Psychology 2012. Vol.3, No.8, 583-589 Published Online August 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.38087 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 583 Burnout Patients Primed with Success Did Not Perform Better on a Cognitive Task than Burnout Patients Primed with Failure Arno Van Dam1*, Ger P. J. Keijsers2, Marc J. P. M. Verbraak2,3, Paul A. T. M. Eling4, Eni S. Becker2 1GGZ-Westelijk Noord Brabant, Institute for Mental Health, Bergen op Zoom, Netherlands 2Radboud University Nijmegen, Behavioural Science Institute, Nijmegen, Netherlands 3HSK-Group, Arnhem, Netherlands 4Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behaviour, Radboud University Nijmegen, Nijmegen, Netherlands Email: *arno.van.dam@ggzwnb.nl Received May 1st, 2012; revised June 5th, 2012; accepted July 7th, 2012 Burnout patients perform poorer on cognitive tasks than healthy controls. A possible explanation for this decreased performance is a relatively permanent reduced motivation to expend effort. In a previous study, we failed to enhance the performance of burnout patients using a monetary incentive and positive feed- back. In an attempt to bypass cognitions about fatigue and performance, we tried to motivate healthy con- trols and burnout patients implicitly by priming participants with either success or failure prior to task performance. As expected, healthy controls primed with success outperformed healthy controls primed with failure. However, no differential priming effect was observed in burnout patients. This suggests that success priming fails to enhance performance in subjects with burnout. Keywords: Burnout; Cognition; Motivation; Performance; Prime; Success Introduction Burnout is a stress-related syndrome characterized by ex- haustion, occupational detachment, and reduced personal ac- complishment. Burnout results from prolonged periods of stress and from an inability to achieve personal goals. Burnout pa- tients frequently report reduced job satisfaction, physical com- plaints, especially fatigue, and impaired cognitive performance (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter 2001; Schaufeli & Enzmann, 1998; Schmidt, Neubach, & Heuer, 2007; Taris, 2006). Several studies have shown that burnout patients perform poorer on cognitive tasks than healthy controls (Sandström, Rhodin, Lundberg, Olsson, & Nyberg, 2005; Van Dam, Kei- jsers, Eling, & Becker, 2011; Van der Linden, Keijsers, Eling, & Van Schaijk, 2005). Many authors regard a reduction in mo- tivation to expend effort as the underlying mechanism for de- creased performance in burnout (Boksem & Tops, 2008; Schaufeli & Taris, 2005; Van Dam et al., 2011). An important question is whether this decreased motivation can be reversed by a motivational intervention. Some authors suggest that mo- tivational interventions may increase performance to normal levels (Halbesleben & Bowler, 2007; Rubino, Luksyte, Jansen Perry, & Volpone, 2009). Other authors, however, suggest that reduced motivation cannot readily be reversed by motivational interventions, because burnout patients suffer from biochemical changes due to prolonged periods of stress that affect perform- ance over longer periods (months, years) of time (Boksem & Tops, 2008; Frankenhaeuser, 1986; Mommersteeg, Keijsers, Heijnen, Verbraak, & Van Doornen, 2006; Sandström et al., 2005; Van der Linden et al., 2005). Boksem and Tops (2008) argue that physiological changes in the dopaminergic/motivational system, (due to systematic neglect of signs of fatigue for pro- longed periods of time), may be fundamental to long-term fa- tigue syndromes such as burnout. This theory is supported by a study by Van Dam et al. (2011): in which they failed to moti- vate burnout patients by providing fake positive feedback about their performance and by announcing a financial reward for the best performing participants. The findings of Van Dam et al. (2011), however, fail to ex- plain why burnout patients could not be motivated to increase their performance. One possibility is that performance was already as high as possible. Another possibility is that positive feedback and financial rewards did not successfully counteract the patient’s belief that their performance cannot be improved. Many authors (Afari & Buchwald, 2003; Knoop, Prins, Moss- Morris, & Bleijenberg, 2010) argue that cognitions play a major role in the perpetuation of symptoms in fatigue-related syn- dromes. Many individuals suffering from long-term fatigue believe that they have no control over their fatigue symptoms (Findley, Kerns, Weinberg, & Rosenberg, 1998; Knoop et al., 2010) and may perceive a good performance as unattainable, and therefore do not try to improve their performance despite an announced financial reward. It is theoretically and clinically important to find out whether reduced performance of burnout patients can be improved by the proper means. Therefore, we decided to examine the possibility of motivating patients im- plicitly using subliminal priming (Bargh, 2005; Dijksterhuis, Aarts, & Smith, 2005), thus bypassing cognitions about fatigue and performance. Several studies (Aarts, Custers, & Veldkamp, 2008; Chartrand & Bargh, 2002) have shown that motivation can be primed and that individuals primed with achieve- ment-related stimuli perform at a higher level on subsequent tasks compared to non-primed individuals. A procedure for successfully priming subsequent behaviour is the “scrambled sentence task” developed by Srull and Wyer (1979; for a review, *Corresponding author.  A. VAN DAM ET AL. see Bargh & Chartrand, 2000). The task is presented as a verbal ability task and is based upon sets of four words in random order. Participants are asked to construe grammatically correct sentences using three of the four words. For each set, only a single grammatically correct solution is possible. Without in- forming the participants, a proportion of these correct sentences refer to a specific behaviour, mood, or attitude which (un- knowingly to the participant) becomes activated or “primed”. In our study, we used sentences that primed for success, for in- stance: “John is winning” or for failure, for instance “John gives up”. We hypothesized that, if we primed healthy controls with ei- ther failure or success, and if we subsequently presented them with a complex cognitive task, those primed with success would outperform those primed with failure. With regard to burnout patients, we also expected that those, primed with suc- cess, would perform better than those primed with failure if cognitions about the fatigue-performance relationship played a role in reduced cognitive performance. Methods Participants Burnout patients (N = 63) were recruited from institutions for mental health where they were being treated for their symptoms. The diagnosis of burnout was established by the mental health institutions using the following criteria. Patients had to meet: 1) the validated cut-off points (Brenninkmeijer & van Yperen, 2003) for severe burnout on the Dutch version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory General Survey (see Measurements section for a description of the instruments): exhaustion ≥ 2.20 and either cynicism ≥ 2.00 or personal accomplishment ≤ 3.67; 2) the cut-off point for prolonged fatigue (Bültman et al., 2000) on the checklist individual strength (≥76); 3) the criteria for the proposed psychiatric equivalents of clinical burnout, namely the ICD-10 (World Health Organisation, 1994) criteria for work related neurasthenia (Schaufeli, Bakker, Hoogduin, Schaap, & Kladler, 2001; Schaufeli & Enzmann, 1998); and 4) the DSM- IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) criteria for un- specified somatoform disorder with prolonged fatigue as the main symptom (Hoogduin, Schaap, & Methorst, 2001). Both diagnoses were established by using the Dutch adaptation (Overbeek, Schruers, & Griez, 1999) of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., 1998) and a semi- structured interview checking ICD-10 criteria for work-related neurasthenia. Of the 61 patients meeting these criteria, 12 pa- tients also met the criteria of simple phobia as a secondary di- agnosis. They were equally divided over the prime-conditions. Patients diagnosed with burnout were sent a brochure about the research project and were offered additional information by telephone, whenever they wanted to. When patients decided to participate, they signed an informed consent form and returned it to the experimenter. Healthy controls (N = 40) were volunteers and did not meet the criteria for any of the DSM-IV disorders or currently re- ceive psychotherapeutic or psychopharmacologic treatment. They were employees (secretaries, cooks, cleaners and nurses) of a mental health institute or members of a sport club. Both groups were equally divided over the prime conditions. The healthy controls received 5 euros for participation and the burnout patients received a book on occupational stress. Measurements Severity of burnout symptoms was assessed with the Dutch adaptation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory General Survey (Maslach, Jackson, & Leiter, 1996), referred to as the Utrecht BurnOut Scale-A (UBOS-A; Schaufeli & Dierendonck, 2000). The UBOS-A comprises the following scales: emotional ex- haustion, depersonalization, and perceived job competence with high scores on emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and low scores on perceived job competence indicating burnout. Reliability and validity of the UBOS are good, Cronbach’s alpha’s are usually well above .70 (Schaufeli et al., 2001). General fatigue was assessed with the Dutch adaptation (Vercoulen, Alberts, & Bleijenberg, 1999) of the Checklist Individual Strength (CIS; Vercoulen et al., 1994). Its 20 items assess subjective feelings of fatigue and physical fitness, activ- ity level, motivation, and concentration during the previous 14 days. Reliability and validity of the CIS are good, Cronbach’s alpha for the CIS is .90 (Vercoulen et al., 1994). Participants were asked to rate their mood by placing a mark on a Visual Analogue Scale of 10 cm, with on the lefts side the word “sad” and on the right side the word “cheerful”. The dis- tance between the left endpoint and the mark was used as a measure of mood. Subjective assessment of acute fatigue was measured with the mental-fatigue scale (mf) of the short version of the Rating Scale Mental Effort (RSME; Zijlstra, 1993), which specifically measures how fatigued a participant is feeling as a result of performing the task at hand. The level of fatigue is indicated on a continuous line with 0 signifying “not fatigued at all” and 150 denoting “extremely fatigued”. The Rating Scale Expectancy of Performance (RSEP) was specifically developed for this study to assess the participants’ expectations about their performance level for the Scrambled Sentence Task (SST) and the cognitive switch task (see Task section below). Participants were asked to place a mark on a line of 10 cm, with on the lefts side “poor” and on the right side “good”. The distance between the left endpoint and the mark was used as a measure of performance expectancy. The Subjective Effort Scale (SES) was specifically devel- oped for this study to measure to what extent participants had tried to perform well at the SST and the switch task (see Task section below). Participants were asked to rate on a five-point Likert scale to what extent they had tried to perform well at the SST and the switch task (see Task section below). Tasks The Scrambled Sentence Task (SST) is an adaptation of the SST developed by Srull and Wyer (1979). The task was pre- sented to participants as a verbal ability task and comprised 25 lines of 4 words placed in random order (for example: “John, winning, chair, is”). Participants were asked to construe gram- matically correct sentences of three words out of 4 words. Only one grammatically correct solution was possible. For 16 lines the correct solution was related to either success (for example: “John is winning”) or failure (for example: “John gives up”), the other nine lines comprised neutral words only to disguise the purpose of the task. Because mental fatigue seems to affect performance on com- plex tasks more than on simple tasks (Holding, 1983; Matthews, Davies, Westerman, & Stammers, 2000), we presented partici- pants with a complex task. The task, based on the switch task of Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 584  A. VAN DAM ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 585 Rogers and Monsell (1995), involves the use of higher control processes necessary for the planning and preparation of future actions. This switch task paradigm has been used frequently in studies on cognitive performance in healthy controls as well as in burnout patients (Matthews et al., 2000; Oosterholt, Van der Linden, Maes, Verbraak, & Kompier, 2011; Van Dam et al., 2011). Using the current version of the switch-task, 300 letters ap- peared successively in a clockwise fashion in each corner of a screen, starting in the upper left square. The letters were ran- domly chosen from the set: A, B, E, G, O, and S. The colour of the letters was randomly chosen from the set green or red. If a green letter appeared in the upper half of the screen, participants had to push the left button on a button box as fast as possible; in case of a red letter, they had to push the right button. If the letter was in the lower half of the screen, participants had to push the left button as fast as possible when the letter was a vowel, and the right button if it was a consonant. Thus, subjects were asked to switch tasks every second trial. The task started with an Inter-Stimulus-Interval (ISI) of 1500 ms, which is ample time for healthy controls to respond ade- quately without much effort (Lorist et al., 2000; Nieuwenhuis & Monsell, 2002; Rogers & Monsell, 1995). Four correct re- sponses in succession resulted in a reduction of the ISI by 50 ms, leading to an acceleration of the letters appearing on the screen. When participants made two or more errors in a set of four responses, the ISI was increased by 20 ms. Accordingly, the speed of the task was adapted to the level of performance. The speed (ISI) of the letters appearing on the screen at the end of the task (Mean of last 30 ISIs) was used as a measure for performance. In order to check whether the prime was effective during the cognitive task, we used an adaptation of a task employed by Kruglanski and colleagues (Richter & Kruglanski, 1998) to measure the implicit activation of success and failure. After performing the cognitive task, participants were presented with an employment advertisement (Employment Advertisement Task; EAT) describing a commercial job. Subsequently, they were presented with a photograph of a young man and were asked to rate the likelihood that the man will be admitted to the job by placing a mark on a Visual Analogue Scale of 10 cm, with printed on the lefts side “very unlikely” and on the right side “highly likely”. We hypothesized that if the prime was still active, healthy controls primed with success would rate the chances of success as higher than healthy controls primed with failure. Procedures Prior to participation, diagnoses were established as de- scribed in the participant section. Participants were tested in a quiet room during the day. They completed a short biographical questionnaire and rated their scores on the mood rating scale and the RSME-mf, which took about 2 minutes. Subsequently, the experimenter asked them to complete the SST presented to them as a verbal ability task. This took approximately 7 minutes to complete. Participants were randomly assigned to the success or failure condition in advance. Next they received instructions for the switch task and completed the RSEP (the mood rating scale) and the RSME-mf for the second time, which took less than a minute. Subsequently they performed the switch task which took about 10 minutes. Afterwards, participants again rated the mood rating scale and the RSME-mf. Participants were presented with the EAT. After rating the job candidate’s chances for success, they were asked to rate the extent that they had tried to perform well on the SST and the switch task and they were asked to describe what they thought the purpose of the experiment was in order to check if they discovered the particular content of the SST. Next, participants completed the CIS and the UBOS. We asked them to complete these questionnaires at the end of the experiment so that they could not serve as a prime for the tasks. Finally participants were debriefed about the purpose of the tasks and procedures. It is well-known that priming-effects are short lived (Bargh, 2005) and we did not expect effects after the experiment. But in case of potential negative effects, participants were given the phone number and e-mail address of the re- searcher if they had any questions about the experiment. None of the participants contacted us after the experiment. Approval for the study was obtained from the Ethical Committee (ECG) of the Faculty of Social Sciences of Radboud University Ni- jmegen in the Netherlands. Results Characteristics of the burnout patients and healthy controls in the different conditions are presented in Table 1. With regard Table 1. Characteristics of the burnout patients and healthy controls primed with failure or with success. Burnout patients Healthy controls Success prime (N = 31) Failure prime (N = 30) Success prime (N = 35) Failure prime (N = 32) Gender: Men 19 (61.3%) 18 (60.0%) 19 (54.35%) 12 (37.5%) Age (Mean SD)** 44.9 (8.6) 44.4 (8.7) 36.4 (11.0) 36.0 (12.2) Educational level Low 3 (9.7%) 3 (10%) 5 (14.3%) 1 (3.1%) Middle 9 (29%) 12 (40%) 9 (25.7%) 12 (37.5%) High 19 (61.2%) 15 (50%) 21 (60%) 19 (59.4%) Symptom Measures (Mean SD) Utrecht Burn Out Scale Emotional Exhaustion* 3.3 (1.5) 3.6 (1.3) 1.9 (1.3) 1.8 (1.3) Depersonalization** 2.7 (1.3) 2.7 (1.3) 1.5 (1.2) 1.3 (1.0) Perceived Job Competence* 3.9 (1.0) 3.9 (.9) 4.3 (.8) 4.3 (.6) Checklist Individual Strength** 82.0 (22.4) 89.3 (25.2) 63.7 (17.9) 67.6 (12.9) *Significant for group (burnout patient/healthy control) at p < .05; **Significant for group (burnout patient/healthy control) at p < .001  A. VAN DAM ET AL. to gender and education, there were no significant differences between burnout patients and healthy controls or between the conditions, but there was a significant difference in age be- tween burnout patients healthy controls, F(1, 124) = 21.5, p < .001. Inspection of the means showed that burnout patients were older (M = 44.6, SD = 8.6) than healthy controls (M = 36.2, SD = 11.5). We correlated Age with Performance; the correlation was not significant in HCs (p > .1) but was signifi- cant in BPs (r = .30, p < .05). In order to correct for potential age effects, Age was used as a covariate in subsequent analyses. With regard to symptoms, we conducted a two-way be- tween-groups multivariate ANCOVA with emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, perceived job competence (UBOS-A), and general level of fatigue (CIS) as dependent variables. Group [BPs, HCs] and Condition [Success, Failure] were the inde- pendent variables. There was a significant effect for Group, F(4, 102) = 13.7, p < .001 and the results for the separate dependent variables also reached statistical significance: exhaustion, F(1, 105) = 31.1, p < .001, depersonalization F(1, 105) = 23.2, p < .001, perceived job competence, F(1, 105) = 6.6, p < .05, general level of fatigue, F(1, 105) = 24.0, p < .001. Burnout patients reported significantly more burnout symptoms and fatigue than healthy controls. There were no differences be- tween the conditions and there were no interaction effects be- tween Group and Condition. All participants performed faultlessly on the SST. When asked at the end of the experiment what the participants thought that the purpose of the experiment was, only one participant (healthy control primed with success) correctly noted the pur- pose of the experiment. The scores on the Mood Rating Scale, RSME-mf, RSEP, SES and EAT and level of performance on the switch task for the two groups and the two conditions are presented in Table 2. The course of the ISI for burnout patients and healthy controls primed with success or failure is presented in Figure 1. With regard to performance, we conducted a two-way between-groups univariate ANCOVA with Group [BPs, HCs] and Condition [Success, Failure] as the independent variables, ISI as dependent variable and Age as covariate. There was a significant effect for Group, F(1, 123) = 4.1, Table 2. Scores on rating scales during the experiment and performance of the burnout patients and healthy controls primed with failure or with success. Burnout patients Healthy controls Success prime (N = 31)Failure prime (N = 30)Success prime (N = 35) Failure prime (N = 32) Mood Rating Scale T1 62.8 (19.2) 62.7 (17.4) 67.7 (19.6) 71.0 (15.0) Mood Rating Scale T2 62.4 (17.9) 62.7 (17.8) 63.8 (17.6) 70.1 (14.8) Mood Rating Scale T3 56.9 (23.5) 57.2 (20.1) 59.6 (20.2) 62.7 (15.9) RSME-mf T1** 54.7 (32.3) 55.6 (28.4) 39.3 (29.0) 33.9 (26.1) RSME-mf T2** 54.9 (34.7) 56.4 (30.2) 41.7 (28.8) 32.4 (23.4) RSME-mf T3** 59.2 (37.9) 65.9 (33.7) 45.4 (27.6) 40.2 (25.0) Performance (Mean ISI (ms) on last 30 trials)*# 1983 (1011) 1653 (951) 1090 (267) 1612 (836) Rating Scale Expectancy of Performance (RSEP) 54.0 (19.4) 55.8 (20.1) 48.9 (14.3) 54.9 (15.9) Employment Advertisement Task (EAT)# 50.9 (24.8) 61.0 (18.9) 70.8 (14.0) 59.0 (19.2) Subjective Effort Scale (SES) on SST 4.2 (1.1) 4.4 (.9) 4.3 (.7) 4.3 (.9) Subjectibe Effort Scale (SES) on Switch task 4.2 (.9) 4.3 (.8) 4.1 (.6) 4.1 (.8) *Significant for Group (burnout patient/healthy controls) at p < .05. **Significant for Group (burnout patient/healthy control) at p < .001. #Significant interaction effect for Group (burnout patient/healthy control) and Condition (Success, Failure) at p < .05. Figure 1. ISI (Inter-Stimulus-Interval) over 300 trials for the burnout patients and healthy controls primed with success or with failure. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 586  A. VAN DAM ET AL. p < .05, 2 = .03. The performance of healthy controls was bet- ter (M = 1339, SD = 659) than the performance of burnout patients (M = 1821, SD = 988). We also found a significant Group x Condition interaction, F(1, 123) = 9.3, p < .01, 2 = .07, which indicates that burnout patients and healthy controls reacted differently to the prime-condition. There was also a significant effect of Age, F(1, 123) = 7.8, p < .01, 2 = .06. When age was not used as a covariate, we found the same re- sults with somewhat larger effect sizes (Group, F(1, 123) = 10.6, p < .001, 2 = .08, Group × Condition interaction, F(1, 123) = 8.9, p < .01, 2 = .07). Separate ANCOVAs for burnout patients and healthy controls with Condition [Success, Failure] as the independent variable, and ISI as dependent variable revealed that healthy controls primed with success performed better than healthy controls primed with failure, F(1, 64) = 12.8, p < .001, 2 = .17 on the cognitive switch task and that there was no dif- ference between the burnout patients in the two conditions. Separate ANCOVAs for the success condition and the failure condition with Group [BPs, HCs] as the independent variable and ISI as dependent variable revealed that success primes resulted in a better performance in healthy controls in compari- son to burnout patients, F(1, 63) = 14.7, p < .001, 2 = .19. There was no difference between the groups in the failure con- dition. We conducted two-way repeated measures ANCOVAs with Group [BPs, HCs] and Condition [Success, Failure] as the be- tween subjects variable and Time (T1, T2, T3) as within vari- able for the mood rating scales and the RSME-mf separately. No significant effects were found for the various scores on the mood rating scale. For the RSME-mf there was a significant effect for Group, F(1, 123) = 20.8, p < .001, 2 = .14. As ex- pected, burnout patients reported more mental fatigue than healthy controls. With regard to RSEP, SES and EAT, we conducted two-way between-groups univariate ANCOVAs, with RSEP, TPWS and EAT scores as dependent variables. Group [BPs, HCs] and Condition [Success, Failure] were the independent variables. With regard to the EAT there was a significant effect for Group, F(1, 123) = 5.7, p < .05, 2 = .04, and a significant Group x Condition effect, F(1, 123) = 9.9, p < .01, 2 = .08. Inspections of the means showed that healthy controls (M = 65.2, SD = 17.6) estimated the chances of success larger for the job candidate than the burnout patients (M = 55.9, SD = 22.5). Separate ANCOVAs for burnout patients and healthy controls with Condition [Success, Failure] as the independent variable, and EAT as dependent variable revealed that healthy controls primed with success estimated the chances of success larger for the job candidate than the than healthy controls primed with failure, F(1, 64) = 8.1, p < .01, 2 = .11. There was a trend be- tween the burnout patients in the two conditions, F(1, 64) = 3.1, p = .08, 2 = .05. We found no significant effects for RSEP and SES. Discussion Motivational interventions do not appear to be effective in improving performance in burnout patients (van Dam et al., 2011). It is not clear, however, whether the performance in burnout patients already tends to be as high as possible or whether burnout patients do not believe that their performance can be improved despite positive feedback and financial re- wards. In order to bypass cognitions about fatigue, we investi- gated the possibility that motivation can be enhanced in an implicit way, using subliminal priming. We primed burnout patients and healthy control with success or failure. After priming, the participants were presented with a complex cogni- tive task that has been used in previous studies to measure cog- nitive performance in fatigued individuals (Lorist et al., 2000; Van Dam et al., 2011). As expected, burnout patients reported more burnout symp- toms and fatigue than healthy controls. With regard to task performance, burnout patients reported that they tried to per- form well at the cognitive task just like the healthy controls (SES), but they showed poorer performance than the healthy controls, and experienced more fatigue during the task. These findings are in line with studies that show that cognitive per- formance in burnout is reduced and that mental effort leads to enhanced fatigue increase (Sandström et al., 2005; Van Dam et al., 2011; Van der Linden et al., 2005). Healthy controls primed with success outperformed healthy controls primed with failure on the cognitive task. Apparently the prime was effective in increasing motivation in healthy controls. EAT findings suggest that prime effects were still present in healthy controls at the end of the experiment. However, burnout patients primed with success did not perform better than burnout patients primed with failure or healthy controls primed with failure. Burnout patients were not positively af- fected by the success primes to perform well. This finding is in line with the theory of Boksem and Tops (2008) that burnout patients are not responsive to motivational interventions any- more. However, an alternative explanation is possible as well. The primes we used in the SST may have also invited the partici- pants to compare themselves with others. Brenninckmeijer et al. (2000) found that comparison with successful others leads to a negative affect in burnout. The effect of the primes might have been different if we had used words like “I” or “You” in com- bination with success or failure-related words. We found no differences in reported mood between groups and conditions however, which suggests that the formulation of the SST did not affect our results. The mean performance of burnout patients primed with suc- cess was inferior (although not significantly), compared to that of burnout patients primed with failure. The large variance suggests that success primes may even lead to reduced perform- ance in some of the burnout patients. The finding that primes can elicit behaviour in the opposite direction than would have been expected has been observed before and seems to occur when primed behaviour is by participants perceived as out of reach (Dijksterhuis et al., 1998; Hart & Albarracin, 2009). This may also have been the case in our study because several stud- ies suggest that burnout patients may react differently to suc- cess than healthy controls because they perceive success as unattainable (Brenninckmeijer, Van Yperen, & Buunk, 2001; Brenninckmeijer, 2002). Although burnout patients primed with success did not im- prove performance, they reported similar levels of expected success on the task (RSEP) and similar levels of subjective effort spent at the task (SES) as the control participants. Ap- parently the prime did not influence the subjective expectations for successful performance, nor the perceived amounts of effort spent on the task or mood during the task. This finding is in line with many studies on priming that show that priming influences behaviour, but does not necessarily lead to a change in feelings Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 587  A. VAN DAM ET AL. or cognitions (Bargh, 2005), although some studies demon- strated that achievement priming can trigger higher expecta- tions of task outcomes (Custers, Aarts, Oikawa, & Elliot, 2009). Nevertheless, we conclude that differences in performance between the two groups cannot be explained by differences in success expectation and perceived effort. A limitation of our study is that we did not use a neutral priming condition. Therefore, we cannot determine to what extent priming effects can be attributed to priming for success, failure or both. Several studies have determined that success- related priming can increase motivation for task performance (Ciani & Sheldon, 2010; Custers et al., 2009; Custers & Aarts, 2005; Lowery, Eisenberger, Hardin, & Sinclair, 2007), and that failure-related priming can decrease motivation for task per- formance (Bry, Follenfant, & Meyer, 2008; Ciani & Sheldon, 2010; Legal & Meyer, 2007). A comparison with the perform- ance (ISI) of unprimed burnout patients (M = 1716, SD = 888) and healthy controls (M = 1089, SD = 351) from an earlier study (Van Dam et al., 2011) in which the same cognitive task was used, suggests that the strongest prime effect in healthy controls in this study was the failure prime and the strongest effect in burnout patients, although in the opposite direction, was the success prime. As many studies (Johnson, Benas, & Gibb, 2011; Stieger & Burger, 2010) have demonstrated, psy- chological disorders are associated with specific implicit cogni- tions. An explanation for this finding may be that burnout pa- tients exhibit implicit associations with failure as suggested by Brenninckmeijer et al. (2000) and healthy controls exhibit im- plicit associations with success. This is in line with many stud- ies that show a positive self-judgment bias in healthy individu- als (Dunn, Stefanovitch, Buchan, Lawrence, & Dalgleish, 2009; Schmidt & Mast, 2010). It is possible that the implicit cogni- tions that are already active cannot be activated to a much lar- ger extent in contrast to cognitions that are not activated yet. A second limitation that cannot be ruled out is that the score on the EAT is also influenced by the level of performance on the switch task. Success on the switch task may have served as a prime for the EAT. We assume that this effect is small, how- ever, because participants did not receive feedback about their performance on the switch task and therefore unable to deter- mine how well they performed. A third limitation is that participants performed the switch task only once. Therefore we cannot establish differential, within-subjects-effects of the priming procedure, we can only determine whether there was a difference between the experi- mental groups. A fourth limitation may be that the burnout patients in our study were somewhat older than the healthy controls. Although statistically significant, the difference was relatively small. Moreover, the burnout patients performed less well than healthy controls, and this effect is still significant if age is taken into account. We therefore assume that the age difference be- tween the groups did not substantially affect our results. A fifth limitation may be that healthy controls and burnout patients received a different kind of reward for participating in the experiment. Because the reward was related to participation and not to performance, we assume that this difference did not affect our results. In conclusion, this study showed that success primes did not increase performance in burnout, which supports theories that state that burnout patients are not responsive to motivational interventions. Moreover this study indicates that the non-re- sponsiveness of burnout patients to motivational interventions is not a mere consequence of cognitions about fatigue and per- formance but seems to stem from a more structural condition. REFERENCES Aarts, H., Custers, R., & Veltkamp, M. (2008). Goal priming and the affective motivational route to nonconscious goal pursuit. Social Cognition, 26, 497-519. doi:10.1521/soco.2008.26.5.555 Afari, N., & Buchwald, D. (2003). Chronic fatigue syndrome: A review. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 221-236. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.221 American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. Bargh, J. A. (2005). Bypassing the will: Toward demystifying the non- conscious control of social behaviour. In R. R. Hassin, J. S. Uleman, & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The new unconscious (pp. 37-60). Oxford: University Press. Bargh, J. A., & Chartrand, T. L. (2000). A practical guide to priming and automaticity research. In H. Reis, & C. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social psychology (pp. 253-285). New York: Cambridge University Press. Boksem, M. A. S., & Tops, M. (2008). Mental fatigue: Costs and bene- fits. Brain Research Reviews, 59, 125-139. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.07.001 Brenninkmeijer, V. (2002). A drug called comparison: The pains and gains of social comparison among individuals suffering from burnout. Dissertation. Almere: Casparie. Brenninkmeijer, V., Van Yperen, N. W., & Buunk, B. P. (2001). I am not a better teacher, but others are doing worse: Burnout and percep- tions of superiority among teachers. Social Psychology of Education, 4, 259-274. doi:10.1023/A:1011376503306 Brenninkmeijer, V., & Van Yperen, N. (2003). How to conduct re- search on burnout: Advantages and disadvantages of a unidimensional approach to burnout. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60, 16-21. doi:10.1136/oem.60.suppl_1.i16 Bry, C., Follenfant, A., & Meyer, T. (2008). Blonde like me: When self-construals moderate stereotype priming effects on intellectual performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 751- 757. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2007.06.005 Bültmann, U., De Vries, M., Beurskens, A. J. H. M., Bleijenberg, G., Vercoulen, J. H. M. M., & Kant, I. J. (2000). Measurement of pro- longed fatigue in the working population: Determination of a cut-off point for the Checklist Individual Strength. Journal of Occuptional Health Psychology, 5, 411-416. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.5.4.411 Chartrand, T. L, & Bargh, J. A. (2002). Nonconscious motivations: Their activation, operation, and consequences. In A. Tesser, D. A. Stapel, & J. V. Wood (Eds.), Self and motivation: Emerging psycho- logical perspectives (pp. 13-41). Washington, DC: American Psy- chological Association. doi:10.1037/10448-001 Ciani, K. D., & Sheldon, K. M. (2010) A versus F: The effects of im- plicit letter priming on cognitive performance. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 99-119. doi:10.1348/000709909X466479 Custers, R., & Aarts, H. (2005). Positive affect as implicit motivator: On the nonconscious operation of behavioral goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 129-142. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.89.2.129 Custers, R., Aarts, H., Oikawa, M., & Elliot, A. (2009). The noncon- scious road to perceptions of performance: Achievement priming augments outcome expectancies and experienced self-agency. Jour- nal of Experimental Social P s y c ho l o gy, 45, 1200-1208. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2009.07.013 Dijksterhuis, A., Aarts, H., & Smith, P. K. (2005). The power of the subliminal: Subliminal perception and possible applications. In R. Hassin, J. Uleman, & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The new unconscious (pp. 77-106). New York: Oxford University Press. Dijksterhuis, A., Spears, R., Postmes, T., Stapel, D. A., Koomen, W., Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 588  A. VAN DAM ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 589 van Knippenberg, A., & Scheepers, D. (1998). Seeing one thing and doing another: Contrast effects in automatic behavior. Journal of Personality and Social P s y chology, 75, 862-871. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.4.862 Dunn, B. D., Stefanovitch, I., Buchan, K., Lawrence, A. D, & Dalgleish, T. (2009) A reduction in positive self-judgment bias is uniquely re- lated to the anhedonic symptoms of depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47, 374-381. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2009.01.016 Findley, J. C., Kerns, R., Weinberg, L. D., & Rosenberg, R. (1998). Self-efficacy as a psychological moderator of chronic fatigue syn- drome. Journal of Behavio ral M ed ic in e, 21, 351-362. doi:10.1023/A:1018726713470 Frankenhaeuser, M. (1986). A psychobiological framework for research on human stress and coping. In M. H. Appeley, & R. Trumball (Eds.), Dynamics of stress (pp. 101-116). New York: Plenum Press. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-5122-1_6 Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Bowler, W. M. (2007). Emotional exhaustion and job performance: The mediating role of motivation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 93-106. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.93 Hart, W., & Albarracin, D. (2009). The effects of chronic achievement motivation and achievement primes on the activation of achievement and fun goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 1129-1141. doi:10.1037/a0017146 Holding, D. H. (1983). Fatigue. In G. R. J. Hockey (Ed.), Stress and fatigue in human performance (pp. 123-144). Chichester: John Wiley. Hoogduin, C. A. L., Schaap, C. P. D. R., & Methorst, G. J. (2001). Burnout: Klinisch beeld en diagnostiek [Burnout; clinical symptoms and diagnostics]. In C. A. L. Hoogduin, W. B. Schaufeli, C. P. D. R. Schaap, & A. B. Bakker (Eds.), Behandelingsstrategieën bij burnout (pp. 24-39). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum. Johnson, A. L., Benas, J. S., & Gibb, B. E. (2011). Depressive implicit associations and adults’ reports of childhood abuse. Cognition and Emotion, 25, 328-333. doi:10.1080/02699931003787270 Knoop, H., Prins, J. B., Moss-Morris, R., & Bleijenberg, G. (2010). The central role of cognitive processes in the perpetuation of chronic fa- tigue syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Researc h, 68, 489-494. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.01.022 Legal, J. B., & Meyer, T. (2008). When somebody else’s loss of control is contagious: Effects of a context priming on performance and emo- tions. Bulletin de Psycholog i e, 60, 195-210. Lorist, M. M., Klein, M., Nieuwenhuis, S., De Jong, R., Mulder, G., & Meijman, T. F. (2000). Mental fatigue and task control: planning and preparation. Psychophysiology, 37, 614-625. doi:10.1111/1469-8986.3750614 Lowery, B. S., Eisenberger, N. I., Hardin, C. D., & Sinclair, S. (2007). Long-term effects of subliminal priming on academic performance. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 29, 151-157. doi:10.1080/01973530701331718 Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1996). Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychological Press. Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397-422. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397 Matthews, G., Davies, D. R., Westerman, S. J., & Stammers, R. B. (2000). Human Performance: Cognition, stress and individual dif- ferences. Hove: Psychology Press. Mommersteeg, P. M. C., Keijsers, G. P. J., Heijnen, C. J., Verbraak, M. J. P. M., & Van Doornen, L. J. P. (2006). Cortisol deviations in peo- ple with burnout before and after psychotherapy: A pilot study. Health Psychology, 2, 243-248. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.25.2.243 Nieuwenhuis, S., & Monsell, S. (2002). Residual costs in task switch- ing: Testing the “failure to engage” hypothesis. Psychonomic Bulle- tin and Review, 9, 86-92. doi:10.3758/BF03196259 Overbeek, T., Schruers, K., & Griez, E. (1999). Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview. Maastricht: University of Maastricht. Oosterholt, B. G., Van der Linden, D., Maes, J. H. R., Verbraak, M. J. P. M., & Kompier, M. A. J. (2011). Burned out cognition—Cognitive functioning of burnout patients before and after a period with psy- chological treatment. Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment & Health, online first. Richter, L., & Kruglanski, A. W. (1998). Seizing on the latest: Motiva- tionally driven recency effects in impression formation. Journal of experimental social psychology, 34, 313-329. doi:10.1006/jesp.1998.1354 Rogers, R. D., & Monsell, S. (1995). Costs of a predictable switch between simple cognitive tasks. Journal of Experimental Psyc h o l og y , 124, 207-231. Rubino, C., Luksyte, A., Jansen Perry, S., & Volpone, S. D. (2009). How do stressors lead to burnout? The mediating role of motivation. Journal of Occupational Health P sy ch ol og y, 14, 289-304. doi:10.1037/a0015284 Sandström, A., Rhodin, I., Lundberg, M., Olssen, T., & Nyberg, L. (2005). Impaired cognitive performance in patients with chronic burnout syndrome. Biological Psychology, 69, 271-279. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.08.003 Schaufeli, W. B., & van Dierendonck, D., (2000). UBOS Utrechtse Burnout Schaal: Handleiding [Utrecht Burnout Scale: Manual]. Lisse: Swets Test Publishers. Schaufeli, W. B., & Enzmann, D. (1998). The burnout companion to study and practice: A critical analysis. London: Taylor & Francis. Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., Hoogduin, K., Schaap, C., & Kladler, A. (2001). On the clinical validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory and the Burnout Measure. Psychology and Health, 16, 565-582. doi:10.1080/08870440108405527 Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. (2005). The conceptualization and measure- ment of burnout: Common ground and worlds apart. Work & Stress, 19, 256-262. doi:10.1080/02678370500385913 Schmid, P. C., & Mast, M. S. (2010). Mood effects on emotion reco- gnition. Motivation and Emotion, 34, 288-292. doi:10.1007/s11031-010-9170-0 Schmidt, K. H., Neubach, B., & Heuer, H. (2007). Self-control demands, cognitive control deficits, and burnout. Work & Stress, 21, 142-154. doi:10.1080/02678370701431680 Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., Hergueta, T., Baker, R., & Dunbar, G. C. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The de- velopment and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric inter- view for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 5, 22- 33. Srull, T. K., & Wyer, R. S. (1979). The role of category accessibility in the interpretation of information about persons: Some determinants and implications. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1660-1672. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.37.10.1660 Stieger, S., & Burger, C. (2010). Implicit and explicit self-esteem in the context of internet addiction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13, 681-688. doi:10.1089/cyber.2009.0426 Taris, T. W. (2006). Is there a relationship between burnout and objec- tive performance: A critical review of 16 studies. Work & Stress, 20, 316-334. doi:10.1080/02678370601065893 Van Dam, A., Keijsers, G. P. J., Eling, P. A. T. M., & Becker, E. S. (2011). Testing whether reduced cognitive performance in burnout can be reversed by a motivational intervention. Work & Stress, 25, 257-271. doi:10.1080/02678373.2011.613648 Van der Linden, D., Keijsers, G. P. J., Eling, P., & Van Schaijk, R. (2005). Work stress and attentional difficulties: An initial study on burnout and cognitive failures. Work & Stress, 19, 23-36. doi:10.1080/02678370500065275 Vercoulen, J. H. M. M., Swanink, C. M. A., Fennis, J. F. M., Galama, J. M. D., Van der Meer, J. W. M., & Bleijenberg, G. (1994). Dimensional assessment of chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 38, 383-392. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(94)90099-X Vercoulen J. H. M. M., Alberts, M., & Bleijenberg, G. (1999). De Checklist Individual Strength (CIS). Gedragstherapie, 3 2, 131-136. World Health Organisation (1994). ICD-10. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. Geneva: World Health Organisation. Zijlstra, F. R. H. (1993). Efficiency in work behaviour: A design ap- proach for modern tools. Delft: University Press.

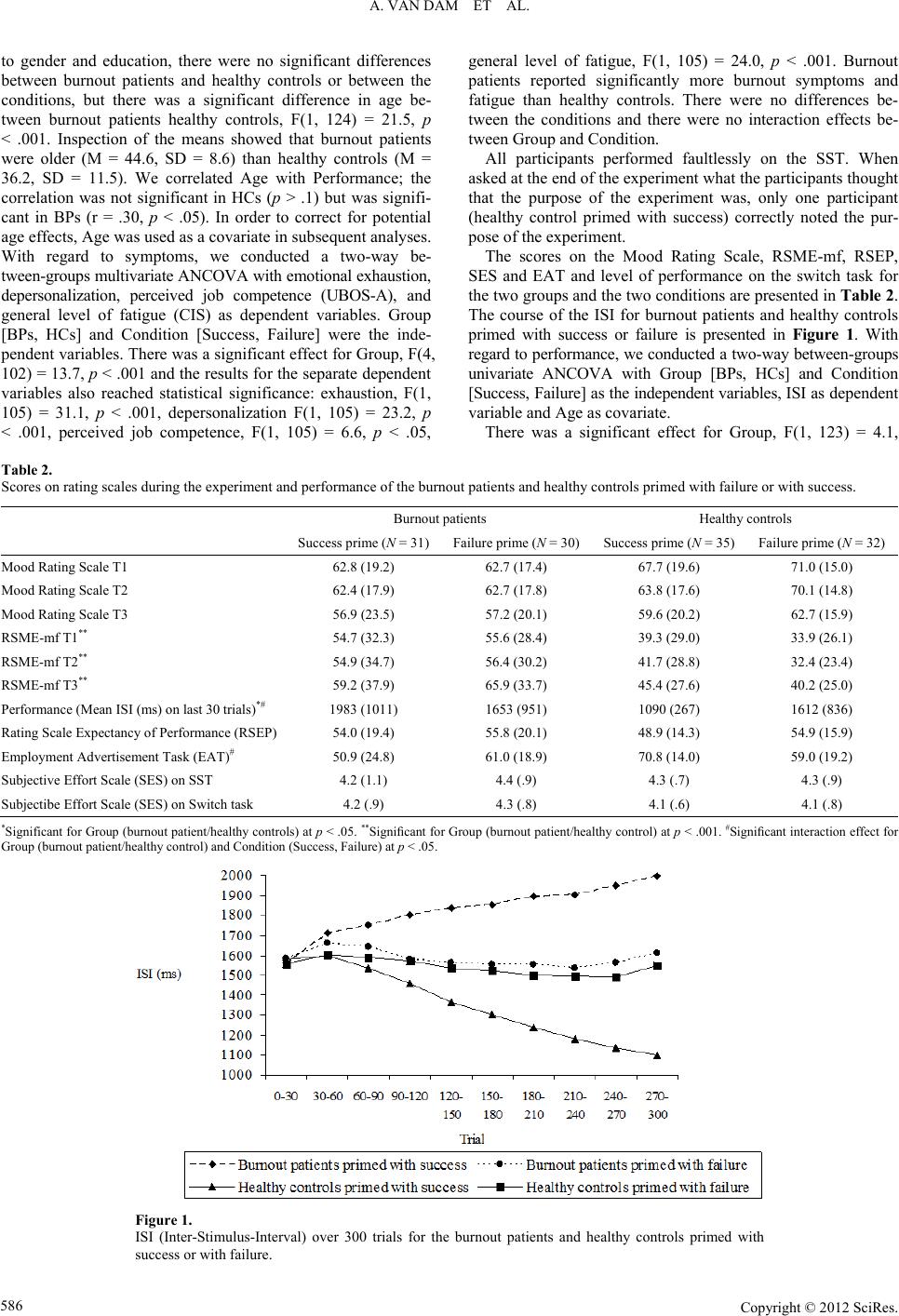

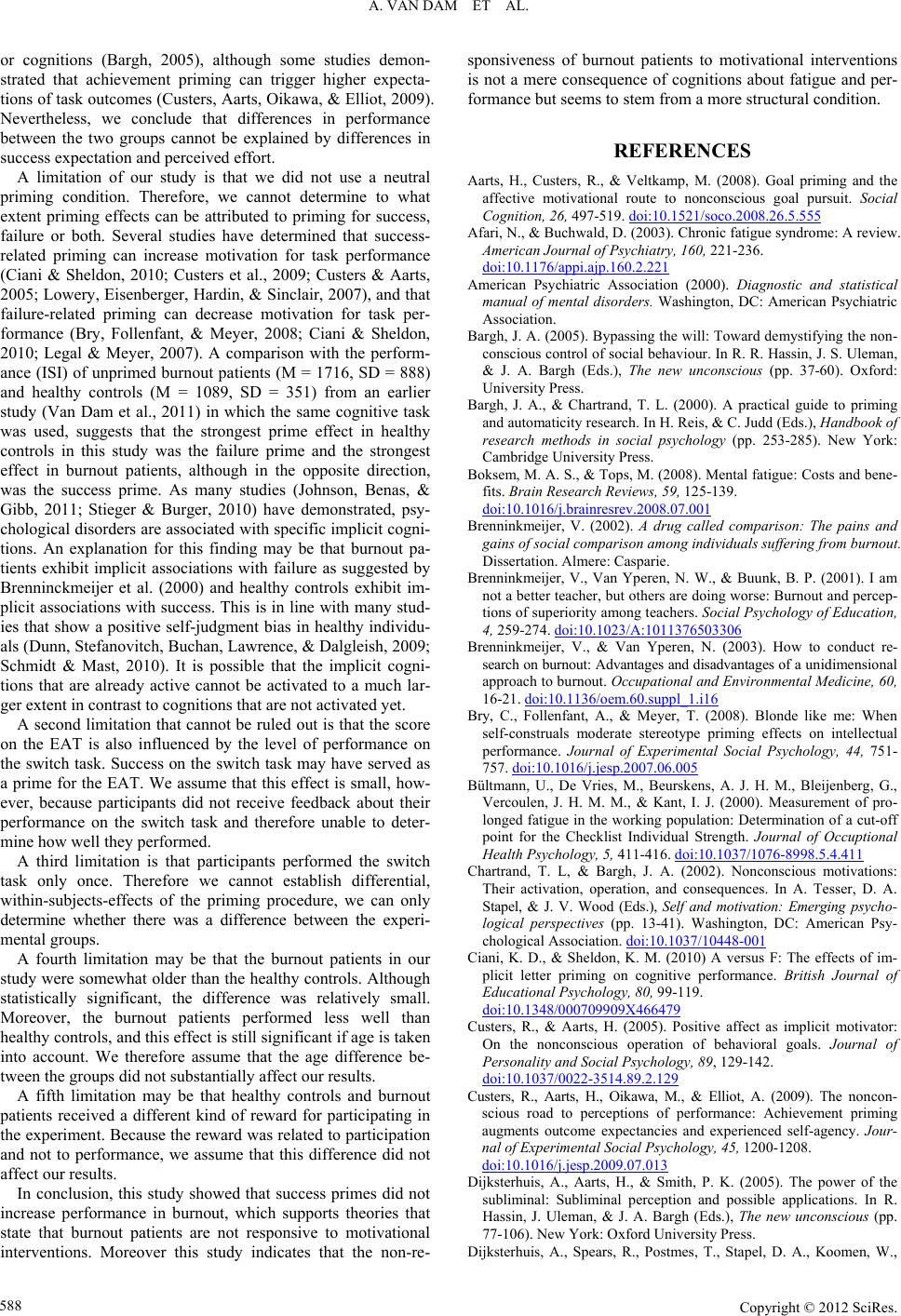

|