Open Journal of Modern Linguistics 2012. Vol.2, No.3, 105-113 Published Online September 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojml) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2012.23014 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 105 Paradigm Consistency and the Depiction of Stiltedness: The Case of than I versus than me Douglas J. Wulf Department of English, George Mason Univer sity, Fairfax, USA Email: dwulf@gmu.edu Received July 1st, 2012; revised August 2nd, 2012; accepted August 10th, 2012 Close adherence to prescriptive rules of grammar can sometimes produce stilted language, which can im- part to language a pompous or stuffy impression. It is ironic that an island of potential unacceptability can arise within what is regarded as Standard English. In instances where prescriptive grammaticality and so- ciolinguistic appropriateness are in opposition, disagreements over language use can occur. Despite its impact, stiltedness has received little scholarly attention, probably because it is an intangible, subjective phenomenon. This paper investigates an indirect way to depict stiltedness through a quantitative measure. The example selected to demonstrate this approach is the rule of bare pronouns in comparative sentences. With tangible quantitative measurements of paradigm consistency and inconsistency, stiltedness may perhaps be understood more effectively. Keywords: Modern English; Grammar; Prescriptive Grammar; Errors of Usage; Correctness; Stiltedness; Ambiguity; Applied Linguistics Introduction My inspiration for investigating stiltedness was a dispute I was asked to help resolve between a high-school English teacher and a parent over the “correct” pronoun choice for He is taller than (I/me). The teacher had told the class that although I is often mandated in grammar books, me is also frequently used. Hearing about the lesson, the parent insisted that only I is per- missible, since this pronoun is mandated by “the rules”. The situation became surprisingly rancorous, escalating to involve the principal and school board. The parent held firmly to guidance from Strunk, White, & Angell (2000: p. 12): “A pronoun in a comparison is nominative if it is the subject of a stated or understood verb”, illustrated by their example Sandy writes better than I (Than I write). Similar considerations ap- ply to use of as, as in Sandy writes as well as I (As well as I write), rather than Sandy writes as well as me. However, the teacher surveyed her coworkers, and the unanimous impression was that use of me likewise seemed acceptable and perhaps even preferable in some circumstances. However, because the parent was able to cite a reference grammar whereas the teacher only had the general impressions of ordinary language users, the school district’s curriculum specialist came down strongly in favor of the parent’s position. The parties in this dispute were not aware that the battle over than has been waged for centuries, and, as Sherwin (2000) notes, “Tensions on the matter continue” (p. 544) in what he describes as “the definition of a no-win situation” (p. 545). The battle has also been waged in the popular press. A letter writer to Barbara Wallraff’s “Word Court” in Atlantic Monthly (2004: p. 184) expresses the perennial anxiety. Hearing “I was better than her” and “I was wondering if this time my dog did better than me” on television, the writer complains: “Than is a con- junction, never a preposition. It ties two clauses together. The verb is understood in the second clause: ‘I was better than she (was).’ Am I being old-fashioned? Have the rules changed?” The parent asked me, “Which pronoun is correct, and what are the relevant points of grammar? Are both correct? Not in street language, or according to the newest esoteric musings on the subject, but according to the most widely accepted authori- tative view” (Personal e-mail communication, 15 November 2005). As the parent saw it, what I will call the traditional rule, as described above by Strunk, White, & Angell (2000), pro- vided the “authoritative view” and that beyond this, there could only be found “esoteric musings”. Yet, one such “musing” is a corpus-based study from Long- man Grammar of Spoken and Wri tten English (Bib er et al., 1999: pp. 336-337) measuring compliance with the traditional rule. This study found that it is followed less than 2.5% of the time, below the lowest frequency measured in the study. The meas- urement was therefore so low as to be statistically equivalent to 100% violation. That the teacher and her coworkers were “in- correct”, thus makes them typical speakers of English. In fic- tion writing, compliance was found to be 45%, so a slight ma- jority of fiction writers also violate the rule. Application of the rule in news and academic writing was not measurable in the study, since examples of either bare-pronoun variant were found to be “extremely rare”. In such formal texts, “writers frequently opt for a full comparative clause… thereby avoiding a choice between a nominative and an accusative form”. Indeed, Strunk, White, & Angell (2000) make the following important addendum: “In general, avoid ‘understood’ verbs by supplying them” (p. 12). Thus, the full advice from this manual is indeed to bypass either bare-pronoun option Sandy writes better than (I/me) in favor of Sandy writes better than I write or, less redundantly, than I do. Yet, this same advice seems to vio- late one of the manual’s basic elements of style: “Omit needless words” (p. 23). The manual states, “A sentence should contain no unnecessary words… for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unneces-  D. J. WULF sary parts” (p. 23). Though much has been written about grammaticality and its relationship to language standardization, far less scholarly at- tention has been paid to the phenomenon of stiltedness. Curi- ously, what strikes us as stilted does not seem directly predict- able just by comparing actual usage with the prescriptive stan- dard. For example, many prescriptive grammarians have pro- moted the use of different from over different than, as in Americans are different from Europeans, instead of Americans are different than Europeans. Yet, unlike the prescriptive than I variant, the prescriptive variant different from here does not seem stilted. However, stiltedness may still play some role in the different (from/than) selection also. For example, Merriam- Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (2003) notes that than is “… recommended in many handbooks when followed by a clause, because insisting on from in such instances often produces clumsy or wordy formulations. Different from, the generally safe choice, is more common especially when it is followed by a noun or pronoun” (Different, 2003). In any event, language is clearly not automatically stilted simply because it conforms to prescriptive guidelines, even prescriptive guidelines uncom- monly employed in colloquial usage. A better grasp of the phenomenon of stiltedness might help us better understand why closely following a prescriptive stan- dard sometimes seems fine, but at other times produces lan- guage described as “clumsy”, “wordy”, “awkward”, or similar negative judgments. It is ironic that an island of potential unac- ceptability actually arises within Standard English simply by consistently following prescriptive rules. A good working defi- nition of stilted language, as we use the term here, is thus lan- guage that the standard rules describe as correct, yet which native speakers of the language find unacceptable and therefore actively avoid using . Despite the pivotal role that stiltedness can play in cases of disputed usage, it is perhaps because stiltedness is an intangible, subjective phenomenon that scholars may regard it as not ame- nable to precise study. We may regard stiltedness as one of ma- ny factors within the broader notion of appropriateness (a.k.a., acceptability). In the generative tradition, Chomsky (1965) marginalized the importance of studying such factors and ar- gued, “Acceptability is a concept that belongs to the study of performance, whereas grammaticalness belongs to the study of competence” (p. 11). Reacting to this, Hymes (1971) proposed the notion of communicative competence which, among other considerations, argued that a competent language user not only makes judgments of grammaticality, as Chomsky maintained, but also recognizes the appropriateness of an utterance in a given communicative context. With regard to l anguage teaching, Canale & Swain (1980) introduced the term sociolinguistic competence to label the component of appropriateness within communicative comp etence. Yet, in such discussions of acceptability from the functional- ist, anthropological, and applied traditions, the focus is often on utterances that are potentially deviant lexically, as with meas- uring reactions to the inventively poetic sentence Friendship dislikes John from the study of Quirk & Svartvik (1966), or on specific dialectal forms, such as the sentence I saw them big spiders from the study of British urban dialects in Milroy & Milroy (1993). By contrast, stiltedness is unacceptability that potentially arises simply by consistently following the prescrip- tive rules advocated for Standard English. Given its subjective nature, there seems to be no reliable way to measure stiltedness in some direct way. That said, it occurs to me that there might exist strategies involving quantitative measures that may indirectly inform us about stiltedness, or at least of its influence. Obviously, the corpus-based statistics on usage provided in Biber et al. (1999) is one such indirect quan- titative measure. That is, it is useful to note that native speakers generally violate the traditional rule involving than or else de- liberately avoi d the construction entirely. However, additional measurements, as I explain in this paper, can be made regarding the internal paradigm consistency or inconsistency expressed by those indicating support for use of a given prescriptive rule. Measurements of paradigm inconsis- tency indeed serve as useful data alongside corpus-based statis- tics of actual usage. These measurements, as I outline below, could be employed in further investigations of linguistic phe- nomena related to stiltedness that have implications for social psychology and othe r a r ea s . If language users perceive a rule as producing stilted lan- guage, even if they may favor use of the rule in some cases, they can still exhibit paradigm inconsistency overall in applying the rule to many different queried examples across the para- digm of usage instances. I therefore conducted a small survey specifically concerning preferences in pronoun use after than. My purpose was to use this case to illustrate how stiltedness could be depicted via paradigm inconsistency involving a par- ticular rule of grammar. As far as I can determine, no attempt to depict stiltedness indirectly in this or in some similar quantita- tive way has previously been proposed. The Nature of the Controversy Before discussing the survey and its results, it is useful briefly to explore the nature of the controversy over than in a bit more detail. Many older grammar references can be found that strongly defend the traditional rule. For example, Haber- stroh (1931) states, “The Personal Pronouns… cause a great deal of trouble. Yet they need not. Remember simply that I is always the subject and in the Nominative Case, and Me is al- ways in the Objective Case” (p. 54). He contrasts the following examples: Incorrect: You are taller than him/Correct: You are taller than he (is) (pp. 56-57). Stratton (1940) asserts, “Only ignorant persons follow than with the objective form of the pronoun She is taller than him. Even though this usage can be found in books of the past, it is not correct. If the understood verb is expressed, the sentence reads She is taller than him is— evident nonsense” (p. 323; also quoted in Brame, 1983: p. 323). As the letter writer to Walraff’s column describes the tradi- tional rule: “Than is a conjunction, never a preposition”. However, the traditional view has also long been called into question. Nesfield (1939) observes that although “in some books on Grammar the prepositional character of than is de- nied… [there are constructions in which] “than” must still be parsed as a Preposition, because there is no Finite verb under- stood which could make it a Conjunction” (pp. 76-77). Nesfield cites I will not take less than ten shillings and No one other than a graduate need apply. In neither of these can we produce an “understood” verb to expand the expression into a full clause. Therefore, using pronouns, the sentences above would need to be I will not take less than them and No one other than him or her need apply. As Haase (1949) maintains, “the purists in their attempt to eradicate the use of expressions such as than me have overlooked the use of than as a preposition in other con- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 106  D. J. WULF texts…” (p. 347). Huddleston & Pullum (2002) state that “there are unquestionably some constructions where a single element following than/as is an immediate complement, not a reduced clause” (p. 1114). Examples include It is longer than a foot and He’s inviting more people than just us, which cannot be ex- panded with an “understood” verb. In short, than is undeniably both a conjunction and a preposition, though its use as a prepo- sition has actively been suppressed in Standard English. The traditional rule against prepositional than seems based on the notion that than should not be ambiguous between two parts of speech, but there is no intrinsic problem with a word functioning both as a conjunction and as a preposition. DeRose (1988) observes that part-of-speech ambiguity “pervades Eng- lish to an astonishing degree” (p. 31). Although most words in English are associated with just a single part of speech, many of the most common words exhibit part-of-speech ambiguity. Spe- cifically, DeRose (1988) found that although 88.5% of word types in his corpus study had a single part-of-speech tag only, 40% of word tokens encountered in any given text passage were associated with more than one part-of-speech tag. Thus, a computer tagging words in a text for parts of speech must choose between multiple part-of-speech options for approxi- mately 40% of words encountered. In particular, note that after (or before) can be either a con- junction, as in I left after he left, or a preposition, as in I left after him. The acceptability of dual parts of speech for after and before in Standard English is noted by Huddleston & Pullum (2002: pp. 1116-1117), where it is also indicated that the corre- sponding reduced-clause variants are disallowed, as in *I left after he. Brame (1983: p. 328) asks, “But why can’t this analy- sis work for than and as as well? Why can’t than and as have dual functions just as does after?” In fact, there is no principled reason why this could not be. Brame (1983) notes that “children naturally acquire she is taller than him… but have to be drilled or instructed or tortured to produce she is taller than he… ” (p. 325), so Brame sees the stiltedness of the bare subject-pronoun variants as an attitude arising as part of the normal acquisition of English by native speakers. We indeed have here a plausible explanation as to why fol- lowing the traditional rules can lead to impressions of stilted- ness. For ordinary English speakers, than and as have the same part-of-speech options as do before and after: they can be both conjunctions and prepositions. It is reasonable to surmise that I am taller than he seems grammatically odd for analogous rea- sons to the oddness of *I left after he. In I left after him, after functions as a preposition that takes the object pronoun and not as a conjunction introducing a reduced clause with a bare sub- ject pronoun. Use of the subject pronoun in I am taller than he thus goes against the grain of the way a normal speaker of Eng- lish understands the word than to work at a subconscious level. By contrast, using the prescriptive I am different from him in- stead of the colloquial I am different than him simply involves swapping the preposition from for what speakers take to be another preposition: than. The result is therefore not stilted. However, care and additional wording is required to retain the preposition from in cases where we need to introduce a clause and where than as a conjunction would be handy to use. Thus, France is different than I expected is often preferred to France is different from what I expected (it would be). Given the uphill battle against prepositional than, references on style and commentators on Standard English have more recently started to relent. For example, the Columbia Guide to Standard American English states: Than is both a subordinating conjunction, as in She is wiser than I am, and a preposition, as in She is wiser than me. As subject of the clause introduced by the conjunction than, the pronoun must be nominative, and as the object of the preposition than, the following pronoun must be in the objective case. Since the following verb am is often dropped or “understood”, we regularly hear than I and than me… but both are unquestionably Standard (Wilson, 1993: pp. 433-434). Likewise, Trudgill (1999) states, “Standard English does not exclude… He is taller than me” (p. 125). Carter & McCarthy (2006) maintain, “When than is followed by a personal pronoun acting as the head of a noun phrase, the object forms (me, him, her, us, etc.) are used” (p. 764). They provide the example My sister is prettier than me. The text indicates that than I am is also permissible, but draws a line through the variant My sister is prettier than I. On the other hand, some references still up- hold the traditional view. For example, The Oxford English Dictionary (Than, 1989) states that use of than as a preposition taking the objective pronouns “… is now con s i dered incorrect”. In reaction to this confusion, Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (2003) offers the following advice: After 200 years of innocent if occasional use, the preposi- tion than was called into question by 18th century gram- marians. Some 200 years of elaborate and sometimes tor- tuous reasoning have lead to… present-day inconsistent conclusions… [Therefore, you] have the same choice Shake- speare had: you can use than either as a conjunction or as a preposition (Than, 2003). Yet, this guidance is less than ideal because rules of grammar and usage are ordinarily designed to uphold a single option among a set of variants. As Milroy (2000) argues: [T]he chief linguistic consequence of successful standar- dization is a high degree of uniformity of structure. This is achieved by suppression of “optional” (generally socially functional) variation… [W]hen two equivalent structures have a salient existence in the speech community… one is accepted and the other rejected—on grounds that are lin- guistically arbitrary, but socially non-arbitrary (p. 13). Thus, the advice from Merriam-Webster, while it may seem liberating, fails to provide clear guidance, and it is in just such disputed cases where language users look to a reference for a definite ruling of which form is the “correct” one. Quirk et al. (1985) identifies the reason that supplying an “understood” verb is necessary, noting that “the subject pro- noun on its own, such as she in “He is more intelligent than she”, sometimes gives a stilted impression, and it is preferable to add the operator after it: she is” (p. 335). Sherwin (2000) likewise notes with regard to confronting the two problematic bare-pronoun alternatives, “Not surprisingly, people rephrase to avoid having to make a choice” (p. 545). It seems to me that additional light may be thrown on this matter from the survey data on paradigm consistency that I collected, as described in the following section. If language users perceive a rule as producing stilted language, even if they may favor use of the rule in some cases, they may still exhibit less internal consistency overall in applying the rule to many different queried examples across the paradigm of usage in- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 107  D. J. WULF stances. The purpose of my survey was to use the case of than usage to illustrate how stiltedness could be depicted indirectly via paradigm inconsistency in the implementation of this par- ticular rule of grammar. The Survey I conducted an online survey at Surveymonkey.com, using comparative sentences such as He is taller than (I/me) as cen- tral examples for investigation. The questions and response percentages are shown in the appendix. Respondents were re- quired to answer each multiple-choice question before viewing the next and could not revise previous responses. I asked indi- viduals from many different walks of life to participate. Via online contacts, I found respondents from various geographical areas, including outside the United States. I asked participants to ask others to participate, and the last page of the survey also requested that respondents invite others to take the survey. Of those who completed the entire survey, 438 indicated being native speakers of English. Only responses from these indi- viduals were used. Indeed, being a native speaker of English was deliberately the only demographic factor considered. Textbooks and gram- mar references that might inform us about stiltedness are typi- cally written for a general audience. This is either native speak- ers (irrespective o f gender, ethnicity, region, so cio-economic s tatus, age, and other demographic divisions) or second-language lear- ners of English who, again irrespective of their backgrounds, are attempting to emulate some normative version of English. Thus, advice on stiltedness would at least be idealized as usable by individuals in any demographic group when communicating with individuals in any demographic group. Consequently, I sought respondents who might or might not have anything in common other than being native speakers of English. The survey’s goal was not to measure the genuine level of adherence to the traditional rule. The Longman study already accomplishes this, demonstrating that the traditional rule is generally avoided or violated. For that matter, Williams (1981) discusses surveys on language and indicates that “… we are not always our own best informants about our habits of speech. Indeed, we are likely to give answers that misrepresent our talking and writing, usually in the direction of more rather than less conservative values” (p. 154). Therefore, I assumed from the outset that the absolute percentages measured could be mis- leading, portraying stronger support for the traditional rule than actually ex ists. Similarly, although certainly a valuable issue to explore, the survey was also not designed to correlate usage preferences with the level of education of survey respondents or with train- ing respondents may have had as professional writers or editors. Here again, the Longman study already gives us insight. In news and academic writing, both bare-pronoun options are ex- tremely scarce. Thus, those skilled at writing are clearly aware both of the dilemma and of its optimal solution. The object pronoun is not stilted, but “incorrect”, and the subject pronoun is “correct”, but stilted. By contrast, the full clause option is neither “incorrect” nor stilted. Skilled writers therefore know how to avoid the problem entirely. My primary aim was rather to attempt to make the issue of stiltedness more tangible by examining the internal consistency of answers provided. To clarify, in cases where the survey pre- sents a series of grammatically parallel sentences, one directly after another, one might suppose that respondents would remain consistent in their application of or violation of a given rule of grammar. The desire to be consistent should exert some pres- sure on respondents irrespective of what their rule preferences happen to be. There would thus be a group that favors use of prepositional than, as in He’s taller than me, and these individuals might then be expected consistently to favor object pronouns in parallel examples also, such as preferring I’m taller than her. Let us regard this as the non-traditional group. There would also be grammatically traditional individuals that prefer He’s taller than I. If consistent, these individuals would also favor I’m taller than she. My online survey did indeed reveal self-re- ported groups of consistently non-traditional and consistently traditional language users on this point of grammar in the first four survey questions. When queried about conversational pre- ferences, the consistently non-traditional group was 62.6% of respondents and the c on s i st e ntly traditional group was 13.2%. However, my survey crucially discovered that 24.2% of re- spondents were inconsistent in their answers to the four parallel questions concerning conversational preferences of pronoun choice. That nearly a fourth of respondents switched between subject and object forms in these grammatically parallel sen- tences indicates a substantial level of vacillation and uncer- tainty in the choice of bare-pronoun options for such compara- tive sentences. In particular, support for the traditional rule collapses over the course of the first four questions. 29% favored He’s taller than I in the first question, but only 24.2% favored I’m taller than she in the very next question. Support for He’s taller than they was only 22.1%, and a preference for He’s taller than we was just 16.7%. As noted, the survey’s measure of consistent use of the traditional rule in the first four questions was only 13.2%. Although 29% selected the subject pronoun in the first question, less than half this percentage actually remained con- sistent to the traditional rule underlying this selection over the course of three subsequent parallel survey questions. Those that use, for example, than I but not than we perhaps feel compelled to pay lip service to the traditional rule by employing it in the context of the often-cited first-person singular examples (e.g., He is taller than I), but they have not internalized the rule of consistently treating than as a conjunction that introduces a reduced clause. For these speakers, than is still a preposition and use of the subject pronoun represents an unnatural altera- tion forcibly shoehorned into use. Mathematically, there are 12 possible combinations in which the first four questions might be answered inconsistently. Nota- bly, 30.2% of those respondents who were inconsistent in an- swering these questions selected I for the first question and object pronouns for the next three questions, and 13.2% se- lected subject pronouns in the singular and object pronouns in the plural. Adding these two largest subgroups, we note that 43.3% of inconsistent respondents avoided the traditional rule in the plural. By contrast, not a single respondent selected me, her, we, they (i.e., object pronouns in the singular and subject pronouns in the plural). Again, I suspect that even the anemic 16.7% support for than we is greatly inflated by the tendency to traditionalism in answering surveys, as noted by Williams (1981: p. 154), as well as to the pressure to remain consistent. That said, I am not drawing conclusions from the absolute per- centages measured, but rather from trends of consistency and inconsistency. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 108  D. J. WULF In an optional comments section, numerous respondents com- plained about being forced to choose only between bare-pro- noun options. Respondent 26 stated, “In the first section… I was frustrated because I would choose neither of those ways. I would speak grammatically, but in a more idiomatic manner than the grammatical choice given”. Respondent 45 wrote, “The first few questions didn’t work well for me because I couldn’t answer honestly. I wouldn’t say ‘He is taller than me,’ or ‘He is taller than I’”. Respondent 44 commented, “You need more options in your questions—or at least a button that says ‘I wouldn’t say either of the above’.” Respondent 109 stated, “I appreciate the difficulty of ‘either/or’ survey questions, but the first several that ask for spoken English only give sentences that I probably wouldn’t use, so I was forced to pick th e ‘least bad’.” Of course, my aim was indeed to force respondents to pick be- tween these bare-pronoun options, not allowing the full-clause variant as a way to avoid the difficulties both bare pronouns pose. Respondent 109 actually suspected this and added, “May- be that was the point, but as a respondent, it’s a little frustrating. I suppose the relevant distinction was picked up with the formal writing questions”. Indeed, later in the survey, respondents are offered an addi- tional choice. Presented with the scenario of editing a formal report and confronted with He is taller than me, only 12.8% would leave this sentence unchanged. Although 33.8% would correct this to He is taller than I, a 53.4% majority would change this to He is taller than I am, explicitly supplying the “understood” verb in conformity with the complete advice from Strunk, White, & Angell (2000). The full-clause variant simi- larly won out in the three remaining cases. In third-person ex- amples, 55.3% favored this in the singular and 62.1% in the plural. Likewise, 62.3% would change He is taller than us to the full-clause option. The traditional rule ran a distant second place in three of the four instances, but in the case of He is taller than us, 23.3% would leave the sentence unchanged and only 14.4% would replace this with He is taller than we. In summary, in all four items querying use of the traditional rule in conversation, although not in the overwhelming per- centages measured in actual usage by Longman, respondents nonetheless reported a strong preference for the object-pronoun variants. However, for respondents selecting He’s taller than I in the first question, it proved challenging to remain faithful throughout the next three questions to the rule that underlies this choice. In all four questions concerning editing a formal report, the majority chose to avoid either bare-pronoun option in favor of rewording each sentence with a full clause. Given the trend of complaints logged in the comments section, we may surmise that some careful speakers would prefer to avoid bare-pronoun options also in conversation and instead use the full clause or some other rewording. The subject-pronoun variants are disfavored in practice, but t here is likewise a measurable aversion to voicing across-the- board support for the application of the traditional rule even by those who are comfortable with its application in some instances. The most plausible reason why a respondent would be inconsistent in applying the traditional rule is that although attempting to follow the traditional rule, the respondent finds some responses too stilted to select. Thus, Respondent 116 commented, “While correct, many of the ‘than I, than we, than she’ constructions sound so prissy and antiquated to me that I would not want to say or write them”. However, effective use of the traditional rule might be applicable in cases in which the audience would itself possibly be its supporters, as Respondent 121 noted: “I always advocate using the form that fits the audience best. A more formal audi- ence—say, university faculty members—are likely to pride themselves on using the ‘correct’ subject pronoun, while their 18-year-old students are likely to think the subject pronoun sounds stiff and snobbish”. As we see from the comment sec- tion of this survey, respondents specifically noted avoidance of stiltedness as a key factor in making choices on this point of grammar. However, even beyond these comments, the percent- ages of consistent and inconsistent pronoun selection demon- strate compellingly that stiltedness is a real factor working in opposition to employment of the traditional rule for compara- tive sentences. Additional Survey Results In the survey, respondents were also presented with Every- one other than (she/her) left and I saw everyone other than (she /her). In neither sentence is it possible to expand the bare pro- noun after than into a full clause. We must therefore conclude that than is a preposition requiring the object pronoun her in both cases. When asked about pronoun preference in conversa- tional use, respondents reported a preference for the object pronoun in both. 72.1% preferred Everyone other than her left and 92.5% preferred I saw everyone other than her. However, when asked if I saw everyone other than her should be corrected in a formal document, 21.5% would advo- cate I saw everyone other than she, which is a hypercorrection. The tendency to hypercorrect was even stronger with Everyone other than her left, for which a 59.4% majority advocated re- placing this sentence with the hypercorrection Everyone other than she left. As I have noted, I do not regard percentages in my survey as accurate measures of how individuals genuinely use language in formal contexts. Corpus-based studies (e.g., Longman) pro- vide genuine measures of this sort. Rather, I am asking indi- viduals to self-report their preferences. The key finding here is that although a large majority expressed a conversational pref- erence for Everyone other than her left, it was also possible to coax 59.4% into thinking that it would be incorrect to use this same sentence in a formal context. Also, a significant 28.3% minority selected a hypercorrection of the grammatically stan- dard sentence The rain falls more on him than me even though the full clause variant expresses a nonsensical idea: The rain falls more on him than I (fall on him). The results again speak to a level of confusion and inconsistency in applying the tradi- tional rule or, in som e case s , a r t fully avoiding it. In answer to the letter writer to Atlantic Monthly, Wallraff (2004) specifically cites the phenomenon of ambiguity as a rationale for the traditional rule: The main reason not to welcome all prepositional uses of than, in my opinion, has to do with sentences like this one: “I like her better than him.” That’s clear, no? It means I prefer her to him. If we start allowing than to be either a preposition or a conjunction catch-as-catch can, soon that example will become ambiguous: do I prefer her to him, or do I like her better than he does? (p. 84). This argument is not new. Curme (1931) states, “The use of the accusative here should be avoided, for it is often ambigu- ous” (p. 304). Fowler (1937) writes, “It is obvious… that rec- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 109  D. J. WULF ognition of [than] as a preposition makes some sentences am- biguous that could otherwise have only one meaning, & is to that extent undesirable” (p. 629). Fowler associates preposi- tional than with the grammar of “an uneducated person”. However, results from the survey demonstrate that the tradi- tional rule does not have genuine power to disambiguate. Re- spondents were presented with the sentence I teach her French better than him. If the traditional rule actually disambiguates, we would expect the preferred interpretation to be equivalent to I teach her French better than I teach him French. That is, the writer of the sentence teaches two people and claims to be more successful teaching her than teaching him. In fact, only 35.2% selected this interpretation. 64.8% indicated that their first in- terpretation upon reading the sentence was equivalent to I teach her French better than he teaches her French. That is, she has two French instructors and the writer claims to be a better in- structor than the other instructor. Individuals who would rely on the traditional rule to disambiguate would be almost twice as likely to misunderstand or cause a misunderstanding than those who do not follow the traditional rule. Wallraff’s example of potential ambiguity was I like her bet- ter than him, and for this carefully selected example and with parallel use of object pronouns lined up, 92.3% indeed selected the interpretation I like her better t han I like hi m, in conformity with the traditional rule. However, for Jim hit more home runs than me, 96.3% preferred the interpretation Jim hit more home runs than the writer of the sentence hit, which is the interpreta- tion that runs counter to the traditional rule. Furthermore, only 1.4% of respondents thought that the writer of Al Smith repairs more radiators than us is communicating a nonsensical idea even though the traditional rule predicts that this sentence means Al Smith repairs more radiators than he repairs us. Al- though 74% noticed a grammatical error to be corrected, this was the final question in a survey containing many comparative sentences involving pronoun choice, so respondents would certain ly be particularly attune d to his point of grammar by then. In any case, this option also indicates that the sentence is com- prehensible even though it does not follow the traditional rule. Thus, language users do not rely in actual practice on the tradi- tional rule of pronoun choice to disambiguate. Rather, they recover the intended meaning by selecting the most plausible reading from the context whether this reading follows the tradi- tional rule or violates it. In summary, the practical utility of Wallraff’s disambigua- tion advice is undercut whenever the context favors the non- standard reading as the more plausible over the standard. The traditional rule often produces stilted sentences, but in an effort to encourage people to use this rule anyway, prescriptive gram- marians have advanced the notion that the traditional rule is useful for the purposes of disambiguation, but this is not true in any consistent or practical way. Conclusion Certain quantitative measurements indeed seem feasible in making stiltedness a more palpably real thing to examine. We can better consider the effects of stiltedness in opting against em- ploying a given rule of presc riptive grammar, which is obviously often a central point of tension in language use. There is a psy- chological struggle involved in the decisions we make to adhere consistently to a traditional rule of grammar, to violate it, or to be inconsistent in its application. There are social considerations also in being reg arded as excessi vely formal in o ur language use, or otherwise too casual. There are psy chological reactions, some- times reactions of anger, when others seem not to value the stan- dardized rules of language. However, it seems to me that by fo- cusing not solely on standardization of the rules but also on the importance of non-stilted language, we can better understand conflicts over language, such as the dispute between the parent and the teacher over pronoun use, and perhaps even pinpoint sensible solutions to such vexing debates in usage. Stiltedness indeed requires further study since it may be one of the central culprits behind the psychological disturbance that Liberman (2005) calls “word rage”. In those instances where the forces of prescriptive grammaticality and sociolinguistic ap- propriateness are in direct opposition, disagreements can arise, such as was evidenced by the parent’s heated dispute with the teacher. Liberman (2005) humorously describes “word rage” as “… reacting to perceived violations of linguistic norms with talk of chopping and stabbing and smashing”. Zimmer (2006) com- piles historical examples of the reactions of “word-rageaholics”, showing that extreme antagonism toward non-standard usage is not just a recent phenomenon. In addition, Williams (1981: p. 152) ponders the “unusual ferocity” that grammar violations can elicit. He notes how emotive words, such as “horrible” and “atrocious” (p. 153), typically only applied to the rudest be- havior, are also used to describe small deviations in grammar. He indicates that errors raise differing levels of ire and main- tains that “… we should be able to account better than we do for the variety of responses that different ‘errors’ elicit. It is a subject that should be susceptible to research” (pp. 153-154). On the one hand, there is a societal pull toward the strict ad- herence to clear rules of language use especially in formal con- texts. On the other hand, there is also a need to avoid stilted usage such as Here is the pen for which you were looking. The desire to avoid seeming pompous or stuffy in one’s communi- cation is indeed a powerful sociolinguistic force, as Curzan & Adams (2009: p. 404) humorously highlight by contrasting Standard American English (SAE) with “Stuck Up American English” (SUAE). As for resolving the difficulty surrounding the formation of comparative sentences such as He is taller than (I/me), the re- sults of the survey show that He is taller than me is preferred in colloquial usage and that He is taller than I is disfavored both in colloquial and formal usage. The variant strongly preferred in formal usage is He is taller than I am. Thus, the optimal usage rule could perhaps be stated as follows: Avoid “under- stood” verbs in comparatives where possible. Acknowledgements The author thanks Steven Weinberger, Charlie Jones, Fre- derick Newmeyer, Laurel Preston, and the anonymous reviewer of this manuscript for their guidance. The article was greatly improved as a result of their input. REFERENCES Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leach, G., Conrad, S., & Finegan, E. (1999). Longman grammar of spoken and written English. New York: Long- man. Brame, M. (1983). Ungrammatical notes 4: Smarter than me. Linguistic Analysis, 12, 323-338. Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1, 1- 47. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 110  D. J. WULF Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 111 doi:10.1093/applin/1.1.1 Carter, R., & McCarthy, M. (2006). Cambridge grammar of English: A comprehensive guide: Spoken and written English grammar and us- age. Cambridge, UK: CUP. Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press. Curme, G. O. (1931). Syntax. Essex, CT: Verbatim. Curzan, A., & Adams, M. (2009). How English works: A linguistic in- troduction (2nd ed.). New York: Pearson Longman. DeRose, S. J. (1988). Grammatical category disambiguation by statis- tical optimization. Computatio nal Linguistics, 14, 31-39. Fowler, H. W. (1937). A dictionary of modern English usage. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Haase, G. D. (1949). Than. College English, 10, 345-347. doi:10.2307/372680 Haberstroh, E. F. (1931). How to speak good English. Racine, WI: Whit- man. Huddleston, R., & Pullum, G. K. (2002). The Cambridge grammar of the English language. Cambridge, U K: CU P. Hymes, D. H. (1971). On communicative competence. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press. Liberman, M. (2005). Word rage outside the anglosphere? Language log (4 November 2005). URL (last checked 30 June 2012). http://itre.cis.upenn.edu/~myl/languagelog/archives/002625.html Merriam-Webster (2003). Merriam-Webster’s collegiate dictionary (p. 348, 11th ed.). Springfield, MA: Merr iam-Webster. Milroy, J. (2000). Historical description and the ideology of the stan- dard language. In L. Wright (Ed.), The development of standard Eng- lish, 1300-1800: Theories, descriptions, conflicts (pp. 11-28). Cam- bridge, UK: CUP. Milroy, J., & Milroy, L. (1993). Real English: The grammar of English dialects in the British isles. London: Longman. Nesfield, J. C. (1939). Manual of English grammar and composition. London: Macmillan. Quirk, R., Greenbaum, S., Leech, G., & Svartvik, J. (1985). A compre- hensive grammar of the English language. London: Longman. Quirk, R., & Svartvik, J. (1966). Investigating linguistic acceptability. The Hague: Mouton. Sherwin, J. S. (2000). Deciding usage: Evidence and interpretation. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. Stratton, C. (1940). Handbook of English. New York: McGraw-Hill. Strunk, W. Jr., White, E. B., & Angell, R. (2000). The elements of style (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Than. (1989). Def. 1b. In Oxford English dictionary (p. 861, 2nd ed., vol. 17). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Than. (2003). Def. 2. In Merriam-Webster’s collegiate dictionary (p. 1293, 11th ed.) . Springfield, MA: Merri am-Webster. Trudgill, P. (1999). Standard English: What it isn’t. In T. Bex, & R. J. Watts (Eds.), Standard English: The widening debate (pp. 117-128). London: Routledge. Williams, J. M. (1981). The phenomenology of error. College Compo- sition and Communication, 32, 152-168. doi:10.2307/356689 Wilson, K. G. (1993). The Columbia guide to standard American Eng- lish. New York: Columbia University Press. Wallraff, B. (2004). Wor d court. Atlantic Monthly, November 2004. Zimmer, B. (2006). Pioneers of word rage. Language log (5 March 2006). URL (last checked 30 June 2012). http://itre.cis.upenn.edu/~myl/languagelog/archives/002897.html  D. J. WULF Appendix. Survey and Survey Results Answer options in the survey are listed below not in the or- der they were viewed by survey takers, but rather from highest to lowest percentages selected. Part 1 From the options provided, indicate which version of the sentence you would be more likely to say in normal conversa- tion. You are not being asked what the “correct” usage is in formal language, but rather your honest view of how you think you would typically speak in the various situations described. % Number of respondents John is a professional basketball player. You say… He’s taller than me. 71% 311 He’s taller than I. 29% 127 Mary is a small child. You say… I’m taller than her. 75.8% 332 I’m taller than she. 24.2% 106 John is a basketball player and towers over you and your friend. You say… He’s taller than us. 83.3% 365 He’s taller than we. 16.7% 73 John is a basketball player and is the tallest member of his team. You say… He’s taller than them. 77.9% 341 He’s taller than they. 22.1% 97 You are asked why Jane was alone at the restaurant. You say… Everyone other than her left. 72.1% 316 Everyone other than she left. 27.9% 122 You are asked if you saw Jenny at the party last night. You say… I saw everyone other than her. 92.5% 405 I saw everyone other than she. 7.5% 33 Part 2 Suppose you are asked to edit an official report that must be written in a formal style. For each of the following, indicate what you would do. Do not consult a grammar reference, but simply answer to the best of your ability based on your own formal writing style. % Number of respondents In the report, you come across the sentence “The rain falls more on him than me.” In this case… You leave this sentence unchanged. There is no need to correct the author’s words. 71.7% 314 For formal style, you change the sentence to “The rain falls more on him than I. 28.3% 124 In the report, you come across the sentence “Everyone other than her left.” In this case… For formal style, you change the sentence to “Everyone other than she left. 59.4% 260 You leave this sentence unchanged. There is no need to correct the author’s words. 40.6% 178 In the report, you come across the sentence “I saw everyone other than her.” In this case… You leave this sentence unchanged. There is no need to correct the author’s words. 78.5% 344 For formal style, you change the sentence to “I saw everyone other than she.” 21.5% 94 In the report, you come across the sentence “He is taller than me.” In this case… You change the sentence to “He is taller than I am.” 53.4% 234 You change the sentence to “He is taller than I.” 33.8% 148 You leave this sentence unchanged. There is no need to correct the author’s words. 12.8% 56 In the report, you come across the sentence “He is taller than us.” In this case… You change the sentence to “He is taller than we are.” 62.3% 273 You leave this sentence unchanged. There is no need to correct the author’s words. 23.3% 102 You change the sentence to “He is taller than we.” 14.4% 63 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 112  D. J. WULF Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 113 continued In the report, you come across the sentence “He is taller than them.” In this case… You change the sentence to “He is taller than they are.” 62.1% 272 You change the sentence to “He is taller than they.” 21.2% 93 You leave this sentence unchanged. There is no need to correct the author’s words. 16.7% 73 Part 3 Suppose that you are reading a document. The style of the text overall is formal. Consider the following questions. % Number of respondents In the text, you read the sentence “I teach her French better than him.” Think about what this sentence meant to you as you read it just now and then read the remainder of this question. She has two French teachers. The writer is a better instructor than the other instructor. 64.8% 284 The writer teaches two people French and is more successful teaching her than teaching him. 35.2% 154 continued In the text, you read the sentence “I like her better than him.” Think about what this sentence meant to you as you read it just now and then read the remainder of this question. I like her better than I like him. 92.9% 407 I like her better than he likes her. 5.9% 26 The intended meaning was neither of the above. 1.1% 5 In the text, you read the sentence “Jim hit more homeruns than me.” Think about what this sentence meant to you as you read it just now and then read the remainder of this question. Jim hit more home runs than the writer of the sentence hit. 96.3% 422 Neither of the above. 2.7% 12 The writer of the sentence hit more Home runs than Jim hit. 0.9% 4 In the text, you read the following sentence: “Al Smith repairs more radiators than us.” Think about what this sentence meant to you as you read it just now and then read the remainder of this question. It is comprehensible, but you note a grammatical error that should be corrected. 74% 324 It is fine. You have no particular reaction to it. 24.7% 108 The writer is communicating a nonsensical idea. 1.4% 6

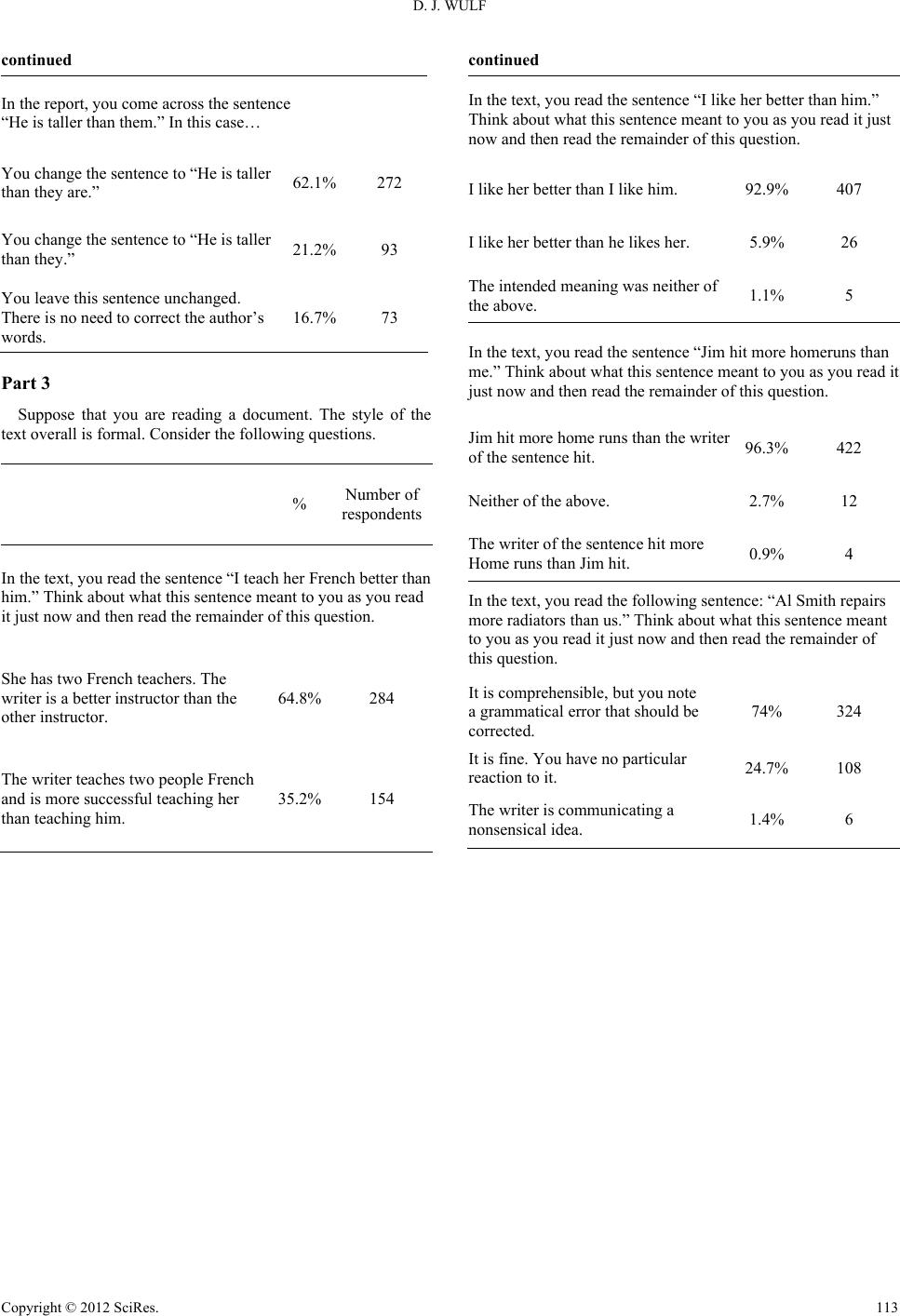

|