolution, and Privatization,” Review of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 20, No. 1, 1998, pp. 135-154. doi:10.2307/1349539 [22] J. Rodden, “Reviving Leviathan: Fiscal Federalism and the Growth of Government,” International Organization, Vol. 57, No. 4, 2003, pp. 695-729. doi:10.1017/S0020818303574021 [23] J. F. Couch, B. A. King, C. H. Gossett and J. B. Parris, “Economies of Scale and the Provision of Public Goods by Municipalities,” Journal of Economics and Economic Education Research, Vol. 5, No. 3, 2004, pp. 69-79. [24] K. G. Brempong, “Economies of Scale and Municipal Po- lice Services: The Case of Florida,” The Review of Eco- nomics and Statistics, Vol. 69, No. 2, 1987, pp. 352-356. doi:10.2307/1927244 [25] A. O. Gyapong and K. G. Brempong, “Factor Substitution, Price Elasticity of Factor Demand and Returns to Scale in Police Production: Evidence from Michigan,” Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 54, No. 4, 1988, 16 pages. [26] E. Ostrom and G. P. Whitaker, “Does Local Community Control of Police Make a Difference? Some Preliminary Findings,” American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 17, No. 1, 1973, pp. 48-76. doi:10.2307/2110474 [27] D. L. Sjoquist and M. B. Walker, “Economies of Scale in Property Tax Assessment,” National Tax Journal, Vol. 52, No. 2, 1999, pp. 207-220. [28] J. Byrnes and B. Dollery, “Do Economies of Scale Exist in Australian Local Government? A Review of the Em- pirical Evidence,” Working Paper Series in Economics, University of New England School of Economics, Armi- dale, No. 2002-2. [29] W. Hirsch, “Expenditure Implications of Metropolitan Growth and Consolidation,” Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 41, No. 3, 1959, pp. 232-241. doi:10.2307/1927450 [30] B. Lockwood, “Distributive Politics and the Costs of Centralization,” The Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 69, No. 2, 2002, pp. 313-337. [31] J. E. Oliver, “City Size and Civic Involvement in Metro- politan America,” The American Political Science Review, Vol. 94, No. 2, 2000, pp. 361-373. doi:10.2307/2586017 [32] P. Bardhan, “Decentralization of Governance and Devel- opment,” The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 16, No. 4, 2002, pp. 185-205. doi:10.1257/089533002320951037 [33] E. Loehman and R. Emerson, “A Simultaneous Equation Model of Local Government Expenditure Decisions,” Land Economics, Vol. 61, No. 4, 1985, pp. 419-432. [34] H. Shapiro, “Economies of Scale and Local Government Finance,” Land Economics, Vol. 39, No. 2, 1963, pp. 175-186. [35] L. Drake and R. Simper, “X-Efficiency and Scale Econo- mies in Policing: A Comparative Study Using the Distri- bution Free Approach and DEA,” Applied Economics, Vol. 34, No. 15, 2002, 12 pages. [36] L. Southwick Jr., “Economies of Scale and Market Power in Policing,” Managerial and Decision Economics, Vol. 26, No. 8, 2005, pp. 461-473. doi:10.1002/mde.1230 [37] W. H. Greene, “LIMDEP, v. 8.0,” Econometric Software, Inc., Plainview, 2002. [38] E. S. Savas, “Privatization and Public-Private Partner- ships,” Chatham House, New Yor, 2000, pp. 72-73. [39] Federal Trade Commission, “1992 Horizontal Merger Guidelines,” 1992. http://www.ftc.gov/bc/docs/horizmer.htm [40] Federal Trade Commission and US Department of Justice, “Commentary on the Horizontal Merger Guidelines,” March 2006. http://www.ftc.gov/os/2006/03/CommentaryontheHorizo ntalMergerGuidelinesMarch2006.pdf [41] L. Southwick Jr., “Local Government Spending and At- Large versus District Representation: Do Wards Result in More Pork?” Economics and Politics, Vol. 7, No. 2, 1997, pp. 173-203. doi:10.1111/1468-0343.00027 [42] D. C. Shoup, “Effects of Suboptimization on Urban Gov- ernment Decision Making,” Proceedings of the Twenty- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB  Economies of Scale in Local Government: General Government Spending Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB 278 Ninth Annual Meeting of the American Finance Associa- tion, Detroit, 28-30 December 1970, pp. 547-564. [43] R. H. Coase, “The Problem of Social Cost,” Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 3, No. 1, 1960, pp. 1-44. doi:10.1086/466560

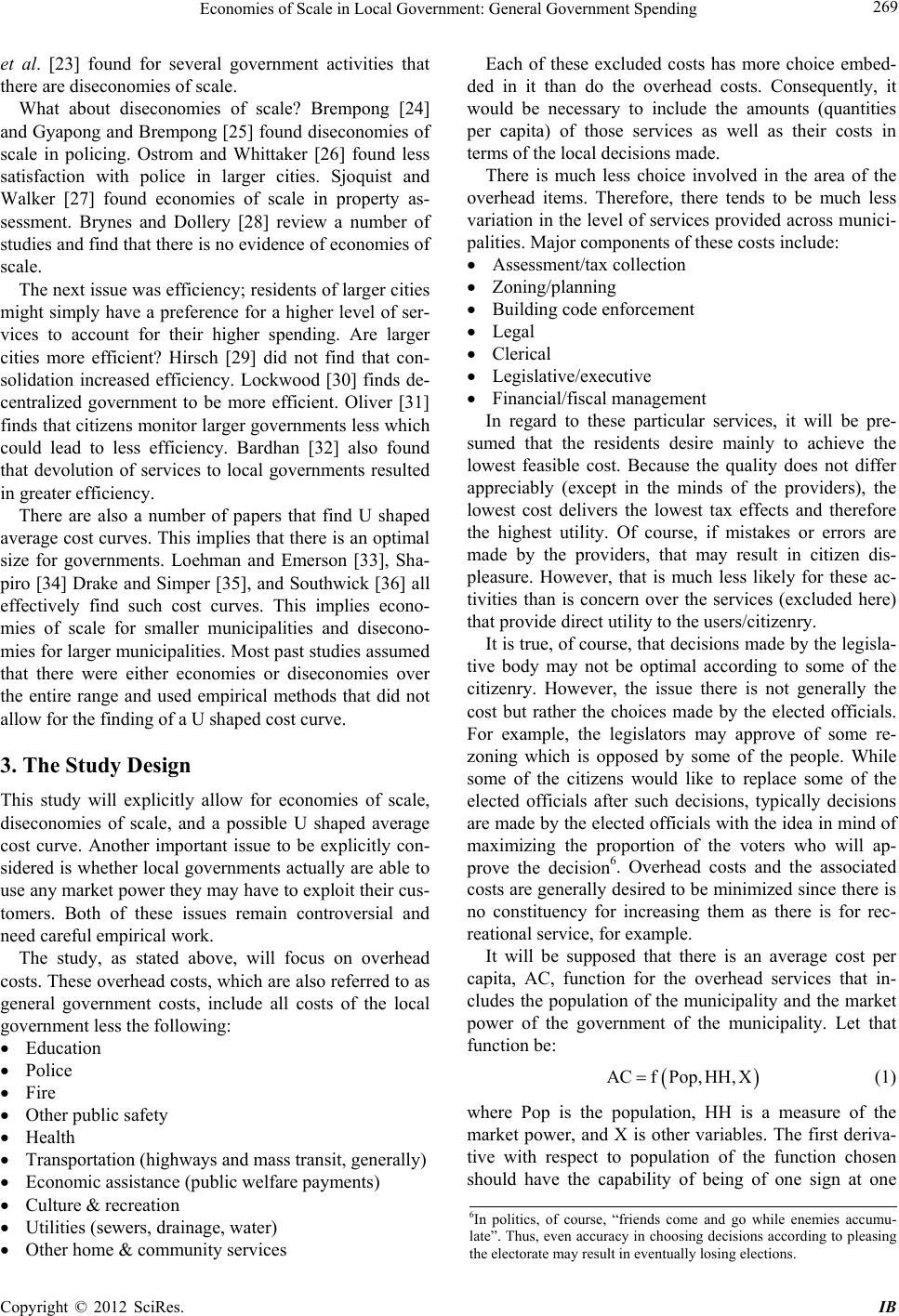

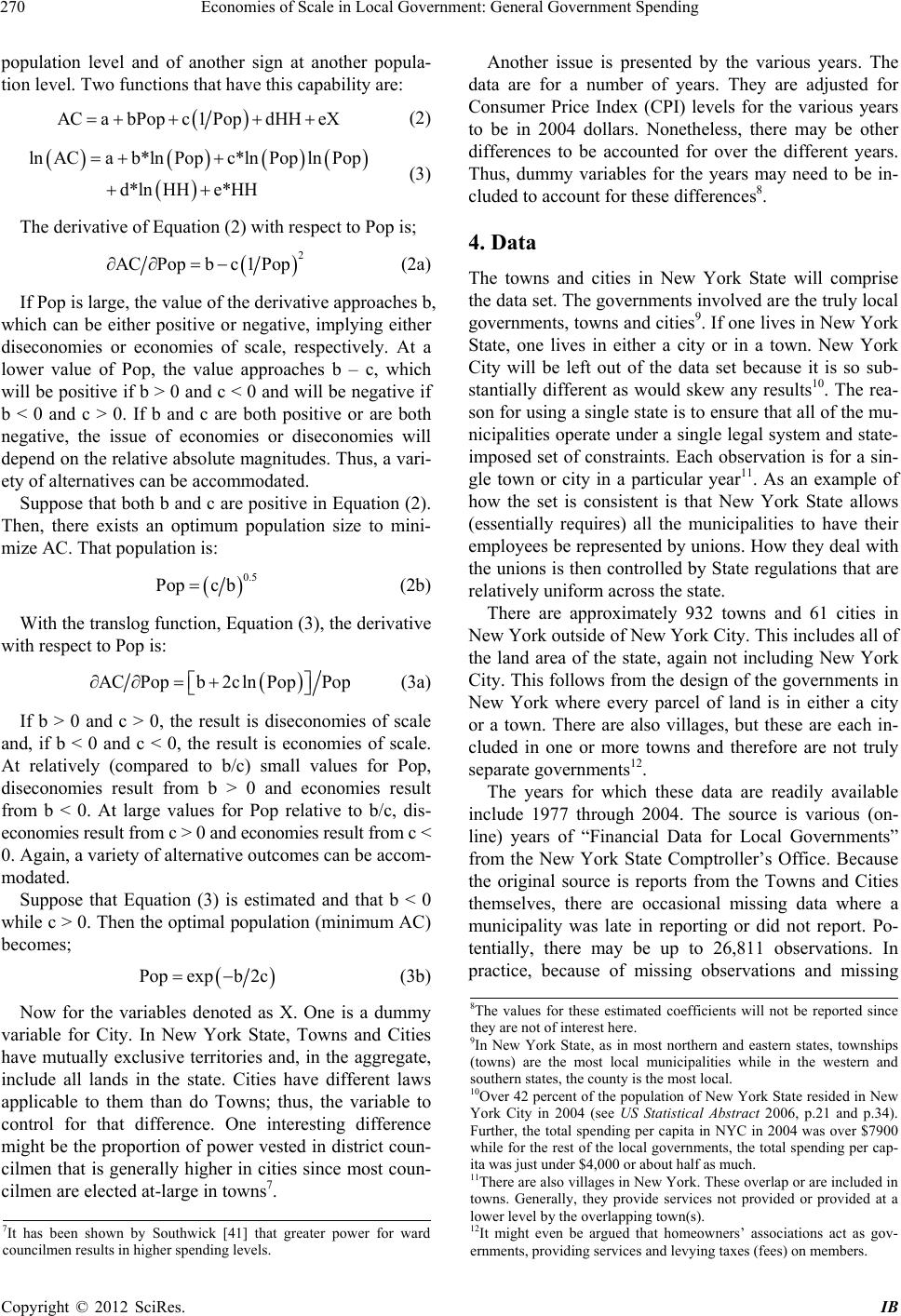

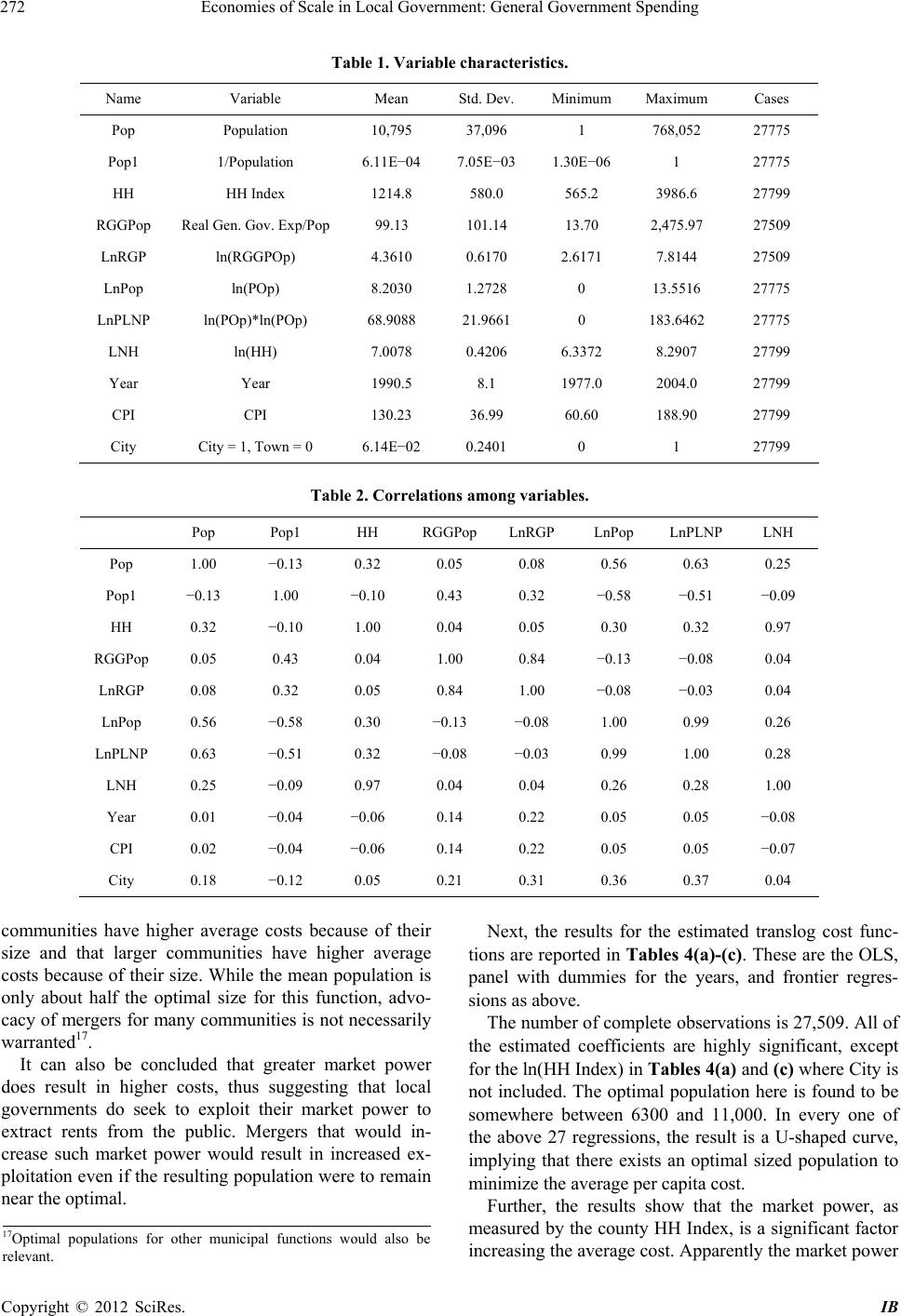

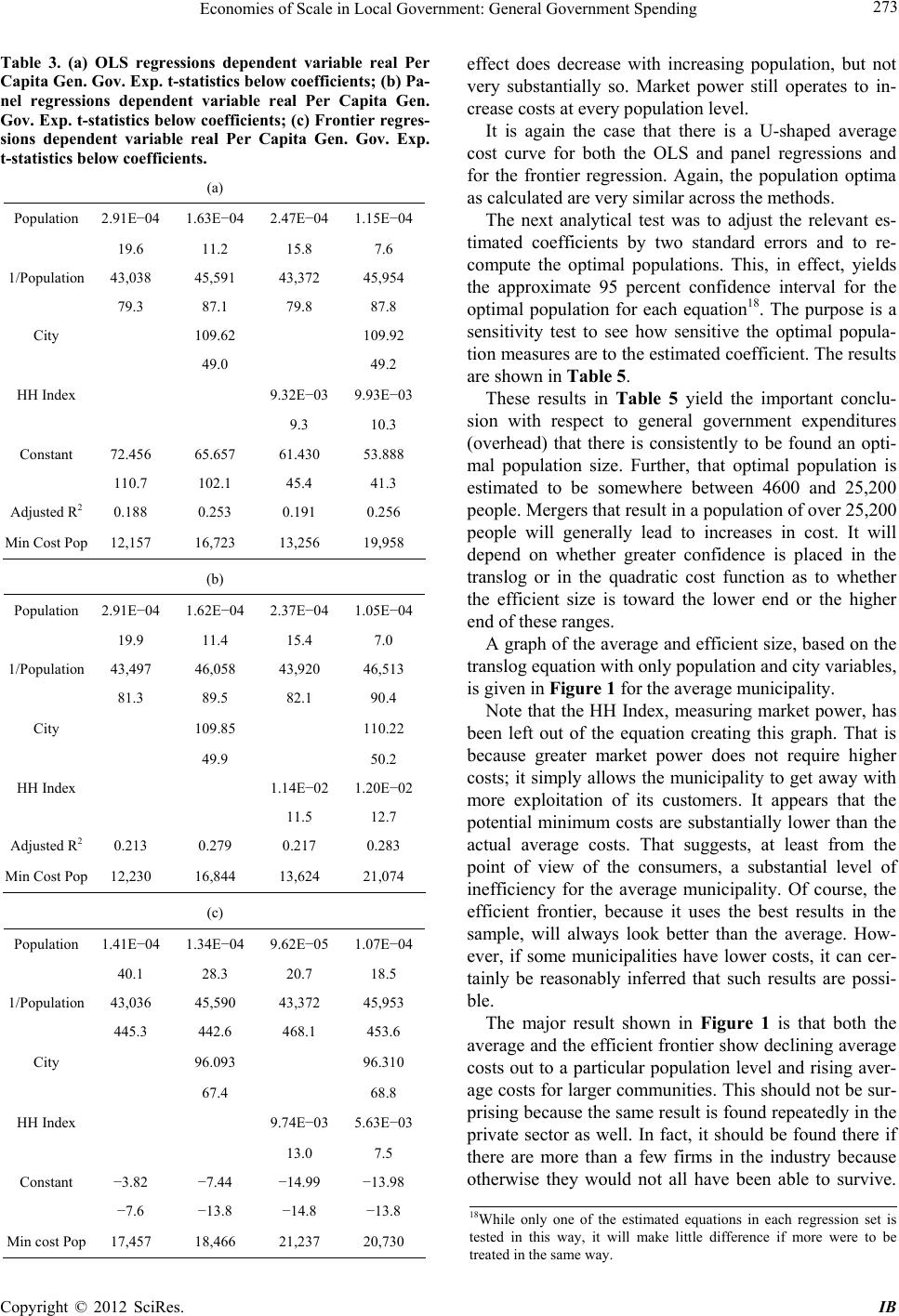

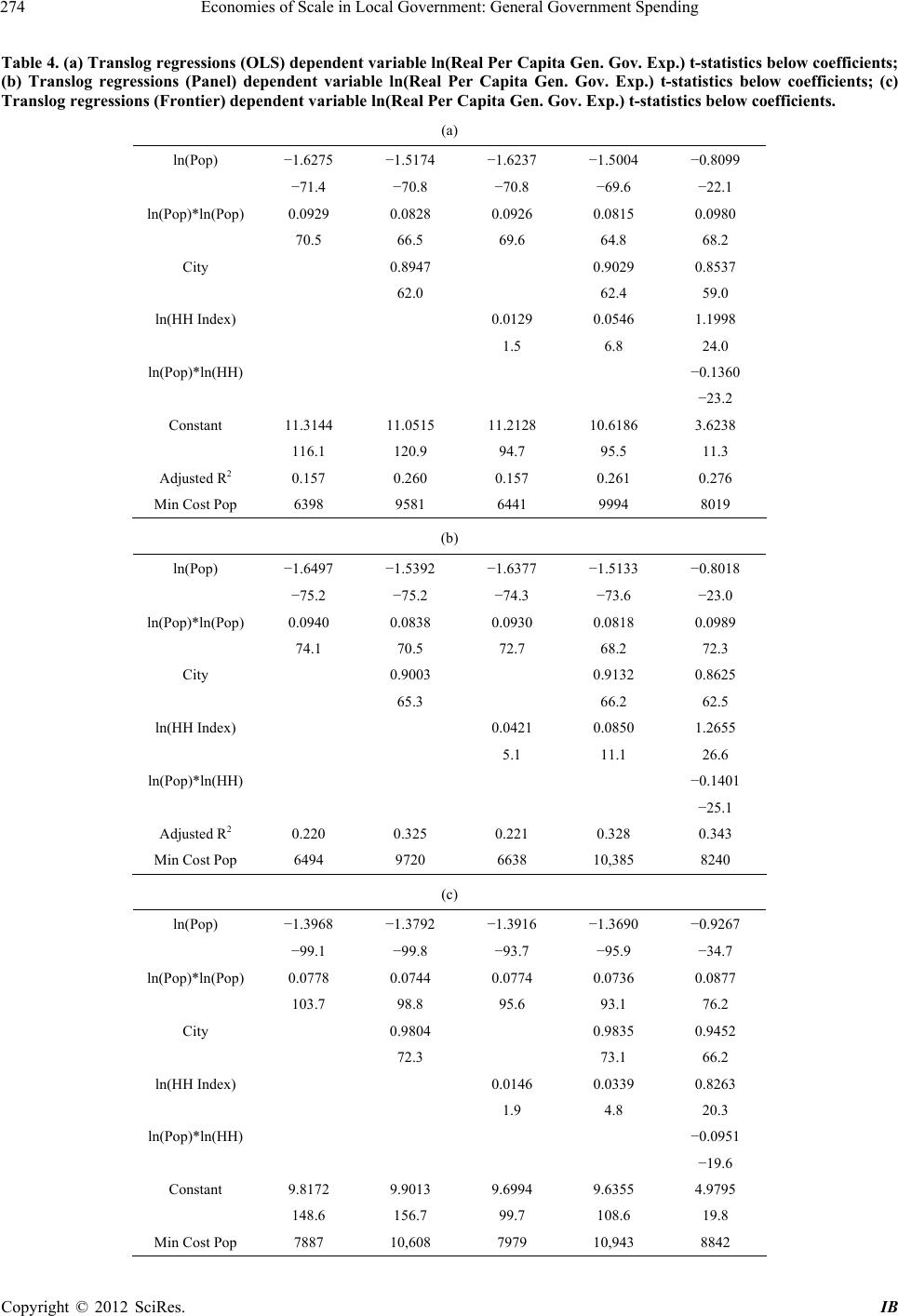

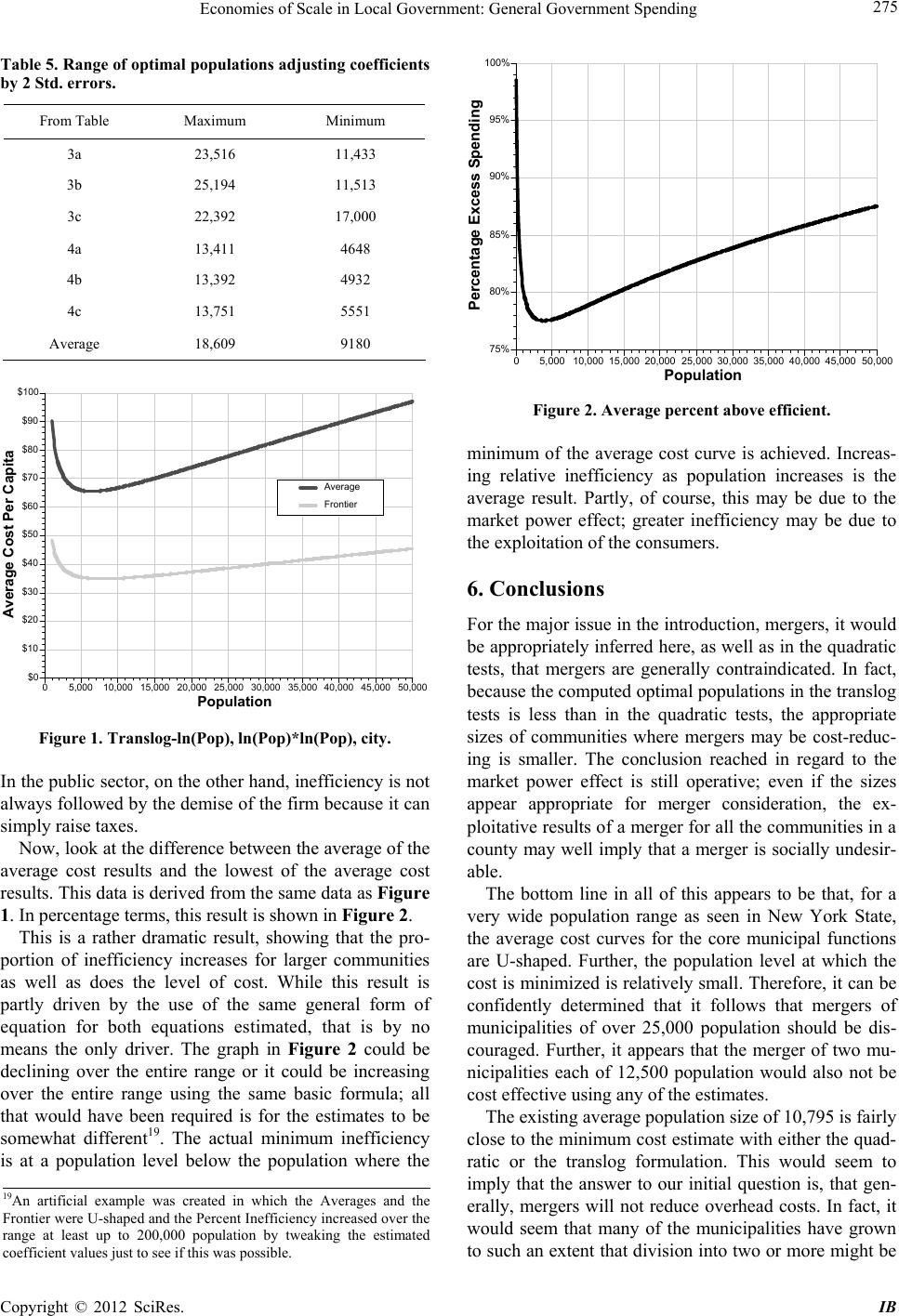

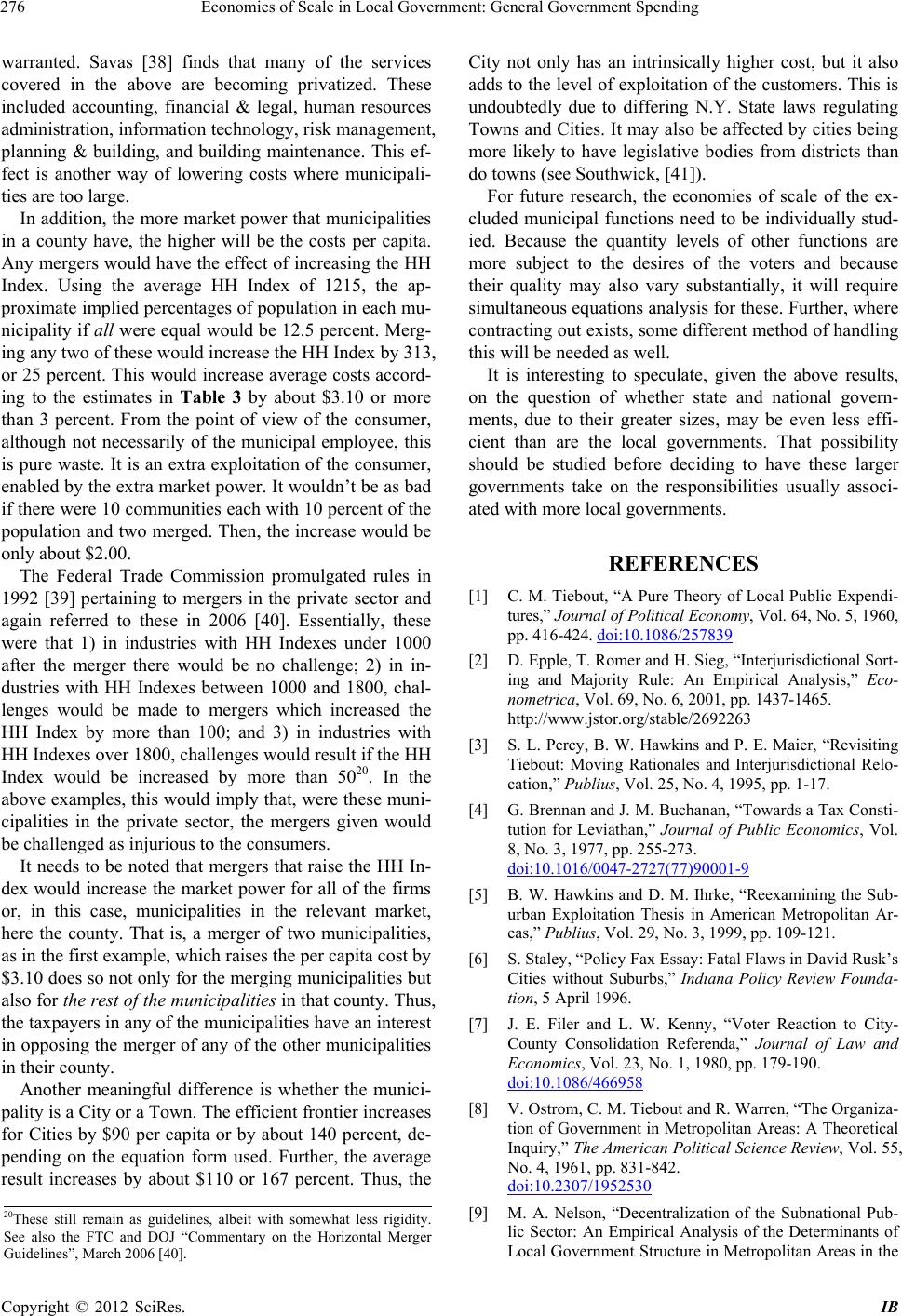

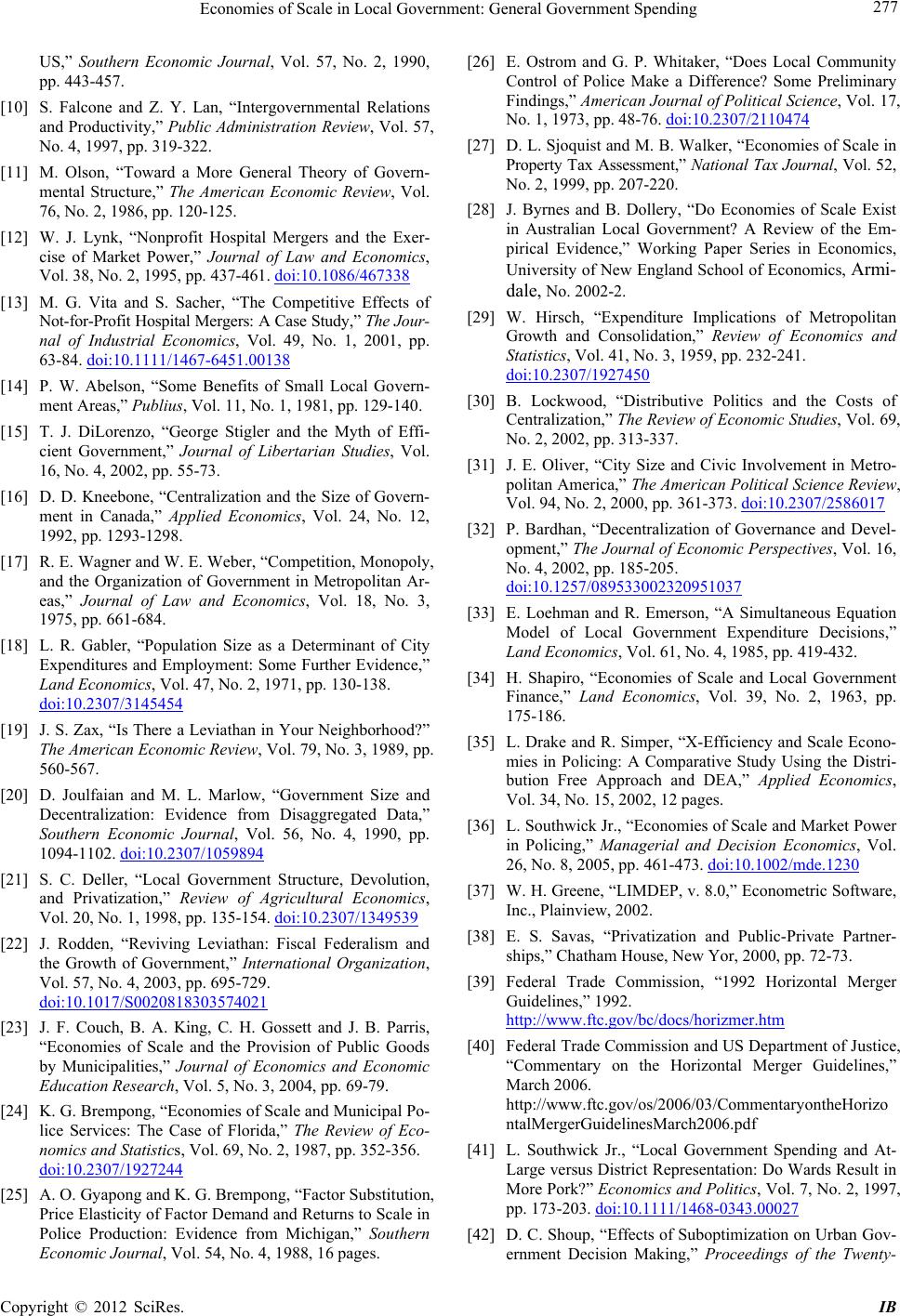

|