World Journal of AIDS, 2012, 2, 183-193 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/wja.2012.23024 Published Online September 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/wja) 183 Prevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Risk Behavior, and Recent Substance Use in a Sample of Urban Drug Users: Findings by Race and Sex Rebecca C. Trenz1*, Lauren R. Pacek2, Michael Scherer2, Paul T. Harrell2, Julia Zur2, William W. Latimer3 1Department of Psychology, School of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Mercy College, Dobbs Ferry, New York, USA; 2Department of Mental Health, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA; 3Department of Clinical and Health Psychology, College of Public Health and Health Professions, University of Florida, Gainesville, USA. Email: *rtrenz@mercy.edu Received July 5th, 2012; revised August 5th, 2012; accepted August 12th, 2012 ABSTRACT The aim of the current study was to examine the prevalence of HIV, past six-month illicit d rug use, and risk behaviors among a population of heavy drug users living in an urban setting. Although many studies investigate substance use, sex-risk behavior, and HIV by race and gender, no studies have examined these variables simultaneously. The current study seeks to fill this gap in the literature by exploring HIV prevalence among a predominantly heterosexual sample of recent substance users by injection drug use (IDU) status, race, and sex. Baseline data from the Baltimore site of the NEURO-HIV epidemiologic study was used in this study. This study examines neuropsychological and social-behav- ioral risk factors of HIV, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C among both injection and non-injection drug users. Descriptive statistics and chi-square statistics were used in data analyses. Blood and urine samples were obtained to test for the presence of recent drug use, viral hepatitis, HIV, and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Findings pre- sented here have several important implications for HIV prevention and care among substance users. Intervention pro- grams that incorporate substan ce use treatment in addition to HIV education, particularly with respect to substance use and sex risk behavior are imperative. Keywords: HIV Prevalence; Injection Drug Use; Non-Injection Drug Use; Sex Risk Behavior 1. Introduction Traditionally, early HIV prevalence research in the United States has focused on two high-risk categories: injection drug users (IDUs) [1-7] and men who have sex with men (MSM) [8-13]. Over one million cases of AIDS have been documented in the United States since the beginning of the epidemic with the majority of these cases occurring within major metropolitan areas [14]. In Maryland, HIV is the fourth leading cause of death among Blacks [15] and not unlike many other cities in the United States, Baltimore has a significant prevalence of HIV. As of 2006 in Baltimore City, Maryland , 2454.7 individuals per 100,000 were living with HIV/AIDS with an annual incidence of approximately 37.7 cases per 100,000, ranking the city second among metropolitan areas in the United States. [16] In addition to high prevalence of HIV in Baltimore, within Maryland, an estimated 7% - 19% of residents reported illicit drug use in the past month and past year alcohol or illicit drug use, dependence, or abuse [17]. Moreover, substance use has a strong link to HIV/AIDS in the United States. It is estimated that approximately 64% of individuals diagnosed with HIV/AIDS have used a non-injection illicit drug and 17% have used an injec- tion drug in their lifetime [14]. In fact, landmark studies of HIV and substance use specifically examined injection drug use (IDU) with a focus on HIV transmission via needle sharing [2-4]. Additionally, other early studies suggested that sexual transmission among IDUs also ex- isted, but was overshadowed by injection risks [5-7]. Currently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that about 13% of new HIV-positive di- agnoses are attributable to IDU [18]. Furthermore, IDUs represent a high-risk group for HIV transmission that may bridge the gap to lower-risk populations, such as non-injec- tion drug users (NIDUs) [19-20], through sex-risk behaviors [22]. As a resu lt, research has b egun to focus on the preva- lence of HIV infection among substance users generally, *Corresponding a uthor. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA  Prevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Risk Behavior, and Recent Substance Use in a Sample of Urban Drug Users: Findings by Race and Sex 184 expanding the literature to include NIDUs [21] with a focus on sexual transmission risk [20,23-25]. Although the current literature is ex panding to include non-injection drug use (NIDU) and risk behaviors asso- ciated with substance use in general, few studies have included IDU status, race, and sex along with HIV prevalence in the same study. In addition HIV prevalence information among NIDUs is often gathered from re- search conducted on populations of substance abusing HIV-positive individuals either seeking treatment or cur- rently enrolled in treatment programs. The aim of the current study was to examine the p r ev a len ce of H IV , p a s t six-month illicit drug use, and risk behaviors among a population of heavy drug users living in an urban setting. As HIV prevalence research has focused on the afore- mentioned categories, fewer studies have investigated the occurrence of HIV among primarily heterosexual, sub- stance using samples that include both Black and White injection and non-injection drug users. The current study seeks to fill this gap in the literature by exploring HIV prevalence among a predominately heterosexual sample of recent substance users by IDU status, race, and sex. 2. Method Data for this study were obtained from the baseline as- sessment of the NEURO-HIV Epidemiologic Study. This study was designed to examine neuropsychological and social-behavioral risk factors of HIV, hepatitis A, hepati- tis B, and hepatitis C among both injection and non-in- jection drug users in Baltimore, Maryland. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in 2001 and has received annual renewals. The design of this study is cross-section al. In ord er to b e eligible fo r the parent study, participants had to be between the ages of 15 and 50 and had to report use of non-injection and/or injection drugs in the past 6 months. Participants who met these criteria were selected for the current research. Recruitment strategies for participation included adver- tisements in local papers, street outreach, and referrals from local service agencies. Participants were remuner- ated $45 for the baseline assessment. Participants provided written informed consent and completed a face-to-face HIV-risk behavior interview. In addition, participants completed a battery of neuropsy- chological tests that measured executive functioning and estimated general intelligence. Blood and urine samples were also collected at the baseline assessment. Blood was drawn by a phlebo tomist and tested for HIV, hepatitis A, B, and C. Urine samples were tested for the presence of drugs including: opiates, cocaine, cannabinoids, metham- phetamine, methadone, PCP, barbiturates, benzodiazepi- nes, tricyclic antidepressants, MDMA, and oxycodone. Participants were subsequently notified of their HIV status and were referred to drug treatment and social ser- vices for counseling with respect to their blood and urine analysis results. 2.1. Study Participants Participants for the research presented here were drawn from the metropolitan region of Baltimore, Maryland. Residents of this region have a median age of 34.40 years and are primarily African American (63.7%), have a high school or greater education (76.9%), and have never been married (males 54.5%; females 49.2%) [26]. Participants included in the current study (N = 578) identified as Black (48.1%) or White (57.9%) with a mean age of 31.57 (SD = 7.76). The majority of participants were male (56.6%) and single (70.1%) with a high school education or greater (55.0%). Approximately 19.0% re- ported having experienced homelessness and 37.8% re- ported receiving public assistance in the 6 months prior to the study assessment. In addition, 75.0% of partici- pants reported having been either in jail or a correctional facility in their lifetime. Table 1 shows a complete sum- mary of characteristics of the study sample. 2.2. Measures 2.2.1. HIV-Risk Behavior Interview The HIV-risk behavior interview is a detailed behavioral assessment of drug use and sexual practices. This as- sessment was adapted from a similar interview used in the REACH [19] and ALIVE [27] studies. Questions addressed demographic, educational, medical, and neu- rodevelopment variables along with a detailed assessment of lifetime and recent drug use and sexual practices includ- ing a history of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) [28]. 2.2.2. C asual Sex Be havior Participants were asked two questions assessing casual sex and risk: “Have you ever had a casual partner?” and “When you had sex with a casual partner, what percent of the time did you use a condom?” A casual partner is defined as having sex with someone whom the partici- pant knew for less than three months. A dichotomous variable was created to identify participants who ever had casual sex (coded 1) versus those who did not (coded 0). Consistent condom use with a causal partner, or using a condom 100% of the time with a casual partner was coded 1 and inconsistent condom use with casual partner (0% - 99%) was coded 0. Studies investigating sex risk behavior have utilized this type of co ding method to cate- gorize consistent versus inconsistent condom use [28]. 2.2.3. Se x Trade Participants were asked if they had ever paid for sex with Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA  Prevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Risk Behavior, and Recent Substance Use in a Sample of Urban Drug Users: Findings by Race and Sex Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA 185 Table 1. Characteristics of the study sample (N = 578). Frequency or Mean % or SD Age (range = 15 - 50 years) 31.57 7.76 Race/ethnicity Black 278 48.1 White 300 57.9 Sex Male 327 56.6 Female 251 43.4 Education Less than high school graduate 260 36.5 High school graduate or equivalent 227 39.3 Some college or technical training 84 14.5 College graduate 7 1.2 Marital Status Single 404 70.1 Separated 47 8.2 Divorced 57 9.9 Widowed 11 1.9 Married 57 9.9 Homeless past 6 months 107 18.9 Received public assistance past 6 months 218 37.8 Incarcerati on history Never in jail 143 25.0 Jail 262 45.9 Correctional facility 166 29.1 Sexual history Opposite sex partners only 556 97.4 Ever had casual sex 401 70.0 Ever trade sex 190 32.9 Casual partners 28.43 167.69 HIV-positive 46 8.0 Any STD 169 30.2 Lifetime i nj e ct i on drug use 370 64.0 Recent substance usea Cigarettes 517 89.4 Alcohol 421 72.8 Inject any drug 314 54.3 Marijuana-smoking 307 53.2 Heroin-injection 291 50.3 Crack Cocaine 273 47.3 Heroin-nasal 259 44.9 Heroin and cocaine together (“Speedball”): injection 184 31.9 Cocaine-injection 182 31.5 “Downers” (barbiturates, tranquilizers, sedatives, etc.) 130 22.5 Cocaine-nasal 121 21.0 Street methadone 106 18.3 Note: Column totals do not always add up to the sample total due to missing data (<2%); aPast six months.  Prevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Risk Behavior, and Recent Substance Use in a Sample of Urban Drug Users: Findings by Race and Sex 186 drugs or money or sold sex for drugs or money. These two variables were collapsed into one sex trade variable. Participants who resp onded “yes” to either on e or both of these questions were coded 1, while those who responded no to both were coded 0. 2.2.4. Se xually T r a ns mitted D iseases Participants were asked if they had ever been told by a health professional that they had a STD including gon- orrhea, syphilis, chlamydia, genital herpes, gen ital warts, or trichomoniasis. A dichotomous variable was created to identify any participants with (coded as 1) or without (coded as 0 ) a h istory o f o n e of these s ix STDs. 2.2.5. Recent Substance Use Participants were asked if they had used any of the fol- lowing substances in the six months prior to the assess- ment: cigarettes, alcoho l, any drug inj ection , marijuan a— smoking, heroin—injection, crack cocaine, heroin—nasal, heroin and cocaine together (“Speedball”), cocaine— injection, “downers” (barbiturates, tranquilizers, seda- tives, etc.), cocaine—nasal, and street methadone. “Yes” responses were coded 1, while “no” responses were coded 0 f or each substance. 2.2.6. Substance Use before/during Sex Participants were asked three questions each for lifetime substance use before/during casual sex: “When you had sex with a casual partner, what percent of the time did you use alcohol before /during sex?”; “When you had sex with a casual partner, what percent of the time did you use non-injection drugs before/during sex?”; and “When you had sex with a casual partner, what percent of the time did you use injection drugs before/during sex?” Those participants who responded 0% to any of these items were coded as 0. Those who indicated any per- centage greater than 0 were coded 1. This same set of questions was asked substituting “steady partner” for “casual partner.” A steady partner is defined as a rela- tionship greater than 3 months. For both casual and steady sex, the above three questions were collapsed in to one variable, any drug use before/during sex. In both instances, any drug use befor e/ duri n g sex w a s code d 1. 2.3. Data Analysis Descriptive statistics were used to calculate frequencies, means, and percentages for each variable of interest. Race/sex groups (White male, Black male, White female, Black female) were created to conduct ANOVAs and chi-square statistics (χ2) for demographic, sex-risk be- havior, recent substance use, and substance use be- fore/during sex variables. Tukey HSD post hoc compari- sons were used for ANOVAs. The frequency of HIV- positive cases was calculated for the entire study sample. HIV-positive cases were then further stratified by IDU status, race, and sex. In the analysis of HIV-positive cases by IDU status, race, and sex, chi-square statistics were calculated where possible; in other words, the as- sumptions that 80% or more of the cells have expected frequencies of five or more and that no cells have an ex- pected count of 0 must have been met [29]. In situations where a 2 by 2 table was evaluated, the Yates Correction for Continuity was used as the test for significance [29]. All data analysis was performed using PASW Statistics 18 [30]. 3. Results 3.1. Participant Characteristics Table 1 displays the prevalence of baseline characteris- tics including sexual history, and recent substance use. The majority of participants reported having only oppo- site sex sexual partners (97.4%) in their lifetime. Seventy percent of participants reported having had casual sex in their lifetime with a mean of 28.43 (SD = 167.69) casual partners. The prevalence of lifetime sex trade in study participants was 32.9%. Overall, HIV seroprevalence was 8.0% (46 HIV-positive cases) and just under one- third (30.2%) reported having been told they had any STD. Sixty-four percent of participants reported ever injecting any drug in their lifetime. Overall, there was a high prevalence of recent sub- stance use in the study sample. Greater than half of the sample reported using cigarettes (89.4%), alcohol (72 .8 %), injecting any drug (54.3%), smoking marijuana (53.2%), and injecting heroin (50.3%) in the six months prior to the assessment. Crack cocaine (47.3%), nasal heroin (44.9%), “Speedball” (31.9%), and injecting cocaine (31.5%) had high recent prevalence of use. Although less prevalent, “Downers” (22.5%), nasal cocaine (21.0%), and street methadone (18.3%) are included as representa- tive of recent substance use. 3.2. Associations of Participant Characteristics by Race and Sex Table 2 displays a full summary of associations of demographics, sex-risk behaviors, recent substance use, and substance use before/during casual and steady sex by race/sex group. 3.2.1. Baseline Characteristics One-way ANOVA r evealed significan t differences in age by race/sex group, F(3,577) = 31.68, p < 0.001. As re- vealed by post-hoc analysis, White males were signifi- cantly younger (M = 28.50, = 7.42) than both Black SD Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA  Prevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Risk Behavior, and Recent Substance Use in a Sample of Urban Drug Users: Findings by Race and Sex 187 Table 2. Association of baseline participant characteristics in 578 substance users Note: aPas t s ix months; bLifetime. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA  Prevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Risk Behavior, and Recent Substance Use in a Sample of Urban Drug Users: Findings by Race and Sex 188 males (M = 35.06, SD = 6.72), p < 0.001, and Black fe- males (M = 33.70, SD = 7.22), p < 0.001. Similarly White females were significantly younger (M = 28.74, SD = 7.43) than Black males, p < 0.001, and Black fe- males, p < 0.001. Chi-square statistics revealed signifi- cant differences by group on high school education/GED, p < 0.001; single status, p = 0.002; spending time in jail, p < 0.001; receiving public assistance, p < 0.001; home- lessness, p < 0.001; having ever injected any drug, p < 0.001; testing pos itive for opioids, p < 0.001; being HIV- positive, p < 0.001; and having any STD, p < 0.001. 3.2.2. Sex-Risk Beh avior Chi-square analyses revealed significant differences by group on ever engaging in casual sex, p < 0.001, and having traded sex, p < 0.001. More than three-fourths of both White (83.4%) and Black (79.7%) males reported casual sex in their lifetime. The highest percentage of sex trade involvement was found among Black males (43.6%) and the lowest was among White males (21.4%). One- way ANOVA revealed significant differences in number of lifetime casual sex partners by group, F(3,395) = 9.40, p < 0.001. Post ho c analysis showed that both White and Black males had significantly more casual partners (M = 24.65, SD = 34.61; M = 28.86, SD = 47.15, respectively) than Black females (M = 5.94, SD = 8.64), p < 0.001. Black males also had significantly more casual partners than White females (M = 11.56, SD = 18.88), p = 0.017. There was no significant difference by group on consis- tent condom use with casual partners, p = 0.187. Consis- tent condom use across groups was low with Black fe- males reporting the highest percentage (37.6%) of con- sistent condom use with casual partners. 3.2.3. Recent Substance Use Chi-square analyses revealed significant differences by group on recent substance use, including: heroin—in- jection, p < 0.001; heroin—nasal, p < 0.001; cocaine— injection, p < 0.001; cocaine—nasal, p = 0.007; “speed- ball” —injection, p < 0.001; and “down ers”, p < 0.00 1. A large percentage of White males (75.9%) and White fe- males (70.3%) endorsed having injected heroin in the past six months compared to Black males (32.1%) and Black females (25.0%). Conversely, nasal heroin use for Black males (59.3%) and Black females (46.9%) exceeded that for White males (33.7%) and White females (42.2%). No significant differences were found by group on crack co- caine, p = 0.321, or street methadone use, p = 0.085. 3.2.4. Substance Use before/during Casual Sex Chi-square analyses revealed significant differences by group on alcohol use, p = 0.019, non-injection drug use, p < 0.001, injection drug use, p = 0.001, and any drug use, p < 0.016, before/during casual sex. The highest rates of alcohol use before/during casual sex were found among White males (68.4%) and Black males (68.8%). High rates of non-injection drug use before/during sex were also found among White males (60.0%) and Black males (74.3%). The use of any drug before/during sex was high across groups, with the highest prevalence among Black males (85.3%). 3.2.5. Substance Use before/during Steady Sex Chi-square analyses revealed significant differences by group on alcohol use, p = 0.010, non-injection drug use, p = 0.013, and injection drug use, p < 0.001, be- fore/during steady sex. Substance use before/during sex was high across groups with more than half of partici- pants in each group reporting alcohol use and non-injec- tion drug use in these situations. Injection drug use be- fore/during sex was highest among White females (57.5%) and lowest among Black females (23.9%). No significant differences were found between groups on any drug use before/during sex, however rates of use in this situation were high across all gro ups with prevalen ce exceeding 75% within each group. 3.3. HIV Prevalence by IDU Status, Race, and Sex A summary of HIV-positive cases can be found in Fig- ure 1. Overall, of the 578 participants screened in the current study 7.96% were HIV-positive. There was no significant difference in HIV-positive cases by IDU status, 2 = 0.00, p = 1.00. The prevalence of HIV-posi- tive cases among injectors (7.96%) and non-injectors (7.95%) was similar. Among injectors, Black injectors more likely to be HIV-positive (16.83%) than White in- jectors (3.76%), 2 = 14.25, p < 0.001. Among Black injectors, there was no significant difference found by sex, where prevalence of HIV-positive cases was 19 .23% for males and 14.29% for females, 2 = 0.16, p = 0.691. Among non-injectors, there was a significant difference found by race, where Black non-injectors were more likely to be HIV-positive (10.55%) than Whites (0%) in this group, 2 = 6.08, p = 0.014. No significant difference in sex was found among Black non-injectors, 2 = 0.01, p = 0.921. Among Black non-injectors, the prevalence of HIV-positive cases for males was 11.36% and 9.91% fo r females. Chi-square analysis was not conducted among White injectors and non-injectors due to violations of lowest expected frequencies. Two additional analyses were conducted across inject- tion drug use status comparing Black male injectors to Black male non-injectors and Black female injectors to Black female non-injectors. First, there was no signifi- cant difference found between Black males by IDU Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA  Prevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Risk Behavior, and Recent Substance Use in a Sample of Urban Drug Users: Findings by Race and Sex 189 Figure 1. Flow chart illustrating the prevalence of HIV+ status in the study sample. Ellipses represent injection drug use status, rectangles represent race/ethnicity, and circles represent sex. Chi-squares were conducted in cases where at least 80% of cells have expected frequencies of 5 or more. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA  Prevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Risk Behavior, and Recent Substance Use in a Sample of Urban Drug Users: Findings by Race and Sex 190 status, 2 = 1.07, p = 0.300. The prevalence of HIV- positive cases for Black male injectors was 19.23% compared to 11.36% among Black male non-injectors. Second, there was no significant difference found be- tween Black females by IDU status, where 14.29% of Black female injectors were HIV-positive compared to 9.91% of Black female non-injectors, 2 = 0.29, p = 0.592. 4. Discussion The purpose of the present study was to evaluate demo- graphic characteristics, sex-risk behavior, substance use, and prevalence of HIV by IDU status, race, and sex among a population of primarily heterosexual, recent substance users. There are several important findings that should be discussed. First, sex-risk behavior across race/sex groups is high with low levels of consistent condom use with casual partners. Second, substance use before/during both casual and steady sex is high across groups. These findings are particularly pertinent since it is known that alcohol and drug use impairs judgment and decision making that could lead to sex-risk behaviors such as inconsistent condom use, contributing to HIV transmission and infection. This finding is acutely im- portant for Baltimore, given that of the HIV cases re- ported by the Maryland Department of Health and Men- tal Hygiene in Baltimore City, the majority are hetero- sexuals (47%) followed by injection drug users (IDUs; 32%) and men who have sex with men (MSM; 16%) [16]. In addition, this study supports recent findings that prevalence of HIV is similar when broken down by in- jection drug use status, yet within these two categories HIV prevalence is greater for both Black males and fe- males compared to White males and females [31]. More- over, these findings are consistent with national estimates of race disparities in HIV identifying Blacks with the highest prevalence of new HIV/AIDS diagnoses (50.5%), while representing only 13% of the population [32]. The disparities in HIV infection by race are well-documented and there are several proposed theoretical explanations for this finding. One prominent explanation is that HIV transmission among NIDUs likely occurs from high-risk sexual behaviors [20,31]. The findings in the current study provide some support for this theory in that sex trade is more prominent among African Americans and suggests that for Black males and females the prevalence of HIV is similarly attributable to risky injection prac- tices among IDUs and risky sexual behavior among NIDUs. Although race itself is not a risk factor for becoming infected with HIV, there are many factors that may con- tribute to the disparities in HIV infection explored in the literature. In particular, a large number of studies have explored social network structure as a potential source of these disparities, particularly among IDUs [23,33,34]. However, recently research has begun to focus on high- risk sexual behaviors of heterosexual substance users. For example, in a study of primarily African Americans in a high HIV-risk community, drug users were more likely than non-drug users to have multiple sex partners, exchange sex for money or drugs, have a sexual rela- tionship with someone they knew had other sex partners, and use drugs or alcohol at their last sexual experience compared to non-drug users [20]. In addition, in a sample of African American NIDUs, having personal networks with a high degree of substance use activities and re- ceiving financial support in the form of housing assis- tance was associated with high-risk sexual behaviors including having multiple partners and having sex with- out a condom [24]. Although no significan t differences were found by sex with regard to HIV prevalence in the current study, fe- males may be at greater risk for HIV infection among this group of substance users. In fact, research has sug- gested that male to female transmission is significantly more effective than female to male transmission, thus putting females at greater risk for infection. Specifically, the estimated transmission rate in male partners of in- fected women ranges from 1% [35] to 12%, [36] while the estimated transmission rate of female partners of in- fected men is approximately 20% [35,36]. In other words, male to female HIV transmission is approximately two times as efficient than female to male transmission. In a longitudinal study of unsafe sex among HIV infected adults, sex-risk behavior did not increase among women with steady partners but, the frequency of sex-risk be- havior doubled among heterosexual men with steady partners over the study period [37]. Further, female drug users may be especially vulnerable to th e transmission of HIV through sex, as their sexual networks tend to be lar- ger, have more networks that provide financial support [25], and have more overlap between members than men [38,39]. In addition, among African American female crack users, engaging in sex trade [40] and having social networks that use heroin or cocaine is associated with HIV infection [25]. This is particularly concerning given that nationally, Black females have the greatest propor- tion of new HIV/AIDS cases by sex; 67.2% [41]. Risk factors for heterosexual transmission of HIV in- clude inconsistent condom use, sexual contact during menses, anal sex, and age of female partner [42]. One explanation for HIV transmission via sexual routes among NIDUs is that intoxication through the use of various substances may lead to a lack of attention to en- gaging in the practice of safe sex or a propensity toward engaging in high-risk sex [19,43]. In a study of serodis- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA  Prevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Risk Behavior, and Recent Substance Use in a Sample of Urban Drug Users: Findings by Race and Sex 191 cordant couples, those who reported recent substance use were over two times as likely to have had unprotected sexual episodes than couples where both partners did not report recent substance use. In addition, drug dependent partners were three and half times more likely to engage in recent unprotected sexual episodes than in couples where neither partner was drug dependent [44]. Taken together, these studies show that substance use in general increases the likelihood of sex-risk behaviors, thereby allowing for the possibility of HIV and other STD trans- mission through unprotected sex. Interventions that focus on high-risk sexual behaviors associated with drug use are needed to reduce the risk of HIV transmission among vulnerabl e po p ul at ions [21,45 ] . Despite the contributions of the current study, there are limitations in the current research that are inherent in a cross-sectional design. Namely, while cross-sectional research is a vital tool in identifying areas for more in- depth study, the ability to make causal inferences must be reserved for experimental studies. Further, these find- ings possess limited generalizability to larger, non-illicit drug using populations in non-urban areas. Finally, this study uses retrospective data where there is reliance on the self-report of drug use history, however, self-report of drug use has been demonstrated as a reliable and valid method of describing drug use [46]. In this study urinaly- sis data is consistent with self-report findings. 5. Conclusion Notwithstanding limitations discussed above, this study has several inherent strengths. To our knowledge, it is the only study to examine substance use, sex-risk behavior, and HIV simultaneously by race and sex among a large sample of both IDUs and NIDUs. Findings presented here have several important implications for HIV pre- vention and care among substance users. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health reports that approxi- mately 25% of individuals diagnosed with HIV/AIDS are in need of alcohol or other illicit drug use treatment [47]. Intervention programs that incorporate substance use treatment in addition to HIV education, particularly with respect to substance use and sex-risk behavior are im- perative. Research has noted a need for multidisciplinary approaches to treatment specifically designed for sub- stance users infected with HIV [48,49]. Multidisciplinary approaches incorporate medical, psychiatric, and sub- stance use treatment [50]. This type of treatment ap- proach may be particularly important for reducing sex- risk behavior among groups at high risk for HIV trans- mission. In fact, several intervention studies have noted some success in reducing sex-risk behavior among sub- stance users [50-53]. Although these studies present promising results, more research is needed to identify causes of this racial disparity, so that interven tio ns can be developed to reduce the rates of HIV infection in African Americans. There is a need for expansion of this type of treatment to high-risk groups in urban environments as HIV-positive substance users present a significant public health concern. REFERENCES [1] O. C. Nwanyanwu, S. Y. Chu, T. A. Green, J. W. Buehler and R. L. Berkelman, “Acquired-Immunodeficiency-Syn- drome in the United-States Associated with Injecting Drug-Use, 1981-1991,” The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, Vol. 19, No. 4, 1993, pp. 399-408. doi:10.3109/00952999309001630 [2] D. C. Des Jarlais, S. R. Friedman and W. Hopkins, “Risk Reduction for the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome among Intravenous Drug Users,” Annals of Internal Me- dicine, Vol. 103, No. 5, 1985, pp. 755-759. [3] R. E. Chaisson, A. R. Moss, R. Onishi, D. Osmond and J. R. Carlson, “Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection in Heterosexual Intravenous Drug Users in San Francisco,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 77, No. 2, 1987, pp. 169-172. doi:10.2105/AJPH.77.2.169 [4] E. E. Schoenbaum, D. Hartel, P. A. Selwyn, et al., “Risk Factors for Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection in Intravenous Drug Users,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 321, No. 13, 1989, pp. 874-879. doi:10.1056/NEJM198909283211306 [5] E. J. van Ameijden and R. A. Coutinho, “Maximum Im- pact of HIV Prevention Measures Targeted at Injecting Drug Users,” AIDS, Vol. 12, No. 6, 1998, pp. 625-633. doi:10.1097/00002030-199806000-00012 [6] R. Marx, S. O. Aral, R. T. Rolfs, C. E. Sterk and J. G. Kahn, “Crack, Sex, and STD,” Sexually Transmitted Dis- eases, Vol. 18, No. 2, 1991, pp. 92-101. doi:10.1097/00007435-199118020-00008 [7] R. J. Battjes, R. W. Pickens, Z. Amsel and L. S. Brown Jr., “Heterosexual Transmission of Human Immunodefi- ciency Virus among Intravenous Drug Users,” The Jour- nal of Infectious Diseases, Vol. 162, No. 5, 1990, pp. 1007-1011. doi:10.1093/infdis/162.5.1007 [8] I. H. Meyer and L. Dean, “Patterns of Sexual Behavior and Risk Taking among Young New York City Gay Men,” AIDS Education and Prevention, Vol. 7, Supple- ment 5, 1995, pp. 13-23. [9] R. B. Hays, S. M. Kegeles and T. J. Coates, “High HIV Risk-Taking among Young Gay Men,” AIDS, Vol. 4, No. 9, 1990, pp. 901-907. doi:10.1097/00002030-199009000-00011 [10] G. F. Lemp, A. M. Hirozawa, D. Givertz, et al., “Sero- prevalence of HIV and Risk Behaviors among Young Homosexual and Bisexual Men. The San Francisco/ Berkeley Young Men’s Survey,” The Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 272, No. 6, 1994, pp. 449-454. doi:10.1001/jama.1994.03520060049031 [11] D. H. Osmond, K. Page, J. Wiley, et al., “HIV Infection in Homosexual and Bisexual Men 18 to 29 Years of Age: The San Francisco Young Men’s Health Study,” Ameri- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA  Prevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Risk Behavior, and Recent Substance Use in a Sample of Urban Drug Users: Findings by Race and Sex 192 can Journal of Public Health, Vol. 84, No. 12, 1994, pp. 1933-1937. doi:10.2105/AJPH.84.12.1933 [12] J. Ruiz, M. Facer and R. K. Sun, “Risk Factors for Hu- man Immunodeficiency Virus Infection and Unprotected Anal Intercourse among Young Men Who Have Sex with Men,” Sexually Transmitted Diseases, Vol. 25, No. 2, 1998, pp. 100-107. doi:10.1097/00007435-199802000-00007 [13] G. R. Seage III, K. H. Mayer, W. R. Lenderking, et al., “HIV and Hepatitis B Infection and Risk Behavior in Young Gay and Bisexual Men,” Public Health Reports, Vol. 112, No. 2, 1997, pp. 158-167. [14] SAMHSA, “The NSDUH Report: HIV/AIDS and Sub- stance Use,” Rockville, 2010. [15] Hygiene DoHaM, “Maryland Vital Statistics Annual Re- port,” 2009. http://vsa.maryland.gov/doc/09annual.pdf [16] Hygiene MDoHaM, “Baltimore City HIV/AIDS Statistics Fact Sheet,” 2008. [17] SAMHSA, “National Survey on Drug Use and Health,” 2007-2008. [18] Enters for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; 2008). Estimates of New HIV Infections in the United States. [19] S. A. Strathdee and S. G. Sherman, “The Role of Sexual Transmission of HIV Infection among Injection and Non-Injection Drug Users,” Journal of Urban Health, Vol. 80, Suppl. 3, 2003, pp. 7-14. [20] I. Kuo, A. E. Greenberg, M. Magnus, et al., “High Preva- lence of Substance Use among Heterosexuals Living in Communities with High Rates of AIDS and Poverty in Washington, DC,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2011. [21] L. Degenhardt, B. Mathers, P. Vickerman, T. Rhodes, C. Latkin and M. Hickman, “HIV in People Who Use Drugs 2 Prevention of HIV Infection for People Who Inject Drugs: Why Individual, Structural, and Combination Ap- proaches Are Needed,” The Lancet, Vol. 376, No. 9737, 2010, pp. 285-301. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60742-8 [22] E. Volz, S. D. Frost, R. Rothenberg and L. A. Meyers, “Epidemiological Bridging by Injection Drug Use Drives an Early Hiv Epidemic,” Epidemics, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2010, pp. 155-164. doi:10.1016/j.epidem.2010.06.003 [23] A. Neaigus, S. R. Friedman, B. J. Kottiri and D. C. D. Jarlais, “HIV Risk Networks and HIV Transmission among Injecting Drug Users,” Evaluation and Program Planning, Vol. 24, No. 2, 2001, pp. 221-226. doi:10.1016/S0149-7189(01)00012-X [24] D. J. Pilowsky, D. Hoover, B. Hadden, et al., “Impact of Social Network Characteristics on High-Risk Sexual Be- haviors among Non-Injection Drug Users,” Substance Use & Misuse, Vol. 42, No. 11, 2007, pp. 1629-1649. doi:10.1080/10826080701205372 [25] R. C. Neblett, M. Davey-Rothwell, G. Chander and C. A. Latkin, “Social Network Characteristics and HIV Sexual Risk Behavior among Urban African American Women,” Journal of Urban Health, Vol. 88, No. 1, 2011, pp. 54-65. doi:10.1007/s11524-010-9513-x [26] US Census Bureau, Maryland State Census, 2010. http://census.maryland.gov/ [27] D. Vlahov, J. C. Anthony, A. Munoz, et al., “The ALIVE Study, a Longitudinal Study of HIV-1 Infection in Intra- venous Drug Users: Description of Methods and Charac- teristics of Participants,” NIDA Research Monograph, Vol. 109, 1991, pp. 75-100. [28] M. M. Mitchell and W. W. Latimer, “Unprotected Casual Sex and Perceived Risk of Contracting HIV among Drug Users in Baltimore, Maryland: Evaluating the Influence of Non-Injection versus Injection Drug User Status,” AIDS Care, Vol. 21, No. 2, 2009, pp. 221-230. doi:10.1080/09540120801982897 [29] J. Pallant, “SPSS Survival Manual,” McGraw-Hill, New York, 2007. [30] SPSS, PASW Statistics 17, SPSS Inc., Chicago, 2009. [31] D. C. Des Jarlais, K. Arasteh and S. R. Friedman, “HIV among Drug Users at Beth Israel Medical Center, New York City, the First 25 Years,” Substance Use & Misuse, Vol. 46, No. 2-3, 2011, pp. 131-139. doi:10.3109/10826084.2011.521456 [32] CDC CfDC, “Update to Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Di- agnoses of HIV/AIDS-33 States, 2001-2005,” Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007. [33] C. Latkin, W. Mandell, M. Oziemkowska, et al., “Using Social Network Analysis to Study Patterns of Drug-Use among Urban Drug-Users at High-Risk for HIV-AIDS,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Vol. 38, No. 1, 1995, pp. 1-9. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(94)01082-V [34] C. A. Latkin, S. J. Kuramoto, M. A. Davey-Rothwell and K. E. Tobin, “Social Norms, Social Networks, and HIV Risk Behavior among Injection Drug Users,” AIDS and Behavior, Vol. 14, No. 5, 2010, pp. 1159-1168. doi:10.1007/s10461-009-9576-4 [35] N. S. Padian, S. C. Shiboski and N. P. Jewell, “Female- to-Male Transmission of Human-Immunodeficiency-Vi- rus,” The Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 266, No. 12, 1991, pp. 1664-1667. doi:10.1001/jama.266.12.1664 [36] I. Devincenzi, R. A. Ancellepark, J. B. Brunet, et al., “Comparison of Female to Male and Male to Female Transmission of HIV in 563 Stable Couples,” British Medical Journal, Vol. 304, No. 6830, 1992, pp. 809-813. doi:10.1136/bmj.304.6830.809 [37] R. Seng, M. Rolland, G. Beck-Wirth, et al., “Trends in Unsafe Sex and Influence of Viral Load among Patients Followed Since Primary HIV Infection, 2000 to 2009,” AIDS, 2011. [38] M. Miller and A. Neaigus, “Sex Partner Support, Drug Use and Sex Risk among HIV-Negative Non-Injecting Heroin Users,” AIDS Care, Vol. 14, No. 6, 2002, pp. 801-813. doi:10.1080/0954012021000031877 [39] S. B. Montgomery, J. Hyde, C. J. De Rosa, et al., “Gen- der Differences in HIV Risk Behaviors among Young In- jectors and Their Social Network Members,” The Ameri- can Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, Vol. 28, No. 3, 2002, pp. 453-475. doi:10.1081/ADA-120006736 [40] M. Miller, C. T. Korves and T. Fernandez, “The Social Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA  Prevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Risk Behavior, and Recent Substance Use in a Sample of Urban Drug Users: Findings by Race and Sex Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA 193 Epidemiology of HIV Transmission among African American Women Who Use Drugs and Their Social Net- work Members,” AIDS Care-Psychological and Socio- Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, Vol. 19, No. 7, 2007, pp. 858-865. [41] Control CfD, “Update to Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Diagnoses of HIV/AIDS-33 States, 2001-2005,” 2007. [42] I. Devincenzi, “Heterosexual Transmission of HIV,” The Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 267, No. 14, 1992, pp. 1909-1919. doi:10.1001/jama.267.14.1919 [43] D. Castor, D. J. Pilowsky, B. Hadden, et al., “Sexual Risk Reduction among Non-Injection Drug Users: Report of a Randomized Controlled Trial,” AIDS Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2010, pp. 62-70. [44] Group NMHSPTfAAC, “The Contribution of Male and Female Partners’ Substance Use to Sexual Risks and STDs among African American HIV Serodiscordant Cou- ples,” AIDS and Behavior, Vol. 14, No. 5, 2010, pp. 1045-1054. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9695-y [45] D. L. Jones, D. Waldrop-Valverde, P. Gonzalez, et al., “Mental Health in HIV Seronegative and Seropositive IDUs in South Florida,” AIDS Care, Vol. 22, No. 2, 2010, pp. 152-158. doi:10.1080/09540120903039851 [46] S. Darke, “Self-Report among Injecting Drug Users: A review,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Vol. 51, No. 3, 1998, pp. 253-263. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(98)00028-3 [47] SAMHSA, “HIV/AIDS and Substance Use,” 2010. [48] F. L. Altice, A. Kamarulzaman, V. V. Soriano, M. Sche- chter and G. H. Friedland, “Treatment of Medical, Psy- chiatric, and Substance-Use Comorbidities in People In- fected with HIV Who Use Drugs,” The Lancet, Vol. 376, No. 9738, 2010, pp. 367-387. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60829-X [49] M. S. Friedman, M. P. Marshal, R. Sta ll, et al., “Associa- tions between Substance Use, Sexual Risk Taking and HIV Treatment Adherence among Homeless People Liv- ing with HIV,” AIDS Care, Vol. 21, No. 6, 2009, pp. 692-700. doi:10.1080/09540120802513709 [50] L. N. Drumright and G. N. Colfax, “HIV Risk and Pre- vention for Non-Injection Substance Users, in HIV Pre- vention: A Comprehensive Approach,” Academic Press, Burlington, 2009. [51] S. Magura, S. Y. Kang and J. L. Shapiro, “Outcomes of Intensive AIDS Education for Male Adolescent Drug Us- ers in Jail,” Journal of Adolescent Health, Vol. 15, No. 6, 1994, pp. 457-463. doi:10.1016/1054-139X(94)90492-L [52] J. S. Lawrence, R. A. Crosby, T. L. Brasfield and R. E. O’Bannon III, “Reducing STD and HIV Risk Behavior of Substance-Dependent Adolescents: A Randomized Con- trolled Trial,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psy- chology, Vol. 70, No. 4, 2002, pp. 1010-1021. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.70.4.1010 [53] W. M. Wechsberg, W. K. Luseno, R. S. Karg, et al., “Al- cohol, Cannabis, and Methamphetamine Use and Other Risk Behaviours among Black and Coloured South Afri- can Women: A Small Randomized Trial in the Western Cape,” International Journal of Drug Policy, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2008, pp. 130-139. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.11.018

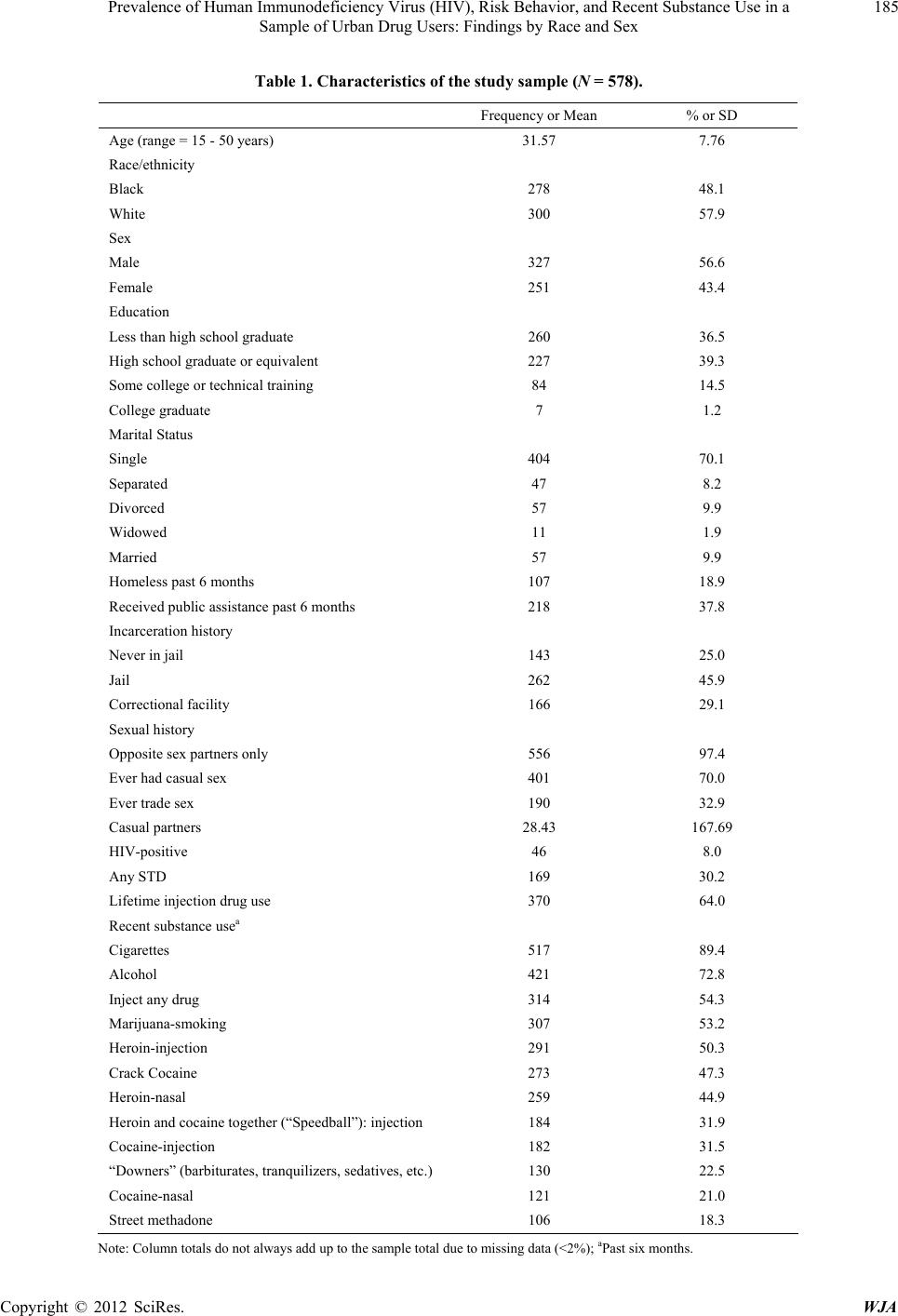

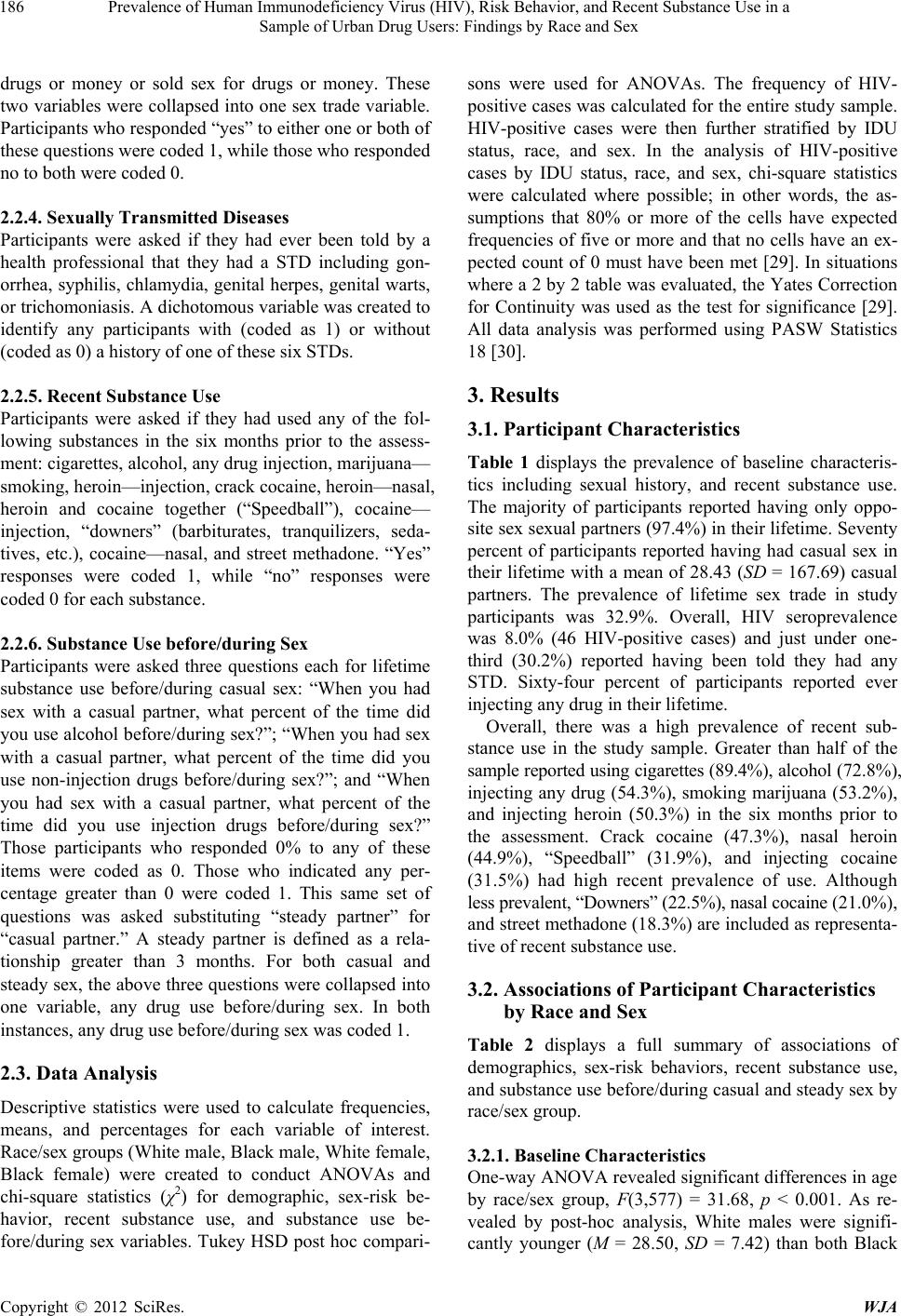

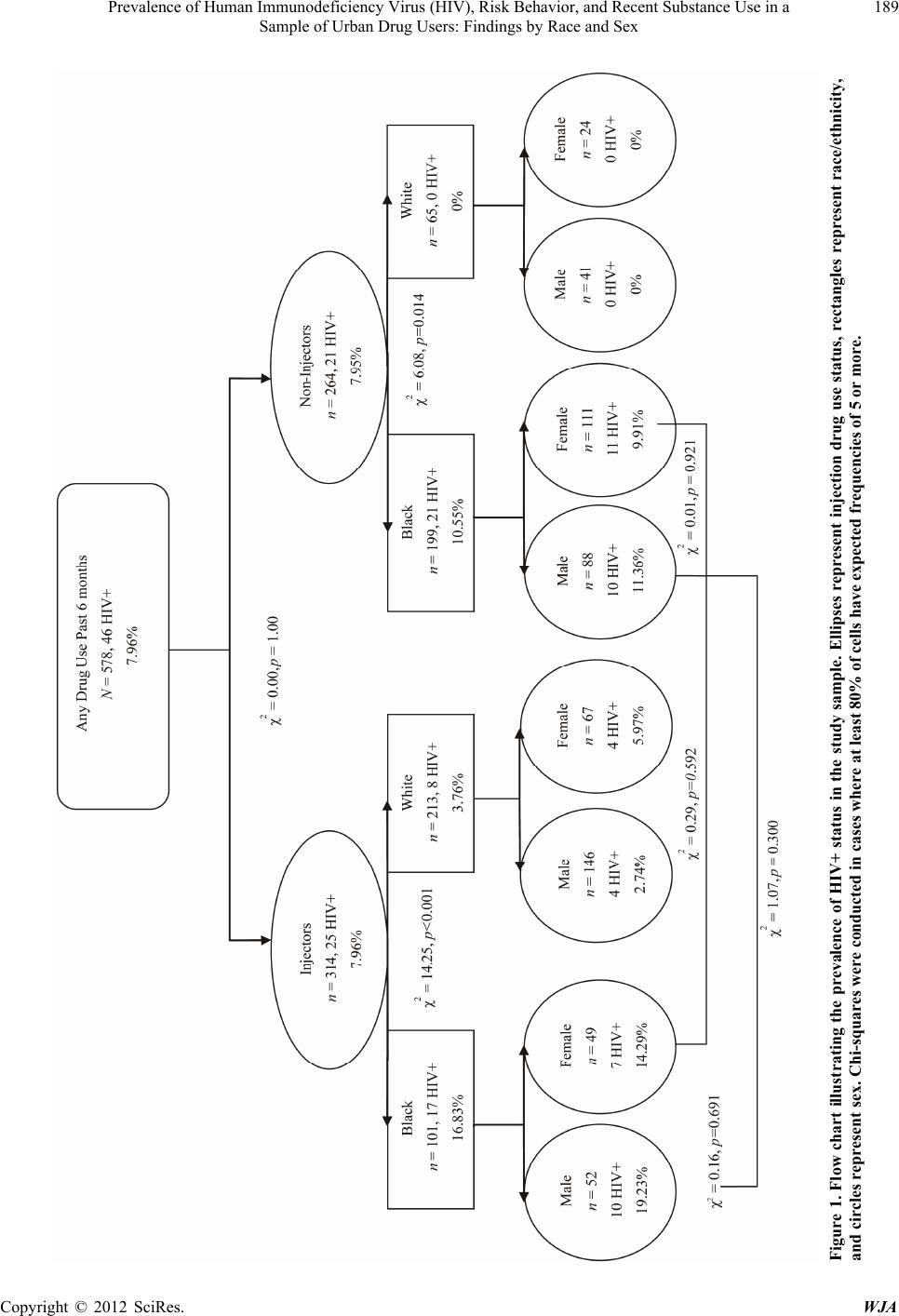

|