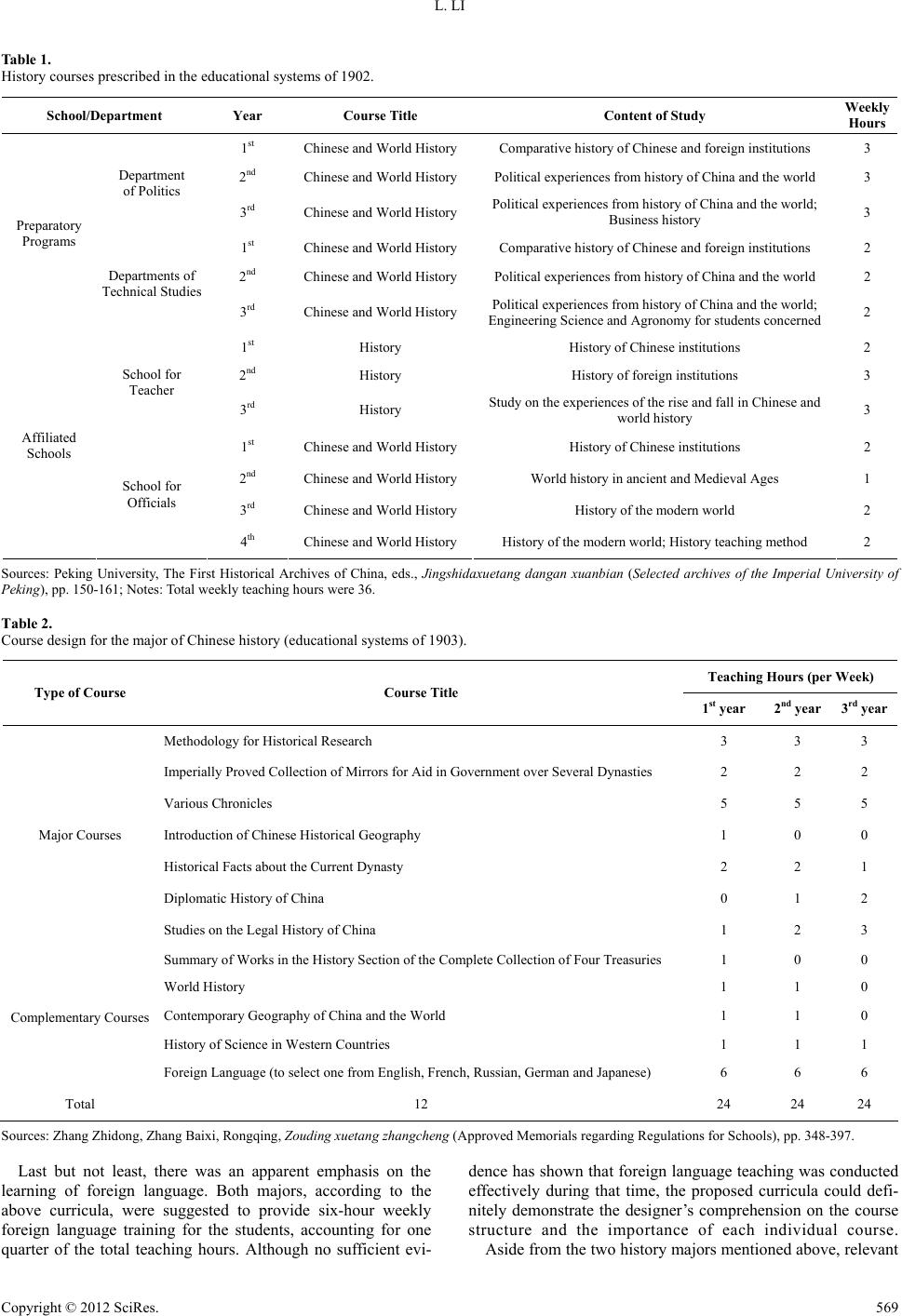

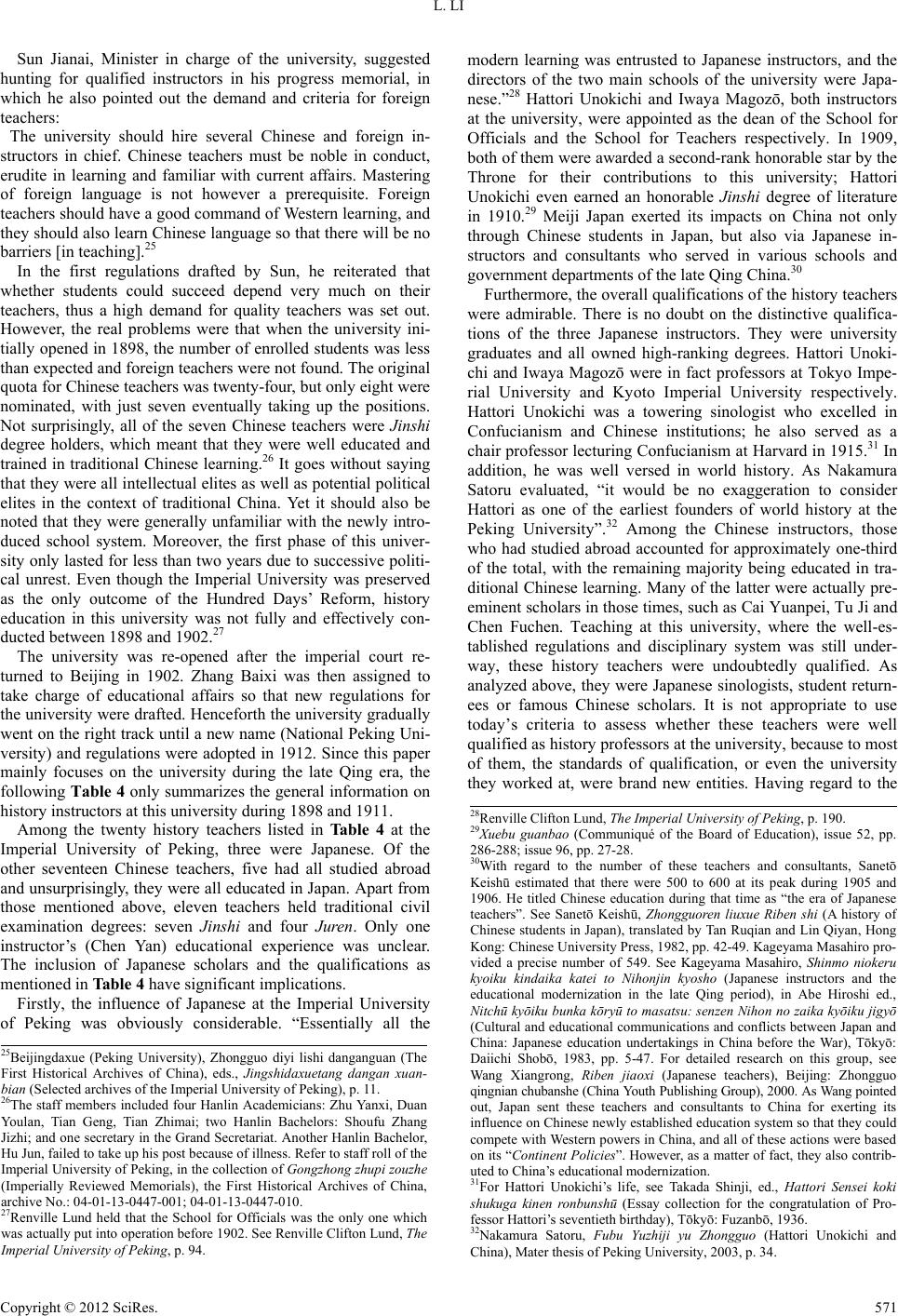

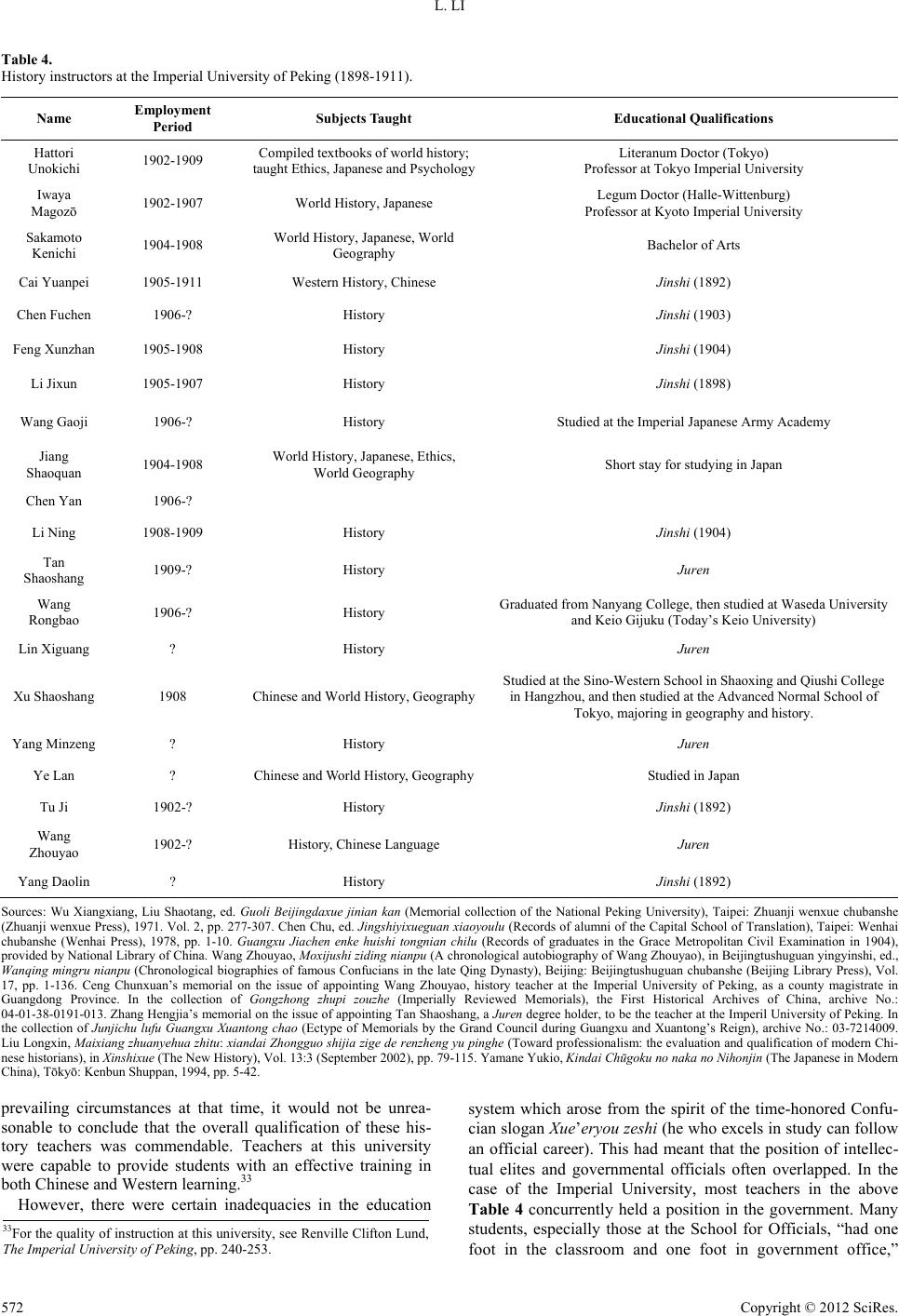

Creative Education 2012. Vol.3, No.4, 565-580 Published Online August 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.34084 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 565 Disciplinization of History Education in Modern China: A Study of History Education in the Imperial University of Peking (1898-1911) Lin Li Department of History, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China Email: philip4781071@126.com Received May 18th, 2012; revised June 20th, 2012; accepted June 29th, 2012 Through a thorough investigation on the history education in the Imperial University of Peking from 1898 to 1911, this paper attempts to highlight the following findings: 1) The disciplinization of history educa- tion and the transformation of traditional historiography were concurrently incepted in the late Qing pe- riod. The Imperial University of Peking served as a pivotal platform for the realization of this synchro- nous process; 2) History instructors and students of this university can be regarded as initial participants in the new school system, as well as pioneering practitioners of the New History; 3) Zhongti xiyong, as the fundamental tenet of this university, in actual practice, was utilized as a slogan for justifying the introduc- tion of Western learning; 4) Japan exerted tremendous influence on the history education at this university through sending history instructors and “re-exporting” new historical methods to China; 5) During the pe- riod discussed, there were in total twenty history instructors at this university. Their qualifications were commendable; 6) Regulations concerning history curriculum design, instruction and examination of the university assumed the task of alleviating the political and economic ordeals of China. Nonetheless, as with other reforms in the late Qing era, the government’s reformation efforts in this university could not rescue it from the predicament of “negative repercussions”. Keywords: The Imperial University of Peking; Disciplinization of History Education; Transformation of Traditional Historiography; Zhongti xiyong; The New History Introduction Dedicated chroniclers coupled with a conscious record- keeping tradition had left Chinese historiography unmatched in richness and continuity for over 3000 years. In imperial China, history was regarded with great importance as it examined the administrative experience of former dynasties. It was therefore considered as a reliable source of guidance for governance. For intellectuals, a good command of historical lore made them more competitive in the battlefield of civil examinations for climbing “the ladder of success”1. History was also classified as the second category (only after Confucian Classics) in the tradi- tional bibliography, signifying its value. However, traditional historiography in China was only considered as a kind of learning, rather than a profession or a discipline.2 History edu- cation in the formal disciplinary sense remained absent. The disciplinization of history education was not incepted until the reformation of civil examinations and the promotion of the modern school system in the late Qing Reform. The transfor- mation of Chinese historiography concurrently started through the criticism of traditional historiography and absorption of new historical methods. The Imperial University of Peking (Jingshi Daxuetang), known as the supreme higher education institution and the highest educational administration in the late Qing China,3 provides an ideal case for studying the various aspects of educational reform in the late Qing era. This paper will mainly focus on how history education as a discipline was in- stitutionalized by examining history education in this university. Meanwhile, special attention will be paid to the transformation of traditional historiography and its interaction with history education. 1Ho Ping-ti adopted this expression to highlight the social mobility via civil examinations in imperial China. See Ho Ping-ti, The Ladder of Success in mperial China: Aspects of Social Mobility, 1368-1911 (New York: Wiley, 1964). For the changing role of historical knowledge in policy questions o Ming-Qing civil examinations, see Benjamin Elman, A Cultural Hi tory o Civil Examinations in Late Imperial China (Berkeley: University of Cali- fornia Press, 2000), pp. 485-503. 2See Liu Longxin, ueshu yu zhidu: xueketizhi yu xiandai Zhongguo shixue de jianli (Scholarship and institutions: disciplinary systems and the estab- lishment of Chinese modern historiography), Beijing: Xinxing chubanshe, 2007, p. 2. Li Jianming, Lishixuejia de jiyi he xiuyang (The art and training of a historian), Shanghai: (SDX Joint Publishing Company), 2007, p. 2. 3The dual instructional-administrative function of the university was con- firmed early in its initial establishment in 1898. As the regulations stipu- lated, “now a university was set up at the capital, so all schools in provinces should be administrated by the university without any obstruction. All regulations and coursework should be put in line with the university so as to ensure a uniform and coordinated implementation”. See Beijingdaxue (Pek- ing University), Zhongguo diyi lishi danganguan (The First Historical Ar- chives of China), eds., Jingshidaxuetang dangan xuanbian (Selected ar- chives of the Imperial University of Peking), Beijing: Beijing University Press, 2001, p. 26. Zhang Jifa gave further explanation on this issue; see Zhuang Jifa, Jingshidaxuetang (The Imperial University of Peking), Taipei: College of liberal arts of National Taiwan University, 1970, p. 142.  L. LI Zhongti xiyong:4 A Fundamental Tenet Subject to Flexibility in Practice The establishment of the Imperial University of Peking rep- resented the new strategy of the late Qing government and in- tellectual elites in dealing with the socio-political strife of the time. The proposal of opening such a university had eventually been put in practice immediately after China’s defeat in the Sino-Japanese War in 1895.5 However preceding this event, in response to repeated fiascos both in the battlefields and at the negotiation table, the following consensuses have gradually been reached inside and outside the court. Firstly, the civil ex- aminations were failing to train and recruit the best men for positions of leadership. Secondly, the impact of the West could be arrested, and China preserved, only if certain aspects of Western knowledge were utilized. Thirdly, a system of school was a source of national strength.6 As a result, there were frequent voices calling for the aboli- tion of civil examinations and promotion of school systems in both official and private discourses. Several new-style schools, such as the Tongwen Guan (School for Studying Foreign Lan- guage, 1862), Guangfangyan Guan (School of Promoting For- eign Language, 1863), Fuzhou Chuanzheng Xuetang (Foochow Naval Academy, 1866) and Ziqiang Xuetang (School of Self- strengthening, 1893) were successively established. The actual effects of these new schools were, however, limited due to the restrictions in scale and available capital resources. Japan, an island the Chinese “superior central empire” regarded with contempt, astounded the empire with its victory. The Petition of Provincial Candidates and the Hundred Days Reform thus fol- lowed. The Imperial University of Peking was initially estab- lished under such circumstances. On May 2, 1896 (GX 22/5/2), Li Duanfen, a vice-ministry of the Board of Punishments, submitted a memorial to the Throne in which he advocated in particular a comprehensive system of schools. The following are his plans for the schools in the provinces and at the capital: [Once established] The provincial schools are to enroll Zhusheng (government students, lowest degree holders) below the age of twenty-five; Juren (winners in the provincial exami- nation) should be allowed to attend if they wish. With regard to courses, studying books on Confucian Classics, history, Chi- nese philosophy and the historiette of the current dynasty, would be supplemented with astronomy, geography, mathemat- ics, science, manufacturing, agronomy, military affairs, mining, current affairs, and diplomacy. The duration of the course is three years. The university at the capital admits traditional de- gree holders aged under thirty. Officials at the capital are also permitted to study there if they so desire. The courses will be similar to those in the provincial schools, but more specialized. Each student majors in one subject which is irrevocable. The course should last for three years. Since courses in the provin- cial schools and university at the capital are numerous, the methods of Hu Yuan in the Song Dynasty can be imitated: to divide the school into sections of Jingyi (Meaning of Classics) and Zhishi (Practice) and to conduct education respectively. Students graduated from these schools would be awarded hon- orable titles similar to those who had passed the civil examina- tions, and they will also be conferred qualifications equivalent to regular officials. By doing so, people will zealously cultivate themselves and gentries will be keen to obtain these honors. Thus ethos will be opened and craftsmanship available, talents will appear beyond the demands.7 Li’s proposal was soon sanctioned by the emperor, which also meant an official announcement for the establishment of the Imperial University of Peking. From the cited proposal above, it is evident that the primary purpose of the university was to re-educate traditional intellectuals and officials with new Western knowledge and technology so that the empire could be strengthened. The government eventually admitted, albeit with reluctance, that traditional intellectuals trained primarily with Confucian Classics and Chinese history could no longer deal with the unprecedented situation then emerging in the political, economic, and diplomatic affairs. The implementation of re- form required more qualified officials and specialists who were conversant in Western learning to enforce such policies. How- ever, Li suggested to grant graduates from this university with honorary traditional titles and official posts, which reflected the dilemma between obtaining traditional degrees and acquiring Western knowledge. Anyhow, the civil examination system had generally been run well for nearly 1300 years. Most importantly, the political and social privileges acquired through this system still attracted the intellectuals magically.8 Even after the official reopening of the university in 1903, over eighty percent of the students still requested for leave to prepare for the cosmopoli- tan examination.9 To balance between tradition and reform, the government adopted an eclectic policy allowing students of the new schools to participate in the civil examinations, as well as to get their coveted traditional degrees after graduation.10 The 7Beijingdaxue (Peking University), Zhongguo diyi lishi danganguan (The First Historical Archives of China), Jingshidaxuetang dangan xuanbian (Selected archives of the Imperial University of Peking), pp. 2-3. Presuma- bly this memorial was initially drafted by Liang Qichao. See Renville Clifton Lund, The Imperial University of Peking, pp. 50-63. 8For the traditional Chinese gentries and their privileges, see Zhang Zhongli, The Chinese Gentry, Studies on Their Role in Nineteenth-Century Chinese Society, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1955. 9Beijingdaxuetang, Beijingdaxuetang tongxuelu (Records of students in the Imperial University of Peking), Beijing: Jinhe yinziguan, 1903, p. 1a. Pro- vided by the Library of Peking University. 10This policy was soon extended to students studying abroad. The student returnees upon graduation had to take a special test. Traditional degrees would then be conferred according to their performance in the test as well as their specialization at overseas schools. This policy has continued even after the formal channel of obtaining such degrees through civil examination was abolished in 1905. As a negative impact, this policy caused a devaluation o traditional degree due to an overabundance of degree holders. It also exac- erbated the dearth of governmental positions as there were too many appli- cants who were theoretically qualified. This had resulted in a large pool o “reserve” civil officials, which was a distinct feature of the late Qing politics For details on this group, see Xiao Zongzhi, Houbu wenguan qunti yu wan- qing zhengzhi (The group of “reserve” civil officials and the late Qing poli- tics), Chengdu: Bashu Press, 2007. 4The idea of Zhongti xiyong, literally interpreted as “Chinese learning for the fundamental essence, Western learning for practical application”, was initially proposed by Feng Guifeng in his Xiaopinlu kangyi (Protests from the cottage of Feng Guifen) in 1861. Zhang Zhidong further elaborated it in his Quanxue pian (Exhortation to Learning) in 1898. Zhang’s book was then presented to the emperor. An edict was soon issued instructing grand councilors, governors and governors-general to study this work and repro- duce copies as many as possible for distribution among scholars and stu- dents of provinces. The widespread promulgation and recognition of Zhang’s work made Zhongti xiyong the principal guidance of the late Qing Reforms. 5As Hao Ping had correctly pointed out, the Imperial University of Peking was actually an outcome of the Sino-Japanese War of 1895 instead of a product of the Hundred Days Reform of 1898. See Hao Ping, Beijingdaxue chuangban shishi kaoyuan (Exploration on the historical facts of the estab- lishment of the Peking University), Beijing: Beijing University Press, 1998, pp. 147-172. 6Renville Clifton Lund, The Imperial University of Peking, Ph.D. disserta- tion, University of Washington, 1957. Ann Arbor, Mich.: University Micro- films International, 1981, pp. 2-3. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 566  L. LI government, on the one hand, attempted to attract students to go to the new schools for studying Western learning. On the other hand, they also planned to combine the educational function of the new schools and the selection function of civil examina- tion,11 although the attempt soon proved to be problematic and futile. Although Li’s proposal did not include detailed information about the course design, a quick glance at it gives the impres- sion of “Zhongti xiyong” (Chinese learning for the fundamental essence, Western learning for practical application), a pre- dominant guidance for the late Qing Reform. Sun Jianai, the chancellor in charge of education, emphasized such a stance in his discourse: Now that the university had been set up at the capital, Chi- nese learning should naturally take predominance while West- ern learning could serve as a supplement. Chinese learning is the essence while Western learning is for application. In case of any inadequacy in Chinese learning, Western learning can be used to complement it. If there is something lost in Chinese learning, Western learning may be applied to reinstate it. Let Chinese learning circumscribe Western learning, which must in no way prevail over Chinese learning. This is the fundamental principle of the establishment of the university.12 As a fundamental principle, the spirit of “Zhongti xiyong” directly influenced later curricula and teaching activities in the Imperial University of Peking. There were various criticisms about this dichotomy of Ti and Yong, and many of them were incisive.13 For reformers in the late Qing period, it was an in- evitable trend to assimilate Western knowledge, but the pro- posal of “complete westernization” seemed to be too radical for them; even for those involved in the later May Forth Movement. Therefore, it appears to be more reasonable to consider “Zhong- ti xiyong” as a strategy adopted by the intellectuals when they encountered Western impacts. Whatever the thought of Zhongti xiyong was interpreted, the fact was that, by means of this nar- rative, traditional Chinese knowledge was emphasized in this university, whilst progressing towards a modern disciplinary sys- tem. The crucial point being, Western learning was introduced into the highest university in this country with government sanction. Moreover, the Imperial University of Peking served as a model for all schools and, its system and regulations were to be propagated to all schools throughout the empire. This was a pivotal step towards national modernization through the adop- tion of Western learning and experience, as well as for the dis- ciplinization of school education in the late imperial period. History Curricula: Vestiges of Tradition versus Impacts of Western Learning From the inception of the university in 1898 to the end of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, there were in total three different regula- tions for this university. This section will mainly analyze the history curricula and their changes according to these regula- tions. In the following sections, particular attention will be devoted to the reality of history education in this university. The first regulations, Daxuetang Zhangcheng (Regulations of the Imperial University), were submitted by Li Hongzhang on July 2, 1898 (GX 24/5/14). The regulations reiterated that the Imperial University is the model for provincial schools and it should govern these schools. The curricula included ten com- pulsory subjects for General Studies, five foreign language courses (each student should choose any one from English, French, Russian, German and Japanese) ,as well as ten major courses for Special Studies (after passing the compulsory courses, each students should concentrate on one or two courses from this pool). The courses for General Studies included the following:14 1) Confucian Classics; 2) Neo-Confucianism; 3) Chinese and Foreign Historiette; 4) Pre-Han Learning; 5) Elementary Mathematics; 6) Elementary Science; 7) Elementary Political Science; 8) Elementary Geography; 9) Literature/Arts; 10) Physical Education. Although a specific subject was not allocated for history in the curriculum, history learning undoubtedly constituted part of the first four courses, especially in the course of Chinese and Foreign Historiette (Zhongwai Zhangguxue). The first version of course design for the Imperial University revealed the domi- nating principle of Zhongti xiyong, thus courses pertaining to Chinese learning were prioritized. This curriculum also demon- strated marked influence of the traditional bibliographic system in which all books were placed in four categories: Confucian Classics, History, Philosophy and Literature. While effects of traditional elements were apparently reflected in the regulations, some new arrangements had also been introduced. Courses concerning foreign historiettes were first included. Another significant modification was that courses concerning literature- categorized as the fourth in the traditional bibliographic system was relegated after those newly introduced but more practical courses, such as Mathematics, Science, Politics and Geography. This can be viewed as the expression of Xiyong (Western learning for practical application) in the curriculum. The second regulations were drafted by Zhang Baixi, the minister in charge of educational affairs, in 1902. The Empress Dowager soon gave her endorsement to the new regulations on August 15, 1902 (GX28/7/12), after the court returned to Bei- jing from a refuge during the Boxers uprising. The regulations for this university, together with the other five regulations for the various schools, were known as Qingding Xuetang Zhang- cheng (Imperially Sanctioned Regulations for Schools) or Renying Xuezhi (Educational Systems of 1902). According to the new regulations, the university should consist of: 1) A Graduate School; 2) Undergraduate Departments; 3) Prepara- tory Programs that included two departments: Politics and- 11See Guan Xiaohong, Shutu nengfou tonggui: liting keju hou de kaoshi yu uancai (Can all roads lead to Rome? Examination and candidate selection after the end of the Imperial Civil Service Examination System), in Zhon g- angyanjiuyuan jindaishi yanjiusuo jikan (Journal of Institution of Modern History of Academia Sinica), Vol. 59 (March 2008), pp. 1-28. 12Beijingdaxue (Peking University), Zhongguo diyi lishi danganguan (The First Historical Archives of China), Eds., Jingshidaxuetang dangan xuan- bian (Selected archives of the Imperial University of Peking), p. 10. 13As Guan Xiaohong stated, both Chinese learning and Western learning has its own essence and application, it is impossible to absorb the applica- tion of Western learning while rejecting its essence, and vice versa. See Guan Xiaohong, Shutu nengfou tonghui: liting Keju hou de kaoshi yu xuan- cai (Can all roads lead to Rome? Examination and candidate selection after the end of the Imperial Civil Service Examination System), pp. 1-28. 14See Beijingdaxue (Peking University), Zhongguo diyi lishi danganguan (The First Historical Archives of China), Eds., Jingshidaxuetang dangan xuan- bian (Selected archives of the Imperial University of Peking), pp. 26-40. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 567  L. LI Technical Studies; 4) Affiliated Schools, including the School for Teachers and the School for Officials. Since a comprehen- sive school system was far from being established in the prov- inces, there was a dearth of qualified students for both the Graduate School and Undergraduate Departments. The Gradu- ate School, as stipulated in the regulations, should primarily focus on research, therefore a curriculum was unnecessary. For the Undergraduate Departments, only a curriculum was out- lined there were no signs that it had been implemented.15 Therefore, only for the Preparatory Programs and the Affiliated Schools were the curricula implemented, the following Table 1 gives the details about history courses in these two divisions. History courses in the Table 1, except for those under the School for Teachers, were predominately related to history of institutions and politics which were always the main themes in traditional historiography. This design not only reflected the in- fluences of traditional historiography on the new education regu- lations, but also revealed the urgent demands for studying his- tory from a more practical perspective. To the late Qing govern- ment, nothing was perhaps more crucial than conducting domes- tic reforms efficiently without causing instability, as well as deal- ing with relationships with foreign powers properly. As its sig- nificant feature and responsibility, study of History was supposed to provide knowledge and experiences for political dealings. However, on June 27, 1903 (GX 29/ intercalary 5/3), the Empress Dowager issued another decree appointing Zhang Zhidong and Rongqing to revise the previous regulations and work out a more comprehensive one.16 The regulations of 1902 were far from sophisticated, and they were actually carried out for only less than one year. The regulations, however, were the first officially promulgated ones in which history curricula and teaching contents for different schools were clearly prescribed. Upon receiving the decree, Zhang Zhidong and his colleagues consulted for the Japanese and Western educational systems in drafting new regulations for schools at various levels. The new regulations, known as Zouding Xuetang Zhangceng (Approved Memorials regarding Regulations for Schools) or Guimao Xu- ezhi (Educational Systems of 1903), received imperial sanction on January 13, 1904 (GX29/11/26), and were shortly imple- mented on a nationwide basis. The higher education, according to the new regulations, was to be divided into two stages: Daxuetang (Undergraduate Divi- sion) and Tongruyuan (Graduate School). The Graduate School should mainly concentrate on research, hence no course should be offered for this stage which normally lasted five years. The Undergraduate Division was to consist of eight schools in which forty-six majors were included, 17among them the major of Chinese history and world history were established under the School of Arts. Course design for the two majors can be sum- marized as Tables 2 and 3. In comparison with history courses in the previous regula- tions, the Educational Systems of 1903 provided a much more comprehensive design. Perhaps the most obvious modification was that courses for majors in Chinese history and world his- tory were designed separately. Other significant improvements in this proposal include: First of all, the designers were aware that courses for majors in Chinese history and world history should not be entirely separated. Therefore a combination of main courses and com- plementary courses was adopted. This required students, espe- cially for those who majored in Chinese history, to study his- tory from a comparative and comprehensive perspective instead of merely focusing on the political history of China as they previously did. More importantly, familiarization with new history theory and paradigm through reading of writings (or translations) on world history was of great importance for the modern transformation of Chinese traditional historiography. Furthermore, historical methodology was taught three hours per week, accounting for one-eighth of the total teaching hours. This arrangement can be considered as a pivotal breakthrough for the transformation and specialization of historiography, because teaching and research should not be isolated from each other, but allowed “mutual interactions” and “cycle interpreta- tions”.18 15There were seven departments suggested in the regulations, namely (De- partment of) Political Science, Arts, Science, Agronomy, Technical Studies, Business and Medicine. The curriculum for the Department of Arts in- cluded Confucian Classics, History, Neo-Confucianism, Literature, Histori- ette, Pre-Han Learning and Foreign language. Again vestiges of the tradi- tional bibliographic system are evident. However, a new course on the foreign language was added. See Beijingdaxue (Peking University), Zhong- guo diyi lishi danganguan (The First Historical Archives of China), eds., ingshidaxuetang dangan xuanbian (Selected archives of the Imperial Uni- versity of Peking), pp. 148-150. 16Beijingdaxue (Peking University), Zhongguo diyi lishi danganguan (The First Historical Archives of China), eds., Jingshidaxuetang dangan xuan- bian (Selected archives of the Imperial University of Peking), . 196. It was evident that this modification was intertwined with the Chinese-Manchu cliquey rivalry. After Zhang Baixi’s designation to take charge of the uni- versity affairs, he enrolled many excellent talents into the university, which caused the government’s misgivings on the expansion of Zhang’s personal influence. Consequently, Rongqing, a Mongol bannerman, was sent to ba- lance the power. Moreover, Zhang Zhidong, the general-governor who was best known for his capability in dealing with educational affairs, came to Beijing for an audience. He was indisputably the most qualified man to take part in amending the regulations. Finally, there were some inadequacies in the regulations of 1902. See He Bingsong, Sanshiwu nian lai Zhongguo zhi daxue jiaoyu (College education in China over the past thirty-five years), in Cai Yuanpei etc. Ed., Wanqing sanshiwu nian lai zhi Zhongguo jiaoyu (Chinese education during the past thirty-five years since the late Qing era). Hong Kong: Longmen shuju, reprinted in 1969, pp. 53-131. For detailed accounts on the political culture in this university, see Timothy B. Weston, The Power of Position: Beijing University, Intellectuals, and Chinese Po- litical Culture, 1898-1929. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), pp. 41-77. Again, it is not difficult to grasp the practical nature of the courses. This is especially evident in the courses for the major in Chinese history, since the majority of courses were con- cerned a study on politics and institutions which was supposed to provide guidance on governance. For the world history major, priorities went to courses pertaining to diplomatic and national history, which was based on similar consideration as the Chi- nese history major. 17Namely the School of Classical Studies (eleven majors), the School o Political and Legal Studies (two majors), the School of Arts (nine major), the School of Medicine (two majors), the School of Science (six majors), the School of Agriculture (four majors), the School of Engineering (nine majors), the School of Business (three majors). See Zhang Zhidong, Zhang Baixi, Rongqing, Zouding xuetang zhangcheng (Approved Memorials re- garding Regulations for Schools), in Zhongguo Jindai jiaoyushi ziliao hui- bian: xuezhi yanbian (Compendium of sources on the history of Chinese modern education: changes of educational systems), Shanghai: Shanghai Education Press, pp. 348-397. 18See Huang Junjie, Lun lishi yanjiu yu lishi jiaoxue zhi guanxi (On the relations of historical research and history education), in Wang Shounan, Zhang Zhelang, eds., Zhonghuaminguo daxue yuanxiao Zhongguo lishi jiao- ue yantaohui lunwenji (Papers presented on the symposium on teaching o Chinese history in the colleges of Republic of China), Taipei: History Asso- ciation of Republic of China, History Department of National Chengchi University, 1992, pp. 141-173. Also Liu Longxin, Xueshu yu zhidu (Schol- arship and institutions), p. 8. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 568  L. LI Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 569 Table 1. History courses prescribed in the educational systems of 1902. School/Depar tment Year Course Title Content of Study Weekly Hours 1st Chinese and World History Comparative history of Chinese and foreign institutions 3 2nd Chinese and World History Political experiences from history of China and the world 3 Department of Politics 3rd Chinese and World History Political experiences from history of China and the world; Business history 3 1st Chinese and World History Comparative history of Chinese and foreign institutions 2 2nd Chinese and World History Political experiences from history of China and the world 2 Preparatory Programs Departments of Technical Studies 3rd Chinese and World History Political experiences from history of China and the world; Engineering Science and Agronomy for students concerned 2 1st History History of Chinese institutions 2 2nd History History of foreign institutions 3 School for Teacher 3rd History Study on the experiences of the rise and fall in Chinese and world history 3 1st Chinese and World History History of Chinese institutions 2 2nd Chinese and World History World history in ancient and Medieval Ages 1 3rd Chinese and World History History of the modern world 2 Affiliated Schools School for Officials 4th Chinese and World History History of the modern world; History teaching method 2 Sources: Peking University, The First Historical Archives of China, eds., Jingshidaxuetang dangan xuanbian (Selected archives of the Imperial University of Peking), pp. 150-161; Notes: Total weekly teaching hours were 36. Table 2. Course design for the major of Chinese history (educational systems of 1903). Teaching Hours (per Week) Type of Course Course Title 1st year 2nd year3rd year Methodology for Historical Research 3 3 3 Imperially Proved Collection of Mirrors for Aid in Government over Several Dynasties 2 2 2 Various Chronicles 5 5 5 Introduction of Chinese Historical Geography 1 0 0 Historical Facts about the Current Dynasty 2 2 1 Diplomatic History of China 0 1 2 Major Courses Studies on the Legal History of China 1 2 3 Summary of Works in the History Section of the Complete Collection of Four Treasuries 1 0 0 World History 1 1 0 Contemporary Geography of China and the World 1 1 0 History of Science in Western Countries 1 1 1 Complementary Courses Foreign Language (to select one from English, French, Russian, German and Japanese) 6 6 6 Total 12 24 24 24 Sources: Zhang Zhidong, Zhang Baixi, Rongqing, Zouding xuetang zhangcheng (Approved Memorials regarding Regulations for Schools), pp. 348-397. Last but not least, there was an apparent emphasis on the learning of foreign language. Both majors, according to the above curricula, were suggested to provide six-hour weekly foreign language training for the students, accounting for one quarter of the total teaching hours. Although no sufficient evi- dence has shown that foreign language teaching was conducted effectively during that time, the proposed curricula could defi- nitely demonstrate the designer’s comprehension on the course structure and the importance of each individual course. Aside from the two history majors mentioned above, relevant  L. LI Table 3. Course design for the major of world history (educational systems of 1903). Teaching h o urs (pe r week) Type of course Course title 1st year 2nd year3rd year Methodology of Historical Research 2 3 4 History of Western Countries 6 6 6 History of Asian Countries 3 2 2 Diplomatic History of Western Countries 2 2 0 Major courses Chronology 1 0 0 Imperially Proved Collection of Mirrors for Aid in Government over Several Dynasties 2 2 2 History of Chinese Legal Systems 0 1 2 World Geography 2 2 2 Complementary courses Foreign Language (to select one from English, French, Russian, German and Japanese) 6 6 6 Total 9 24 24 24 Sources: Zhang Zhidong, Zhang Baixi, Rongqing, Zouding xuetang zhangchen (Approved Memorials Regarding Regulations for Schools), pp. 348-397. history courses were also offered in the affiliated schools19 and other undergraduate departments according to specific demands. The School of Political and Legal Studies provided history courses on legal, financial, political and diplomatic studies. The School of Arts, meanwhile, offered various courses concerning history. For instance, colonial history was taught as part of the geography major, and courses on world history and British history were included in the curricula for the Chinese and Eng- lish literature majors respectively. For the School of Business, courses on business history and industrial history seemed to work well. Even in the major of the Book of Changes under the School of Classical Studies, its main courses contained the history of education, history of science, world history and for- eign language.20 Apart from the School of Arts and the School of Classical Studies, courses for the remaining six schools were over- whelmingly preoccupied with Western learning. After its reor- ganization in 1904, the university “was scheduled to have only one-eighth of its attention devoted to traditional studies.”21 Moreover, a majority of the early students in this university had passed prefectural or provincial civil examinations, with many even achieving the Jinshi status, 22which meant that they gener- ally had a good command of Chinese history and Classics. “Courses of history and Classical studies mainly focused on free discussion, hence the content that students actually studied was Western learning.”23 The philosophy of Zhongti xiyong dominated every aspect in the late Qing Reform and was also adopted as the fundamental tenet of this university. But in real- ity, Western learning was sanctioned to form part of the univer- sity curricula in the name of Xiyong (Western learning for prac- tical application), and courses concerning Western learning ac- tually dominated the whole curricula. Interestingly, the curric- ula were designed by Zhang Zhidong, the man who elaborated the idea of Zhongti xiyong. In this respect, the principle of Zhongti xiyong, the officially approved ideology, was utilized strategically as a slogan for the absorption of Western learning. In other words, the late Qing government and its adherents constantly emphasized on the Zhongti (Chinese learning for the fundamental essence), which exactly revealed the dilemma that Chinese learning suffered when the new school system and academic standard rushed in. The newly established Imperial University provided an important platform both for the institu- tionalization of history education and the transformation of traditional historiography in the early 20th century. History Instructors and Their Qualifications For the late Qing government, one of the major problems in promoting the new school system was the urgent dearth of qualified teachers. When Li Duanfen initially submitted his memorial in 1896, his solutions were: Since it [the school system] is just at the initial stage, students’ learning should begin with simpler [topics] and teachers do not need to choose abstruse materials [to impart]. Now it is appro- priate to command high-ranking officials both at central and local government to recommend gentries who are capable of being teachers, and then submit the list. Either by direct hiring or selection through examination, competent men could be found within such a vast country.24 19Including the School for officials, the School of Medicine, the School o Translation and the School for Teachers. See Zhang Zhidong, Zhang Baixi, Rongqing, Zouding xuetang zhangchen (Approved Memorials Regarding Regulations for Schools), pp. 348-397. 20Zhang Zhidong, Zhang Baixi, Rongqing, Zouding xuetang zhangchen (Approved Memorials Regarding Regulations for Schools), pp. 348-397. 21Renville Clifton Lund, The Imperial University of Peking, p. 215. 22For the reeducation of newly admitted Jinshi, the Jinshiguan (School for Metropolitan Graduates) was set up in 1904 as an affiliated school of the Imperial University. There were still more than 110 Jinshi degree holders in this school when it was closed in 1907. All of them were then sent to Japan for further studies, mainly entering into Hosei University. See Wu Xiang- xiang, Liu Shaotang, ed., Guoli Beijingdaxue jiniankan (Memorial collec- tion of the National Peking University), Taipei: Zhuanji wenxue Press, 1971, Vol. 1, pp. 28-29. 23See Marianne Bastid-Bruguiere, Jingshidaxuetang de kexue jiaoyu (Sci- ence education at the Imperial University of Peking), translated by Gu Liang, in Lishi yanjiu (Historical Research), 1998:5, pp. 47-55. 24Beijingdaxue (Peking University), Zhongguo diyi lishi danganguan (The First Historical Archives of China), eds., Jingshidaxuetang dangan xuan- bian (Selected archives of the Imperial University of Peking), p. 3. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 570  L. LI Sun Jianai, Minister in charge of the university, suggested hunting for qualified instructors in his progress memorial, in which he also pointed out the demand and criteria for foreign teachers: The university should hire several Chinese and foreign in- structors in chief. Chinese teachers must be noble in conduct, erudite in learning and familiar with current affairs. Mastering of foreign language is not however a prerequisite. Foreign teachers should have a good command of Western learning, and they should also learn Chinese language so that there will be no barriers [in teaching].25 In the first regulations drafted by Sun, he reiterated that whether students could succeed depend very much on their teachers, thus a high demand for quality teachers was set out. However, the real problems were that when the university ini- tially opened in 1898, the number of enrolled students was less than expected and foreign teachers were not found. The original quota for Chinese teachers was twenty-four, but only eight were nominated, with just seven eventually taking up the positions. Not surprisingly, all of the seven Chinese teachers were Jinshi degree holders, which meant that they were well educated and trained in traditional Chinese learning.26 It goes without saying that they were all intellectual elites as well as potential political elites in the context of traditional China. Yet it should also be noted that they were generally unfamiliar with the newly intro- duced school system. Moreover, the first phase of this univer- sity only lasted for less than two years due to successive politi- cal unrest. Even though the Imperial University was preserved as the only outcome of the Hundred Days’ Reform, history education in this university was not fully and effectively con- ducted between 1898 and 1902.27 The university was re-opened after the imperial court re- turned to Beijing in 1902. Zhang Baixi was then assigned to take charge of educational affairs so that new regulations for the university were drafted. Henceforth the university gradually went on the right track until a new name (National Peking Uni- versity) and regulations were adopted in 1912. Since this paper mainly focuses on the university during the late Qing era, the following Table 4 only summarizes the general information on history instructors at this university during 1898 and 1911. Among the twenty history teachers listed in Table 4 at the Imperial University of Peking, three were Japanese. Of the other seventeen Chinese teachers, five had all studied abroad and unsurprisingly, they were all educated in Japan. Apart from those mentioned above, eleven teachers held traditional civil examination degrees: seven Jinshi and four Juren. Only one instructor’s (Chen Yan) educational experience was unclear. The inclusion of Japanese scholars and the qualifications as mentioned in Table 4 have significant implications. Firstly, the influence of Japanese at the Imperial University of Peking was obviously considerable. “Essentially all the modern learning was entrusted to Japanese instructors, and the directors of the two main schools of the university were Japa- nese.”28 Hattori Unokichi and Iwaya Magozō, both instructors at the university, were appointed as the dean of the School for Officials and the School for Teachers respectively. In 1909, both of them were awarded a second-rank honorable star by the Throne for their contributions to this university; Hattori Unokichi even earned an honorable Jinshi degree of literature in 1910.29 Meiji Japan exerted its impacts on China not only through Chinese students in Japan, but also via Japanese in- structors and consultants who served in various schools and government departments of the late Qing China.30 Furthermore, the overall qualifications of the history teachers were admirable. There is no doubt on the distinctive qualifica- tions of the three Japanese instructors. They were university graduates and all owned high-ranking degrees. Hattori Unoki- chi and Iwaya Magozō were in fact professors at Tokyo Impe- rial University and Kyoto Imperial University respectively. Hattori Unokichi was a towering sinologist who excelled in Confucianism and Chinese institutions; he also served as a chair professor lecturing Confucianism at Harvard in 1915.31 In addition, he was well versed in world history. As Nakamura Satoru evaluated, “it would be no exaggeration to consider Hattori as one of the earliest founders of world history at the Peking University”.32 Among the Chinese instructors, those who had studied abroad accounted for approximately one-third of the total, with the remaining majority being educated in tra- ditional Chinese learning. Many of the latter were actually pre- eminent scholars in those times, such as Cai Yuanpei, Tu Ji and Chen Fuchen. Teaching at this university, where the well-es- tablished regulations and disciplinary system was still under- way, these history teachers were undoubtedly qualified. As analyzed above, they were Japanese sinologists, student return- ees or famous Chinese scholars. It is not appropriate to use today’s criteria to assess whether these teachers were well qualified as history professors at the university, because to most of them, the standards of qualification, or even the university they worked at, were brand new entities. Having regard to the 28Renville Clifton Lund, The Imperial University of Peking, p. 190. 29Xuebu guanbao (Communiqué of the Board of Education), issue 52, pp. 286-288; issue 96, pp. 27-28. 30With regard to the number of these teachers and consultants, Sanetō Keishū estimated that there were 500 to 600 at its peak during 1905 and 1906. He titled Chinese education during that time as “the era of Japanese teachers”. See Sanetō Keishū, Zhongguoren liuxue Riben shi (A history o Chinese students in Japan), translated by Tan Ruqian and Lin Qiyan, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 1982, pp. 42-49. Kageyama Masahiro pro- vided a precise number of 549. See Kageyama Masahiro, Shinmo niokeru kyoiku kindaika katei to Nihonjin kyosho (Japanese instructors and the educational modernization in the late Qing period), in Abe Hiroshi ed., itchū kyōiku bunka kōryū to masatsu: senzen Nihon no zaika kyōiku jigy (Cultural and educational communications and conflicts between Japan and China: Japanese education undertakings in China before the War), Tōkyō: Daiichi Shobō, 1983, pp. 5-47. For detailed research on this group, see Wang Xiangrong, Riben jiaoxi (Japanese teachers), Beijing: Zhongguo qingnian chubanshe (China Youth Publishing Group), 2000. As Wang pointed out, Japan sent these teachers and consultants to China for exerting its influence on Chinese newly established education system so that they could compete with Western powers in China, and all of these actions were based on its “Continent Policies”. However, as a matter of fact, they also contrib- uted to China’s educational modernization. 31For Hattori Unokichi’s life, see Takada Shinji, ed., Hattori Sensei koki shukuga kinen ronbunshū (Essay collection for the congratulation of Pro- fessor Hattori’s seventieth birthday), Tōkyō: Fuzanbō, 1936. 32Nakamura Satoru, Fubu Yuzhiji yu Zhongguo (Hattori Unokichi and China), Mater thesis of Peking University, 2003, p. 34. 25Beijingdaxue (Peking University), Zhongguo diyi lishi danganguan (The First Historical Archives of China), eds., Jingshidaxuetang dangan xuan- bian (Selected archives of the Imperial University of Peking), p. 11. 26The staff members included four Hanlin Academicians: Zhu Yanxi, Duan Youlan, Tian Geng, Tian Zhimai; two Hanlin Bachelors: Shoufu Zhang Jizhi; and one secretary in the Grand Secretariat. Another Hanlin Bachelor, Hu Jun, failed to take up his post because of illness. Refer to staff roll of the Imperial University of Peking, in the collection of Gongzhong zhupi zouzhe (Imperially Reviewed Memorials), the First Historical Archives of China, archive No.: 04-01-13-0447-001; 04-01-13-0447-010. 27Renville Lund held that the School for Officials was the only one which was actually put into operation before 1902. See Renville Clifton Lund, The mperial University of Peking, p. 94. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 571  L. LI Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 572 Table 4. History instructors at the Imperial University of Peking (1898-1911). Name Employment Period Subjects Taught Educational Qualif ications Hattori Unokichi 1902-1909 Compiled textbooks of world history; taught Ethics, Japanese and Psychology Literanum Doctor (Tokyo) Professor at Tokyo Imperial University Iwaya Magozō 1902-1907 World History, Japanese Legum Doctor (Halle-Wittenburg) Professor at Kyoto Imperial University Sakamoto Kenichi 1904-1908 World History, Japanese, World Geography Bachelor of Arts Cai Yuanpei 1905-1911 Western History, Chinese Jinshi (1892) Chen Fuchen 1906-? History Jinshi (1903) Feng Xunzhan 1905-1908 History Jinshi (1904) Li Jixun 1905-1907 History Jinshi (1898) Wang Gaoji 1906-? History Studied at the Imperial Japanese Army Academy Jiang Shaoquan 1904-1908 World History, Japanese, Ethics, World Geography Short stay for studying in Japan Chen Yan 1906-? Li Ning 1908-1909 History Jinshi (1904) Tan Shaoshang 1909-? History Juren Wang Rongbao 1906-? History Graduated from Nanyang College, then studied at Waseda University and Keio Gijuku (Today’s Keio University) Lin Xiguang ? History Juren Xu Shaoshang 1908 Chinese and World History, Geography Studied at the Sino-Western School in Shaoxing and Qiushi College in Hangzhou, and then studied at the Advanced Normal School of Tokyo, majoring in geography and history. Yang Minzeng ? History Juren Ye Lan ? Chinese and World History, Geography Studied in Japan Tu Ji 1902-? History Jinshi (1892) Wang Zhouyao 1902-? History, Chinese Language Juren Yang Daolin ? History Jinshi (1892) Sources: Wu Xiangxiang, Liu Shaotang, ed. Guoli Beijingdaxue jinian kan (Memorial collection of the National Peking University), Taipei: Zhuanji wenxue chubanshe (Zhuanji wenxue Press), 1971. Vol. 2, pp. 277-307. Chen Chu, ed. Jingshiyixueguan xiaoyoulu (Records of alumni of the Capital School of Translation), Taipei: Wenhai chubanshe (Wenhai Press), 1978, pp. 1-10. Guangxu Jiachen enke huishi tongnian chilu (Records of graduates in the Grace Metropolitan Civil Examination in 1904), provided by National Library of China. Wang Zhouyao, Moxijushi ziding nianpu (A chronological autobiography of Wang Zhouyao), in Beijingtushuguan yingyinshi, ed., Wanqing mingru nianpu (Chronological biographies of famous Confucians in the late Qing Dynasty), Beijing: Beijingtushuguan chubanshe (Beijing Library Press), Vol. 17, pp. 1-136. Ceng Chunxuan’s memorial on the issue of appointing Wang Zhouyao, history teacher at the Imperial University of Peking, as a county magistrate in Guangdong Province. In the collection of Gongzhong zhupi zouzhe (Imperially Reviewed Memorials), the First Historical Archives of China, archive No.: 04-01-38-0191-013. Zhang Hengjia’s memorial on the issue of appointing Tan Shaoshang, a Juren degree holder, to be the teacher at the Imperil University of Peking. In the collection of Junjichu lufu Guangxu Xuantong chao (Ectype of Memorials by the Grand Council during Guangxu and Xuantong’s Reign), archive No.: 03-7214009. Liu Longxin, Maixiang zhuanyehua zhitu: xiandai Zhongguo shijia zige de renzheng yu pinghe (Toward professionalism: the evaluation and qualification of modern Chi- nese historians), in Xinshixue (The New History), Vol. 13:3 (September 2002), pp. 79-115. Yamane Yukio, Kindai Chūgoku no naka no Nihonjin (The Japanese in Modern China), Tōkyō: Kenbun Shuppan, 1994, pp. 5-42. prevailing circumstances at that time, it would not be unrea- sonable to conclude that the overall qualification of these his- tory teachers was commendable. Teachers at this university were capable to provide students with an effective training in both Chinese and Western learning.33 system which arose from the spirit of the time-honored Confu- cian slogan Xue’eryou zeshi (he who excels in study can follow an official career). This had meant that the position of intellec- tual elites and governmental officials often overlapped. In the case of the Imperial University, most teachers in the above Table 4 concurrently held a position in the government. Many students, especially those at the School for Officials, “had one foot in the classroom and one foot in government office,” However, there were certain inadequacies in the education 33For the quality of instruction at this university, see Renville Clifton Lund, The Imperial University of Peking, pp. 240-253.  L. LI which caused them “to worry as much about their bureaucratic ranks and salaries as about their studies.”34 All these factors impaired the effectiveness of instruction, because student ab- sence was serious, and many students flaunted their wealth instead of concentrating on their studies. After his resignation from the presidency of the university, Cai Yuanpei, a history teacher then at the School of Translation, in a 1934 memoir, excoriated the problem as the “ingrained shortcoming inherited from traditional civil examination”.35 History Textbooks and Readings: The Introduction of the New History From the early inception of the Imperial University, the issue of textbooks was in the founders’ mind. An affiliated bureau, specifically in charge of translation and compilation, was ac- cordingly established. In the regulations of 1898, Sun Jianai stressed: Now a translation and compilation bureau should be set up in Shanghai and other places, for the selection and compilation of textbooks on general learning for use by all students. The text- books are to be divided into three levels: for primary schools, secondary schools and the university. Contents of the textbooks should target for students of average calibre, and one lesson is to be fixed for daily study. Talents conversant with both Chi- nese and Western learning should be enrolled to this bureau specifically for compiling and translating work. Textbooks concerning Chinese learning should incorporate the essence of Confucian Classics, pre-Han learning, history and current af- fairs, retaining quintessence but discarding dross. For those books pertaining to Western learning, Western textbooks should be translated but with enhancement.36 With regard to history textbooks, Sun considered that there was no urgent need for new compilations since a large number of existing works were available.37 Sun’s proposal however gave priority to the compilation of textbooks on Western learn- ing. In a way, it also revealed the designer’s comprehension about the content of history teaching, which still stayed within the traditional framework using the existing materials. When the university was re-opened in 1902, facilities and books were needed desperately due to its expansion in scale and vast devastation during the occupation of the Allied Forces. Henceforth additional history textbooks and other reference materials were procured through the following ways. First, translation of publications on world history was mainly conducted by the translation and compilation bureau and its branch office in Shanghai. Two prominent translators, Yan Fu and Lin Shu, were in charge of this bureau and produced many high-quality translations. History of the Second Punic War was jointly translated by Lin Shu and Wei Yi, and other translations completed by the Shanghai branch office during 1903 and 1904 included inter alia A History of Rome, History of Eastern and Western Ethics, History of Western Ethics, A General History of America, World History.38 Moreover, a large number of his- tory books were purchased from Japan and Western countries. In 1898, the first budget for setting up this university was 350,000 taels of which nearly one-third was dedicated for the purchase of books. “Approximately 50,000 taels were allocated for buying Chinese books, 40,000 taels for Western books, and 10,000 taels for Japanese books.”39 According to the inventory of the translation and compilation bureau, more than seventy kinds of history books were imported in 1903, including Ed- ward Gibbon’s masterpiece The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Hattori Unokichi, the aforementioned Japanese teacher, also ordered books from Japan for the univer- sity. In 1905, a purchase transaction of forty-one kinds of his- tory books (sixty-five volumes in total), among other items, was concluded via Maruzen Company Limited.40 A catalogue of textbooks used at the School of Translation was retained, a majority of which concerned world history.41 Finally, lecture notes were usually prepared by teachers prior to publishing, and then distributed to students. In some cases, the notes were first recorded and jointly edited by concerned students, especially if the teacher was Japanese. Lecture notes for history teaching included: Lecture Notes on History by Tu Ji, Lecture Notes on Chinese History by Chen Fuchen, Lecture Notes for General History of China by Wang Zhouyao, and Lecture Notes of World History by Hattori Unokichi.42 In the following para- graphs, the author attempts to explore the changes of history theory and paradigm as revealed in these lecture notes. Firstly the skeleton of Wang Zhouyao’s Lecture Notes for General History of China is summarized as Table 5. With regard to its structure, the notes did not cover the gen- eral history after Tang Dynasty, however Wang Zhouyao’s principles and layout can still be grasped from the listed chap- ters and sections in Table 5. The notes were divided into seven chapters chronologically. In chapter Ⅱ, Ⅴ, and Ⅵ, sub-sections were arranged in terms of traditional classification of schools of Chinese learning. In the realm of traditional Chinese learning, there was a widely recognized structure in which history could only be supplementary to Confucian Classics and Commentar- ies (Yuyi Jingzhuan).43 Wang was concurrently a teacher of 38Zhang Yunjun, Jingshidaxuetang he jindai xifang jiaokeshu de yinjin (The Imperial University of Peking and the introduction of modern Western textbooks), in Beijingdaxue xuebao (Journal of Peking University), vol. 40:3 (2003), pp. 137-145. 39Beijingdaxue (Peking University), Zhongguo diyi lishi danganguan (The First Historical Archives of China), eds., Jingshidaxuetang dangan xuan- bian (Selected archives of the Imperial University of Peking), p. 39. 40Beijingdaxue xiaoshi yanjiushi (Research Office on University History o Peking University) ed., Beijingdaxue shiliao, di yijuan, 1898-1911, pp. 491-496. 41Including History of World Civilization, History of the West by Japanese, apanese History, Western History, History of Education in the East an West, History of Politics, History of Japanese Social Customs, History o apanese Legal System, History of Chinese Civilization, and Twen ty - ou Official Histories. See Beijingdaxue xiaoshi yanjiushi (Research Office on University History of Peking University), ed., Beijingdaxue shiliao, diyijuan 1898-1911 (Historical materials of Peking University, volume one, 1898- 1911), pp. 259-264. 42Zhuang Jifa, Jingshidaxuetang (The Imperial University of Peking), pp. 71-72. 43Luo Zhitian held that the reforms in the early 20th century caused the “translocation of history and Confucian Classics”. Confucian Classics were marginalized while history gradually occupied the “central place” which belonged to the former in traditional scholarship. See Luo Zhitian, Qingmo inchu Jingxue de bianyuanhua yu shixue de zouxiang zhongxin (The mar- ginalization of Confucian Classics and the centralization of history in the early twentieth century), in Hanxue yanjiu (Chinese Studies), 15:2 (1997), . 1-35. 34Timothy B. Weston, The Power of Position: Beijing University, Intellec- tuals, and Chinese Political Culture, 1898-1929, p. 58. 35Cai Yuanpei, Wo zai Beijingdaxue de jingli (My experiences at the Peking University), in Gao Shuping ed, Caiyuanpei quanji (The complete works o Cai Yuanpei), Taipei: Jingxiu Press, 1995, vol. 3, pp. 592-600. 36Beijingdaxue (Peking University), Zhongguo diyi lishi danganguan (The First Historical Archives of China), eds., Jingshidaxuetang dangan xuan- bian (Selected archives of the Imperial University of Peking), p. 3. 37Beijingdaxue xiaoshi yanjiushi (Research Office on University History o Peking University), ed., Beijingdaxue shiliao, diyijuan, 1898-1911 (Histori- cal materials of Peking University, Vol. one, 1898-1911), Beijing: Beijing University Press, pp. 47-48. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 573  L. LI Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 574 Table 5. Skeleton of Lecture Notes for General History of China (by Wang Zhouyao). Chapter Chapter Title Sections I Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors Four: Emperor Fuxi; Emperor Shennong; Emperor Huangdi; Emperor Yao and Shun II Three Dynasties Thirteen: Xia Dynasty; Shang Dynasty; Early Zhou Dynasty; School of Mohism; School of Ming (Sophism); School of Legalism; School of Yinyang, School of Zongheng (Political Strategists) ; School of Physiocratism; School of Military Strategists; School of Medicine; School of Eclecticism; School of Literature III IV Qin and Han Dynasties Three: Qin Dynasty, Western and Eastern Han Dynasties V Schools of Chinese Learning Ten: Emerging Sequence of Confucian Classics; School of The Book of Changes; School of The Book of History; School of The Book of Odes; School of The Book of Rites; School of The Spring and Autumn Annals; School of The Analects of Confucius; School of The Book of Filial Piety; School of Philology; Debates on Huangdi (the Yellow Emperor); Debates on Civilians; Conclusion VI Three Kingdoms, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties Five: Introduction; Confucianism in Three Kingdoms; Confucianism in Jin Dynasty; Confucianism in South- ern and Northern Dynasties; Learning of Taoism; Literature VII Sui, Tang and Five Dynasties Two: Sui Dynasty; Tang Dynasty Sources: Wang Zhouyao, Lecture Notes for General History of China, provided by the National Library of China. The original notes do not contain Chapter III. Confucian Classics in this university, his writings and teaching on Chinese history were thus influenced by the long-adopted structure.44 Nonetheless, he broke the restrictions of traditional historical paradigm, by adopting the chapter-section style in- stead of Jizhuanti (Paradigm of Biographical History) or Bian- nianti (Paradigm of Annalistic History). Moreover, the majority of sections were allocated to delineate the genealogy of Chinese learning. Records on emperors and dynasties occupied a less significant place. More importantly, his interpretation was ap- parently influenced by historical evolutionism. In the introduc- tion of his lecture notes for Confucian Classics, he expressed: One may achieve the essence of learning or only gain the “name” of learning. In the former case, one must comprehend the competitive principle whereby nature favors the fittest for success in the struggle for survival; and must contemplate and explore the reasons why our own country is weak whereas oth- ers are strong so as to know our way forward. Through reading of history, we get to know what proceedings are practicable and what others are impracticable. Through exploration on how human communities have evolved and advanced, we are en- lightened on the principles that sustained a country which can direct as a practical guide in all our proceedings.45 As discussed above, history education and historical research cannot be separated. They in fact interact with each other espe- cially through the platform of a modern university which at- tached equal importance to teaching and research. The history of historiography focused on the recording and interpretation of history, while educational history primarily concerned the meth- odology of how history was taught. But the two issues inter- twined in the Imperial University of Peking and continued to influence each other in the subsequent National Peking Univer- sity.46 To examine history education comprehensively, it is nec- essary to consider institutional innovations (external factors) such as governmental policies in abolishing the civil examina- tions and promoting the modern school system, together with the evolution of historical research and writing (internal factors). Amongst these internal factors, the most influential one was the introduction of the New History. Liang Qichao, the founder of the New History in China, formed his important historical views whilst under refuge in Japan after the failure of the Hundred Days Reform, where were formed. In 1902, Liang published his epoch-making essay, Xinshixue (The New History) in which he advocated to revolu- tionize historical research by a severe censure of the traditional historiography. Apart from adopting the new chapter-section style in history writing, he also advocated the application of evolutionary approach in historical interpretation.47 Liang’s essay was thus considered as the “manifesto that expedited the New History in China.”48 Liang’s views were echoed by his contemporaries. Among them, Liu Shipei, Chen Fuchen and Xia Zengyou were all brilliant historians who had edited new history textbooks (lecture notes) for secondary schools and college students.49 Chen and Liu served as history teachers in 46Liu Longxin’s work provides excellent interpretations on this issue. See Liu Longxin, Xueshu yu zhidu: ueketizhi yu xiandai Zhongguo shixue de ianli (Scholarship and institutions: disciplinary systems and the establish- ment of modern historiography in China). 47Liang Qichao, Xinshixue (The New History), in Yinbingshi wenji (Col- lected writings from the Ice-Drinker’s Studio), Taipei: Xinxing shuju, 1967, vol. 3, pp. 95-101. Coincidentally, the birth of Liang Qichao’s Xinshixue(The ew History) and Zhang Baixi’s Qingding Xuetang Zhanghcheng (Imperi- ally Sanctioned Regulations for Schools) was exactly in the same year (1902). 49Chen Fuchen, Jingshidaxuetang Zhongguoshi jiangyi (Lecture notes on Chinese history at the Imperial University of Peking), in Chen Defu, ed., Chen Fuchen ji (Collected works of Chen Fuchen), Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 1995, Vol. 2, pp. 675-713. Liu Shipei, Zhongguo lishi jiaokeshu(Textbooks for Chinese history), in Liu Shenshu yishu (Posthumous works of Liu Shi- pei), Nanjing: Jiangsu guji chubanshe, 1997, Vol. 2, pp. 2177-2272. Xia Zengyou, Zhongguo gudaishi (History of ancient China), Shanghai: The Commercial Press, 1933. 44His lecture notes on Confucian Classics were divided into eleven chapters Instructions of Confucius, School of The Book of Changes; School of The ook of Histor ; School of The Book of Odes; School of The Book of Rites; School of The Spring and Autumn Annals; School of The Book of Filia iet ; School of The Analects of Confucius; School of Mencius; School o rya (lexicology); School of Philology. The arrangements here are about the same with sections in the chapter five of his ecture notes for genera history of China (refer to Table 5). See Wang Zhouyao, Jingshidaxuetan ingxueke jiangyi (Lecture notes for Confucian Classics at the Imperial University of Peking). Special collection of the Library of Linnan Univer- sity (Hong Kong). 45Wang Zhouyao, Jingshidaxuetang jingxueke jiangyi.  L. LI the Imperial University of Peking and the subsequent National Peking University. Their new historical views permeated his- tory writing and teaching, which meant that the theory of the New History not only influenced the circle of intellectual elites, but also extended its impact to school education; especially to the highest education institution at the capital. Xia’s Zuixin Zhongguo zhongxue lishi jiaokeshu (The Latest Secondary School Textbook for Chinese History, later titled as History of Ancient China) was regarded as “a representative work during the transformation of Chinese modern historiography”.50 Tu Ji, a Jinshi of 1892, took charge of Chinese history teach- ing. His lecture notes comprised two parts covering contents from Pangu, the creator of the universe in Chinese mythology, up till the Spring and Autumn Period. The chapter-section writ- ing style was also adopted. Moreover, he attempted to interpret Chinese history from an evolutionary and comparative perspec- tive by making a comparison between China and ancient Near East. Tu, like many of his contemporaries, was involved in a fierce debate on the origin of Chinese civilization in the early 20th century. Not surprisingly, he endeavored to defend the position that Chinese civilization had arisen as an independent counterpart of Mesopotamian civilization.51 Chen Fuchen, another Chinese history teacher and a newly admitted Jinshi in 1903, emphasized how other subjects related with and complemented history course: History is one discipline of study that embraces in its pursuit some knowledge of all other natural sciences. Without history study, the other pursuits cannot flourish. Conversely, history study cannot stand if emptied of the contents of all other natural sciences. It is therefore not possible to discourse history with one who has no understanding of scientific pursuit, nor can one who lacks the ability to invigorate the field of his own pursuit contribute towards the enrichment of history study... thus one may take a diversifying approach to embrace in his historical pursuit a study of law, pedagogy, psychology, ethics, physics, geography, military affairs, astrology, agriculture, industry and business. Alternatively, one can take an assimilative approach of history study, with a predominant emphasis on political sci- ence and sociology. This is why we cannot discourse history with those who have not a grasp on the method of scientific pursuit. For history is not only itself a scientific discipline but draws in its study knowledge of all other studies.52 It seems that Chen’s standpoints were inclined to “history- centrism”, and it was unrealistic to fulfill his aim to “integrate all subjects into one” because a well-operated disciplinary sys- tem was far from established. Nonetheless, it is still praisewor- thy for he was aware of the interrelations and complementari- ties between history and science-related subjects. In addition, Zhang Heling, the instructor in charge of ethics teaching, whilst adhering to the tenet of “exhaustively investigating ethics and principles, returning to the tradition of the Six Classics”, pro- pounded “verification of the discourse of ancient sages by his- torical facts and wide consultation with the methods of gov- ernance around the world”. He wrote the following in the pro- logue to his notes: How vast the earth is and how diverse the creatures are! Commencing with the epoch of insects, followed by the times of fur and feather, then came the era of human beings. Hun- dreds of millions of years have gone by. In a word, this was a world of one surviving upon another’s extinction. Only in the era of human beings could multiplication and advancement be achieved, but a terminal point can hardly be predicted when looking forward to the future. The refinement of craftsmanship and the perfection of politics are evolved progressively.53 With respect to the teaching of world history, Hattori Unoki- chi explained the following in his lecture notes: The history of the world is just the history of relationships among nations. In all ages, countries which were absolutely isolated and completely unrelated to others were really rare. Affairs pertaining to business, scholarships and politics arose precisely from various relationships among nations.54 During the time of Hattori Unokichi, it was natural that na- tional history and international relationships were the primary themes in world history learning. The relations between ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia were placed at the beginning of his teaching, because he regarded these as the inception of “con- tinuous connection among countries”. He periodized world history into four eras, as listed in Table 6, based on significant historical événement, although he also reiterated that historical transition could not be caused by one single incident. This kind of periodization in history writing was first intro- duced by Japan in the translation of Western works, and then “re-exported” to China via the cultural communication between Meiji Japan and the late Qing China. During the subsequent decades, historical periodization in China was incorporated with various theories such as social Darwinism and Marxism. This paradigm of world history—horizontally, Euro-centered and national history-dominated, vertically, ancient, medieval and modern era—has had a far-reaching effect till today. Furthermore, Hattori Unokichi was aware that the translation of the Gregorian calendar to Chinese dynastic year-numbering would prove beneficial for students. Hattori Unokichi even tried to connect the contents of his lecture notes on psychology with Chinese history, the subject that the students were most familiar with. In explanation of “the connection of concepts”, he wrote severally that “if you descry a flood, you may associ- ate it with the floods in Emperor Yao’s times, think about the quick death of Gun and the feat of King Yu in regulating the Yellow River”, “Zeng Shen dared not enter a lane because it was named Shengmu (Surpass Mother)”, and “presence at the Yi River arouses the reminiscence about Jing Ke”.55 For im- parting the term of “ideal”, Hattori Unokichi cited: 53Zhang Heling, Jingshidaxuetang lunlixue jiangyi (Lecture notes on ethics at the Imperial University of Peking), special collection of the Library o Lingnan University (Hong Kong). 54Hattori Unokichi, Jingshidaxuetang wanguoshi jiangyi (Lectures notes on world history at the Imperial University of Peking), special collection of the Library of Lingnan University (Hong Kong). 55Hattori Unokichi, Jingshidaxuetang xinlixue jiangyi (Lecture notes on psychology at the Imperial University of Peking), 34a-34b. Special collec- tion of the Library of Lingnan University (Hong Kong). Emperor Yao, Gun, King Yu were Chinese pre-historical figures. Gun was executed because he failed to fulfill Emperor Yao’s order to control the floods. Yu, Gun’s son, successfully completed the task and inherited the throne. Zeng Shen was one of disciples of Confucius. Jing Ke was an assassin who failed his mission to assassinate the first emperor of Qin Dynasty in 227 BC. 50Zuo Yuhe, Cong Sibu zhixue dao qike zhixue: xueshu fenke yu jindai Zhongguo zhishi xitong zhi chuangjian (From the learning of Four Catego- ries to the learning of seven subjects: academic specialization and the estab- lishment of knowledge system in modern China), Shanghai: Shanghai shudian Press, 2004, pp. 247-259. 51Zuo Yuhe, Cong Sibu zhixue dao qike zhixue (From the learning of Four Categories to the learning of seven subjects) pp. 256-257. Lin Xiaoying Diana, Peking University, Chinese Scholarship and Intellectuals, 1898-1937. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2005, pp. 37-39. Lin deemed that Tu Ji’s historical evolutionism was influenced by Hattori Unokichi. 52Chen Fuchen, Jingshidaxuetang Zhongguoshi jiangyi (Lecture notes on Chinese history at the Imperial University of Peking), p. 675-677. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 575  L. LI Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 576 Table 6. Periodization of world history by Hattori Unokichi. Periodization Event (from) Event (to) Period Synchronizing with Chinese History Ancient The beginning of world history The fall of Roman Empire Around 2100 BC-476 AD The 4th year of Yuanhui’s reign in the Liu Song Dynasty Medieval The fall of Roman Empire The discovery of America 476-1492 The 5th year of Hongzhi’s reign in the Ming Dynasty Pre-Modern The discovery of America French Revolution 1492-1789 The 54th of Qianlong’s reign in the current dynasty Modern French Revolution Now Sources & notes: Hattori Unokichi, Jingshidaxuetang wanguoshi jiangyi (Lectures notes on world history at the Imperial University of Peking), special collection of the Library of Lingnan University, Hong Kong. However, the existing version in this library only includes the introduction and the first two chapters, namely “Relations among ancient Egypt and Asian countries” and “The golden ages of Hebrew”. According to Zhuang Jifa, the following two chapters should be “Assyrian Empire and the rise of Four Powers” and “Outline of the development of Greece”. See Zhuang Jifa, Jinshidaxuetang (The Imperial University of Peking), pp. 71-72. Mencius wished to restore the Jingtianzhi (Well-field System of land ownership) when he lived in the chaos of warring period. That was the ideal of Mencius. Intellectuals hoped to assimilate the virtues of Emperor Yao and Shun into their contemporary Royalty; likewise contemporary subjects would imbibe the virtues of the then subjects. This was, again, the ideal of these intellectuals.56 cerned contemporary administration, and analogies were also made between China and foreign countries. The following are some examples: Question: He who studied the Zhou Book of Rites normally questioned its complicacy in official-appointing and heavy taxation, and deemed that it would be definitely impracticable for the later ages. Until the investigation of Western systems about official-appointing and tax-imposing, it was found that Western systems were exactly in line with the Zhou Book of Rites. Disorders reigned when the systems were adopted in China, but stability resulted in foreign countries where the same systems were implemented. Why? In such a newly introduced school system, history education was on the way to institutionalization. However, history was frequently invoked to make students understand the new learn- ing. History learning, to a certain extent, served as an effective medium between student’s existing knowledge and the newly added courses. Question: The Duke Wen of Wei dedicated to managing fi- nance, instructing agriculture, promoting business, facilitating craftsmanship, revering religion, industry in study, imparting governing experience, and appointing capable men. Can these fully summarize the essence of Western politics? Or they only cover the superficial aspects? Please discuss. Government Policies as Revealed by the Examination Questions on History As for the entry examination, the regulations of 1898 as- signed twelve questions including Chinese and Western history for the examinees of the Preparatory School and the School for Teachers, while potential students of the School for Official were only required to write an essay on history.57 Perhaps the School for Officials mainly enrolled incumbent officials who already had a good command of Chinese history, a more com- prehensive but less burdensome test task was therefore assigned. In the entry examination regulations of 1909 and 1910, five questions were asked.58 Entry examination questions for appli- cants of the School for Teachers were preserved, including twelve questions on Chinese history and Western history re- spectively. The following will present a brief analysis of the kind of questions involved. Question: Han Feizi satirized Confucians and swordsmen by comparing them with each other. Ban Gu criticized Shiji (His- tory of Grand Historian by Sima Qian) and composed Youxiaz- huan (Collected Biographies of Knight Errant) in which he praised sly heroes but devalued recluses. During the initial phase of Japanese reforms, samurais had contributed quite a lot. So does it mean that knight errants should not be eliminated? Try to explore the reasons.59 These questions, as well as those which appeared in the re- formed civil examinations,60 to a large extent, exposed the most urgent concern of the government. In other words, they repre- sented the issues which the ruler expected the students, also potential officials, to discuss and master. Behind the prompts on the examination papers, an acute “sub-concern” was embedded into history study: to provide practical guidance for the ongoing reforms. These questions, on the other hand, outlined the re- formers’ efforts in seeking a suitable path to reformation. They tried to find the connections and make comparisons between tradition and modernity, China and the West, because no ex- With regard to the form of questions and responses, they were greatly different from the eight-legged essays. Candidates taking the tests were mainly supposed to explicate historical facts, and then either provide comments or propose resolutions. The twelve questions on Chinese history covered issues per- taining to tax-levying, domestic administration, resisting ene- mies, military tactics, financial management, and selecting officials. It is also apparent that many of these questions con- 59Beijingdaxue xiaoshi yanjiushi(Research Office on University History o Peking University), ed., Beijingdaxue shiliao, diyijuan (Historical materials of Peking University, volume one, 1898-1911), 1898-1911, p. 266. 60On October 10, 1901 (GX27/8/28), the emperor issued an edict abolishing the eight-legged essay. Consequently, political discourses and essays on cur- rent affairs were required in the subsequent provincial and metropolitan examinations in 1902, 1903 and 1904. For these questions and examinees’ responses, see Gu Tinglong, ed., Qingdai zhuyuan jicheng (Collection o examination essays in the Qing Dynasty), Taipei: Chengwen chubanshe (Chengwen Press), 1992, Vol. 88-91. 56Hattori Unokichi, Jingshidaxuetang xinlixue jiangyi (Lecture notes on psy- chology at the Imperial University of Peking), 38b-39a. 57Beijingdaxue (Peking University), Zhongguo diyi lishi danganguan (The First Historical Archives of China), eds., Jingshidaxuetang dangan xuan- bian (Selected archives of the Imperial University of Peking), pp. 169-173. 58Beijingdaxue xiaoshi yanjiushi (Research Office on University History o Peking University), ed., Beijingdaxue shiliao, diyijuan, 1898-1911 (Histori- cal materials of Peking University, volume one, 1898-1911), pp. 354-358.  L. LI perience was available in dealing with the unprecedented situa- tion. However, superficiality and sometimes eisegesis was un- avoidable in the narrative of questions. The remaining twelve questions on world history covered various foci as follows: 1) the prosperity and decline of civili- zations like Greece, Roman Empire, South Asia, Korea, Mace- donia, German, Poland and the Ottoman Turks; 2) influential figures in world history such as Peter the Great, George Wash- ington, Alexander the Great, Napoleon Bonaparte etc.; 3) his- torical événement like the Franco-Prussian War and the estab- lishment of the United States; 4) communication between China and the world, for instance, the introduction of Islam, the first appearance of Roman Empire in Chinese historical record.61 Again, unsurprisingly, emphasis was placed on issues pertain- ing to politics and military affairs. Tests were also administered on a regular basis during the study, including monthly quizzes, term examinations, and gra- duation examinations.62 According to the regulations of 1903, students were required to submit their coursework and treatise to fulfill graduation requirements in the third academic year.63 It is questionable, however, whether this rule was carried out strictly since it seemed unreasonable to the undergraduates at that time. Moreover, due to the frequent occurrence of anti-Manchu movements, the late Qing government also sought to reinforce recognition of the legitimacy of its government among the in- tellectuals. History, in all ages, is no doubt an instrumental means in pursuing this goal. Hence, besides including courses like Yupi lidai tongjian jilan (Imperially Proved Collection of Mirrors for Aid in Government over Several Dynasties) and Guochao shishi (Historical Facts about the Current Dynasty) in the curriculum, topics concerning positive aspects of the early history and geography of Manchuria were covered in the ex- aminations. History questions of the first term examination at the School of Translation fully demonstrated this inclination. 1) Outline the rise and fall of the Balhae Kingdom. 2) From which ancient tribe was the current dynasty de- scended? Expound by referring to the edict of Gaozong (Em- peror Qianlong). 3) List the tribes of which the Sanwei (Three Guards) be- longed in the Ming Dynasty. 4) Give a brief of Taizu’s (Nurhachi) punitive expedition against Nikan in the Outer Mongolia. 5) What were the relationships between the Ming Empire and the Tribes of Hada and Yehe? 6) What was the sequence for the extinction of the Hulun Four Tribes? 7) What was the number of chancellors in charge of admini- stration and lawsuit in the early days of the current dynasty? Summarize how the lawsuits were dealt with. 8) Where was the Waerka Tribe? 9) Taizu (Nurhachi) launched punitive expedition against the Ming Empire by declaring seven vendettas, what were the seven vendettas? 10) Which of the Ming’s four armies advocated a proactive strategy? By whom was this strategy severely refuted? And who marched progressively? Try to list their titles and names respectively.64 In Section six, the author has tried to trace the question de- signer’s inclination and to explore the government’s “sub-con- cerns” behind the history examination questions. It would have been helpful to analyze students’ responses in their answer sheets for their proficiency in history learning. Unfortunately, the author’s effort to procure such materials was in vain.65 It is conceivable that the list of these questions (not the answer sheets) had been preserved mainly because the former were required to be included in the official reports for circulation in various government departments, or sometimes be published on newspapers. Conclusion The Imperial University of Peking was first set up as a reac- tion to diffuse the tension of a weak dynasty which arose from the lack of Western learning. The government, together with its intellectual elites, sought to strengthen the weakened empire on the premise of the preservation of Chinese learning and values on which the dynasty previously relied on. This explains why the fundamental tenet of Zhongti xiyong was repeatedly stressed in the planning and operation of this university, as well as in each item on the reformation agenda. But in actual practice, Zhongti xiyong only functioned as an officially-approved slo- gan to justify the introduction of Western learning. Zhang Zhi- dong’s ideology, in this regard, served at least three purposes: as a legitimate narrative for the government, a mental placebo for the adherents of old tradition, and most importantly a flexi- ble strategy for the reformists. Paradoxically for the Manchu- rian government, although reforms seemed unavoidable, as- pects of modern nationalism, racialism and constitutionalism could not be excluded from the absorption of Western learning and technology. A predicament of “negative repercussions” thus perplexed and eventually led to the downfall of the Manchurian administration. The “negative repercussions” was that the more the government invested in the reforms, the better-equipped and nurtured the opponents were to overthrow the current regime.66 As the first trial of a systematical transplantation of Western 61Beijingdaxue xiaoshi yanjiushi, ed., Beijingdaxue shiliao, diyijuan, 1898- 1911, pp. 266-267. 62The principal issues in these examinations were similar to those in the entrance examinations. Questions of term examination at the School fo Teachers in 1909 are hereby cited. Questions on Chinese history: From where the Zhou Dynasty originated? Why did the dynasty succeed so quickly during its conquest? The dynasty largely enfeoffed princes from the royal and other families and fief was conferred accordingly, what was the urpose? Why did this dynasty gradually decline after its removal of capital to the east (Luoyi)? How can we act in line with the circumstances so as to preserve the country and achieve prosperity? Questions on world history: How many great civilizations were there? Where were they located? Which country in Western Europe set the Papal Meridian? The Ancient Egypt was civilized so early but why did she become the weakest in the Medieval Era? See Beijingdaxue xiaoshi yanjiushi, ed., Beijingdaxue shiliao, diyijuan, 1898-1911, pp. 269-271. 63Zhang Zhidong, Zhang Baixi, Rongqing, Zouding xuetang zhangcheng, pp. 348-397. 64See Zhongguo diyi lishi danganguan, ed., Qingshi tudian (Collection of pictures on history of the Qing Dynasty). No.: 01-012-0284. 65Apart from the published sources referred to in this paper, the author has also reviewed the materials in the First Historical Archives of China, the Archives, Library and University History Museum of Peking University, as well as the National Library of China. No such answer sheets were found. Mr. Ma Guojun, the curator of the Archives and University History Mu- seum of Peking University, informed the author that materials pertaining to the Imperial University of Peking were all published. 66Of these revolutionaries, soldiers in the New Army and students in Japan layed key roles. Ironically, a majority of the two groups were funded by the government and were supposed to maintain the existing order. For details, see Edmund S.K. Fung, The Military Dimension of the Chinese evolution: the New Army and Its Role in the Revolution of 1911, Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1980. Kojima Yoshio, Ryūnichi ga- kusei no Shingai Kakumei (The Revolution of 1911 by Chinese students in Japan), Tōkyō: Aoki Shoten, 1989. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 577  L. LI educational system, the Imperial University of Peking set the foundation of university system and disciplinary education in China.67 Despite the organizational and institutional immaturity, the university did provide an important platform both for for- mal history education and for the introduction of new historical theories and methods in the early 20th century. History instruc- tors and students of this university had participated in the con- current process of the disciplinization of history education and the transformation of traditional historiography. They can be regarded as initial participants in the new school system, as well as pioneering practitioners of the New History. REFERENCES Bastid, M. (1998). Jingshidaxuetang de kexue jiaoyu (Science educa- tion at the Imperial University of Peking). Lishi yanjiu (Historical Research), 5, 47-55. Beijingdaxue (Peking University), Zhongguo diyi lishi danganguan (The First Historical Archives of China) (Eds.) (2001). Jingshidaxuetang dangan xuanbian (Selected archives of the Imperial University of Peking). Beijing: Beijingdaxue chubanshe (Peking University Press). Beijing Daxuetang (Imperial University of Peking) (1903). Beijing- daxuetang tongxuelu (Records of students in the Imperial University of Peking). Beijing: Jinhe yinziguan. Beijingdaxue xiaoshi yanjiushi (Research Office on University History of Peking University) (Ed.) (1993). Beijingdaxue shiliao, diyijuan, 1898-1911 (Historical materials of Peking University, vol. one, 1898- 1911). Beijing: Beijingdaxue chubanshe. Cai Y. P. (1995). Wo zai Beijingdaxue de jingli (My experience at the Peking University). In S. P. Gao (Ed.), Caiyuanpei quanji (The com- plete works of Cai Yuanpei) (Vol. 3, pp. 592-600). Taipei: Jingxiu Press. Chen, C. (Ed.) (1978). Jingshiyixueguan xiaoyoulu (Records of alumni of the Capital School of Translation). Taipei: Wenhai Press. Chen F. C. (1995). Jingshidaxuetang Zhongguoshi jiangyi (Lecture notes on Chinese history at the Imperial University of Peking). In D. F. Chen (Ed.), Chen Fuchen ji (Collected works of Chen Fuchen) (Vol. 2, pp. 675-713). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. Elman, B. A. (2000). A cultural history of civil examinations in late imperial China. Berkeley: University of California Press. Fung, E. S. K. (1980). The military dimension of the Chinese Revolu- tion: The new army and its role in the revolution of 1911. Canberra: Australian National University Press. Gongzhong zhupi zouzhe (Imperially Reviewed Memorials), in the First Historical Archives of China. No.: 04-01-13-0447-001; 04-01-13- 0447-010; 04-01-38-0191-013. Gu, T. L. (Ed.) (1992). Qingdai zhuyuan jicheng (Collection of exami- nation essays in the Qing Dynasty). Taipei: Chengwen Press. Guan, X. H. (2008). Shutu nengfou tonggui: Liting Keju hou de kaoshi yu xuancai (Can all roads lead to Rome? Examination and candidate selection after the end of the Imperial Civil Service Examination System). Zhongyangyanjiuyuan jindaishi yanjiusuo jikan (Bulletin of Institution of Modern History of Academia Sinica), 59, 1-28. Guangxu Jiachen enke huishi tongnian chilu (Records of graduates in the Grace Metropolitan Civil Examination in 1904). Provided by the National Library of China. Hao, P. (1998). Beijingdaxue chuangban shishi kaoyuan (Exploration on the historical facts of the establishment of the Peking University). Beijing: Beijing University Press. He B. S. (1969). Sanshiwu nian lai Zhongguo zhi daxue jiaoyu (College education in China over the past thirty-five years). In Y. P. Cai et al. (Ed.), Wanqing sanshiwu nian lai zhi Zhongguo jiaoyu (Chinese education during the past thirty-five years since the late Qing era) (pp. 53-131). Hong Kong: Longmen Book Company. Ho, P.-T. (1964). The ladder of success in imperial China: Aspects of social mobility, 1368-1911. New York: Wiley. Huang, J. J. (1992). Lun lishi yanjiu yu lishi jiaoxue zhi guanxi (On the relations of historical research and history education). In S. N. Wang, & Z. L. Zhang (Eds.), Zhonghuaminguo daxue yuanxiao Zhongguo lishi jiaoxue yantaohui lunwenji (The symposium on Teaching of Chinese History in the Colleges of Republic of China) (pp. 141-173). Taipei: Zhongguo lixhi xuehui, Guoli zhengzhi daxue lishixi (History Association of Republic of China), Guoli zhengzhi daxue lishixi (History Department of National Cheng-chi University). Huang, X. J. (1997). Zhongguo jindai shixue de shuangchong weiji: Shilun Xinshixue de dansheng jiqi suo mianlin de kunjing (The dual crises of modern Chinese historiography: Remarks on the birth of the “New History” and its predicament). Zhongguo wenhua yanjiusuo xuebao (Journal of Chinese Studies), 6, 263-285. Junjichu lufu Guangxu Xuantong chao (Ectype of memorials by the Grand Council during Guangxu and Xuantong’s Reign), in the First Historical Archives of China. No.: 03-7214009. Kageyama, M. (1983). Shinmo niokeru kyoiku kindaika katei to Nihon- jin kyosho (Japanese instructors and the educational modernization in the late Qing period). In A. Hiroshi (Ed.), Nitchū kyōiku bunka kōryū to masatsu: senzen Nihon no zaika kyōiku jigyō (Cultural and educational communications and conflicts between Japan and China: Japanese education undertakings in China before the War) (pp. 5- 47). Tōkyō: Daiichi Shobō. Kojima, Y. (1989). Ryūnichi gakusei no Shingai Kakumei (The Revolu- tion of 1911 by Chinese students in Japan). Tōkyō: Aoki Shoten. Li, J. M. (2007). Lishixuejia de jiyi he xiuyang (The art and training of historians). Shanghai: Sanlian shudian. Liang, Q. C. (1967). Xinshixue (The New History). In Yinbingshi wenji (Collected writings from the Ice-Drinker’s Studio) (vol. 3, pp. 95- 101). Taipei: Xinxing Book Company. Lin, X. Y. D. (2005). Peking University: Chinese Scholarship and In- tellectuals, 1898-1937. Albany: State University of New York Press. Liu, L. X. (2002). Maixiang zhuanyehua zhitu: Xiandai Zhongguo shi- jia zige de renzheng yu pinghe (Toward professionalism: The evalua- tion and qualification of modern Chinese historians). Xinshixue (The New History), 13, 79-115. Liu, L. X. (2007). Xueshu yu zhidu: Xueketizhi yu xiandai Zhongguo shixue de jianli (Scholarship and institutions: disciplinary systems and the establishment of modern historiography in China). Beijing: Xinxing Press. Liu, S. P. (1997). Zhongguo lishi jiaokeshu (Textbooks for Chinese his- tory). In Liu Shenshu yishu (Posthumous works of Liu Shipei) (vol. 2, pp. 2177-2272). Nanjing: Jiangsu guji chubanshe. Lund, R. C. (1957). The Imperial University of Peking. Ph.D. Thesis, Washington, DC: University of Washington. Luo, Z. T. (1997). Qingmo Minchu Jingxue de bianyuanhua yu shixue de zouxiang zhongxin (The marginalization of Confucian Classics and the centralization of history in the early twentieth century). Hanxue yanjiu (Chinese Studies), 15, 1-35. Marianne, B.-B. (1998). Jingshidaxuetang de kexue jiaoyu (Science education at the Imperial University of Peking). Lishi yanjiu (His- torical Research), 5, 47-55. Nakamura, S. (2003). Fubu Yuzhiji yu Zhongguo (Hattori Unokichi and China). Mater’s Thesis, Beijing: Peking University. Sanetō, K. (1982). Zhongguoren liuxue Riben shi (A history of Chinese students in Japan). Hong Kong: Chinese University Press. Takada, S. (Ed.) (1936). Hattori Sensei koki shukuga kinen ronbunshū (Collection of essays for the congratulation of Professor Hattori’s seventieth birthday). Tōkyō: Fuzanbō. Unokichi, H. Jingshidaxuetang wanguoshi jiangyi (Lectures notes on world history at the Imperial University of Peking). Special collec- tion of the Library of Lingnan University (Hong Kong). Unokichi, H. Jingshidaxuetang xinlixue jiangyi (Lecture notes on psy- chology at the Imperial University of Peking). Special collection of the Library of Lingnan University (Hong Kong). 67It should be pointed out that an independent department of history was not established until 1919, three years after Cai Yuanpei took up the presidency of this university. For the development of history education in this univer- sity after 1911, see Wu Xiangxiang, Liu Shaotang, ed., Guoli Beijingdaxue iniankan, vol. 3. Liu Longxin, Xueshu yu zhidu, pp. 97-110. Wang, X. R. (2000). Riben jiaoxi (Japanese teachers). Beijing: China Youth Publishing Group. Wang, Z. Y. Jingshidaxuetang jingxueke jiangyi (Lecture Notes for Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 578  L. LI Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 579 Confucian Classics at the Imperial University of Peking). Special collection of the Library of Linnan University (Hong Kong). Wang, Z. Y. Jingshidaxuetang Zhongguo tongshi jiangyi (Lecture notes for general history of China), provided by the National Library of China. Wang, Z. Y. (2006). Moxijushi ziding nianpu (A chorological autobi- ography of Wang Zhouyao). In Photocopying office of Beijing Li- brary (Ed.), Wanqing mingru nianpu (Chorological biographies of famous Confucians in the late Qing Dynasty) (Vol. 17, pp. 1-136). Beijing: National Library of China Publishing House. Weston, T. B. (2004). The power of position: Beijing University, Intel- lectuals, and Chinese Political Culture, 1898-1929. Berkeley: Uni- versity of California Press. Wu, X. X., & Liu, S. T. (Eds.) (1971). Guoli Beijingdaxue jiniankan (Memorial collection of the National Peking University). Taipei: Zhuanji wenxue chubanshe. Xia, Z. Y. (1933). Zhongguo gudaishi (History of ancient China). Shang- hai: The Commercial Press. Xuebu guanbao (Communiqué of the Board of Education), issue 52; issue 96. Xiao, Z. Z. (2007). Houbu wenguan qunti yu wanqing zhengzhi (The group of “reserve” civil officials and the late Qing politics). Cheng- du: Bashu shushe. Yamane, Y. (1994). Kindai Chūgoku no naka no Nihonjin (The Japa- nese in Modern China). Tōkyō: Kenbun Shuppan, 5-42. Zhang, H. L. Jingshidaxuetang lunlixue jiangyi (Lecture Notes of Eth- ics at the Imperial University of Peking). Special collection of the Library of Lingnan University (Hong Kong). Zhang, Y. J. (2003). Jingshidaxuetang he jindai xifang jiaokeshu de yinjin (The Imperial University of Peking and the introduction of modern Western textbooks). Beijingdaxue xuebao (Journal of Peking University), 40, 137-145. Zhang, Z. D., Zhang, B. X., & Rong, Q. (2007). Zouding xuetang zhang- cheng (Approved Memorials regarding Regulations for Schools). In Zhongguo Jindai jiaoyushi ziliao huibian: Xuezhi yanbian (Compen- dium of sources on the history of Chinese modern education: Changes of educational systems) (pp. 348-397). Shanghai: Shanghai Jiaoyu Chubanshe (Shanghai Education Press). Zhang, Z. L. (1955). The Chinese gentry, studies on their role in Nine- teenth-century Chinese society. Seattle: University of Washington Press. Zhongguo diyi lishi danganguan (The First Historical Archives of China) (Ed.) Qingshi tudian (Collection of pictures on history of the Qing Dynasty). No.: 01-012-0284. Zhuang, J. F. (1970). Jingshidaxuetang (The Imperial University of Peking). Taipei: College of liberal arts of National Taiwan University. Zuo, Y. H. (2004). Cong Sibu zhixue dao qike zhixue: xueshu fenke yu jindai Zhongguo zhishi xitong zhi chuangjian (From the learning of Four Categories to the learning of seven subjects: Academic spe- cialization and the establishment of knowledge system in modern China). Shanghai: SDX Joint Publishing Company.  L. LI Glossary biannianti 編年體 Cai Yuanpei 蔡元培 Chen Fuchen 陳黼宸 Chen Yan 陳訚 Daxuetang zhangcheng 大學堂章程 Feng Xunzhan 馮巽占 Fuzhou chuanzheng xuetang 福州船政學堂 Guangfangyan guan 廣方言館 Guochao shishi 國朝事實 Hada 哈達 Han Feizi 韓非子 Jizhuanti 紀傳體 Jiang Shaoquan 江紹銓 jinshi 進士 Jingshi daxuetang 京師大學堂 Jingyi 經義 junren 舉人 Li Duanfen 李端棻 Li Jixun 李稷勳 Li Hongzhang 李鴻章 Li Ning 李凝 Liang Qichao 梁啟超 Lin Xiguang 林錫光 Liu Shipei 劉師培 Qingding xuetang zhanghcheng 欽定學堂章程 Sanwei 三衛 Sima Qian 司馬遷 Sun Jianai 孫家鼐 Tan Shaoshang 譚紹裳 Tongruyuan 通儒院 Tongwen guan 同文館 Tu Ji 屠寄 Wa’erka 瓦爾喀 Wang Gaoji 汪鎬基 Wang Rongbao 汪榮寶 Wang Zhouyao 王舟遙 Xia Zengyou 夏曾佑 xinshixue 新史學 Xu Shaoshang 許紹裳 xue’eryou zeshi 學而優則仕 Yang Minzeng 楊道霖 Yang Daolin 楊敏曾 Yehe 葉赫 Ye Lan 葉瀾 Yupi lidai tongjian jilan 御批歷代通鑒輯覽 Yuyi jingzhuan 羽翼經傳 Zeng Shen 曾參 Zhang Baixi 張百熙 Zhang Zhidong 張之洞 Zhishi 治事 zhongti xiyong 中體西用 Ziqiang xuetang 自強學堂 Zouding xuetang zhanghcheng 奏定學堂章程 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 580