Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

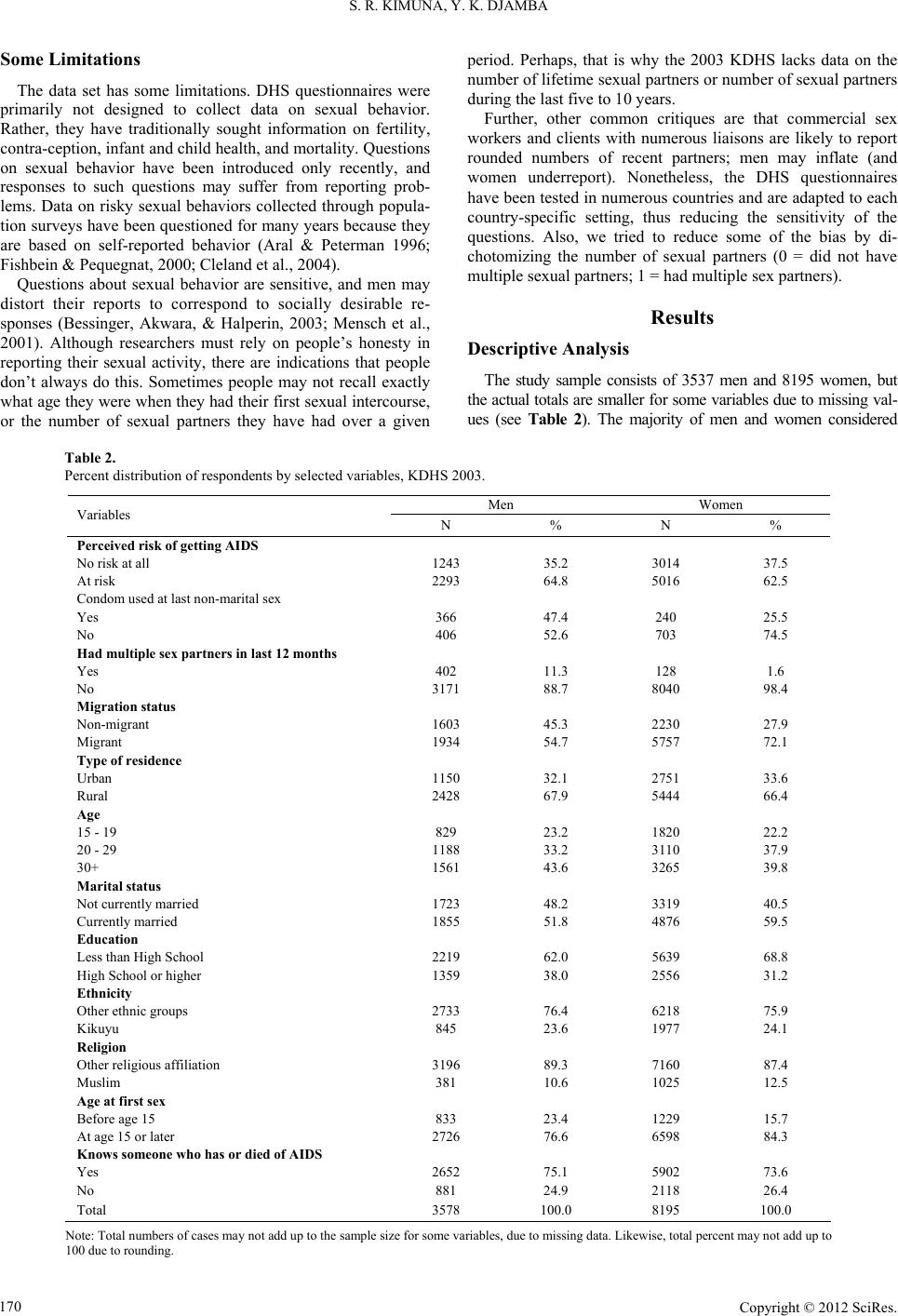

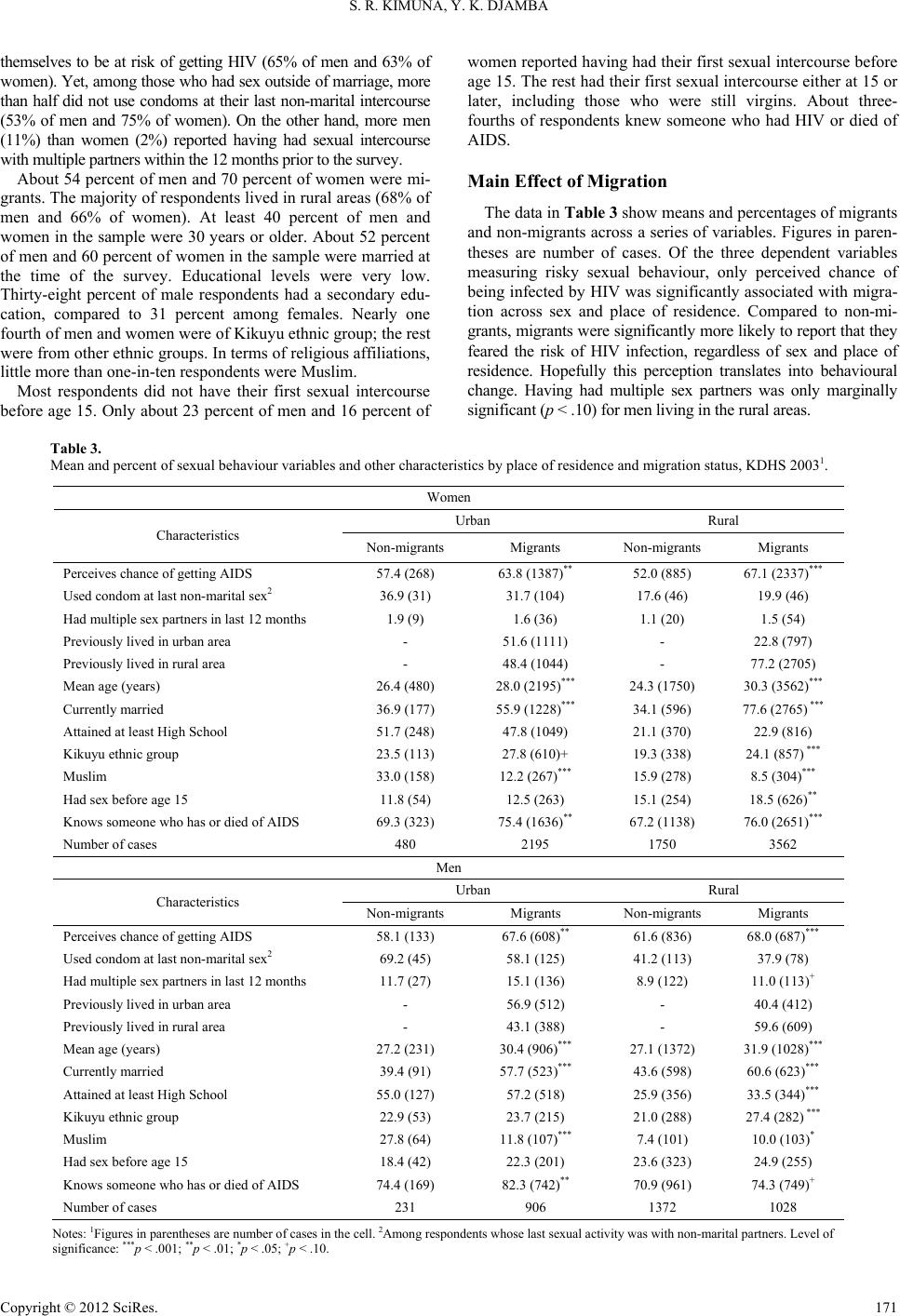

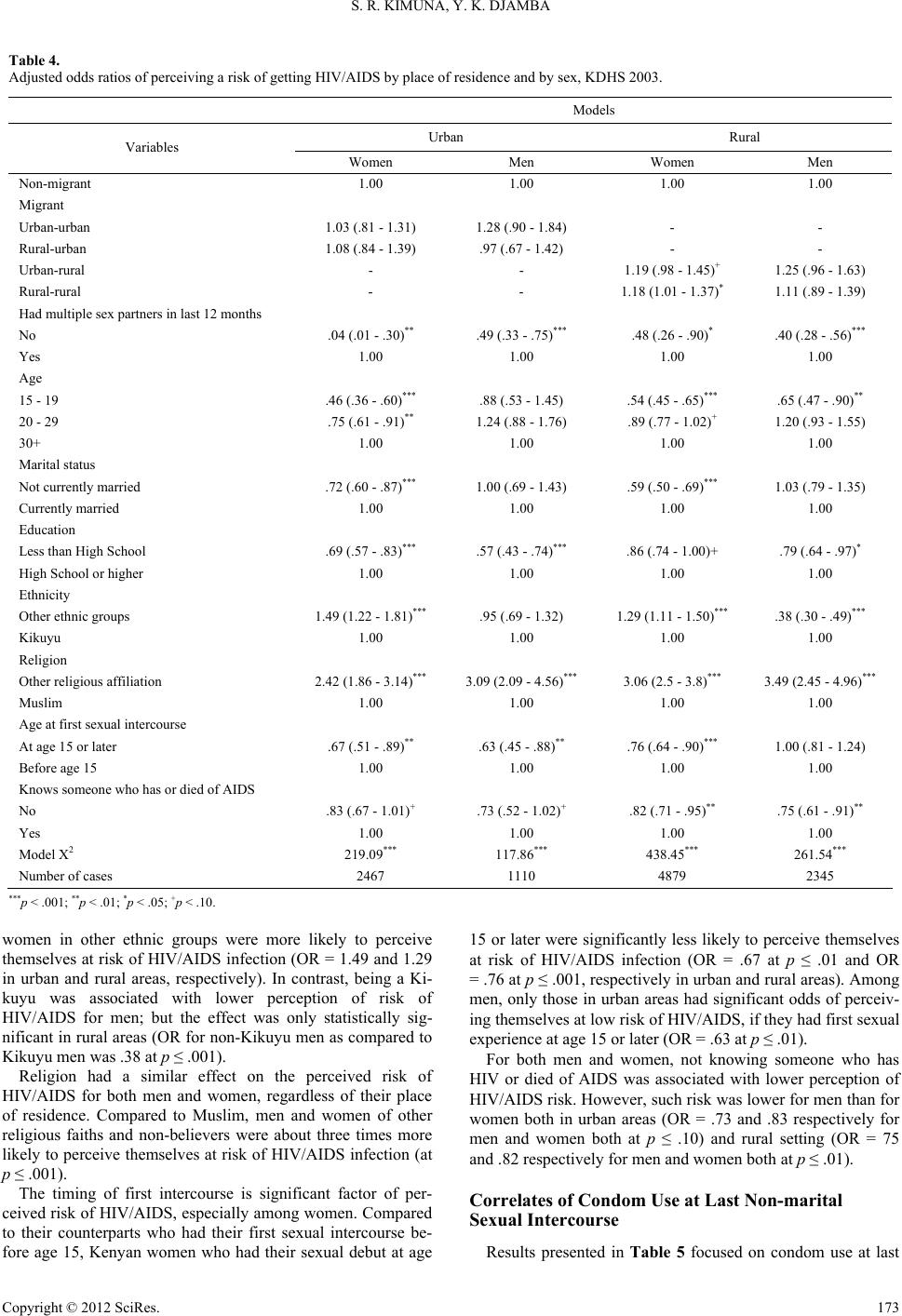

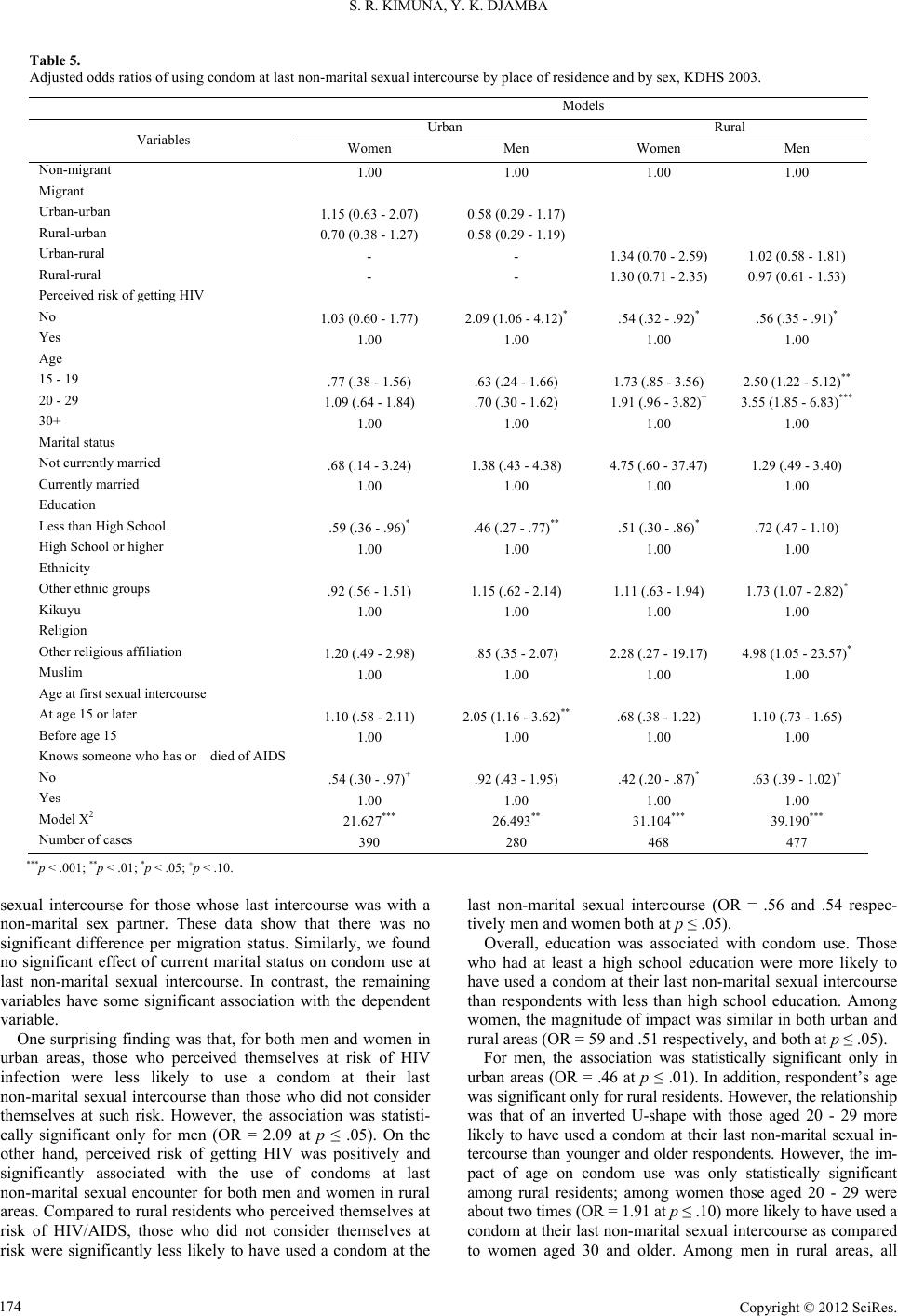

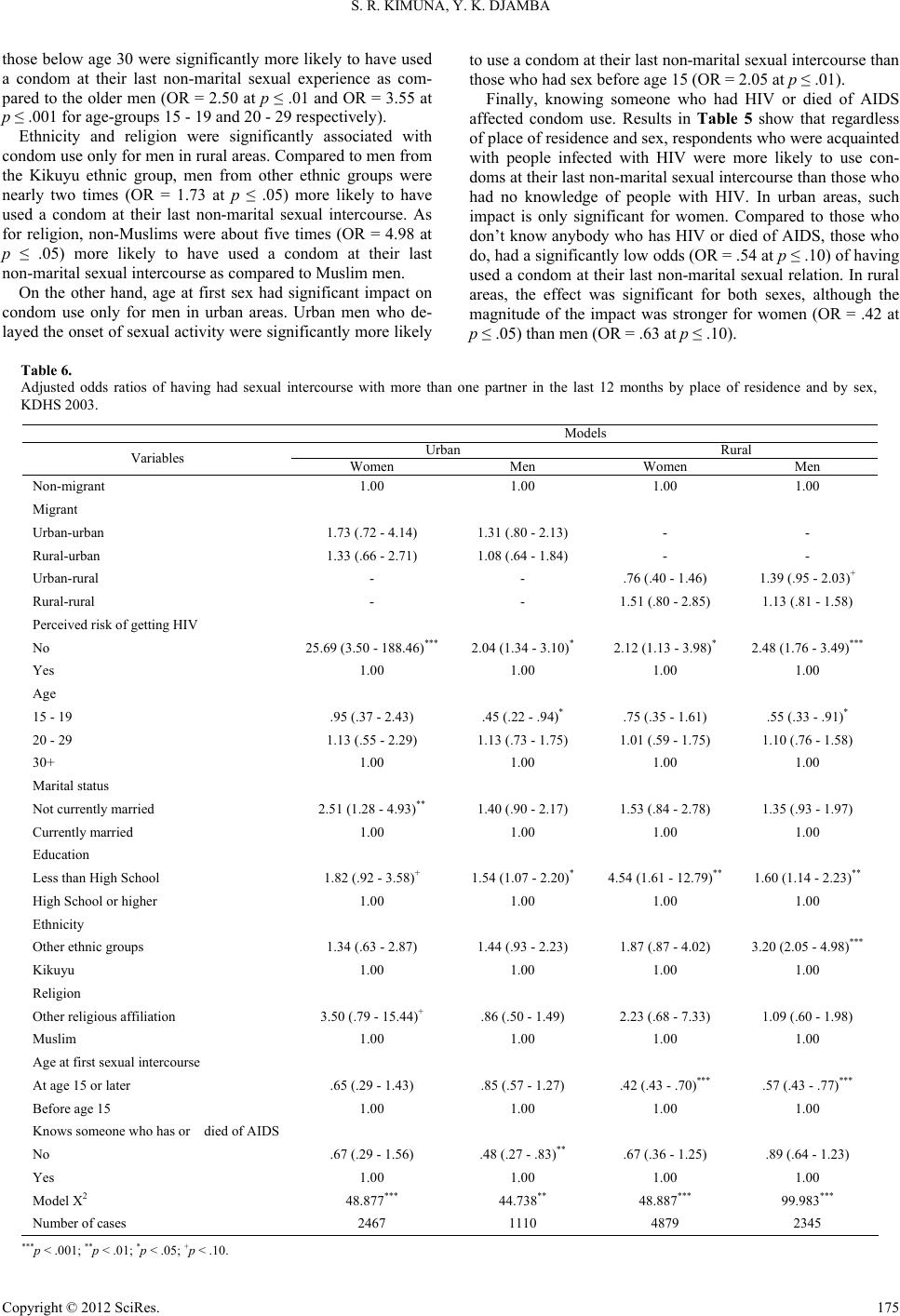

Advances in Applied Sociology 2012. Vol.2, No.3, 167-178 Published Online September 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/aasoci) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2012.23023 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 167 Migration, Sexual Behavior and Perceptions of Risk: Is the Place of Origin a Factor in HIV Infection? Sitawa R. Kimuna1, Yanyi K. Djamba2 1Department of Sociology, East Carolina University, Greenville, USA 2Centre for Demographic Research & Department of Sociology, Auburn University at Montgomery, Montgomery, USA Email: kimunas@ecu.edu, ydjamba@aum.edu Received April 29th, 2012; revised June 5th, 2012; accepted June 15th, 2012 Migration is an important process of change, especially for populations in developing countries. Just by moving to new places, migrants are different from those who do not migrate in terms of socio-demo- graphic characteristics. This study focuses on migration in Kenya and its interaction with human immu- nodeficiency virus (HIV) risk. Two main research questions are addressed: To what extend does the sex- ual behavior of migrants differ from non-migrants? Do migrants know more about HIV risk than non- migrants? The analysis is based on the 2003 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey data. The results show that migrants are significantly more likely to report fear of HIV infection than non-migrants. The perception of risky sexual behavior is significantly correlated with non-use of condoms for migrants than for non-migrants. Migrants who perceive themselves as being at risk of HIV infection are less likely to use a condom at their last non-marital sexual encounter. Also, migration is significantly correlated with multiple sexual partners. There is a remarkable difference in the mean age of migrants and non-migrants; migrants on average are significantly older and more likely to be married than non-migrants. Keywords: Internal Migration; Risky Sexual Behaviour; STIs/HIV; Kenya; Africa Introduction Migration and risky sexual behaviour that might lead to sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and human immunodefi- ciency virus (HIV) infection have been examined separately in sub-Saharan Africa; however, we are still far from understand- ing in detail just how and to what extent migration affects the spread of STIs and HIV. Previous studies of migration and health tend to concentrate on the urban or receiving areas with little attention paid to people living in the rural or sending areas. Research on the dimensions of social and health impacts of internal migration would illuminate our understanding of the consequences of migration on risky sexual behaviour, espe- cially the vulnerability of migrant populations. Studies have shown that people who are more mobile, or who have recently changed residence, tend to be at higher risk for STIs/HIV than those in more stable living arrangements (Arnafi, 1993; Pison et al., 1993; Brockerhoff and Biddlecom, 1999; Lurie et al., 2003; Nyanzi et al., 2004). For example, itinerant traders and long-distance truck drivers have shown to have an increased risk of contracting STIs and HIV (Wilson et al., 2000). Therefore, it can be argued that mobility creates conducive environments for high risk sexual behaviour, which is deter- mined by the number of recent heterosexual partners and by non-use of condoms with these partners. Of particular interest is whether migrants’ previous exposure to urban areas increases their likelihood of high-risk sexual behaviour in rural areas, for example, through socialization to less restrictive sexual norms or acquisition of enabling characteristics (e.g., wealth) in urban areas (Kimuna and Djamba, 2005). Another factor that has been cited in the literature is the separation from a regular sexual partner or spouse (Wilson, 1972; Nyanzi et al., 2004). These studies indicate that the risk of engaging in risky sexual behav- iour increases even for married persons when they are away from their spouses. Other studies have shown that migration of young, unmarried adults from rural areas, which presumably are known to har- bour conservative ideas about sexuality and sexual behaviour than urban centres, have been regarded as partly responsible for high STIs/HIV observed in urban centres (Brockerhoff and Biddlecom, 1999). Others have noted the rise in the number of HIV infections in rural areas due to the return migration to rural communities by those who previously had been living and working in towns and cities (Topouzis and du Guerney, 1999). The association between migration and HIV infection has been echoed in a number of studies (Arnafi, 1993; Lurie et al., 2003; Nyanzi et al., 2004; Lurie, 2006). Also, the spread of infectious diseases can be exacerbated by inadequate structural arrangements that contain the diseases within an environment, especially in rural areas (Anarfi, 2005). Travel between places with different health risk profiles places people in environments where their health is subject to new influences and impacts. This is because migrants’ behaviour away from home often differs from one that is maintained while at home and the social norms that guide and control their behaviour in stable home communities are often missing. For example, in a study of itinerant traders in Uganda, Nyanzi et al. (2004) found that the urban infrastructure and availability of social and economic opportunities in these areas not only acted as magnates for labour migration but also pro- vided an environment that led to risky sexual behaviour with new partners. Nyanzi and colleagues found that most of the  S. R. KIMUNA, Y. K. DJAMBA itinerant traders were “single” in town and ‘married’ in their rural homes (Nyanzi et al., 2004: p. 244). Their single status allowed them to have a myriad of sexual networks, which in- cluded various types of partners: commercial sex workers, one-night stand women, semi-permanent sex partners (or what in sexual behaviour literature is known as “second office”), lovers, and legal wives. When these migrants move without their partners, and probably because of loneliness or as a result of social pressure, they may engage in behaviour that may place them at risk of contracting STIs/HIV. Kenyan Context Historically, Kenya has had a circular pattern of population movement since independence and the ghost syndrome wit- nessed in most Kenyan cities during major holidays attests to this pattern. Further, Kenya’s population is still predominantly rural with 80 percent of the population living in the countryside (CBS et al., 2004). Hence, the widespread assumption that wives of migrants remain in rural areas to take care of the rural household has been used to explain the circular pattern of mi- gration in Kenya. The high mobility of Kenyan population is due to the fact that young people graduating from rural schools move to urban areas to seek employment. These young people return home periodically depending on how far the urban areas are from their places of origin. Elsewhere, this pattern has also been linked to the spread of STIs/HIV in rural areas (Lurie et al., 1997). Furthermore, migrants from rural areas to urban areas in search of better economic opportunity may be at risk when they arrive at their destination. Particularly, when sepa- rated from the social controls exercised by families, communi- ties, and wider social norms. The situation can be exacerbated by rural-urban migrants experiencing emotional instability on exposure to the urban environment, which can lead to potential high risk sexual relationships. Although Kenya’s rates of new HIV infections show a de- cline (UNAIDS, 2006), its prevalence rate of 7 percent among adults is still alarming (CBS et al., 2004). The situation is even more critical in urban areas where 10 percent of residents are HIV positive compared to 6 percent in rural areas. This would mean that migrants moving to urban centres have a greater risk for contracting STIs/HIV as well as non-migrants in rural areas, who have a sexual network of migrants. This study focuses on migration in Kenya and its interaction with HIV risk. Two main research questions are addressed: To what extend does the sexual behavior of migrants differ from non-migrants? Do migrants know more about HIV risk than non-migrants? The paper aims to make a contribution to the evidence of the association of migration and risky sexual be- haviour by systematically examining the impact of migration status and migration stream on both the perceived and actual risks of HIV infection among both men and women. Our main focus is on the extent to which internal migration effects a change in the environment and contributes to the spread of STIs/HIV. Internal migration is defined within this paper as the movement of people from one place of residence to another in search of economic opportunities for a period of time within the same national territory. Studies have shown that this type of migration process exists in most sub-Saharan African countries. This study does not present data or sero-prevalence. We attempt to answer the following questions by examining the influence of migration status and migration stream on risky sexual behaviour of men and women by place of residence: How do migrants and non-migrants perceive their risk of infec- tion? Do migrants and non-migrants have the same risk in terms of condom use and multiple sexual partners? Although this research does not focus on gender differences, it recognizes that migration and sexuality are gender-specific phenomena. For example, a study in Ethiopia and South Africa showed that, although men and women expressed the same intentions for moving, their actual migration experiences were significantly different (Djamba, 2003). Also, underlying the relationship between migration and risky sexual behaviour are clear gender differences, which other studies have noted and argued that the difference in having multiple sexual partners is more prevalent among men (Kimuna & Djamba, 2005) than among women (Brockerhoff & Biddle- com, 1999). This is partly because in most societies, men have the cultural prerogative to initiate and negotiate sexual rela- tionships and women do not. In addition, women are more likely to apply an economic rationale to sexual risk taking such as “survival sex” (Barnett & Whiteside, 2006; for a detailed discussion of “survival sex,” see Leclerc-Madlala, 2003). There- fore, we conducted the analysis of the role of migration in risky sexual behaviour separately for men and women. Data and Method Data This study is based on data from the 2003 Kenya Demo- graphic and Health Survey (KDHS). The 2003 KDHS is a na- tionally representative sample of adult Kenyans. Data were collected on health, sexual behaviour, marital status, and household characteristics. The survey instruments were based on model questionnaires developed by the MEASURE DHS+ program. The survey was implemented by the Kenya Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) in collaboration with other local agencies. The survey response rates were high (94% for women and 86% for men), with a total of 8195 women and 3574 men successfully interviewed. More details about survey design and methodology were published elsewhere (CBS et al., 2004). Variables This study focuses on the extent to which migration effects a change in the environment and contributes to risky sexual be- haviour. We consider three dependent variables that measure risky sexual behaviour: 1) perceived risk of HIV; 2) condom use at last non-marital sexual intercourse; and 3) having multi- ple sex partners during the last 12 months. Because of the ques- tionable sexual behaviour data based on self-reports, perceived risk of HIV infection has been identified as a preferred proxy variable to looking at HIV vulnerability (Smith & Watkins, 2005) from the respondent’s point of view. Condom use is known to reduce the risk of sexually transmitted diseases in- cluding HIV/AIDS. Number of sexual partners is known to be positively associated with the risk of contracting STIs/HIV (Ntozi & Ahimbisibwe, 1999; Zulu et al., 2002). Migration is the main explanatory variable. It was defined using information from the question on the duration of resi- dence at the current place of residence. Respondents were asked, “How long have you been living continuously in (name of the current place of residence)?” There was a choice of three an- swers: 1) “number of years,” for those who had lived elsewhere; Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 168  S. R. KIMUNA, Y. K. DJAMBA 2) “always,” for those who never moved, and 3) “visitor”. After examining the frequency distribution of the answers, we re- tained the first two categories because the visitor category was negligible (1% in the male sample and 2% in the female sam- ple). The first category included in this analysis represents mi- grants or those who have moved. The second category includes non-migrants or, those who have always lived at their current place of interview. We also used the information on previous place of residence for migrants to construct migration streams. The information was obtained from the responses to the question, “Just before you moved here, did you live in Nairobi, Mombasa, in another city or town, or in the countryside?” This question was asked only of those who moved. Thus, we have not only the respon- dents’ migration status, but also their migration stream status measured by their last move. We included two other correlates of sexual risk in our analy- sis: age at first sexual intercourse and knowing someone who has or died of AIDS. Age at first intercourse was dichotomized dividing respondents into two categories: 1) those who had sex before age 15 and 2) those who had sex at age 15 or later. The second category also included respondents who had not yet had sex (16% of all male respondents and 18% of all female re- spondents were in that category). Sexual behaviour at a young age poses multiple risks includ- ing prolonged exposure to risk of being infected with STIs and HIV/AIDS. Furthermore, young girls are less likely to know safe sex methods and more likely to be sexually disadvantaged due to myriad reasons including lack of bargaining power. Longfield et al. (2004) have argued that young women who have sex with older men are unlikely to insist on condom use. Previous research has produced conflicting results on the effect of knowing someone who has or died of AIDS on behaviour change; some found positive and significant behaviour changes (Palekar et al., 2007) and others denoted no significant associa- tion (Camlin & Chimbwete, 2003). We re-examined this asso- ciation separately for men and women. Socio-demographic variables included in the analysis are: age, marital status, education, ethnicity, and religion. Age was broken down into three categories: 15 - 19, 20 - 29, and 30+. In a country where life expectancy remains relatively low, this age classification is important in order to examine potential differ- ences in risky sexual behaviours between teenagers, young adults, and older adults. Marital status was categorized into currently married and not currently married. Education variable had two categories: less than high school and high school or higher. Analytical Appro ach es Our analyses were conducted in two steps. First, we used descriptive statistics to examine the characteristics of the study samples and to explore binary differences between migrants and non-migrants. Second, we conducted multivariate analyses to examine the impact of migration on risky sexual behaviour, net of the effects of other variables. We dichotomized the de- pendent variables with “1” (or yes) indicating that the respon- dent engaged in risky sexual behaviour (e.g., considered him/herself to be at risk of being infected with HIV, did not use a condom at the last non-marital sexual intercourse, or had sex with multiple sexual partners), and “0” otherwise. Because each of our three dependent variables was dichoto- mized, we fitted adjusted logistic regression models in the form of: 01122 nn logRSB1-RSB = β+ βX+ βX+ ... + βX where RSB represents the probability that the respondent en- gaged in risky sexual behavior; X1, X2, ···, Xn are the inde- pendent variables, and β0, β1, β2, ···, βn are the regression coef- ficients from the fitted models. Our analyses focused on the complexity of the migration patterns in Kenya as well as the vulnerability of migrants and their networks (those with whom they interact). Because mi- grants are a heterogeneous group, it was important to examine how their sexual behaviours, which may lead to infection, var- ied between migrants and non-migrants, separately in urban and rural areas. These variables and other important correlates of risky sexual behaviour and migration are shown in Table 1. Table 1. List of variables used in the analysis of migration and risky sexual behaviour in Kenya, KDHS 2003. Variables Categories Risky se x ual behaviour 0 = No Perceives chance of getting AIDS 1 = Yes 0 = No Used condom at last non-marital sex 1 = Yes 0 = One or none Had multiple sexual partners in last 12 months 1 = Two or more Migration status and migration stream by residence 0 = Non-migrant 1 = Urban-urban migrant Urban residence 2 = Rural urban 0 = Non-migrant 1 = Urban-rural migrant Rural residence 2 = Rural-rural Socio-demographi c and other variables 1 = 15 - 19 years 2 = 20 - 29 Age 3 = 30 or older 0 = Not currently married Marital status 1 = Currently married 0 = Less than High School Education 1 = High School or higher 0 = Other ethnic group Ethnicity 1 = Kikuyu 0 = Other religious affiliation Religion 1 = Muslim 0 = At age 15 or later Age at first sex 1 = Before age 15 0 = No Knows someone who has or died of AIDS 1 = Yes Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 169  S. R. KIMUNA, Y. K. DJAMBA Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 170 Some Limitations The data set has some limitations. DHS questionnaires were primarily not designed to collect data on sexual behavior. Rather, they have traditionally sought information on fertility, contra-ception, infant and child health, and mortality. Questions on sexual behavior have been introduced only recently, and responses to such questions may suffer from reporting prob- lems. Data on risky sexual behaviors collected through popula- tion surveys have been questioned for many years because they are based on self-reported behavior (Aral & Peterman 1996; Fishbein & Pequegnat, 2000; Cleland et al., 2004). Questions about sexual behavior are sensitive, and men may distort their reports to correspond to socially desirable re- sponses (Bessinger, Akwara, & Halperin, 2003; Mensch et al., 2001). Although researchers must rely on people’s honesty in reporting their sexual activity, there are indications that people don’t always do this. Sometimes people may not recall exactly what age they were when they had their first sexual intercourse, or the number of sexual partners they have had over a given period. Perhaps, that is why the 2003 KDHS lacks data on the number of lifetime sexual partners or number of sexual partners during the last five to 10 years. Further, other common critiques are that commercial sex workers and clients with numerous liaisons are likely to report rounded numbers of recent partners; men may inflate (and women underreport). Nonetheless, the DHS questionnaires have been tested in numerous countries and are adapted to each country-specific setting, thus reducing the sensitivity of the questions. Also, we tried to reduce some of the bias by di- chotomizing the number of sexual partners (0 = did not have multiple sexual partners; 1 = had multiple sex partners). Results Descriptive Analysis The study sample consists of 3537 men and 8195 women, but the actual totals are smaller for some variables due to missing val- ues (see Table 2). The majority of men and women considered Table 2. Percent distribution of respondents by selected variables, KDHS 2003. Men Women Variables N % N % Perceive d risk of getting AIDS No risk at all 1243 35.2 3014 37.5 At risk 2293 64.8 5016 62.5 Condom used at last non-marital sex Yes 366 47.4 240 25.5 No 406 52.6 703 74.5 Had multiple s ex partners i n l ast 12 months Yes 402 11.3 128 1.6 No 3171 88.7 8040 98.4 Migration status Non-migrant 1603 45.3 2230 27.9 Migrant 1934 54.7 5757 72.1 Type of residence Urban 1150 32.1 2751 33.6 Rural 2428 67.9 5444 66.4 Age 15 - 19 829 23.2 1820 22.2 20 - 29 1188 33.2 3110 37.9 30+ 1561 43.6 3265 39.8 Marital status Not currently married 1723 48.2 3319 40.5 Currently married 1855 51.8 4876 59.5 Education Less than High School 2219 62.0 5639 68.8 High School or higher 1359 38.0 2556 31.2 Ethnicity Other ethnic groups 2733 76.4 6218 75.9 Kikuyu 845 23.6 1977 24.1 Religion Other religious affiliation 3196 89.3 7160 87.4 Muslim 381 10.6 1025 12.5 Age at first sex Before age 15 833 23.4 1229 15.7 At age 15 or later 2726 76.6 6598 84.3 Knows someone who has or died of AIDS Yes 2652 75.1 5902 73.6 No 881 24.9 2118 26.4 Total 3578 100.0 8195 100.0 Note: Total numbers of cases may not add up to the sample size for some variables, due to missing data. Likewise, total percent may not add up to 100 due to rounding.  S. R. KIMUNA, Y. K. DJAMBA themselves to be at risk of getting HIV (65% of men and 63% of women). Yet, among those who had sex outside of marriage, more than half did not use condoms at their last non-marital intercourse (53% of men and 75% of women). On the other hand, more men (11%) than women (2%) reported having had sexual intercourse with multiple partners within the 12 months prior to the survey. About 54 percent of men and 70 percent of women were mi- grants. The majority of respondents lived in rural areas (68% of men and 66% of women). At least 40 percent of men and women in the sample were 30 years or older. About 52 percent of men and 60 percent of women in the sample were married at the time of the survey. Educational levels were very low. Thirty-eight percent of male respondents had a secondary edu- cation, compared to 31 percent among females. Nearly one fourth of men and women were of Kikuyu ethnic group; the rest were from other ethnic groups. In terms of religious affiliations, little more than one-in-ten respondents were Muslim. Most respondents did not have their first sexual intercourse before age 15. Only about 23 percent of men and 16 percent of women reported having had their first sexual intercourse before age 15. The rest had their first sexual intercourse either at 15 or later, including those who were still virgins. About three- fourths of respondents knew someone who had HIV or died of AIDS. Main Effect of Mig ration The data in Table 3 show means and percentages of migrants and non-migrants across a series of variables. Figures in paren- theses are number of cases. Of the three dependent variables measuring risky sexual behaviour, only perceived chance of being infected by HIV was significantly associated with migra- tion across sex and place of residence. Compared to non-mi- grants, migrants were significantly more likely to report that they feared the risk of HIV infection, regardless of sex and place of residence. Hopefully this perception translates into behavioural change. Having had multiple sex partners was only marginally significant (p < .10) for men living in the rural areas. Table 3. Mean and percent of sexual behaviour variables and other characteristics by place of residence and migration status, KDHS 20031. Women Urban Rural Characteristics Non-migrants Migrants Non-migrants Migrants Perceives chance of getting AIDS 57.4 (268) 63.8 (1387)** 52.0 (885) 67.1 (2337)*** Used condom at last non-marital sex2 36.9 (31) 31.7 (104) 17.6 (46) 19.9 (46) Had multiple sex partners in last 12 months 1.9 (9) 1.6 (36) 1.1 (20) 1.5 (54) Previously lived in urban area - 51.6 (1111) - 22.8 (797) Previously lived in rural area - 48.4 (1044) - 77.2 (2705) Mean age (years) 26.4 (480) 28.0 (2195)*** 24.3 (1750) 30.3 (3562)*** Currently married 36.9 (177) 55.9 (1228)*** 34.1 (596) 77.6 (2765) *** Attained at least High School 51.7 (248) 47.8 (1049) 21.1 (370) 22.9 (816) Kikuyu ethnic group 23.5 (113) 27.8 (610)+ 19.3 (338) 24.1 (857) *** Muslim 33.0 (158) 12.2 (267)*** 15.9 (278) 8.5 (304)*** Had sex before age 15 11.8 (54) 12.5 (263) 15.1 (254) 18.5 (626)** Knows someone who has or died of AIDS 69.3 (323) 75.4 (1636)** 67.2 (1138) 76.0 (2651)*** Number of cases 480 2195 1750 3562 Men Urban Rural Characteristics Non-migrants Migrants Non-migrants Migrants Perceives chance of getting AIDS 58.1 (133) 67.6 (608)** 61.6 (836) 68.0 (687)*** Used condom at last non-marital sex2 69.2 (45) 58.1 (125) 41.2 (113) 37.9 (78) Had multiple sex partners in last 12 months 11.7 (27) 15.1 (136) 8.9 (122) 11.0 (113)+ Previously lived in urban area - 56.9 (512) - 40.4 (412) Previously lived in rural area - 43.1 (388) - 59.6 (609) Mean age (years) 27.2 (231) 30.4 (906)*** 27.1 (1372) 31.9 (1028)*** Currently married 39.4 (91) 57.7 (523)*** 43.6 (598) 60.6 (623)*** Attained at least High School 55.0 (127) 57.2 (518) 25.9 (356) 33.5 (344)*** Kikuyu ethnic group 22.9 (53) 23.7 (215) 21.0 (288) 27.4 (282) *** Muslim 27.8 (64) 11.8 (107)*** 7.4 (101) 10.0 (103)* Had sex before age 15 18.4 (42) 22.3 (201) 23.6 (323) 24.9 (255) Knows someone who has or died of AIDS 74.4 (169) 82.3 (742)** 70.9 (961) 74.3 (749)+ Number of cases 231 906 1372 1028 Notes: 1Figures in parentheses are number of cases in the cell. 2Among respondents whose last sexual activity was with non-marital partners. Level of significance: ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05; +p < .10. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 171  S. R. KIMUNA, Y. K. DJAMBA The difference in the mean age of migrants and non-migrants was remarkable and statistically significant for both men and women in urban and rural areas. That is, on average migrants were older than non-migrants. In addition, migrants were sig- nificantly more likely to be married than were non-migrants. In urban areas, almost 56 percent of migrant women were married compared to 37 percent of non-migrant women. In the rural areas, the difference was even greater; almost 78 percent of migrant women were married compared to 34 percent for non-migrants. Similar to women, there were also greater dif- ferences among men; almost 58 percent of urban migrant men were married compared to 39 percent of urban non-migrant men. In the rural areas, almost 61 percent of migrant men were married compared to 44 percent of non-migrant men. The association between migration and education was only significant among men in rural areas, where migrants had higher education than non-migrants. On the other hand, re- spondents of the Kikuyu ethnic group were significantly more likely to be migrants, except for Kikuyu men in urban areas. As for religion, there were striking differences by sex. Among women, migrants were significantly less likely to be Muslim as compared to non-migrants, regardless of place of residence. Among men, only those migrants living in urban areas were significantly less likely to be Muslims as compared to non-migrants in the same areas. In contrast, migrant men in the rural areas were significantly more likely to be Muslims than their non-migrant counterparts. Migrants were more likely to have had sex before age 15 than non-migrants. This difference in having had sex before age 15 was observed across gender, but it was only statistically significant for women in rural areas. In rural areas, female mi- grants were significantly more likely to start sexual intercourse before age 15 (18.5%) compared to non-migrants (15.1%). On the whole, in both urban and rural areas, male and female migrants were significantly more likely to know someone suf- fering from HIV or died of AIDS. Among women living in urban areas at the time of the survey, 75 percent knew someone who had HIV or died of AIDS compared to 69 percent of non-migrant women; the same pattern was observed in rural areas with 76 percent for migrants versus 67 percent for non- migrants. This difference was also observed among men. Urban migrant men were more likely to know someone suffering from HIV or died of AIDS (82.3%) than were non-migrant men (74.4%). The difference between rural migrants and non-mi- grants was 3.4 percent. Multivariate Analyses We examined how our independent variables and correlates of risky sexual behaviour were associated with each of the three dependent variables. The analyses were conducted using the logistic regression equations in which we predicted the likeli- hood of occurrence of the event (for each of the dependent variables) based on a set of predictors, separately for men and women and by their current place of residence. Data in Tables 4-6 are adjusted odds ratios (and 95% confident intervals given in parentheses). The adjusted odds ratios present the net effect of each variable on the dependent variable, controlling for the effects of other variables. Respondent’s Perceived Risk of HIV/AIDS Infection Data in Table 4 show the association between migration status (and last migration stream) and socio-demographic char- acteristics on the perceived risk of being infected with HIV/AIDS. The reported figures are odds ratios (OR), with their confidence intervals (CI) given in parentheses at different probability levels (P). An OR greater than 1 means greater risk, whereas an OR of less than 1 means lower risk. Compared to non-migrant women, migrant women in both rural and urban settings perceived themselves to be at greater risk of being infected; but the association was only statistically significant in rural areas. Compared to non-migrant women in rural areas, urban-rural and rural-rural migrant women were significantly more likely to perceive themselves at higher risk of contracting HIV (OR = 1.19 at p ≤ .10 and OR = 1.18 at p ≤ .05, respectively). There was no significant effect of migra- tion on perceived HIV/AIDS risk among men. In contrast, having sexual intercourse with multiple partners in the last 12 months was associated with perceived risk of HIV/AIDS infection for both men and women. Nonetheless, the sex difference was greater in urban areas (OR = .04 at p ≤ .01 and OR = .49 at p ≤ .001 for women and men respectively) than rural areas (OR = .48 at p ≤ .05 and OR = .40 at p ≤ .001 for women and men respectively). All other variables in the model were significantly asso- ciated with women’s perceived risk of HIV/AIDS infection regardless of their current place of residence. Women data in Table 4 show that the perceived risk of HIV/AIDS infection increases with the woman’s age. The odds ratios of such risk among women in urban areas were .46 (at p ≤ .001) for those age 15 - 19 and .75 (at p ≤ .01) for those age 20 - 29, as compared to women 30 years and older. A similar pattern was observed among women living rural areas (OR = .54 at p ≤ .001 and OR = .89 at p ≤ .10 for women ages 15 - 19 and 20 - 29 respectively). In contrast, the impact of age was statistically significant only among young urban resident men (OR = .65 at p ≤ .01) as compared to men 30 years and older. Another interesting finding from this study is that unmarried women perceived themselves at lower risk of HIV/AIDS as compared to married women. Data in Table 4 shows that in both urban and rural areas, unmarried women were signifi- cantly less likely to consider themselves at risk of being in- fected with HIV/AIDS. Compared to their married counterparts, unmarried women’s odds of perceived risk of HIV/AIDS were significantly lower: OR = .75 (p ≤ .001) and OR = .59 (p ≤ .001) respectively in urban and rural areas. Marriage did not have a significant impact on men’s perceived risk of HIV/AIDS. These results indicate that marriage is not a protective status against HIV/AIDS risk for women in Kenya. The results on the impact of education were also statistically significant. Compared to those with high school and higher, women with less than high school education perceived them- selves at lower risk of HIV/AIDS infection. However, the im- pact was more substantial in urban areas (OR = .69 at p ≤ .001) than rural places (OR = .86 at p ≤ .10). Among men, the impact of education was also positively associated with perceived risk of HIV/AIDS infection. Hence, compared to men with high school education and higher, those with less than high school education considered themselves at lower risk of infection, but more so in urban areas (OR = .57 at p ≤ .001) than in rural areas (OR = .79 at p ≤ .05). The influences of ethnicity were all significant at p ≤ .001 for women. Compared to women in the Kikuyu ethnic group, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 172  S. R. KIMUNA, Y. K. DJAMBA Table 4. Adjusted odds ratios of perceiving a risk of getting HIV/AIDS by place of residence and by sex, KDHS 2003. Models Urban Rural Variables Women Men Women Men Non-migrant 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Migrant Urban-urban 1.03 (.81 - 1.31) 1.28 (.90 - 1.84) - - Rural-urban 1.08 (.84 - 1.39) .97 (.67 - 1.42) - - Urban-rural - - 1.19 (.98 - 1.45)+ 1.25 (.96 - 1.63) Rural-rural - - 1.18 (1.01 - 1.37)* 1.11 (.89 - 1.39) Had multiple sex partners in last 12 months No .04 (.01 - .30)** .49 (.33 - .75)*** .48 (.26 - .90)* .40 (.28 - .56)*** Yes 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Age 15 - 19 .46 (.36 - .60)*** .88 (.53 - 1.45) .54 (.45 - .65)*** .65 (.47 - .90)** 20 - 29 .75 (.61 - .91)** 1.24 (.88 - 1.76) .89 (.77 - 1.02)+ 1.20 (.93 - 1.55) 30+ 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Marital status Not currently married .72 (.60 - .87)*** 1.00 (.69 - 1.43) .59 (.50 - .69)*** 1.03 (.79 - 1.35) Currently married 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Education Less than High School .69 (.57 - .83)*** .57 (.43 - .74)*** .86 (.74 - 1.00)+ .79 (.64 - .97)* High School or higher 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Ethnicity Other ethnic groups 1.49 (1.22 - 1.81)*** .95 (.69 - 1.32) 1.29 (1.11 - 1.50)*** .38 (.30 - .49)*** Kikuyu 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Religion Other religious affiliation 2.42 (1.86 - 3.14)*** 3.09 (2.09 - 4.56)*** 3.06 (2.5 - 3.8)*** 3.49 (2.45 - 4.96)*** Muslim 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Age at first sexual intercourse At age 15 or later .67 (.51 - .89)** .63 (.45 - .88)** .76 (.64 - .90)*** 1.00 (.81 - 1.24) Before age 15 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Knows someone who has or died of AIDS No .83 (.67 - 1.01)+ .73 (.52 - 1.02)+ .82 (.71 - .95)** .75 (.61 - .91)** Yes 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Model X2 219.09*** 117.86*** 438.45*** 261.54*** Number of cases 2467 1110 4879 2345 ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05; +p < .10. women in other ethnic groups were more likely to perceive themselves at risk of HIV/AIDS infection (OR = 1.49 and 1.29 in urban and rural areas, respectively). In contrast, being a Ki- kuyu was associated with lower perception of risk of HIV/AIDS for men; but the effect was only statistically sig- nificant in rural areas (OR for non-Kikuyu men as compared to Kikuyu men was .38 at p ≤ .001). Religion had a similar effect on the perceived risk of HIV/AIDS for both men and women, regardless of their place of residence. Compared to Muslim, men and women of other religious faiths and non-believers were about three times more likely to perceive themselves at risk of HIV/AIDS infection (at p ≤ .001). The timing of first intercourse is significant factor of per- ceived risk of HIV/AIDS, especially among women. Compared to their counterparts who had their first sexual intercourse be- fore age 15, Kenyan women who had their sexual debut at age 15 or later were significantly less likely to perceive themselves at risk of HIV/AIDS infection (OR = .67 at p ≤ .01 and OR = .76 at p ≤ .001, respectively in urban and rural areas). Among men, only those in urban areas had significant odds of perceiv- ing themselves at low risk of HIV/AIDS, if they had first sexual experience at age 15 or later (OR = .63 at p ≤ .01). For both men and women, not knowing someone who has HIV or died of AIDS was associated with lower perception of HIV/AIDS risk. However, such risk was lower for men than for women both in urban areas (OR = .73 and .83 respectively for men and women both at p ≤ .10) and rural setting (OR = 75 and .82 respectively for men and women both at p ≤ .01). Correlates of Condom Use at Last Non-marital Sexual Intercourse Results presented in Table 5 focused on condom use at last Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 173  S. R. KIMUNA, Y. K. DJAMBA Table 5. Adjusted odds ratios of using condom at last non-marital sexual intercourse by place of residence and by sex, KDHS 2003. Models Urban Rural Variables Women Men Women Men Non-migrant 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Migrant Urban-urban 1.15 (0.63 - 2.07) 0.58 (0.29 - 1.17) Rural-urban 0.70 (0.38 - 1.27) 0.58 (0.29 - 1.19) Urban-rural - - 1.34 (0.70 - 2.59) 1.02 (0.58 - 1.81) Rural-rural - - 1.30 (0.71 - 2.35) 0.97 (0.61 - 1.53) Perceived risk of getting HIV No 1.03 (0.60 - 1.77) 2.09 (1.06 - 4.12)* .54 (.32 - .92)* .56 (.35 - .91)* Yes 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Age 15 - 19 .77 (.38 - 1.56) .63 (.24 - 1.66) 1.73 (.85 - 3.56) 2.50 (1.22 - 5.12)** 20 - 29 1.09 (.64 - 1.84) .70 (.30 - 1.62) 1.91 (.96 - 3.82)+ 3.55 (1.85 - 6.83)*** 30+ 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Marital status Not currently married .68 (.14 - 3.24) 1.38 (.43 - 4.38) 4.75 (.60 - 37.47) 1.29 (.49 - 3.40) Currently married 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Education Less than High School .59 (.36 - .96)* .46 (.27 - .77)** .51 (.30 - .86)* .72 (.47 - 1.10) High School or higher 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Ethnicity Other ethnic groups .92 (.56 - 1.51) 1.15 (.62 - 2.14) 1.11 (.63 - 1.94) 1.73 (1.07 - 2.82)* Kikuyu 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Religion Other religious affiliation 1.20 (.49 - 2.98) .85 (.35 - 2.07) 2.28 (.27 - 19.17) 4.98 (1.05 - 23.57)* Muslim 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Age at first sexual intercourse At age 15 or later 1.10 (.58 - 2.11) 2.05 (1.16 - 3.62)** .68 (.38 - 1.22) 1.10 (.73 - 1.65) Before age 15 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Knows someone who has or died of AIDS No .54 (.30 - .97)+ .92 (.43 - 1.95) .42 (.20 - .87)* .63 (.39 - 1.02)+ Yes 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Model X2 21.627*** 26.493** 31.104*** 39.190*** Number of cases 390 280 468 477 ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05; +p < .10. sexual intercourse for those whose last intercourse was with a non-marital sex partner. These data show that there was no significant difference per migration status. Similarly, we found no significant effect of current marital status on condom use at last non-marital sexual intercourse. In contrast, the remaining variables have some significant association with the dependent variable. One surprising finding was that, for both men and women in urban areas, those who perceived themselves at risk of HIV infection were less likely to use a condom at their last non-marital sexual intercourse than those who did not consider themselves at such risk. However, the association was statisti- cally significant only for men (OR = 2.09 at p ≤ .05). On the other hand, perceived risk of getting HIV was positively and significantly associated with the use of condoms at last non-marital sexual encounter for both men and women in rural areas. Compared to rural residents who perceived themselves at risk of HIV/AIDS, those who did not consider themselves at risk were significantly less likely to have used a condom at the last non-marital sexual intercourse (OR = .56 and .54 respec- tively men and women both at p ≤ .05). Overall, education was associated with condom use. Those who had at least a high school education were more likely to have used a condom at their last non-marital sexual intercourse than respondents with less than high school education. Among women, the magnitude of impact was similar in both urban and rural areas (OR = 59 and .51 respectively, and both at p ≤ .05). For men, the association was statistically significant only in urban areas (OR = .46 at p ≤ .01). In addition, respondent’s age was significant only for rural residents. However, the relationship was that of an inverted U-shape with those aged 20 - 29 more likely to have used a condom at their last non-marital sexual in- tercourse than younger and older respondents. However, the im- pact of age on condom use was only statistically significant among rural residents; among women those aged 20 - 29 were about two times (OR = 1.91 at p ≤ .10) more likely to have used a condom at their last non-marital sexual intercourse as compared to women aged 30 and older. Among men in rural areas, all Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 174  S. R. KIMUNA, Y. K. DJAMBA those below age 30 were significantly more likely to have used a condom at their last non-marital sexual experience as com- pared to the older men (OR = 2.50 at p ≤ .01 and OR = 3.55 at p ≤ .001 for age-groups 15 - 19 and 20 - 29 respectively). Ethnicity and religion were significantly associated with condom use only for men in rural areas. Compared to men from the Kikuyu ethnic group, men from other ethnic groups were nearly two times (OR = 1.73 at p ≤ .05) more likely to have used a condom at their last non-marital sexual intercourse. As for religion, non-Muslims were about five times (OR = 4.98 at p ≤ .05) more likely to have used a condom at their last non-marital sexual intercourse as compared to Muslim men. On the other hand, age at first sex had significant impact on condom use only for men in urban areas. Urban men who de- layed the onset of sexual activity were significantly more likely to use a condom at their last non-marital sexual intercourse than those who had sex before age 15 (OR = 2.05 at p ≤ .01). Finally, knowing someone who had HIV or died of AIDS affected condom use. Results in Table 5 show that regardless of place of residence and sex, respondents who were acquainted with people infected with HIV were more likely to use con- doms at their last non-marital sexual intercourse than those who had no knowledge of people with HIV. In urban areas, such impact is only significant for women. Compared to those who don’t know anybody who has HIV or died of AIDS, those who do, had a significantly low odds (OR = .54 at p ≤ .10) of having used a condom at their last non-marital sexual relation. In rural areas, the effect was significant for both sexes, although the magnitude of the impact was stronger for women (OR = .42 at p ≤ .05) than men (OR = .63 at p ≤ .10). Table 6. Adjusted odds ratios of having had sexual intercourse with more than one partner in the last 12 months by place of residence and by sex, KDHS 2003. Models Urban Rural Variables Women Men Women Men Non-migrant 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Migrant Urban-urban 1.73 (.72 - 4.14) 1.31 (.80 - 2.13) - - Rural-urban 1.33 (.66 - 2.71) 1.08 (.64 - 1.84) - - Urban-rural - - .76 (.40 - 1.46) 1.39 (.95 - 2.03)+ Rural-rural - - 1.51 (.80 - 2.85) 1.13 (.81 - 1.58) Perceived risk of getting HIV No 25.69 (3.50 - 188.46)*** 2.04 (1.34 - 3.10)* 2.12 (1.13 - 3.98)* 2.48 (1.76 - 3.49)*** Yes 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Age 15 - 19 .95 (.37 - 2.43) .45 (.22 - .94)* .75 (.35 - 1.61) .55 (.33 - .91)* 20 - 29 1.13 (.55 - 2.29) 1.13 (.73 - 1.75) 1.01 (.59 - 1.75) 1.10 (.76 - 1.58) 30+ 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Marital status Not currently married 2.51 (1.28 - 4.93)** 1.40 (.90 - 2.17) 1.53 (.84 - 2.78) 1.35 (.93 - 1.97) Currently married 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Education Less than High School 1.82 (.92 - 3.58)+ 1.54 (1.07 - 2.20)* 4.54 (1.61 - 12.79)** 1.60 (1.14 - 2.23)** High School or higher 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Ethnicity Other ethnic groups 1.34 (.63 - 2.87) 1.44 (.93 - 2.23) 1.87 (.87 - 4.02) 3.20 (2.05 - 4.98)*** Kikuyu 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Religion Other religious affiliation 3.50 (.79 - 15.44)+ .86 (.50 - 1.49) 2.23 (.68 - 7.33) 1.09 (.60 - 1.98) Muslim 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Age at first sexual intercourse At age 15 or later .65 (.29 - 1.43) .85 (.57 - 1.27) .42 (.43 - .70)*** .57 (.43 - .77)*** Before age 15 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Knows someone who has or died of AIDS No .67 (.29 - 1.56) .48 (.27 - .83)** .67 (.36 - 1.25) .89 (.64 - 1.23) Yes 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 Model X2 48.877*** 44.738** 48.887*** 99.983*** Number of cases 2467 1110 4879 2345 ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05; +p < .10. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 175  S. R. KIMUNA, Y. K. DJAMBA Sexual Experience with Multiple Partners The results in Table 6 show the likelihood that a respondent would have had sex with multiple partners in the 12 months before the survey. The independent variables included in these analyses are the perceived risk of being infected with HIV, socio-demographic characteristics, age at first sexual inter- course, and knowledge of someone living with HIV or who died of AIDS. Table 6 results show that migration was a significant corre- late of multiple sexual partners only among men living in rural areas. Among rural resident men, only urban-rural migrants were significantly more likely to have had sex with multiple partners than non-migrants (OR = 1.39 at p ≤ .10). In contrast, we found that respondents who did not consider themselves to be at risk of being infected with HIV were significantly more likely to have had sexual intercourse with multiple partners. This pattern was consistent for men and women in both rural and urban areas; but the most outstanding case was found among urban resident women with an odds ratio value of 22.69 (p ≤ .001). The age category showed teenagers to be somewhat different from the rest of the respondents in terms of their risk of having sex with multiple partners. Still, the effect was significant only for men for whom the likelihood of having had sex with multi- ple partners was significantly lower among teenagers compared to men aged 30 years and older (OR = .45 and .55, both at p ≤ .10, respectively in urban and rural areas) . Also, we found that marriage had only some protective effect among women in urban areas. For urban women, those who were married had lower risk of having had sex with multiple partners (OR = 2.51 at p ≤ .01). Interestingly, for both men and women in rural and urban areas, education was significantly associated with lower risk of having had sex with more than one partner in the last 12 months. However, the magnitude of the effect was not the same across models. The strongest impact was found among rural women with less than high school education. For such women, the likelihood of having had sex with multiple partners in the 12 months before the survey was nearly five times higher (OR = 4.54 at p ≤ .01) compared to rural women with high school education or higher. The lowest, yet significant effect was ob- served among urban resident men with less than high school education (OR = 1.54 at p ≤ .05), in comparison to those with high school education or higher. The odds ratios for ethnicity show that the Kikuyu were less likely to have had sex with multiple partners, compared to other ethnic groups. Nonetheless, this ethnic effect was statistically significant only among men in rural areas (OR = 3.20 at p ≤ .001). Religion had only a marginally significant effect on the number of sexual partners among urban. For these women, being of Muslim religion greatly reduced the risk of sexual activity with multiple partners women (OR = 3.50 at p ≤ .10). As one would expect, having had first sexual intercourse at a younger age was associated with having had sexual experience with multiple partners even in this case where the timeframe was one year. However, this association was only significant in rural areas where both men (OR = .57 at p ≤ .001) and women (OR = .42 at p ≤ .001).who initiated sex at younger ages were more likely to have had more sexual partners in the last 12 months than those who delayed their debut of sexual inter- course. Ironically, for men in urban areas, knowing at least one person living with HIV or who died of AIDS significantly in- creased the likelihood of having had sex with multiple partners. This study set out to examine internal migration in Kenya and its effect on risky sexual behaviour as measured by the perceived risk of getting HIV, use of condom at last non-mari- tal sexual intercourse, and sexual intercourse with multiple partners. We argued that because migration exposes people to different cultural norms and values, migrants would be more likely than non-migrants to engage in risky sexual behaviour. However, our findings show only a marginal impact of urban- rural migration among rural residents. Overall, more respon- dents considered themselves to be at risk of being infected with HIV (little more than 60% of men and women in the sample). Such risk was consistently and statistically significantly higher among migrants than non-migrants, regardless of sex and place of residence. However, once socio-demographic characteristics and other correlates of sexual behaviour were introduced in the regression models, migration effect became statistically significant only for migrant women in rural areas. Even for such women, only those who moved from urban to rural areas were significantly more likely to perceive themselves at risk of HIV infection, compared to non-migrants. This may suggest that migrant women in rural areas are rela- tively more attractive in the local sexual network market hence their heightened perceived risk of HIV infection. As noted in Brokerhoff and Biddlecom (1999) study, there could be a number of explanations for these findings. First, rural migrant women may be moving away from kin, which may remove the behavioural constraints imposed by family and second, they may be moving to rural road sites and trading centres, where the forces of migration may further aggravate gender related inequalities by increasing women’s economic and physical exposure to casual or transactional sex as a survival strategy (Anarfi, 1993). As it has been noted elsewhere (Kimuna & Djamba, 2005; Hattori & Dodoo, 2007), we also found that marriage does not reduce the risk of having HIV in Kenya. This is probably be- cause married people have more resources and other qualities that are attractive in mate selection process. Likewise, our findings showed that education does not reduce the risk of be- ing infected with HIV in this sample. Despite the fact that most respondents reported fear of being infected with HIV, the majority still did not use condoms at their last non-marital sexual activity (53% for men and 75% for women). Moreover, the results from multivariate analyses in- dicate that there is no significant difference in condom use at last non-marital sexual activity by migration status. This may indicate either the presence of strong cultural norms against condom use, or that there is no significant difference in the knowledge and availability of condoms between urban and rural areas. The lack of migration effect on condom use in this analysis may also suggest that contraceptive knowledge and practices are well diffused across Kenya. It may also indicate a more circular nature of migration in which those involved don’t stay longer in place of destination. Another important finding is that marital status does not affect the chance of using condoms in non-marital relations and this was regardless of sex and place of residence. These results suggest that high risk sexual behaviour such as non-condom use with multiple sexual partners is very complex Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 176  S. R. KIMUNA, Y. K. DJAMBA and it needs to be approached from a socio-cultural standpoint. Moore and Oppong’s (2007) study noted the futility of advo- cating for people to use condoms, especially those in marriages. Their research found that people in steady relationships such as marriage did not believe in using condoms with their spouses, even when they knew of their sero-positive HIV status. The fact that condom use is not related to marital status even when mar- ried people engage in extramarital sex is alarming. Prevention programs should be multifaceted and take the environment in which people live and local realities into consideration. The migration effect was also non-significant in the models of the likelihood of having multiple sexual partners, except among men in rural areas. For the latter, we found that net of other control variables urban-rural male migrants were signifi- cantly more likely to have had sex with multiple partners than non-migrants. With the exception of unmarried women in urban areas who were significantly more likely to have had sex with multiple partners, we did not find a significant effect of mar- riage among men or women in rural areas. Again, this weak and generally lack of strong effect of marriage on risky sexual be- haviour shows that marriage per se is not a protective factor in the combat against HIV/AIDS. One encouraging finding is that those who consider them- selves to be at risk of being infected with HIV tend to limit the number of sexual partners. This result supports the popular view that knowledge is power. Yet, this was not translated into condom use at last non-marital sexual intercourse for urban residents. Education emerged as an important factor associated with low sexual risk. Although more educated respondents tended to see themselves at higher risk of being infected with HIV, they were significantly more likely to use condoms at last non- marital sexual activity and to report lower risk of having had sexual intercourse with multiple partners. This finding supports the idea that formal education is a strong empowerment vari- able that leads to more responsible sexual behaviour. Likewise, knowing someone who had HIV or died of AIDS seems to raise awareness about HIV risk and to lead to better likelihood of condom use in an extra-marital relationship. We also found that delaying the onset of sexual intercourse helps to lower risky sexual behaviour. Respondents who had their first sexual intercourse at age 15 or later were significantly less likely to see themselves as being at risk of HIV infection. Such respondents were also more likely to use condoms at their last non-marital sexual activity and were less likely to have had sex with multiple sexual partners in the 12 months before the survey. This result suggests that delayed sexual activity may result in more knowledge and safer sexual practices. Other cultural factors, such as religion and ethnicity also played some role in risky sexual behaviour, although their effects were not all consistent across sex and place of residence. Overall, this study suggests that there is little or no signifi- cant difference in sexual behaviours between migrants and non-migrants. This is probably because migration in Kenya is ongoing and quite complex. First, Kenya is a country of inter- nal migration as compared to other nations in the region (Choi, 2003). As shown in this study, more than half of the respon- dents in the sample were migrants. Second, Kenya is character- ised by unique ethnic groups that have distinctive cultural norms that have specific effects on sexual behaviours. As a result, the findings from this study must be used with caution when comparing to other regions of the world. Nonetheless, the lack of strong effects of migration on the sexual risk and sexual behaviour variables examined here sug- gests that efforts to reduce risky sexual behaviour should target all segments of the population, regardless of their migration status and place of residence. Acknowledgements This paper was presented at the International Organization of Social Sciences and Behavioural Research, the spring 2012 conference. Thanks also to Tawanda Blackmon and Erin Brown, respectively research assistant and program assistant at the Center for Demographic Research at Auburn University at Montgomery, for helping with the preparation of the statistical tables. The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions. REFERENCES Anarfi, J. K. (1993). Sexuality, migration and AIDS in Ghana: Asocio- behavioural study. Health Transition Review, 3, 45-67. Aral, S. O., & Peterman, T. A. (1996). Measuring outcomes of behav- ioral interventions for STD/HIV prevention. International Journal of STD and AIDS, 7, 30-38. doi:10.1258/0956462961917753 Barnett, T., & Whiteside, A. (2006). AIDS in the twenty-first Century: Disease and globalization (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Palgrave Mac- millan. Bessinger, R., Akwara, P., & Halperin, D. (2003). Sexual behavior, HIV and fertility trends: A comparative analysis of six countries. USAID measure evaluation project. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina. Brockerhoff, M., & Biddlecom, A. E. (1999). Migration, sexual behav- iour and the risk of HIV in Kenya. International Migration Review, 33, 833-856. doi:10.2307/2547354 Camlin, C. S., & Chimbwete, C. E. (2003). Does knowing someone with AIDS affect condom use? An analysis from South Africa. Edu- cation and Prevention , 15, 231-244. doi:10.1521/aeap.15.4.231.23831 Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) [Kenya], Ministry of Health (MOH) [Kenya], ORC Macro (2004). Kenya demographic and health survey 2003, CBS, MOH, and ORC Macro, Calverton, Maryland. Cleland, J., Boerma, J. T., Caraël, M., & Weir, S. S. (2004). Monitoring sexual behaviour in general populations: A synthesis of lessons of the past decade. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 80, ii1-ii7. doi:10.1136/sti.2004.013151 Choi, S. Y. P. (2003) Report of the INDEPTH Migration and Urbani- sation Workshop (21-24 January 2003). Gauteng: Centre for Health Policy, Witswaterand. Djamba, Y. K. (2003). Gender differences in motivations and intentions to move: Ethiopia and South Africa compared. Genus, LIX, 93-111. Fishbein, M., & Pequegnat, W. (2000). Evaluating AIDS prevention interventions using behavioral and biological outcome measures. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 27, 101-110. doi:10.1097/00007435-200002000-00008 Hattori, M. K., & Dodoo, F. (2007). Cohabitation, marriage, and “sex- ual monogamy” in Nairobi’s slums. Social Science & Medicine, 64, 1067-1078. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.005 Kimuna, S. R., & Djamba, Y. K. (2005). Wealth and extra-marital sex among men in Zambia. International Family Planning Perspectives, 31, 83-89. Leclerc-Madlala, S. (2003). Transactional sex and the pursuit of mod- ernity. Social Dynamics, 29, 213-233. doi:10.1080/02533950308628681 Longfield, K., Glick, A., Waithaka, M., & Berman, J. (2004). Rela- tionships between older men and younger women: Implications for STIs/HIV in Kenya. Studies in Family Planning, 35, 125-134. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2004.00014.x Lurie, M. N. (2006). The epidemiology of migration and HIV/AIDS in Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 177  S. R. KIMUNA, Y. K. DJAMBA Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 178 South Africa. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 32 , 649-666. doi:10.1080/13691830600610056 Lurie, M., Williams, B., Zuma, K., Mkaya-Mwamburi, D., Garnett, G., Sturm, A. W., Sweat, M. D., Gittelsohn, J., & Karim, S. S. (2003). The impact of migration on HIV transmission in South Africa: A study of migrant and non-migrant men and their partners. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 30, 149-156. doi:10.1097/00007435-200302000-00011 Mensch, B., Clark, W. H., Lloyd, C. B., & Erulkar, A. S. (2001). Pre- marital sex, schoolgirl pregnancy, and school quality in rural Kenya. Studies in Family Planning, 32, 285-301. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00285.x Moore, A.R., & Oppong, J. (2007). Sexual risk behaviouramong people living with HIV/AIDS in Togo. Social Science & Medicine, 64, 1057-1066. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.004 Ntozi, J. P. M., & Ahimbisibwe, F. (1999). Some factors in the decline of AIDS in Uganda. In J. C. Caldwell, J. P. M. Ntozi, & I. O. Oru- buloye (Eds.), The continuing HIV/AIDS epidemic in Africa (pp. 93- 107). Canberra: Health Transition Centre, Australian National Uni- versity. Nyanzi, S., Nyanzi, B., Kalina, B., & Pool, R. (2004). Mobility, sexual networks and exchange among bodaboda men in southwest Uganda. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 6, 239-254. doi:10.1080/13691050310001658208 Palekar, R., Pettifor, A., Behets, F., & MacPhail, C. (2008). Association between knowing someone who died of AIDS and behaviour change among South African youth. A IDS and Behaviour, 12, 903-912. Pison, G., Le Guenno, B., Lagarde, E., Enel, C., & Seek, G. (1993). Seasonal migration: Risk factor for HIV in rural Senegal. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 6, 196-200. Smith, K. P., & Watkins, S. C. (2005). Perceptions of risk and strate- gies of prevention: Responses to HIV/AIDS in rural Malawi. Social Science & Medicine, 60, 649-660. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.009 Topouzis, D. J., & Guerney, D. U. (1999). Sustainable agriculture: Rural development and vulnerability to the AIDS epidemic, UN- AIDS Best Practice Collection. Geneva: UNAIDS & FAO. UNAIDS (2006). 2006 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS. Wilson, D. (2000). Corridors of hope in Southern Africa: HIV preven- tion needs and opportunities in four border towns. Arlington: Family Health International. Wilson, F. (1972). Migration labour in South Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa. Zulu, E. M., Dodoo, F. N., & Ezeh, A. C. (2002). Sexual risk taking in the slums of Nairobi, Kenya, 1993-98. Population Studies, 56, 311- 323. doi:10.1080/00324720215933 |