Creative Education 2012. Vol.3, No.4, 439-447 Published Online August 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.34068 Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 439 Beginning Teachers’ Perceptions of Their Training Programme ——Lessons from the Experience of a Cohort of Vanuatu Institute of Teacher Education Graduates Govinda Ishwa r Lingam The University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji Email: govinda.lin gam@usp.ac. fj Received June 5th, 2012; revised July 10th, 2012; accepted July 28th, 2012 The study reported here sought to determine how a cohort of beginning teachers perceived the training programme they completed at the Vanuatu Institute of Teacher Education to prepare them for the work expected of them in Vanuatu primary schools. All graduates of the programme in the study sample were in their first year of teaching and their opinions were surveyed by means of a self-administered question- naire. Analysis of the data showed that the beginning teachers were generally positive about their training programme though some did express concerns about some important areas of it that they considered need improvement. Substantial implications of the study impinge on three areas: the quality of the teacher training programme; the roles and responsibilities expected of teachers in schools; and the quality of edu- cation provided to the nation’s children. Implications of the study have relevance for other teacher educa- tion institutions in the region and beyond in their professional preparation of teachers, at the pre-service stage, for the myriad demands of work expected of them in a range of school settings. Keywords: Beginning Teachers; Teacher Education Programme; Teachers’ Work; Small Developing Island States; Pacific Context Introduction Several inputs contribute to improving the quality of educa- tion, which in turn determines the quality of children’s learning outcomes. Among them are curriculum and resources, school leadership and management, student participation, parental and community participation, and effective accountability and evaluation systems (Ishumi, 1986; Lockheed & Verspoor, 1991; Grodsky & Gamoran, 2003; Tikly, 2010). While the contribu- tion of each of these inputs is important, it is an undeniable fact that success and failure in achieving quality education lies pri- marily in the hands of classroom teachers (Delors, 1996) and it is vital to recognise the centrality of the classroom teacher’s role in achieving quality education. In particular, it is the pro- fessional competence of the teachers that is considered the most important contributing factor in improving the quality of educa- tion, for they are the front-line agents responsible for translating such things as curriculum, resources and educational policies into effective practice (Gamage & Walsh, 2003; Grodsky & Gamoran, 2003). The professional competence of teachers, however, depends to a large extent on the quality of their preparation and, in particular, the courses in the pre-service programme, which must be aligned with and relevant to the work and responsibilities teachers will meet inside and outside the classroom (Gendall, 2001; Lingam, 2010). The courses should, as well, remain responsive to emerging changes, ideas and issues related to teacher education and school work. It is teachers’ professional preparation and the expectations and demands of their work in schools that are the focus of the pre- sent study. Literature In 1995, a meeting of the Pacific Teacher Education Consul- tation working group was convened at the University of the South Pacific (USP). Six principals of Regional teacher training colleges were included among participants, who developed an ideal teacher education curriculum for the Pacific. An ideal teacher education curriculum, they reported, should produce a teacher who: [Views education holistically]—who is concerned for the overall physical, mental, cultural and spiritual development of the child; Recognises the cultural underpinning in the various disci- plines and uses these to advantage; Has a thorough understanding of human development in the Pacific, and of the roles of education in Pacific societies; Views education as preparation for life, not merely for em- ployment, so that she/he develops each child’s potential to become a [valuable] member of society; Has sufficient flexibility not only to draw on the strengths and inspirations of his/her cultural roots, but also to be able to engage with and educate children of differing cultural backgrounds and in the contemporary context of continual societal, cultural and technological changes (the ability to balance western and traditional cultural values and method- ologies would be valuable); Has the necessary problem-solving and research skills to be a reflective teacher; Sees himself/herself as a positive role model for the chil- dren and for the community in which he/she serves; Has appropriate [knowledge] to learn skills to cope with changes in the physical and social environment; Has a thorough and up-to-date knowledge of the school curriculum; Is able to successfully function in multiple-class or very large, single-class contexts;  G. I. LINGAM [Actively pursue opportunities for] ongoing professional development; Will be able to evaluate both learning and teaching quality; Assists in evaluation and revision of the teacher education curriculum. Participants added that the curriculum must also cater for: Early childhood education; Special education; Multiple-class teaching; Teaching on outer islands [and in other remote localities]; Culture-based content and methodologies. (Benson, 1995: p. 3) Most of these outlined aspects of the ideal teacher education curriculum are relevant, and Regional teacher education institu- tions in small island states of the Pacific could well use them to determine whether they are reflected in their curricula. Broadly speaking, the ideal teacher education curriculum should cater for the knowledge and skills relating to the key areas of teach- ers’ world of work, such as pedagogy; learning experiences; learning environment; assessment and reporting; professional and community relationship; curriculum framework and seek- ing to learn (Education Queensland, 2000). Inadequate prepara- tion in any one of the areas mentioned can have adverse effects on children’s learning outcomes. In the case of Pacific islands countries, multi-class teaching is a topical issue yet many teacher education institutions have not provided any training in it for their pre-service teachers, who as a result face considerable difficulties (Lingam, 2008; Learning Together, 2000; Collingwood, 1991). Since the statis- tics indicate a widespread occurrence of multi-class teaching arrangements in Pacific schools (Collingwood, 1991), the train- ing of teachers in appropriate teaching methods seems vital. This has been a long-standing area of weakness in the primary education system in the Pacific, although some training col- leges have received overseas assistance to incorporate a multi- class component in their training programme. The former Lau- toka Teachers’ College (now incorporated into the Fiji National University, FNU) is one example, having received funding and technical assistance towards upgrading the training programme with a component on multi-class teaching (Lingam, 2003). It appears that limited financial resources and unavoidably high- cost for training make it difficult for the small island states to provide adequate training for the full range of teachers’ roles and responsibilities, often including handling multi-class teach- ing. But the multi-class teaching phenomenon is a common one, not confined to the Pacific but also prevalent in countries be- yond the Pacific region and prospective teachers everywhere need adequate preparation to carry out the work effectively in multi-class teaching arrangements (Cornish, 2006; Lingam, 2006). Apart from the special training needs of multi-class teachers, there are calls for the preparation of beginning teachers in school leadership matters, because in contemporary times stake- holders are putting schools under considerable pressure to op- erate effectively and efficiently (Boyd, 1999; Lingam, 2010). School organisations have now become quite complex and the training of school leaders is essential. Some countries in the Pacific, such as Solomon Islands and Fiji, have embarked on training programmes for school leaders (Lingam, 2010). A re- view of research on teacher leadership concluded that today, teachers assume leadership functions at both instructional and organisational levels (York-Barr & Duke, 2004). To this end, pre-service teacher education programmes should give due consideration to leadership development. Education and train- ing on school leadership should not be restricted to head teach- ers and principals but also include all other teachers as they in some way carry out leadership roles and responsibilities (Bush- er & Harris, 2000; Dinham, 2005). In this regard, the Univer- sity of the South Pacific (USP) responded well by initiating a Diploma in Educational Leadership programme for aspiring and serving school leaders (Velayutham, 1994). In recent years, however, the number of students enrolling in this programme has declined due to limited scholarship opportunities. The Uni- versity’s School of Education, in case of requests by individual countries, mounts in-country projects to prepare school leaders professionally. In addition, at the postgraduate level there are provisions for those students who wish to specialise on the leadership strand. In recent decades, the importance, in the development of re- flective teachers, of suitable problem-solving and research skills, has been recognised increasingly (Baba, 1999). In the contemporary world, the development of such teachers, able to learn from reflection on their experiences, is crucial. Develop- ment of an inquiry ethic is seen as integral to continuous reflec- tion and improvement of professional practice (Darling-Ham- mond, 1992). The 1995 Pacific Teacher Education Consultation working group was also emphatic about the need for teachers to possess knowledge and skills associated with research (Benson, 1995). As far back as the 1990s, Fiji’s then Minister for Na- tional Planning and Information, the Honourable Senator Filipe Bole (1999), was already advocating tertiary education as a means to prepare students better for research and life-long edu- cation in the widest sense. Consideration of the educational and cultural context in which the teachers are going to work would also be profession- ally sound when any decision on teacher education curriculum was made, helping better contextualise teacher preparation programmes. As suggested by Konai Thaman (1998: p. 11): … Teacher educators need to be able to utilize content that is familiar to trainees as well as methods and tech- nologies which are appropriate for and relevant to their learning contexts. These would go a long way towards improving the quality of teacher education in the region. Clearly, teacher educators need to take cognizance of cultural context and try to incorporate certain aspects of the culture, especially in the methods and content of the teacher education courses (Taufeulungaki, 2000). Such practices will enable be- ginning teachers to use culture-based methodologies together with western teaching methods to enhance teaching and learn- ing processes, to help children achieve optimal learning out- comes. The significance of contextual factors in any educa- tional development effort should receive due attention for its success (Crossley, 2010). In the context of continuous change, new ways of thinking and new skills need to be acquired to cope well with the con- temporary demands of work (Fullan & Hargreaves, 1991). As a result, some educational contexts have made their teacher education curriculum more practice-oriented. One shinning ex- ample is England, where the teacher education curriculum con- centrates more on what teachers actually do in the classroom (Bridge, 1996; Cowen, 1990). As Bridge (1996: p. 7) points out: Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 440  G. I. LINGAM Initial teacher education in the UK has undergone major changes in the last few years with the increasing devel- opment of partnership schemes between schools and higher education institutions. The result is that more of the training of student teachers takes place in schools un- der the guidance of trained teachers. Similarly, in most US teacher education institutions, the trend has been towards a competency-based teacher education approach (Levine & Ornstein, 1982). Some, though, argue that a competency-based approach is too narrow for the broad range of duties teachers are required to carry out (Lester, 1995; Bar- nett, 1994). Cairns (1998) has proposed that capability rather than competency may be a more useful way of understanding what is needed to deal with the myriad of changes, challenges and pressures faced by modern-day primary teachers. This competency-based approach places greater emphasis on classroom practice and the expectation is that student teachers will acquire the various skills needed to function effectively in the classroom. The dilemma these two approaches create is well summarised by Horn (1994: p. 83) as: ... One of the two biggest debates in the field of teacher education [is] which should be stressed in the formation of a teacher... content courses or methods courses? It is uncommon to find teacher education institutions placing different emphasis on content courses and methods courses. For example, Grossman, Wilson and Shulman (1989), consider the importance of subject matter knowledge in enhancing instruc- tion. Lawlor (1990) also claims that teachers need an in-depth study of the subjects in the national school curriculum, rather than too much of the study of theories in education. To enhance teaching and learning, both content and methods courses are important, and Summers (1994) has used the term curricular expertise in referring to both content and method of teaching. In the same vein, Morrison (1989) regards both types of knowl- edge, content and pedagogical, as crucial in influencing effec- tive and efficient teaching performance. Teachers whose knowl- edge of both content and pedagogy is limited could seriously find their work performance hampered in classroom situations, and at the same time , find themselves undermining the teaching and learning process. Like other international organisations, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (1994: pp. 14-15) has re- garded the following types of “knowledge” and “skills” as ap- propriate for teachers: Content knowledge or knowledge of the substantive cur- riculum areas required in the classroom; Pedagogic skills including the acquisition and ability to use a repertoire of teaching strategies; Reflection and the ability to be self critical, the hallmark of teacher professionalism; Empathy and commitment to the acknowledgment of the dignity of others; Managerial competence, as teachers assume a range of ma- nagerial responsibilities within and outside the classroom. The suggested knowledge and skills are necessary to ensure the beginning teachers can execute their duties and responsi- bilities effectively. A study by Deer and Williams (1996) showed that a number of teacher education programmes have embraced these dimensions within the general expectations of “nowing and caring”. The teacher education curriculum should enable future teachers to deliver education effectively and si- multaneously to take charge of the welfare and safety of the children. Further, the teacher education curriculum should be based on a constructivist perspective of the teaching and learning process. This perspective should be adopted not only in the courses taught, but also in the field experience. Fosnot (1993: p. 27), who supports this view, states: Just as young learners construct, so too, do teachers... Teachers’ beliefs need to be illuminated, discussed, and challenged... Prospective teachers need to confront tradi- tional beliefs, study children’s meaning making and ex- periments, collaboratively within a classroom context. It is only through such practices that teachers can contribute to meaningful teaching and learning. A constructivist approach needs to start in initial teacher preparation, in order that the approach become part of the teachers’ professional develop- ment. Exposure of teacher trainees to a comprehensive teacher education curriculum will ensure that they acquire adequate knowledge in areas such as learning theory, child development and pedagogy, as well as practical experience in teaching. This would help them to attend better to the needs of pupils and teach more effectively. Teachers in small island states such as those in the Pacific are expected to perform multiple roles. This fact also warrants due attention from teacher educators. Farrugia (1993: pp. 44-45) says in regard to the professional development of educational personnel: The special demands on education officials and adminis- trators in small states, particularly, the need to work in a multiplicity of roles, seems to dictate the development of new patterns of professional training. The more appropri- ate are those of a multi-disciplinary nature, structured on a modular system to reflect the adaptability and flexibility so characteristic of the officials’ work. This is true not only for education officials and administra- tors, but equally for classroom teachers, as they are expected to perform a variety of duties, some of which require reaching out to the community the school serves. Velayutham (1987: p. 29) reaffirms this in the statement that: In the field of education teachers not only work with col- leagues in the school but also with people outside the school such as parents, community leaders, church work- ers and even with people at the grass-root level. Hence, the professional role of teachers extends beyond the classroom situation. To enhance the handling of all these responsibilities in tan- dem with working with other people, agencies and organiza- tions involved in educational development, the initial teacher education training programme should give beginning teachers some experience in the necessary skills for collaborating with other relevant organizations in their communities. The skills associated with working in partnership with the community, once incorporated into the teacher education curriculum, will prepare beginning teachers to accept and work within a broader definition of their role. The preceding review of literature on teacher education illus- trates that without adequate professional preparation on the Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 441  G. I. LINGAM roles and responsibilities expected of teachers in the workplace, beginning teachers could be faced with considerable difficulties in effectively carrying out the full range of their work in schools. The literature also makes it clear that the first desid- eratum for the professional preparation of beginning teachers is a teacher education curriculum suitable for meeting the de- mands of teachers’ world of work. Only if they seriously con- sider the suggestions advanced in the literature will teacher education institutions develop programmes better able to pro- duce teachers of high quality. Study of a Cohort of Vanuatu Institute of Education Graduates Purpose of the Study The present study focused on how beginning teachers felt about the value of the pre-service training programme, which they had recently completed, in preparing them to meet the demands of work expected of them in primary schools in one small island state in the region. One research question guided the study: What do these beginning teachers perceive about the pre-service training programme that they completed in meeting the demands of work expected of them in the field in their first year out? Significance of the Study The findings of the study were expected to provide insights into the value of the pre-service training programme of the institution, especially in relation to the work expectations new teachers’ encounter in school settings. The study was particu- larly intended to draw attention to the beginning teachers’ con- sidered opinions on the strengths and weaknesses of the pre- service programme in meeting the workplace demands they actually encountered in their first teaching year. In this regard, the present study has the potential to provide relevant feedback to the institution as it ponders developing and strengthening its teacher education programme. The study will also contribute to the accumulation of knowl- edge in the area of teacher education, and in particular, pre-service teacher education, for the small island states in the Pacific region. Presently, there is a dearth of research literature on teacher education in small island states (Crossley et al., 2011). The findings from this study could, thus, provide vital information to those who have a vested interest in teacher edu- cation, especially the principal stakeholder in the education systems (usually the ministries of education), in order to de- velop suitable mechanisms to address gaps in teacher education. Also, the findings will contribute towards the build of local and international literatu r e on teacher educ a t io n. In addition, for the researcher as a teacher educator responsi- ble for the in-service education of regional primary teachers at the USP in the Bachelor of Education (Primary) degree pro- gramme, the findings will be helpful in informing practice—my own as well as that of my colleagues in the School of Education. The findings will contribute to the provision of relevant prepa- ration for future in-service primary teachers, to ensure they are better equipped to meet the various demands and expectations of work in schools. Finally, the present study may act as a catalyst to other researchers in the Pacific region and beyond to undertake studies on teacher education issues in general and specific developing contexts. The Study Context Vanuatu is a small developing nation in the Pacific region, though it is many times larger than several of the other coun- tries in the vast region served by USP. For a significant part of its colonial experience, it was a condominium—sometimes known, with affectionate cynicism, as a pandemonium—of Bri- tish and French colonial rule. Consequently, the small country is left with a double heritage in many administrative and bu- reaucratic areas including the law, health and education. Thus, the Vanuatu Institute of Teacher Education (VITE) is responsi- ble for the training of teachers for both francophone and an- glophone primary and secondary schools. With respect to the training of primary teachers, the Institute has in place a two- year training programme for both francophone and anglophone teachers, leading to a Certificate in Primary Teaching. “Excel- lence in Primary and Secondary Education” and “To promote pre-service and in-service teacher training of teachers for the Republic of Vanuatu” are the respective vision and mission statements of the Institute (VITE, 2005: p. 5). For the six years from 2004 to 2009 the Institute supplied about 218 trained teachers for the Republic of Vanuatu primary schools (VITE, 2009). In the late 1990s and at the turn of the 21st Century the Institute received funding and technical assis- tance from the World Bank, the Australian Government, the French Government and the European Union, making it possi- ble to carry out some revisions of the training programme and infrastructure development, as well as some professional de- velopment for the staff. Delimitations This study is limited to just one of the regional primary teacher education institutions in the Pacific region, VITE; the graduates of only this one teacher institution participated in the study. In view of this, it may not be possible to generalize the findings to other teacher education institutions in the Pacific. The findings, however, could provide relevant information about the quality of the preparation of teachers available to the Vanuatu primary education system, as the Institute is the sole provider of teachers needed for the nation’s primary schools. Method Instrument The schools in which these graduates were teaching included both urban and remote island examples. The scattered distribu- tion meant that the most useful research tool for gathering data seemed to be a survey questionnaire (Gay, 1992). The ques- tionnaire consisted of two major sections: Section A with closed questions relating to the pre-service programme the teachers had completed the previous year and Section B in- cluding an open-ended question relating to areas the respon- dents considered needed attention in the pre-service programme. These were similar to the open ended approach used in phe- nomenographic research (Marton, Dall’Alba, & Beaty, 1993). They were asked to respond to these questions after critical reflection on the training programme they had completed and the work they were now required to carry out in primary schools. For the closed-ended questions a 5-point likert scale was used: 1being the lowest and 5 highest being the highest. Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 442  G. I. LINGAM Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 443 Sample The participants included for the study were the entire cohort of 33 graduates for the year 2009 from the Vanuatu Institute of Teacher Education. Procedure A complete listing of all the graduates was obtained from the Planning Division of the Ministry of Education and the VITE. Permission was obtained from the following relevant authori- ties before gathering data from the beginning teachers: Depart- ment of Education Vanuatu and the Principal and staff of VITE. In a covering letter, the beginning teachers were informed that participation in the study was voluntary and that data collected would be analysed and reported in such a way that their confi- dentiality and anonymity would be ensured. Satisfied with the procedures followed, the School of Education Postgraduate Research Committee provided ethical clearance for conduct of the study. Analysis Techniques The quantitative data were analysed using the basic statistics of means and standard deviations (Mehrens & Lehmann, 1991). The qualitative data obtained from the open-ended question were analysed in terms of the themes and patterns that emerged from reading and re-reading the data (Bogdan & Biklen, 1992). These were then interpreted in relation to the existing literature to answer the research question posed. In addition, relevant quotations from the open-ended questions are presented as they demonstrate the beginning teachers’ perceptions of their train- ing programme in relation to the work required of them in the schools. In selecting to do this, the researcher gave weight to Ruddock’s (1993: p. 19) suggestion that “some statements carry a rich density of meaning in a few words”. Results The summary of the quantitative data is presented in Table 1. The statements are categorised according to the nature of work expected of teachers in schools. The seven broad categories suggested by Education Queensland (2000) and the OECD (1994) were borne in mind as helpful in the present study in terms of grouping the statements: Pedagogy; Learning Experi- ences; Learning Environment; Assessment and Reporting; Pro- fessional and Community Relationships; Curriculum Frame- work; and Seeking to Learn. Table 1. Ratings by factors. Major Category Statement Group Mean (N = 33) Standard Deviation (SD) Pedagogy Presented methods that have been useful in my teaching. 3.9 0.69 Developed my skills in planning for teaching. 4.5 0.49 Provided me with adequ ate theore ti cal knowl edge on teaching and learning process. 3.9 0.52 Curriculum Framework Familiar i sed me with the primary cur r iculum. 3.9 0.61 Learning Experiences Helped me to or ganise and conduct extra-curricular activities in the school. 3.8 0.69 Provided me the skills required to give support to children with learning difficulties. 3.8 0.57 Developed my ability to e ng age children actively in developi ng knowledge. 4.5 0.50 Prepared me to maintain class discipline adequately. 4.2 0.73 Assessment and Reporting Ma de me familiar with a vari ety of assessme nt techniques. 4.0 0.79 Professio nal an d Community Relationships Developed my ability to work with children and parents of other linguistic groups. 3.7 0.91 Developed my ability to wor k collaboratively with parents a n d colleagues . 4.2 0.56 Helped me to carry out work in the school’s com munity. 3.8 0.68 Seeking to L earn Developed my ability to reflect crit i cally on my own practice to improve the quality of my work. 2.5 0.64 Made me enthusiastic about te ach in g. 3.7 0.55 Prepared me to carry out research to inform my practice. 3.0 0.73 Developed my ability to learn independently. 3.8 0.63 Learning Environment Prepared me to perform a dministrative duties. 2.5 0.74 Prepared me for multi-class teaching. 2.6 0.84  G. I. LINGAM Qualitative Data When the beginning teachers were asked to indicate areas in their training programme they felt needed attention, heading the list and in order of frequency of mention were multi-class teaching, school practicum, school administration, relevance of some of the courses, duration of the training programme and programme upgrading, learning environment, staff responsibil- ity and resear ch. Some of the comments showing beginning teachers’ concern about the quality of the preparation for multi-class teaching are representative: I think it is better to have more training for multi-class teaching. A trained teacher will have better knowledge and skills to teach [in the multi-class context]. If I were given this opportunity I would improve multi- class teaching. This is because most teachers out in the field, especially in remote areas, are teaching multi-class while they had not been educated or trained in this spe- cific area. If I am given the opportunity to improve the college pro- gramme, I will incl ude t h e multi-class training programme. There are not enough trained teachers in the field and the College is not providing anything on this. I mean, there is one book on multi-class teaching but the College has not considered this as an issue. All teachers in the field today in Vanuatu are single-class teachers. This is one reason why single-class teachers cannot teach multi-class... we do not have quality education. [If] we have trained multi- class teachers here, we can provide quality education no matter the situation of the class. The experience here does not deliver anything on multi- class teaching. Therefore to make sense that this can be included in the training programme, it is best to include that in the Professional Studies component. This must be taught throughout a term so that the trainees may be fully equipped on how to cope with multi-class teaching in fu- ture. In relation to improving school practicum, the following are some of the typical comments from the beginning teachers: To improve the pre-service progr amme, the aspect I would change is to increase the number of practicums. For in- stance, practicums are often carried out once a year. To improve the trainees’ experience in teaching, I think there should be two practicums in a year, which will allow the trainees to have better ability to implement and cultivate more learning from their practicums. One aspect that I would change is to avoid conducting as- sessments in other courses when students go out for teach- ing practice. They must concentrate on teaching practice and not other work. Some of the beginning teachers’ responses on training in school administration are equally telling: An important aspect is school administration. We should understand how to administer school affairs. Because so many times we get the name Head Master but we do not know how to run the school. It is a major need [for the College] to provide better training for administration. So when teachers [graduate] they will know better how to administer schools back in their islands. School administration training should be also included in the pre-service programme because most teachers who come from remote areas need to know some administra- tion skills, how to head a school and upgrade education standards of the school. As experienced, most teachers when they finish from the College they become head teachers so they face difficulties on administration be- cause there are no other teachers trained especially for ad- ministration. On the learning environment at VITE, the following are some of the comment s: This is not a secondary level of education, this is a high institute of learning so it needs a high quality of learning resources, classrooms and facilities as well as other areas and buildings that need improvement. Improve kitchen, sleeping rooms and classroom condi- tions as they are very poor. Rebuild some of the classrooms because some of the class- rooms are too old. Trainees need a good classroom envi- ronment to learn. With regard to programme duration and upgrading, the fol- lowing were some of their comments: Most of all I would like to see all the primary student teachers graduating with a Diploma instead of a Certifi- cate. I would change the length or period of studying here. The period of studying here is only 2 years, which I think is not enough to get all information about teaching. I think this should be extended to 3 to 4 years. I say this because in primary courses we have more [to cover] than the sec- ondary and when towards the end of the two years, lec- turers try to rush with what they think is important and we try to cope, which is very difficult. Therefore, I think 3 or 4 years’ training will be better for every one of us, the lecturers and the trainees for better future teachers. Regarding staffing, the beginning teachers also offered per- tinent c omments: Our current lecturer for professional study is on contract after the former one passed away 6 months ago. We have missed a lot of important areas during that period of six month with no tutor. The aspect I would change is that lecturers travel a lot and sometimes we missed some ve ry important things to learn. There should be at least two subject lecturers to a subject, for another one to replace the one travelling. The reason for that is that this year a lot of lecturers have been travel- ling and we find out that sometimes we just rushed through the topics we’ve missed, which is not helpful. Discussion The purpose of the present study was to determine the begin- ning teachers’ perceptions, with hindsight, of their professional Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 444  G. I. LINGAM preparation in relation to what they are experiencing as the work required of them in Vanuatu primary schools. This section takes up the discussion of the findings. Quantitat ive D ata The analysis of the quantitative data for each one of the broad categories points to areas of positive perception and areas needing more attention as perceived by the beginning teachers. Taken as an aggregate, the beginning teachers perceived their training programme positively, finding it helpful in preparing them to meet the demands of work in the primary schools. Considering that high mean scores indicate a favourable re- sponse, the analysis of the quantitative data shows that the be- ginning teachers have a positive perception of the training pro- gramme in terms of the broad dimensions of “knowing and caring” (Deer & Williams, 1996) and “knowledge and skills” (OECD, 1994). In the terminology used in this study, the analysis of the quantitative data demonstrates that the beginning teachers have positive perceptions of their preparation in areas pertaining to pedagogy; learning experiences; learning envi- ronment; assessment and reporting; professional and commu- nity relationships; curriculum framework; and seeking to learn. This is reflected in the fact that the means calculated for most of the major categories exceed 3.0; only in the last category (learning environment) are the means for both the items below 3 (Table 1). In addition, one item under the seeking to learn category has a mean of less than 3. Likewise, the standard de- viations (Table 1) for the items demonstrate few major diver- gences of opinion in the feedback obtained from the beginning teachers. However, the feedback obtained from the beginning teachers on the open-ended question indicate grave concerns relating to certain areas of the pre-service programme and these areas warrant the attention of the relevant authorities. These findings are discussed in what follows. Qualitative Data With regard to areas needing more attention, these new teachers included amongst the areas they found weak an alarm- ingly long list: multi-class teaching, school practicum, school administration, relevance of some of the courses, duration of the training programme and programme upgrading, learning environment, staff responsibility, and research. The beginning teachers used the opportunity presented by the free-response section to express their frustration at the lack of preparation for multi-class teaching. The low mean in the quan- titative data also mirrors this (Table 1). It can be deduced that beginning teachers are well aware of the multi-class teaching arrangement as a norm in remote schools and the difficulties faced in teaching in such school contexts. In fact, its inclusion in the teacher education programme was recommended as far back as the 1990s (Benson, 1995). Inadequate or absent prepa- ration will affect the delivery of education in such circum- stances and ultimately the children will suffer (Lingam, 2008; Learning Together, 2000; Collingwood, 1991). Teacher educa- tion programmes in the regional teachers’ colleges need to in- corporate multi-class teaching components in their programmes as all Pacific regional countries have at least some schools with multi-class teaching as the norm; in particular, the situation is quite common in remote primary schools in regional countries. A degree of understaffing at the Institute, as well as frequent, often unavoidable, absences of lecturers from their duty, have negative effects on beginning teachers in certain areas of their professional preparation. Although constraints in human re- sources in the education ministry of a small island state mean that lecturers may at times be called upon to provide other ser- vices (Farrugia, 1993; Velayutham, 1987), the Institute lectur- ers’ priority should always be their official Institute duty of responsibility for the pre-service professional preparation of teachers. The concern the beginning teachers expressed on teaching practicum is not unique; this has been a recurring theme in other contexts as well. Also, there is an on-going debate in most jurisdictions about the issue (Horn, 1994). The beginning teach- ers have indicated the need to increase the duration of the teaching practicum so that the prac-teachers come to know more about the teachers’ world of work and in some contexts it has been possible to address this concern. For instance, in Eng- land, pre-service teachers are given more opportunities with hands-on experience (Bridge, 1996; Cowen, 1990). As mentioned earlier, teachers in small island states are called upon to carry out many roles and responsibilities, not least of which is school leadership (Farrugia, 1993; Velayutham, 1987). Given the interest in improving educational leadership in today’s schools, the development of a course on school leader- ship would be a step in the right direction (Lingam, 2010; Ve- layutham, 1987; Sanga, Pollard, & Jenner, 1998). Because schools are being subjected to intensifying demands that they operate effectively and provide good quality education, profes- sional preparation programmes should cater also for some train- ing towards educational leadership. Thus apart from preparation on the teaching and learning of the school curriculum, prepar- ing pre-service teachers for leadership would be a welcome move. However, this was not catered for in the training pro- gramme these people had undergone. The feedback from the open-ended question and also the mean for the item reflects this concern (Table 1). Teacher education institutions have the capacity also to nurture future school leaders. Inclusion in the pre-service programme of a component on school leadership or school management would be relevant, as in their future as teachers they will be contributing to improving people and the environment in which they work. Consequently, they would be multi-skilled and multi-talented, not just competent in their classroom work but also possessing skills in managing a school (Velayutham, 1987). In most countries in the Pacific, the lack of training and development of school leaders is already a ma- jor concern (Lingam, 2010). Due to the gaps in their preparation, these graduates from VITE may have been pointing to a need for revision of the teacher education programme as well as suggesting that the programme be upgraded to Diploma level. The feedback is timely as other teachers’ colleges in the region are attempting to upgrade their programmes to Diploma level. There are signs that in the near future the VITE programme may be revised and upgraded. In turn, such a process may address some of issues raised by the beginning teachers (Gladys Patrick, a College lecturer, personal communication, 2009). This would be a posi- tive move as other concerns expressed by the beginning teach- ers could also be given serious consideration, such as the need to provide at the institute a pleasant learning environment with suitable resources and facilities for learning and teaching. Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 445  G. I. LINGAM Implication To achieve primary education of good quality, the first re- quirement is better prepared teachers in the school system. Teachers whose capacity is limited by deficiencies in their preparation will affect children’s education and their future life opportunities. Once teachers are trained and posted to schools, some are effectively inaccessible as the schools in which they teach are too isolated from the main urban centres. Such teach- ers will not, because of the constraints imposed by distance, have at their disposal any means for professional improvement. Even the technology that has revolutionized our present life- styles reserves its greatest benefits to the comfortably off urban dwellers; the delivery of distance learning is still a major chal- lenge in many small island states. In view of this, teacher edu- cation institutions, especially those in the Pacific as well as those with similar characteristics to it, need to revisit their teacher education programmes frequently in the hope of pro- viding better preparation to teachers at the pre-service level. In this regard, cognisance of teachers’ world of work is warranted in the search for ways to improve all teacher education institu- tions, in both developed and developing contexts, due to vari- ous reforms taking place in the field of education. Conclusion Adequate training in all areas of school work is vital to en- sure beginning teachers make a difference in the lives of the students they teach. Otherwise children in schools, especially those in remote areas, will continue to suffer in their pursuit of a better quality of education because of limited capacity of teachers. Since pre-service is the first phase of professional preparation of teachers, it is important that it is strengthened, as not all of the teachers will have opportunities for any in-service training after that. More research could be conducted in future with the same cohort of beginning teachers to determine how they develop their own theories of teaching, especially during the early years of their teaching career. Since the present study is about the perceptions of the beginning teachers on their pre-service training programme, it may say little about the how successfully these teachers have been able to put their learning into practice in their respective schools and classrooms. This could possibly be another area of research endeavour. Though on a small scale, the present study has unearthed some poten- tially relevant information about the pre-service training pro- gramme at VITE and the information could help the institute to strengthen its offerings and live up to its vision and mission. Comparable institutions elsewhere in the region and beyond in other small island developing states and contexts will also be likely to find the Vanuatu experience relevant. REFERENCES Baba, T. L. (1999). Teacher education and globalisation: Challenges for teacher education in the Pacific during the new millennium. Journal of Educational Studies, 21, 31-50. Barnett, R. (1994). The limits of competence. Buckingham: The Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Pre ss . Benson, C. (1995). The ideal teacher education curriculum for the Pa- cific. Pacific Curriculum Network, 14, 3-4. Bogdan, R. C., & Biklen, S. K. (1992). Qualitative research for educa- tion: An introduction to theory and methods (2nd ed.). London: Al- lyn and Bacon. Bole, F. (1999). Globalization and the curriculum. The Seminar for Curriculum Developers, Curriculum Development Unit, Suva, 20 August 1999. Boyd, W. L. (1999). Environmental pressures, management imperatives, and competing paradigms in educational administration. Educational Management and Administrat io n , 27, 283-297. Bridge, F. (1996). Mentoring: Teacher training reform in the United Kingdom. Internat i onal Directions in Education, 3, 7-9. Busher, H., & Harris, A. (2000). Subject leadership and school im- provement. London: P au l C ha pman. Cairns, L. (1998). Teachers, training and development. In T. Townsend (Ed.), The primary school in changing times: The Australian experi- ence (pp. 48-79). London: Routledge. Collingwood, I. (1991). Multi-class teaching in primary schools: A handbook for teachers in the Pacific. Western Samoa: UNESCO of- fice. Cornish, L. (2006). Introduction. In L. Cornish (Ed.), Reaching EFA through multi-grade teaching: Issues, contexts and practices (pp. 1- 8). Armidale, NSW: Kardoorair Press. Cowen, R. (1990). Teacher education: A comparative view. In N. J. Graves (Ed.), Initial teacher education: Policies and progress (pp. 45-57). London: Kogan Page. Crossley, M., Broadfoot, P., & Schweisfurth, M. (2011). Changing educational contexts, issues and identities. Lo n d o n : R o utledge. Crossley, M. (2010). Context matters in educational research and inter- national development: Learning from the small states experience. Prospects, 40, 421-429. doi:10.1007/s11125-010-9172-4 Darling-Hammond, L. (1992). Creating standards of practice and deliv- ery for learner-centred schools. Stanford Law and Policy Review, 4, 37-52. Deer, C., & Williams, D. (1996). US professional development school: Do they have anything to offer Australian teacher education? UNI- CORN, 22, 65-68. Delors, J. (1996). Learning: The treasure within. Paris: UNESCO Pub- lishing. Dinham, S. (2005). Principal leadership for outstanding educational outcomes. Journal of Educational Admini st r at io n , 43, 338-356. doi:10.1108/09578230510605405 Education Queensland (2000). Teachers’ pre-service tertiary education preparation: A summary report of the quantitative data. Queensland: Performance Measurement and Review Branch Office of Strategic Planning and Portfolio Services. Farrugia, C. (1993). The professional development of educational per- sonnel. In K. Bacchus, & C. Brock (Eds.), The challenge of scale: Educational development in the small states of the commonwealth (pp. 36-48). London: Commonwealth Secretariat Publications. Fosnot, C. T. (1993). Learning to teach, teaching to learn: The centre for constructivist teaching/teacher preparation project. Teaching Edu- cation, 5, 68-78. Fullan, M. G., & Hargreaves, A. (1991). Working together for your school: Strategies for developing interactive professionalism in your school. Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Administra- tion. Gamage, D., & Walsh, F. (2003). The significance of professional de- velopment and practice: Towards a better public education system. Teacher Development, 7, 363-379. doi:10.1080/13664530300200218 Gay, L. R. (1992). Educational research. New York: Maxwell Mac- millan International. Gendall, L. (2001). Issues in pre-service mathematics education. The New Zealand Association for Research in Education Conference, Christchurch, 6-9 D ecember. Grodsky, E., & Gamoran, A. (2003). The relationship between profes- sional development and professional community in A merican schools. School Effectiveness an d School Improvem ent, 14, 1-29. doi:10.1076/sesi.14.1.1.13866 Grossman, P. L., Wilson, S. M., & Shulman, L. S. (1989). Teachers of substance: Subject matter knowledge for teaching. In M. C. Reynolds (Ed.), Knowledge base for the beginning teacher (pp. 23-36). New York: Pergamon. Horn, A. (1994). Teacher development as a nation’s development. Fijian Teachers Association Journal, 60, 82-85. Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 446  G. I. LINGAM Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 447 Ishumi, A. G. M. (1986). Innovation for the improvement of educa- tional systems and programmes. Dakar: UNESCO, Regional office for education in Africa. Lawlor, S. (1990). Teachers mistaught: Training in theories or educa- tion in objects? Lon d on: Centre for Polic y Studies. Fiji Islands Education Commission/Panel (2000). Learning together: Directions for education in the Fiji Islands. Suva: Government Printer. Lester, S. (1995). Beyond knowledge and competence. Capability, 1, 44-55. Levine, D. U., & Ornstein, A. C. (1982). An introduction to the founda- tion of education ( 2nd ed.). Boston, MA : Hou ghton Mifflin. Lingam, G. I. (2010). Teachers equip with new skills. Solomon Star, 4, 12. Lingam, G. I. (2007). Pedagogical practices: The case of multi-class teaching in Fiji primary school. Educational Research and Review, 2, 186-192. Lingam, G. I. (2006). Challenges and opportunities in multi-grade teach- ing: The case of Fiji. In L. Cornish (Ed.), Reaching EFA through multi-grade teaching: Issues, contexts and practices (pp. 197-214). Armidale, NSW: Kardoorair Press. Lingam, G. I. (2003). Pre-service programme upgrading: A milestone achievement in primary teacher education for Fiji. Pacific Curricu- lum Network, 12, 36-38. Lockheed, M. E., & Verspoor, A. M. (1991). Improving primary edu- cation in developing countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press for the World Bank. Marton, F., Dall’Alba, G., & Beaty, E. (1993). Conceptions of learning. International Journal of Educational Research, 19, 277-300. Mehrens, W. A., & Lehmann, I. J. (1991). Measurement and evaluation in education and psychology (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company. Morrison, K. (1989). Training teachers for primary schools: The ques- tion of subject stud y. Journal of Educa ti on fo r Te ac hi ng, 15, 97-111. doi:10.1080/0260747890150202 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (1994). Quality in teaching. Paris: OECD. Ruddock, J. (1993). The theatre of daylight: Qualitative research and school profile studies. In M. Schratz (Ed.), Qualitative voices in edu- cational research (pp. 8-23). London: Falmer. Summers, M. (1994). Science in the primary school: The problem of teachers’ curricular expertise. The Curriculum Journal, 5, 179-193. doi:10.1080/0958517940050204 Thaman, K. (1998). Pacific cultures in the teacher education curricu- lum: Research report. Suva: Institute of Education, University of the South Pacific. Tikly, L. (2010). Towards a framework for understanding the quality of education: EdQual Working paper No. 27. Bristol: University of Bristol. Taufeulungaki, A. M. (2000). Vernacular languages and classroom in- teractions in the Pacific. Suva: Institute of Education, University of the South Pacific. Velayutham, T. (1994). Professionalism and bureaucracy: Can they develop together? Directions: Journal of Educational Studies, 30, 69-83. Velayutham, T. (1987). Curriculum making or taking. Pacific Curricu- lum Network, 5, 6-9. York-Barr, J., & Duke, K. (2004). What do we know about teacher leadership? Review of Educational Research, 74 , 255-366. doi:10.3102/00346543074003255

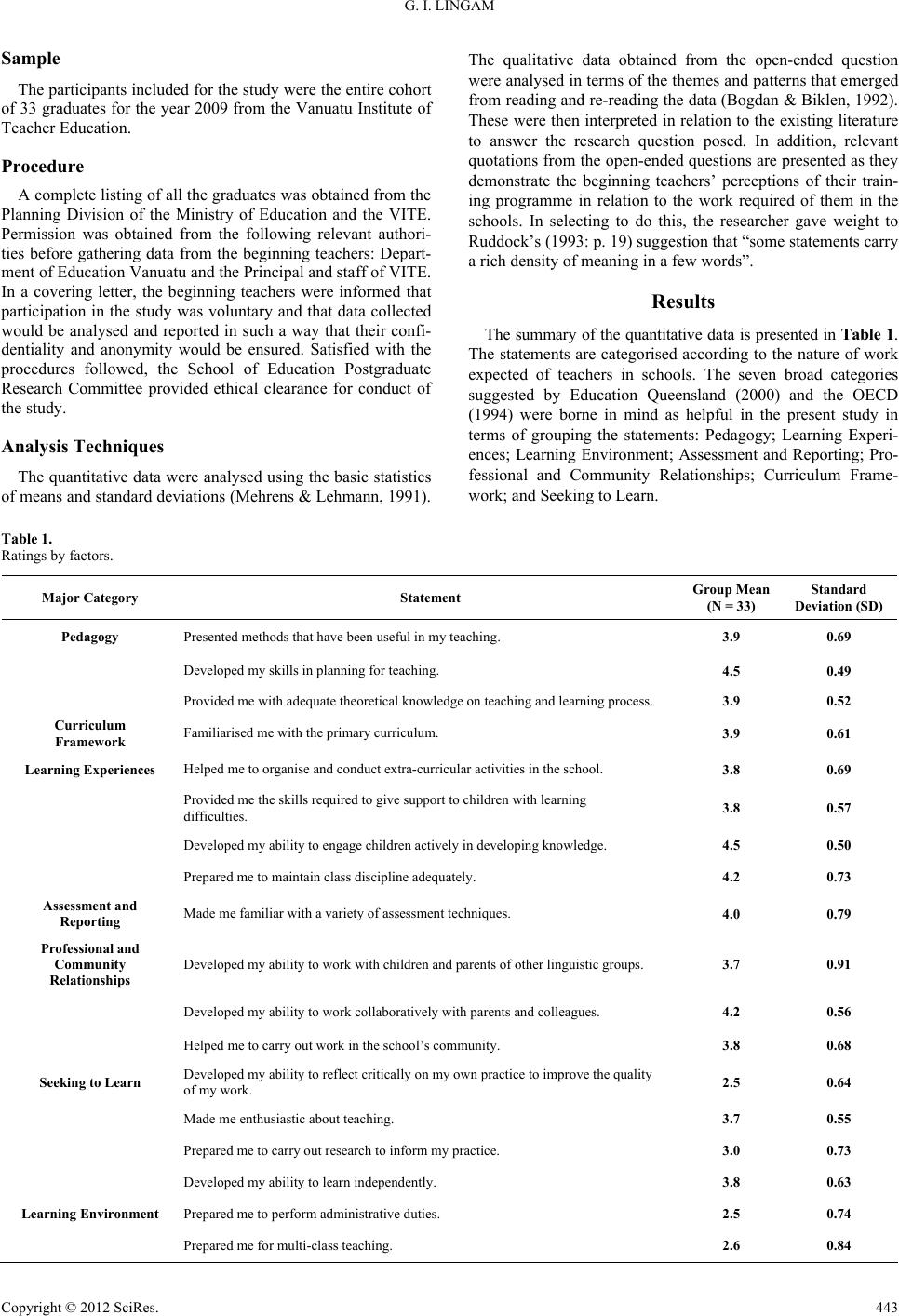

|