J. Software Engineering & Applications, 2010, 3, 644-652 doi:10.4236/jsea.2010.37074 Published Online July 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jsea) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA The Need to Evaluate Strategy and Tactics before the Software Development Process Begins Samir Kherraf1, Laila Cheikhi2, Alain Abran1, Witold Suryn1, Eric Lefebvre1 1École de Technologie Supérieure, Université du Québec, Montréal, Canada; 2École Nationale Supérieure d’Informatique et d’ Analyse des Systèmes, Université Mohammed V-Souissi, Rabat, Maroc. Email: Samir.kherraf.1@ens.etsmtl.ca, Cheikhi@ensias.ma, {Alain.abran, Witold.suryn, Eric.lefebvre}@etsmtl.ca Received May 26th, 2010; revised June 18th, 2010; accepted June 26th, 2010. ABSTRACT Experience has shown that poor strategy or bad tactics adopted when planning a software project influence the final quality of that product, even when the whole development process is undertaken with a quality approach. This paper addresses the quality attributes of the strategy and tactics of the software project plan that should be in place in order to deliver a good software product. It presents an initial work in which a set of required quality attributes is identified to evaluate the quality of the strategy and tactics of the software project plan, based on the Business Motivation Model (BMM) and the quality attributes available in the ISO 9126 standard on software product quality. Keywords: Business Motivation Model, Quality of Strategy, Quality of Tactic, ISO 9126, Software Product Quality 1. Introduction In any engineering field, the establishment of the project plan is an important step. The plan includes, among other things, the goal and the objectives, and the means for attaining them. In software engineering in particular, the establishment of the project plan and the realization of that plan are required activities, and they contribute to the production of a high-quality software product. The goal and objectives represent the basis on which the development of software relies. It is also recognized that modifying software during or post-development in order to include new or changed requirements is easier than changing the mission for which the project was ini- tiated, the latter requiring a quality approach. The software engineering community has proposed and used several methods, techniques, and tools to sup- port software engineers in producing quality products, such as Extreme Programming, RUP, and the Agile method. Whether software engineers are developing new software products or enhancing existing ones, they have to rely on resources, techniques, and methods to meet the required project deadlines and do so within budget. Sometimes, even for highly experienced software devel- opment teams with the best technology using a develop- ment method efficiently, the outcomes in terms of soft- ware quality can be disappointing: if both the project resources and the project process are under control, the problem may reside in earlier phases, prior to the devel- opment process itself, with the software project plan, for example, which may not have been under control. Generally, the implementation of a particular software project is part of the global strategy of the organization, that is, the business plan that sets up the generic context of a specific project plan expressed in terms of strategy (goal) and tactics (objectives) [1]. Thus, a software pro- ject plan is a particular case of a business plan, which meets the requirements of a Business Motivation Model (BMM), as recommended in [1]. A set of quality attributes and measurements is pro- posed in ISO 9126 to evaluate the quality of the software product during its development phases. Can this set also be used to evaluate the quality of the strategy and tactics of the software project? Here, we propose a set of quality attributes to evaluate the quality of the strategy and tac- tics of the software project by adapting the quality attrib- utes proposed in ISO 9126 [2] to the context of the strat- egy and tactics activities of the BMM [1] for software projects. It is important to note that these BMM activities are to take place before the development of the software product itself begins. We stress that the main purpose of the work reported here is not to propose quality attributes for the BMM key concepts related to strategy and tactics in general, but to use these concepts in the context of software project plans, in particular in the initialization phase before be- ginning the development process.  The Need to Evaluate Strategy and Tactics before the Software Development Process Begins Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 645 This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents an overview of the BMM and its two key concepts: strategy and tactics. Section 3 presents an overview of ISO 9126 and related software product quality models and measurements. Section 4 presents some work related to the BMM and to ISO 9126. Section 5 illustrates the usefulness of the BMM in ISO 9126. Section 6 identifies quality attributes for the two key concepts of the BMM related to strategy and tactics, and Section 7 presents a discussion on the findings. 2. Business Motivation Model One of the recent developments in the Object Manage- ment Group (OMG) standards for modeling business plans is the specification of the Business Motivation Model (BMM), which “provides a scheme or structure for developing, communicating, and managing business plans in an organized manner” [1]. The main activities of the BMM are aimed at “identifying factors that moti- vate the establishing of business plans, defining the ele- ments of business plans, and indicating how all these factors and elements inter-relate” [1]. The BMM focuses on four key concepts: Ends, Means, Influencer, and Assessment, which constitute the two major areas of the BMM (Figure 1): The first area is related to the Ends and Means of business plans: “Ends...are things the enterprise wishes to achieve, for example, Goals and Objectives, and Means...are things the enterprise will employ to achieve those Ends, for example, Strategies, Tactics, Business Policies, and Business Rules.” The second area is related to the Influencers: “Influ- encers...shape the elements of the business plans, and the Assessments made about the impacts of such Influencers on Ends and Means (i.e. Strengths, Weaknesses, Oppor- tunities, and Threats).” Although the elements of the business plan are initially developed to address questions related to the business field from a business viewpoint, it is interesting to look at their applicability to the software project plan to address issues related to software quality, also from the business Figure 1. Business motivation model overview [1]  The Need to Evaluate Strategy and Tactics before the Software Development Process Begins Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 646 viewpoint. The basic idea of the BMM being “to develop a business model for the elements of the business plan before system design or technical development is begun” [1], these elements are also important to take into ac- count in the context of the software project plan before the development process is begun. Such elements will be used to determine the likely ways of obtaining a quality software product, and to indicate where economies in terms of budget and resources can be realized. The following sections focus on the elements related to strategy and tactics of the Means of the BMM and their usefulness in producing high-quality software. 2.1 Strategy and Tactics According to the BMM, “a Strategy represents the essen- tial Course of Action to achieve Ends—Goals in particu- lar. A Strategy usually channels efforts towards those Goals. A Strategy is more than simply a resource, skill, or competency that the enterprise can call upon; rather, a Strategy is accepted by the enterprise as the right ap- proach to achieve its Goals, given the environmental constraints and risks” [1]. In practice, developing a strategy consists in defining actions that must be coher- ent and executed correctly to achieve its goal. It is appli- cable to every type of action: political, economic, etc. Examples would be Microsoft’s strategy against Open Source software and its business strategy with companies producing computers (e.g. selling new computers with Windows pre-installed) to oblige customers to use and experiment with its new operating system. Next, a tactic is defined in the BMM as, “a Course of Action that represents part of the detailing of Strategies. A Tactic implements Strategies. For example, the tactic ‘Call first-time customers personally’ implements the Strategy ‘Increase repeat business’. Tactics generally channel efforts towards Objectives. For example, the Tactic ‘Ship products for free’ channels efforts towards the Objective ‘Within six months, 10% increase in prod- uct sales’” [1]. A tactic is therefore the set of actions that must be realized in order to contribute to achieving the strategy goal. As for the strategy, the tactic is applicable to every type of action: economic, commercial, sport, diplomatic, etc. In the example of Microsoft’s strategy to dominate the operating system market with Windows, the set of tactics could be as follows: 1) Enter into agreements with computer producers to sell computers with Windows pre-installed. 2) Develop useful software applications for specialists and the general public that function only in the Windows environment. 3) Ensure that only Microsoft Corporation will be able to improve its applications and its Windows operating system, and do this internally. 4) Make improvements to Windows according to the automated feedback of its users—via the Internet. As mentioned before, both strategy and tactics are ap- plicable to any type of project and in any type of disci- pline. Therefore, in the context of the software project plan, the strategy and tactics established for a particular project should be accepted by the project manager as the relevant approach to achieving the project goal and ob- jectives, depending on the context of the project. For example, the strategy and tactics adopted for a health sector software project and a defense software project are obviously different in some ways from those adopted for a game software project. 2.2 Difference between Strategy and Tactics The terms “tactic” and “strategy” are sometimes used incorrectly and often interchangeably. In a military con- text, tactics are conceptual actions associated with troop engagement which are implemented to achieve an objec- tive, while strategy is concerned with how those various actions are linked. A strategy is a plan of action designed to achieve a particular goal, whereas a tactic is a specific mission designed to achieve a specific objective. Michel de Certeau [3] defines a tactic as a calculated action de- termined by the absence of a proper “locus”, and it is deployed and organized by the laws of a foreign power. Tactics are isolated actions or events that take advantage of opportunities offered by gaps in a particular strategic system. He defines a strategy as an entity that is recog- nized as an authority, and is relatively inflexible because it is embedded in its proper locus, either spatially or in- stitutionally. In discussing the difference between strategy and tac- tics, Hall in [4] refers to: The teleological point of view: “Strategy supports the tactical objective, while the tactics supports the goals.” The pragmatic point of view: “A tactic is something you can change under your authority, but to change strategy you must ask your boss.” Some of the statements provided “as is” in the BMM document [1] showing the differences between the strat- egy (Goal) and tactics (Objectives) are presented in Ta- ble 1. The most common way to explain the differences be- tween strategy and tactics is a war analogy: a tactic is designed to win a battle and the strategy is designed to win the war. Another example would be a game (chess, for example): a tactic requires only the calculation of variants (I play it, he must play it, and then I play it, etc.), while the strategy relies on general heuristics and the intuition of the player. From Table 1, the bottom line states that “objectives should always be measurable”, which implies that objec- tives will have measurements. In the BMM, the informa- tive Appendix titled “Metrics for the BMM” states that “implicit in many areas of the Business Motivation  The Need to Evaluate Strategy and Tactics before the Software Development Process Begins Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 647 Table 1. Differences between strategy and tactics Differences between Strategy (Goal) and Tactics (Objectives) 1. Strategies usually channel efforts towards Goals. Tactics generally channel efforts towards Objectives. 2. Strategies tend to be longer term and broader in scope. Tactic tends to be shorter term and narrower in scope. 3. Strategies pair only with Goals, and Tactics only with Objectives. 4. There is a continuum from major Strategies that impact the whole of the business to minor Tactics with lim- ited, local effects. 5. Strategies are put into place to support the long-term Goals—i.e. a planning horizon that is typically several years or more—while Tactics are the Courses of Action implemented to deal with the shorter planning horizon of a year or less (the current operational plans). 6. Goal tends to be longer term, qualitative (rather than quantitative), general (rather than specific), and ongo- ing. Objective tends to be short term, quantitative (ra- ther than qualitative), specific (rather than general), and not continuing beyond its time frame (which may be cyclical). 7. Objectives should always be time-targeted and meas - urable. Goals, in contrast, are not specific in these ways. Model is the subject of metrics. In almost all organiza- tions, there are ‘things of interest’ that are heavily meas- ured and tracked. These metrics govern, control, and influence a wide range of important aspects of the or- ganization” [1]. However, the BMM does not provide a set of accept- able measures for measuring objectives, but only gives examples of some cases to show that it is possible to measure objectives, such as “quantify the Goal” and “be profitable”. The enterprise might, for example, set one objective to have a monthly net revenue of at least $ 5 million (by a specified date) and another to have an an- nual net revenue of at least $ 100 million (by a specified date)” [1]. The non availability of a set of measurements accepted by the BMM organization is symptomatic of the reality that “the enterprise will decide on many different things to be measured. Each of these measurements will have differing degrees of importance relative to the attainment of some Objective or set of Objectives” [1]. 3. ISO 9126 The ISO 9126 series was published between 2001 and 2004, under the general title: Information Technology— Software Product Quality. This set of ISO documents includes four parts [2,5-7]. The first part of ISO 9126 [2] is an international standard providing three views of quality: Internal view, which can be evaluated without the execution of the software during the design and coding phases; External view, which can be evaluated with the execution of the software during the testing and opera- tion phases; In-use view, which can be evaluated in terms of us- ing the software in a defined context and environment, and not in terms of its intrinsic properties. ISO 9126 also proposes a two-part quality model for these three quality views: an internal and an external quality model (shared) and an in-use quality model (indi- vidual). The other three parts of the ISO 9126 [5-7] are techni- cal reports, each of which proposes a set of non exhaus- tive lists of measures for each quality model. 3.1 Quality Model The first part of the ISO 9126 quality model is related to internal quality and external quality. Since internal qual- ity and external quality share the same structure of two hierarchical levels, they are represented in one model— see Figure 2. The second part concerns the quality-in-use model with only one hierarchical level—see Figure 3. According to ISO 9126, these parts of the quality model provide a set of characteristics and subcharacteris- tics that could be combined in order to specify the soft- ware quality requirements and to evaluate the software product quality throughout the whole software life cycle phases. Moreover, this model allows for the specification and evaluation of software product quality from different perspectives by different stakeholders of the software project, such as the user, the developer, the maintainer, the acquirer, the evaluator, and the quality manager. The three technical reports of ISO 9126 provide a cat- alog of measures for each quality characteristic (sub- characteristic) as a tool for evaluating software product quality. 3.2 Quality Measures Technical reports ISO TR 9126-2 and -3 [5,6] provide a list of measures for each subcharacteristic of the internal and the external quality model (Figure 2). ISO TR 9126-4 [7] provides a set of measures for each character- istic of the in-use quality model (Figure 3). The internal measures are applied to the intermediate product and deal with the static aspect of the software product, while the external measures are applied to the final product and deal with the dynamic aspect of the software. The quality-in-use measures reflect quality from the user’s point of view of the system containing the software: they aim to measure to what extent the user’s objectives are achieved. 4. Related Work Software product quality is widely discussed in standards,  The Need to Evaluate Strategy and Tactics before the Software Development Process Begins Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 648 Functionality PortabilityMaintainabilityEfficiencyReliability Suitability Accuracy Interoperability Security Functionality Compliance Adaptability Installability Co-existence Replaceability Portability Compliance Analysability Changeability Stability Testability Maintainability Compliance Time behaviour Resource Utilisation Efficiency Compliance Maturity Fault Tolerance Recoverability Reliability Compliance External and Internal Quality Usability Understandability Learnability Operability Attractiveness Usability Compliance Figure 2. Internal & external quality model of ISO 9126 [2] Figure 3. Quality-In-Use model of ISO 9126 [2] but the quality of the strategy and tactics of the software project plan that lead to this software quality are not ad- dressed. While the researcher and practitioner communi- ties propose quality attributes and measurements to evaluate the quality of the software product during its development (specification to delivery) [2,8-10], less work has been carried out on quality in the earlier phases of the software, like the initialization phase. This phase places the whole process in a business-level environment in which the mission should be realized in terms of re- quired “strategies for approaching goals, and tactics for achieving objectives” [1]. Various works discuss strategy, but in different con- texts. Ronan Fitzpatrick [11] introduces a new paradigm for software quality, which he calls strategic quality drivers for acquirers and suppliers of the software prod- uct. He presents six strategic quality drivers that impact the acquirer (procurer) of software, which are: Technical excellence, User acceptance, Corporate alignment, Statu- tory conformance, Investment efficiency, and Competi- tive support. He also proposes five other strategic quality drivers that impact the supplier (producer), which are: Quality management, Development excellence, Domain specialty, Corporate accreditation, and Competitive ex- cellence. This approach, the Software Quality—Strategic Driver Model, is an excellent foundation for the aca- demic syllabus for the study of software quality, and represents an opportunity for quality thinking to be ap- plied at a strategic level. Alex Wright [12] reviews the relationship between quality and strategy. In his view, quality “has failed to influence organizations’ strategy and strategic processes due to its continued operational bias; and the traditional calls for quality to be part of an organization’s strategy are misguided and originate from our own limited per- ception of quality as essentially operational.” He rec- ommends that quality be integrated by academic re- searchers and practitioners into the strategic process of the organization and be part of an organization’s strategy, but not a contributor to it. The Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (MBNQA) [13] is widely recognized in the USA. It con- sists of seven interrelated categories that comprise the organizational system for performance and excellence. This model is used to assess the quality status of organi- zations with a focus on the relationships between leader- ship, information and analysis, human resource planning, process quality, and the customer. It does not recommend any method on how an organization should develop and deploy an excellent strategy, but does encourage organi-  The Need to Evaluate Strategy and Tactics before the Software Development Process Begins Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 649 zations and their quality practitioners to consider the re- lationship between strategy and quality. The European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM) has proposed the Organizational Excellence Model [14], a non prescriptive framework based on nine criteria. Five of these criteria are related to “Enablers” and four to “Results”. The purpose of this framework is to explain the connections between what an organization does (Enablers) and the outputs it is able to achieve (Re- sults). The model is also used to define what resources and capabilities are necessary in order to deliver on the organization’s strategic objectives. This model is seen as endorsing a cyclical approach to improvement. Moreover, quality from the business perspective is discussed in [15] in the context of the TL9000 standards, and not the BMM standard. The authors suggest an inte- grated life cycle quality model, referred to as the “com- plement model for software product quality”. The ap- proach proposed in [15] combines the high-level quality view of the TL9000 Handbook and the detailed view from ISO 9126. 5. BMM and ISO 9126 in the Software Life Cycle The three ISO’s quality views concern the “Product and the User views” of the software product during its de- velopment and when it is delivered to the final user. What is also needed is a view of the quality of the soft- ware from a business perspective, which should be de- fined very early on in the software project plan, before the project approval stage. This business view of quality should be part of the BMM strategy and related tactics, and be supported by it. Therefore, the business view of quality should be inte- grated into the BMM plans, that is, during the “initializa- tion” of each new software project plan (Figure 4). As mentioned before, it is claimed that ISO 9126 is applicable to all types of software projects and makes it possible to evaluate the quality of the software product during all the phases of the software life cycle. The qualities of the “Product development view” and “Final product view” are discussed in the ISO 9126 standard, and a set of quality characteristics is proposed. The purpose there is to address the first view, “Product initialization”, which is very important for any project in any engineering field. The goal and objectives have to be identified in the project plan thoroughly and without am- biguity, and the means of achieving them should also be identified. These means are strategy and the related tac- tics. Moreover, according to ISO 9126, the quality charac- teristics of a software product are described as “external” and “internal” quality characteristics that the software product must satisfy to obtain a final product. This qual- ity is expressed in terms of “in-use” quality characteris- tics. What is needed is the set of quality characteristics of strategy and tactics that contribute to the quality of the software product. In the next section, we present the set of quality characteristics of strategy and tactics of the software project plan that should be considered before starting to develop the software product. 6. Quality Attributes for Strategy and Tactics The ISO 9126 documents are used to identify the quality attributes of the strategy and the tactics of the software project plan. Those attributes are presented in the fol- lowing sections. 6.1 Quality Attributes for Strategy As far as the BMM business plan is concerned, a strategy in the context of the software project plan also represents Figure 4. Views of quality in the software life cycle  The Need to Evaluate Strategy and Tactics before the Software Development Process Begins Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 650 a proper approach that should be adopted in the long term to achieve its goal, taking into account the con- straints and risks posed by the environment. Referring to ISO 9126 [2], the results of the strategy—in terms of quality—appear not only in the good approach, but also in the quality approach used to produce the final software product in a defined context and environment—e.g. ISO 9126 Quality-in-Use. Therefore, the quality of the strategy should be achieved by the four quality characteristics of Qual- ity-in-Use —see Figure 3. The definition of these quality attributes is based on, and adapted from, those of the ISO Quality-in-Use quality model to the context of the soft- ware project plan strategy established for developing the software product: Effectiveness: This characteristic should make it possible to measure the accuracy and completeness of the realized strategy goal established for developing the software product. Effectiveness doesn’t concern the ways in which the goal is to be realized. Productivity: This characteristic should make it possible to evaluate the use of various resources in order to achieve the goal of the strategy adopted for developing the software product. Productivity enables measurement of the success of the strategy goal, and therefore the proposal of enhancements. Safety: This characteristic makes it possible to evaluate the strategy risk levels (negative impacts) that could affect the users, the software, the business, and the environment; for example, identification of emerging incidents capable of causing economic damage, such as competition, etc. Satisfaction: This characteristic should make it possible to satisfy the goal of the strategy and the actions taken to achieve it. Satisfaction concerns the degree of achievement of the established needs of the strategy. In the context of the software project plan, the quality of a strategy is defined here as the quality approach, characterized by effectiveness, productivity, security, and satisfaction, that an enterprise should adopt in the long term to achieve its goals in a defined context and envi- ronment. 6.2 Quality Attributes for Tactic As far as the business plan of the BMM is concerned, the tactics in the context of the software project plan also represent the set of guidelines to follow in order to achieve the goal and support the strategy. Therefore, the tactics—on the quality level—appear in the set of quality guidelines to follow in order to achieve the strategy goal. Moreover, according to the BMM, the strategy con- tributes to the identification of the tactics [1] and, ac- cording to the ISO 9126 [2] standard, the quality-in-use requirements contribute to the identification of the ex- ternal quality requirements of the software. Therefore, the quality of the tactic emerges on the set of external quality characteristics (Figure 2) that the tactic should satisfy in order to meet the strategy goal. From the set of ISO 9126 external quality characteris- tics, a set of quality attributes suitable for a tactic are identified and redefined for the context of the software project plan, as follows: Functionality: This characteristic focuses on what to do in order to satisfy the tactic’s objective. A tactic must not only be functional and useful, but it must also function in a defined context and meet established objec- tives (Suitability). Moreover, quality goes beyond whe- ther a tactic functions or not, to how well its application produces good performance or good indicators to be fol- lowed (Accuracy). Reliability: This characteristic concerns the degree of confidence of the tactic. A tactic must maintain a per- formance level when faced with faulty operation (Fault tolerance). It should not lead to the failure of its purpose, but to the achievement of its objective (Maturity). Usability: This characteristic is related to the level of use of the tactic by the users. A tactic must be suitable and easily comprehensible (Understandability), accom- panied by a well-documented process in order to facili- tate its application (Learnability). A tactic must also be operational (Operability) in order that it can be used in an adequate way for specific tasks. Efficiency: This characteristic focuses on the suit- able performances that the tactic should provide accord- ing to the resources used. An effective tactic allows the use of the essential resources: material, personal, budget, and planning required for its achievement (Resource utilization). Maintainability: This characteristic concerns the capacity of a tactic to be modified, enhanced, and adapted to the changes in the application domain. Thus, a tactic should be diagnosed: 1) to identify the causes of its failure (Analyzability), 2) to identify the solution and be able to implement the required modifications (Change- ability), and 3) to test these modifications (Testability) in order to resolve problems arising after the modifications and to ensure a stable tactic (Stability). Portability: This characteristic represents the capa- bility of the tactic to be used in different environments. A portable tactic is one that is adaptable in different strate- gies without the use of resources or actions other than those already prescribed (Adaptability). The use of two or more tactics together (Co-existence) is a very impor- tant factor in the realization of a strategy and includes several disciplines. Moreover, the capacity of the tactic to be used instead of another in the strategy for a differ- ent objective, but under the same conditions, is also im- portant (Replaceability). Compliance: The tactic should conform to the  The Need to Evaluate Strategy and Tactics before the Software Development Process Begins Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 651 guidelines and standards related to the various quality characteristics identified. It should be realized according to the rules of the application domain: the software. In the work reported here, the quality of a tactic is de- fined in the context of the software project plan as the set of quality guidelines related to the Functionality, Reli- ability, Usability, Effectiveness, Maintainability, and Portability that the tactic should satisfy in order to meet the strategy goal. 7. Summary This paper has addressed the issue of identifying and including quality attributes early in the software project plan, i.e. before starting to develop the software product. This issue is related to the key concepts of the strategy (goal) and tactics (objectives) of the BMM plan. In a software engineering project, these two concepts consti- tute a basic issue to tackle, whether for developing new software or for enhancing or redeveloping existing soft- ware. A software quality product is often considered in terms of the contractual needs to be achieved between the client and the developer. The focus is generally directed toward the software life cycle process, as described in ISO 9126. So, it is appropriate to address quality before the devel- opment process starts, that is, during the initialization phase when the goal (strategy) and the objectives (tactics) are established, to contribute effectively to the quality of the final software product. Good strategy and tactics are at the heart of successful software project plans in any organization. However, while there are a few different approaches to integrating quality into strategic and tactical thinking/planning, none have looked at including or evaluating the quality of the strategy and the quality of the tactics of the software project plan. The motivation of the work reported here is to improve the quality of the software by improving the quality of the strategy and the quality of the tactics. Therefore, in this paper, a set of quality characteristics for these two key concepts of the BMM was identified in the context of a software project plan. It was identified based on those provided in ISO 9126 and were redefined by adapting the ISO 9126 definitions to strategy and tactics. Table 2 groups together the various quality character- istics identified for the strategy and tactics. Therefore, in the context of the software engineering project plan: The quality of strategy is defined here as the quality approach, characterized by effectiveness, productivity, security, and satisfaction, that an enterprise should adopt in the long term to achieve its goals in a defined context and environment. The quality of a tactic is defined here as the set of quality guidelines, related to Functionality, Reliability, Table 2. Quality characteristics for strategy and tactics Strategy Quality characteristics Effectiveness Productivity Safety Satisfaction Tactics Quality characteristics Functionality: suitability, accuracy Reliability: maturity, fault tolerance Usability: understandability, learnability, operability. Efficiency: resource utilization Maintainability: analyzability, changeability, testability, stability Portability: adaptability, co-existence, replaceability Compliance Usability, Effectiveness, Maintainability, and Portability, that the tactic should satisfy in order to meet the strategy goal. Another issue addressed in this paper is the usefulness of including a new perspective in a software project plan: the business view, to set targets prior to beginning the development of the software project. Once the project has been completed, we can evaluate whether or not these established targets have been met, and, if so, to what extent. Moreover, such a view is important, since it places the whole process in a business-level environment in which the mission should be realized in terms of the required strategy (goal) and tactics (objectives). On the one hand, when developing new software in a non mature market or for an emerging market (the first time that type of software has been developed), there are no best practices, guidelines, or techniques that have al- ready been used and tested which can be adapted to the needs of the project. Therefore, the non consideration of the business view of quality will affect the quality of the software product during the development phase, not only from the business perspective, but also from that of the developers and end users. On the other hand, for a re- peatable type of project, even if best practices are avail- able, the business view of quality should also be empha- sized when choosing suitable practices, combining them, or improving them to meet the needs of the new project; that is, determining “what” the business wants to accom- plish and “how” it intends to accomplish it [1]. In contrast, evaluation of the quality of the strategy and tactics, that is, the goal and objectives respectively, requires the availability of measurements. While the BMM recognizes the usefulness of measures for evalu- ating the objectives, it does not provide a set of accepted measures to use. This can be justified from three points of view. The first point is that the notion of metrics, al- though recognized as an important discipline by the BMM, is presented only in an informative appendix,  The Need to Evaluate Strategy and Tactics before the Software Development Process Begins Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSEA 652 which needs to be reworked in order to incorporate it as a part of the BMM elements. The second point is the absence of quality attributes to enable evaluation of the usefulness or otherwise of the stated goal and objectives. In fact, a set of quality attrib- utes related to strategy and tactics has been identified in this paper. The third point is related to the difficulty of designing good measurements: “The metrics for an Ob- jective are established by the measures of performance of the Goal that the Objective quantifies. To be able to do this, an appropriate unit of measure for the metric must be determined for each Objective. The Objective then expresses the target value that the metric should attain in the timeframe specified. In that way, while a Goal sets the direction, its corresponding Objectives set the mile- stones to be attained in pursuing the Goal” [1]. As future work to validate the mapping of the ISO 9126 quality model and quality of strategy and tactics, research is being pursued to propose measurements, in- dicators, and criteria to measure, in practical cases, the quality attributes of the strategy and the tactics of a soft- ware project plan. REFERENCES [1] Object Management Group, “Business Motivation Model Specification,” September 2007. [2] ISO/IEC, “IS 9126-1, Software Engineering—Product Quality—Part 1: Quality Model,” International Organiza- tion for Standardization, Geneva, 2001. [3] M. de Certeau, “The Practice of Everyday Life,’’ Univer- sity of California Press, 2002. [4] J. Hall, “Tactics, Strategies, and Quality Words,” Busi- ness Rule Journal, 2005. [5] ISO/IEC, “TR 9126-2, Software Engineering—Product Quality—Part 2: External Metrics,” International Organi- zation for Standardization, Geneva, 2003. [6] ISO/IEC, “TR 9126-3, Software Engineering—Product Quality—Part 3: Internal Metrics,” International Organi- zation for Standardization, Geneva, 2003. [7] ISO/IEC, “TR 9126-4, Software Engineering—Product Quality—Part 4: Quality in Use Metrics,” International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, 2004. [8] B. W. Boehm, J. R. Brown and M. Lipow, “Quantitative Evaluation of Software Quality,” Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Software Engineering, IEEE Computer Society, Los Alamitos (CA), 1976, pp. 592- 605. [9] R. G. Dromey, “Concerning the Chimera [Software Qual- ity],” IEEE Software, Vol. 13, No. 1, 1996, pp. 33-43. [10] J. A. McCall, P. K. Richards and G. F. Walter, “Factors in Software Quality,” US Rome Air Development Center Reports, US Department of Commerce, Vol. 1-3, 1977. [11] R. Fitzpatrick, “Strategic Drivers of Software Quality: Beyond External and Internal Software Quality,” 2nd Asia-Pacific Conference on Quality Software, IEEE Computer Society, 2001. [12] A. Wright, “Quality’s Strategic Failure: A Review of the Key Literature,” Occasional Paper Series 2003, Univer- sity of Wolverhampton, 2003. [13] Baldrige National Quality Program, Criteria for Perform- ance Excellence, B.N.Q. Program, Editor, 2009-2010. [14] European Foundation for Quality Management, The EFQM Excellence Model 2010, EFQM, 2010. [15] W. Suryn, A. Abran and C. Laporte, “An Integrated Life Cycle Quality Model for General Public Market Software Products,” Software Quality Management XII Conference, British Computer Society, 2004.

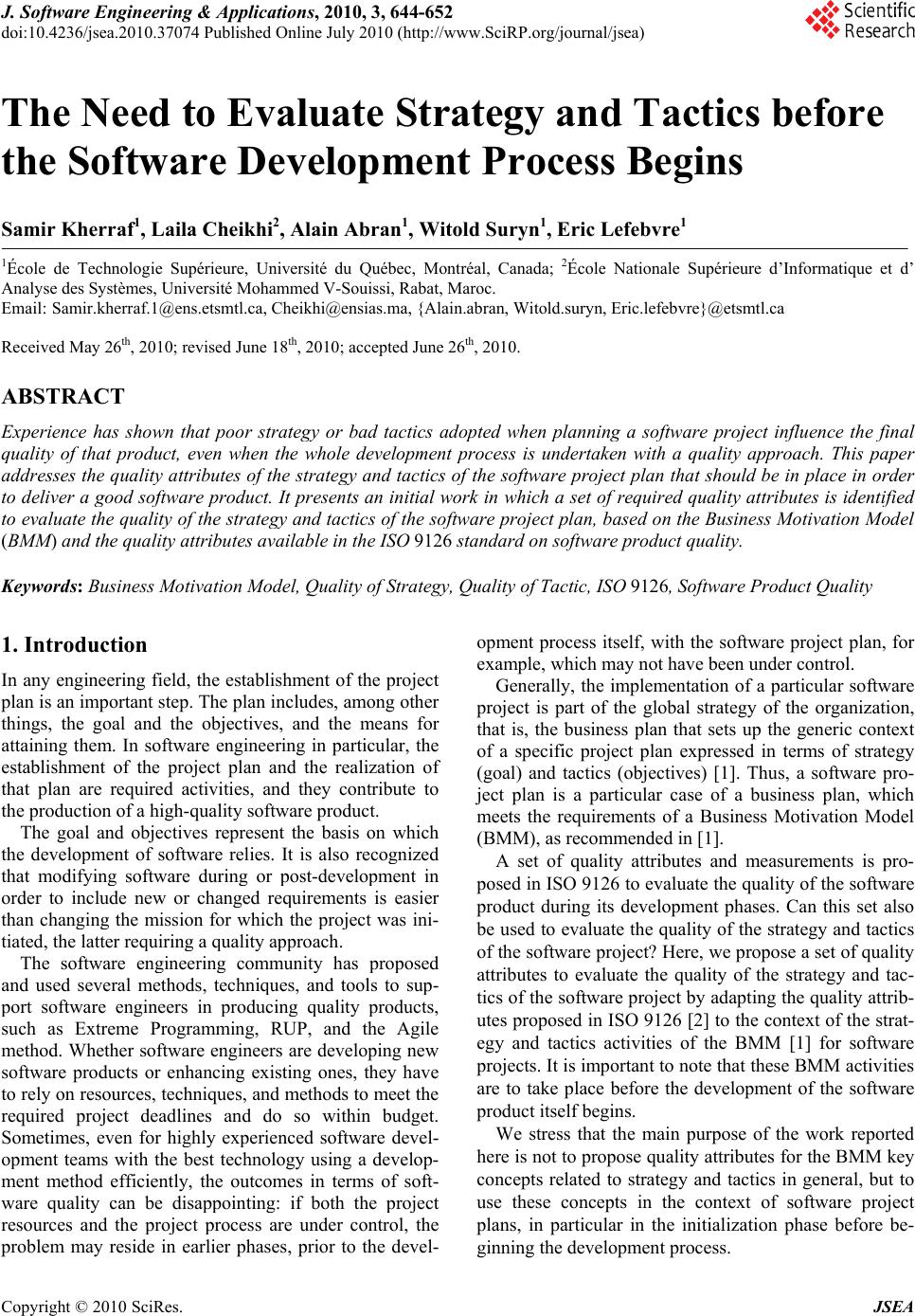

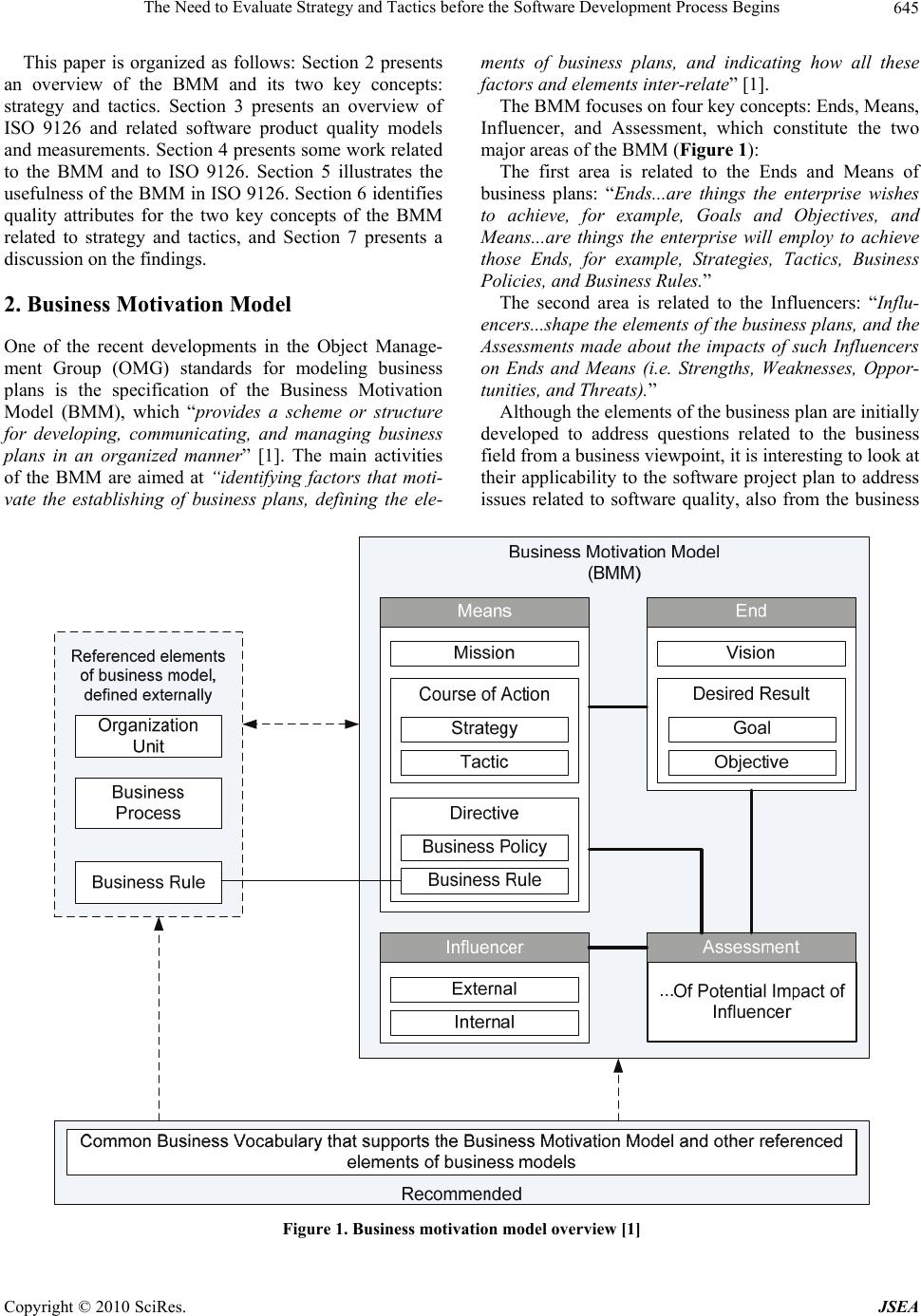

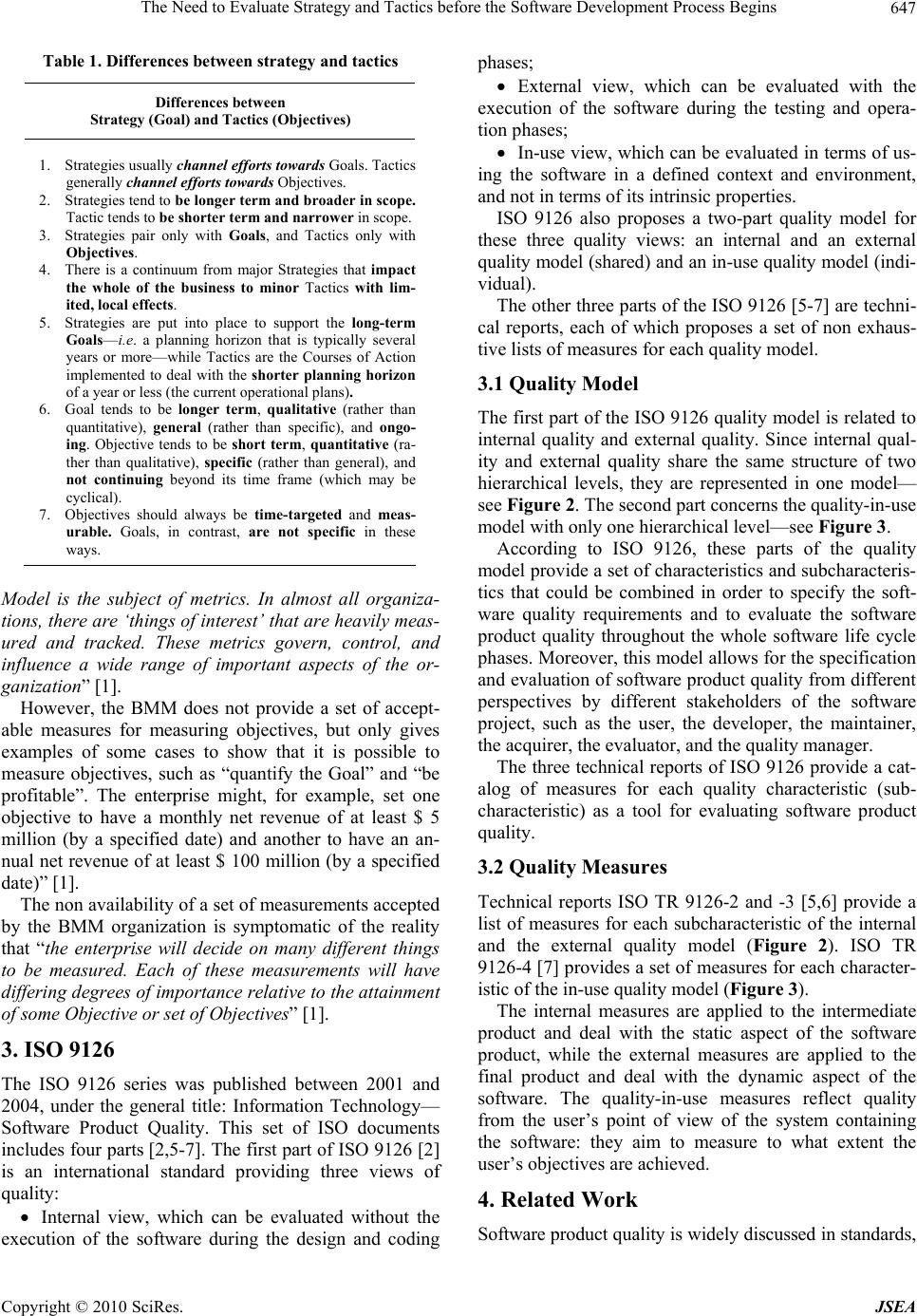

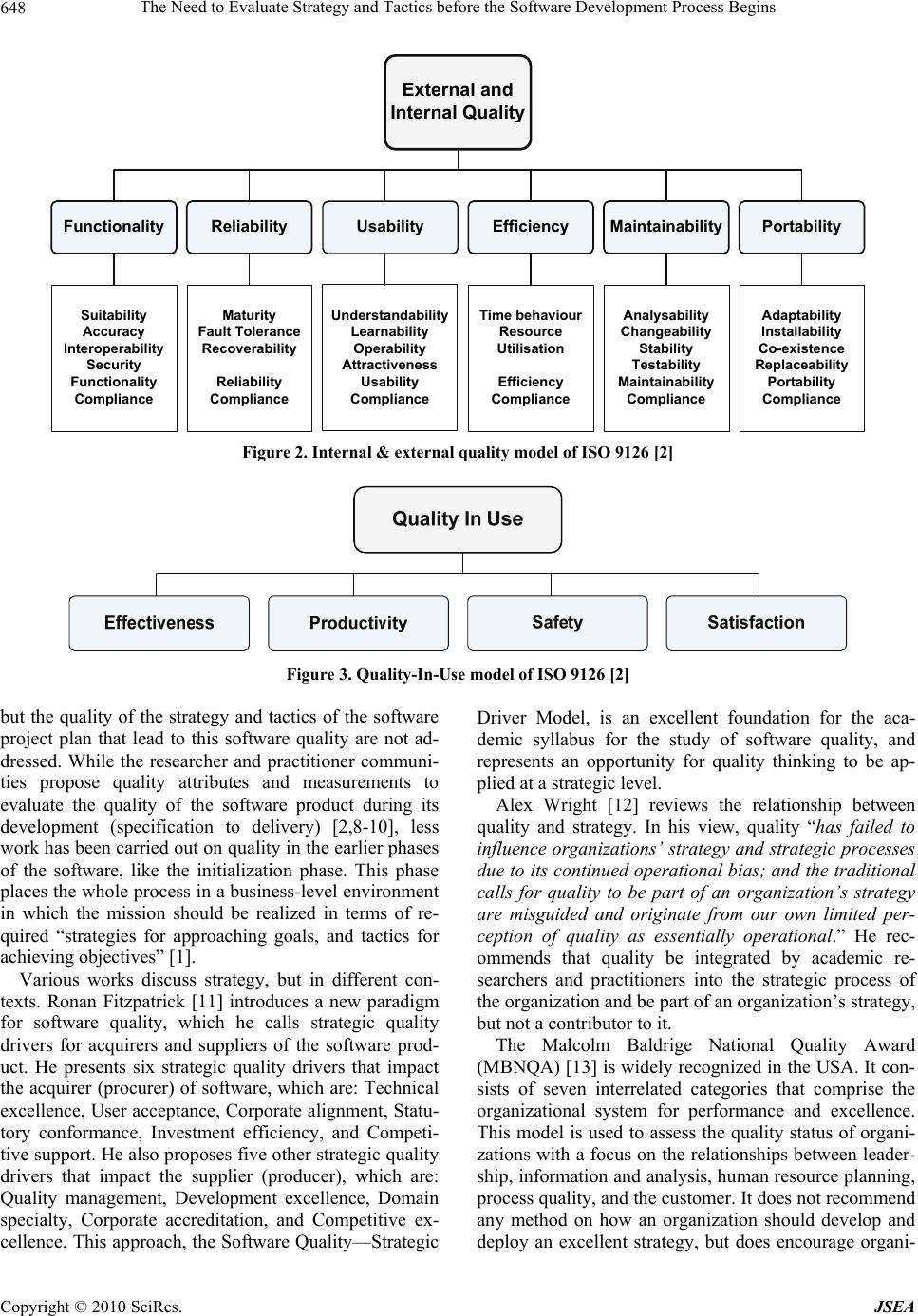

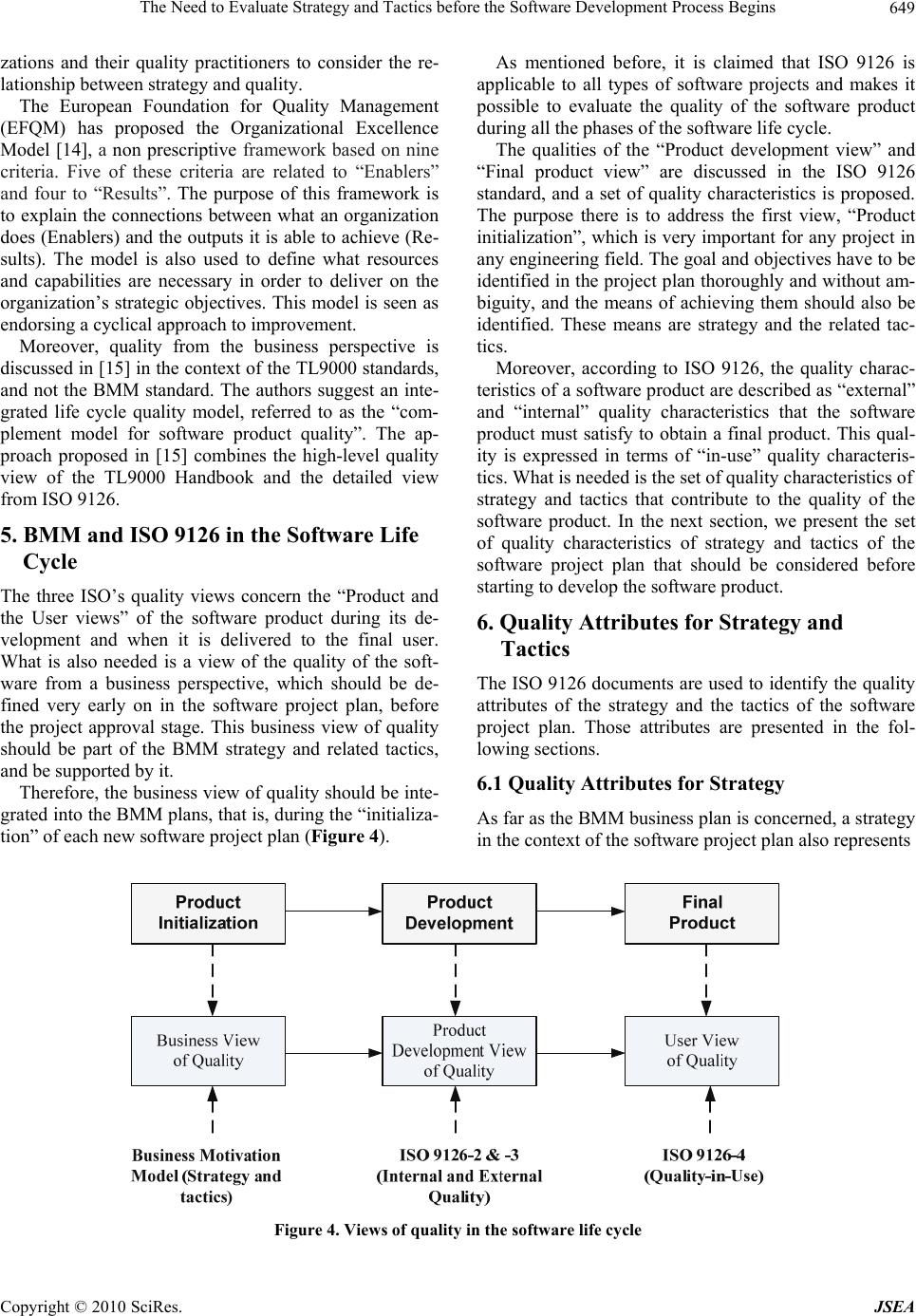

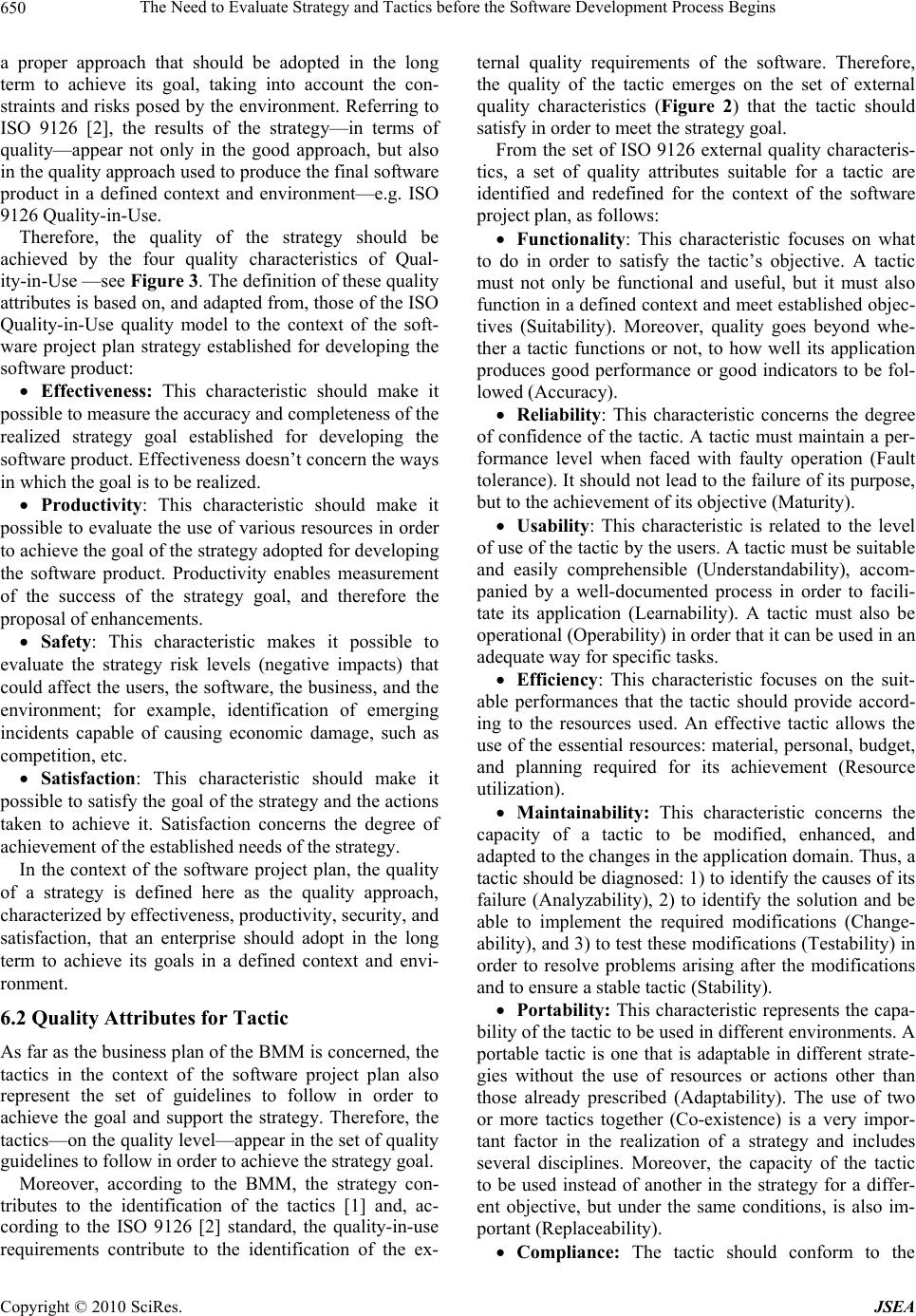

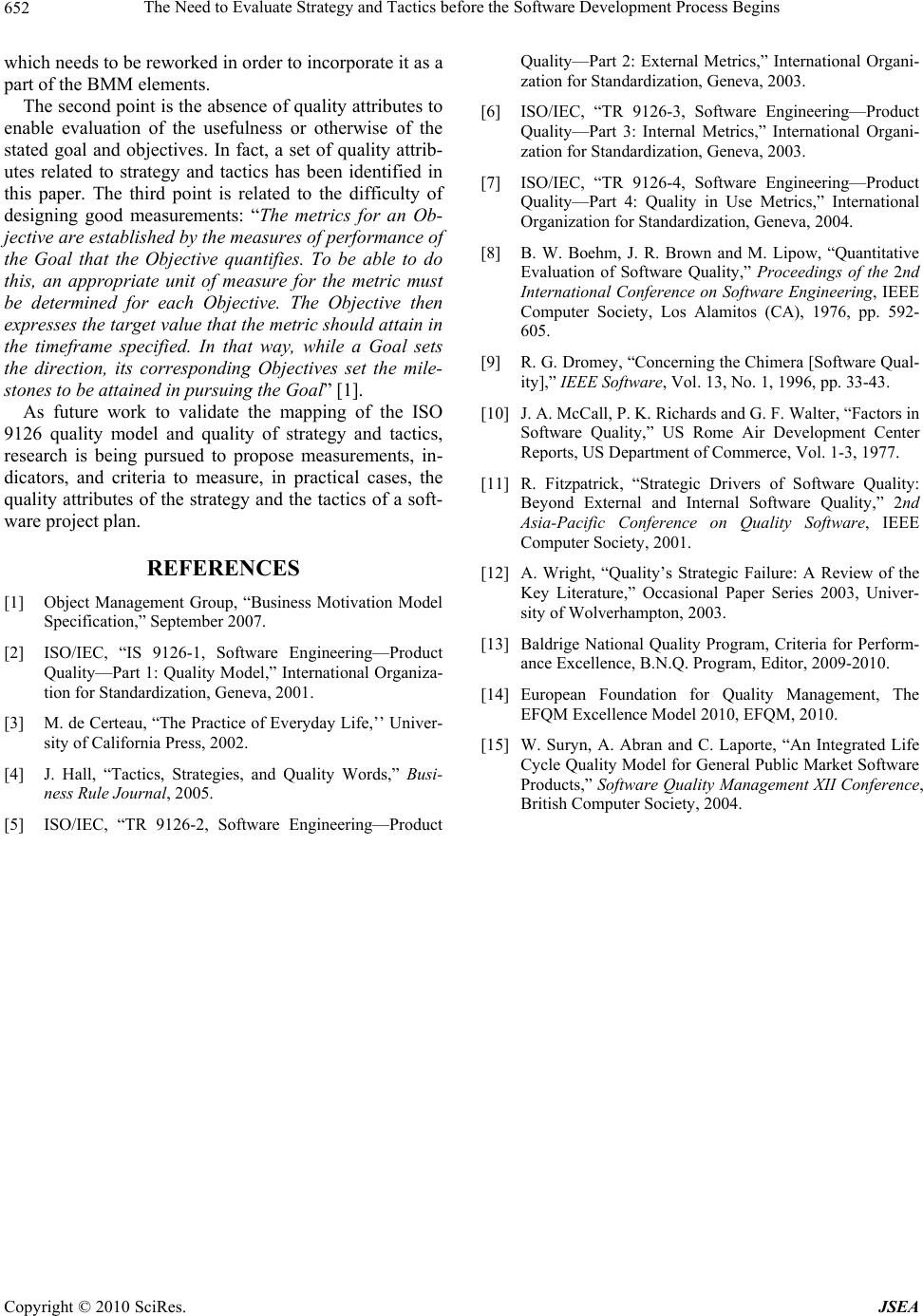

|