World Journal of AIDS, 2012, 2, 126-134 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/wja.2012.23018 Published Online September 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/wja) 1 Depression and Its Relationship to Work Status and Income among HIV Clients in Uganda Glenn J. Wagner1*, Bonnie Ghosh-Dastidar1, Dickens Akena2, Noeline Nakasujja2, Elialilia Okello2 Emmanuel Luyirika3, Seggane Musisi2 1RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, USA; 2Department of Psychiatry, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda; 3Mengo Hospital, Kampala, Uganda. Email: *gwagner@rand.org Received May 14th, 2012; revised June 21st, 2012; accepted June 30th, 2012 ABSTRACT Purpose: Despite high levels of depression among persons living with HIV (PLWHIV), little research has investigated the relationship of depr ession to work status and income in PLWHIV in sub-Saharan Africa, which was the focus of this analysis. Methods: Baseline data from a prospective longitudinal cohort of 798 HIV patients starting antiretroviral therapy in Kampala, Uganda were examined. In separate multivariate analyses, we examined whether depressive sever- ity and symptom type [as measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)] and major depression [diagnosed with the Mini International Neuropsych iatric Interview (MINI)] were associated with work status and income, control- ling for demographics, physical health functioning, work self-efficacy, social support and internalized HIV stigma. Re- sults: 14% of the sample had Major Depression and 66% were currently working. Each measure of depression (PHQ-9 total score, somatic and cognitive subscales; Major Depression diagnosis) was associated with not working and lower average weekly income in bivariate analysis. However, none of the depression measures remained associated with work and income in multivariate analyses that contro lled for other variables associated with these economic outcomes. Con- clusions: These findings suggest that while depression is related to work and income, its influence may only be indirect through its relationship to other factors such as work self-efficacy and physical health functioning. Keywords: Depression; HIV/AIDS; Work; Income; Physical Health Functioning; Work Self-Efficacy 1. Introduction In sub-Saharan Africa, where two-thirds of the world’s HIV-infected population resides [1], rates of depression range between 15% - 30% when assessed using diagnos- tic interviews [2-4], and 30% - 50% when using self- reports [2,3,5-7].In the context of HIV, the negative in- fluence of depression has most often been examined with regard to non-adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy (ART) [8,9], accelerated disease progression [10,11], and increased sexual risk behavior [12,13], but little research has investigated the role of depression in the economic well-being of persons living with HIV (PLWHIV). Un- derstanding how depression may influence ability to work, earn income and provide for self and one’s family has implications for policy and funding regarding inte- gration of mental health services in to HIV care programs that are largely void of such services in sub-Saharan Af- rica. HIV disease may impact economic well-being through various mechanisms, perhaps the most direct of which is deterioration of physical health, which can impair work functioning and productivity, and even render some indi- viduals unable to work [14]. However, the social and psychological components of living with HIV can also affect work and income generation, as stigma and dis- crimination can co ntribute to a hostile work environment or hamper business pa tronage, and de pression can lead to a lack of motivation, interest or energy needed to seek work or function effectively on the job. Drawing from Social Cognitive Theory [15], and in the context of HIV, we posit that physical and mental health, which are often correlated, are key to a person’s self-efficacy and expected outcomes regarding work- related behavior and ability to earn income. When so me- one is physically healthy and functioning well, their mood is positive and optimistic, and they feel confident and motivated to act on their goals and needs, including the ability to find and perform work. Conversely, physic- cal deterioration or depression can result in fatigue, physical impairment, and loss of motivation and self- confidence to engage in healthy, constructive behaviors such as food and income generating activity. *Corresponding a uthor. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA  Depression and Its Relationship to Work Status and Income among HIV Clients in Uganda 127 While there is some evidence of the relationship be- tween depression and lower productivity and unemploy- ment among PLWHIV [16], there is a paucity of data from resource constrained settings such as sub-Saharan Africa. In a qualitative study of depression among PLWHIV in Uganda, Okello found that depression was often conceptualized as a problem related to worrisome thoughts stemming from socioeconomic problems [17]. Depression was commonly expressed in physical mani- festations such as headache, loss of appetite or fatigue, but after probing, respondents often described worrying about not being able to work, keeping their children in school, and providing for their family in general. In our previous research with HIV clients in Uganda, we found depression to be strong ly associated with work status. Only 34% of depressed participants were working compared to 64% of those not depressed, and depression remained an independent predictor of work status after controlling for de mograp h ics, ph ysical health fun ctio ning and social support [18]. However, this earlier study did not explore whether different types of depressive symp- toms (i.e., somatic vs. cognitive) have a differential im- pact on work status, or specifically explore the relation- ship between depression and income. In this paper from our current study, we report find- ings from an examination of the relationship between depression and economic outcomes, including both work status and income level, among HIV clients who are about to start ART in Uganda. More specifically, we as- sessed whether these relationships varied by depression severity and type of depressive symptoms (somatic vs cognitive), and remained significant after controlling for other factors (such as physical health functioning) that may influence work activity. 2. Methods 2.1. Study Design Participants were enrolled in a longitudinal prospective cohort study designed to examine the effects of depres- sion and antidepressant treatment on multiple health outcomes of ART. Participants completed assessments at initiation of ART and 6 and 12 months after the start of ART; depression was assessed at each time point, and antidepressants were prescribed to those who were clini- cally depressed. However, the analysis for this paper is only conducted with data collected at the baseline inter- view, prior to the start of ART and antidepressant ther- apy, but after a variable amount of time engaged in HIV care. 2.2. Setting The study enrolled clients starting ART at four HIV clinics operated by Mildmay Uganda, in urban Kampala and the rural towns of Mityana, Naggalama and Mukono (the latter two are within one hour drive of Kampala). All sites are located in the relatively stable eastern region of the country. This region offers increased economic ad- vantages, relative to the rest of Uganda, because of its close proximity to Kampala with the most opportunities in the formal labor market, and to Lake Victoria with opportunities for employment in the fishing industry. These clinics generally serve clients in the lower socio- economic strata and who work in the informal labor market (e.g., commercial or subsistence farming; selling goods or employed in microenterprises). 2.3. Sample Clients 18 years or older who had just been prescribed ART by their primary care provider, and agreed to start treatment, were eligible for enrollment. At each study clinic, the primary eligibility criteria for initiation of ART were a CD4 cell count < 250 cells/mm3 or a diag- nosis of WHO HIV disease stage III or IV (AIDS diag- nosis). Between September 2010 and February 2011, clients were enrolled consecutively at the visit during which their eligibility for ART was determined. All par- ticipants were required to provide written informed con- sent. The study protocol was approved by IRBs at RAND and Makerere University, as well as the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology. 2.4. Measures All measures were interviewer-administered in Luganda, the most common language in this region of Uganda. The entire questionnaire was translated into Luganda using standard translation and back-translation methodology. Masters level psychologists were trained to administer the study assessments. Medical officers, with psychiat- ric-specific training, performed the psychiatric evalua- tions. Current work status was assessed with the question, “During the last 7 days did you do any work for pay in cash or in kind, or in your own business activity or your own agricultural or livestock activity?” Those who said “No” were then asked if they had worked in their fam- ily’s business or farm in the last 7 days. An affirmative response to either of these two questions was classified as currently working. If the respondent did not work in the past 7 days, they were asked if they had worked in the past 6 months. Participants who had worked in the past 6 months (including those who worked in the past 7 days) were asked to describe the nature of the work. Ccu- tions were elicited and classified into one of three cate- ries: formal salaried employment in a skilled profession; running a microenterprise (e.g., selling merchandise) or Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA  Depression and Its Relationship to Work Status and Income among HIV Clients in Uganda 128 working in the service industry (e.g., waitress); and farming or fishing. Income was assessed among those who reported working in the past 6 months (including those working in the past 7 days). Participants were asked to report the amount of their last payment, and the period of time this payment corresponded to (i.e., day, week, or month). Average weekly income was calculated by multiplying reported daily payment by five (assuming 5 work days per week), or dividing monthly payment by four. To assess the perceived impact of HIV on work and income, participants were asked if their income was bet- ter, worse or similar since their HIV diagnosis, and whether they had to stop or cut down on the work they used to do since the diagnosis. Participants were also asked how often their health had affected their ability to work over the past month, with response options being “never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”, “most of the time” and “not able to work”. Depression. The 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was used to measure the presence of depressive symptoms over the past 2 weeks. Each of the 9 items corresponds to the symptoms used to diagnose depress- sion according to DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistics Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition) criteria [19]; responses to each item range from 0 “not at all” to 3 “nearly every day”. Items were summed with a possible range of 0 - 27, and scores > 9 correspond high ly to ma- jor depression as determined by a diagnostic clinical in- terview [20]. The items were divided into somatic (4 items: fatigue, difficulty sleeping, poor appetite/over- eating, psychomotor retardation) and cognitive symp- toms (5 items: depressed mood, loss of interest, feeling bad about oneself, trouble concentrating, suicidal tho ug hts) of depression to create somatic and cognitive subscales, with each subscale being the sum of the included items. The PHQ-9 has been used successfully with HIV-in- fected individuals in other studies within sub-Saharan Africa [21]. Participants who scored > 9 on th e PHQ-9, or who the interviewer (trained psychologists) thought might be de- pressed despite having a score < 10 (based on clinical impression), were referred to the medical officer for a psychiatric evaluation that included administration of the depression module of the Mini International Neuropsy- chiatric Interview (MINI) [22]. Physical health. CD4 count and WHO HIV disease stage (stages I to IV, with III and IV representing an AIDS diagnosis) were abstracted from the client’s medi- cal chart. The Medical Outcomes Study HIV Health Survey (MOS-HIV), a scale that has been validated in Uganda [23], was used to assess physical health func- tioning. For this analysis, we have included the physical functioning subscale of the MOS-HIV, which consists of 6 items that ask the respondent to indicate whether their current health limits their ability to engage in activ ities of daily life ranging from eating, dressing and bathing to more vigorous activities such as running or lifting heavy objects; the response options include 1 “yes, limited a lot”, 2 “yes, limited a little” and 3 “no”. Items were summed and the scale score was transformed to a stan- dardized scor e of 0 - 100 with higher scores repr esenting better physical fu nct i o ni n g. Work self-efficacy was assessed by asking respon- dents to rate their level of confidence in being able to “find work to provid e enough food or money for yourself (and your family)?” using a scale of 0 - 10 with 10 indi- cating high confidence. Internalized HIV stigma was assessed with an 8-item scale developed by Kalichman et al. [24]. Examples of items include “Being HIV positive makes me feel dam- aged” and “I am ashamed that I am HIV positive”; re- sponse options range from 1 “disagree strongly” to 5 “agree strongly”, and a mean item score is calculated. Higher scores represent greater stigma. Social support was assessed using a single item adapted from the ACTG assessment battery [25], “I can count on my family and friends to give me the support I need”, and a 4-point rating scale from 1 “strongly dis- agree” to 4 “strongly agree”; higher scores represent greater support. Demographic and background characteristics in- cluded age, gender, education level (classified as primary school or less vs at least some secondary education), re- lationship status (binary indicator of whether the partici- pant was married or in a committed relationship versus single, divorced or widowed), and urban (those attending the Kampala clinic) versus rural (attending one of the other three clinics) location. 2.5. Data Analysis Bivariate statistics (independent 2-tailed t-tests, Chi Square tests) were used to examine correlates of current work status (binary variable) and average weekly income. In the multivariate analysis, we included correlates of work status and income in separate logistic and linear regression analyses, respectively. A logarithmic trans- formation of the income variable was used as the de- pendent variable in the regression model because a scat- terplot of income and PHQ-9 total score indicated het- eroscedasticity. To assess the relationship between de- pression and each of these two economic outcomes, separate models were run with the binary indicator of Major Depression (measured by the MINI), the PHQ-9 total score, and a third model with both the somatic and cognitive subscales included. In addition to the depres- sion variables, we included demographics (age, gender, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA  Depression and Its Relationship to Work Status and Income among HIV Clients in Uganda 129 education), indicator of urban or rural clinic, physical health functioning, internalized HIV stigma, social sup- port, and work-related self-efficacy in all regression models. Also, type of job was included in the model pre- dicting income. 3. Results 3.1. Sample Characteristics The enrolled sample included 798 clients, 343(43%) at- tending the clinic in Kampala, 118 in Naggalama, 100 in Mukono, and 237 in Mityana. The characteristics of the total sample are presented in Table 1. Two-thirds of the sample is female, roughly a third was married or in a committed relationship, and only a small minority had completed at least some secondary schooling. Although all participants were starting ART, only 19% had WHO disease stage III or IV (AIDS diagnosis), but 93% had a CD4 count < 250 cells/mm3. Work status. Average time since HIV diagnosis was 24.3 months (median = 14.1 months), and 76% were di- agnosed more than 6 months prior to study enrollment. When asked about the impact of HIV on their work, 18% reported ever having lost a job because of HIV, 38% had to cut down on their work or perform less physically d e- manding work, and 18% had to stop working at least temporarily. Over half (54%) of the sample stated that their health affected their ability to work some or most of the past month, and another 18% reported being unable to work at all in the past month because of their health. Table 1. Baseline sample characteristics. Variable Total Sample (N = 798) Demographics Mean age (SD) 36.1 (9.5) Male 33.6% At least some secondary education 15.3% Working (past 7 days) 65.9% Mean weekly income (median) 45,513 (25,000) Married or in committed relation ship 44.1% Urban lo cation (at tende d Kampal a clini c) 43% Physical health Mean CD4 count (SD) 155 (85.5) AIDS diagnosis (WHO stage 3/4) 19.4% Mental health Depression [PHQ-9 tot al; mean (SD)] 3.97 (4.48) Major Depression ( MINI; 5+ symptoms) 13.9% When asked about current work status, 66% reported working over the past 7 days, and an additional 7% had worked in the past 6 months but not over the past 7 days. Among those who had worked in the past 6 months (in- cluding those who had worked in the past 7 days), roughly equal proportions had jobs in the formal labor market (e.g., skilled laborer such as painter, mechanic) and earned salaries (34%), sold things as part of a mi- croenterprise or were part of the service industry (e.g., waitress, worked at retail shop) (32%), or worked in farming o r fishing ( 34%). Income. Most (57%) believed that their income level had declined since their HIV diagnosis, whereas 34% indicated that their current income was similar to what is was prior to the diagnosis, and 9% said their income had increased. Average weekly income at baseline for those who had worked in the past 6 months was 45,513 Uganda Shillings (SD = 67,914; median = 25,000), or about $20 USD. Depression. The sample average on the PHQ-9 was 4.0 (SD = 4.5; range: 0 - 23), with 13% scoring at least 10. When examining individual items of the PHQ-9 that respondents reported experiencing at least ‘more than half the days’ over the past two weeks, depressed mood and loss of interest—the two hallmark symptoms of de- pression—were present in 13% and 14% of the sample, respectively. The other most frequent symptoms were somatic, including trouble sleeping (1 8%), fatigue (19%) and poor appetite (20%). Of the 187 participants who were referred for administration of the MINI, 59% met criteria for Major Depression; with the rest of the sample classified as not depressed, 14% of the total sample had Major Dep r ession. Depression, as measured by the PHQ-9 total score, was negatively correlated with physical health function- ing (r = –0.43; p = 0.000), work self-efficacy (r = –0.31; p = 0.000), and social support (r = –0.17; p = 0.000), and positively correlated with internalized HIV stigma (r = 0.40; p = 0.000). 3.2. Relationship between Depression and Work Status In bivariate analyses, those who were currently working (worked in the past 7 days) had a significantly lower level of depression as measured by the PHQ-9 total score, lower cognitive and somatic depressive symptomatolo gy, and were less likely to have Major Depression (see Table 2). Better physical health functioning, lower internalized HIV stigma, greater work self-efficacy, and lower gen- eral social support were all significantly associated with currently working as well. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were then per- formed to further examine the relationship between de- pression and current work status. In the analysis with the Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA  Depression and Its Relationship to Work Status and Income among HIV Clients in Uganda Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA 130 binary indicator of Major Depression (as measured by the MINI) in the model, variables independently associated with a greater likelihood of working included older age, rural location, better physical health functioning, higher work self-efficacy, and lower social support; male gender was marginally associated (p = 0.07) with working (see Table 3). Analyses with the PHQ-9 total score, and the somatic and cognitive PHQ-9 subscales, as the depres- sion measures in the model resulted in equivalent find- ings with the same variables being associated with work status (data not shown). The depression measure(s) was not significantly associated with work status in any of the models, after controlling for the covariates in the model. 3.3. Relationship between Depression and Income In bivariate analyses, average weekly income was nega- tively correlated with each of the PHQ-9 depression variables (total score and somatic and cognitiv e subscales) (see Table 4), and income was significantly lower in those with Major Depression (mean = 31,591 Shillings) compared to those not depressed (mean = 47,233; p = 0.004). Physical health functioning and work self-effi- cacy were significant positive correlates of income, while greater general social support was marginally associated with higher income. Table 2. Bivariate analysis of the relationship between work status, de pression, and other explanatory variables. Variable Not working Working p-Value Depression variables PHQ-9 total score 5.03 3.48 0.000 Cognitive sub-scale of PHQ-9 2.02 1.44 0.003 Somatic sub-scale of PHQ-9 3.00 2.01 0.000 Major depression ( MINI diagnosis) 17.7% 12.1% 0.033 Other explanatory variables Physical health Functioning 66.6 82.9 0.000 Internalized HIV stigma 2.35 2.20 0.047 Work self-efficacy 5.48 7.17 0.000 General social s upport 3.57 3.36 0.002 Table 3. Multivariate regression analyses of the association of Major Depression and other explanatory variables with work status and weekly income. Weekly income1 Work status Variable Beta SE OR 95% CI Major depression (MINI diagnosis) 0. 09 0.17 1.31 (0.77, 2.22) Age 0.00 0.01 1.02* (1.00, 1.04) Secondary education 0.48*** 0.14 1.21 (0.73, 2.00) Male gender 0.51*** 0.11 1.42 (0.97, 2.07) Urban location 0.39*** 0.12 0.48*** (0.32, 0.71) Job type: sales & service 0.02 0.13 - - Job type: farming & fishing –0.64*** 0.14 - - Physical health funct i oning 0.00 0.00 1.02*** (1.02, 1.03) Internalized HIV stigma –0.0 5 0.06 0.96 (0.79, 1.17 ) Work self-efficacy 0.05* 0.02 1.23*** (1.15, 1.32) Social support 0.13* 0.06 0.65*** (0.53, 0.81) *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, 1Natural log transformation of income; SE = standard error; OR = Odds Ratio; CI = confidence interval.  Depression and Its Relationship to Work Status and Income among HIV Clients in Uganda 131 Table 4. Bivariate analysis of the relationship between weekly income, depression, and other explanatory variables. Correlation coefficient with weekly income1 P-value Depression Measures PHQ-9 total score –0.129 0.004 Cognitive sub-scale of PHQ-9 –0.103 0.022 Somatic sub-scale of PHQ -9 –0.128 0.004 Other Explanatory Variables Physical health functioning 0.119 0.008 Internalized HIV stigma –0.034 0.447 Work self-efficacy 0.118 0.009 Social support 0.079 0.079 1Natural lo g transfor mation of i ncome. Multivariate linear regression analyses were performed to assess the relationship between depression and income; the same covariates were in the models plus the addition of the three-level categorization of job type (with skilled professional job type as the referent group). In the analy- sis with the binary indicator of Major Depression as the depression variable in the model, variables independently associated with a greater income were having any sec- ondary education, male gender, urban location, greater social support, higher work self-efficacy and marginally significant (p = 0.07) greater physical health functioning; working as a farmer or fisherman was associated with lower income (see Table 3). Analyses with the PHQ-9 total score, and the somatic and cognitive PHQ-9 sub- scales, in the models resulted in the same variables being significantly associated with income, except that work self-efficacy was marginally significant (p = 0.07) and physical health functioning was not significantly associ- ated in these models (data not shown). As with work status, the depression measure(s) was not associated with income in any of the models. 4. Discussion In this sample of HIV clients starting ART in Kampala, two-thirds were currently working and earning roughly $20 USD per week on average, which is similar to the national average for Uganda [26]. All of the study’s measures of depression were significantly associated with work status and income in bivariate analysis: cogni- tive and somatic depressive symptoms were negatively correlated with these outcomes, and higher levels of de- pression and major depressive disorder were associated with unemployment and earn ing less in come. The relationship between depression and impaired work activity can be explained by depressive features such as lack of motivation, poor concentration and fa- tigue. These findings are consistent with research by Kinyanda and colleagues, who found that depr ession was strongly associated with lower socioeconomic status and unemployment in a general population of Ugandans [27], as well as Kaharuza et al. [28] who found higher levels of depression to be associated with lower income among PLWHIV in Uganda. Furthermore, with it being difficult to distinguish between somatic depressive symptoms (e.g., poor appetite, fatigue) and physical symptoms of HIV disease, the fact that both cognitive and somatic symptoms were associated with work status and income supports the validity of the relationship between depres- sion and these economic outcomes. However, multivariate analysis revealed that none of the depression variables were independently associated with work status or income after controlling for demo- graphics and other predictors of economic outcomes. This suggests that while depression may have an influ- ence on work status and income, its primary influence may be indirect through its relationship with other key variables such as physical health functioning and work self-efficacy. For example, as someone’s physical func- tioning becomes more disabled or their self-confidence in being able to work and provide for their family is di- minished, they may be more likely to experience depres- sion and to lose work and earn less income. Also, de- pressive symptoms such as loss of interest or motivation, and fatigue, may contribute to lower work self-efficacy and challenge a person’s ability to work. However, when physical health functioning and self-efficacy are con- trolled for and held constant, depression no longer plays a significant role. The finding that depression is not an independent cor- relate of work status when controlling for other factors is contrary to the findings of our previous study of HIV clients in Uganda [18]. Rates of depression and engage- ment in work activity were similar in the prio r study, but what differed was that all patients had just entered HIV Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA  Depression and Its Relationship to Work Status and Income among HIV Clients in Uganda 132 care as opposed to the current study where most partici- pants had been in care for at least several months. It’s not clear what could explain the difference in this finding, but it’s possible that the lower levels of physical healthy functioning and self-confidence related to work that are evident prior to the start of care may influence the vari- ability of these v ariables in ways that d iminish the ab ility to detect a relationship between depression and work status when these variables are controlled for. More re- search is needed to replicate these findings and to bring clarity to these relationships. Our finding that work-related self-efficacy was a sig- nificant predictor of both work status and income level is consistent with Social Cognitive Theory [15], which highlights self-efficacy as a primary cognition through which mental and physical health may influence these economic outcomes. The cross-sectional data in this analysis limits our ability to thoroughly evaluate self- efficacy as a mediator of the effects of physical and mental health; however, we will be able to conduct me- diational analysis when the longitudinal data becomes available. Several demographic characteristics were associated with work and income. Although younger clients are expected to have superior physical health and strength for performing physical labor, our results showed that older clients were more likely to be working, perhaps as a result of their greater work experience and employ- ment-related skills. Men had higher levels of employ- ment and income, which may indicate that men have more work options, including opportunities for higher paying jobs, because of the gender roles and disparities present in African culture [29]. The association between higher education level and higher income is probably a reflection of the greater chances and qualifications for a higher paying job provided by a better education, even among those largely engaged in the informal labor mar- ket. Lastly, urban location was associated with a lower likelihood of working, but higher income among those working. While this may seem contradictory, those in rural settings have greater access to jobs in farming and fishing, while urban dwellers may have greater access to the formal labor market with higher paying jobs. Mixed findings were found with regard to social sup- port, which was negatively correlated with work status, but positively associated with income. Lower social sup- port was associated with a greater likelihood of working, perhaps because those who are working are more self- sufficient and thus in less need of social support. Mean- while, greater social support may be associated with higher income through increased patronage (among those who sell things or have a small business). There are a number of limitations to the study. The findings cannot be considered representative of all PLWHIV in Uganda or sub-Saharan Africa; all partici- pants were engaged in HIV care, and attending a pro- gram that requires its clients to have a treatment sup- porter (like most HIV clinics in sub-Saharan Africa) be- fore being prescribed antiretroviral therapy, which sug- gests having some level of social support that may influ- ence both work status and income. Also, with cross-sec- tional data, we cannot make causal statements. However, an advantage of the baseline data is that it allows us to explore the influence of depression prior to the influx of ART and associated improvements in physical health and mental outlook. The longitudinal data collected after the participants have received ART for one year will allow us to assess the impact of treatment and improved health on economic outcomes, and allow us to explore temporal and causal pathways, including the use of mediational analysis to better examine the effects of depression. In conclusion, our study data reveal an association between depression and work status and income, but in- dicate that such influences are not independent direct effects in the presence of other factors that also influence work status and income. Rather, depression may indi- rectly affect economic well-being through its relationsh ip to other key factors such as physical health functioning and work self-efficacy. Further research with longitud- nal prospective data is needed to examine the possible meditational role of depression and mental health on the impact of ART and HIV care on economic well-being. Regardless of whether depression has direct or indirect effects on work, income and other aspects of economic well-being, our findings contribute to the growing body of evidence that reveals the role of depression in imped- ing key public health outcomes among PLWHIV and thus the need for integration of mental health services into HIV care in sub-Saharan Africa. 5. Acknowledgements Funding for this research is from a grant from the Na- tional Institute of Mental Health (Grant No. 1R01MH- 083568; PI: G. Wagner). REFERENCES [1] United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), “Towards Universal Access: Scaling up Priority HIV/ AIDS Interventions in the Health Sector,” Progress Re- port, 2008. [2] R. Brandt, “The Mental Health of People Living with HIV/AIDS in Africa: A Systematic Review,” African Journal of AIDS Research, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2009, pp. 123- 133. doi:10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.2.1.853 [3] P. Y. Collins, A. R. Homan, M. C. Freeman and V. Patel, “What Is the Relevance of Mental Health to HIV/AIDS Care and Treatment Programs in Developing Countries? Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA  Depression and Its Relationship to Work Status and Income among HIV Clients in Uganda 133 A Systematic Review,” AIDS, Vol. 20, No. 12, 2006, pp. 1571-1582. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000238402.70379.d4 [4] L. Myer, J. Smit, L. L. Le Roux, S. Parker, D. J. Stein and S. Seedat, “Common Mental Disorders among HIV-In- fected Individuals in South Africa: Prevalence, Predictors, and Validation of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scales,” AIDS Patient Care STDs, Vol. 22, No. 2, 2008, pp. 147-157. doi:10.1089/apc.2007.0102 [5] B. O. Olleya, S. Seedat and D. J. Stein, “Persistence of Psychiatric Disorders in a Cohort of HIV/AIDS Patients in South Africa: A 6-Month Follow-Up Study,” Journal of Psychosomatic Research, Vol. 61, No. 4, 2006, pp. 479-484. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.03.010 [6] M. B. Sebit, M. Tombe, S. Siziya, S. Balus, S. D. Nkomo and P. Maramba, “Prevalence of HIV/AIDS and Psy- chiatric Disorders and their Related Risk Factors among Adults in Epworth, Zimbabwe,” East African Medical Journal, Vol. 80, No. 10, 2003, pp. 503-512. [7] P. Bolton, C. M. Wilk and L. Ndogoni. “Assessment of Depression Prevalence in Rural Uganda Using Symptom and Function Criteria,” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, Vol. 39, No. 6, 2004, pp. 442-447. doi:10.1007/s00127-004-0763-3 [8] A. Ammassari, A. Antinori, M. S. Aloisi, M. P. Trotta, R. Murri, L. Bartoli, A. D. Monforte, A. W. Wu and F. Sta- race, “Depressive Symptoms, Neurocognitive Impairment, and Adherence to Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy among HIV-Infected Persons,” Psychosomatics, Vol. 45, No. 5, 2004, pp. 394-402. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.45.5.394 [9] G. J. Wagner, K. Goggin, R. H. Remien, M. I. Rosen, J. Simoni, D. R. Bangsberg, H. Liu and MACH14 Inves- tigators, “A Closer Look at Depression and Its Relation- ship to HIV Antiretroviral Adherence,” Annals of Behav- ioral Medicine, Vol. 42, No. 3, 2011, pp. 352-360. doi:10.1007/s12160-011-9295-8 [10] J. R. Ickovics, M. E. Hamburger, D. Vlhaov, E. E. Schoenbaum, P. Schuman, R. J. Boland, J. Moore and HIV Epidemiology Research Study Group, “Mortality, CD4 Cell Count Decline, and Depressive Symptoms among HIV Sero-Positive Women: Longitudinal Analysis from the HIV Epidemiology Research Study,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 285, No. 11, 2001, pp. 1466-1474. doi:10.1001/jama.285.11.1466 [11] G. Antelman, S. Kaaya, R. Wei, J. Mbwambo, G. I. Msamanga, W. W. Fawzi and M. C. Fawzi, “Depressive Symptoms Increase Risk of HIV Disease Progression and Mortality among Women in Tanzania,” Journal of Ac- quired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, Vol. 44, No. 4, 2007, pp. 470-477. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802f1318 [12] W. S. Comulada, M. J. Rotheram-Borus, W. Pequegnat, R. E. Weiss, K. A. Desmond, E. M. Arnold, R. H. Remien, S. F. Morin, L. S. Weinhardt, M. O. Johnson and M. A. Chesney, “Relationships over Time between Men- tal Health Symptoms and Transmission Risk among Per- sons Living with HIV,” Psychology of Addictive Behav- iors, Vol. 24, No. 1, 2010, pp. 109-118. doi:10.1037/a0018190 [13] G. J. Wagner, B. Ghosh-Dastidar, I. Holloway, C. Kityo, and P. Mugyenyi, “Depression in the Pathway of HIV Antiretroviral Effects on Sexual Risk Behavior among Patients in Uganda,” AIDS & Behavior, 2012, in Press. [14] G. J. Wagner, G. Ryan, A. Huynh, C. Kityo and P. Mu- gyenyi, “A Qualitative Analysis of the Economic Impact of HIV and Antiretroviral Therapy on Individuals and Households in Uganda,” AIDS Patient Care and STDs, Vol. 23, No. 9, 2009, pp. 793-798. doi:10.1089/apc.2009.0028 [15] A. Bandura, “Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory,” Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, 1986. [16] M. Preau, A. Bonnet, A. D. Bouhnik, L. Fernandez, Y. Obadia, B. Spire and VESPA, “Anhedonia and Depre- ssive Symptomatology among HIV-Infected Patients with Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapies (ANRS-EN12- VESPA),” Encephale, Vol. 34, No. 4, 2008, pp. 385-393. [17] E. Okello and S. Neema, “Explanatory Models and Help Seeking Behavior: Pathways to Psychiatric Care among Patients Admitted for Depression in Mulago Hospital, Kampala, Uganda,” Qualitative Health Research, Vol. 17, No, 1, 2007, pp. 14-25. doi:10.1177/1049732306296433 [18] G. J. Wagner, I. Holloway, B. Ghosh-Dastidar, C. Kityo and P. Mugyenyi, “Understanding the Influence of Depr- ession on Self-Efficacy, Work Status and Condom Use among HIV Clients in Uganda,” Journal of Psychoso- matic Research, Vol. 70, No. 5, 2010, pp. 440-448. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.10.003 [19] American Psychiatric Association, “American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,” 4th Edition, American Psychiatric Associa- tion, Washington, 1994. [20] K. Kroenke, R. L. Spitzer and J. B. W. Williams, “The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Meas- ure,” Journal of General Internal Medicine, Vol. 16, No. 9, 2001, pp. 606-613. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [21] P. O. Monahan, E. Shacham, M. Reece, K. Kroenke, W. O. Ong’or, O. Omollo, V. N. Yebei and C. Oiwang, “Va- lidity/Reliability of PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 Depression Scales among Adults Living with HIV/AIDS in Western Ken ya,” Journal of General Internal Medicine, Vol. 24, No. 2, 2009, pp. 189-197. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0846-z [22] D. V. Sheehan, Y. Lecrubier,K. H. Sheehan, J. Janavs, E. Weiller, A. Keskiner, J. Schinka, E. Knapp, M. Sheehan and G. Dunbar, “The Validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) According to the SCID-P and Its Reliability,” European Psychiatry, Vol. 12, No. 5, 1997, pp. 232-241. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83297-X [23] T. C. Mast, G. Kigozi, F. Wabwire-Mangen, R. Black, N. Sewankambo, D. Serwadda, R. Gray, M. Wawer and A. W. Wu, “Measuring Quality of Life among HIV-Infected Women Using a Culturally Adapted Questionnaire in Rakai District, Uganda,” AIDS Care, Vol. 16, No. 1, 2004, pp. 81-94. doi:10.1080/09540120310001633994 [24] S. C. Kalichman, L. C. Simbayi, S. Jooste, Y. Toefy, D. Cain, C. Cherry and A. Kagee, “Development of a Brief Scale to Measure AIDS-Related Stigma in South Africa,” AIDS & Behavior, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2005, pp. 135-143. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA  Depression and Its Relationship to Work Status and Income among HIV Clients in Uganda Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJA 134 doi:10.1007/s10461-005-3895-x [25] M. A. Chesney, J. R. Ickovics, D. B. Chambers, A. L. Gifford, J. Neidig, B. Zwickl and A. W. Wu, “Self-Re- ported Adherence to Antiretroviral Medications among Participants in HIV Clinical Trials: The AACTG Ad- herence Instruments: Patient Care Committee & Adher- ence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG),” AIDS Care, Vol. 12, No. 3, 2000, pp. 255-266. doi:10.1080/09540120050042891 [26] Central Intelligence Agency, “The World Factbook,” 2009. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbo ok/index.html [27] E. Kinyanda, P. Woodburn, J. Tugumisirize, J. Kagugube, S. Ndyanabangi and V. Patel, “Poverty, Life Events and the Risk for Depression in Uganda,” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, Vol. 46, No. 1, 2011, pp. 35-44. doi:10.1007/s00127-009-0164-8 [28] F. M. Kaharuza, R. Bunnell, S. Moss, D. W. Purcell, W. Bikaako-Kajura, N. Wamai, R. Downing, P. Solberg, A. Coutinho and J. Mermin, “Depression and CD4 Cell Count among Persons with HIV Infection in Uganda,” AIDS & Behavior, Vol. 10, No. 4, 2006, pp. S105-111. doi:10.1007/s10461-006-9142-2 [29] D. J. Bwakali, “Gender Inequality in Africa: Contem- porary Review,” 2001. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m2242/is_1630_279/ ai_80607713

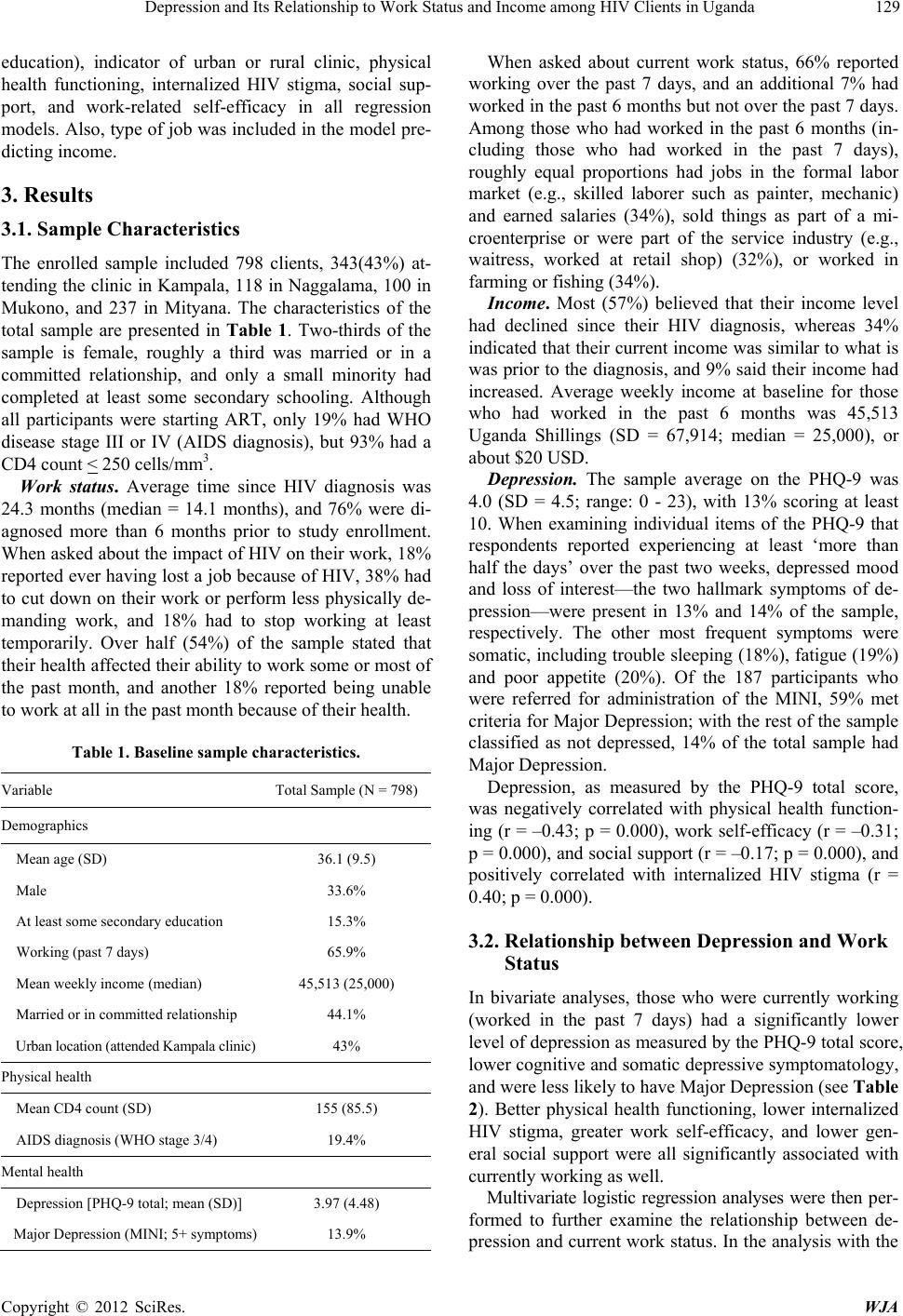

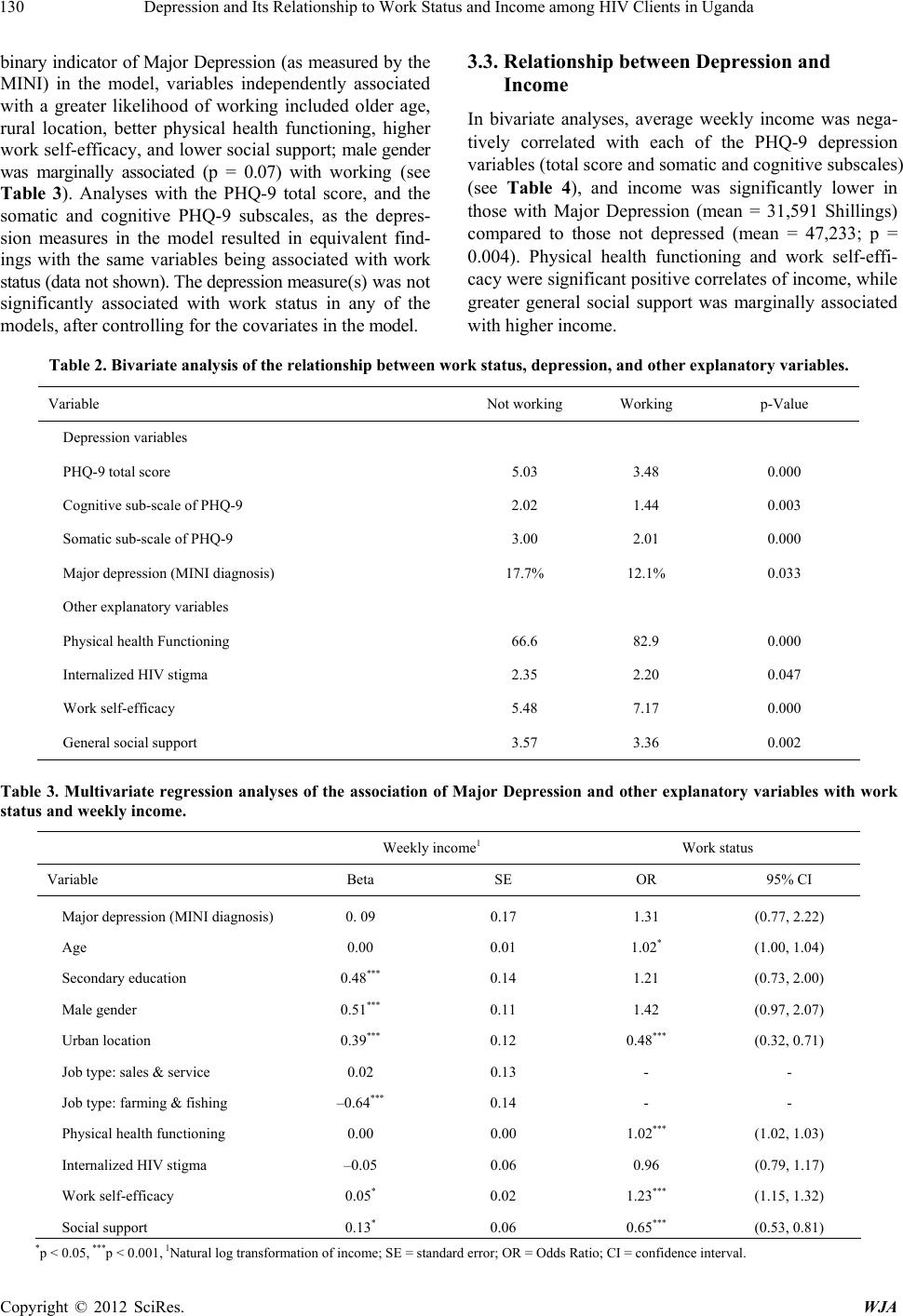

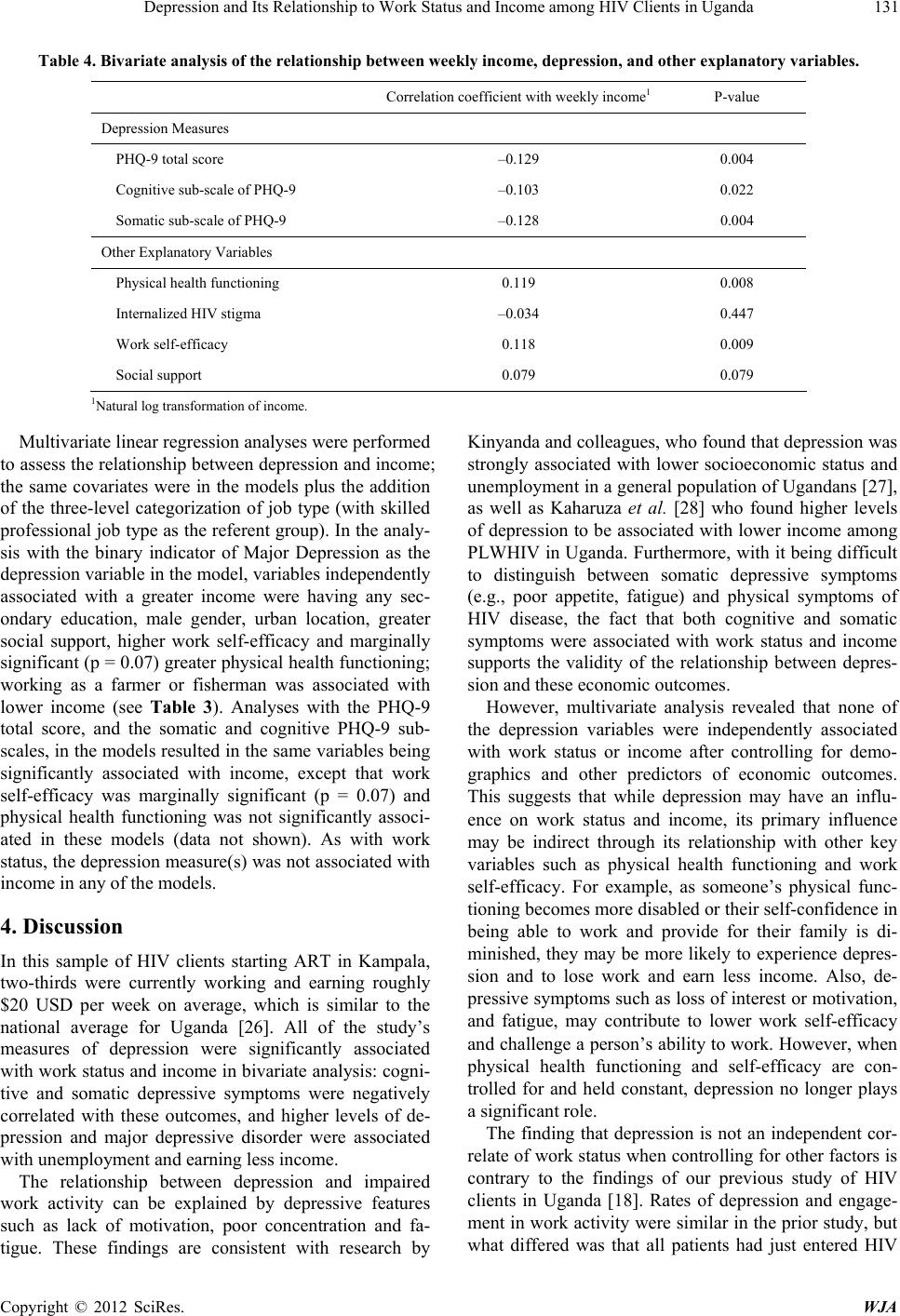

|