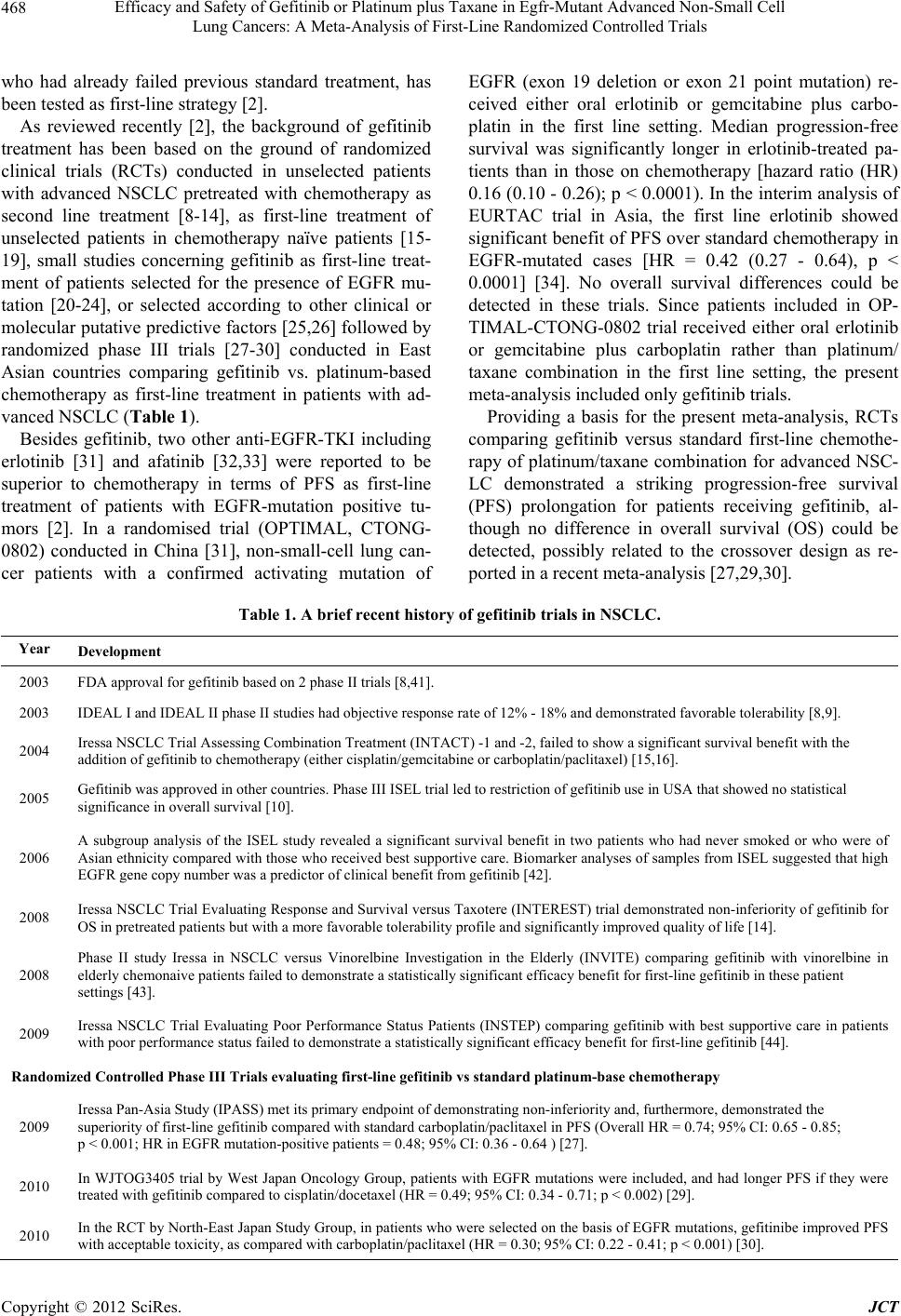

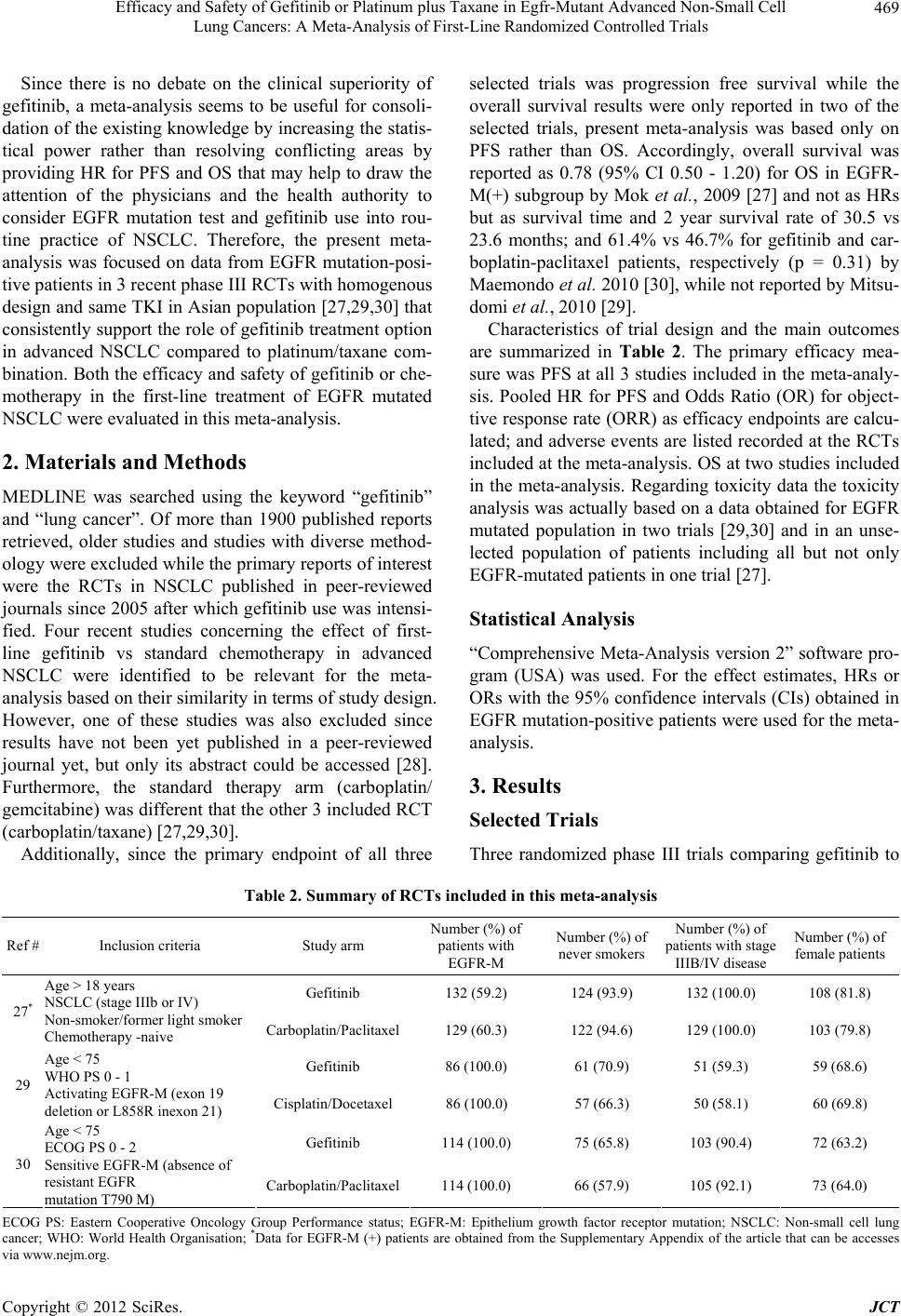

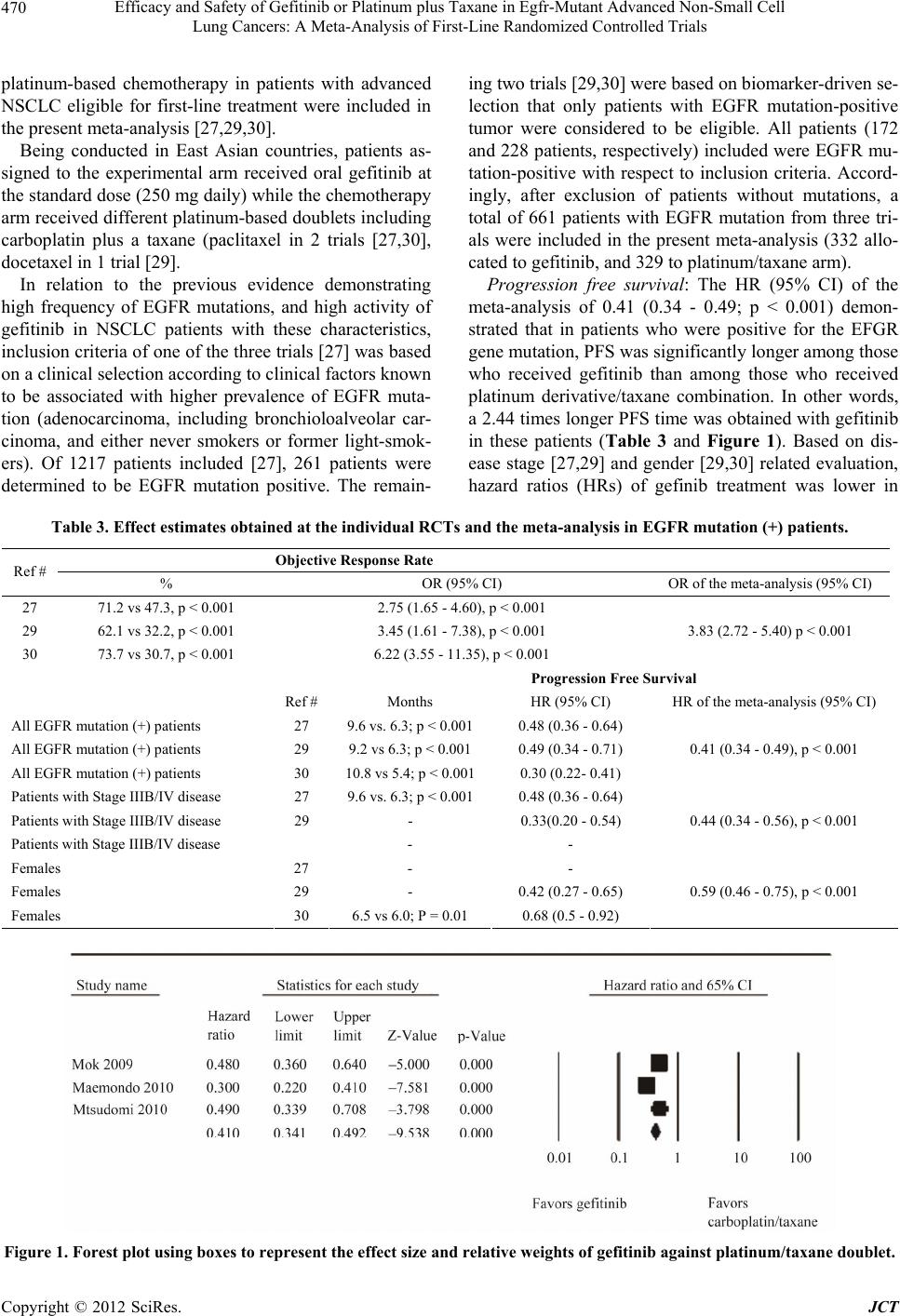

Journal of Cancer Therapy, 2012, 3, 467-476 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jct.2012.324060 Published Online September 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jct) 467 Efficacy and Safety of Gefitinib or Platinum plus Taxane in Egfr-Mutant Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers: A Meta-Analysis of First-Line Randomized Controlled Trials* Adnan Aydiner Istanbul University, Institute of Oncology, Istanbul, Turkey. Email: adnanaydiner@superonline.com Received February 13th, 2012; revised March 7th, 2012; accepted March 26th, 2012 ABSTRACT Purpose: The discovery of EGFR mutations renewed interest in lung cancer translational research since EGFR-depen- dent pathway plays an important role in the development and progression of human epithelial cancers, including non- small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The present meta-analysis was performed to review the recent advances with the se- lective oral EGFR-TK inhibitor gefitinib among EGFR mutation positive patients with NSCLC. Methods: Using the keywords “gefitinib” and “lung cancer” MEDLINE was searched. The primary reports of interest were the randomized controlled trials in NSCL published in peer-reviewed journals. Three recent studies concerning the effect of gefitinib in NSCLC were identified to be relevant for the meta-analysis based on their similarity in terms of study design. PFS and objective response rate (ORR) in gefitinib and platinum/taxane combination were compared by the Hazard ratio (HR) or Odds Ratio (OR) of meta-analysis. Results: The HR (95% CI) of the meta-analysis of 0.41 (0.34 - 0.49) demonstrated that in patients EFGR mutation positive patients, PFS was significantly longer among those who received gefitinib compared to platin derivative/taxane combination. Furthermore, OR of the meta-analysis for ORR was 3.83 (2.72 - 5.40). While hematological toxicity was observed in the majority of the taxane/platinum group, major adverse events in gefitinib patients were skin rashes/acnea, dry skin, elevated liver enzymes and diarrhea. Conclusion: This meta-analysis strongly confirms the efficacy and better tolerability of gefitinib in EGFR positive NSCLC, and the importance of EGFR mutation testing in order to plan first-line treatment in routine clinical practice in NSCLC. Keywords: Gefitinib; EGFR Mutation; Lung Cancer; Meta-Analysis 1. Introduction In recent years, various molecular targeted therapies have been developed for the treatment of advanced NSCLC in an attempt to improve prognosis. One such target has been the EGFR, which is frequently expressed at high levels in tumor tissue compared to the corresponding healthy tissue [1]. Accordingly, in the last decade, two small molecules, orally active, selective and reversible EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) gefitinib and erlotinib have been developed for the treatment of NSCLC [2]. In fact, increased demand to identify sub-sets of NSCLC patients to improve outcomes in this heteroge- neous disease having a median survival barely exceeding 12 months [3], great efforts in clinical and laboratory re- search in recent years led to a better knowledge of pre- dictive factors of the efficacy of EGFR-TKIs [4]. Identification of somatic mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of the EGFR in patients with NSCLC by three groups of investigators in 2004 [5-7] revealed al- most ubiquitous presence of these mutations in patients who had radiographic and clinical responses to gefitinib [4-6]. Accordingly, subsequent population-based efforts to sequence EGFR in NSCLC have consistently identified EGFR mutations in an enriched cohort of women, non- smokers, adenocarcinomas and East Asians including small inframe deletions around the conserved LREA mo- tif of exon 19 (residues 747 - 750), followed by a single point mutation in exon 21-L858R as the most prevalent EGFR mutations [4]. In particular, increasing evidence has been accumulated, supporting a strong predictive role of EGFR gene mutation in tumor cells. In parallel, EGFR inhibition strategy, that was originally limited to patients *Conflicts of interest: No conflicts of interest. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Efficacy and Safety of Gefitinib or Platinum plus Taxane in Egfr-Mutant Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers: A Meta-Analysis of First-Line Randomized Controlled Trials 468 who had already failed previous standard treatment, has been tested as first-line strategy [2]. As reviewed recently [2], the background of gefitinib treatment has been based on the ground of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) conducted in unselected patients with advanced NSCLC pretreated with chemotherapy as second line treatment [8-14], as first-line treatment of unselected patients in chemotherapy naïve patients [15- 19], small studies concerning gefitinib as first-line treat- ment of patients selected for the presence of EGFR mu- tation [20-24], or selected according to other clinical or molecular putative predictive factors [25,26] followed by randomized phase III trials [27-30] conducted in East Asian countries comparing gefitinib vs. platinum-based chemotherapy as first-line treatment in patients with ad- vanced NSCLC (Table 1). Besides gefitinib, two other anti-EGFR-TKI including erlotinib [31] and afatinib [32,33] were reported to be superior to chemotherapy in terms of PFS as first-line treatment of patients with EGFR-mutation positive tu- mors [2]. In a randomised trial (OPTIMAL, CTONG- 0802) conducted in China [31], non-small-cell lung can- cer patients with a confirmed activating mutation of EGFR (exon 19 deletion or exon 21 point mutation) re- ceived either oral erlotinib or gemcitabine plus carbo- platin in the first line setting. Median progression-free survival was significantly longer in erlotinib-treated pa- tients than in those on chemotherapy [hazard ratio (HR) 0.16 (0.10 - 0.26); p < 0.0001). In the interim analysis of EURTAC trial in Asia, the first line erlotinib showed significant benefit of PFS over standard chemotherapy in EGFR-mutated cases [HR = 0.42 (0.27 - 0.64), p < 0.0001] [34]. No overall survival differences could be detected in these trials. Since patients included in OP- TIMAL-CTONG-0802 trial received either oral erlotinib or gemcitabine plus carboplatin rather than platinum/ taxane combination in the first line setting, the present meta-analysis included only gefitinib trials. Providing a basis for the present meta-analysis, RCTs comparing gefitinib versus standard first-line chemothe- rapy of platinum/taxane combination for advanced NSC- LC demonstrated a striking progression-free survival (PFS) prolongation for patients receiving gefitinib, al- though no difference in overall survival (OS) could be detected, possibly related to the crossover design as re- ported in a recent meta-analysis [27,29,30]. Table 1. A brief recent history of gefitinib trials in NSCLC. Year Development 2003 FDA approval for gefitinib based on 2 phase II trials [8,41]. 2003 IDEAL I and IDEAL II phase II studies had objective response rate of 12% - 18% and demonstrated favorable tolerability [8,9]. 2004 Iressa NSCLC Trial Assessing Combination Treatment (INTACT) -1 and -2, failed to show a significant survival benefit with the addition of gefitinib to chemotherapy (either cisplatin/gemcitabine or carboplatin/paclitaxel) [15,16]. 2005 Gefitinib was approved in other countries. Phase III ISEL trial led to restriction of gefitinib use in USA that showed no statistical significance in overall survival [10]. 2006 A subgroup analysis of the ISEL study revealed a significant survival benefit in two patients who had never smoked or who were of Asian ethnicity compared with those who received best supportive care. Biomarker analyses of samples from ISEL suggested that high EGFR gene copy number was a predictor of clinical benefit from gefitinib [42]. 2008 Iressa NSCLC Trial Evaluating Response and Survival versus Taxotere (INTEREST) trial demonstrated non-inferiority of gefitinib for OS in pretreated patients but with a more favorable tolerability profile and significantly improved quality of life [14]. 2008 Phase II study Iressa in NSCLC versus Vinorelbine Investigation in the Elderly (INVITE) comparing gefitinib with vinorelbine in elderly chemonaive patients failed to demonstrate a statistically significant efficacy benefit for first-line gefitinib in these patient settings [43]. 2009 Iressa NSCLC Trial Evaluating Poor Performance Status Patients (INSTEP) comparing gefitinib with best supportive care in patients with poor performance status failed to demonstrate a statistically significant efficacy benefit for first-line gefitinib [44]. Randomized Controlled Phase III Trials evaluating first-line gefitinib vs standard platinum-base chemotherapy 2009 Iressa Pan-Asia Study (IPASS) met its primary endpoint of demonstrating non-inferiority and, furthermore, demonstrated the superiority of first-line gefitinib compared with standard carboplatin/paclitaxel in PFS (Overall HR = 0.74; 95% CI: 0.65 - 0.85; p < 0.001; HR in EGFR mutation-positive patients = 0.48; 95% CI: 0.36 - 0.64 ) [27]. 2010 In WJTOG3405 trial by West Japan Oncology Group, patients with EGFR mutations were included, and had longer PFS if they were treated with gefitinib compared to cisplatin/docetaxel (HR = 0.49; 95% CI: 0.34 - 0.71; p < 0.002) [29]. 2010 In the RCT by North-East Japan Study Group, in patients who were selected on the basis of EGFR mutations, gefitinibe improved PFS with acceptable toxicity, as compared with carboplatin/paclitaxel (HR = 0.30; 95% CI: 0.22 - 0.41; p < 0.001) [30]. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Efficacy and Safety of Gefitinib or Platinum plus Taxane in Egfr-Mutant Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers: A Meta-Analysis of First-Line Randomized Controlled Trials 469 Since there is no debate on the clinical superiority of gefitinib, a meta-analysis seems to be useful for consoli- dation of the existing knowledge by increasing the statis- tical power rather than resolving conflicting areas by providing HR for PFS and OS that may help to draw the attention of the physicians and the health authority to consider EGFR mutation test and gefitinib use into rou- tine practice of NSCLC. Therefore, the present meta- analysis was focused on data from EGFR mutation-posi- tive patients in 3 recent phase III RCTs with homogenous design and same TKI in Asian population [27,29,30] that consistently support the role of gefitinib treatment option in advanced NSCLC compared to platinum/taxane com- bination. Both the efficacy and safety of gefitinib or che- motherapy in the first-line treatment of EGFR mutated NSCLC were evaluated in this meta-analysis. 2. Materials and Methods MEDLINE was searched using the keyword “gefitinib” and “lung cancer”. Of more than 1900 published reports retrieved, older studies and studies with diverse method- ology were excluded while the primary reports of interest were the RCTs in NSCLC published in peer-reviewed journals since 2005 after which gefitinib use was intensi- fied. Four recent studies concerning the effect of first- line gefitinib vs standard chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC were identified to be relevant for the meta- analysis based on their similarity in terms of study design. However, one of these studies was also excluded since results have not been yet published in a peer-reviewed journal yet, but only its abstract could be accessed [28]. Furthermore, the standard therapy arm (carboplatin/ gemcitabine) was different that the other 3 included RCT (carboplatin/taxane) [27,29,30]. Additionally, since the primary endpoint of all three selected trials was progression free survival while the overall survival results were only reported in two of the selected trials, present meta-analysis was based only on PFS rather than OS. Accordingly, overall survival was reported as 0.78 (95% CI 0.50 - 1.20) for OS in EGFR- M(+) subgroup by Mok et al., 2009 [27] and not as HRs but as survival time and 2 year survival rate of 30.5 vs 23.6 months; and 61.4% vs 46.7% for gefitinib and car- boplatin-paclitaxel patients, respectively (p = 0.31) by Maemondo et al. 2010 [30], while not reported by Mitsu- domi et al., 2010 [29]. Characteristics of trial design and the main outcomes are summarized in Table 2. The primary efficacy mea- sure was PFS at all 3 studies included in the meta-analy- sis. Pooled HR for PFS and Odds Ratio (OR) for object- tive response rate (ORR) as efficacy endpoints are calcu- lated; and adverse events are listed recorded at the RCTs included at the meta-analysis. OS at two studies included in the meta-analysis. Regarding toxicity data the toxicity analysis was actually based on a data obtained for EGFR mutated population in two trials [29,30] and in an unse- lected population of patients including all but not only EGFR-mutated patients in one trial [27]. Statistical Analysis “Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 2” software pro- gram (USA) was used. For the effect estimates, HRs or ORs with the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) obtained in EGFR mutation-positive patients were used for the meta- analysis. 3. Results Selected Trials Three randomized phase III trials comparing gefitinib to Table 2. Summary of RCTs included in this meta-analysis Ref # Inclusion criteria Study arm Number (%) of patients with EGFR-M Number (%) of never smokers Number (%) of patients with stage IIIB/IV disease Number (%) of female patients Gefitinib 132 (59.2) 124 (93.9) 132 (100.0) 108 (81.8) 27* Age > 18 years NSCLC (stage IIIb or IV) Non-smoker/former light smoker Chemotherapy -naive Carboplatin/Paclitaxel 129 (60.3) 122 (94.6) 129 (100.0) 103 (79.8) Gefitinib 86 (100.0) 61 (70.9) 51 (59.3) 59 (68.6) 29 Age < 75 WHO PS 0 - 1 Activating EGFR-M (exon 19 deletion or L858R inexon 21) Cisplatin/Docetaxel 86 (100.0) 57 (66.3) 50 (58.1) 60 (69.8) Gefitinib 114 (100.0) 75 (65.8) 103 (90.4) 72 (63.2) 30 Age < 75 ECOG PS 0 - 2 Sensitive EGFR-M (absence of resistant EGFR mutation T790 M Carboplatin/Paclitaxel 114 (100.0) 66 (57.9) 105 (92.1) 73 (64.0) ECOG PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance status; EGFR-M: Epithelium growth factor receptor mutation; NSCLC: Non-small cell lung cancer; WHO: World Health Organisation; *Data for EGFR-M (+) patients are obtained from the Supplementary Appendix of the article that can be accesses via www.nejm.org. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Efficacy and Safety of Gefitinib or Platinum plus Taxane in Egfr-Mutant Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers: A Meta-Analysis of First-Line Randomized Controlled Trials 470 platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC eligible for first-line treatment were included in the present meta-analysis [27,29,30]. Being conducted in East Asian countries, patients as- signed to the experimental arm received oral gefitinib at the standard dose (250 mg daily) while the chemotherapy arm received different platinum-based doublets including carboplatin plus a taxane (paclitaxel in 2 trials [27,30], docetaxel in 1 trial [29]. In relation to the previous evidence demonstrating high frequency of EGFR mutations, and high activity of gefitinib in NSCLC patients with these characteristics, inclusion criteria of one of the three trials [27] was based on a clinical selection according to clinical factors known to be associated with higher prevalence of EGFR muta- tion (adenocarcinoma, including bronchioloalveolar car- cinoma, and either never smokers or former light-smok- ers). Of 1217 patients included [27], 261 patients were determined to be EGFR mutation positive. The remain- ing two trials [29,30] were based on biomarker-driven se- lection that only patients with EGFR mutation-positive tumor were considered to be eligible. All patients (172 and 228 patients, respectively) included were EGFR mu- tation-positive with respect to inclusion criteria. Accord- ingly, after exclusion of patients without mutations, a total of 661 patients with EGFR mutation from three tri- als were included in the present meta-analysis (332 allo- cated to gefitinib, and 329 to platinum/taxane arm). Progression free survival: The HR (95% CI) of the meta-analysis of 0.41 (0.34 - 0.49; p < 0.001) demon- strated that in patients who were positive for the EFGR gene mutation, PFS was significantly longer among those who received gefitinib than among those who received platinum derivative/taxane combination. In other words, a 2.44 times longer PFS time was obtained with gefitinib in these patients (Table 3 and Figure 1). Based on dis- ease stage [27,29] and gender [29,30] related evaluation, hazard ratios (HRs) of gefinib treatment was lower in Table 3. Effect estimates obtained at the individual RCTs and the meta-analysis in EGFR mutation (+) patients. Objective Response Rate Ref # % OR (95% CI) OR of the meta-analysis (95% CI) 27 71.2 vs 47.3, p < 0.001 2.75 (1.65 - 4.60), p < 0.001 29 62.1 vs 32.2, p < 0.001 3.45 (1.61 - 7.38), p < 0.001 30 73.7 vs 30.7, p < 0.001 6.22 (3.55 - 11.35), p < 0.001 3.83 (2.72 - 5.40) p < 0.001 Progression Free Survival Ref # Months HR (95% CI) HR of the meta-analysis (95% CI) All EGFR mutation (+) patients 27 9.6 vs. 6.3; p < 0.001 0.48 (0.36 - 0.64) All EGFR mutation (+) patients 29 9.2 vs 6.3; p < 0.001 0.49 (0.34 - 0.71) All EGFR mutation (+) patients 30 10.8 vs 5.4; p < 0.001 0.30 (0.22- 0.41) 0.41 (0.34 - 0.49), p < 0.001 Patients with Stage IIIB/IV disease 27 9.6 vs. 6.3; p < 0.001 0.48 (0.36 - 0.64) Patients with Stage IIIB/IV disease 29 - 0.33(0.20 - 0.54) Patients with Stage IIIB/IV disease - - 0.44 (0.34 - 0.56), p < 0.001 Females 27 - - Females 29 - 0.42 (0.27 - 0.65) Females 30 6.5 vs 6.0; P = 0.01 0.68 (0.5 - 0.92) 0.59 (0.46 - 0.75), p < 0.001 Figure 1. Forest plot using boxes to represent the effect size and relative weights of gefitinib against platinum/taxane doublet. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Efficacy and Safety of Gefitinib or Platinum plus Taxane in Egfr-Mutant Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers: A Meta-Analysis of First-Line Randomized Controlled Trials 471 patients with Stage III/IV patients (HR = 0.44 (0.34; 0.56; p < 0.001) and in females (HR = 0.59 (0.46; 0.75; p < 0.001) (Table 3). Nonetheless, no gender comparison was reported in the trial by Mok et al. 2009 [27] include- ing patients in stage IIIb/IV, while no disease stage comparison was evident in the trial by Maemondo et al., 2010 [30] which stated that women had significantly longer PFS than men (median 6.5 vs 6.0 months) whereas HRs for PFS for gefitinib vs chemotherapy in males was not provided. HR for PFS in early stage (post-op) group was 0.57 (95% CI 0.31 - 1.05), in stage IIIb/IV group was 0.33 (95% CI 0.20 - 0.54) in the trial by Mitsudomi et al., 2010 [29] which stated HR for PFS in males to be 0.67 (95% CI 0.34 - 1.33) and in females to be 0.42 (95% CI 0.27 - 0.65). Objective Response Rate: The OR (95% CI) for the ORR of the meta-analysis of 3.83 (2.72 - 5.40; p < 0.001) in patients who were positive for the EFGR gene muta- tion (Table 3). Safety: The safety results of the individual RCTs showed that hematological toxicity, fatigue, nausea and alopecia were the most frequent adverse events in the taxane/platinum group, while major adverse events in gefitinib patients were skin rashes/acnea, dry skin, ele- vated liver enzymes and diarrhea (Tables 4 and 5). 4. Discussion The present meta-analysis provides the magnitude of benefit obtained with the EGFR-TKI gefitinib when used as front-line treatment in advanced, EGFR-M+, NSCLC patients. The HR obtained with this meta-analysis more strongly supports the efficacy of gefitinib, and stresses on the importance of EGFR mutation test and gefitinib use in routine practice of NSCLC safely. Report of EGFR mutations in exons 19 or 21 amongst patients responding to gefitinib, as compared to no muta- tion found in non-responders [5-7,35] triggered studies Table 4. Adverse events observed at the individual randomized controlled trials included in this meta-analysis. Gefitinib (n (%)) Platinum/Taxane (n (%)) Ref [27] (n = 607)Ref [29] (n = 87) Ref [30] (n = 114)Ref [27] (n=589) Ref [29] (n = 88) Ref [30] (n = 113) Adverse event All CTC grade ≥ 3 All CTC grade ≥ 3All CTC grade ≥ 3All CTC grade ≥ 3All CTC grade ≥ 3 All CTC grade ≥ 3 Non-hematological toxicity Rash or acne 402 (66.2) 19 (3.1) 74 (85.1)* 2 (2.3)81 (71.1)6 (5.3)132 (22.4)5 (0.8) 7 (79.5) 0 (0.0) 25 (22.1)3 (2.7) AST NA NA 61 (70.1)* 14 (16.1)63 (55.3)30 (26.3)NA NA 17 (19.3) 1 (1.1) 37 (32.7)1 (0.9) ALT NA NA 61 (70.1)* 24 (27.6)NA NA NA NA 35 (39.8) 2 (2.3) NA NA Dry skin 145 (23.9) 0 (0.0)47 (54.0)* 0 (0.0)NA NA 17 (2.9)0 (0.0) 3 (34.1) 0 (0.0) NA NA Diarrhea 283 (46.6) 23 (3.8) 47 (54.0) 1 (1.1)39 (34.2)1 (0.9)128 (21.7)8 (1.4) 35 (39.8) 0 (0.0) 7 (6.2)0 (0.0) Fatigue NA NA 34 (39.1)* 2 (2.3)12 (10.5)3 (2.6)NA NA 73 (83.0) 2 (2.3) 31 (27.4)1 (0.9) Paronychia 82813.5) 2 (0.3)28 (32.2)* 1 (1.1)NA NA 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 1 (1.1) 0 (0.0) NA NA Stomatitis 103 (17.0) 1 (0.2)19 (21.8) 0 (0.0)NA NA 51 (8.7)1 (0.2) 13 (14.8) 0 (0.0) NA NA Nausea 101 (16.6) 2 (0.3)15 (17.2)* 1 (1.1)NA NA 261 (44.3)9 (1.5) 83 (94.3) 3 (3.4) NA NA Vomiting 78 (12.9) 1 (0.2)NA NA NA NA 196 (33.3)16 (2.7)NA NA NA NA Constipation 73 (12.0) 0 (0.0)14 (16.1)* 0 (0.0)NA NA 173 (29.4)1 (0.2) 39 (44.3) 0 (0.0) NA NA Anorexia 133 (21.9) 9 (1.5)NA NA 17 (14.9)6 (5.3)251 (41.6)16 (2.7)NA NA 64 (56.6)7 (6.2) Pruritus 118 (19.4) 4 (0.7)NA NA NA NA 74 (12.6)1 (0.2) NA NA NA NA Alopecia 67 (11.0) 0 (0.0)8 (9.2)* 0 (0.0)NA NA 344 (58.4)0 (0.0) 67 (76.1) 0 (0.0) NA NA Arthralgia 39 (6.4) 1 (0.2)NA NA 3 (26.3)1 (0.9)113 (19.2)6 (1.0) NA NA 54 (47.8)8 (7.1) Neuropathy 66 (10.9) 2 (0.3)7 (8.0)* 1 (1.1)1 (0.8)0 (0.0)NA NA 23 (26.1) 0 (0.0) 63 (55.8)7 (6.2) Hematological toxicity Leucopenia NA 9(1.5)13(14.9)* 0(0.0)NA NA NA 202(35.0)82(93.2) 43(48.9) NA NA Thrombocytopenia NA NA 12(13.8)* 0(0.0)8(7.0)0(0.0)NA NA 29(33.0) 0(0.0) 32(28.3)4(3.5) Neutropenia NA 22(3.7)7(8.0)* 0(0.0)7(6.1)1(0.9)NA 387(67.1)81(92.0) 74(84.1) 87(77.0)74(65.5) Anemia NA 13(2.2)33(37.9)* 0(0.0)21(18.4)0(0.0)NA 61(10.6)79(89.8) 15(17.0) 73(64.6)6(5.3) ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; CTC: National Cancer Institute Common Tehcnology Criteria, *p < 0.001 compared to plati- num/taxane group; NA: not available. Events are included if they occurred in at least 10% of patients in each treatment group. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Efficacy and Safety of Gefitinib or Platinum plus Taxane in Egfr-Mutant Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers: A Meta-Analysis of First-Line Randomized Controlled Trials 472 Table 5. Odds ratios of the meta-analysis for all grades of adverse events in gefitinib vs platinum/taxane treated patients. Odds ratio %95 Confidence interval p Non-hematological toxicity Rash or acne 7.98 6.35 - 10.04 <0.001 AST 4.19 2.74 - 6.43 <0.001 Dry skin 12.56 7.80 - 20.23 <0.001 Diarrhea 3.09 2.47 - 3.87 <0.001 Fatigue 0.20 0.12 - 0.33 <0.001 Paronychia 30.52 5.86 - 158.92 <0.001 Stomatitis 2.05 1.48 - 2.84 <0.001 Nausea 0.21 0.16 - 0.27 <0.001 Constipation 0.31 0.24 - 0.41 <0.001 Anorexia 0.33 0.26 - 0.42 <0.001 Alopecia 0.08 0.06 - 0.11 <0.001 Arthralgia 0.28 0.20 - 0.40 <0.001 Neuropathy 0.47 0.35 - 0.64 <0.001 Hematological toxicity Thrombocytopenia 0.26 0.15 - 0.45 <0.001 Neutropenia 0.01 0.01 - 0.03 <0.001 Anemia 0.10 0.06 - 0.16 <0.001 ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; CTC: National Cancer Institute Common Tehcnology Criteria *p < 0.001 compared to plati- num/taxane group. that provided preliminary evidence about predictive fac- tors of gefitinib efficacy. Accordingly the frequency of somatic mutations within the tyrosine kinase domain of the EGFR gene was shown to be low in unselected Western patients with advanced NSCLC, but, interest- ingly, these mutations appeared to be much more fre- quent in Japanese and East Asian population [2]. Fur- thermore, it was rapidly evident that some clinical or pathological characteristics are associated with higher prevalence of mutation: in detail, EGFR mutation is more frequent in never smokers, in women, and in patients with adenocarcinoma [2]. Based on this evidence, several small trials were conducted testing gefitinib as first-line treatment of patients selected for the presence of EGFR mutation [20-24], or selected according to other clinical or molecular putative predictive factors [25,26] followed by randomized phase III trials [27-30] conducted in East Asian countries comparing gefitinib vs. platinum-based chemotherapy as first-line treatment in patients with ad- vanced NSCLC. Accordingly, indicating a high-level evidence, coming from four prospective, randomized phase III trials [27- 30], two of which were conducted specifically in patients with tumor harbouring EGFR mutation [29,30], in pa- tients with advanced NSCLC selected for the presence of EGFR mutation, the administration of first-line gefitinib, compared to standard platinum-based chemotherapy seems to be associated with longer PFS, higher ORR, a more favorable toxicity profile and better quality of life. Likewise, an estimate of the magnitude of benefit was reported with EGFR-TKI (gefitinib and erlotinib) in a recent meta-analysis, when used as front-line treatment in advanced, EGFR-M+, NSCLC patients. In this setting, EGFR-TKI has been considered to provide an unusually large PFS benefit when compared with cytotoxic che- motherapy, with an absolute reduction in the risk of pro- gression of 22% - 30% as well as an advantage achieved in terms of ORR [36]. As a matter of fact, the results of the recent meta- analysis [36] indicated the significant role of attrition in the observed magnitude of benefit of a “targeted” treat- ment strategy that as the rate of patients analyzed or positive for sensitizing EGFR mutation increases (and thus the attrition rate decreases), the HR in favor of the EGFR-TKI decreases. When the attrition is relatively low (e.g. the Asian “clinically enriched” population of the two retrospective front-line trials [27,28], a non-molecular selection strategy may still be able to detect some de- gree of benefit for EGFR-TKI in the target population. Conversely, when the attrition bias is high (e.g. in mostly Caucasian patient populations where the rate of EGFR mutations is expected to be <10%), not only may a po- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Efficacy and Safety of Gefitinib or Platinum plus Taxane in Egfr-Mutant Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers: A Meta-Analysis of First-Line Randomized Controlled Trials 473 tential benefit for EGFR-M+ patients be easily missed using a non selection strategy but we can also incur in the risk of exposing patients to a significantly detrimental effect, as observed in the Tarceva OR CHemotherapy trial [37], comparing erlotinib with standard chemothe- rapy as front-line treatment of unselected, advanced NSCLC patients [36]. Concerning toxicity, gefitinib appears to be well toler- ated when administered as first-line treatment of patients with advanced NSCLC. Notably, in the IPASS trial [27], gefitinib was associated with a lower rate of severe ad- verse events (defined as grade 3 or 4 according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, 28.7% vs 61.0% for gefitinib and chemotherapy, respec- tively). Differing substantially from toxicity reported, gefitinib was associated with better tolerance in all randomized trials comparing first-line gefitinib to platinum-based chemotherapy [27-30]. Although the most common ad- verse events in patients receiving gefitinib were cutane- ous toxicity (skin rash, dry skin), diarrhea and liver dys- function usually consisting in asymptomatic hypertrans- aminasemia, patients assigned to gefitinib arm suffered significantly less hematological toxicity, emesis, fatigue, neurotoxicity, constipation and hair loss, compared to patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. In particular, as reviewed recently [2], lower rate of severe adverse events (defined as grade 3 or 4 according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, 28.7% vs 61.0% for gefitinib and chemotherapy, respec- tively, a lower rate of adverse events leading to discon- tinuation of the drug (6.9% vs 13.6%) and a lower rate of dose modification due to toxic effects (16.1% for ge- fitinib vs 35.2% for carboplatin and 37.5% for paclitaxel) were reported in IPASS trial [27]. Likewise, in the NEJ002 trial [32], gefitinib confirmed a significantly lower incidence of severe toxic effects compared to car- boplatin plus paclitaxel (41.2% vs 71.7%, p < 0.001). Among potentially life-threatening events described with the use of gefitinib, interstitial lung disease (ILD) was relatively uncommon. As described recently [2], it was identified in 16 patients (2.6%) in the IPASS trial [27], 2 patients (2.3%) in the WJTOG3405 trial [29], 6 patients (5.3%) in the NEJ002 trial [30]. Five of these 24 cases were lethal, and further 2 lethal cases of ILD were described in the 159 patients treated with gefitinib in the First-SIGNAL trial [28], leading to a total of 7 lethal ILD toxicities in the 967 patients overall evaluated in the 4 trials (0.7%). In this regard, identification of sensitizing EGFR mu- tations as the preferential molecular target of EGFR-TKI was reported to be crucial to get impressive benefit achieved with EGFR-TKI over classical cytotoxic che- motherapy if compared with the benefit of chemotherapy versus best supportive care in the same setting [38,39]. Importantly, this benefit was not gained at the expense of an increased toxicity rate; hematological toxic effects were significantly decreased in patients receiving gefit- inib, thus further increasing the therapeutic index of such a targeted approach. When a composite measurement of both efficacy and toxicity is used, an EGFR M+ patient was reported to be at least 67 times more likely to derive clinical benefit than to be harmed by upfront treatment with an EGFR-TKI rather than chemotherapy [36]. Whilst representing the strongest endpoint for clinical research in oncology, none of these randomized trials demonstrated a statistically significant improvement with gefitinib in terms of OS. Indeed, differences in OS were reported to be potentially conditioned by cross-over, and a relevant number of patients assigned to chemotherapy arm received an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (gefit- inib or erlotinib) as second or third-line treatment after disease progression [2]. As the number of trials is small (n = 3), the limitations of the trials with respect to patient populations (all patients are from Asia) are important. How this may or may not impact generalization to West- ern countries is not clear. Moreover, in a series of West- ern patients with EGFR mutation positive NSCLC, treated with erlotinib, similar OS was reported for pa- tients receiving the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor as first-line or as second-line (median OS was 28.0 months and 27.0 months, respectively) [40]. 5. Conclusion In patients with advanced NSCLC selected for the pre- sence of EGFR mutation, the administration of first-line gefitinib, compared to standard platinum-based chemo- therapy, is associated with longer PFS, higher ORR. The current meta-analysis does not provide any data on better tolerability of gefitinib compared to chemotherapy be- cause of different toxicity observed between two treat- ment modalities. Since no data on EGFR M-negative patients has been included in the meta-analysis the con- clusion on the importance of EGFR mutation testing in order to plan first-line therapy cannot be drawn from the presented work, even though it is correct. Accordingly, the HR and also OR for the ORR obtained within this meta-analysis supports the efficacy of gefitinib strongly, and as a superior medical evidence that may help to draw the attention of the physicians and the health authority, stresses on the importance of the identification of EGFR mutation test as well as gefitinib use in routine practice of NSCLC which is characterized by significant hetero- geneity, premonitory for the likelihood of deriving sub- stantial therapeutic benefit. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Efficacy and Safety of Gefitinib or Platinum plus Taxane in Egfr-Mutant Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers: A Meta-Analysis of First-Line Randomized Controlled Trials 474 6. Acknowledgements I would like to thank to Sule Oktay, MD, PhD and Cagla Isman, MD for editorial support and Onder Ergonul, MD for consultancy in statistical analysis. REFERENCES [1] M. Reck, “A Major Step towards Individualized Therapy of Lung Cancer with Gefitinib: The IPASS Trial and Be- yond,” Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy, Vol. 10, No. 6, 2010, pp. 955-965. doi:10.1586/era.10.63 [2] C. Gridelli, F. De Marinis, M. Di Maio, et al., “Gefitinib as First-Line Treatment for Patients with Advanced Non- Small-Cell Lung Cancer with Activating Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutation: Review of the Evi- dence,” Lung Cancer, Vol. 71, No. 3, 2011, pp. 249-257. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.12.008 [3] A. Sandler, R. Gray, M. C. Perry, et al., “Paclitaxel- Carboplatin Alone or with Bevacizumab for Non-Small- Cell Lung Cancer,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 355, No. 24, 2006, pp. 2542-2550. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa061884 [4] D. B. Costa, S. Kobayashi, D. G. Tenen, et al., “Pooled Analysis of the Prospective Trials of Gefitinib Monother- apy for EGFR-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers,” Lung Cancer, Vol. 58, No. 1, 2007, pp. 95-103. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.05.017 [5] T. J. Lynch, D. W. Bell, R. Sordella, et al., “Activating Mutations in the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Un- derlying Responsiveness of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer to Gefitinib,” The New England Journal of M edi cin e, Vol. 350, No. 21, 2004, pp. 2129-2139. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa040938 [6] J. G. Paez, P. A. Janne, J. C. Lee, et al., “EGFR Mutations in Lung Cancer: Correlation with Clinical Response to Gefitinib Therapy,” Science, Vol. 304, No. 5676, 2004, pp. 1497-1500. doi:10.1126/science.1099314 [7] W. Pao, V. Miller, M. Zakowski, et al., “EGF Receptor Gene Mutations Are Common in Lung Cancers from ‘Never Smokers’ and Are Associated with Sensitivity of Tumors to Gefitinib and Erlotinib,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, Vol. 101, 2004, pp. 13306-13311. doi:10.1073/pnas.0405220101 [8] M. Fukuoka, S. Yano, G. Giaccone, et al., “Multi-Institu- Tional Randomized Phase II Trial of Gefitinib for Previ- ously Treated Patients with Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 21, No. 12, 2003, pp. 2237-2246. doi:10.1200/JCO.2003.10.038 [9] M. G. Kris, R. B. Natale, R. S. Herbst, et al., “Efficacy of Gefitinib, an Inhibitor of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Tyrosine Kinase, in Symptomatic Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Randomized Trial,” JAMA, Vol. 290, No. 16, 2003, pp. 2149-2158. doi:10.1001/jama.290.16.2149 [10] N. Thatcher, A. Chang, P. Parikh, et al. “Gefitinib plus Best Supportive Care in Previously Treated Patients with Refractory Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Re- sults from a Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Multicen- tre Study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung cancer),” Lancet, Vol. 366, No. 9496, 2005, pp. 1527-1537. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8 [11] T. Cufer, E. Vrdoljak, R. Gaafar, et al., “Phase II, Open- Label, Randomized Study (SIGN) of Single-Agent Gefit- inib (IRESSA) or Docetaxel as Second-Line Therapy in Patients with Advanced (Stage IIIb or IV) Non-Small- Cell Lung Cancer,” Anticancer Drugs, Vol. 17, No. 4, 2006, pp. 401-409. doi:10.1097/01.cad.0000203381.99490.ab [12] D. Lee, S. Kim, K. Park, et al., “A Randomized Open- Label Study of Gefitinib versus Docetaxel in Patients with Advanced/Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Who Have Previously Received Platinum- Based Chemotherapy,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 26, No. 15S, 2008, Abstract 8025. [13] R. Maruyama, Y. Nishiwaki, T. Tamura, et al., “Phase III Study, V-15-32, of Gefitinib versus Docetaxel in Previ- ously Treated Japanese Patients with Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol 26, No. 26, 2008, pp. 4244-4252. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0185 [14] E. S. Kim, V. Hirsh, T. Mok, et al., “Gefitinib versus Docetaxel in Previously Treated Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (INTEREST): A Randomised Phase III Trial,” Lancet, Vol. 372, No. 9652, 2008, pp. 1809-1818. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61758-4 [15] G. Giaccone, R. S. Herbst, C. Manegold, et al., “Gefitinib in Combination with Gemcitabine and Cisplatin in Ad- vanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Phase III Trial— INTACT 1,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 22, 2004, pp. 777-784. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.08.001 [16] R. S. Herbst, G. Giaccone, J. H. Schiller, et al., “Gefitinib in Combination with Paclitaxel and Carboplatin in Ad- vanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Phase III Trial— INTACT 2,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 22, 2004, pp. 785-794. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.07.215 [17] M. Reck, E. Buchholz, K. S. Romer, et al., “Gefitinib Monotherapy in Chemotherapy-Naive Patients with Inop- erable Stage III/IV Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer,” Clini- cal Lung Cancer, Vol. 7, No. 6, 2006, pp. 406-411. doi:10.3816/CLC.2006.n.025 [18] S. Niho, K. Kubota, K. Goto, et al., “First-Line Single Agent Treatment with Gefitinib in Patients with Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Phase II Study,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 24, No. 1, 2006, pp. 64-69. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.02.5825 [19] L. Crinò, F. Cappuzzo, P. Zatloukal, et al., “Gefitinib versus Vinorelbine in Chemotherapy-Naive Elderly Pa- tients with Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (IN- VITE): A Randomized, Phase II Study,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 26, 2008, 4253-4260. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0672 [20] H. Asahina, K. Yamazaki, I. Kinoshita, et al., “A Phase II Trial of Gefitinib as First-Line Therapy for Advanced Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer with Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutations,” British Journal of Cancer, Vol. 95, No. 8, 2006, pp. 998-1004. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Efficacy and Safety of Gefitinib or Platinum plus Taxane in Egfr-Mutant Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers: A Meta-Analysis of First-Line Randomized Controlled Trials 475 doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603393 [21] A. Inoue, T. Suzuki, T. Fukuhara, et al., “Prospective Phase II Study of Gefitinib for Chemotherapy-Naïve Pa- tients with Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer with Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Gene Mutations,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 24, No. 21, 2006, pp. 3340-3346. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4692 [22] A. Sutani, Y. Nagai, K. Udagawa, et al., “Gefitinib for Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients with Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Gene Mutations Screened by Peptide Nucleic Acid-Locked Nucleic Acid PCR Clamp,” British Journal of Cancer, Vol. 95, 2006, pp. 1483-1489. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603466 [23] K. Tamura, I. Okamoto, T. Kashii, et al., “Multicentre Prospective Phase II Trial of Gefitinib for Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer with Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutations: Results of the West Japan Thoracic Oncology Group trial (WJTOG0403),” British Journal of Cancer, Vol. 98, 2008, 907-914. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604249 [24] L. V. Sequist, R. G. Martins, D. Spigel, et al., “Firstline Gefitinib in Patients with Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Harboring Somatic EGFR Mutations,” Jour- nal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 26, 2008, pp. 2442- 2449. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8494 [25] D. H. Lee, J. Y. Han, S. Y. Yu, et al., “The Role of Ge- fitinib Treatment for Korean Never-Smokers with Ad- vanced or Metastatic Adenocarcinoma of the Lung: A Prospective Study,” Journal of Thoracic Oncology, Vol. 1, 2006, pp. 965-971. doi:10.1097/01243894-200611000-00008 [26] F. Cappuzzo, C. Ligorio, P. A. Jänne, et al., “Prospective Study of Gefitinib in Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization Positive/Phospho-Akt- Positive or Never Smoker Patients with Advanced Non- Small-Cell Lung Cancer: The ONCOBELL Trial,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 25, No. 16, 2007, pp. 2248- 2255. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.09.4300 [27] T. S. Mok, Y. L. Wu, S. Thongprasert, et al., “Gefitinib or Carboplatin-Paclitaxel in Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 361, No. 10, 2009, pp. 947-957. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810699 [28] J. S. Lee, K. Park, S. Kim, et al., “A Randomized Phase III Study of Gefitinib (IRESSATM) versus Standard Che- motherapy (Gemcitabine Plus Cisplatin) as First-Line Treatment for Never Skmokers with Advanced or Metas- tatic Adenocarcinoma of the Lung,” Journal of Thoracic Oncology, Vol. 4, No. 9, 2009, p. S283. [29] T. Mitsudomi, S. Morita, Y. Yatabe, et al., “Gefitinib versus Cisplatin Plus Docetaxel in Patients with Non- Small-Cell Lung Cancer Harbouring Mutations of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (WJTOG3405): An Open Label, Randomised Phase 3 Trial,” Lancet Oncol- ogy, Vol. 11, 2010, pp. 121-128. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X [30] M. Maemondo, A. Inoue, K. Kobayashi, et al., “Gefitinib or Chemotherapy for Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer with Mutated EGFR,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 362, No. 25, 2010, pp. 2380-2388. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0909530 [31] C. Zhou, Y. L. Wu, G. Chen, et al., “Erlotinib versus Chemotherapy as First-Line Treatment for Patients with Advanced EGFR Mutation-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): A Multicentre, Open- Label, Randomised, Phase 3 Study,” Lancet On- cology, Vol. 12, No. 8, 2011, pp. 735-742. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X [32] V. A. Miller, V. Hirsh, J. Cadranel, et al., “Phase IIb/III Double-Blind Randomized Trial of BIBW 2992, an Irre- versible Inhibitor of EGFR/HER1 and HER2 + Best Supportive Care (BSC) versus Placebo + BSC in Patients with NSCLC Failing 1-2 Lines of Chemotherapy and Er- lotinib or Gefitinib (LUX-Lung 1),” European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress, Milan, 8-12 Octo- ber 2010, Abstract LBA1. [33] C. Yang, J. Shih, W. Su, et al., “A Phase II Study of BIBW 2992 in Patients with Adenocarcinoma of the Lung and Activating EGFR Mutations (LUX-Lung 2),” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 28, No. 15s, 2010, Abstract 7521. [34] R. Rosell, R. Gervais, A. Vergnenegre, et al., “Erlotinib versus Chemotherapy (CT) in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Patients (p) with Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Mutations: Interim Re- sults of the European Erlotinib versus Chemotherapy (EURTAC) Phase III Randomized Trial,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 29, 2011, Abstract 7503. [35] S. F. Huang, H. P. Liu, L. H. Li, et al., “High Frequency of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutations with Complex Patterns in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers Re- lated to Gefitinib Responsiveness in Taiwan,” Clinical Cancer Research, Vol. 10, 2004, pp. 8195-8203. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1245 [36] Y. L. Wu, W. Z. Zhong, L. Y. Li, et al., “Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutations and Their Correlation with Gefitinib Therapy in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis Based on Updated Indi- vidual Patient Data from Six Medical Centers in Main- land China,” Journal of Thoracic Oncology, Vol. 2, No. 5, 2007, pp. 430-439. doi:10.1097/01.JTO.0000268677.87496.4c [37] C. Gridelli, F. Ciardiello, R. Feld, et al., “International Multicenter Randomized Phase III Study of First-Line Erlotinib (E) Followed by Second-Line Cisplatin Plus Gemcitabine (CG) versus First-Line CG followed by Second-Line E in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (aNSCLC): The TORCH Trial,” Journal of Clinical On- cology, Vol. 28, No. 15s, 2010, Abstract 7508. [38] S. V. Sharma, D. W. Bell, J. Settleman, et al., “Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutations in Lung Cancer,” Nature Reviews Cancer, Vol. 7, No. 3, 2007, pp. 169-181. doi:10.1038/nrc2088 [39] H. Linardou, I. J. Dahabreh, D. Bafaloukos, et al., “So- matic EGFR Mutations and Efficacy of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in NSCLC,” Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, Vol. 6, No. 6, 2009, pp. 352-366. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT  Efficacy and Safety of Gefitinib or Platinum plus Taxane in Egfr-Mutant Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers: A Meta-Analysis of First-Line Randomized Controlled Trials Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JCT 476 doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.62 [40] R. Rosell, T. Moran, C. Queralt, et al., “Screening for Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutations in Lung Cancer,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 361, No. 10, 2009, pp. 958-967. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0904554 [41] M. H. Cohen, G. A. Williams, R. Sridhara, et al., “United States Food and Drug Administration Drug Approval Summary: Gefitinib (ZD1839, Iressa) Tablets,” Clinical Cancer Research, Vol. 10, 2004, pp. 1212-1218. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0564 [42] F. R. Hirsch, M. Varella-Garcia, P. A. Bunn Jr., et al., “Molecular Predictors of Outcome with Gefitinib in a Phase III Placebo-Controlled Study in Advanced Non- Small-Cell Lung Cancer,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 24, 2006, pp. 5034-5042. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.06.3958 [43] L. Crino, F. Cappuzzo, P. Zatloukal, et al., “Gefitinib versus Vinorelbine in Chemotherapy-Naive Elderly Pa- tients with Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (IN- VITE): A Randomized, Phase II Study,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 26, 2008, pp. 4253-4260. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0672 [44] G. Goss, D. Ferry, R. Wierzbicki, et al., “Randomized Phase II Study of Gefitinib Compared with Placebo in Chemotherapy-Naive Patients with Advanced Non-Small- Cell Lung Cancer and Poor Performance Status,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 27, 2009, pp. 2253-2260. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.18.4408

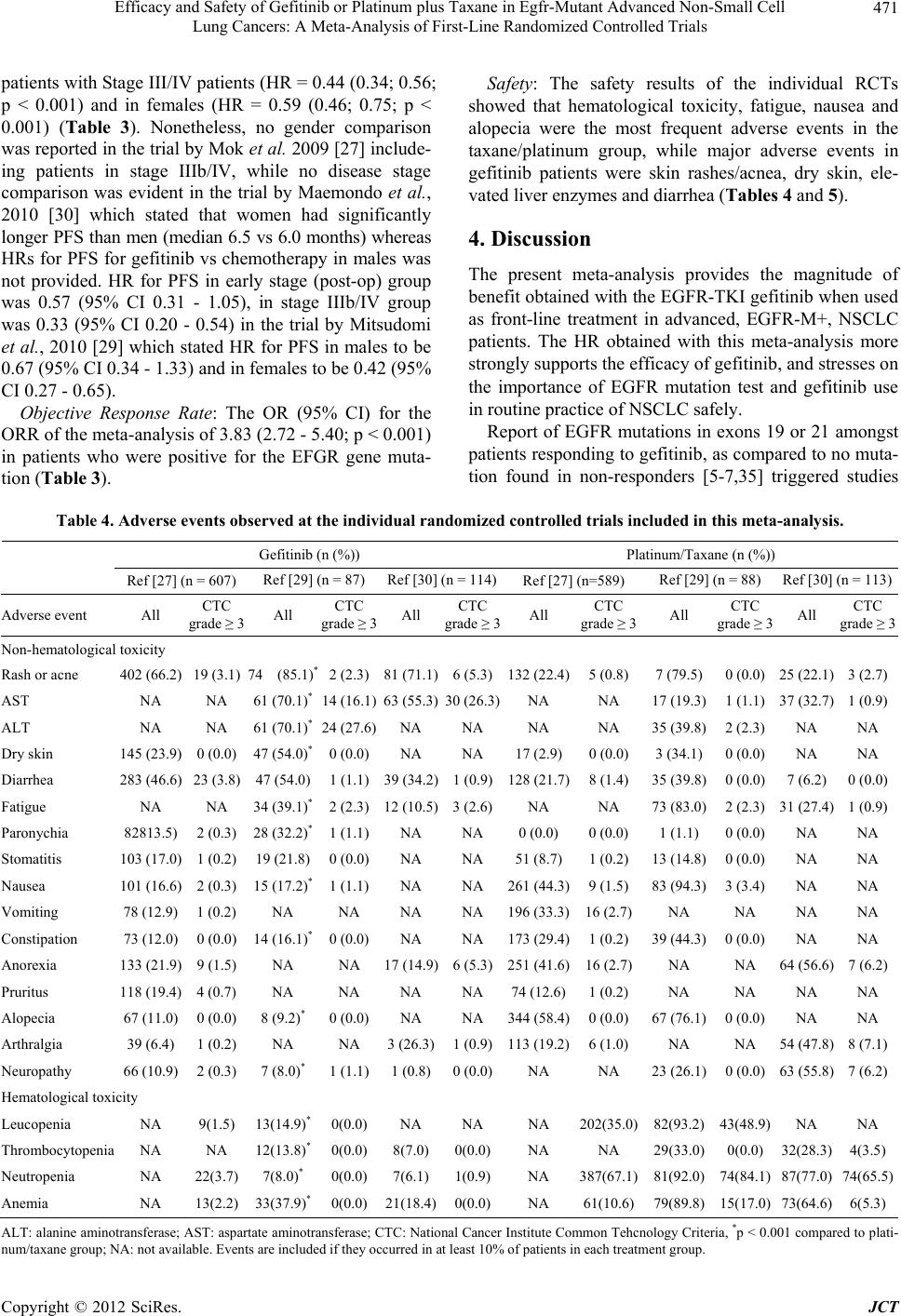

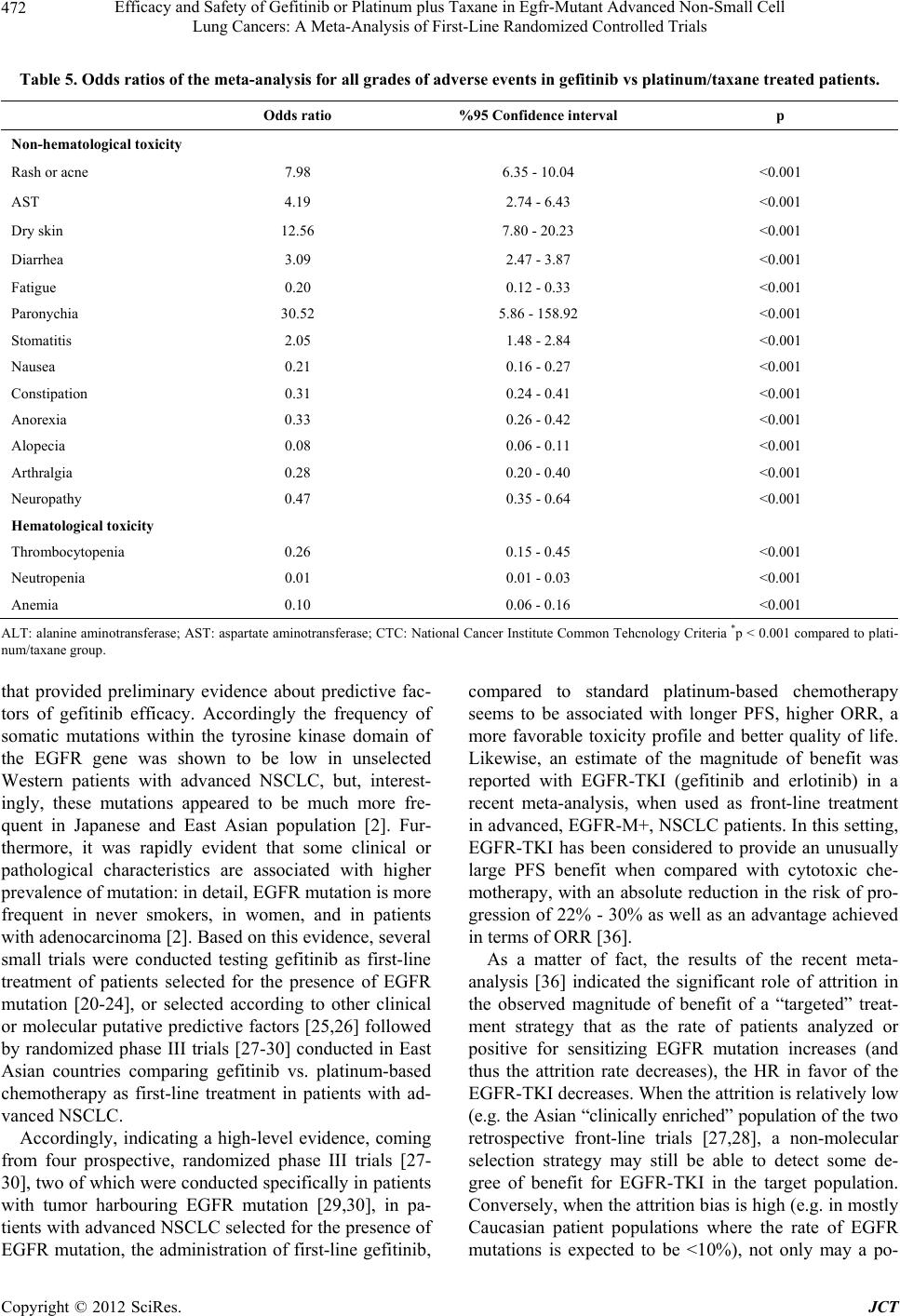

|