Intelligent Information Management, 2012, 4, 194-206 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/iim.2012.45029 Published Online September 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/iim) Measuring Effectiveness of Health Program Intervention in the Field Om Prakash Singh1, Santosh Kumar2 1Suresh Gyan Vihar University, Jaipur, India 2Indian Institute of Health Management Research, Jaipur, India Email: opsingh.jaipur@gmail.com, santosh@iihmr.org Received May 6, 2012; revised June 23, 2012; accepted July 12, 2012 ABSTRACT Improving and sustaining successful public health interventions relies increasingly on the ability to identify the key components of an intervention that are effective, to identify for whom the intervention is effective, and to identify under what conditions the intervention is effective. Bayesian probability an “advanced” experimental design framework of methodology is used in the study to develop a systematic tool that can assist health care managers and field workers in measuring effectiveness of health program intervention and systematically assess the components of programs to be applied to design program improvements and to advocate for resources. The study focuses on essential management elements of the health system that must be in place to ensure the effectiveness of IMNCI intervention. Early experiences with IMNCI implemented led to greater awareness of the need to improve drug delivery, support for effective planning and management at all levels and address issues related to the organization of work at health facilities. The efficacy of IMNCI program from the experience of experts and specialists working in the state is 0.67 and probability o f effective- ness of all management components in the study is 58%. Overall the standard assessment tool used predicts success of around 39% for the IMNCI intervention implemented in current situation in Rajasthan. Training management compo- nent carried the high est weight-age of 21% with 7 3% probability of being effective in the state. Human resource man- agement has weight-age of 13% with 53% probability of being effective in current scenario. Monitoring and evalu ation carried a weight-age of 11% with only 33% probability o f being effective. Op erational planning carried a weigh t-age of 9% with 100% probability of being effectively managed. Supply management carried a weight-age of 8% with zero probability of being effective in the current field scenario. In the study, each question that received low score identifies it as a likely obstacle to the success of the health program. The health program should improve all sub-components with low scores to increase the likelihood of meeting its objectives. Public health interventions tend to be complex, pro- grammatic and context dependent. The evaluation of evidence must distinguish between the fidelity of the evaluation process in detecting the success or failure of the intervention, and relative success or failure of the intervention itself. We advocate management attributes incorporation into criteria for appraising evidence on public health interventions. This can strengthen the value of evidence and their potential contributions to the process of public health management and social development. Keywords: Effectiveness; Efficacy; Performance; Evaluation; Measuring; Capacity Building of Health Interventions 1. Introduction Health systems have a vital and continuing responsibility to people throughout the lifespan. Comparing the way these functions are actually carried out provide a basis for understanding performance variations over the time and among countries. There are minimum requirements which every health care system should meet equitably: access to quality services for acute and chronic health needs; effective health promotion and disease prevention services; and appropriate response to new threats as they emerge (emerging infectious diseases, growing burden of non-communicable diseases and injuries, and the health effects of global environmental changes) [1]. The scarcity of public health resources in today’s heal- thcare environment requires that interv en tions to improv e the public’s health be evaluated using rigorous scientific and management methods. Public health interventions that cannot demonstrate effective use of resources may not be implemented. Thus, evaluation designs must reco- gnize and integrate the requirements of funding agents, ensure that intervention benefits can be accurately meas- ured and conveyed, and ensure that areas for improve- ment can be continuou sly identified. There is great interest in measuring the effectiveness and impact of programs developed to assist populations C opyright © 2012 SciRes. IIM  O. P. SINGH, S. KUMAR 195 affected by disasters and to aid in their recovery [2,3]. To evaluate the effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of a speci- fic health intervention typically involves comparing two populations, one that has received the intervention and the other that has not received it. The two populations are compared based on the probability th at th e interv en tion is effective in preventing or reducing the severity of the selected health outcome. In lieu of operations research, the probability of preventing the health outcome usually is based only on the clinical efficacy of the intervention, if it is known. For example, the estimated efficacy of poliomyelitis vaccination is 95% in laboratory trials, and this is the percentage used to describe the effectiveness of poliomyelitis vaccination [4,5]. This approach assum- es a one-to-one relationship between efficacy and effecti- veness and supposes that all programmatic elements for the health intervention (vaccination) are in place and ef- fective and that the community has access to and wants the intervention . As a result, these assumptions over-esti- mate actual program effectiveness and fail to identify ba- rriers to successful program implementation [6,7]. A great deal of applied research remains to be done to establish the efficacy and effectiveness of health inter- ventions and to assess the impact. In the meantime, field staffs need a systematic method to assess program effecti- veness that is timely, inexpensive, and measures program capacity as well as acceptance by the population. This will help describe actual impediments to program success and to identify methods and resources for program imp- rovement. Thus, to this end, an assessment process for field workers would be developed to explore and meas- ure whether a health program or interv ention is or will be effective to what extent. 2. Related Work As early as during the 1960s, an explanation of process evaluation appeared in a widely used textbook on program evaluation [8] (Suchman, 1967), although Suchman does not label it “process ev aluation” per se. Suchman writes: “In the course of evaluating the success or failure of a program, a gre at de al can be l earned about how a nd w hy a program works or does not work. Strictly speaking, this analysis of the process whereby a program produces the results it does is not an inherent part of evaluative rese- arch. An evaluation study may limit its data collection and analysis simply to determining whether or not a pro- gram is successful. However, an analysis of process can have both admin istrative and scientific significance , par- ticularly where the evaluation indicates that a program is not working as expected. Locating the cause of the fa ilure may result in modifying the prog ram so that it will work, instead of its bei ng discarded as a comple te f ail ure .” This early definition of process evaluation includes the basic framework that is still used today; however, as is discussed later in this chapter, the definitions of the com- ponents of process evaluation have been further deve- loped and refined. Few references to process evaluation were made in the literature during the 1970s. In evaluation research, the 19 70s w ere devoted to the issues of improv- ing evaluation designs and measuring program effects. For instance, Struening and Guttentag’s Handbook of Evaluation Research (1975) does not contain any refere- nce to process evaluation [9]. In their influential book, Green, Kreuter, Deeds, and Partridge [10] (1980) define process evaluation in a somewhat unusual way: “In a process evaluation, the object of interest is pro- fessional practice, and the standard of acceptability is appropriate practice. Quality is monitored by various means, including audit, peer review, accreditation, certi- fication, and government or administrative surveillance of contracts and grants.” The emphasis on professional practice as the focus of process evaluation as suggested by Green, Kreuter, Deeds, and Partridge (1980) faded as attention returned to the idea of assessment of program implementation. By the mid-1980s, the definition of process evaluation had ex- panded. Windsor, Baranowski, Clark, and Cutter [11] (1984) explain the purpose of process evaluation in the following way: “Process produces documentation on what is going on in a program and confirms the existence and availab ility of physical and structural elements of the program. It is part of a formative evaluation and assesses whether spe- cific elements such as facilities, staff, space, or services are being provided or being established according to the given program plan. Process evaluation involves docum- entation and description of specific program activities— how much of what, for whom, when, and by whom. It inc- ludes monitoring the frequency of participation by the target population and is used to confirm the frequency and extent of implementation of selected programs or program elements. Process evaluation derives evidence from staff, consumers, or outside evaluators on the qual- ity of the implementation plan and on the appropriate- ness of content, methods, materials, media, and instru- ments.” Effectiveness is defined emphasizing that it is a pro- blem domain measure which needs to support the comp- arison of systems. A simple thought experiment clarifies and illustrates various issues associated with aggregating measures of performance (MoP) and comparing measure of effectiveness (MoEs). This experiment highlights the difficulty in creating MoEs from MoPs and prompts a mathematical characterization of MoE which allows De- cision Science techniques to be applied. Value Focused Thinking (VFT) provides a disciplined approach to decom- posing a system and Bayesian Network (BN) Influence Diagrams provide a modeling paradigm allowing the ef- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IIM  O. P. SINGH, S. KUMAR 196 fectiveness relationships between system components to be modeled and quantified. The combination of these two techniques creates a framework to support the rigorous combination measurement of effectiveness. To overcome the shortcomings of traditional approa- ches to measuring effectiveness it is proposed that it is critical to measure effectiveness in the problem domain and an approach from Decision Science is used to produ- ce a clear distinction between the problem and solution domain. The problem domain objectives are used to cre- ate a Bayesian Network model of the interactions between elements in such a way that the effectiveness of the ele- ments can be combined to indicate overall effectiveness. Various definitions have been proposed, beginning in the 1950’s and progressing through MORS and NATO definitions in the 1980’s [12]. These definitions are larg- ely hierarchical and h ave yet to resolve how to aggregate and propagate performance and effectiveness measures through the h ierarchies. Th ese d efinitions tended to fo cus on measurement and effectiveness criteria. Sproles (2002) [13] refocused the discussion of effectiveness back to the more general question of “Does this meet my need?” and hence defined Measures of Effectiveness (MoE) as: “Standards against which the capability of a solution to meet the needs of a problem may be judged. The stan- dards are specific properties that any potential solution must exhibit to some extent. MoEs are independent of any solution and do not specify performance or criteria.” Needs may be satisfied by various solutions. The so- lutions may be unique or may share aspects of other so- lutions. Each solution may (and usually will) have dif- ferent performance measures. Sproles distinguishes be- tween Measures of Performance (MoP) and MoE by de- claring that MoP measures the internal characteristics of a solution while MoE measure external parameters that are independent of the solution—a measurement of how well the problem has been solved. The primary focus of the framework proposed here is to compare systems and to produce a rank ordering of effectiveness, as suggested by Dockery’s (1986) MoE definition [14]: “A measure of effectiveness is any mutually agreeable parameter of the problem which induces a rank ordering on the perceived set o f goals. ” The goal is not to derive absolute measures as they do not support the making of comparisons between disparate systems whose measures may be based on totally different characteristics and produce values with different ranges and scales. The two aspects of these definitions of MoE were em- phasised in the definition of MoE by Smith and Clark (2004) [15]: “A measure of the ability of a system to meet its spe- cified needs (or requirements) from a particular view- point(s). This measure may b e quantitative or qua litative and it allows comparable systems to be ranked. These effectiveness measures are defined in the problem-space. Implicit in the meeting of problem requirements is that threshold values must be exceeded.” In common with Sproles [16], it is accepted that effec- tiveness is a measure associated with the problem domain (what are we trying to achieve) and that performance me- asures are associated with the solution domain (how are we solving the problem). To develop a practical method to measure program ef- fectiveness in the field, the literature on program eva- luation and performance was reviewed, looking for des- cription of program success. To calculate the expected effectiveness of public health intervention (Eph), the relationship between the expected effectiveness of a heal- th program and the factors that influence its success are a product of the efficacy of the strategy or intervention (SE) and the probability that the health program in place can deliver the interventions successfully. Sharon M. Mac- Donnel, et al. used Bayes theorem as essential too l in Af- ghanistan and retested in six different settings Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Guetamala, Philiphines and Ghana and found- ed that this method systematically assessed the compo- nents of program and results can be applied to design program improvements and to advocate for resources. On carefully reviewing this, it was noticed that it mainly consists of four components human resource, training, infrastructure and community support. The adoption of Bayes’ theorem has led to the deve- lopment of Bayesian methods for data analysis. Bayesian methods have been defined as “the explicit use of external evidence in the design, monitoring, analysis, interpreta- tion and reporting” of studies. The Bayesian approach to data analysis allows con sideration of all possible sou rces of evidence in the determination of the posterior proba- bility of an event. It is argued that this approach has more relevance to decision making than classical statistical inf- erence, as it focuses on the transformation from initial knowledge to final opinion rather than on providing the “correct” inference. In addition to its practical use in pro- bability analysis, Bayes’ theorem can be used as a norm- ative model to assess how well people use empirical info- rmation to update the probability that a hypothesis is true. Bayes’ theorem is a logical consequence of the product rule of probability, which is the probability (P) of two events (A and B) happening—P(A,B)—is equal to the conditional probability of one event occurring given that the other has already occurred—P(A|B)—multiplied by the probability of the other event happening—P(B). The derivation of the theorem is as follows: PA,BPA|BPB PB|APA PA|B PB|APA/PB . Thus: Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IIM  O. P. SINGH, S. KUMAR 197 Capacity assessment tools designed to assess organi- zational performance were reviewed. The majority of the 23 tools reviewed employ several data collection instru- ments. Nearly half of them used a combination of quali- tative and quantitative methods, four used quantitative method and seven used qualitative methods. Half of the tools are applied through self-assessment techniques, while nine tools use a combination of self and external assessment and two tools use external assessment. Self- assessment tools can lead to greater ownership of the results and a greater likelihood that capacity improves. However, many such techniques measure perceptions of capacity, and thus may be of limited reliability if used over time. The use of a self-assessment tool as part of a capacity building intervention may preclude its use for monitoring and evaluation purposes. Methodologies for assessing capacity and monitoring and evaluating capa- city building interventions are still in the early stages of development. Experience of monitoring changes in capacity over time is limited. Do cumentation of the range of steps and activities that comprise capacity develop- ment at the field level is required to improve under- standing of the relationship between capacity and perfor- mance, and capacity measurement in general. Finally, there are few examples of use of multiple sou rces of data for triangulation in capacity measurement, which might help capture some of the complex and dynamic capacity changes occurring within systems, organizations, program personnel, and individuals/communities. Nearly one third of tools reviewed include adminis- trative and legal environment aspect and one fourth in- clude socio cultural, political and advocacy environment while doing the assessments. External factors represent the supra-system level and the milieu that directly or in- directly affects the existence and functioning of the public health organization. It incorporates phenomenon such as the social, political, and economic forces operating in the overall society, the extent of demand and need of public health services within community, social values. Inclusion of external factors in assessment tool demonstrates that organization is engaged in dynamic relationships. Based on the review of capacity assessment tools and discussion with experts of public health, we grouped ele- ments of program effectiveness in 10 management com- ponent namely mission and values, strategic manage- ment, operational planning, human resource management, financial management, monitoring and evaluation systems, logistics and supply system, quality assurance, and respon- siveness to client/service delivery. 3. Material and Methods The research fra mework for the study is based on Bayes’ theorem. Bayes’ theorem deals with the role of new info- rmation in revising probability estimates. To develop a practical method to measure program effectiveness in the field, the literature on program evaluation and perform- ance was reviewed, looking for description of program success. To calculate the expected effectiveness of public health intervention (Eph), the relationship between the expected effectiveness of a health program and the fact- ors that influence its success are a product of the efficacy of the strategy or intervention (SE) and the probability that the health program in place can deliver th e interven- tions successfully. Seven step process to calculate effectiveness of pro- gram intervention in demons trated in Table 1. The following steps followed to calculate the expected effectiveness of public health intervention: Step 1: Selection of the public health program or in- tervention which needs to be evaluated. Integrated Management of Neonata l Chil dhood Ill nesses (IMNCI) program based on the discussion with public health experts was selected as case study for evaluation. Step 2: Define the efficacy of the intervention. The efficacy of the intervention is defined using avail- able health literature or field trials. If it is unknown, it can be discussed and estimated. In this study IMNCI pro - gram efficacy is based on the opinion of experts working on IMNCI in India and Rajasthan. Step 3: Define the key components/elements of pro- gram effectiveness. Based on literature review of performance measuring studies of health interventions and discussions with the public health experts, decision makers and implementers identify key elements of program success and factors influencing the success of the program. Using this infor- mation, develop a set of standard questions and instruc- tions. To help staff members to determine whether these elements increase or decrease their overall program ef- fectiveness, and in what ways, a standard field assessment tool was developed. The standard field assessment tool is designed to describe and measure the essential variables within the health program effectiveness categories and the proportion of weight age each element carries for Table 1. Seven step process to calculate effectiveness of program intervention. Seven step process to calculate effectiveness of program interven- tion Step 1: Selection of the public health program or intervention which needs to be evaluated Step 2: Define the efficacy of the intervention Step 3: Define the key components/eleme n t s o f p rogram effectiveness Step 4: Selection of the assessment team and define scoring Step 5: Conduct the interview with program decision makers, mangers and field level workers Step 6: Using worksheet to calculate the program effectiveness Step 7: Calculate aggregate probability (PA) that the program in place delivers the health intervention effectively Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IIM  O. P. SINGH, S. KUMAR 198 success of the program. Identified 10 elements of health program effectiveness are mentioned in Table 2. Step 4: Selection of the assessment team and define scoring. Review and adopt the criteria and essential features of each of the key management components of health pro- gram effectiveness. All answers “a” are 0 points, “b” is 1 point, “c” answers are 2 points and “d” answers are 3 points. If there are more than one respondent for a ques- tion, the mode value is calculated for scoring. Step 5: Conduct the interview with program decision makers, mangers and field level workers. Five state level officials having stake in IMNCI plan- ning and implementation including State Program Man- ager, State IMNCI Coordinator, Child Health Coordina- tor and Additional Director and State Demographer offi- cials was interviewed personally. UNICEF officials at state level involved in conceptualizing, planning and sup- porting the state government in implementing IMNCI Program were personally interviewed. The officials in- terviewed were Health Specialist, Health Officer and IMNCI Consultants. Total four persons were int erviewed. The IMNCI program managers at zonal level and dis- trict level were approached through email. The question- naire was circulated to them with instruction of best knowing and responding to the questions as per their un- derstanding. In the month of February 2010, the data collection tools were finalized. Five state level officials are having say in IMNCI planning and implementation including State Program Manager, State IMNCI Coordinator, Child Health Coordinator and Additional Director and State Demographer officials was interviewed personally. UNICEF officials at state level involved in conceptu- alizing, planning and supporting the state government in implementing IMNCI Program were personally inter- viewed. The officials interviewed were Health Specialist, Health Officer and IMNCI Consultants. Total four per- sons were interviewed. Table 2. Management components of health program effec- tiveness. S.No. Management components 1 Mission and values 2 Strategy development 3 Operational planning 4 Human resource a nd manageme n t 5 Training 6 Monitoring and evaluation 7 Quality assurance 8 Financial management 9 Supply management 10 Community support Reproductive Child Health officer, District Program Manager, District IMNCI Coordinator, 10 Medical offi- cers, two District IMNCI Monitoring Supervisors, and three IMNCI tutors were interviewed. In addition to this, 10 ANMs and 30 ASHAs were interviewed with the sup- port of nursing tutors. In order to obtain consent from the participants, a me- thodology of “implied consent” [17] was used. The ob- jective of survey was read out to each of the person inter- viewed personally and shared via email and shared that all individual information would be confidential. Names were recorded only on the consent of the participants otherwi s e n ames were not recorded. Step 6: Using worksheet to calculate the program ef- fectiveness. Record the responses from questionnaire on to the worksheet. Add the points of each component and calcu- late the subtotal score. Calculate the maximum possible scores assigned to each component. Calculate the propor- tion of each component by dividing the sub total score with maximum possible points. This gives probabilities of effectiveness of each component based on scoring sys- tem (P). As demo nstrated in Table 3 for two management components the P value is calculated for all the 10 mana- gement components. Program effectiveness (PE) is product of P and contri- bution i.e., weight age (W) assigned to each management component. The tabular form for calculation is men- tioned in Table 4. As a formulae it is represented as PE = P1*W1 + P2*W2 + P3*W3··· where P1 and W1 repre- sent individual component effectiveness weight age re- spectively. Step 7: Calculate aggregate probability (PA) that the program in place delivers the health intervention effect- tively using the following: PA = PE* efficacy of the intervention. The aggregate overall probability of health program effectiveness is the product of efficacy of the specific intervention multiplied by the sum of the probabilities of each of the weighted components contributions. Experimental design is used as study intends to predict P phenomenon. Bayesian probability an “advanced” ex- perimental design is main framework of methodology Table 3. Worksheet to calculate the p rogram effectiven es s . Mission and values Strategy Sub component Existence and knowledge of mission Defined organizational values and principles Sub total score Sub total score divide by total possi le score (P) Score (0 - 3) points ---- ---- ---- ----/6 = Sub component Program strategies linke to Mission and values Program Strategies linked to clients and communities Subtotal score Subtotal score divided by total possible score (P) Score (0 - 3) points --- --- --- ---/6 = Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IIM  O. P. SINGH, S. KUMAR Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IIM 199 used in the study [18]. This advanced experimental de- sign is used for settings as there are many variables which are hard to isolate. Judgmental sampling technique is used in the study. Judgmental sampling is a non-probability sampling tech- nique where the researcher selects units to be sampled based on their knowledge and professional judgment (by Joan Joseph Castillo (2009)). This type of sampling technique is also kno wn as purposive sampling and auth- oritative sampling. Data entry and cleaning was done by self. Data entry and analysis was done using SPSS for Windows 16.0. In- itial data analysis included frequency tables on the indiv- idual items of the interview. Subsequently, using the qual- ity dimensions that form the framework of Bayes theorem the ten management attributes and their subsequent sub components we re analyzed based on sc o re syst em. Several forms of research bias could not be prevented due to various constrains encountered: time, resources, research implementation, analysis and design. Selection bias could not be ruled out because of non-random meth- od used to select the participan ts. 4. Experimental Result and Discussion Integrated Management of Child hood Illness Program (IMNCI) is run by Government of Rajasthan with mana- gerial and technical support of UNICEF designed to combat the high Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) in the state through training and support to field level h ealth workers such as ASHAs and ANMs. During the study, the program effectiveness tool to measure the program effectiveness was used in collaboration with Program Managers and implementers to evaluate the likelihood of this public health program in the state. The findings from this study are described here and scored numerically on worksheet for refer en ce. IMNCI program effectiveness in the state of Rajasthan calculates to be 58% from probabilities of effectiveness for each program component based on scoring system and the contribution (weight) given to each category. The worksheet for the calculation of program effectiveness is reflected in Table 5. Table 1. Calculating probability of program effectiveness. Probabilities of effectiveness of each program component based on th e scoring system (P)Contribution (weight) given to each category (W) Probability of program effectiveness (PES*W) Mission and values Strategy development Operational planning Human resource an d managemen t Training Monitoring and evaluation Quality assurance Financial management Supply management Community support Probability of PE Table 5. Worksheet for calculating the health program effectiven ess. Probabilities of effectiveness of each program component based on th e scoring system (P)Co ntribution (weight) given to each category (W) Probability of program effectiveness (PES*W) Mission and values (MV) 0.50 0.08 0.04 Strategy (S) 0.67 0.07 0.05 IMNCI OP (OP) 1.00 0.09 0.09 IMNCI HR (HR) 0.56 0.13 0.07 IMNCI training (T) 0.73 0.21 0.15 M & E (ME) 0.33 0.11 0.04 QA (QA) 0.67 0.09 0.06 FM (FM) 0.44 0.08 0.04 SM (SM) 0.00 0.08 0 CS (CS) 0.67 0.06 0.04 Probability of PE 0.58  O. P. SINGH, S. KUMAR 200 The aggregate overall probability of health program effectiveness is the product of efficacy of the specific intervention multiplied by the sum of the probabilities of each of the weighted components contributions. Probability of aggregate program effectiveness Efficacy of interventionhealth program effecti PA PEefficacy of the intervention 10.58 assuming 100 percent efficacy of i 0.58 or 58% veness; ntervention The study focuses on essential management elements of the health system that must be in place to ensure the effectiveness of IMNCI intervention. Early experiences with IMNCI implemented led to greater awareness of the need to improve drug delivery, support for effective planning and management at all levels and address issues related to the organization of work at health facilities. The efficacy of IMNCI program from the experience of experts and specialists working in the state is 0.67 and probability of effectiveness of all management compo- nents in the study is 58%. Overall the standard assess- ment tool used predicts success of around 39% for the IMNCI intervention implemented in current situation in Rajasthan. Training management component carried the highest weight age of 21% with 73% probab ility of being effective in the state. Human resource management has weight age of 13% with 53% probability of being ef- fective in current scenario. Monitoring and evaluation carried a weight age of 11% with only 33% probability of being effective. Operational planning carried a weight age of 9% with 100% probability of being effectively managed. Supply management carried a weight age of 8% with zero probability o f being effective in th e current field scenario. In the study, each question that received a zero for any element of the 10 management components and its sub- components identifies a likely obstacle to the success of the health program. The health program should improve all sub-components with low scores to increase the like- lihood of meeting its objectives. If the total score is less than 50%, the program is unlikely to be effectively im- plemented, and if the total score is more than 80%, the program is likely to be effectively implemented. If the score of any entire component is zero, the actual proba- bility of program effectiveness should be considered zero . The formula as provided does not naturally lead to this conclusion because it is additive rather than multiplicative. Evidence-based health care is untended to take account of efficiency as well as effectiveness, although to date efficiency questions have not been emphasized in evi- dence-based medicine [19]. The appraisal of evidence on public health interventions must inevitably determine whether the efficiency has been assessed, and if so, how well. Public health interventions are rarely a standard package. To assess the success of intervention, informa- tion is needed on the multiple components of interven- tion. This should also include details about the design, development and delivery of the various intervention strategies. Information is also needed on the charac- teristics of people for whom the intervention effective, and the characteristics of those for whom it was less ef- fective. The social, organizational and political setting (context) in which a public health intervention is imple- mented usually influences the intervention effectiveness [20]. It is important to distinguish between components of interventions that are highly context dependent and those that may be less so. Field workers need tools to systematically describe and measure key elements of program effectiveness so that they can rapidly identify specific areas of insuffi- ciency and communicate these needs more effectively to program managers and decision makers. Tools for prog- ram effectiveness that do not consider health worker training, infrastructure, and community assessment can greatly overestimate program effectiveness [21]. A known good intervention (e.g., immunization) delivered through a poor program cannot be effective. Field staff reported that using the assessment tool pro- moted more detailed and creative discussions about the actual problems and potential solutions that had to be considered in the design and improvement of their pro- grams. In fact, the discussions among staff members regard- ing their programs often were reported as being just as important as the actual calculation of the numbers. For example, the health workers in the Afghanistan case study used the information gathered to discourage their NGO from adding more curriculum material in the basic course for female health workers. Instead, the program focuses and grant proposal emphasized a shift to improved rec- ruitment, applied training, and infrastructure components relating to supervision and continuing education. For some program staff, the calculations might appear dis- couraging and can be skipped. Many mentioned the value of reviewing the distinction between efficacy and effecti- veness and to explicitly understand that for many prog- ram interventions, the efficacy is not known and effecti- veness has not been well researched. The major limi- tation of this approach is the potential for inter-observer variability. Different persons using the same question- naire can get different results even in the same situation. However, within a program, the field staff usually work- ed with the questionnaire to define the terms and indi- cators. Another limitation of this method is that it has not been tested over time to determine how well it corre- sponds with actual program performance or health out- comes. There are not gold-standard tools available to measure Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IIM  O. P. SINGH, S. KUMAR 201 program capacity and effectiveness [22]. To improve this methodology and its tools, the authors intend to refine the questions within each component and to increase the specificity of the information collected. This is needed, particularly in the community support components. Fur- ther validation should assess inter-observer variation. The method’s instructions also must be tested with new evaluators and within a variety of programs, to assess how easy it is for others to administer the questions, use alternative data sources, and calculate the overall proba- bility. Staff members in Tanzania assessing health in- formation systems raised the issue of the availability of allied services (e.g., laboratory); this method could be modified to address specific program elements. Based on the information collected in the field tests, one of the most important areas that should be addressed is whether the weighting of the components should be changed. For example, infrastructure problems were na- med as the biggest impediment to program effective- ness by health workers, ministry officials, and donors, and might need to be given a higher weight. The infras- tructure measures used for this category often were asso- ciated with the con cept of higher-level “political support” and long-term viabil it y [23] . The usefulness of this met hod will increase with more thorough descriptions of core health worker functions. Finally, the usefulness of this tool must be judged through further field-testing and validation to determine if its use by field work ers leads to substantive changes in the processes and outcomes of health programs. Beyond the field level, it is hoped that by measuring and using these programmatic variables, more attention will be focused on innovative methods that improve the training and support of health workers, the quality and type of infrastructure, and the support of communities, thereby addressing well-known, but often ignored, problems of health programs. The major challenges were noted in effective imple- mentation of IMNCI in Rajasthan: drug supply with zero effectiveness; poor financial and HR management, poor monitoring and evaluation and low level of implemen- tation at health facilities by trained staff. At the facility level, low take up of implementation of the strategy is partly attributed to factors which are specific to IMCI, such as inadequate supply of job aids, lack of IMCI su- pervision and protocol length. Other constraints to im- plementation include staff shortages at lower level faci- lities, infrequent routine supervision that includes case management observations, and frequent drug stock-outs. Findings from the Multi Country Evaluation (MCE) study of IMCI effectiveness carried out in 5 countries (Bangladesh, Brazil, Peru, Tanzania and Uganda) from 1998-2004 suggested that IMCI was more effective and less costly than routine care. Health workers who received IMCI case management training in Tanzania, for example, provided a better quality of care than untrained health workers [24], and there were notable improvements in classification, diagnoses, treatment and counseling by trained health workers, compared to those who had not received any training. Similarly, in Uganda, it was repo- rted that health workers who had been trained in IMCI consistently provided better care for sick children than untrained health workers [25]. These positive results were not, however, r eported by all of th e MCE countries. Arifeen et al. (2005) [26] showed that, even though Bang- ladeshi health providers were trained in IMCI, skill- suptake was not guaranteed, resulting in littl e or no ap pli- cation of IMCI case management in practice. Similarly, doctors and nurses in Brazil did not show any major diff- erence in the quality of care given to sick children com- pared to untrained health providers [27]. Impact studies conducted in Peru did not look at the effects of IMCI training on health worker behaviour; however, one study showed no significant associations between training coverage and changes in mortality or nutrition indicators [28]. Even where positive impacts were achieved, the MCE findings emphasized that more efforts should be made to ensure better coverage of IMCI, such as availability of sufficient resources to sustain IMCI implementation activities and cover all 3 compon- ents of the strategy. Studies on IMCI implementation in other countries have some similar findings, suggesting that the issues raised by this study can still provide important insights into implementation challenges in similar contexts [29]. Several past studies which examined implementation challenges of IMCI have also highlighted poor health worker compliance, indicating that it is likely to be a ge- neric issue across many different country settings. In a study conducted by Rowe et al. (2001) in Benin, determi- nants for poor implementation of IMCI by health workers were identified using qu alitative research appro aches (in- terviews, case management observations). These studies focused on selected component of IMNCI interventions and thus not represent complete assessment of IMNCI program implementation. Our study results were surprisingly close to their fin- dings, with health workers reporting almost all of the same reasons for poor implementation, such as poor facility support (job aids, equipment, and drugs), high workloads, short-staffing, and no or little IMCI-specific supervision. Nsungwa-Sabiitii et al. (2004) repo rted th at health sys- tems and resource constraints similar to those found in Kenya have also affected IMCI implementation in Uga- nda [30]. For example, difficulties in drug acquisition led to Uganda adopting a “pull system” to improve drug de- liveries to facilities but this has had little effect. In terms Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IIM  O. P. SINGH, S. KUMAR 202 of financial support, IMCI was noted as requiring vast amounts of resources and, despite there being several funders, not a lot of money has been raised to support existing or future activities. This study focused on direct supply process and did not take human resource required for supply management. Supply management with zero effectiveness needs to be paid attention in the state. A system to procure, track and regulate supplies needs to be in place. Health de- partment needs to train staff to handle IMNCI supplies. One major constraint to poor implementation of IM- NCI in Rajasthan is the lack of financial management system for the facility component of the strategy. Our interviews/inv estigation showed that this d eclinin g interest reflects the high cost of training, difficulties in demons- trating the public health i mpact of IMCI, increased focus on the community aspect of the strategy, lack of consensus on new or alternative training approaches. Financial sys- tem for IMNCI needs improvement. Program Managers need to work with financial staff to develop IMNCI budgets that support programmatic decision. The finan- cial system needs to present an accurate, complete pic- ture of IMNCI expenditures, revenue, and cash flow in relation to program output and services. The health de- partment to follow a long term fund generation strategy, balancing diverse sources of revenue to meet current and future needs. In our literatu re review we did not find any paper or research article focusing on financial manage- ment of IMNCI system. Variations in the implementation experience were also noted. These include differences in human resource man- agement systems, health worker adherence to IMNCI guidelines, and overall support o f the strategy. The major determinant of these differences appeared to be the leadership role of the IMNCI. Major barriers to IMNCI implementation arising from broader health system issues were documented in many countries. These barriers included: the difficulties of con- ducting regular supervisory visits that included systema- tic observation and feedback on case manage ment; in ade- quate referral facilities; high staff turnover; low utiliza- tion of the public sector for a variety of reasons (accessi- bility, user fees, poor perceived quality, etc.); and inconsi- stencies between IMNCI guidelines and existing policies and regulations. Health department needs to regularly monitor its IMNCI progress, evaluate results ad use find- ings to improve services and plan the next phase of work. Health system to provide cr oss-checking to guarantee the accuracy of routine IMNCI services and data. Staff mem- bers who submit report consistently should get prompt feedback. With their managers, they analyze the infor- mation and use their findings to analyze the trends, im- prove management and performance, and achieve out- comes. High-quality training in IMNCI case management can lead to rapid and dramatic improvement in the quality of case management in first-level health facilities. In this context, “high quality” is defined as training that is based on the IMNCI clinical guidelines and includes sufficient opportunities for trainees to practise the new skills in cli- nical settings. In some Regions this training also includes follow-up visits to health workers in their facilities after training to reinforce skills and assist health workers in applying them. However, IMNCI training can only be effective in improving th e quality of case manag ement in the presence of health system supports. A common find- ing across the 12 MCE country reviews was that these supports were not in place. Although the constellation of health system deficits varies to some extent from region to region, and especially in the post-Soviet countries versus all others, many of the challenges are similar. In Tanzania, health system supports had been reinforced in the two intervention districts through the introduction of two relatively simple interventions: making available district-level data on the burden of disease, and epide- miological mapping. Outside the intervention districts, however, Tanzania faces many of the same health system deficits as the other countries visited. From the assess- ment study we found that training carries maximum weight-age of 21 percent for effective implementation of IMNCI in the state of Rajasthan. The effectiveness of training in Rajasthan w as found to be 73 percent. Almost 80 percent of respondents felt IMNCI workers had relevant education or experience for being IMNCI work- er and half of respondents felt the IMNCI orientation program is in place. From the study it is revealed that training is formal component of the health department and it allows adequate time for each participant for on hand practice. Development and implementation of interventions to improve key family behaviors has proven more difficult and time-consuming than anticipated at the time MCE was designed. Among the 10 countries visited that were actively implementing IMNCI, only Brazil had com- munity component—delivered by community health workers—that seemed likely to achieve high levels of coverage. In short, several of the assumptions underlying the IMNCI impact model need to be re-examined in light of experience with IMNCI implementation to date and the findings of MCE country reviews. An Evaluation of the Quality of IMCI assessments among IMCI Trained Health Workers in South Africa 2009 found that health workers are implementing IMCI, but assessments were frequently incomplete, and children requiring urgent referral were missed. If coverage of key child survival interventions is to be improved, interven- tions are required to ensure competency in identifying specific signs and to encourage comprehensive assess- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IIM  O. P. SINGH, S. KUMAR 203 ments of children by IMCI practitioners. The role of su- pervision in maintaining health worker skills needs fur- ther investigation. Further research is required to inves- tigate the factors leading to poor health worker per- formance, which is frequently ascribed just to a lack of knowledge and skills. Health workers often find it dif- ficult to transfer new skills to the work place, and to maintain these skills, especially as IMCI consultations take longer. Implementing and sustaining IMCI follow up after training has been shown to be difficult in several previous evaluations of IMCI However, supervision has been shown to improve performance and may also im- prove motivation and job satisfaction. The role of IMCI supervision in IMCI implementation and different mo- dels for provision of supervision should be investigated further. Performance Analysis of IMNCI in Madhya Pradesh 2006 reported that training under IMNCI is reported to be very beneficial by all the respondents but the lack is that there is no provision of follow up or refresher train- ings especially for field staffs. While in non-IMNCI districts the skills and knowledge of field staffs is not as sound as that of MNCI districts staffs on children health care and disease management. The home based care has been given special emphasis under IMNCI and is very effective strategy for disease management at an early stage. But the functional problem found in home based care is that the field staffs are highly overloaded with a wide area and various activities including too much paper work. So it becomes practically impossible for field staff s to manage sufficient time to provide home based manage- ment and counseling to all the beneficiaries for children and maternal health care. In non-IMNCI districts the status of home visit is further in bad shape as compared to the IMNCI districts. Under IMNCI the staffs is ori- ented to identify and refer the sick children to public health institutes at earliest. But due to the lack of proper information among community about the childhood ill- ness and services under IMNCI the community doesn’t approach to the aaganwadi center for referral support. Also, the system and facilities at public health institutes are in so bad conditions that those who are reaching to the institutes by hard efforts of field staffs get so annoyed that they don’t wish to visit again. Also AWW are mostly making oral referral & not ready to take-up the respon- sibility for child referral. The instructions and the process regarding the incentive distribution are not at all clear. There is severe shortage of manpower & essential faci- lities for safe child birth, newborn care & treatment of childhood illness at block & district levels public health institutions. The most positive approach visible in IMNCI district is the establishment of SNCU that leads to pre- vention of child mortality in newborn period. But block level institutions at IMNCI districts are still lacking such facilities. Though in spite of being a very innovative program IMNCI is not meeting its objective of securing better child health and all these problems are due to the neglect or the neutral attitude of the administration. While in practical it is always seen that the lower most link i.e. the field staffs are often blamed for non-achievement of the set targets. Moreover, if someone complaints about the non-functioning of any program/activities or if anything goes wrong then the foremost step taken is the removal/ suspension of these field staffs who can do nothing to resurrect the things nor there is any support system available for them at district or state level which could help these field staffs to prevent the casualties. To make IMNCI (or any program) really working and result orienting, the government should develop all the connected wings equally whether it is the training of implementing staffs, follow-up, supervision or the infras- tructural su pport. Report of IMCI evaluation in the District of Kirehe in Rwanda, July 2008 concludes that on the operational level, managers of HCs were able to implement IMCI through the collaboration of parents and other health workers who have welcomed this new approach of mana- gement of sick children. But significant barriers impede a final and sustainable IMCI implementation and this is an appeal to health authorities from the central level. These barriers are: lack of supervision, insufficient number of trained health care providers, non-harmonization of mal- aria management guidelines, non-integration of IMCI in the health management information system, non-equit- able management of ambulances to promote children’s access to emergency care, the insufficient availability of patient forms and especially the fact that IMCI is not integrated with the group of activities quoted by the performance based financing approach to increase moti- vation and retention of staff in general and trained per- sonnel in particular. The training of health workers in IMCI is necessary to improve the quality, but not enough to ensure a continuously acceptable quality level without the establishment of a mechanism for monitoring and strengthening of techn ical skills such as formative super- vision. IMCI is not considered in the performance based financing approach at health centers level and is not inte- grated into the health information management system. Effect of Supportive Sup ervision on ASHA s’ Perform- ance under IMNCI in Rajasthan UNICEF 2008-09 find- ings show that supportive supervision by an external agent can lead to substantial improvement in the performance of ASHAs as related to IMNCI. Under the current supervisory system, many line supervisors lack a clear understanding of their roles and respon sibilities as super- visors. In addition, they lack sufficient time and training to provide supervisory support to ASHAs under IMNCI. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IIM  O. P. SINGH, S. KUMAR 204 We find that supportive supervision has the greatest effect in improving ASHAs’ capacity, and hence their performance under IMNCI in the following areas: record keeping, motivation, and knowledge and skills, such as the use of IMNCI reference materials and techniques in home visit assessments. However, while external suppor- tive supervisors were effective in providing IMNCI mat- erials, registers, and case sheets, we find less evidence that they can improve access to medicine. Regardless of the presence of supportive supervision, ASHAs continue to face resistance from their communities against insti- tutional deliveries, immunizations, health checks for new born, and referral to hospital facilities. In general, IMCI could be said to be a typical example of a top-down approach to implementation, with the policy set at the central level then communicated to lower lev els, such as the provincial, district level and facility level, with minimal adaptation taking place at each level. This model assumes actors at the top have the most power, and actors at other levels follow a chain of command. Debates about the top-down approach highlight the following issues and/or assumptions, making such models of implementation unrealistic through: ignoring the im- portance of involvement of non-government actors in de- cision-making as well as those from lower levels of the health system; assuming that all actors are committed, skilled, willing (compliant) and supportive of the policy; ignoring the possibility of constraints imposed by external agencies or circumstances that might undermine efforts; and/or assuming perfect coordination of implementation activities [31]. The success of policy implementation is, moreover, linked to the types of relationships between actors at dif- ferent levels, with some policies being entirely rejected by implementers at the periphery. The bottom up pers- pective, thus, suggests that implementation management should allow for the involvement and interaction of a variety of actors in the implementation process. The facility component of IMCI specifically aims to improve health worker practice, and relies on good uptake of IMCI case management skills. Victora et al. (2004) argue that strategies like IMCI require close management of health workers [32]. Results from our study have, however, shown that health worker performance has not been assessed regularly as minimal IMCI-focused super- vision takes place, partly due to the lack of a supervisory checklist incorporating IMCI. Consequently, IMCI case management observations are almost never conducted, and district managers may not be informed by health workers of the challenges faced at facility level. Poor information on health worker adherence to proto- col is further exacerbated by the information asymmetry which exists between district managers and health workers. Moreover, IMNCI is a holistic approach to treatment which focuses on health worker treatment and case man- agement skills; therefore, it is inherently difficult to mo- nitor adherence to protocol using simple monitoring indi- cators, in contrast to other interventions, such vaccina- tions, where implementation is more easily tracked through routine records. The issue of information asymmetry is a factor influ- encing relationships between the national and district levels. The health department is not able to monitor pre- cisely the level of effort and supervision put into imp- lementing IMCI by district managers and staff. Moreover, many national level stakeholders lack a complete under- standing of implementation difficulties happening on the ground. One possible factor explaining the one-sided flow of information is the organizational work culture where information tends to flow mainly in a top-down manner. We have argued that asymmetry of information gives health workers the opportunity to deviate from the pro- tocol but this then begs the question—where health workers have been trained on IMCI why are they choos- ing to not implement the strategy? A key reason is likely to be the increased workload that IMCI adherence is perceived to produce. In addition, on top of their daily clinical duties, health workers might have other pressures in the workplace, such as adminis- trative duties, which could explain non-adherence to the guidelines. We can also postulate that health workers feel that there is no clear, added benefit to them in adopting IMCI skills: health workers are awarded certificates at the end of training but there are no tangible benefits to implementation in the form of career progression or re- muneration. The situation may be similar for district managers, especially those who have not been properly sensitized to the strategy. In some cases, managers may fail to recog- nize societal benefits of implementing IMCI, resulting in minimal supervision of IMCI i mplementation at facilities. Moreover, there are no direct incentives to encourage good IMCI performance at the district lev el. In addition to the impact on health worker and district manager behavior, the lack of visibility of IMCI imple- mentation means that routine data are not available on the achievements of IMCI, in process or impact terms. The lack of these data is reported to be one factor leading to declined interest in providing IMCI funding. Collec- ting it would have required additional studies, which were not put in place, perhaps reflecting a lack of appre- ciation of the importance of demonstrating impact. The top down hierarchical use of power may lead to poor communication of challenges and low motivation which, in turn, leads to little or no problem-solving (a form of non-decision-making), reflecting the lack of policy ownership amongst IMNCI implementers. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IIM  O. P. SINGH, S. KUMAR 205 Finally, limited facility autonomy in resource alloca- tion has led to facilities having no capacity to replace es- sential equipment, such as thermometers, or purchasing recommended drugs during stock-outs. All of these inf- luences may also be underpinned by street-level burea- ucracy (SLB) behavior, as health workers respond to their demanding environments by adopting coping mech- anisms to manage workloads and challenge domination from above. 5. Conclusions and Future Work Although everyone recognizes that improving health sys- tems is an important aspect of making health services more responsive and more effective, people do not al- ways agree about which interventions will produce these results. Management systems convert the materials and resources needed to carry out an implementation plan (“inputs”, such as money, equipment, staff time, and expertise) into activities (“outputs”, such as training pro- grams, information, or behavior change communica- tions). The management components key to program ef- fectiveness is not independent and change in one of the parameters may influence the other parameters too. The health system relies on overlapping and interconnected management systems and subsystems. Changes in one system can trigger changes in another system—changes that might go undetected until they cause trouble. For example, moving an organization’s financial manage- ment system onto computers might mean that financial reports take less time to prepare and, therefore, might lead to new responsibilities for staff or perhaps a reduc- tion in accounting staff. In this instance, the human re- source management system needs to be involved to sup- port the changes in the financial management system. Public health interventions tend to be complex, pro- grammatic and context dependent. The evaluation of evi- dence must distinguish between the fidelity of the eva- luation process in detecting the success or failure of the intervention, and relative success or failure of the inter- vention itself. The evaluation of an intervention’s should be matched to the stage of development of that inter- vention. The evaluation should be also designed to detect all the important effects of intervention and to encap- sulate the interest of all the important stakeholders. We advocate their incorporation into criteria for appraising evidence on public health interventions. This can streng- then the value of evidence and their potential contri- butions to the process of public health management and social development. 6. Acknowledgements First of all, I sincerely want to thank my supervisor Dr. Santosh Kumar for his gu idance, support and encour age- ment. He gave me constructive criticism as well as re- warding praises, which motivated and trained me to im- prove the quality of my research. I would like to ack- nowledge Professor S. C. Dwivedi for motivating and guiding me to in completing this work. I am thankful to my ex and current colleagues working with Directorate of Medical and Health Services, Go- vernment of Rajasthan and United Nations Fund for Children for providing their insight and support in com- pleting the thesis work. I would like to acknowledge my supervisors for extending their support in completing th e research work. I am thankful to all program managers, consultants, trainers, auxiliary nurse midwifes and ASHAs for actively participating in the research. REFERENCES [1] WHO, “Improving Performance,” The World Health Re- port, World Health Organization, Geneva, 2000, p. 151. [2] A. B. Zwi, “How Should the Health Community Respond to Violent Political Conflict?” PLoS Medicine, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2004, p. e14. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0010014 [3] P. Bolton, J. Bass, L. Murray, et al., “Expanding the Scope of Humanitarian Program Evaluation,” Prehospital & Disaster Medicine, Vol. 22, No. 5, 2007, pp. 390-395. [4] B. A. Weisbrod, “Costs and Benefits of Medical Research: A Case Study of Poliomyelitis,” Journal of Political Eco- nomy, Vol. 79, No. 3, 1971, pp. 527-544. [5] D. S. Shepard, L. Sanoh and E. Coffi, “Cost-Effectiveness of the Expanded Programme on Immunization in the Ivory Coast: A Preliminary Assessment,” Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 22, No. 3, 1986, pp. 369-377. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(86)90136-X [6] R. E. Glasgow, T. M. Vogt and S. M. Boles, “Evaluating the Public Health Impact of Health Promotion Interven- tions: The RE-AIM Framework,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 89, No. 9, 1999, pp. 1322-1327. doi:10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1322 [7] L. Gilson, “Discussion in Defense and Pursuit of Equity,” Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 47, No. 12, 1996, pp. 1891-1896. [8] E. A. Suchman, “Evaluative Research: Principles and Practice in Public Service and Social Action Programs,” Russell Sage Foundation, New York, 1967. [9] E. I. Struening and M. Guttentag, “Handbook of Evalua- tion Research,” Sage Publishing, Thousand Oaks, 1975. [10] L. W. Green, M. W. Kreuter, S. G. Deeds and K. B. Par- tridge, “Health Education Planning: A Diagnostic Ap- proach,” Mayfield, Mountain View, 1980. [11] R. A. Windsor, T. Baranowski, N. Clark and G. Cutter, “Evaluation of Health Promotion and Education Pro- grams,” Mayfield, Mountain View, 1984. [12] S. H. Starr, “C4ISR Assessment: Past, Present, and Fu- ture,” 8th ICCRTS, Washington DC, 17-19 June 2003. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IIM  O. P. SINGH, S. KUMAR Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IIM 206 [13] N. Sproles, “Establishing Measures of Effectiveness for Command and Control: A Systems Engineering Perspec- tive,” DSTO Report, DSTO.GD-0278, Fairbairn, 2001. [14] J. T. Dockery, “Why Not Fuzzy Measures of Effective- ness?” 11th ICCRTS Coalition Command and Control in the Networked Era, Cambridge, 3-4 May 1986. [15] N. Smith and T. Clark, “An Exploration of C2 Effective- ness: A Holistic Approach,” 2004 Command and Control Research and Technology Symposium, San Diego, 15-17 June 2004. [16] N. Sproles, “Formulating Measures of Effectiveness,” System Engineering, Vol. 5, No. 4, 2002, pp. 253-263. doi:10.1002/sys.10028 [17] B. Berg, “Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences,” 4th Edition, Allyn and Bacon, Boston, 2001. [18] Experiment-Resources.com., 3 May 2012. http://www.experiment-resources.com/experimental-resea rch.html [19] A. Maynard, “Evidenced-Based Medicine: An Incomplete Method for Information Treatment Choices,” Lancet, Vol. 349, No. 9045, 1997, pp. 126-128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)05153-7 [20] R. H. Moos, “Understanding Program Environments. New Direction in Program Evaluation,” 40th Jossey Bass Higher Education and Social and Behavioral Sciences Series, San Francisco, 4 March 2008, pp. 7-24. [21] C. Potter and R. Brough, “Systemic Capacity Building: A Hierarchy of Needs,” Health Policy and Planning, Vol. 19, No. 5, 2004, pp. 336-345. doi:10.1093/heapol/czh038 PMid:15310668 [22] S. Simmonds and N. Bennett-Jones, “Human Resource Development: The Management, Planning, and Training of Health Personnel,” Health Policy and Planning, Vol. 4, No. 3, 2005, pp. 187-196. doi:10.1093/heapol/4.3.187 [23] M. A. Schellenberg Jr., D. B. J. de Savigny, T. Lambre- chts, C. Mbuya, L. Mgalula and K. Wi lczynska, “The Ef- fect of Integrated Management of Childhood Illness on Observed Quality of Care of Under-Fives in Rural Tan- zania,” Health Policy and Planning, Vol. 19, No. 1, 2004, pp. 1-10. [24] G. W. Pariyo, E. Gouws, J. Bryce and G. Burnham, “Im- proving Facility-Based Care for Sick Children in Uganda: Training Is Not Enough,” Health Policy and Planning, Vol. 20, No. 1, 2005, pp. i58-i68. doi:10.1093/heapol/czi051 PMid:16306071 [25] S. Arifeen, “With Benefit of Hindsight: Policy and Pro- gram Lessons from the MCE,” Key Findings from the Multi-Country Evaluation of IMCI Effectiveness, Cost and Impact (MCE) ICCDDR, B, Centre for Health and Population Research, Mexico City, 2004. [26] J. Amaral, A. J. Leite, A. J. Cunha and C. G. Victora, “Impact of IMCI Health Worker Training on Routinely Collected Child Health Indicators in Northeast Brazil,” Health Policy and Planning, Vol. 20, No. 1, 2005, pp. i42-i48. doi:10.1093/heapol/czi058 PMid:16306068 [27] L. Huicho, M. Davila, M. Campos, C. Drasbek, J. Bryce, and C. G. Victora, “Caling up Integrated Management of Childhood Illness to the National Level: Achievements and Challenges in Peru,” Health Policy and Planning, Vol. 20, No. 1, 2005, pp. 14-24. [28] A. Rowe, F. Onikpo, M. Lama, F. Cokou and M. S. Dem- ing, “Management of Childhood Illness at Health Facili- ties in Benin: Problems and Thei r Cause s,” Ame rican Jou r- nal of Public Health, Vol. 91, No. 10, 2001, pp. 1625- 1635. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.10.1625 [29] J. Nsungwa-Sabiiti, G. Burnham and G. Pariyo, “Imple- mentation of a National Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) Program in Uganda,” Journal of Health and Population in Developing Countries, 2004, pp. 5-15. [30] K. Buse, N. Mays and G. Walt, “Making Health Policy,” Open University Press, Maidenhead, 2005. [31] C. G. Victora, L. Huicho, J. J. Amaral, J. Schellenberg, F. Manzi, E. Mason and R. Scherpbier, “Are Health Inter- ventions Implemented Where They Are Most Needed? District Uptake of the Integrated Management of Child- hood Illness Strategy in Brazil, Peru and the United Re- public of Tanzania,” Bulletin of the World Health Or- ganization, Vol. 84, 2006, pp. 792-801. doi:10.2471/BLT.06.030502

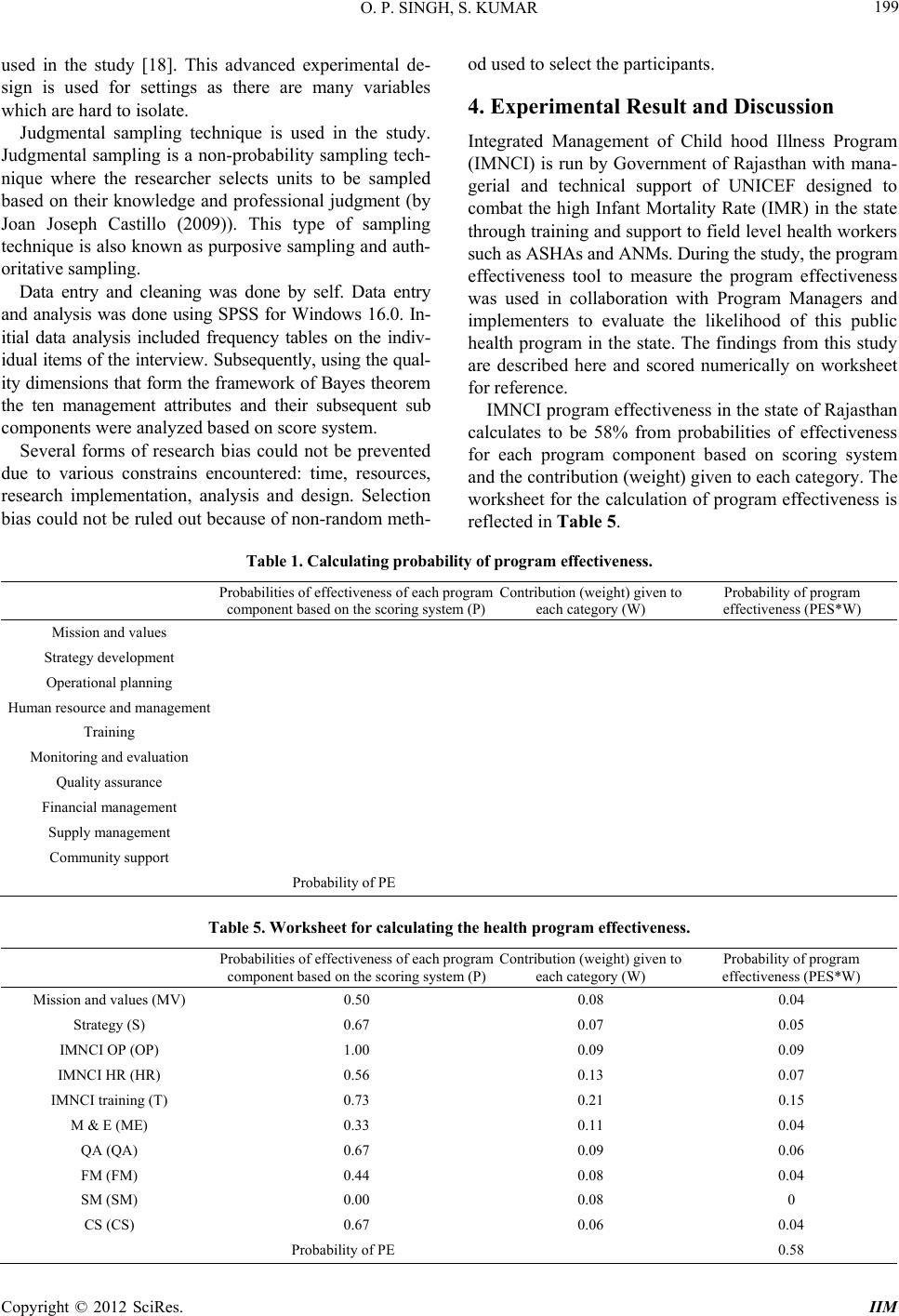

|