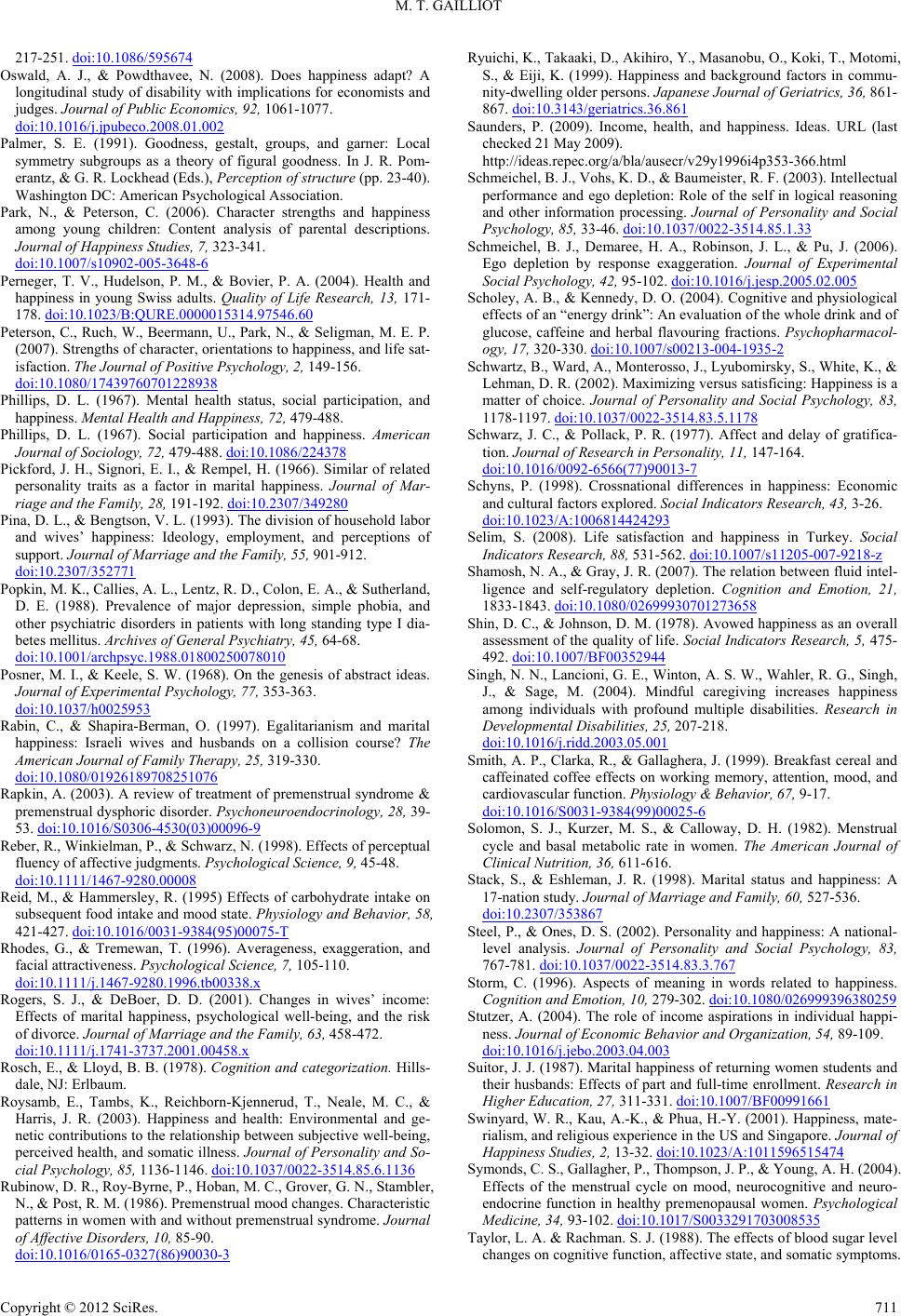

Psychology 2012. Vol.3, No.9, 702-712 Published Online September 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.39107 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 702 Happiness as Surplus or Freely Available Energy Matthew T. Gailliot University of Albany, Albany, USA Email: mgailliot@gmail.com Received March 24th, 2012; revised May 7th, 2012; accepted June 8th, 2012 This paper presents a literature review that indicate happiness as a state of freely available or surplus energy. Happiness is associated with good metabolism and glucose levels, fewer demands (from parenting, work, difficult social relationships, or personal threats), and goal achievement, as well as increased ease of processing, mental resources, social support, and monetary wealth. Each of these either provide or help conserve energy. Keywords: Happiness; Emotion; Energy; Efficiency Introduction A focus on energy could be a powerful psychological perspec- tive. People are organisms made of metabolic energy, and life can be viewed as a process of attaining and managing metabolic energy. Some work indicates that evolution selected on tenden- cies to attain increasingly larger amounts of energy (e.g., sugar, oil) from the environment and to use that energy efficiently (e.g., modern technology, Gilliland, 1978; Lotka, 1922; Odum, 1995). From this view, having and controlling energy should be associated with feeling good—one is fulfilling an evolved ten- dency—whereas lacking energy should feel bad. The current work presents the theory that happiness is a state of having freely available or surplus energy (i.e., when energy availability exceeds demands). Processes that create or sustain this surplus are concomitant with happiness. The paper pro- vides an in-depth review of the relevant literature on happiness and presents an experimental test of one hypothesis derived from the theory—that displays of happiness signal that one has expendable energy. The purpose of the review is to present a novel theory of happiness that advances research on and under- standing of the topic and that synthesizes and links disparate research topics. Energy relevant to happiness can take two forms. One is bio- logical, metabolic energy (e.g., glucose). All cells in the body use metabolic energy. When metabolite supply exceeds demand, there is a surplus. The theory is that people are less happy when metabolic energy is low. The other forms of energy relevant to happiness are second- dary sources of metabolic energy—sources that provide or conserve metabolic energy. These include social relationships (e.g., friends give food to one another and facilitate effortful coping) and technology (e.g., modern transportation conserves mechanical energy used for walking, computers reduce meta- bolic energy needed for memory because they preserve infor- mation). Secondary sources of energy are posited to be associ- ated with happiness because they increase the likelihood of surplus energy. Happiness as Concomitant with Available Energy—A Review of the Happiness Literature Many studies link happiness with available energy. People generally associate happiness more with energy than a lack thereof. Energetic music (e.g., higher pitch tones, faster tempos, ascending scales) has been rated as happier than less energetic music (Collier & Hubbard, 2001a, 2001b). Words indicative of happiness tend to reflect having energy to a greater extent than words less indicative of happiness (Storm, 1996). Happy people tend to be more energetic, excited, and zestful than less happy people (Block & Kremen, 1996; Csikszentmi- halyi & Hunter, 2003; Klohnen, 1996; Park & Peterson, 2006; Peterson, Ruch, Beermann, Park, & Seligman, 2007; Ryan & Frederick, 1997). Happiness is associated with increased acti- vity (Csikszentmihalyi & Hunter, 2003; Veenhoven, 1988). One study found that watching a video that induced joy (v fear or anger) increased the number of activities in which partici- pants wanted to engage (Fredrickson & Branigan, 2004). Men in one study talked more to a female after having seen stimuli that increased positive (v negative) mood (Cunningham, 1988). Another study found that cricket players who were happy (v less happy) displayed more energy, enthusiasm, focus, and confidence (Totterdell, 1999). Increased extraversion, often associated with energetic be- havior, has strong links to happiness (Brebner, Donaldson, Kirby, & Ward, 1995; Cheng & Furnham, 2002; Francis, 1998; Francis, Brown, Lester, & Philipchalk, 1998; Francis & Lester, 1997; Furnham & Cheng, 1999; Hills & Argyle, 2001; Jopp & Rott, 2006; Lu & Shih, 1997), even when making comparisons across nations (Steel & Ones, 2002). Extraversion is associated with increased approach, and likewise happiness has been linked to increased engagement and sociability (Csikszentmi- halyi & Hunter, 2003; Peterson et al., 2007). Depression is strongly and negatively associated with happi- ness (APA, 1994; Joseph & Lewis, 1998; Kammann & Flett, 1983; Matsubayashi et al., 1992; McGreal & Joseph, 1993). A defining feature of depression is low energy or tiredness (McGillivray & McCabe, 2007; Naarding et al., 2007). Even perceptual biases suggest happiness as a state of sur- plus energy. Participants induced into a happy (v sad) mood perceived a hill as less steep (Riener, Stefanucci, Proffitt, & Clore, 2003). The idea is that happy participants had sufficient energy to ascend the hill, and so it appeared less steep. Happiness generally has thus been linked to having available  M. T. GAILLIOT energy, whereas low happiness (or sadness) has been linked to low energy. This pattern is mirrored in work on primary and secondary sources of metabolic energy. Primary Energy Metabolic Energy Metabolic energy is the primary energy through the use of which all thought and action occur. Evidence indicates that happiness is reduced when the metabolic energy of glucose is low or its use is impaired, whereas happiness is higher when adequate amounts of usable glucose are available. Bad or depressed moods are more common when glucose is low (Barglow et al., 1984; Benton & Owens, 1993; Hepburn, Deary, MacLeod, & Frier, 1996; Taylor & Rachman, 1988; Wredling, Theorell, Roll, Lins, & Adamson, 1992; Yaryura- Tobias & Neziroglu, 1975; cf. Reid & Hammersley, 1995; Scholey & Kennedy, 2004) and among people with (v without) diabetes, who process glucose less effectively and are prone to experience hypoglycemia (e.g., Eren, Erdi, & Özcankaya, 2003; Fabrykant & Pacella, 1948; Fris & Nanjundappa, 1986; Gon- der-Frederick, Cox, Bobbitt, & Pennebaker, 1989; Lustman, Griffith, Clouse, & Cryer, 1986; Mueller, Heninger, & Mc- Donal, 1968; Popkin, Callies, Lentz, Colon, & Sutherland, 1988; Van Pragg & Leijnse, 1965; Wells, Golding, & Burnam, 1989; Wilson, 1951). A glucose clamp (v control device), which reduces glucose levels, has been found to worsen mood (Gold, MacLeod, Deary, & Frier, 1995; McCrimmon, Frier, & Deary, 1999), as has skipping breakfast (Smith, Clarka, & Gal- laghera, 1999). Conversely, glucose drinks (v placebos) have been found to improve mood (Benton, Brett, & Brain, 1987; Benton & Owens, 1993). Research on the symptoms of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) provides converging evidence. Metabolic energy use by the ovaries increases during PMS (e.g., Aschoff & Pohl, 1970; Bisdee & James, 1983; Bisdee, James, & Shaw, 1989; Dalton, 1999; Hessemer & Bruck, 1985; Landgren, Unden, & Diczfa- lusy, 1980; Mayo, 1997; Solomon, Kurzer, & Calloway, 1982; Webb, 1981, 1986), thereby reducing the likelihood of energy surplus. A large body of evidence links conclusively PMS to more negative mood (Bailey & Cohen, 1999; Baker, Best, Manfredi, Demers, & Wolf, 1995; Bloch, Schmidt, & Rubinow, 1997; Dalton, 1999; Evans, Haney, Levin, Foltin, & Fischman, 1998; George, 2009; Hartlage & Arduino, 2002; Limosin, Gorwood, & Ades, 2001; Natale & Albertazzi, 2006; Rapkin, 2003; Rubinow et al., 1986; Symonds, Gallagher, Thompson, & Young, 2004; Zhao, Wang, Qu, & Wang 1998). Using self-control has been found to decrease glucose in the bloodstream (Fairclough & Houston, 2004; Gailliot et al., 2007a; Gailliot, 2009a). Using self-control therefore might worsen mood. Individual studies have largely failed to find evidence that using self-control worsens mood, yet a meta- analysis of over 600 participants found a small effect of self- control worsening mood (Gailliot & Vohs, 2009). If metabolic energy improves mood, then people might eat so as to escape negative moods. Indeed, depression increases food cravings (Dye, Warner, & Bancroft, 1995) and eating is a typi- cal response to relieve personal distress (Tice, Baumeister, Shmueli, & Muraven, 2006). Physiological states, aside from glucose, related to metabolic energy distribution might also relate to mood. Pleasant stimuli (e.g., odors, pictures) reduced cortisol (Barak, 2006), which functions partly to increase blood-glucose. Another study de- monstrated that happiness (v anger or anxiety) predicted lower blood pressure (James, Yee, Harshfield, Blank, & Pickering, 1986). Increased blood pressure can be concomitant with in- creased metabolite distribution. Some studies examining energy use in the brain also are con- sistent with a link between happiness and surplus energy. Neu- roscience evidence indicates that sadness can increase brain energy use, whereas happiness can decrease it (Baxter et al., 1989; George et al., 1995). Self-control allows for emotional coping (e.g., regulating moods so as to increase happiness, Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Muraven, & Tice, 1998; Finkel & Campbell, 2001; Gailliot, Schmeichel, & Baumeister, 2006; Gailliot, Schmeichel, & Maner, 2006; Muraven & Slessareva, 2003; Muraven, Tice, & Baumeister, 1998; Schmeichel, Demaree, Robinson, & Pu, 2005; Schmeichel, Vohs, & Baumeister, 2003; Shamosh & Gray, 2006; Vohs, Baumeister, & Ciarocco, 2005) and is in- trinsically tied with glucose metabolism (DeWall, Baumeister, Gailliot, & Maner, 2008; DeWall, Gailliot, Deckman, & Bush- man, 2009; Fairclough & Houston, 2004; Gailliot, 2008, 2009a, 2009b, 2009d, 2009e, in press; Gailliot et al., 2007; Gailliot & Baumeister, 2007; Gailliot, Hildebrandt, Eckel, & Baumeister, 2009; Gailliot, Peruche, Plant, & Baumeister, 2009; Masicampo & Baumeister, 2008). A survey across nations indicated that the ability to cope is a primary determinant of happiness (Haller & Hadler, 2006). Other work further implicates self-control, and hence me- tabolism, as linking happiness to energy. Noise impairs self- control (Muraven & Baumeister, 2000) perhaps via metabolite depletion (Gailliot & Baumeister, 2007). Likewise, noise pollu- tion predicts reduced happiness (Weinhold, 2008). Others have argued that happiness rests crucially on the regulation and con- trol of drives, impulses, and objects (Furnham & Petrides, 2003; Mukherjee & Basu, 2008), which is akin to self-control. The composition of neurotransmitters can be used to test whether happiness is associated with increased energy. The prediction is that neurotransmitters associated with happiness contain more useable energy than do other neurotransmitters. Neurons fire via the use of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) de- rived from breaking carbon-to-carbon bonds. Dopamine is positively associated with happiness (Bressan & Crippa, 2005; Drevets et al., 2001), and it contains more carbon than do other neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine, γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA), or glutamate (Wikipedia, 2012), thus supporting the prediction. Demands on Metabolic Energy That which uses more energy can be considered a demand on metabolic energy, and that which uses more energy also re- duces the likelihood of there being freely available or surplus energy. Numerous studies link increased life demands, there- fore entailing increased energy use (Fairclough & Houston, 2004), to reduced happiness. Happiness will often be associated with low energy and high demands because these are times when a surplus of energy is less likely. Being a parent demands a lot of energy (e.g., obtaining money). It also reduces happiness (Glenn & McLanahan, 1982; Glenn & Weaver, 1978; McLanahan & Adams, 1987; Nicolson, 1999; White, Booth, & Edwards, 1986). Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 703  M. T. GAILLIOT Work often is effortful and entails overriding intrinsic, so as to meet extrinsic, motivations (Gordijn, Hindriks, Koomen, Dijksterhuis, & Van Knippenberg, 2004). When work is less demanding—such as toward the weekend (Csikszentmihalyi & Hunter, 2003; Gallup, 2008; Mihalcea & Liu, 2006) or when more leisure time is afforded (Cameron, 1975; Csikszentmiha- lyi & Hunter, 2003; Easterlin, 2003; Tella & MacCulloch, 2007; Tkach & Lyubomirsky, 2006; Yu et al., 2002)—happiness is greater. The effort of caring for one with a disability likewise predicts reduced happiness (Easterlin, 2003; Eriksson, Tham, & Fugl-Meyer, 2005; Marinic & Brkljacic, 2008). Demanding marriages reduce happiness relative to those that do not (Lu & Shih, 1997; Orden & Bradburn, 1969; Pina & Bengston, 1993; Rabin & Shapira-Berman, 1997; Ward, 1993), as do difficult social relationships relative to easier ones (e.g., such as through the conflict of worldviews, Burleson, 1994; Ortega, Whitt, & Williams, 1988; Pickford, Signori, & Rempel, 1966; Suitor, 1987; Welsch, 2008). Other demands have also been linked to reduced happiness. Physical attractiveness among women, for whom good looks especially save energy in pursuit of attracting and attaining high quality mates, but not men has been found to predict increased happiness (Mathes & Kahn, 1975). Homeless people (v people who have a home) are less happy (Biswas & Diener, 2006). Social projects that reduce living demands likewise increase happiness (Moller & Jackson, 1997). Happiness can be considered the opposite of experiencing personal threat, and threat occurs when demands exceed avail- able resources to cope (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1996; Blas- covich & Mendes, 2000). Happiness therefore should involve having resources or experiencing low demands. Mortality is more threatening when metabolic energy is low (Gailliot, 2009b, in press), and mortality salience might reduce glucose (Gailliot et al., 2007). Greater religiosity has been found to reduce the threat, and therefore costs, of mortality salience (Jonas & Fischer, 2006), and therefore should be associated with an increased likelihood of surplus energy (due to reduced costs coping with mortality). Connecting this possibility to happiness, religion is associated with greater happiness (Cam- eron, 1975; French & Joseph, 1999; Francis & Lester, 1997; Lelkes, 2005; Swinyard, Kau, & Phua, 2001; cf. Lewis, Lani- gan, Joseph, & Fockert, 1997; Lewis, Maltby, & Burkinshaw, 2000). Threat occurring from being bullied or sexually harassed among children predict reduced happiness (Gibbs & Sinclair, 2000), as does greater social anxiety (Neto, 2001). Some theorists have argued that happiness is reduced be- cause life is more demanding due to our living in a world that is radically different from the one in which our ancestors evolved (Buss, 2000; Grinde, 2002). Hence, metabolically expensive (Fairclough & Houston, 2004; Gailliot et al., 2007; Gailliot & Baumeister, 2007) regulation systems are overactive (Nesse, 2004). Goals A goal is a metabolic demand ongoing for some time. A goal thus can be represented as a process of metabolic energy at- tainment and use (e.g., each time a dieter sees a piece of cake, he or she effortfully uses self-control to avoid it, a person with a physical fitness goal regularly expends metabolic energy every workout). When a goal ceases or is relinquished, energy previously committed to the goal becomes freely available, surplus energy. Such dynamics should influence happiness. Indeed, meeting a goal, or goals, can increase happiness (Diener & Lucas, 2000; Haybron, 2008; Kasser & Ryan, 1993). Hence, satisfaction with specific life domains predicts increased happiness (Michalos, 1980). Happiness is strongly influenced by discrepancies between what one has and wants (Michalos, 1983; Tsou & Liu, 2001), perhaps because of the extent to which one is motivated or has formed goals to obtain more. The goal of maximizing (v nonmaximizing)—in which people at- tempt to choose the very best among every option—might also reduce happiness (Schwartz et al., 2002). Mental Resources and Processing Fluency Biological resources—metabolic energy—often has been re- ferred to as “mental resources” in the social sciences, though the construct overlaps with actual metabolic energy (Gailliot et al., 2007; Gailliot & Baumeister, 2007; Gailliot, 2009c). Find- ings on mental resources and ease of processing are consistent with the idea that happiness is concomitant with energy. Happy people appear to have more mental resources than less happy people, such that they are more creative, mindful, and optimistic (Basso et al., 1996; Derryberry & Tucker, 1994; Fredrickson & Branigan, 2004; Isen et al., 1987). They display broader thought and attention and are more open to information (Estrada et al., 1997). Happy (vs unhappy) children have been found to delay gratification longer (Moore, Clyburn, & Under- wood, 1976; Schwarz & Pollack, 1977). Negative moods seem to impair self-control (Leith & Baumeister, 1996; Tice, Brat- slavsky, & Baumeister, 2001). Positive affect has been found to replenish self-control when it is fatigued (Tice et al., 2006). One contradictory finding was that a happiness induction in- creased stereotype use (Bodenhausen, Kramer, & Susser, 1994), suggesting reduced mental resources (Devine, 1989). It could be that happy people have more energy and mental resources, though they might not always willingly expend their energy or resources. Hence, when participants were held accountable for their stereotype use, happiness did not increase stereotype use (Bodenhausen et al., 1994). Stimuli that take less energy to process—such as those that are familiar—should be liked more than stimuli that take more energy to process, consistent with the link between having freely available energy and happiness. In support of this, stim- uli that are easier to process and familiar are liked more than other stimuli, and these stimuli have been found to produce less brain activation (i.e., use less energy) (Bornstein, 1989; Ca- cioppo & Winkielman, 2001; Desimone, Miller, Chelazzi, & Lueschow, 1995; Haber & Hershenson, 1965; Harrison, 1977; Jacoby & Dallas, 1981; Whittlesea, Jacoby, & Girard, 1990; Witherspoon & Allan, 1985; Zajonc, 1968, 2001, 2002). People also like more stimuli that are prototypical or symmetrical (Berlyne, 1974; Halberstadt & Rhodes, 2000; Langlois & Roggman, 1990; Martindale & Moore, 1988; Rhodes & Tre- mewan, 1996) possibly because they are processed faster and more efficiently (Checkosky & Whitlock, 1973; Johnstone, 1994; Palmer, 1991; Posner & Keele, 1968; Rosch & Lloyd, 1978) which should reduce energy use (Mulder, 1986). Antici- pated (v unanticipated) information has been found to be pro- cessed faster and hence easier, and to be more pleasant (Whit- tlesea, 1993). Likewise, factors that facilitate the processing of stimuli have been found to increase liking for the stimuli (Reber, Winkielman, & Schwarz, 1998). Numbers are more easily proc- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 704  M. T. GAILLIOT essed in Chinese than in English, and math tends to be better liked among Chinese than English speakers (Gladwell, 2009). Secondary Energy Factors that provide energy or reduce its use (sources of se- condary energy) also suggest a connection between happiness and having energy. Two examples are social support and mone- tary wealth. Social Support Social support can provide energy or reduce its use in several ways. People give one another food. They also save energy in many ways for one another, such as by helping one another, assisting in coping with stress, or providing resources while requiring relatively little work (e.g., parents giving clothing to their children). Ample evidence demonstrates that people are happier with better social support or more social involvement (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Booth, 1992; Brim, 1974; Chan & Lee, 2006; Gundelach & Kreinar, 2004; Jopp & Rott, 2006; Kehle & Bray, 2003; Lane, 1994, 2000; Lu, 1999; Lu, Shih, Lin, & Ju, 1997; Natvig, Albrektsen, & Qvarnstrom, 2003; Neto, 2001; North, Holahan, Moos, & Cronkite, 2008; Perneger, Hudelson, & Bovier, 2004; Phillips, 1967; Ryuichi et al., 1999; Singh et al., 2004; Uchida, Norasakkunkit, & Kitayama, 2004). Happiness is positively associated with self-esteem (Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, & Vohs, 2003), and self-esteem reflects belongingness (Leary & Baumeister, 2000). People report seeking social con- tact so as to increase their happiness (Tkach & Lyubomirsky, 2006). Married people tend to be happier than unmarried people (Cid, Ferres, & Rossi, 2008; Mookherjee, 1998; Stack & Esh- leman, 1998). Religious institutions can serve as a source of social support, and religious involvement predicts increased happiness (Cameron, 1975; Francis & Lester, 1997; French & Joseph, 1999; Lelkes, 2005; Swinyard, Kau, & Phua, 2001; cf. Lewis, Lanigan, Joseph, & Fockert, 1997; Lewis, Maltby, & Burkinshaw, 2000). Likewise, the end of social relationships and death greatly reduce happiness (Ballas & Dorling, 2007; Oswald & Powdthavee, 2008). Monetary Wealth Money is another source of secondary energy. Money can be used to acquire metabolic energy (e.g., buy food) and it can also save energy (e.g., paying for a taxi rather than walking, hiring an accountant to do one’s taxes, using air conditioning rather than sweating in the heat). People with money can have a more leisurely, effortless life than can those without. Money there- fore should be associated with a greater likelihood of having available energy. Ample research demonstrates a positive correlation between wealth and happiness. Across both nations and individuals, wealth predicts happiness (Biswas-Diener & Diener, 2006; Cid, Ferres, & Rossi, 2008; Diener, Horwitz, & Emmons, 1985; Easterlin, 1995, 2001; Gardner & Oswald, 2001; Gerdtham & Johannesson, 2002; Hagerty & Veenhoven, 2003; Johnson & Krueger, 2006; Mookherjee, 1998; Namazie & Sanfey, 1998; North, Holahan, Moos, & Cronkite, 2008; Rogers & DeBoer, 2001; Saunders, 2009; Schyns, 1998; Stack & Eshleman, 1998; Steel & Ones, 2002; Tella & MacCulloch, 2007; Tella, Mac- Culloch, & Oswald, 2003; Tella, New, & MacCulloch, 2007; Shin & Johnson, 1978; Veenhoven, 1991, 1995; World Bank, 1997; cf. Easterlin, 2005). Likewise, unemployment might lead to unhappiness (Booth & Ours, 2007; Di Tella, MacCulloch, & Oswald, 2001; Frey & Stutzer, 2000; Graham & Pettinato, 2001). When people aspire for more than they have, however, money might not lead to happiness (Hagerty, 2000; Stutzer, 2004; Tsou & Liu, 2001). This is consistent with the idea that happiness is reduced with increased demands or goals—in this case, to acquire more wealth. An Experimental Test—Displays of Happiness as Energetically Inefficient If happiness is concomitant with having available or surplus energy, then its expression may signal that one has expendable energy. Expressions of happiness may entail reduced effi- ciency. Past work has found that depressed individuals conserve en- ergy in their movements—they move relatively little (Fisch, Frey, & Hirsbrunner, 1983; Griesinger, 1876; Kraepelin, 1913). Upon recovering from depression, people move more, more complexly, and more rapidly. This suggests that happiness might be negatively associated with the conservation of me- chanical energy. An experimental study showed that more participants who received a positive comment (e.g., “I like your shirt.”) from an experimenter lifted their feet less efficiently while walking upstairs than did participants who received a neutral comment (i.e., “This is Hall C.”), χ2 = 2.78, p < .05 (one-tailed; see Fig- ure 1). General Discussion A review of the literature on happiness and an experimental test provided general support for the idea that happiness is a state in which one has freely available or surplus energy. This pattern emerged from work on a variety of topics, including metabolism, demands (parenting, work, difficult social relation- ships, personal threat), goals, ease of processing and liking, 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 Efficient Step Height Inefficient Step Height Positive Neutral Comment Figure 1. Number of people who exhibited either efficient or inefficient step height as a function of having received either a compliment or neutral statement. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 705  M. T. GAILLIOT mental resources, social support, and monetary wealth. The theory brings together work across several different disciplines, including neuroscience, endocrinology, social psychology, eco- nomics, sociology, and biology. The theory of happiness and energy should help explain find- ings on happiness other than those reviewed. Happiness has been found to predict future success (e.g., in marriage, friend- ship, wealth, work, and health, Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005). To the extent that happiness represents having energy, then being capable of energy-demanding activities (e.g., re- solving difficulties with a spouse) should lead to lead to future success. One seemingly inconsistent finding may be that hyperglyce- mia (i.e., when blood-glucose levels are especially high) is not associated with happiness, though there is ample energy in the bloodstream. Hyperglycemia might not be linked to happiness because it may reduce the flow of glucose to the brain. One might conclude that people should rarely expend energy (e.g., sit on the couch all day) because they generally seek hap- piness. Though this can occur (e.g., passivity is increasingly common in modern society), people clearly expend their energy on a regular basis. Conservation might be reduced because one must use energy to obtain energy (e.g., work 40 hours each week to ensure an adequate food supply) and because people have goals less clearly related to energy (e.g., reproductive goals). Happiness is having surplus energy in the context of other meanings and values in life. One strength of the proposed theory is that it suggests many novel hypotheses. All else being equal, events that provide energy will tend to produce greater happiness than will events that provide less energy or take away energy. People are hap- pier if there exists the potential to use taxi rides rather than to always walk. The inefficient acts in which happy people engage (e.g., play behavior) might be more likely to be perceived as pointless or wasteful to others. Happy people expend energy more liberally, and so others might not perceive the value of these behaviors. The relationship between happiness and energy could be cyclical. Having energy allows one to more easily ensure future happiness. For example, a happy person at work might cheer up another coworker by giving flowers, increasing the likelihood that the coworker will reward the person in the future. Approaches to increasing happiness should include those that free up metabolic resources or provide resources, such as those that alleviate demands. Chronically unhappy in- dividuals might have tendencies to overcommit themselves and rarely experience energy surplus. In demanding situations, people might expect happy people to be less happy and to use their energy to help. Displays of happiness should be perceived negatively when energy is wasted. Factors should influence happiness partly to the extent that they create metabolic demands. For example, an argument that brings to mind new challenges should decrease happiness, whereas an argument that ends a demanding and draining rela- tionship should reduce happiness to a lesser extent or even in- crease happiness. Diabetes and problems with glucose are linked to being less happy (see above). Other metabolic disor- ders might therefore be related to happiness. Factors that might increase the use of glucose include high processing loads, no- velty, time pressure, and multitasking (Mulder, 1986). These same factors might reduce happiness. Happiness might arise from having too much information to process, being over- whelmed with novelty or experiencing too much change, lack- ing sufficient time to complete goals, or trying to do too much. Happiness should be higher across the lifespan during times when people have more energy. Some studies have found that younger people tend to be happier than older people (Chang, 2007; Easterlin, 2006; Gerdtham & Johannesson, 2002; Hola- han, Holahan, Velasquez, & North, 2008; Selim, 2008; cf. Fugl-Meyer, Branholm, & Fugl-Meyer, 1991), and they also tend to have more (primary) energy. Whether energy is avail- able for use might be key in determining happiness. Fat people have more stored energy than thin people, yet they might not be happier partly because good physical fitness enhances the dis- tribution of metabolites throughout the body. Happiness might increase from terminating goals and not only from achieving them. Abandoning a failed goal, for in- stance, might eventually increase happiness because one is able to use energy that otherwise would have been used toward goal pursuit. Energy is concomitant with happiness. Happy people may signal their happiness by being less energetically efficient or expending more energy than needed. The happy person sings in the shower. Typical smiles may use more energy than typical frowns. And, as demonstrated—happiness puts an inefficient “pep in one’s step”. REFERENCES Alesina, A., Tella, R. D., & MacCulloch, R. (2003). Inequality and happiness: Are Europeans and Americans different? Journal of Pub- lic Economics, 88, 2009-2042. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2003.07.006 APA (American Psychiatric Association) (1994). Diagnostic and statis- tical manual of mental disorders. 4th Edition, Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 715-718. Aschoff, J., & Pohl, H. (1970). Rhythmic variations in energy metabo- lism. Federation Proceedings, 29, 1541-1542. Bailey, J. W., & Cohen, L. S. (1999). Prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in women who seek treatment for premenstrual syndrome. Journal of Women’s Health and Gender-Based Medicine, 8, 1181- 1184. doi:10.1089/jwh.1.1999.8.1181 Baker, E. R., Best, R. G., Manfredi, R. L., Demers, L. M., & Wolf, G. C. (1995). Efficacy of progesterone vaginal suppositories in allevia- tion of nervous symptoms in patients with premenstrual syndrome. Journal of Assisted Re pr od uc t io n a nd Genetics, 12, 205-209. doi:10.1007/BF02211800 Ballas, D., & Dorling, D. (2007). Measuring the impact of major life events upon happiness. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36, 1244-1252. doi:10.1093/ije/dym182 Barak, Y. (2006). The immune system and happiness. Autoimmunity Reviews, 5, 523-527. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2006.02.010 Barglow, P., Hatcher, R., Edidin, D. V., & Sloan-Rossiter, D. (1984). Stress and metabolic control in diabetes: Psychosomatic evidence and evaluation of methods. Psychosomatic Medicine , 46, 127-144. Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Per- sonality and Social P sychology, 74, 1252-1265. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1252 Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 1 1 7, 497-529. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497 Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal suc- cess, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4, 1-44. doi:10.1111/1529-1006.01431 Benton, D., & Owens, D. (1993). Is raised blood glucose associated with the relief of tension? Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 37, 1-13. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(93)90101-K Benton, D., Brett, V., & Brain, P. F. (1987). Glucose improves attention Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 706  M. T. GAILLIOT and reaction to frustration in children. Biological Psychology, 24, 95-100. doi:10.1016/0301-0511(87)90016-0 Berlyne, D. E. (1974). Studies in the new experimental aesthetics: Steps toward an objective psychology of aesthetic appreciation. Washing- ton DC: Hemisphere. Bisdee, J. T., James, W. P., & Shaw, M. A. (1989). Changes in energy expenditure during the menstrual cycle. The Britsh Journal of Nutri- tion, 61, 187-199. doi:10.1079/BJN19890108 Bisdee, J. T., & James, W. P. T. (1983). Whole body calorimetry stud- ies in the menstrual cycle. New York: Fourth International Confer- ence on Obesity. Biswas-Diener, R., & Diener, E. (2006). The subjective well-being of the homeless, and lessons for happiness. Social Indicators Research, 76, 185-205. doi:10.1007/s11205-005-8671-9 Bloch, M., Schmidt, P. J., & Rubinow, D. R. (1997). Premenstrual syndrome: Evidence for symptom stability across cycles. American Journal of Psychiatry, 1 5 4 , 1741-1746. Bodenhausen, G. V., Kramer, G. P., & Susser, K. (1994). Happiness and stereotypic thinking in social judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 621-632. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.66.4.621 Booth, A. L., & Ours, J. C. V. (2007). Job satisfaction and family hap- piness: The part-time work puzzle. URL (last checked 21 May 2009). http://ssrn.com/abstract=1138584 Booth, R. (1992). An examination of the relationship between happi- ness, loneliness, and shyness in college students. Journal of College Student Development, 33, 157-162. Bornstein, R. F. (1989). Exposure and affect: Overview and meta- analysis of research, 1968-1987. Psychological Bulletin, 106, 265- 289. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.106.2.265 Brebner, J., Donaldson, J., Kirby, N., & Ward, L. (1995). Relationships between happiness and personality. Personality and Individual Dif- ferences, 19, 251-258. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(95)00022-X Bressan, R. A., & Crippa, J. A. (2005). The role of dopamine in reward and pleasure behaviour—Review of data from preclinical research. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavic, 111, 14-21. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00540.x Brickman, P., & Campbell, D. T. (1971). Hedonic relativism and plan- ning the good society. In M. H. Appley (Ed.), Adaptation-level the- ory (pp. 287-305). New York: Academic Press. Brim, J. A. (1974). Social network correlates of avowed happiness. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 158, 432-439. doi:10.1097/00005053-197406000-00006 Burleson, B. R. (1994). Thoughts about talk in romantic relationships: Similarity makes for attraction (and happiness, too). Communication Quarterly, 42, 259-273. doi:10.1080/01463379409369933 Buss, D. M. (2000). The evolution of happiness. American Psychologist, 55, 15-23. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.15 Cacioppo, J. T., & Winkielman, P. (2001). Mind at ease puts a smile on the face: Psychophysiological evidence that processing facilitation elicits positive affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 989-1000. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.6.989 Cameron, P. (1975). Mood as an indicant of happiness: Age, sex, social class, and situational differences. Journal of Gerontology, 30, 216- 224. Chan, Y. K., & Lee, R. P. L. (2006). Network size, social support and happiness in later life: A comparative study of Beijing and Hong Kong. Journal of Happiness S tudies, 7, 87-112. doi:10.1007/s10902-005-1915-1 Chang, P. C. (2007). Demographic factors affecting happiness and the relations between happiness, job satisfaction, organizational com- mitment, and turnover intention. Thesis, Human Resource Manage- ment. Checkosky, S. F., & Whitlock, D. (1973). The effects of pattern good- ness on recognition time in a memory search task. Journal of Ex- perimental Psychology, 100, 341-348. doi:10.1037/h0035692 Cheng, H., & Furnham, A. (2002). Personality, self-esteem, and demo- graphic predictions of happiness and depression. Personality and In- dividual Differences, 34, 921-942. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00078-8 Cid, A., Ferres, D., & Rossi, M. (2008). Testing happiness hypotheses among the elderly. Economy Not eboo ks, 27, 23-45. Collier, W. G., & Hubbard, T. L. (2001a). Judgments of happiness, brightness, speed and tempo change of auditory stimuli varying in pitch and tempo. Psychomusic olo gy, 17, 36-55. doi:10.1037/h0094060 Collier, W. G., & Hubbard, T. L. (2001b). Musical scales and evalua- tions of happiness and awkwardness: Effects of pitch, direction, and scale mode. American Journal of Psycho logy, 114, 355-375. doi:10.2307/1423686 Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Hunter, J. (2003). Happiness in everyday life: The uses of experience sampling. Journal of Happiness Studies, 4, 185-199. doi:10.1023/A:1024409732742 Cunningham, M. R. (1988). Does happiness mean friendliness? Per- sonality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 14, 283-297. doi:10.1177/0146167288142007 Dalton, K. (1999). Preliminary communication-does hormonal contra- ception increase the risk of postnatal psychosis? The British Journal of Family Planning, 24, 172. Desimone, R., Miller, E. K., Chelazzi, L. & Lueschow, A. (1995). Multiple memory systems in the visual cortex. In M. S. Gazzaniga (Ed.), The cognitive neurosciences (pp. 475-490). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Devine, P. G. (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychol- ogy, 56, 5-18. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.56.1.5 DeWall, C. N., Baumeister, R. F., Gailliot, M. T., & Maner, J. K. (2008). Depletion makes the heart grow less helpful: Helping as a function of self-regulatory energy and genetic relatedness. Personal- ity and Social Psychology Bullet in , 34, 1653-1662. doi:10.1177/0146167208323981 DeWall, C. N., Deckman, T., Gailliot, M. T., & Bushman, B. J. (2009). Sweetened blood cools hot tempers: Physiological self-control and aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 37, 1, 73-80. doi:10.1002/ab.20366 Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R. J., & Oswald, A. J. (2001). Preferences over inflation and unemployment: Evidence from surveys of happi- ness. The American Economic Review, 91, 335-341. doi:10.1257/aer.91.1.335 Diener, E., Horwitz, J., & Emmons, R. A. (1985). Happiness of the very wealthy. Social Indicators Research, 16, 263-274. doi:10.1007/BF00415126 Diener, E., Sandvik, E., & Pavot, W. (1991). Happiness is the fre- quency, not the intensity of positive versus negative affect. In F. Strack, M. Argyle, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Subjective well-being: An interdisciplinary perspective. Oxford: Pergamon Press. Drevets, W. C., Gautier, C., Price, J. C., Kupfer, D. J., Kinahan, P. E., Grace, A. A. et al. (2001). Amphetamine-induced dopamine release in human ventral striatum correlates with euphoria. Biological Psy- chiatry, 49, 81-96. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(00)01038-6 Dye, L., Warner, P., & Bancroft, J. (1995). Food craving during the menstrual cycle and its relationship to stress, happiness of relation- ship and depression: A preliminary group. Journal of Affective Dis- orders, 34, 157-164. doi:10.1016/0165-0327(95)00013-D Easterlin, R. A. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 27, 35-47. doi:10.1016/0167-2681(95)00003-B Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Income and happiness: Towards a unified the- ory. The Economic Journal, 11 1, 465-484. doi:10.1111/1468-0297.00646 Easterlin, R. A. (2003). Explaining happiness. Proceedings of the Na- tional Academy of Sciences, 1 0 0 , 11176-11183. doi:10.1073/pnas.1633144100 Easterlin, R. A. (2003). Happiness of women and men in later life: Nature, determinants, and prospects. In M. J. Sirgy (Ed.), Advances in Quality-of-Life Theory and Research (pp. 13-25). The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic. Easterlin, R. A. (2005). Feeding the illusion of growth and happiness: A reply to Hagerty and Veenhoven. Social Indicators Research, 74, 429-443. doi:10.1007/s11205-004-6170-z Easterlin, R. A. (2006). Life cycle happiness and its sources: Intersec- tions of psychology, economics, and demography. Journal of Eco- nomic Psychology, 27, 463-482. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2006.05.002 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 707  M. T. GAILLIOT Eren, I., Erdi, Ö., & Özcankaya, R. (2003). Relationship between blood glucose control and psychiatric disorders in type II diabetic patients. Turk Psikiyatri Dergisi, 14, 184-191. Eriksson, O. T. G., Tham, K., & Fugl-Meyer, A. R. (2005). Couple’s happiness and its relationship to functioning in everyday life after brain injury. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 12, 40- 48. doi:10.1080/11038120510027630 Evans, S. M., Haney, M., Levin, F. R., Folton, R. W., & Fischman, M. W. (1998). Mood and performance changes in women with premen- strual dysphoric disorder: Acute effects of alprazolam. Neuropsy- chopharmacology, 19, 499-516. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00064-5 Fabrykant, M., & Pacella, B. (1948). Labile diabetes: Electroencepha- lographic status and effect of anticonvulsive therapy. Annals of In- ternal Medicine, 29, 860-877. Fairclough, S. H., & Houston, K. (2004). A metabolic measure of men- tal effort. Biologica l Psychology, 66, 177-190. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2003.10.001 Finkel, E. J., & Campbell, W. K. (2001). Self-control and accommoda- tion in close relationships: An interdependence analysis. Journal of Personality and Social P s y chology, 81, 263-277. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.2.263 Fisch, H. U., Frey, S., & Hirsbrunner, H. P. (1983). Analyzing nonver- bal behavior in depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 92, 307-318. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.92.3.307 Francis, L. J. (1998). Happiness is a thing called stable extraversion: A further examination of the relationship between the Oxford Happi- ness Inventory and Eysencks dimensional model of personality and gender. Personality and Individual Dif ferences, 26, 5-11. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00185-8 Francis, L. J., & Lester, D. (1997). Religion, personality and happiness. Journal of Contemporary Religion, 12, 81-86. doi:10.1080/13537909708580791 Francis, L. J., Brown, L. B., Lester, D., & Philipchalk, R. (1998). Hap- piness as stable extraversion: A cross-cultural examination of the re- liability and validity of the Oxford Happiness Inventory among stu- dents in the UK, USA, Australia, and Canada. Personality and Indi- vidual Differences, 24, 167-171. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00170-0 French, S., & Joseph, S. (1999). Religiosity and its association with happiness, purpose in life, and self-actualisation. Mental Health, Re- ligion, and Culture, 2, 117-120. doi:10.1080/13674679908406340 Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2000). Happiness prospers in democracy. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1, 79-102. doi:10.1023/A:1010028211269 Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2000). Happiness, economy and institutions. The Economic Journal, 110, 918-938. doi:10.1111/1468-0297.00570 Fris, R., & Nanjundappa, G. (1986). Diabetes, depression, and em- ployment status. Social Science and Medicine, 23, 471-475. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(86)90006-7 Fugl-Meyer, A. R., Branholm, I.-B., & Fugl-Meyer, K. (1991). Happi- ness and domain-specific life satisfaction in adult northern Swedes. Clinical Rehabilitation, 5, 25-33. doi:10.1177/026921559100500105 Furnham, A., & Cheng, H. (1999). Personality as predictor of mental health and happiness in the east and west. Personality and Individual Differences, 27, 395-403. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00250-5 Furnham, A., & Petrides, K. V. (2003). Trait emotional intelligence and happiness. Social Be h a v i o ur and Personality, 31, 815-824. doi:10.2224/sbp.2003.31.8.815 Gailliot, M. T. (2008). Unlocking the energy dynamics of executive functioning: Linking executive functioning to brain glycogen. Per- spectives on Psychological Science, 3, 245-263. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00077.x Gailliot, M. T. (2009a). Effortful outgroup interactions impair self- control via the depletion of glucose: The control of stereotypical thought and prejudice as metabolically expensive. Submitted. Gailliot, M. T. (2009a). The effects of glucose drinks on self-control are not due to the taste of the drink: Glucose drinks replenish self-control. Manuscript under Review. Gailliot, M. T. (2009b). Hunger impairs and food improves self-control in the laboratory and across the world: Reducing world hunger as a self-control panacea. Submitted. Gailliot, M. T. (2009c). An increased correspondence bias with low blood-glucose: Low glucose increases heuristic thought. Manuscript under Review. Gailliot, M. T. (2009d). Improved self-control associated with using relatively large amounts of glucose: Learning self-control is metab- olically expensive. Submitted. Gailliot, M. T. (2009e). Alcohol consumption reduces effortful fatigue after sleep: Testing a theory of metabolite depletion and subsequent supercompensation. Submitted. Gailliot, M. T. (in Press). Mortality salience and metabolism: Glucose drinks reduce worldview defense caused by mortality salience. Psy- cology. Gailliot, M. T., & Baumeister, R. F. (2007). The physiology of will- power: Linking blood glucose to self-control. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11, 303-327. doi:10.1177/1088868307303030 Gailliot, M. T. (2009). Using self-control makes people feel things more. In Preparation. Gailliot, M. T., Baumeister, R. F., DeWall, C. N., Maner, J. K., Plant, E. A., Tice, D. M., Brewer, L. E., & Schmeichel, B. J. (2007). Self- control relies on glucose as a limited energy source: Willpower is more than a metaphor. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 325-336. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.325 Gailliot, M. T., Hildebrandt, B., Eckel, L. A., & Baumeister, R. F. (2010). A theory of limited metabolic energy and premenstrual syndrome (PMS) symptoms—Increased metabolic demands during the luteal phase divert metabolic resources from and impair self- control. Review of General Psychology, 14, 269-282. doi:10.1037/a0018525 Gailliot, M. T., Peruche, B. M., Plant., E. A., & Baumeister, R. F. (2009). Stereotypes and prejudice in the blood: Sucrose drinks re- duce prejudice and stereotyping. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 288-290. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2008.09.003 Gailliot, M. T., Schmeichel, B. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (2006). Self- regulatory processes defend against the threat of death: Effects of self-control depletion and trait self-control on thoughts and fears of dying. Journal o f Personality and Soc i a l Psychology, 91, 49-62. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.91.1.49 Gailliot, M. T., Schmeichel, B. J., & Maner, J. K. (2007). Differentiat- ing the effects of self-control and self-esteem on reactions to mortal- ity salience. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43, 894-901. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2006.10.011 Gallup (2008). Gallup poll. http://media.gallup.com/poll/graphs/080605Happiness-Stress2_FGF_ ra.gif Gardner, J., & Oswald, A. (2001). Does money buy happiness? A lon- gitudinal study using data on windfalls. Royal Economic Society. URL (last checked 13 May 2009). http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/research/workingpap ers/publications/2006/twerp_754.pdf George, B. J. (2009). A review of treatment approaches to pre-men- strual syndrome—What do British women perceive to be effective for their symptoms? URL (last checked 7 May 2009). http://www.lifemedicineclinic.com/downloads/premenstrual.pdf George, M. S., Ketter, T. A., Parekh, P. I., Horwitz, B., Herscovitch, P., & Post, R. M. (1995). Brain activity diring transient sadness and happiness in healthy women. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 341-351. Gerdtham, U. G., & Johannesson, M. (2002). The relationship between happiness, health, and socio-economic factors: Results based on Swedish microdata. Journal of Socio- Economics, 30, 553-557. doi:10.1016/S1053-5357(01)00118-4 Gibbs, I., & Sinclair, I. (2000). Bullying, sexual harassment and happi- ness in residential children’s homes. Child Abuse Review, 9, 247-256. doi:10.1002/1099-0852(200007/08)9:4<247::AID-CAR619>3.3.CO; 2-H Gilliland, M. W. (1978). Energy analysis: A new public policy tool. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Gladwell, M. (2009). Outliers. New York: Little, Brown, and Com- pany. Glenn, N. D., & McLanahan, S. (1982). Children and marital happiness: Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 708  M. T. GAILLIOT A further specification of the relationship. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 44, 387-398. doi:10.2307/351263 Glenn, N. D., & Weaver, C. N. (1978). A multivariate, multisurvey study of marital happiness. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 40, 269-282. doi:10.2307/350758 Gold, A. E., MacLeod, K. M., Deary, I. J., & Frier, B. M. (1995). Hy- poglycemia-induced cognitive dysfunction in diabetes mellitus: Ef- fect of hypoglycemia unawareness. Physiology and Behavior, 58, 501-511. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(95)00085-W Gonder-Frederick, L. A., Cox, D. J., Bobbitt, S. A., & Pennebaker, J. W. (1989). Mood changes associated with blood glucose fluctuations in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Health Psychology, 8, 45-49. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.8.1.45 Gordijn, E. H., Hindriks, I., Koomen, W., Dijksterhuis, A., & Van Knippenberg, A. (2004). Consequences of stereotype suppression and internal suppression motivation: A self-regulation approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 212-224. doi:10.1177/0146167203259935 Graham, C., & Pettinato, S. (2001). Happiness, markets, and democracy: Latin America in comparative perspective. Journal of Happiness Studies, 2, 237-268. doi:10.1023/A:1011860027447 Griesinger, W. (1876). Die pathologie und therapie der psychischen krankheiten. Braunschweig: Wreden. Grinde, B. (2002). Happiness in the perspective of evolutionary psy- chology. Journal of Happiness Studi es, 3, 331-354. doi:10.1023/A:1021894227295 Gundelach, P., & Kreinar, S. (2004). Happiness and life satisfaction in advanced European countries. Cross-Cultural Research, 38, 359-386. doi:10.1177/1069397104267483 Haber, R. N., & Hershenson, M. (1965). The effects of repeated brief exposures on growth of a percept. Journal of Experimental Psychol- ogy, 69, 40-46. doi:10.1037/h0021572 Hagerty, M. R. (2000). Social comparisons of income in one’s commu- nity: Evidence from national surveys of income and happiness. Jour- nal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 764-771. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.764 Hagerty, M. R., & Veenhoven, R. (2003). Wealth and happiness revis- ited—Growing national income does go with greater happiness. So- cial Indicators Research, 64, 1-27. doi:10.1023/A:1024790530822 Halberstadt, J., & Rhodes, G. (2000). The attractiveness of nonface averages: Implications for an evolutionary explanation of the attrac- tiveness of average faces. Psychological Scien ce, 4, 285-289. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00257 Haller, M., & Hadler, M. (2006). How social relations and structures can produce happiness and unhappiness: An international compara- tive analysis. Social Indicators Research, 75, 169-216. doi:10.1007/s11205-004-6297-y Hamer, D. H. (1996). The heritability of happiness. Nature Genetics, 14, 125-126. doi:10.1038/ng1096-125 Harrison, A. A. (1977). Mere exposure. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advan- ces in experimental social psychology (pp. 39-83). New York: Aca- demic Press. Hartlage, S. A., & Arduino, K. E. (2002). Toward the content validity of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Do anger and irritability more than depressed mood represent treatment-seekers’ experiences? Psy- chological Reports, 90, 189-202. doi:10.2466/pr0.2002.90.1.189 Hartog, J., & Oosterbeek, H. (1998). Health, wealth and happiness: Why pursue a higher education? Economics of Education Review, 17, 245-256. doi:10.1016/S0272-7757(97)00064-2 Haybron, D. M. (2008). Happiness, the self and human flourishing. Utilitas, 20, 21-49. doi:10.1017/S0953820807002889 Hepburn, D. A., Deary, I. J., MacLeod, K. M., & Frier, B. M. (1996). Adrenaline and psychometric mood factors: A controlled case study of two patients with bilateral adrenalectomy. Personality and Indi- vidual Differences, 20, 451-455. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(95)00191-3 Hessemer, V., & Bruck, K. (1985). Influence of menstrual cycle on thermoregulatory, metabolic, and heart rate responses to exercise at night. Journal of Applied Physiology, 59, 1911-1917 Hills, P., & Argyle, M. (2001). Happiness, introversion-extraversion and happy introverts. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 595-608. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00058-1 Holahan, C. K., Holahan, C. J., Velasquez, K. E., & North, R. J. (2008). Longitudinal change in happiness during aging: The predictive role of positive expectancies. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 66, 229-241. doi:10.2190/AG.66.3.d Jacoby, L. L., & Dallas, M. (1981). On the relationship between auto- biographical memory and perceptual learning. Journal of Experi- mental Psychology: General , 110, 306-340. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.110.3.306 James, G. D., Yee, L. S., Harshfield, G. A., Blank, S. G., & Pickering, T. G. (1986). The influence of happiness, anger, and anxiety on the blood pressure of borderline hypertensives. Psychosomatic Medicine, 48, 502-508. Johnson, W., & Krueger, R. F. (2006). How money buys happiness: Genetic and environmental processes linking finances and life satis- faction. Journal of Personality and Social P s y c h o l o g y, 90, 680-691. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.4.680 Johnstone, R. A. (1994). Female preference for symmetrical males as a by-product of selection for mate recognition. Nature, 372, 172-175. doi:10.1038/372172a0 Jonas, E., & Fischer, P. (2006). Terror management and religion: Evi- dence that intrinsic religiousness mitigates worldview defense fol- lowing mortality salience. Journal of Personality and Social Psy- chology, 91, 553-567. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.91.3.553 Jopp, D., & Rott, C. (2006). Adaptation in very old age: Exploring the role of resources, beliefs, and attitudes for centenarians’ happiness. Psychology and Aging, 21, 266-280. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.21.2.266 Joseph, S., & Lewis, C. A. (1998). The depression-happiness scale: Reliability and validity of a bipolar self-report scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 5 4, 537-544. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199806)54:4<537::AID-JCLP15>3.0. CO;2-G Kammann, R., & Flett, R. (1983). Affectometer 2: A scale to measure current level of general happiness. Australian Journal of Psychology, 35, 259-265. doi:10.1080/00049538308255070 Kehle, T. J., & Bray, M. A. (2003). RICH theory: The promotion of happiness. Psychology in the Scho ol s, 41, 43-49. doi:10.1002/pits.10137 Kraepelin, E. (1913). Psychiatrie—Ein lehrbuch fur studierende und aerzte. Leipzig: Barth. Landgren, B. M., Unden, A. L., & Diczfalusy, E. (1980). Hormonal profile of the cycle in 68 normally menstruating women. Acta Endo- crinologia, 94, 89-98. Lane, R. E. (1994). The road not taken: Friendship, consumerism, and happiness. Critical Review, 8, 521-554. doi:10.1080/08913819408443359 Lane, R. E. (2000). Diminishing returns to income, companionship and happiness. Journal of Ha ppi nes s S tudies, 1, 103-119. doi:10.1023/A:1010080228107 Langlois, J. H., & Roggman, L. A. (1990). Attractive faces are only average. Psychological Science, 1, 115-121. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1990.tb00079.x Leary, M. R., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). The nature and function of self-esteem: Sociometer theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 32, 1-62. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(00)80003-9 Leith, K. P., & Baumeister, R. F. (1996). Why do bad moods increase self-defeating behavior? Emotion, risk taking, and self-regulation. Journal of Personality a nd Social Psychology, 71, 1250-1267. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.71.6.1250 Lelkes, O. (2005). Tasting freedom: Happiness, religion and economic transition. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 59, 173- 194. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2004.03.016 Lewis, C. A., Lanigan, C., Joseph, S., & Fockert, J. D. (1997). Religi- osity and happiness: No evidence for an association among under- graduates. Person ality and Individual Differences, 22, 119-121. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(97)88910-6 Lewis, C. A., Maltby, J., & Burkinshaw, S. (2000). Religion and hap- piness: Still no association. Journal of Beliefs and Values, 21, 233- 236. doi:10.1080/713675504 Limosin, F., Gorwood, P., & Ades, J. (2001). Clinical characteristics of familial versus sporadic alcoholism in a sample of male and female Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 709  M. T. GAILLIOT patients. European Psychiatry, 16, 151-156. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(01)00556-9 Lotka, A. J. (1922). Contribution to the energetics of evolution. Pro- ceedings of the National Academy of Science, 8, 147-151. doi:10.1073/pnas.8.6.147 Lu, L. (1999). Personal or environmental causes of happiness: A longi- tudinal analysis. The Journal of Social Psychology, 139, 79-90. doi:10.1080/00224549909598363 Lu, L., & Shih, J. B. (1997). Personality and happiness: Is mental health a mediator? Personality and Individual Differences, 22, 249-256. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00187-0 Lu, L., & Shih, J. B. (1997). Sources of happiness: A qualitative ap- proach. The Journal of Social Psychology, 137, 181-187. doi:10.1080/00224549709595429 Lu, L., Shih, J. B., Lin, Y. Y., & Ju. L. S. (1997). Personal and envi- ronmental correlates of happiness. Personality and Individual Dif- ferences, 23, 453-462. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(97)80011-6 Lucas, R. E., Clark, A. E., Georgellis, Y., & Diener, E. (2003). Reex- amining adaptation and the set point model of happiness: Reactions to changes in marital status. Journal of Personality and Social Psy- chology, 84, 527-539. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.527 Lustman, P. J., Griffith, L. S., Clouse, R. E., & Cryer, P. E. (1986). Psychiatric illness in diabetes mellitus: Relationship to symptoms and glucose control. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 174, 736-742. doi:10.1097/00005053-198612000-00005 Lykken, D., & Tellegen, A. (2006). Happiness is a stochastic phe- nomenon. Psychological Science, 7, 186-189. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00355.x Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of fre- quent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 803-855. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803 Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9, 111-131. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111 Manusov, E. G., Carr, R. J., Rowane, M., Beatty, L. A., & Nadeau, M. T. (1995). Dimensions of happiness: A qualitative study of family practice residents. The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice, 8, 367-375. Marinic, M., & Brkljacic, T. (2008). Love over gold—The correlation of happiness level with some life satisfaction factors between persons with and without physical disability. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 20, 527-540. doi:10.1007/s10882-008-9115-7 Martindale, C. & Moore, K. (1988). Priming, prototypicality, and pref- erence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 14, 661-670. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.14.4.661 Masicampo, E. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (2008). Toward a physiology of dual-process reasoning and judgment: Lemonade, willpower, and expensive rule-based analysis. Psychological Scienc e, 19, 255-260. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02077.x Mathes, E. W., & Kahn, A. (1975). Physical attractiveness, happiness, neuroticism, and self-esteem. Journal of Psychology, 90, 27-30. doi:10.1080/00223980.1975.9923921 Mathieu, S. I. (2008). Happiness and humor group promotes life satis- faction for senior center participants. Activities, Adaptation, and Ag- ing, 32, 134-148. doi:10.1080/01924780802143089 Matsubayashi, K., Kimura, S., Iwasaki, T., Okumiya, S., Hamada, T., Fujisawa, M. et al. (1992). Evaluation of subjective happiness in the elderly using a visual analogue scale of happiness in correlation with depression scale. Nippon Ronen Iqakkai Zasshi, 29, 811-816. doi:10.3143/geriatrics.29.811 Mayo, J. L. (1997). Premenstrual Syndrome: A natural approach to management. Applied Nutritional Science Reports, 5, 1-8. McCrimmon, R. J., Frier, B. M., & Deary, I. J. (1999). Appraisal of mood and personality during hypoglycemia in human subjects. Physiology and Behavior, 67, 27-33. doi:10.1016/S0031-9384(99)00035-9 McGreal, R., & Joseph, S. (1993). The depression-happiness scale. Psychological Reports, 73, 1279-1282. doi:10.2466/pr0.1993.73.3f.1279 McLanahan, S., & Adams, J. (1987). Parenthood and psychological well-being. A nn ua l Review of Sociology, 13, 237-257. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.13.080187.001321 Michalos, A. C. (1980). Satisfaction and happiness. Social Indicators Research, 8, 385-422. doi:10.1007/BF00461152 Michalos, A. C. (1983). Satisfaction and happiness in a rural northern resource community. Social Indicators Research, 13, 225-252. doi:10.1007/BF00318099 Mihalce, R., & Liu, H. (2006). A corpus-based approach to finding happiness. http://web.media.mit.edu/~hugo/publications/papers/CAAW2006-ha ppiness.pdf Moller, V., & Jackson, A. (1997). Perceptions of service delivery and happiness. Development Southern Africa, 14, 169-184. doi:10.1080/03768359708439958 Mookherjee, H. N. (1998). Perception of happiness among elderly persons in metropolitan USA. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 87, 787- 793. doi:10.2466/pms.1998.87.3.787 Moore, B. S., Clybrun, A., & Underwood, B. (1976). The role of affect in delay of gratification. Child Development, 47, 273-276. doi:10.2307/1128312 Mueller, P. S., Heninger, G. R., & McDonal, R. K. (1968). Intravenous glucose tolerance test in depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 21, 470-477. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1969.01740220086010 Mukherjee, D., & Basu, S. (2008). Correlates of happiness among young adults. National Academy of Psychology, India, 53, 67-71. Mulder, G. (1986). The concept and measurement of mental effort. In G. R. J. Hockey, A. W. K. Gaillard, M. G. H. Coles (Eds.), Energetical issues in research on human information processing (pp. 175-198). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-4448-0_12 Muraven, M., & Slessareva, E. (2003). Mechanisms of self-control failure: Motivation and Limited Resources. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 894-906. doi:10.1177/0146167203029007008 Muraven, M., Tice, D. M., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Self-control as a limited resource: Regulatory depletion patterns. Journal of Person- ality and Social Psychology, 74, 774-789. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.774 Namazie, C., & Sanfey, P. (1998). Happiness in transition: The case of Kyrgyzstan. Review of Developmental Economics, 5, 392-405. doi:10.1111/1467-9361.00131 Natale, V., & Albertazzi, P. (2006). Mood swings across the menstrual cycle: A comparison between oral contraceptive users and non-users. Biological Rhythm Rese ar c h , 37, 489-495. doi:10.1080/09291010600772451 Natvig, G. K., Albrektsen, G., & Qvarnstrom, U. (2003). Associations between psychosocial factors and happiness among school adoles- cents. International Journal of Nursing Pract ic e , 9, 166-175. doi:10.1046/j.1440-172X.2003.00419.x Nesse, R. M. (2004). Natural selection and the elusiveness of happiness. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B, 359, 1333-1347. doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1511 Neto, F. (2001). Personality predictors of happiness. Psychological Re- ports, 88, 817-824. doi:10.2466/pr0.2001.88.3.817 Nicolson, P. (1999). Loss, happiness and postpartum depression: The ultimate paradox. Canadian Psychology, 40, 162-178. doi:10.1037/h0086834 North, R. J., Holahan, C. J., Moos, R. H., & Cronkite, R. C. (2008). Family support, family income, and happiness: A 10-year perspec- tive. Journal of Family Ps yc holo gy, 22, 475-483. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.475 Odum, H. T. (1995). Self-organization and maximum empower. In C. A. S. Hall (Ed.), Maximum power: The ideas and applications of H. T. Odum. Colorado: Colorado University Press. Orden, S. R., & Bradburn, N. M. (1969). Working wives and marriage happiness. American Journal of Sociology, 74, 392-407. doi:10.1086/224664 Ortega, S. T., Whitt, H. P., & Williams, J. A. (1988). Religious ho- mogamy and marital happiness. Journal of Family Issues, 9, 224-239. doi:10.1177/019251388009002005 Oswald, A., & Powdthavee, N. (2008). Death, happiness, and the cal- culation of compensatory damages. The Journal of Legal Studies, 37, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 710  M. T. GAILLIOT 217-251. doi:10.1086/595674 Oswald, A. J., & Powdthavee, N. (2008). Does happiness adapt? A longitudinal study of disability with implications for economists and judges. Journal of Public Economics, 92, 1061-1077. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.01.002 Palmer, S. E. (1991). Goodness, gestalt, groups, and garner: Local symmetry subgroups as a theory of figural goodness. In J. R. Pom- erantz, & G. R. Lockhead (Eds.), Perception of structure (pp. 23-40). Washington DC: American Psychological Association. Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2006). Character strengths and happiness among young children: Content analysis of parental descriptions. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 323-341. doi:10.1007/s10902-005-3648-6 Perneger, T. V., Hudelson, P. M., & Bovier, P. A. (2004). Health and happiness in young Swiss adults. Quality of Life Research, 13, 171- 178. doi:10.1023/B:QURE.0000015314.97546.60 Peterson, C., Ruch, W., Beermann, U., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2007). Strengths of character, orientations to happiness, and life sat- isfaction. The Jour n al of Positive Psychology, 2, 149-156. doi:10.1080/17439760701228938 Phillips, D. L. (1967). Mental health status, social participation, and happiness. Mental Health and Happ iness, 72, 479-488. Phillips, D. L. (1967). Social participation and happiness. American Journal of Sociology, 72, 479-488. doi:10.1086/224378 Pickford, J. H., Signori, E. I., & Rempel, H. (1966). Similar of related personality traits as a factor in marital happiness. Journal of Mar- riage and the Family, 28, 191-192. doi:10.2307/349280 Pina, D. L., & Bengtson, V. L. (1993). The division of household labor and wives’ happiness: Ideology, employment, and perceptions of support. Journal of Ma rr iag e an d th e Family, 55, 901-912. doi:10.2307/352771 Popkin, M. K., Callies, A. L., Lentz, R. D., Colon, E. A., & Sutherland, D. E. (1988). Prevalence of major depression, simple phobia, and other psychiatric disorders in patients with long standing type I dia- betes mellitus. Archives of General Psychiatry, 45, 64-68. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800250078010 Posner, M. I., & Keele, S. W. (1968). On the genesis of abstract ideas. Journal of Experimental Ps ych olog y, 77, 353-363. doi:10.1037/h0025953 Rabin, C., & Shapira-Berman, O. (1997). Egalitarianism and marital happiness: Israeli wives and husbands on a collision course? The American Journal of Family Therapy , 25, 319-330. doi:10.1080/01926189708251076 Rapkin, A. (2003). A review of treatment of premenstrual syndrome & premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 28, 39- 53. doi:10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00096-9 Reber, R., Winkielman, P., & Schwarz, N. (1998). Effects of perceptual fluency of affective judgments. Psychological Science, 9, 45-48. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00008 Reid, M., & Hammersley, R. (1995) Effects of carbohydrate intake on subsequent food intake and mood state. Physiology and Behavior, 58, 421-427. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(95)00075-T Rhodes, G., & Tremewan, T. (1996). Averageness, exaggeration, and facial attractiveness. Psychological Science, 7, 105-110. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00338.x Rogers, S. J., & DeBoer, D. D. (2001). Changes in wives’ income: Effects of marital happiness, psychological well-being, and the risk of divorce. Journal of Marriage a nd the Family, 63, 458-472. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00458.x Rosch, E., & Lloyd, B. B. (1978). Cognition and categorization. Hills- dale, NJ: Erlbaum. Roysamb, E., Tambs, K., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T., Neale, M. C., & Harris, J. R. (2003). Happiness and health: Environmental and ge- netic contributions to the relationship between subjective well-being, perceived health, and somatic illness. Journal of Personality and So- cial Psychology, 85, 1136-1146. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.6.1136 Rubinow, D. R., Roy-Byrne, P., Hoban, M. C., Grover, G. N., Stambler, N., & Post, R. M. (1986). Premenstrual mood changes. Characteristic patterns in women with and without premenstrual syndrome. Journal of Affective Disorders, 10, 85-90. doi:10.1016/0165-0327(86)90030-3 Ryuichi, K., Takaaki, D., Akihiro, Y., Masanobu, O., Koki, T., Motomi, S., & Eiji, K. (1999). Happiness and background factors in commu- nity-dwelling older persons. Japanese Journal of Geriatrics, 36, 861- 867. doi:10.3143/geriatrics.36.861 Saunders, P. (2009). Income, health, and happiness. Ideas. URL (last checked 21 May 2009). http://ideas.repec.org/a/bla/ausecr/v29y1996i4p353-366.html Schmeichel, B. J., Vohs, K. D., & Baumeister, R. F. (2003). Intellectual performance and ego depletion: Role of the self in logical reasoning and other information processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 33-46. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.1.33 Schmeichel, B. J., Demaree, H. A., Robinson, J. L., & Pu, J. (2006). Ego depletion by response exaggeration. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42, 95-102. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2005.02.005 Scholey, A. B., & Kennedy, D. O. (2004). Cognitive and physiological effects of an “energy drink”: An evaluation of the whole drink and of glucose, caffeine and herbal flavouring fractions. Psychopharmacol- ogy, 17, 320-330. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-1935-2 Schwartz, B., Ward, A., Monterosso, J., Lyubomirsky, S., White, K., & Lehman, D. R. (2002). Maximizing versus satisficing: Happiness is a matter of choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 1178-1197. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.83.5.1178 Schwarz, J. C., & Pollack, P. R. (1977). Affect and delay of gratifica- tion. Journal of Research in P ersonality, 11, 147-164. doi:10.1016/0092-6566(77)90013-7 Schyns, P. (1998). Crossnational differences in happiness: Economic and cultural factors explored. Social Indicators Research, 43, 3-26. doi:10.1023/A:1006814424293 Selim, S. (2008). Life satisfaction and happiness in Turkey. Social Indicators Research, 88, 531-562. doi:10.1007/s11205-007-9218-z Shamosh, N. A., & Gray, J. R. (2007). The relation between fluid intel- ligence and self-regulatory depletion. Cognition and Emotion, 21, 1833-1843. doi:10.1080/02699930701273658 Shin, D. C., & Johnson, D. M. (1978). Avowed happiness as an overall assessment of the quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 5, 475- 492. doi:10.1007/BF00352944 Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Winton, A. S. W., Wahler, R. G., Singh, J., & Sage, M. (2004). Mindful caregiving increases happiness among individuals with profound multiple disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabiliti es, 25, 207-218. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2003.05.001 Smith, A. P., Clarka, R., & Gallaghera, J. (1999). Breakfast cereal and caffeinated coffee effects on working memory, attention, mood, and cardiovascular function. Physiology & Behavior, 67, 9-17. doi:10.1016/S0031-9384(99)00025-6 Solomon, S. J., Kurzer, M. S., & Calloway, D. H. (1982). Menstrual cycle and basal metabolic rate in women. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 3 6, 611-616. Stack, S., & Eshleman, J. R. (1998). Marital status and happiness: A 17-nation study. Journal of Mar r iage and Family, 60, 527-536. doi:10.2307/353867 Steel, P., & Ones, D. S. (2002). Personality and happiness: A national- level analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 767-781. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.83.3.767 Storm, C. (1996). Aspects of meaning in words related to happiness. Cognition and Emotion, 10, 279-302. doi:10.1080/026999396380259 Stutzer, A. (2004). The role of income aspirations in individual happi- ness. Journal of Economic Be h avior and O rgani zation, 54, 89-109. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2003.04.003 Suitor, J. J. (1987). Marital happiness of returning women students and their husbands: Effects of part and full-time enrollment. Research in Higher Education, 27, 311-331. doi:10.1007/BF00991661 Swinyard, W. R., Kau, A.-K., & Phua, H.-Y. (2001). Happiness, mate- rialism, and religious experience in the US and Singapore. Journal of Happiness Studies, 2, 13-32. doi:10.1023/A:1011596515474 Symonds, C. S., Gallagher, P., Thompson, J. P., & Young, A. H. (2004). Effects of the menstrual cycle on mood, neurocognitive and neuro- endocrine function in healthy premenopausal women. Psychological Medicine, 34, 93-102. doi:10.1017/S0033291703008535 Taylor, L. A. & Rachman. S. J. (1988). The effects of blood sugar level changes on cognitive function, affective state, and somatic symptoms. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 711  M. T. GAILLIOT Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 712 Journal of Behavioral Medici ne , 11, 279-291. doi:10.1007/BF00844433 Tella, R. D., & MacCulloch, R. (2007). Gross national happiness as an answer to the Easterlin Paradox? Journal of Developmental Eco- nomics, 86, 22-42. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2007.06.008 Tella, R. D., MacCulloch, R. J., & Oswald, A. J. (2003). The macro- economics of happiness. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 85, 809-827. doi:10.1162/003465303772815745 Tella, R. D., New, J. H.-D., & MacCulloch, R. (2007). Happiness ad- aptation to income and to status in an individual panel. URL (last checked 13 May 2009). http://ssrn.com/abstract=992162 Tice, D. M., Baumeister, R. F., Shmueli, D., & Muraven, M. (2007). Restoring the self: Positive affect helps improve self-regulation fol- lowing ego depletion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43, 379-384. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2006.05.007 Tice, D. M., Bratslavsky, E., & Baumeister, R. F. (2001). Emotional distress regulation takes precedence over impulse control: If you feel bad, do it! Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 53-67. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.80.1.53 Tkach, C., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How do people pursue happiness? Relating personality, happiness-increasing strategies, and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 183-225. doi:10.1007/s10902-005-4754-1 Tsou, M. W., & Liu, J. T. (2001). Happiness and domain satisfaction in Taiwan. Journal of Happiness Studies, 2, 269-288. doi:10.1023/A:1011816429264 Uchida, Y., Norasakkunkit, V., & Kitayama, S. (2004). Cultural con- structions of happiness: Theory and empirical evidence. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5, 223-239. doi:10.1007/s10902-004-8785-9 Van Pragg, H. M., & Leijnse, B. (1965). Depression, glucose tolerance, peripheral glucose uptake and their alterations under the influence of anti-depressive drugs of the hydrazine type. Psychopharmacologica, 8, 67-78. doi:10.1007/BF00405362 Veenhoven, R. (1988). The utility of happiness. Social Indicators Re- search, 20, 333-354. doi:10.1007/BF00302332 Veenhoven, R. (1991). Is happiness relative? Social Indicators Resear- ch, 24, 1-34. doi:10.1007/BF00292648 Vohs, K. D., Baumeister, R. F., & Ciarocco, N. J. (2005). Self-regula- tion and self-presentation: Regulatory resource depletion impairs impression management and effortful self-presentation depletes regulatory resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 632-657. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.88.4.632 Ward, R. A. (1993). Marital happiness and household equity in later life. Journal of Marriage and Family, 55, 427-438. doi:10.2307/352813 Webb, P. (1981). Increased levels of energy exchange in women after ovulation. The Physiologist, 24, 43. Webb, P. (1986). 24-hour energy expenditure and the menstrual cycle. The American Journal of Clinical Nut r it i o n, 44, 614-619. Weinhold, D. (2008). How big a problem is noise pollution? A brief happiness analysis by a perturbable economist. URL (last checked 22 May2009). http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/10660/2/The_utility_costs_of_noise_p ollutionv3.pdf Weiss, A., Bates, T. C., & Luciano, M. (2008). Happiness is a per- sonal(ity) thing: The genetics of personality and well-being in a rep- resentative sample. Psychological Science, 19 , 205-210. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02068.x Wells, K. B., Golding, J. M., & Burnam, M. A. (1989). Affective sub- stance use, and anxiety disorders in persons with arthritis, diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, or chronic lung conditions. Gen- eral Hospital Psychiatry, 11, 320-327. doi:10.1016/0163-8343(89)90119-9 Welsch, H. (2008). The social costs of civil conflict: Evidence from surveys of happiness. Kyklo s, 61, 320-340. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6435.2008.00404.x White, L. K., Booth, A., & Edwards, J. N. (1986). Children and marital happiness. Journal o f Family Issues, 7, 131-147. doi:10.1177/019251386007002002 Whittlesea, B. W. A. (1993). Illusions of familiarity. Journal of Ex- perimental Psychology : Learning, Memory, and Cognitio n , 1 9, 1235- 1253. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.19.6.1235 Whittlesea, B. W. A., Jacoby, L. L., & Girard, K. (1990). Illusions of immediate memory: Evidence of an attributional basis for feelings of familiarity and perceptual quality. Journal of Memory and Language, 29, 716-732. doi:10.1016/0749-596X(90)90045-2 Wikipedia (2012). Wikipedia entries for dopamine, acetylcholine, GABA, and glutamate. www.wikipedia.org Wilson, D. R. (1951). Electroencephalographic studies in diabetes mellitus. Canadia n Medical Association Journal, 65 , 462-465. Witherspoon, D., & Allan, L. G. (1985). The effects of a prior presenta- tion on temporal judgments in a perceptual identification task. Mem- ory and Cognition, 13, 103-111. doi:10.3758/BF03197003 World Bank (1997). World values survey. World Development Report. Wredling, R. A. M., Theorell, P. G. T., Roll, M. H., Lins, P. E. S., & Adamson, U. K. C. (1992). Psychosocial state of patients with IDDM prone to recurrent episodes of severe hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care, 75, 518-521. doi:10.2337/diacare.15.4.518 Yaryura-Tobias, J. A., & Neziroglu, F. A. (1975). Violent behavior, brain dysrhythmia, and glucose dysfunction: A new syndrome. Jour- nal of Orthomolecular Psychi a t ry, 4, 182-188. Yu, D. C. T., Spevack, S., Hiebert, R., Martin, T. L., Goodman, R., Martin, T. et al. (2002). Happiness indices among persons with pro- found and severe disabilities during leisure and work activities: A comparison. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and De- velopmental Disabilities, 37, 421-426. Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psycho l o g y : Monograph Supplemen t , 9, 1-27. doi:10.1037/h0025848 Zajonc, R. B. (2001). Mere exposure: An unmediated process. URL (last checked 5 November 2001). http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.23.3462 Zajonc, R. B. (2002). Mere exposure: A gateway to the subliminal. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 224-228. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00154 Zhao, G., Wang, L., Qu, C., & Wang, X. (1998). Personality and cli- macteric syndrome in women. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 12, 163-137.

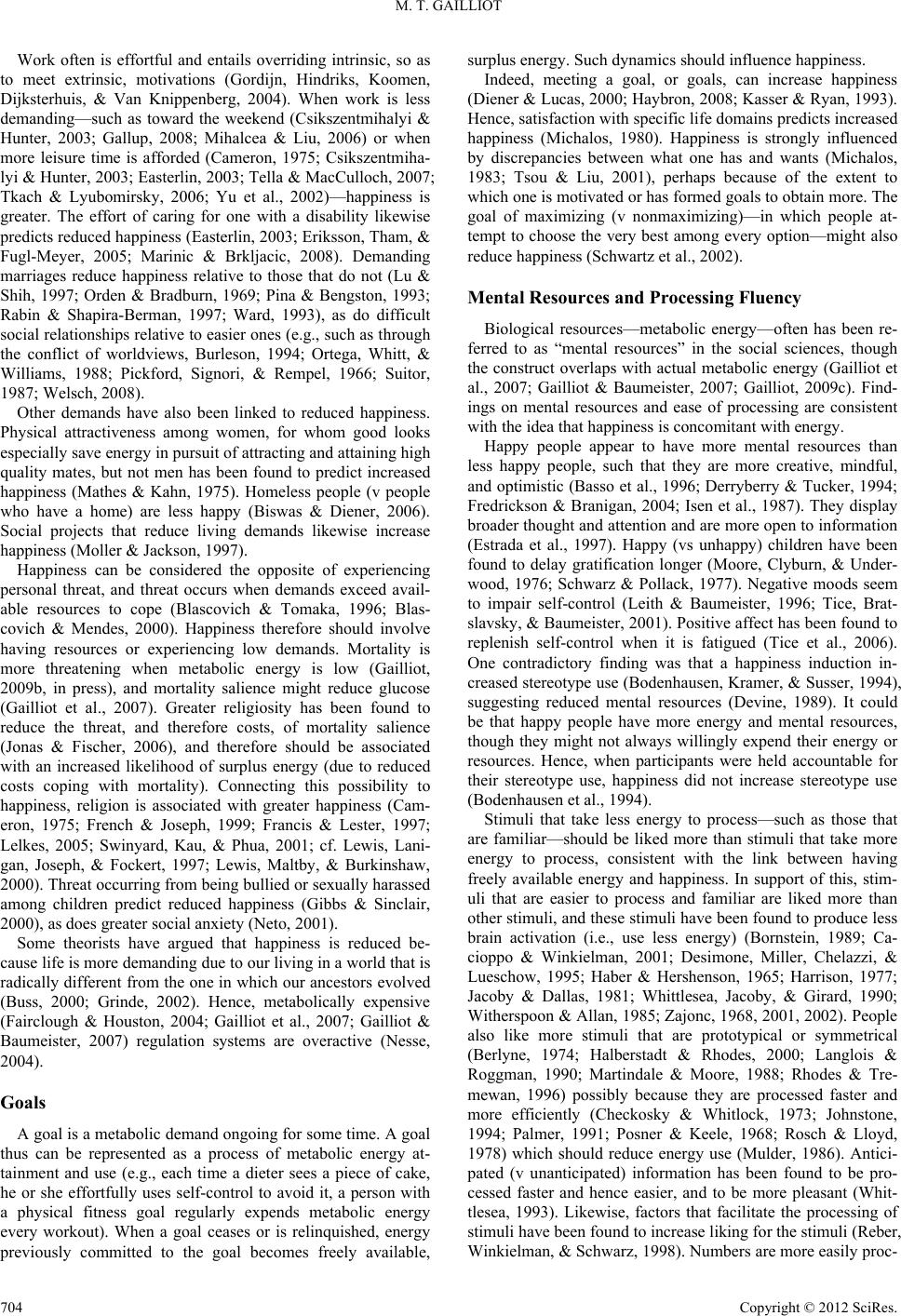

|