Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

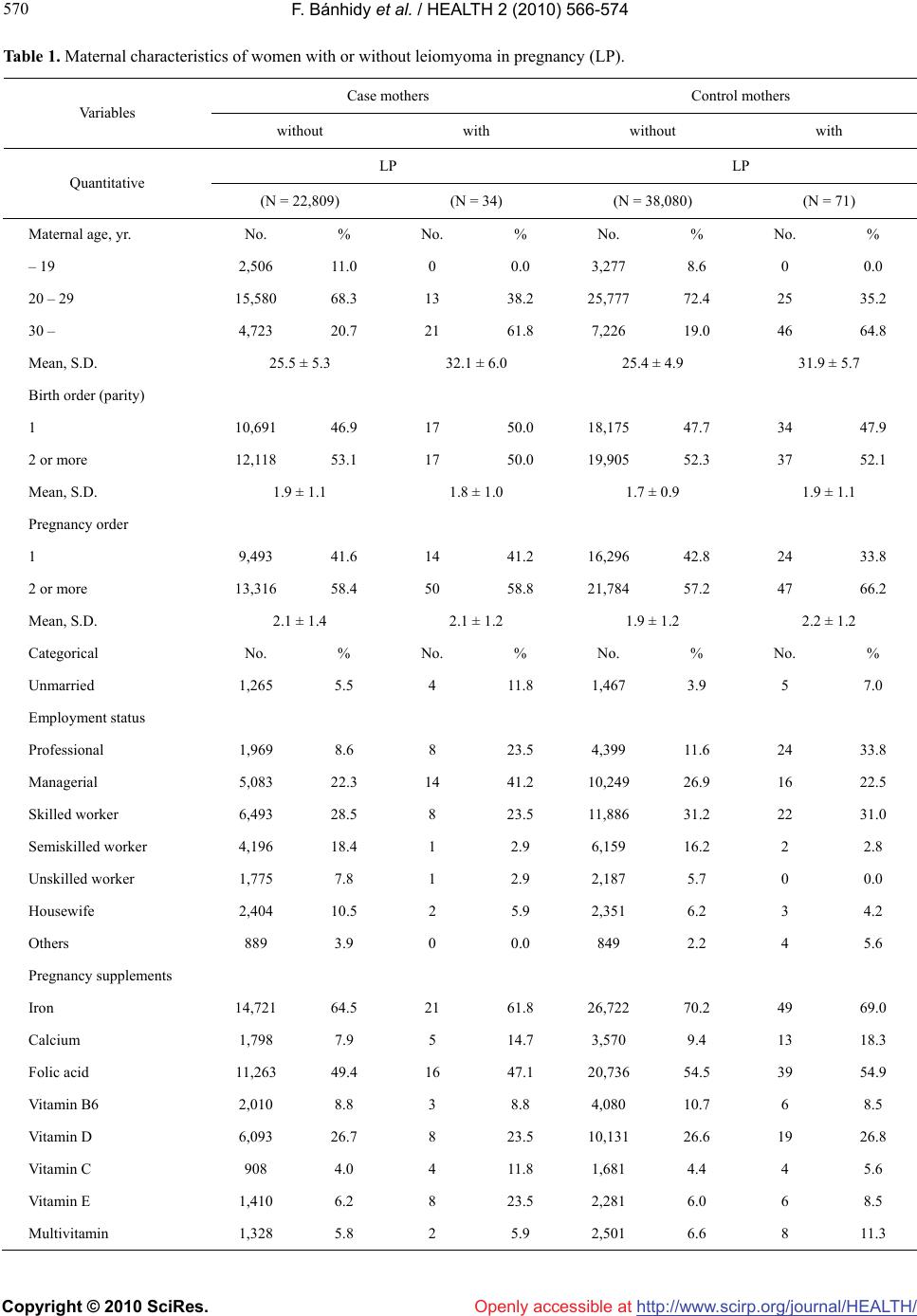

Vol.2, No.6, 566-574 (2010) Health doi:10.4236/health.2010.26084 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Birth outcomes and pregnancy complications of women with uterine leiomyoma—a population-based case-control study Ferenc Bánhidy1, Nándor Ács1, Erzsébet H. Puhó2, Andrew E. Czeizel2* 1Second Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Semmelweis University, School of Medicine, Budapest, Hungary 2Foundation for the Community Control of Hereditary Diseases, Budapest, Hungary;*Corresponding Author: czeizel@interware.hu Received 16 December 2009; revised 6 January 2010; accepted 7 January 2010. ABSTRACT Objective Uterine leiomyoma is not a rare path- ological condition in pregnant women; thus the aim of the study was to evaluate the recent progress in the treatment of these pregnant women on the basis of the association of leio- myoma in pregnancy (LP) with pregnancy com- plications and birth outcomes including struc- tural birth defects, i.e. congenital abnormalities (CA) in the offspring. Design Cases with CA and matched controls without CA in the popula- tion-based Hungarian Case-Control Surveillan- ce System of Congenital Abnormalities (HCC SCA) were evaluated. Only women with pro- spectively and medically recorded LP in prena- tal maternity logbook and medically recorded birth outcomes (gestational age, birth weight, CA) were included to the study. Setting the HCCSCA, 1980-1996 contained 22,843 cases with CA and 38,151 matched controls without CA. Population Hungarian pregnant women and their informative offspring: live births, stillbirths and prenatally diagnosed malformed fetuses. Methods Comparison of birth outcomes of ca- ses with matched controls and pregnancy com- plications of pregnant women with or without LP. Main outcome measures Pregnancy complica- tions, mean gestational age at delivery and birth weight, rate of preterm birth, low birthweight, CA. Results A total of 34 (0.15%) cases had mothers with LP compared to 71 (0.19%) con- trols. There was a higher incidence of threat- ened abortion, placental disorders, mainly ab- ruption placentae and anaemia in mothers with LP. There was no significantly higher rate of preterm birth in the newborns of women with LP but their mean birth weight was higher and it associated with a higher rate of large birth- weight newborns. A higher risk of total CA was not found in cases born to mothers with LP (adjusted OR with 95% CI = 0.7, 0.5-1.1), the spe- cified groups of CAs were also assessed versus controls, but a higher occurrence of women with LP was not revealed in any CA group. Con- clusions Women with LP have a higher risk of threatened abortion, placental disorders and anaemia, but a higher rate of adverse birth outcomes including CAs was not found in their offspring. Keywords: Uterine Leiomyoma in Pregnant Women; Pregnancy Complications; Preterm Birth; Large Birth Weight; Congenital Abnormalities; Population-Based Case-Control Study 1. INTRODUCTION Uterine leiomyoma (fibroid) is benign, smooth muscle tumour and most common non cancerous neoplasm in women of child-bearing age. Though the onset of uterine leiomyoma is increasing with advanced maternal age, this pathological condition occurs in pregnant women as well and because leiomyoma tends to grow under the influence of estrogens, 15-30% of leiomyoma may enlarge during the first trimester of pregnancy [1]. Com- pressive effect of leiomyoma may distort the intrauterine cavity and alter the endometrium thus after conception may interfere implantation, placental development and the growth of the conceptus mechanically [2]. In addi- tion there is an increased uterine irritability and contrac- tility secondary to rapid fibroid growth. Thus the direct mechanical effect and indirect alteration in oxytocinase activity may disrupt the normal progression of uterus and development of the fetus, therefore uterine leio-  F. Bánhidy et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 566-574 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 567 567 myoma is a cause of pregnancy loss, fetal malpresenta- tion, intrauterine growth retardation and premature la- bour [3]. However, most studies of pregnancy complications and birth outcomes in uterine leiomyoma patients were composed of participants from only one hospital or clinic [4-7] and the results of population-based studies have been published only recently [8-9]. The objective of our study was the evaluation the possible association between maternal uterine leiomyoma in pregnancy (LP) and pregnancy complications, in addition adverse birth outcomes, particularly structural birth defects, i.e. con- genital abnormalities (CAs) in the population-based data set of the Hungarian Case-Control Surveillance of Con- genital Abnormalities (HCCSCA) [10]. 2. MATERIALS The protocol of the HCCSCA included five steps. The first step was the selection of cases from the data set of the Hungarian Congenital Abnormality Registry (HCAR), 1980-1996 [11] for the HCCSCA. Notification of CAs is compulsory for physicians from the birth until the end of first postnatal year to the HCAR. Most cases with CA are reported by obstetricians and paediatricians. In Hun- gary practically all deliveries take place in inpatient ob- stetric clinics and the birth attendants are obstetricians. Paediatricians are working in the neonatal units of inpa- tient obstetric clinics, or in various inpatient and outpa- tient paediatric clinics. Autopsy was mandatory for all infant deaths and common in stillborn fetuses during the study period. Pathologists sent a copy of the autopsy report to the HCAR if defects were identified in still- births and infant deaths. Since 1984 fetal defects diag- nosed in prenatal diagnostic centres with or without ter- mination of pregnancy have also been included into the HCAR. Isolated minor anomalies (e.g., umbilical hernia, small haemangioma, hydrocele) were recorded but not evaluated in the HCAR. The total (birth + fetal) preva- lence of cases with CA diagnosed from the second tri- mester of pregnancy through the age of one year was 35 per 1000 informative offspring (liveborn infants, still- born fetuses and electively terminated malformed fetuses) in the HCAR, 1980-1996, and about 90% of major CAs were recorded in the HCAR during the 17 years of the study period [12]. There were three exclusion criteria at the selection of cases with CAs from the HCAR for the data set of the HCCSCA. 1) Cases reported after three months of birth or pregnancy termination were excluded. The longer time between birth or pregnancy termination and data collection decreases the accuracy of information about pregnancy history. This group of excluding cases in- volved 33% of cases and most had mild CAs. 2) Three mild CAs (such as congenital dislocation of hip based on Ortolani click, congenital inguinal hernia, and large haemangioma), and 3) CA-syndromes caused by major mutant genes or chromosomal aberrations with precon- ceptional (i.e. non teratogenic) origin were also ex- cluded. The second step was to ascertain appropriate controls from the National Birth Registry of the Central Statisti- cal Office for the HCCSCA. Controls were defined as newborn infants without CA. In most years two controls were matched to every case according to sex, birth week, and district of parents’ residence. 3. DATA COLLECTION AND EVALUATION The third step was to obtain the necessary maternal, particularly exposure data from three sources: 3.1. Prospective Medically Recorded Data Mothers were asked in an explanatory letter to send us the prenatal maternity logbook and other medical re- cords particularly discharge summaries concerning their diseases during the study pregnancy and their child's CA. Prenatal care was mandatory for pregnant women in Hungary (if somebody did not visit prenatal care clinic, she did not receive a maternity grant and leave), thus nearly 100% of pregnant women visited prenatal care clinics, on average 7 times in their pregnancies. The first visit was between the 6th and 12th gestational week. The task of obstetricians was to record all pregnancy com- plications, maternal diseases and related drug prescrip- tions in the prenatal maternity logbook. 3.2. Retrospective Self-Reported Maternal Information A structured questionnaire along with a list of medicinal products (drugs and pregnancy supplements) and dis- eases, plus a printed informed consent form were also mailed to the mothers immediately after the selection of cases and controls. The questionnaire requested informa- tion on pregnancy complications and maternal diseases, on medicinal products taken during pregnancy according to gestational months, and on family history of CAs. To standardize the answers, mothers were asked to read the enclosed lists of medicinal products and diseases as a memory aid before they filled in the questionnaire. We also asked mothers to give a signature for informed con- sent form which permitted us to record the name and address of cases both in the HCCSCA and in the HCAR. The mean ± S.D. time elapsed between the birth or pregnancy termination and the return of the “information  F. Bánhidy et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 566-574 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 568 package” (questionnaire, logbook, discharge summary, and informed consent form) in our prepaid envelope was 3.5 ± 1.2 and 5.2 ± 2.9 months in the case and control groups, respectively 3.3. Supplementary Data Collection Regional nurses were asked to visit all non-respondent case mothers at home and to help mothers to fill-in the same questionnaire used in the HCCSCA, to evaluate the available medical records, to obtain data regarding life- style (smoking, drinking, illicit drug use) through per- sonal interview of mothers and her close relatives living together and to ask mothers to sign informed consent. Regional nurses visited only 200 non-respondent control and 600 other control mothers as part of two validation studies [13,14] using the same methods as in non-re- spondent case mothers because the committee on ethics considered this follow-up to be disturbing to the parents of all healthy children. Overall, the necessary information was available on 96.3% of cases (84.4% from reply to the mailing, 11.9% from the nurse visit) and 83.0% of the controls (81.3% from reply, 1.7% from visit). Informed consent form was signed by 98% of mothers, names and addresses were deleted in the rest 2%. The procedure of data collection in the HCCSCA was changed in 1997 such that regional nurses visited and questioned all cases and controls, however, these data have not been validated until now, thus only the data set of 17 years between 1980 and 1996 is evaluated here. The fourth step at the evaluation of cases and controls in the HCCSCA is the definition of exposure and to de- termine its diagnostic criteria. The diagnosis of LP was based on the personal manual and ultrasound examina- tion of pregnant women by obstetrician. In general the size of uterine leiomyoma and their types (intramural, subserosal, submucosal, pedunculated, etc) was given in the prenatal maternity logbook but unfortunately these data were not copied out. Pregnant women with dys- functional uterine bleeding, endometrial polyp, endome- triosis, etc were excluded from the study. Gestational time was calculated from the first day of the last menstrual period. Beyond birth weight (g) and gestational age at delivery (wk), the rate of low birth- weight (< 2500 g) and large birth weight (4000 or more g) newborns, in addition the rate of preterm births (< 37 weeks) and postterm birth (42 or more weeks) were analyzed on the basis of discharge summaries of inpa- tient obstetric clinics. The critical period of most major CAs is in the second and/or third gestational month. Drug treatments and folic acid/multivitamin supple- ments were also evaluated. The latter may indicate the level of pregnancy care, and indirectly may show the socio-economic status and the motivation of mothers to prepare and/or to achieve a healthy baby. In addition it is necessary to consider folic acid and folic acid-containing multivitamins in the evaluation of preventable CAs [15-18]. Other potential confounding factors included maternal age, birth order, marital and employment stat- us which had a good correlation with the level of educa- tion and income, thus was regarded at the indicator of socioeconomic status [19], and high fever related dis- eases such as influenza. We used SAS version 8.02 (SAS Institute Ins., Cary, North Carolina, USA) for statistical analyses as the fifth step of the HCCSCA. The occurrence of LP was com- pared in the two study groups and the crude odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calcu- lated. Contingency tables were prepared for the main study variables. The prevalence of other maternal dis- eases, drug intakes and pregnancy supplements used during pregnancy were compared between the group of case and control mothers with LP. We compared the prevalence of LP during the study pregnancy in specific CA groups including at least 2 cases with the frequency of LP in their all matched control pairs. Crude and ad- justed OR with 95% CI were evaluated in conditional logistic regression models. We examined confounding variables by comparing the OR for LP in the models with and without inclusion of the potential confounding variables. Finally, maternal age (< 20 yr, 20-29 yr, and 30 yr or more), birth order (first delivery or one or more previous deliveries), employment status, influenza- common cold (yes/no), and use of folic acid supplement (yes/no) were included in the models as potential con- founders. 4. RESULTS As it appeared at the preliminary evaluation of LP, two groups could be differentiated: 1) prospectively and medically recorded LP in the prenatal maternity logbook, and 2) LP based on retrospective maternal information in the questionnaire. However, the diagnosis of leiomyoma can be frequently questioned without medical record in the latter group and in general it was not possible to dif- ferentiate the leiomyoma with myomectomy before the study pregnancy. Thus, only the first group, i.e. medi- cally recorded LP was evaluated. The case group consisted of 22,843 malformed new- borns or fetuses (“informative offspring”), of whom 39 (0.15%) had mothers with medically recorded leio- myoma during the study pregnancy. However, of these 39 pregnant women, 5 (12.8%) had previous myomec- tomy due to leiomyoma. The total number of births in Hungary was 2,146,574 during the study period between  F. Bánhidy et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 566-574 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 569 569 1980 and 1996. Thus the 38,151 controls represented 1.8% of all Hungarian births, and among those controls, 82 were born to mothers with medically recorded leio- myoma. Of these 82 control mothers, 11 (13.4%) had previous myomectomy. Our objective was to evaluate the possible association of leiomyoma during the study pregnancy with pregnancy complications and adverse birth outcomes, therefore 34 case mothers (0.15%) and 71 control mothers (0.19%) with leiomyoma, i.e. LP were evaluated. Surgical intervention due to LP during the study pregnancy was not recorded in the prenatal maternity logbook and in the discharge summaries of these 105 pregnant women with LP. The number of pregnant women with previous myomectomy of leio- myoma was too small, thus these pregnant women were excluded from this analysis. Of 34 case mothers, 30 (88.2%), while of 71 control mothers, 60 (84.5%) had diagnosed LP in the first visit of prenatal maternity clinic, thus the onset of this patho- logical condition was before conception. The so-called new-onset LP occurred in 4 case mothers and 11 control mothers diagnosed after the fourth gestational month. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of mothers with and without LP as reference. This comparison indi- cates a much higher mean maternal age (due to the larger proportion of women with the age group of 30 and more years) in women with LP. However, the mean birth order was only higher in control mothers with LP, but some- what lower in case mothers with LP than case mothers without LP. Mean pregnancy order (previous birth + recorded miscarriages) was also evaluated, and the dif- ference between birth and pregnancy order was some- what higher in pregnant women with LP in both case mothers and control mothers and these data may indicate a higher rate of miscarriages in previous pregnancies. The proportion of unmarried pregnant women was larger in the groups of LP, while LP was more frequently re- corded in the prenatal maternity logbooks of profes- sional pregnant women. In the group of case mothers, the proportion of managerial women was also larger. Among pregnancy supplements (Table 1), the use of folic acid and iron was similar between mothers with or without LP, but these supplements were used more fre- quently by control mothers. However, medicinal prod- ucts containing calcium were used more frequently by mothers with LP, and a much higher rate of case mothers were treated with vitamin E. Of 2,640 case mothers visited at home, only 4 had LP and one was smoker during the study pregnancy. Of 2,636 mothers without LP, 576 (21.9%) smoked. Of 800 control mothers visited at home, 152 (19.0%) smoked during the study pregnancy. Acute maternal diseases (e.g. influenza) did not occur more frequently in mothers with LP. Among chronic diseases, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus and epi- lepsy was similar in the study groups, but essential hy- pertension (19.0% vs. 7.0%, OR with 95% CI: 3.1, 1.9-5.1), haemorrhoids (18.1% vs. 3.9%, OR with 95% CI: 5.4, 3.3-8.8) and constipation (7.6% vs. 2.1%, OR with 95% CI: 3.9, 1.9-8.1) were more frequent in 105 women with LP than in 60,889 mothers without LP. The incidences of pregnancy complications are shown in Table 2, because they were different in case and con- trol mothers with LP. Threatened abortion, placental disorders (mainly abruption placentae) and anaemia oc- curred more frequently in case mothers with LP than in case mothers without LP. However, LP did not associate with a higher rate of threatened abortion, placental dis- orders and anaemia in control mothers. Thus LP and fetal defects may have some causal association with the higher risk of certain pregnancy complications, such as placental disorders. Unexpectedly the incidence of threatened preterm delivery was not significantly higher in case and control mothers with LP. There was some difference in the distribution and fre- quency of drugs used by mothers with LP explained by the higher use of antihypertensive (methyldopa, metop- rolol, nifedipine) drugs (12.4% vs. 2.6%) and the usual treatment of threatened abortion with allylestrenol (21.0% vs. 14.5%) and diazepam (25.7% vs. 11.3%) in Hungary. In addition the use of hydroxyprogesterone (5.7% vs. 1.2%) and human chorionic gonadotropin (2.9% vs. 0.3%) was more frequent in 105 pregnant women with LP than in 60,889 pregnant women without LP. Birth outcomes are shown in case and control new- borns (Table 3) but statistical testing was used only in controls because CAs may have a more drastic effect for these variables in cases than LP itself. (There was no difference in the sex ratio of the study groups, and twin did not occur among newborns of mothers with LP.) The mean gestational age at delivery was somewhat (0.1 wk in cases and 0.2 wk in controls) longer, the rate of pre- term birth was higher in controls but lower in cases. There was no difference in the rate of postterm births among study groups. However, these differences were not significant. The mean birth weight was 159 and 95 g larger in cases and controls of mothers with LP and these differences were significant. However, these differences were not reflected in the rate of low birthweight new- borns because there was no difference in their rates be- tween cases and controls born to mother with or without LP. There was a higher proportion of large birthweight newborns of both cases and controls but this difference was significant only in cases (OR with 95% CI: 3.0, 1.9-7.2).  F. Bánhidy et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 566-574 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 570 Table 1. Maternal characteristics of women with or without leiomyoma in pregnancy (LP). Case mothers Control mothers Va ri ab le s without with without with LP LP Quantitative (N = 22,809) (N = 34) (N = 38,080) (N = 71) Maternal age, yr. No. % No. % No. % No. % – 19 2,506 11.0 0 0.0 3,277 8.6 0 0.0 20 – 29 15,580 68.3 13 38.2 25,777 72.4 25 35.2 30 – 4,723 20.7 21 61.8 7,226 19.0 46 64.8 Mean, S.D. 25.5 ± 5.3 32.1 ± 6.0 25.4 ± 4.9 31.9 ± 5.7 Birth order (parity) 1 10,691 46.9 17 50.0 18,175 47.7 34 47.9 2 or more 12,118 53.1 17 50.0 19,905 52.3 37 52.1 Mean, S.D. 1.9 ± 1.1 1.8 ± 1.0 1.7 ± 0.9 1.9 ± 1.1 Pregnancy order 1 9,493 41.6 14 41.2 16,296 42.8 24 33.8 2 or more 13,316 58.4 50 58.8 21,784 57.2 47 66.2 Mean, S.D. 2.1 ± 1.4 2.1 ± 1.2 1.9 ± 1.2 2.2 ± 1.2 Categorical No. % No. % No. % No. % Unmarried 1,265 5.5 4 11.8 1,467 3.9 5 7.0 Employment status Professional 1,969 8.6 8 23.5 4,399 11.6 24 33.8 Managerial 5,083 22.3 14 41.2 10,249 26.9 16 22.5 Skilled worker 6,493 28.5 8 23.5 11,886 31.2 22 31.0 Semiskilled worker 4,196 18.4 1 2.9 6,159 16.2 2 2.8 Unskilled worker 1,775 7.8 1 2.9 2,187 5.7 0 0.0 Housewife 2,404 10.5 2 5.9 2,351 6.2 3 4.2 Others 889 3.9 0 0.0 849 2.2 4 5.6 Pregnancy supplements Iron 14,721 64.5 21 61.8 26,722 70.2 49 69.0 Calcium 1,798 7.9 5 14.7 3,570 9.4 13 18.3 Folic acid 11,263 49.4 16 47.1 20,736 54.5 39 54.9 Vitamin B6 2,010 8.8 3 8.8 4,080 10.7 6 8.5 Vitamin D 6,093 26.7 8 23.5 10,131 26.6 19 26.8 Vitamin C 908 4.0 4 11.8 1,681 4.4 4 5.6 Vitamin E 1,410 6.2 8 23.5 2,281 6.0 6 8.5 Multivitamin 1,328 5.8 2 5.9 2,501 6.6 8 11.3  F. Bánhidy et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 566-574 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 571 571 Table 2. Incidence of pregnancy complications in women with or without leiomyoma in pregnancy (LP). Case mothers Control mothers without with without with LP LP (N = 22,809) (N = 34) (N = 38,080)(N = 71) Pregnancy complications No. % No. % Comparison of cases with or without LP OR with 95% CI No. % No. % Comparison of controls with or without LP OR with 95% CI Comparison be- tween case and control mothers with LP Threatened abortion 3,483 15.3 14 41.23.9 (2.0 – 7.7) 6,49417.116 22.51.4 (0.8 – 2.5) 2.4 (0.9 – 5.8) Nausea-vomiting, severe 1,739 7.6 3 8.81.2 (0.4 – 3.8)3,84910.16 8.50.8 (0.4 – 1.9) 1.0 (0.2 – 4.5) Preeclampsia–eclampsia 6672.9 3 8.83.2 (0.9 – 10.5)1,1563.0 2 2.80.9 (0.2 – 3.8) 3.3 (0.5 – 21.0) Pregnancy related renal diseases 3371.5 1 2.92.0 (0.3 – 14.8)4901.32 2.82.2 (0.5 – 9.1) 1.0 (0.1 – 11.9) Placental disorders* 2941.3 2 5.94.8 (1.1 – 20.1) 5921.61 1.40.9 (0.1 – 6.5) 4.4 (0.4 – 50.0) Polyhydramnios 2110.9 0 0.00.0 1900.5 1 1.42.8 (0.4 – 20.6) – Threatened preterm delivery** 2,601 11.4 5 14.71.3 (0.5 – 3.5)5,43714.310 14.11.0 (0.5 – 1.9) 1.1 (0.3 – 3.3) Anemia 3,233 14.2 9 26.52.2 (1.0 – 4.7) 6,34516.713 18.31.1 (0.6 – 2.0) 1.6 (0.6 – 4.2) Others*** 2881.3 1 2.92.4 (0.3 – 17.4)6741.81 1.40.8 (0.1 – 5.7) 2.1 (0.1 – 35.0) *incl. placenta praevia, premature separation of **incl. cervical incompetence as well ***e.g. trauma, poisoning, blood isoimmunisation Bold numbers show significant associations Table 3. Birth outcomes of cases and controls born to mothers with or without leiomyoma in pregnancy (LP). Case mothers Control mothers without LP with LP without LP with LP Va ri ab le s (N = 22,809) (N = 71) (N = 38,080) (N = 71) Comparison Quantitative Mean S.D. Mean S.D Mean S.D. Mean S.D. t = p = Gestational age, wk** 38.6 3.2 38.7 2.4 39.4 2.0 39.6 2.2 0.9 0.37 Birth weight, g* 2,977 705 3,136 752 3,275 511 3,370 575 2.1 0.03 Categorical No. % No. % No. %. No. % OR with 95% CI Preterm birth* 3,760 16.5 5 14.7 3,487 9.2 9 12.7 1.6 0.8 – 3.2 Postterm birth* 573 2.5 1 2.9 3,854 10.1 8 11.3 1.1 0.6 – 2.4 Low birthweight** 4,622 20.3 7 20.6 2,163 5.7 4 5.6 0.8 0.2 – 2.5 Large birthweight** 1,169 5.1 5 14.7 2,865 7.5 7 9.9 1.4 0.7 – 3.0 *adjusted for maternal age, birth order and maternal socio-economic status **adjusted for maternal age, birth order, maternal socio-economic status and gestational age Bold numbers show significant association At the estimation of possible higher risk for CAs, the occurrence of LP during the entire pregnancy of mothers who had cases with different CAs was compared with the occurrence of LP in the mothers of all matched con- trols (Table 4). (We supposed that 4 case and 11 control mothers with the diagnosis of LP after the fourth gesta- tional month might have some effect for the uterus dur- ing the critical period of most major CAs, i.e. during the second and third gestational month.) There was no higher risk for total CA and any CA group, including  F. Bánhidy et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 566-574 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 572 Table 4. Estimate the association between women with leimyoma in pregnancy (LP) and different CAs in their offspring using all matched controls as reference. Entire pregnancy Crude Adjusted Study groups Grand total No. No. % OR 95% CI OR 95% CI Controls 38,151 71 0.2 reference reference Isolated CAs Neural-tube defects 1,203 2 0.2 0.9 0.2 – 3.6 0.6 0.1 – 3.3 Cleft lip ± palate 1,374 3 0.2 1.2 0.4 – 3.7 0.8 0.2 – 3.4 Cleft palate only 601 2 0.3 1.8 0.4 – 7.3 3.5 0.3 – 39.1 Hypospadias 3,038 9 0.3 1.6 0.8 – 3.2 1.3 0.5 – 3.3 Undescended testis 2,051 3 0.1 0.8 0.2 – 2.5 1.1 0.3 – 4.8 Cardiovascular CAs 4,479 6 0.1 0.7 0.3 – 1.7 0.9 0.3 – 2.4 Clubfoot 2,424 4 0.2 0.9 0.3 – 2.4 0.6 0.2 – 2.1 Limb deficiencies 548 3 0.5 3.0 0.9 – 9.4 1.4 0.3 – 6.0 Other isolated CAs 5,776 2** 0.0 0.2 0.0 – 0.8 0.2 0.0 – 0.8 Multiple CAs 1,349 0 0.0 0.0 0.0 – 0.0 – – Total 22,843 34 0.1 0.8 0.5 – 1.2 0.7 0.5 – 1.1 *ORs adjusted for maternal age and employment status, use of folic acid during pregnancy, and birth order **torticollis, branchial cyst clubfoot (i.e. typical manifestation of postural deforma- tion due to fetal malposition). 5. DISCUSSION We examined the possible association between LP and pregnancy complications, in addition birth outcomes. The previously found higher risk of threatened abortion and placental disorders particularly abruption placentae was found [4-6,8,20], but this risk was significant only in the mothers of cases with CA, but not in the mothers of controls without CA in our study. Birth outcomes showed controversial pattern: the previously reported somewhat higher rate of preterm birth was confirmed (e.g. [9]), but only in controls without CA and this in- crease was not significant. On the other hand, there was a larger mean birth weight of cases and controls born to mothers with LP, but it does not associate with a lower risk of low birthweight. In fact cases had a higher rate of large birthweight. There was no higher risk of total and any CA group. The secondary findings of the study confirmed the well-known fact that LP is more frequent in elder preg- nant women (e.g. [8]). The advance maternal age may explain the higher prevalence of essential hypertension, haemorrhoids and constipation. Previously the higher rate of anaemia (mostly iron deficiency) in women with LP due to abnormal menstruation and haemorrhoids (frequently with bleeding) was not frequently mentioned. However, it is worth mentioning that these associations achieved the significant level only in case mothers thus this study suggests that case mothers with LP (i.e. having a malformed fetus) had a higher risk of pregnancy com- plications. The higher mean maternal age did not associate with a higher mean birth order, and the difference between birth and pregnancy order was somewhat larger in women with LP likely due to the higher rate of previous miscar- riages [21]. The high use of vitamin E (particularly in case moth- ers), human chorionic gonadotropin and hydroxypro- gesterone may indicate some infertility problem in women affected with leiomyoma. The prevalence of LP ranged from 0.1-3.9% in previ- ous epidemiological studies [4,6,20,22,23], while this prevalence was 0.15-0.19% in our study, i.e. near to the lower level of this range. A similar lower prevalence (0.37%) was found in another population-based material [8]. Of course, the prevalence is determined by the age distribution of women and the diagnostic criteria, in ad- dition underreporting might occur if a woman did not have a sonographic examination, or the diagnosis was  F. Bánhidy et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 566-574 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 573 573 not reported in the prenatal maternity logbook. The unexpected finding of the study is the larger mean birth weight, and a somewhat higher rate of large birth- weight newborns of pregnant women with LP. Coronado et al. [8] reported a higher rate of low birthweight new- borns and prolonged labor. Our data were not appropri- ate to evaluate the latter, but newborns had larger birth weight. Women with LP had a better socioeconomic status but this confounder was considered at the calcula- tion of adjusted mean birth weight. Obviously these pregnant women at high risk had also a special prenatal medical management but it did not associate with a higher level of folic acid supplementation. Thus further studies are needed to check the efficacy of recent medi- cal management of women with LP and to explain some unexpected findings in this study. The strengths of the HCCSCA are that is a popula- tion-based and large data set including 105 women with prospectively and medically recorded LP in prenatal maternity logbook, furthermore medically recorded ges- tational age at delivery and birth weight in an ethnically homogeneous Hungarian (Caucasian) population. Addi- tional strengths include the matching of cases to controls without CAs; available data for potential confounders, and finally that the diagnosis of medically reported CAs was checked in the HCAR [11] and later modified, if necessary, on the basis of recent medical examination within the HCCSCA [10]. However, this data set also has limitations. 1) There is underreporting of LP in our data set. 2) The occurrence of previous surgical and other medical management in women with leiomyoma was not checked in validation studies, only the medically recorded data in the prenatal maternity logbook were evaluated 3) The size of LP was not recorded thus there was no chance to estimate the dose-effect relation. 4) The occurrence of previous mis- carriages could be estimated only on the basis of differ- ence of birth and pregnancy order in the data set of the HCCSCA, in addition the higher risk of women with LP was supported by the higher rate of vitamin E and hy- droxyprogesterone treatment. 5) The lifestyle data were known only in the subsamples of pregnant women vis- ited at home because previous validation study indicated the unreliability of maternal information regarding their smoking and drinking habit [24]. In conclusion, a higher occurrence of threatened abor- tion and placental disorders was found in the mothers of cases with CA, but not in the mothers of controls with- out CA. There was larger mean birth weight of babies born to mothers with LP and it associated with a higher rate of large birthweight in cases. A higher risk of CAs was not found among the offspring of pregnant women with LP. Thus the pregnancy of women with uterine leiomyoma does not to be discouraged if they wish to have babies, but they need specific and high medical care. REFERENCES [1] Stewart, E.A. (2001) Uterine fibroids. Lancet, 357(9752), 293-298. [2] Ouyang, D. and Hill, J.A. (2002) Leiomyoma, pregnancy and pregnancy loss. Infertility and Reproductive Medi- cine Clinics of North America, 13, 325. [3] Agdi, M. and Tulandi, T. (2008) Endoscopic management of uterine fibroids. Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynacology, 22(4), 569-760. [4] Katz, V.L., Dotters, D.J. and Droegemueller, W. (1989) Complications of uterine leiomyomas in pregnancy. Ob- stetrics and Gynecology, 73(4), 593-596. [5] Davis, J.L., Ray-Mazumder, S., Hobel, C.J., et al. (1990) Uterine leiomyomas in pregnancy: A prospective study. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 75(1), 41-44. [6] Exacoustos, C. and Rosati, P. (1993) Ultrasound diagno- sis of uterine myomas and complications in pregnancy. Obstet- rics and Gynecology, 82(1), 97-101. [7] Vergani, P., Ghidini, A., Strobelt, N., et al. (1994) Do uterine leiomyomas influence pregnancy outcomes? American Journal of Perinatology, 11(5), 356-358. [8] Coronado, G.D., Marshall, L.M. and Schwartz, S.M. (2000) Complications in pregnancy, labour, and delivery with uterine leiomyomas: a population-base study. Ob- stetrics and Gynecology, 95(5), 767-769. [9] Chen, Y-H., Lin, H-C., Chen, S.-F. and Lin, H.-C. (2009) Increased risk of preterm births among women with uterine leiomyoma: a nationwide population-based study. Human Reproduction, 24(12), 3049-3056. [10] Czeizel, A.E., Rockenbauer, M., Siffel, C. and Varga, E. (2001) Description and mission evaluation of the Hun- garian Case-Control Surveillance of congenital Abnor- malities, 1980-1996. Teratology, 63(5), 176-185. [11] Czeizel, A.E. (1997) The first 25 years of the Hungarian Congenital Abnormality Registry. Teratology, 55(5), 299- 305. [12] Czeizel, A.E., Intődy, Z. and Modell, B. (1993) What proportion of congenital abnormalities can be prevented? British Medical Journal, 306(6880), 499-503. [13] Czeizel, A.E., Petik, D. and Vargha, P. (2003) Validation studies of drug exposures in pregnant women. Pharma- coepidemiology and Drug Safety, 12(5), 409-416. [14] Czeizel, A.E. and Vargha, P. (2004) Periconceptional folic acid/multivitamin supplementation and twin pregn- ancies. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 191(3), 790-794. [15] Czeizel, A.E. and Dudas, I. (1992) Prevention of the first occurrence of neural-tube defects by periconceptional vitamin supplementation. New England Journal of Medi- cine, 327(26), 1832-1835. [16] Czeizel, A.E. (1996) Reduction of urinary tract and car- diovascular defects by periconceptional multivitamin supplementation. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 62(2), 179-183. [17] Czeizel, A.E., Dobo, M. and Vargha, P. (2004) Hungarian  F. Bánhidy et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 566-574 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 574 cohort-controlled trial of periconceptional multivitamin supplementation shows reduction in certain congenital abnormalities. Birth Defects Research, 70(11), Part A, 853-861. [18] Botto, L.D., Olney, R.S. and Erickson, J.D. (2004) Vita- min supplements and the risk for congenital anomalies other than neural-tube defects. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 125C(1), 12-21. [19] Puho, H.E., Métneki, J. and Czeizel, A.E. (2004) Mater- nal employment status and isolated orofacial clefts in Hungary. Cental European Journal of Public Health, 13(3), 144-148. [20] Rice, J.P., Kay, H.H. and Mahony, B.S. (1989) The clini- cal significance of uterine leiomyoma in pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 160 (5 Pt 1), 1212-1216. [21] Probst, A.M. and Hill, J.A. (2000) Anatomic factors as- sociated with recurrent pregnancy loss. Seminars in Re- productive Medicine, 18(4), 341-350. [22] Burton, C.A., Grimes, D.A. and March, C.M. (1989) Surgical management of leiomyomata in pregnancy. Ob- stetrics and Gynecology, 74(5), 707-709. [23] Hasan, F., Arumugam, K. and Sivanesaratman, V. (1991) Uterine leiomyomata in pregnancy. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 34(1), 45-48. [24] Czeizel, A.E., Petik, D. and Puho, E. (2004) Smoking and alcohol drinking during pregnancy. The reliability of retrospective maternal self-reported information. Central European Journal of Public Health, 12(4), 179-183. |