Vol.2, No.7, 742-752 (2010) doi:10.4236/health.2010.27113 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Health Barriers and facilitators to mexican-american participation in clinical trials: physician and patient focus group perspectives Jesse Nodora1, Tomas Nuño2, Ken O’Day3, Virginia Yrun2, Francisco Garcia2* 1National Center of Excellence in Women’s Health and the Arizona Cancer Center, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA 2National Center of Excellence in Women’s Health and the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA; *Corresponding Author: fcisco@u.arizona.edu 3Xcenda, Palm Harbor, USA Received 16 March 2010; revised 21 April 2010; accepted 22 April 2010. ABSTRACT Racial/ethnic minority populations are under- represented in clinical trials and Hispanic par- ticipation rates are particularly low. This study assessed barriers and facilitators to clinical tri- als participation by Medicaid eligible Mexican- Americans and their serving physicians. Quali- tative data from two focus groups conducted among Mexican-American Medicaid eligible pa- tients and four physician focus groups were analyzed. Mexican-American patients have a basic understanding of clinical trials. While m o st are open to p articip ating in clinical research, not speaking English, time, and transportation were identified as barriers. Physicians believe that desperation and financial need are the primary patient motivators for participation. Barriers to physician recruitment and referral include: lack of information about clinical trials, concern that study participation may not be in the patient’s best interest, and lack of staffing and time to conduct trials. Ample opportunities exist to en- gage providers and patients in future efforts to increase Mexican-American patient recruitment into clinical trials. Keywords: Clinical Trials Participation; Mexican-American; Hispanic; Medicaid Patients; Medicaid Physicians; Foc us Groups; Qualitative Methods 1. INTRODUCTION In a poll of clinical investigators conducted by Applied Clinical Trials, 56% of respondents identified participant recruitment as the most pressing issue in the conduct of clinical trials [1]. Difficulty in recruiting participants increases the time it takes to complete clinical trials, delays approval of new medications, and reduces incen- tives for drug development. Recruitment appears to be particularly challenging among racial/ethnic minority populations, and these groups tend to be seriously un- derrepresented in clinical trials [2]. Under representation of minority populations in clinical trials limits our un- derstanding of the wide range of biological, social, and cultural factors that influence treatment response and reduces the generalizability of new treatments to minor- ity groups; it thus may contribute to health disparities [3, 4]. Also, as a matter of equity, those suffering from dis- ease should have access to new and promising treat- ments through clinical trials, regardless of their racial and ethnic identities. As part of the National Institutes of Health Revitaliza- tion Act of 1993, the United States Congress mandated that women and minorities be included in clinical trials in a manner “sufficient to elicit information about indi- viduals of both sexes/genders and diverse racial and eth- nic groups” [5]. Despite this mandate, recent studies continue to show disproportionately low participation levels by minorities in clinical trials [6-9], and participa- tion by Hispanics is especially low. For example, a study of US National Cancer Institute (NCI) sponsored clinical trials found that Hispanics were the most under repre- sented racial/ethnic group [8]. Research into the factors responsible for under representation of minorities in clinical trials has largely focused on African-Americans, and comparatively little of this research has explored barriers among other ethnic racial/minority groups [6]. The process of recruiting patients to clinical trials in- volves both patients and the clinical investigators (or their representatives) who are responsible for presenting  J. Nodora et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 742- 752 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 743 743 the trial for consideration by patients. Two recent reports on clinical trials recruitment among racial/ethnic minori- ties recommended more research to explore factors and mechanisms influencing patient-provider roles, especial- lly those related to clinical trials communication [10,11]. Both reports suggested that clinical trials education is most likely to reach minority populations by providing tailored information to non-specialists primary health care providers in a community setting. The term Hispanic includes individuals identified by the Office of Management and Budget Directive 15 as “A person of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central or South American, or other Spanish culture or origin, re- gardless of race” [12]. By 2050 it is estimated that one out of every four Americans will be of Hispanic ethnic- ity [13]. Persons of Mexican descent account for over 60% of all US Hispanics (the next closest group, Puerto Ricans, account for less than 10% of all US Hispanics) [14]. Also, Mexicans represent 32% of all US immi- grants, the next closest group (Filipinos) are at 5% [15]. Although Hispanics share a common language, there are many cultural differences among the various sub-groups. In the present report, we focus on Mexican- Americans, the largest group of Hispanics in the US, and present the results of a series of focus groups designed to explore perceived barriers and facilitators to clinical trial partici- pation among both Mexican-American patients and the physicians who care for them. 2. METHODS We conducted focus groups with Mexican-American Medicaid eligible patients and their serving physicians to learn about barriers and facilitators to clinical trial par- ticipation. Structured open-ended interview-guided pa- tient focus groups explored issues around patient bar- riers and facilitators to participating in clinical trials. Using the same technique, physician focus groups ex- plored issues around patient barriers and facilitators and physician barriers and facilitators to recruitment and referral of patients to clinical trials. A total of six focus groups were conducted between May and August 2006. Two focus groups were conducted with patients, two with physicians that do not recruit or refer patients to clinical trials, and two with physicians that do recruit or refer patients to clinical trials. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Arizona. The study participants for the patient focus groups were Mexican-American Medicaid eligible patients. All were residents of Maricopa County in central Arizona. Patients were recruited by telephone from a comer- cially available list of Hispanic households. Patients were queried using a series of screening questions (Ta- ble 1) and were invited to participate if they: 1) made health care decisions for themselves or their family; 2) had interacted with the health care system within the past 18 months; 3) were between the ages of 30 and 65; and, 4) were Medicaid eligible (i.e., had a household income of less than 100% of the Federal poverty level). The study participants for the physician focus groups were community primary care physicians who serve Medicaid patients. Physicians were recruited by tele- phone using a list of Medicaid eligible providers and were queried about whether they recruit or refer patients to clinical trials. Physicians that recruited or referred patients to clinical trials and those that did not recruit or refer patients were invited to participate in separately scheduled focus groups. Trained interviewers conducted each focus group us- ing a structured interview guide. The interview guide was developed and revised through an iterative process involving the above noted literature review of barriers and facilitators to patient participation in clinical trials. In addition, members of the research team conducted an expert review, and a sample of Mexican-American wo- men visiting the Women’s Health & Resource Center performed a community member review. Questions on the interview guide were open-ended and aimed to elicit participants’ thoughts and feelings on various issues re- lating to clinical trials, recruitment, and participation. Patient interview guides also included questions about patients’ awareness and attitudes about clinical trials, participation in clinical trials, barriers and facilitators to participation, and the role of culture and ethnicity. Phy- sician interview guides included questions about patient barriers and facilitators, patient characteristics that affect patient willingness to participate, physician experiences in recruiting or referring patients, and physician barriers and facilitators to recruiting or referring patients. The patient focus groups were conducted in Spanish and the physician focus groups were conducted in Eng- lish. Focus groups ranged in size from 5 to 9 participants and each session lasted between 90 and 120 minutes. All focus groups took place in a focus group interviewing room with integrated audio recording equipment. All focus groups were audiotaped. Patient focus groups conducted in Spanish were subsequently translated and transcribed into English. Physician focus groups were transcribed verbatim in English. Two members of the research team read and re- viewed the transcribed focus group interviews for themes and codes in a two-part process. First, a concept- tual model of factors affecting patient participation in clinical trials, based on a model developed for AHRQ, was revised and used to develop a set of themes and  J. Nodora et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 742- 752 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 744 Table 1. Patient and physician focus group questions. Patient Questions (Spanish) Healthcare system (El Sistema de Salud) 1. Do you have a regular doctor that you see? In choosing your doctor what’s important to you? (¿Tiene un doctor que visita con regularidad? En elegir a su doctor, ¿que es importante para usted?) 2. As a Hispanic, how important is it for you to have a doctor who is Hispanic or who understands your langua ge and culture? (¿Como Latino/a, que importancia tiene para usted tener un médico que es Latino o que entienda su idioma y cultura?) Attitudes about Research and Clinical Trials (Actitudes Sobre las Investigaciones y los Ensayos Clínicos) 1. What do you think about medical research? (¿Qué piensan sobre las investigaciones médicas?) 2. Who benefits from medical research? (¿Quién beneficia de las investigaciones médicas?) Participation in Research and Clinical Trials (Participación en las Investigaciones y los Ensayos Clínicos) 1. Has anyone ever been aske d to participate in a clinical trial or had a family member who was asked to participate in a clinical t rial? (¿Alguien de ustedes ha sido invitado a participar en un ensayo clínico o han invitado algún miembro de su familia a participar en un ensayo clínico?) 2. Now, even for those of you who haven’t ever been asked to participate, I’d like you to imagin e a s i t u a t i o n w h e re you visit your doctor for some health problem and toward the end of your visit your doct or me nt ion s th at yo u m ig ht be eligible to participate in a clinical trial. How would you feel about participating? (Ahora, para los que nunca han sido invitados a participar, imagínense una situación donde visitas a su médico y al final de su visita su médico menciona que quizás sea candidato para participar en un ensayo clínico. ¿Cómo se sentiría acerca de participar?) Barriers and Facilitators (Barreras y Promotores) Let’s talk about some specific reasons that would influence you or someone in your family when making a decision about whether to participate in a clinical trial (Hablemos acerca de algunas de las razones que podrían influir su decisión, o la decisión de un familiar, para participar en un ensayo clínico) 1. What are some of the reasons you might decide to participate? (¿Cuáles son algunas de las razones para participar?) 2. What are some of the reasons you might decide NOT to participate? (¿Cuáles son algunas de las razones por cual NO participará?) Culture and Ethnicity (Cultura y Origen Étnico) 1. Do cultural and language issues influence your decision to participate in a c li n ic a l t ri a l? (¿La cultura y el idioma influyen su decisión para participar en un ensayo clínico?) 2. Would being approached by a doctor who is Hispanic or who understands your language and culture influence your decision to par- ticipate? (¿Influyera su decisión para participar siendo invitado por un médico Hispano o de habla Hispana que entienda su cultura?) 3. Do you think physicians are more or less likely to ask Hispanic patients to participate in clinic a l tri al s? (¿Piensa que es más, o menos, probable que los médicos piden a Hispanos que participen en ensayos clínicos?) Physician Questions Physicians Thoughts on Patients and Clinical Trials Participation 1. How aware would you say your typical patient is of clinical trials? Do they know what t hey are for? 2. Do you think the exis tence of clinical trials is well communicated (to patie nt s) in general? 3. When patients bring up the subject of clinic al tri als do they have any preconceptions? 4. What are your thoughts on your (Medicaid) patient’s [knowledge, interest, and barriers/facilitators] related to clinical trials partici- pation? 5. How does Hispanic culture influence clinical trials participation for Medicaid patients ? 6. How can physicians increase clinical trial s p articipation among their Hispanic Medic aid pa tients? Physician Facilitators and Barriers to Clinical Trials Participation 1. Have you referred patients to cli n i c a l trials? Was this a p os it iv e or n eg a ti ve experience? 2. What is your interest in increasing your involvement in clinica l research activities? 3. What would facilit a t e achievement of your desired research activity level (issues and solutions for physicians involved in research versus those not involved in research)?  J. Nodora et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 742- 752 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 745 745 codes [6]. Transcripts were independently reviewed by two researchers, and passages were thematically classi- fied as they related to the following patient and physic- cian themes: awareness, attitudes, resources, and oppor- tunities. The researchers then met to review these classi- fications and resolve disagreements. The result of this systematic review process was a set of passages from each transcript for each theme-code pair. 3. RESULTS A summary of patient and provider focus group out- comes are shown in Table 2 and more detailed results are presented in the following sections. Please note that the qualitative nature of focus group results does not easily allow for exact quantification of responses. As a general reference, when we state that “some,” “many,” or “most” participants provided a given response the approximate percentages are 40, 70 and 90 percent, re- spectively. 3.1. Patient Focus Groups The two patient focus groups included a total of 13 Me- xican-Americans who met eligibility criteria for Medi- caid services. Most participants (77%) were women, and the mean age was 39 years. 3.1.1. Patient Awareness Patients expressed a basic understanding that clinical trials involve research to determine whether medications and treatments are safe and effective. However, some patients believe that clinical trials involve practice by inexperienced physicians. None of the patients in our focus group sample had participated in a clinical trial, but some reported that friends or family members had participated. 3.1.2. Patient Attitudes Most patients believe that clinical trials are good and help to advance science. The most commonly expressed reasons for not participating in clinical trials included: fear of adverse events, lack of trust in the physician, and being part of an experiment in which inexperienced phy- sicians/health care providers are involved. A commonly expressed reason for considering participation was the development of more effective medications that would benefit the participant and others. Many patients ex- pressed that they would like more information about clinical trials before making a decision about whether to participate. Most patients indicated that they would consult their family members to help them decide wh- ether to participate. Also, most of the patients in the fo- cus group indicated that they would be willing to par- ticipate and indicated that trust in their physician would be a significant factor in their decision. 3.1.3. Patient Resources Time constraints and transportation pose barriers for some patients. For patients who lack access to health care or medications, obtaining access to care or medica- tions through a clinical trial would be an incentive to participate. Many patients indicate that they would like better information to help them understand what clinical trials are about and they believe that television would be the best medium to inform and educate Mexican- American communities. 3.1.4. Patient Opportunities Patients believe that being Spanish speaking (not speak- ing English) poses a significant barrier to participation and that translators are often inadequate or unavailable. Patients believe that as Mexican-Americans, they are less likely to be asked to participate in clinical trials, primarily due to the language barrier. 3.2. Physician Focus Groups The four physician focus groups included a total of 26 doctors, of whom 6 (23%) were women and 4 (15%) were Hispanic. Their clinical practice specialties were 14 (54%) in family medicine, 6 (23%) in internal medicine, and 6 (23%) in other types of medical practice. 3.2.1. Physician Perception of Patient A wareness Physicians think that patients have little awareness or understanding of clinical trials. Physicians have differing views regarding how a patient’s level of education af- fects their understanding: some believe that Medicaid patients have more difficulty understanding what clinical trials are, while others think Medicaid patients are no different from other patients. Non-recruiting physicians indicate that patients sometimes bring up clinical trials seeking physician reassurance or approval before par- ticipating. Some non-recruiting physicians believe that patients tend to overestimate the likelihood of side ef- fects from study medications. 3.2.2. Physician Perception of Patient Attitudes Physicians believe that patients with severe disease and those who are in financial need are more inclined to par- ticipate in clinical trials. Physicians believe that their relationship with patients can be very influential upon patient attitudes toward participating in clinical trials. Some recruiting physicians indicate that patient fear of side effects is a barrier. Many non-recruiting physicians indicated that Mexican-American patients are private and may take some time to develop trust, but once trust is established they are very trusting of their physicians.  J. Nodora et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 742- 752 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 746 Table 2. Focus group patient and physician outcomes. PATIENTS Facilitators Barriers Want to participate in clinical trials Believe clinical trials are done by inexperienced physicians Will ask physicians about clinical trials Fear adverse effects and experimentation With physician’s trust will participate in clinical trials Lack of trust in the physician Believe clinical trials help advance science Time constraints Believe clinical trials help develop better drugs Lack of transportation Have basic understanding of clinical trials as research Being Mexican-American (language & culture) Use television to recruit Mexican-Americans Speaking only Spanish PHYSICIANS Facilitators Barriers Want more information on clinical trials Get little information on clinical trials When clinical trials provide physician assistance and needed resources Do not know where to go for information on clinical trials Community physicians can be effective in recruitment Believe patients are likely to overestimate side effects Electronic medical records Believe patients know little about clinical trials Clinical trial medications and procedures Loss of patients to clinical trials Continued access to medication(s) after clinical trial ends Fear of being perceived as “on the take” by patients Lack of staffing and time Difficult to follow up some Mex. Am. Patients Some recruiting physicians believe that Mexican-Ame- rican patients are more difficult to recruit, but other re- cruiting physicians indicate that Mexican-American pa- tients are no different from other patients in terms of their receptiveness to participation. 3.2.3. Physician Perception of Patient Resources Economic hardship was thought to be an incentive for some patients to participate, but that it also makes clini- cal trials a low priority for patients who are experiencing economic hardship. Most physicians believed that trans- portation and distance are barriers for many patients, and that the impact of clinical trial participation on patient’s employment may be potentially detrimental. Some re- cruiting physicians believe data collection burdens are a barrier to patient participation. 3.2.4. Physician Perception of Patient Opportunities Some recruiting physicians stressed that there is consid- erable cultural variety among Mexican-American patients. Some physicians believe that their patient population’s limited interaction with the health care system and the difficulty their offices encounter in contacting and fol- lowing up with patients may limit opportunities for par- ticipation. Some thought that better advertising and get- ting interested community physicians involved in re- cruitment might also help improve patient opportuni- ties. 3.2.5. Physician Awareness Most physicians indicate that they get very little infor- mation about clinical trials and would like additional information about studies. Many physicians say that they do not know where to obtain information about clinical trials and are only aware of trials that they see ads for in the newspaper or hear about on the radio. 3.2.6. Physician Attitudes Many physicians express concern about whether their patients would continue to have access to the study medication after the study is over. Some physicians are concerned about how they will be perceived by their patients if they recruit or refer them to clinical trials. A few of these physicians expressed ethical concerns about conflict of interest and that patients would perceive them as being “on the take,” (i.e., receiving inappropriate co-  J. Nodora et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 742- 752 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 747 747 mpensation for putting patients on a given study) par- ticularly in the case of “skeptical minority” patients. Some physicians expressed general concern that partici- pation in clinical trials may not be in their patient’s best interest. Others voiced a specific concern that patients will be assigned a placebo intervention and that this might adversely impact their treatment plan. Some phy- sicians are worried that referring or recruiting patients to clinical trials could potentially raise liability issues, or may lead to the eventual loss of the patient after the study is completed. Recruiting physicians believe that altruism is a limited patient motivation for participating. Physicians are more favorably disposed toward studies involving important new medications and less favorable toward studies involving “me too” drugs (i.e., slight modification of an existing drug). Some physicians pre- fer to leave the subject of clinical trials participation for the patient to initiate and will only discuss the subject if the patient brings it up. Some non-recruiting physicians were quite favorably inclined toward clinical trials, while others are very skeptical. Some recruiting physicians said that they were motivated to recruit or refer patients in order to help them. 3.2.7. Physician Resources Lack of staffing was identified by many physicians as a barrier to conducting recruitment and referral activities. Some of these physicians indicated that a research study coordinator would be necessary to conduct recruitment and referral activities in their office. Physician time con- straints also limit the ability to recruit or refer patients. Some physicians were concerned that referring patients to clinical trials might result in a loss of patients for their practice, and a negative economic impact. Most physic- cians indicated that assistance (e.g., administrative coor- dination, provider and patient materials) would be nec- essary for them to recruit or refer patients to clinical trials. 3.2.8. Physician Opportunities Some recruiting physicians say that they do not receive much information about trials and have had to take the initiative to identify study opportunities for patient re- cruitment and referral. For many this represents an inor- dinate burden for routine referral of patients to clinical trials. Some recruiting physicians believe that electronic medical records have made it easier for them to partici- pate in referring or recruiting patients by improving their ability to identify eligible patients and more easily tran- sfer information. 4. DISCUSSION Without presenting the many research-related social (e.g., culture, racism) and demographic (e.g., race, ethnicity) complexities among such a large and heterogeneous group [4], it is clear that compared to non-Hispanic whites, US Hispanics are less educated, and more im- poverished [16], and also face significant challenges in health care access, information, and knowledge [17]. This demographic and healthcare profile, coupled with the disproportionately low clinical trials participation rate, increases the urgency of understanding and address- ing the barriers to Hispanic participation in clinical trials, especially among those of Mexican descent, which com- prises the largest sub-group [14]. The results of our study on barriers and facilitators to Mexican-American clinical trials participation corrobo- rate the findings of previous research; including many of those outlined in the recent Ford, et al. systematic review [2]. Our conceptual model, shown in Figure 1, is adap- ted from the Ford, et al. conceptual framework (Figure 8, p. 239) Our model integrates the key barriers and fa- cilitators within each of four domains (awareness, atti- tude, resources, and opportunities) selected for this study. As depicted in Figure 1, we propose that the opportunity to participate in a clinical trial (for both patients and providers) must be present, and that the decision to ac- cept or refuse is influenced by the facilitators and barri- ers in each of the four domains. The Ford, et al., model and our conceptual model share the Awareness and Op- portunities domains. Based on our experience, and the iterative process described in the Methods, we chose to add the Attitude and Resources domains. These two do- mains provide an important link between awareness (i.e., of clinical trial and what it offers) and action (ac- cept/refuse to participate). In addition, the Resources domain captures many of the critical facilitators and bar- riers relevant to both patients and providers. Our findings provide a concurrent perspective on clinical trials participation from both Medicaid eligible patients and the physicians who serve them. The impre- ssion from our study participants is generally favorable towards clinical trials research. Nevertheless, we found important facilitators and barriers among both patients and physicians (See Table 2 an d Figure 1). Both patients and clinicians are interested in clinical trials. Both express the practical barriers of time and need for assistance. The most complex, and often most difficult to overcome barriers for our participants revolve around not being fluent in English; where providers (and their staff) are not fluent in Spanish. While patients face fears of adverse effects and “experimentation,” physic- ians face fears of being perceived as having a conflict of interest for referring patients to clinical trials and their patients not having access to medications once off study. Fortunately, many of the facilitators and barriers provide tangible opportunity for intervention.  J. Nodora et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 742- 752 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 748 Symbols: (+) indicates facilitator. (–) indicates barrier. Description: Faced with the opportunity to participate in a clinical trial, consideration of facilitators (+) and barriers (–) within the four domains (awareness, attitude, resources, opportunities) will influence patient and provider acceptance or refusal to participate. Figure 1. Focus group results applied to proposed conceptual model. Most patients indicated that they were open to the idea of participating in clinical trials and believe that results of these help to advance science and medicine. This is consistent with recent findings from Markman et al. [18] and Wendler et al. [19] who found that both Hispanics, and African Americans, are as interested, or more inter- ested, in learning about clinical trials as Caucasians. Ef- forts to educate and inform Mexican-Americans and other Hispanic patients about clinical trials should build upon this support and beliefs by clearly explaining the role of clinical trials in the development of new treat- ments that are safe and effective and emphasizing that the strict treatment protocols in clinical trials serve to ensure the provision of high quality care. Given that Mexican-American patients indicate that they would like additional information about clinical trials and believe television would be the best medium to reach them, de- velopment of appropriate television-based clinical trials messages may help to educate and recruit Hispanic pa- tients. There was near universal agreement among the patient focus group participants that language and culture pose significant barriers to participation in clinical trials for Mexican-Americans. There was also near universal ag- reement that fluency in Spanish is more important than the ethnicity of their physician. Most patients were, in fact, indifferent to the ethnicity of the physician. Some patients perceive Mexican-Americans as less likely to be asked to participate due to language barriers rather than discrimination. Such barriers may be reduced by pro- viding physicians who serve Hispanic patients, as well as Spanish speaking study recruiters, with education and outreach on appropriate Spanish language information about clinical trials. Ramirez et al., suggest not only outreach and education to address patient-provider lan- guage issues, but effective use of bilingual study teams [10]. Addressing language and culture may have the ad- ded benefit of facilitating family communication, under- Openly accessible at  J. Nodora et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 742- 752 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 749 749 standing, and approval of clinical trials, which was iden- tified as an important factor in patient decision making. Of particular concern in our findings is that some of the participants believed that clinical trials involve ex- perimentation, “practice” by inexperienced physicians, and frequent adverse events (i.e., side effects). These findings are similar to those in a recent nationally repre- sentative 1000 person telephone survey, which found that African Americans and Hispanics are more likely than whites to associate clinical trials participation with more discomfort, pain, and side effects and to believe that they are better off with the standard treatment [9]. This is partially related to recent research on barriers to the recruitment of African Americans to clinical trials [20-24]. This literature presents the significant feelings of mistrust experienced by African Americans toward medical researchers due to a long documented history of research abuses in this population. While our study par- ticipants (both patients and providers) did not voice mis- trust specific to historical reasons related to research abuse, physician trust was identified as an important factor for clinical trials participation. There are likely many complexities related to how a trusting relationship is achieved, not least among them, the ability to commu- nicate (language), and cultural respect. This complexity creates many challenges to within and across group (Af- rican American-Hispanic) generalization, particularly in quantitative studies, and suggests the need to account for key associations (e.g., stratify by racial/ethnic origin, language, nativity, etc.) [25]. Limited patient resources—including time, transporta- tion, and finances—appear to pose significant barriers to Mexican-American participation in clinical trials. This is not unexpected given that the patient focus group par- ticipants for this study were all under the Federal pov- erty level. While similar barriers may apply to low in- come non-Hispanic patients, any efforts to address the under representation of Mexican-Americans and other Hispanics in clinical trials will need to address these barriers due to the fact that these patients are dispropor- tionately represented among low income and uninsured populations [26]. With concurrent patient and physician data lacking, results of the present study add an important dimension to the study of facilitators and barriers to clinical trials participation. Physician focus group participants, in the two non-referring/non-recruiting groups and the two referring/recruiting groups, were in general agreement on many topics and raised similar themes. The similari- ties appeared to be greater when physicians were dis- cussing issues related to patient awareness, attitudes, resources, and opportunities. The larger differences be- tween the non-referring/non-recruiting groups and the referring/recruiting groups tended to involve physician awareness, attitudes, resources, and opportunities. Both physicians that do not recruit or refer and those that do, indicate that they get little information about clinical trials. This is particularly interesting in the case of those physicians who do recruit or refer patients. Generally, these physicians indicate that it is up to them to take the initiative to identify clinical trials. The fact that willing physicians are having to go out of their way to refer patients suggests that there are opportunities and a need for better forms of communication between re- searchers who are recruiting patients for clinical trials and community physicians. Physicians indicate that they would like more information about active clinical trials. Physicians that do not refer/recruit, stated concerns about patients being placed on a placebo (rather than the study drug), the lack of patient access to the study drug after the study concludes, and that participation in a par- ticular study may not be in a patient’s best interest (e.g., of no direct health benefit). These physicians also ex- press ethical concerns such as appearing to have a finan- cial incentive or “bounty” for referring or recruiting pa- tients. They were particularly sensitive about the ap- pearance of exploiting minority patients. These kinds of concerns may help to explain why these physicians do not refer or recruit patients to clinical trials, especially commercially funded trials that may provide financial compensation for participant accrual. As suggested by Kim et al., physicians, researchers and their institutions need to inform patients about financial conflicts in the same way they inform them about human subjects con- cerns [27]. Both groups of physicians were insistent that resource limitations adversely affect their ability to refer or recruit patients to clinical trials. Resources to enhance staffing (e.g., hiring a study coordinator) were thought to be es- sential to recruiting patients. Fear of losing patients was thought to be more of a concern for specialists who were referring patients to trials by other specialists, than re- ferrals by primary care providers. Efforts to increase the proportion of community physicians who refer or recruit patients to clinical trials will need to provide physicians with additional resources and/or develop methods to enhance office and staff capabilities to refer or recruit patients. As expressed by participating physicians and Embi et al., clinical practice tools such as electronic medical record systems may be useful in addressing these concerns [28,29]. Limitations of our work include small samples of pa- tients and physicians that may not be representative of their respective populations. In our patient focus groups, for example, the majority of participants were women. A different group of participants may result in different  J. Nodora et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 742- 752 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 750 issues being raised. Additionally, focus group research does not involve independent observations as partici- pants influence one another within the context of the focus group. While this is an advantage of focus group research for exploring qualitative issues, it limits the generalizability of study findings. Also, analysis of focus group data involves a qualitative analysis of themes and, therefore, necessarily involves a subjective element de- spite attempts to be systematic and to eliminate bias (e.g., by using multiple coders). Strengths of our study pertain to the inclusion of both patient and physician provider focus groups in order to examine barriers and facilitators side-by-side. In addition, the Spanish language patient focus group protocols and questions were developed and implemented by trained and experienced bilingual and bicultural (Mexican-American) investigators and staff. This helps ensure linguistic and cultural accuracy of the study, as well as increased comfort and understanding, which in turn affects participant trust. Recent forecasts predict that demand for clinical trials participants will outstrip supply [30]. Improving the re- cruitment of minority populations is critical to address- ing the forecast shortage of clinical trials participants as well as ensuring the equitable distribution of the benefits and burdens of medical research. Currently only 11% of Arizona Medicaid (AHCCCS) primary care providers report that they recruit or refer patients to clinical trials (Appendix). With so few Medicaid serving physicians recruiting or referring patients to clinical trials, there are opportunities to engage more community physicians in recruitment and referral activities. Initiatives such as EDICT (Eliminating Disparities in Clinical Trials) con- ducted by the Baylor College of Medicine and the Inter- cultural Cancer Council (http://www.bcm.edu/edict/home. html), as well as those conducted by the Education Net- work to Advance Clinical Trials (ENACCT http://www. enacct.org/) provide ready-made resources for research- ers, health care providers, an most importantly, patients and community leaders. As suggested by Robinson and Trochim [31], interventions that address community and researcher interests equally can help increase clinical trials participation among Hispanics and other underrep- resented populations. 5. CONCLUSIONS Although Mexican-American Medicaid eligible patients and the providers who serve them identify a variety of barriers to participation in clinical trials, facilitators for both groups validate the importance placed on clinical research and their willingness to participate. Interven- tions that provide clear, culturally relevant (i.e., Mexi- can-American; primary providers serving Medicaid pa- tients) clinical trials information, that addresses basic barriers such as time constraints, patient-provider com- munication and trust, are likely to increase accrual and retention. 6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was supported by a grant from the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission. The authors also wish to acknowledge the Behavioral Research Corporation which provided invaluable technical assistance with the focus groups, and the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System leadership which provided assistance with the development of the study framework. REFERENCES [1] Applied Clinical Trials (2004) Subject recruitment by far biggest clinical trial concern. Applied Clinical Trials, http://www.actmagazine.com [2] Ford, J.G., Howerton, M.W., Lai, G.Y., Gary, T.L., Bolen, S., Gibbons, M.C., Tilburt, J., Baffi, C., Tanpitukpongse, T.P., Wilson, R.F., Powe, N.R. and Bass, E.B. (2008) Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: A systematic review. Cancer, 112(2), 228-242. [3] Institute of Medicine (1999) The Unequal Burden of Cancer: An Assessment of NIH Research and Programs for Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved. National Academic Press, Washington, D.C. [4] Kagawa-Singer, M. (2000) Improving the validity and generalizability of studies with underserved U.S. popula- tions expanding the research paradigm. Annals of Epide- miology, 10(8), 92-103. [5] U.S. department of Health and Human Services NIH Policy and Guidelines on The Inclusion of Women and Minorities as Subjects in Clinical Research–Amended (2001) http://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/women_min/ guidelines_amended_10_2001.htm [6] Ford, J.G., Howerton, M.W., Bolen, S., Gary, T.L., Lai, G.Y., Tilburt, J., Gibbons, M.C., Baffi, C., Wilson, R.F., Feuerstein, C.J., Tanpitukpongse, P., Powe, N.R. and Bass, E.B. (2005) Knowledge and access to information on recruitment of underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment, 1-11. [7] Adams-Campbell, L.L., Ahaghotu, C., Gaskins, M., Daw- kins, F.W., Smoot, D., Polk, O.D., Gooding, R. and DeWitty, R.L. (2004) Enrollment of African Americans onto clinical treatment trials: Study design barriers. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 22(4), 730-734. [8] Sateren, W.B., Trimble, E.L., Abrams, J., Brawley, O., Breen, N., Ford, L., McCabe, M., Kaplan, R., Smith, M., Ungerleider, R. and Christian, M.C. (2002) How sociode- mographics, presence of oncology specialists, and hospi- tal cancer programs affect accrual to cancer treatment tri- als. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 20(8), 2109-2117. [9] Comis, R.L.A.C., Stovall, E., Krebs, L., Risher, P. and Taylor, H. (2000) A quantitative survey of public atti-  J. Nodora et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 742- 752 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 751 751 tudes towards cancer clinical trials. Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 19, 1728-1733. [10] Ramirez, A.G., Wildes, K., Talavera, G., Napoles-Spri- nger, A., Gallion, K. and Perez-Stable, E.J. (2008) Clinical trials attitudes and practices of Latino physicians. Con- temporary Clinical Trials, 29(4), 482-492. [11] Howerton, M.W., Gibbons, M.C., Baffi, C.R., Gary, T.L., Lai, G.Y., Bolen, S., Tilburt, J., Tanpitukpongse, T.P., Wil- son, R.F., Powe, N.R., Bass, E.B. and Ford, J.G. (2007) Provider roles in the recruitment of underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials. Cancer, 109(3), 465- 476. [12] Office of Management and Budget (1995) Standards for Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. [13] U.S. Census Bureau (2004) U.S. Interim Projections by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin. [14] Pew Hispanic Center (2009) Statistical Portrait of His- panics in the United States, 2007, Table 5 Detailed His- panic Origin: 2007. [15] Pew Hispanic Center (2009) Mexican Immigrants in the United States, 2008. [16] Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (2006) U.S. Hispanic Population: 2006. [17] Livingston, G., Cohn, M.S., D’Vera, (2008) Hispanics and Health Care in the United States: Access, Informa- tion and Knowledge. Pew Hispanic Center and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. [18] Markman, M., Petersen, J. and Montgomery, R. (2008) An examination of the influence of patient race and eth- nicity on expressed interest in learning about cancer clinical trials. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology, 134(1), 115-118. [19] Wendler, D., Kington, R., Madans, J., Van Wye, G., Christ-Schmidt, H., Pratt, L.A., Brawley, O.W., Gross, C.P. and Emanuel, E. (2006) Are racial and ethnic mi- norities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Medicine, 3(2), e19. [20] Washington, H. (2007) Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. Doubleday, New york. [21] Advani, A.S., Atkeson, B., Brown, C.L., Peterson, B.L., Fish, L., Johnson, J.L., Gockerman, J.P. and Gautier, M. (2003) Barriers to the participation of African-American patients with cancer in clinical trials: A pilot study. Can- cer, 97(6), 1499-1506. [22] Corbie-Smith, G., Thomas, S.B., Williams, M.V. and Moody-Ayers, S. (1999) Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 14(9), 537-546. [23] Freimuth, V.S., Quinn, S.C., Thomas, S.B., Cole, G., Zook, E. and Duncan, T. (2001) African Americans’ views on research and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Social Sci- ence & Medicine, 52(5), 797-808. [24] Mouton, C.P., Harris, S., Rovi, S., Solorzano, P. and Johnson, M.S. (1997) Barriers to black women’s participa- tion in cancer clinical trials. Journal of the National Medical Associati on, 89(11), 721-727. [25] Jerant, A., Arellanes, R. and Franks, P. (2008) Health status among US Hispanics: Ethnic variation, nativity, and language moderation. Medical Care, 46(7), 709-717. [26] DeNavas-Walt, C. and Bernadete, P. (2008) Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2007, Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. [27] Kim, S.Y., Millard, R.W., Nisbet, P., Cox, C. and Caine, E.D. (2004) Potential research participants’ views regard- ing researcher and institutional financial conflicts of in- terest. Journal of Medical Ethics, 30(1), 73-79. [28] Embi, P.J., Jain, A., Clark, J., Bizjack, S., Hornung, R. and Harris, C.M. (2005) Effect of a clinical trial alert system on physician participation in trial recruitment. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165(9), 2272-2277. [29] Embi, P.J., Jain, A. and Harris, C.M. (2008) Physicians’ perceptions of an electronic health record-based clinical trial alert approach to subject recruitment: A survey. BMC Medical Informatics & Decision Making, 8(13), 1-8. [30] Tam, J.T.H.R., Gura, D., Paraghamian, A., Thomas, H. and Lichtman, S. (2006) Has demand outpaces supply for clinical trial participants? ASCO Annual Meeting Pro- ceedings Part I, 24 (18S), 6016. [31] Robinson, J.M. and Trochim, W.M. (2007) An examina- tion of community members’, researchers’ and health professsionals’ perceptions of barriers to minority par- ticipation in medical research: An application of concept mapping. Ethn Health, 12(5), 521-539.  J. Nodora et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 742- 752 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 752 APPENDIX AHCCCS Provider Survey In collaboration with our research team, the state Medi- caid Agency (Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System-AHCCCS) agreed to include a question on its annual provider survey about primary care provider (PCP) participation in recruiting/referring patients to clinical trials. The item asked PCP respondents: In the past three (3) years have you recruited or referred clients to clinical research trials? The target population for the AHCCCS survey included a total of 7,656 providers, consisting of 2,633 PCPs, 2,999 specialists, 729 dentists, and 1,295 office managers. The survey was conducted by mail, web, and telephone from November through May 2006. A total sample of 1,764 surveys was completed, including 495 PCPs. The overall response rate was 52% and the response rate among PCPs was 51%. The table below summarizes the results of the PCP survey data by cross- tabulating responses of the clinical trials item with available data about provider characteristics (note: pro- vider sex, race, and ethnicity data are not available from the survey). These data begin to provide a profile of the extent to which Medicaid physicians are involved in re- cruiting/referring patients to clinical trials. Based on this survey we know that only 11% of Medicaid providers currently refer patients to research studies. The only other statistically significant difference in participation rates relates to practice area; physicians in Maricopa and Pima (large metropolitan) counties are more likely to recruit or refer patients to clinical trials than in rural counties. Table 1*. AHCCCS provider survey results. # % AHCCCS PCP Respondents 495 51% Refer or Recruit Patients to Clinical Trials No 405 89% Yes 52 11% Refer/Recruit by Provider Type Family Practice 17 12% General Practice 2 9% Internal Medicine 14 11% Pediatrician 19 12% Refer/Recruit by Practice Area* Maricopa/Pima 45 14% Other Counties 7 5% Refer/Recruit by Health Plan** APIPA 42 12% Care 1st 13 12% Community Connection PHP 17 10% Health Choice AZ 27 11% Maricopa MC 10 13% Mercy Care Plan 42 13% Pima Health System 17 18% University Family Care 8 21% *Chi square = 6.5852, df = 1, p ≤ .01 **Since each physician can accept more than one health plan, this is not an unduplicated count

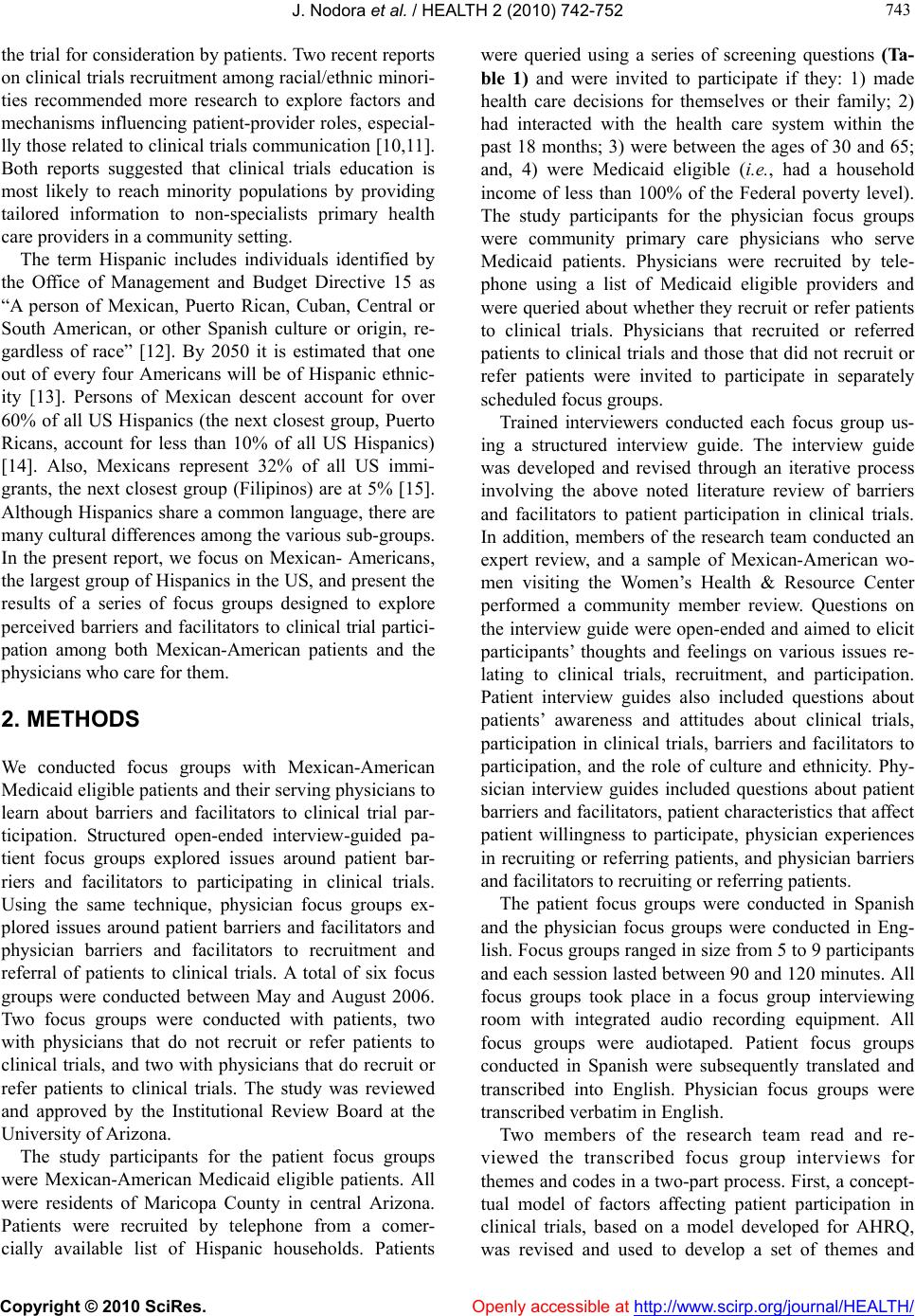

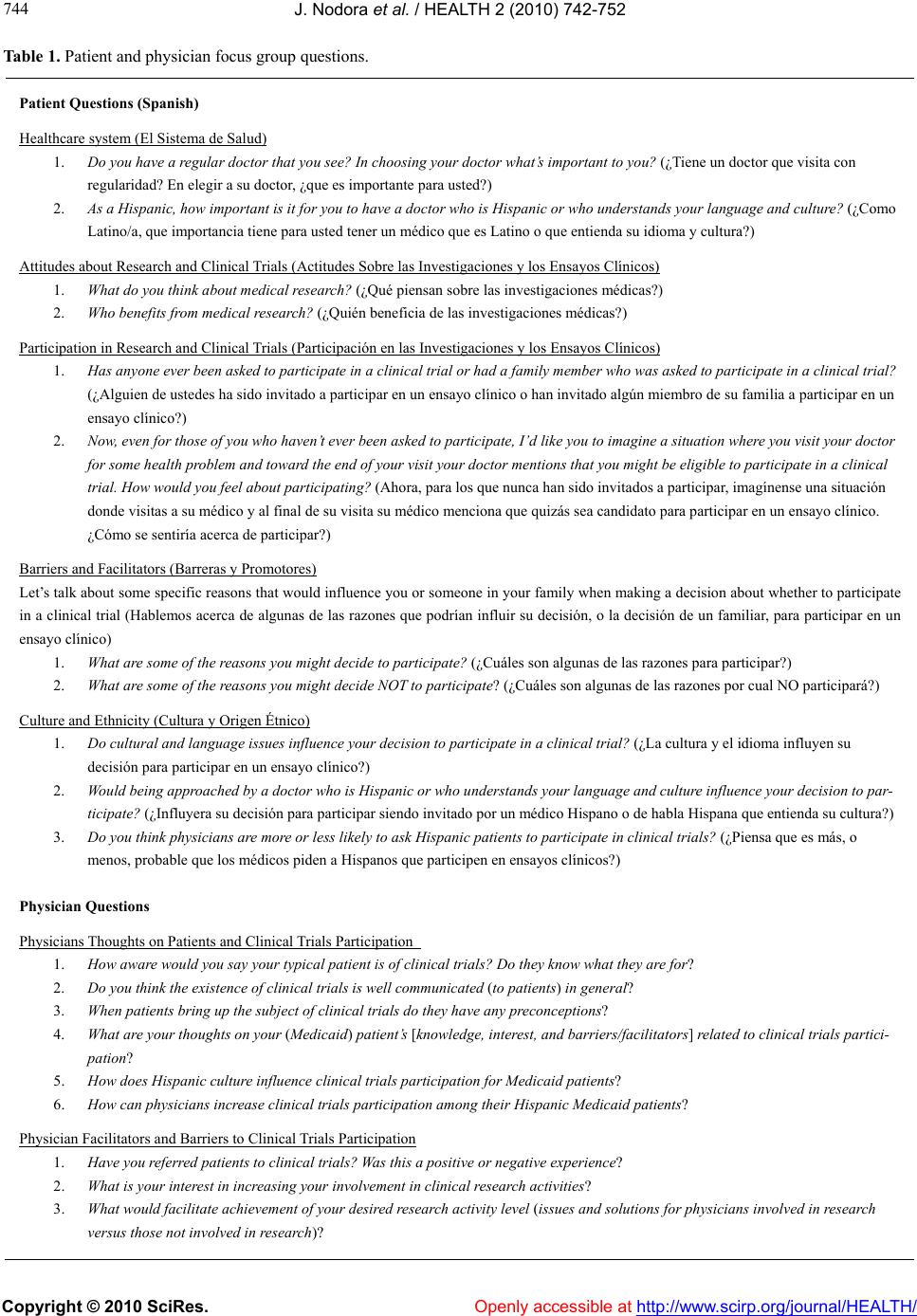

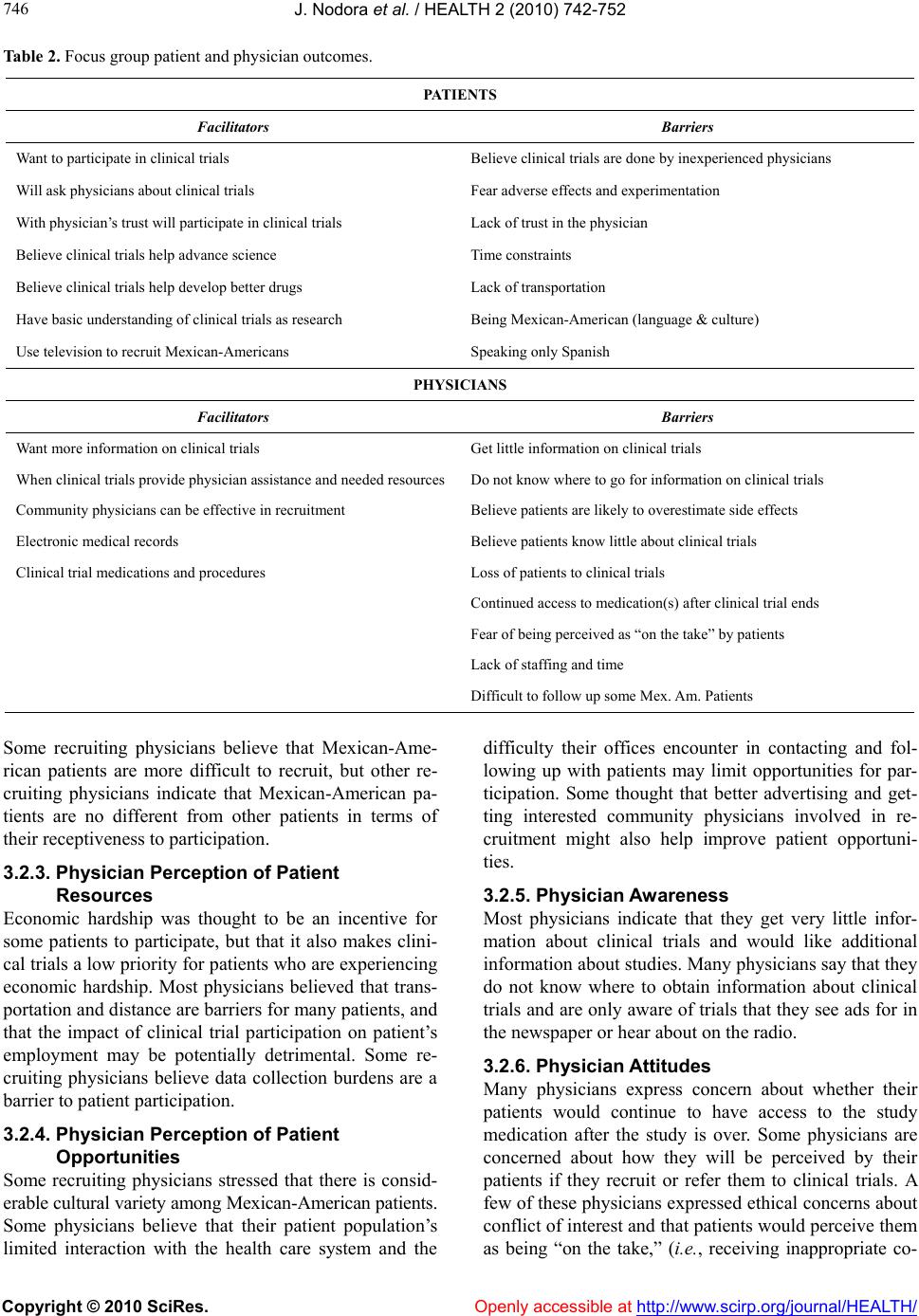

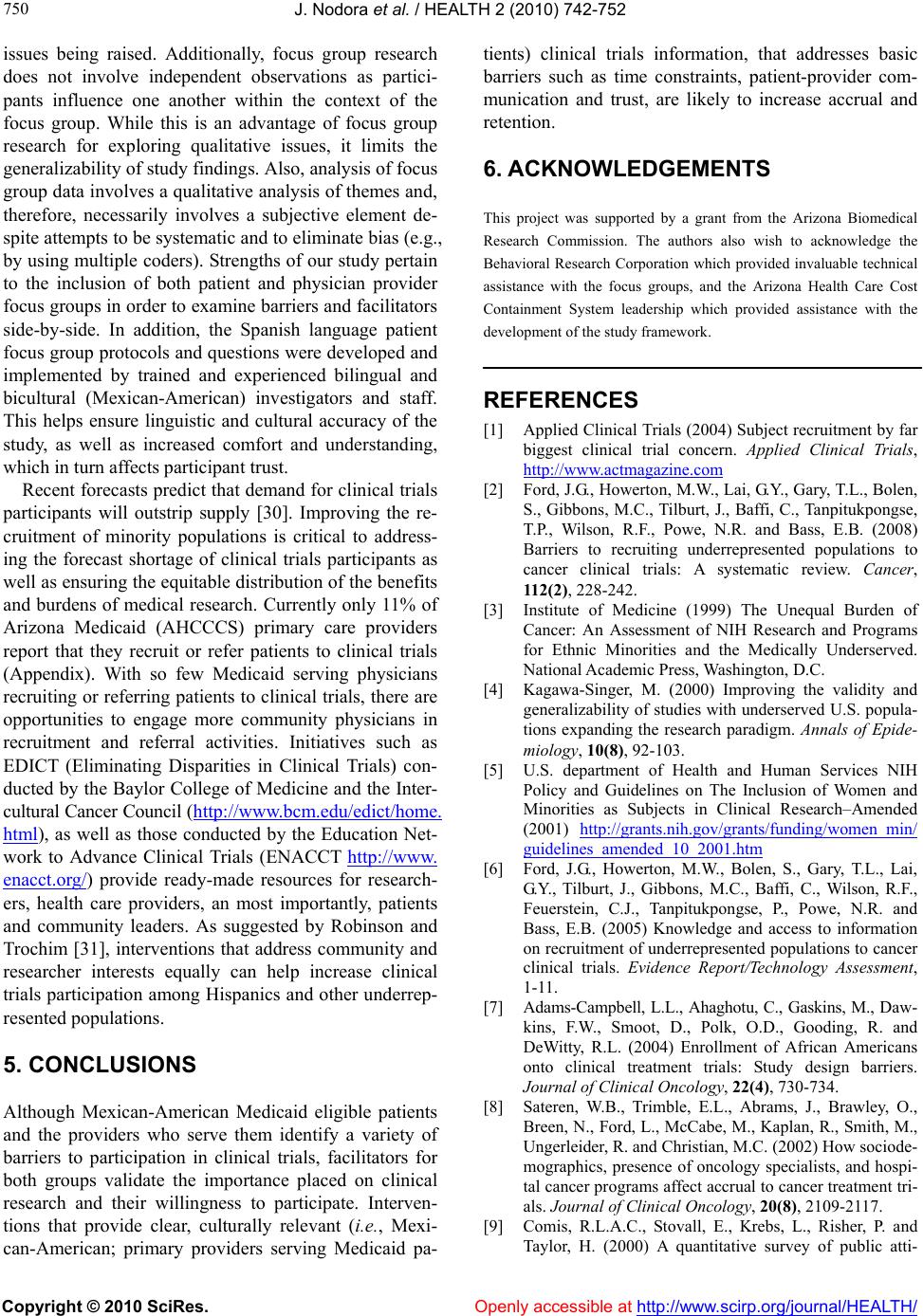

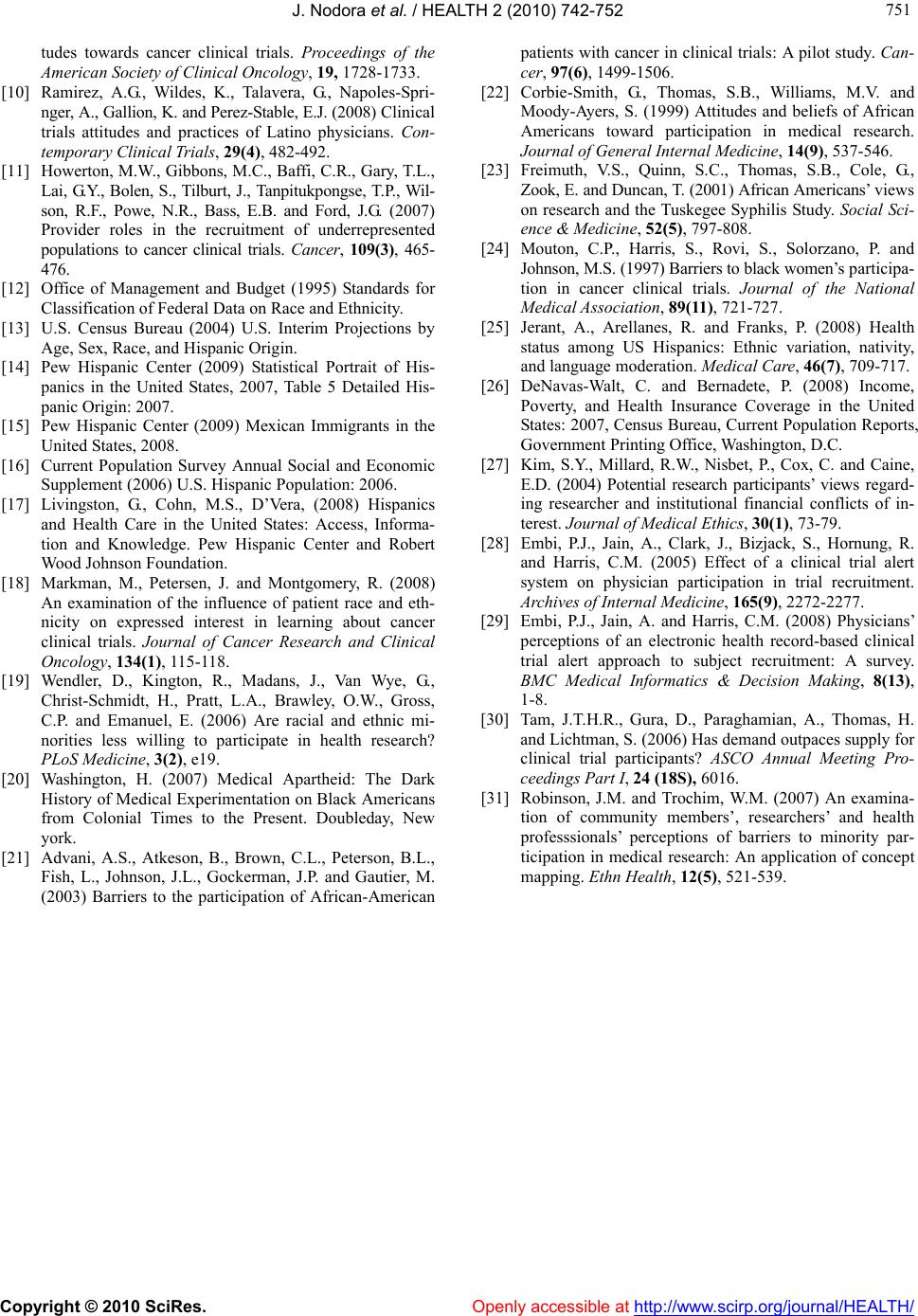

|