Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

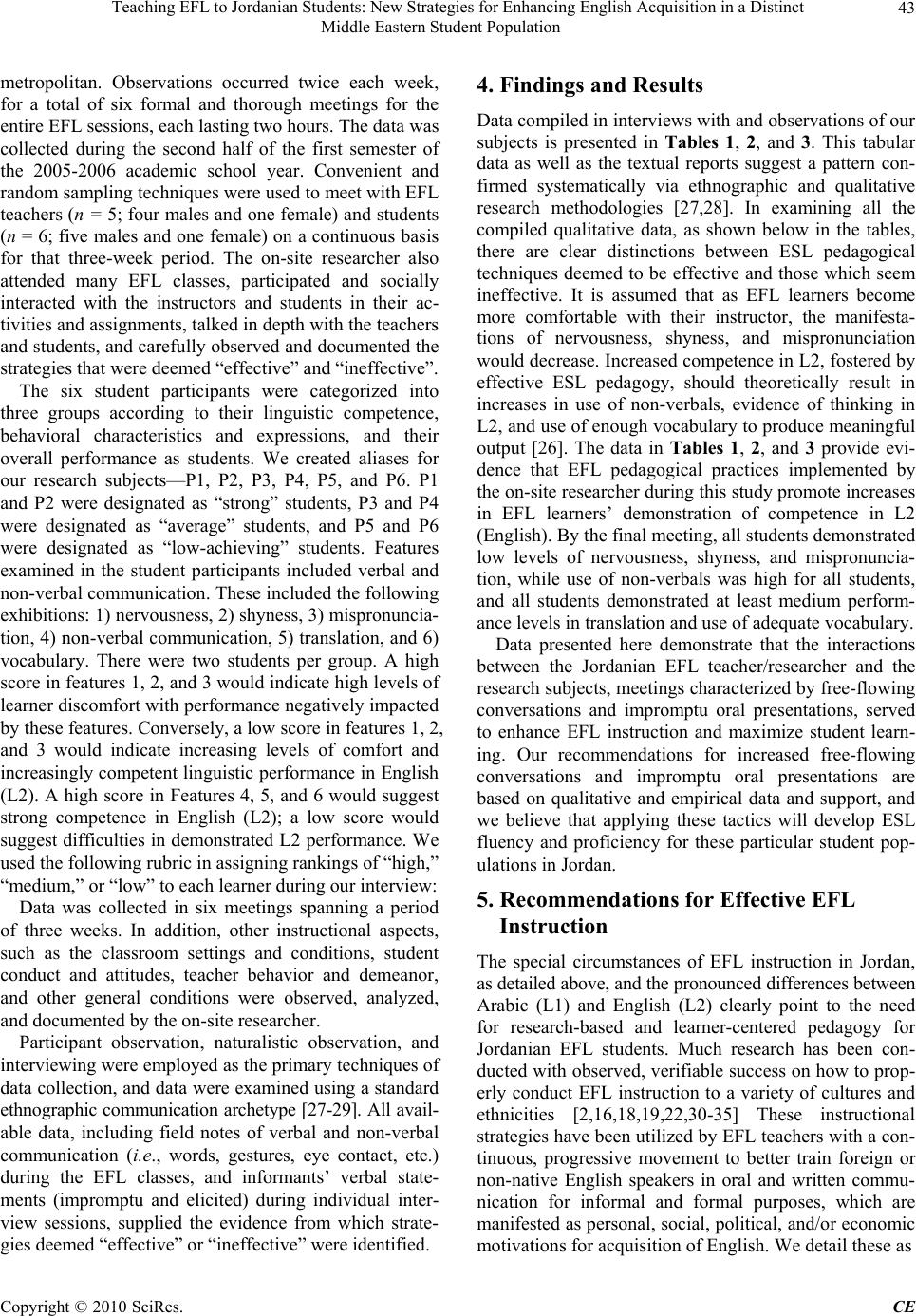

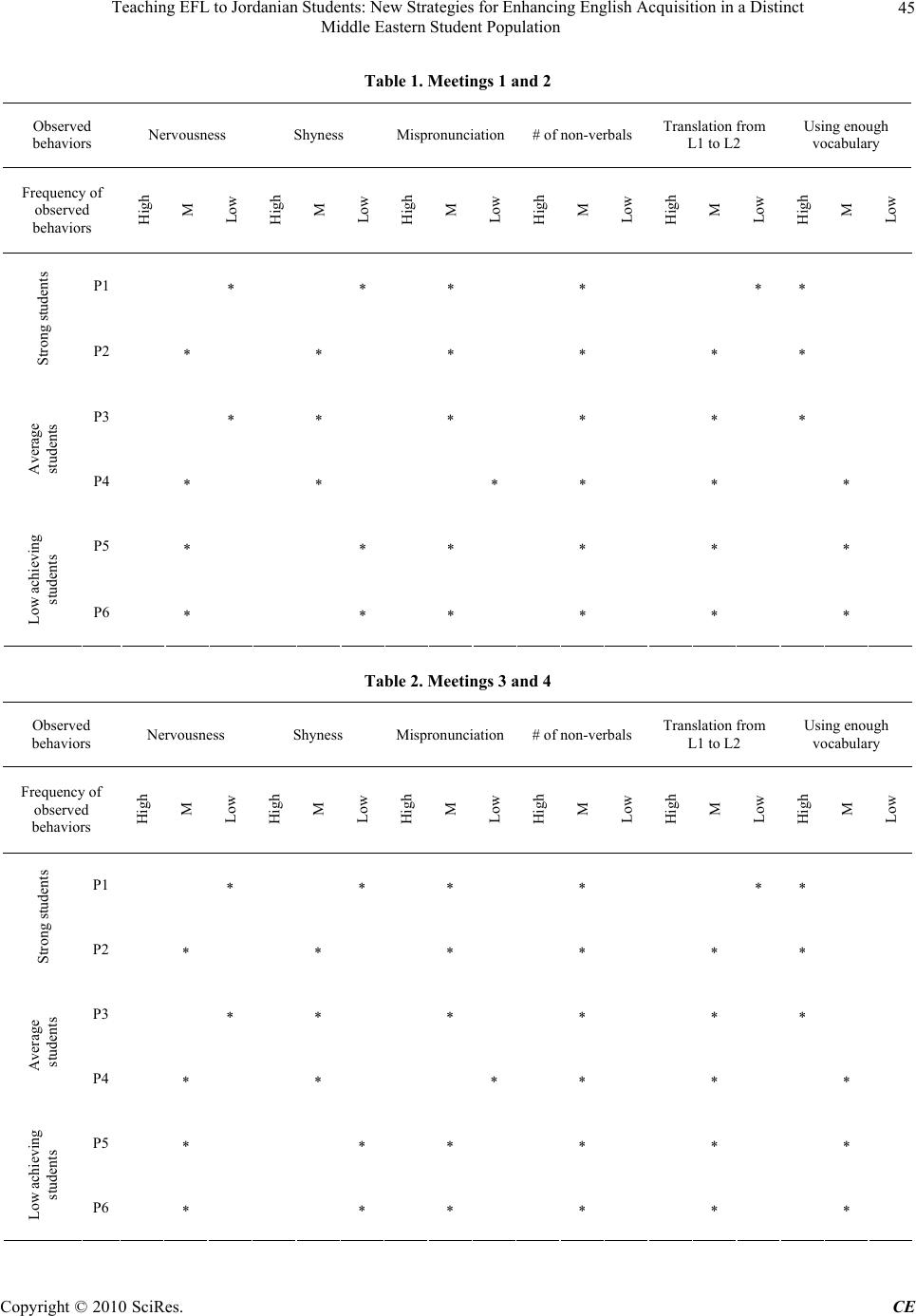

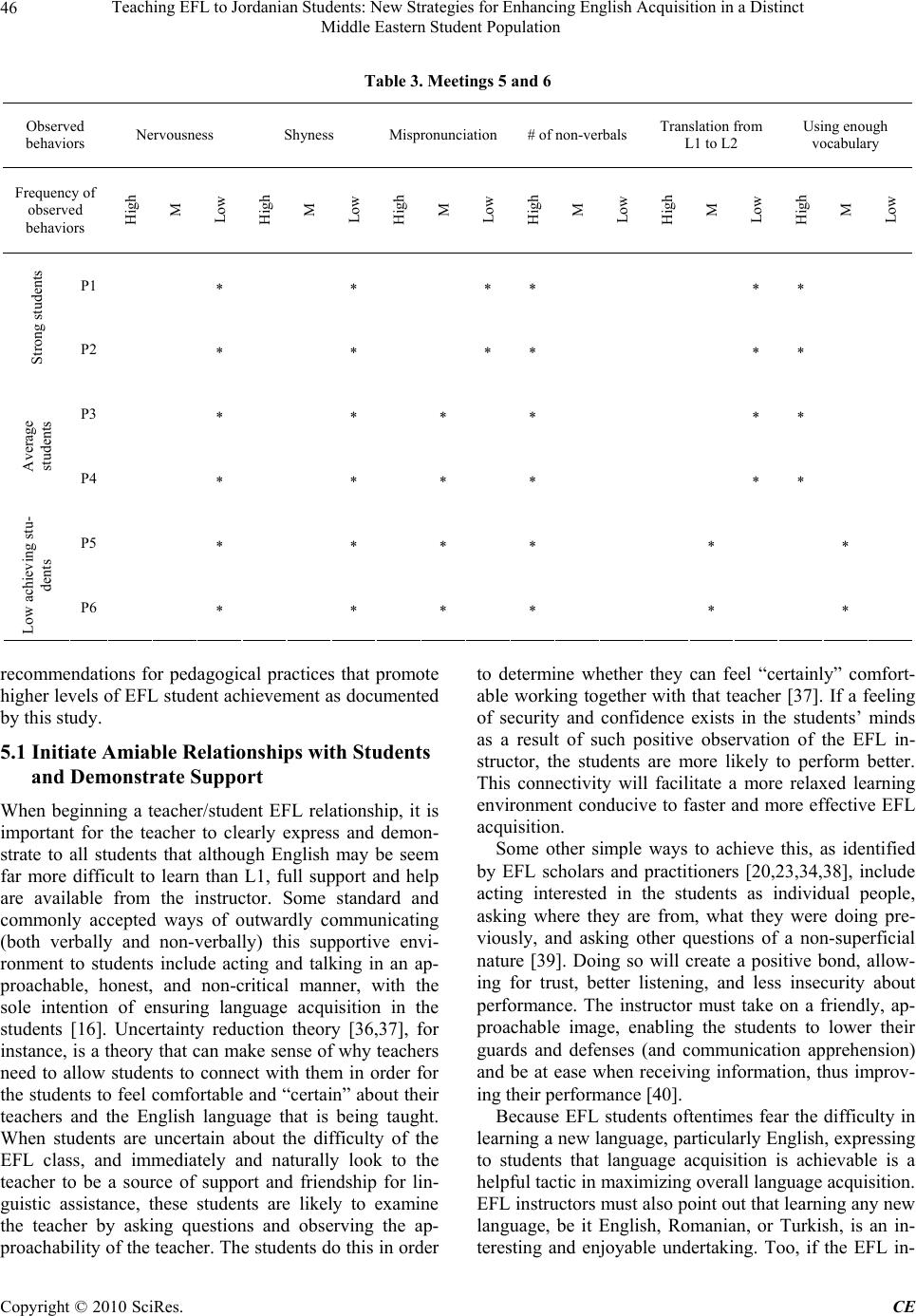

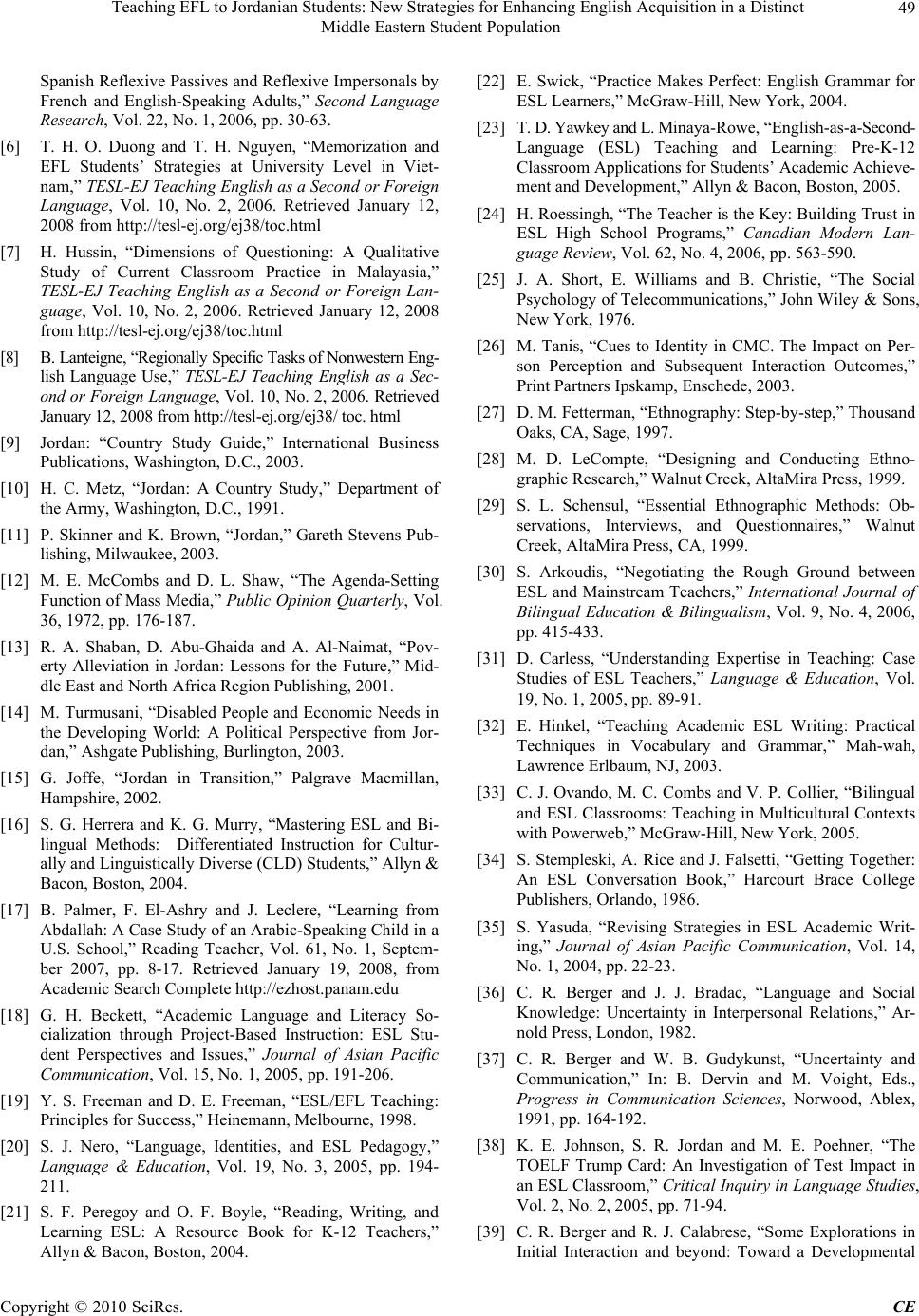

Creative Education, 2010, 1, 39-50 doi:10.4236/ce.2010.11007 Published Online June 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE 39 Teaching EFL to Jordanian Students: New Strategies for Enhancing English Acquisition in a Distinct Middle Eastern Student Population Ibrahem Bani Abdo1, Gerald-Mark Breen2 1Department of English, University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan; 2Department of Public Affairs, University of Central Florida, Orlando, USA. Email: i_khali@yahoo.com, gbreen@mail.ucf.edu Received November 25th, 2009; revised January 19th, 2010; accepted February 18th, 2010. ABSTRACT For EFL students in Jordan, the acquisition of English is particularly challenging because of the pronounced linguistic differences between Arabic and English. This study proposes intersections between communication and language ac- quisition practices to improve delivery of EFL instruction in Jordan, a country in which English enjoys a somewhat ambiguous status in the public school system, higher education, and business and social interactions. We present the results of a quantitative and qualitative analysis of EFL students in Jordan, an area in which little EFL/ESL research has been previously reported. We examine the current EFL pedagogical framework in Jordanian schools, present a quantitative and qualitative analysis of learners’ attitudes, and present a pedagogy that distinctly addresses the needs of Jordanian EFL learners. We conclude with projections of successful EFL instruction as a resource in political, social, and commercial interactions among Jordan, its neighbors, and the United States. Keywords: Arabic, Education, English, Jordan, Middle East, Teaching, TESL 1. Introduction While much research exists on English as a foreign sec- ond language practices in diverse settings, (i.e., China, France, Spain, Brazil, etc.) [1-5], ESL and EFL research has recently begun to examine L2 acquisition among learners in increasingly diverse settings, such as Vietnam, Malaysia and other Asian countries as well as African and Middle-Eastern countries [6-8]. However, despite Jordan’s high profile global image and continual appear- ance in national and international contexts, little research has been conducted or published thus far on specific and effective EFL pedagogy for native Jordanian students. Although one recent study includes Jordanians among its research subjects [8], Lanteigne’s work ultimately pro- vides no insights into EFL practices in Jordan. Under- standably, Middle-Eastern countries in general could be deemed as difficult for on-site, qualitative research(ers), especially for outsiders (i.e., Americans, other foreigners, etc.) wanting to travel to this region for these investiga- tive purposes involving these populations [9-11]. Too, with the constant media coverage and portrayals in line with agenda-setting theory [12] focusing on the violent conflicts taking place in this region of the world, oppor- tunities for research and study of EFL methods in Jordan have been limited. The research study presented here, however, has transcended these limitations through the unique collaboration of an American specialist in com- munication and ESL, an American university professor specializing in pedagogy for bilingual speakers of Eng- lish and Spanish, and a native Jordanian EFL instructor. The essential findings of this study indicate that by ap- plying free-flowing conversations and impromptu oral presentations as primary EFL communication and teach- ing strategies, these Jordanian students tend to achieve effective and fast English language acquisition. Further- more, we feel that as Jordan and neighboring areas of the Middle East continue to play major roles in global poli- tics, this study could have implications for the advance- ment of cultural, political, and social understanding of this region. 2. Education in Jordan The primary, governmentally-sanctioned language in Jordan is Arabic, but English is also commonly commu- nicated in business, administrative, and political sectors in larger, metropolitan sections of the country [13,14].  Teaching EFL to Jordanian Students: New Strategies for Enhancing English Acquisition in a Distinct 40 Middle Eastern Student Population English is sometimes informally spoken by the elite and educated populations throughout the country. Arabic and English are both oftentimes required classes in public and private schools [11]. Also, because many Arabic countries (i.e., Algeria, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Syria, Tunisia, etc.) speak French for occasional communica- tion in various sectors (such as in business and govern- mental settings), French is the only other supplementary language taught at some Jordanian-based schools [9,11, 15]. Approximately 90% of Jordan’s inhabitants are met- ropolitan, while fewer than 10% comprise rural, nomadic groups. Nearly 3 million Jordanian residents classified as Palestinian refugees and displaced individuals dwell in Jordan [13]. Beginning in 2003, a considerable number of Iraqis sought residence in Jordan, primarily due to the Iraqi conflict. However, given these refugees’ reluctance to disclose religious and ethnic affiliations, it is difficult to determine an accurate number of displaced Iraqis [9]. Generally, publicly-sponsored education at the ele- mentary levels in Jordan comprises a series of ten years of continuous and progressive teaching [13,14], similar, but not identical, to the American educational institutions, where K-12 in sequence is standard. Secondary educa- tion comes after this ten-year period. Although secondary education, which usually begins at age 16, is not manda- tory, it consists of a two-year track of sequential study in which students, between 16 to 18, can enroll in either academic or vocational programs [9]. Once this two-year educational track ends, satisfactory students can take a general secondary examination, also known as the Taw- jihi, according to their area of specialty [15]. The stu- dents who complete the test with a passing score are conferred with a special certificate [11]. When students reach the end of this full educational route, they are then automatically qualified to gain admission to universities. In addition, the students who pursue vocational or tech- nical certifications are eligible for admission to local community colleges, universities, or the general business world, granted they satisfactorily complete tests specific to two subject areas [11,15]. The first consists of a series of vocational secondary educational classes. This string of courses gives ample vocational instruction, usually involves an apprenticeship, and eventually allows the student the opportunity to be awarded with another spe- cial certificate [15]. This kind of instruction is sponsored and delivered by the Vocational Training Corporation, under the auspices of the Ministry of Labor/Technical and Vocational Education and Training Higher Council [11]. Entry into post-secondary education is available to re- cipients of the General Secondary Education Certificate. These certificate holders have the options of selecting either private or public community colleges, or public or private universities in Jordan [9]. There is also a program known as the credit-hour system, which enables students to freely choose subject-specific classes based on an ap- proved study plan. This credit-hour system is practiced at many universities in Jordan [15]. Currently, there are eight public universities, including two that were recently certified, and 13 private universi- ties, including four that recently became governmen- tally-approved. All locations where post-secondary edu- cation is delivered operate under the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research [9]. English is generally integrated into Jordanian educa- tion and culture because of business, political, and touris- tic-related demands from international, interactive popu- lations. Bedouins in particular, who are nomadic Arabs who live in the desert and away from cities, are typically without formal education, yet they are still able to com- municate in English because of the frequent presence of tourists (tourism related to camel rides, desert explora- tion, and visits to ancient archeological landmarks) who speak English, as well as other languages. Further, all college graduates from Jordanian universities and col- leges are required to complete coursework in English so that they have an acceptable level of proficiency in the language. Learning English as part of the university re- quirements is also intended to better enable graduates to secure employment in Jordan as well as abroad. Con- versely, the absence of English language acquisition among Jordanians may result in reduced quality of em- ployment, communication, and opportunities in general. Thus, developing communication skills in English pro- vides diverse benefits for Jordanians. 2.1 Linguistic Differences between Arabic and English At present, there is a serious gap and deficiency in Jor- danian students’ abilities to acquire and use spoken Eng- lish effectively for the purpose of general and formal communication. Although English has become a com- mon, global language for the purposes of industry, trade, education, and general communication [16], especially in Jordan school systems, Jordanian students oftentimes have a challenging time acquiring the language, both in written and oral forms. One reason has to do with the considerable differences in the two languages, in terms of alphabetic characters, grammar, syntax, and the overall linguistic logistics of the two languages. Researchers in a recent case study that examines an Arabic-speaking Eng- lish Language Learner in an American school, acknowl- edge the vast differences between English and Arabic, citing numerous negative transfers that could easily in- terfere with the learner’s acquisition of English (L2) [17]. A simple translation example illustrates the challenges faced by EFL students in our study. We offer a transla- Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE  Teaching EFL to Jordanian Students: New Strategies for Enhancing English Acquisition in a Distinct 41 Middle Eastern Student Population tion of a brief passage from the Jordanian newspaper Aldostor Times; also known in Arabic asﻩﺪﻳﺮﺟ رﻮﺘﺳﺪﻟا (). In Arabic, the passage reads as follows: ﻒﻳﺮﺸﻟا ﻲﻨﺴﺣ ﻢﻴﻠﻌﺘﻟاو ﺔﻴﺑﺮ ﺘﻟا ةرازو ﻲﻓ تﺎﻧﺎﺤﺘﻣﻻا ةرادإ ﺮﻳﺪﻣ ﻊﻗو ﺔﻓﺎآ ﺢﻴﺤﺼﺗ ﻦﻣ ءﺎﻬﺘﻧﻻا ةروﺪﻠﻟ ﺔﻳﻮﻧﺎﺜﻟا ﺔﺳارﺪﻟا ةدﺎﻬﺷ نﺎﺤﺘﻣا قاروا ﺮﺧأ نأ ﺎﻤﻠﻋ ، ﻲﻟﺎﺤﻟا ﺮﻬﺸﻟا ﻦﻣ ﻦﻳﺮﺸﻌﻟاو سدﺎﺴﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺔﻴﻟﺎﺤﻟ ا ﺔﻳﻮﺘﺸﻟا ﺮﻬﺸﻟا ﺲﻔﻧ ﻦﻣ ﺮﺸﻋ ﻊﺑﺎﺴﻟا ﻲﻓ نﻮﻜﻴﺳ ﺔﺒﻠﻄﻟا ﻪﻟ مﺪﻘﺘﻴﺳ ﺚﺤﺒﻣ ِِِ (Aldostor Times; January 13, 2008): A smooth English translation of this passage would be the following: On Dec. 26, Husni Al Shareef, Director of the Exami- nation Department at the Ministry of Education signed off on the date for the final administration of exams for the Tawjihie certificate for fall 2007. January 17 will be the final date for administration of the exams which will be scored on January 26. A transliteration of the passage, however, demon- strates the profound syntactic differences between Arabic and English: Signed the director of examination department in min- istry of the Education Husni Al Shareef the process final in correcting all papers exams the Tawjihie’s the certifi- cate for semester fall in 26th in month this, we know that final exam will take students will be in 17th in same month. Transliteration is a rudimentary strategy for moving from L1 to L2, but in languages where syntactic and se- mantic similarities exist, such as between Italian and Spanish or even English and Spanish, an EFL or ESL learners’ acquisition process is considerably eased by reliance on those similarities. The example cited above, however, shows that students whose native language is Arabic would have a particularly challenging learning curve in acquiring proficiency in English. The differences between English and Arabic are too vast to enumerate in detail here, but we offer a short list of key differences to demonstrate the potential for nega- tive transfer that could occur for EFL learners in Jordan [17]: 1) Arabic is written from right to left. 2) Arabic orthography is influenced by placement of the letter in the word; letter shapes vary depending on their occurrence in initial, medial, or end placement in a word. In English, letters change shape only when they are upper case at the beginning of proper nouns or at the beginning of the sentence. 3) Numerous but predictable rules govern the grapho- phonemic treatment of vowels in Arabic, whereas in English grapho-phomenic rules are unpredictable and irregular. 4) Arabic allows verb-free sentences which in English would include a copula. 5) Arabic tenses are indicated by the addition of a suf- fix to a root. In short, the differences are so vast that reliance on Arabic (L1) competence for building English (L2) com- petence would be severely limited for the typical Jorda- nian EFL student. 2.2 ESL Instruction in Jordan Although seemingly paradoxical, another challenge to effective EFL instruction in Jordan is the fact that many EFL instructors are not sufficiently educated, equipped, and/or prepared to specifically accommodate and under- stand the unique linguistic learning styles of some native Jordanian students. One would assume that Jordanian EFL instructors teaching Jordanian students would easily be able to exercise effective pedagogical strategies with learners from their own country; however, our study found that some Jordanian students still struggle in their acquisition of English, in part because instructors fail to apply effective EFL teaching methods. 2.3 Greater Focus on Grades Rather than Linguistic Acquisition Another issue documented through observation and in- terviewing is that Jordanian students, in general, tend to be more focused on achieving good grades in their ESL classes as opposed to concentrating on learning the lan- guage itself. As common sense dictates, and as shown in general EFL/ESL literature [2,18-20], when ESL/EFL students privilege grades over knowledge/competence (which happens to be a common problem amongst many students across the globe), this attitude disposes students to a lack of willingness and motivation to learn. Espe- cially in terms of learning other languages, particularly those that substantially differ from that of their own, this outlook and thinking style considerably interferes with their appreciation, concentration, and eventual acquisi- tion of English [21]. 2.4 Employing Native Language in the Instructional Process Another instructional strategy appropriated by Jordanian EFL teachers is that when a word in English is taught, and if understanding of that word is not immediately gained by the students, the teachers revert back to the Arabic language to explain what the word means. Re- sorting to Arabic in providing translational explanations is usually ineffective because the students need to hear and learn as much English as possible when explanations are being given. This linguistic return in the explanatory process is also a common practice that impedes EFL in- struction across a variety of cultures [20,22]. Using Eng- lish as an alternative in explaining confusing words Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE  Teaching EFL to Jordanian Students: New Strategies for Enhancing English Acquisition in a Distinct 42 Middle Eastern Student Population maximizes student exposure to the English language, hence increasing the quantity of English that they hear, and possibly learn. Using more Arabic in this manner tends to slow down the EFL acquisition process, thereby impeding learners’ linguistic development and minimiz- ing the inherent and pursued benefits in learning the lan- guage quickly and efficaciously. 2.5 Student Diversity and Numbers in Classrooms are too Large In most Jordanian classrooms where EFL is taught, the linguistic competence of students in the same classroom varies widely, but there seems to be little accommodation of the individual learners’ readiness for English acquisi- tion. This failure to take the individual learner into ac- count is a common obstruction to learning in many classrooms across multiple geographic settings [18,23]. In addition, overcrowding in Jordanian EFL classrooms contributes to ineffective pedagogy. Given that EFL in- structors have limited time to teach, and cannot accom- modate, meet and answer to every student at every point in a lecture [24], some students fall behind and may stall in their learning process due to this lack of an individu- alized, teacher-student environment. This deficiency in individualized contact with every student also gives rise to a lack of motivation in some students. The teachers are partially to blame for this, because they simply cannot dedicate special efforts to each student to motivate their enthusiasm to learn effectively [24]. On the other side of the coin, the students are also partially responsible for this lack of motivation, because they, too, have account- ability to themselves to desire and strive to learn the lan- guage by any means possible, even if this means visiting with the teacher outside of class. Social presence theory [25], which posits that a me- dium’s social effects are mainly caused by the extent of social presence which it affords to its users [26], may explain why some Jordanian EFL students feel their teachers lack a personalized interest in them, primarily due to this over-sized classroom environment. In other words, when some EFL students feel that they are not treated with and given sufficient attention by teachers who are supposed to guide them to learn English and ensure their knowledge acquisition, the students’ percep- tions of the teachers decline, sometimes causing a loss of respect and motivation to listen to the EFL instructor. This creates a block in pedagogical and interpersonal communication, and impairs the learning atmosphere. 2.6 An Attitude that ESL is not Important Many Jordanian students in EFL programs also suffer in acquiring the English language because they oftentimes feel that the language itself is not a necessity; some of them feel it is not a practical tool that they’ll use in the future for employment or communication purposes. This attitude is actually a misconception at times, because English does become an important language, especially in Amman, the country’s capitol, where international business and communication take place [11,15]. Of course, not all Jordanian citizens choose to live in re- gions of the country where English is spoken or used. Hence, it depends on the ambitions of the individual stu- dents and whether these individuals desire to venture into occupations or situations that will require a proficient or functional level of English understanding, including oral and written communication skills. 2.7 A Flaw at the Governmental Level A major flaw in EFL teaching, which is due to how the government controls the development of student acquisi- tion of the English language to native, Jordanian students, is that, although a student may not learn and succeed at grasping the language, the educational system is de- signed to only allow a student to fail once [15]. What this means is that a student can only retake the same level class twice. To clarify, if the student fails the first time, the student will retake the same class again the subse- quent year. The second time around, teachers are re- quired to pass and forward the student to the next stage of EFL, even if that student is not capable or prepared to handle the level of EFL taught in those next classes. This also means that the student automatically moves forward in the EFL program even if the quality of work presented by the student is equivalent to a failing grade. 3. Methodology In the context of the obstacles to effective EFL pedagogy we have cited above, we constructed a study designed to identify features of language acquisition instruction that could benefit EFL learners in Jordan. We began with the hypothesis that communication theory and EFL peda- gogy could be merged to provide a scaffolding effect for promoting competence in English in students in Jordan. Through a case-study approach, focused on intensive, formal interactions between the EFL instructor and a small population of EFL students in Jordan, we examined the following research questions: R1: What pedagogical strategies seem to promote learning in EFL students in Jordan? R2: What aspects of communication theory can be used to create a learner friendly environment? The primary, on-site researcher who collected the quantitative data for this study is a native Jordanian and an EFL instructor in Jordan. Additionally, he is currently a graduate student at an American university. The study occurred in a three-week period of observational contact with one elementary and one secondary public school in Jordanian towns designated as a mix between rural and Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE  Teaching EFL to Jordanian Students: New Strategies for Enhancing English Acquisition in a Distinct 43 Middle Eastern Student Population metropolitan. Observations occurred twice each week, for a total of six formal and thorough meetings for the entire EFL sessions, each lasting two hours. The data was collected during the second half of the first semester of the 2005-2006 academic school year. Convenient and random sampling techniques were used to meet with EFL teachers (n = 5; four males and one female) and students (n = 6; five males and one female) on a continuous basis for that three-week period. The on-site researcher also attended many EFL classes, participated and socially interacted with the instructors and students in their ac- tivities and assignments, talked in depth with the teachers and students, and carefully observed and documented the strategies that were deemed “effective” and “ineffective”. The six student participants were categorized into three groups according to their linguistic competence, behavioral characteristics and expressions, and their overall performance as students. We created aliases for our research subjects—P1, P2, P3, P4, P5, and P6. P1 and P2 were designated as “strong” students, P3 and P4 were designated as “average” students, and P5 and P6 were designated as “low-achieving” students. Features examined in the student participants included verbal and non-verbal communication. These included the following exhibitions: 1) nervousness, 2) shyness, 3) mispronuncia- tion, 4) non-verbal communication, 5) translation, and 6) vocabulary. There were two students per group. A high score in features 1, 2, and 3 would indicate high levels of learner discomfort with performance negatively impacted by these features. Conversely, a low score in features 1, 2, and 3 would indicate increasing levels of comfort and increasingly competent linguistic performance in English (L2). A high score in Features 4, 5, and 6 would suggest strong competence in English (L2); a low score would suggest difficulties in demonstrated L2 performance. We used the following rubric in assigning rankings of “high,” “medium,” or “low” to each learner during our interview: Data was collected in six meetings spanning a period of three weeks. In addition, other instructional aspects, such as the classroom settings and conditions, student conduct and attitudes, teacher behavior and demeanor, and other general conditions were observed, analyzed, and documented by the on-site researcher. Participant observation, naturalistic observation, and interviewing were employed as the primary techniques of data collection, and data were examined using a standard ethnographic communication archetype [27-29]. All avail- able data, including field notes of verbal and non-verbal communication (i.e., words, gestures, eye contact, etc.) during the EFL classes, and informants’ verbal state- ments (impromptu and elicited) during individual inter- view sessions, supplied the evidence from which strate- gies deemed “effective” or “ineffective” were identified. 4. Findings and Results Data compiled in interviews with and observations of our subjects is presented in Tables 1, 2, and 3. This tabular data as well as the textual reports suggest a pattern con- firmed systematically via ethnographic and qualitative research methodologies [27,28]. In examining all the compiled qualitative data, as shown below in the tables, there are clear distinctions between ESL pedagogical techniques deemed to be effective and those which seem ineffective. It is assumed that as EFL learners become more comfortable with their instructor, the manifesta- tions of nervousness, shyness, and mispronunciation would decrease. Increased competence in L2, fostered by effective ESL pedagogy, should theoretically result in increases in use of non-verbals, evidence of thinking in L2, and use of enough vocabulary to produce meaningful output [26]. The data in Tables 1, 2, and 3 provide evi- dence that EFL pedagogical practices implemented by the on-site researcher during this study promote increases in EFL learners’ demonstration of competence in L2 (English). By the final meeting, all students demonstrated low levels of nervousness, shyness, and mispronuncia- tion, while use of non-verbals was high for all students, and all students demonstrated at least medium perform- ance levels in translation and use of adequate vocabulary. Data presented here demonstrate that the interactions between the Jordanian EFL teacher/researcher and the research subjects, meetings characterized by free-flowing conversations and impromptu oral presentations, served to enhance EFL instruction and maximize student learn- ing. Our recommendations for increased free-flowing conversations and impromptu oral presentations are based on qualitative and empirical data and support, and we believe that applying these tactics will develop ESL fluency and proficiency for these particular student pop- ulations in Jordan. 5. Recommendations for Effective EFL Instruction The special circumstances of EFL instruction in Jordan, as detailed above, and the pronounced differences between Arabic (L1) and English (L2) clearly point to the need for research-based and learner-centered pedagogy for Jordanian EFL students. Much research has been con- ducted with observed, verifiable success on how to prop- erly conduct EFL instruction to a variety of cultures and ethnicities [2,16,18,19,22,30-35] These instructional strategies have been utilized by EFL teachers with a con- tinuous, progressive movement to better train foreign or non-native English speakers in oral and written commu- nication for informal and formal purposes, which are manifested as personal, social, political, and/or economic otivations for acquisition of English. We detail these as m Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE  Teaching EFL to Jordanian Students: New Strategies for Enhancing English Acquisition in a Distinct Middle Eastern Student Population Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE 44 Performance Levels High Medium Low Nervousness Numerous instances of the following physical manifestations: shaking or trembling, fidgeting, blushing, silence. Learners’ demonstration of competence is L2 is significantly reduced by ob- served nervousness. Some instances of the following physi- cal manifestations: shaking or trem- bling, fidgeting, blushing, silence. Learners’ demonstration of competence is L2 is somewhat reduced by observed nervousness. Few to no instances of the following physical manifestations: shaking or trembling, fidgeting, blushing, silence. Learners’ demonstration of competence is L2 is minimally or not reduced by observed nervousness. Shyness Numerous instances of the following physical and linguistic manifestations: avoidance of eye contact, reluctance to ask questions, low vocal volume, mum- bling. Learners’ demonstration of com- petence is L2 is significantly reduced by observed shyness. Some instances of the following physi- cal and linguistic manifestations: avoidance of eye contact, reluctance to ask questions, low vocal volume, mum- bling. Learners’ demonstration of com- petence is L2 is somewhat reduced by observed shyness. Few to no instances of the following physical and linguistic manifestations: avoidance of eye contact, reluctance to ask questions, low vocal volume, mum- bling. Learners’ demonstration of com- petence is L2 is minimally or not re- duced by observed shyness. Mispronunciation L2 vocabulary is mispronounced 50% or more of the time during the observation. Learners’ demonstration of competence is L2 is significantly reduced by mis- pronunciations of L2 language struc- tures. L2 vocabulary is mispronounced 30%-50% of the time during the obser- vation. Learners’ demonstration of competence is L2 is somewhat reduced by mispronunciations of L2 language structures. L2 vocabulary is mispronounced 10% to 0% of the time during the observation. Learners’ demonstration of competence is L2 is minimally or not reduced by mispronunciations of L2 language structures. Non verbal communication Learner’s use of the following non-verbals significantly enhance per- formance in L2: facial gestures, body language (such as “speaking with your hands”), nodding or shaking the head, self-initiated movement from one place to another in the observation site, eye contact. Learner’s use of the following non-verbals somewhat enhance per- formance in L2: facial gestures, body language (such as “speaking with your hands”), nodding or shaking the head, self-initiated movement from one place to another in the observation site, eye contact. Learner’s use of the following non-verbals is limited and does not enhance performance in L2: facial ges- tures, body language (such as “speaking with your hands”), nodding or shaking the head, self- initiated movement from one place to another in the observation site, eye contact. Translation Learner’s performance in L2 demon- strates limited to no fluency, suggesting that the learner is primarily translating from L1 to L2 rather than thinking in L2. Lapses in fluency significantly diminish demonstration of competence in L2. Learner’s performance in L2 demon- strates some fluency, suggesting that the learner is attempting to think in L2 rather than translating from L1 to L2. Lapses in fluency are obvious but do not significantly diminish demonstration of competence in L2. Learner’s performance in L2 is fluid and fluent, suggesting that the learner is thinking in L2 rather than translating from L1 to L2. Linguistic and behavioral features Vocabulary Learner consistently uses varied, ade- quate, and appropriate vocabulary in L2. Learners’ demonstration of competence is L2 is significantly enhanced by un- derstanding and use of L2 vocabulary. Learner inconsistently uses varied, adequate, and appropriate vocabulary in L2. Learners’ demonstration of compe- tence is L2 is somewhat reduced by inconsistent understanding and use of L2 vocabulary. Learner consistently misuses vocabulary or fails to demonstrate use of sufficient vocabulary in L2. Learners’ demonstra- tion of competence is L2 is significantly by inadequate understanding and use of L2 vocabulary. Figure 1. Rubric for assessing Jordanian EFL learners’ competence in English  Teaching EFL to Jordanian Students: New Strategies for Enhancing English Acquisition in a Distinct 45 Middle Eastern Student Population Table 1. Meetings 1 and 2 Observed behaviors Nervousness Shyness Mispronunciation# of non-verbals Translation from L1 to L2 Using enough vocabulary Frequency of observed behaviors High M Low High M Low High M Low High M Low High M Low High M Low P1 Strong students P2 P3 Average students P4 P5 Low achieving students P6 Table 2. Meetings 3 and 4 Observed behaviors Nervousness Shyness Mispronunciation# of non-verbals Translation from L1 to L2 Using enough vocabulary Frequency of observed behaviors High M Low High M Low High M Low High M Low High M Low High M Low P1 Strong students P2 P3 Average students P4 P5 Low achieving students P6 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE  Teaching EFL to Jordanian Students: New Strategies for Enhancing English Acquisition in a Distinct Middle Eastern Student Population Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE 46 Table 3. Meetings 5 and 6 Observed behaviors Nervousness Shyness Mispronunciation# of non-verbals Translation from L1 to L2 Using enough vocabulary Frequency of observed behaviors High M Low High M Low High M Low High M Low High M Low High M Low P1 Strong students P2 P3 Average students P4 P5 Low achieving stu- dents P6 recommendations for pedagogical practices that promote higher levels of EFL student achievement as documented by this study. 5.1 Initiate Amiable Relationships with Students and Demonstrate Support When beginning a teacher/student EFL relationship, it is important for the teacher to clearly express and demon- strate to all students that although English may be seem far more difficult to learn than L1, full support and help are available from the instructor. Some standard and commonly accepted ways of outwardly communicating (both verbally and non-verbally) this supportive envi- ronment to students include acting and talking in an ap- proachable, honest, and non-critical manner, with the sole intention of ensuring language acquisition in the students [16]. Uncertainty reduction theory [36,37], for instance, is a theory that can make sense of why teachers need to allow students to connect with them in order for the students to feel comfortable and “certain” about their teachers and the English language that is being taught. When students are uncertain about the difficulty of the EFL class, and immediately and naturally look to the teacher to be a source of support and friendship for lin- guistic assistance, these students are likely to examine the teacher by asking questions and observing the ap- proachability of the teacher. The students do this in order to determine whether they can feel “certainly” comfort- able working together with that teacher [37]. If a feeling of security and confidence exists in the students’ minds as a result of such positive observation of the EFL in- structor, the students are more likely to perform better. This connectivity will facilitate a more relaxed learning environment conducive to faster and more effective EFL acquisition. Some other simple ways to achieve this, as identified by EFL scholars and practitioners [20,23,34,38], include acting interested in the students as individual people, asking where they are from, what they were doing pre- viously, and asking other questions of a non-superficial nature [39]. Doing so will create a positive bond, allow- ing for trust, better listening, and less insecurity about performance. The instructor must take on a friendly, ap- proachable image, enabling the students to lower their guards and defenses (and communication apprehension) and be at ease when receiving information, thus improv- ing their performance [40]. Because EFL students oftentimes fear the difficulty in learning a new language, particularly English, expressing to students that language acquisition is achievable is a helpful tactic in maximizing overall language acquisition. EFL instructors must also point out that learning any new language, be it English, Romanian, or Turkish, is an in- teresting and enjoyable undertaking. Too, if the EFL in-  Teaching EFL to Jordanian Students: New Strategies for Enhancing English Acquisition in a Distinct 47 Middle Eastern Student Population structor establishes rapport and a sense of community and connectivity with the students, increased cooperation, attentiveness, and attendance of the class are likely to result, thereby enhancing and facilitating the learning environment [23,39]. 5.2 Identify Customs and Norms of Students and Act Them Out A great deal of EFL and intercultural communication literature focuses on the importance of understanding the cultural and ethnic norms, customs, practices, and atti- tudes of EFL students, given their various international backgrounds [2,19,31,41]. Understanding these various aspects of ESL students will naturally enable the instruc- tors to cater and conduct themselves in manners that will gain acceptance, appreciation, connectivity, and commu- nication efficacy with the students. Watching behaviors of the students in class, too, based on social cognitive theory, a theory that posits that we learn and can then imitate behavioral styles based on observation [42,43], can enable the instructors to mimic the students and, therefore, mirror the behaviors and customs of the stu- dents. In another way, striving to transform oneself in a like image of the cultures in the EFL classroom, also in line with specific theoretical assumptions from face ne- gotiation theory [44], will likely increase the chances of a general “opening up” of the students, decrease their communication apprehension [40], increase their general comfort levels in the learning atmosphere, and help to eliminate any interpersonal conflict so as to develop and secure a relational bond [44-46] between the students and the teacher. Put differently, if the teacher seems like an insider, as opposed to an outsider or foreigner, far better listening, reception and likeability are more apt to present themselves from the students to the teachers. 5.3 Patience, Gentleness, and a Polite Attitude Because of intercultural and interpersonal communica- tion issues in international students, such as communica- tion apprehension, avoidance, and introversion, patience, gentleness, and a polite attitude and demeanor from the EFL instructor will help to facilitate connectivity with the students and thus minimize these barriers to learning [1]. As language expectancy theory posits, tactful lin- guistic word choices can be important predictors of per- suasive success [47,48]. For example, if an EFL instruc- tor uses words of a patient, gentle, and polite nature, the EFL students will be persuaded that the teacher is ap- proachable, credible, supportive, and helpful. This will enable connectivity between the teachers and the students. Hence, the tone, intensity, and selection of the language used by the EFL instructor to encourage and persuade students to feel comfortable and capable of learning Eng- lish has a significant impact on the efficacy of EFL pedagogy and the rate of student learning acquisition. Politeness, specifically, builds trust between students, as suggested by politeness theory [49,50]. Too, allowing EFL students ample time to think, without exhibiting a sense of haste or pressure on the part of the teacher, will serve to alleviate the stress EFL students experience in wanting to pronounce words correctly, think of the cor- rect words to use for questions and answers, and com- municate their thoughts and expressions in a natural and graceful manner [41]. When an EFL student notices or senses that there is some pressure or impatience from the instructor to answer, levels of anxiety and communica- tion apprehension usually escalate. This type of anxious elevation typically leads to deterioration in the stu- dent-teacher relationship, contributes to an increased level of performance anxiety and communication appre- hension, and tends to decrease the overall learning proc- ess [2,19,41]. It is also important to take into account that creating a non-threatening environment, in which the students feel comfortable making mistakes in grammar, verbal com- munication, and writing, is crucial in making students feel secure making errors. It will also help persuade and convince them, without shame, that mistakes are a natu- ral part of the learning process [19,48]. Plus, the EFL instructor should not resort to negative response to the learner’s performance; that is counterproductive and un- ethical and has the potential to be irreversibly defeating to the relationships [2]. Research has shown that EFL instructors in particular who present themselves with a smile and other positive facial expressions, occasionally give compliments regarding the students’ efforts, and refrain from showing any signs of upset or disappoint- ment (such as sighs), enhance general student motivation and learning acquisition [2,19]. Also, such linguistic and non- verbal communication can be persuasive to students in their attitudes and desires to actively pursue learning [47], particularly in ESL programs. The students also lose any sense or belief in a lack of communication competence or aptness in learning their new language [20]. Clearly, patience and courtesy, especially, go a long way in breaking through many learning barriers and communication apprehensions [49]. When an EFL in- structor slowly, clearly, and pleasantly pronounces L2 words, corrects grammar errors and explains the source of the error, and repeats him/ herself in an encouraging tone, the pedagogical result is continued rapport and in- creased learning in the EFL student [41]. In a similar vein, as with anyone learning a new lan- guage, the EFL instructor should also clearly articulate and pronounce words, using a placid and encouraging tone, in order to avoid or minimize misunderstanding or misinterpretation of the particular words orally commu- Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE  Teaching EFL to Jordanian Students: New Strategies for Enhancing English Acquisition in a Distinct 48 Middle Eastern Student Population nicated. If this strategy is applied and, still, misunder- standing occurs, it helps to gently repeat the word in question until the said EFL student can effectively grasp how to pronounce the word (s) properly. Further, some- times EFL students will appear frustrated or despondent because they are unable to clearly and correctly pro- nounce certain words. Research suggests that assuring them that they will do fine, and, again, their mistakes are all part of the learning process, will usually maintain the EFL students’ confidence and motivation [19]. Surprisingly, negative communication that interferes with the learning acquisition rates and abilities of EFL students, especially across a variety of cultures, involves the use of certain colored pens [2]. Instead of using a red pen to identify errors on written assignments for EFL students, which, as some researchers have found, implies harshness, negativity, scrutiny, and hurtfulness [51,52], EFL instructors should use more symbolically benign colored pens, such as blue, yellow, or another color, which do not represent or depict a wrongdoing and should clearly explain to the learner how linguistic and/ or rhetorical problems can be corrected [51,53]. Al- though it is important to clearly document a mistake and assure that the EFL student is aware of what was done incorrectly, something commonly perceived as minor actually holds tremendous implications and can nega- tively affect student performance, motivation, and per- sistence [2,51]. 6. Discussion and Future Directions This qualitative and communication research report on language and social interaction has provided new insight into how the Jordanian EFL programs in elementary and secondary-level schools operate, and which teaching strategies appear to be effective in promoting higher lev- els of achievement in L2 competence and performance. It is important to recognize what strategies work best in teaching EFL to students in general and Jordanian stu- dents in particular. The intensive, focused study reported here permits extrapolation of data that can be applied to student populations larger than the research population. Data provided by the on-site researcher’s extended inter- actions with Jordanian EFL students enables us to iden- tify strategies that can be applied in a larger context for improved acquisition of English by Jordanian students. By identifying these proper strategies, and through mass implementation of them, a vast increase in English lan- guage acquisition could occur in this Middle-Eastern population. Too, because English is a common language used in business and governmental sectors within Jordan, particularly in the metropolitan areas, it is critical that the citizens of this country understand and can communicate the language properly so as to improve their economy, cross-cultural or intercultural communication, and inter- national relations. More importantly, a country’s (espe- cially Jordan’s, which is a Middle-Eastern country, sur- rounded by some dangerous populations) criminal justice experts or negotiators must be able to understand a lan- guage (such as English, intermittently) that terrorists from other countries may use to hold hostages or threaten to initiate some kind of violent or significant conflict [54] in order for the negotiators to attempt to ameliorate or resolve these types of conflicts before escalation or fa- talities occur. Moreover, although Jordan is only one of many Mid- dle-Eastern countries in this region of the world, it is practically in the center of the Middle East, where Mus- lims are prevalent and predominant and where Arabic is the primary language. Also, because Jordan is a neutral country in terms of war and conflict [9,15], and because Jordan sits in the middle of Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Iran, and Saudi Arabia—countries that always seem to be involved in some kind of violent conflict—increased acquisition and communication of English amongst Jor- danian residents may serve to help other English-speaking countries in the fight against terrorism, extremist think- ing and acts of violence, and overall conflict in all these other Middle-Eastern countries surrounding Jordan. Also, Jordan can serve as a buffer or mediator between all these Middle-Eastern countries, and can launch a mas- sive campaign to publicly denounce, discourage, and attempt to bring to an end the pernicious conduct that pervades populations across the Middle East. The politi- cal and global implications of increasing understanding of the English language in Jordan and other areas of the Middle East cannot be overestimated. The need for un- derstanding of language as a critical part of understand- ing of culture and politics [55] has made it expedient to recognize and promote effective pedagogy for EFL learners in Jordan and other Middle Eastern nations. REFERENCES [1] R. S. Berry and M. Williams, “In at the Deep End: Diffi- culties Experienced by Hong Kong,” Journal of Lan- guage & Social Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1, 2004, pp. 118-134. [2] D. E. Freeman and Y. S. Freeman, “Essential Linguistics: What You Need to Know to Teach Reading, ESL, Spell- ing, Phonics, and Grammar,” Heinemann, Melbourne, 2004. [3] D. Fu, “An Island of English: Teaching ESL in China- town,” Heinemann, Melbourne, 2003. [4] D. Santos and B. F. Fabricio, “The English Lesson as a Site for the Development of Critical Thinking,” TESL-EJ Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2006. Retrieved January 12, 2008 from http:// tesl-ej.org/ej38/toc.html [5] A. Tremblay, “On the Second Language Acquisition of Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE  Teaching EFL to Jordanian Students: New Strategies for Enhancing English Acquisition in a Distinct 49 Middle Eastern Student Population Spanish Reflexive Passives and Reflexive Impersonals by French and English-Speaking Adults,” Second Language Research, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2006, pp. 30-63. [6] T. H. O. Duong and T. H. Nguyen, “Memorization and EFL Students’ Strategies at University Level in Viet- nam,” TESL-EJ Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2006. Retrieved January 12, 2008 from http://tesl-ej.org/ej38/toc.html [7] H. Hussin, “Dimensions of Questioning: A Qualitative Study of Current Classroom Practice in Malayasia,” TESL-EJ Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Lan- guage, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2006. Retrieved January 12, 2008 from http://tesl-ej.org/ej38/toc.html [8] B. Lanteigne, “Regionally Specific Tasks of Nonwestern Eng- lish Language Use,” TESL-EJ Teaching English as a Sec- ond or Foreign Language, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2006. Retrieved January 12, 2008 from http://tesl-ej.org/ej38/ toc. html [9] Jordan: “Country Study Guide,” International Business Publications, Washington, D.C., 2003. [10] H. C. Metz, “Jordan: A Country Study,” Department of the Army, Washington, D.C., 1991. [11] P. Skinner and K. Brown, “Jordan,” Gareth Stevens Pub- lishing, Milwaukee, 2003. [12] M. E. McCombs and D. L. Shaw, “The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass Media,” Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 36, 1972, pp. 176-187. [13] R. A. Shaban, D. Abu-Ghaida and A. Al-Naimat, “Pov- erty Alleviation in Jordan: Lessons for the Future,” Mid- dle East and North Africa Region Publishing, 2001. [14] M. Turmusani, “Disabled People and Economic Needs in the Developing World: A Political Perspective from Jor- dan,” Ashgate Publishing, Burlington, 2003. [15] G. Joffe, “Jordan in Transition,” Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire, 2002. [16] S. G. Herrera and K. G. Murry, “Mastering ESL and Bi- lingual Methods: Differentiated Instruction for Cultur- ally and Linguistically Diverse (CLD) Students,” Allyn & Bacon, Boston, 2004. [17] B. Palmer, F. El-Ashry and J. Leclere, “Learning from Abdallah: A Case Study of an Arabic-Speaking Child in a U.S. School,” Reading Teacher, Vol. 61, No. 1, Septem- ber 2007, pp. 8-17. Retrieved January 19, 2008, from Academic Search Complete http://ezhost.panam.edu [18] G. H. Beckett, “Academic Language and Literacy So- cialization through Project-Based Instruction: ESL Stu- dent Perspectives and Issues,” Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2005, pp. 191-206. [19] Y. S. Freeman and D. E. Freeman, “ESL/EFL Teaching: Principles for Success,” Heinemann, Melbourne, 1998. [20] S. J. Nero, “Language, Identities, and ESL Pedagogy,” Language & Education, Vol. 19, No. 3, 2005, pp. 194- 211. [21] S. F. Peregoy and O. F. Boyle, “Reading, Writing, and Learning ESL: A Resource Book for K-12 Teachers,” Allyn & Bacon, Boston, 2004. [22] E. Swick, “Practice Makes Perfect: English Grammar for ESL Learners,” McGraw-Hill, New York, 2004. [23] T. D. Yawkey and L. Minaya-Rowe, “English-as-a-Second- Language (ESL) Teaching and Learning: Pre-K-12 Classroom Applications for Students’ Academic Achieve- ment and Development,” Allyn & Bacon, Boston, 2005. [24] H. Roessingh, “The Teacher is the Key: Building Trust in ESL High School Programs,” Canadian Modern Lan- guage Review, Vol. 62, No. 4, 2006, pp. 563-590. [25] J. A. Short, E. Williams and B. Christie, “The Social Psychology of Telecommunications,” John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1976. [26] M. Tanis, “Cues to Identity in CMC. The Impact on Per- son Perception and Subsequent Interaction Outcomes,” Print Partners Ipskamp, Enschede, 2003. [27] D. M. Fetterman, “Ethnography: Step-by-step,” Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage, 1997. [28] M. D. LeCompte, “Designing and Conducting Ethno- graphic Research,” Walnut Creek, AltaMira Press, 1999. [29] S. L. Schensul, “Essential Ethnographic Methods: Ob- servations, Interviews, and Questionnaires,” Walnut Creek, AltaMira Press, CA, 1999. [30] S. Arkoudis, “Negotiating the Rough Ground between ESL and Mainstream Teachers,” International Journal of Bilingual Education & Bilingualism, Vol. 9, No. 4, 2006, pp. 415-433. [31] D. Carless, “Understanding Expertise in Teaching: Case Studies of ESL Teachers,” Language & Education, Vol. 19, No. 1, 2005, pp. 89-91. [32] E. Hinkel, “Teaching Academic ESL Writing: Practical Techniques in Vocabulary and Grammar,” Mah-wah, Lawrence Erlbaum, NJ, 2003. [33] C. J. Ovando, M. C. Combs and V. P. Collier, “Bilingual and ESL Classrooms: Teaching in Multicultural Contexts with Powerweb,” McGraw-Hill, New York, 2005. [34] S. Stempleski, A. Rice and J. Falsetti, “Getting Together: An ESL Conversation Book,” Harcourt Brace College Publishers, Orlando, 1986. [35] S. Yasuda, “Revising Strategies in ESL Academic Writ- ing,” Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2004, pp. 22-23. [36] C. R. Berger and J. J. Bradac, “Language and Social Knowledge: Uncertainty in Interpersonal Relations,” Ar- nold Press, London, 1982. [37] C. R. Berger and W. B. Gudykunst, “Uncertainty and Communication,” In: B. Dervin and M. Voight, Eds., Progress in Communication Sciences, Norwood, Ablex, 1991, pp. 164-192. [38] K. E. Johnson, S. R. Jordan and M. E. Poehner, “The TOELF Trump Card: An Investigation of Test Impact in an ESL Classroom,” Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2005, pp. 71-94. [39] C. R. Berger and R. J. Calabrese, “Some Explorations in Initial Interaction and beyond: Toward a Developmental Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE  Teaching EFL to Jordanian Students: New Strategies for Enhancing English Acquisition in a Distinct Middle Eastern Student Population Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE 50 Theory of Interpersonal Communication,” Human Com- munication Theory, Vol. 1, 1975, pp. 99-112. [40] L. R. Lippert, B. S. Titsworth and S. K. Hunt, “Ecology of Academic Risk: Relationships between Communica- tion Apprehension, Verbal Aggression, Supportive Com- munication, and Students’ Academic Risk Status,” Com- munication Studies, Vol. 56, No. 1, 2005, pp. 1-21. [41] Y. Kobayashi, “Interethnic Relations between ESL Stu- dents,” Journal of Multilingual & Multicultural Develo- pment, Vol. 27, No. 3, 2006, pp. 181-195. [42] K. Miller, “Communication Theories: Perspectives, Proc- esses, and Contexts,” 2nd Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York, 2002. [43] A. Bandura, “Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentive Perspective,” Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 52, 2001, pp. 1-26. [44] J. G. Oetzel and S. Ting-Toomey, “Face Concerns in Interpersonal Conflict: A Cross-Cultural Empirical Test of the Face Negotiation Theory,” Communication Re- search, Vol. 30, No. 6, 2003, pp. 599-624. [45] D. R. Peterson, “Conflict,” In: H. H. Kelley, Ed., Close Relationships, W. H. Free-man, New York, 1983, pp. 360-396. [46] M. E. Roloff, “Communication and Conflict,” In: C. R. Berger and S. H. Chaffee, Eds., Handbook of Communi- cation Science, Newbury Park, Sage, CA, 1987, pp. 484-534. [47] J. K. Burgoon and M. Burgoon, “Expectancy Theories,” In: W. P. Robinson and H. Giles, Eds., The New Hand- book of Language and Social Psychology, Sussex, Wiley, 2001, pp. 79-102. [48] J. P. Dillard and M. Pfau, “The Persuasion Handbook: Developments in Theory and Practice,” Thousand Oaks, Sage, CA, 2002. [49] P. Brown and S. Levinson, “Universals in Language Us- age: Politeness Phenomena,” In: E. N. Goody, Ed., Ques- tions and Politeness: Strategies in Social Interaction, Cambridge University Press, New York, 1978, pp. 56- 289. [50] S. Harris, “Being Politically Impolite: Extending Polite- ness Theory to Adversarial Political Discourse,” Dis- course & Society, Vol. 12, No. 4, 2001, pp. 451-472. [51] R. B. Hupka, Z. Zaleski, J. Otto, L. Reidl and N. V. Ta- rabrina, “The Colors of Anger, Envy, Fear, and JealOusy: A Cross-Cultural Study,” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psy- chology, Vol. 28, 1997, pp. 156-171. [52] B. M. Newman, “Centering in the Borderlands: The Writ- ing Center at Hispanic-Serving Institutions,” The Writing Center Journal, Vol. 23, No. 2, 2003, pp. 45-62. [53] B. M. Newman, “Teaching Writing at Hispanic Serving Institutions,” In: C. Kirklighter, D. Cardenas and S. W. Murphy, Eds., Teaching Writing with Latino/a Students: Lessons Learned at Hispanic Serving Institutions, State University of New York Press, Albany, 2007, pp. 17-35. [54] J. Matusitz and G. M. Breen, “Negotiation Tactics in Organizations Applied to Hostage Negotiation,” Journal of Security Education, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2006, pp. 53-72. [55] T. Taha, “Arabic as a Critical-Need Foreign Language in Post-9/11 Era: A Study of Students’ Attitudes and Moti- vation,” Journal of Instructional Psychology, Vol. 34, No. 3, September 2007, pp. 150-160. Retrieved January 19, 2008, from Academic Search Complete http://ezhost. pa- nam.edu |