Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

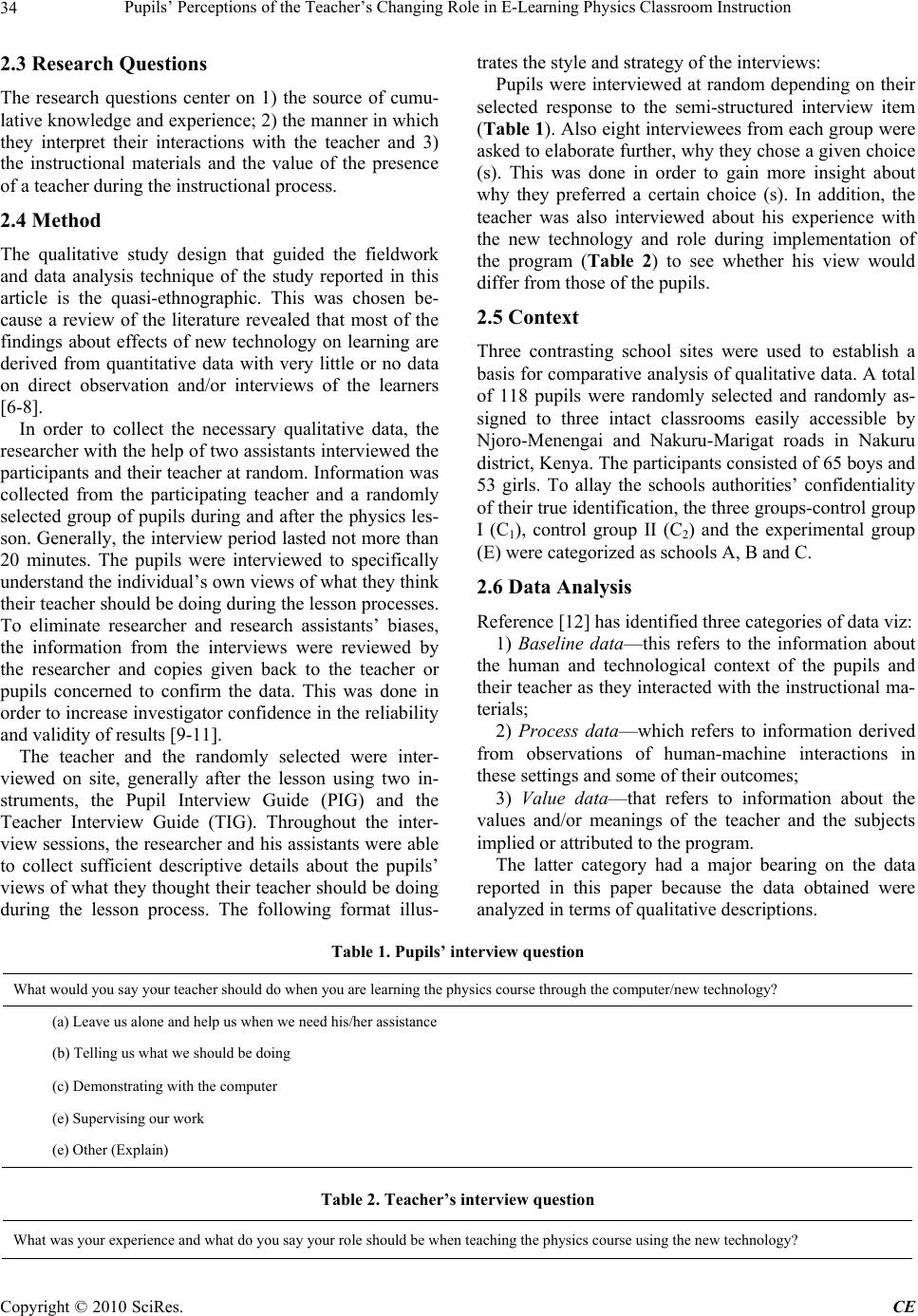

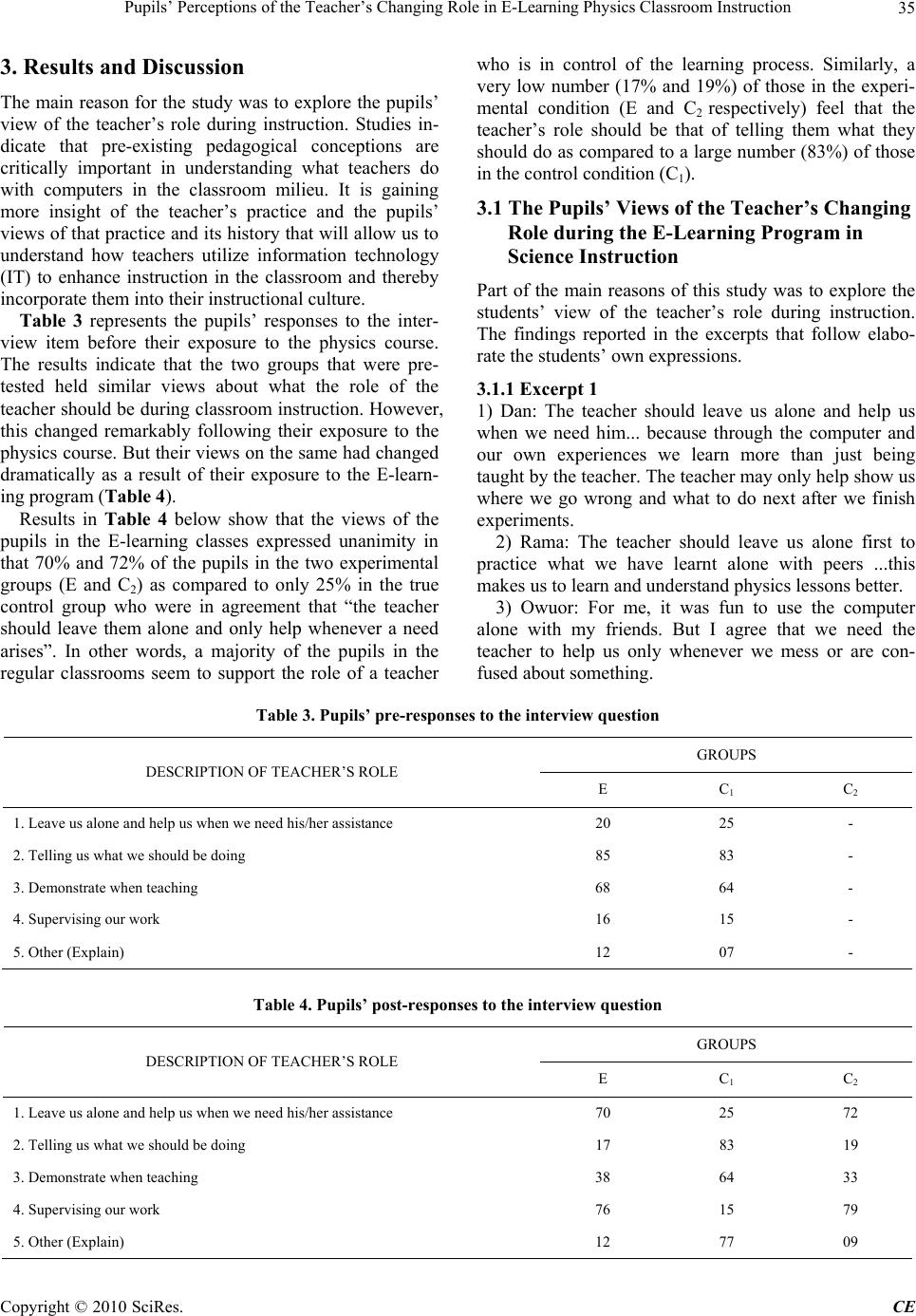

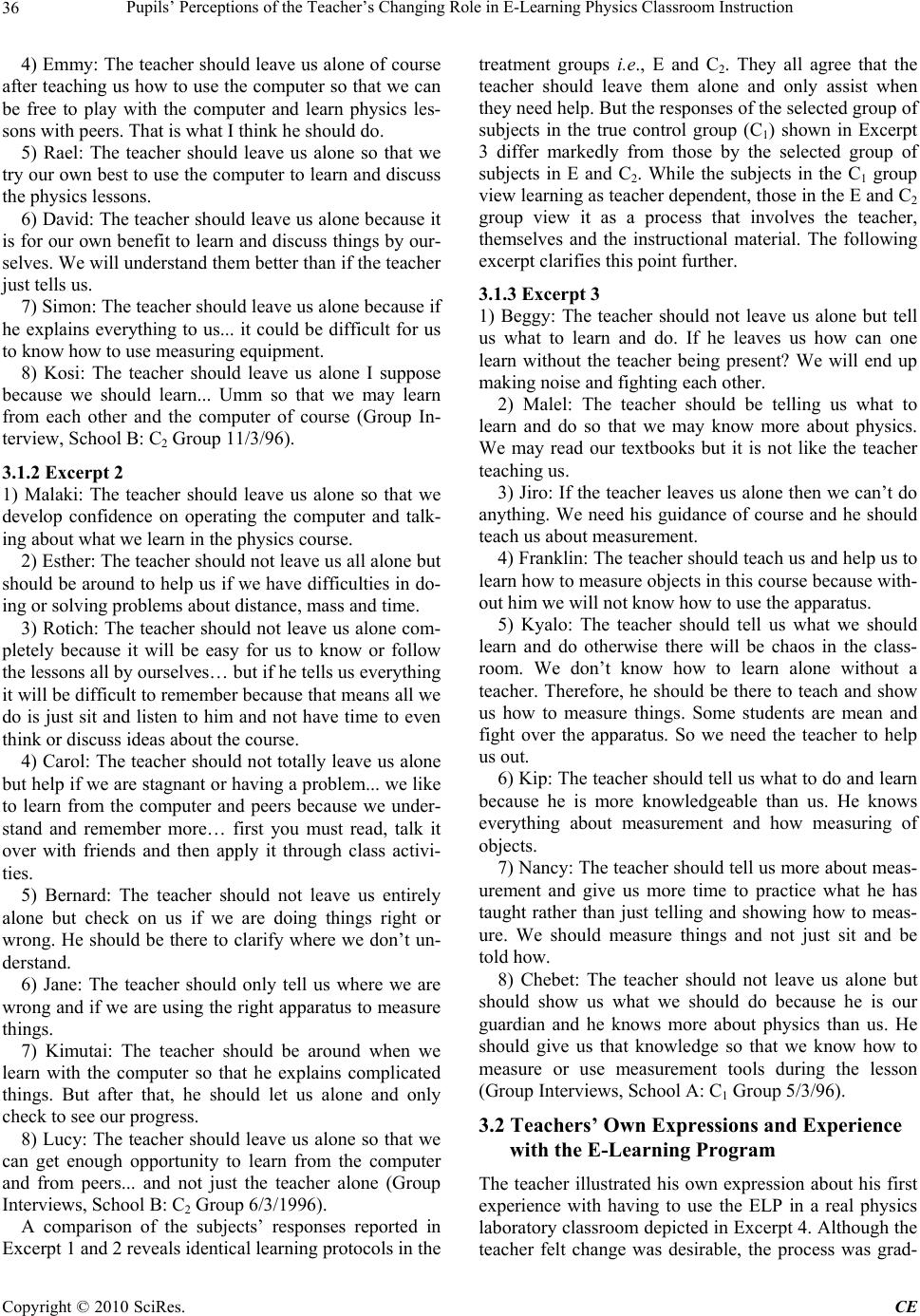

Creative Education, 2010, 1, 33-38 doi:10.4236/ce.2010.11006 Published Online June 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE 33 Pupils’ Perceptions of the Teacher’s Changing Role in E-Learning Physics Classroom Instruction Joel K. Kiboss Department of Curriculum, Instruction and Educational Management, Egerton University, Egerton, Kenya. Email: kiboss@yahoo.com Received December 28th, 2009; revised March 8th, 2010; accepted May 1st, 2010. ABSTRACT This article explores the pupils’ view of the teacher’s changing role as a result of the implementation of an innovation that involved electronic learning measurement lessons in a developing country, namely Kenya. 118 randomly pupils enrolled in schools that could be visited conveniently in Nakuru district, Kenya were exposed to an electronic learning program (ELP) in physics. The ELP physics module was developed from a physics course dealing with the concept of measurement. The content was based on the Kenya Institute of Education (KIE) approved syllabus for science educa- tion, science textbooks and other relevant materials. Part of the investigation was to determine the effect of the ELP physics module on pupils’ perspectives of the teacher’s role during the physics course. The participants were inter- viewed at random using the Pupils’ Interview Guide (PIG). A selected group of pupils’ own expressions were also ana- lyzed. The results showed that the conceptions of the pupils who were exposed to the e-learning program and those not so exposed differed remarkably. For, the pupils in the experimental condition depended more on their peers and the program while their counterparts in the traditional class were more dependent on the teacher. The study concludes that the use of ELP module to support conventional physics instruction can have substantial advantages over other approaches. Keywords: Electronic Learning, Expository Teaching, Changing Role, Innovation 1. Introduction The initial goal of augmenting conventional instruction with the computer in the West was to improve the quality of instruction by providing individualized instruction. Although the overall effectiveness of electronic learning programs is still a subject of debate, there is a plethora of findings for and against its inclusion in instructional practice [1-4]. Moreover, there has also been a disagree- ment regarding the control of the sequence of instruction [5]. A review of the literature revealed that some argue that the control should be in the hands of the learner and/or the teacher while others suggest that it should be the responsibility of the program designer to provide such a mechanism. So long as it is able to collect and analyze the response data from the learners and thereby make optimal automatic decisions about the sequence of instruction. However, it is too early to pronounce a ver- dict on its effectiveness or otherwise until baseline data are available from the different regions in the world. 2. Outline of the Project 2.1 The Problem Although studies about the effect of electronic learning (e-learning) programs on pupils’ learning of various sub- jects abound, no study known to this researcher has looked into the learner’s own view regarding the role of the teacher during an e-learning instructional process. Its understanding, especially in a country where the teacher has been in total control of instruction is crucial because such views work together with other mediating factors to revamp the classroom practice and e-learning environ- ments [5]. 2.2 Purpose The research reported here was undertaken to documents a comparative study of the views pupils hold regarding the role of the teacher in instructional processes that in- volve the use of e-learning program (ELP) to support conventional instruction in physics. In particular, it was hoped that the study would revealed features of the teacher’s role that impinge on the pupils’ classroom learning and participation during instruction. The study was conducted within normal classroom settings in which the pupils were viewed as the active participants in the construction of the new knowledge and/or experi- ence.  Pupils’ Perceptions of the Teacher’s Changing Role in E-Learning Physics Classroom Instruction 34 2.3 Research Questions The research questions center on 1) the source of cumu- lative knowledge and experience; 2) the manner in which they interpret their interactions with the teacher and 3) the instructional materials and the value of the presence of a teacher during the instructional process. 2.4 Method The qualitative study design that guided the fieldwork and data analysis technique of the study reported in this article is the quasi-ethnographic. This was chosen be- cause a review of the literature revealed that most of the findings about effects of new technology on learning are derived from quantitative data with very little or no data on direct observation and/or interviews of the learners [6-8]. In order to collect the necessary qualitative data, the researcher with the help of two assistants interviewed the participants and their teacher at random. Information was collected from the participating teacher and a randomly selected group of pupils during and after the physics les- son. Generally, the interview period lasted not more than 20 minutes. The pupils were interviewed to specifically understand the individual’s own views of what they think their teacher should be doing during the lesson processes. To eliminate researcher and research assistants’ biases, the information from the interviews were reviewed by the researcher and copies given back to the teacher or pupils concerned to confirm the data. This was done in order to increase investigator confidence in the reliability and validity of results [9-11]. The teacher and the randomly selected were inter- viewed on site, generally after the lesson using two in- struments, the Pupil Interview Guide (PIG) and the Teacher Interview Guide (TIG). Throughout the inter- view sessions, the researcher and his assistants were able to collect sufficient descriptive details about the pupils’ views of what they thought their teacher should be doing during the lesson process. The following format illus- trates the style and strategy of the interviews: Pupils were interviewed at random depending on their selected response to the semi-structured interview item (Table 1). Also eight interviewees from each group were asked to elaborate further, why they chose a given choice (s). This was done in order to gain more insight about why they preferred a certain choice (s). In addition, the teacher was also interviewed about his experience with the new technology and role during implementation of the program (Table 2) to see whether his view would differ from those of the pupils. 2.5 Context Three contrasting school sites were used to establish a basis for comparative analysis of qualitative data. A total of 118 pupils were randomly selected and randomly as- signed to three intact classrooms easily accessible by Njoro-Menengai and Nakuru-Marigat roads in Nakuru district, Kenya. The participants consisted of 65 boys and 53 girls. To allay the schools authorities’ confidentiality of their true identification, the three groups-control group I (C1), control group II (C2) and the experimental group (E) were categorized as schools A, B and C. 2.6 Data Analysis Reference [12] has identified three categories of data viz: 1) Baseline data—this refers to the information about the human and technological context of the pupils and their teacher as they interacted with the instructional ma- terials; 2) Process data—which refers to information derived from observations of human-machine interactions in these settings and some of their outcomes; 3) Value data—that refers to information about the values and/or meanings of the teacher and the subjects implied or attributed to the program. The latter category had a major bearing on the data reported in this paper because the data obtained were analyzed in terms of qualitative descriptions. Table 1. Pupils’ interview question What would you say your teacher should do when you are learning the physics course through the computer/new technology? (a) Leave us alone and help us when we need his/her assistance (b) Telling us what we should be doing (c) Demonstrating with the computer (e) Supervising our work (e) Other (Explain) Table 2. Teacher’s interview question What was your experience and what do you say your role should be when teaching the physics course using the new technology? Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE  Pupils’ Perceptions of the Teacher’s Changing Role in E-Learning Physics Classroom Instruction35 3. Results and Discussion The main reason for the study was to explore the pupils’ view of the teacher’s role during instruction. Studies in- dicate that pre-existing pedagogical conceptions are critically important in understanding what teachers do with computers in the classroom milieu. It is gaining more insight of the teacher’s practice and the pupils’ views of that practice and its history that will allow us to understand how teachers utilize information technology (IT) to enhance instruction in the classroom and thereby incorporate them into their instructional culture. Table 3 represents the pupils’ responses to the inter- view item before their exposure to the physics course. The results indicate that the two groups that were pre- tested held similar views about what the role of the teacher should be during classroom instruction. However, this changed remarkably following their exposure to the physics course. But their views on the same had changed dramatically as a result of their exposure to the E-learn- ing program (Table 4). Results in Table 4 below show that the views of the pupils in the E-learning classes expressed unanimity in that 70% and 72% of the pupils in the two experimental groups (E and C2) as compared to only 25% in the true control group who were in agreement that “the teacher should leave them alone and only help whenever a need arises”. In other words, a majority of the pupils in the regular classrooms seem to support the role of a teacher who is in control of the learning process. Similarly, a very low number (17% and 19%) of those in the experi- mental condition (E and C2 respectively) feel that the teacher’s role should be that of telling them what they should do as compared to a large number (83%) of those in the control condition (C1). 3.1 The Pupils’ Views of the Teacher’s Changing Role during the E-Learning Program in Science Instruction Part of the main reasons of this study was to explore the students’ view of the teacher’s role during instruction. The findings reported in the excerpts that follow elabo- rate the students’ own expressions. 3.1.1 Excerpt 1 1) Dan: The teacher should leave us alone and help us when we need him... because through the computer and our own experiences we learn more than just being taught by the teacher. The teacher may only help show us where we go wrong and what to do next after we finish experiments. 2) Rama: The teacher should leave us alone first to practice what we have learnt alone with peers ...this makes us to learn and understand physics lessons better. 3) Owuor: For me, it was fun to use the computer alone with my friends. But I agree that we need the teacher to help us only whenever we mess or are con- fused about something. Table 3. Pupils’ pre-responses to the interview question GROUPS DESCRIPTION OF TEACHER’S ROLE E C1 C 2 1. Leave us alone and help us when we need his/her assistance 20 25 - 2. Telling us what we should be doing 85 83 - 3. Demonstrate when teaching 68 64 - 4. Supervising our work 16 15 - 5. Other (Explain) 12 07 - Table 4. Pupils’ post-responses to the interview question GROUPS DESCRIPTION OF TEACHER’S ROLE E C1 C 2 1. Leave us alone and help us when we need his/her assistance 70 25 72 2. Telling us what we should be doing 17 83 19 3. Demonstrate when teaching 38 64 33 4. Supervising our work 76 15 79 5. Other (Explain) 12 77 09 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE  Pupils’ Perceptions of the Teacher’s Changing Role in E-Learning Physics Classroom Instruction 36 4) Emmy: The teacher should leave us alone of course after teaching us how to use the computer so that we can be free to play with the computer and learn physics les- sons with peers. That is what I think he should do. 5) Rael: The teacher should leave us alone so that we try our own best to use the computer to learn and discuss the physics lessons. 6) David: The teacher should leave us alone because it is for our own benefit to learn and discuss things by our- selves. We will understand them better than if the teacher just tells us. 7) Simon: The teacher should leave us alone because if he explains everything to us... it could be difficult for us to know how to use measuring equipment. 8) Kosi: The teacher should leave us alone I suppose because we should learn... Umm so that we may learn from each other and the computer of course (Group In- terview, School B: C2 Group 11/3/96). 3.1.2 Excerpt 2 1) Malaki: The teacher should leave us alone so that we develop confidence on operating the computer and talk- ing about what we learn in the physics course. 2) Esther: The teacher should not leave us all alone but should be around to help us if we have difficulties in do- ing or solving problems about distance, mass and time. 3) Rotich: The teacher should not leave us alone com- pletely because it will be easy for us to know or follow the lessons all by ourselves… but if he tells us everything it will be difficult to remember because that means all we do is just sit and listen to him and not have time to even think or discuss ideas about the course. 4) Carol: The teacher should not totally leave us alone but help if we are stagnant or having a problem... we like to learn from the computer and peers because we under- stand and remember more… first you must read, talk it over with friends and then apply it through class activi- ties. 5) Bernard: The teacher should not leave us entirely alone but check on us if we are doing things right or wrong. He should be there to clarify where we don’t un- derstand. 6) Jane: The teacher should only tell us where we are wrong and if we are using the right apparatus to measure things. 7) Kimutai: The teacher should be around when we learn with the computer so that he explains complicated things. But after that, he should let us alone and only check to see our progress. 8) Lucy: The teacher should leave us alone so that we can get enough opportunity to learn from the computer and from peers... and not just the teacher alone (Group Interviews, School B: C2 Group 6/3/1996). A comparison of the subjects’ responses reported in Excerpt 1 and 2 reveals identical learning protocols in the treatment groups i.e., E and C2. They all agree that the teacher should leave them alone and only assist when they need help. But the responses of the selected group of subjects in the true control group (C1) shown in Excerpt 3 differ markedly from those by the selected group of subjects in E and C2. While the subjects in the C1 group view learning as teacher dependent, those in the E and C2 group view it as a process that involves the teacher, themselves and the instructional material. The following excerpt clarifies this point further. 3.1.3 Excerpt 3 1) Beggy: The teacher should not leave us alone but tell us what to learn and do. If he leaves us how can one learn without the teacher being present? We will end up making noise and fighting each other. 2) Malel: The teacher should be telling us what to learn and do so that we may know more about physics. We may read our textbooks but it is not like the teacher teaching us. 3) Jiro: If the teacher leaves us alone then we can’t do anything. We need his guidance of course and he should teach us about measurement. 4) Franklin: The teacher should teach us and help us to learn how to measure objects in this course because with- out him we will not know how to use the apparatus. 5) Kyalo: The teacher should tell us what we should learn and do otherwise there will be chaos in the class- room. We don’t know how to learn alone without a teacher. Therefore, he should be there to teach and show us how to measure things. Some students are mean and fight over the apparatus. So we need the teacher to help us out. 6) Kip: The teacher should tell us what to do and learn because he is more knowledgeable than us. He knows everything about measurement and how measuring of objects. 7) Nancy: The teacher should tell us more about meas- urement and give us more time to practice what he has taught rather than just telling and showing how to meas- ure. We should measure things and not just sit and be told how. 8) Chebet: The teacher should not leave us alone but should show us what we should do because he is our guardian and he knows more about physics than us. He should give us that knowledge so that we know how to measure or use measurement tools during the lesson (Group Interviews, School A: C1 Group 5/3/96). 3.2 Teachers’ Own Expressions and Experience with the E-Learning Program The teacher illustrated his own expression about his first experience with having to use the ELP in a real physics laboratory classroom depicted in Excerpt 4. Although the teacher felt change was desirable, the process was grad- Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE  Pupils’ Perceptions of the Teacher’s Changing Role in E-Learning Physics Classroom Instruction37 ual process. Once he had internalized the process, he seemed ready for it. Excerpt 4 depicts the process quite succinctly: 3.2.1 Excerpt 4 1) Teacher 1: My first experience with the use of com- puter was very chaotic. But now I know how to handle the whole situation. I did not know how then but I am just a little worried. 2) Researcher: Worried about your role? 3) Teacher: Yes. Imagine all along I had full control of the class and now it is just brief. Anyway I just have to learn to let go of the fear if I must make full use of the computer. This might not be easy though but it is some- thing that I must try harder (School C: E Group 20/2/96). An examination of Excerpt 4 seems to suggest the teacher’s awareness of the need for a paradigm shift in his role during instructional practice. This emerged due to the realization that his role had to change from that of “full control” to that of “improving and fostering recip- rocal relationship” between him and his students. This is quite apparent from the teacher’s own expression of a willingness to abandon his previous approach that en- couraged full control in order to embrace the new method, which he reckoned is not easy but as something that he must try harder. But the anecdote given in Excerpt 5 is a good illustration of how the use of computer changed the role of another teacher completely. This teacher revealed that he is no longer worried about his role being threat- ened by the computer use instead, he pointed out that he has realized its benefits in terms of the time saved and his ability to do what he has not been able to do with an ex- pository approach. 3.2.2 Excerpt 5 Teacher 2: My biggest benefit for using the e-learning to teach the course of measurement is the time saved. With this I have been able to help weaker students and to su- pervise students’ work. This is something I have not been able to do in my previous lessons (School C: E Group 14/3/96). This finding is supported by an earlier claim that al- though most teachers tend to resist change, but they nev- ertheless as a result of some impasse they feel they have reached in their teaching may gravitate out of necessity towards change [13]. 4. Conclusions Most views of pupils in ELP classes have all pointed to the learners’ need for mutual interaction during the learning process. The portrayal of these qualitative data about the teacher’s role seem mixed but agree on one important fact underscored earlier i.e., the teacher as the key factor in the classroom. The pupils in the ELP treat- ment seem to all agree that in as much as the teacher should leave them alone, they nonetheless concur also that the teacher should be present to assist them in time of need. But the views of the students in the true control group seem to suggest a total reliance on the teacher as the guide and knowledge dispenser. Numerous studies have also found similar results [14-20]. On the overall, the relative effectiveness of the E- Learning program in promoting collaborative learning may form part of the solution to the emergence of large classes in the context of inadequate human and material resources. This finding indicates that e-learning system has the potential for encouraging pupil participation in science lessons and practical activities [5,19,21,22]. Also, there is evidence of instances where the use of the pro- gram provided the teacher more leeway to attend to indi- vidual pupils needs and to supervise their work. In addi- tion, there is overriding evidence that the idea of operat- ing the e-learning program gave them the impression of well-attested strategy of learning by doing. However, this impression and the findings reported need further cor- roboration by future studies. REFERENCES [1] S. M. Allessi and S. R. Trollip, “Computer Based Instruc- tion: Methods and Development,” 2nd Edition, Engle- wood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall, NJ, 1991. [2] R. E. Clark, “Media will Never Influence Learning,” Educational Technology Research and Development, Vol. 42, No. 2, 1994, pp. 21-29. [3] M. J. Gavora and M. Hannafin, “Perspectives on the De- sign of Human-Computer Interactions: Issues and Impli- cations,” Instructional Science, Vol. 22, No. 6, 1995, pp. 445-447. [4] T. C. Reeves, “A Model of the Effective Dimensions of Interactive Learning,” In: P. M. Alexander, Ed., Com- puter-Assisted Education Training in Developing Coun- tries, University of South Africa, Pretoria, 1995, pp. 221-227. [5] J. K. Kiboss, “An Evaluation of Teacher/Student Verbal and Non-Verbal Behaviors in Computer-Augmented Physics Laboratory Classrooms in Kenya,” Journal of Information Technology and Teacher Education, Vol. 9, No. 3, 2000, pp. 199-213. [6] R. L. Blomeyer, “Microcomputers in Foreign Language Teaching: A Case Study on Computer Aided Learning,” In: R. L. Blomeyer and C. D. Martin, Eds., Case Studies in Computer Aided Learning, The Falmer Press, London, 1991, pp. 115-149. [7] C. D. Martin, “Stakeholder Perspectives on Implementa- tion of Micros in a School District,” In: R. L. Blomeyer and C. D. Martin, Eds., Case Studies in Computer-Aided Learning, The Falmer Press, London, 1991, pp. 169-221. [8] D. Neuman, “Opportunities for Research on Organization Impact of School Computers,” Education Researcher, Vol. 19, No. 3, 1990, pp. 8-13. [9] M. B. Miles and A. M. Huberman, “Qualitative Data Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE  Pupils’ Perceptions of the Teacher’s Changing Role in E-Learning Physics Classroom Instruction Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE 38 Analysis,” Sage, London, 1984. [10] D. Neuman, “Naturalistic Inquiry and Computer-Based Instruction: Rationale, Procedures, and Potential,” Educa- tional Technology Research and Development, Vol. 37, No. 3, 1989, pp. 39-51. [11] M. Q. Patton, “Qualitative Evaluation Methods,” Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, CA, 1991. [12] M. D. Lecompte and J. Goetz, “Multiple Case Study,” In: D. M. Fetterman, Ed., Ethnography in Educational Evaluation, Sage Publications, Beverly Hills CA, 1984, pp. 37-59. [13] D. Lortie, “School Teacher: A Sociological Study,” Uni- versity of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1975. [14] P. Freirie, “The Pedagogy of the Oppressed,” Continuum, New York, 1970. [15] P. Freirie, “Education for Social Consciousness,” Con- tinuum, New York, 1973. [16] O. J. Jegede and P. A. Okebukola, “Differences in So- ciocultural Environment Perceptions Associated with Gender in Science Classrooms,” Journal of Research in Science Teaching, Vol. 29, No. 7, 1992, pp. 637-647. [17] A. L. Montoya, “Perceptions of School Climate and Stu- dent Achievement in Middle and Elementary School,” Kutztown University of Pennsylvania, ERIC ED 324111, 1990. [18] H. A. Robinson, “The Ethnography of Empowerment: The Transformative Power of Classroom Interaction,” The Palmer Press, Bristol, 1994. [19] M. Ndirangu, J. K. Kiboss and E. Wekesa, “Reflections from a Computer Simulations Program on Cell Division in Selected Kenyan Secondary Schools,” The Science Education Review, Vol. 4, No. 4, 2005, pp. 117-124. [20] E. K. Tanui, J. K. Kiboss, A. A. Walaba and D. Nassiuma, “Teachers’ Changing Roles in Computer Assisted Roles in Kenyan Secondary Schools,” Educational Research and Review, Vol. 3, No. 8, 2008, pp. 280-285. [21] G. Underwood and J. D. M. Underwood, “Computers and Learning: Helping Children Acquire Thinking Skills,” Blackwell, Cambridge, 1994. [22] D. Williams, L. Coles, A. Richardson, K. Wilson and J. Tuson, “Integrating Information and Communications Technology in Professional Practice: An Analysis of Teachers’ Needs Based on a Survey of Primary and Sec- ondary Teachers in Scottish Schools,” Journal of Infor- mation Technology and Teacher Education, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2000, pp. 167-182. |