Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

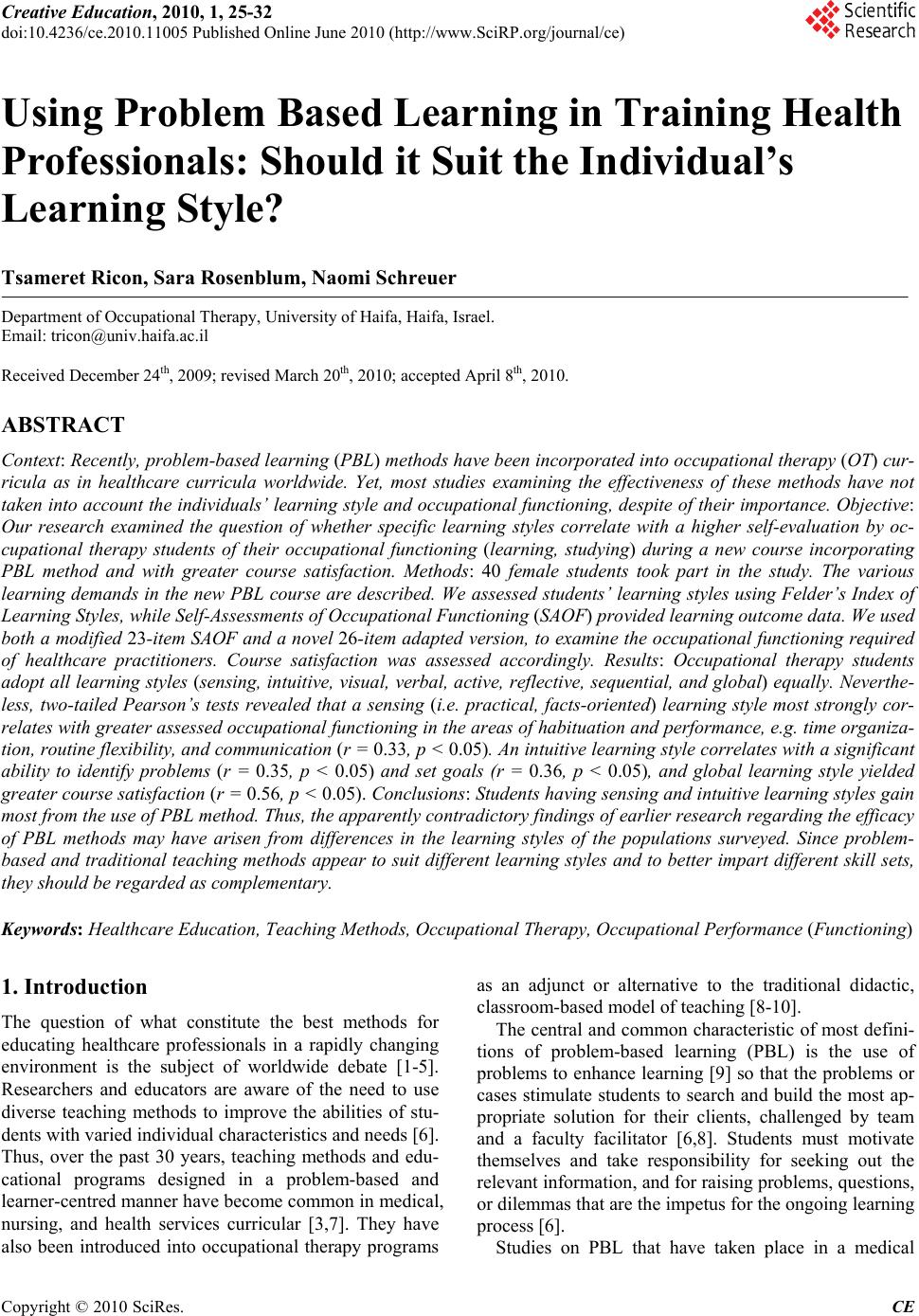

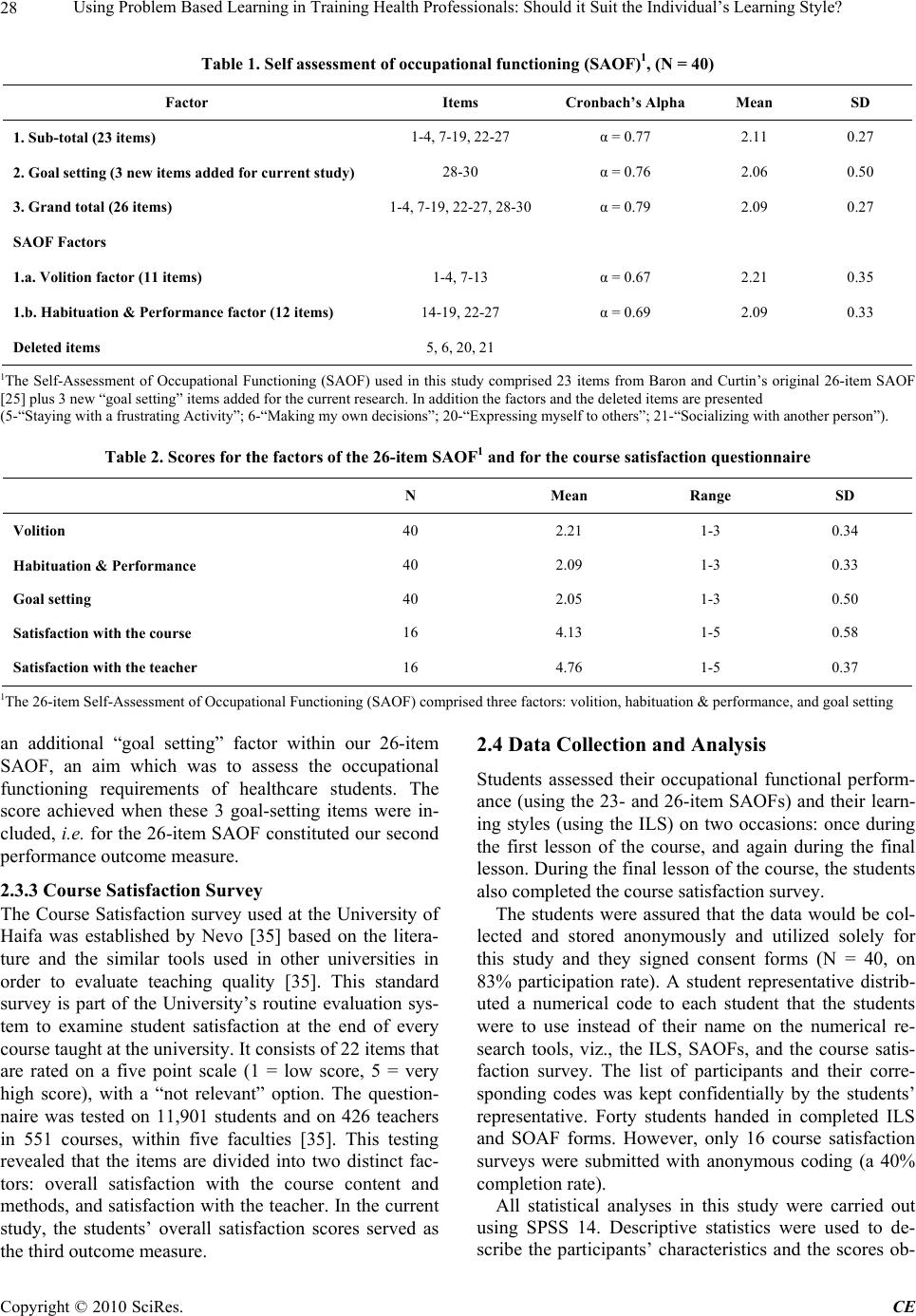

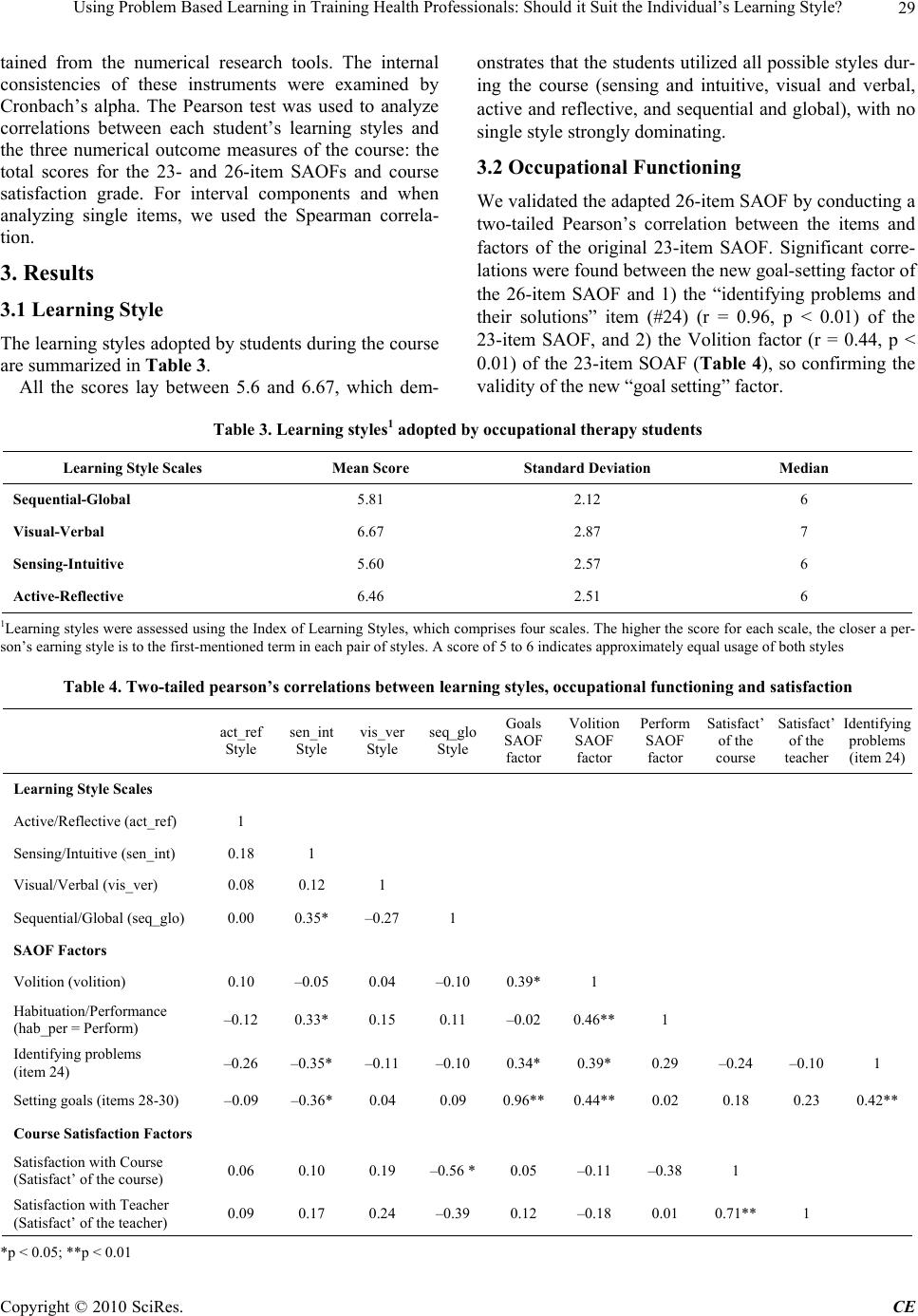

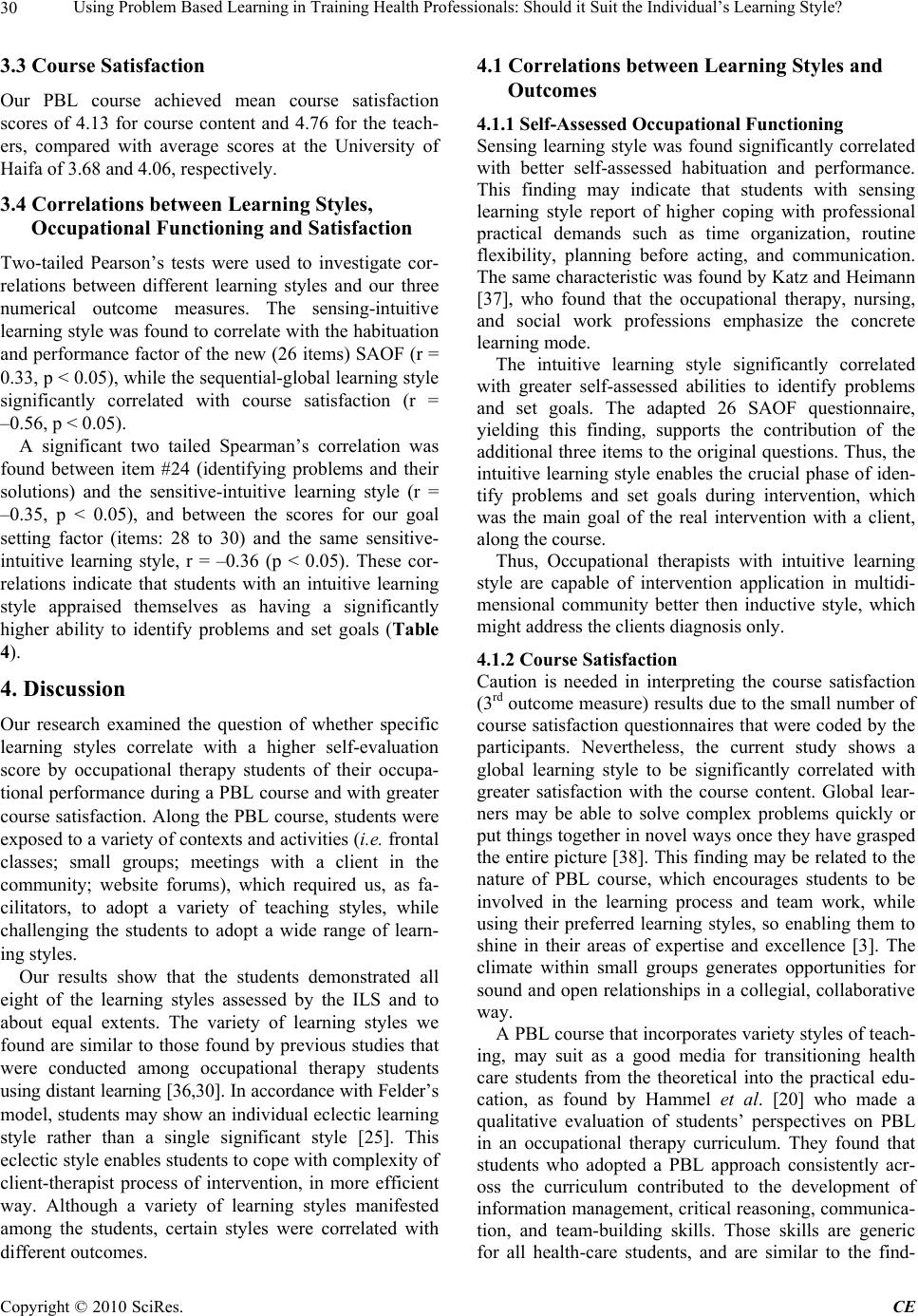

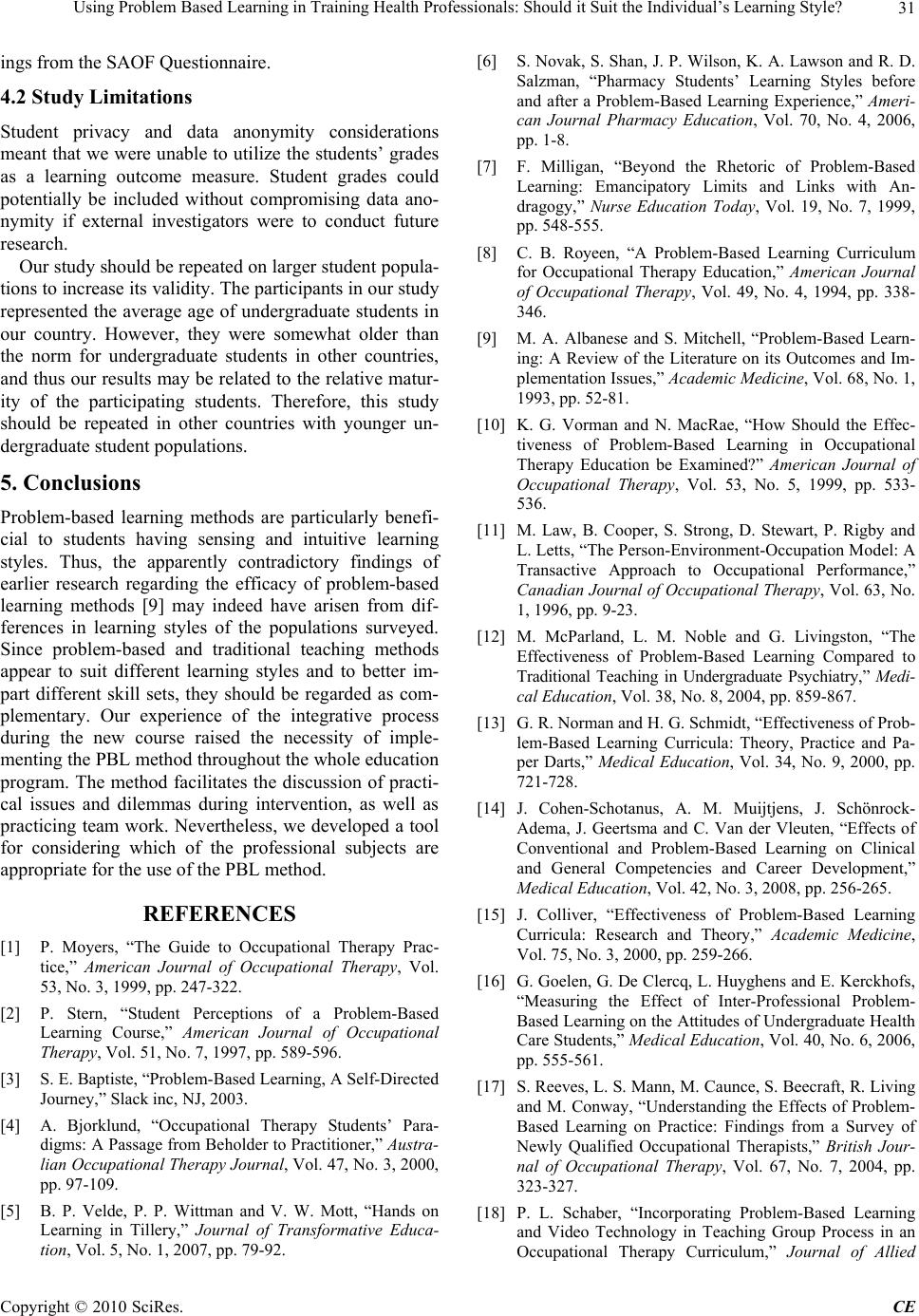

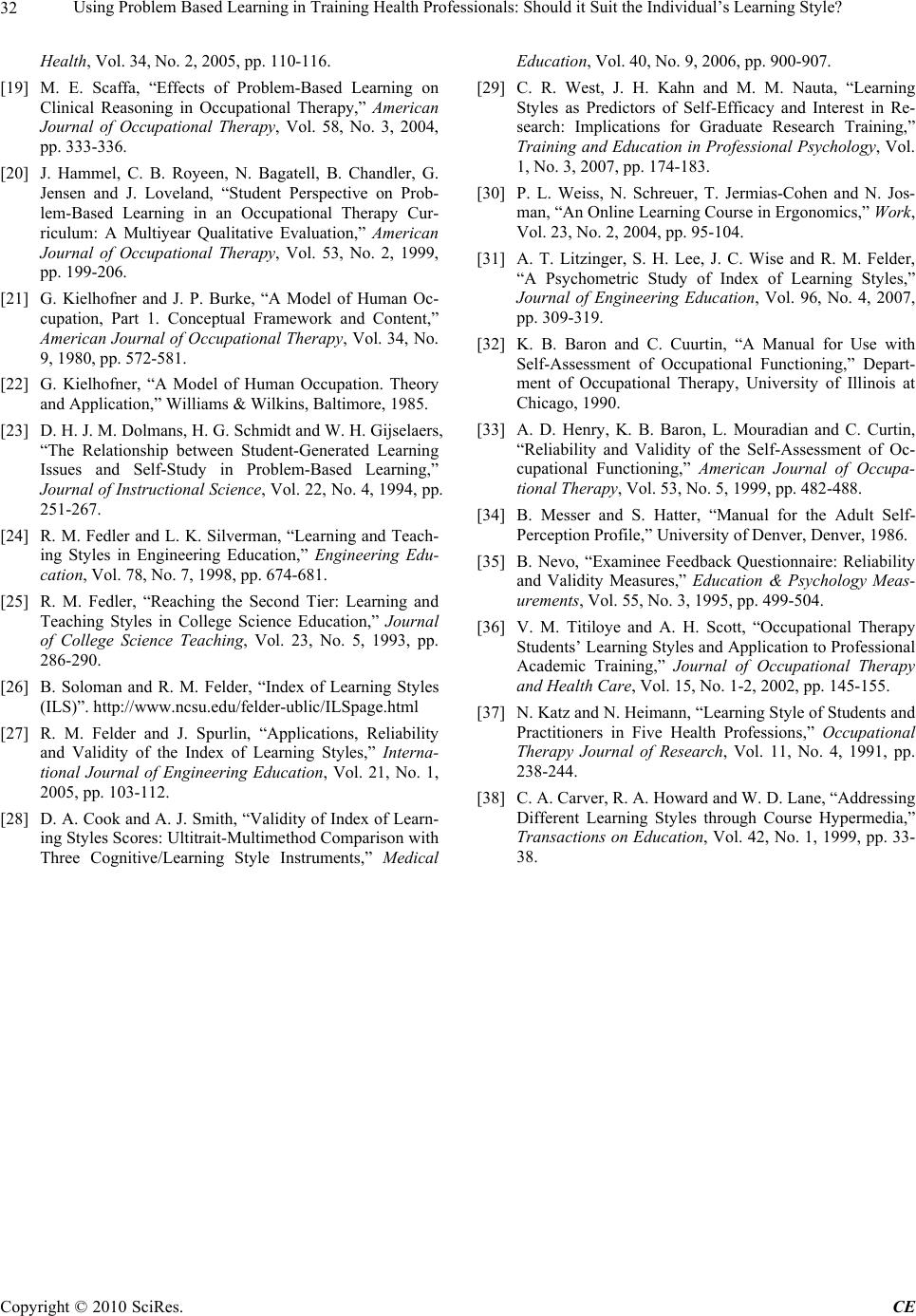

Creative Education, 2010, 1, 25-32 doi:10.4236/ce.2010.11005 Published Online June 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE 25 Using Problem Based Learning in Training Health Professionals: Should it Suit the Individual’s Learning Style? Tsameret Ricon, Sara Rosenblum, Naomi Schreuer Department of Occupational Therapy, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel. Email: tricon@univ.haifa.ac.il Received December 24th, 2009; revised March 20th, 2010; accepted April 8th, 2010. ABSTRACT Context: Recently, problem-based learning (PBL) methods have been incorporated into occupational therapy (OT) cur- ricula as in healthcare curricula worldwide. Yet, most studies examining the effectiveness of these methods have not taken into account the individuals’ learning style and occupational functioning, despite of their importance. Objective: Our research examined the question of whether specific learning styles correlate with a higher self-evaluation by oc- cupational therapy students of their occupational functioning (learning, studying) during a new course incorporating PBL method and with greater course satisfaction. Methods: 40 female students took part in the study. The various learning demands in the new PBL course are described. We assessed students’ learning styles using Felder’s Index of Learning Styles, while Self-Assessments of Occupational Functioning (SAOF) provided learning outcome data. We used both a modified 23-item SAOF and a novel 26-item adapted version, to examine the occupational functioning required of healthcare practitioners. Course satisfaction was assessed accordingly. Results: Occupational therapy students adopt all learning styles (sensing, intuitive, visual, verbal, active, reflective, sequential, and global) equally. Neverthe- less, two-tailed Pearson’s tests revealed that a sensing (i.e. practical, facts-oriented) learning style most strongly cor- relates with greater assessed occupational functioning in the areas of habituation and performance, e.g. time organiza- tion, routine flexibility, and communication (r = 0.33, p < 0.05). An intuitive learning style correlates with a significant ability to identify problems (r = 0.35, p < 0.05) and set goals (r = 0.36, p < 0.05), and global learning style yielded greater course satisfaction (r = 0.56, p < 0.05). Conclusions: Students having sensing and intuitive learning styles gain most from the use of PBL method. Thus, the apparently contradictory findings of earlier research regarding the efficacy of PBL methods may have arisen from differences in the learning styles of the populations surveyed. Since problem- based and traditional teaching methods appear to suit different learning styles and to better impart different skill sets, they should be regarded as complementary. Keywords: Healthcare Education, Teaching Methods, Occupational Therapy, Occupational Performance (Functioning) 1. Introduction The question of what constitute the best methods for educating healthcare professionals in a rapidly changing environment is the subject of worldwide debate [1-5]. Researchers and educators are aware of the need to use diverse teaching methods to improve the abilities of stu- dents with varied individual characteristics and needs [6]. Thus, over the past 30 years, teaching methods and edu- cational programs designed in a problem-based and learner-centred manner have become common in medical, nursing, and health services curricular [3,7]. They have also been introduced into occupational therapy programs as an adjunct or alternative to the traditional didactic, classroom-based model of teaching [8-10]. The central and common characteristic of most defini- tions of problem-based learning (PBL) is the use of problems to enhance learning [9] so that the problems or cases stimulate students to search and build the most ap- propriate solution for their clients, challenged by team and a faculty facilitator [6,8]. Students must motivate themselves and take responsibility for seeking out the relevant information, and for raising problems, questions, or dilemmas that are the impetus for the ongoing learning process [6]. Studies on PBL that have taken place in a medical  Using Problem Based Learning in Training Health Professionals: Should it Suit the Individual’s Learning Style? 26 teaching context; have focused mainly on its effective- ness in comparison to the conventional teaching method in terms of: the academic performance of the learner [11-13], self-rated competencies, academic and clinical outcomes [14]. Although students generally prefer PBL methods over conventional instruction [9], numerous studies have yielded contradictory results in terms of the academic and clinical proficiency of students taught us- ing problem-based learning methods compared to tradi- tional didactic teaching [9,12,15,16]. The use of PBL in the occupational therapy context has yielded similarly inconclusive results. Thus, Reeves and his colleagues [17] found that, although a majority of newly qualified occupational therapists indicated that PBL equipped them well for their upcoming clinical practice, some graduates were more sceptical and viewed PBL as having a limited effect on their problem solving abilities, clinical knowledge, and skills. Other studies have focused on students’ subjective evaluations of im- provement in various areas, such as group skills [18] and clinical reasoning [19], as a consequence of problem- based learning demonstrating variability in the benefits ascribed to the PBL method [20]. The current study hypothesis was based on two main theoretic models: The Model of Human Occupation [21, 22] and Felder and Silverman’s model of learning styles [23,24]. Students’ learning styles were assessed according to the Felder and Silverman model [24,25]. According to Felder, a learning style reflects the individual’s charac- teristics, strengths and preferences in the ways he or she processes information [26]. Learning styles vary from one individual to another. They indicate a person’s predi- lections on five continua: sensing/intuitive, visual/verbal, inductive/deductive, active/reflective, and sequential/global, which are formalized into the Index of Learning Styles [24]. The Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) [21] was borrowed to examine the student as a person/individual performing a learning occupation. The MOHO describes three interrelated human characteristics relative to occu- pational functioning: volition (motivation, decision), ha- bituation (behavioural patterns and routines), and per- formance capacity (the physical cognitive and mental abilities). The MOHO provides the theoretical back- ground [21], to the Self Assessment of Occupational Functioning which has being used in the current study as a means to self evaluate the students’ strengths and weaknesses relative to their occupational functioning as learners in the new course. Thus, the question arises as to whether problem-based learning is suited only to individuals with certain learn- ing styles. Yet, the issue of the effectiveness of PBL for students exhibiting different learning styles has not been the focus of research to date. Consequently, we posed the following research question: Do certain learning styles correlate with OT students’ higher self-evaluation of performance and greater course satisfaction, during a new course aiming to prepare them for the transition from theory to practice, using problem- based learning method? 2. Methods 2.1 Participants All third year students studying for a Bachelor’s degree in occupational therapy in the University of Haifa during the 2004-2005 academic year chose to enrol in a new problem-based learning course and agreed to participate anonymously in this study. All students [48] were female, 43 (90%) were non-immigrant students while 5 (10%) were immigrants; 5 (10%) were single, and 29 (60%) had an urban background. Mean student age was 25.3 years, with a standard deviation of 1.5 years, which is repre- sentative of the local national undergraduate student population. Forty students (83.33%) signed the consent form and participated anonymously in the study. 2.2 The “Intervention along the Life Span” Course The constant independent variable for all students in this study was their participation in a new course called “In- tervention along the Life Span”, which was established using PBL principles. Three experienced occupational therapy teachers con- ducted the course, which ran for 12 intensive weeks and comprised of three parallel processes: The first process was three introductory lessons for the whole class (N = 48); the second was an on-going class-work performed in groups (N = 16) and teams (N = 4) whose purpose was interactive learning process with feedback provided by the peers; and the third was individual weekly meetings between each student and her client in the community. The final lesson (12th) served for, integrating the different processes into a whole intervention experience. From the fourth lesson on and parallel to the class-based learning, the students began to meet their clients in the community. Over the course of several meetings, each student was required to set an occupational goal and objectives with her client and apply a short term intervention. This major goal was accompanied by problem based methods and multi-interactions, supported by the teacher and the peers, along with: gather information in terms of the client’s occupational performance and environment; search the literature for further knowledge about the client’s needs and theoretical frameworks; discuss treatment barriers and facilitators with the client; and develop options for a subsequent short-term intervention. These aspects of the course design aimed at avoiding a common weak-point of PBL courses, which struggle to generate appropriate Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE  Using Problem Based Learning in Training Health Professionals: Should it Suit the Individual’s Learning Style?27 real problems upon which to base the learning (i.e. using written case studies). The approach we adopted ensured the natural creation of sub-goals and required students to seek a wide-range of information. The on going counsel- ling and team supervision ensured a constructive process, accompanied by variety of media, including videos, presentations, a course web-site, and role simulations [23]. The students were also required to document the entire process in a diary, to present their client to their team along each stage of the intervention plan, and to relate to feedback from their teams. The role of the course tutors was to facilitate independent learning (i.e. to facilitate group discussions, point out dilemmas, suggest new thinking directions and reflect personal progression or obstructions). At the end of the course, each student pre- sented the process she had undertaken with the client to her 16-student group and submitted a comprehensive written assignment to her tutor. A variety of media were used in all course contexts, including videos, presenta- tions, a course web-site, and role simulations. 2.3 Research Tools 2.3.1 The Index of Learning Styles (ILS) Students’ learning styles were assessed according to the Felder and Silverman model [24,25]. The Index of Learning Styles [ILS; 24,26,27] consists of four scales. Each scale comprises 11 items and, for each item, the learner is asked to choose between two dichotomous learning styles that suit him/her in various situations: sensing (concrete, practical, oriented towards facts) or intuitive (conceptual, innovative, oriented towards theo- ries); visual (prefers visual representations of presented materials) or ver ba l (prefers written or spoken explana- tions); active (learns by trying things out) or reflective (learns by thinking things through); and sequential (adopts a linear thinking process, proceeds in incremental steps) or global (adopts holistic thinking, progresses in large leaps) [27]. The higher the value of the score in each of the four scales, the closer a person is to the first-mentioned term in each pair of styles. The validity and reliability of this index has been ex- tensively examined among many diverse student popula- tions, including those surveyed in this research [27-30]. An acceptable alpha Chronbach value was found for the Sensing-Intuitive and Visual-Verbal scales ( = 0.70), while lower alpha values were found for the Active-Re- flective ( = 0.60) and Sequential-Global ( = 0.56) scales [27]. However, differences were found between genders and between engineering compared to liberal arts and education students by two-way ANOVA, using post-hoc tests for each of the four scales [27]. As a result, three problematic items (#30, #40 and #42) were ex- cluded from the revised 41-item version of the ILS [31] that we used for this research. The students’ scores on each of the four sub-scales constituted the learning styles variable for the current study. Internal reliability was confirmed by factor analy- sis, which yielded a strong Cronbach’s alpha for the 41 item ILS ( = 0.85). 2.3.2 Self Assessment of Occupational Functioning (SAOF) The original purpose of the adult version of the revised Self Assessment of Occupational Functioning [SAOF; 32, 33] was to provide a tool for collaborative client-centered goal setting facilitated by the occupational therapist. The assessment enables individuals to evaluate their per- formance on 27 items in a framework that helps to iden- tify challenges to performing desired roles, prior to the clinical goal-setting process. In the assessment, the sub- ject (14 to 85 years old) is asked to grade his/her per- formance in each item on a three point performance scale: “strong” (3), “adequate” (2), or “requires improvement” (1). Henry et al. [33] adapted the tool for use in assessing the occupational performance of students as learners. The student-adapted SAOF has been established as a reliable and useful tool for self evaluation by students of their performance [33,34]. We therefore used the student-adapted SAOF [33] to collect data from our students regarding their perform- ance in the new problem-based learning course. Four items were deleted from the SAOF questionnaire ( #5, #6, #20, and #21; see Table 1), due to low variance and missing data. The 23 remaining items showed a signifi- cant division into two primary factors, as confirmed by Cronbach’s alpha, namely: Volition and a united Ha- bituation & Performance factor (Table 1). No significant effects were found for the original single-item Environ- ment factor, which is consistent with the findings Henry et al. [33], and we therefore omitted it from further analysis. This analysis, confirms the basic structure of the 23-item SAOF questionnaire, its content validity, and its relevance to our study. The total score on the 23-item SAOF constituted the first performance outcome meas- ure for this study. The healthcare sector places particular emphasis on students’ abilities to define operative goals for clients and for themselves, and this was certainly a strong theme in our new course. Yet goal-setting abilities do not fea- ture strongly in the 23-item SOAF, which includes only one question within this issue (item #24; identifying problems and their solutions). We therefore added three items to the 23-item SAOF: “setting goals suitable for the client” (item 28), “Implementing client’s goals” (item 29), and “applying my own goals” (item 30) (Table 2). Chronbach’s alpha confirmed that these 3 items formed Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE  Using Problem Based Learning in Training Health Professionals: Should it Suit the Individual’s Learning Style? Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE 28 Table 1. Self assessment of occupational functioning (SAOF)1, (N = 40) Factor Items Cronbach’s Alpha Mean SD 1. Sub-total (23 items) 1-4, 7-19, 22-27 α = 0.77 2.11 0.27 2. Goal setting (3 new items added for current study) 28-30 α = 0.76 2.06 0.50 3. Grand total (26 items) 1-4, 7-19, 22-27, 28-30 α = 0.79 2.09 0.27 SAOF Factors 1.a. Volition factor (11 items) 1-4, 7-13 α = 0.67 2.21 0.35 1.b. Habituation & Performance factor (12 items) 14-19, 22-27 α = 0.69 2.09 0.33 Deleted items 5, 6, 20, 21 1The Self-Assessment of Occupational Functioning (SAOF) used in this study comprised 23 items from Baron and Curtin’s original 26-item SAOF [25] plus 3 new “goal setting” items added for the current research. In addition the factors and the deleted items are presented (5-“Staying with a frustrating Activity”; 6-“Making my own decisions”; 20-“Expressing myself to others”; 21-“Socializing with another person”). Table 2. Scores for the factors of the 26-item SAOF1 and for the course satisfaction questionnaire N Mean Range SD Volition 40 2.21 1-3 0.34 Habituation & Performance 40 2.09 1-3 0.33 Goal setting 40 2.05 1-3 0.50 Satisfaction with the course 16 4.13 1-5 0.58 Satisfaction with the teacher 16 4.76 1-5 0.37 1The 26-item Self-Assessment of Occupational Functioning (SAOF) comprised three factors: volition, habituation & performance, and goal setting an additional “goal setting” factor within our 26-item SAOF, an aim which was to assess the occupational functioning requirements of healthcare students. The score achieved when these 3 goal-setting items were in- cluded, i.e. for the 26-item SAOF constituted our second performance outcome measure. 2.3.3 Course Satisfaction Survey The Course Satisfaction survey used at the University of Haifa was established by Nevo [35] based on the litera- ture and the similar tools used in other universities in order to evaluate teaching quality [35]. This standard survey is part of the University’s routine evaluation sys- tem to examine student satisfaction at the end of every course taught at the university. It consists of 22 items that are rated on a five point scale (1 = low score, 5 = very high score), with a “not relevant” option. The question- naire was tested on 11,901 students and on 426 teachers in 551 courses, within five faculties [35]. This testing revealed that the items are divided into two distinct fac- tors: overall satisfaction with the course content and methods, and satisfaction with the teacher. In the current study, the students’ overall satisfaction scores served as the third outcome measure. 2.4 Data Collection and Analysis Students assessed their occupational functional perform- ance (using the 23- and 26-item SAOFs) and their learn- ing styles (using the ILS) on two occasions: once during the first lesson of the course, and again during the final lesson. During the final lesson of the course, the students also completed the course satisfaction survey. The students were assured that the data would be col- lected and stored anonymously and utilized solely for this study and they signed consent forms (N = 40, on 83% participation rate). A student representative distrib- uted a numerical code to each student that the students were to use instead of their name on the numerical re- search tools, viz., the ILS, SAOFs, and the course satis- faction survey. The list of participants and their corre- sponding codes was kept confidentially by the students’ representative. Forty students handed in completed ILS and SOAF forms. However, only 16 course satisfaction surveys were submitted with anonymous coding (a 40% completion rate). All statistical analyses in this study were carried out using SPSS 14. Descriptive statistics were used to de- scribe the participants’ characteristics and the scores ob-  Using Problem Based Learning in Training Health Professionals: Should it Suit the Individual’s Learning Style?29 tained from the numerical research tools. The internal consistencies of these instruments were examined by Cronbach’s alpha. The Pearson test was used to analyze correlations between each student’s learning styles and the three numerical outcome measures of the course: the total scores for the 23- and 26-item SAOFs and course satisfaction grade. For interval components and when analyzing single items, we used the Spearman correla- tion. 3. Results 3.1 Learning Style The learning styles adopted by students during the course are summarized in Table 3. All the scores lay between 5.6 and 6.67, which dem- onstrates that the students utilized all possible styles dur- ing the course (sensing and intuitive, visual and verbal, active and reflective, and sequential and global), with no single style strongly dominating. 3.2 Occupational Functioning We validated the adapted 26-item SAOF by conducting a two-tailed Pearson’s correlation between the items and factors of the original 23-item SAOF. Significant corre- lations were found between the new goal-setting factor of the 26-item SAOF and 1) the “identifying problems and their solutions” item (#24) (r = 0.96, p < 0.01) of the 23-item SAOF, and 2) the Volition factor (r = 0.44, p < 0.01) of the 23-item SOAF (Table 4), so confirming the validity of the new “goal setting” factor. Table 3. Learning styles1 adopted by occupational therapy students Learning Style Scales Mean Score Standard Deviation Median Sequential-Global 5.81 2.12 6 Visual-Verbal 6.67 2.87 7 Sensing-Intuitive 5.60 2.57 6 Active-Reflective 6.46 2.51 6 1Learning styles were assessed using the Index of Learning Styles, which comprises four scales. The higher the score for each scale, the closer a per- son’s earning style is to the first-mentioned term in each pair of styles. A score of 5 to 6 indicates approximately equal usage of both styles Table 4. Two-tailed pearson’s correlations between learning styles, occupational functioning and satisfaction act_ref Style sen_int Style vis_ver Style seq_glo Style Goals SAOF factor Volition SAOF factor Perform SAOF factor Satisfact’ of the course Satisfact’ of the teacher Identifying problems (item 24) Learning Style Scales Active/Reflective (act_ref) 1 Sensing/Intuitive (sen_int) 0.18 1 Visual/Verbal (vis_ver) 0.08 0.12 1 Sequential/Global (seq_glo) 0.00 0.35* –0.27 1 SAOF Factors Volition (volition) 0.10 –0.05 0.04 –0.10 0.39* 1 Habituation/Performance (hab_per = Perform) –0.12 0.33* 0.15 0.11 –0.02 0.46**1 Identifying problems (item 24) –0.26 –0.35* –0.11 –0.10 0.34* 0.39* 0.29 –0.24 –0.10 1 Setting goals (items 28-30) –0.09 –0.36* 0.04 0.09 0.96**0.44**0.02 0.18 0.23 0.42** Course Satisfaction Factors Satisfaction with Course (Satisfact’ of the course) 0.06 0.10 0.19 –0.56 *0.05 –0.11 –0.38 1 Satisfaction with Teacher (Satisfact’ of the teacher) 0.09 0.17 0.24 –0.39 0.12 –0.18 0.01 0.71** 1 * p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE  Using Problem Based Learning in Training Health Professionals: Should it Suit the Individual’s Learning Style? 30 3.3 Course Satisfaction Our PBL course achieved mean course satisfaction scores of 4.13 for course content and 4.76 for the teach- ers, compared with average scores at the University of Haifa of 3.68 and 4.06, respectively. 3.4 Correlations between Learning Styles, Occupational Functioning and Satisfaction Two-tailed Pearson’s tests were used to investigate cor- relations between different learning styles and our three numerical outcome measures. The sensing-intuitive learning style was found to correlate with the habituation and performance factor of the new (26 items) SAOF (r = 0.33, p < 0.05), while the sequential-global learning style significantly correlated with course satisfaction (r = –0.56, p < 0.05). A significant two tailed Spearman’s correlation was found between item #24 (identifying problems and their solutions) and the sensitive-intuitive learning style (r = –0.35, p < 0.05), and between the scores for our goal setting factor (items: 28 to 30) and the same sensitive- intuitive learning style, r = –0.36 (p < 0.05). These cor- relations indicate that students with an intuitive learning style appraised themselves as having a significantly higher ability to identify problems and set goals (Table 4). 4. Discussion Our research examined the question of whether specific learning styles correlate with a higher self-evaluation score by occupational therapy students of their occupa- tional performance during a PBL course and with greater course satisfaction. Along the PBL course, students were exposed to a variety of contexts and activities (i.e. frontal classes; small groups; meetings with a client in the community; website forums), which required us, as fa- cilitators, to adopt a variety of teaching styles, while challenging the students to adopt a wide range of learn- ing styles. Our results show that the students demonstrated all eight of the learning styles assessed by the ILS and to about equal extents. The variety of learning styles we found are similar to those found by previous studies that were conducted among occupational therapy students using distant learning [36,30]. In accordance with Felder’s model, students may show an individual eclectic learning style rather than a single significant style [25]. This eclectic style enables students to cope with complexity of client-therapist process of intervention, in more efficient way. Although a variety of learning styles manifested among the students, certain styles were correlated with different outcomes. 4.1 Correlations between Learning Styles and Outcomes 4.1.1 Self-Assessed Occupational Functioning Sensing learning style was found significantly correlated with better self-assessed habituation and performance. This finding may indicate that students with sensing learning style report of higher coping with professional practical demands such as time organization, routine flexibility, planning before acting, and communication. The same characteristic was found by Katz and Heimann [37], who found that the occupational therapy, nursing, and social work professions emphasize the concrete learning mode. The intuitive learning style significantly correlated with greater self-assessed abilities to identify problems and set goals. The adapted 26 SAOF questionnaire, yielding this finding, supports the contribution of the additional three items to the original questions. Thus, the intuitive learning style enables the crucial phase of iden- tify problems and set goals during intervention, which was the main goal of the real intervention with a client, along the course. Thus, Occupational therapists with intuitive learning style are capable of intervention application in multidi- mensional community better then inductive style, which might address the clients diagnosis only. 4.1.2 Course Satisfaction Caution is needed in interpreting the course satisfaction (3rd outcome measure) results due to the small number of course satisfaction questionnaires that were coded by the participants. Nevertheless, the current study shows a global learning style to be significantly correlated with greater satisfaction with the course content. Global lear- ners may be able to solve complex problems quickly or put things together in novel ways once they have grasped the entire picture [38]. This finding may be related to the nature of PBL course, which encourages students to be involved in the learning process and team work, while using their preferred learning styles, so enabling them to shine in their areas of expertise and excellence [3]. The climate within small groups generates opportunities for sound and open relationships in a collegial, collaborative way. A PBL course that incorporates variety styles of teach- ing, may suit as a good media for transitioning health care students from the theoretical into the practical edu- cation, as found by Hammel et al. [20] who made a qualitative evaluation of students’ perspectives on PBL in an occupational therapy curriculum. They found that students who adopted a PBL approach consistently acr- oss the curriculum contributed to the development of information management, critical reasoning, communica- tion, and team-building skills. Those skills are generic for all health-care students, and are similar to the find- Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE  Using Problem Based Learning in Training Health Professionals: Should it Suit the Individual’s Learning Style?31 ings from the SAOF Questionnaire. 4.2 Study Limitations Student privacy and data anonymity considerations meant that we were unable to utilize the students’ grades as a learning outcome measure. Student grades could potentially be included without compromising data ano- nymity if external investigators were to conduct future research. Our study should be repeated on larger student popula- tions to increase its validity. The participants in our study represented the average age of undergraduate students in our country. However, they were somewhat older than the norm for undergraduate students in other countries, and thus our results may be related to the relative matur- ity of the participating students. Therefore, this study should be repeated in other countries with younger un- dergraduate student populations. 5. Conclusions Problem-based learning methods are particularly benefi- cial to students having sensing and intuitive learning styles. Thus, the apparently contradictory findings of earlier research regarding the efficacy of problem-based learning methods [9] may indeed have arisen from dif- ferences in learning styles of the populations surveyed. Since problem-based and traditional teaching methods appear to suit different learning styles and to better im- part different skill sets, they should be regarded as com- plementary. Our experience of the integrative process during the new course raised the necessity of imple- menting the PBL method throughout the whole education program. The method facilitates the discussion of practi- cal issues and dilemmas during intervention, as well as practicing team work. Nevertheless, we developed a tool for considering which of the professional subjects are appropriate for the use of the PBL method. REFERENCES [1] P. Moyers, “The Guide to Occupational Therapy Prac- tice,” American Journal of Occupational Therapy, Vol. 53, No. 3, 1999, pp. 247-322. [2] P. Stern, “Student Perceptions of a Problem-Based Learning Course,” American Journal of Occupational Therapy, Vol. 51, No. 7, 1997, pp. 589-596. [3] S. E. Baptiste, “Problem-Based Learning, A Self-Directed Journey,” Slack inc, NJ, 2003. [4] A. Bjorklund, “Occupational Therapy Students’ Para- digms: A Passage from Beholder to Practitioner,” Austra- lian Occupational Therapy Journal, Vol. 47, No. 3, 2000, pp. 97-109. [5] B. P. Velde, P. P. Wittman and V. W. Mott, “Hands on Learning in Tillery,” Journal of Transformative Educa- tion, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2007, pp. 79-92. [6] S. Novak, S. Shan, J. P. Wilson, K. A. Lawson and R. D. Salzman, “Pharmacy Students’ Learning Styles before and after a Problem-Based Learning Experience,” Ameri- can Journal Pharmacy Education, Vol. 70, No. 4, 2006, pp. 1-8. [7] F. Milligan, “Beyond the Rhetoric of Problem-Based Learning: Emancipatory Limits and Links with An- dragogy,” Nurse Education Today, Vol. 19, No. 7, 1999, pp. 548-555. [8] C. B. Royeen, “A Problem-Based Learning Curriculum for Occupational Therapy Education,” American Journal of Occupational Therapy, Vol. 49, No. 4, 1994, pp. 338- 346. [9] M. A. Albanese and S. Mitchell, “Problem-Based Learn- ing: A Review of the Literature on its Outcomes and Im- plementation Issues,” Academic Medicine, Vol. 68, No. 1, 1993, pp. 52-81. [10] K. G. Vorman and N. MacRae, “How Should the Effec- tiveness of Problem-Based Learning in Occupational Therapy Education be Examined?” American Journal of Occupational Therapy, Vol. 53, No. 5, 1999, pp. 533- 536. [11] M. Law, B. Cooper, S. Strong, D. Stewart, P. Rigby and L. Letts, “The Person-Environment-Occupation Model: A Transactive Approach to Occupational Performance,” Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, Vol. 63, No. 1, 1996, pp. 9-23. [12] M. McParland, L. M. Noble and G. Livingston, “The Effectiveness of Problem-Based Learning Compared to Traditional Teaching in Undergraduate Psychiatry,” Medi- cal Education, Vol. 38, No. 8, 2004, pp. 859-867. [13] G. R. Norman and H. G. Schmidt, “Effectiveness of Prob- lem-Based Learning Curricula: Theory, Practice and Pa- per Darts,” Medical Education, Vol. 34, No. 9, 2000, pp. 721-728. [14] J. Cohen-Schotanus, A. M. Muijtjens, J. Schönrock- Adema, J. Geertsma and C. Van der Vleuten, “Effects of Conventional and Problem-Based Learning on Clinical and General Competencies and Career Development,” Medical Education, Vol. 42, No. 3, 2008, pp. 256-265. [15] J. Colliver, “Effectiveness of Problem-Based Learning Curricula: Research and Theory,” Academic Medicine, Vol. 75, No. 3, 2000, pp. 259-266. [16] G. Goelen, G. De Clercq, L. Huyghens and E. Kerckhofs, “Measuring the Effect of Inter-Professional Problem- Based Learning on the Attitudes of Undergraduate Health Care Students,” Medical Education, Vol. 40, No. 6, 2006, pp. 555-561. [17] S. Reeves, L. S. Mann, M. Caunce, S. Beecraft, R. Living and M. Conway, “Understanding the Effects of Problem- Based Learning on Practice: Findings from a Survey of Newly Qualified Occupational Therapists,” British Jour- nal of Occupational Therapy, Vol. 67, No. 7, 2004, pp. 323-327. [18] P. L. Schaber, “Incorporating Problem-Based Learning and Video Technology in Teaching Group Process in an Occupational Therapy Curriculum,” Journal of Allied Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE  Using Problem Based Learning in Training Health Professionals: Should it Suit the Individual’s Learning Style? Copyright © 2010 SciRes. CE 32 Health, Vol. 34, No. 2, 2005, pp. 110-116. [19] M. E. Scaffa, “Effects of Problem-Based Learning on Clinical Reasoning in Occupational Therapy,” American Journal of Occupational Therapy, Vol. 58, No. 3, 2004, pp. 333-336. [20] J. Hammel, C. B. Royeen, N. Bagatell, B. Chandler, G. Jensen and J. Loveland, “Student Perspective on Prob- lem-Based Learning in an Occupational Therapy Cur- riculum: A Multiyear Qualitative Evaluation,” American Journal of Occupational Therapy, Vol. 53, No. 2, 1999, pp. 199-206. [21] G. Kielhofner and J. P. Burke, “A Model of Human Oc- cupation, Part 1. Conceptual Framework and Content,” American Journal of Occupational Therapy, Vol. 34, No. 9, 1980, pp. 572-581. [22] G. Kielhofner, “A Model of Human Occupation. Theory and Application,” Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, 1985. [23] D. H. J. M. Dolmans, H. G. Schmidt and W. H. Gijselaers, “The Relationship between Student-Generated Learning Issues and Self-Study in Problem-Based Learning,” Journal of Instructional Science, Vol. 22, No. 4, 1994, pp. 251-267. [24] R. M. Fedler and L. K. Silverman, “Learning and Teach- ing Styles in Engineering Education,” Engineering Edu- cation, Vol. 78, No. 7, 1998, pp. 674-681. [25] R. M. Fedler, “Reaching the Second Tier: Learning and Teaching Styles in College Science Education,” Journal of College Science Teaching, Vol. 23, No. 5, 1993, pp. 286-290. [26] B. Soloman and R. M. Felder, “Index of Learning Styles (ILS)”. http://www.ncsu.edu/felder-ublic/ILSpage.html [27] R. M. Felder and J. Spurlin, “Applications, Reliability and Validity of the Index of Learning Styles,” Interna- tional Journal of Engineering Education, Vol. 21, No. 1, 2005, pp. 103-112. [28] D. A. Cook and A. J. Smith, “Validity of Index of Learn- ing Styles Scores: Ultitrait-Multimethod Comparison with Three Cognitive/Learning Style Instruments,” Medical Education, Vol. 40, No. 9, 2006, pp. 900-907. [29] C. R. West, J. H. Kahn and M. M. Nauta, “Learning Styles as Predictors of Self-Efficacy and Interest in Re- search: Implications for Graduate Research Training,” Training and Education in Professional Psychology, Vol. 1, No. 3, 2007, pp. 174-183. [30] P. L. Weiss, N. Schreuer, T. Jermias-Cohen and N. Jos- man, “An Online Learning Course in Ergonomics,” Work, Vol. 23, No. 2, 2004, pp. 95-104. [31] A. T. Litzinger, S. H. Lee, J. C. Wise and R. M. Felder, “A Psychometric Study of Index of Learning Styles,” Journal of Engineering Education, Vol. 96, No. 4, 2007, pp. 309-319. [32] K. B. Baron and C. Cuurtin, “A Manual for Use with Self-Assessment of Occupational Functioning,” Depart- ment of Occupational Therapy, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1990. [33] A. D. Henry, K. B. Baron, L. Mouradian and C. Curtin, “Reliability and Validity of the Self-Assessment of Oc- cupational Functioning,” American Journal of Occupa- tional Therapy, Vol. 53, No. 5, 1999, pp. 482-488. [34] B. Messer and S. Hatter, “Manual for the Adult Self- Perception Profile,” University of Denver, Denver, 1986. [35] B. Nevo, “Examinee Feedback Questionnaire: Reliability and Validity Measures,” Education & Psychology Meas- urements, Vol. 55, No. 3, 1995, pp. 499-504. [36] V. M. Titiloye and A. H. Scott, “Occupational Therapy Students’ Learning Styles and Application to Professional Academic Training,” Journal of Occupational Therapy and Health Care, Vol. 15, No. 1-2, 2002, pp. 145-155. [37] N. Katz and N. Heimann, “Learning Style of Students and Practitioners in Five Health Professions,” Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, Vol. 11, No. 4, 1991, pp. 238-244. [38] C. A. Carver, R. A. Howard and W. D. Lane, “Addressing Different Learning Styles through Course Hypermedia,” Transactions on Education, Vol. 42, No. 1, 1999, pp. 33- 38. |