Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

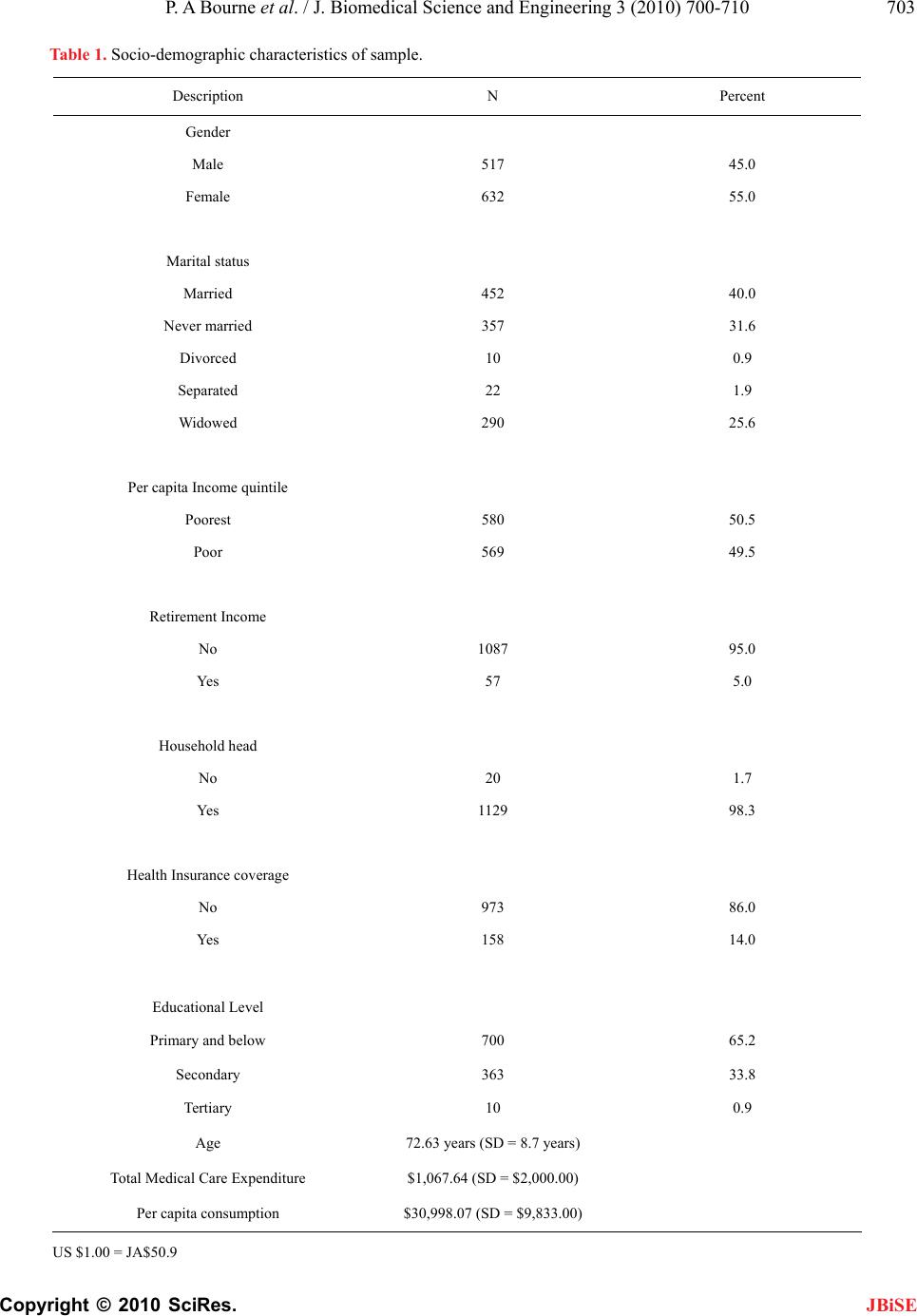

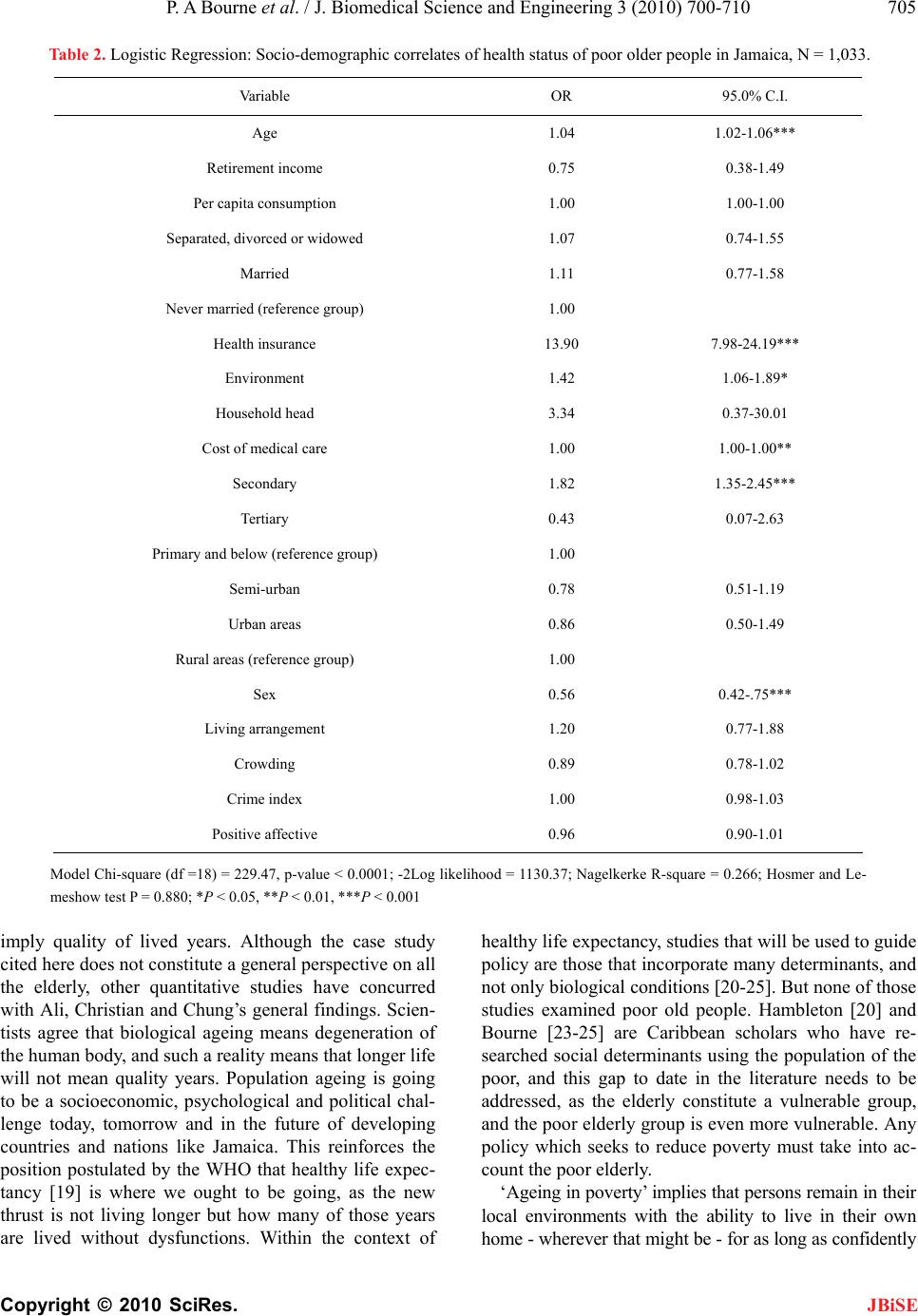

J. Biomedical Science and Engineering, 2010, 3, 700-710 JBiSE doi:10.4236/jbise.2010.37094 Published Online July 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jbise/). Published Online July 2010 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jbise Modelling social determinants of self-evaluated health of poor older people in a middle-income developing nation Paul A. Bourne Department of Community Health and Psychiatry Faculty of Medical Science University of the West Indies, Mona. Email: paulbourne1@yahoo.com Received 15 March 2010; revised 6 April 2010; accepted 8 April 2010. ABSTRACT Over the last 2 decades (1988-2007), poverty in Ja- maica has fallen by 67.5%, and this is within the context of a 194.7% increase in inflation for 2007 over 2006. It does not abate there, as Jamaicans are reporting more health conditions in a 4-week period (15.5% in 2007) and at the same time this corre- sponds to a decline in the percentage of people seek- ing medical care. Older people’s health status is of increasing concern, given the high rates of prostate cancer, genitourinary disorders, hypertension, diabe- tes mellitus and the presence of risk factors such as smoking. Yet, there is a dearth of studies on the health status of older people in the two poor quintiles. This study examined 1) the health status of those elderly Jamaicans who were in the two poor quintiles and 2) factors that are associated with their health status. A sample of 1,149 elderly respondents, with an average age of 72.6 years (SD = 8.7 years) were ex- tracted from a total survey of 25,018 Jamaicans. The initial survey sample was selected from a stratified probability sampling frame of Jamaicans. An admin- istered questionnaire was used to collect the data. Descriptive statistics were used to examine back- ground information on the sample, and stepwise lo- gistic regression was used to ascertain the factors which are associated with health status. The health status of older poor people was influenced by 6 fac- tors, and those factors accounted for 26.6% of the variability in health status: Health insurance cover- age (OR = 13.90; 95% CI: 7.98-24.19), age of re- spondents (OR = 7.98; 95% CI: 1.02-1.06), and sec- ondary level education (OR=1.82; 95% CI: 1.35-2.45). Males are less likely to report good health status than females (OR = 0.56; 95% CI: 0.42-0.75). Older people in Jamaica do not purchase health insurance cover- age as a preventative measure but as a curative measure. Health insurance coverage in this study does not indicate good health but is a proxy of poor health status. The demand of the health services in Jamaica in the future must be geared towards a par- ticular age cohort and certain health conditions, and not only to the general population, as the social de- terminants which give rise to inequities are not the same, even among the same age cohort. Keywords: Health Status; Self-Evaluated Health; Older Poor; Socioeconomic Factors; Jamaica 1. INTRODUCTION Factors determining the poor health status of the elderly in Jamaica can be viewed from the perspective of a socio-medical dichotomy. Such factors include poverty (resulting in one’s inability to access loans, quality edu- cation and health care), lifestyle (e.g. smoking, sedentary habits, sexual and dietary practices and physical inac- tiveity), resulting in prostate cancer, genitourinary dis- orders, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and premature death. In 2005, the World Health Organization began a thrust in examining the social determinants of health, and despite that reality there is a lack of literature in this regard on the elderly poor people in Jamaica. These pa- rameters were explored in the current research by using a sample of 1,149 elderly poor Jamaicans. The findings of this paper reveal that the cost of medical care is positively correlated with health condi- tions, and that economic constraints account for the de- cline in the elderly seeking medical care. Older people in Jamaica do not purchase health insurance coverage as a preventative measure but as a curative measure. Health insurance coverage in this study does not indicate good health, but on the contrary, it is a proxy of poor health status. It is also noted that income is positively corre- lated with a higher standard of living and life expectancy. In support of this claim, studies have shown that life expectancy in many developing countries [1], in par- ticular the Caribbean (Barbados, Guadeloupe, Jamaica, Martinique, Trinidad and Tobago) has exceeded 70 years,  P. A Bourne et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 700-710 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE 701 and they are now experiencing between 8-10% of their population living to 60+ years old. Life expectancy, which is a good indicator of the health status of a popu- lace, is higher in countries with high GDP per capita. This means that income is able to purchase better quality products [2], and indirectly affects the length of years lived by people. GDP per capita is used as an objective valuation of standard of living [3-12]. While a country’s GDP per capita may be low, life expectancy is high be- cause health care is free for the population. Despite this fact, material living standards undoubtedly affect the health status and wellbeing of people, as well as the level of females’ educational attainment [6] and the nu- trition intake of the poor. On the other hand, when there is economic growth, the society has more to spend on nutrition, health care, better physical milieu, better qual- ity food, safer sanitation and education. Good health is, therefore, linked to economic growth, something which is established in a plethora of studies by economists. Developing countries (a term synony- mous with poverty) do not only constitute low levels of democracy, civil unrest, corruption [13], high mortality and crude birth rates, but one must also include nutria- tional deficiency [14]. The WHO in 1998 put forward the position that 20% of the population in developing countries do not have access to enough food to meet their basic needs and provide vital nutrients for survival. In the Caribbean, and in particular Jamaica, poverty is typical, and many of the ills that affect other developing nations outside of this region are the same. The poor in this society are facing insurmountable challenges in buy- ing the necessary health care. In 2007, between 51 and 53% of those in the poor quintiles in Jamaica sought medical care, compared to 61-68% of those in the mid- dle-to-wealthiest quintiles. When those who had re- ported that they were ill were asked why they had not sought medical care, 51% of those in the poorest quintile indicated that they ‘could not afford it’, with 36.7% of those in the poor quintile giving the same response, and the percentage declines as the wealth of the person in- creases to the wealthiest quintile (7.7% of those in the wealthiest quintile). Over the last 2 decades (1988-2007), poverty in Ja- maica has fallen by 67.5% and this is in the context of a 194.7% increase in inflation for 2007 over 2006. Jamai- cans are reporting more health status in a 4-week period (15.5% in 2007) and at the same time this is associated with a decline in the percentage of people seeking medical care. Older people’s health status is of increase- ing concern, given the high rates of prostate cancer, genitourinary disorders, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and the presence of risk factors such as smoking in ear- lier life. Yet, there is a dearth of studies on the health status of older people in the two poor quintiles. Works which have examined the social determinants of health have used data for the population [2,3], but none emerged from a literature research using data for poor old people. This study examined 1) the health status of those elderly Jamaicans who were in the two poor quintiles, and 2) factors that are associated with their health status. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 2.1. Sample A sample of 1,149 elderly respondents was extracted from a larger survey of 25,018 Jamaicans. The sample was based on being 60 + years old, and being classified in the two poorest income categorizations. The initial survey sample (n = 25, 018) was across the 14 parishes, and was conducted between June and October 2002. The sample (n = 25,018 or 6,976 households out of a planned 9,656 households) was drawn using a stratified random sampling technique. This design was a two-stage strati- fied random sampling design, where there was a Primary Sampling Unit (PSU) and a selection of dwellings from the primary units. The PSU is an Enumeration District (ED), which constitutes of a minimum of 100 dwellings in rural areas and 150 in urban zones. An ED is an inde- pendent geographic unit that shares a common boundary. This means that the country was grouped into strata of equal size based on dwellings (EDs). Based on the PSUs, a listing of all the dwellings was made, and this became the sampling frame from which a Master Sample of dwellings was compiled, and which provided the frame for the labour force. The survey adopted was the same design as that of the labour force, and it was weighted to represent the population of the country. The survey was a joint collaboration between the Planning Institute of Jamaica and the Statistical Institute of Jamaica. The data were collected by a comprehensive administered questionnaire, which was primarily com- pleted by heads of households for all household mem- bers. The questionnaire was adapted from the World Bank’s Living Standards Measurement Study (LSMS) household surveys, and was modified by the Statistical Institute of Jamaica with a narrower focus, to reflect policy impacts as well. The instrument assessed: 1) the general health of all household members; 2) social wel- fare; 3) housing quality; 4) household expenditure and consumption; 5) poverty and coping strategies, 6) crime and victimization, 7) education, 8) physical environment, 9) anthropometrics measurement and immunization data for all children 0-59 months old, 10) stock of durable goods, and 11) demographic questions.  P. A Bourne et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 700-710 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE 702 Data were stored and retrieved in SPSS for Windows, version 16.0 (SPSS Inc; Chicago, IL, USA). The current study is explanatory in nature. Descriptive statistics were presented to provide background information on the sampled population. Following the provision of the aforementioned demographic characteristics of the sub- sample, chi-square analyses were used to test the statis- tical association between some variables, t-test statistics and analysis of variance (i.e. ANOVA) were also used to examine the association between a metric dependent variable and either a dichotomous variable or non- dichotomous variable respectively. Logistic regression was used to examine the statistical association between a single dichotomous dependent variable and a number of metric or other variables (Empirical Model). The logistic regression was used because in order to test the associa- tion between a single dichotomous dependent variable and a number of explanatory factors simultaneously, it was the best available technique. A p-value < 0.05 (two-tailed) was selected to indicate statistical signifi- cance in this study. Where collinearity existed (r > 0.7), variables were entered independently into the model to determine those that should be retained during the final model construction. To derive accurate tests of statistical significance, SUDDAN statistical software was used (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC), and this was adjusted for the survey’s complex sampling design. 2.2. Measure Social determinants. These denote the conditions under which people are born, grow, live, work and age, in- cluding the health system. Crowding: This is the total number of persons living in a room with a particular household. 1 Crowding = ni i h r , where i h is each person in the household and r is the number of rooms excluding kitchen, bathroom and verandah. Age: This is a continuous variable in years, ranging from 15 to 99 years. Old/Aged/Elderly: An individual who has celebrated his/her 60th birthday or beyond. Negative Affective Psychological Condition: Number of responses from a person on having lost a breadwinner and/or family member, loss of property, having been made redundant, failure to meet household and other obligations. Private Health Insurance Coverage (or Health Insur- ance Coverage) proxy Health-Seeking Behaviour, is a dummy variable which speaks to 1 for self-reported ownership of private health insurance coverage, and 0 for not reporting ownership of private health insurance coverage. Gender: Gender is a social construct which speaks to the roles that male and female perform in a society. This variable is a dummy variable, 1 if male and 0 if other- wise. Health conditions: The report of having had an ail- ment, injury or illness in the last four weeks, which was the survey period. This variable is a binary measure, where 1 = self-reported health status or illnesses, and 0 = otherwise (not reporting an illness, injured or dysfunc- tions). Poverty: In this study, the definition of poverty is the same as that used to estimate poverty in Jamaica. It is established from the basis of a poverty line. In order to compute the per capita poverty line in each geographical area (Kingston Metropolitan Area, Other Towns and Rural Areas), the cost of living for a basket of goods is divided by an average family of five. The basket of goods is established by the Ministry of Health based on the normal nutrients of the average family. Based on a per capita approach, there are five per capita income quintiles, with the poorest being below the poverty line (quintile 1) and the wealthiest being in quintile 5. Elderly, aged or old persons: Using the same defini- tion offered by the United Nations in the Report of the World Assembly on Ageing, July 26-August 6, 1982 in Vienna, that the elderly are persons who are 60+ years old. Older-poor (elderly-poor, aged-poor): All aged per- sons below and just above the poverty line (quintiles 1 & 2) in Jamaica. 3. RESULTS 3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Sample Consistent with the demographic characteristics of the ageing population, the sample was 1,149 of which there were 45% males (N = 517) compared to 55% females (N = 632). The mean age of the sample was 72.6 years (SD = 8.7 years). Most of the sample were married (40%, N = 452), 50.5% (N=580) of the sample were in the poor- est 20% of per capita income quintile, 95% (N = 1,087) were not receiving retirement income; those who were heads of households (98.3%, N = 1,129), those who had at most primary education (65.2%, N = 700) and those who did not have health insurance coverage (86.0%, N = 973) (Table 1). Thirty-seven percent (37.2%) of the sample indicated having had an illness in the last 4-week period. Ap- proximately 64% of the respondents indicated that they sought health care for their health conditions. When the respondents were asked if they had visited a health prac- titioner for any other reason during the last 12 months, 57.1% reported yes and 30.3% reported going for ‘regu- lar checkups’. Of those who indicated yes, 37.2% visited  P. A Bourne et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 700-710 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE 703 Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of sample. Description N Percent Gender Male 517 45.0 Female 632 55.0 Marital status Married 452 40.0 Never married 357 31.6 Divorced 10 0.9 Separated 22 1.9 Widowed 290 25.6 Per capita Income quintile Poorest 580 50.5 Poor 569 49.5 Retirement Income No 1087 95.0 Yes 57 5.0 Household head No 20 1.7 Yes 1129 98.3 Health Insurance coverage No 973 86.0 Yes 158 14.0 Educational Level Primary and below 700 65.2 Secondary 363 33.8 Tertiary 10 0.9 Age 72.63 years (SD = 8.7 years) Total Medical Care Expenditure $1,067.64 (SD = $2,000.00) Per capita consumption $30,998.07 (SD = $9,833.00) US $1.00 = JA$50.9  P. A Bourne et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 700-710 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE 704 public health care institutions, and 18.7% went to private clinics, compared to 5.7% who claimed that they at- tended both health care facilities. The typologies of ill- ness included colds (1.4%), diabetes mellitus (5.7%), hypertension (42.9%) and arthritis (31.4%), while 18.6% did not specify their health condition(s). Only 2% of the respondents had health insurance coverage; 61% pur- chased the prescribed medication; and 81.8% of those who indicated having not bought their medication re- ported that they could not afford it. The median number of days for how long an illness lasted was 7 days, with a median medical expenditure of US $7.85 (US $1.00 = Ja. $50.97). 3.2. Bivariate Correlation of Health Status and Age Cohort Of the 1,149 sample respondents for this study, 98.8% (N = 1,135) were used for the statistical correlation between health status and gender. Of the 1,135 respondents, there were 688 young-old, 327 old-old and 120 oldest-old poor Jamaicans. There was a correlation between the two above-mentioned variables – χ2 (df = 2) = 22.863, p-value < 0.001. On an average, 46% of the aged-poor (N = 523) reported that they had at least one illness/injury in the survey period. The most health status was reported by the oldest-old poor (59.2%, N = 71), 52.9% (N = 173) and the least by the young-old (40.6%, N = 279). Em- bedded in these findings is that for every 1 young-old poor who indicated that he/she had an illness/injury, there are 1.5 oldest-old and 1.3 old-old poor. 3.3. Multivariate Analysis The results of the multiple logistic regression model (in Table 2), were statistically significant [Model χ2 (df = 18) = 229.47; –2Log likelihood = 1130.37; p-value < 0.001]. Table 2 showed that 26.6% of the variances in the health status of older people in Jamaica were ac- counted for by the independent variables used in the multiple logistic regressions. The mold revealed that there were 6 statistically significant factors that deter- mined health conditions. These predictors are age (OR = 1.04, 95% CI = 1.02-1.06), health insurance coverage (OR = 13.90, 95% CI = 7.98-24.19), physical environ- ment (OR = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.06-1.89), cost of medical care (OR = 1.00, 95% CI = 1.00-1.00), secondary level education (OR = 1.82, 95% CI = 1.35-2.45) with refer- ence to primary and below education, and gender of re- spondents (OR = 0.56, 95% CI = 0.42-0.75). Controlling for the effect of other variables, the average likelihood of reporting illness/injury in a 4-week reference period de- clined by 17 times for those who had dysfunctions. The model had statistically significant predictor power (Model χ2 (df = 18) = 229.47; -Homer and Lemeshow goodness of fit χ2 = 3.739, P = 0.880), and correctly classified 70% of the sample (correctly classified 55.4% of those with dysfunctions and 82.3% of those without dysfunctions) (Table 2). The logistic regression model can be written as: Log (probability of dysfunctions/ probability of not reporting dysfunctions) = –4.185 + 0.039 (Age) + 2.632 (Health Insurance coverage, 1 = yes, 0 = no) + 0.348 (Physical Environment, 1 = yes, 0 = no) + 0.000 (Cost of Medical Care) + 0.598 (Secon- dary level education = 1, 0 = primary and below) – 0.581 (Sex). 4. DISCUSSION People are living longer [15], which means that on av- erage the elderly are living 15-20 years after retirement. Demographic ageing at the micro and macro levels im- plies a demand for certain services such as geriatric care. In addition to preventative care, there will be a need for particular equipment and products (i.e. wheelchairs, walkers etc.). Then there are future preparations for pen- sion and labour force changes, along with the social and economic costs associated with ageing, as well as the policy based research to better plan for the reality of these age groups. The World Health Organization (WHO), in explaining the ‘problems’ that are likely to occur because of population ageing, argues that the 21st Century will not be easy for policy makers as it is piv- otal in the preparation process to postpone ailments and disabilities, and the challenge of providing a particular standard of health for the populace [16]. What consti- tutes population ageing? Some demographers have put forward the benchmark of 8-10% as an indicator of population ageing [17]. Within the construct of Gavrilov and Heuveline’s perspective, the Jamaican population began experiencing this significant population ageing as of 1975 (using 60+ years for ageing) or 2001 (if ageing is 65+ years). The issue of population ageing will double come 2050, irrespective of the chronological definition of ageing, but what about the elderly poor health condi- tions? Let us examine the disparity between long life and quality of lived years. Ali, Christian & Chung [18] who is medical doctors, cite the case of a 74 year-old man who had epilepsy, and presented the findings in the West Indian Medical Journal. They write that “Elderly patients are frequently afflicted with paroxysmal impairments of consciousness, because they frequently have chronic medical disorders such as diabetes mellitus and hyper- tension, and can also be on many medications….Many elderly patients may have more than one cause for this symptom” [18]. The case presented by the medical doctors emphasizes the point we have been arguing that long life does not  P. A Bourne et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 700-710 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE 705 Table 2. Logistic Regression: Socio-demographic correlates of health status of poor older people in Jamaica, N = 1,033. Va ri a bl e OR 95.0% C.I. Age 1.04 1.02-1.06*** Retirement income 0.75 0.38-1.49 Per capita consumption 1.00 1.00-1.00 Separated, divorced or widowed 1.07 0.74-1.55 Married 1.11 0.77-1.58 Never married (reference group) 1.00 Health insurance 13.90 7.98-24.19*** Environment 1.42 1.06-1.89* Household head 3.34 0.37-30.01 Cost of medical care 1.00 1.00-1.00** Secondary 1.82 1.35-2.45*** Tertiary 0.43 0.07-2.63 Primary and below (reference group) 1.00 Semi-urban 0.78 0.51-1.19 Urban areas 0.86 0.50-1.49 Rural areas (reference group) 1.00 Sex 0.56 0.42-.75*** Living arrangement 1.20 0.77-1.88 Crowding 0.89 0.78-1.02 Crime index 1.00 0.98-1.03 Positive affective 0.96 0.90-1.01 Model Chi-square (df =18) = 229.47, p-value < 0.0001; -2Log likelihood = 1130.37; Nagelkerke R-square = 0.266; Hosmer and Le- meshow test P = 0.880; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 imply quality of lived years. Although the case study cited here does not constitute a general perspective on all the elderly, other quantitative studies have concurred with Ali, Christian and Chung’s general findings. Scien- tists agree that biological ageing means degeneration of the human body, and such a reality means that longer life will not mean quality years. Population ageing is going to be a socioeconomic, psychological and political chal- lenge today, tomorrow and in the future of developing countries and nations like Jamaica. This reinforces the position postulated by the WHO that healthy life expec- tancy [19] is where we ought to be going, as the new thrust is not living longer but how many of those years are lived without dysfunctions. Within the context of healthy life expectancy, studies that will be used to guide policy are those that incorporate many determinants, and not only biological conditions [20-25]. But none of those studies examined poor old people. Hambleton [20] and Bourne [23-25] are Caribbean scholars who have re- searched social determinants using the population of the poor, and this gap to date in the literature needs to be addressed, as the elderly constitute a vulnerable group, and the poor elderly group is even more vulnerable. Any policy which seeks to reduce poverty must take into ac- count the poor elderly. ‘Ageing in poverty’ implies that persons remain in their local environments with the ability to live in their own home - wherever that might be - for as long as confidently  P. A Bourne et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 700-710 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE 706 and comfortably possible. It inherently includes not hav- ing to move from one's current residence in order to se- cure the necessary support services in response to chang- ing needs. The ageing of Caribbean populations has been accompanied by a shift to chronic non-communicable diseases as major causes of morbidity. While overall na- tional trends have been reported, examination of local patterns of morbidity are increasingly important, as they have implications for the services to be provided, the mix of human resources, and the maintenance of health and functional status that facilitate ageing in place. Research has shown that crowding is strongly corre- lated with the wellbeing of the elderly (ages 60+ years) [23]; however this phenomenon, which is synonymous with poverty, does not influence the health status of poor elderly Jamaicans. Embedded in this finding is the fact that older people, in particular those in poor quintiles, interpret people around not as a negative force but as good social networking and interaction. What, then, in- fluences their health conditions? Poverty speaks to a particular environment; Pacione [26] showed that one’s physical environment affects one’s quality of life, and other scholars have agreed with this finding. The current study concurs with Pacione and others, in that the physical milieu is positively correlated with health conditions. Although Michael Pacione’s work was on the general population, Bourne’s works [23, 24] examined the elderly population (ages 60+ years) and found a negative association between physical envi- ronment and wellbeing, and this study concurred with that of the aforementioned researcher on the correlation between physical environment and health conditions. In this study, an important finding is to refine the correla- tion. Health insurance coverage is among the many indica- tors of the health-seeking behaviour of a populace. For the poor elderly, it is the most significant predictor of health conditions. The correlation is a strong positive one, indicating that health insurance coverage is a good proxy for more ill-health than good health. The current research found that those elderly poor who owned health insurance were 14 times more likely to report dysfunc- tions (or injuries) than those who did not. Health insur- ance is, therefore, a cost reducer for those who are aware that they are ill, and it is not in demand as a preventative measure. Arising from this fact is the role played by the costs of medical and curative care. Health is influenced by more than disease-causing pathogens. [27] The cost of medical care is positively correlated with health conditions, suggesting that the more dysfunctions (or injuries) that the elderly poor report, the more they are likely to spend on medical care. The elderly poor are prevented from seeking preventative care as against curative care. The latest data published by the Planning Institute of Jamaica and the Statistical Institute of Ja- maica [28] showed that 37.3% of elderly people are at least poor, with 20.6% falling in the poorest quintile. This further explains the rationale for the reduction in the demand for medical care within the context of a pre- cipitous increase in inflation in 2007 over 2006 (194%). With the steady rise in the cost of health care, as well as the increase in general food and non-alcoholic beverage prices in Jamaica, coupled with the fact that illness in older age requires care, the elderly poor are facing in- creasingly difficult times. The severity of the economic situation has seen a dramatic increase in the number of Jamaicans not seeking medical care for illness/injury. Although there is a decline in the general population seeking medical care (66%), more of the elderly do seek health care (72.3%) and this is owing to recurrent chronic illness which was shown to affect 74.2% of them [28]. Illnesses/injuries are precipitously affecting the elderly, and the data showed that self-reported illness for the elderly was 2.3 times more (36.6%) than in the gen- eral population (15.5%) [28]. In 2007, the elderly poor who constitute 38% of the poor-to-poorest in the popula- tion are mostly household heads (67.3%) and often un- employed, and within this context they must provide for their own health needs and those of their family, despite the harsh economic challenges and increased cost of health care. In 2002, 12.9% of Jamaicans were unable to afford medical care, and approximately 4 years later, the figure had risen by 162.8% to 33.9% in 2007. This is within the context of a 26.3% decline in poverty for the same pe- riod. Generally poverty has been falling over the last 2 decades in Jamaica, and inflation has fluctuated, justify- ing the increased amount spent on food and beverages [28], and the corresponding reduction in health care ex- penditure. In Jamaica remittances, which subsidize in- come for many households, have fallen by 7.7% and the reduction is 33% for those in the poor-to-the-poorest income quintiles. If the cost of medical care is positively correlated with the health status of the elderly poor, then can it be said that the poor elderly have more ill-health within the context of biological ageing and lowered ac- cess to employment income? Marmot [2] opined that there is a direct association between income and poor health, and this further helps us to understand the em- bedded health challenge of the elderly poor, as they must meet the increasing costs of medical care, cost of living, lower income, illnesses and severity of health conditions. On examining the health statistics for 2007 [28], the indication was that 50.8% of those in the poorest income quintile were unable to afford to seek medical care, and  P. A Bourne et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 700-710 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE 707 the figure was 36.7% of those in the poor quintile. In order to understand the severity of the situation regard- ing the aged-poor people in Jamaica, let us analyze the aforementioned within the context of the aged-poor. The official statistical publication for Jamaica for 2007 [28] showed that 20.6% percent of the elderly people are in the poorest quintile and 17.7% in the poor quintile which means that a little over half of the aged-poorest in Ja- maica (10.4%) were unable to afford medical care, and 6.5% of the aged-poor had financial difficulty affording medical care expenditure. One of the choices that must be made by the aged-poor in Jamaica is a switch from the formal medical care service to utilizing home reme- dies and over-the-counter medications, instead of visit- ing their personal physicians or health care facilities. Since 1988 when the Jamaican authorities began col- lecting data on self-reported health conditions, men have been reporting less health status than women [28]. The reporting of less illness does not mean that men are healthier than women, as the same statistical report [28] shows that women seek more medical care than men. Morbidity data for the sexes in Jamaica is typical, as in Mexico City, Havana and Santiago-Chile at least 60% of females compared to 50% of males aged 60+ years old reported fair-to-poor health [29]. Continuing, Buenos Aires, Montevideo and Bridgetown-Barbados had twice the figures of the aforementioned geo-political zones [29]. This is in keeping with women’s protective role of self, and their willingness to have a regard for their fu- ture health status accounts for a higher health status and not a lower one, although they report more dysfunctions than men. If life expectancy were to be used to proxy good health status, females are healthier than men given that they outlive them by 6 years in Jamaica and 8 years in the world. Furthermore, in 2000-2005, life expectancy for men was 69.5 years and 74.7 years for women, and come 2045-2050 they both would have gained an addi- tional 2 and one-quarter years more to their life span. The equal and constant rate of change in the life expec- tancy of both sexes in Jamaica highlights the fact that men do not enjoy better overall health status than their female counterparts. More years of life for both sexes means that the life course opens itself to coronary heart disease, stroke and diabetes mellitus, and so morbidity must be examined in this discourse. Studies done by the Ministry of Health reveal that of the five leading causes of mortality in Jamaica, which are malignant neoplasm, heart disease, diabetes mellitus, homicide and cerebrovascular diseases [30], more men die from more of the aforementioned conditions than women. Malignant neoplasms are 39% greater for men than women; cerebrovascular diseases are 14% higher for females than males; heart disease was 71.2 per 100, 000 for men and 66.1 per 100,000 for women; and dia- betes mellitus was 64% more for females than males [30]. The greater vulnerability of men to particular mor- tality than women is typical across Latin America and the Caribbean [29], pointing to gender bias (that is fem- inization) in visits to health care facilities, which are embedded in the life expectancy rates and visits to health care institutions. The matter of reporting less health status, once again, does not imply a healthier person, as health is not on a continuum, with ill-health on one ex- treme and good health on the other. Health is more in keeping with cyclical flow, and changes over the life course with time, experiences and socio-physical envi- ronmental conditions. Hence, asking about ill-health is not a good proxy for health status, as in 2007 a group of Caribbean scholars conducted a national representative prevalence survey of some 1,338 Jamaicans, and found that those who indicated themselves to be of the lower class had the least self-reported health status [13]. The discipline of gerontology – scientific inquiry into the biological, psychological, and social aspects of age- ing - has shown that ageing is not necessarily without increased health conditions; it is natural for aged people to complain and die more of dysfunctions than other age cohorts [31,32] and that is directly related to their basal metabolic rate [33] and the nature of the life course of the aged [34]. Here functional ageing is an explanation for the image of ageing, and it can be measured by nor- mal physical changes, diminished short-term memory, reduced skin elasticity and a decline in aerobic capacity. It is well established in the research literature that age is directly correlated with health status for the elderly, and in this study the finding concurs with the literature. The current research shows that age is the second most sig- nificant predictor of health status for the elderly poor, and explains why the disparity in poor health in Latin and America and the Caribbean is higher for older per- sons than younger people [29]. Population ageing is synonymous with more disability and more non-commu- nicable diseases such as malignant neoplasms, hyperten- sion, diabetes, and heart diseases than younger ages. Donald Bogue [35] noted that health problems increase with ageing, and that one’s health issues intensify with ageing. Therefore, an unhealthy lifestyle – tobacco con- sumption, physical inactivity, unprotected sex, and un- healthy diet - over the life course will affect the elderly in latter life, and the declining health of the elderly poor is the same within the sub-categories of the elderly – young-old, old-old and oldest old. Issues of the elderly cannot be discussed without an examination of area of residence. This study found no correlation between the aged-poor’s health status and area of residence. Using data since 1989 (from various  P. A Bourne et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 700-710 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE 708 issues of the Jamaica Survey of Living Conditions), population ageing is biased by gender as well as by spe- cific area of residence. Over the last decade (1997-2007), the number of elderly Jamaicans living in rural areas has declined from 54.3% to 46.6% (a rate of 14.1%). For the same period, the rate of increase of the aged populace in the Kingston Metropolitan Area (100% cities) was 19.5%, down from 27.2% (in 1997) while the increase in the aged population over the same period in Other Towns was 12.9% over 18.5% in 1997. Regarding the prevalence of poverty for the region (2007), rural pov- erty was 3.8 times more than that in Other Towns, and 2.5 times more than that in the Kingston Metropolitan Area. Despite the compounding economic challenges of poverty coupled with ageing, the poor-elderly in Jamaica do not experience a difference in their health status ow- ing to area of residence. Here the health issues of the aged poor are independent of their area of residence, suggesting that in the population the poor are age- residence insensitive. This contradicts research literature on the health status of the elderly which has shown a correlation between the aged and their areas of residence [23,24,48], indicating that the physical characteristics of the aged poor are the same in different areas of residence, and therefore do not account for any poor health, dis- ability, functional inability or psychological conditions. Like the WHO [35,36], the researcher believes that although ageing is a biological phenomenon, it cannot be due only to biological conditions, as ageing relates to bio-psycho-social [20,25,37-49] and environmental con- ditions [23-26], since people – biological organisms – must operate in a socio-physical milieu throughout their life span, and this demands an expansion of biological conditions in the ageing discourse. The very nature of gerontology must coalesce biopsychosocial and envi- ronmental conditions in assessing ageing and the health of the aged, which are in keeping with the WHO’s Con- stitution of 1948, and this has also been established in many Caribbean scholarships [20,23-25,42-49]. Within the context of the above-mentioned challenges for eld- erly people, when this is coupled with poverty which affects 10.2% of elderly Jamaicans (N = 29,794) in 2007, it intensifies the challenges experienced by elderly peo- ple. With the increased cost of food and non-alcoholic beverages, fuel and household supplies, housing and household operational expenses, the health status of the older-poor will continue to deteriorate, as they will not be able to afford health care services. The decline in medical care-seeking behaviour of Jamaicans speaks to the challenges of older people and the rise in instances of switching to alternative medicine. This is further intensi- fied by poverty; and rural poverty, which is more severe than that found in urban areas, [50] will further com- pound the challenges of the health status of the aged populace. Older people who are poor must operate within the same biopsychosocial and physical environ- ment during their lifetimes as other persons. Even among the WHO commissioned studies [51-53], as well as other studies on the social determinants of health [2,3,20-25], the population of the poor elderly were not examined. Likewise in the Caribbean, scholars have examined the social determinants of the population or the elderly population, with poverty being an inde- pendent variable [20,23-25]. Any policy that seeks to address the health status of the elderly poor must take into consideration, or concentrate and/or rely on, not only the population in general, but the cohort of the eld- erly in particular. The experiences and demands of the elderly are not the same as the general population, and the current study shows that social determinants of health are somewhat different for the general elderly population and the poor elderly cohort. The WHO [51] opined that the social determinants of health for the most part account for the health inequities between and within nations, which substantiates the differences that emerged between the elderly in other studies [20,23-24] and the current study of the poor elderly. These findings are far-reaching, and can be used to guide policy and re- search. The elderly-poor in Jamaica are experiencing ‘health poverty’ which cannot be alleviated by unre- searched policies or research policies on the general population, but by the elderly cohorts in particular. 5. CONCLUSION In summary, the number of elderly persons who reported health conditions in Jamaica is 3 times more than that for the nation (i.e. 12.6%), suggesting that health care ex- penditure for Jamaicans is substantially used to address health care needs for the aged population. With the number of elderly come 2025 estimated to be 14.5% over 10.9% for 2007, health care expenditure will be primarily absorbed in caring for this age cohort. Public health practitioners must begin programmes to deal with this pending reality. Ageing is a process which denotes that the high number of health conditions affecting the elderly would have started earlier, based on some of the decisions that they undertook (or did not) leading up to their current age. Hence, there is a need to have a public health campaign geared towards the promotion of healthy lifestyle practices for ages close to sixty years, in con- junction with one for children and for the working-age population. The programme should target check-ups, preventative care, signs of the onset of particular health conditions, and the distinction between ill health and good health care practices. The demand of the health services in Jamaica in the future must be geared towards  P. A Bourne et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 700-710 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE 709 a particular age cohort and certain health conditions, and not only to the general population, as the social deter- minants which give rise to inequities are not the same even among the same age cohort. 6. DISCLOSURE The author reports no conflict of interest for this study. 7. DISCLAIMER The researcher would like to note that while this study used secondary data from the Jamaica Survey of Living Conditions, none of the errors in this paper should be ascribed to the Planning Institute of Jamaica or the Sta- tistical Institute of Jamaica, but to the researcher. 8. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The dataset for this study was made available from the databank of SALISES (Sir Arthur Lewis Economic Institute), Faculty of Social Sciences, the University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica and for this the researcher is indebted and greater appreciate this gesture. REFERENCES [1] WHO, (1998) The world health report 1998. Life in the 21st century. A vision for all. WHO, Geneva. [2] Marmot, M. (2002) The influence of income on health: Views of an epidemiologist. Does money really matter? Or is it a marker for something else? Health Affairs, 21(2), 31-46. [3] Graham, H. (2004) Social determinants and their unequal distribution: Clarifying policy understanding. The Mil- bank Quarterly, 82(1), 101-124. [4] Marmot, M. and Wilkinson, R.G., Eds. (2003) Social determinants of health. 2nd Edition, Oxford University Press. [5] Kawachi, I. (2000) Income inequality and health. In Social Epidemiology, Ed., Berkman, L.K. and Kawachi, I., Oxford Univeristy Press, New York. [6] Kawachi, I., Kennedy, B.P., Lochner, K. and Prothrow- Stitch, D. (1997) Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. American Journal of Public Health, 87(9), 1491-1498. [7] Rojas, M. (2005) Heterogeneity in the relationship be- tween income and happiness: A conceptual-referent- theory explanation. Journal of Economic Psychology, 28(1), 1-14. [8] United Nations Development Programmed, (2006) Hu- man development report 2006. United Nations Deve- lopment Programme, New York: [9] Sen, A. (1998) Mortality as an indicator of economic success and failure. Economic Journal, 108(446), 1-25. [10] Roos, L., Magoon, J., Gupta, S., Chateau, D. and Veugelers, P.J. (2004) Socioeconomic determinants of mortality in two Canadian provinces: Multilevel model- ing and neighborhood context. Social Sciences and Medicine, 59(11), 1435-1447. [11] Murray, S. (2006) Poverty and health. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 174(7), 923-923. [12] Benzeval, M., Judge, K. and Shouls, S. (2001) Under- standing the relationship between income and health: How much can be gleamed from cross-sectional data? Social Policy and Administration Quoted in Benzeval, M. and Judge, K., Income and health: The time dimension. Social Science and Medicine, 52(4), 1371-1390. [13] Powell, L.A., Bourne, P. and Waller, L. (2007) Probing Jamaica’s political culture, Vol. 1: Main trends in the July-August 2006 leadership and governance survey. Centre of Leadership and Governance, Kingston, De- partment of Government, University of the West Indies, Mona. [14] WHO, (1998) The world health report, 1998. Life in the 21st century. A vision for all. WHO, Geneva. [15] Rowland DT, (2003). Demographic methods and con- cepts. Oxford University Press, Oxford. [16] WHO, (1998) Health promotion glossary. WHO, Ge- neva. [17] Gavrilov, L.A. and Heuveline, P. (2003) Aging of popu- lation. Quoted in the Encyclopedia of Population De- meny, P. and McNicol, G., Eds., Macmillan, New York. [18] Ali, A., Christian, D. and Chung, E. (2007) Funny turns in an elderly man. West Indian Medical Journal, 56(4), 376-379. [19] WHO, (2000) WHO issues new healthy life expectancy rankings: Japan number one in new ‘healthy life’ system. WHO, Washington D.C. & Geneva. [20] Hambleton, I.R., Clarke, K., Broome, H.L., Fraser, H.S., Brathwaite, F. and Hennis, A.J. (2005) Historical and current predictors of self-reported health status among elderly persons in Barbados. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 17(5-6), 342-352. [21] Smith, J.P. and Kington, R. (1997) Demographic and economic correlates of health in old age. Demography, 34(1), 159-170. [22] Grossman, M. (1972) The demand for health - A theo- retical and empirical investigation. National Bureau of Economic Research, New York. [23] Bourne, P. (2007) Determinants of well-being of the Ja- maican Elderly. Unpublished thesis, The University of the West Indies, Mona. [24] Bourne, P. (2007) Using the biopsychosocial model to evaluate the wellbeing of the Jamaican elderly. West In- dian Medical Journal, 56(suppl 3), 39-40. [25] Bourne, P.A. (2008) Health determinants: Using secon- dary data to model predictors of well-being of Jamaicans. West Indian Medical Journal, 57(5), 476-481. [26] Pacione, M. (2003) Urban environmental quality and human wellbeing – A social geographical perspective. Landscape and Urban Planning, 65(1-2), 19-30. [27] Abel-Smith, B. (1994) An introduction to health: Policy, planning and financing. Pearson Education, Harlow. [28] Planning Institute of Jamaica, (PIOJ), Statistical Institute of Jamaica (STATIN), (1989-2008) Jamaica survey of living conditions, 1988-2007. PIOJ, STATIN, Kingston. [29] United Nations, ECLAC, (2003) Older Person in Latin America and the Caribbean: Situation and policies. Re- gional Intergovernmental Conference on Ageing: To- wards a Regional Strategy for the Implementation in Latin America and the Caribbean of the Madrid Interna- tional Plan of Action on Ageing, UN Economic Commis- sion for Latin America and the Caribbean, Santiago,  P. A Bourne et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 700-710 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE 710 Chile. [30] The Health Promotion and Protection Division, Jamaican Ministry of Health (MOH), (2005) Epidemiology profile of selected health status and services in Jamaica, 1990-2002, MOH, Kingston. [31] Wu, D., Cypser, R., Yashin, A.I. and Jonson, T.E. (2008) The U-shaped response of initial mortality in caenor- habditis elegans to mild heat shock: Does it explain re- cent trends it human mortality. The Journal of gerontol- ogy: Biological Sciences, 63(7), 660-668. [32] Raynaud-Simon, A., Kuhn, M. and Moulis, J. (2008) Tolerance and efficacy of a new enteral formula specifi- cally designed for elderly persons: An experimental study in the aged rat. The Journal of Gerontology: Biological Sciences, 63(7), 669-677. [33] Ruggiero, C., Metter, E.J., Melenovsky, V., Cherubini, A., Najjar, S.S., Ble, A., Senin, U., Longo, D.L. and Ferrucci, L. (2008) High basal metabolic rate is a risk factor for mortality: The Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. The Journal of gerontology: Biological Sciences, 63(7), 668- 706. [34] WHO, (2001) Life course perspectives on coronary heart disease, stroke and diabetes: Key issues and implications for policy and research. Summary Report of a Meeting of Experts, WHO, Geneva. [35] Bogue, D.J. (1999) The ecological impact of population aging. Essays in Human Ecology, 4, Social Development Center, Chicago. [36] WHO, (2002) Active ageing: A policy framework. WHO, Geneva. [37] Engel, G. (1960) A unified concept of health and disease. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 3(4), 459-485. [38] Engel, G. (1977) The care of the patient: art or science? Johns Hopkins Medical Journal, 140(5), 222-232. [39] Engel, G. (1977) The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129-136. [40] Engel, G. (1978) The biopsychosocial model and the education of health professionals. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 310(1), 169-181. [41] Engel, G. (1980) The clinical application of the biopsy- chosocial model. American Journal of Psychiatry, 137(5), 535-544. [42] Eldemire, D. (1995) A situational analysis of the Jamai- can elderly, 1992. The Planning Institute of Jamaica, Kingston. [43] Eldemire, D. (1997) The Jamaican elderly: A socioeco- nomic perspective & policy implications. Social and Economic Studies, 46(1), 175-193. [44] Eldemire-Shearer, D. (2003) Organization of long-term care services for seniors. Workshop Proceedings, Ageing Well: A Life Course Perspective, the University of the West Indies, Mona and WHO/PAHO Collaborating Cen- tre on Ageing and Health. [45] Eldemire, D. (1996) Older women: A situational analysis, Jamaica 1996. United Nations Division for the Ad- vancement of Women, New York. [46] Eldemire, D. (1994) The elderly and the family: The Jamaican experience. Bulletin of Eastern Caribbean Af- fairs, 19, 31-46. [47] Eldemire, D. (1987) The elderly – A Jamaican perspec- tive. In: Grell, Gerald, A.C., Ed., The Elderly in the Car- ibbean: Proceedings of Continuing Medical Education Symposium, University Printery, Kingston, Jamaica. [48] Eldemire, D. (2008) Ageing - The response: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. Inaugural Professorial Lecture, UWI, Mona, Jamaica. [49] Kalache, A. (2003) Active ageing: WHO perspective. Workshop Proceedings, Ageing Well: A Life Course Per- spective, The University of the West Indies, Mona and WHO/PAHO Collaborating Centre on Ageing and Health. [50] Henry-Lee, A. (2001) The dynamics of poverty in Ja- maica, 1989-1999. Social and Economic Studies, 51(1), 199-228. [51] WHO, (2008) The Social Determinants of Health. http:// www.who.int/social_determinants/en/ [52] Kelly, M.P., Morgan, A., Bonnefoy, J., Butt, J. and Berg- man, V. (2007) The social determinants of health: De- veloping an evidence base for political action. Final Re- port to World Health Organization Commission on the Social Determinants of Health from Measurement and Evidence Knowledge Network. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/mekn_ final_report_102007.pdf [53] Solar, O. and Irwin, A. (2005) Towards a conceptual framework for analysis and action on the social determi- nants of health. Commission on Social Determinants of Health, Geneva. |